Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Survival function

View on WikipediaThe survival function is a function that gives the probability that a patient, device, or other object of interest will survive past a certain time.[1] The survival function is also known as the survivor function[2] or reliability function.[3] The term reliability function is common in engineering while the term survival function is used in a broader range of applications, including human mortality. The survival function is the complementary cumulative distribution function of the lifetime. Sometimes complementary cumulative distribution functions are called survival functions in general.

Definition

[edit]Let the lifetime be a continuous random variable describing the time to failure. If has cumulative distribution function and probability density function on the interval , then the survival function or reliability function is:

Examples of survival functions

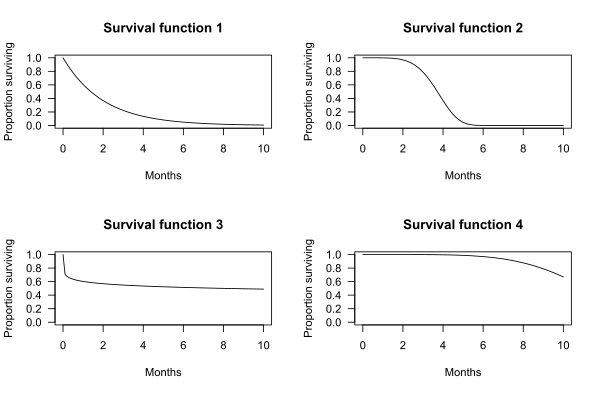

[edit]The graphs below show examples of hypothetical survival functions. The x-axis is time. The y-axis is the proportion of subjects surviving. The graphs show the probability that a subject will survive beyond time t.

For example, for survival function 1, the probability of surviving longer than t = 2 months is 0.37. That is, 37% of subjects survive more than 2 months.

For survival function 2, the probability of surviving longer than t = 2 months is 0.97. That is, 97% of subjects survive more than 2 months.

Median survival may be determined from the survival function: The median survival is the point where the survival function intersects the value 0.5.[4] For example, for survival function 2, 50% of the subjects survive 3.72 months. Median survival is thus 3.72 months.

Median survival cannot always be determined from the graph alone. For example, in survival function 4, more than 50% of the subjects survive longer than the observation period of 10 months.

The survival function is one of several ways to describe and display survival data. Another useful way to display data is a graph showing the distribution of survival times of subjects. Olkin,[5] page 426, gives the following example of survival data. The number of hours between successive failures of an air-conditioning (AC) system were recorded. The time in hours, t, between successive failures are 1, 3, 5, 7, 11, 11, 11, 12, 14, 14, 14, 16, 16, 20, 21, 23, 42, 47, 52, 62, 71, 71, 87, 90, 95, 120, 120, 225, 246 and 261. The mean time between failures is 59.6. The figure below shows the distribution of the time between failures. The blue tick marks beneath the graph are the actual hours between successive AC failures.

In this example, a curve representing the exponential distribution overlays the distribution of AC failure times; the exponential distribution approximates the distribution of AC failure times. This particular exponential curve is specified by the parameter lambda, λ:

The distribution of failure times is the probability density function (PDF), since time can take any positive value. In equations, the PDF is specified as fT. If time can only take discrete values (such as 1 day, 2 days, and so on), the distribution of failure times is called the probability mass function. Most survival analysis methods assume that time can take any positive value, and fT is the PDF. If the time between observed AC failures is approximated using the exponential function, then the exponential curve gives the probability density function, fT, for AC failure times.

Another useful way to display the survival data is a graph showing the cumulative failures up to each time point. These data may be displayed as either the cumulative number or the cumulative proportion of failures up to each time. The graph below shows the cumulative probability (or proportion) of failures at each time for the air conditioning system. The stairstep line in black shows the cumulative proportion of failures. For each step there is a blue tick at the bottom of the graph indicating an observed failure time. The smooth red line represents the exponential curve fitted to the observed data.

A graph of the cumulative probability of failures up to each time point is called the cumulative distribution function (CDF). In survival analysis, the cumulative distribution function gives the probability that the survival time is less than or equal to a specific time, t.

Let T be survival time, which is any positive number. A particular time is designated by the lower case letter t. The cumulative distribution function of T is the function

where the right-hand side represents the probability that the random variable T is less than or equal to t. If time can take on any positive value, then the cumulative distribution function F(t) is the integral of the probability density function f(t).

For the air-conditioning example, the graph of the CDF below illustrates that the probability that the time to failure is less than or equal to 100 hours is 0.81, as estimated using the exponential curve fit to the data.

An alternative to graphing the probability that the failure time is less than or equal to 100 hours is to graph the probability that the failure time is greater than 100 hours. The probability that the failure time is greater than 100 hours must be 1 minus the probability that the failure time is less than or equal to 100 hours, because total probability must sum to 1.

This gives:

This relationship generalizes to all failure times:

This relationship is shown on the graphs below. The graph on the left is the cumulative distribution function, which is Pr(T ≤ t). The graph on the right is Pr(T > t) = 1 − Pr(T ≤ t). The graph on the right is the survival function, S(t). The fact that the S(t) = 1 – CDF is the reason that another name for the survival function is the complementary cumulative distribution function.

Parametric survival functions

[edit]In some cases, such as the air conditioner example, the distribution of survival times may be approximated well by a function such as the exponential distribution. Several distributions are commonly used in survival analysis, including the exponential, Weibull, gamma, normal, log-normal, and log-logistic.[3][6] These distributions are defined by parameters. The normal (Gaussian) distribution, for example, is defined by the two parameters mean and standard deviation. Survival functions that are defined by parameters are said to be parametric.

In the four survival function graphs shown above, the shape of the survival function is defined by a particular probability distribution: survival function 1 is defined by an exponential distribution, 2 is defined by a Weibull distribution, 3 is defined by a log-logistic distribution, and 4 is defined by another Weibull distribution.

Exponential survival function

[edit]For an exponential survival distribution, the probability of failure is the same in every time interval, no matter the age of the individual or device. This fact leads to the "memoryless" property of the exponential survival distribution: the age of a subject has no effect on the probability of failure in the next time interval. The exponential may be a good model for the lifetime of a system where parts are replaced as they fail.[7] It may also be useful for modeling survival of living organisms over short intervals. It is not likely to be a good model of the complete lifespan of a living organism.[8] As Efron and Hastie [9] (p. 134) note, "If human lifetimes were exponential there wouldn't be old or young people, just lucky or unlucky ones".

Weibull survival function

[edit]A key assumption of the exponential survival function is that the hazard rate is constant. In an example given above, the proportion of men dying each year was constant at 10%, meaning that the hazard rate was constant. The assumption of constant hazard may not be appropriate. For example, among most living organisms, the risk of death is greater in old age than in middle age – that is, the hazard rate increases with time. For some diseases, such as breast cancer, the risk of recurrence is lower after 5 years – that is, the hazard rate decreases with time. The Weibull distribution extends the exponential distribution to allow constant, increasing, or decreasing hazard rates.

Other parametric survival functions

[edit]There are several other parametric survival functions that may provide a better fit to a particular data set, including normal, lognormal, log-logistic, and gamma. The choice of parametric distribution for a particular application can be made using graphical methods or using formal tests of fit. These distributions and tests are described in textbooks on survival analysis.[1][3] Lawless[10] has extensive coverage of parametric models.

Parametric survival functions are commonly used in manufacturing applications, in part because they enable estimation of the survival function beyond the observation period. However, appropriate use of parametric functions requires that data are well modeled by the chosen distribution. If an appropriate distribution is not available, or cannot be specified before a clinical trial or experiment, then non-parametric survival functions offer a useful alternative.

Non-parametric survival functions

[edit]A parametric model of survival may not be possible or desirable. In these situations, the most common method to model the survival function is the non-parametric Kaplan–Meier estimator. This estimator requires lifetime data. Periodic case (cohort) and death (and recovery) counts are statistically sufficient to make non-parametric maximum likelihood and least squares estimates of survival functions, without lifetime data.

Properties

[edit]- Every survival function is monotonically decreasing, i.e. for all .

- It is a property of a random variable that maps a set of events, usually associated with mortality or failure of some system, onto time.

- The time, , represents some origin, typically the beginning of a study or the start of operation of some system. is commonly unity but can be less to represent the probability that the system fails immediately upon operation.

- Since the CDF is a right-continuous function, the survival function is also right-continuous.

- The survival function can be related to the probability density function and the hazard function

So that

- The expected survival time

Proof of expected survival time formula

|

|---|

| The expected value of a random variable is defined as:

where is the probability density function. Using the relation , the expected value formula may be modified:

This may be further simplified by employing integration by parts:

By definition, , meaning that the boundary terms are identically equal to zero. Therefore, we may conclude that the expected value is simply the integral of the survival function:

|

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Kleinbaum, David G.; Klein, Mitchel (2012), Survival analysis: A Self-learning text (Third ed.), Springer, ISBN 978-1441966452

- ^ Tableman, Mara; Kim, Jong Sung (2003), Survival Analysis Using S (First ed.), Chapman and Hall/CRC, ISBN 978-1584884088

- ^ a b c Ebeling, Charles (2010), An Introduction to Reliability and Maintainability Engineering (Second ed.), Waveland Press, ISBN 978-1577666257

- ^ Machin, D., Cheung, Y. B., Parmar, M. (2006). Survival Analysis: A Practical Approach. Deutschland: Wiley. Page 36 and following Google Books

- ^ Olkin, Ingram; Gleser, Leon; Derman, Cyrus (1994), Probability Models and Applications (Second ed.), Macmillan, ISBN 0-02-389220-X

- ^ Klein, John; Moeschberger, Melvin (2005), Survival Analysis: Techniques for Censored and Truncated Data (Second ed.), Springer, ISBN 978-0387953991

- ^ Mendenhall, William; Terry, Sincich (2007), Statistics for Engineering and the Sciences (Fifth ed.), Pearson / Prentice Hall, ISBN 978-0131877061

- ^ Brostrom, Göran (2012), Event History Analysis with R (First ed.), Chapman & Hall/CRC, ISBN 978-1439831649

- ^ Efron, Bradley; Hastie, Trevor (2016), Computer Age Statistical Inference: Algorithms, Evidence, and Data Science (First ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1107149892

- ^ Lawless, Jerald (2002), Statistical Models and Methods for Lifetime Data (Second ed.), Wiley, ISBN 978-0471372158

Survival function

View on GrokipediaBasic Concepts

Definition

In survival analysis, the survival function describes the probability distribution of a non-negative random variable , which represents the time until the occurrence of a specified event, such as death, failure, or disease onset.[1] The survival function, denoted , is mathematically defined as for , where denotes probability.[1] This function quantifies the probability that the event has not yet occurred by time .[8] For proper probability distributions of , the survival function satisfies the boundary conditions and .[1] It is the complement of the cumulative distribution function , so .[1] The form of depends on whether is continuous or discrete: in the continuous case, is a right-continuous, non-increasing function approaching zero asymptotically; in the discrete case, it is a step function with jumps at the possible event times.[9]Relation to Other Probability Functions

The survival function is directly related to the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the random variable , representing the time until an event occurs, through the equation .[1] This relationship holds for both discrete and continuous distributions, ensuring that the survival probability complements the probability of the event having occurred by time .[1] For continuous random variables , the survival function connects to the probability density function (PDF) , which describes the distribution of event times. Specifically, , as the density at equals the negative rate of change of the survival probability.[1] This derivative relationship arises because a decrease in corresponds to the instantaneous probability of the event occurring at .[1] The hazard function , also known as the failure rate or force of mortality, provides the instantaneous rate of occurrence of the event given survival up to time , defined as .[1] To derive this, consider the conditional probability: the hazard is the limit , which approximates the probability of the event in a small interval divided by the interval length, conditional on survival to .[1] Substituting the PDF and survival function yields . Alternatively, using the logarithmic derivative, , because , confirming the equivalence and emphasizing the hazard as the rate of exponential decay in survival.[1] In engineering and reliability theory, the survival function is equivalently termed the reliability function , denoting the probability that a system or component functions without failure beyond time .[10] This interpretation bridges survival analysis with reliability engineering, where models the dependability of mechanical or electronic systems under stress or usage.[11]Examples and Applications

Illustrative Examples

To illustrate the survival function in a continuous setting, consider a random variable following a uniform distribution on the interval , where . The survival function is with for and for .[12] This form demonstrates a linear decline in the probability of surviving beyond time , reflecting constant hazard over the support. For example, if , then , indicating that the probability of survival past halfway through the interval is exactly half.[12] Graphically, appears as a straight line decreasing monotonically from to , highlighting the function's non-increasing property from certainty of survival at to impossibility beyond the maximum lifetime. In discrete time, the geometric distribution offers a simple example, where represents the number of periods until the first event occurs in a sequence of independent Bernoulli trials, each with success (event) probability where . The survival function is representing the probability of no event in the first periods.[13] This exhibits exponential decay in discrete steps, with survival probability halving (or more) as increases depending on . For instance, if , then , showing about 59% chance of surviving the first five periods.[13] Graphically, forms a step function, constant between integers and dropping abruptly at each , decreasing from toward 0 as , which underscores the right-continuous and non-increasing behavior required of survival functions. The geometric distribution serves as the discrete analogue to the exponential distribution in continuous survival analysis, both characterized by the memoryless property.[4]Practical Applications

In medicine, survival functions are widely applied to estimate patient survival probabilities following treatments, particularly in oncology where 5-year survival rates provide critical prognostic information for clinical decision-making and patient counseling.[14] For instance, these functions help quantify the likelihood of disease-free survival after interventions like chemotherapy or surgery, enabling comparisons across patient cohorts and informing public health strategies. Empirical survival curves, such as those derived from the Kaplan-Meier estimator, are routinely used to visualize these probabilities in clinical trials.[15] In engineering reliability, survival functions predict the time-to-failure for components, aiding in the design and maintenance of systems to minimize downtime and costs.[16] For example, they assess the probability that items like light bulbs or industrial machines will operate without failure beyond a specified duration, supporting warranty predictions and preventive replacement schedules.[17] This interpretive framework allows engineers to evaluate system robustness under varying operational stresses.[18] Actuarial science employs survival functions in constructing life tables, which underpin insurance premium calculations by estimating future mortality risks.[19] These functions determine the probability of survival to various ages, enabling actuaries to price life insurance policies and annuities accurately while accounting for demographic trends.[20] Such applications ensure financial products remain viable amid uncertainties in lifespan distributions.[21] Right-censoring poses challenges in these applications by introducing incomplete observations, such as when study participants drop out before an event occurs, potentially biasing survival probability estimates if not properly addressed.[8] This issue is common in longitudinal medical studies or reliability tests where follow-up ends prematurely, requiring careful interpretation to maintain accuracy.[22]Parametric Survival Functions

Exponential Survival Function

The exponential survival function arises from the exponential distribution, a parametric model commonly used in survival analysis to describe lifetimes or durations where the hazard rate remains constant over time. It assumes that the probability of an event occurring in the next instant does not depend on how much time has already passed, making it suitable for modeling processes without aging or wear-out effects.[1] The survival function for the exponential distribution is given bywhere is the time and is the constant rate parameter representing the instantaneous hazard.[1] This formula implies that the probability of surviving beyond time decreases exponentially with .[1] A defining characteristic of the exponential distribution is its memoryless property, which states that the conditional probability of surviving an additional time given survival up to time equals the unconditional probability of surviving time :

for all .[1] To prove this via conditional probability, note that

demonstrating independence from prior survival time.[23] This property uniquely identifies the exponential among continuous distributions with positive support.[1] The corresponding hazard function is constant:

indicating a uniform risk of failure at any point, with no increase or decrease due to aging.[1] For parameter estimation with uncensored data consisting of observed failure times , the maximum likelihood estimator of is

which is the reciprocal of the sample mean lifetime and maximizes the likelihood function .[24] This estimator provides an efficient point estimate under the exponential assumption.[24] The exponential model serves as a foundational case, generalized by distributions like the Weibull for time-varying hazards.[1]

Weibull Survival Function

The Weibull survival function is a parametric form widely used in survival analysis due to its flexibility in modeling diverse failure time behaviors. It is defined aswhere , is the scale parameter representing the characteristic life, and is the shape parameter that governs the form of the distribution.[25] This two-parameter model arises from extreme value theory and is particularly suited for analyzing time-to-failure data in engineering and medical contexts.[26] The corresponding hazard function for the Weibull distribution is

which allows it to capture a range of hazard shapes depending on . When , the hazard increases with time, reflecting wear-out processes; when , it decreases, indicating early failures like infant mortality; and when , the hazard is constant, simplifying to the exponential case.[25] This versatility makes the Weibull distribution a cornerstone for modeling non-constant hazards in survival data.[1] In reliability engineering, the Weibull distribution is widely used to model the phases of bathtub-shaped failure rate curves, which characterize the three phases of product life—a decreasing hazard () for infant mortality or initial defects, a constant hazard () during useful life, and an increasing hazard () due to wear-out—often in combination to describe the full curve.[26][27] Specifically, values of model the wear-out phase, where material degradation leads to accelerating failures, as seen in components like capacitors or mechanical systems. For instance, in accelerated life testing, Weibull parameters are estimated to predict long-term reliability under normal conditions.[28] The model reduces to the exponential survival function when , highlighting its generalization of memoryless processes.[1]

Other Parametric Survival Functions

The log-normal survival function models lifetimes where the logarithm of the survival time follows a normal distribution, making it suitable for processes involving multiplicative effects, such as biological growth or degradation over time. Its survival function is given by where is the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution, is the mean of the log-lifetimes, and is the standard deviation. This distribution is particularly common in biological applications, including the analysis of survival times in clinical studies like hemodialysis outcomes, where data exhibit right-skewness and heavy tails reflective of variable physiological responses.[29] The Gompertz survival function is widely used to describe age-related mortality, capturing the exponential increase in hazard rates observed in aging populations across species. It is expressed as where represents the initial mortality rate and governs the rate of exponential increase in mortality. This model has been foundational in gerontology for quantifying aging processes, as it aligns with empirical observations of accelerating death rates in adult lifespans, distinguishing it from more flexible shapes like those in the Weibull distribution.[30] Other parametric families, such as the log-logistic, extend modeling capabilities to scenarios with non-monotonic hazards. The log-logistic distribution accommodates unimodal hazard shapes, rising to a peak before declining, which is useful for failure times in reliability or medical contexts where risks initially increase and then wane.[31]| Distribution | Hazard Shape Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Log-normal | Unimodal, typically increasing to a maximum then decreasing; heavy-tailed, suitable for skewed biological data.[32] |

| Gompertz | Strictly increasing and convex (exponential growth); ideal for monotonically accelerating mortality in aging.[32] |

| Log-logistic | Flexible: monotone increasing/decreasing or unimodal (inverted-U); supports bathtub-like patterns in later tails.[32] |

![{\displaystyle S(t)=\exp \left[-\int _{0}^{t}\lambda (t')\,dt'\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fe310df3797c1d0f6c1909f54c028357b90fd0bd)