Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ulster Irish

View on Wikipedia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2023) |

| Ulster Irish | |

|---|---|

| Donegal Irish • Ulster Gaelic | |

| Gaeilg Uladh | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈɡeːlʲəc ˌʊlˠuː] |

| Ethnicity | Irish Ulstermen |

Early forms | |

| Dialects |

|

| Latin (Irish alphabet) Irish Braille | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | done1238 |

The Gaeltachtaí | |

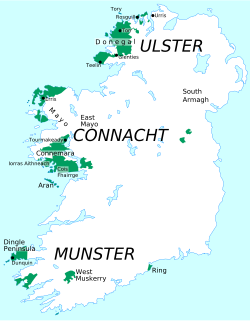

Percentage of population in each administrative area (Counties in Republic of Ireland and District council areas in Northern Ireland) in Ulster who can speak Irish. | |

Ulster Irish (endonym: Gaeilg Uladh or Irish: Gaeilic Uladh, Standard Irish: Gaeilge Uladh) is the variety of Irish spoken in the province of Ulster. It has much in common with Scottish Gaelic and Manx. Within Ulster there have historically been two main sub-dialects: West Ulster and East Ulster. The Western dialect is spoken in parts of County Donegal and was once spoken in parts of neighbouring counties, hence the name 'Donegal Irish'. The Eastern dialect was spoken in most of the rest of Ulster and northern parts of counties Louth and Meath.[1]

History

[edit]Ulster Irish was the main language spoken in most of Ulster from the earliest recorded times even before Ireland became a jurisdiction in the 1300s. Since the Plantation, Ulster Irish was steadily replaced by English and Ulster Scots, largely as a result of incoming settlers. The Eastern dialect died out in the 20th century, but the Western lives on in the Gaeltacht region of County Donegal. In 1808, County Down natives William Neilson and Patrick Lynch (Pádraig Ó Loingsigh) published a detailed study on Ulster Irish. Both Neilson and his father were Ulster-speaking Presbyterian ministers. When the recommendations of the first Comisiún na Gaeltachta were drawn up in 1926, there were regions qualifying for Gaeltacht recognition in the Sperrins and the northern Glens of Antrim and Rathlin Island. The report also makes note of small pockets of Irish speakers in northwest County Cavan, southeast County Monaghan, and the far south of County Armagh. However, these small pockets vanished early in the 20th century while Ulster Irish in the Sperrins survived until the 1950s and in the Glens of Antrim until the 1970s. The last native speaker of Rathlin Irish died in 1985.

According to Innti poet and scholar of Modern literature in Irish Louis de Paor, Belfast Irish, "a new urban dialect", of Ulster Irish, was "forged in the heat of Belfast during The Troubles" and is the main language spoken in the Gaeltacht Quarter of the city. The same dialect, according to de Paor, has been used in the poetry of Gearóid Mac Lochlainn and other radically innovative writers like him.[2]

Phonology

[edit]Consonants

[edit]The phonemic consonant inventory of Ulster Irish (based on the dialect of Gweedore[3]) is as shown in the following chart (see International Phonetic Alphabet for an explanation of the symbols). Symbols appearing in the upper half of each row are velarized (traditionally called "broad" consonants) while those in the bottom half are palatalized ("slender"). The consonants /h, n, l/ are neither broad nor slender.

| Consonant phonemes |

Labial | Coronal | Dorsal | Glottal | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Labio- velar |

Dental | Alveolar | Alveolo- palatal |

Palatal | Velar | |||||||||||

| Plosive | pˠ pʲ |

bˠ bʲ |

t̪ˠ |

d̪ˠ |

ṯʲ |

ḏʲ |

c |

ɟ |

k |

ɡ |

||||||||

| Fricative/ Approximant |

fˠ fʲ |

vʲ |

w |

sˠ |

ʃ |

ç |

j |

x |

ɣ |

h | ||||||||

| Nasal | mˠ mʲ |

n̪ˠ |

n | ṉʲ |

ɲ |

ŋ |

||||||||||||

| Tap | ɾˠ ɾʲ |

|||||||||||||||||

| Lateral approximant |

l̪ˠ |

l | ḻʲ |

|||||||||||||||

Some characteristics of the phonology of Ulster Irish that distinguish it from the other dialects are:

- /w/ is always the approximant [w]. In other dialects, fricative [vˠ] is found instead of or in addition to [w]. No dialect makes a phonemic contrast between the approximant and the fricative, however.

- There is a three-way distinction among coronal nasals, /n̪ˠ, n, ṉʲ/, and laterals, /l̪ˠ, l, ḻʲ/, as there is in Scottish Gaelic, and there is no lengthening or diphthongization of short vowels before these sounds and /m/. Thus, while ceann "head" is /cɑːn/ in Connacht and /caun/ in Munster, in Ulster it is /can̪ˠ/ (compare Scottish Gaelic /kʲaun̪ˠ/)

- ⟨n⟩ is pronounced as if it is spelled ⟨r⟩ (/ɾˠ/ or /ɾʲ/) after consonants other than ⟨s⟩. This happens in Connacht and Scottish Gaelic as well.

- /x/ is often realised as [h] and can completely disappear word finally, hence unstressed -⟨ach⟩ (a common suffix) is realised as [ax], [ah], or [a]. For some speakers /xt/ is realised as [ɾˠt].[citation needed]

Vowels

[edit]The vowels of Ulster Irish are as shown on the following chart. These positions are only approximate, as vowels are strongly influenced by the palatalization and velarization of surrounding consonants.

The long vowels have short allophones in unstressed syllables and before /h/. In addition, Ulster has the diphthongs /ia, ua, au/.

- Before /x/, where an unstressed schwa is found in other dialects, Ulster has [a] with secondary stress (identical to /aː/), e.g. feargach /ˈfʲaɾˠəɡa(x)/ "angry" and iománaíocht /ˈɔmˠaːnˠiaxt̪ˠ/ "hurling".

- /aː/ is more fronted in Ulster than Connacht and Munster (where it is [ɑː]), as [aː] or even [æː~ɛ̞ː] preceding slender consonants. Unstressed ⟨eoi⟩ and ⟨ói⟩ merge with ⟨ái⟩ as /aː/ ([æ~ɛ̞]).

- Stressed word final ⟨(e)aith⟩, ⟨oith⟩, and /ah, ɔh/ preceding a syllable containing /iː/ tend to represent /əih/. For example /mˠəih/ maith "good" and /ˈkəihiːɾʲ/ cathaoir "chair", in contrast to /mˠah/ and /ˈkahiːɾʲ/ found in other regions.

- Stressed ⟨(e)adh(a(i))⟩, ⟨(e)agh(a(i))⟩, as well as ⟨ia⟩ after an initial ⟨r⟩, represent /ɤː/ which generally merges with /eː/ in younger speech.

- /eː/ has three main allophones: [eː] morpheme finally and after broad consonants, [ɛə] before broad consonants, [ei] before slender consonants.

- Stressed ⟨eidh(e(a))⟩ and ⟨eigh(e(a))⟩ represent /eː/ rather than /əi/ which is found in the other dialects.

- /iː/ before broad consonants merges with /iə/, and vice versa. That is, /iə/ merges with /iː/ before slender consonants.

- ⟨ao⟩ represents [ɯː] for many speakers, but it often merges with /iː/ especially in younger speech.

- ⟨eo(i)⟩ and ⟨ó(i)⟩ are pronounced [ɔː], unless beside ⟨m, mh, n⟩ where they raise to [oː], the main realisation in other dialects, e.g. /fˠoːnˠ ˈpˠɔːkə/ fón póca "mobile phone".

- Stressed ⟨(e)abha(i)⟩, ⟨(e)obh(a(i))⟩, ⟨(e)odh(a(i))⟩ and ⟨(e)ogh(a(i))⟩ mainly represent [oː], not /əu/ as in the other dialects.

- Word final unstressed ⟨(e)adh⟩ represents /uː/, not /ə/ as in the other dialects,[4] e.g. /ˈsˠauɾˠuː/ for samhradh "summer".

- Word final /əw/ ⟨bh, (e)abh, mh, (e)amh⟩ and /əj/ ⟨(a)idh, (a)igh⟩ merge with /uː/ and /iː/, respectively, e.g. /ˈl̠ʲanˠuː/ leanbh "baby", /ˈdʲaːnˠuː/ déanamh "make", /ˈsˠauɾˠiː/ samhraidh "summer (gen.)" and /ˈbˠalʲiː/ bailigh "collect". Both merge with /ə/ in Connacht, while in Munster, they are realised [əvˠ] and [əɟ], respectively.

- According to Ó Dochartaigh (1987), the loss of final schwa "is a well-attested feature of Ulster Irish", e.g. [fˠad̪ˠ] for /fˠad̪ˠə/ fada "long".[5]

East Ulster and West Ulster

[edit]Differences between the Western and Eastern sub-dialects of Ulster included the following:

- In West Ulster and most of Ireland, the vowel written ⟨ea⟩ is pronounced [a] (e.g. fear [fʲaɾˠ]), but in East Ulster it was pronounced [ɛ] (e.g. fear /fʲɛɾˠ/ as it is in Scottish Gaelic (/fɛɾ/). J. J. Kneen comments that Scottish Gaelic and Manx generally follow the East Ulster pronunciation. The name Seán is pronounced [ʃɑːnˠ] in Munster and [ʃæːnˠ] in West Ulster, but [ʃeːnˠ] in East Ulster, whence anglicized spellings like Shane O'Neill and Glenshane.[1]

- In East Ulster, ⟨th, ch⟩ in the middle of a word tended to vanish and leave one long syllable. William Neilson wrote that this happens "in most of the counties of Ulster, and the east of Leinster".[1]

- Neilson wrote /w/ was [vˠ], especially at the beginning or end of a word "is still retained in the North of Ireland, as in Scotland, and the Isle of Man", whereas "throughout Connaught, Leinster and some counties of Ulster, the sound of [w] is substituted". However, broad ⟨bh, mh⟩ may become [w] in the middle of a word (for example in leabhar "book").[1]

Morphology

[edit]Initial mutations

[edit]Ulster Irish has the same two initial mutations, lenition and eclipsis, as the other two dialects and the standard language, and mostly uses them the same way. There is, however, one exception: in Ulster, a dative singular noun after the definite article is lenited (e.g. ar an chrann "on the tree") (as is the case in Scottish and Manx), whereas in Connacht and Munster, it is eclipsed (ar an gcrann), except in the case of den, don and insan, where lenition occurs in literary language. Both possibilities are allowed for in the standard language.

Verbs

[edit]Irish verbs are characterized by having a mixture of analytic forms (where information about person is provided by a pronoun) and synthetic forms (where information about number is provided in an ending on the verb) in their conjugation. In Ulster and North Connacht the analytic forms are used in a variety of forms where the standard language has synthetic forms, e.g. molann muid "we praise" (standard molaimid, muid being a back formation from the verbal ending -mid and not found in the Munster dialect, which retains sinn as the first person plural pronoun as do Scottish Gaelic and Manx) or mholfadh siad "they would praise" (standard mholfaidís). The synthetic forms, including those no longer emphasised in the standard language, may be used in short answers to questions.

The 2nd conjugation future stem suffix in Ulster is -óch- (pronounced [ah]) rather than -ó-, e.g. beannóchaidh mé [bʲan̪ˠahə mʲə] "I will bless" (standard beannóidh mé [bʲanoːj mʲeː]).

Some irregular verbs have different forms in Ulster from those in the standard language. For example:

- (gh)níom (independent form only) "I do, make" (standard déanaim) and rinn mé "I did, made" (standard rinne mé)

- tchíom [t̠ʲʃiːm] (independent form only) "I see" (standard feicim, Southern chím, cím (independent form only))

- bheiream "I give" (standard tugaim, southern bheirim (independent only)), ní thabhram or ní thugaim "I do not give" (standard only ní thugaim), and bhéarfaidh mé/bheirfidh mé "I will give" (standard tabharfaidh mé, southern bhéarfad(independent form only))

- gheibhim (independent form only) "I get" (standard faighim), ní fhaighim "I do not get"

- abraim "I say, speak" (standard deirim, ní abraim "I do not say, speak", although deir is used to mean "I say" in a more general sense.)

Particles

[edit]In Ulster the negative particle cha (before a vowel chan, in past tenses char - Scottish Gaelic/Manx chan, cha do) is sometimes used where other dialects use ní and níor. The form is more common in the north of the Donegal Gaeltacht. Cha cannot be followed by the future tense: where it has a future meaning, it is followed by the habitual present.[6][7] It triggers a "mixed mutation": /t/ and /d/ are eclipsed, while other consonants are lenited. In some dialects however (Gweedore), cha eclipses all consonants, except b- in the forms of the verb "to be", and sometimes f-:

| Ulster | Standard | English |

|---|---|---|

| Cha dtuigim | Ní thuigim | "I don't understand" |

| Chan fhuil sé/Cha bhfuil sé | Níl sé (contracted from ní fhuil sé) | "He isn't" |

| Cha bhíonn sé | Ní bheidh sé | "He will not be" |

| Cha phógann muid/Cha bpógann muid | Ní phógaimid | "We do not kiss" |

| Chan ólfadh siad é | Ní ólfaidís é | "They wouldn't drink it" |

| Char thuig mé thú | Níor thuig mé thú | "I didn't understand you" |

In the Past Tense, some irregular verbs are lenited/eclipsed in the Interrogative/Negative that differ from the standard, due to the various particles that may be preferred:

| Interrogative | Negative | English |

|---|---|---|

| An raibh tú? | Cha raibh mé | "I was not" |

| An dtearn tú? | Cha dtearn mé | "I did not do, make" |

| An dteachaigh tú? | Cha dteachaigh mé | "I did not go" |

| An dtáinig tú? | Cha dtáinig mé | "I did not come" |

| An dtug tú? | Cha dtug mé | "I did not give" |

| Ar chuala tú? | Char chuala mé | "I did not hear" |

| Ar dhúirt tú? | Char dhúirt mé | "I did not say" |

| An bhfuair tú? | Chan fhuair mé | "I did not get" |

| Ar rug tú? | Char rug mé | "I did not catch, bear" |

| Ar ith tú? | Char ith mé | "I did not eat" |

| Ar chígh tú/An bhfaca tú? | Chan fhaca mé | "I did not see" |

Syntax

[edit]The Ulster dialect uses the present tense of the subjunctive mood in certain cases where other dialects prefer to use the future indicative:

- Suigh síos anseo ag mo thaobh, a Shéimí, go dtugaidh (dtabhairidh, dtabhraidh) mé comhairle duit agus go n-insidh mé mo scéal duit.

- Sit down here by my side, Jamie, till I give you some advice and tell you my story.

The verbal noun can be used in subordinate clauses with a subject different from that of the main clause:

- Ba mhaith liom thú a ghabháil ann.

- I would like you to go there.

Lexicon

[edit]The Ulster dialect contains many words not used in other dialects—of which the main ones are Connacht Irish and Munster Irish—or used otherwise only in northeast Connacht. The standard form of written Irish is now An Caighdeán Oifigiúil. In other cases, a semantic shift has resulted in quite different meanings attaching to the same word in Ulster Irish and in other dialects. Some of these words include:

- ag déanamh is used to mean "to think" as well as "to make" or "to do", síleann, ceapann and cuimhníonn is used in other dialects, as well as in Ulster Irish.

- amharc or amhanc (West Ulster), "look" (elsewhere amharc, breathnaigh and féach; this latter means rather "try" or "attempt" in Ulster)

- barúil "opinion", southern tuairim - in Ulster, tuairim is most typically used in the meaning "approximate value", such as tuairim an ama sin "about that time". Note the typically Ulster derivatives barúlach and inbharúla "of the opinion (that...)".

- bealach, ród "road" (southern and western bóthar and ród (cf. Scottish Gaelic rathad, Manx raad), and bealach "way"). Note that bealach alone is used as a preposition meaning "towards" (literally meaning "in the way of": d'amharc sé bealach na farraige = "he looked towards the sea"). In the sense "road", Ulster Irish often uses bealach mór (lit. "big road") even for roads that aren't particularly big or wide.

- bomaite, "minute" (elsewhere nóiméad, nóimint, neómat, etc., and in Mayo Gaeltacht areas a somewhat halfway version between the northern and southern versions, is the word "móiméad", also probably the original, from which the initial M diverged into a similar nasal N to the south, and into a similar bilabial B to the north.)

- cá huair, "when?" (Connacht cén uair; Munster cathain, cén uair)

- caidé (cad é) atá?, "what is?" (Connacht céard tá; Munster cad a thá, cad é a thá, dé a thá, Scottish Gaelic dé tha)

- cál, "cabbage" (southern gabáiste; Scottish Gaelic càl)

- caraidh, "weir" (Connacht cara, standard cora)

- cluinim, "I hear" (southern cloisim, but cluinim is also attested in South Tipperary and is also used in Achill and Erris in North and West Mayo). In fact, the initial c- tends to be lenited even when it is not preceded by any particle (this is because there was a leniting particle in Classical Irish: do-chluin yielded chluin in Ulster)

- doiligh, "hard"-as in difficult (southern deacair), crua "tough"

- druid, "close" (southern and western dún; in other dialects druid means "to move in relation to or away from something", thus druid ó rud = to shirk, druid isteach = to close in) although druid is also used in Achill and Erris

- eallach, "cattle" (southern beithíoch = "one head of cattle", beithígh = "cattle", "beasts")

- eiteogaí, "wings" (southern sciatháin)

- fá, "about, under" (standard faoi, Munster fé, fí and fá is only used for "under"; mar gheall ar and i dtaobh = "about"; fá dtaobh de = "about" or "with regard to")

- falsa, "lazy" (southern and western leisciúil, fallsa = "false, treacherous") although falsa is also used in Achill and Erris

- faoileog, "seagull" (standard faoileán)

- fosta, "also" (standard freisin)

- Gaeilg, Gaeilig, Gaedhlag, Gaeilic, "Irish" (standard and Western Gaeilge, Southern Gaoluinn, Manx Gaelg, Scottish Gaelic Gàidhlig) although Gaeilg is used in Achill and was used in parts of Erris and East Connacht

- geafta, "gate" (standard geata)

- gairid, "short" (southern gearr)

- gamhain, "calf" (southern lao and gamhain) although gamhain is also used in Achill and Erris

- gasúr, "boy" (southern garsún; garsún means "child" in Connemara)

- girseach, "girl" (southern gearrchaile and girseach)

- gnóitheach, "busy" (standard gnóthach)

- inteacht, an adjective meaning "some" or "certain" is used instead of the southern éigin. Áirithe also means "certain" or "particular".

- mothaím is used to mean "I hear, perceive" as well as "I feel" (standard cloisim) but mothaím generally refers to stories or events. The only other place where mothaím is used in this context is in the Irish of Dún Caocháin and Ceathrú Thaidhg in Erris but it was a common usage throughout most of northern and eastern Mayo, Sligo, Leitrim and North Roscommon

- nighean, "daughter" (standard iníon; Scottish Gaelic nighean)

- nuaidheacht, "news" (standard nuacht, but note that even Connemara has nuaíocht)

- sópa, "soap" (standard gallúnach, Connemara gallaoireach)

- stócach, "youth", "young man", "boyfriend" (Southern = "gangly, young lad")

- tábla, "table" (western and southern bord and clár, Scottish Gaelic bòrd)

- tig liom is used to mean "I can" as opposed to the standard is féidir liom or the southern tá mé in ann. Tá mé ábalta is also a preferred Ulster variant. Tig liom and its derivatives are also commonly used in the Irish of Joyce Country, Achill and Erris

- the word iontach "wonderful" is used as an intensifier instead of the prefix an- used in other dialects.

Words generally associated with the now dead East Ulster Irish include:[1]

- airigh (feel, hear, perceive) - but also known in more southern Irish dialects

- ársuigh, more standardized ársaigh (tell) - but note the expression ag ársaí téamaí "telling stories, spinning yearns" used by the modern Ulster writer Séamus Ó Grianna.

- coinfheascar (evening)

- corruighe, more standardized spelling corraí (anger)

- frithir (sore)

- go seadh (yet)

- márt (cow)

- práinn (hurry)

- toigh (house)

- tonnóg (duck)

In other cases, a semantic shift has resulted in quite different meanings attaching to the same word in Ulster Irish and in other dialects. Some of these words include:

- cloigeann "head" (southern and western ceann; elsewhere, cloigeann is used to mean "skull")

- capall "mare" (southern and western láir; elsewhere, capall means "horse")

Notable speakers

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2022) |

Some notable Irish singers who sing songs in the Ulster Irish dialect include Maighread Ní Dhomhnaill, Mairéad Ní Mhaonaigh, Róise Mhic Ghrianna, and Pádraigín Ní Uallacháin.

Notable Ulster Irish writers include Micí Mac Gabhann, Seosamh Mac Grianna, Peadar Toner Mac Fhionnlaoich, Cosslett Ó Cuinn, Niall Ó Dónaill, Séamus Ó Grianna, Brian Ó Nualláin, Colette Ní Ghallchóir and Cathal Ó Searcaigh.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Ó Duibhín 1997, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Louis de Paor (2016), Leabhar na hAthghabhála: Poems of Repossession: Irish-English Bilingual Edition, Bloodaxe Books. Page 27.

- ^ Ní Chasaide 1999, pp. 111–16.

- ^ Ó Broin, Àdhamh. "Essay on Dalriada Gaelic" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ PlaceNames NI: Townland of Moyad Upper[permanent dead link]

- ^ Ó Dónaill 1977, p. 221.

- ^ Ó Baoill 2009, p. 55.

Bibliography

[edit]- Hamilton, John Noel (1974). A Phonetic Study of the Irish of Tory Island, Co. Donegal. Studies in Irish Language and Literature. Vol. 3. Belfast: Institute of Irish Studies, Queen's University of Belfast.

- Hodgins, Tom (2013). Dea-Chaint John Ghráinne agus a chairde (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim.

- Hughes, A. J. (2009). An Ghaeilge ó Lá go Lá - Irish Day by Day. Belfast: Ben Madigan Press. ISBN 978-0-9542834-6-9. (book & 2 CDs in the Ulster dialect)

- —— (2016). Basic Irish Conversation and Grammar - Bunchomhrá Gaeilge agus Gramadach. Belfast: Ben Madigan Press. ISBN 978-0-9542834-9-0. (book & 2 CDs in the Ulster dialect)

- Hughes, Art (1994). "Gaeilge Uladh". In McCone, Kim (ed.). Stair na Gaeilge (in Irish). Maigh Nuad: Roinn na Sean-Ghaeilge, Coláiste Phádraig.

- Lucas, Leslie W. (1979). Grammar of Ros Goill Irish, Co. Donegal. Studies in Irish Language and Literature. Vol. 5. Belfast: Institute of Irish Studies, Queen's University of Belfast.

- Lúcás, Leaslaoi U. (1986). de Bhaldraithe, Tomás (ed.). Cnuasach focal as Ros Goill. Deascán Foclóireachta (in Irish). Vol. 5. Baile Átha Cliath: Acadamh Ríoga na hÉireann.

- Mac Congáil, Nollaig (1983). Scríbhneoirí Thír Chonaill (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Foilseacháin Náisiúnta Teoranta.

- Mac Maoláin, Seán (1933). Cora Cainnte as Tír Ċonaill (in Irish). Baile Áṫa Cliaṫ: Oifig Díolta Foillseaċáin Rialtais.

- Ní Chasaide, Ailbhe (1999). "Irish". Handbook of the International Phonetic Association. Cambridge University Press. pp. 111–16. ISBN 0-521-63751-1.

- Ó Baoill, Colm (1978). Contributions to a Comparative Study of Ulster Irish & Scottish Gaelic. Studies in Irish Language and Literature. Vol. 4. Belfast: Institute of Irish Studies, Queen's University of Belfast.

- Ó Baoill, Dónall P. (1996). An Teanga Bheo: Gaeilge Uladh (in Irish). Institiúid Teangeolaíochta Éireann. ISBN 0-946452-85-7.

- Ó Corráin, Ailbhe (1989). A Concordance of Idiomatic Expressions in the Writings of Seamus Ó Grianna. Belfast: Institute of Irish Studies, Queen's University of Belfast.

- Ó Dónaill, Niall (1977). Foclóir Gaeilge-Béarla. Dublin: Oifig an tSoláthair.

- Ó Dochartaigh, Cathair (1987). Dialects of Ulster Irish. Studies in Irish Language and Literature. Vol. 7. Belfast: Institute of Irish Studies, Queen's University of Belfast.

- Ó Duibhín, Ciarán (1997). "The Irish Language in County Down". In Proudfoot, L J (ed.). Down: History & Society. Geography Publications.

- Ó hAirt, Diarmuid, ed. (1993). "Cnuasach Conallach: A Computerized Dictionary of Donegal Irish" (in Irish). Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- Ó hEochaidh, Seán (1955). Sean-chainnt Theilinn (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Institiúid Ard-Léighinn Bhaile Átha Cliath.

- Uí Bheirn, Úna M. (1989). de Bhaldraithe, Tomás (ed.). Cnuasach Focal as Teileann. Deascán Foclóireachta (in Irish). Vol. 8. Baile Átha Cliath: Acadamh Ríoga na hÉireann.

- Wagner, Heinrich (1959). Gaeilge Theilinn: Foghraidheacht, Gramadach, Téacsanna (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Institiúid Árd-Léinn Bhaile Átha Cliath.

- —— (1958). Linguistic Atlas and Survey of Irish Dialects. Vol. I. Introduction, 300 maps. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. ISBN 0-901282-05-7.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ——; Ó Baoill, Colm (1969). Linguistic Atlas and Survey of Irish Dialects. Vol. IV. The Dialects of Ulster and the Isle of Man, Specimens of Scottish Gaelic Dialects, Phonetic Texts of East Ulster Irish. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. ISBN 0-901282-05-7.

Literature

[edit]- Hodgins, Tom (2007). 'Rhetoric of Beauty': An Slabhra gan Bhriseadh - Filíocht, Seanchas agus Cuimhní Cinn as Rann na Feirste (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim. [Rannafast]

- Mac a' Bhaird, Proinsias (2002). Cogar san Fharraige. Scéim na Scol in Árainn Mhóir, 1937-1938 (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim. [folklore, Arranmore Island]

- Mac Cionaoith, Maeleachlainn (2005). Seanchas Rann na Feirste: Is fann guth an éin a labhras leis féin (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim. [folklore, Rannafast]

- Mac Cumhaill, Fionn (1974). Gura Slán le m'Óige (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Oifig an tSoláthair. [novel, the Rosses]

- —— (1997). Na Rosa go Brách (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: An Gúm. [novel, the Rosses]

- —— (1998). Slán Leat, a Mhaicín. Úrscéal do Dhaoine Óga (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: An Gúm. [novel, the Rosses]

- Mac Fhionnlaoich, Seán (1983). Scéal Ghaoth Dobhair (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Foilseacháin Náisiúnta Teoranta. [local history, Gweedore]

- Mac Gabhann, Micí; Ó hEochaidh, Seán (1959). Ó Conluain, Proinsias (ed.). Rotha Mór an tSaoil (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Foilseacháin Náisiúnta Teoranta. [autobiography, Ulster]

- Mac Giolla Domhnaigh, Gearóid; Stockman, Gearóid, eds. (1991). Athchló Uladh (in Irish). Comhaltas Uladh. [folklore, East Ulster: Antrim, Rathlin Island]

- Mac Giolla Easbuic, Mícheál, ed. (2008). Ón tSeanam Anall: Scéalta Mhicí Bháin Uí Bheirn (in Irish). Indreabhán: Cló Iar-Chonnachta. [Kilcar]

- Mac Grianna, Seosamh (1936). Pádraic Ó Conaire agus Aistí Eile (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Oifig Díolta Foillseacháin Rialtais. [essays, the Rosses]

- —— (1940). Mo Bhealach Féin agus Dá mBíodh Ruball ar an Éan (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Oifig an tSoláthair. [autobiography, unfinished novel, the Rosses]

- —— (1969). An Druma Mór (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Oifig an tSoláthair. [novel, the Rosses]

- MacLennan, Gordon W. (1997). Harrison, Alan; Crook, Máiri Elena (eds.). Seanchas Annie Bhán: The Lore of Annie Bhán (in Irish and English). Translated by Harrison, Alan; Crook, Máiri Elena. Seanchas Annie Bhán Publication Committee. ISBN 1898473846. [folklore, Rannafast]

- —— (1940). Ó Cnáimhsí, Séamus (ed.). Mám as mo mhála (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Oifig an tSoláthair. [short stories]

- Mac Meanman, Seán Bán (1989). —— (ed.). Cnuasach Céad Conlach (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim. [folklore]

- —— (1990). —— (ed.). An Chéad Mhám (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim. [short stories]

- —— (1992). —— (ed.). An Tríú Mám (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim. [essays]

- Mac Seáin, Pádraig (1973). Ceolta Theilinn. Studies in Irish Language and Literature. Vol. 1. Belfast: Institute of Irish Studies, Queen's University of Belfast.

- McGlinchey, Charles; Kavanagh, Patrick (2002). Kavanagh, Desmond; Mac Congáil, Nollaig (eds.). An Fear Deireanach den tSloinneadh (in Irish). Galway: Arlen House. [autobiography, Inishowen]

- Ní Bhaoill, Róise, ed. (2010). Ulster Gaelic Voices: Bailiúchán Doegen 1931 (in Irish and English). Béal Feirste: Iontaobhas Ultach.

- Nic Aodháin, Medhbh Fionnuala, ed. (1993). Báitheadh iadsan agus tháinig mise (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim. [legends, Tyrconnell]

- Nic Giolla Bhríde, Cáit (1996). Stairsheanchas Ghaoth Dobhair (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim. [history, folklore, memoirs, the Rosses]

- Ó Baoighill, Pádraig (1993). An Coileach Troda agus scéalta eile (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim. [short stories, the Rosses]

- —— (1994). Cuimhní ar Dhochartaigh Ghleann Fhinne (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim. [biography, essays, the Rosses]

- —— (1994). Óglach na Rosann : Niall Pluincéad Ó Baoighill (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim. [life story, the Rosses]

- —— (1998). Nally as Maigh Eo (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim. [biography, the Rosses]

- —— (2000). Gaeltacht Thír Chonaill - Ó Ghleann go Fánaid (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim. [local tradition, the Rosses]

- ——; Ó Baoill, Mánus, eds. (2001). Amhráin Hiúdaí Fheilimí agus Laoithe Fiannaíochta as Rann na Feirste (in Irish). Muineachán: Preas Uladh.

- —— (2001). Srathóg Feamnaí agus Scéalta Eile (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim. [short stories, the Rosses]

- —— (2003). Ceann Tìre/Earraghàidheal: Ár gComharsanaigh Ghaelacha (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim. [travel book]

- —— (2004). Gasúr Beag Bhaile na gCreach (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim.

- ——, ed. (2005). Faoi Scáth na Mucaise: Béaloideas Ghaeltachtaí Imeallacha Thír Chonaill (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim.

- Ó Baoill, Dónall P., ed. (1992). Amach as Ucht na Sliabh (in Irish). Vol. 1. Cumann Staire agus Seanchais Ghaoth Dobhair.

- ——, ed. (1996). Amach as Ucht na Sliabh (in Irish). Vol. 2. Cumann Staire agus Seanchais Ghaoth Dobhair i gcomhar le Comharchumann Forbartha Ghaoth Dobhair. [folklore, Gweedore] [folklore, Gweedore]

- Ó Baoill, Micí Sheáin Néill (1956). Mag Uidhir, Seosamh (ed.). Maith Thú, A Mhicí (in Irish). Béal Feirste: Irish News Teoranta. [folklore, Rannafast]

- Ó Baoill, Micí Sheáin Néill (1983). Ó Searcaigh, Lorcán (ed.). Lá De na Laethaibh (in Irish). Muineachán: Cló Oirghialla. [folklore, Rannafast]

- Ó Colm, Eoghan (1971). Toraigh na dTonn (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Foilseacháin Náisiúnta Teoranta. [memoirs and local history, Tory Island/Magheroarty]

- Ó Cuinn, Cosslett (1990). Ó Canainn, Aodh; Watson, Seosamh (eds.). Scian A Caitheadh le Toinn : Scéalta agus amhráin as Inis Eoghain agus cuimhne ar Ghaeltacht Iorrais (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim. [folklore, Tír Eoghain]

- Ó Donaill, Eoghan (1940). Scéal Hiúdaí Sheáinín (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Oifig an tSoláthair. [biography, folklore, the Rosses]

- Ó Donaill, Niall (1942). Seanchas na Féinne (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Oifig an tSoláthair. [mythology, the Rosses]

- —— (1974). Na Glúnta Rosannacha (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Oifig an tSoláthair. [local history, the Rosses]

- Ó Duibheannaigh, John Ghráinne (2008). An áit a n-ólann an t-uan an bainne (in Irish). Béal Feirste: Cló na Seaneagliase. ISBN 978-0-9558388-0-4. [Rannafast] (book & 1 CD in the Ulster dialect)

- Ó Gallachóir, Pádraig (2008). Seachrán na Mic Uí gCorra (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim. [novel]

- Ó Gallchóir, Tomás (1996). Séimidh agus Scéalta Eile (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim. [the Rosses]

- Ó Grianna, Séamus (1924). Caisleáin Óir (in Irish). Sráid Bhaile Dúin Dealgan: Preas Dhún Dealgan. [novel, the Rosses]

- —— (1942). Nuair a Bhí Mé Óg (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Clólucht an Talbóidigh. [autobiography, the Rosses]

- —— (1961). Cúl le Muir agus Scéalta Eile (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Oifig an tSoláthair. [short stories, the Rosses]

- —— (1968). An Sean-Teach (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Oifig an tSoláthair. [novel, the Rosses]

- —— (1976). Cith is Dealán (in Irish). Corcaigh: Cló Mercier. [short stories the Rosses]

- —— (1983). Tairngreacht Mhiseoige (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: An Gúm. [novel, the Rosses]

- —— (1993). Cora Cinniúna (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: An Gúm. ISBN 1-85791-0737. [short stories, the Rosses]

- —— (2002). Mac Congáil, Nollaig (ed.). Castar na Daoine ar a Chéile. Scríbhinní Mháire (in Irish). Vol. 1. Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim. [novel, the Rosses]

- —— (2003). — (ed.). Na Blianta Corracha. Scríbhinní Mháire (in Irish). Vol. 2. Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim. [the Rosses]

- Ó Laighin, Donnchadh C. (2004). An Bealach go Dún Ulún (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Coiscéim. ISBN 978-1-9024208-2-0. [Kilcar]

- Ó Muirgheasa, Énrí (1907). Seanfhocla Uladh (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Connradh na Gaedhilge. [folklore]

- Ó Searcaigh, Cathal (1993). An Bealach 'na Bhaile. Indreabhán: Cló Iar-Chonnachta.

- —— (2004). Seal i Neipeal (in Irish). Indreabhán: Cló Iar-Chonnachta. ISBN 1902420608. [travel book, Gortahork]

- Ó Searcaigh, Séamus (1945). Laochas: Scéalta as an tSeanlitríocht (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: An Gúm. [mythology, the Rosses]

- —— (1997). Beatha Cholm Cille (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: An Gúm. [the Rosses]

- Ua Cnáimhsí, Pádraig (1997). Grae, Micheál (ed.). Idir an Dá Ghaoth: Scéal Mhuintir na Rosann (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Sáirséal Ó Marcaigh. ISBN 0-86289-073-X. [local history, the Rosses]

External links

[edit]- Gaelic resources focusing on Ulster Irish (in Irish)

- A Yahoo group for learners of Ulster Irish Archived 2013-01-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Oideas Gael (based in Glencolmcille)

- The Spoken Irish of Rann na Feirste

Ulster Irish

View on GrokipediaUlster Irish (Gaeilge Uladh) is the dialect of the Irish language historically spoken across the province of Ulster in northern Ireland, distinguished as one of the three primary dialect groups of modern Irish alongside Connacht and Munster varieties.[1][2] This dialect emerged prominently after the mid-17th century amid the fragmentation of earlier standardized forms of Irish, forming part of a linguistic continuum with Scottish Gaelic and incorporating Celtic grammatical traits such as initial consonant mutations and verb-subject-object word order.[1][2] Prior to the 17th century, Ulster Irish served as the dominant vernacular in the region, rooted in medieval Gaelic society, but its widespread use eroded following the Plantation of Ulster in 1609, which brought substantial English and Scots settlement and initiated demographic and economic pressures favoring language shift to English.[3] Subsequent events, including the 1740–41 famine, the Great Famine of the 1840s with its massive mortality and emigration, and policies marginalizing Catholic Irish speakers, accelerated the decline, reducing Irish usage below 5% in Ulster by the late 19th century.[3] Phonological influences from contact with English and Scots appeared in surviving varieties, such as shifts in consonant distinctions, though the dialect retained unique features like preaspiration in stops and specialized vowel alternations.[3][4] In the present day, Ulster Irish persists mainly as a native language in Gaeltacht pockets of County Donegal, the Sperrin Mountains, and isolated areas like the Antrim Glens, with approximately 5,000 speakers recorded in Northern Ireland's 2011 census data for Irish overall, though native proficiency in the dialect remains limited.[3] Efforts to preserve and revive it, including through organizations like the Ultach Trust, have met with modest success amid broader sociolinguistic challenges, as the dialect faces ongoing attrition from English dominance and intergenerational transmission gaps.[3] Its defining characteristics continue to inform linguistic studies, highlighting resilience in peripheral rural communities despite centuries of causal pressures toward extinction.[4]

Historical Background

Pre-Plantation Era

The Irish language in Ulster evolved continuously from the Old Irish period (c. 600–900 AD), when the earliest vernacular texts were composed, reflecting a standardized form derived from earlier Primitive Irish inscriptions dating to the 4th–6th centuries AD.[5] This continuity is evident in the Ulster Cycle of heroic sagas, which preserve linguistic traits linked to oral traditions originating in the 7th–8th centuries AD, including synthetic verb forms and alliterative prose styles characteristic of pre-Norman Gaelic literature.[6] Manuscripts such as Lebor na hUidre (Book of the Dun Cow, compiled c. 1100 AD) contain core Ulster Cycle narratives like Táin Bó Cúailnge, demonstrating Middle Irish (c. 900–1200 AD) adaptations of these older Ulster-centric tales while retaining regional phonological and lexical markers, such as preserved initial mutations distinct from southern dialects.[7] These texts, centered on legendary Ulaid heroes like Cú Chulainn, underscore the province's role as a cradle for epic storytelling in Irish, with no evidence of significant non-Gaelic substrate influences in the core lexicon or grammar up to this era. Monastic scriptoria in Ulster, including those at Armagh (founded c. 455 AD) and Derry (c. 546 AD), were pivotal in transmitting the language through religious and secular manuscripts, with the Annals of Ulster—initiated in the late 7th century and actively scribed through the 11th—exemplifying bilingual (Irish-Latin) recording of provincial events in a form approximating spoken vernacular.[8] By the Early Modern Irish period (c. 1200–1600 AD), the dialect had stabilized into a classical standard used across Gaelic Ireland, but Ulster variants showed conservative retentions, such as broader vowel qualities and specific lenition patterns, as inferred from bardic poetry composed under local patronage.[9] Archaeological evidence from sites like Navan Fort, associated with Ulaid kingship, corroborates monolingual Irish usage in elite and communal contexts, with ogham stones and early Christian artifacts bearing Irish-derived names without substantive English or Norse lexical borrowings.[6] Under indigenous Gaelic lordships, such as those of the Uí Néill in central and eastern Ulster, the language functioned as the exclusive medium of governance, law (Brehon system), and annals-keeping, with hereditary poets (filí) maintaining syllabic verse traditions that reinforced dialectal continuity.[10] Viking raids from the 9th century introduced limited Norse terms (primarily nautical or trade-related, e.g., sgoth for boat), but these had negligible impact on Ulster's core Irish grammar or phonology compared to urban centers like Dublin, preserving a predominantly endogamous linguistic environment.[11] This stability persisted without major external pressures until the Tudor military campaigns of the 1550s–1590s, which initiated direct English administrative interference but did not yet displace Irish as the dominant vernacular in rural and chiefly domains.[12]Plantation of Ulster and Linguistic Shifts

The Nine Years' War (1594–1603) pitted Ulster's Gaelic chieftains, led by Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone, against English forces, culminating in decisive defeats that dismantled native military and political autonomy.[13] The war's resolution, including the Treaty of Mellifont in 1603, exposed vulnerabilities in Gaelic lordships, setting the stage for further consolidation of English control. The Flight of the Earls in September 1607, involving O'Neill and Rory O'Donnell, Earl of Tyrconnell, who departed Rathmullan harbor with ninety followers for mainland Europe, vacated central Ulster's leadership and facilitated land forfeitures totaling over 3 million acres.[13] This exodus, interpreted by English authorities as constructive treason, directly prompted King James VI and I's authorization of the Plantation of Ulster in 1609 as a systematic colonization to secure loyalty through Protestant settlement.[14] The plantation redistributed forfeited estates into proportions granted to undertakers—primarily English and Scottish Protestants—who were required to import tenants and build defenses, with schemes peaking in the 1610s and 1620s. By a 1622 survey, plantation lands hosted 6,402 British adult males, comprising roughly 3,100 English and 3,700 Scottish settlers, alongside estimates of up to 50,000 Scots crossing from Lowland regions in the prior decade.[15][14] These migrants, speaking English or Scots dialects mutually intelligible with it, formed nucleated settlements amid fragmented Irish-speaking populations, creating demographic mosaics where English administration, tenancy agreements, and markets incentivized code-switching and intergenerational transmission of settler languages over Irish.[16] The policy's scale—encompassing six escheated counties and targeting 40,000 households—diluted Irish linguistic density through spatial segregation and economic dependencies, initiating replacement dynamics observable in subsequent hearth tax rolls showing mixed-language tenancies.[17] Enacted amid post-Williamite consolidation, the Penal Laws from 1695 restricted Catholic inheritance, office-holding, and schooling, channeling education into informal hedge schools by the early 18th century to evade prohibitions like the 1695 Education Act barring foreign Catholic tuition. These pay-per-pupil operations, numbering thousands by mid-century, prioritized English literacy, arithmetic, and vocational skills for estate labor or emigration prospects, as Irish offered scant utility in Anglo-dominated courts and commerce.[18][19] While bilingual instruction persisted in rural settings, hedge curricula reflected pragmatic adaptation, with English fluency correlating to upward mobility and eroding Irish endogamy in multilingual households documented in lease agreements and parish registers.[20] This institutional pivot, absent direct bans on spoken Irish but reinforced by land tenure favoring English proficiency, accelerated monolingual English emergence among younger generations by the late 1700s.[21] The Great Famine (1845–1852), triggered by potato blight, prompted over 1 million Irish deaths and equivalent emigration island-wide, with Ulster counties like Antrim and Down registering 20–30% population losses among smallholders disproportionately reliant on Irish as a vernacular.[22][23] Emigration outflows, peaking at 200,000 annually post-1847, targeted North America and targeted Irish speakers in peripheral glens, contracting viable communities faster than natural attrition. Ordnance Survey memoirs compiled 1830–1838, drawing from local inquiries in parishes across Antrim, Derry, and Donegal, recorded residual Irish monoglot pockets—such as in Glenullin or Tory Island—where up to 80% of inhabitants spoke solely Irish, yet noted encroaching bilingualism and code-mixing as harbingers of dominance shift amid pre-famine tenurial pressures.[24] These accounts, grounded in empirical fieldwork, evidenced causation via speaker depletion and assimilation incentives, rather than uniform eradication.[25]Modern Decline and 20th-Century Census Data

The 20th-century decline of Ulster Irish, the dialect spoken natively in parts of Donegal and border areas of Northern Ireland, is reflected in census figures showing reduced numbers of speakers amid partition in 1921, which entrenched English as the administrative and educational medium in Northern Ireland, and socioeconomic pressures favoring English proficiency throughout Ulster. The 1911 census, the last all-island enumeration to include a language question, recorded 28,734 Irish speakers (about 4.7% of the population aged 3 and over) in the six counties of Northern Ireland, with much higher concentrations in Donegal county, where over 37% of the population reported Irish proficiency, yielding an estimated provincial total exceeding 80,000 speakers, predominantly native.[26] By contrast, Northern Ireland censuses omitted language queries until 1991, but extrapolations from local surveys and Republic of Ireland data for Ulster counties indicate a drop to roughly 10,000 speakers province-wide by 1961, as English-dominant schooling and limited institutional support eroded community use.[27] Post-World War II urbanization, emigration from rural Gaeltacht areas, and the dominance of English-language media further disrupted intergenerational transmission, reducing native Ulster Irish speakers to isolated elderly cohorts by the late 20th century. In Donegal, the Republic's primary Ulster Irish heartland, census percentages fell from 34.4% Irish speakers in 1926 to 21.3% by 1961, with absolute numbers halving amid population stagnation.[28] Northern Ireland's 1991 census, introducing an Irish question, reported 167,106 individuals (9.45% of the population) with some proficiency, but fluent native speakers numbered in the low thousands at most, concentrated among older generations and overshadowed by learner uptake.[29] The 2021 Northern Ireland census underscores the shift to non-native usage, with 165,030 people (10.4% aged 3+) reporting ability to speak Irish, but only 15,216 using it daily outside education—predominantly second-language learners rather than organic native speakers of the Ulster dialect, whose transmission has approached zero in community settings.[30] In Donegal's Gaeltacht districts, daily native use has similarly waned, with 2022 Republic data showing proficiency levels dropping consistently after age 18 due to English economic incentives, leaving Ulster Irish reliant on revitalization efforts rather than natural reproduction.[31]| Year | Irish Speakers in Donegal (approx.) | Percentage (aged 3+) |

|---|---|---|

| 1911 | 59,000 | 37% |

| 1926 | 51,000 | 34.4% |

| 1961 | 28,000 | 21.3% |

Phonological Features

Consonant Systems

Ulster Irish maintains the standard Irish distinction between broad (velarized) and slender (palatalized) consonants, with secondary articulation affecting nearly all obstruents and sonorants, as evidenced by acoustic analyses of native speakers showing F2 lowering for broad variants and raising for slender ones.%20-%20Timing%20of%20secondary%20articulations%20across%20syllable%20positions%20in%20Irish.pdf) The phonemic inventory includes bilabial, coronal, and velar stops (/pˠ bˠ t̪ˠ d̪ˠ kˠ gˠ/ and slender counterparts /pʲ bʲ tʲ dʲ cʲ ɟʲ/), fricatives (/fˠ vˠ sˠ ʃˠ xˠ ɣˠ/ and slender /fʲ vʲ sʲ ʃʲ çʲ j/), nasals (/mˠ mʲ ŋˠ ŋʲ/), and approximants (/w ʔ/), with coronal nasals and laterals exhibiting a three-way contrast (/n̪ˠ n ṉʲ/, /l̪ˠ l ḻʲ/) distinguishing dental broad, alveolar neutral, and palatal slender realizations.[32]%20-%20Timing%20of%20secondary%20articulations%20across%20syllable%20positions%20in%20Irish.pdf) Velar fricatives (/xˠ xʲ/, /ɣˠ ɣʲ/) are retained, with slender variants often fronted toward [ç, j], but without systemic absence compared to Connacht dialects.%20-%20Timing%20of%20secondary%20articulations%20across%20syllable%20positions%20in%20Irish.pdf)| Place/ Manner | Broad | Slender |

|---|---|---|

| Stops | pˠ bˠ t̪ˠ d̪ˠ kˠ gˠ | pʲ bʲ tʲ dʲ cʲ ɟʲ |

| Fricatives | fˠ vˠ sˠ ʃˠ xˠ ɣˠ | fʲ vʲ sʲ ʃʲ çʲ j |

| Nasals | mˠ n̪ˠ ŋˠ | mʲ ṉʲ ŋʲ |

| Laterals | l̪ˠ | l ḻʲ |

| Rhotic | ɾˠ | ɾʲ |

Vowel Systems and Regional Variations

The vowel system of Ulster Irish features a set of monophthongs and diphthongs that exhibit notable internal variation, distinguishing it from other Irish dialects. Monophthongs include short vowels such as /ɪ/, /ɛ/, /a/, /ɔ/, and /ʊ/, alongside long counterparts /iː/, /eː/, /aː/, /oː/, and /uː/, with realizations influenced by surrounding consonants and regional factors.[37] In particular, the long low vowel /aː/ tends toward fronting in Ulster varieties compared to the more retracted [ɑː] in Connacht and Munster dialects. A key regional divergence lies in the realization of the grapheme ⟨ea⟩, which corresponds to /a/ in West Ulster (e.g., fear [fʲaɾˠ]) but shifts to a fronter [ɛ] in East Ulster varieties (e.g., fear [fʲɛɾˠ]).[38] This contrast highlights an East-West divide, with spectrographic analyses of archival recordings, such as those from Oireachtas na Gaeilge events, revealing centralized -like formants in western speech versus raised and fronted trajectories in eastern remnants.[39] Diphthongs in Ulster Irish, including /ai/, /au/, and /əi/, generally resist the simplification patterns observed in some standard Irish norms derived from Connacht, maintaining distinct off-glides as evidenced in quantitative formant studies.[37] Substrate influences from ongoing language shift to English have contributed to vowel merger patterns in peripheral Ulster Irish communities, where distinctions like /eː/ and /ɛ/ may converge under contact pressures, though core dialectal oppositions persist in Gaeltacht areas.[3] Research from Ulster University in the 2000s, including acoustic examinations of historical vocalic shifts, underscores these variations without widespread monophthongization of diphthongs typical in anglicized varieties.[37] Such empirical data from formant measurements emphasize observable dialectal integrity amid divergence.Grammatical Structure

Morphological Elements

In Ulster Irish, initial consonant mutations—lenition (fricativization or deletion of stops and fricatives) and eclipsis (nasalization of voiceless stops and voicing of voiced stops)—function as inflectional markers triggered by syntactic contexts such as definite articles, possessive pronouns, and select prepositions.[35][40] These processes apply morphologically to word-initial consonants, altering their phonological realization without changing the lexical root, as in cailín 'girl' becoming na cailíní (eclipsis after plural article) or an chailín (lenition after singular feminine article).[41] Compared to southern dialects, Ulster varieties, particularly in Donegal Gaeltacht communities, exhibit greater regularity in mutation triggers and exceptions, with fewer analogical reductions; for instance, lenition after numerals or certain adjectives adheres more strictly to historical rules, as documented in dialect corpora from the region.[41] Noun declensions in Ulster Irish preserve archaic dative singular forms, especially in prepositional constructions denoting location or association, diverging from the nominative in stems ending in slender or broad consonants.[41] Examples include cos 'leg/foot' declining to dative cois in phrases like ar cois na sliabh 'at the foot of the mountain', or lámh 'hand' to láimh after prepositions such as i or ar.[32] These forms, retained more robustly in Ulster than in Munster dialects where syncretism with the nominative is advanced, reflect conservative inflectional paradigms; plural datives often end in -aibh or -ibh, as in na cosaibh 'to the feet'.[41] Derivational morphology employs suffixes like -ach for adjectives (e.g., feargach 'angry' from fearg 'anger') and -óir for agent nouns (e.g., leachtóir 'reader' from leá 'reading'), with Ulster-specific realizations showing palatalization consistency in stem-final position.[42] Verbal paradigms in Ulster Irish combine synthetic inflections (e.g., present tense endings like -aim, -ann, -imid) with periphrastic constructions using copula bí and preverbal particles for tense-aspect marking, such as tá ag déanamh 'is doing' (present progressive) or bhí le déanamh 'had to be done' (obligation past).[42] Independent verb forms distinguish affirmative moods via initial mutations on the verb (e.g., lenition in past habitual bhris 'used to break'), while dependent forms trigger eclipsis; periphrastic future uses beidh 'will be' with verbal nouns, as in beidh sé ag ith 'he will be eating'.[41] In Ulster corpora, these paradigms show reduced synthetic past tenses in favor of analytic do bhí equivalents, emphasizing verbal noun compounding over fused inflections observed elsewhere.[42]Syntactic Patterns

Ulster Irish adheres to the verb-subject-object (VSO) word order typical of declarative sentences in Irish Gaelic, as confirmed in syntactic analyses of dialectal data.[43] This base structure facilitates verb-initial positioning, with examples from speaker elicitations yielding forms like "Ithfidh sé an t-aran" (He will eat the bread), where the verb precedes the subject pronoun.[44] Topicalization introduces discourse-driven flexibility, allowing non-subject constituents to front for emphasis, a pattern attested in narrative recordings from Ulster speakers that mirrors broader Insular Celtic pragmatics without altering the underlying VSO frame.[44] The copula is functions distinctly from analytic verbs for equative and classificatory predications, linking nouns or predicates without tense or person inflection, as in "Is fear cráifeach é" (He is a religious man).[45] In contrast, the substantive verb bí (manifesting as tá in the present) handles stative, locative, or existential senses, inflecting for tense and agreeing with subjects, e.g., "Tá sé i dteach mór" (He is in a big house). Ulster Irish notably omits the pronominal augment (e.g., é or í) in many predicational copular constructions, diverging from southern norms and simplifying the syntax, as documented in dialectal grammars.[45] Relative clauses employ the invariant particle a (or ea in some contexts) to introduce dependent structures, followed by the verb in its relative form; Ulster dialects feature specialized synthetic endings for present habitual and future tenses, such as -eas or -íos, yielding "an fear a itheann an t-aran" (the man who eats the bread).[46] This contrasts with analytic forms in other dialects and reflects historical verb morphology preserved in northern varieties, evident in elicited data from Donegal speakers. Direct relatives trigger lenition on initial consonants, while indirect ones may use ar in past tenses, maintaining head-internal positioning without resumptive pronouns in simple cases.[46]Lexical Characteristics

Core Vocabulary and Borrowings

Ulster Irish retains a core lexicon of native terms in fundamental semantic fields, including kinship and topography, which trace back to Proto-Celtic reconstructions. Kinship vocabulary exemplifies this continuity, with terms such as athair ("father," derived from Proto-Celtic atter, itself from Proto-Indo-European *ph₂tḗr) and máthair ("mother," from Proto-Celtic mātīr, akin to Proto-Indo-European *méh₂tēr). These forms persist without significant alteration in Ulster Irish corpora, reflecting the dialect's relative conservatism compared to southern varieties, where innovation from external contacts has been more pronounced.[47][48] Topographical terms similarly preserve ancient roots, such as cnoc ("hill," from Proto-Celtic *knuxti) and sliabh ("mountain," from *slēbōn), which encode landscape features central to Ulster's rugged terrain and appear frequently in place-name derivations across the region. Analysis of dialectal texts from Donegal, the primary surviving Ulster Irish heartland, shows these native elements dominating descriptive usage, underscoring a lexical foundation resistant to wholesale replacement despite historical pressures.[49] Post-Plantation contacts introduced select borrowings from Scots into Ulster Irish, particularly in everyday domains. A notable example is craic ("fun, banter, or news," spelled craic in Irish orthography), adapted from Scots crack (conversation or gossip), which entered Ulster Irish usage around the 17th-18th centuries amid linguistic mixing in plantation zones. Such integrations remain limited, comprising under 5% of basic lexicon in sampled Ulster Irish materials, with native terms prevailing in high-frequency core usage.[50][51]Influences from English and Scots

The Plantation of Ulster, initiated in 1609, facilitated extensive language contact between Irish speakers and incoming Lowland Scots and English settlers, who constituted about 37% of Ulster's population by 1659 and contributed to a Protestant majority of roughly 62% by 1732, thereby embedding Scots and English elements into the Ulster Irish lexicon.[3] Borrowings from Lowland Scots include pegh 'to pant', sheugh 'drainage channel or ditch', bairn 'child', and ceili 'social gathering or visit', the latter adapted from Scots forms while retaining semantic ties to communal activities.[3] English loans, such as televise for television-related concepts, entered more recently, often via modern media and administration, supplementing core vocabulary in domains like technology and governance.[3] Phonetic adaptations of these loans align with Ulster Irish patterns, including palatalization or velar fricative retention/weakening, as in prough (from Scots proch 'porridge'), where /x/ may surface as or soften to in certain dialects, reflecting substrate phonology over donor-language fidelity.[3] Such integrations demonstrate causal effects of bilingualism and shift, with settlers imposing terms during economic and social interactions, rather than symmetric exchange. Code-mixing appears in historical texts from 1600–1900, where Irish-English hybrids occur in literary and personal writings, signaling pragmatic switching among L1 Irish speakers acquiring L2 English, though less evidence exists for Scots-specific mixing in Ulster Irish corpora.[52] [3] Linguistic analysis counters claims of unadulterated Gaelic continuity in Ulster Irish, as contact-induced borrowings—quantified minimally in reverse (Irish loans at 1.3–0.45% in Mid-Ulster English samples)—reveal a hybrid lexicon shaped by demographic dominance and functional needs, with Scots exerting stronger early influence due to settlers numbering at least 50% of arrivals.[3] This empirical layering, evident in dialect surveys and etymological tracing, underscores causal realism in variety formation over idealized isolation.[3]Sociolinguistic Status

Speaker Demographics and Geographic Distribution

Ulster Irish speakers are overwhelmingly concentrated in rural Gaeltacht districts of County Donegal in the Republic of Ireland, particularly in areas such as Gaoth Dobhair (Gweedore), Na Magairí (Maghery), and Cloch Cheannfhaolaidh (Cloughaneely), where it remains the traditional community language. Smaller, fragmented communities exist in border regions of Northern Ireland, including parts of counties Tyrone, Fermanagh, and Derry, though these have seen near-total attrition due to historical Anglicization and lack of intergenerational transmission. Urban centers across Ulster exhibit negligible native usage, with any Irish spoken typically reflecting learner varieties rather than the Ulster dialect.[53] The 2016 Census of Population recorded 5,929 daily speakers of Irish in the Donegal Gaeltacht, comprising the bulk of proficient Ulster Irish users; this figure declined from 6,701 in 2011, reflecting emigration and aging demographics. In the non-Gaeltacht portions of Donegal and the adjacent Ulster counties of Cavan and Monaghan, daily speakers numbered in the low hundreds, with Cavan reporting approximately 400 and Monaghan around 700 based on comparable 2016 frequency data. Proficiency metrics indicate that while many report "ability to speak," habitual or native fluency is confined to a shrinking elderly cohort, with fewer than 20% of Gaeltacht residents under 50 using the language daily outside formal settings.[53]| County (Republic of Ireland) | Daily Irish Speakers (2016, approx.) |

|---|---|

| Donegal Gaeltacht | 5,929 |

| Donegal (non-Gaeltacht) | ~1,000 |

| Cavan | ~400 |

| Monaghan | ~700 |