Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

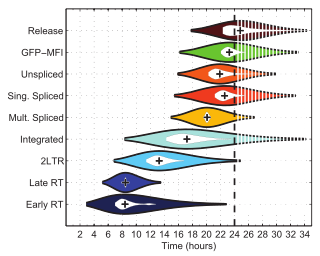

Violin plot

View on Wikipedia

A violin plot (also known as a bean plot) is a statistical graphic for comparing probability distributions. It is similar to a box plot, but has enhanced information with the addition of a rotated kernel density plot on each side.[1]

History

[edit]The violin plot was proposed in 1997 by Jerry L. Hintze and Ray D. Nelson as a way to display even more information than box plots, which were created by John Tukey in 1977.[2] The name comes from the plot's alleged resemblance to a violin.[2]

Description

[edit]Violin plots are similar to box plots, except that they also show the probability density of the data at different values, usually smoothed by a kernel density estimator. A violin plot will include all the data that is in a box plot: a marker for the median of the data; a box or marker indicating the interquartile range; and possibly all sample points, if the number of samples is not too high.

While a box plot shows a summary statistics such as mean/median and interquartile ranges, the violin plot shows the full distribution of the data. The violin plot can be used in multimodal data (more than one peak). In this case a violin plot shows the presence of different peaks, their position and relative amplitude.

Like box plots, violin plots are used to represent comparison of a variable distribution (or sample distribution) across different "categories" (for example, temperature distribution compared between day and night, or distribution of car prices compared across different car makers).

A violin plot can have multiple layers. For instance, the outer shape represents all possible results. The next layer inside might represent the values that occur 95% of the time. The next layer (if it exists) inside might represent the values that occur 50% of the time.

Violin plots are less popular than box plots. Violin plots may be harder to understand for readers not familiar with them. In this case, a more accessible alternative is to plot a series of stacked histograms or kernel density plots.

The original meaning of "violin plot" was a combination of a box plot and a two-sided kernel density plot.[1] However, currently "violin plots" are sometimes understood just as two-sided kernel density plots, without a box plot or any other elements.[3][4]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Violin Plot". NIST DataPlot. National Institute of Standards and Technology. 2015-10-13.

- ^ a b Hintze, Jerry L.; Nelson, Ray D. (May 1998). "Violin Plots: A Box Plot-Density Trace Synergism". The American Statistician. 52 (2): 181–184. doi:10.1080/00031305.1998.10480559. ISSN 0003-1305.

- ^ Wilke, Claus O. Fundamentals of Data Visualization.

- ^ "Violin plot — geom_violin". ggplot2.tidyverse.org. Retrieved 2023-11-19.

External links

[edit]- Vioplot add-in for Stata

- Violinplot from a wide-form dataset with the seaborn statistical visualization library based on matplotlib

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from Dataplot reference manual: Violin plot. National Institute of Standards and Technology.

This article incorporates public domain material from Dataplot reference manual: Violin plot. National Institute of Standards and Technology.

Violin plot

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition

A violin plot is a statistical graphic that combines the summary statistics inherent in a box plot—such as the median, quartiles, and indicators of spread and asymmetry—with the distributional shape provided by a density trace, enabling the visualization and comparison of probability distributions across categorical groups.[5] This hybrid approach pools features from alternative data representations to offer a more comprehensive view of batch data characteristics in a single display.[5] The plot earns its name from the visual resemblance to a violin, created by the symmetric, bulbous forms of the mirrored density traces extending outward from a central axis, which evoke the instrument's outline.[5] Structurally, a violin plot features a primary axis (vertical or horizontal) for the numeric variable of interest, where each data group is represented by a pair of opposing density curves that enclose an embedded box plot, thereby integrating local density information with robust summary measures.[5]Purpose

Violin plots serve as a visualization tool to display and compare the probability density of data distributions across multiple groups or categories, enabling analysts to examine the full shape of the data rather than relying solely on summary statistics like means or medians. By combining density estimation with summary measures, they reveal critical distributional features such as multimodality, skewness, asymmetry, and the presence of outliers, which provide deeper insights into the underlying data structure.[1] This approach is particularly useful for identifying subtle patterns that aggregate statistics might obscure, including multiple peaks suggestive of bimodality or elongated tails indicating heavy-tailed distributions, thereby facilitating more informed data interpretation in exploratory analysis. For instance, violin plots can highlight clusters within groups, such as distinct modes in environmental measurements like snowfall amounts or geyser eruption durations.[1] In practice, violin plots are commonly employed to compare distributions in categorical datasets, such as salary variations across academic ranks or performance metrics between experimental treatment groups, as well as for initial univariate data exploration to inform subsequent modeling decisions. Their ability to convey both density and summary information makes them valuable in fields requiring robust distributional comparisons without assuming normality.[1]History

Invention

The violin plot was proposed in 1998 by statisticians Jerry L. Hintze and Ray D. Nelson as a novel graphical method for data visualization.[1] Their seminal paper, titled "Violin Plots: A Box Plot-Density Trace Synergism," was published in The American Statistician, where they described the plot as a synergistic combination of box plot summary statistics and density traces to provide a more comprehensive representation of data distributions.[1] Hintze, affiliated with the statistical software company NCSS, and Nelson, from Brigham Young University's Marriott School of Management, first implemented the violin plot in the NCSS software package in 1997, prior to the formal publication.[1] The primary motivation for inventing the violin plot was to overcome the limitations of traditional box plots, which effectively summarize central tendency, spread, skewness, and outliers but fail to convey the underlying shape or multimodality of the data distribution.[1] By integrating kernel density estimation traces symmetrically around the box plot elements, the violin plot adds visual information about local data density, enabling users to identify clusters, gaps, and overall distributional form in a single, compact display.[1] This approach was intended to enhance exploratory data analysis by pooling the strengths of both methods without sacrificing interpretability.[1] The violin plot was explicitly developed as an enhancement to the box plot introduced by John W. Tukey in 1977, building on its foundational role in exploratory data analysis while addressing gaps in density representation.[1] Tukey's box plot, detailed in his book Exploratory Data Analysis, had become a standard tool for summarizing univariate distributions, but Hintze and Nelson sought to extend it for statistical software applications where fuller distributional insights were needed.[1]Adoption and Evolution

Following the initial proposal by Hintze and Nelson in 1998, violin plots experienced early adoption in commercial statistical software, including an implementation in NCSS prior to the paper's publication.[1] The technique gained broader accessibility in the open-source R programming language during the late 1990s and early 2000s, with integrations in environments like S-PLUS and its port to R via the lattice package, which introduced the panel.violin function around 2001. This period marked the beginning of violin plots' integration into routine statistical analysis workflows. Subsequent refinements enhanced the plot's utility, including options for layered densities that delineate inner contours (e.g., representing the central 50% of the distribution) and outer contours (e.g., the full 95% range) to better highlight probability densities and variability.[6] Horizontal orientations were also developed to improve readability, particularly for comparisons involving multiple categories or when vertical space is limited, as facilitated by functions like coord_flip() in ggplot2. These evolutions addressed limitations in the original design, making violin plots more versatile for exploratory data analysis. The ggplot2 package, released in 2007 and featuring geom_violin by version 1.0.0 in 2015, significantly accelerated adoption by providing intuitive, customizable implementations that aligned with the grammar of graphics paradigm.[7] As of 2025, violin plots are a standard tool in leading data visualization libraries, including R's ggplot2 and lattice, Python's seaborn (introduced around 2012), and MATLAB's Statistics and Machine Learning Toolbox, driven by the proliferation of open-source data science ecosystems.[4] The foundational paper has garnered over 1,600 citations, with violin plots appearing in more than 1,000 academic publications since 2010, underscoring their enduring impact in fields like bioinformatics, economics, and environmental science.[8]Components

Box Plot Elements

The box plot elements in a violin plot provide a summary of the central tendency, spread, and potential outliers in the data distribution, overlaid within the density shape for enhanced visualization. The central box spans the interquartile range (IQR), which captures the middle 50% of the data from the 25th percentile (Q1) to the 75th percentile (Q3), offering a robust measure of variability less sensitive to extreme values than the full range.[9] A horizontal line within this box marks the median, or 50th percentile, indicating the data's central value.[9] Whiskers extend vertically from the box ends to the smallest and largest data points that fall within 1.5 times the IQR below Q1 or above Q3, respectively, encompassing the bulk of the non-outlying observations and illustrating the data's overall extent without undue influence from anomalies.[9] This convention, rooted in John Tukey's exploratory data analysis framework, helps identify the typical range while flagging deviations. Data points lying beyond the whisker tips—specifically, those more than 1.5 times the IQR from Q1 or Q3—are plotted as individual markers, such as dots or circles, to highlight potential outliers that may warrant further investigation for errors or interesting patterns in the distribution.[9] These elements are symmetrically integrated into the violin plot's kernel density contours, allowing simultaneous assessment of summary statistics and distributional form.Kernel Density Elements

The kernel density elements in violin plots provide a continuous visualization of the data distribution's shape through a symmetric density trace. This trace is formed by computing a kernel density estimate (KDE) of the data and mirroring it on both sides of the central axis, creating the characteristic "violin" outline that extends equally left and right for balanced perceptual comparison.[5][9] The width of the density trace varies proportionally to the estimated probability density, with broader sections denoting higher concentrations of data points and narrower sections indicating lower densities. This design reveals multimodal structures, skewness, and overall form without the jagged edges or arbitrary binning associated with histograms, offering a smoother and more intuitive depiction of the underlying probability distribution.[5][9] Optionally, the region enclosed by the density trace can be shaded to fill the violin area, enhancing visibility of the density profile, while inner shaded regions may highlight targeted portions of the distribution to differentiate core densities from peripheral tails.[4]Construction

Kernel Density Estimation

Kernel density estimation (KDE) forms the core of the density component in violin plots, providing a smoothed representation of the underlying probability distribution of a dataset. This non-parametric technique estimates the probability density function from a finite set of observations without assuming a specific parametric form, allowing violin plots to visualize multimodal distributions and density variations effectively.[10] The KDE is mathematically defined as where is the number of data points , is the bandwidth parameter controlling the smoothness, and is a kernel function—a symmetric, non-negative function integrating to 1 that weights contributions from each data point based on its distance from . This formula aggregates local contributions from all observations, scaled by the bandwidth, to produce a continuous density estimate suitable for rendering the curved sides of a violin plot.[10] A common choice for the kernel is the Gaussian kernel, which yields a smooth, bell-shaped weighting that is symmetric and computationally efficient for violin plot generation; alternatively, the Epanechnikov kernel, for and 0 otherwise, is used for its optimal mean integrated squared error properties and compactness, promoting symmetry and efficiency in the resulting plot shape. These kernels are preferred in violin plot implementations due to their ability to produce mirrored, aesthetically balanced densities without boundary issues in typical univariate applications. Bandwidth selection is crucial in KDE, as it trades off bias and variance: a small leads to undersmoothing with high variance and spurious peaks, while a large causes oversmoothing and loss of distributional detail. A widely adopted method is Silverman's rule of thumb for Gaussian kernels, where is the sample standard deviation and IQR is the interquartile range; this heuristic provides a reasonable starting point by approximating the optimal bandwidth under normality assumptions, though cross-validation methods like least-squares or likelihood-based selection are often employed for more robust adaptation to the data's shape in violin plot contexts.Plot Assembly

The assembly of a violin plot begins with computing a kernel density estimation (KDE) for the data within each categorical group, providing a smooth estimate of the underlying probability distribution. This density function is then mirrored symmetrically across a central axis and scaled such that the horizontal width at any point along the vertical (or horizontal) axis is proportional to the estimated density value, creating the characteristic bulbous, violin-like outline.[9] Next, traditional box plot elements are overlaid along the central axis of the density shape: a horizontal line marks the median, a box spans the interquartile range (IQR), and whiskers extend to the minimum and maximum values within 1.5 times the IQR, with any outliers optionally shown as points. For multi-group comparisons, the resulting violin shapes are positioned side-by-side along a categorical axis, enabling visual assessment of distributional differences across groups.[9] Violin plots are most commonly oriented vertically, with the density varying along a continuous y-axis for intuitive reading of value scales, though horizontal orientations are used when category labels are numerous or lengthy to improve readability.[11] Customizations often include adjusting fill transparency to handle overlaps in dense displays, assigning distinct colors to each group's violin for differentiation, and incorporating rug marks—small, jittered ticks along the central axis—to hint at the raw data points without cluttering the plot.[11]Comparisons

With Box Plots

Traditional box plots, introduced by John Tukey in 1977, summarize a dataset using five key numbers: the minimum, first quartile (Q1), median, third quartile (Q3), and maximum (often adjusted for outliers), along with whiskers extending to the data range. These elements effectively convey the center, spread, skewness, and presence of outliers but fail to reveal the underlying distribution shape, such as multimodality, uniformity, or clustering, leading to indistinguishable appearances for distributions with similar summary statistics but different forms.[5] Additionally, box plots do not indicate sample size, making small and large samples appear equally reliable in visual comparisons.[12] Violin plots address these limitations by integrating the standard box plot components within a symmetric kernel density envelope, which visually traces the probability density of the data on both sides of the central box.[5] This addition preserves the robustness of the box plot's summary statistics while enabling inference about the distribution's shape, peaks, and valleys, thus distinguishing multimodal or asymmetric patterns that box plots obscure.[5] Box plots are preferable for quick overviews of large datasets where computational efficiency and simplicity are prioritized, as they require no density estimation.[5] In contrast, violin plots are better suited for detailed exploratory analysis, particularly with sample sizes of 30 or more, when understanding the full distributional form is essential for interpretation.[5]With Histograms and Kernel Density Plots

Violin plots offer a hybrid visualization that addresses key limitations of histograms by employing kernel density estimation (KDE) to represent data distributions smoothly without the need for binning.[13] Histograms discretize continuous data into fixed-width bins, displaying frequency counts as bar heights, which can introduce artifacts such as artificial peaks or valleys depending on the chosen bin width and starting point; for instance, a narrow bin width may overemphasize noise, while a wide one may obscure multimodality.[14] In contrast, violin plots generate mirrored KDE curves that approximate the underlying probability density function, providing a continuous and flexible depiction of the data's shape, skewness, and density concentrations, thereby avoiding these binning sensitivities.[15] This approach, originally synergizing density traces with box plot elements, enables a more faithful rendering of distribution nuances, particularly useful for comparative analyses across groups. Standalone kernel density plots, while also eschewing binning for smooth density curves, focus solely on the estimated probability density without incorporating summary statistics, limiting their utility for quick assessments of central tendency or spread.[13] Violin plots augment these density visualizations by overlaying box plot components—such as medians, quartiles, and interquartile ranges—directly within the symmetric "violin" shape, allowing viewers to discern both the full distributional form and robust statistical summaries in a single, compact figure.[14] For example, the white dot marking the median and the thick bar indicating the interquartile range in a typical violin plot provide immediate insights into outliers and variability that a pure KDE curve omits, enhancing interpretability without requiring separate plots.[15] Despite these strengths, violin plots involve trade-offs when juxtaposed with histograms and standalone KDEs, particularly in scenarios demanding precise counts or unadorned smoothness. Histograms excel at conveying exact frequencies and are less prone to over-smoothing with small datasets, making them preferable for applications where raw bin counts establish critical context, such as quality control metrics.[13] KDE plots, by prioritizing unimodal or multimodal smoothness, offer clarity in density trends without the visual clutter of overlaid statistics, though they may mislead on sample size or exact probabilities.[14] Violin plots, while compact and effective for side-by-side group comparisons in exploratory settings, can suffer from overlapping curves in dense displays or bandwidth-induced distortions if the smoothing parameter is not tuned appropriately, potentially complicating readability compared to the straightforward bars of histograms.[15]Advantages and Limitations

Advantages

Violin plots provide a comprehensive view of data distributions by integrating summary statistics—such as medians, quartiles, and potential outliers from an embedded box plot—with a mirrored kernel density estimate that reveals the full shape and probability density of the data.[1][16] This dual representation enables viewers to assess central tendency and spread alongside nuanced details like local concentrations and gaps, offering a more informative alternative to box plots alone, which summarize but do not depict the underlying density.[1][17] They are particularly advantageous for multimodal or skewed datasets, where the violin's varying widths highlight multiple peaks indicating distinct subpopulations or asymmetric tails reflecting non-normal behavior, features that standard box plots cannot convey.[1][17][16] By visualizing these characteristics, violin plots enhance exploratory data analysis, allowing researchers to detect and interpret complex distributional patterns that might otherwise require separate density plots.[16] The density-based widths also aid interpretability by proportionally indicating the relative frequency of data points across the range, with broader sections denoting higher probability densities and aiding in the assessment of data concentration without needing additional annotations.[1][17] In addition, violin plots support efficient comparisons of multiple groups in a compact format, positioning symmetric density traces side-by-side to juxtapose shapes, spreads, and tendencies while occupying minimal space compared to aligned histograms or separate density plots.[1][16] This arrangement is especially useful in studies involving categorical factors, where visual alignment facilitates quick identification of distributional differences across categories.[16]Limitations

Violin plots can present interpretation challenges, particularly with small sample sizes, where the kernel density estimation (KDE) may lead to over-smoothing that misrepresents the true distribution shape. For instance, with fewer than 30 observations, the density trace often fails to accurately capture underlying features, resulting in misleading visual impressions of uniformity or multimodality.[5] Additionally, when comparing non-overlapping groups, the symmetric density shapes may obscure subtle differences in spread or location, complicating direct visual assessment.[18] The choice of bandwidth parameter in KDE is highly sensitive and can significantly alter the plot's appearance, often obscuring true multimodality if poorly selected. An overly narrow bandwidth produces wiggly traces that introduce artifactual features, while an excessively wide one results in over-smoothed curves that mask important distributional details, such as peaks or tails.[5] This requires considerable experience to determine an appropriate value, typically around 15-40% of the data range, and suboptimal choices are common without careful tuning.[18] Compared to box plots, violin plots are less intuitive for audiences unfamiliar with KDE, as they emphasize estimated densities rather than direct summary statistics like precise quartiles or medians. This reliance on smoothed representations demands prior knowledge to interpret correctly, making them unsuitable for quick overviews or presentations where exact quantiles are needed for decision-making.[18] Furthermore, the visual comparison of multiple violin plots side-by-side can be difficult due to varying density heights, which may not reflect sample sizes accurately if normalized.[5]Applications

In Exploratory Data Analysis

Violin plots serve a crucial function in exploratory data analysis (EDA) by enabling the initial inspection of univariate and grouped data distributions to reveal underlying patterns. During this phase, they facilitate the assessment of normality by displaying the symmetry, modality, and overall shape of the density trace, which can indicate deviations such as skewness or bimodality that suggest non-normal data. The embedded box plot elements within the violin further aid in identifying outliers as points beyond the whisker ranges, while the side-by-side arrangement of violins allows for straightforward visual comparison of distributions across groups, highlighting differences in spread, central tendency, or density peaks before advancing to hypothesis testing.[1][1] In broader EDA workflows, particularly for preparing data for parametric models like regression or ANOVA, violin plots are frequently integrated with complementary visualizations such as scatterplots to explore bivariate relationships and quantile-quantile (QQ) plots to rigorously validate normality assumptions for variables or residuals. This combination provides a multifaceted view: the violin plot offers an intuitive sense of distribution shape and group variability, while QQ plots confirm alignment with theoretical distributions through quantile comparisons, ensuring assumptions are met prior to modeling.[19] Best practices for employing violin plots in EDA emphasize their application to continuous variables where each group contains more than 30 observations, as smaller sample sizes can lead to unreliable kernel density estimates due to oversmoothing or instability in the trace. With adequate sample sizes, the density component stabilizes, providing trustworthy insights into data structure without excessive computational demands.[1]In Scientific and Industry Contexts

In biology and medicine, violin plots are widely employed to compare gene expression levels across experimental conditions in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data, facilitating the identification of bimodal populations that indicate cellular heterogeneity or distinct subpopulations. Similarly, in studies of neurodevelopmental conditions like trisomy 21, violin plots have revealed bimodal expression distributions for genes such as EFNA5 and TRPM3 in neural progenitor cells, highlighting increased variability associated with phenotypic diversity compared to euploid controls.[20][21][22] In the social sciences, violin plots are utilized to analyze survey responses on variables like income distributions by demographic groups, emphasizing clusters or inequalities within populations. These visualizations highlight multimodal patterns in self-reported data, such as variations in household income across categories of perceived economic well-being, which can underscore disparities linked to socioeconomic factors. For instance, in studies of adolescents' mental health, violin plots overlayed on boxplots have shown how income levels correlate with subjective economic perceptions, aiding in the detection of distributional shifts that reflect broader societal inequalities.[23]Implementation

Software Support

Violin plots are supported in various statistical and data visualization software, enabling users to generate these plots with options for customization such as bandwidth adjustment and kernel selection.[3] In the R programming language, the ggplot2 package provides thegeom_violin() function, which creates violin plots by combining mirrored kernel density estimates with box plot elements, allowing customization of parameters like kernel type (e.g., Gaussian, Epanechnikov), bandwidth via bw_adjust, and scaling methods (e.g., area, width, or count).[3] Additionally, the dedicated vioplot package offers functions for producing violin plots with enhanced annotation, color customization per group, and support for grouped data, building on base R graphics for flexible density estimation and trimming options.[24]

For Python, the seaborn library includes the violinplot() function, which simplifies the creation of violin plots by integrating kernel density estimation with categorical grouping, and it seamlessly works with pandas DataFrames for data preparation and manipulation prior to plotting.[4] The underlying matplotlib library supports violin plots through violinplot(), providing lower-level control over aspects like the number of points, show means or extremes, and body and whisker widths, often used in conjunction with seaborn for enhanced styling.[25]

Beyond R and Python, violin plots can be implemented in web-based environments using the JavaScript library D3.js, which allows for interactive, SVG-based violin charts through custom density calculations and path generation for the plot shapes.[26] In Microsoft Excel, add-ins like XLSTAT enable direct creation of violin plots with options to overlay box plots or dot plots and trim tails to the data range, addressing the lack of native support.[27] Tableau supports violin plots via calculated fields for kernel density estimation and data scaffolding, facilitating interactive dashboards without requiring external scripting.[28] As of 2025, AI tools such as ChatGPT, using code generation features or custom GPTs, allow users to produce violin plots by prompting for scripts in Python or R, streamlining the process for non-programmers.[29]

Practical Example

A practical example of a violin plot can be constructed using the Iris flower dataset, which records measurements of sepal length for 150 samples across three species: Iris setosa, Iris versicolor, and Iris virginica. This dataset illustrates how violin plots reveal distributional differences, with setosa exhibiting a distinct, unimodal density separated from the overlapping distributions of versicolor and virginica. In R, using the ggplot2 package, a violin plot can be generated with the following code snippet, which maps species to the x-axis and sepal length to the y-axis, overlaying a narrow box plot to highlight medians:library([ggplot2](/page/Ggplot2))

ggplot(iris, aes(x = Species, y = Sepal.Length)) +

geom_violin(trim = FALSE) +

geom_boxplot(width = 0.1, outlier.shape = [NA](/page/N/A)) +

theme_minimal()

library([ggplot2](/page/Ggplot2))

ggplot(iris, aes(x = Species, y = Sepal.Length)) +

geom_violin(trim = FALSE) +

geom_boxplot(width = 0.1, outlier.shape = [NA](/page/N/A)) +

theme_minimal()