Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Adoption

View on Wikipedia

Adoption is a process whereby a person assumes the parenting of another, usually a child, from that person's biological or legal parent or parents. Legal adoptions permanently transfer all rights and responsibilities, along with filiation, from the biological parents to the adoptive parents.

Unlike guardianship or other systems designed for the care of the young, adoption is intended to effect a permanent change in status and as such requires societal recognition, either through legal or religious sanction. Historically, some societies have enacted specific laws governing adoption, while others used less formal means (notably contracts that specified inheritance rights and parental responsibilities without an accompanying transfer of filiation). Modern systems of adoption, arising in the 20th century, tend to be governed by comprehensive statutes and regulations.

History

[edit]Antiquity

[edit]Adoption for the well-born

[edit]

While the modern form of adoption emerged in the United States, forms of the practice appeared throughout history. The Code of Hammurabi, for example, details the rights of adopters and the responsibilities of adopted individuals at length. The practice of adoption in ancient Rome is well-documented in the Codex Justinianus.[1][2]

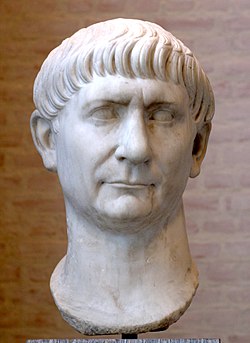

Markedly different from the modern period, ancient adoption practices put emphasis on the political and economic interests of the adopter,[3] providing a legal tool that strengthened political ties between wealthy families and created male heirs to manage estates.[4][5] The use of adoption by the aristocracy is well-documented: many of Rome's emperors were adopted sons.[5] Adrogation was a kind of Roman adoption in which the person adopted consented to be adopted by another. Some adoptions were even posthumous.

Infant adoption during Antiquity appears rare.[3][6] Abandoned children were often picked up for slavery[7] and composed a significant percentage of the Empire's slave supply.[8][9] Roman legal records indicate that foundlings were occasionally taken in by families and raised as a son or daughter. Although not normally adopted under Roman Law, the children, called alumni, were reared in an arrangement similar to guardianship, being considered the property of the father who abandoned them.[10]

Other ancient civilizations, notably India and China, used some form of adoption as well. Evidence suggests the goal of this practice was to ensure the continuity of cultural and religious practices; in contrast to the Western idea of extending family lines. In ancient India, adoption was conducted in a limited and highly ritualistic form, so that an adopter might have the necessary funerary rites performed by a son.[11] China had a similar idea of adoption with males adopted solely to perform the duties of ancestor worship.[12]

The practice of adopting the children of family members and close friends was common among the cultures of Polynesia including Hawaii where the custom was referred to as hānai.

Middle ages to modern period

[edit]Adoption and commoners

[edit]

The nobility of the Germanic, Celtic, and Slavic cultures that dominated Europe after the decline of the Roman Empire denounced the practice of adoption.[13] In medieval society, bloodlines were paramount; a ruling dynasty lacking a "natural-born" heir apparent was replaced, a stark contrast to Roman traditions. The evolution of European law reflects this aversion to adoption. English common law, for instance, did not permit adoption since it contradicted the customary rules of inheritance. In the same vein, France's Napoleonic Code made adoption difficult, requiring adopters to be over the age of 50, sterile, older than the adopted person by at least 15 years, and to have fostered the adoptee for at least six years.[14] Some adoptions continued to occur, however, but became informal, based on ad hoc contracts. For example, in the year 737, in a charter from the town of Lucca, three adoptees were made heirs to an estate. Like other contemporary arrangements, the agreement stressed the responsibility of the adopted rather than adopter, focusing on the fact that, under the contract, the adoptive father was meant to be cared for in his old age; an idea that is similar to the conceptions of adoption under Roman law.[15]

Europe's cultural makeover marked a period of significant innovation for adoption. Without support from the nobility, the practice gradually shifted toward abandoned children. Abandonment levels rose with the fall of the empire and many of the foundlings were left on the doorstep of the Church.[16] Initially, the clergy reacted by drafting rules to govern the exposing, selling, and rearing of abandoned children. The Church's innovation, however, was the practice of oblation, whereby children were dedicated to lay life within monastic institutions and reared within a monastery. This created the first system in European history in which abandoned children did not have legal, social, or moral disadvantages. As a result, many of Europe's abandoned and orphaned children became alumni of the Church, which in turn took the role of adopter. Oblation marks the beginning of a shift toward institutionalization, eventually bringing about the establishment of the foundling hospital and orphanage.[16]

As the idea of institutional care gained acceptance, formal rules appeared about how to place children into families: boys could become apprenticed to an artisan and girls might be married off under the institution's authority.[17] Institutions informally adopted out children as well, a mechanism treated as a way to obtain cheap labor, demonstrated by the fact that when the adopted died their bodies were returned by the family to the institution for burial.[18]

This system of apprenticeship and informal adoption extended into the 19th century, today seen as a transitional phase for adoption history. Under the direction of social welfare activists, orphan asylums began to promote adoptions based on sentiment rather than work; children were placed out under agreements to provide care for them as family members instead of under contracts for apprenticeship.[19] The growth of this model is believed to have contributed to the enactment of the first modern adoption law in 1851 by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, unique in that it codified the ideal of the "best interests of the child".[20][21] Despite its intent, though, in practice, the system operated much the same as earlier incarnations. The experience of the Boston Female Asylum (BFA) is a good example, which had up to 30% of its charges adopted out by 1888.[22] Officials of the BFA noted that, although the asylum promoted otherwise, adoptive parents did not distinguish between indenture and adoption: "We believe," the asylum officials said, "that often, when children of a younger age are taken to be adopted, the adoption is only another name for service."[23]

Modern period

[edit]Adopting to create a family

[edit]The next stage of adoption's evolution fell to the emerging nation of the United States. Rapid immigration and the American Civil War resulted in unprecedented overcrowding of orphanages and foundling homes in the mid-nineteenth century. Charles Loring Brace, a Protestant minister, became appalled by the legions of homeless waifs roaming the streets of New York City. Brace considered the abandoned youth, particularly Catholics, to be the most dangerous element challenging the city's order.[24][25] His solution was outlined in The Best Method of Disposing of Our Pauper and Vagrant Children (1859), which started the Orphan Train movement. The orphan trains eventually shipped an estimated 200,000 children from the urban centers of the East to the nation's rural regions.[26] The children were generally indentured, rather than adopted, to families who took them in.[27] As in times past, some children were raised as members of the family while others were used as farm laborers and household servants. The sheer size of the displacement—one of the largest migrations of children in history—and the degree of exploitation that occurred, gave rise to new agencies and a series of laws that promoted adoption arrangements rather than indenture. The hallmark of the period is Minnesota's adoption law of 1917, which mandated investigation of all placements and limited record access to those involved in the adoption.[28][29]

During the same period, the Progressive movement swept the United States with a critical goal of ending the prevailing orphanage system. The culmination of such efforts came with the First White House Conference on the Care of Dependent Children called by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1909,[30] where it was declared that the nuclear family represented "the highest and finest product of civilization" and was best able to serve as primary caretaker for the abandoned and orphaned.[31][32] As late as 1923, only two percent of children without parental care were in adoptive homes, with the balance in foster arrangements and orphanages. Less than forty years later, nearly one-third were in adoptive homes.[33]

Nevertheless, the popularity of eugenic ideas in America put up obstacles to the growth of adoption.[34][35] There were grave concerns about the genetic quality of illegitimate and indigent children, perhaps best exemplified by the influential writings of Henry H. Goddard, who protested against adopting children of unknown origin, saying,

Now it happens that some people are interested in the welfare and high development of the human race; but leaving aside those exceptional people, all fathers and mothers are interested in the welfare of their own families. The dearest thing to the parental heart is to have the children marry well and rear a noble family. How short-sighted it is then for such a family to take into its midst a child whose pedigree is absolutely unknown; or, where, if it were partially known, the probabilities are strong that it would show poor and diseased stock, and that if a marriage should take place between that individual and any member of the family the offspring would be degenerates.[36]

The period 1945 to 1974, the baby scoop era, saw rapid growth and acceptance of adoption as a means to build a family.[37] Illegitimate births rose three-fold after World War II, as sexual mores changed. Simultaneously, the scientific community began to stress the dominance of nurture over genetics, chipping away at eugenic stigmas.[38][39] In this environment, adoption became the obvious solution for infertile couples.[40] Many of the mothers, however, were forced or coerced into relinquishing their children.

Taken together, these trends resulted in a new American model for adoption. Following its Roman predecessor, Americans severed the rights of the original parents while making adopters the new parents in the eyes of the law. Two innovations were added: 1) adoption was meant to ensure the "best interests of the child", the seeds of this idea can be traced to the first American adoption law in Massachusetts,[14][21] and 2) adoption became infused with secrecy, eventually resulting in the sealing of adoption and original birth records by 1945. The origin of the move toward secrecy began with Charles Loring Brace, who introduced it to prevent children from the Orphan Trains from returning to or being reclaimed by their parents. Brace feared the impact of the parents' poverty, in general, and Catholic religion, in particular, on the youth. This tradition of secrecy was carried on by the later Progressive reformers when drafting of American laws.[41]

The number of adoptions in the United States peaked in 1970.[42] The years of the late 1960s and early 1970s saw a dramatic change in society's view of illegitimacy and in the legal rights[43] of those born outside of wedlock. In response, family preservation efforts grew[44] so that few children born out of wedlock today are adopted. Ironically, adoption is far more visible and discussed in society today, yet it is less common.[45]

The American model of adoption eventually proliferated globally. England and Wales established their first formal adoption law in 1926. The Netherlands passed its law in 1956. Sweden made adoptees full members of the family in 1959. West Germany enacted its first laws in 1977.[46] Additionally, the Asian powers opened their orphanage systems to adoption, influenced as they were by Western ideas following colonial rule and military occupation.[47] In France, local public institutions accredit candidates for adoption, who can then contact orphanages abroad or ask for the support of NGOs. The system does not involve fees, but gives considerable power to social workers whose decisions may restrict adoption to "standard" families (middle-age, medium to high income, heterosexual, Caucasian).[48]

Adoption is today practiced globally. The table below provides a snapshot of Western adoption rates. Adoption in the United States still occurs at rates nearly three times those of its peers even though the number of children awaiting adoption has held steady in recent years, between 100,000 and 125,000 during the period 2009 to 2018.[49]

| Country | Adoptions | Live births | Adoption/live birth ratio | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 270 (2007–2008)[50] | 254,000 (2004)[51] | 0.2 per 100 live births | Includes known relative adoptions |

| England & Wales | 4,764 (2006)[52] | 669,601 (2006)[53] | 0.7 per 100 live births | Includes all adoption orders in England and Wales |

| Germany | 3,601 (2023)[54] | 692,989 (2023)[55] | 0.5 per 100 live births | Includes 2764 family and stepparent adoptions |

| Iceland | between 20 and 35 year[56] | 4,560 (2007)[57] | 0.8 per 100 live births | |

| Ireland | 263 (2003)[58] | 61,517 (2003)[59] | 0.4 per 100 live births | 92 non-family adoptions; 171 family adoptions (e.g. stepparent). Not included: 459 international adoptions were also recorded. |

| Italy | 3,158 (2006)[60] | 560,010 (2006)[61] | 0.6 per 100 live births | |

| New Zealand | 154 (2012/13) [62] | 59,863 (2012/13) [63] | 0.26 per 100 live births | Breakdown: 50 non-relative, 50 relative, 17 step-parent, 12 surrogacy, 1 foster parent, 18 international relative, 6 international non-relative |

| Norway | 657 (2006)[64] | 58,545 (2006)[65] | 1.1 per 100 live births | Adoptions breakdown: 438 inter-country; 174 stepchildren; 35 foster; 10 other. |

| Sweden | 327 (2023)[66] | 100,051 (2023)[67] | 0.3 per 100 live births | Includes 84 international adoptions |

| United States | approx 136,000 (2008)[68] | 3,978,500 (2015)[69] | ≈3 per 100 live births | The number of adoptions is reported to be constant since 1987. Since 2000, adoption by type has generally been approximately 15% international adoptions, 40% from government agencies responsible for child welfare, and 45% other, such as voluntary adoptions through private adoption agencies or by stepparents and other family members.[68] |

Contemporary adoption

[edit]Forms of adoption

[edit]Contemporary adoption practices can be open or closed.

- Open adoption allows identifying information to be communicated between adoptive and biological parents and, perhaps, interaction between kin and the adopted person.[70] Open adoption can be an informal arrangement subject to termination by adoptive parents who have sole custody over the child. In some jurisdictions, the biological and adoptive parents may enter into a legally enforceable and binding agreement concerning visitation, exchange of information, or other interaction regarding the child.[71] As of February 2009, 24 U.S. states allowed legally enforceable open adoption contract agreements to be included in the adoption finalization.[72]

- The practice of closed adoption (also called confidential or secret adoption),[73] which has not been the norm for most of modern history,[74] seals all identifying information, maintaining it as secret and preventing disclosure of the adoptive parents', biological kin's, and adoptees' identities. Nevertheless, closed adoption may allow the transmittal of non-identifying information such as medical history and religious and ethnic background.[75] Today, as a result of safe haven laws passed by some U.S. states, secret adoption is seeing renewed influence. In so-called "safe-haven" states, infants can be left anonymously at hospitals, fire departments, or police stations within a few days of birth, a practice criticized by some adoption advocacy organizations as being retrograde and dangerous.[76]

How adoptions originate

[edit]

Adoptions can occur between related or unrelated individuals. Historically, most adoptions occurred within a family. The most recent data from the U.S. indicates that about half of adoptions are currently between related individuals.[77] A common example of this is a "step-parent adoption", where the new partner of a parent legally adopts a child from the parent's previous relationship. Intra-family adoption can also occur through surrender, as a result of parental death, or when the child cannot otherwise be cared for and a family member agrees to take over.

Adoption is not always a voluntary process. In some countries, for example in the U.K., one of the main origins of children being placed for adoption is that they have been removed from the birth home, often by a government body such as the local authority. There are a number of reasons why children are removed including abuse and neglect, which can have a lasting impact on the adoptee. Social workers in many cases will be notified of a safeguarding concern in relation to a child and will make enquiries into the child's well-being. Social workers will often seek means of keeping a child together with the birth family, for example, by providing additional support to the family before considering removal of a child. A court of law will often then make decisions regarding the child's future, for example, whether they can return to the birth family, enter into foster care or be adopted.

Infertility is the main reason parents seek to adopt children they are not related to. One study shows this accounted for 80% of unrelated infant adoptions and half of adoptions through foster care.[78] Estimates suggest that 11–24% of Americans who cannot conceive or carry to term attempt to build a family through adoption, and that the overall rate of never-married American women who adopt is about 1.4%.[79][80] Other reasons people adopt are numerous although not well documented. These may include wanting to cement a new family following divorce or death of one parent, compassion motivated by religious or philosophical conviction, to avoid contributing to overpopulation out of the belief that it is more responsible to care for otherwise parent-less children than to reproduce, to ensure that inheritable diseases (e.g., Tay–Sachs disease) are not passed on, and health concerns relating to pregnancy and childbirth. Although there are a range of reasons, the most recent study of experiences of women who adopt suggests they are most likely to be 40–44 years of age, to be currently married, to have impaired fertility, and to be childless.[81]

Unrelated adoptions may occur through the following mechanisms:

- Private domestic adoptions: under this arrangement, not-for-profit organizations and for-profit organizations act as intermediaries, bringing together prospective adoptive parents with families who want to place a child, all parties being residents of the same country. Alternatively, prospective adoptive parents sometimes avoid intermediaries and connect with women directly, often with a written contract; this is not permitted in some jurisdictions. Private domestic adoption accounts for a significant portion of all adoptions; in the United States, for example, nearly 45% of adoptions are estimated to have been arranged privately.[82]

- Foster care adoption: this is a type of domestic adoption where a child is initially placed in public care. Many times the foster parents take on the adoption when the children become legally free. Its importance as an avenue for adoption varies by country. Of the 127,500 adoptions in the U.S. in 2000,[82] about 51,000 or 40% were through the foster care system.[83]

- International adoption: this involves the placing of a child for adoption outside that child's country of birth. This can occur through public or private agencies. In some countries (such as Sweden for much of the 20th century[84]), these adoptions account for the majority of cases. The U.S. example, however, indicates there is wide variation by country since adoptions from abroad account for less than 15% of its cases.[82] More than 60,000 Russian children have been adopted in the United States since 1992,[85] and a similar number of Chinese children were adopted from 1995 to 2005.[86] The laws of different countries vary in their willingness to allow international adoptions. Recognizing the difficulties and challenges associated with international adoption, and in an effort to protect those involved from the corruption and exploitation which sometimes accompanies it, the Hague Conference on Private International Law developed the Hague Adoption Convention, which came into force on 1 May 1995 and has been ratified by 105 countries as of February 2024.[87]

- Embryo adoption: based on the donation of embryos remaining after one couple's in vitro fertilization treatments have been completed; embryos are given to another individual or couple, followed by the placement of those embryos into the recipient woman's uterus, to facilitate pregnancy and childbirth. In the United States, embryo adoption is governed by property law rather than by the court systems, in contrast to traditional adoption.

- Common law adoption: this is an adoption that has not been recognized beforehand by the courts, but where a parent, without resorting to any formal legal process, leaves his or her children with a friend or relative for an extended period of time.[88][89] At the end of a designated term of (voluntary) co-habitation, as witnessed by the public, the adoption is then considered binding, in some courts of law, even though not initially sanctioned by the court. The particular terms of a common-law adoption are defined by each legal jurisdiction. For example, the U.S. state of California recognizes common law relationships after co-habitation of 2 years. The practice is called "private fostering" in Britain.[90]

Disruption and dissolution

[edit]Although adoption is often described as forming a "forever" family, the relationship can be ended at any time. The legal termination of an adoption is called disruption. In U.S. terminology, adoptions are disrupted if they are ended before being finalized, and they are dissolved if the relationship is ended afterwards. It may also be called a failed adoption. After legal finalization, the disruption process is usually initiated by adoptive parents via a court petition and is analogous to divorce proceedings. It is a legal avenue unique to adoptive parents as disruption/dissolution does not apply to biological kin, although biological family members are sometimes disowned or abandoned.[91]

Ad hoc studies performed in the U.S., however, suggest that between 10 and 25 percent of adoptions through the child welfare system (e.g., excluding babies adopted from other countries or step-parents adopting their stepchildren) disrupt before they are legally finalized and from 1 to 10 percent are dissolved after legal finalization. The wide range of values reflects the paucity of information on the subject and demographic factors such as age; it is known that teenagers are more prone to having their adoptions disrupted than young children.[91]

Adoption by same-sex couples

[edit]

Joint adoption by same-sex couples is legal in 34 countries as of March 2022, and additionally in various sub-national territories. Adoption may also be in the form of stepchild adoption (6 additional countries), wherein one partner in a same-sex couple adopts the child of the other. Most countries that have same-sex marriage allow joint adoption by those couples, the exceptions being Ecuador (no adoption by same-sex couples), Taiwan (stepchild adoption only) and Mexico (in one third of states with same-sex marriage). A few countries with civil unions or lesser marriage rights nonetheless allow step- or joint adoption. In 2019, the American Community Survey (ACS) enhanced its approach to measuring same-sex couple households, explicitly distinguishing between same-sex and opposite-sex spouses or partners.

Same-sex parents, according to the ACS in 2022, were predominantly female. Notably, 26.8% of female same-sex couple households had children under 18, in contrast to 8.2% of male same-sex couple households. In homes with children, female same-sex couples were almost 12% more likely to have biological children compared with male same-sex couples; however, male same-sex couples were 18.5% more likely to adopt and were less likely to have stepchildren.[92]

Parenting of adoptees

[edit]Parenting

[edit]The biological relationship between a parent and child is important, and the separation of the two has led to concerns about adoption. The traditional view of adoptive parenting received empirical support from a Princeton University study of 6,000 adoptive, step, and foster families in the United States and South Africa from 1968 to 1985; the study indicated that food expenditures in households with mothers of non-biological children (when controlled for income, household size, hours worked, age, etc.) were significantly less for adoptees, step-children, and foster children, causing the researchers to speculate that people are less interested in sustaining the genetic lines of others.[93] This theory is supported in another more qualitative study wherein adoptive relationships marked by sameness in likes, personality, and appearance, were associated with both adult adoptees and adoptive parents reporting being happier with the adoption.[94]

Other studies provide evidence that adoptive relationships can form along other lines. A study evaluating the level of parental investment indicates strength in adoptive families, suggesting that parents who adopt invest more time in their children than other parents, and concludes "...adoptive parents enrich their children's lives to compensate for the lack of biological ties and the extra challenges of adoption."[95] Another recent study found that adoptive families invested more heavily in their adopted children, for example, by providing further education and financial support. Noting that adoptees seemed to be more likely to experience problems such as drug addiction, the study speculated that adoptive parents might invest more in adoptees not because they favor them, but because they are more likely than genetic children to need the help.[96]

Psychologists' findings regarding the importance of early mother-infant bonding created some concern about whether parents who adopt older infants or toddlers after birth have missed some crucial period for the child's development. However, research on The Mental and Social Life of Babies suggested that the "parent-infant system", rather than a bond between biologically related individuals, is an evolved fit between innate behavior patterns of all human infants and equally evolved responses of human adults to those infant behaviors. Thus nature "ensures some initial flexibility with respect to the particular adults who take on the parental role."[97]

Beyond the foundational issues, the unique questions posed for adoptive parents are varied. They include how to respond to stereotypes, answering questions about heritage, and how best to maintain connections with biological kin when in an open adoption.[98] One author suggests a common question adoptive parents have is: "Will we love the child even though he/she is not our biological child?"[99] A specific concern for many parents is accommodating an adoptee in the classroom.[100] Familiar lessons like "draw your family tree" or "trace your eye color back through your parents and grandparents to see where your genes come from" could be hurtful to children who were adopted and do not know this biological information. Numerous suggestions have been made to substitute new lessons, e.g., focusing on "family orchards".[101]

Adopting older children presents other parenting issues.[102] Some children from foster care have histories of maltreatment, such as physical and psychological neglect, physical abuse, and sexual abuse, and are at risk of developing psychiatric problems.[103][104] Such children are at risk of developing a disorganized attachment.[105][106][107] Studies by Cicchetti et al. (1990, 1995) found that 80% of abused and maltreated infants in their sample exhibited disorganized attachment styles.[108][109] Disorganized attachment is associated with a number of developmental problems, including dissociative symptoms,[110] as well as depressive, anxious, and acting-out symptoms.[111][112] "Attachment is an active process—it can be secure or insecure, maladaptive or productive."[113] In the U.K., some adoptions fail because the adoptive parents do not get sufficient support to deal with difficult, traumatized children. This is a false economy as local authority care for these children is extremely expensive.[114]

Concerning developmental milestones, studies from the Colorado Adoption Project examined genetic influences on adoptee maturation, concluding that cognitive abilities of adoptees reflect those of their adoptive parents in early childhood but show little similarity by adolescence, resembling instead those of their biological parents and to the same extent as peers in non-adoptive families.[115]

Similar mechanisms appear to be at work in the physical development of adoptees. Danish and American researchers conducting studies on the genetic contribution to body mass index found correlations between an adoptee's weight class and his biological parents' BMI while finding no relationship with the adoptive family environment. Moreover, about one-half of inter-individual differences were due to individual non-shared influences.[116][117]

These differences in development appear to play out in the way young adoptees deal with major life events. In the case of parental divorce, adoptees have been found to respond differently from children who have not been adopted. While the general population experienced more behavioral problems, substance use, lower school achievement, and impaired social competence after parental divorce, the adoptee population appeared to be unaffected in terms of their outside relationships, specifically in their school or social abilities.[118]

Recent research has shown that adoptive parenting may have impacts on adoptive children, it has been shown that warm adoptive parenting reduces internalizing and externalizing problems of the adoptive children over time.[119] Another study shows that warm adoptive parenting at 27 months predicted lower levels of child externalizing problems at ages 6 and 7.[120]

Effects on the original parents

[edit]Several factors affect the decision to release or raise the child. White adolescents tend to give up their babies to non-relatives, whereas black adolescents are more likely to receive support from their own community in raising the child and also in the form of informal adoption by relatives.[121] Studies by Leynes and by Festinger and Young, Berkman, and Rehr found that, for pregnant adolescents, the decision to release the child for adoption depended on the attitude toward adoption held by the adolescent's mother.[122] Another study found that pregnant adolescents whose mothers had a higher level of education were more likely to release their babies for adoption. Research suggests that women who choose to release their babies for adoption are more likely to be younger, enrolled in school, and have lived in a two-parent household at age 10, than those who kept and raised their babies.[123]

There is limited research on the consequences of adoption for the original parents, and the findings have been mixed. One study found that those who released their babies for adoption were less comfortable with their decision than those who kept their babies. However, levels of comfort over both groups were high, and those who released their child were similar to those who kept their child in ratings of life satisfaction, relationship satisfaction, and positive future outlook for schooling, employment, finances, and marriage.[124] Subsequent research found that adolescent mothers who chose to release their babies for adoption were more likely to experience feelings of sorrow and regret over their decision than those who kept their babies. However, these feelings decreased significantly from one year after birth to the end of the second year.[125]

More recent research found that in a sample of mothers who had released their children for adoption four to 12 years prior, every participant had frequent thoughts of their lost child. For most, thoughts were both negative and positive in that they produced both feelings of sadness and joy. Those who experienced the greatest portion of positive thoughts were those who had open, rather than closed or time-limited mediated, adoptions.[126]

In another study that compared mothers who released their children to those who raised them, mothers who released their children were more likely to delay their next pregnancy, to delay marriage, and to complete job training. However, both groups reached lower levels of education than their peers who were never pregnant.[127] Another study found similar consequences for choosing to release a child for adoption. Adolescent mothers who released their children were more likely to reach a higher level of education and to be employed than those who kept their children. They also waited longer before having their next child.[125] Most of the research that exists on adoption effects on the birth parents was conducted with samples of adolescents, or with women who were adolescents when carrying their babies—little data exists for birth parents from other populations. Furthermore, there is a lack of longitudinal data that may elucidate long-term social and psychological consequences for birth parents who choose to place their children for adoption.

Development of adoptees

[edit]Previous research on adoption has led to assumptions that indicate that there is a heightened risk in terms of psychological development and social relationships for adoptees. Yet, such assumptions have been clarified as flawed due to methodological failures. But more recent studies have been supportive in indicating more accurate information and results about the similarities, differences and overall lifestyles of adoptees.[128] Adoptees are four times more likely to attempt suicide than other people.[129]

Evidence about the development of adoptees can be supported in newer studies. It can be said that adoptees, in some respect, tend to develop differently from the general population. This can be seen in many aspects of life, but usually can be found as a greater risk around the time of adolescence. For example, it has been found that many adoptees experience difficulty in establishing a sense of identity.[130]

Identity

[edit]There are many ways in which the concept of identity can be defined. It is true in all cases that identity construction is an ongoing process of development, change and maintenance of identifying with the self. Research has shown that adolescence is a time of identity progression rather than regression.[131] One's identity tends to lack stability in the beginning years of life but gains a more stable sense in later periods of childhood and adolescence. Typically associated with a time of experimentation, there are endless factors that go into the construction of one's identity. As well as being many factors, there are many types of identities one can associate with. Some categories of identity include gender, sexuality, class, racial and religious, etc. For transracial and international adoptees, tension is generally found in the categories of racial, ethnic and national identification. Because of this, the strength and functionality of family relationships play a huge role in its development and outcome of identity construction. Transracial and transnational adoptees tend to develop feelings of a lack of acceptance because of such racial, ethnic, and cultural differences. Therefore, exposing transracial and transnational adoptees to their "cultures of origin" is important in order to better develop a sense of identity and appreciation for cultural diversity.[132] Identity construction and reconstruction for transnational adoptees the instant they are adopted. For example, based upon specific laws and regulations of the United States, the Child Citizen Act of 2000 makes sure to grant immediate U.S. citizenship to adoptees.[132]

Identity is defined both by what one is and what one is not. Adoptees born into one family lose an identity and then borrow one from the adopting family. The formation of identity is a complicated process and there are many factors that affect its outcome. From a perspective of looking at issues in adoption circumstances, the people involved and affected by adoption (the biological parent, the adoptive parent and the adoptee) can be known as the "triad members and state". Adoption may threaten triad members' sense of identity. Triad members often express feelings related to confused identity and identity crises because of differences between the triad relationships. Adoption, for some, precludes a complete or integrated sense of self. Triad members may experience themselves as incomplete, deficient, or unfinished. They state that they lack feelings of well-being, integration, or solidity associated with a fully developed identity.[133]

Influences

[edit]Family plays a vital role in identity formation. This is not only true in childhood but also in adolescence. Identity (gender/sexual/ethnic/religious/family) is still forming during adolescence and family holds a vital key to this. The research seems to be unanimous; a stable, secure, loving, honest and supportive family in which all members feel safe to explore their identity is necessary for the formation of a sound identity. Transracial and International adoptions are some factors that play a significant role in the identity construction of adoptees. Many tensions arise from relationships built between the adoptee(s) and their family. These include being "different" from the parent(s), developing a positive racial identity, and dealing with racial/ethnic discrimination.[134] It has been found that multicultural and transnational youth tend to identify with their biological parents' culture of origin and ethnicity rather than their residing location, yet it is sometimes hard to balance an identity between the two because school environments tend to lack diversity and acknowledgment regarding such topics.[135] These tensions also tend to create questions for the adoptee, as well as the family, to contemplate. Some common questions include what will happen if the family is more naïve to the ways of socially constructed life? Will tensions arise if this is the case? What if the very people that are supposed to be modeling a sound identity are in fact riddled with insecurities? Ginni Snodgrass answers these questions in the following way. The secrecy in an adoptive family and the denial that the adoptive family is different builds dysfunction into it. "... social workers and insecure adoptive parents have structured a family relationship that is based on dishonesty, evasions and exploitation. To believe that good relationships will develop on such a foundation is psychologically unsound" (Lawrence). Secrecy erects barriers to forming a healthy identity.[136]

The research says that the dysfunction, untruths and evasiveness that can be present in adoptive families not only makes identity formation impossible, but also directly works against it. What effect on identity formation is present if the adoptee knows they are adopted but has no information about their biological parents? Silverstein and Kaplan's research states that adoptees lacking medical, genetic, religious, and historical information are plagued by questions such as "Who am I?" "Why was I born?" "What is my purpose?" This lack of identity may lead adoptees, particularly in adolescent years, to seek out ways to belong in a more extreme fashion than many of their non-adopted peers. Adolescent adoptees are overrepresented among those who join sub-cultures, run away, become pregnant, or totally reject their families.[137][138]

Concerning developmental milestones, studies from the Colorado Adoption Project examined genetic influences on adoptee maturation, concluding that cognitive abilities of adoptees reflect those of their adoptive parents in early childhood but show little similarity by adolescence, resembling instead those of their biological parents and to the same extent as peers in non-adoptive families.[115]

Similar mechanisms appear to be at work in the physical development of adoptees. Danish and American researchers conducting studies on the genetic contribution to body mass index found correlations between an adoptee's weight class and his biological parents' BMI while finding no relationship with the adoptive family environment. Moreover, about one-half of inter-individual differences were due to individual non-shared influences.[116][117]

These differences in development appear to play out in the way young adoptees deal with major life events. In the case of parental divorce, adoptees have been found to respond differently from children who have not been adopted. While the general population experienced more behavioral problems, substance use, lower school achievement, and impaired social competence after parental divorce, the adoptee population appeared to be unaffected in terms of their outside relationships, specifically in their school or social abilities.[118]

The adoptee population does, however, seem to be more at risk for certain behavioral issues. Researchers from the University of Minnesota studied adolescents who had been adopted and found that adoptees were twice as likely as non-adopted people to develop oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), with an 8% rate in the general population.[139][non-primary source needed] Suicide risks were also significantly greater than the general population. Swedish researchers found both international and domestic adoptees undertook suicide at much higher rates than non-adopted peers; with international adoptees and female international adoptees, in particular, at highest risk.[140]

Nevertheless, work on adult adoptees has found that the additional risks faced by adoptees are largely confined to adolescence. Young adult adoptees were shown to be alike with adults from biological families and scored better than adults raised in alternative family types including single parent and step-families.[141] Moreover, while adult adoptees showed more variability than their non-adopted peers on a range of psychosocial measures, adult adoptees exhibited more similarities than differences with adults who had not been adopted.[142] There have been many cases of remediation or the reversibility of early trauma. For example, in one of the earliest studies conducted, Professor Goldfarb in England concluded that some children adjust well socially and emotionally despite their negative experiences of institutional deprivation in early childhood.[143] Other researchers also found that prolonged institutionalization does not necessarily lead to emotional problems or character defects in all children. This suggests that there will always be some children who fare well, who are resilient, regardless of their experiences in early childhood.[144] Furthermore, much of the research on psychological outcomes for adoptees draws from clinical populations. This suggests that conclusions such that adoptees are more likely to have behavioral problems such as ODD and ADHD may be biased. Since the proportion of adoptees that seek mental health treatment is small, psychological outcomes for adoptees compared to those for the general population are more similar than some researchers propose.[145]

While adoption studies have shown that by adulthood the personalities of adopted siblings are little or no more similar than random pairs of strangers, the parenting style of adoptive parents may still play a role in the outcome of their adoptive children. Research has suggested that adoptive parents can have impacts on adoptees as well, several recent studies have shown that warm adoptive parenting can reduce behavioral problems of adopted children over time.[119][120]

Mental health

[edit]Adopted children are more likely to experience psychological and behavioral problems than non-adopted peers.[146] Children who were older than four at the time of their adoption experience more psychological problems than those who were younger.[147][148]

According to study in the UK, adopted children can have mental health problems that do not improve even four years after their adoption. Children with multiple adverse childhood experiences are more likely to have mental health problems. The study suggests that to identify and treat mental health problems early, care professionals and the adopting parents need detailed biographical information about the child's life.[147][149] Another study in the UK suggests that adopted children are more likely to suffer from post-traumatic stress (PTS) than the general population. Their PTS symptoms depend on the type of adverse experiences they went through and knowledge of their history offers an option for tailored support.[150][151]

Adoptees of LGBT parents

[edit]There is evidence that shows the adoptees of LGBT families and those in heterosexual families have no significant differences in development. One of the main arguments used against same-sex adoption is that a child needs a mother and a father in the home to develop properly. However, a 2013 study of predictors for psychological outcomes of adoptees showed that family type (hetero, gay, lesbian) does not affect the child's adjustment; rather the preparedness of the adoptive parent(s), and health of relationship to partner, and other contextual factors predicted later adjustment in early placed adoptees.[152][153] Along with this, a 2009 study showed again that sexual orientation of parents does not affect externalizing and internalized problems, but family functioning and income can affect adjustment, especially for older adoptees.[154]

Late-Discovery Adoptees

[edit]"Late-discovery adoption" is a term used to describe the situation where an adopted individual first discovers that they are adopted at a later age than is universally considered to be appropriate, often well into adulthood. Adopted individuals who discover their adoption status at a later age are referred to as late-discovery adoptees (LDAs). Failure of the adoptive parent(s) to disclose adoption status to a child is an outdated adoption practice that was once fairly common for adoptees born in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s. Since the 1970s, it has been socially unacceptable to keep the truth from adopted individuals regarding their genetic origins. The discovery of the deception regarding true parentage and that one is, in fact, a late-discovery adoptee can add "layers of trauma, loss, betrayal, identity confusion, and disorganization upon learning the truth."[155][156]

Public perception of adoption

[edit]

In Western culture, many see the common image of a family as being that of a heterosexual couple with biological children. This idea places alternative family forms outside the norm. As a consequence – research indicates – disparaging views of adoptive families exist, along with doubts concerning the strength of their family bonds.[157][158]

The most recent adoption attitudes survey completed by the Evan Donaldson Institute provides further evidence of this stigma. Nearly one-third of the surveyed population believed adoptees are less-well adjusted, more prone to medical issues, and predisposed to drug and alcohol problems. Additionally, 40–45% thought adoptees were more likely to have behavior problems and trouble at school. In contrast, the same study indicated adoptive parents were viewed favorably, with nearly 90% describing them as "lucky, advantaged, and unselfish".[159]

The majority of people state that their primary source of information about adoption comes from friends and family and the news media. Nevertheless, most people report the media provides them a favorable view of adoption; 72% indicated receiving positive impressions.[160] There is, however, still substantial criticism of the media's adoption coverage. Some adoption blogs, for example, criticized Meet the Robinsons for using outdated orphanage imagery[161][162] as did advocacy non-profit The Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute.[163]

The stigmas associated with adoption are amplified for children in foster care.[164] Negative perceptions result in the belief that such children are so troubled it would be impossible to adopt them and create "normal" families.[165] A 2004 report from the Pew Commission on Children in Foster Care has shown that the number of children waiting in foster care doubled since the 1980s and now remains steady at about a half-million a year."[166]

Attitude toward Adoption Questionnaire (ATAQ):[167] this questionnaire was first developed by Abdollahzadeh, Chaloyi and Mahmoudi(2019).[168] Preliminary Edition: This questionnaire has 23 items based on the Likert scale of 1 (totally Disagree), up to 5 (Totally Agree) being obtained after refining the items designed to construct the present tool and per-study study. The analysis of item and initial psychometric analyses indicate that there are two factors in it. Items 3-10-11-12-14-15-16-17-19-20-21 are reversed and the rest are graded positively. The results of exploratory factor analysis by main components with varimax rotation indicated two components of attitude toward adoption being named respectively cognitive as the aspects of attitude toward adoption and behavioral-emotional aspects of attitude toward adoption. These two components explained 43.25% of the variance of the total sample. Cronbach's alpha coefficient was used to measure the reliability of the questionnaire. Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.709 for the whole questionnaire, 0.71 for the first component, and 0.713 for the second one. In addition, there was a significant positive relationship between desired social tendencies and the cognitive aspect of attitude toward adoption as well as the behavioral -emotional aspects of attitude toward adoption (P ≤ 0.01).

Forced adoption

[edit]Family preservation is the emphasis that, if possible, mothers and children should be kept together.[169] In the U.S., this was clearly illustrated by the shift in policy of the New York Foundling Home, an adoption-institution that is among the country's oldest and one that had pioneered sealed records. It established three new principles including "to prevent placements of children...", reflecting the belief that children would be better served by staying with their biological families, a striking shift in policy that remains in force today.[170] In addition, groups such as Origins USA (founded in 1997) started to actively speak about family preservation and the rights of mothers.[171] The intellectual tone of these reform movements was influenced by the publishing of The Primal Wound by Nancy Verrier. "Primal wound" is described as the "devastation which the infant feels because of separation from its birth mother. It is the deep and consequential feeling of abandonment which the baby adoptee feels after the adoption and which may continue for the rest of his life."[172]

Forced adoption has also been enforced with the rationale of child welfare. The children of unwed or single mothers are commonly the target of such forced adoption. This was prominent during baby scoop era in the 1950s through the 1970s in the anglosphere. The children of parents in poverty have also been targeted for forced adoption under the rationale of child welfare. This was often the case for Verdingkinder or "contract children" in Switzerland between the 1850s through the middle of the twentieth century.

Forced assimilation

[edit]Removing children of ethnic minorities from their families to be adopted by those of the dominant ethnic group has been used as a method of forced assimilation. Forced adoption based on ethnicity occurred during World War II. In German-occupied Poland, it is estimated that 200,000 Polish children with purportedly Aryan traits were removed from their families and given to German or Austrian couples,[173] and only 25,000 returned to their families after the war.[174] The Stolen Generation of Aboriginal people in Australia were affected by similar policies,[175] as were Native Americans in the United States[176] and First Nations of Canada.[177] These practices have become significant social and political issues in recent years, and in many cases the policies have changed.[178][179] The United States, for example, now has the 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act, which allows the tribe and family of a Native American child to be involved in adoption decisions, with preference being given to adoption within the child's tribe.[180] While forced assimilation usually revolves around ethnicity, assimilating children of political minorities has also occurred. In Spain under Francisco Franco's 1939–1975 dictatorship the newborns of some left-wing opponents of the regime, or unmarried or poor couples, were removed from their mothers and adopted. New mothers were frequently told their babies had died suddenly after birth and the hospital had taken care of their burials, when in fact they were given or sold to another family. It is believed that up to 300,000 babies were involved. These practices—which allegedly involved doctors, nurses, nuns and priests—outlived Franco's death in 1975 and carried on as an illegal baby trafficking network until 1987 when a new law regulating adoption was introduced.[181][182]

Commercialized adoption

[edit]Adoption is usually managed by judges, bureaucrats and social workers. Profiting from giving or receiving orphans has incentivized abusive practices.[183]

Baby farming

[edit]Baby farming is the practice of accepting custody of a child in return for payment. This was most common in Victorian Britain. Illegitimacy and its attendant social stigma were usually the impetus for a mother's decision to give her child to a baby farmer. Baby 'farmers' would sometimes neglect or murder the babies to keep costs down.[citation needed]

Child harvesting

[edit]Child harvesting is the practice of rearing human children to be sold, typically for adoption. Poor mothers have used street clinics, known as "baby factories", to deliver babies to be adopted by richer women for payment.[184] While this can be voluntary, baby factories have also coerced or abducted women into such facilities to be raped in order to sell their babies for adoption.[185][186] Organized rings in Nairobi are known to abduct the children of homeless mothers sleeping on the street.[184] During the One Child Policy in China, when women were only allowed to have one child, local governments would often allow the woman to give birth and then they would take the baby away. Child traffickers, often paid by the government, would sell the children to orphanages that would arrange international adoptions worth tens of thousands of dollars, turning a profit for the government.[187]

Birth and adoption records

[edit]Adoption practices have changed significantly over the course of the 20th century, with each new movement labeled, in some way, as reform.[188] Beginning in the 1970s, efforts to improve adoption became associated with opening records and encouraging family preservation. These ideas arose from suggestions that the secrecy inherent in modern adoption may influence the process of forming an identity,[172][189] create confusion regarding genealogy,[190] and provide little in the way of medical history.

Birth records: After a legal adoption in the United States, an adopted person's original birth certificate is usually amended and replaced with a new post-adoption birth certificate. The names of any birth parents listed on the original birth certificate are replaced on an amended certificate with the names of the adoptive parents, making it appear that the child was born to the adoptive parents.[191] Beginning in the late 1930s and continuing through the 1970s, state laws allowed for the sealing of original birth certificates after an adoption and, except in Alaska and Kansas, made the original birth certificate unavailable to the adopted person even at the age of majority.[192]

Adopted people have long sought to undo these laws so that they can obtain their own original birth certificates. Movements to unseal original birth certificates and other adoption records for adopted people proliferated in the 1970s along with increased acceptance of illegitimacy. In the United States, Jean Paton founded Orphan Voyage in 1954, and Florence Fisher founded the Adoptees' Liberty Movement Association (ALMA) in 1971, calling sealed records "an affront to human dignity".[193] While in 1975, Emma May Vilardi created the first mutual-consent registry, the International Soundex Reunion Registry (ISRR), allowing those separated by adoption to locate one another.[194] and Lee Campbell and other birthmothers established CUB (Concerned United Birthparents). Similar ideas were taking hold globally with grass-roots organizations like Parent Finders in Canada and Jigsaw in Australia. In 1975, England and Wales opened records on moral grounds.[195]

By 1979, representatives of 32 organizations from 33 states, Canada and Mexico gathered in Washington, DC, to establish the American Adoption Congress (AAC) passing a unanimous resolution: "Open Records complete with all identifying information for all members of the adoption triad, birthparents, adoptive parents and adoptee at the adoptee's age of majority (18 or 19, depending on state) or earlier if all members of the triad agree."[196] Later years saw the evolution of more militant organizations such as Bastard Nation (founded in 1996), groups that helped overturn sealed records in Alabama, Delaware, New Hampshire, Oregon, Tennessee, Maine, and Vermont.[197][198] A coalition of New York and national adoptee rights activists successfully worked to overturn a restrictive 83-year-old law in 2019, and adult adopted people born in New York, as well as their descendants, today have the right to request and obtain their own original birth certificates.[199][200] As of 2025, sixteen states in the United States recognize the right of adult adopted people to obtain their own original birth certificates, including Alabama, Alaska, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Kansas, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Dakota, and Vermont.[201][202] In 2024, Minnesota became the fifteenth state to ensure adopted people have the legal right to obtain their original birth certificate.[203][192] In 2025, Georgia enacted a law that restored the right to adult adopted people to request their own original birth records, becoming the sixteenth state in the United States to do so.

Language of adoption

[edit]Since the 1970s, changes in social attitudes have resulted in examination of the language used in adoption and shifts in language use. Controversies in adoption reform efforts have been reflected in the varying terminology recommended by adoptive parents, birth parents, adoptees, and professionals involved in the adoption process such as social workers. Two of the contrasting sets of terms are commonly referred to as "positive adoption language" (PAL, sometimes called "respectful adoption language" or RAL), and "honest adoption language".

As adoption search and support organizations developed, there were challenges to the language in common use at the time. Books such as Adoption Triangle by Sorosky, Pannor and Baran (1978) and newly formed support groups such as CUB (Concerned United Birthparents) argued for a shift in language from "natural parent" to "birthparent."[204][205] In 1979, social worker Marietta Spencer wrote "The Terminology of Adoption," introducing the idea of "positive adoption language" and arguing that "[s]ocial service professionals and adoptive parents should take responsibility for providing informed and sensitive leadership in the use of words."[206] Terms used in "positive adoption language" and the related "respectful adoption language" include the terms "birth mother" (to replace the terms "natural mother" and "real mother"), and "placing" (to replace the term "surrender").

In contrast, proponents of "honest adoption language" (HAL) emphasize the value of the family relationships that existed prior to legal adoption and note that mothers who have "voluntarily surrendered" children seldom view it as a choice that was freely made.[207][208] Proponents of "honest language adoption" argue that the use of the term "birth mother" dehumanizes women who have given birth, likening them to an incubator, and does not reflect that mother-child relationships continue after the physical act of giving birth.[209] Terms included in HAL include terms that were used before PAL, including "natural mother" and "surrendered for adoption," as well as the use of language emphasizing the lifelong status of adoptees, such as "is adopted" instead of "was adopted."[209]

Reunion

[edit]Estimates for the extent of search behavior by adoptees have proven elusive; studies show significant variation.[210] In part, the problem stems from the small adoptee population which makes random surveying difficult, if not impossible.

Nevertheless, some indication of the level of search interest by adoptees can be gleaned from the case of England and Wales which opened adoptees' birth records in 1975. The U.K. Office for National Statistics has projected that 33% of all adoptees would eventually request a copy of their original birth records, exceeding original forecasts made in 1975 when it was believed that only a small fraction of the adoptee population would request their records. The projection is known to underestimate the true search rate, however, since many adoptees of the era get their birth records by other means.[211]

The research literature states adoptees give four reasons for desiring reunion: 1) they wish for a more complete genealogy, 2) they are curious about events leading to their conception, birth, and relinquishment, 3) they hope to pass on information to their children, and 4) they have a need for a detailed biological background, including medical information. It is speculated by adoption researchers, however, that the reasons given are incomplete: although such information could be communicated by a third-party, interviews with adoptees, who sought reunion, found they expressed a need to actually meet biological relations.[212]

It appears the desire for reunion is linked to the adoptee's interaction with and acceptance within the community. Internally focused theories suggest some adoptees possess ambiguities in their sense of self, impairing their ability to present a consistent identity. Reunion helps resolve the lack of self-knowledge.[213]

Externally focused theories, in contrast, suggest that reunion is a way for adoptees to overcome social stigma. First proposed by Goffman, the theory has four parts: 1) adoptees perceive the absence of biological ties as distinguishing their adoptive family from others, 2) this understanding is strengthened by experiences where non-adoptees suggest adoptive ties are weaker than blood ties, 3) together, these factors engender, in some adoptees, a sense of social exclusion, and 4) these adoptees react by searching for a blood tie that reinforces their membership in the community. The externally focused rationale for reunion suggests adoptees may be well adjusted and happy within their adoptive families, but will search as an attempt to resolve experiences of social stigma.[212]

Some adoptees reject the idea of reunion. It is unclear, though, what differentiates adoptees who search from those who do not. One paper summarizes the research, stating, "...attempts to draw distinctions between the searcher and non-searcher are no more conclusive or generalizable than attempts to substantiate ... differences between adoptees and nonadoptees."[214]

In sum, reunions can bring a variety of issues for adoptees and parents. Nevertheless, most reunion results appear to be positive. In the largest study to date (based on the responses of 1,007 adoptees and relinquishing parents), 90% responded that reunion was a beneficial experience. This does not, however, imply ongoing relationships were formed between adoptee and parent nor that this was the goal.[215]

Cultural variations

[edit]Attitudes and laws regarding adoption vary greatly. Whereas all cultures make arrangements whereby children whose birth parents are unavailable to rear them can be brought up by others, not all cultures have the concept of adoption, that is treating unrelated children as equivalent to biological children of the adoptive parents. Under Islamic Law, for example, adopted children must keep their original surname to be identified with blood relations,[216] and, traditionally, women wear a hijab in the presence of males in their adoptive households. In Egypt, these cultural distinctions have led to making adoption illegal opting instead for a system of foster care.[217][218]

Homecoming Day

[edit]In some countries, such as the United States, "Homecoming Day" is the day when an adoptee is officially united with their new adoptive family.[219]

See also

[edit]- Adoption by celebrities

- Adoption by country

- Adoption fraud

- Adoptee rights

- Adult adoption

- Affiliation

- Attachment disorder

- Attachment theory

- Attachment-based therapy

- Child welfare

- Child-selling

- Effects of adoption on the birth mother

- Genetic sexual attraction

- National Adoption Day

- Notable orphans and foundlings

- Putative father registry

- Reactive attachment disorder

- Social work

References

[edit]- ^ Code of Hammurabi

- ^ Codex Justinianus Archived 14 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Brodzinsky and Schecter (editors), The Psychology of Adoption, 1990, page 274

- ^ H. David Kirk, Adoptive Kinship: A Modern Institution in Need of Reform, 1985, page xiv.

- ^ a b Benet, Mary Kathleen (1976). The Politics of Adoption. Free Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-02-902500-0.

- ^ John Boswell, The Kindness of Strangers, 1998, page 74, 115

- ^ John Boswell, The Kindness of Strangers, 1998, page 62-63

- ^ Scheidel, W. (28 September 2011). "The Roman Slave Supply". In Bradley, Keith; Cartledge, Paul (eds.). The Cambridge World History of Slavery. Cambridge University Press. pp. 287–310. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521840668.016. ISBN 978-0-511-78034-9.

- ^ John Boswell, The Kindness of Strangers, 1998, page 3

- ^ John Boswell, The Kindness of Strangers, 1998, page 53-95

- ^ Vinita Bhargava, Adoption in India: Policies and Experiences, 2005, page 45

- ^ W. Menski, Comparative Law in a Global Context: The Legal Systems of Asia and Africa, 2000

- ^ S. Finley-Croswhite, Review of Blood Ties and Fictive Ties, Canadian Journal of History[permanent dead link], August 1997

- ^ a b Brodzinsky and Schecter (editors), The Psychology of Adoption, 1990, page 274

- ^ John Boswell, The Kindness of Strangers, 1998, page 224

- ^ a b John Boswell, The Kindness of Strangers, 1998, page 184

- ^ John Boswell, The Kindness of Strangers, 1998, page 420

- ^ John Boswell, The Kindness of Strangers, 1998, page 421.

- ^ Wayne Carp, Editor, Adoption in America, article by: Susan Porter, A Good Home, A Good Home, page 29.

- ^ Wayne Carp, Editor, Adoption in America, article by: Susan Porter, A Good Home, A Good Home, page 37.

- ^ a b Ellen Herman, Adoption History Project, University of Oregon, Topic: Timeline Archived 15 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wayne Carp, Editor, Adoption in America, article by: Susan Porter, A Good Home, A Good Home, page 44.

- ^ Wayne Carp, Editor, Adoption in America, article by: Susan Porter, A Good Home, A Good Home, page 45.

- ^ Ellen Herman, Adoption History Project, University of Oregon, Topic: Charles Loring Brace, The Dangerous Classes of New York and Twenty Years' Work Among Them, 1872

- ^ Charles Loring Brace, The Dangerous Classes of New York and Twenty Years' Work Among Them, 1872

- ^ Ellen Herman, Adoption History Project, University of Oregon, Topic: Charles Loring Brace Archived 19 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Stephen O'Connor, Orphan Trains, Page 95

- ^ Wayne Carp (Editor), E. Adoption in America: Historical Perspectives, page 160

- ^ Ellen Herman, Adoption History Project, University of Oregon, Topic: Home Studies Archived 19 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ M. Gottlieb, The Foundling, 2001, page 76

- ^ E. Wayne Carp (Editor), Adoption in America: Historical Perspectives, page 108

- ^ Ellen Herman, Adoption History Project, University of Oregon, Topic: Placing Out Archived 19 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bernadine Barr, "Spare Children, 1900–1945: Inmates of Orphanages as Subjects of Research in Medicine and in the Social Sciences in America" (PhD diss., Stanford University, 1992), p. 32, figure 2.2.

- ^ Ellen Herman, Adoption History Project, University of Oregon, Topic: Eugenics Archived 27 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lawrence and Pat Starkey, Child Welfare and Social Action in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, 2001 page 223

- ^ H.H. Goddard, Excerpt from Wanted: A Child to Adopt Archived 28 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ E. Wayne Carp (Editor), Adoption in America: Historical Perspectives, page 181

- ^ Mosher, William D.; Bachrach, Christine A. (January–February 1996). "Understanding U.S. Fertility: Continuity and Change in the National Survey of Family Growth, 1988–1995". Family Planning Perspectives. 28 (1). Guttmacher Institute: 5. doi:10.2307/2135956. JSTOR 2135956. Archived from the original on 24 October 2008.

- ^ Barbara Melosh, Strangers and Kin: the American Way of Adoption, page 106

- ^ Barbara Melosh, Strangers and Kin: the American Way of Adoption, page 105-107

- ^ E. Wayne Carp, Family Matters: Secrecy and Disclosure in the History of Adoption, Harvard University Press, 2000, pages 103–104.

- ^ National Council for Adoption, Adoption Fact Book, 2000, page 42, Table 11

- ^ "US Supreme Court Cases from Justia & Oyez". Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- ^ M. Gottlieb, The Foundling, 2001, page 106

- ^ "Adoption History: Adoption Statistics". darkwing.uoregon.edu. Retrieved 23 July 2025.

- ^ Christine Adamec and William Pierce, The Encyclopedia of Adoption, 2nd Edition, 2000

- ^ Ellen Herman, Adoption History Project, University of Oregon, Topic: International Adoption

- ^ Bruno Perreau, The Politics of Adoption: Gender and the Making of French Citizenship, MIT Press, 2014.

- ^ U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Trends in Foster Care and Adoption

- ^ Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Adoptions Australia 2003–04 Archived 10 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Child Welfare Series Number 35.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics, Population and Household Characteristics

- ^ UK Office for National Statistics, Adoption Data Archived 11 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ UK Office for National Statistics, Live Birth Data

- ^ "Adoptionen, Zeitreihe". Statistisches Bundesamt (in German). Retrieved 14 July 2025.

- ^ "Geburten". Statistisches Bundesamt (in German). Retrieved 14 July 2025.

- ^ Íslensk Ættleiðing, Adoption Numbers Archived 23 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Statistics Iceland, Births and Deaths

- ^ Adoption Authority of Ireland, Report of The Adoption Board 2003 Archived 11 March 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Central Statistics Office Ireland, Births, Deaths, Marriages Archived 10 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tom Kington, Families in Rush to Adopt a Foreign Child, Guardian, 28 January 2007

- ^ Demo Istat, Demographic Balance Archived 16 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine, 2006

- ^ "Adoptions Data". Department of Child, Youth and Family. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ "Live births (by sex), stillbirths (Maori and total population) (Annual-Jun) – Infoshare". Statistics New Zealand. Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ Statistics Norway, Adoptions,

- ^ Statistics Norway, Births

- ^ "Number of adoptions of children and young persons aged 0-17, number by sex, type of adoption and year". Statistikmyndigheten. 27 June 2025. Retrieved 14 July 2025.

- ^ "Births by sex, month and year". Statistikmyndigheten. 21 February 2025.

- ^ a b The National Adoption Information Clearinghouse of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, How Many Children Were Adopted in 2007 and 2008? Archived 12 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine, September 2011

- ^ "National Vital Statistics System – Birth Data". Centers for Disease Control. 9 January 2019. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ Openness in Adoption: Building Relationships Between Adoptive and Birth Families Archived 27 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Child Welfare Information Gateway, January 2013, Retrieved 1 January 2019

- ^ "Postadoption Contact Agreements Between Birth and Adoptive Families". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children's Bureau. 2005. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 10 May 2008.

- ^ "Postadoption Contact Agreements Between Birth and Adoptive Families: Summary of State Laws" (PDF). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children's Bureau. 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ See, e.g., Seymore, Malinda L. (March 2015). "Openness in International Adoption". Texas A&M Law Scholarship.

- ^ Ellen Herman, Adoption History Project, University of Oregon, Topic: Confidentiality Archived 3 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Confidential Adoption Information: Domestic Infant Adoptions". www.bethany.org. Archived from the original on 7 April 2007.

- ^ SECA Organization Archived 10 February 2009 at archive.today

- ^ National Council For Adoption, Adoption Factbook, 2000, Table 11

- ^ Berry, Marianne; Barth, Richard P.; Needell, Barbara (1996). "Preparation, support, and satisfaction of adoptive families in agency and independent adoptions". Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal. 13 (2): 157–183. doi:10.1007/BF01876644. S2CID 144559063.

- ^ Mosher, William D.; Bachrach, Christine A. (January–February 1996). "Understanding U.S. Fertility: Continuity and Change in the National Survey of Family Growth, 1988–1995". Family Planning Perspectives. 28 (1). Guttmacher Institute: 4–12. doi:10.2307/2135956. JSTOR 2135956. PMID 8822409. Archived from the original on 24 October 2008.

- ^ "Adoption Experiences of Women and Men and Demand for Children to Adopt by Women 18–44 Years of Age in the United States, 2002" (PDF). Vital Health Stat. 23 (27). U.S. Center for Disease Control: 19. August 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 December 2023.

- ^ "Adoption Experiences of Women and Men and Demand for Children to Adopt by Women 18–44 Years of Age in the United States, 2002" (PDF). Vital Health Stat. 23 (27). U.S. Center for Disease Control: 8. August 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 December 2023.

- ^ a b c "US Child Welfare Information Gateway: "How Many Children Were Adopted in 2000 and 2001?"" (PDF).

- ^ "AFCARS Report #1 – Current Estimates as of January 1999". Children's Bureau. Administration for Children and Families. Archived from the original on 26 September 2006. Retrieved 18 July 2006.

- ^ Lindgren, Cecilia (18 January 2022). "Changing notions of "good parents" and "the child's best interest": Adoption in Sweden 1918-2018". Annales de démographie historique. 142 (2): 8. doi:10.3917/adh.142.0051. ISSN 0066-2062.

- ^ Nemtsova, Anna. "Who Will Adopt the Orphans?". Russia Now. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023.

- ^ Crary, David (3 April 2010). "Adopted Chinese orphans often have special needs". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- ^ "33: Convention of 29 May 1993 on Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption". HCCH. Archived from the original on 29 August 2023. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ The International Law on the Rights of the Child (book), Geraldine Van Bueren, 1998, p.95, ISBN 90-411-1091-7, web: Books-Google-81MC.

- ^ The best interests of the child: the least detrimental alternative (book), Joseph Goldstein, 1996, p.16, web: Books-Google-HkC.

- ^ "What is private fostering? | CoramBAAF". corambaaf.org.uk.

- ^ a b U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Child Welfare Information Gateway, Adoption Disruption and Dissolution Archived 3 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine, December 2004

- ^ Hemez, Paul. "Spouses in Opposite-Sex and Same-Sex Married Couples and Their Households: 2022" (PDF). data.census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 4 March 2025.

- ^ Case, A.; Lin, I. F.; McLanahan, S. (2000). "How Hungry is the Selfish Gene?" (PDF). The Economic Journal. 110 (466): 781–804. doi:10.1111/1468-0297.00565. S2CID 11707574.

- ^ L. Raynor, The Adopted Child Comes of Age, 1980