Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

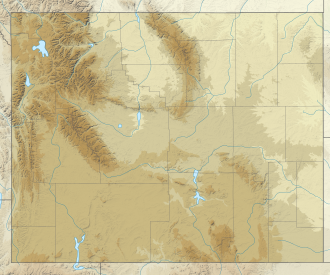

Yellowstone Lake

View on Wikipedia

Yellowstone Lake is the largest body of water in Wyoming and the largest in Yellowstone National Park. The lake is 7,732 feet (2,357 m) above sea level and covers 136 square miles (350 km2) with 110 miles (180 km) of shoreline. While the average depth of the lake is 139 ft (42 m), its greatest depth is at least 394 ft (120 m).[1] Yellowstone Lake is the largest freshwater lake above 7,000 ft (2,100 m) in North America.[2]

Key Information

In winter, ice nearly 3 ft (0.91 m) thick covers much of the lake except where shallow water covers hot springs. The lake freezes over by early December and can remain frozen until late May or early June.

History

[edit]The forest and valleys surrounding Yellowstone Lake have been regularly visited by Native Americans for thousands of years. Various Native cultures hunted bison and bighorn sheep, fished for cutthroat trout, and gathered bitterroot and camas bulbs, since at least 9000 BC. Around 7300 BC, the Cody people camped on the eastern side of Yellowstone Lake during the summers, fishing and boating on the lake, hunting bear, deer, and bison, and obtaining obsidian from Obsidian Cliff.[3] The only Native American pottery found in within present-day Yellowstone National Park was on the western side of Yellowstone Lake, close to the present-day Pumice Point Picnic Area, and dates to 500-1500 AD. It has been linked to the Shoshone tribe.[4]

The first human of European descent known to see the lake is trapper John Colter in the early 19th century. During the fur trading era of 1820–1840, the lake was probably visited by many trapping parties moving through the park region. In trapper Osborne Russell's diary, he describes a visit to the lake in 1836 as follows:

16th [August] -Mr. Bridger came up with the remainder of the party. 18th-The whole camp moved down the east shore of the lake through thick pines and fallen timber about eighteen miles and encamped in a small prairie. 19th-continued down the shore to the outlet about twenty miles, and encamped in a beautiful plain { Hayden Valley } which extended along the northern extremity of the lake. This valley was interspersed with scattering groves of tall pines, forming shady retreats for the numerous elk and deer during the heat of the day. The lake is about 100 miles in circumference, bordered on the east by high ranges of mountains whose spurs terminate at the shore and on the west by a low bed of piney mountains. Its greatest width is about fifteen miles, lying in an oblong from south to north, or rather in the shape of a crescent. Near where we encamped were several hot springs which boiled perpetually. Near these was an opening in the ground about eight inches in diameter from which hot steam issued continually with a noise similar to that made by the steam issuing from the safety valve of an engine, and could be heard five or six miles distant.[5]

Name

[edit]The lake has been known by various names as depicted on early maps and in journals. Both fur trader David Thompson and explorer William Clark referred to the lake as Yellow Stone. Osborne Russell referred to the lake as Yellow Stone Lake in his 1834 journal. On some William Clark maps, the lake has the name Eustis Lake and the name Sublette's Lake was also used to name the lake in the early 19th century. The name Yellowstone Lake appears formally first in the 1839 maps of the Oregon Territory by U.S. Army topographical engineer, Captain Washington Hood and has remained so since that time.[6][7]

Pre-park era exploration

[edit]Although many prospecting parties traversed the Yellowstone region throughout the 1850–60s, the first detailed descriptions of the lake came in 1869, 1870 and 1871 as a result of the Cook–Folsom–Peterson Expedition, the Washburn-Langford-Doane Expedition and the Hayden Geological Survey of 1871.

Cook, Folsom and Peterson first encountered the lake near Pelican Creek 44°33′12″N 110°21′37″W / 44.55333°N 110.36028°W as they moved south along the Yellowstone River on September 24, 1869. They eventually followed the western shoreline to West Thumb before moving west to the geyser basins. Cook described the lake at Pelican Creek as follows:

The main body is ten miles long from east to west and sixteen miles long from north to south, but at the south end it puts out two arms, one to the southeast and the other to the southwest, making the entire length about 30 miles ... There are three small islands which are also heavily timbered ... The shallow water in some of the coves affords feeding ground for thousands of water fowl and we can take our choice of ducks, geese, trout, pelican or swan.[8]

The Washburn party was the first to describe the remote eastern and southern shorelines of the lake. From September 3, 1870, to September 17, 1870, the Washburn party traveled from the outlet of the lake around the northern, eastern, and southern shorelines to West Thumb 44°25′40″N 110°31′57″W / 44.42778°N 110.53250°W. The September 4, 1870 journal entry of Lieutenant Gustavus C. Doane, the leader of the U.S. Army escort during the expedition, describes the lake as follows:

On the south side, these promontories project far into the lake in great numbers, dividing it into bays and channels. On the west side is a low bluff of the timbered ridges, with a sand beach in front along the margins of the waters. The greatest width of open water in any direction is about eighteen miles. Several islands are seen, one of which is opposite the channel of the river and five miles from the east shore; another is ten miles farther south, and two miles from the shore a mountain isle with a bold bluff all around to the water's edge. These islands doubtless have never been trodden by human footsteps, and still belong to the regions of the unexplored. We built a raft for the purpose of attempting to visit them, but the strong waves of the lake dashed it to pieces in an hour. Numerous steam jets pour out from the bluffs on the shore at different points. The waters of the lake reflect a deep blue color, are clear as crystal, and doubtless of great depth near the center. The extreme elevation of this great body of water, 7,714 3/5 feet, is difficult to realize. Place Mount Washington, the pride of New England, with its base at the sea level, at the bottom of the lake, and the clear waters of the latter would roll 2,214 feet above its summit. With the single exception of Lake Titticaeca, Peru, it is the highest great body of water on the globe. No shells of any description are found on the lake shore, nor is there any evidence of the waters ever having stood at a much higher level than the present. Twenty-five feet will cover the whole range of the water-marks. Its annual rise and falls are about two feet. Its waters abound with trout to such an extent that the fish at this season are in poor condition, for want of food. No other fish are seen; no minnows, and no small trout. There are also no clams, crabs, nor turtles -- nothing but full-grown trout. These could be caught in mule loads by wading out a few feet in the open waters at any point with a grasshopper bait. Two men could catch them faster than half a dozen could clean and get them ready for the frying pan. Caught in the open lake, their flesh was yellow; but in bays, where the water was strongly impregnated with chemicals, it was blood-red. Many of them were full of long white worms, woven across the interior of the body, and through to the skin on either side. These did not appear to materially affect the condition of the fish, which were apparently as active as the others.[10]

The Hayden Geological Survey of 1871 provided the most detailed and scientific descriptions of the lake in the pre-park era. The Hayden party, 34 men in all, encountered the lake at the outlet on July 28, 1871, spending two days there and returned to the lake at West Thumb on August 7, 1871. From West Thumb, the survey party took 15 days to explore the southern and eastern flanks of the lake. On July 28, 1871, they launched Annie, the first European boat ever to sail on the lake and began exploring the islands and shoreline. Additionally, the first ever photographs of the lake were taken during this expedition by William Henry Jackson.

In correspondence that was Hayden's Report No. 7 to Assistant Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, Dr. Spencer Baird, a bit of which is excerpted below, Dr. Ferdinand V. Hayden described some of the explorations being conducted on the lake as follows:

Yellowstone Lake, WY August 8th, 1871 - Dear Professor Baird, Your letters of June 6th and July 3rd were brought us from Fort Ellis by Lt. Doane who has just arrived to take command of our escort and accompany my party the remainder of the season ... We arrived at the banks of the Yellow Stone Lake [sic] July 26th [actually July 28] and pitched our camp near the point where the river leaves the Lake. Hence we brought the first pair of wheels that ever came to the Lake with our Odometer. We launched the first Boat on the Lake, 4.5 feet wide and 11 feet long, with sails and oars ... A chart of this soundings will be made. Points have been located with a prismatic compass all around the Lake. A man stands on the shore with a compass and takes a bearing to the man in the Boat as he drops the lead, giving a signal at the time. Then a man in the Boat takes a bearing to the fixed point on the shore where the first man is located and thus the soundings will be located on the chart. Henry Elliot and Mr. Carrington have just left in our little boat, the Annie. [They] will make a systematic sketch of the shore with all its indentations, with the banks down, indeed, making a complete topographical as well as a pictorial sketch of the shores as seen from the water, for a circuit--of at least 130 miles ... One of the islands has been explored. We have called it Stevenson's Island as he was undoubtedly the first human that ever set foot upon it ... Write at once. Yours Truly, F. V. Hayden, I will send you some Photographs soon.[11]

Proposals to dam the lake

[edit]Between 1920 and 1937, multiple proposals were made to Congress and the Department of the Interior to construct dams of various sizes at the Yellowstone Lake outlet or a few miles downstream. Montana and Wyoming politicians, the Army Corps of Engineers and lobbying groups in both states all had a variety of reasons to support the dams—flood control in the Yellowstone Valley, reclamation, or diversion of water over the continental divide to the Snake River. All the proposals and legislation were eventually defeated.[12]

Geology

[edit]

In the southwest area of the lake, the West Thumb Geyser Basin is easily accessible to visitors. Geysers, fumaroles, and hot springs are found both alongside and in the lake.

As of 2004, the ground under the lake has started to rise significantly, indicating increased geological activity, and limited areas of the national park have been closed to the public. As of 2005, no areas are currently off limits aside from those normally allowing limited access such as around the West Thumb Geyser Basin. There is a "bulge" about 2,000 ft (610 m) long and 100 ft (30 m) high under a section of Yellowstone Lake, where there are a variety of faults, hot springs and small craters. Seismic imaging has recently shown that sediment layers are tilted, but how old this feature is has not yet been established.

After the magma chamber under the Yellowstone area collapsed 640,000 years ago in its previous great eruption, it formed a large caldera that was later partially filled by subsequent lava flows (see Yellowstone Caldera). Part of this caldera is the 136 sq mi (350 km2) basin of Yellowstone Lake. The original lake was 200 ft (61 m) higher than the present-day lake, extending northward across Hayden Valley to the base of Mount Washburn.

It is thought that Yellowstone Lake originally drained south into the Pacific Ocean via the Snake River. The lake currently drains north from its only outlet, the Yellowstone River, at Fishing Bridge. The elevation of the lake's north end does not drop substantially until LeHardy Rapids. Therefore, this spot is considered the actual northern boundary of Yellowstone Lake. Within a short distance downstream the Yellowstone River plunges first over the upper and then the lower falls and races north through the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone.

In the 1990s, geological research determined that the two volcanic vents, now known as "resurgent domes", are rising again. From year to year, they either rise or fall, with an average net uplift of about one inch per year. During the period between 1923 and 1985, the Sour Creek Dome was rising. In the years since 1986, it has either declined or remained the same. The resurgence of the Sour Creek dome, just north of Fishing Bridge is causing Yellowstone Lake to "tilt" southward. Larger sandy beaches can now be found on the north shore of the lake, and flooded areas can be found in the southern arms.[13]

The Hayden Valley was once filled by an arm of Yellowstone Lake. As a result, it contains fine-grained lake sediments that are now covered with glacial till left from the most recent glacial retreat 13,000 years ago. Because the glacial till contains many different grain sizes, including clay and a thin layer of lake sediments, water cannot percolate readily into the ground. This is why the Hayden Valley is marshy and has little encroachment of trees.

Ecology

[edit]Fish

[edit]Non-native lake trout were discovered in Yellowstone Lake in 1994,[14] and were believed to have been either accidentally or intentionally introduced as early as 1989 with fish taken from Lewis Lake. The introduction of Lake trout has caused a serious decline in the cutthroat trout population and the National Park Service has an aggressive Lake trout eradication program on the lake.[15] All lake trout caught by anglers must be killed.[16] If the cutthroat trout isn’t protected from this invasive fish then ecologist predict that they could see a decline in surrounding birds and mammals that are natural predators to the cutthroat trout.[17] The longnose sucker is an invasive fish that was believed to be introduced into the Yellowstone Lake in the late 1980s or early 1990s. With this foreign species in the Lake researchers have noticed a shift in the food chain. They have seen a rapid decline in the population of the cutthroat trout which in turn could cause other animal populations to start declining. One study found that the introduced longnose sucker competes with cutthroat trout for some of the same food sources.[18]

The declining population of cutthroat trout in the Yellowstone Lake can negatively impact fish predators. One in particular is the North American river otter which relies on the cutthroat fish as a prey. With a declining number of cutthroat trout in the spawning streams researchers saw a shift in the relationship between terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems that are linked together. [19]

Other animals

[edit]Yellowstone is home to a large concentration of mammals. Whether that be large mammals such as bison, elk, or bighorn sheep there is a variety of different animals that are native to the Yellowstone area. On the other hand Yellowstone is also home to many smaller animals, and a few that are constantly around the lake are beavers, short tailed weasels, and river otters which have previously been mentioned.[20]

Climate

[edit]Yellowstone Lake has a subarctic climate (Köppen Dfc).

| Climate data for Yellowstone Lake, Wyoming, 1991–2020 normals, 1998–2024 extremes: 7835ft (2388m) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 42 (6) |

55 (13) |

57 (14) |

65 (18) |

78 (26) |

83 (28) |

86 (30) |

86 (30) |

83 (28) |

74 (23) |

57 (14) |

46 (8) |

86 (30) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 35.0 (1.7) |

39.1 (3.9) |

48.5 (9.2) |

56.6 (13.7) |

67.1 (19.5) |

77.0 (25.0) |

82.5 (28.1) |

81.0 (27.2) |

75.8 (24.3) |

62.5 (16.9) |

48.3 (9.1) |

36.3 (2.4) |

81.0 (27.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 23.0 (−5.0) |

26.1 (−3.3) |

34.7 (1.5) |

40.9 (4.9) |

50.6 (10.3) |

61.1 (16.2) |

72.2 (22.3) |

70.7 (21.5) |

60.5 (15.8) |

45.5 (7.5) |

32.0 (0.0) |

23.3 (−4.8) |

45.0 (7.2) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 12.0 (−11.1) |

13.5 (−10.3) |

21.2 (−6.0) |

28.7 (−1.8) |

38.4 (3.6) |

47.0 (8.3) |

55.5 (13.1) |

53.9 (12.2) |

45.4 (7.4) |

33.6 (0.9) |

21.5 (−5.8) |

13.0 (−10.6) |

32.0 (0.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 1.0 (−17.2) |

0.9 (−17.3) |

7.7 (−13.5) |

16.6 (−8.6) |

26.3 (−3.2) |

33.0 (0.6) |

38.7 (3.7) |

37.0 (2.8) |

30.3 (−0.9) |

21.8 (−5.7) |

11.0 (−11.7) |

2.7 (−16.3) |

18.9 (−7.3) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −22.0 (−30.0) |

−25.3 (−31.8) |

−15.2 (−26.2) |

−4.4 (−20.2) |

13.3 (−10.4) |

25.4 (−3.7) |

32.4 (0.2) |

29.5 (−1.4) |

22.2 (−5.4) |

6.2 (−14.3) |

−8.9 (−22.7) |

−20.0 (−28.9) |

−30.7 (−34.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −42 (−41) |

−38 (−39) |

−34 (−37) |

−18 (−28) |

0 (−18) |

21 (−6) |

27 (−3) |

25 (−4) |

13 (−11) |

−16 (−27) |

−23 (−31) |

−36 (−38) |

−42 (−41) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.80 (46) |

1.70 (43) |

1.90 (48) |

2.28 (58) |

2.35 (60) |

2.38 (60) |

1.51 (38) |

1.34 (34) |

1.57 (40) |

1.85 (47) |

2.06 (52) |

2.35 (60) |

23.09 (586) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 35.8 (91) |

30.9 (78) |

25.1 (64) |

22.9 (58) |

6.9 (18) |

1.0 (2.5) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.4 (3.6) |

10.2 (26) |

29.8 (76) |

35.4 (90) |

199.4 (507.1) |

| Average extreme snow depth inches (cm) | 37 (94) |

45 (110) |

48 (120) |

43 (110) |

22 (56) |

1 (2.5) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (2.5) |

4 (10) |

13 (33) |

26 (66) |

50 (130) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 16.1 | 14.3 | 16.4 | 15.8 | 14.9 | 12.3 | 9.5 | 9.4 | 9.1 | 13.3 | 13.0 | 16.1 | 160.2 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 16.3 | 14.4 | 12.3 | 10.2 | 4.3 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 5.5 | 11.8 | 15.4 | 91.8 |

| Source 1: NOAA[21][22] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: XMACIS2 (records, monthly max/mins & 1991-2020 snow depth)[23] | |||||||||||||

Angling and boating

[edit]

Angling for Yellowstone cutthroat trout in Yellowstone Lake has been a popular pastime for both subsistence and recreation since the first explorers, surveyors and tourists visited the park. During the early days of fish stocking in Yellowstone (1890–1910), Atlantic Salmon, Mountain whitefish, and Rainbow trout were stocked in the lake; none of these introduced species survived.[24] Today only native cutthroat and non-native lake trout and Longnose sucker exist in the lake.[25] Today, Yellowstone Lake is open for angling during the entire Yellowstone angling season (Memorial Day weekend thru Oct 31). All Cutthroat trout caught must be released.

Recreational boating has been permitted on the lake in various forms since 1890 when the first permits for the Yellowstone Boat Company were issued to operate a ferry across the lake between road junctions.[26] Today, powerboats, sailboats, canoes and kayaks are allowed on the lake with a Yellowstone Boating Permit. A Marina is operated at Bridge Bay and there is a boat ramp at Grant Village on the West Thumb. Areas in the southern arms of the lake are speed-restricted and/or no-motor zones to protect sensitive wildlife areas. Access to some of the lake's islands is also restricted.[27] Xanterra Parks and Resorts at Bridge Bay Marina on Yellowstone Lake provides boat rentals and other boating services. Numerous outfitters operating outside the park are licensed to provide boating services in the park. Several dozen backcountry campsites line the southern shoreline that is accessible only by boat. Two major hiking trails provide access to the lake shore away from the major road. The Nine Mile Post trail hugs the eastern shoreline into the Thorofare region and intersects with the Trail Creek and Heart Lake trails that touch the ends of both the south and southeast arms of the lake.[28]

-

Yellowstone Lake's outlet (1871)

-

The southwest arm of Yellowstone Lake looking north (1871)

-

The eastern shoreline of Yellowstone Lake (1878)

-

A photo of boats on Yellowstone Lake by F. Jay Haynes

-

A scenic photo of Yellowstone Lake by Ansel Adams (1942)

-

Yellowstone Lake as seen from Two Ocean Plateau looking north (1963)

-

Yellowstone Lake Hotel as seen from Yellowstone Lake

-

A rainbow hanging over Yellowstone Lake

-

Yellowstone Lake on a stormy day

-

Yellowstone Lake at dawn

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Yellowstone Lake". National Park Service. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ "Yellowstone Lake". National Park Service. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ Johnson, Ann M.; Reeves, Brian O.K. (August 2013). "Summer on Yellowstone Lake 9,300 Years Ago: The Osprey Beach Site". Plains Anthropologist. 58 (227–228): 1–194. doi:10.1080/00320447.2013.11735767.

- ^ MacDonald, Douglas H. (2018). Before Yellowstone : Native American archaeology in the national park. Seattle. p. 208. ISBN 9780295742205.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Russell, Osborne (1921). Journal of a Trapper-Nine Years in the Rocky Mountains (1834-1843). Boise, ID: Syms-York Company Inc. pp. 49.

- ^ Haines, Aubrey L. (1996). Yellowstone Place Names-Mirrors of History. Niwot, CO: University Press of Colorado. pp. 4–5. ISBN 0-87081-383-8.

- ^ Pierre-Jean de Smet; Hiram Martin Chittenden; Alfred Talbot Richardson (1905). "IX-II - The Missouri River". Life, Letters and Travels of Father Pierre-Jean de Smet, S.J., 1801-1873: Missionary labors and adventures among the wild tribes of the North American Indians ... Vol. 04 (1st ed.). New York: F.P. Harper. p. 1377. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ^ Cook, Charles W.; Folsom, Dave E.; Peterson, William (1965). Haines, Aubrey L. (ed.). The Valley of the Upper Yellowstone-An Exploration of the Headwaters of the Yellowstone River in the Year 1869. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 36.

- ^ Langford, Nathaniel Pitt (1905). The Discovery of Yellowstone Park; Diary of the Washburn Expedition to the Yellowstone and Firehole Rivers in the Year 1870. St. Paul, MN: Frank Jay Haynes. pp. 64.

- ^ The report of Lieutenant Gustavus C. Doane upon the so-called Yellowstone Expedition of 1870, presented to the Secretary of War, February 1871

- ^ Merrill, Marlene Deahl, ed. (1999). Yellowstone and the Great West-Journals, Letters and Images from the 1871 Hayden Expedition. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 152–154. ISBN 0-8032-3148-2.

- ^ Bartlett, Richard A. (1985). "The Great Reclamation Raids". Yellowstone=A Wilderness Besieged. Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona Press. pp. 347–358. ISBN 0-8165-1098-9.

- ^ "Lake Area Geologic Highlights". National Park Service. Archived from the original on August 19, 2007. Retrieved 2014-02-26.

- ^ "Illegal lake trout threaten native species in Yellowstone". Spokesman-Review. Spokane, Washington. Associated Press. August 13, 1994. p. B5.

- ^ Munro, Andrew R.; Thomas E. McMahon; James R. Ruzycki (Spring 2006). "Source and Date of Lake Trout Introduction" (PDF). Yellowstone Science. 14 (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 21, 2008.

- ^ Park, Mailing Address: PO Box 168 Yellowstone National; Us, WY 82190-0168 Phone: 307-344-7381 Contact. "Catch a Fish - Yellowstone National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ The Yellowstone Lake crisis : confronting a lake trout invasion : a report to the director of the National Park Service / edited by John D. Varley and Paul Schullery (PDF). Yellowstone National Park, WYO. 1995. p. 36. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Furey, Kaitlyn M.; Glassic, Hayley C.; Guy, Christopher S.; Koel, Todd M.; Arnold, Jeffrey L.; Doepke, Philip D.; Bigelow, Patricia E. (2020). "Diets of longnose sucker in Yellowstone Lake, Yellowstone National Park, USA". Journal of Freshwater Ecology. 35 (1): 291–303. Bibcode:2020JFEco..35..291F. doi:10.1080/02705060.2020.1807421. S2CID 225363971.

- ^ Crait, Jamie R.; Ben-David, Merav (2006). "River Otters in Yellowstone Lake Depend on a Declining Cutthroat Trout Population". Journal of Mammalogy. 87 (3): 485–494. doi:10.1644/05-MAMM-A-205R1.1. JSTOR 4094505. S2CID 86175541.

- ^ Park, Mailing Address: PO Box 168 Yellowstone National; Us, WY 82190-0168 Phone: 307-344-7381 Contact. "Mammals - Yellowstone National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Yellowstone Lake, Wyoming 1991-2020 Monthly Normals". Retrieved October 18, 2023.

- ^ "Lake Yellowstone, Wyoming 1991-2020 Monthly Normals". Retrieved March 15, 2024.

- ^ "xmACIS". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 15, 2024.

- ^ Franke, Mary Ann (Fall 1996). "A Grand Experiment-100 Years of Fisheries Management in Yellowstone: Part I". Yellowstone Science. 4 (4).

- ^ 2023 Yellowstone National Park Fishing Regulations[dead link]

- ^ Culpin, Mary Shivers (2003). For the Benefit and Enjoyment of the People: A History of Concession Development in Yellowstone National Park-1872-1966. Yellowstone National Park, WY: Yellowstone Center for Resources. Archived from the original on August 9, 2007.

- ^ Yellowstone National Park Boating Regulations

- ^ Yellowstone National Park Backcountry Trip Planner

External links

[edit]- USGS answers questions about the 'bulge' under Yellowstone Lake. Archived 2012-02-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Bathymetry and Geology of the Floor of Yellowstone Lake, Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana - United States Geological Survey

![]() Media related to Yellowstone Lake at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Yellowstone Lake at Wikimedia Commons

Yellowstone Lake

View on GrokipediaYellowstone Lake is a large freshwater body located at 7,733 feet (2,357 meters) above sea level within Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming, United States, and constitutes the largest high-elevation lake in North America above 7,000 feet (2,134 meters).[1][2] It spans approximately 341 square kilometers (132 square miles), reaches a maximum depth of 410 feet (125 meters), and holds an estimated 12,095,264 acre-feet of water.[2][3] The lake's irregular shape includes several arms and bays, with its outlet forming the headwaters of the Yellowstone River.[1] Geologically, Yellowstone Lake occupies a basin shaped by the interplay of volcanic lava flows within the Yellowstone Caldera, glacial erosion, and recurrent hydrothermal explosions over the past 14,000 years, resulting in a dynamic seafloor marked by over 660 hydrothermal vents and large explosion craters up to 2,500 meters in diameter.[4][5][6] These features underscore the lake's position atop an active volcanic system, where subsurface heat drives extensive geothermal activity, including submarine hot springs and geysers.[7] Ecologically, the lake sustains North America's largest population of wild Yellowstone cutthroat trout, a keystone species integral to the park's food web, though this native fishery faces ongoing disruption from invasive lake trout, prompting sustained management efforts to restore balance.[1][8] The lake's pristine aquatic environment, combined with its scenic and scientific value, draws researchers studying volcanic-tectonic interactions and serves as a focal point for conservation amid broader ecosystem dynamics in the Greater Yellowstone region.[9]

Physical Characteristics

Location and Dimensions

Yellowstone Lake occupies the central region of Yellowstone National Park in northwestern Wyoming, United States, primarily within Teton County, at approximate coordinates 44°25′N 110°25′W.[1] The lake lies at an elevation of 7,733 feet (2,357 m) above sea level, positioning it as North America's largest body of water exceeding 7,000 feet (2,134 m) in elevation.[1] The lake spans a surface area of 131.7 to 139 square miles (341 to 360 km²), varying with seasonal water levels, and measures roughly 20 miles (32 km) in maximum length by 14 miles (23 km) in maximum width.[1][10] It possesses 141 miles (227 km) of irregular shoreline, shaped by volcanic terrain and glacial influences.[1] The average water depth stands at 138 feet (42 m), with a recorded maximum depth of 430 feet (131 m) in its deepest basin.[10]