Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Alpha-adrenergic agonist

View on Wikipedia

| Alpha adrenergic agonist | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

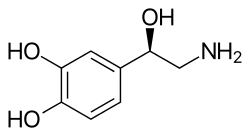

Skeletal structor formula of phenylephrine, a common nasal decongestant | |

| Class identifiers | |

| Use | Decongestant, Hypotension, Bradycardia, Hypothermia etc. |

| ATC code | N07 |

| Biological target | Alpha adrenergic receptors of the α subtype |

| External links | |

| MeSH | D000316 |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

Alpha-adrenergic agonists are a class of sympathomimetic agents that selectively stimulate alpha adrenergic receptors. The alpha-adrenergic receptor has two subclasses, α1 and α2. Alpha 2 receptors are associated with sympatholytic properties. Alpha-adrenergic agonists have the opposite function of alpha blockers. Alpha adrenoreceptor ligands mimic the action of epinephrine and norepinephrine signaling in the heart, smooth muscle and central nervous system, with norepinephrine being the highest affinity. The activation of α1 stimulates the membrane bound enzyme phospholipase C, and activation of α2 inhibits the enzyme adenylate cyclase. Inactivation of adenylate cyclase in turn leads to the inactivation of the secondary messenger cyclic adenosine monophosphate and induces smooth muscle and blood vessel constriction.

Classes

[edit]

Although complete selectivity between receptor agonism is rarely achieved, some agents have partial selectivity. NB: the inclusion of a drug in each category just indicates the activity of the drug at that receptor, not necessarily the selectivity of the drug (unless otherwise noted).

α1 agonist

[edit]α1 agonist: stimulates phospholipase C activity. (vasoconstriction and mydriasis; used as vasopressors, nasal decongestants and during eye exams). Selected examples are:

- Adrenoswitch-1 (photoswitchable partial α1 agonist and light-controlled mydriatic)[1]

- Methoxamine

- Midodrine

- Metaraminol

- Phenylephrine[2]

- Amidephrine[3]

- Sdz-nvi-085 [104195-17-7].

α2 agonist

[edit]α2 agonist: inhibits adenylyl cyclase activity, reduces brainstem vasomotor center-mediated CNS activation; used as antihypertensive, sedative & treatment of opiate dependence and alcohol withdrawal symptoms). Selected examples are:

- Brimonidine

- Clonidine (mixed alpha2-adrenergic and imidazoline-I1 receptor agonist)

- Dexmedetomidine

- Fadolmidine

- Guanfacine,[4] (preference for alpha2A-subtype of adrenoceptor)

- Guanabenz (most selective agonist for alpha2-adrenergic as opposed to imidazoline-I1)

- Guanoxabenz (metabolite of guanabenz)

- Xylazine (not approved for human use)[5]

- Tizanidine

- Methyldopa

- Methylnorepinephrine

- Norepinephrine[6]

- (R)-3-nitrobiphenyline, an α2C selective agonist as well as a weak antagonist at the α2A and α2B subtypes.[7][8]

- Amitraz[9]

- Detomidine[10]

- Lofexidine, an α2A adrenergic receptor agonist.[11]

- Medetomidine, an α2 adrenergic agonist.[12]

- Tasipimidine

Nonspecific agonist

[edit]Nonspecific agonists act as agonists at both alpha-1 and alpha-2 receptors.

- Xylometazoline[13]

- Oxymetazoline[14]

- Apraclonidine[citation needed]

- Cirazoline[15][16]

- Epinephrine[17]

Undetermined/unsorted

[edit]The following agents are also listed as agonists by MeSH.[18]

Clinical significance

[edit]Alpha-adrenergic agonists, more specifically the auto receptors of alpha 2 neurons, are used in the treatment of glaucoma by decreasing the production of aqueous fluid by the ciliary bodies of the eye and also by increasing uveoscleral outflow. Medications such as clonidine and dexmedetomidine target pre-synaptic auto receptors, therefore leading to an overall decrease in norepinephrine which clinically can cause effects such as sedation, analgesia, lowering of blood pressure and bradycardia. There is also low quality evidence that they can reduce shivering post operatively.[19]

The reduction of the stress response caused by alpha 2 agonists were theorised to be beneficial peri operatively by reducing cardiac complications, however this has shown not to be clinically effective as there was no reduction in cardiac events or mortality but there was an increased incidence of hypotension and bradycardia.[20]

Alpha-2 adrenergic agonists are sometimes prescribed alone or in combination with stimulants to treat ADHD.[21]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Prischich D, Gomila AM, Milla-Navarro S, Sangüesa G, Diez-Alarcia R, Preda B, et al. (February 2021). "Adrenergic Modulation With Photochromic Ligands". Angewandte Chemie. 60 (7): 3625–3631. doi:10.1002/anie.202010553. hdl:2434/778579. PMID 33103317.

- ^ Declerck I, Himpens B, Droogmans G, Casteels R (September 1990). "The alpha 1-agonist phenylephrine inhibits voltage-gated Ca2(+)-channels in vascular smooth muscle cells of rabbit ear artery". Pflügers Archiv. 417 (1): 117–119. doi:10.1007/BF00370780. PMID 1963492. S2CID 8074029.

- ^ MacLean MR, Thomson M, Hiley CR (June 1989). "Pressor effects of the alpha 2-adrenoceptor agonist B-HT 933 in anaesthetized and haemorrhagic rats: comparison with the haemodynamic effects of amidephrine". British Journal of Pharmacology. 97 (2): 419–432. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb11969.x. PMC 1854522. PMID 2569342.

- ^ Sagvolden T (December 2006). "The alpha-2A adrenoceptor agonist guanfacine improves sustained attention and reduces overactivity and impulsiveness in an animal model of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)". Behavioral and Brain Functions. 2: 41. doi:10.1186/1744-9081-2-41. PMC 1764416. PMID 17173664.

- ^ Atalik KE, Sahin AS, Doğan N (April 2000). "Interactions between phenylephrine, clonidine and xylazine in rat and rabbit aortas". Methods and Findings in Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology. 22 (3): 145–147. doi:10.1358/mf.2000.22.3.796096. PMID 10893695. S2CID 8218673.

- ^ Lemke KA (June 2004). "Perioperative use of selective alpha-2 agonists and antagonists in small animals". The Canadian Veterinary Journal. 45 (6): 475–480. PMC 548630. PMID 15283516.

- ^ Crassous PA, Cardinaletti C, Carrieri A, Bruni B, Di Vaira M, Gentili F, et al. (August 2007). "Alpha2-adrenoreceptors profile modulation. 3.1 (R)-(+)-m-nitrobiphenyline, a new efficient and alpha2C-subtype selective agonist". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 50 (16): 3964–3968. doi:10.1021/jm061487a. PMID 17630725.

- ^ Del Bello F, Mattioli L, Ghelfi F, Giannella M, Piergentili A, Quaglia W, et al. (November 2010). "Fruitful adrenergic α(2C)-agonism/α(2A)-antagonism combination to prevent and contrast morphine tolerance and dependence". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 53 (21): 7825–7835. doi:10.1021/jm100977d. PMID 20925410.

- ^ Hsu WH, Lu ZX (1984). "Amitraz-induced delay of gastrointestinal transit in mice: Mediated by α2-adrenergic receptors". Drug Development Research. 4 (6): 655–660. doi:10.1002/ddr.430040608.

- ^ "Detomidine | α2-adrenergic Agonist | MedChemExpress". MedchemExpress.com. Retrieved 2024-11-29.

- ^ "Press Announcements - FDA approves the first non-opioid treatment for management of opioid withdrawal symptoms in adults". www.fda.gov. Archived from the original on May 17, 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ Sinclair MD (November 2003). "A review of the physiological effects of alpha2-agonists related to the clinical use of medetomidine in small animal practice". The Canadian Veterinary Journal. 44 (11): 885–897. PMC 385445. PMID 14664351.

- ^ Haenisch B, Walstab J, Herberhold S, Bootz F, Tschaikin M, Ramseger R, et al. (December 2010). "Alpha-adrenoceptor agonistic activity of oxymetazoline and xylometazoline". Fundamental & Clinical Pharmacology. 24 (6): 729–739. doi:10.1111/j.1472-8206.2009.00805.x. PMID 20030735. S2CID 25064699.

- ^ Westfall TC, Westfall DP. "Chapter 6. Neurotransmission: The Autonomic and Somatic Motor Nervous Systems". In Brunton LL, Lazo JS, Parker KL (eds.). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (11th ed.). Archived from the original on 2011-09-30. Retrieved 2015-01-24.

- ^ Horie K, Obika K, Foglar R, Tsujimoto G (September 1995). "Selectivity of the imidazoline alpha-adrenoceptor agonists (oxymetazoline and cirazoline) for human cloned alpha 1-adrenoceptor subtypes". British Journal of Pharmacology. 116 (1): 1611–1618. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb16381.x. PMC 1908909. PMID 8564227.

- ^ Ruffolo RR, Waddell JE (July 1982). "Receptor interactions of imidazolines. IX. Cirazoline is an alpha-1 adrenergic agonist and an alpha-2 adrenergic antagonist". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 222 (1): 29–36. doi:10.1016/S0022-3565(25)33148-4. PMID 6123592.

- ^ Shen H (2008). Illustrated Pharmacology Memory Cards: PharMnemonics. Minireview. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-59541-101-3.

- ^ MeSH list of agents 82000316

- ^ Lewis SR, Nicholson A, Smith AF, Alderson P (August 2015). "Alpha-2 adrenergic agonists for the prevention of shivering following general anaesthesia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015 (8) CD011107. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011107.pub2. PMC 9221859. PMID 26256531.

- ^ Duncan D, Sankar A, Beattie WS, Wijeysundera DN (March 2018). "Alpha-2 adrenergic agonists for the prevention of cardiac complications among adults undergoing surgery". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (3) CD004126. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004126.pub3. PMC 6494272. PMID 29509957.

- ^ Coghill D (2022). "The Benefits and Limitations of Stimulants in Treating ADHD". New Discoveries in the Behavioral Neuroscience of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. Vol. 57. Springer International Publishing. pp. 51–77. doi:10.1007/7854_2022_331. ISBN 978-3-031-11802-9. PMID 35503597.

External links

[edit] Media related to Alpha agonists at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Alpha agonists at Wikimedia Commons- Adrenergic+alpha-Agonists at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)