Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Warren Commission

View on Wikipedia

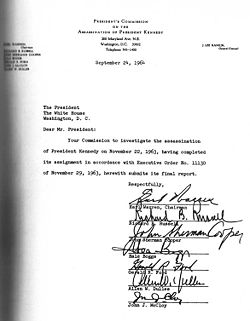

| The President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy | |

| |

Cover of final report | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Established by | Lyndon B. Johnson on November 29, 1963 |

| Disbanded | 1964 |

| Related Executive Order number(s) | 11130 |

| Membership | |

| Chairperson | Earl Warren |

| Other committee members | Richard Russell Jr., John Sherman Cooper, Hale Boggs, Gerald Ford, Allen Dulles, John J. McCloy |

The President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy, known unofficially as the Warren Commission, was established by President Lyndon B. Johnson through Executive Order 11130 on November 29, 1963,[1] to investigate the assassination of United States President John F. Kennedy that had taken place on November 22, 1963.[2]

The U.S. Congress passed Senate Joint Resolution 137 authorizing the Presidential appointed Commission to report on the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, mandating the attendance and testimony of witnesses and the production of evidence.[3] Its 888-page final report was presented to President Johnson on September 24, 1964,[4] and made public three days later.[5]

It concluded that President Kennedy was assassinated by Lee Harvey Oswald and that Oswald acted entirely alone.[6] It also concluded that Jack Ruby acted alone when he killed Oswald two days later.[7] The Commission's findings have proven controversial and have been both challenged and supported by later studies.

The Commission took its unofficial name—the Warren Commission—from its chairman, Chief Justice Earl Warren.[8] According to published transcripts of Johnson's presidential phone conversations, some major officials were opposed to forming such a commission and several commission members took part only reluctantly. One of their chief reservations was that a commission would ultimately create more controversy than consensus.[9]

Formation

[edit]The creation of the Warren Commission was a direct consequence of the murder by Jack Ruby of the assassin Lee Harvey Oswald on November 24, 1963, carried live on national television in the basement of the Dallas police station. The lack of a public process addressing the mistakes of the Dallas Police, who concluded that the case was closed, created doubt in the mind of the public.[10]

The new president, Lyndon B. Johnson, himself from Texas, the state where the two assassinations had taken place, found himself faced with the risk of a weakening of his presidency. Confronted with the results obtained by the Texas authorities, themselves seriously discredited and criticized, he decided after various consultations, including in particular that with FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, to create a presidential commission of inquiry by Executive Order 11130 of November 29, 1963. This act made it possible both to avoid an independent investigation led by Congress and to avoid entrusting the case to the Attorney General, Robert F. Kennedy, deeply affected by the assassination, whose federal jurisdiction would have been applied in the event of withdrawal of the share of the State of Texas for the benefit of the federal authorities in Washington.[10]

Nicholas Katzenbach, Deputy Attorney General, provided advice that led to the creation of the Warren Commission.[11] On November 25 he sent a memo to Johnson's White House aide Bill Moyers recommending the formation of a Presidential Commission to investigate the assassination.[11][12] To combat speculation of a conspiracy, Katzenbach said that the results of the FBI's investigation should be made public.[11][12] He wrote: "The public must be satisfied that Oswald was the assassin; that he did not have confederates who are still at large."[12]

Four days after Katzenbach's memo, Johnson appointed to the commission some of the nation's most prominent figures, including Earl Warren, Chief Justice of the United States.[11][12] At first, Warren refused to head of the commission because he stated the principle of law that a member of the judicial power could not be at the service of the executive power. It was only under pressure from President Lyndon Johnson, who spoke of international tensions and the risks of war resulting from the death of his predecessor, that he agreed to chair the commission.[10] The other members of the commission were chosen from among the representatives of the Republican and Democratic parties, in both houses of Congress, and added diplomat John J. McCloy, former president of the World Bank, and former CIA director Allen Dulles.[10]

The national image of the United States was also of concern. McCloy states that a motive of the commission was to "show the world that America is not a banana republic, where a government can be changed by conspiracy".[13] Warren shared this concern, and in part agreed to head the commission after President Johnson made it clear to him that the "nation's prestige" was at stake.[14]

Meetings

[edit]The Warren Commission met formally for the first time on December 5, 1963, on the second floor of the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C.[15] The Commission conducted its business primarily in closed sessions, but these were not secret sessions.

Two misconceptions about the Warren Commission hearing need to be clarified...hearings were closed to the public unless the witness appearing before the Commission requested an open hearing. No witness except one...requested an open hearing... Second, although the hearings (except one) were conducted in private, they were not secret. In a secret hearing, the witness is instructed not to disclose his testimony to any third party, and the hearing testimony is not published for public consumption. The witnesses who appeared before the Commission were free to repeat what they said to anyone they pleased, and all of their testimony was subsequently published in the first fifteen volumes put out by the Warren Commission.[16]

According to a 1963 FBI memo that was released to the public in 2008, Commission member Gerald Ford was in contact with the FBI throughout his time on the Warren Commission and relayed information to the deputy director, Cartha DeLoach, about the panel's activities.[17][18]

Members

[edit]- Members of the Warren Commission

- Committee

- Earl Warren, Chief Justice of the United States (chairman) (1891–1974)

- Richard Russell Jr. (D-Georgia), U.S. Senator (1897–1971)

- John Sherman Cooper (R-Kentucky), U.S. Senator (1901–1991)

- Hale Boggs (D-Louisiana), U.S. Representative, House Majority Whip (1914–1972)

- Gerald Ford (R-Michigan), U.S. Representative (later 38th President of the United States), House Minority Leader (1913–2006)

- Allen Dulles, former Director of Central Intelligence and head of the Central Intelligence Agency (1893–1969)

- John J. McCloy, former president of the World Bank (1895–1989)

- General counsel

- J. Lee Rankin (1907–1996)[19]

|

|

Conclusions of the report

[edit]The report concluded that:

- The shots which killed President Kennedy and wounded Governor Connally were fired from the sixth-floor window at the southeast corner of the Texas School Book Depository.

- President Kennedy was first struck by a bullet which entered at the back of his neck and exited through the lower front portion of his neck, causing a wound which would not necessarily have been lethal. The President was struck by a second bullet, which entered the right-rear portion of his head, causing a massive and fatal wound.

- Governor Connally was struck by a bullet which entered on the right side of his back and traveled downward through the right side of his chest, exiting below his right nipple. This bullet then passed through his right wrist and entered his left thigh then it caused a superficial wound.

- There is no credible evidence that the shots were fired from the Triple Underpass, ahead of the motorcade, or from any other location.

- The weight of the evidence indicates that there were three shots fired.

- Although it is not necessary to any essential findings of the Commission to determine just which shot hit Governor Connally, there is very persuasive evidence from the experts to indicate that the same bullet which pierced the President's throat also caused Governor Connally's wounds. However, Governor Connally's testimony and certain other factors have given rise to some difference of opinion as to this probability but there is no question in the mind of any member of the Commission that all the shots which caused the President's and Governor Connally's wounds were fired from the sixth-floor window of the Texas School Book Depository.

- The shots which killed President Kennedy and wounded Governor Connally were fired by Lee Harvey Oswald.

- Oswald killed Dallas Police Patrolman J. D. Tippit approximately 45 minutes after the assassination.

- Ruby entered the basement of the Dallas Police Department and killed Lee Harvey Oswald and there is no evidence to support the rumor that Ruby may have been assisted by any members of the Dallas Police Department.

- The Commission has found no evidence that either Lee Harvey Oswald or Jack Ruby was part of any conspiracy, domestic or foreign, to assassinate President Kennedy.

- The Commission has found no evidence of conspiracy, subversion, or disloyalty to the U.S. Government by any Federal, State, or local official.

- The Commission could not make any definitive determination of Oswald's motives.

- The Commission believes that recommendations for improvements in Presidential protection are compelled by the facts disclosed in this investigation.[20]

Death of Lee Harvey Oswald

[edit]In response to Jack Ruby's shooting of Lee Harvey Oswald, the Warren Commission declared that the news media must share responsibility with the Dallas police department for "the breakdown of law enforcement" that led to Oswald's death. In addition to the police department's "inadequacy of coordination", the Warren Commission noted that "these additional deficiencies [in security] were directly related to the decision to admit newsmen to the basement".[21]

The commission concluded that the pressure of press, radio, and television for information about Oswald's prison transfer resulted in relaxed security standards for admission to the basement, allowing Ruby to enter and subsequently shoot Oswald, noting that "the acceptance of inadequate press credentials posed a clear avenue for a one-man assault." Oswald's death was said to have been a direct result of "the failure of the police to remove Oswald secretly or control the crowd in the basement."[21]

The consequence of Oswald's death, according to the Commission, was that "it was no longer possible to arrive at the complete story of the assassination of John F. Kennedy through normal judicial procedures during the trial of the alleged assassin." While the Commission noted that the prime responsibility was that of the police department, it also recommended the adoption of a new "code of conduct" for news professionals regarding the collecting and presenting of information to the public that would ensure "there [would] be no interference with pending criminal investigations, court proceedings, or the right of individuals to a fair trial."[22]

Aftermath

[edit]

Secret Service

[edit]The findings prompted the Secret Service to make numerous modifications to its security procedures.[23][24] The Commission made other recommendations to the Congress to adopt new legislation that would make the murder of the President (or Vice-President) a federal crime, which was not the case in 1963.[25]

Commission records

[edit]In November 1964, two months after the publication of its 888-page report, the commission published twenty-six volumes of supporting documents, including the testimony or depositions of 552 witnesses[26] and more than 3,100 exhibits[27] making a total of more than 16,000 pages. The Warren Report, however, lacked an index, which greatly complicated the work of reading. It was later endowed with an index by the work of Sylvia Meagher for the report and the twenty-six volumes of documents.[28]

All of the commission's records were then transferred on November 23 to the National Archives. The unpublished portion of those records was initially sealed for seventy-five years (to 2039) under a general National Archives policy that applied to all federal investigations by the executive branch of government,[29] a period "intended to serve as protection for innocent persons who could otherwise be damaged because of their relationship with participants in the case."[30]

The 75-Year Rule no longer exists, supplanted by the Freedom of Information Act of 1966 and the JFK Records Act of 1992. By 1992, ninety-eight percent of the Warren Commission records had been released to the public.[31] Six years later, after the Assassination Records Review Board's work, all Warren Commission records, except those records that contained tax return information, were available to the public with redactions.[32]

The remaining Kennedy assassination-related documents were partly released to the public on October 26, 2017,[33] twenty-five years after the passage of the JFK Records Act. President Donald Trump, as directed by the FBI and the CIA,[34] took action on that date to withhold certain remaining files, delaying the release until April 26, 2018,[34] then on April 26, 2018, took action to further withhold the records "until 2021".[35][36][37]

CIA "benign cover-up"

[edit]According to a report by the CIA Chief Historian David Robarge (which was released to the public in 2014), CIA Director McCone was complicit in a Central Intelligence Agency "benign cover-up" by withholding information from the Warren Commission.[38] According to this report, CIA officers had been instructed to give only "passive, reactive, and selective" assistance to the commission, to keep the commission focused on "what the Agency believed at the time was the 'best truth' — that Lee Harvey Oswald, for as yet undetermined motives, had acted alone in killing John Kennedy." The CIA may have also covered up evidence of being in communication with Oswald before 1963, according to the 2014 report findings.[38]

Also withheld were earlier CIA plots, involving CIA links with the Mafia, to assassinate Cuban president Fidel Castro, which might have been considered to provide a motive to assassinate Kennedy. The report concluded, "In the long term, the decision of John McCone and Agency leaders in 1964 not to disclose information about CIA's anti-Castro schemes might have done more to undermine the credibility of the Commission than anything else that happened while it was conducting its investigation."[38][39]

Skepticism

[edit]

Many independent investigators, journalists, historians, jurists, and academics issued opinions opposing the conclusions of the Warren commission based on the same elements collected by its works.[25][10]

These skeptics and their works included Thomas Buchanan, Sylvan Fox, Harold Feldman, Richard E. Sprague, Mark Lane's Rush to Judgment, Edward Jay Epstein's Inquest, Harold Weisberg's Whitewash, Sylvia Meagher's Accessories After the Fact or Josiah Thompson's Six Seconds in Dallas. English historian Hugh Trevor-Roper wrote: "The Warren Report will have to be judged, not by its soothing success, but by the value of its argument. I must admit that from the first reading of the report, it seemed impossible to me to join in this general cry of triumph. I had the impression that the text had serious flaws. Moreover, when probing the weak parts, they appeared even weaker than at first sight."[10]

In 1992, following popular political pressure in the wake of the film JFK, the Assassination Records Review Board (ARRB) was created by the JFK Records Act to collect and preserve the documents relating to the assassination. In a footnote in its final report, the ARRB wrote: "Doubts about the Warren Commission's findings were not restricted to ordinary Americans. Well before 1978, President Johnson, Robert F. Kennedy, and four of the seven members of the Warren Commission all articulated, if sometimes off the record, some level of skepticism about the Commission's basic findings."[40]

Weak points of the report

[edit]The Warren Commission argued that direct witnesses to the shooting, who immediately rushed en masse to the grassy knoll after the shots were fired, were fleeing the area of the shooting. In reality, the people present, including a dozen members of the security forces, in particular Sheriff Decker's team, who had given the order to investigate the area, all testified that they were running to the search for one or more shooters posted on the grassy Knoll.[10]

The Commission did not examine photographs or X-rays of President Kennedy's body, although they did have the power to subpoena them. Commission member John J. McCloy later said that "I think that if there’s one thing that I would do over again, I would insist on those photographs and the X-rays having been produced before us".[41]

It did not interview John Fitzgerald Kennedy's personal doctor, George Burkley, who was present during the shooting in the convoy of official vehicles then at Parkland Hospital, on board Air Force One, then at Bethesda Naval Hospital during the autopsy. He signed the death certificate and also took delivery of the brain of John Fitzgerald Kennedy which is declared lost in the National Archives. Concerning the conclusions of the Warren commission about the three shots, the practitioner had declared in 1967: "I would not like to be quoted on this subject".[42][better source needed]

The ballistic reports conducted by the FBI and the autopsy reports were not the subject of any counter-investigation, which made the commission directly dependent on the work of the latter. The Warren Commission, by decision of Earl Warren, refused to hire its own independent investigators. However, it had its own investigative capacity thanks to direct access to the emergency presidential budget funds granted by President Lyndon Johnson when it was created, to conduct its own investigations. Thus the Warren commission was not informed by the FBI of the discovery the day after the attack, on November 23, 1963, by a medical student, William Harper, of a piece of occiput located at the rear left in relation to at the position of the presidential limo during the fatal shot to the head. He had it examined by the professor and medical examiner, Doctor Cairns who measured it and photographed this piece before informing the FBI, on November 25, 1963. The latter received instructions not to make any publicity on this subject. It was the Attorney General, Robert F. Kennedy, who, informed by a letter from Dr. Cairns transmitted to the Warren Commission, allowed the latter to question the practitioner.[10] The non-use by the members of the Warren Commission of the direct elements of the autopsy such as notes, photos and x-rays. He only used drawings by FBI artists reproducing photographic images.[10]

The revelation by Edward Jay Epstein, in his book Inquest published in 1966,[43] that as early as the beginning of 1964, the chief adviser, J. Lee Rankin, had given the outcome of the results of the work of the commission: guilt of Oswald, the latter having acted alone. Even before the creation of the commission, on November 25, 1963, and a few hours after the assassination of Lee Harvey Oswald by Jack Ruby in the premises of the Dallas police, Nicolas Katzenbach, assistant attorney general, had indicated in a memorandum intended of Bill Moyers that: "The public must be convinced that Oswald was the killer; that he had no accomplices still at large; and that evidence was such that he would have been found guilty at trial"[44] creating a political orientation of the results of the investigation, even before the start of the first official investigations and knowledge of the results. Its objective was to cut short the speculations of public opinion either on a plot of communist origin (thesis of the Dallas police) or a plot fomented by the far right to blame the communists (hypothesis defended by the press of communist bloc formed around the USSR).

As early as the 1970s, official members of the Warren Commission questioned its work, in particular Hale Boggs who criticized the influence of J. Edgar Hoover, the director of the FBI from 1924 to 1972, who had centralized all of the information from the FBI agents before synthesizing it and transmitting it to the Warren Commission. He campaigned for a reopening of the file considering that the director of the FBI had lied to the Warren commission.[citation needed] He disappeared in a plane crash in October 1972.[10]

Commission member Richard Russell told the Washington Post in 1970 that Kennedy had been the victim of a conspiracy, criticizing the commission's no-conspiracy finding and saying "we weren't told the truth about Oswald".[citation needed] John Sherman Cooper also considered the ballistic findings to be "unconvincing".[citation needed] Russell also particularly rejected Arlen Specter's "single bullet" theory, and he asked Earl Warren to indicate his disagreement in a footnote, which the chairman of the commission refused.[citation needed]

Other investigations

[edit]Four other U.S. government or senate investigations have been conducted about the Warren Commission's conclusion or its material in different circumstances. The Church Committee analyzed in 1976 the work of the CIA and FBI which had communicated the different elements to the Warren Commission Members.[45] The three others concluded with the initial conclusions that two shots struck JFK from the rear: the 1968 panel set by Attorney General Ramsey Clark, the 1975 Rockefeller Commission, and the 1978-79 House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA), which reexamined the evidence with the help of the largest forensics panel and bringing new materials to the public.

The Church Committee

[edit]In 1975, the Church Committee was created per US Senate after the revelations about illegal actions of federal agency as the FBI, CIA and IRS on the territory of the United States of America and after the political Watergate scandal. The Church Committee carried out investigative work on the assassination of John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963, questioning 50 witnesses and accessing 3,000 documents.[citation needed]

It focuses on the necessary actions and the support provided by the FBI and the CIA to the Warren Commission and raises the question of the possible connection between the plans to assassinate political leaders abroad, in particular in relation to Fidel Castro in Cuba, a huge point of international tension in the 1960s, and that of the 35th President of the United States, John F. Kennedy. The Church Committee questioned the process of obtaining the information, blaming federal agencies for failing in their duties and responsibilities and concluding that the investigation into the assassination had been flawed.[45]

The American Senator Richard Schweiker indicated on this subject, in a television interview on June 27, 1976: "The John F. Kennedy assassination investigation was snuffed out before it even began," and that "the fatal mistake the Warren Commission made was to not use its own investigators, but instead to rely on the CIA and FBI personnel, which played directly into the hands of senior intelligence"[25].

The results of the Church Committee opened the way of the creation of the HSCA, with parallelly the March 6, 1975, first time diffusion on network television in the show Good Night America of the Zapruder film, which had been stored by Life magazine and never shown to the public during the preceding twenty years.[citation needed]

The House Select Committee on Assassinations

[edit]The HSCA involved Congressional hearings and ultimately concluded that Oswald assassinated Kennedy, probably as the result of a conspiracy. The HSCA concluded that Oswald fired shots number one, two, and four, and that an unknown assassin fired shot number three (but missed) from near the corner of a picket fence that was above and to President Kennedy's right front on the Dealey Plaza grassy knoll. However, this conclusion has also been criticized, especially for its reliance upon disputed acoustic evidence. The HSCA Final Report in 1979 did agree with the Warren Report's conclusion in 1964 that two bullets caused all of President Kennedy's and Governor Connally's injuries, and that both bullets were fired by Oswald from the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository.[46]

In his September 1978 testimony to the HSCA, President Ford defended the Warren Commission's investigation as thorough.[47] Ford stated that knowledge of the assassination plots against Castro may have affected the scope of the Commission's investigation but expressed doubt that it would have altered its finding that Oswald acted alone in assassinating Kennedy.[47]

As part of its investigation, the HSCA also evaluated the performance of the Warren Commission, which included interviews and public testimony from the two surviving Commission members (Ford and McCloy) and various Commission legal counsel staff. The Committee concluded in their final report that the Commission was reasonably thorough and acted in good faith, but failed to adequately address the possibility of conspiracy:[48] "...the Warren Commission was not, in some respects, an accurate presentation of all the evidence available to the Commission or a true reflection of the scope of the Commission's work, particularly on the issue of possible conspiracy in the assassination."[49]

The HSCA also pointed to the role of the mafia in the attack because of Cuba. Indeed, the Cuban Castro Revolution of 1959 had caused the criminal organization to lose millions of dollars, which had tried in vain to win the favors of the Cuban leader during the change of regime. In 1959, the income generated by criminal activities amounted to an annual amount of 100 million dollars, i.e. 900 million reported in 2013.[50]

The HSCA determined that the gradual change in policy of the Kennedy administration toward Cuba, first with the failure of the Bay of Pigs Invasion in April 1961, then more sustainably with the missile crisis of October 1962, in order to appease relations with the Cuban regime on a lasting basis and to open up new prospects, contributed to directing, if not slightly, within the many groups of paramilitary operations the most radical fringe of anti-Castro Cubans, American intelligence agents and Mafia criminals who continued their operations to overthrow the regime of Fidel Castro despite requests for formal arrests from the White House.[51] The HSCA invited the Department of Justice to resume investigations. The latter would respond eight years later, arguing the absence of decisive evidence allowing the reopening of an investigation, which is equivalent to supporting the conclusions of Warren report.[10]

Legacy

[edit]The findings of the Warren Commission are generally highly criticized, and while the majority of American citizens believe that Oswald shot President Kennedy, the majority also believe that Oswald was part of a conspiracy and therefore do not believe the official thesis defended by the commission. In 1976, 81% of Americans disputed the findings of the Warren Report, 74% in 1983, 75% in 1993 and 2003.[10] In 2009, a CBS poll indicated that 74% of respondents believed there had been an official cover-up by the authorities to keep the general public away from the truth.[50]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Peters, Gerhard; Woolley, John T. "Lyndon B. Johnson: "Executive Order 11130 – Appointing a Commission To Report Upon the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy," November 29, 1963". The American Presidency Project. University of California – Santa Barbara.

- ^ Baluch, Jerry T. (November 30, 1963). "Warren Heads into Assassination". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. p. 1.

- ^ 77 Stat. 362"Joint resolution authorizing the Commission established to report on the assassination of President John F. Kennedy to compel the attendance and testimony of witnesses and the production of evidence – P.L. 88-202" (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. December 13, 1963. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

- ^ Mohr, Charles (September 25, 1964). "Johnson Gets Assassination Report". The New York Times. p. 1.

- ^ Roberts, Chalmers M. (September 28, 1964). "Warren Report Says Oswald Acted Alone; Raps FBI, Secret Service". The Washington Post. p. A1.

- ^ Lewis, Anthony (September 28, 1964). "Warren Commission Finds Oswald Guilty and Says Assassin and Ruby Acted Alone". The New York Times. p. 1.

- ^ Pomfret, John D. (September 28, 1964). "Commission Says Ruby Acted Alone in Slaying". The New York Times. p. 17.

- ^ Morris, John D. (November 30, 1963). "Johnson Names a 7-Man Panel to Investigate Assassination; Chief Warren Heads It". The New York Times. p. 1.

- ^ Beschloss, Michael R. (1997). "Taking charge: the Johnson White House tapes, 1963-1964". New York: Simon & Schuster.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l LENTZ, Thierry (2010). L'assassinat de John F. Kennedy: Histoire d'un mystère d'Etat (Assassination of John F. Kennedy : history of State mystery) (in French). Paris: Edition Nouveaux Mondes. ISBN 978-2847365085.

- ^ a b c d Savage, David G. (May 10, 2012). "Nicholas Katzenbach dies at 90; attorney general under Johnson". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Nicholas Katzenbach, JFK and LBJ aide, dead at 90". Politico. AP. May 9, 2012. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

- ^ Bird, Kai (2017). The Chairman: John J McCloy & The Making of the American Establishment. Simon & Schuster. pp. V–VI.

- ^ Epstein, Edward Jay (1966). Inquest; the Warren Commission and the establishment of truth. Viking Press. p. 46.

- ^ "Warren Commission Meets". Lodi News-Sentinel. Lodi, California. UPI. December 6, 1964. p. 2. Retrieved November 12, 2014.

- ^ Bugliosi 2007, p. 332

- ^ Stephens, Joe (August 8, 2008). "Ford Told FBI of Skeptics on Warren Commission". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 1, 2011. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- ^ "Ford told FBI about panel's doubts on JFK murder". USA Today. August 9, 2008. Archived from the original on November 6, 2008. Retrieved September 2, 2009.

- ^ DeLoach, C. D. (December 12, 1963). "Miscellaneous Records of the Church Committee; Memorandum to Mr. Mohr; Subject: ASSASSINATION OF THE PRESIDENT" (PDF). National Archives and Records Administration. p. 14. Retrieved November 18, 2021.

On the occasion of their second meeting, Ford and Hale Boggs joined with Dulles. Hale Boggs told Warren flatly that [Warren] Olney would not be acceptable and that he (Boggs) would not work on the Commission with [former Assistant Attorney General] Olney. Warren put up a stiff argument but a compromise was made when the name of Lee Rankin was mentioned. Warren stated he knew Rankin and could work with him.,

- ^ "Chapter 1". Warren Commission Report. National Archives. September 24, 1964.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "Press and Dallas Police Blamed for Confusion That Permitted Slaying of Oswald". The New York Times. September 28, 1964. Archived from the original on April 16, 2024. Retrieved April 15, 2024.

- ^ Fixx, James F. (1972). The Great Contemporary Issues: The Mass Media and Politics. New York, NY: Ayer Co. Publishing. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-0405012914.

- ^ Belair Jr., Felix (September 28, 1964). "(Warren Commission) Rebukes Secret Service, Asks Revamping". The New York Times. p. 1.

- ^ "Johnson Names 4 to Act on Report". The New York Times. Associated Press. September 28, 1964. p. 1.

- ^ a b c Marry Ferrel Foundation (March 4, 2023). "Warren Commission". Mary Ferrel Foundation - preserving the legacy. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ "Warren Commission Report: Appendix 5". National Archives. August 15, 2016. Retrieved November 25, 2023.

…list of the 552 witnesses whose testimony has been presented to the commission. Witnesses who appeared before members of the commission… those questioned during depositions by members of the Commission's legal staff… those who supplied affidavits and statements…

- ^ Lewis, Anthony (November 24, 1964). "Kennedy Slaying Relived in Detail in Warren Files". The New York Times. p. 1.

- ^ Sylvia Meagher, Gary Owens (1980). Master Index to the J. F. K. Assassination Investigations: The Reports and Supporting Volumes of the House Select Committee on Assassinations and the Warren Commission. Michigan University: Scarecrow Press.

- ^ Bugliosi 2007, pp. 136–137

- ^ National Archives Deputy Dr. Robert Bahmer, interview in New York Herald Tribune, December 18, 1964, p.24

- ^ Final Report of the Assassination Records Review Board (1998), p.2.

- ^ ARRB Final Report, p. 2. Redacted text includes the names of living intelligence sources, intelligence gathering methods still used today and not commonly known, and purely private matters. The Kennedy autopsy photographs and X-rays were never part of the Warren Commission records, and were deeded separately to the National Archives by the Kennedy family in 1966 under restricted conditions.

- ^ "25th JFK Assassination Secrets Scheduled for 2017 Release". Time. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ^ a b Laurie Kellman, Deb Riechmann (November 22, 1963). "'I have no choice': Trump blocks the release of hundreds of JFK files". Business Insider. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- ^ "Trump delays release of some JFK assassination files until 2021". Los Angeles Times. April 26, 2018.

- ^ Jeremy B White (April 26, 2018). "Donald Trump blocks release of some JFK assassination files". The Independent. Retrieved September 28, 2019.

- ^ "[U]nless the president certifies that continued postponement is made necessary by an identifiable harm to the military defense, intelligence operations, law enforcement, or conduct of foreign relations, and the identifiable harm is of such gravity that it outweighs the public interest in disclosure." — JFK Records Act. Both the National Archives and the former chairman of the ARRB estimate that 7.6 percent of all identified Kennedy assassination records have been released to the public. The great majority of the unreleased records are from subsequent investigations, including the Rockefeller Commission, the Church Committee, and the House Select Committee on Assassinations.

- ^ a b c Shenon, Philip (October 6, 2014). "Yes, the CIA Director Was Part of the JFK Assassination Cover-Up". POLITICO Magazine. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ^ David Robarge (September 2013). "DCI John McCone and the Assassination of President John F. Kennedy" (PDF). Studies in Intelligence. 57 (3). CIA: 7–13, 20. C06185413. Retrieved October 8, 2015.

- ^ Assassination Records Review Board (September 30, 1998). "Chapter 1: The Problem of Secrecy and the Solution of the JFK Act". Final Report of the Assassination Records Review Board (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. p. 11. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- ^ "Panel Should Have Viewed JFK Death Photos - McCloy". The Press-Courier. July 2, 1967.

- ^ Mary Ferrel Foundation (March 4, 2023). "The missing physician". www.maryferrell.org. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ Epstein, Edward J. (1966). Inquest. The Warren Commission and the Establishment of Truth. New York: Bantam. p. 245.

- ^ Mary Ferrel Foundation (March 4, 2023). "Katzenbach Memo". Mary Ferrel Foundation. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ a b US State Senate, Select Committee to tudy governmental operations wit respect to intelligence Agency (April 26, 1979). Book V - The Investigation of the Assassination of President John F Kennedy performances of the intelligence agency (First ed.). Washington: US Government Printing Office.

- ^ HSCA Final Report, pp. 41-46.

- ^ a b "Ford defends panel's findings". Lawrence Journal Daily World. Vol. 120, no. 226. Lawrence, Kansas. AP. September 21, 1978. p. 1. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ^ "Findings". archives.gov. August 15, 2016. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ US House of representatives, House Select Committee on Assassinations (January 2, 1979). Final Report : summary and findings (First ed.). Washington: US Government Printing Office. p. 261.

- ^ a b Summer, Anthony (2013). Not in Your Life Time. London: Headline Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-7553-6542-5.

- ^ US House of representatives, House Select Committee on Assassinations (1979). Volume X : The Ingredients of an Anti-Castro Cuban Conspiracy (First ed.). Washington: US Government Publishing Office. pp. 5–18.

Further reading

[edit]- Bugliosi, Vincent (2007). Reclaiming History: The Assassination of President John F. Kennedy. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-393-04525-3.

- Shenon, Philip (2013). A Cruel and Shocking Act: The Secret History of the Kennedy Assassination. New York: Henry Holt and Co. ISBN 9780349140612.

- Macdonald, Dwight. "A Critique of the Warren Report." Esquire, March 1965, pp. 60+.

External links

[edit]- Warren Commission Report (Full Text)

- Warren Commission Hearings (Full Text)

- Assassination Records Review Board

- House Select Committee on Assassinations

- Rockefeller Commission

- Church Committee

- Works by the Warren Commission at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about the Warren Commission at the Internet Archive

- The short film "November 22nd and The Warren Report (1964)" is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- Works by Warren Commission at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

Warren Commission

View on GrokipediaEstablishment

Historical Context of the Assassination

On November 22, 1963, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated while riding in an open-top limousine through Dealey Plaza in Dallas, Texas, during a scheduled political visit to the state.[8] The event took place at approximately 12:30 p.m. local time, as the presidential motorcade proceeded from Dallas Love Field airport toward the downtown area, following a brief stopover from Fort Worth.[9] Kennedy had arrived in Texas the previous day as part of a multi-city tour aimed at mending intra-party divisions within the Democratic ranks, particularly between liberal and conservative factions in a state critical to his reelection prospects for 1964.[8] The trip reflected broader political dynamics of Kennedy's presidency, marked by efforts to consolidate support in the South amid ongoing civil rights advancements and economic recovery initiatives. Texas Governor John Connally, a Kennedy appointee, accompanied the president, underscoring the itinerary's focus on unifying Democratic leadership.[9] Advance preparations had been underway for weeks, involving coordination with local authorities for security along the 10-mile motorcade route, which included a slow passage through crowded streets to maximize public exposure.[9] Dallas, in particular, hosted a segment planned to culminate at a luncheon with business and political leaders, though the city had seen vocal anti-Kennedy demonstrations in prior months due to perceptions of his administration's liberal policies.[8] This assassination unfolded against the backdrop of intensified U.S.-Soviet rivalry during the Cold War, including the lingering effects of the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, where Kennedy's naval quarantine of Cuba averted nuclear escalation but heightened domestic scrutiny of perceived communist threats.[10] Lee Harvey Oswald, a former U.S. Marine who had defected to the Soviet Union in 1959 before returning in 1962, was arrested within hours of the shooting; he had been employed at the Texas School Book Depository building overlooking Dealey Plaza and maintained pro-Castro sympathies through affiliations like the Fair Play for Cuba Committee.[8] The rapid sequence of events—Kennedy's death pronounced at Parkland Hospital shortly after the shots, followed by Oswald's murder two days later by nightclub owner Jack Ruby—fueled immediate public demands for a thorough federal inquiry into potential conspiracies amid the era's geopolitical suspicions.[11]Creation and Legal Mandate

On November 29, 1963, seven days after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963, in Dallas, Texas, President Lyndon B. Johnson issued Executive Order 11130, formally establishing the President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy, known as the Warren Commission.[2][12] The order responded to immediate public speculation and international concerns about potential conspiracies involving foreign powers, aiming to ascertain facts and mitigate risks of escalation.[13] The Commission's primary legal mandate, as outlined in the executive order, was to "ascertain, evaluate, and report upon the facts relating to the assassination of the late President John F. Kennedy and related events," including the circumstances of Lee Harvey Oswald's killing by Jack Ruby two days later.[2][14] This involved examining evidence gathered by federal agencies such as the FBI, conducting an independent review of all pertinent circumstances, and providing a comprehensive report to the President with any recommendations for preventing similar incidents.[1][6] Unlike a judicial body, the Commission lacked prosecutorial authority and served solely as an investigative panel to compile and analyze information without binding legal determinations. Executive Order 11130 granted the Commission specific powers, including the authority to subpoena witnesses or documents, administer oaths, and hold public or private hearings as deemed necessary.[15] Johnson appointed Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren as chairman, along with six other members: Senators Richard Russell Jr. and John Sherman Cooper, Representatives Hale Boggs and Gerald Ford, former CIA Director Allen Dulles, and banker John J. McCloy.[2] The order stipulated that the Commission report its findings as promptly as possible, emphasizing thoroughness amid pressures to resolve uncertainties surrounding the national trauma.[13]Organization and Operations

Membership and Key Personnel

The Warren Commission, formally the President's Commission on the Assassination of President Kennedy, was established by Executive Order 11130 signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson on November 29, 1963.[2] The order appointed seven members, selected for their prominence in government, law, and intelligence, to investigate the assassination of President John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963, and the subsequent killing of Lee Harvey Oswald.[1]| Member | Position | Background |

|---|---|---|

| Earl Warren | Chairman | Chief Justice of the United States; former Governor and Attorney General of California.[1] |

| Richard B. Russell, Jr. | Member | U.S. Senator from Georgia (Democrat).[1] |

| John Sherman Cooper | Member | U.S. Senator from Kentucky (Republican).[1] |

| Hale Boggs | Member | U.S. Representative from Louisiana (Democrat).[1] |

| Gerald R. Ford | Member | U.S. Representative from Michigan (Republican); House Minority Leader.[1] |

| Allen W. Dulles | Member | Former Director of Central Intelligence (1953–1961).[1] |

| John J. McCloy | Member | Former President of the World Bank; former U.S. High Commissioner for Germany.[1] |

Meetings, Procedures, and Resource Allocation

The Warren Commission convened its initial formal meeting on December 5, 1963, at the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C., where members organized their approach and assigned preliminary tasks. Subsequent executive sessions followed on December 6 and 16, 1963, focusing on early investigative priorities such as Oswald's potential connections to foreign entities, and additional sessions occurred, including one on January 27, 1964, to address specific allegations like Oswald's alleged FBI informant status. In total, the Commission held 12 formal meetings over its tenure, culminating in the September 24, 1964, session at which the final report was approved and delivered to President Lyndon B. Johnson.[18][19] Commission procedures centered on compiling evidence through agency-supplied materials rather than independent fieldwork, with staff divided into teams to examine discrete topics such as Oswald's biography, the shooting sequence, and possible conspiracies. Primary reliance was placed on the FBI's extensive investigation, which furnished thousands of documents, interviews, and forensic analyses, supplemented by inputs from the CIA, Secret Service, and other agencies; this dependence stemmed from the Commission's limited mandate and timeline under Executive Order 11130. Staff attorneys took sworn depositions from 395 witnesses, while 94 witnesses testified directly before one or more Commissioners in hearings requiring at least one member present; depositions involved oaths, rights to counsel, three-day notice (often waived), and stenographic transcripts, but lacked courtroom-style confrontation or compulsory process for most evidence, prioritizing cooperative requests over subpoenas. The Commission assessed credibility through cross-referencing reports and internal debates, diverging from trial standards by emphasizing comprehensive documentation over adversarial testing.[13][20][21] Resource allocation supported a compact operation, with a core staff of about 83 members—including 15-20 lead attorneys under General Counsel J. Lee Rankin, plus researchers, historians, and clerks—coordinated from temporary offices in the National Archives and later the VFW Building. This was augmented by roughly 222 detailed personnel from federal agencies, enabling focused efforts without a large permanent investigative force; for instance, FBI agents handled most witness interviews and physical evidence collection. The total expenditure reached $1.2 million across the approximately 10-month period, covering salaries, travel, transcription, and printing, with no formal congressional appropriation but funding drawn from executive contingency resources. Such constraints, while promoting efficiency, constrained original inquiries, as the Commission deferred to agency expertise on technical matters like ballistics and cryptography.[22][21]Core Investigations

Examination of Lee Harvey Oswald

The Warren Commission conducted an extensive investigation into Lee Harvey Oswald, compiling evidence from interviews, documents, forensic analysis, and witness statements to determine his role in the assassination of President Kennedy. This examination spanned Oswald's early life, military service, international travels, domestic activities, and immediate post-assassination behavior, ultimately concluding that he fired the fatal shots from the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository.[23][24] Key sources included testimony from Oswald's wife, Marina, FBI records, and ballistic comparisons, with no credible evidence emerging of foreign or domestic conspirators directing his actions.[23][24] Oswald was born on October 18, 1939, in New Orleans, Louisiana, to a widowed mother, Marguerite, following his father's death two months prior; the family faced financial instability, leading to frequent relocations and Oswald's placement in an orphanage from ages 3 to 6.[24] He exhibited early behavioral issues, including truancy and a 1953 psychiatric evaluation noting immaturity and hostility, though no severe pathology.[24] Enlisting in the U.S. Marine Corps in October 1956 at age 17, Oswald qualified as a sharpshooter with rifle scores of 212 in December 1956 and 191 in May 1959, receiving training in marksmanship and receiving an undesirable discharge in 1962 after his Soviet defection.[23][24] In October 1959, at age 19, he defected to the Soviet Union, renouncing U.S. citizenship and attempting suicide upon initial rejection; he resided in Minsk until June 1962, marrying Marina Prusakova in April 1961 and fathering a daughter, June, before returning to the U.S. disillusioned with Soviet life.[24] Upon repatriation via Fort Worth, Texas, Oswald secured intermittent employment while expressing Marxist sympathies, subscribing to publications like The Worker and The Militant, and founding a one-man chapter of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee in New Orleans by August 1963.[24] There, he distributed pro-Castro leaflets under the alias "A. Hidell," clashed with anti-Castro exiles, and was arrested on August 9, 1963, for disturbing the peace after a street altercation.[24] Relocating to Dallas in late September 1963, he obtained a job at the Texas School Book Depository on October 16, 1963, from which vantage point the shots were fired; he practiced with firearms, including hunting trips, and on April 10, 1963, attempted to assassinate retired Major General Edwin A. Walker, firing a shot that missed Walker's head, as corroborated by Marina Oswald's testimony, a farewell note, and ballistic evidence linking the bullet to Oswald's rifle with fair probability.[23][24] The Commission established Oswald's ownership of the 6.5-millimeter Mannlicher-Carcano rifle (serial C2766) used in the assassination through a March 13, 1963, mail-order purchase from Klein's Sporting Goods in Chicago, shipped to "A. J. Hidell" at Oswald's Dallas post office box on March 20, 1963, confirmed by handwriting analysis on the order form and envelope.[23] His palmprint appeared on the rifle barrel, fibers from his shirt matched those on the weapon, and backyard photographs dated March 31, 1963, depicted him holding the rifle and a pistol, authenticated by photographic experts.[23] On November 22, 1963, Oswald carried the disassembled rifle to the Depository in a paper bag, as evidenced by his prints on the bag and cartons positioned at the sixth-floor sniper's nest; three spent cartridge cases recovered there matched the rifle via FBI ballistic tests.[23] Eyewitness Howard Brennan identified Oswald in the window moments after the shots, describing a man aiming a rifle.[23] Following the assassination at approximately 12:30 p.m., Oswald departed the Depository around 12:33 p.m., traveling by bus and taxi to his rooming house at 1026 North Beckley Avenue, arriving near 1:00 p.m., then proceeding on foot.[23] At about 1:15-1:16 p.m., he fatally shot Dallas Police Officer J. D. Tippit on Tenth Street and Patton Avenue after Tippit stopped him; twelve eyewitnesses identified Oswald as the shooter, who emptied his Smith & Wesson revolver (serial V510210), with four bullets matching the weapon recovered from him upon arrest at the Texas Theatre around 1:50 p.m., where he resisted officers while armed.[23] The Commission found these actions indicative of flight and guilt, with Oswald possessing $13.87 and leaving $170 at home, inconsistent with routine behavior.[23][24] Oswald's political ideology—rooted in Marxism, admiration for Fidel Castro, and resentment toward U.S. policies, particularly on Cuba—combined with personal alienation, marital strife, and a quest for notoriety, formed the basis for inferred motives, as detailed in his writings and Marina's accounts of his post-Mexico City trip despondency in September-October 1963.[24] Despite contacts with Soviet and Cuban embassies in Mexico City and Fair Play for Cuba affiliations, the Commission uncovered no evidence of encouragement or employment by foreign powers, nor domestic conspiracy, attributing the assassination to Oswald's solitary initiative.[23][24] Interrogations of Oswald from 2:30 p.m. on November 22 until his death yielded no confession, but circumstantial and forensic linkages prevailed in the Commission's assessment.[25]Ballistics, Forensics, and Physical Evidence

The Warren Commission examined a 6.5-millimeter Italian Mannlicher-Carcano rifle, serial number C2766, recovered from the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository on November 22, 1963, along with three cartridge cases and matching live ammunition traced to Oswald's mail-order purchase under the alias "A. Hidell."[4] Firearms identification experts from the FBI and U.S. Army Ballistics Research Laboratory conducted tests, firing the rifle and comparing rifling marks, which conclusively matched the cartridge cases and two large bullet fragments recovered from the presidential limousine and Connally's stretcher to this weapon.[4][26] A nearly intact bullet, designated Commission Exhibit 399 (CE 399), found on a stretcher at Parkland Hospital, exhibited rifling characteristics consistent with the rifle, though its minimal deformation after purportedly traversing two bodies was noted in expert testimony as unusual but possible for full-metal-jacket ammunition.[4] Forensic analysis included neutron activation and emission spectrography of bullet fragments: two large pieces from the front seat of the limousine (one weighing 21.0 grains, the other 20.0 grains) and smaller fragments from Connally's wrist and thigh wounds showed lead composition and trace elements aligning with Western Cartridge Company ammunition used in the rifle tests.[26] These matches supported the Commission's determination that all recovered projectiles originated from Oswald's rifle, excluding other weapons.[4] However, the spectrographic method's limitations in distinguishing individual bullets from the same manufacturing batch were later highlighted in independent reviews, as it relied on bulk elemental similarities rather than unique isotopic signatures.[27] The autopsy, performed at Bethesda Naval Hospital on November 22, 1963, documented two bullet wounds to Kennedy: an entry in the upper back at the third thoracic vertebra (approximately 5.5 inches below the mastoid process), exiting the throat, and a fatal tangential entry in the rear skull above the external occipital protuberance, causing massive brain disruption with 1500 grams of fragmented tissue and exit fragmentation forward.[28][29] X-rays revealed metallic fragments along the head wound track, with the largest (7 by 2 millimeters) near the right orbit, consistent with a high-velocity 6.5-millimeter projectile's disintegration.[28] Pathologists noted no evidence of frontal entry wounds, attributing all damage to rear-origin shots, though chain-of-custody issues from Parkland to Bethesda, including unexamined initial hospital records, complicated wound trajectory reconstructions.[4] Connally's autopsy confirmed entry in the back below the right shoulder blade, shattering his fifth rib, exiting below the right nipple, then fragmenting his wrist and embedding in the thigh, with removed fragments matching the limousine debris.[4] Physical evidence from the limousine included a cracked windshield puncture attributed to a bullet fragment, bullet holes in the interior trim, and trace blood spatter patterns aligning with shots from above and behind.[4] The Commission relied on these elements, supplemented by wound ballistics simulations using gelatin blocks and animal proxies, to validate the rifle's capability for the observed damage at ranges of 175 to 265 feet.[4] Despite the linkages, critics of the Commission's forensic methodology, including subsequent analyses, have pointed to inconsistencies such as the back wound's shallow depth (not traversing fully as initially probed at Parkland) and potential contamination of fragments, underscoring reliance on 1960s-era techniques predating advanced forensic standards.[27]Witness Accounts and Timeline Reconstruction

The Warren Commission gathered affidavits and testimonies from approximately 552 witnesses, including over 100 in Dealey Plaza, to reconstruct the timeline and sequence of the assassination on November 22, 1963. These accounts, supplemented by motion picture films such as Abraham Zapruder's 8-millimeter home movie and police radio logs, established that the presidential motorcade entered Dealey Plaza around 12:30 p.m. Central Standard Time, with shots fired as the limousine traversed Elm Street toward the Triple Underpass. Witnesses like Secret Service agent Rufus W. Youngblood and aide David F. Powers corroborated the 12:30 p.m. timing based on clocks at the Texas School Book Depository and expectations for arrival at the Trade Mart luncheon.[30][30] Eyewitness descriptions of the shots varied in number—most reported two to three fired in rapid succession over 4.8 to 5.6 seconds—but converged on a rifle-like report echoing in the plaza. Governor John Connally, seated ahead of President Kennedy, testified to hearing an initial shot, then feeling struck by a subsequent one in the back, followed by observing the fatal head wound; his wife, Nellie Connally, and driver William Greer described a similar sequence of reactions starting with a "backfire" noise, then slumping and the head shot.[30][30] A majority of witnesses who identified a direction, including those near the grassy knoll and underpass, attributed the sounds to the rear, specifically the sixth floor of the Texas School Book Depository; steamfitter Howard Brennan provided a detailed account of seeing a man aiming and firing a rifle from the Depository's southeast corner window, later identifying Lee Harvey Oswald in a lineup as resembling the shooter.[4][4] The Commission's timeline reconstruction synchronized these testimonies with the Zapruder film, which filmed at 18.3 frames per second and depicted the limousine traveling at 11.2 miles per hour, covering 186 feet in the critical 8.3 seconds (frames 150 to 302). The film showed Kennedy emerging from behind a sign at frame 225 with hands at throat (consistent with a neck wound reaction), Connally twisting at frame 235, and the head shot at frame 313, aligning with witness reports of the first perceptible hit around frames 210-225, a possible missed shot earlier, and the final shot causing forward-then-backward motion.[30][4] Discrepancies arose, such as a minority of witnesses perceiving shots from the grassy knoll (e.g., due to echoes or smoke puffs) or reporting four shots, but the Commission evaluated these against ballistic evidence and found no physical traces—like cartridge cases or positioned snipers—supporting alternative origins, attributing variances to acoustic confusion in the plaza's confines.[4][4]| Key Timeline Elements from Witness and Film Correlation |

|---|

| Event |

| Motorcade departs Love Field |

| Enters Dealey Plaza on Elm Street |

| Shots span |

| Arrives Parkland Hospital |