Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Extracellular fluid

View on Wikipedia

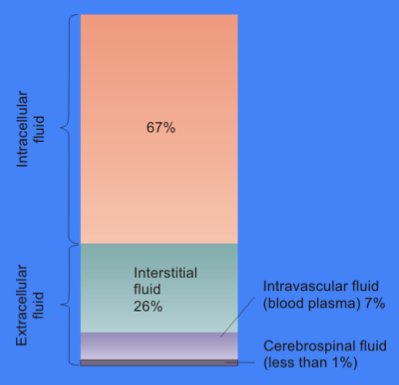

In cell biology, extracellular fluid (ECF) denotes all body fluid outside the cells of any multicellular organism. Total body water in healthy adults is about 50–60% (range 45 to 75%) of total body weight;[1] women and the obese typically have a lower percentage than lean men.[2] Extracellular fluid makes up about one-third of body fluid, the remaining two-thirds is intracellular fluid within cells.[3] The main component of the extracellular fluid is the interstitial fluid that surrounds cells.

Extracellular fluid is the internal environment of all multicellular animals, and in those animals with a blood circulatory system, a proportion of this fluid is blood plasma.[4] Plasma and interstitial fluid are the two components that make up at least 97% of the ECF. Lymph makes up a small percentage of the interstitial fluid.[5] The remaining small portion of the ECF includes the transcellular fluid (about 2.5%). The ECF can also be seen as having two components – plasma and lymph as a delivery system, and interstitial fluid for water and solute exchange with the cells.[6]

The extracellular fluid, in particular the interstitial fluid, constitutes the body's internal environment that bathes all of the cells in the body. The ECF composition is therefore crucial for their normal functions, and is maintained by a number of homeostatic mechanisms involving negative feedback. Homeostasis regulates, among others, the pH, sodium, potassium, and calcium concentrations in the ECF. The volume of body fluid, blood glucose, oxygen, and carbon dioxide levels are also tightly homeostatically maintained.

The volume of extracellular fluid in a young adult male of 70 kg (154 lbs) is 20% of body weight – about fourteen liters. Eleven liters are interstitial fluid and the remaining three liters are plasma.[7]

Components

[edit]The main component of the extracellular fluid (ECF) is the interstitial fluid, or tissue fluid, which surrounds the cells in the body. The other major component of the ECF is the intravascular fluid of the circulatory system called blood plasma. The remaining small percentage of ECF includes the transcellular fluid. These constituents are often called "fluid compartments". The volume of extracellular fluid in a young adult male of 70 kg, is 20% of body weight – about fourteen liters. [citation needed]

Interstitial fluid

[edit]Interstitial fluid is essentially comparable to plasma. The interstitial fluid and plasma make up about 97% of the ECF, and a small percentage of this is lymph. [citation needed]

Interstitial fluid is the body fluid between blood vessels and cells,[8] containing nutrients from capillaries by diffusion and holding waste products discharged by cells due to metabolism.[9][10] 11 liters of the ECF are interstitial fluid and the remaining three liters are plasma.[7] Plasma and interstitial fluid are very similar because water, ions, and small solutes are continuously exchanged between them across the walls of capillaries, through pores and capillary clefts. [citation needed]

Interstitial fluid consists of a water solvent containing sugars, salts, fatty acids, amino acids, coenzymes, hormones, neurotransmitters, white blood cells and cell waste-products. This solution accounts for 26% of the water in the human body. The composition of interstitial fluid depends upon the exchanges between the cells in the biological tissue and the blood.[11] This means that tissue fluid has a different composition in different tissues and in different areas of the body. [citation needed]

The plasma that filters through the blood capillaries into the interstitial fluid does not contain red blood cells or platelets as they are too large to pass through but can contain some white blood cells to help the immune system. [citation needed]

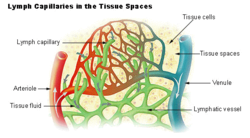

Once the extracellular fluid collects into small vessels (lymph capillaries) it is considered to be lymph, and the vessels that carry it back to the blood are called the lymphatic vessels. The lymphatic system returns protein and excess interstitial fluid to the circulation. [citation needed]

The ionic composition of the interstitial fluid and blood plasma vary due to the Gibbs–Donnan effect. This causes a slight difference in the concentration of cations and anions between the two fluid compartments. [citation needed]

Transcellular fluid

[edit]Transcellular fluid is formed from the transport activities of cells, and is the smallest component of extracellular fluid. These fluids are contained within epithelial lined spaces. Examples of this fluid are cerebrospinal fluid, aqueous humor in the eye, serous fluid in the serous membranes lining body cavities, perilymph and endolymph in the inner ear, and joint fluid.[2][12] Due to the varying locations of transcellular fluid, the composition changes dramatically. Some of the electrolytes present in the transcellular fluid are sodium ions, chloride ions, and bicarbonate ions. [citation needed]

Function

[edit]

Extracellular fluid provides the medium for the exchange of substances between the ECF and the cells, and this can take place through dissolving, mixing and transporting in the fluid medium.[13] Substances in the ECF include dissolved gases, nutrients, and electrolytes, all needed to maintain life.[14] ECF also contains materials secreted from cells in soluble form, but which quickly coalesce into fibers (e.g. collagen, reticular, and elastic fibres) or precipitates out into a solid or semisolid form (e.g. proteoglycans which form the bulk of cartilage, and the components of bone). These and many other substances occur, especially in association with various proteoglycans, to form the extracellular matrix, or the "filler" substance, between the cells throughout the body.[15] These substances occur in the extracellular space, and are therefore all bathed or soaked in ECF, without being part of it. [citation needed]

Oxygenation

[edit]One of the main roles of extracellular fluid is to facilitate the exchange of molecular oxygen from blood to tissue cells and for carbon dioxide, CO2, produced in cell mitochondria, back to the blood. Since carbon dioxide is about 20 times more soluble in water than oxygen, it can relatively easily diffuse in the aqueous fluid between cells and blood.[16]

However, hydrophobic molecular oxygen has very poor water solubility and prefers hydrophobic lipid crystalline structures.[17][18] As a result of this, plasma lipoproteins can carry significantly more O2 than in the surrounding aqueous medium.[19][20]

If hemoglobin in erythrocytes is the main transporter of oxygen in the blood, plasma lipoproteins may be its only carrier in the ECF. [citation needed]

The oxygen-carrying capacity of lipoproteins, reduces in ageing and inflammation. This results in changes of ECF functions, reduction of tissue O2 supply and contributes to development of tissue hypoxia. These changes in lipoproteins are caused by oxidative or inflammatory damage.[21]

Regulation

[edit]The internal environment is stabilised in the process of homeostasis. Complex homeostatic mechanisms operate to regulate and keep the composition of the ECF stable. Individual cells can also regulate their internal composition by various mechanisms.[22]

There is a significant difference between the concentrations of sodium and potassium ions inside and outside the cell. The concentration of sodium ions is considerably higher in the extracellular fluid than in the intracellular fluid.[23] The converse is true of the potassium ion concentrations inside and outside the cell. These differences cause all cell membranes to be electrically charged, with the positive charge on the outside of the cells and the negative charge on the inside. In a resting neuron (not conducting an impulse) the membrane potential is known as the resting potential, and between the two sides of the membrane is about −70 mV.[24]

This potential is created by sodium–potassium pumps in the cell membrane, which pump sodium ions out of the cell, into the ECF, in return for potassium ions which enter the cell from the ECF. The maintenance of this difference in the concentration of ions between the inside of the cell and the outside, is critical to keep normal cell volumes stable, and also to enable some cells to generate action potentials.[25]

In several cell types voltage-gated ion channels in the cell membrane can be temporarily opened under specific circumstances for a few microseconds at a time. This allows a brief inflow of sodium ions into the cell (driven in by the sodium ion concentration gradient that exists between the outside and inside of the cell). This causes the cell membrane to temporarily depolarize (lose its electrical charge) forming the basis of action potentials. [citation needed]

The sodium ions in the ECF also play an important role in the movement of water from one body compartment to the other. When tears are secreted, or saliva is formed, sodium ions are pumped from the ECF into the ducts in which these fluids are formed and collected. The water content of these solutions results from the fact that water follows the sodium ions (and accompanying anions) osmotically.[26][27] The same principle applies to the formation of many other body fluids. [citation needed]

Calcium ions have a great propensity to bind to proteins.[28] This changes the distribution of electrical charges on the protein, with the consequence that the 3D (or tertiary) structure of the protein is altered.[29][30] The normal shape, and therefore function of very many of the extracellular proteins, as well as the extracellular portions of the cell membrane proteins, is dependent on a very precise ionized calcium concentration in the ECF. The proteins that are particularly sensitive to changes in the ECF ionized calcium concentration are several of the clotting factors in the blood plasma, which are functionless in the absence of calcium ions, but become fully functional on the addition of the correct concentration of calcium salts.[23][28] The voltage gated sodium ion channels in the cell membranes of nerves and muscle have an even greater sensitivity to changes in the ECF ionized calcium concentration.[31] Relatively small decreases in the plasma ionized calcium levels (hypocalcemia) cause these channels to leak sodium into the nerve cells or axons, making them hyper-excitable, thus causing spontaneous muscle spasms (tetany) and paraesthesia (the sensation of "pins and needles") of the extremities and round the mouth.[29][31][32] When the plasma ionized calcium rises above normal (hypercalcemia) more calcium is bound to these sodium channels having the opposite effect, causing lethargy, muscle weakness, anorexia, constipation and labile emotions.[32][33]

The tertiary structure of proteins is also affected by the pH of the bathing solution. In addition, the pH of the ECF affects the proportion of the total amount of calcium in the plasma which occurs in the free, or ionized form, as opposed to the fraction that is bound to protein and phosphate ions. A change in the pH of the ECF therefore alters the ionized calcium concentration of the ECF. Since the pH of the ECF is directly dependent on the partial pressure of carbon dioxide in the ECF, hyperventilation, which lowers the partial pressure of carbon dioxide in the ECF, produces symptoms that are almost indistinguishable from low plasma ionized calcium concentrations.[29]

The extracellular fluid is constantly "stirred" by the circulatory system, which ensures that the watery environment which bathes the body's cells is virtually identical throughout the body. This means that nutrients can be secreted into the ECF in one place (e.g. the gut, liver, or fat cells) and will, within about a minute, be evenly distributed throughout the body. Hormones are similarly rapidly and evenly spread to every cell in the body, regardless of where they are secreted into the blood. Oxygen taken up by the lungs from the alveolar air is also evenly distributed at the correct partial pressure to all the cells of the body. Waste products are also uniformly spread to the whole of the ECF, and are removed from this general circulation at specific points (or organs), once again ensuring that there is generally no localized accumulation of unwanted compounds or excesses of otherwise essential substances (e.g. sodium ions, or any of the other constituents of the ECF). The only significant exception to this general principle is the plasma in the veins, where the concentrations of dissolved substances in individual veins differ, to varying degrees, from those in the rest of the ECF. However, this plasma is confined within the waterproof walls of the venous tubes, and therefore does not affect the interstitial fluid in which the body's cells live. When the blood from all the veins in the body mixes in the heart and lungs, the differing compositions cancel out (e.g. acidic blood from active muscles is neutralized by the alkaline blood homeostatically produced by the kidneys). From the left atrium onward, to every organ in the body, the normal, homeostatically regulated values of all of the ECF's components are therefore restored. [citation needed]

Interaction between the blood plasma, interstitial fluid and lymph

[edit]

The arterial blood plasma, interstitial fluid and lymph interact at the level of the blood capillaries. The capillaries are permeable and water can move freely in and out. At the arteriolar end of the capillary the blood pressure is greater than the hydrostatic pressure in the tissues.[34][23] Water will therefore seep out of the capillary into the interstitial fluid. The pores through which this water moves are large enough to allow all the smaller molecules (up to the size of small proteins such as insulin) to move freely through the capillary wall as well. This means that their concentrations across the capillary wall equalize, and therefore have no osmotic effect (because the osmotic pressure caused by these small molecules and ions – called the crystalloid osmotic pressure to distinguish it from the osmotic effect of the larger molecules that cannot move across the capillary membrane – is the same on both sides of capillary wall).[34][23]

The movement of water out of the capillary at the arteriolar end causes the concentration of the substances that cannot cross the capillary wall to increase as the blood moves to the venular end of the capillary. The most important substances that are confined to the capillary tube are plasma albumin, the plasma globulins and fibrinogen. They, and particularly the plasma albumin, because of its molecular abundance in the plasma, are responsible for the so-called "oncotic" or "colloid" osmotic pressure which draws water back into the capillary, especially at the venular end.[34]

The net effect of all of these processes is that water moves out of and back into the capillary, while the crystalloid substances in the capillary and interstitial fluids equilibrate. Since the capillary fluid is constantly and rapidly renewed by the flow of the blood, its composition dominates the equilibrium concentration that is achieved in the capillary bed. This ensures that the watery environment of the body's cells is always close to their ideal environment (set by the body's homeostats). [citation needed]

A small proportion of the solution that leaks out of the capillaries is not drawn back into the capillary by the colloid osmotic forces. This amounts to between 2–4 liters per day for the body as a whole. This water is collected by the lymphatic system and is ultimately discharged into the left subclavian vein, where it mixes with the venous blood coming from the left arm, on its way to the heart.[23] The lymph flows through lymph capillaries to lymph nodes where bacteria and tissue debris are removed from the lymph, while various types of white blood cells (mainly lymphocytes) are added to the fluid. In addition the lymph which drains the small intestine contains fat droplets called chylomicrons after the ingestion of a fatty meal.[28] This lymph is called chyle which has a milky appearance, and imparts the name lacteals (referring to the milky appearance of their contents) to the lymph vessels of the small intestine.[35]

Extracellular fluid may be mechanically guided in this circulation by the vesicles between other structures. Collectively this forms the interstitium, which may be considered a newly identified biological structure in the body.[36] However, there is some debate over whether the interstitium is an organ.[37]

Electrolytic constituents

[edit]- Chloride (Cl−) 103–112 mM

- Bicarbonate (HCO3−) 22–28 mM

- Phosphate (HPO42−) 0.8–1.4 mM

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Chumlea, W. Cameron; Guo, Shumei S.; Zeller, Christine M.; Reo, Nicholas V.; Siervogel, Roger M. (1999-07-01). "Total body water data for white adults 18 to 64 years of age: The Fels Longitudinal Study". Kidney International. 56 (1): 244–252. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00532.x. ISSN 0085-2538. PMID 10411699.

- ^ a b "Fluid Physiology: 2.1 Fluid Compartments". www.anaesthesiamcq.com. Retrieved 2019-11-28.

- ^ Tortora G (1987). Principles of anatomy and physiology (5th ed.). New York: Harper and Row. p. 693. ISBN 978-0-06-350729-6.

- ^ Hillis D (2012). Principles of life. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. p. 589. ISBN 978-1-4292-5721-3.

- ^ Pocock G, Richards CD (2006). Human physiology : the basis of medicine (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 548. ISBN 978-0-19-856878-0.

- ^ Canavan A, Arant BS (October 2009). "Diagnosis and management of dehydration in children" (PDF). American Family Physician. 80 (7): 692–696. PMID 19817339.

- ^ a b Hall J (2011). Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology (12th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier. pp. 286–287. ISBN 978-1-4160-4574-8.

- ^ Wiig, Helge; Swartz, Melody A. (2012). "Interstitial Fluid and Lymph Formation and Transport: Physiological Regulation and Roles in Inflammation and Cancer". Physiological Reviews. 92 (3). American Physiological Society: 1005–1060. doi:10.1152/physrev.00037.2011. ISSN 0031-9333. PMID 22811424. S2CID 11394172.

- ^ "Definition of interstitial fluid". www.cancer.gov. 2011-02-02. Retrieved 2022-03-08.

- ^ "Interstitial Fluid – What is the Role of Interstitial Fluid". Diabetes Community, Support, Education, Recipes & Resources. 2019-07-22. Retrieved 2019-07-22.

- ^ Widmaier, Eric P., Hershel Raff, Kevin T. Strang, and Arthur J. Vander. "Body Fluid Compartments." Vander's Human Physiology: The Mechanisms of Body Function. 14th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2016. 400–401. Print.

- ^ Constanzo LS (2014). Physiology (5th ed.). Elsevier Saunders. p. 264. ISBN 9781455708475.

- ^ Tortora G (1987). Principles of anatomy and physiology (5th ed. Harper international ed.). New York: Harper & Row. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-0-06-046669-5.

- ^ Tortora G (1987). Principles of anatomy and physiology (5th ed. Harper international ed.). New York: Harper & Row. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-06-046669-5.

- ^ Voet D, Voet J, Pratt C (2016). Fundamentals of Biochemistry: Life at the Molecular Level. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. p. 235. ISBN 978-1-118-91840-1.

- ^ Arthurs, G.J.; Sudhakar, M (December 2005). "Carbon dioxide transport". Continuing Education in Anaesthesia, Critical Care & Pain. 5 (6): 207–210. doi:10.1093/bjaceaccp/mki050.

- ^ Bačič, G.; Walczak, T.; Demsar, F.; Swartz, H. M. (October 1988). "Electron spin resonance imaging of tissues with lipid-rich areas". Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 8 (2): 209–219. doi:10.1002/mrm.1910080211. PMID 2850439. S2CID 41810978.

- ^ Windrem, David A.; Plachy, William Z. (August 1980). "The diffusion-solubility of oxygen in lipid bilayers". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 600 (3): 655–665. doi:10.1016/0005-2736(80)90469-1. PMID 6250601.

- ^ Petyaev, I. M.; Vuylsteke, A.; Bethune, D. W.; Hunt, J. V. (1998-01-01). "Plasma Oxygen during Cardiopulmonary Bypass: A Comparison of Blood Oxygen Levels with Oxygen Present in Plasma Lipid". Clinical Science. 94 (1): 35–41. doi:10.1042/cs0940035. ISSN 0143-5221. PMID 9505864.

- ^ Jackson, M. J. (1998-01-01). "Plasma Oxygen during Cardiopulmonary Bypass". Clinical Science. 94 (1): 1. doi:10.1042/cs0940001. ISSN 0143-5221. PMID 9505858.

- ^ Petyaev, Ivan M.; Hunt, James V. (April 1997). "Micellar acceleration of oxygen-dependent reactions and its potential use in the study of human low density lipoprotein". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Lipids and Lipid Metabolism. 1345 (3): 293–305. doi:10.1016/S0005-2760(97)00005-2. PMID 9150249.

- ^ Pocock G, Richards CD (2006). Human physiology : the basis of medicine (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-19-856878-0.

- ^ a b c d e Tortora G (1987). Principles of anatomy and physiology (5th ed.). New York: Harper & Row, International. pp. 40, 49–50, 61, 268–274, 449–453, 456, 494–496, 530–552, 693–700. ISBN 978-0-06-046669-5.

- ^ Tortora G (1987). Principles of Anatomy and Physiology. Harper & Row. p. 269. ISBN 978-0-06-046669-5.

- ^ Tortora G (2011). Principles of anatomy and physiology (13th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. pp. 73–74. ISBN 978-0-470-64608-3.

- ^ Tortora G, Anagnostakos N (1987). Principles of anatomy and physiology (5th ed.). New York: Harper and Row. pp. 34, 621, 693–694. ISBN 978-0-06-350729-6.

- ^ "Data". pcwww.liv.ac.uk.

- ^ a b c Stryer L (1995). Biochemistry (4th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman and Co. pp. 255–256, 347–348, 697–698. ISBN 0-7167-2009-4.

- ^ a b c Macefield G, Burke D (February 1991). "Paraesthesiae and tetany induced by voluntary hyperventilation. Increased excitability of human cutaneous and motor axons". Brain. 114 ( Pt 1B) (1): 527–540. doi:10.1093/brain/114.1.527. PMID 2004255.

- ^ Stryer L (1995). Biochemistry (4th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman and Co. pp. 347, 348. ISBN 978-0-7167-2009-6.

- ^ a b Armstrong CM, Cota G (March 1999). "Calcium block of Na+ channels and its effect on closing rate". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (7): 4154–4157. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.4154A. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.7.4154. PMC 22436. PMID 10097179.

- ^ a b Harrison TR. Principles of Internal Medicine (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company. pp. 170, 571–579.

- ^ Waters M (2009). "Hypercalcemia". InnovAiT. 2 (12): 698–701. doi:10.1093/innovait/inp143.

- ^ a b c Hall J (2011). Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology (12th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier. pp. 177–181. ISBN 978-1-4160-4574-8.

- ^ Williams PL, Warwick R, Dyson M, Bannister LH (1989). Gray's Anatomy (37th ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. p. 821. ISBN 0443-041776.

- ^ Rettner R (27 March 2018). "Meet Your Interstitium, a Newfound 'Organ'". Scientific American. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ "Is the Interstitium Really a New Organ?". The Scientist.

- ^ a b Diem K, Lentner C (1970). "Blood – Inorganic substances". in: Scientific Tables (7th ed.). Basle, Switzerland: Ciba-Geigy Ltd. pp. 561–568.

- ^ Guyton & Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology, p. 5.