Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

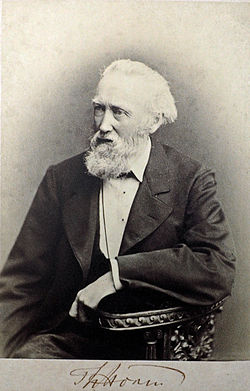

Theodor Storm

View on WikipediaYou can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (February 2025) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Hans Theodor Woldsen Storm (German pronunciation: [ˈteːodoːɐ̯ ˈʃtɔʁm] ⓘ; 14 September 1817 – 4 July 1888), commonly known as Theodor Storm, was a German-Frisian writer and poet. He is considered to be one of the most important figures of German realism.

Key Information

Life

[edit]

Storm was born in the small town of Husum, on the west coast of the Duchy of Schleswig, a fief of the Kingdom of Denmark.[1] His parents were the lawyer Johann Casimir Storm (1790–1874) and Lucie Storm, née Woldsen (1797–1879).

Storm attended school in Husum and Lübeck. He studied law in Kiel and Berlin.[1] While still a law student in Kiel he published a first volume of verse together with the brothers Tycho and Theodor Mommsen (1843).

Storm was involved in the 1848 revolutions. He sympathized with the liberal goals of a united Germany under a constitutional monarchy in which every class could participate in the political process.[2][3] From 1843 until his admission was revoked by Danish authorities in 1852, he worked as a lawyer in his home town of Husum. In 1853 Storm moved to Potsdam, moving on to Heiligenstadt in Thuringia in 1856. He returned to Husum in 1865 after Schleswig had come under Prussian rule and became a district magistrate ("Landvogt"). In 1880 Storm moved to Hademarschen, where he spent the last years of his life writing, and died of cancer at the age of 70.[1]

Storm was married twice, first to Konstanze Esmarch, who died in 1864, and then to Dorothea Jensen.[1]

Work

[edit]Storm was one of the most important authors of 19th-century German Literary realism. He wrote a number of stories, poems and novellas. His two best-known works are the novels Immensee (1849) and Der Schimmelreiter ("The Rider on the White Horse"), first published in April 1888 in the Deutsche Rundschau. Other published works include a volume of his poems (1852), the novella Pole Poppenspäler (1874) and the novella Aquis submersus (1877).

Analysis

[edit]Like Friedrich Hebbel, Theodor Storm was a child of the Wadden Sea plain, but, whilst in Hebbel's verse there is hardly any direct reference to his native landscape, Storm again and again revisits the chaste beauty of its expansive mudflats, menacing sea, and barren pastures — and whilst Hebbel could find a home away from his native heath, Storm clung to it with what may be called a jealous love. In Der Schimmelreiter, the last of his 50 novellas and widely considered Storm's culminating masterpiece, the setting of the rural North German coast is central to evoking its unnerving, superstitious atmosphere, and sets the stage for the battleground of man versus nature: the dykes and the sea.

His favourite poets were Joseph von Eichendorff and Eduard Mörike, and the influence of the former is plainly discernible even in Storm's later verse. During a summer visit to Baden-Baden in 1864, where he had been invited by his friend, the author and painter Ludwig Pietsch, he made the acquaintance of the great Russian writer Ivan Turgenev. They exchanged letters and sent each other copies of their works over a number of years. Hungarian literary critic Georg Lukács, in Soul and Form (1911), appraised Storm as "the last representative of the great German bourgeois literary tradition," poised between Jeremias Gotthelf and Thomas Mann.

Samples

[edit]A poem about his hometown Husum, the grey town by the grey sea (German: Die graue Stadt am grauen Meer).

| Die Stadt | The town |

|---|---|

| Am grauen Strand, am grauen Meer Und seitab liegt die Stadt; Der Nebel drückt die Dächer schwer, Und durch die Stille braust das Meer Eintönig um die Stadt. |

By the grey shore, by the grey sea —And close by lies the town— The fog rests heavy round the roofs And through the silence roars the sea Monotonously round the town. |

| Es rauscht kein Wald, es schlägt im Mai Kein Vogel ohn' Unterlaß; Die Wandergans mit hartem Schrei Nur fliegt in Herbstesnacht vorbei, Am Strande weht das Gras. |

No forest murmurs, no bird sings Unceasingly in May; The wand'ring goose with raucous cry On autumn nights just passes by, On the shoreline waves the grass. |

| Doch hängt mein ganzes Herz an dir, Du graue Stadt am Meer; Der Jugend Zauber für und für Ruht lächelnd doch auf dir, auf dir, Du graue Stadt am Meer. |

Yet all my heart remains with you, O grey town by the sea; Youth's magic ever and a day Rests smiling still on you, on you, O grey town by the sea. |

Analysis and original text of the poem from A Book of German Lyrics, ed. Friedrich Bruns, which is available in Project Gutenberg.[4]

Translated works

[edit]- Theodor Storm: Immensee. Translated by George Putnam Upton. A. C. McClurg & Co. 1907.

- Theodor Storm: The Dykemaster. Translated by Denis Jackson. Angel Books 1996.

- Theodor Storm: Hans and Heinz Kirch with Immensee & Journey to a Hallig. Translated by Denis Jackson & Anja Nauck. Angel Books 1999.

- Theodor Storm: Paul the Puppeteer and Other Short Fiction. Translated by Denis Jackson. Angel Books 2004.

- Theodor Storm: The Rider on the White Horse and selected stories. Translated by James Wright. New York 2009.

- Theodor Storm: Carsten the Trustee & Other Fiction. Translated by Denis Jackson. Angel Books 2009.

- Theodor Storm: "Grieshuus: The Chronicle of a Family". Translated by Denis Jackson. Angel Books 2017.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Adolf Stern, Biographical Note in The Rider on the White Horse, The Harvard Classics Shelf of Fiction, 1917

- ^ Jackson, David A (1992). Theodor Storm: The Life and Works of a Democratic Humanitarian. Berg Publishers. p. 201.

- ^ Ebersold, Günther (1981). Politik und Gesellschaftskritik in den Novellen Theodor Storms. Peter Lang Verlag. p. 13.

- ^ UNC.edu[permanent dead link]

Sources

[edit]- David Dysart: The Role of Paintings in the Work of Theodor Storm. New York / Frankfurt 1993.

- Norma Curtis Wood: Elements of Realism in the Prose Writings of Theodor Storm. Cambridge 2009.

External links

[edit]- Works by Theodor Storm at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Theodor Storm at the Internet Archive

- Works by Theodor Storm at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Theodor Storm and his world

- Biography and many works by Storm

- Der Schimmelreiter (Audiobook in German)

- All poems of Theodor Storm

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 968–969.

Theodor Storm

View on GrokipediaEarly Life and Education

Birth and Family Background

Hans Theodor Woldsen Storm was born on 14 September 1817 in Husum, a North Frisian town in the Duchy of Schleswig under Danish rule at the time.[3][2] The birth took place at Markt 9, a property his father had acquired the previous year.[4] His father, Johann Casimir Storm (1790–1874), practiced as a lawyer (Rechtsanwalt) in Husum.[5][6] His mother, Lucie Storm (1797–1879), born Woldsen, descended from a patrician family local to Husum; her father, Simon Woldsen, was Theodor Storm's maternal grandfather.[4][6] Storm grew up in a well-to-do bourgeois household shaped by legal traditions and the region's coastal, rural character.[2] The family's prosperity stemmed from the father's profession, positioning them within the educated middle class of the area.[7]Academic Training and Early Influences

Storm received his early education at local schools in Husum, his birthplace on the North Frisian coast, where he developed an interest in poetry during his teenage years.[8] He subsequently attended the Gymnasium in Lübeck, completing his secondary studies there before pursuing higher education.[9] In 1838, Storm began studying law at the University of Berlin, continuing there through 1839, before transferring to the University of Kiel to complete his legal training from 1839 to 1842.[10] [11] At Kiel, he passed his state legal examinations and qualified as a lawyer, setting the foundation for his professional career in the judiciary.[1] Storm's early literary influences stemmed from the Romantic tradition, particularly the poets Joseph von Eichendorff and Eduard Mörike, whose lyrical introspection and nature imagery resonated in his initial verse compositions.[12] During his Kiel studies, he forged a significant friendship with the historian Theodor Mommsen and Mommsen's brother Tycho, leading to their joint publication of Liederbuch dreier Freunde (Songbook of Three Friends) in 1843, a collection that marked Storm's entry into print as a poet.[13] [14] This collaboration, alongside the somber coastal environment of Husum—which he later described as the "gray town by the sea"—fostered his emerging themes of regional identity and human melancholy, blending personal observation with poetic form.[15]Professional and Political Career

Legal Practice and Judiciary

After completing his legal studies at the University of Kiel from 1837 to 1842, Theodor Storm established a practice as an advocate in his hometown of Husum, Schleswig-Holstein, where he handled civil and criminal cases in the local courts.[16] His early career aligned with his father's profession as a notary, emphasizing meticulous legal work amid the region's tensions over Danish rule.[1] Storm's professional stability ended in 1852 when Danish authorities dismissed him from his position due to his active support for German-nationalist movements during the Schleswig-Holstein uprisings, including his involvement in patriotic associations that opposed Danish sovereignty.[16] This political purge forced his relocation to Potsdam in 1853, where he subsisted without steady legal employment, relying on literary pursuits and support from acquaintances while awaiting opportunities in Prussian-administered territories.[15] In 1856, Storm secured a judicial appointment as a judge in Heiligenstadt (now part of Göttingen, in Prussian Saxony), marking his entry into the formal judiciary and allowing him to apply his legal expertise in a more structured environment away from Schleswig-Holstein's conflicts.[1] Following Prussia's victory in the Second Schleswig War of 1864, which led to the annexation of Schleswig-Holstein, he returned to Husum in the same year as district magistrate (Amtsrichter), overseeing local judicial administration and combining it with literary endeavors.[1] Over the subsequent decades, Storm advanced to higher judicial and administrative roles in Husum, including oversight of district courts and related governance duties, which he maintained until his retirement in 1880 at age 63, relocating to nearby Hademarschen to focus on writing.[15] These positions underscored his competence in Prussian legal frameworks, though his tenure reflected the era's fusion of judiciary functions with regional political stabilization efforts post-annexation.[17]Involvement in Schleswig-Holstein Politics

Storm supported the liberal aspirations of the Revolutions of 1848, aligning with efforts to incorporate Schleswig-Holstein into a unified Germany governed by a constitutional monarchy.[14] His advocacy for the German cause in the duchies positioned him against Danish sovereignty, particularly amid the First Schleswig War (1848–1851), where provisional German-aligned forces sought autonomy but ultimately failed.[18] Following Denmark's reassertion of control via the 1852 London Protocol, which deepened Schleswig's ties to the Danish crown, Storm's pro-German sentiments rendered his continued legal practice in Husum untenable.[12] In 1853, he relocated to Potsdam in Prussia, effectively entering exile as Danish authorities barred him from work due to his promotion of Schleswig-Holstein's alignment with German interests. During this period, he channeled patriotic views into poetry critiquing foreign rule over his homeland.[12] Storm's return to Husum occurred in 1864, after Prussian and Austrian victory in the Second Schleswig War expelled Danish forces and placed the duchies under Prussian administration via the Convention of Vienna. This resolution vindicated his earlier stance, allowing resumption of judicial roles without political reprisal, though his direct engagement shifted toward literary expressions of regional identity rather than active partisanship.[19]Literary Development

Initial Poetry and Romantic Beginnings

Storm's engagement with poetry commenced during his secondary education in Husum, where he drafted initial verses influenced by the emotional intensity and natural imagery prevalent in German Romanticism. By 1837, while studying law at the University of Kiel, he secured his debut publications in regional periodicals, marking the onset of his literary output amid the era's Romantic fervor.[20] These formative poems drew heavily from the stylistic legacies of Joseph von Eichendorff and Heinrich Heine, incorporating motifs of unrequited love, wanderlust, and the sublime Frisian seascape, which evoked a profound Heimweh—a nostalgic yearning for rooted origins characteristic of Romantic sensibility.[2][21] Friendship with Theodor Mommsen, a schoolmate and budding historian, further bolstered Storm's confidence in lyrical expression, as he credited Mommsen with instilling the vigor underlying his verse.[21] The works' melodic structure and restrained emotional depth distinguished them, blending folklore elements with introspective melancholy, though they retained Romantic individualism over emerging realist precision.[15] Culminating this phase, Storm assembled his early compositions into the 1852 volume Gedichte, a slim anthology of song-like pieces that encapsulated his Romantic inclinations through simple forms and evocative depictions of transient joys amid nature's indifference.[22] Subsequent editions expanded the collection, reflecting persistent appeal, yet these origins foreshadowed his pivot toward prosaic realism in later decades.[23]Shift to Novellas and Realism

Storm's transition to prose began with the publication of his first novella, Immensee, in 1850, which depicted a nostalgic idyll of childhood love and loss, retaining romantic elements of mood and reminiscence while introducing a narrative structure suited to exploring interpersonal dynamics.[12][24] This work, alongside his concurrent poetry collections like Gedichte (1852), marked an initial pivot from lyrical verse toward extended fictional forms, influenced by late Romantic predecessors such as Eduard Mörike.[12] His debut prose collection, Zwei Novellen (1852), further evidenced emerging Realist tendencies through more grounded depictions of everyday settings and human emotions, diverging from pure lyricism.[12] By the mid-1850s, Storm had committed more substantially to novellas, producing works like Ein grünes Blatt (1855) that blended sentimental introspection with subtle environmental realism drawn from his North Frisian homeland.[24] The death of his first wife in 1865 intensified themes of melancholy and isolation, as seen in Tiefe Schatten (1865), prompting a stylistic evolution toward psychological depth and causal motivations in character actions.[12] Over the subsequent decade, he produced more than 50 novellas, increasingly emphasizing empirical observation of social conditions, family strife, and human frailty against natural forces, aligning with the principles of poetic realism that valorized the tangible values of ordinary life without forsaking imaginative lyricism.[15] A decisive shift occurred around 1870, when Storm's narratives transitioned from mood-driven sentimentality to terse, objective portrayals incorporating logical plot progression and historical context, exemplified by Draussen im Heidehof (1871) and later Aquis Submersus (1875).[24] This maturation reflected influences from Realist contemporaries like Gottfried Keller and Ivan Turgenev, resulting in works that critiqued destiny's inexorability through realistic struggles, as culminated in his final novella, Der Schimmelreiter (1888), a stark tragedy of a dike master's confrontation with superstition and elemental peril.[12][15] Poetic realism thus defined Storm's mature style, merging precise depiction of locale and causality with understated poetic sensibility, transcending regional anecdote to address universal human conditions.[12]Major Works and Themes

Key Novellas and Their Plots

Immensee (1851)Immensee follows Reinhard, who as an elderly man reflects on his youth and unrequited love for Elisabeth, his childhood companion in a rural lakeside setting.[25] The narrative frames their bond through shared memories of storytelling, nature walks, and promises exchanged before Reinhard departs for university studies, leaving Elisabeth behind.[26] Upon his return years later, Elisabeth has married another man and borne children, prompting Reinhard to recognize the irretrievable loss of their youthful idyll, symbolized by the inaccessible lake island of Immensee.[25] Aquis Submersus (1876)

Set in northern Germany shortly after the Thirty Years' War, Aquis Submersus centers on Johannes, an orphaned boy who receives patronage from the wealthy Katharina family and develops a forbidden romance with Katharina, the daughter.[27] Social class barriers and Katharina's arranged betrothal to a nobleman lead to Johannes's accidental killing of her fiancé in a duel, forcing him into exile while Katharina bears his child out of wedlock.[27] The title, derived from a Latin inscription meaning "drowned in the waters," foreshadows tragedy as Johannes returns incognito, witnesses Katharina's descent into poverty and death by drowning, and grapples with guilt and societal retribution.[28] Der Schimmelreiter (1888)

The Rider on the White Horse depicts Hauke Haien, a mathematically gifted youth from humble origins in the North Frisian coastal marshes, who rises to become dike master through innovative engineering against traditionalist opposition.[29] Hauke marries the farmer's daughter Tede Haiens and implements advanced dike designs to protect the land from floods, but envy from locals and a catastrophic storm test his ambitions, culminating in his death astride a white horse during the breach.[30] Framed as a tale recounted by an old teacher to a skeptical narrator, the novella blends realism with folkloric elements, portraying Hauke's legacy as both heroic and haunted by superstition.[31]

Recurring Motifs: Nature, Heimat, and Human Frailty

Storm's novellas recurrently interlace motifs of nature, Heimat, and human frailty, forming the core of his Poetic Realism, where empirical landscapes of northern Germany underscore psychological and existential tensions. In works such as Immensee (1851) and Der Schimmelreiter (1888), nature serves not merely as backdrop but as a dynamic element mirroring human endeavors and their inevitable curtailment, while Heimat evokes a profound regional rootedness in Schleswig-Holstein's Frisian marshes and coasts, often tinged with nostalgic loss. Human frailty manifests through characters' moral vulnerabilities, hubristic ambitions, and subjugation to fate, highlighting the limits of individual agency against inexorable forces.[32] Nature appears as a vast, indifferent entity that both nurtures and overwhelms, with detailed depictions of North Sea tempests, floods, and marshes emphasizing its dual role in setting mood and driving plot. In Der Schimmelreiter, the sea relentlessly erodes dikes, drowning livestock and men during storms, its "storm-whipped" waves and treacherous shallows symbolizing uncontrollable peril, yet it rebounds indifferently in "golden sunlight" after catastrophe. Similarly, Immensee employs a January snowstorm precipitating death and a thunderstorm coinciding with the protagonist's moral lapse, contrasting serene waters with violent elemental fury to evoke transience. These elements recur across Storm's oeuvre, transforming "unpoetic" rural terrains into revelations of human insignificance amid environmental vastness.[32][33] The motif of Heimat underscores an intense attachment to homeland, portraying Schleswig-Holstein's coastal communities as sources of identity and continuity, often through symbols like dikes and ancestral furnishings that bind generations. In Der Schimmelreiter, the Frisian dike embodies communal defense and "Sippengefühl" (kinship solidarity), with protagonist Hauke Haien's engineering zeal aimed at preserving this regional bastion against encroaching seas. Domestic objects, such as the "Wandbett" and "Lehnstuhl," anchor characters to their native heath, fostering a nostalgic regionalism that permeates Storm's narratives, reflecting his own Husum upbringing amid Danish-Prussian border tensions. This Heimatgefühl evolves into homesickness in exile-themed stories, privileging empirical fidelity to local customs over abstract nationalism.[32] Human frailty emerges as characters' emotional and ethical shortcomings precipitate downfall, often exacerbated by heredity, isolation, or conflict with superstition and society. Hauke Haien in Der Schimmelreiter exemplifies hubris through his dike reforms, confessing neglect of duty ("Ich habe meines Amtes schlecht gewartet") before succumbing to floodwaters on the "Faulbett," his lineage extinguished in symbolic vulnerability via his daughter Wienke. In Immensee, Friedrich's moral weakness and romantic isolation yield elegiac regret over forfeited love, underscoring guilt and emotional compromise. Storm extends this to paternal legacies and inexorable decline in tales like Carsten Curator, where frailty appears as fated inheritance rather than mere sentiment, grounding psychological depth in causal sequences of personal failing against communal norms.[32]Literary Style and Analysis

Poetic Realism and Empirical Depiction

Storm's adoption of poetic realism marked a stylistic evolution from his earlier romantic influences, integrating empirical observations of bourgeois life with aesthetic idealization to counter modernity's prosaic tendencies.[34] This approach emphasized the portrayal of everyday realities—such as rural routines, familial tensions, and regional customs—in Schleswig-Holstein, rendered through detailed, verifiable depictions that prioritized observable facts over abstract sentiment.[33] Central to this style was Storm's empirical depiction of landscape, which served as both a literal setting and a symbolic extension of human conditions. In works like his later novellas, he described North Frisian elements—marshes, dikes, fog-shrouded coasts, and fluctuating tides—with precision derived from local topography and meteorological patterns, transforming potentially unpoetic terrains into revelations of isolation and vulnerability.[33] These portrayals avoided romantic escapism by grounding causality in natural forces' tangible impacts, such as erosion threatening settlements or seasonal storms mirroring personal decline, thereby achieving a realist fidelity to environmental determinism without descending into deterministic fatalism.[35] Poetic realism in Storm's prose thus balanced factual intensity with lyrical modulation; descriptive passages intensified reality's contours while infusing them with mood-evoking lyricism, as seen in the atmospheric interplay of light, weather, and human figures that heightened thematic depth.[36] This synthesis rejected the era's stark naturalism, instead simulating alternative realities through self-reflexive narrative techniques that retained romantic motifs like the uncanny but subordinated them to empirical coherence.[34] Critics have noted this as a "marriage of poetic spirit with the realistic letter," where subjective experience projected onto objective settings yielded open-ended explorations of existence rather than prescriptive judgments.[35]Criticisms: Sentimentalism vs. Causal Depth

Critics of Theodor Storm's literary style have frequently characterized his poetic realism as veering into sentimentalism, where evocative moods and emotional nostalgia overshadow substantive exploration of causal mechanisms driving character actions and societal outcomes. This perspective posits that Storm's narratives, particularly in his earlier novellas, prioritize atmospheric lyricism—rooted in Romantic and Biedermeier influences—over analytical dissection of motivations, often attributing events to inexorable fate, natural forces, or vague human frailty rather than traceable chains of cause and effect. For example, traditional interpretations argue that works like Immensee (1851) elicit reader sympathy through idyllic recollections and unfulfilled longing, but fail to unpack the socioeconomic or psychological antecedents that might realistically precipitate such personal tragedies, rendering the prose more akin to sentimental escapism than empirical realism.[37][38] This sentimental bent is seen as limiting causal depth, with detractors like those aligned with social realist frameworks—such as Georg Lukács—contending that Storm's focus on individual introspection and regional Heimat motifs evades broader historical or class-based causations central to true realism. Lukács' emphasis on dialectical materialism highlights how Storm's characters often appear passive recipients of destiny, their frailties depicted through poetic suggestion (Andeutung) rather than through rigorous causal linkages to environmental, economic, or interpersonal determinants, which could reveal underlying structural realities. In contrast to contemporaries like Fontane, who integrated sharper social critiques, Storm's approach is critiqued for substituting emotional pathos for such explanatory rigor, potentially diluting the transformative potential of literature by confining it to affective resonance over causal insight.[39][40] Later scholarship, however, challenges this binary by defending Storm's subtlety as a deliberate technique that invites readers to infer causal layers beneath surface sentiment, arguing that overt psychological probing would disrupt his minimalist realism. Nonetheless, the enduring criticism underscores a perceived imbalance: while Storm masterfully renders empirical details of coastal life and human transience, his reluctance to foreground causal agency—favoring instead a deterministic worldview shaped by personal losses and regional insularity—can render narratives emotionally compelling yet analytically shallow, prioritizing Stimmung (mood) over mechanistic depth. This tension reflects Storm's evolution from pre-1870 sentimental emphases to post-unification realism, yet persists as a point of contention in assessing his contributions to German prose.[37][22]Personal Life and Later Years

Family Dynamics and Private Struggles

Storm married his first cousin, Constanze Esmarch, in 1846; the union produced seven children and provided significant inspiration for his literary output, with Constanze embodying ideals of domestic harmony and emotional depth in his portrayals of family life.[15][9] Her death in 1865 left Storm to manage a household amid grief, prompting reflections on mortality that permeated his subsequent works, such as Tiefschatten (Deep Shadows), published the following year.[7] In 1866, Storm remarried Dorothea Jensen, with whom he had one additional child, totaling eight offspring across both marriages; this second union offered stability during his later professional relocations, including his appointment as a judge in Husum.[9] He maintained a devoted paternal role, prioritizing family as the core of domestic existence and actively overseeing his children's education—insisting on daily practice in German and Latin while away on duties, as evidenced in his correspondence expressing anxiety over unsupervised homework.[41] Private struggles intensified through hereditary and health-related burdens within the family; Storm's eldest son, Hans, developed severe alcoholism, mirroring patterns of addiction Storm observed in prior generations, including Constanze's lineage, and contributing to ongoing emotional and practical challenges in household management.[42] These dynamics underscored tensions between paternal expectations and the frailties of offspring, themes Storm navigated without public disclosure but which echoed in his realistic depictions of human vulnerability.[41] Financial pressures from early career instability and regional political upheavals, such as the Schleswig-Holstein conflicts that briefly exiled him in the 1850s, further strained family resources, though Storm's legal practice eventually provided security.[24]Final Works and Death

In 1880, Storm retired from his judicial position and relocated to Hademarschen, a rural estate in Holstein, where he dedicated his remaining years primarily to literary composition.[12] This period marked a culmination of his productivity, with continued focus on novellas that refined his poetic realism, drawing from North Frisian landscapes and human perseverance against natural forces.[15] Storm's final major work, Der Schimmelreiter (The Rider on the White Horse), was serialized in the Deutsche Rundschau in April 1888, shortly before his death, and stands as his last completed novella.[43] The narrative centers on a dyke master battling coastal floods and skepticism, embodying themes of rational engineering clashing with superstition and elemental fury, and is frequently cited as his artistic pinnacle for its structural innovation and atmospheric depth.[12] [15] Storm succumbed to stomach cancer on July 4, 1888, at age 70 in Hademarschen, concluding a career spanning poetry, law, and over four dozen novellas.[12] [21] [44] His death occurred amid ongoing health decline, which had not halted his writing output in the preceding years.[7]Reception, Influence, and Legacy

Contemporary and Post-Unification Response

Storm's literary output during his lifetime elicited measured acclaim within German literary circles, particularly among fellow Realists, though commercial success remained elusive as he prioritized his judicial career over full-time authorship.[45] Early poems published in the 1840s drew notice for their atmospheric depiction of North Frisian landscapes, while the 1852 novella Immensee marked his initial breakthrough, lauded for its subtle portrayal of unfulfilled love and memory through precise, evocative prose.[45] Contemporaries such as Gottfried Keller appreciated the work's emotional restraint and fidelity to everyday experience, positioning Storm as a counterpoint to more sensational Romanticism. Post-unification, following Germany's 1871 consolidation under Prussian dominance, Storm's focus on regional Heimat themes—evident in novellas like Pole Poppenspäler (1874) and Der Schimmelreiter (1888)—drew mixed responses amid rising industrialization and national homogenization.[46] Critics including Theodor Fontane, a close correspondent, valued Storm's psychological insight but critiqued his persistent "Husumerei," or insular fixation on Husum's moors and dikes, as limiting broader appeal and verging on parochialism.[47] [46] Nonetheless, reviewers like Erich Schmidt extolled Storm's mature style in 1880 for its empirical realism and causal exploration of fate, arguing it surpassed mere sentimentality to reveal underlying human vulnerabilities.[48] Der Schimmelreiter, released months before Storm's death on July 4, 1888, garnered praise for integrating folkloric elements with rational inquiry into environmental mastery, reflecting era-specific tensions between tradition and progress.[45] Overall, while Storm's oeuvre commanded respect for its unadorned causality over ideological fervor, its niche regionalism constrained mass resonance in the imperial context.[46]Scholarly Interpretations and Adaptations

Scholars have interpreted Storm's novellas as products of a deliberate narrative craft rather than mere sentimentality, emphasizing the operations of a fictional intelligence tormented by themes of transience and isolation.[49] In works like Der Schimmelreiter (1888), critics highlight the central conflict between human rationality and superstition, with the protagonist Hauke Haien's white horse symbolizing demonic otherness to the community while underscoring his innovative struggle against natural forces like the sea.[50] This novella's frame narrative invites dual readings—rational engineering triumph versus supernatural retribution—reflecting Storm's ambivalence toward empirical progress amid coastal folklore.[51] Early criticism of Immensee (1850) praised its lyrical depiction of lost love and symbolic landscape, but later analyses reveal structural asymmetry in time and memory, where flashbacks expose the protagonist's solipsistic regrets and anti-Romantic critique of idealized youth.[22] Scholars such as Charles H. McCormick examine Storm's technique across novellas like Aquis Submersus and Immensee, arguing that symbolism and episodic structure create ironic distances, challenging readers to discern causal depths beneath surface melancholy.[52] Broader studies, including Clifford A. Bernd's, portray Storm's fiction as haunted by existential fears, with motifs of solipsism and human frailty manifesting in isolated figures confronting nature's indifference.[53] Storm's religious skepticism, evident in lyrics like Über die Heide, has drawn attention for its atheistic undertones, portraying human life as transient amid cosmic void, though some interpret this as veiled piety rather than outright rejection.[54] Maritime tales such as Hans und Heinz Kirch (1881) elicit readings of modernity's tensions, where sailors embody fluid alternatives to bourgeois stasis, negotiating progress against traditional Heimat bonds.[55] Adaptations of Storm's works include multiple film versions of Der Schimmelreiter, such as the 1934 German drama directed by Hans Deppe and Curt Oertel, starring Mathias Wieman, which emphasized regional realism.[56] Later renditions comprise a 1978 feature by Alfred Weidenmann and a 1985 East German TV film, both retaining the novella's themes of dike-building ambition and spectral ambiguity.[57] An opera adaptation by Wilfried Hiller premiered in Kiel in 1998, musicalizing the tale's elemental conflicts. For Immensee, Veit Harlan's 1943 melodrama featured Kristina Söderbaum, focusing on marital regret and childhood romance, while a 1989 TV version by Klaus Gendries streamlined the symbolic idyll for modern audiences.[58] These adaptations often amplify visual motifs of North German landscapes, though critics note variances in capturing Storm's understated irony.[59]Enduring Impact on German Literature

Storm's contributions to Poetic Realism established a template for blending meticulous empirical depiction of regional landscapes and social milieus with subtle psychological introspection, influencing later German writers who sought to elevate provincial narratives beyond mere anecdote. His focus on the North Sea coast and Frisian settings in works like Der Schimmelreiter (1888) introduced a causal interplay between human endeavor, natural forces, and fate, prefiguring modernist explorations of environmental determinism and individual hubris in authors such as Thomas Mann. Mann, in essays and comparative studies, highlighted Storm's role as a bridge in the bourgeois tradition, citing shared motifs of familial decline and cultural erosion evident in Storm's Grieshuus (1884) and Mann's own Buddenbrooks (1901), where both depict inexorable decay through generational lenses grounded in observable social dynamics.[60][61] This legacy persists in scholarly examinations of Storm's narrative craft, which emphasize his advancement of the novella form through layered symbolism and temporal subjectivity, as analyzed in monographs dissecting his evolution from descriptive realism to poetic synthesis. For instance, studies of motifs like the double and memory in tales such as Aquis submersus (1877) reveal how Storm anticipated 20th-century concerns with unreliable narration and subjective time, paving interpretive paths for post-realist fiction without romantic idealization.[53][62] Such analyses underscore his restraint against sentimentality, favoring causal depth in human frailty over emotional excess, a balance that counters earlier critiques and sustains his relevance in discussions of realism's internal tensions.[63] In broader German literary historiography, Storm's adherence to humanitarian liberalism from peripheral vantage points—rooted in empirical observation of community and environment—contrasts with urban-centric realisms, offering a counter-model that endures in regionalist traditions and adaptations. His Märchen and novellas, often overlooked in favor of major realists, have garnered renewed attention for their supernatural undercurrents within rational frameworks, influencing hybrid genres in post-unification literature that grapple with Heimat amid globalization.[64][65] This niche but persistent impact is evident in sustained academic output, including theses on his landscape poetics and liberalism, affirming his foundational role without overstating dominance over contemporaries like Fontane.[33][66]References

- https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q26993

.jpg/250px-Theodor_Storm_(1817-1888).jpg)

.jpg/1280px-Theodor_Storm_(1817-1888).jpg)