Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

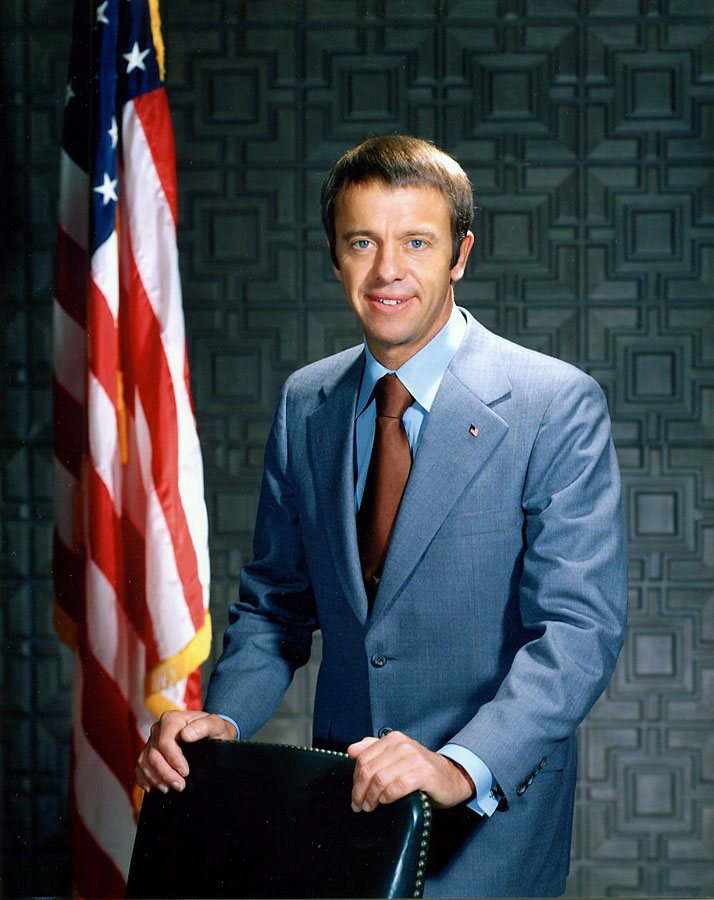

Alan Shepard

View on Wikipedia

Alan Bartlett Shepard Jr. (November 18, 1923 – July 21, 1998) was an American astronaut. In 1961, he became the second person and the first American to travel into space and, in 1971, he became the fifth and oldest person to walk on the Moon, at age 47.

Key Information

A graduate of the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis, Shepard saw action with the surface navy during World War II. He became a naval aviator in 1947, and a test pilot in 1950. He was selected as one of the original NASA Mercury Seven astronauts in 1959, and in May 1961 he made the first crewed Project Mercury flight, Mercury-Redstone 3, in a spacecraft he named Freedom 7. His craft entered space, but was not capable of achieving orbit. He became the second person, and the first American, to travel into space. In the final stages of Project Mercury, Shepard was scheduled to pilot the Mercury-Atlas 10 (MA-10), which was planned as a three-day mission. He named Mercury Spacecraft 15B Freedom 7 II in honor of his first spacecraft, but the mission was canceled.

Shepard was designated as the commander of the first crewed Project Gemini mission, but was grounded in October 1963 due to Ménière's disease, an inner-ear ailment that caused episodes of extreme dizziness and nausea. This was surgically corrected in 1968, and in 1971, Shepard commanded the Apollo 14 mission, piloting the Apollo Lunar Module Antares. He was the only one of the Mercury Seven astronauts to walk on the Moon. During the mission, he hit two golf balls on the lunar surface.

Shepard was Chief of the Astronaut Office from November 1963 to August 1969 (the approximate period of his grounding), and from June 1971 until April 30, 1974. On August 25, 1971, he was promoted to rear admiral, the first astronaut to reach that rank. He retired from the United States Navy and NASA on July 31, 1974.

Early life

[edit]Alan Bartlett Shepard Jr. was born on November 18, 1923, at 64 East Derry Road in Derry, New Hampshire,[1] to Alan Bartlett Shepard Sr. (1891–1973) and Pauline Renza Shepard (née Emerson; 1900–1993).[2] He had a younger sister, Pauline, who was known as Polly.[3] The two were descendants of Mayflower passenger Richard Warren,[2] and were related to Scottish emigrants from Berneray in the Outer Hebrides, through the Shepard line.[4] Their grandmother, Annie Bartlett Shepard, served as the State Regent of the New Hampshire Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution.[5] Alan Bartlett Shepard Sr., known as Bart, worked in the Derry National Bank, owned by Shepard's grandfather. Bart joined the National Guard in 1915 and served in France with the American Expeditionary Force during World War I.[6] He remained in the National Guard between the wars, and was recalled to active duty during World War II, rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel.[7]

Shepard attended Adams School in Derry, where his academic performance impressed his teachers. He skipped the sixth grade[8] and proceeded to middle school at Oak Street School in Derry,[7] where he also skipped the eighth grade.[8] He achieved the Boy Scouts of America rank of First Class Scout.[9] In 1936, he went to the Pinkerton Academy, a private school in Derry that his father had attended and where his grandfather had been a trustee.[10] He completed grades 9 to 12 there.[8] Fascinated by flight, he created a model airplane club at the academy and his Christmas present in 1938 was a flight in a Douglas DC-3.[11] The following year he began cycling to Manchester Airfield, where he would do odd jobs in exchange for the occasional ride in an airplane or informal flying lesson.[12][13]

Shepard graduated from Pinkerton Academy in 1940. Because World War II was already raging in Europe, his father wanted him to join the Army. Shepard chose the Navy instead. He easily passed the entrance exam to the United States Naval Academy at Annapolis in 1940 but at sixteen was too young to enter that year. The Navy sent him to the Admiral Farragut Academy, a prep school for the Naval Academy from which he graduated with the Class of 1941.[14] Tests administered at Farragut indicated an IQ of 145 but his grades were mediocre.[15]

At the Naval Academy, Shepard enjoyed aquatic sports. He was a keen and competitive sailor, winning several races, including a regatta held by the Annapolis Yacht Club. He learned to sail all the types of boats the academy owned, up to and including USS Freedom, a 90-foot (27 m) schooner. He also participated in swimming and rowed with the eight.[15] During his Christmas break in 1942, he went to Principia College to be with his sister, who was unable to go home owing to wartime travel restrictions. There he met Louise Brewer, whose parents were pensioners on the du Pont family estate and like Renza Shepard, were devout Christian Scientists.[16][17] Owing to the war, the usual four-year course at Annapolis was cut short by a year. He graduated with the Class of 1945 on June 6, 1944, ranked 463rd out of 915, and was commissioned as an ensign and awarded a Bachelor of Science degree. The following month he became secretly engaged to Louise.[18][19]

Naval service

[edit]"You know, being a test pilot isn't always the healthiest business in the world."

After a month of classroom instruction in aviation, Shepard was posted to a destroyer, USS Cogswell, in August 1944;[21] it was US Navy policy that aviation candidates should first have some service at sea.[12] At the time the destroyer was deployed on active service in the Pacific Ocean. Shepard joined it when it returned to the naval base at Ulithi on October 30.[22] After just two days at sea Cogswell helped rescue 172 sailors from the cruiser USS Reno, which had been torpedoed by a Japanese submarine, then escorted the crippled ship back to Ulithi. The ship was buffeted by Typhoon Cobra in December 1944, a storm in which three other destroyers went down, and battled kamikazes in the invasion of Lingayen Gulf in January 1945.[23]

Cogswell returned to the United States for an overhaul in February 1945. Shepard was given three weeks' leave, in which time he and Louise decided to marry. The ceremony took place on March 3, 1945, in St. Stephen's Lutheran Church in Wilmington, Delaware. His father, Bart, served as his best man. The newlyweds had only a brief time together before Shepard rejoined Cogswell at the Long Beach Navy Yard on April 5, 1945.[24] After the war, they had two children, both daughters: Laura, born in 1947,[25] and Julie, born in 1951.[26] Following the death of Louise's sister in 1956, they raised her five-year-old niece, Judith Williams—whom they renamed Alice to avoid confusion with Julie—as their own, although they never adopted her.[27][28] They eventually had six grandchildren.[29]

On Shepard's second cruise with Cogswell, he was appointed a gunnery officer, responsible for the 20 mm and 40 mm antiaircraft guns on the ship's bow. They engaged kamikazes in the Battle of Okinawa, where the ship served in the dangerous role of a radar picket. The job of the radar pickets was to warn the fleet of incoming kamikazes, but because they were often the first ships sighted by incoming Japanese aircraft, they were also the most likely ships to be attacked. Cogswell performed this duty from May 27 until June 26, 1945, when it rejoined Task Force 38. The ship also participated in the Allied naval bombardments of Japan, and was present in Tokyo Bay for the Surrender of Japan in September 1945. Shepard returned to the United States later that month.[22][30]

In November 1945, Shepard arrived at Naval Air Station Corpus Christi in Texas, where he commenced basic flight training on January 7, 1946.[31] He was an average student, and for a time faced being "bilged" (dropped) from flight training and reassigned to the surface navy. To make up for this, he took private lessons at a local civilian flying school—something the Navy frowned on—earning a civil pilot's license.[32] His flying skills gradually improved, and by early 1947 his instructors rated him above average. He was sent to Naval Air Station Pensacola in Florida for advanced training. His final test was six perfect landings on the carrier USS Saipan. The following day, he received his naval aviator wings, which his father pinned on his chest.[33]

Shepard was assigned to Fighter Squadron 42 (VF-42), flying the Vought F4U Corsair. The squadron was nominally based on the aircraft carrier USS Franklin D. Roosevelt, but the ship was being overhauled at the time Shepard arrived, and in the meantime the squadron was based at Naval Air Station Norfolk in Virginia. He departed on his first cruise, of the Caribbean, on Franklin D. Roosevelt with VF-42 in 1948. Most of the aviators were, like Shepard, on their first assignment. Those who were not were given the opportunity to qualify for night landings on a carrier, a dangerous maneuver, especially in a Corsair, which had to bank sharply on approach. Shepard managed to persuade his squadron commander to allow him to qualify as well. After briefly returning to Norfolk, the carrier set out on a nine-month tour of the Mediterranean Sea. He earned a reputation for carousing and chasing women. He also instituted a ritual of, whenever he could, calling Louise at 17:00 (her time) each day.[34]

Normally sea duty alternated with periods of duty ashore. In 1950, Shepard was selected to attend the United States Naval Test Pilot School at Naval Air Station Patuxent River in Maryland with class five, graduating in January 1951.[35][36] As a test pilot he conducted high-altitude tests to obtain information about the light and air masses at different altitudes over North America; carrier suitability certification of the McDonnell F2H Banshee; experiments with the Navy's new in-flight refueling system; and tests of the angled flight deck.[19] He narrowly avoided being court-martialed by the station commander, Rear Admiral Alfred M. Pride, after looping the Chesapeake Bay Bridge and making low passes over the beach at Ocean City, Maryland, and the base; but Shepard's superiors, John Hyland and Robert M. Elder, interceded on his behalf.[37]

Shepard's next assignment was to VF-193, a night fighter squadron flying the Banshee, that was based at Naval Air Station Moffett Field, California. The squadron was part of Commander James D. "Jig Dog" Ramage's Air Group 19. Naval aviators with experience in jet aircraft were still relatively rare, and Ramage specifically requested Shepard's assignment on the advice of Elder, who commanded VF-193's sister squadron, VF-191. Ramage made Shepard his own wingman,[38] a decision that would save Ramage's life in 1954, when his oxygen system failed and Shepard talked him through a landing.[39] As squadron operations officer, Shepard's most important task was imparting his knowledge of flying jets to his fellow aviators to keep them alive. He served two tours on the aircraft carrier USS Oriskany in the western Pacific. It set out on a combat tour off Korea in 1953, during the Korean War, but the Korean Armistice Agreement ended the fighting in July 1953, and Shepard did not see combat.[40]

Rear Admiral John P. Whitney requested Shepard's services as an aide de camp, but Shepard wanted to fly. Therefore, at Shepard's request, Ramage spoke to the admiral on his behalf, and Shepard was instead sent back to Patuxent.[41] He flight tested the McDonnell F3H Demon, Vought F-8 Crusader, Douglas F4D Skyray and Grumman F-11 Tiger.[42] The Vought F7U Cutlass tended to go into an inverted spin during a snap roll. This was not unusual; many aircraft did this, but normally if the pilot let go of the stick the aircraft would correct itself. When he attempted this in the F7U, Shepard found this was not the case. He was unable to break out of the spin and was forced to eject. In 1957, he was project test pilot on the Douglas F5D Skylancer. Shepard did not like the plane, and gave it an unfavorable report. The Navy canceled orders for it, buying the F8U instead. He also filed an unfavorable report on the F11F after a harrowing incident in which the engine failed on him during a high-speed dive. He managed to restart the engine and avoid a fatal crash.[43]

Shepard was an instructor at the Test Pilot School, and then entered the Naval War College at Newport, Rhode Island.[44] He graduated in 1957, and became an Aircraft Readiness Officer on the staff of the Commander-in-Chief, Atlantic Fleet.[45] By this time he had logged more than 3,600 hours of flying time, including 1,700 hours in jets.[46]

NASA career

[edit]Mercury Seven

[edit]On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite. This shattered American confidence in its technological superiority, creating a wave of anxiety known as the Sputnik crisis. Among his responses, President Dwight D. Eisenhower launched the Space Race. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was established on October 1, 1958, as a civilian agency to develop space technology. One of its first initiatives was publicly announced on December 17, 1958. This was Project Mercury,[47] which aimed to launch a man into Earth orbit, return him safely to the Earth, and evaluate his capabilities in space.[48]

NASA received permission from Eisenhower to recruit its first astronauts from the ranks of military test pilots. The service records of 508 graduates of test pilot schools were obtained from the United States Department of Defense. From these, 110 were found that matched the minimum standards:[49] the candidates had to be younger than 40, possess a bachelor's degree or equivalent and to be 5 feet 11 inches (1.80 m) or less. While these were not all strictly enforced, the height requirement was firm, owing to the size of the Project Mercury spacecraft.[50] The 110 were then split into three groups, with the most promising in the first group.[51]

The first group of 35, which included Shepard, assembled at the Pentagon on February 2, 1959. The Navy and Marine Corps officers were welcomed by the Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Arleigh Burke, while the United States Air Force officers were addressed by the Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force, General Thomas D. White. Both pledged their support to the Space Program, and promised that the careers of volunteers would not be adversely affected. NASA officials then briefed them on Project Mercury. They conceded that it would be a hazardous undertaking, but emphasized that it was of great national importance. That evening, Shepard discussed the day's events with fellow naval aviators Jim Lovell, Pete Conrad and Wally Schirra, all of whom would eventually become astronauts. They were concerned about their careers, but decided to volunteer.[52][53]

The briefing process was repeated with a second group of 34 candidates a week later. Of the 69, six were found to be over the height limit, 15 were eliminated for other reasons, and 16 declined. This left NASA with 32 candidates. Since this was more than expected, NASA decided not to bother with the remaining 41 candidates, as 32 candidates seemed a more than adequate number from which to select 12 astronauts as planned. The degree of interest also indicated that far fewer would drop out during training than anticipated, which would result in training astronauts who would not be required to fly Project Mercury missions. It was therefore decided to cut the number of astronauts selected to just six.[54] Then came a grueling series of physical and psychological tests at the Lovelace Clinic and the Wright Aerospace Medical Laboratory.[55] Only one candidate, Lovell, was eliminated on medical grounds at this stage, and the diagnosis was later found to be in error;[56] thirteen others were recommended with reservations. The director of the NASA Space Task Group, Robert R. Gilruth, found himself unable to select only six from the remaining eighteen, and ultimately seven were chosen.[56]

Shepard was informed of his selection on April 1, 1959. Two days later he traveled to Boston with Louise for the wedding of his cousin Anne, and was able to break the news to his parents and sister.[57][58] The identities of the seven were announced at a press conference at Dolley Madison House in Washington, D.C., on April 9, 1959:[59] Scott Carpenter, Gordon Cooper, John Glenn, Gus Grissom, Wally Schirra, Alan Shepard, and Deke Slayton.[60] The magnitude of the challenge ahead of them was made clear a few weeks later, on the night of May 18, 1959, when the seven astronauts gathered at Cape Canaveral to watch their first rocket launch, of an SM-65D Atlas, which was similar to the one that was to carry them into orbit. A few minutes after liftoff, it spectacularly exploded, lighting up the night sky. The astronauts were stunned. Shepard turned to Glenn and said: "Well, I'm glad they got that out of the way."[61]

Freedom 7

[edit]

Faced with intense competition from the other astronauts, particularly John Glenn, Shepard quit smoking and adopted Glenn's habit of taking a morning jog.[62] On January 19, 1961, Gilruth informed the seven astronauts that Shepard had been chosen for the first American crewed mission into space.[63] Shepard later recalled Louise's response when he told her that she had her arms around the man who would be the first man in space: "Who let a Russian in here?"[64] During training he flew 120 simulated flights.[65] Although this flight was originally scheduled for April 26, 1960,[66] it was postponed several times by unplanned preparatory work, initially to December 5, 1960, then mid-January 1961,[67] March 6, 1961,[68] April 25, 1961,[69] May 2, 1961, and finally to May 5, 1961.[70] On April 12, 1961, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first person in space, and the first to orbit the Earth.[71] It was another body blow to American pride.[68] When Shepard heard the news he slammed his fist down on a table so hard a NASA public relations officer feared he might have broken his hand.[72]

On May 5, 1961, Shepard piloted the Mercury-Redstone 3 mission and became the second person, and the first American, to travel into space.[73] He named his spacecraft, Mercury Spacecraft 7, Freedom 7.[68] He awoke at 01:10, and had breakfast consisting of orange juice, a filet mignon wrapped in bacon, and scrambled eggs with his backup, John Glenn, and flight surgeon William K. Douglas. He was helped into his space suit by suit technician Joseph W. Schmitt, and boarded the transfer van at 03:55. He ascended the gantry at 05:15, and entered the spacecraft five minutes later. It was expected that liftoff would occur in another two hours and five minutes,[74] so Shepard's suit did not have any provision for elimination of bodily wastes, but after being strapped into the capsule's seat, launch delays kept him in that suit for over four hours.[75] Shepard's endurance gave out before launch, and he was forced to empty his bladder into the suit. Medical sensors attached to it to track the astronaut's condition in flight were turned off to avoid shorting them out. The urine pooled in the small of his back, where it was absorbed by his undergarment.[76][77] After Shepard's flight, the space suit was modified, and by the time of Gus Grissom's Mercury-Redstone 4 suborbital flight in July, a liquid waste collection feature had been built into the suit.[78]

Unlike Gagarin's 108-minute orbital flight in a Vostok spacecraft three times the size of Freedom 7,[71] Shepard stayed on a suborbital trajectory for the 15-minute flight, which reached an altitude of 101.2 nautical miles (116.5 statute miles; 187.4 kilometers), and then fell to a splashdown 263.1 nautical miles (302.8 statute miles; 487.3 kilometers) down the Atlantic Missile Range.[79] Unlike Gagarin, whose flight was strictly automatic, Shepard had some control of Freedom 7, spacecraft attitude in particular.[80] Shepard's launch was seen live on television by millions.[81] It was launched atop a Redstone rocket. According to Gene Kranz in his 2000 book Failure Is Not an Option, "When reporters asked Shepard what he thought about as he sat atop the Redstone rocket, waiting for liftoff, he had replied, 'The fact that every part of this ship was built by the lowest bidder.'"[82]

After a dramatic Atlantic Ocean recovery, Shepard observed that he "didn't really feel the flight was a success until the recovery had been successfully completed. It's not the fall that hurts; it's the sudden stop."[83] Splashdown occurred with an impact comparable to landing a jet aircraft on an aircraft carrier. A recovery helicopter arrived after a few minutes, and the capsule was lifted partly out of the water to allow Shepard to leave by the main hatch. He squeezed out of the door and into a sling hoist, and was pulled into the helicopter, which flew both the astronaut and spacecraft to the aircraft carrier USS Lake Champlain. The whole recovery process took just eleven minutes.[84] Shepard was celebrated as a national hero, honored with ticker-tape parades in Washington, New York and Los Angeles, and received the NASA Distinguished Service Medal from President John F. Kennedy.[85] He was also awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.[86]

Shepard served as capsule communicator (CAPCOM) for Glenn's Mercury-Atlas 6 orbital flight, which he had also been considered for,[87] and Carpenter's Mercury-Atlas 7.[88] He was the backup pilot for Cooper for the Mercury-Atlas 9 mission,[89] nearly replacing Cooper after Cooper flew low over the NASA administration building at Cape Canaveral in an F-102.[90] In the final stages of Project Mercury, Shepard was scheduled to pilot the Mercury-Atlas 10 (MA-10), which was planned as a three-day mission.[91] He named Mercury Spacecraft 15B Freedom 7 II in honor of his first spacecraft, and had the name painted on it,[92] but on June 12, 1963, NASA Administrator James E. Webb announced that Mercury had accomplished all its goals and no more missions would be flown.[91] Shepard went as far as making a personal appeal to President Kennedy, but to no avail.[93]

Project Gemini; chief astronaut

[edit]

Project Gemini, with a crew of two, followed on from Project Mercury.[94] After the Mercury-Atlas 10 mission was canceled, Shepard was designated as the commander of the first crewed Gemini mission, with Thomas P. Stafford chosen as his pilot.[95] In late 1963, Shepard began to experience episodes of extreme dizziness and nausea, accompanied by a loud, clanging noise in the left ear. He tried to keep it secret, fearing that he would lose his flight status, but was aware that if an episode occurred in the air or in space it could be fatal. Following an episode during a lecture in Houston, where he had recently moved from Virginia Beach, Virginia, Shepard was forced to confess his ailment to Slayton, who was now Director of Flight Operations, and seek help from NASA's doctors.[96]

The doctors diagnosed Ménière's disease, a condition in which fluid pressure builds up in the inner ear. This syndrome causes the semicircular canals and motion detectors to become extremely sensitive, resulting in disorientation, dizziness, and nausea. There was no known cure, but in about 20 percent of cases the condition goes away by itself. They prescribed diuretics in an attempt to drain the fluid from the ear. They also diagnosed glaucoma. An X-ray found a lump on his thyroid, and on January 17, 1964, surgeons at Hermann Hospital made an incision on his throat and removed 20 percent of his thyroid.[97][98] The condition caused Shepard to be removed from flight status. Grissom and John Young flew Gemini 3 instead.[99]

Shepard was designated Chief of the Astronaut Office in November 1963, receiving the title of Chief Astronaut.[100] He thereby became responsible for NASA astronaut training. This involved the development of appropriate training programs for all astronauts and the scheduling of training of individual astronauts for specific missions and roles. He provided and coordinated astronaut input into mission planning and the design of spacecraft and other equipment to be used by astronauts on space missions.[92] He also was on the selection panel for the NASA Astronaut Group 5 in 1966.[101] He spent much of his time investing in banks, wildcatting, and real estate. He became part owner and vice president of Baytown National Bank and would spend hours on the phone in his NASA office overseeing it. He also bought a partnership in a ranch in Weatherford, Texas, that raised horses and cattle.[102] During this period, his secretary Gaye Alford had two "mood-of-the-day" photographs taken of Shepard, one of a smiling Al Shepard, and the other of a grim-looking Commander Shepard. To warn visitors of Shepard's mood, she would hang the appropriate photograph on the door of her boss's private office.[103] Tom Wolfe characterized Shepard's dual personalities as "Smilin' Al" and the "Icy Commander".[104]

Apollo program

[edit]

In 1968, Stafford went to Shepard's office and told him that an otologist in Los Angeles had developed a cure for Ménière's disease. Shepard flew to Los Angeles, where he met with William F. House. House proposed to open Shepard's mastoid bone and make a tiny hole in the endolymphatic sac. A small tube (endolymphatic-subarachnoid shunt) was inserted to drain excess fluid. The surgery was conducted on May 14, 1968, at St. Vincent's Hospital in Los Angeles, where Shepard checked in under the pseudonym of Victor Poulos.[92][105] The surgery was successful, and he was restored to full flight status on May 7, 1969.[92]

Slayton put Shepard down to command the next available Moon mission, which was Apollo 13 in 1970. Under normal circumstances, this assignment would have gone to Cooper, as the backup commander of Apollo 10, but Cooper was not given it. A rookie, Stuart Roosa, was designated the Command Module Pilot. Shepard asked for Jim McDivitt as his Lunar Module Pilot, but McDivitt, who had already commanded the Apollo 9 mission, balked at the prospect, arguing that Shepard did not have sufficient Apollo training to command a Moon mission. A rookie, Edgar Mitchell, was designated the Lunar Module Pilot instead.[106][107]

When Slayton submitted the proposed crew assignments to NASA headquarters, George Mueller turned them down on the grounds that the crew was too inexperienced. So Slayton asked Jim Lovell, who had been the backup commander for Apollo 11, and was slated to command Apollo 14, if his crew would be willing to fly Apollo 13 instead. He agreed to do so, and Shepard's crew was assigned to Apollo 14.[106][107]

Neither Shepard nor Lovell expected there would be much difference between Apollo 13 and Apollo 14,[106] but Apollo 13 went disastrously wrong. An oxygen tank explosion caused the Moon landing to be aborted and nearly resulted in the loss of the crew. It became a joke between Shepard and Lovell, who would offer to give Shepard back the mission each time they bumped into each other. The failure of Apollo 13 delayed Apollo 14 until 1971 so that modifications could be made to the spacecraft. The target of the Apollo 14 mission was switched to the Fra Mauro formation, the intended destination of Apollo 13.[108]

Shepard made his second space flight as commander of Apollo 14 from January 31 to February 9, 1971. It was America's third successful lunar landing mission. Shepard piloted the Lunar Module Antares.[109] He became the fifth and, at the age of 47, the oldest man to walk on the Moon, and the only one of the Mercury Seven astronauts to do so.[110][111]

This was the first mission to broadcast extensive color television coverage from the lunar surface, using the Westinghouse Lunar Color Camera. (The same color camera model was used on Apollo 12 and provided about 30 minutes of color telecasting before it was inadvertently pointed at the Sun, ending its usefulness.) While on the Moon, Shepard used a Wilson six-iron head attached to a lunar sample scoop handle to drive golf balls.[109] Despite thick gloves and a stiff space suit, which forced him to swing the club with one hand, Shepard struck two golf balls, driving the second, as he jokingly put it, "miles and miles and miles".[112] Analysis of high-resolution film scans of the event determined the distance to be about 24 yards (22 m) for the first shot and 40 yards (37 m) for the second.[113][114]

For this mission Shepard was awarded the NASA Distinguished Service Medal[115] and the Navy Distinguished Service Medal. His citation read:

The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Distinguished Service Medal to Captain Alan Bartlett Shepard, Jr. (NSN: 0-389998), United States Navy, for exceptionally meritorious and distinguished service in a position of great responsibility to the Government of the United States, as Spacecraft Commander for the Apollo 14 flight to the Fra-Mauro area of the Moon during the period 31 January 1971 to 9 February 1971. Responsible for the on-board control of the spacecraft command module Kittyhawk and the lunar module Antares in the gathering of scientific data involving complex and difficult instrumentation positing and sample gathering, including a hazardous two-mile traverse of the lunar surface, Captain Shepard, by his brilliant performance, contributed essentially to the success of this vital scientific Moon mission. As a result of his skillful leadership, professional competence and dedication, the Apollo 14 mission, with its numerous tasks and vital scientific experiments, was accomplished in an outstanding manner, enabling scientists to determine more precisely the Moon's original formation and further forecast man's proper role in the exploration of his Universe. By his courageous and determined devotion to duty, Captain Shepard rendered valuable and distinguished service and contributed greatly to the success of the United States Space Program, thereby upholding the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.[86]

Following Apollo 14, Shepard returned to his position as Chief of the Astronaut Office in June 1971. In July 1971 President Richard Nixon appointed him as a delegate to the 26th United Nations General Assembly, a position in which he served from September to December 1971.[92] He was promoted to rear admiral by Nixon on August 26, 1971, the first astronaut to reach this rank.[116][117] He was succeeded as Chief of the Astronaut Office by John Young on April 30, 1974.[118] Shepard retired from both NASA and the Navy on July 31, 1974.[92]

Later years

[edit]

Shepard was devoted to his children. Frequently, Julie, Laura and Alice were the only astronauts' children at NASA events. He taught them to ski and took them skiing in Colorado. He once rented a small plane to fly them and their friends from Texas to a summer camp in Maine. He doted on his six grandchildren as well. After Apollo 14, he began to spend more time with Louise and started taking her with him on trips to the Paris Air Show every other year and to Asia.[119] Louise heard rumors of his affairs.[120] The publication of Tom Wolfe's 1979 book The Right Stuff made them public knowledge but she never confronted him about it[121] nor did she ever contemplate leaving him.[119]

After Shepard left NASA, he served on the boards of many corporations. He also served as president of his umbrella company for several business enterprises, Seven Fourteen Enterprises, Inc. (named for his two flights, Freedom 7 and Apollo 14).[122] He made a fortune in banking and real estate.[123] He was a fellow of the American Astronautical Society and the Society of Experimental Test Pilots, a member of Rotary, Kiwanis, the Mayflower Society, the Order of the Cincinnati and the American Fighter Aces, an honorary member of the board of directors for the Houston School for Deaf Children, and a director of the National Space Institute and the Los Angeles Ear Research Institute.[92] In 1984, together with the other surviving Mercury astronauts and Betty Grissom, Gus Grissom's widow, Shepard founded the Mercury Seven Foundation, which raises money to provide college scholarships to science and engineering students. It was renamed the Astronaut Scholarship Foundation in 1995. Shepard was elected its first president and chairman, positions he held until October 1997, when he was succeeded by former astronaut Jim Lovell.[92]

In 1994, he published a book with two journalists, Jay Barbree and Howard Benedict, called Moon Shot: The Inside Story of America's Race to the Moon. Fellow Mercury astronaut Deke Slayton is also named as an author. The book included a composite photograph showing Shepard hitting a golf ball on the Moon. There are no still images of this event, the only record is TV footage.[112] The book was turned into a TV miniseries in 1994.[124]

Shepard was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia in 1996 and died from complications of the disease in Pebble Beach, California, on July 21, 1998.[125][126][110] Following his death, President Bill Clinton issued a statement of condolences stating "he [Shepard] led our country and all humanity beyond the bounds of our planet, across a truly new frontier, into the new era of space exploration" and "his service will always loom large in America's history".[127] Shepard's widow Louise had planned to cremate his remains and scatter the ashes, but before she was able to do that, she died from a heart attack—on August 25, 1998, at 17:00, which, coincidentally, was the same time of day at which he had always phoned her when they were apart. They had been married for 53 years. Their family decided to cremate them both so their ashes were scattered, together, from a Navy helicopter over Stillwater Cove in front of their Pebble Beach home.[128][129]

On December 11, 2021, twenty-three years after his death, Shepard's daughter, Laura Shepard Churchley, also flew in space (suborbitally, above the Karman line) aboard the non-NASA Blue Origin's New Shepard spacecraft on the NS-19 mission.[130][131]

Awards and honors

[edit]Shepard was awarded the Congressional Space Medal of Honor by President Jimmy Carter on October 1, 1978.[132] He also received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement in 1981;[133] the Langley Gold Medal on May 5, 1964; the John J. Montgomery Award in 1963; the Lambert trophy; the SETP Iven C. Kincheloe Award;[134] the Cabot Award; the Collier Trophy;[135] and the City of New York City Gold Medal for 1971.[92] He was awarded honorary degrees of Master of Arts from Dartmouth College in 1962, D.Sc. from Miami University in 1971, and Doctorate of Humanities from Franklin Pierce College in 1972.[92] He was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1977,[136] the International Space Hall of Fame in 1981,[20][137] and the U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame on May 11, 1990.[122][138]

The Navy named a supply ship, USNS Alan Shepard (T-AKE-3), for him in 2006.[139] The McAuliffe-Shepard Discovery Center in Concord, New Hampshire, is named after Shepard and Christa McAuliffe.[140] In 1996, the entirety of I-565 (which passes in front of the U.S. Space & Rocket Center, home to both the Saturn V Dynamic Test Vehicle and a full-scale vertical Saturn V replica) was designated the "Admiral Alan B. Shepard Highway" in his honor.[141] Interstate 93 in New Hampshire, from the Massachusetts border to Hooksett, is designated the Alan B. Shepard Highway,[142] and in Hampton, Virginia, a road is named Commander Shepard Boulevard in his honor.[143] His hometown of Derry has the nickname Space Town in honor of his career as an astronaut.[144] Following an act of Congress, the post office in Derry was designated the Alan B. Shepard Jr. Post Office Building.[145] Alan Shepard Park in Cocoa Beach, Florida, a beach-side park south of Cape Canaveral, is named in his honor.[146] The City of Virginia Beach renamed its convention center, with its integral geodesic dome, the Alan B. Shepard Convention Center. The building was later renamed the Alan B. Shepard Civic Center, and was razed in 1994.[147] At the time of the Freedom 7 launch, Shepard lived in Virginia Beach.[148]

Shepard's high school alma mater in Derry, Pinkerton Academy, has a building named after him, and the school team is called the Astros after his career as an astronaut.[149] Alan B. Shepard High School, in Palos Heights, Illinois, which opened in 1976, was named in his honor. Framed newspapers throughout the school depict various accomplishments and milestones in Shepard's life. Additionally, an autographed plaque commemorates the dedication of the building. The school newspaper is named Freedom 7 and the yearbook is entitled Odyssey.[150] Blue Origin's suborbital space tourism rocket, the New Shepard, is named after Shepard.[151]

In a 2010 Space Foundation survey, Shepard was ranked as the ninth most popular space hero (tied with astronauts Buzz Aldrin and Gus Grissom).[152] In 2011, NASA honored Shepard with an Ambassador of Exploration Award, consisting of a Moon rock encased in Lucite, for his contributions to the U.S. space program. His family members accepted the award on his behalf during a ceremony on April 28 at the United States Naval Academy Museum in Annapolis, Maryland, where it is on permanent display.[153] On May 4, 2011, the U.S. Postal Service issued a first-class stamp in Shepard's honor, the first U.S. stamp to depict a specific astronaut. The first day of issue ceremony was held at NASA's Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex.[154]

Each year, the Space Foundation, in partnership with the Astronauts Memorial Foundation and NASA, present the Alan Shepard Technology in Education Award for outstanding contributions by K–12 educators or district-level administrators to educational technology. The award recognizes excellence in the development and application of technology in the classroom or to the professional development of teachers. The recipient demonstrates exemplary use of technology either to foster lifelong learners or to make the learning process easier.[155]

In popular culture

[edit]As he was a key figure in the American space program, Shepard's life has been depicted in many biographical and historical works of fiction. In film, Shepard's selection for the Mercury program was covered in 1983's The Right Stuff (where he was played by Scott Glenn),[156] while 2002's Race to Space and 2016's Hidden Figures feature him in a minor role, played by Mark Moses,[157] and Dane Davenport, respectively.[158] The HBO miniseries From the Earth to the Moon starred Ted Levine as Shepard and covered not only his Mercury training but also his involvement in the Apollo missions.[159] Jake McDorman played Shepard in the 2020 TV adaptation of The Right Stuff,[160] while Desmond Harrington played him in the 2015 period drama The Astronaut Wives Club.[161]

Archive footage of Shepard is used in the opening credits montage of Star Trek: Enterprise,as part of a sequence displaying the history of human exploration,[162] while other science fiction works have named characters in a tribute to Shepard – including both the character of Alan Tracy, in the 1960s British series Thunderbirds,[163] and Commander Shepard, the main protagonist of the 2007–2012 BioWare video game series Mass Effect.[164]

British singer-songwriter Darren Hayman's concept album 12 Astronauts includes a song for each man who has walked on the Moon. The lyrics of Don't Clip My Wings (Alan Shepard), sung in the first person, reflect on how Shepard "feared he would never fly again" after his Ménière's diagnosis.[165]

"Shepard's Prayer" is attributed to Shepard, with the phrase supposed to have been uttered by him while he awaited liftoff aboard the Freedom 7. It is usually quoted as "Dear Lord, please don't let me fuck up", although Shepard claimed the words to be "Don't fuck up, Shepard".[166]

Alan Shepard was featured in the 1982 EPCOT Center: The Opening Celebration to celebrate the opening of EPCOT Center in the Walt Disney World Resort. He was a guest alongside Danny Kaye and Drew Barrymore.[167]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Thompson 2004, p. 7.

- ^ a b Burgess 2014, p. 69.

- ^ Thompson 2004, p. 8.

- ^ "Tobar an Dualchais" [The Source of Heritage]. Tobar an Dualchais (in Scottish Gaelic). Archived from the original on October 29, 2023. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

- ^ Claghorn, Charles Eugene (1991). Women Patriots of the American Revolution: A Biographical Dictionary. Scarecrow Press. pp. 161–162. ISBN 978-0-8108-2421-8.

- ^ Thompson 2004, p. 10.

- ^ a b Burgess 2014, p. 70.

- ^ a b c Thompson 2004, pp. 16–18.

- ^ "Astronauts With Scouting Experience". U.S. Scouting Service Project. Archived from the original on May 1, 2019. Retrieved May 1, 2019.

- ^ "History". Pinkerton Academy. Retrieved November 18, 2023.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 20–24.

- ^ a b Shepard et al. 2010, p. 64.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 24–27.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 27–29.

- ^ a b Thompson 2004, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 40–42.

- ^ "Well-wishers besiege Alan Shepard family". Eugene Register-Guard. Eugene, Oregon. Associated Press. October 28, 1961. p. 5. Archived from the original on March 27, 2022. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- ^ Thompson 2004, p. 56.

- ^ a b "Astronaut Bio: Alan B. Shepard, Jr. (REAR ADMIRAL, USN, RET.) NASA ASTRONAUT (DECEASED)" (PDF). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. September 1998. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 20, 2021. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ^ a b "International Space Hall of Fame :: New Mexico Museum of Space History :: Inductee Profile". New Mexico Museum of Space History. Archived from the original on February 27, 2017. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- ^ Thompson 2004, p. 57.

- ^ a b "Cogswell". Naval History and Heritage Command. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved March 2, 2016.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 62–64.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 66–68.

- ^ Thompson 2004, p. 109.

- ^ Thompson 2004, p. 131.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 178–179.

- ^ "Astronaut's Wife Was Confident" (PDF). North Tonawanda NY Evening News. May 5, 1961. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- ^ Thompson 2004, p. 439.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 69–80.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 84–87.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 90–95.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 100–103.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 109–114.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 131–137.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 144–148.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 167–169.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 151–154.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 170–172.

- ^ Shepard et al. 2010, p. 65.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 175–177.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 177–181.

- ^ Thompson 2004, p. 190.

- ^ "Meet the New Men of Space". The Salt Lake Tribune. April 10, 1959. p. 1. Archived from the original on August 13, 2017. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- ^ Burgess 2011, pp. 25–29.

- ^ Swenson, Grimwood & Alexander 1966, p. 134.

- ^ Atkinson & Shafritz 1985, pp. 36–39.

- ^ Burgess 2011, p. 35.

- ^ Burgess 2011, p. 38.

- ^ Burgess 2011, pp. 46–51.

- ^ Atkinson & Shafritz 1985, pp. 40–42.

- ^ Atkinson & Shafritz 1985, p. 42.

- ^ Atkinson & Shafritz 1985, pp. 43–47.

- ^ a b Burgess 2011, pp. 234–237.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Shepard et al. 2010, p. 67.

- ^ Burgess 2011, pp. 274–275.

- ^ Atkinson & Shafritz 1985, pp. 42–47.

- ^ Glenn & Taylor 1985, pp. 274–275.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 262–269.

- ^ Shepard & Slayton 1994, pp. 76–79.

- ^ Shepard, Alan (July–August 1994). "First Step to the Moon". American Heritage. 45 (4). ISSN 0002-8738. Archived from the original on November 7, 2015. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- ^ Swenson, Grimwood & Alexander 1966, p. 343.

- ^ Swenson, Grimwood & Alexander 1966, p. 141.

- ^ Swenson, Grimwood & Alexander 1966, p. 263.

- ^ a b c Swenson, Grimwood & Alexander 1966, p. 342.

- ^ Swenson, Grimwood & Alexander 1966, p. 324.

- ^ Swenson, Grimwood & Alexander 1966, p. 350.

- ^ a b Swenson, Grimwood & Alexander 1966, pp. 332–333.

- ^ Thompson 2004, p. 282.

- ^ Burgess 2014, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Swenson, Grimwood & Alexander 1966, p. 351.

- ^ Swenson, Grimwood & Alexander 1966, p. 341.

- ^ Burgess 2014, pp. 131–134.

- ^ Shepard & Slayton 1994, p. 107.

- ^ Swenson, Grimwood & Alexander 1966, p. 368.

- ^ Swenson, Grimwood & Alexander 1966, pp. 352–357.

- ^ Burgess 2014, p. 147.

- ^ Swenson, Grimwood & Alexander 1966, pp. 360–361.

- ^ Kranz 2000, pp. 200–201.

- ^ "Events of 1961: U.S. in Space". United Press International. 1961. Archived from the original on August 11, 2017. Retrieved April 18, 2011.

- ^ Swenson, Grimwood & Alexander 1966, pp. 356–357.

- ^ As World Watched. Spaceman Hailed After U.S. Triumph, 1961/05/08 (1961) (Motion picture). Universal-International Newsreel. 1961. OCLC 709678549. Retrieved February 20, 2012.

- ^ a b "Valor awards for Alan Bartlett Shepard, Jr". Military Times. Archived from the original on August 11, 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 319–322.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 328–330.

- ^ Burgess 2014, pp. 236–237.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 338–339.

- ^ a b Swenson, Grimwood & Alexander 1966, p. 492.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Alan B. Shepard Jr". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Archived from the original on November 3, 2004. Retrieved November 3, 2009.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 344–345.

- ^ Hacker & Grimwood 1977, pp. 3–5.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 345–346.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 350–351.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 352–354.

- ^ Shepard & Slayton 1994, pp. 168–170.

- ^ Thompson 2004, p. 366.

- ^ Shayler 2001, p. 97.

- ^ Burgess 2013, pp. 50–52.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 362–363.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 359–360.

- ^ Wolfe 1979, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 386–387.

- ^ a b c Thompson 2004, pp. 390–393.

- ^ a b Slayton & Cassutt 1994, pp. 235–238.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 402–406.

- ^ a b "Apollo 14". Apollo to the Moon. Washington, D.C.: National Air and Space Museum. July 1999. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ a b Riley, Christopher (July 10, 2009). "The moon walkers: Twelve men who have visited another world". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 4, 2014. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ Thompson 2004, p. 407.

- ^ a b Jones, Eric M., ed. (1995). "EVA-2 Closeout and the Golf Shots". Apollo 14 Lunar Surface Journal. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Archived from the original on May 24, 2011. Retrieved May 29, 2011.

- ^ Scrivener, Peter (February 4, 2021). "Golf on the moon: Apollo 14 50th anniversary images find Alan Shepard's ball and show how far he hit it". BBC Sport. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Phelps, Jonathan (February 7, 2021). "How far did Alan Shepard golf balls travel on the moon?". UnionLeader.com. Archived from the original on February 8, 2021. Retrieved July 20, 2021.

- ^ "National Aeronautics and Space Administration Honor Awards". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Archived from the original on May 17, 2020. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ "Alan Shepard Becomes Admiral". The Blade. Toledo, Ohio. August 26, 1971. p. 12. Archived from the original on September 14, 2021. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- ^ Burgess 2014, p. 241.

- ^ White, Terry (April 30, 1974). "Young to Head Astronaut Office" (PDF) (Press release). 74-71. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2017.

- ^ a b Thompson 2004, pp. 439–440.

- ^ Thompson 2004, p. 405.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 452–453.

- ^ a b "Alan B. Shepard, Jr". Astronaut Scholarship Foundation. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- ^ Burgess 2014, p. 240.

- ^ Drew, Mike (July 11, 1994). "TBS' 'Moon Shot' Rises Above Other TV Fare". Milwaukee Journal. Archived from the original on June 29, 2017. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- ^ Wilford, John Noble (July 23, 1998). "Alan B. Shepard Jr. Is Dead at 74; First American to Travel in Space". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 14, 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ Thompson 2004, p. 462.

- ^ Clinton, William J. (July 22, 1998). "Remarks on Signing the Internal Revenue Service Restructuring and Reform Act of 1998". The American Presidency Project. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ Thompson 2004, pp. 471–472.

- ^ "Louise Shepard Dies A Month After Her Astronaut Husband". Chicago Tribune. August 27, 2016. Archived from the original on March 20, 2016. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- ^ Skipper, Joe; Gorman, Steve (December 11, 2021). "Daughter of pioneering astronaut Alan Shepard soars to space aboard Blue Origin rocket". Reuters. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- ^ "Watch Live: Michael Strahan and the daughter of astronaut Alan Shepard launch to space with Blue Origin". CBS News. December 11, 2021. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- ^ "Congressional Space Medal of Honor". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Archived from the original on February 20, 2011. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement. Archived from the original on December 12, 2017. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- ^ Wolfe, Tom (October 25, 1979). "Cooper the Cool jockeys Faith 7—between naps". Chicago Tribune. p. 22. Archived from the original on January 7, 2019. Retrieved April 22, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Astronauts Have Their Day at the White House". Chicago Tribune. Chicago, Illinois. October 11, 1963. p. 3. Archived from the original on January 7, 2019. Retrieved April 22, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "National Aviation Hall of fame: Our Enshrinees". National Aviation Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on March 12, 2011. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ^ Harbert, Nancy (September 27, 1981). "Hall to Induct Seven Space Pioneers". Albuquerque Journal. Albuquerque, New Mexico. p. 53. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved April 22, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Mercury Astronauts Dedicate Hall of Fame at Florida Site". Victoria Advocate. Victoria, Texas. Associated Press. May 12, 1990. p. 38. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved April 22, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Navy Christens USNS Alan Shepard". United States Navy. December 7, 2006. Archived from the original on August 13, 2017. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ "McAuliffe-Shepard Discovery Center: About Us". McAuliffe-Shepard Discovery Center. Archived from the original on October 18, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ "City leaders should find a way to honor Huntsville-born civil rights leader Joseph Lowery (editorial)". al.com. January 10, 2012. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- ^ "Alan B Shepard Highway (I-93)". Archived from the original on November 30, 2017. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- ^ Brauchle, Robert (January 16, 2014). "Commander Shepard Boulevard opens to motorists". Daily Press. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017.

- ^ "Derry, NH". Union Leader Corp. Archived from the original on August 30, 2010. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

- ^ "H.R.4517". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on August 18, 2013. Retrieved May 29, 2007.

- ^ "Cocoa Beach Review". Fodor's. Archived from the original on July 29, 2014. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- ^ Quinn, Richard (December 16, 2007). "Sorry, Alan – this golf ball always will be 'The Dome'". The Virginian Pilot. Archived from the original on February 4, 2019.

- ^ "Alan Shepard, 1st American in Space, Honored on 50-Year Anniversary". Fox News Channel. May 5, 2011. Archived from the original on August 13, 2017. Retrieved April 22, 2022.

- ^ Gray, Tara. "Alan B. Shepard, Jr". 40th Anniversary of the Mercury 7. National Aeronautics and Space Administration History Program Office. Archived from the original on December 8, 2006. Retrieved December 29, 2006.

- ^ "About Us". Alan B. Shepard High School. Archived from the original on November 6, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ Gates, Dominic (November 25, 2016). "'Holy Grail of rocketry' achieved, says Amazon and Blue Origin boss Jeff Bezos". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on August 14, 2017. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- ^ "Space Foundation Survey Reveals Broad Range of Space Heroes; Early Astronauts Still the Most Inspirational" (Press release). Colorado Springs, Colorado: Space Foundation. October 27, 2010. Archived from the original on July 23, 2012. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- ^ Mirelson, Doc (April 19, 2011). "NASA Honors Pioneer Astronaut Alan Shepard With Moon Rock" (Press release). Washington, D.C.: National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Media Advisory: M11-077. Archived from the original on April 8, 2013. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- ^ Pearlman, Robert Z. (May 4, 2011). "New U.S. Stamps Honor Astronaut Alan Shepard and Mission to Mercury". Space.com. Ogden, Utah: TechMedia Network. Archived from the original on August 14, 2017. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- ^ "Alan Shepard Technology in Education Award". Space Foundation Discovery Center. Space Foundation. Archived from the original on August 13, 2017. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- ^ Benson, Sheila (December 8, 2016). "From the Archives Our original film review of 'The Right Stuff' holds clues for John Glenn's path to senator". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 13, 2017. Retrieved September 12, 2017.

- ^ "Mark Moses | 1958". Hollywood.com. February 7, 2015. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved September 12, 2017.

- ^ "Dane Davenport | Biography and Filmography". Hollywood.com. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved September 12, 2017.

- ^ Richmond, Ray (March 31, 1998). "Review: 'From the Earth to the Moon'". Variety. Archived from the original on August 25, 2018. Retrieved September 12, 2017.

- ^ Iannucci, Rebecca (June 14, 2019). "The Right Stuff: Jake McDorman, GoT Alum Board Nat Geo's NASA Series". TV Line. Archived from the original on November 15, 2020. Retrieved June 16, 2019.

- ^ Ausiello, Michael (March 19, 2014). "ABC's Astronaut Wives Club Casts Dexter's Desmond Harrington as Alan Shepherd". TV Line. Archived from the original on March 23, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ Geraghty 2007, p. 140.

- ^ Marriott 1992, p. 23.

- ^ Hanson, Ben (April 27, 2011). "Casey Hudson Interview: Mass Effect's Feedback Loop". Game Informer. Archived from the original on July 31, 2012. Retrieved May 1, 2013.

- ^ "Don't Clip My Wings (Alan Sheppard), by Darren Hayman". wiaiwya. Archived from the original on September 5, 2023. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

- ^ Cranford Teague, Jason (May 5, 2011). "50 Years of Americans in Space: Remembering Alan Shepard". WIRED. Archived from the original on May 19, 2023. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- ^ Scrimgeour, Francesca (October 1, 2022). "We've Just Begun to Dream!". Walt Disney Archives. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

References

[edit]- Atkinson, Joseph D.; Shafritz, Jay M. (1985). The Real Stuff: A History of NASA's Astronaut Recruitment Program. Praeger special studies. New York: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-03-005187-6. OCLC 12052375.

- Burgess, Colin (2011). Selecting the Mercury Seven: The Search for America's First Astronauts. Springer-Praxis books in space exploration. New York; London: Springer. ISBN 978-1-4419-8405-0. OCLC 747105631.

- Burgess, Colin (2013). Moon Bound: Choosing and Preparing NASA's Lunar Astronauts. Springer-Praxis books in space exploration. New York; London: Springer. ISBN 978-1-4614-3854-0. OCLC 905162781.

- Burgess, Colin (2014). Freedom 7: The Historic Flight of Alan B. Shepard Jr. Springer-Praxis books in space exploration. New York; London: Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-01155-4. OCLC 902685533.

- Carpenter, M. Scott; Cooper, L. Gordon Jr.; Glenn, John H. Jr.; Grissom, Virgil I.; Schirra, Walter M. Jr.; Shepard, Alan B.; Slayton, Donald K. (2010) [Originally published 1962]. We Seven: By the Astronauts Themselves. New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks. ISBN 978-1-4391-8103-4. LCCN 62019074. OCLC 429024791.

- Geraghty, Lincoln (2007). Living with Star Trek: American culture and the Star Trek universe. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-421-3. OCLC 74525330.

- Glenn, John; Taylor, Nick (1985). John Glenn: A Memoir. New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-11074-6. OCLC 42290245.

- Hacker, Barton C.; Grimwood, James M. (1977). On the Shoulders of Titans: A History of Project Gemini (PDF). Washington, D.C.: National Aeronautics and Space Administration. SP-4203. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 27, 2020. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- Kranz, Gene (2000). Failure Is Not an Option: Mission Control from Mercury to Apollo 13 and Beyond. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0079-9. LCCN 00027720. OCLC 43590801.

- Marriott, John (1992). Thunderbirds Are Go!. London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 1-85283-164-2. OCLC 27642248.

- Naval Test Pilot School (1984). United States Naval Test Pilot School: Historical Narrative and Class Information, 1945 to 1983 (2nd ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Fishergate. OCLC 11680836.

- Shayler, David (2001). Gemini: Steps to the Moon. Springer-Praxis books in astronomy and space sciences. London: Springer. ISBN 978-1-85233-405-5. OCLC 248213555.

- Shepard, Alan B.; Slayton, Donald K.; Barbree, Jay; Benedict, Howard (1994). Moon Shot: The Inside Story of America's Race to the Moon. Atlanta: Turner Publishing Company. ISBN 1-878685-54-6. LCCN 94003027. OCLC 29846731.

- Slayton, Donald K.; Cassutt, Michael (1994). Deke!: U.S. Manned Space: From Mercury to the Shuttle. New York: Forge. ISBN 0-312-85503-6. LCCN 94002463. OCLC 29845663.

- Swenson, Loyd S. Jr.; Grimwood, James M.; Alexander, Charles C. (1966). This New Ocean: A History of Project Mercury. The NASA History Series. Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration. OCLC 569889. NASA SP-4201. Archived from the original on June 17, 2010. Retrieved June 28, 2007.

- Thompson, Neal (2004). Light This Candle: The Life & Times of Alan Shepard, America's First Spaceman (1st ed.). New York: Crown Publishers. ISBN 0-609-61001-5. LCCN 2003015688. OCLC 52631310.

- Wolfe, Tom (1979). The Right Stuff. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-553-27556-8. OCLC 849889526.

External links

[edit]- "Alan Shepard: 1st American in Space". Archived from the original on May 27, 2010. Retrieved May 6, 2010. – slideshow by Life magazine

- Alan Shepard at IMDb

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- "Presentation by Neal Thompson on Light This Candle: The Life and Times of Alan Shepard". C-SPAN. May 26, 2004. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- Oral history interview with Shepard for the Johnson Space Center's History Office, February 20, 1998.

- Remarks by Sen. John Glenn on the death of Alan Shepard, July 22, 1998. C-SPAN.

- Alan Shepard Memorial Service, August 1, 1998. C-SPAN.

- "Admiral Alan B. Shepard, Jr., USN, Biography and Interview". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.