Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

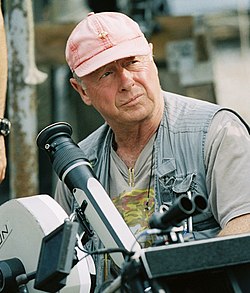

Tony Scott

View on Wikipedia

Anthony David Leighton Scott (21 June 1944 – 19 August 2012) was an English film director and producer.

Key Information

He made his theatrical film debut with The Hunger (1983) and went on to direct highly successful action and thriller films such as Top Gun (1986), Beverly Hills Cop II (1987), Days of Thunder (1990), The Last Boy Scout (1991), True Romance (1993), Crimson Tide (1995), Enemy of the State (1998), Man on Fire (2004), Déjà Vu (2006), The Taking of Pelham 123 (2009) and Unstoppable (2010).

Scott was the younger brother of film director Ridley Scott. They both graduated from the Royal College of Art in London, and were among a generation of British film directors who were successful in Hollywood having started their careers making television commercials.[1] In 1995, both Tony and Ridley received the BAFTA Award for Outstanding British Contribution To Cinema.[2] In 2010, they received the BAFTA Britannia Award for Worldwide Contribution to Filmed Entertainment.[3]

Early life

[edit]Scott was born in Tynemouth, at the time in Northumberland, now in North Tyneside, North East England, the youngest of three sons of Elizabeth (née Williams) and Colonel Francis Percy Scott, who served in the Royal Engineers.[4][5][6][7] Dixon Scott, a grand uncle, was a pioneer of the cinema chain, opening cinemas around Tyneside. One Tyneside Cinema, in Newcastle, is the last remaining newsreel cinema operating in the United Kingdom.[8] Tony was a pupil at Rosebank School in Hartlepool, West Hartlepool College of Art and graduating from Sunderland Art School with a fine arts degree. At the age of 16, he appeared in the short film Boy and Bicycle, Ridley's directorial debut (he was 23).[9]

Tony Scott continued his studies in art in Leeds after failing to gain admission to the Royal College of Art in London (he would succeed in a later attempt). In 1969, he made a short film based on the Ambrose Bierce story "One of the Missing". As Ridley had previously cast him in a film, Tony reciprocated by giving his brother a role in the production. "The film cost £1,000", he recalled in April 2012. While at the Royal College of Art, where he was taught by Raymond Durgnat, he starred in "Don't Walk", a film by fellow students Hank Onrust and Richard Stanley. The film credits state it was "made for BUNAC by MARCA films at the Royal College of Art". Again following in Ridley's footsteps, Tony graduated from the Royal College of Art, although he intended to become a painter.[10] Their eldest brother Frank had earlier joined the British Merchant Navy.[11]

Film career

[edit]Commercials

[edit]The success of his elder brother's fledgling television commercial production outfit, Ridley Scott Associates (RSA), drew Tony's attention to film. Ridley recounted, "Tony had wanted to do documentaries at first. I told him, 'Don't go to the BBC, come to me first.' I knew that he had a fondness for cars, so I told him, 'Come work with me and within a year you'll have a Ferrari.' And he did!"[12] Tony recalled, "I was finishing eight years at art school, and Ridley had opened Ridley Scott Associates and said, 'Come and make commercials and make some money' because I owed money left and right and centre."[10] He directed many television commercials for RSA while also overseeing the company's operation while his brother was developing his feature film career. "My goal was to make films but I got sidetracked into commercials and then I took off. I had 15 years [making them], and it was a blast. We were very prolific, and that was our training ground. You'd shoot 100 days in a year, then we gravitated from that to film," he said.[10] Developing his own distinctive visual style while making commercials, Scott states, "I cornered the market in sexy, rock'n'roll stuff."[1]

Scott took time out in 1975 to direct a television adaptation of the Henry James story The Author of Beltraffio.[13] After the feature film successes of fellow British directors Hugh Hudson, Alan Parker, Adrian Lyne and his elder brother during the late 1970s, all of whom had graduated from directing advertising commercials, he received initial overtures from Hollywood in 1980. His eldest brother Frank died, aged 45, of skin cancer during the same year.[14]

Early films

[edit]Scott reflected on his career in 2009:[15]

The '80s was a whole era. We were criticised, we being the Brits coming over, because we were out of advertising—Alan Parker, Hugh Hudson, Adrian Lyne, my brother—we were criticised about style over content. Jerry Bruckheimer was very bored of the way American films were very traditional and classically done. Jerry was always looking for difference. That's why I did six movies with Jerry. He always applauded the way I wanted to approach things. That period in the '80s was a period when I was constantly being criticised, and my press was horrible. I never read any press after The Hunger.

Scott persisted in trying to embark on a feature film career. Among the ideas interesting to him was an adaptation of the Anne Rice novel Interview with the Vampire then in development.[16] MGM was already developing the vampire film The Hunger, and hired Scott as director in 1982. Despite starring David Bowie, Susan Sarandon and Catherine Deneuve, and having elaborate production design, it failed to find an audience or to impress the critics although it later became a cult favourite.[17][18][19] Finding few film opportunities in Hollywood over the next two and a half years, Scott returned to commercials and music videos.[17]

In 1985, producers Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer collaborated with Scott to direct Top Gun, having been impressed by The Hunger, and a commercial he had done for Swedish automaker Saab in 1983 featuring a Saab 900 racing a Saab 37 Viggen fighter jet.[1][20] Scott, initially reluctant, finally agreed to direct Top Gun. While the film received mixed critical reviews, it was a box office smash, becoming the highest-grossing film of 1986, taking in more than $350 million, and making a star of its young protagonist, Tom Cruise.[17][21] Labelling Top Gun "the key 1980s movie made by the British ad invasion", Sam Delaney of The Guardian writes, "By the mid-80's, Hollywood was awash with British directors who had ushered in a new era of blockbusters using the crowd-pleasing skills they'd honed in advertising. The vast resources and freedom made available to ad directors during advertising's boom era during the 1970's enabled them to innovate and experiment with new techniques that weren't then possible in TV or film."[1]

Hollywood success

[edit]Following the stellar success of Top Gun, Scott found himself on Hollywood's A-list of action directors.[21] He collaborated again with Simpson and Bruckheimer in 1987 to direct Eddie Murphy and Brigitte Nielsen in the highly anticipated sequel Beverly Hills Cop II. It left critics underwhelmed, but was among the year's highest-grossing films.[17] That year, in 1987, Tony Scott had signed a deal with Paramount Pictures to develop films for a non-exclusive agreement, which will serve as producers and directors on the studio.[22] His next feature, Revenge (1990), a thriller of adultery and revenge set in Mexico, starred Kevin Costner, Madeleine Stowe and Anthony Quinn. Once again directing Tom Cruise, Scott returned to the Simpson-Bruckheimer fold to helm the big-budget racing film Days of Thunder (1990). Scott later stated that it was difficult to find the drama in racing cars in circles, so he "stole from all race movies to date ... then tried to build on them."[23] Scott's next film was the cult action thriller The Last Boy Scout (1991) starring Bruce Willis and Damon Wayans and written by Shane Black.

In 1993, Scott directed True Romance costing just $13 million, from a script by Quentin Tarantino.[24] The cast included Christian Slater, Patricia Arquette, Dennis Hopper, Christopher Walken, Gary Oldman, Brad Pitt, Tom Sizemore, Chris Penn, Val Kilmer, James Gandolfini and Samuel L. Jackson. Although it received positive reviews from Janet Maslin and other critics, it earned less than it cost to make and was considered a box office failure, although it has since attained cult status.[17] For his next film, Crimson Tide (1995), Scott again teamed up with producers Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer. A submarine thriller starring Denzel Washington and Gene Hackman, it was critically and commercially well-received. It marked the first of five collaborations with Washington.

In 1995, Shepperton Studios was purchased by a consortium headed by Tony and Ridley Scott, which extensively renovated the studios – located in Britain – while also expanding and improving its grounds.[25] In 1996, Scott directed The Fan, starring Robert De Niro, Wesley Snipes, Ellen Barkin and Benicio del Toro. His 1998 film Enemy of the State, a conspiracy thriller, starred Will Smith and Gene Hackman, and was his highest-grossing film of the decade.[17] Spy Game was released in November 2001, and garnered 63% positive reviews at Metacritic and topped $60 million at the U.S. box office. Scott subsequently directed another thriller starring Denzel Washington, Man on Fire, released in April 2004.

Tony collaborated with Ridley to co-produce the TV series Numb3rs, which aired from 2005 to 2010, with Tony directing the first episode of the fourth season.[23][26] In 2006, he contributed voice-over to a song called Dreamstalker on Hybrid's album I Choose Noise; Scott collaborated with Hybrid on several films through their mutual friend, the highly successful film score composer Harry Gregson-Williams.

In 2005, Tony Scott directed Domino, starring Keira Knightley.[27] While notable for its use of experimental film techniques, it was drubbed by critics and rejected by audiences. In autumn 2006, Scott again worked with Denzel Washington, this time on a sci-fi action film, Déjà Vu.[28] The two collaborated again on The Taking of Pelham 123, a remake of the 1974 film of the same title, and which also starred John Travolta. It was released on 12 June 2009.[29] In 2009, Tony and Ridley Scott were executive producers for The Good Wife, a legal drama television series.[30]

In 2010, the Scott brothers produced the feature film adaptation of the television series The A-Team.[31] The same year, Scott collaborated again with Denzel Washington on Unstoppable, which also starred Chris Pine, and hit the screens in November.[32]

Shortly before his death, Tony Scott produced Coma, a medical thriller miniseries, the Coca-Cola short film The Polar Bears and the thrillers Stoker and The East, the latter two with his brother, Ridley.[33]

Unrealised projects

[edit]Tom Cruise was with Scott just two days prior to the director's suicide, scouting locations for a sequel to Top Gun, scheduled for production in 2013.[34] In December 2012, Paramount announced that the project was officially cancelled, but they would go ahead with a 3D IMAX remastering of the original Top Gun, which was released on 8 February 2013.[35] In June 2013, it was confirmed by Bruckheimer that Top Gun 2 had been greenlighted once again, with Joseph Kosinski announced as the project's new director in June 2017.[36] The film, Top Gun: Maverick, was released on 27 May 2022, and was both a critical and financial success, and is the second-highest grossing film of 2022. Top Gun: Maverick was posthumously dedicated to Scott.

At the time of his death, Scott was also slated to direct Narco Sub, from a script by David Guggenheim and Mark Bomback, about "a disgraced American naval officer forced to pilot a sub carrying a payload of cocaine to America", and the action film Lucky Strike, with Vince Vaughn slated to star.[34][37] Scott also considered a remake of the classic western The Wild Bunch (1969), and an adaptation of the comic book limited series Nemesis by Mark Millar.[34][38]

Directing style

[edit]Katey Rich of Cinema Blend wrote that Scott had a "trademark frenetic camera style",[39] which Scott spoke about in June 2009, in reference to The Taking of Pelham 123:

It's about energy and it's about momentum, and I think the movie's very exciting, and it's not one individual thing. The true excitement comes from the actors—that gives you the true drama—and whatever I can do with the camera, that's icing on the cake. I wanted the movie to grab you. I use four cameras and I maybe do three takes—so the actors love it. Maybe I move it more than I should, but that's the nature of the way I am.[15]

Scott also spoke about his career in general:

What always leads me in terms of my movies are characters. [I tell my production team] 'Go into the real world, cast these people in the real world, and find me role models for my writers.' Then I reverse-engineer. I don't change the structure of the script, but I use my research. That's always been my mantra, and that's what gets me excited, because I get to educate and entertain myself in terms of worlds I could never normally touch, other than the fact that I'm a director. [...] If you look at my body of work, there's always a dark side to my characters. They've always got a skeleton in the closet, they've always got a subtext. I like that. Whether it's Bruce Willis in Last Boy Scout or Denzel Washington in The Taking of Pelham 123. I think fear, and there's two ways of looking at fear. The most frightening thing I do in my life is getting up and shooting movies. Commercials, movies, every morning I'm bolt upright on one hour two hours sleep, before the alarm clock goes off. That's a good thing. That fear motivates me, and I enjoy that fear. I'm perverse in that way. I do other things. I've rock climbed all my life. Whenever I finish a movie, I do multi-day ascents, I go hang on a wall in Yosemite. That fear is tangible. That's black and white. I can make this hold or that hold. The other fear is intangible, it's very abstract, and that's more frightening.[15]

Manohla Dargis of The New York Times wrote that Scott was "one of the most influential film directors of the past 25 years, if also one of the most consistently and egregiously underloved by critics" and called him "[o]ne of the pop futurists of the contemporary blockbuster."[40] She felt that "[t]here was plenty about his work that was problematic and at times offensive, yet it could have terrific pop, vigour, beauty and a near pure cinema quality. These were, more than anything, films by someone who wanted to pull you in hard and never let you go."[40]

Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly wrote that "the propulsive, at times borderline preposterous popcorn-thriller storylines; the slice-and-dice editing and the images that somehow managed to glow with grit; the fireball violence, often glimpsed in smeary-techno telephoto shots; the way he had of making actors seem volatile and dynamic and, at the same time, lacking almost any subtext" were qualities of Scott's films that both "excited audiences about his work" and "kept him locked outside the gates of critical respectability."[41]

Todd McCarthy of The Hollywood Reporter wrote that after Top Gun, Scott "found his commercial niche as a brash, flashy, sometimes vulgar action painter on celluloid," citing Beverly Hills Cop II, Days of Thunder, The Last Boy Scout, True Romance, and The Fan as examples.[42] McCarthy concluded that Unstoppable, Scott's final film, was one of his best. Apart from having "its director's fingerprints all over it—the commitment to extreme action, frenetic cutting, stripped-down dialogue"—McCarthy found "a social critique embedded in its guts; it was about disconnected working class stiffs living marginal lives on society's sidings, about the barely submerged anger of a neglected underclass," something which "always had been lacking from Tony Scott's work, some connection to the real world rather than just silly flyboy stuff and meaningful glances accompanied by this year's pop music hit."[42] Betsy Sharkey of The Los Angeles Times wrote that Denzel Washington—who starred in Crimson Tide, Man on Fire, Déjà Vu, The Taking of Pelham 123, and Unstoppable—was Scott's muse, and Scott "was at his best when Washington was in the picture. The characters the actor played are the archetype of the kind of men Scott made. At their core, and what guided all the actions that followed, was a fundamental decency. They were flawed men to be sure, some more than others, but men who accorded dignity to anyone who deserved it."[43]

Personal life

[edit]Scott married three times. His first marriage was to TV production designer Gerry Boldy (1944–2007) in 1967; they were divorced in 1974.[44] His second marriage was in 1986 to advertising executive Glynis Sanders;[45] they divorced a year later when his affair with Brigitte Nielsen (married to Sylvester Stallone at the time), whom he met on the set of Beverly Hills Cop II, became public.[citation needed] He subsequently met film and TV actress Donna Wilson on the set of Days of Thunder in 1990 and they married in 1994. She gave birth to their twin sons in 2000.[46]

Death

[edit]

On 19 August 2012, at approximately 12:30 pm PDT, Scott jumped to his death from the Vincent Thomas Bridge in the San Pedro port district of Los Angeles.[47] Investigators from the Los Angeles Police Department's Harbor Division found contact information in a note left in his car, parked on the bridge,[48] and a note at his office for his family.[49][50] One witness said he did not hesitate before jumping, but another said he looked nervous before climbing a fence, hesitating for two seconds before jumping. He landed beside a tour boat.[51][48][52] His body was recovered from the water by the Los Angeles Port Police.[6] On 22 August, Los Angeles County coroner's spokesman Ed Winters said the two notes Scott left behind made no mention of any health problems,[53] but neither the police nor the family disclosed the content of those notes.[54]

On 22 October 2012, the Los Angeles County Coroner's Office announced the cause of death as "multiple blunt force injuries". Therapeutic levels of the antidepressant mirtazapine and the sleep aid eszopiclone were in his system at the time of death.[55] A coroner's official said Scott "did not have any serious underlying medical conditions" and that there was "no anatomic evidence of neoplasia [cancer] identified".[56]

In a November 2014 interview with Variety, Ridley Scott described his brother's death as "inexplicable", saying that Tony had been "fighting a lengthy battle with cancer—a diagnosis the family elected to keep private during his treatments and in the immediate wake of his death", yet mentioning "his recovery".[57] A November 2023 profile of Ridley Scott by The New Yorker mentions that Tony Scott called his brother, who was filming in France, moments before jumping from the bridge. Noticing that he was downbeat but unaware of the situation Tony was facing, Ridley tried to energize him about work: "I said, 'Have you made your mind up about this film yet? Get going! Let's get you into a movie.'"[58]

Funeral and legacy

[edit]The family established a scholarship fund at the American Film Institute in Scott's name, stating, "The family ask that in lieu of flowers, donations be made to the fund to help encourage and engage future generations of filmmakers."[59] He was cremated and his ashes were interred at Hollywood Forever Cemetery on 24 August in Los Angeles. He left his estate to his family trust.[60][61]

Many actors paid tribute to him, including Tom Cruise, Christian Slater, Val Kilmer, Eddie Murphy, Denzel Washington, Gene Hackman, Elijah Wood, Dane Cook, Dwayne Johnson, Stephen Fry, Peter Fonda and Keira Knightley,[62][63] as well as musical collaborators Hybrid.[64] Cruise complimented Scott as "a creative visionary whose mark on film is immeasurable."[62] Denzel Washington, Scott's most frequent acting collaborator, said, "Tony Scott was a great director, a genuine friend and it is unfathomable to think that he is now gone." Directors UK chairman Charles Sturridge said Scott was "a brilliant British director with an extraordinary ability to create energy on screen, both in action and in the creation of character."[65]

The first episode of Coma and the first episode of season 4 of The Good Wife were dedicated to his memory, as were his brother Ridley's films The Counselor and Exodus: Gods and Kings.[66] Ridley also paid tribute to Tony at the 2016 Golden Globes, after his film, The Martian, won Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy.[67]

The end credits of Top Gun: Maverick (2022) include a dedication to Scott.[68] Lady Gaga's performance of the film's Academy Award-nominated song "Hold My Hand" at the 95th Academy Awards likewise included a tribute to the late director.[69] He had been working on early drafts of the film before his death.

Filmography

[edit]Films

[edit]- Feature films

| Year | Title | Director | Producer |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1983 | The Hunger | Yes | No |

| 1986 | Top Gun | Yes | No |

| 1987 | Beverly Hills Cop II | Yes | No |

| 1990 | Revenge | Yes | No |

| Days of Thunder | Yes | No | |

| 1991 | The Last Boy Scout | Yes | No |

| 1993 | True Romance | Yes | No |

| 1995 | Crimson Tide | Yes | No |

| 1996 | The Fan | Yes | No |

| 1998 | Enemy of the State | Yes | No |

| 2001 | Spy Game | Yes | No |

| 2004 | Man on Fire | Yes | Yes |

| 2005 | Domino | Yes | Yes |

| 2006 | Déjà Vu | Yes | No |

| 2009 | The Taking of Pelham 123 | Yes | Yes |

| 2010 | Unstoppable | Yes | Yes |

Mid-length films

| Year | Title | Director | Writer | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | Loving Memory | Yes | Yes | Also cinematographer and editor |

| 1976 | The Author of Beltraffio | Yes | No | Produced for the French television anthology series Nouvelles de Henry James |

Short films

| Year | Title | Director | Producer | Writer | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1969 | One of the Missing | Yes | No | Yes | Also cinematographer and editor |

| 2002 | Beat the Devil | Yes | Executive | No | Segment of The Hire |

| 2004 | Agent Orange | Yes | No | No | Part of the Amazon Theater suite of short films |

| 2012 | The Polar Bears | No | Yes | No |

Television

[edit]Director

| Year | Title | Episodes |

|---|---|---|

| 1997–1999 | The Hunger | "The Swords" and "Sanctuary" |

| 2007 | Numb3rs | "Trust Metric" |

Executive producer

- AFP: American Fighter Pilot (2002)

- The Gathering Storm (2002)

- The Good Wife (2009–12)

- Gettysburg (2011)

- Labyrinth (2012)

- World Without End (2012)

- Killing Lincoln (2013)

Others

[edit]- Music videos

- "Danger Zone" – Kenny Loggins (1986)

- "Father Figure" – George Michael (1987) directed by Andy Morahan, the love scene shot by Tony Scott

- "One More Try" – George Michael (1988)

- Commercials

- DIM Underwear (1979)

- SAAB (1984) "Nothing on Earth Comes Close"

- Player, Achievements and Big Bang for Barclays Bank (2000)

- Telecom Italia (2000) (Starring Marlon Brando and Woody Allen)

- Ice Soldier for US Army (2002)

- One Man, One Land for Marlboro (2003)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Jets, jeans and Hovis". The Guardian. 12 June 2015.

- ^ "Outstanding British Contribution To Cinema". BAFTA. 13 October 2015.

- ^ Sullivan, Michael (17 September 2010). "BAFTA/LA to honor Scott Free Prods". Variety . Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ "Anthony D L Scott: England and Wales Birth Registration Index". Family Search.org.

- ^ "Tony Scott: tragic illness behind Top Gun director's suicide". No. 20 August 2012. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- ^ a b Blankenstein, Andrew; Horn, John (19 August 2012). "'Top Gun' director Tony Scott jumps to his death from L.A. bridge". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 20 August 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ "How Winston helped save the nation". The Scotsman. 6 July 2002. Archived from the original on 11 May 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ Hodgson, Barbara (16 February 2018). "Who is Ridley Scott? Read our guide to the North East-born star as he receives top award". Chronicle. Newcastle: chroniclelive.co.uk. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ "Tony Scott". The Telegraph. London. 20 August 2012. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ a b c Galloway, Stephen (22 August 2012). "Tony Scott's Unpublished Interview: 'My Family Is Everything to Me'". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ "Ten Things About... Ridley Scott". Digital Spy. 19 December 2016.

- ^ Ridley Scott's comment on The Directors—The Films of Ridley Scott.

- ^ Tony Scott obituary. The Guardian. Retrieved 21 August 2012

- ^ Harper, Tom; Jury, Louise (20 August 2012). "Hollywood pays tribute to Top Gun director Tony Scott following suicide leap". Evening Standard. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- ^ a b c Rich, Katey (12 June 2009). "Interview: Tony Scott". Cinema Blend. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ White, James (20 August 2012). "Tony Scott Dies". Empire. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Makinen, Julie; Boucher, Geoff (20 August 2012). "Tony Scott dies at 68; a film career in retrospective". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 20 August 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ "Tony Scott Obituary". The Guardian.

- ^ Wicks, Kevin (20 August 2012). "British Director Tony Scott Dead in Apparent Suicide at 68". BBC America. Archived from the original on 21 August 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "SAAB – 'Nothing On Earth Comes Close'". YouTube. 30 September 2006.

- ^ a b "Obituary: Tony Scott". BBC News. 20 August 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ^ "Paramount Signs Scott To Nonexclusive Deal". Variety. 14 October 1987. p. 4.

- ^ a b "Authorities say 'Top Gun' director Tony Scott dies after jumping off Los Angeles County bridge". The Washington Post. Associated Press. 19 August 2012. Archived from the original on 21 August 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ Shoard, Catherine (20 August 2012). "Tony Scott: a career in clips". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ^ "History of Shepperton Studios" (PDF). pinewoodgroup.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2008.

- ^ "Numb3rs Season 4, Episode 1: Trust Metric". IMDb. Archived from the original on 24 August 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ "Domino". IMDb. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ "Déjà Vu". IMDb. Archived from the original on 21 August 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ "The Taking of Pelham 1 2 3". IMDb. Archived from the original on 17 July 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ "Full Cast and Crew for 'The Good Wife'". IMDb. Archived from the original on 11 February 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ "The A-Team". IMDb. Archived from the original on 7 March 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ "Unstoppable". IMDb. Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ Marroquin, Art (19 August 2012). "BREAKING: Film director Tony Scott jumps to his death from Vincent Thomas Bridge". Los Angeles Daily News. Archived from the original on 23 August 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ a b c McClintock, Pamela (20 August 2012). "Tony Scott Spent Final Days Working With Tom Cruise on 'Top Gun 2'". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ "For the Very First Time TOP GUN to be Released In IMAX® 3D" Archived 14 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine. IMAX.com. Retrieved 29 June 2014

- ^ McNary, Dave (30 June 2017). "Tom Cruise's 'Top Gun' Sequel Gets July 2019 Release Date". Variety. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (21 August 2012). "Tony Scott Got Close To Production On 'Lucky Strike'". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (6 August 2010). "Fox And Tony Scott Plot Movie Version of Millar & McNiven's 'Nemesis'". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- ^ Rich, Katey (20 August 2012). "Remembering Tony Scott, In His Own Words". Cinema Blend. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ a b Dargis, Manohla (20 August 2012). "A Director Who Excelled in Excess". The New York Times. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (21 August 2012). "Was Tony Scott a good director? It depends on what your definition of good is". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ a b McCarthy, Todd (22 August 2012). "Todd McCarthy: How Tony Scott Finally Won Me Over". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ Sharkey, Betsy (24 August 2012). "Tony Scott, a man of action who brought out the best in his men". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ Stafford-Clark, Nigel (12 May 2007). "Obituary: Gerry Scott Foulds". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ^ Hough, Andrew; Allen, Nick (20 August 2012). "Top Gun director Ton y Scott dies after jumping from Los Angeles bridge". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ "Hollywood pays tribute to Top Gun director Tony Scott following suicide leap". London Evening Standard. 20 August 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ^ Jessop, Andy (20 August 2012). "Tony Scott Dies After Bridge Plunge". Lifestyleuncut.com. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ a b Blankstein, Andrew (19 August 2012). "'Top Gun' director Tony Scott dead after jumping off bridge". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ "Tony Scott, Director of 'Top Gun,' Dies in Apparent Suicide". The Wrap. The Wrap News Inc. 19 August 2012. Archived from the original on 10 February 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ^ Geier, Thom (20 August 2012). "'Top Gun' director Tony Scott dies at age 68 in apparent suicide". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 20 August 2012. Retrieved 20 August 2012.

- ^ "Tony Scott death: Director 'looked nervous' before jumping off bridge". 20 August 2012.

- ^ Louise Boyle (19 August 2012).

- ^ "Tony Scott Laid to Rest in Los Angeles". The Hollywood Reporter. 24 August 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ Winton, Richard; Blankstein, Andrew (25 August 2012). "Tony Scott death: Director laid to rest as questions remain". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ^ Pelisek, Christine (22 October 2012). "Antidepressant, Sleep Aid Found in Director Tony Scott's Body". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- ^ "Director Tony Scott had no serious medical conditions, coroner says". Los Angeles Times. 22 October 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- ^ Foundas, Scott (25 November 2014). "Exodus: Gods and Kings' Director Ridley Scott on Creating His Vision of Moses". Variety. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ Schulman, Michael (6 November 2023). "Ridley Scott's "Napoleon" Complex". The New Yorker. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ Miller, Daniel (27 August 2012). "Tony Scott Family Establishes AFI Scholarship". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- ^ "Tony Scott's Will Leaves Entire Fortune to Wife and Kids". TMZ. 21 September 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ Tony Scott Laid to Rest in Los Angeles

- ^ a b "Tom Cruise leads tributes to director Tony Scott". BBC News; retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ^ "Hollywood reacts to the death of Tony Scott"[dead link], Associated Press; retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ^ "Film Director Tony Scott: In Remembrance". Hybridsoundsystem.com. 21 August 2012. Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ "Tony Scott dies aged 68", DirectorsUK.com; retrieved 29 August 2012.

- ^ Dayoub, Tony (27 October 2013). "Double Vision: Tony Scott's Spirit Possesses Ridley Scott's The Counselor". rogerebert.com.

- ^ "Golden Globes 2016 ceremony – in pictures". The Guardian. 9 February 2016.

- ^ Chuba, Kirsten (1 June 2022). "'Top Gun: Maverick' Pays Tribute to Late Director Tony Scott". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- ^ Garcia, Thania (13 March 2023). "Watch Lady Gaga Strip Down 'Hold My Hand' in an Intimate Oscars Performance Dedicated to Tony Scott". Variety. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Gerosa, Mario ed. (2014). Il cinema di Tony Scott. Il Foglio. ISBN 9788876064814.

External links

[edit]- Tony Scott at IMDb

Tony Scott

View on GrokipediaBiography

Early life

Tony Scott was born on 21 June 1944 in North Shields, Northumberland, England, the youngest of three sons to Elizabeth Jean Scott and Colonel Francis Percy Scott, who served in the Royal Engineers during World War II.[2][6] His elder brothers were film director Ridley Scott and merchant seaman Frank Scott. His family, rooted in working-class origins, experienced frequent relocations due to his father's military postings, including time in other parts of northern England amid the wartime disruptions of bombing raids and rationing.[7] Scott shared a close bond with his older brother Ridley Scott, seven years his senior, who profoundly influenced his budding interest in art and visual storytelling; the siblings bonded over shared childhood hobbies such as drawing, painting, and rudimentary photography, fostering Tony's creative inclinations from a young age.[7] He attended Rosebank School in Hartlepool during his early education, followed by Grangefield School in Stockton-on-Tees, where the family settled after the war.[2][8] Lacking formal training in film, Scott developed his artistic skills through structured art education, studying at West Hartlepool College of Art and earning a fine arts degree from Sunderland Art School before graduating from the Royal College of Art in London, initially aspiring to become a painter.[9][2] In the early 1960s, Scott pursued initial creative endeavors through practical work in design and production, including roles as a trainee set designer for the BBC, where he contributed to high-profile television series by painting and constructing sets—experiences that honed his visual and technical abilities ahead of his entry into advertising and filmmaking.[2] These formative jobs in graphic design and theater-related production marked his transition from fine arts to applied visual media, laying the groundwork for his later professional path without direct film education.[9]Personal life

Scott was married three times. His first marriage was to production designer Gerry Boldy in 1967; the couple divorced in 1974 with no children from the union.[10] His second marriage, to Glynis Sanders, lasted from 1986 to 1987 and also ended in divorce.[2][6] In 1994, he married actress and producer Donna Wilson, who occasionally appeared in small roles in his films; the couple remained together until his death.[2] With Donna Wilson, Scott had twin sons, Frank and Max, born in 2000.[11] The family resided primarily in Los Angeles, where Scott enjoyed a close-knit domestic life centered around raising his young sons while balancing his demanding career.[9] After relocating from the United Kingdom to the United States in the 1980s to pursue feature film opportunities, Scott established long-term residences in Southern California. He owned the historic Bella Vista estate in Beverly Hills starting in 1992, a sprawling Mediterranean-style compound previously home to Hollywood luminaries.[12] The family also maintained a beachfront home in the exclusive Malibu Colony enclave, providing a coastal retreat.[13] Scott's non-professional interests reflected his adventurous spirit and artistic background. A lifelong rock climber, he maintained a passion for the outdoors throughout adulthood.[2] He was an enthusiast of fast cars and motorcycles, often incorporating high-speed pursuits into his films while enjoying them personally.[2] His close relationship with older brother Ridley Scott, also a prominent director, extended to family matters, including shared collaborations and mutual support.[9]Film career

Commercials and early work

Tony Scott began his professional career in the late 1960s in London, apprenticing under his older brother Ridley at the advertising agency Ridley Scott Associates (RSA), which the brothers co-founded in 1968. Initially, Scott contributed as a production designer and assistant director, handling tasks such as insert shots for Ridley's commercials, honing his skills in visual storytelling and high-speed cinematography techniques that would become hallmarks of his work.[14][15] Scott directed his first credited commercial in 1979 for the DIM Underwear brand, marking his transition to lead directing roles. By the 1980s, he had rapidly risen in the industry, helming thousands of television commercials for major brands including Levi's, Pepsi (such as the 1978 "Lipsmackin' Thirst" campaign), and Barclays Bank (featuring Anthony Hopkins in spots like "Big" in 2000). In 1980, alongside Ridley, he co-founded Percy Main Productions—named after their father's hometown in England—as a vehicle for feature film development, producing key advertising campaigns that showcased innovative effects, including his assistant role on the follow-up to Ridley's iconic 1984 Apple Macintosh "1984" ad, the 1985 "Lemmings" spot.[16][17][18] In addition to commercials, Scott ventured into early television and music video work in the 1980s and 1990s, directing episodes of the anthology series The Hunger (1997), including the premiere "The Swords," which he co-produced through Scott Free (the evolved form of Percy Main). He also helmed music videos such as Kenny Loggins' "Danger Zone" (1986) for the Top Gun soundtrack and George Michael's "One More Try" (1988). These projects provided a foundation for narrative experimentation that briefly influenced his approach to feature films. Seeking larger opportunities, Scott relocated to Hollywood in the early 1980s, leveraging his commercial success to debut in features with The Hunger (1983).[19][20]Feature films

Tony Scott directed sixteen feature films from 1983 to 2010, spanning genres such as action, thriller, and drama. These works established him as a prominent director of high-octane Hollywood productions, often featuring ensemble casts and collaborations with notable composers. The following table summarizes his directorial credits, including key starring actors, composer, runtime, distributor, production budget, and box office earnings where available.| Year | Title | Starring | Composer | Runtime (min) | Distributor | Budget | Domestic Gross | Worldwide Gross |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1983 | The Hunger | Catherine Deneuve, David Bowie, Susan Sarandon | Michel Rubini | 97 | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer | N/A | $5,979,292 | $10,279,292 |

| 1986 | Top Gun | Tom Cruise, Kelly McGillis, Val Kilmer, Anthony Edwards | Harold Faltermeyer | 110 | Paramount Pictures | $15 million | $180,470,489 | $357,463,748 |

| 1987 | Beverly Hills Cop II | Eddie Murphy, Judge Reinhold, Brigitte Nielsen, Jürgen Prochnow | Harold Faltermeyer | 102 | Paramount Pictures | $20 million | $153,665,036 | $276,665,036 |

| 1990 | Revenge | Kevin Costner, Anthony Quinn, Madeleine Stowe, Miguel Ferrer | Jack Nitzsche | 124 | Columbia Pictures | $34 million | $15,535,771 | $46,305,000 |

| 1990 | Days of Thunder | Tom Cruise, Robert Duvall, Nicole Kidman, Randy Quaid | Hans Zimmer | 107 | Paramount Pictures | $60 million | $82,670,733 | $157,670,733 |

| 1991 | The Last Boy Scout | Bruce Willis, Damon Wayans, Halle Berry, Chelsea Field | Michael Kamen | 105 | Warner Bros. | $29 million | $59,509,925 | $114,509,925 |

| 1993 | True Romance | Christian Slater, Patricia Arquette, Dennis Hopper, Val Kilmer | Hans Zimmer | 120 | Warner Bros. | $12.5 million | $12,281,000 | $12,643,293 |

| 1995 | Crimson Tide | Denzel Washington, Gene Hackman, George Dzundza, Viggo Mortensen | Hans Zimmer | 116 | Hollywood Pictures | $53 million | $91,387,195 | $159,387,195 |

| 1996 | The Fan | Robert De Niro, Wesley Snipes, Ellen Barkin, John Leguizamo | Hans Zimmer | 116 | Miramax Films | $55 million | $18,582,965 | $18,665,000 |

| 1998 | Enemy of the State | Will Smith, Gene Hackman, Jon Voight, Regina King | Trevor Rabin, Harry Gregson-Williams | 132 | Buena Vista Pictures | $90 million | $111,549,836 | $250,649,836 |

| 2001 | Spy Game | Robert Redford, Brad Pitt, Catherine McCormack, Stephen Dillane | Harry Gregson-Williams | 126 | Universal Pictures | $92 million | $62,362,560 | $143,049,560 |

| 2004 | Man on Fire | Denzel Washington, Dakota Fanning, Christopher Walken, Radha Mitchell | Harry Gregson-Williams | 146 | 20th Century Fox | $60 million | $77,906,816 | $130,968,579 |

| 2005 | Domino | Keira Knightley, Mickey Rourke, Edgar Ramírez, Delroy Lindo | Harry Gregson-Williams | 127 | New Line Cinema | $50 million | $10,169,202 | $23,574,057 |

| 2006 | Déjà Vu | Denzel Washington, Paula Patton, Val Kilmer, Jim Caviezel | Harry Gregson-Williams | 126 | Buena Vista Pictures | $75 million | $64,038,616 | $181,038,616 |

| 2009 | The Taking of Pelham 123 | Denzel Washington, John Travolta, James Gandolfini, Luis Guzmán | Harry Gregson-Williams | 106 | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer / Columbia Pictures | $100 million | $65,452,312 | $152,364,370 |

| 2010 | Unstoppable | Denzel Washington, Chris Pine, Rosario Dawson, Ethan Suplee | Harry Gregson-Williams | 98 | 20th Century Fox | $100 million | $81,562,942 | $167,720,921 |

Directing style

Tony Scott's directing style was characterized by a signature visual aesthetic that emphasized high-contrast lighting, Dutch angles, rapid cuts, and handheld camera work, often drawing from his background in commercials to create a dynamic, immersive experience. High-contrast lighting, frequently achieved through tactical shafts of light and desaturated palettes, heightened tension in films like Crimson Tide (1995), where it underscored submarine claustrophobia. Dutch angles and handheld shots added disorientation and urgency, as seen in the frenetic sequences of True Romance (1993), while rapid cuts—sometimes flash-forward bursts—propelled the narrative forward with MTV-like intensity. Slow-motion effects, influenced by advertising techniques, intensified subjective moments, such as aerial dogfights in Top Gun (1986), and lens flares, ubiquitous in The Hunger (1983), contributed to a glossy, sensory overload.[16][33][34] Thematically, Scott's films featured hyper-masculine action heroes navigating moral ambiguity, often exploring loyalty, revenge, and the perils of technology. Protagonists like the pilots in Top Gun embodied rugged masculinity amid high-stakes loyalty tests, while thrillers such as Enemy of the State (1998) delved into surveillance technology's invasive dangers, blurring lines between heroism and paranoia. Moral complexity permeated revenge-driven narratives, as in Man on Fire (2004), where vigilante justice raised ethical questions about retribution. These elements reflected a worldview of interpersonal bonds under duress, with technology frequently portrayed as a double-edged sword threatening personal agency.[16][33][35] Scott pioneered technical innovations, including early adoption of digital effects and nonlinear storytelling, while favoring practical stunts to maintain authenticity. In Spy Game (2001), he integrated digital enhancements for seamless flashbacks, marking a shift toward hybrid analog-digital workflows. Déjà Vu (2006) employed nonlinear structures to manipulate time perception, using practical effects for time-travel sequences that grounded speculative elements. His preference for practical stunts over heavy CGI was evident in elaborate set pieces like the runaway train in Unstoppable (2010), where real locomotives and pyrotechnics amplified visceral impact.[16][33][36] Scott's style evolved from the polished, commercial aesthetics of Top Gun, with its sleek aerial cinematography, to the gritty, experimental visuals in later works like Domino (2005), featuring cross-processing and feverish desaturation for a raw, documentary edge. This progression mirrored influences from his brother Ridley Scott's atmospheric precision and Michael Mann's stylized urban action, transitioning from blockbuster sheen to avant-garde experimentation in the 2000s.[16][33][37] Critically, Scott's approach was derided as "MTV-style" excess by detractors for its rapid editing and sensory bombardment, yet praised for its visceral energy that redefined action cinema. Posthumously, following his 2012 death, reevaluation positioned him as an auteur in the genre, with scholars highlighting his innovative "audio-visual experience" and influence on modern blockbusters.[16][38][34]Later projects and death

Unrealized projects

Throughout his career, Tony Scott developed several ambitious film projects that advanced to various stages of pre-production but ultimately remained unrealized due to script revisions, scheduling conflicts, or his death in 2012. These efforts highlighted his interest in high-stakes action thrillers involving modern technology, criminal underworlds, and reinterpretations of classic genres. One of the most prominent was a sequel to his 1986 blockbuster Top Gun, which Scott had been developing for years with star Tom Cruise and producer Jerry Bruckheimer. The project, set to explore contemporary aerial warfare emphasizing drone technology over manned fighters, reached advanced stages by 2010, with Scott confirming plans for a "re-thinking" of the original rather than a direct follow-up.[39] Scott and Cruise were scouting locations just days before his suicide, aiming for production in early 2013 and a 2014 release through Paramount Pictures and Skydance Productions.[40] Although script issues had previously stalled earlier iterations in the late 2000s, the project was abandoned following Scott's death but later revived as Top Gun: Maverick (2022), directed by Joseph Kosinski and dedicated to his memory.[41] In 2011, Scott attached himself to direct Narco Sub, an action thriller scripted by David Guggenheim about a high-tech submarine used for smuggling drugs from Latin America to the U.S., produced by Simon Kinberg for 20th Century Fox. The project had been in development for months, with Guggenheim refining the script over eight months prior to Scott's involvement.[42] It represented Scott's return to nautical themes after films like Crimson Tide (1995), but stalled after his death and saw directors like Doug Liman and Antoine Fuqua briefly attached before being shelved.[43] Scott was also nearing production on Lucky Strike, a $80 million action drama written by Henry Bean, in which a DEA agent partners with a notorious drug lord to dismantle a cartel. Potential stars included Mark Wahlberg and Vince Vaughn, with the film eyed for a late 2012 shoot at 20th Century Fox.[44] The script's focus on uneasy alliances and high-tension pursuits aligned with Scott's signature style of kinetic, character-driven action, but it was ultimately abandoned following his passing. Additionally, Scott entered talks in 2011 to helm a remake of Sam Peckinpah's 1969 Western The Wild Bunch, with L.A. Confidential screenwriter Brian Helgeland penning a contemporary update of the story about aging outlaws on one final heist. Helgeland, a frequent collaborator who had worked on Scott's Man on Fire (2004), aimed to reimagine the film's violent themes for a modern audience.[45] No studio was formally attached, and the project dissolved after Scott's death amid ongoing debates over updating Peckinpah's gritty classic.[46] These unrealized endeavors, often entangled with studio commitments and Scott's packed schedule, underscored his drive to blend cutting-edge visuals with intense personal stakes, though personal factors and his untimely death prevented their completion.[47]Death and inquest

On August 19, 2012, Tony Scott died at the age of 68 after jumping from the Vincent Thomas Bridge in San Pedro, Los Angeles, in an apparent suicide. Authorities found his car parked on the bridge, containing several handwritten notes addressed to his family members, though the notes did not specify a motive for his actions.[48][49] The Los Angeles County Coroner's Office conducted an inquest and officially ruled the death a suicide on October 22, 2012, with the cause determined to be multiple blunt force injuries and drowning. No evidence of foul play or external involvement was identified during the investigation. The autopsy report confirmed therapeutic levels of the antidepressant mirtazapine (Remeron) and the sleep aid eszopiclone (Lunesta) in Scott's system, but found no traces of alcohol or illicit drugs.[50][51][52] Early reports following the incident suggested Scott had received a diagnosis of inoperable brain cancer earlier in 2012, with some sources speculating it as a factor in his decision, though his family immediately disputed the claims regarding its severity and existence. The coroner's final findings corroborated the family's position, revealing no evidence of cancer or other major medical conditions at the time of death. In statements to the press, Scott's family described his struggle with illness as a deeply personal matter, requesting privacy amid the tragedy.[53][54][55] Scott's sudden death elicited widespread shock in Hollywood and among the public, particularly in light of his recent directorial success with the 2010 film Unstoppable. The event immediately disrupted several of his active projects, including preparations for a 3D re-release and potential sequel to Top Gun, leaving producers to reassess their plans.[56][57][47]Legacy

Following Tony Scott's death in 2012, his brother Ridley Scott continued to lead Scott Free Productions, the company they co-founded in 1995, ensuring its ongoing success in film and television. In April 2025, Ridley Scott and Scott Free signed with Creative Artists Agency (CAA) for representation across film, TV, and other ventures, solidifying the banner's position as a prolific producer of high-profile projects.[58] Under Ridley's stewardship, Scott Free has pursued adaptations of the brothers' films into television series, reflecting the enduring commercial appeal of Tony's work.[59] A significant posthumous tribute came with the 2022 release of Top Gun: Maverick, directed by Joseph Kosinski and produced with involvement from Jerry Bruckheimer, who collaborated with Tony on the 1986 original. The sequel features a dedication to Tony Scott in its end credits, along with archival footage from the first film, honoring his visionary direction of high-octane aerial sequences.[60] The film's massive box-office success, grossing over $1.4 billion worldwide, reignited interest in the original Top Gun, introducing Tony's stylistic trademarks—such as rapid cuts and immersive action—to new audiences and affirming his foundational role in modern blockbuster cinema.[60] Tony Scott's legacy has been marked by critical reassessment in the 2010s and beyond, with retrospectives positioning him as a pioneering action stylist whose visually kinetic films anticipated post-cinematic techniques like digital effects and fragmented editing.[16] Scholarly works and articles have highlighted his influence on subsequent directors, including Christopher McQuarrie, who paid tribute to Scott during the making of Top Gun: Maverick and emulated his intense, sweat-drenched filming style in the Mission: Impossible series.[61] Similarly, David Fincher has cited Tony's aesthetic as a key influence, particularly in adopting theatrical lighting and noir elements for heightened visual tension in thrillers.[62] Posthumous recognitions include a 2023 New Yorker profile of Ridley Scott that delves into Tony's profound personal and professional impact on his brother, framing their collaborative dynamic as central to Ridley's career.[63] In 2025, TMZ's podcast series Last Days devoted an episode to Tony's life and death, exploring his high-energy filmmaking and the circumstances surrounding his passing through interviews and archival material.[64] Ridley Scott has publicly expressed ongoing grief, stating in a November 2024 interview, "I miss my brother," 12 years after Tony's suicide, underscoring the enduring emotional toll on their family.[11]Filmography

Feature films

Tony Scott directed sixteen feature films from 1983 to 2010, spanning genres such as action, thriller, and drama. These works established him as a prominent director of high-octane Hollywood productions, often featuring ensemble casts and collaborations with notable composers. The following table summarizes his directorial credits, including key starring actors, composer, runtime, distributor, production budget, and box office earnings where available.| Year | Title | Starring | Composer | Runtime (min) | Distributor | Budget | Domestic Gross | Worldwide Gross |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1983 | The Hunger | Catherine Deneuve, David Bowie, Susan Sarandon | Michael Rubini | 97 | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer | N/A | $5,979,292 | $5,991,807 |

| 1986 | Top Gun | Tom Cruise, Kelly McGillis, Val Kilmer, Anthony Edwards | Harold Faltermeyer | 110 | Paramount Pictures | $15 million | $180,470,489 | $357,463,748 |

| 1987 | Beverly Hills Cop II | Eddie Murphy, Judge Reinhold, Brigitte Nielsen, Jürgen Prochnow | Harold Faltermeyer | 102 | Paramount Pictures | $20 million | $153,665,036 | $276,665,036 |

| 1990 | Revenge | Kevin Costner, Anthony Quinn, Madeleine Stowe, Miguel Ferrer | Jack Nitzsche | 124 | Columbia Pictures | $22 million | $15,535,771 | $15,645,616 |

| 1990 | Days of Thunder | Tom Cruise, Robert Duvall, Nicole Kidman, Randy Quaid | Hans Zimmer | 107 | Paramount Pictures | $60 million | $82,670,733 | $157,670,733 |

| 1991 | The Last Boy Scout | Bruce Willis, Damon Wayans, Halle Berry, Chelsea Field | Michael Kamen | 105 | Warner Bros. | $43 million | $59,509,925 | $114,509,925 |

| 1993 | True Romance | Christian Slater, Patricia Arquette, Dennis Hopper, Val Kilmer | Hans Zimmer | 120 | Warner Bros. | $12.5 million | $12,281,000 | $12,643,293 |

| 1995 | Crimson Tide | Denzel Washington, Gene Hackman, George Dzundza, Viggo Mortensen | Hans Zimmer | 116 | Hollywood Pictures | $53 million | $91,387,195 | $159,387,195 |

| 1996 | The Fan | Robert De Niro, Wesley Snipes, Ellen Barkin, John Leguizamo | Hans Zimmer | 116 | Sony Pictures Releasing | $55 million | $18,582,965 | $18,665,000 |

| 1998 | Enemy of the State | Will Smith, Gene Hackman, Jon Voight, Regina King | Trevor Rabin, Harry Gregson-Williams | 132 | Buena Vista Pictures | $90 million | $111,549,836 | $250,649,836 |

| 2001 | Spy Game | Robert Redford, Brad Pitt, Catherine McCormack, Stephen Dillane | Harry Gregson-Williams | 126 | Universal Pictures | $92 million | $62,362,560 | $143,049,560 |

| 2004 | Man on Fire | Denzel Washington, Dakota Fanning, Christopher Walken, Radha Mitchell | Harry Gregson-Williams | 146 | 20th Century Fox | $60 million | $77,906,816 | $130,968,579 |

| 2005 | Domino | Keira Knightley, Mickey Rourke, Edgar Ramírez, Delroy Lindo | Harry Gregson-Williams | 127 | New Line Cinema | $50 million | $10,169,202 | $23,574,057 |

| 2006 | Déjà Vu | Denzel Washington, Paula Patton, Val Kilmer, Jim Caviezel | Harry Gregson-Williams | 126 | Buena Vista Pictures | $75 million | $64,038,616 | $181,038,616 |

| 2009 | The Taking of Pelham 123 | Denzel Washington, John Travolta, James Gandolfini, Luis Guzmán | Harry Gregson-Williams | 106 | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer / Columbia Pictures | $100 million | $65,452,312 | $152,364,370 |

| 2010 | Unstoppable | Denzel Washington, Chris Pine, Rosario Dawson, Ethan Suplee | Harry Gregson-Williams | 98 | 20th Century Fox | $100 million | $81,562,942 | $167,805,466 |

Television episodes

Tony Scott's foray into television directing began early in his career and resumed selectively in the late 1990s and 2000s, allowing him to infuse episodic formats with his signature high-octane visual style and thriller sensibilities. Though primarily known for feature films, Scott's TV work often served as a testing ground for thematic elements like tension, seduction, and moral ambiguity, bridging his cinematic flair to serialized narratives. His contributions emphasized dynamic pacing and atmospheric tension, particularly in anthology and procedural formats, marking a shift toward television for greater creative experimentation in his later years.[69] Scott's earliest television credit was the 1976 episode "L'auteur de Beltraffio" for the French anthology series Nouvelles d'Henry James, an adaptation of Henry James's short story about familial conflict and artistic integrity. Aired on ORTF (Office de Radiodiffusion Télévision Française), this 52-minute drama starred Tom Baker as the titular author and Georgina Hale as his wife, showcasing Scott's emerging talent for psychological depth in a constrained runtime. It represented his directorial debut in television, produced before his feature breakthrough.[70] In the late 1990s, Scott directed two episodes of the erotic horror anthology The Hunger on Showtime, expanding on the universe of his 1983 feature film of the same name. The pilot, "The Swords" (Season 1, Episode 1), aired July 20, 1997, and introduced the series' vampiric themes through a tale of seduction and betrayal, featuring David Bowie as the host and stars like Terence Stamp and Timothy Spall. Scott's direction emphasized shadowy visuals and sensual tension, setting a proof-of-concept tone for the series' blend of horror and eroticism. He returned for the Season 2 premiere, "Sanctuary" (Episode 1), aired September 9, 1999, which explored a drifter's encounter with the supernatural, starring Giovanni Ribisi and Liisa Repo-Martell alongside Bowie. These episodes highlighted Scott's ability to adapt feature-length intensity to half-hour formats, influencing the show's stylistic identity.[71][72][69] Scott's most prominent television directing credit in the 2000s was the Season 4 premiere of the CBS procedural Numb3rs, titled "Trust Metric" (Episode 1), which aired September 28, 2007. Co-produced by Scott Free Productions, the episode investigated a ship explosion and trust algorithms, guest-starring Val Kilmer (a frequent collaborator from Top Gun and True Romance) as a shadowy operative. Directed with kinetic action sequences and rapid cuts, it injected cinematic scale into the series' math-crime-solving formula, boosting viewership and exemplifying Scott's late-career pivot to television for injecting adrenaline into network drama. This marked his final directorial effort in episodic TV before focusing on producing roles in series like The Good Wife.[73][74]| Episode Title | Series | Season/Episode | Air Date | Network | Notable Cast/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L'auteur de Beltraffio | Nouvelles d'Henry James | N/A (standalone episode) | 1976 | ORTF | Tom Baker, Georgina Hale; Early psychological drama adaptation. |

| The Swords | The Hunger | S1E1 | July 20, 1997 | Showtime | David Bowie (host), Terence Stamp, Timothy Spall; Pilot establishing erotic horror tone. |

| Sanctuary | The Hunger | S2E1 | September 9, 1999 | Showtime | David Bowie (host), Giovanni Ribisi, Liisa Repo-Martell; Supernatural drifter story with thriller elements. |

| Trust Metric | Numb3rs | S4E1 | September 28, 2007 | CBS | Rob Morrow, David Krumholtz, Val Kilmer (guest); Action-infused procedural premiere. |