Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Types of marriages

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2007) |

| Family law |

|---|

| Family |

The type, functions, and characteristics of marriage vary from culture to culture, and can change over time. In general there are two types: civil marriage and religious marriage, and typically marriages employ a combination of both (religious marriages must often be licensed and recognized by the state, and conversely civil marriages, while not sanctioned under religious law, are nevertheless respected). Marriages between people of differing religions are called interfaith marriages, while marital conversion, a more controversial concept than interfaith marriage, refers to the religious conversion of one partner to the other's religion for sake of satisfying a religious requirement.

Americas and Europe

[edit]In the Americas and Europe, in the 21st century, legally recognized marriages are formally presumed to be monogamous (although some pockets of society accept polygamy socially, if not legally, and some couples choose to enter into open marriages). In these countries, divorce is relatively simple and socially accepted. In the West, the prevailing view toward marriage today is that it is based on a legal covenant recognizing emotional attachment between the partners and entered into voluntarily.

In the West, marriage has evolved from a life-time covenant that can only be broken by fault or death to a contract that can be broken by either party at will. Other shifts in Western marriage since World War I include:

- There emerged a preference for maternal custody of children after divorce, as custody was more often settled based on the best interests of the child, rather than strictly awarding custody to the parent of greater financial means.

- Both spouses have a formal duty of spousal support in the event of divorce (no longer just the husband)[clarification needed]

- Out of wedlock children have the same rights of support as legitimate children

- In most countries, rape within marriage is illegal and can be punished

- Spouses may no longer physically abuse their partners and women retain their legal rights upon marriage.

- In some jurisdictions, property acquired since marriage is not owned by the title-holder. This property is considered marital and to be divided among the spouses by community property law or equitable distribution via the courts.

- Marriages are more likely to be a product of mutual love, rather than economic necessity or a formal arrangement among families.

- Remaining single by choice is increasingly viewed as socially acceptable and there is less pressure on young couples to marry. Marriage is no longer obligatory.

- Interracial marriage is no longer forbidden. Same-sex marriage and civil unions are legal in some countries.

Outside the West, same-race marriage was illegal in Paraguay before becoming legal.

Asia and Africa

[edit]

Key facts concerning the marriage law in Africa and Asia:

- Marital rape is legal in most parts of Africa and Asia alike.

- Child marriage is legal in most parts of Africa and very few parts of Asia.

- Arranged marriage is prevalent in many parts of Africa and Asia alike, especially in rural regions.

- Same-sex marriage is illegal in most parts of Africa and Asia alike, with the exception of South Africa, Taiwan and some dependent territories.

- Polygamy is legal in many parts of Africa and Asia, but tends to be illegal in most communist countries and legal in most Muslim countries.

- Divorce is legal in all parts of Africa and Asia (except in the Philippines), but wives seeking divorce have fewer legal rights than husbands in Muslim countries than in communist countries.[clarification needed] [1]

- Dowries are a traditional aspect of marriage customs in most rural regions of Africa and Asia alike.

Some societies permit polygamy, in which a man could have multiple wives; even in such societies however, most men have only one. In such societies, having multiple wives is generally considered a sign of wealth and power. The status of multiple wives has varied from one society to another.

In Imperial China, formal marriage was sanctioned only between a man and a woman, although among the upper classes, the primary wife was an arranged marriage with an elaborate formal ceremony while concubines could be taken on later with minimal ceremony. Since the rise of communism, only strictly monogamous marital relationships are permitted, although divorce is a relatively simple process.

Monogamy, polyandry, and polygyny

[edit]Polyandry (a woman having multiple husbands) occurs very rarely in a few isolated tribal societies. These societies include some bands of the Canadian Inuit,[citation needed] although the practice has declined sharply in the 20th century due to their conversion from tribal religion to Christianity by Moravian missionaries. Additionally, the Spartans were notable for practicing polyandry.[2]

Societies which permit group marriage are extremely rare, but have existed in Utopian societies such as the Oneida Community.[citation needed]

Today, many married people practice various forms of consensual nonmonogamy, including polyamory and swinging. These people have agreements with their spouses that permit other intimate relationships or sexual partners. Therefore, the concept of marriage need not necessarily hinge on sexual or emotional monogamy.

Christian acceptance of monogamy

[edit]In the Christian society, a "one man one woman" model for the Christian marriage was advocated by Saint Augustine (354–439 AD) with his published letter The Good of Marriage. To discourage polygamy, he wrote it "was lawful among the ancient fathers: whether it be lawful now also, I would not hastily pronounce. For there is not now necessity of begetting children, as there then was, when, even when wives bear children, it was allowed, in order to a more numerous posterity, to marry other wives in addition, which now is certainly not lawful." (chapter 15, paragraph 17) Sermons from St. Augustine's letters were popular and influential. In 534 AD Roman Emperor Justinian criminalized all but monogamous man-woman sex within the confines of marriage. The Codex Justinianus was the basis of European law for 1,000 years.

Several examples of other types of relationships are exhibited in the Bible amongst various Biblical figures, incestuous relationships such as Abraham and Sarah,[3] Nachor and Melcha,[4] Lot and his Daughters,[5] Amram and Jochabed[6] and more.[7][8][9]

Contemporary Western societies

[edit]In 21st century Western societies, bigamy is illegal and sexual relations outside of a marriage are generally frowned-upon, though there is a minority view accepting (or even advocating) open marriage.

However, divorce and remarriage are relatively easy to undertake in these societies. This has led to a practice called serial monogamy, which involves entering into successive marriages over time. Serial monogamy is also sometimes used to refer to cases where the couples cohabitate without getting married.

Unique practices

[edit]Some parts of India follow a custom in which the groom is required to marry with an auspicious plant called Tulsi before a second marriage to overcome inauspicious predictions about the health of the husband. This also applies if the prospective wife is considered to be 'bad luck' or a 'bad omen' astrologically. However, the relationship is not consummated and does not affect partners' ability to remarry later.[10]

In the state of Kerala, India, the Nambudiri Brahmin caste traditionally practiced henogamy, in which only the eldest son in each family was permitted to marry. The younger children could have sambandha (temporary relationship) with Kshatriya or Nair women. This is no longer practiced, and in general the Nambudiri Brahmin men marry only from the Nambudiri caste and Nair women prefer to be married to Nair men. Tibetan fraternal polyandry (see Polyandry in Tibet) follows a similar pattern, in which multiple sons in a family all marry the same wife, so the family property is preserved; leftover daughters either become celibate Buddhist nuns or independent households. It was formerly practiced in Tibet and nearby Himalayan areas, and while it was discouraged by the Chinese after their conquest of the region, it is becoming more common again.[11] In Mormonism, a couple may seal their marriage "for time and for all eternity" through a "sealing" ceremony conducted within an LDS Temple. The couple is then believed to be bound to each other in marriage throughout eternity if they live according to their covenants made in the ceremony. Mormonism also allows living persons to act as proxies in the sealing ceremony to "seal" a marriage between ancestors who have been dead for at least one year and who were married during their lifetime. According to LDS theology, it is then up to the deceased individuals to accept or reject this sealing in the spirit world before their eventual resurrection. A living person can also be sealed to his or her deceased spouse, with another person (of the same sex as the deceased) acting as proxy for that deceased individual.[citation needed]

One society traditionally did without marriage entirely - the Na of Yunnan province in southern China. According to anthropologist Cia Hua, sexual liaisons among the Na took place in the form of "visits" initiated by either men or women, each of whom might have two or three partners each at any given time (and as many as two hundred throughout a lifetime). The nonexistence of fathers in the Na family unit was consistent with Na practices of matrilineality and matrilocality, in which siblings and their offspring lived with their maternal relatives. In recent years the Chinese state has encouraged the Na to acculturate to the monogamous marriage norms of greater China. Such programs have included land grants to monogamous Na families, conscription (in the 1970s, couples were rounded up in villages ten or twenty at a time and issued marriage licenses), legislation declaring frequent sexual partners married and outlawing "visits", and the withholding of food rations from children who could not identify their fathers.[citation needed] Many of these measures were relaxed in favor of educational approaches after Deng Xiaoping came to power in 1981. See also the Mosuo ethnic minority of China and their practice of walking marriage.

Fairytale marriages

[edit]Popular wisdom and standard social attitudes as transmitted in folk tales may show a matter-of-fact acceptance of universality of marriage in a variety of manifestations. Folk-tales can feature marriage (labelled as such) between species,[12] including humans[13] - compare versions of the tale of the Frog Prince.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Buckley, Anisa (2020-03-06). "What are Muslim women's options in religious divorce?". ABC Religion & Ethics. Retrieved 2021-06-04.

- ^ Pomeroy, Sarah B.: Spartan Women, page 46. Oxford University Press";

- ^ "BibleGateway, Genesis 20,20:11-12";

- ^ "Genesis 11:26-29; NIV – After Terah had lived 70 years, he". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 2013-05-27.

- ^ "Genesis 19:31-36; NIV – One day the older daughter said to the". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 2013-05-27.

- ^ "Exodus 6:19-20; NIV – The sons of Merari were Mahli and". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 2013-05-27.

- ^ "II Kings 13:1-2; NIV – Jehoahaz King of Israel – In the". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 2013-05-27.

- ^ "II Kings 13:8-12; NIV – As for the other events of the reign of". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 2013-05-27.

- ^ "II Kings 13:14; NIV – Now Elisha had been suffering from the". Bible Gateway. Retrieved 2013-05-27.

- ^ "Tulsi Vivah 2019: Date, Puja Vidhi, Mahurat, Vrat Katha and all you need to know - Times of India". The Times of India. 8 November 2019. Retrieved 2021-06-04.

- ^ Sidner, Sara (24 October 2008). "Brothers share wife to secure family land". CNN. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ For example: Cat and Mouse in Partnership Grimm, Jacob; Grimm, Willhelm, eds. (1880) [1812]. "The Cat who Married a Mouse". Grimms' Fairy Tales: A New Translation. The prize library. Translated by Paull, H. B. London: Frederick Warne and Company. p. 13-16. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^

Ashliman, D. L. (2004). Folk and Fairy Tales: A Handbook. Greenwood folklore handbooks, ISSN 1549-733X. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 46. ISBN 9780313328107. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

Extremely common are marriage arrangements (usually brokered through the heroine's father) between a princess and a seemingly undesirable partner. Animal-bridegroom tales fall into this category, in addition to many others where a beautiful woman is promised to an obnoxious suitor [...].

External links

[edit]Types of marriages

View on GrokipediaStructural Classifications

Monogamy

Monogamy constitutes a marital structure wherein an individual is united with a single spouse at any given time, precluding concurrent unions with multiple partners. This form encompasses both lifelong pairings and serial arrangements, where sequential exclusive marriages occur following dissolution of prior ones via divorce or death. Anthropologically, monogamy aligns with pair-bonding that facilitates biparental care and resource allocation to offspring, distinguishing it from plural forms by limiting spousal multiplicity.[6][7] Empirical cross-cultural data reveal monogamy as the predominant marital practice globally, even in societies where polygyny receives legal or customary sanction in approximately 85 percent of documented cases. Within such groups, monogamous unions outnumber plural ones due to factors including near-equal adult sex ratios, which constrain widespread polygyny by leaving many males unpaired, and socioeconomic pressures favoring equitable partner distribution to mitigate intrasexual competition and enhance societal stability. Genetic evidence supports this pattern, with human extra-pair paternity rates averaging around 2 percent—comparable to socially monogamous primates—indicating fidelity in observed pairings despite underlying mating incentives for polygyny.[6][7][8][9] In contemporary industrialized contexts, serial monogamy has emerged as the modal variant, characterized by repeated exclusive partnerships rather than singular lifelong bonds. Studies of reproductive outcomes demonstrate that men derive greater fitness benefits from serial strategies, achieving higher variance in spouse and offspring counts compared to women, who exhibit more stable pair retention. This shift correlates with elevated divorce rates and delayed remarriage, yet maintains monogamous exclusivity within each union, reflecting adaptive responses to modern longevity and mobility absent in ancestral environments.[10][11]Polygyny

Polygyny refers to a marital structure in which a single male is simultaneously married to two or more females, distinct from polyandry or group marriages.[12] This form contrasts with monogamy by allowing resource pooling and division of reproductive labor among co-wives, often rooted in agrarian economies where male labor and multiple offspring enhance family productivity.[13] Globally, polygyny remains rare, affecting approximately 2% of the world's population, with the vast majority of cases confined to sub-Saharan Africa and pockets of the Middle East. In West African nations such as Burkina Faso, prevalence reaches 36-45% among certain religious groups, including 40% of Muslims, while in countries like South Africa it stands at only 2%. Rates have declined over decades due to urbanization, education, and legal reforms, dropping from over 60% in some Sahelian countries in the 1970s to under 30% in many today. In Islamic contexts, where it is doctrinally permitted up to four wives under conditions of equitable treatment, actual practice varies: Nigeria reports 40% of Muslim women in polygynous unions, compared to lower figures in Asia like Indonesia at under 3%.[14][13][15] Historically, polygyny has appeared in diverse civilizations, including ancient Mesopotamia, Hebrew societies, and imperial China, often tied to status and inheritance preservation rather than universal norm. In pre-colonial Africa, it facilitated lineage continuity and labor distribution in patrilineal systems, with prevalence exceeding 70% in some Nigerian communities mid-20th century. Modern persistence correlates with low female education and economic dependence, though demographic analyses indicate it does not systematically exclude young men from marriage as popularly assumed, due to age gaps and serial monogamy patterns.[16][17][18] Legally, polygyny is recognized in 58 sovereign states, predominantly Muslim-majority nations in Africa and Asia, where it applies mainly to men under religious or customary law; polyandry remains illegal everywhere. In contrast, it is criminalized as bigamy in Western countries, including the United States, Canada, and Europe, with rare prosecutions but firm prohibitions. Enforcement varies: in Nigeria, it operates via Sharia in northern states, while South Africa's 1998 Recognition of Customary Marriages Act permits it under strict registration.[19][20] Empirical studies consistently document adverse effects on women and children in polygynous households. Systematic reviews of mental health data from polygynous wives reveal elevated rates of depression (up to 2-3 times higher), anxiety, somatization, and lower life satisfaction compared to monogamous counterparts, attributed to resource competition, jealousy, and reduced spousal attention. Children fare worse psychologically, with meta-analyses showing increased risks of emotional distress, behavioral issues, and lower academic achievement, linked to diluted parental investment and family instability. Societally, polygyny correlates with higher acceptance of intimate partner violence among women in sub-Saharan Africa, potentially exacerbating gender inequalities, though some qualitative accounts from practitioners highlight benefits like shared childcare in resource-scarce settings. These findings derive from large-scale surveys like Demographic and Health Surveys, underscoring causal pathways from co-wife rivalry to psychosocial strain, though selection biases in self-reporting warrant caution.[21][22][23]Polyandry

Polyandry refers to a form of plural marriage in which a woman is simultaneously wed to two or more husbands, typically co-residing and sharing resources.[24] This practice contrasts with the more common polygyny and is documented in fewer than 1% of human societies, with approximately 53 cases identified across ethnographic records.[25] The predominant variant is fraternal polyandry, where a woman marries brothers, ensuring shared paternity ambiguity and undivided family estates; non-fraternal forms, involving unrelated men, are exceedingly rare.[26] In Tibetan society, this custom historically prevailed among agriculturalists in resource-scarce high-altitude regions, with estimates indicating up to 90% of families in certain western Tibetan villages practicing it as late as the mid-20th century to preserve land holdings amid male-biased sex ratios and arable limitations.[27] Similar patterns occur among Nyinba communities in Nepal's Humla district, where fraternal unions mitigate fragmentation of small land plots in harsh Himalayan environments, sustaining household viability through pooled male labor. Functional explanations emphasize ecological and economic pressures over purely cultural norms: in marginal agrarian settings with low productivity, polyandry limits population growth—evidenced by fertility rates 20-30% below regional monogamous averages—and averts inheritance dilution among heirs, as brothers collectively invest in offspring without subdividing scarce farmland.[28] Paternity is treated collectively, with children ascribed to the eldest brother for inheritance purposes, reducing intra-family conflict. Anthropological surveys link its persistence to skewed sex ratios from historical female infanticide or migration, though sociobiological models suggest inclusive fitness benefits for cooperating kin.[26] In contemporary contexts, polyandry has sharply declined due to socioeconomic modernization, state interventions, and legal prohibitions on plural unions. In Tibet under Chinese administration, official monogamy policies since the 1950s, coupled with urbanization and tourism-driven wealth diversification, reduced its incidence to under 5% by the 2000s.[29] Nepal's 1963 legal reforms criminalized polygamy, including polyandry, confining it to remote, customary pockets among ethnic groups like the Sherpa, though enforcement remains lax in isolated areas. Globally, no sovereign state grants formal legal recognition to polyandrous marriages, with statutes in most jurisdictions—such as India's Hindu Marriage Act of 1955—explicitly mandating monogamy and voiding plural contracts, rendering polyandry de facto informal or illicit.[19] Isolated non-fraternal instances persist among some Indigenous groups, like the Mosuo in China or certain Amazonian tribes, but lack institutional support and face assimilation pressures.[25]Group and Other Plural Forms

Group marriage, also known as polygynandry, involves the simultaneous union of multiple men and multiple women within a single familial or social structure, where participants are collectively bound rather than in hierarchical or paired arrangements.[30] This form contrasts with polygyny (one man with multiple wives) and polyandry (one woman with multiple husbands) by lacking a central figure of dominance, instead emphasizing multilateral commitments among all members.[31] Anthropological records indicate group marriage is exceptionally rare as an institutionalized practice, with no widespread prevalence in traditional societies, though theoretical models have debated its existence based on broader definitions of kinship and alliance formation.[32] [30] The most documented historical instance occurred in the Oneida Community, a utopian religious society founded in 1848 by John Humphrey Noyes in upstate New York, which practiced "complex marriage" until its dissolution in 1881.[33] In this system, approximately 300 members adhered to a doctrine where every man was considered married to every woman, with sexual relations regulated through communal oversight, male continence, and selective breeding practices known as stirpiculture to optimize offspring quality.[34] [33] The community enforced exclusivity within the group via mechanisms like mutual criticism sessions, but external pressures, including legal threats against polygamy and internal generational shifts favoring monogamy, led to its reorganization into traditional pairings by 1881.[35] This experiment, rooted in Christian perfectionism, demonstrated logistical challenges such as jealousy management and resource allocation, ultimately highlighting the instability of scaling group bonds beyond small units.[34] Other purported anthropological examples remain sparse and contested, often conflated with temporary alliances or extended kin networks rather than formalized marriages; for instance, some ethnographic accounts from early 20th-century studies suggested vestiges among certain indigenous groups, but these lack verification as enduring institutions.[32] In contemporary contexts, variants like polyfidelity—closed, exclusive multipartner relationships—emerge in non-traditional settings, but these typically evade legal marriage status and prioritize emotional fidelity over societal recognition, differing from historical group marriages by their voluntary, non-religious framing.[36] Empirical data from cross-cultural surveys underscore that plural forms beyond dyadic monogamy or unilateral polygamy constitute less than 1% of global marital arrangements, with group structures failing to sustain due to coordination costs and conflict over reproduction and inheritance.[37]Selection and Formation Processes

Arranged Marriages

Arranged marriages are unions in which spouses are selected primarily by third parties, such as parents, extended family members, or matchmakers, rather than through individual romantic choice. This process prioritizes factors like familial compatibility, socioeconomic status, religious affiliation, and cultural alignment over initial personal attraction between the couple. While consent from the prospective spouses is generally expected in non-coercive forms, the degree of individual veto power varies, distinguishing arranged marriages from forced marriages where agreement is absent or obtained under duress.[38][39] Such marriages remain prevalent in collectivist societies, particularly in South Asia, the Middle East, and parts of Africa, where they account for a significant portion of unions despite global declines driven by urbanization and rising individualism. In India, arranged marriages form the cultural norm with deep historical roots, often involving caste endogamy and astrological matching to ensure long-term harmony. Practices in the Middle East similarly emphasize guardian (wali) involvement under Islamic guidelines, focusing on tribal or familial ties, while variations in sub-Saharan Africa incorporate clan negotiations for economic or alliance benefits. Empirical observations indicate a shift away from fully traditional arrangements, with rates decreasing as education levels and female workforce participation increase.[40][41][42] Arranged marriages encompass several variants, categorized broadly as traditional, semi-arranged, and modern or "love-arranged." Traditional forms involve minimal prior interaction between spouses, with selections based solely on familial assessments of suitability. Semi-arranged unions allow brief courtship periods post-selection for compatibility checks, while modern iterations resemble facilitated introductions—families propose candidates via networks or matrimonial services, after which couples date and decide independently, blending parental guidance with personal agency. This evolution reflects adaptations to contemporary values, yet retains emphasis on vetted backgrounds to mitigate risks of mismatched partnerships.[39][43] Research on marital outcomes reveals that arranged marriages frequently demonstrate lower divorce rates than self-selected unions within comparable cultural settings, with estimates as low as 4% dissolution compared to 40% or higher in choice-based marriages. This stability is attributed to rigorous pre-marital screening for enduring traits like shared values and family support networks, which foster gradual affection and provide buffers against conflict, as opposed to passion-driven matches prone to disillusionment. Studies in arranged-dominant societies, such as those in South Asia and the Middle East, confirm that spousal choice type influences divorce probability, with familial involvement correlating to higher initial satisfaction over time despite slower romantic development. However, these findings must account for contextual factors like societal stigma against divorce, which may suppress separations independently of match quality.[44][45][46] Critiques from individualistic perspectives often highlight potential autonomy deficits, yet empirical data from originating regions underscore functional advantages in resource pooling and conflict resolution through kin mediation. In the United Arab Emirates, for example, divorced individuals from arranged marriages cited incompatibility but noted familial pressures as both stabilizing and constraining factors. Overall, success hinges on mutual consent and adaptive processes, with modern forms showing marital quality determinants akin to Western norms when individual input is integrated.[47][44]Love and Companionate Marriages

Love marriages involve partners selecting each other primarily based on mutual romantic affection, physical attraction, and personal compatibility, without significant involvement from families or external authorities.[48] This form contrasts with arranged unions by prioritizing individual autonomy in partner choice, often emerging from courtship or dating periods where emotional bonds form prior to commitment.[49] Empirical surveys in the United States indicate that 93% of married individuals and 84% of unmarried adults view love as a very important reason for marriage, underscoring its cultural centrality in individualistic societies.[50] Companionate marriages emphasize long-term friendship, emotional support, shared values, and egalitarian partnership over intense romantic passion or economic alliances, with spouses functioning as primary companions through life's stages.[51] This ideal, which integrates elements of love marriages but shifts focus toward stability and mutual reliance, traces its modern formulation to the early 20th century in the United States, where Judge Ben Lindsey advocated for "companionate" unions permitting legalized birth control, delayed childbearing until after education or financial readiness, and mutual-consent divorce for childless couples to test compatibility without lifelong obligations.[52] Lindsey's 1927 book The Companionate Marriage, co-authored with Wainwright Evans, framed this as an adaptive response to urbanization, women's increasing workforce participation, and declining fertility rates, aiming to reduce marital discord by allowing experimental phases before permanent ties.[53] Historically, companionate elements predate Lindsey's proposal, appearing in early modern Europe and North America as a shift from familial or economic marriages toward spousal affection and equality, influenced by Protestant emphases on personal compatibility and reduced parental control over unions.[54] By the mid-20th century, this model became normative in Western contexts, correlating with rising average marriage ages—reaching 28 for men and 26 for women in the U.S. by 2020—and lower fertility rates, as couples prioritized dual-career stability over early procreation.[55] Globally, love and companionate marriages predominate in Europe and North America, comprising nearly all unions, while arranged forms persist in over 50% of marriages in parts of South Asia and the Middle East, though hybrid "semi-arranged" variants incorporating personal choice are increasing even there.[56] Research on outcomes reveals mixed patterns: in societies favoring arranged marriages, self-selected love matches often begin with elevated passion and satisfaction but experience steeper declines over time due to unmet expectations or external family conflicts, whereas arranged unions may foster gradual affection through shared adaptation.[44] A 2012 U.S. study of both arranged and love-based marriages found comparable high levels of satisfaction, commitment, and both passionate and companionate love after several years, suggesting that initial partner selection method does not predetermine long-term quality when cultural support exists.[57] However, broader data links companionate ideals to higher divorce risks in low-fertility contexts, with U.S. rates stabilizing at around 40-50% for first marriages since the 1980s, attributed partly to emphasis on personal fulfillment over institutional permanence.[55] These findings, drawn from longitudinal surveys like those in the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, highlight causal factors such as economic independence and shifting gender roles in sustaining or straining such unions, rather than romantic origins alone.[58]Legal and Institutional Forms

Civil and State-Recognized Marriages

A civil marriage constitutes a legally binding contract between individuals, solemnized by a government official such as a registrar or judge, without religious elements, and regulated by state statutes to confer enforceable rights and obligations.[59] [60] State-recognized marriages encompass civil ceremonies as well as registered religious or customary unions that meet governmental criteria, ensuring uniform legal validity across jurisdictions.[61] [62] The institutionalization of civil marriage arose from Enlightenment-era secularization efforts to wrest family law from ecclesiastical control. In France, the Civil Code of 1804 under Napoleon Bonaparte established civil marriage as mandatory and prior to any religious rite, stipulating mutual consent, minimum ages of 15 for females and 18 for males, and public proclamation before witnesses to form the union.[63] This framework, emphasizing contractual equality under law while imposing duties like mutual fidelity and child support, spread via Napoleonic influence to Belgium, Italy, and parts of Latin America, prioritizing state oversight for demographic and inheritance stability.[64] By contrast, pre-revolutionary systems often subordinated civil effects to church validation, leading to disputes over legitimacy. Legal formation demands specific prerequisites to safeguard consent and capacity: voluntary agreement without duress, attainment of legal age (typically 18, with parental or judicial approval for minors in jurisdictions like certain U.S. states), proof of single status to preclude bigamy, and issuance of a marriage license followed by officiation with witnesses.[65] [66] Post-ceremony registration generates a certificate verifying the union, essential for international recognition, which requires compliance with both celebrant and domicile laws, often authenticated via apostille under the 1961 Hague Convention.[67] Non-compliance, such as omitting civil filing, renders religious ceremonies legally void in strict secular regimes like France or Mexico. State-recognized status activates a suite of civil protections, including automatic inheritance shares absent a will, spousal privilege in testimony, joint tax filing eligibility, and access to government benefits like Social Security survivor pensions in the U.S., totaling over 1,000 federal entitlements.[68] These derive from the marriage's contractual nature, enabling claims for alimony, equitable property division upon dissolution, and priority in medical decisions or immigration sponsorship.[69] In global practice, while civil forms predominate in secular states—overtaking religious ceremonies in England by the late 20th century—many nations validate diverse rites upon registry, though enforcement varies, with OECD countries reporting crude marriage rates below 2 per 1,000 population in 2020 for low-fertility contexts like Italy and Spain.[70] [71] This system underscores causal linkages between legal formalization and socioeconomic security, independent of spiritual sanction.Religious and Customary Marriages

Religious marriages are unions solemnized according to the rites and doctrines of a specific faith tradition, typically officiated by clergy or religious authorities, emphasizing spiritual covenants over purely secular contracts.[61] In Christianity, such marriages often constitute a sacrament, as in Catholic rites requiring vows before a priest and witnesses, rooted in biblical injunctions like Ephesians 5:31-32.[72] Islamic nikah involves a contract (aqd) with mahr payment and witnesses, permitting polygyny for men up to four wives under Quranic allowance (Surah An-Nisa 4:3), provided equitable treatment.[73] Hindu vivaha features saptapadi (seven steps around fire), symbolizing mutual vows, while Jewish kiddushin includes ketubah signing and chuppah canopy. Legal recognition of these varies globally; in the United States, religious ceremonies gain civil validity only if the officiant is state-authorized and licenses filed, absent which they confer no spousal rights like inheritance or tax benefits.[74] In contrast, countries like Israel recognize Jewish marriages automatically for Jews, though civil options are limited.[73] Customary marriages, prevalent in indigenous, tribal, or traditional societies, derive legitimacy from community norms and ancestral practices rather than codified religious texts or state laws, often involving rituals like bridewealth exchange or kinship negotiations to affirm alliances.[75] Anthropological studies define them as culturally sanctioned unions establishing economic and reproductive ties, frequently polygynous; for instance, in sub-Saharan Africa, practices such as lobola (cattle payment by groom's family) among Zulu or Maasai secure paternity certainty and resource flows.[76] In rural Pakistan, customary unions, including watta satta (exchange marriages), comprised 91.1% of marriages in Sindh province as of 2017 surveys, often bypassing formal registration and embedding caste endogamy.[77] These differ from religious forms by prioritizing communal consensus over divine ordinance, though overlaps occur, as in animist rituals blending with Islam in parts of West Africa. Legal status remains inconsistent; South Africa's 1998 Recognition of Customary Marriages Act grants polygynous customary unions equal footing with civil ones if registered, yet many persist informally, limiting women's property rights amid patrilineal inheritance norms.[73] While religious marriages invoke transcendent authority for moral binding—evident in lower divorce rates among observant adherents, such as 25-30% for U.S. evangelicals versus 50% national average—customary forms emphasize pragmatic kinship stability, with dissolution tied to restitution of bridewealth rather than courts.[61] Both contrast civil marriages by lacking inherent state enforcement unless hybridized, a pattern persisting where 70-80% of unions in low-income nations rely on such non-civil mechanisms per demographic data, reflecting adaptations to local enforcement capacities over universal legalism.[75]Common-Law and Informal Unions

Common-law marriage constitutes a legally binding union in select jurisdictions, established through continuous cohabitation, mutual intent to be spouses, and public representation as a married couple, without requiring a formal ceremony, license, or officiant.[78] This form originated under English common law principles but has been largely abolished or restricted globally, with recognition persisting primarily in a handful of U.S. states and the District of Columbia as of 2023.[79] Key requirements universally include both parties' legal capacity to marry (e.g., age and absence of prior undissolved marriages), agreement to form a marital relationship, and sufficient duration of cohabitation—often years—coupled with external acknowledgment as husband and wife.[80] In the United States, common-law marriage remains valid prospectively in Colorado, Iowa, Kansas, Montana, Rhode Island, Texas, and the District of Columbia, while a few states like Alabama and Pennsylvania recognize only those formed before specific cutoff dates (e.g., January 1, 2017, in Alabama).[81] Couples in these unions gain equivalent rights and obligations to ceremonially married pairs, including spousal inheritance, property division upon dissolution (requiring formal divorce proceedings), and eligibility for social security survivor benefits.[78] However, proving common-law status post-separation often demands substantial evidence, such as joint tax filings, shared insurance policies, or affidavits from witnesses, leading to frequent disputes in probate or divorce courts.[79] Outside the U.S., recognition is rare; for instance, some Canadian provinces like Ontario treat long-term cohabitants as common-law partners for limited purposes after three years, but without full marital equivalence.[82] Informal unions, by contrast, encompass cohabiting relationships lacking the intent or duration to qualify as common-law marriages, resulting in no automatic spousal status under most legal systems worldwide.[83] These arrangements, prevalent amid rising cohabitation rates—evident in over 20% of U.S. households by 2020 and similar trends in Europe—typically confer minimal statutory rights, such as no presumption of joint property ownership or spousal maintenance upon separation unless explicitly contracted via agreements.[84] In jurisdictions without common-law provisions, like the majority of U.S. states and England (where it ended in 1753), informal cohabitation ends informally without divorce, but may trigger equitable remedies for unjust enrichment in property claims.[85] Globally, legal responses remain patchwork; the European Union grants some cross-border mobility rights to stable de facto partners, yet lacks uniform property or inheritance protections, while in regions like the Middle East and North Africa, informal unions (e.g., unregistered misyar contracts) evade full regulatory oversight but risk vulnerability for women regarding maintenance and custody.[86][87] The distinction hinges on evidentiary intent: common-law elevates cohabitation to marital parity through deliberate spousal presentation, whereas informal unions reflect roommate-like or trial domesticity without legal presumption of permanence, often yielding inferior outcomes in asset division and dependency support.[88] Empirical data indicate informal unions dissolve at higher rates—up to twice that of marriages—partly due to absent institutional commitments, underscoring causal links between formal recognition and stability incentives.[89] In practice, parties in informal setups may draft cohabitation agreements to mimic marital protections, though enforceability varies and courts prioritize contractual clarity over implied duties.[90]Cultural and Regional Variations

Marriages in the Americas and Europe

In Europe and the Americas, marriage predominantly takes the form of legally recognized monogamous unions between two consenting adults, shaped by historical Christian monogamy mandates and modern secular legal frameworks that prohibit polygamy. Polygamy remains rare and illegal in these regions, with fewer than 2% of global households involving multiple spouses, and even lower prevalence here due to strict enforcement; for instance, spouselike polygamous relationships were criminalized in the United States by the late 19th century. Exceptions occur through limited recognition of foreign polygamous marriages among immigrant communities, such as an estimated 20,000 cases in the United Kingdom, primarily involving Muslim families where the original marriage was legal abroad.[14][91] Historically, Europe's Western marriage pattern emphasized late marriage in the mid-twenties, neolocal residence independent of extended families, and higher rates of lifelong celibacy, contrasting with earlier or more kin-integrated unions elsewhere; this pattern persisted through the medieval period under church influence promoting lifelong monogamy. In the Americas, pre-Columbian indigenous societies varied, with some patriarchal polygamous or monogamous sacred unions among elites, but European colonization imposed Christian monogamy, leading to blended customs in Latin America where informal consensual unions supplemented formal marriages. Early modern North American Puritan practices prioritized economic compatibility and religious piety over romance, with arranged elements to ensure mutual suitability rather than strict parental dictation.[92] Wait, no Wiki; skip specific, use general from [web:14] but it's wiki, avoid. Alternative: From [web:11] history US marriage colonial. Contemporary practices favor civil monogamous marriages, with religious ceremonies optional; in the European Union, 13 member states including Austria, Belgium, and Germany recognize same-sex marriage, while others offer civil unions with varying rights. Common-law or de facto unions, where cohabiting couples gain marital-like protections without formal ceremony, prevail in parts of North America—recognized in 10 U.S. states and fully in Canada—and increasingly in Latin America, where over 50% of unions in countries like Colombia and Uruguay are informal, reflecting economic and cultural tolerance for non-registered partnerships. Cohabitation rates have risen sharply, comprising over 30% of first unions in nations like Austria and the U.S., often transitioning to marriage less frequently than in prior decades, amid declining formal marriage rates to below 4 per 1,000 people in many countries.[93][94][95] Regional variations highlight cultural persistence: Northern Europe exhibits higher cohabitation and later formal marriage, with association-type partnerships emphasizing individual autonomy, while Southern Europe retains fusion models blending family alliance and emotional bonds. In the Americas, North American emphasis on companionate love-based unions contrasts with Latin America's higher acceptance of serial cohabitation and common-law forms, where crude divorce rates remain below 1 per 1,000 despite rising informal separations, influenced by Catholic heritage limiting formal dissolutions. These shifts correlate with broader trends of union instability, where cohabiting couples in Europe and the U.S. face 1.5-2 times higher dissolution risks than married ones, per longitudinal data.[92][96][94]Marriages in Asia and Africa

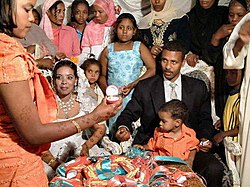

In South Asia, arranged marriages predominate, with over 90% of marriages in India following this pattern, where families negotiate unions based on social, economic, and caste compatibility rather than individual romantic choice.[97] Dowry payments from the bride's family to the groom's are customary in India, often escalating to significant sums that can burden families and correlate with higher rates of domestic violence when expectations are unmet.[98] In contrast, East Asian countries like China have shifted toward companionate marriages influenced by modernization, though bride prices paid by grooms to brides' families have risen sharply in rural areas, sometimes equaling years of income, as a form of wealth transfer amid sex ratio imbalances from selective abortions.[99] [100] Child marriages remain prevalent across parts of Asia, particularly South Asia, which accounts for 45% of the global total of women married before age 18, with rates exceeding 50% in countries like Bangladesh and India as of recent UNICEF estimates.[101] These unions often stem from economic pressures and cultural norms prioritizing early family alliances over individual development, leading to documented health risks including higher maternal mortality.[102] In sub-Saharan Africa, polygynous marriages—where men have multiple wives—are widespread, affecting 20-40% of married women in countries like Chad and prevalent at an average of 27.8% regionally, rooted in traditions of resource distribution and lineage expansion among pastoral and agrarian societies.[103] [104] Bride price, involving livestock, cash, or goods transferred from groom to bride's family, is practiced in 83% of ethnographic African societies, serving as compensation for reproductive labor and alliance-building but sometimes inflating marriage costs and delaying unions.[105] Customary marriages under tribal laws often coexist with statutory civil codes, with polygyny legally recognized in nations like Nigeria for Muslim populations, though empirical data links it to elevated intimate partner violence rates.[106] Child marriages in Africa, while lower in absolute numbers than Asia, persist at rates up to 76% in Niger, driven by poverty and patrilineal inheritance systems that view early marriage as securing paternity and economic ties.[101] These practices underscore causal links between marriage forms and socioeconomic structures, where empirical outcomes reveal trade-offs in fertility, stability, and gender dynamics absent in monogamous Western models.[102]Marriages in Oceania and the Middle East

In the Middle East, marriage is predominantly monogamous, though polygyny—where a man may have up to four wives—is permitted under Islamic Sharia law in countries such as Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Iraq, Yemen, Algeria, and Egypt.[14] [107] This practice derives from Quranic allowance provided the husband treats wives equitably, but empirical data indicate low prevalence, typically under 3% of households in surveyed nations, with rates of 2-9% across Arab countries overall.[107] [108] Higher rates, such as 20-36%, occur among specific subgroups like Bedouin Arabs, linked to cultural norms emphasizing male ego and economic capacity.[109] Arranged marriages, historically the norm for ensuring family alliances and social stability, have declined with urbanization and education, though they remain more common than individual-choice unions in rural and conservative areas.[110] [111] Child marriages, often arranged and justified by economic pressures or customary law, persist at elevated rates in parts of the region; UNICEF data report approximately 700,000 girls annually entering such unions in the Middle East and North Africa, with prevalence exceeding 20% for women aged 20-24 who married before 18 in countries like Yemen and Sudan.[112] [113] Legal minimum ages vary, often set at 18 but with exceptions for religious or parental consent, contributing to ongoing practices despite international pressure.[114] In Oceania, marriage types reflect a blend of colonial-influenced civil monogamy and indigenous customary systems, with the latter varying widely across Pacific Island societies and Aboriginal Australian groups. In Australia and New Zealand, state-recognized civil marriages predominate, requiring individuals to be at least 18 years old, though customary indigenous unions—such as Aboriginal kinship-based arrangements emphasizing moiety and section systems to prevent incest—hold cultural significance without automatic legal force.[115] [116] Traditional Aboriginal practices historically involved arranged betrothals, sometimes from infancy, and elopements or captures as alternatives, governed by strict eligibility rules tied to totemic affiliations.[115] Similarly, Māori marriages in New Zealand traditionally prioritized tribal alliances through family-arranged pairings or elopements, lacking formal ceremonies but requiring communal approval, with modern integrations including symbolic rituals like hongi greetings.[117] Pacific Island customary marriages often incorporate rituals such as bridewealth payments, symbolic exchanges like leis or kava ceremonies, and community feasts to affirm alliances, as seen in Fijian sevusevu offerings or Samoan ava presentations, though these coexist with legally mandated monogamous civil registrations at age 18.[118] [119] Polygyny and informal unions occur sporadically in customary contexts, particularly in Melanesia, but legal frameworks in nations like the Solomon Islands set the minimum age at 15 with consent, enabling some early customary marriages despite prohibitions on child unions under 15.[120] Harmful elements, including forced arrangements or polygamy tied to bride price, have been documented but are declining under legal reforms emphasizing consent and equality.Evolutionary and Biological Foundations

Origins and Adaptations of Marriage Forms

Marriage forms originated as adaptive strategies for human pair-bonding, rooted in evolutionary pressures favoring cooperative reproduction and offspring survival in environments with highly dependent young. Unlike most primates, humans exhibit extended pair bonds, likely emerging from ancestral patterns where concealed ovulation promoted ongoing affiliation between males and females to ensure paternal investment.[121] This transition is evidenced by phylogenetic reconstructions of hunter-gatherer societies, indicating that early modern human populations practiced predominantly low-polygyny monogamy, with arranged unions inferred to date back to migrations out of Africa around 60,000–70,000 years ago.[122] Anthropological data from foraging societies, representing the closest analogs to ancestral humans, reveal marriage as a socially recognized union formalizing mating, often with exogamous preferences to forge alliances and reduce inbreeding risks.[75] The universality of marriage across cultures underscores its deep evolutionary embedding, distinct from mere mating by incorporating reciprocal obligations for resource sharing and child-rearing, adaptations that mitigated the high costs of human infancy. Earliest archaeological traces, such as contract-like tablets from Mesopotamia circa 2350 BCE, document formalized monogamous unions with dowry exchanges, though these reflect institutionalized forms predating written records by millennia in oral traditions.[124] Adaptations in marriage forms arose in response to ecological and socioeconomic shifts, with monogamy persisting as the modal pattern despite variations. In pre-agricultural contexts, mild polygyny occurred where male resource variance allowed, but population-level monogamy predominated to balance sex ratios and paternity certainty.[122] The Neolithic transition to agriculture around 10,000 BCE enabled resource accumulation, fostering polygynous systems in stratified societies (e.g., elite males with multiple wives), yet cross-cultural surveys show ~80% of historical societies permitting polygyny while practicing mostly monogamous unions due to female choosiness and male competition constraints.[7][7] In modern industrial contexts, marriage has adapted toward serial monogamy and companionate ideals, aligning with reduced fertility needs and women's economic independence, though evolutionary legacies like jealousy and infidelity risks persist.[37] These shifts reflect causal pressures from urbanization and legal standardization, prioritizing bilateral nuclear units over extended kin networks, with empirical stability favoring monogamous pairs for long-term cooperation.[125] Overall, marriage forms demonstrate plasticity: from ancestral pair bonds ensuring biparental care to culturally modulated variants optimizing fitness in diverse niches.[126]Paternity Certainty and Resource Allocation

In human evolutionary biology, paternity certainty refers to the confidence a male has that a child is biologically his, which influences the allocation of resources such as time, protection, and provisioning to offspring.[127] Without reliable assurance of genetic relatedness, males risk investing in non-biological kin, reducing their inclusive fitness; thus, mechanisms like mate guarding and social monogamy evolved to mitigate this uncertainty by restricting female mating to one partner.[9] Empirical genetic studies in Western populations, where monogamous norms predominate, report non-paternity rates (instances of cuckoldry) typically below 1% over centuries, as evidenced by haplotype analysis of 1,273 conceptions spanning 335 years in a stable community, with rates not exceeding 0.94%.[128] A cross-temporal meta-analysis of 67 studies similarly estimates an average non-paternity rate of 3.1%, though recent data suggest declines to 1-2% under high-confidence monogamous pairings.[129] Monogamous marriage institutions enhance paternity certainty through cultural enforcement of fidelity, historically serving as a pre-DNA proxy for biological paternity and incentivizing male investment.[130] This certainty correlates with increased paternal care: men exhibiting higher perceived paternity confidence allocate more resources to putative biological children, including direct provisioning and protection, as cues of resemblance (e.g., facial or olfactory similarity) further reinforce investment decisions.[127] [131] In contrast, polygynous systems, prevalent in over 80% of human societies historically, introduce greater uncertainty for subordinate males sharing mates, often resulting in diluted per-offspring investment; dominant males may secure higher certainty via resource control and harem monopolization, but overall societal paternal effort per child diminishes due to competition and divided resources.[6] [132] Resource allocation patterns reflect these dynamics: in monogamous frameworks, assured paternity shifts male efforts from mate competition to biparental care, boosting child survival and economic productivity, as normative monogamy reduces polygynous variance in reproductive skew.[6] Experimental and observational data confirm that men prioritize investment in partners perceived as faithful, extending to current offspring over past ones absent strong paternity cues, underscoring how uncertainty prompts resource withholding to avoid exploitation.[133] Across marriage types, this principle holds: higher certainty fosters sustained provisioning, aligning with human adaptations for cooperative breeding where male contributions complement maternal investment, though polygyny's lower certainty per male often correlates with elevated female reproductive skew and reduced average child welfare.[134]Empirical Outcomes and Stability

Divorce Rates and Longevity by Type

Religious marriages demonstrate greater stability than secular or civil unions, with empirical data indicating lower divorce rates among couples who incorporate religious elements or maintain active faith practices. A longitudinal study from Harvard University's Human Flourishing Program found that regular religious service attendance correlates with approximately 50% lower divorce rates over a 14-year period, attributing this to enhanced commitment, social support networks, and normative pressures against dissolution.[135] Similarly, analysis from the Institute for Family Studies reveals that women raised in religious households experience annual divorce rates below those of nonreligious peers (around 5% for the latter), even accounting for earlier marriage ages common in religious communities.[136] These patterns hold across denominations, though variations exist; for instance, Protestant couples report lifetime divorce experiences around 39%, compared to higher rates among the religiously unaffiliated at 42%.[137] Arranged marriages, prevalent in certain cultural contexts such as South Asia, exhibit lower divorce rates than self-selected "love" marriages in comparable settings, often due to familial vetting, shared values, and lower initial romantic expectations that foster gradual compatibility. In an Indian sample from the Chitwan Valley, arranged unions showed sustained marital quality over time, while love matches began with higher satisfaction but declined faster, contributing to differential dissolution risks.[44] Global estimates suggest arranged marriage divorce rates as low as 4% in traditional societies, versus 40% or higher for choice-based unions in Western contexts, though these figures reflect both cultural stigma against divorce and structured support systems rather than inherent superiority.[138] However, exceptions occur; a district-level study in Pakistan's Multan region reported higher failure rates for arranged marriages, highlighting context-specific factors like mismatched family alliances.[46] Polygamous marriages, particularly polygynous forms, display reduced longevity and higher instability relative to monogamous ones, driven by resource competition, co-wife rivalry, and diluted paternal investment. Cross-cultural data from sub-Saharan Africa indicate that polygynous unions with multiple wives experience divorce rates up to five times those of monogamous families, with dissolution risks escalating in households with three or more wives.[31] In Nigerian samples, polygynous setups showed elevated separation rates compared to monogamous baselines, though some monogamous unions also faced high risks due to economic pressures.[139] These outcomes align with broader empirical patterns of intrahousehold conflict in non-monogamous structures, contrasting with the relative durability of formal monogamous marriages. Common-law or informal unions generally exhibit shorter durations and higher dissolution rates than formalized marriages, as cohabitation lacks the legal and social barriers to exit that promote perseverance. U.S. data from the National Center for Family & Marriage Research show that cohabiting relationships dissolve at rates exceeding those of marital unions, with premarital cohabitation linked to elevated post-marital divorce risks (up to 33% higher for those living together before wedding).[140] Median marriage duration in the U.S. stands at about 8 years for first unions ending in divorce, but lifelong monogamous marriages—often religious or culturally reinforced—extend far longer, with ongoing first marriages averaging over 20 years among intact couples.[141][142] Overall, marriage type influences longevity through causal mechanisms like commitment enforcement and external accountability, with empirical evidence favoring structured, monogamous forms for maximal stability.[143]Child Welfare and Societal Impacts

Children in stable, monogamous marriages between biological parents demonstrate superior outcomes in emotional adjustment, academic achievement, and behavioral health compared to those in non-intact or alternative family structures, with longitudinal data showing reduced risks of delinquency, depression, and substance abuse.[144][145] Polygamous family structures, particularly polygyny, correlate with elevated child mortality, poorer nutritional health, and higher rates of mental health disorders such as anxiety and depression, as evidenced by systematic reviews of quantitative studies across multiple societies.[146][147] Children in these households also exhibit increased social problems, lower academic performance, and greater vulnerability to bullying compared to peers in monogamous families.[21][148] Parental divorce and family instability from serial monogamy or cohabitation yield persistent negative effects on children, including heightened risks of educational underachievement, emotional maladjustment, and criminal involvement into adulthood, per national longitudinal surveys in the US and UK.[149][150] These outcomes stem from disrupted attachment, economic hardship, and inconsistent parenting, with effects most pronounced in children under five at the time of separation.[151] Regarding same-sex parented children, meta-analyses reveal mixed results, but those controlling for family stability and biological parentage indicate higher emotional and behavioral problems, particularly when children do not reside with the same-sex parent from infancy.[152] Many affirmative studies rely on small, non-representative samples of highly stable same-sex couples, potentially understating risks associated with higher relationship instability or donor conception in such unions.[153] On societal scales, prevalence of intact monogamous marriages correlates with lower violent crime rates and greater economic productivity, as unstable family structures contribute to intergenerational poverty and reduced social cohesion.[154][155] Polygamy's diffusion, by contrast, associates with broader health declines and resource competition, exacerbating inequality in resource allocation to offspring.[21][148]Controversies and Debates

Child and Early Marriages

Child marriage refers to any formal marriage or informal union in which at least one individual is under the age of 18, while early marriage typically encompasses unions occurring shortly after puberty but before full legal adulthood, often between ages 15 and 17.[156] [102] These practices disproportionately affect girls, though boys are also involved at lower rates, and are concentrated in regions with entrenched patriarchal norms and economic pressures.[101] Globally, approximately 640 million women and girls alive in 2023 were married before age 18, representing a prevalence of 19% among women aged 20-24, down from 23% a decade earlier.[101] [157] An estimated 12 million girls enter such unions annually, with nearly half residing in South Asia and the remainder primarily in sub-Saharan Africa.[158] Countries like Niger (76% prevalence) and Chad (67%) exhibit the highest rates, driven by factors including poverty, which prompts families to marry off daughters to reduce household burdens, and cultural beliefs associating early union with preserving female virginity and family honor.[159] [160] Empirical studies link child and early marriages to adverse health outcomes, including elevated risks of obstetric fistula, maternal mortality, and intimate partner violence due to immature physical development during early pregnancies.[161] Women married before 18 bear children at younger ages and in greater numbers, perpetuating cycles of poverty and limiting educational attainment, with married girls five times more likely to drop out of school than unmarried peers.[161] [162] Peer-reviewed analyses also indicate heightened mental health burdens, such as depression and anxiety, stemming from curtailed autonomy and exposure to coercive environments.[163] International frameworks, including the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Convention on Consent to Marriage, advocate for a minimum age of 18 without exceptions, emphasizing free and full consent as prerequisites for valid unions.[164] [165] Despite this, enforcement varies; over 100 countries permit marriage below 18 with parental or judicial approval, often rooted in religious or customary laws that prioritize community traditions over individual maturity.[166] Debates persist between universal human rights standards, which cite data on improved outcomes from delayed marriage, and cultural relativism arguments defending practices as adaptive in resource-scarce settings, though evidence consistently shows net harms to participants' long-term welfare without offsetting benefits.[161] [159] Historically, similar early unions occurred in medieval Europe, where canon law allowed girls to marry at 12, but reforms raised ages amid recognition of developmental risks, a pattern echoed in modern global trends toward prohibition.[165]Same-Sex Marriages

Same-sex marriage denotes the civil or legal recognition of unions between two individuals of the same biological sex, distinct from historical marital norms centered on opposite-sex complementarity for procreation and family formation. The contemporary push for legalization emerged in Western jurisdictions amid broader sexual revolution dynamics, with the Netherlands enacting the first nationwide law on April 1, 2001, following regional precedents like Denmark's 1989 registered partnerships.[167] Subsequent adoptions accelerated, including Canada's 2005 federal legislation, Argentina's 2010 pioneering move in Latin America, and the U.S. Supreme Court's 5-4 Obergefell v. Hodges decision on June 26, 2015, mandating nationwide validity despite prior state-level bans.[168] By October 2025, such unions are authorized in 38 countries, encompassing roughly 1.5 billion residents, predominantly in Europe, the Americas, and select Asia-Pacific nations like Taiwan (2019) and Thailand (effective January 23, 2025), though opposed or penalized in most African, Middle Eastern, and Asian states under religious or customary law.[169][168] Proponents frame legalization as an extension of equal protection principles, arguing exclusion discriminates without empirical detriment to society; the American Psychological Association's 2013 task force asserted no scientific warrant for denial, citing meta-analyses of small-scale studies showing equivalent or superior child adjustment in same-sex households.[170] Critics, however, contend this redefines marriage from a sex-dimorphic institution—rooted in biological realities of sexual reproduction and paternal investment—to a gender-neutral contract, eroding its signaling function for societal stability and potentially inviting further expansions like polygamy. Empirical data on union longevity reveals elevated dissolution risks: a 2019 Socius analysis of Dutch records found same-sex couples dissolving at rates 1.5 to 2 times higher than opposite-sex pairs over a decade, with lesbian unions exhibiting the steepest trajectories (e.g., 28% dissolution within five years of parenthood per longitudinal cohorts).[171] Swedish registry studies corroborate this, attributing disparities to factors like higher relational volatility among female same-sex pairs, independent of legalization effects.[172] These patterns persist post-legalization, challenging claims of parity; a 2023 MDPI review of Spanish dissolutions noted same-sex cases more often consensual but proportionally rarer due to shorter durations before breakdown.[173] Debates intensify over child welfare, where advocacy-driven reviews (e.g., Cornell's 2015 synthesis of 79 studies) assert no deficits in emotional, cognitive, or social outcomes relative to opposite-sex parents, often relying on non-representative, self-selected samples of stable, affluent families.[153] Counter-evidence from population-level data highlights risks: a 2012 analysis of U.S. surveys (though contested for methodology) linked same-sex parenting to doubled odds of child depression and unemployment, while critiques of the pro-consensus literature underscore systemic biases in academia, including suppression of dissenting findings like elevated gender dysphoria rates among offspring (up to 20-30% in some cohorts versus 1-2% general population).[174] A 2023 NIH review found same-sex parents reporting fewer child internalizing issues but equivocal externalizing behaviors, yet acknowledged selection effects inflating positives; causal realism suggests absent biological complementarity, children in such arrangements face inherent deficits in modeling sex-typical behaviors and securing dual parental investment, correlating with higher instability and mental health strains observed longitudinally.[175] These disparities, underexplored due to ideological pressures in peer-reviewed outlets, underscore ongoing contention over whether policy prioritizes adult autonomy over evidence-based family optima.[172]Polygamy Legalization and Slippery Slope Arguments

Slippery slope arguments regarding polygamy legalization posit that the redefinition of marriage to include same-sex unions, as affirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court in Obergefell v. Hodges on June 26, 2015, erodes traditional criteria limiting marriage to two opposite-sex partners, thereby inviting demands for multi-partner unions based on adult consent alone. Proponents of this view, including Justice Antonin Scalia in his Obergefell dissent, contended that excluding polygamy lacks principled distinction once marriage is decoupled from biological complementarity for reproduction, potentially extending to other non-traditional forms. These arguments draw on causal reasoning: shifting marriage's purpose from stable child-rearing units to emotional fulfillment undermines numerical limits, as evidenced by historical polygamous societies where resource allocation favored male dominance, yet modern advocates frame it as egalitarian polyamory.[176] Legal challenges to anti-polygamy laws intensified post-Obergefell, with plaintiffs invoking equal protection and due process to argue that bans on plural unions discriminate against consensual adult relationships, mirroring SSM rationales.[177] For instance, in 2015, a federal challenge in Utah tested bigamy statutes under Obergefell's framework, though courts upheld distinctions based on polygamy's administrative complexities in contracts, inheritance, and custody, rather than outright rejecting the slope.[177] Utah's Senate Bill 102, enacted May 12, 2020, decriminalized bigamy among consenting adults by reclassifying it as an infraction punishable by fines up to $750, while retaining felony status for coercion or minors, reflecting pragmatic tolerance without granting legal recognition to plural marriages.[178][179] This shift, supported unanimously in the state senate, addressed overreach in prior enforcement but did not endorse polygamy as a marital form, amid data showing persistent social costs like higher welfare dependency in polygamous communities.[180] Critics of the slippery slope, often from academic and progressive outlets, assert polygamy inherently involves unequal power dynamics and reduced relationship stability, citing empirical studies of polygynous groups where women report lower satisfaction and children face elevated risks of neglect due to divided paternal investment.[181] They argue distinctions persist because SSM aligns with dyadic equality, whereas polygamy complicates consent verification and state administration, as seen in failed multi-partner custody claims.[182] However, first-principles analysis reveals inconsistencies: if marriage law prioritizes autonomy over structure, numerical exclusions rely on unproven harms rather than logic, with recent Quebec rulings in spring 2025 recognizing multi-parent families signaling incremental erosion.[183] No jurisdiction has fully legalized polygamous marriage post-SSM, but decriminalization trends and philosophical extensions—like Fredrik deBoer's 2015 case for consent-based polyamory—indicate the argument's predictive traction, underscoring tensions between equality rhetoric and practical limits.[182][184]References

- https://www.[researchgate](/page/ResearchGate).net/publication/10977856_Marriage_an_evolutionary_perspective