Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Altishahr

View on Wikipedia

Altishahr (Traditional Uyghur: آلتی شهر, Modern Uyghur: ئالتە شەھەر, Uyghur Cyrillic: Алтә-шәһәр; romanized: Altä-şähär or Alti-şähär),[1] also known as Kashgaria,[2][3] or Yettishar is a historical name for the Tarim Basin region used in the 18th and 19th centuries. The term means "Six Cities" in Turkic languages, referring to oasis towns along the rim of the Tarim, including Kashgar, in what is now southern Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China.[4][5][6][7][8][9]

Etymology

[edit]The name Altishahr is derived from the Turkic word Alti ('Six') and Persian word shahr ('city').[10] The Altishahr term was used by Turkic-speaking inhabitants of the Tarim Basin in the 18th and 19th century,[10][11] and adopted by some Western sources in the 19th century.[10]

Other local words for the region included Dorben Shahr ('Four Cities') and Yeti Shahr ('Seven Cities').[10][11] Another Western term for the same region is Kashgaria.[10] Qing sources refer to the region primarily as Nanlu, or the 'Southern Circuit'.[10] Other Qing terms for the region include Huijiang (回疆, the 'Muslim Frontier'), Huibu (回部, the 'Muslim Region'), Bacheng (the 'Eight Cities'),[10] or Nanjiang ('Southern Frontier').[12]

Onomatology

[edit]

In the 18th century, prior to the Qing conquest of Xinjiang in 1759, the oasis towns around the Tarim did not have a single political structure governing them, and Altishahr referred to the region in general rather than any cities in particular.[13] Foreign visitors to the region would attempt to identify the cities, offering various lists.[13]

According to Albert von Le Coq, the 'Six Cities' (Altishahr) referred to (1) Kashgar; (2) Maralbexi (Maralbashi, Bachu); (3) Aksu (Aqsu), alternatively Kargilik (Yecheng); (4) Yengisar (Yengi Hisar); (5) Yarkant (Yarkand, Shache); and (6) Khotan.[13] W. Barthold later replaced Yengisar with Kucha (Kuqa).[13] According to Aurel Stein, in the early 20th century, Qing administrators used the term to describe the oasis towns around Khotan, including Khotan itself, along with (2) Yurungqash, (3) Karakax (Qaraqash, Moyu), (4) Qira (Chira, Cele), (5) Keriya (Yutian), and a sixth undocumented place.[13]

The term 'Seven Cities' may have been used after Yaqub Beg captured Turpan (Turfan), and referred to (1) Kashgar; (2) Yarkant; (3) Khotan; (4) Uqturpan (Uch Turfan); (5) Aksu; (6) Kucha; and (7) Turpan.[13]

The term 'Eight Cities' (Uyghur Cyrillic: Шәкиз Шәһәр, Şäkiz Şähār) may have been a Turkic translation of the Qing Chinese term Nanlu Bajiang (literally 'Eight Cities of the Southern Circuit'), referring to (1) Kashgar, (2) Yengisar (3) Yarkant and (4) Khotan in the west and (5) Uqturpan, (6) Aksu, (7) Karasahr (Qarashahr, Yanqi), and (8) Turpan in the east.[13]

Geography and relation to Xinjiang

[edit]

Altishahr refers to the Tarim Basin of Southern Xinjiang, which was historically, geographically, and ethnically distinct from the Junggar Basin of Dzungaria. At the time of the Qing conquest in 1759, Dzungaria was inhabited by Oirats, steppe-dwelling, nomadic Mongols who practiced Tibetan Buddhism. In contrast, the Tarim Basin was inhabited by sedentary, oasis-dwelling, Turkic-speaking Muslim farmers, now known as the Uyghurs. The two regions were governed as separate circuits before the region became independent. Xinjiang was made into a single province in 1884.

History

[edit]Until the 8th century AD, much of the Tarim Basin was inhabited by Tocharians who spoke an Indo-European language and built city states in the oases along the rim of the Taklamakan Desert. The collapse of the Uyghur Khanate in modern Mongolia and settlement of Uyghur diaspora in the Tarim led to the prevalence of the Turkic languages. During the reign of the Karakhanids much of the region converted to Islam. From the 13th to the 16th centuries, the western Tarim was part of the larger Muslim Turkic-Mongol Chaghatay, Timurid and Eastern Chagatai Empires.

In the 17th century, the local Yarkent Khanate ruled Altishahr until its conquest by the Buddhist Dzungars from the Dzungarian Basin to the north. In the 1750s, the region was acquired by the Qing dynasty in its conquest of the Dzungar Khanate. The Qing initially administered the Dzungaria and Altishahar separately as the Northern and Southern Circuits of Tian Shan, respectively,[14][15][16][17] although both were under control of the General of Ili. The Southern Circuit (Tianshan Nanlu) was also known as Huibu (回部, 'Muslim Region'), Huijiang (回疆, 'Muslim Frontier'), Chinese Turkestan, Kashgaria, Little Bukharia, and East Turkestan. After quelling the Dungan Revolt in the late 19th century, the Qing combined the two circuits into the newly created Xinjiang Province in 1884. Xinjiang has since been used by the Republic of China and People's Republic of China and Southern Xinjiang replaced Altishahr as place name for the region.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Brophy, David (4 April 2016). Uyghur Nation: Reform and Revolution on the Russia-China Frontier. Harvard University Press. pp. 319–. ISBN 978-0-674-97046-5.

- ^ Onuma, Takahiro. 2017. "The 1795 Khoqand Mission and Its Negotiations with the Qing." Pp. 91–115 in Kashgar Revisited: Uyghur Studies in Memory of Ambassador Gunnar Jarring, edited by I. Bellér-Hann, B. N. Schlyter, and J. Sugawara. Leiden: Brill. doi:10.1163/9789004330078_007.

- ^ René Grousset (1970). The empire of the steppes: a history of central Asia. Rutgers University Press. p. 344. ISBN 978-0-8135-0627-2.

- ^ ed. Bellér-Hann 2007, p. 5.

- ^ Jonathan Neaman Lipman (1 July 1998). Familiar strangers: a history of Muslims in Northwest China. University of Washington Press. pp. 59–. ISBN 978-0-295-80055-4.

- ^ Enze Han (19 September 2013). Contestation and Adaptation: The Politics of National Identity in China. OUP USA. pp. 160–. ISBN 978-0-19-993629-8.

- ^ Ildikó Bellér-Hann (2008). Community Matters in Xinjiang, 1880-1949: Towards a Historical Anthropology of the Uyghur. BRILL. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-90-04-16675-2.

- ^ Justin Jon Rudelson; Justin Ben-Adam Rudelson (1997). Oasis Identities: Uyghur Nationalism Along China's Silk Road. Columbia University Press. pp. 31–. ISBN 978-0-231-10786-0.

- ^ Justin Jon Rudelson; Justin Ben-Adam Rudelson (1992). Bones in the Sand: The Struggle to Create Uighur Nationalist Ideologies in Xinjiang, China. Harvard University. p. 43.

- ^ a b c d e f g Newby 2005: 4 n.10

- ^ a b Canfield, Robert Leroy (2010). Ethnicity, Authority, and Power in Central Asia: New Games Great and Small. Taylor & Francis. p. 45.

- ^ S. Frederick Starr (15 March 2004). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 30–. ISBN 978-0-7656-3192-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bellér-Hann 2008: 39 nn.7 & 8

- ^ Michell 1870, p. 2.

- ^ Martin 1847, p. 21.

- ^ Fisher 1852, p. 554.

- ^ The Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and General Literature, Volume 23 1852, p. 681.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bellér-Hann, Ildikó, ed. (2007). Situating the Uyghurs Between China and Central Asia (illustrated ed.). Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-0754670414. ISSN 1759-5290. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Bellér-Hann, Ildikó (2008). Community Matters in Xinjiang, 1880-1949: Towards a Historical Anthropology of the Uyghur. Brill. ISBN 978-9004166752.

- Dani, Ahmad Hasan; Masson, Vadim Mikhaĭlovich; Unesco, eds. (2003). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Development in contrast : from the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century. Multiple history series. Vol. 5 of History of Civilizations of Central Asia (illustrated ed.). UNESCO. ISBN 9231038761. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Kim, Kwangmin (2008). Saintly Brokers: Uyghur Muslims, Trade, and the Making of Qing Central Asia, 1696--1814. University of California, Berkeley. ISBN 978-1109101263. Archived from the original on 4 December 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Edme Mentelle; Malte Conrad Brun; Pierre-Etienne Herbin de Halle (1804). Géographie mathématique, physique & politique de toutes les parties du monde, Volume 12. H. Tardieu. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Millward, James A. (1998). Beyond the Pass: Economy, Ethnicity, and Empire in Qing Central Asia, 1759-1864 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804729336. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Millward, James A. (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231139243. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Newby, L. J. (1998). "The Begs of Xinjiang: Between Two Worlds". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 61 (2). Cambridge University Press on behalf of School of Oriental and African Studies: 278–297. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00013811. JSTOR 3107653.

- Newby, L.J. (2005). The Empire And the Khanate: A Political History of Qing Relations With Khoqand C1760-1860. Brill. ISBN 9004145508.

- Starr, S. Frederick, ed. (2004). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 0765613182. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

Further reading

[edit]Altishahr

View on GrokipediaEtymology and Terminology

Name Origins

The name Altishahr (Uyghur: ئالتىشەھەر, Altishahar) literally translates to "six cities," derived from the Turkic term alti ("six") and the Persian-influenced shahr ("city" or "town"), reflecting its use among Turkic-speaking Muslim communities in the Tarim Basin oases.[7][1] This etymology underscores the region's historical conceptualization as a network of discrete urban hubs amid desert expanses, with the "six" conventionally alluding to major settlements like Kashgar, Yarkand, Hotan, Aksu, Kucha, and Karashar, though local accounts recognized additional centers and lacked consensus on the precise roster.[7] The term's Persian element highlights linguistic influences from earlier Islamic scholarship and administration in Central Asia, where shahr denoted fortified or administrative cities, adapting to Turkic contexts by the medieval period.[8] While predating modern Uyghur ethnogenesis, Altishahr emerged as an indigenous toponym among Tarim Basin Muslims by at least the 17th century, contrasting with northern steppe designations like Yette Shahr ("seven cities").[6]Historical and Modern Usage

The term Altishahr, derived from Uyghur altı shahr meaning "six cities," denoted the primary oases of the Tarim Basin, specifically Kashgar, Yarkand, Khotan, Aksu, Kucha, and Turpan, which sustained sedentary Turkic Muslim communities amid the surrounding Taklamakan Desert.[9][10] This designation emerged among the region's Turkic-speaking inhabitants by the 17th century, contrasting the oasis-based polities of southern Xinjiang with the pastoral Zunghar territories to the north.[7] Historically, Altishahr encapsulated the fragmented yet interconnected city-states under local Khoja rulers, which the Qing dynasty conquered between 1755 and 1759, integrating them into the broader Huijiang administrative framework alongside Zungharia.[11] In the 19th century, Altishahr persisted in local usage among Uyghur and other Turkic populations to describe their homeland in the Tarim Basin, even as Qing gazetteers like the Huijiang zhi documented the region under imperial oversight.[12] Western explorers and sinologists adopted the term during this period to refer to the southern oases, highlighting their distinct cultural and economic orientation toward Central Asian Islamic networks rather than the steppe frontiers.[13] Contemporary usage of Altishahr endures in academic analyses and Uyghur diaspora discourse to precisely identify the Tarim Basin as the core historical Uyghur settlement area, comprising the southern portion of modern Xinjiang where Uyghurs constitute the demographic majority.[14] Scholars employ it to underscore the region's pre-modern autonomy and oasis-centric identity, separate from northern Xinjiang's nomadic legacies, though official Chinese nomenclature favors "Xinjiang" encompassing both.[2] At the turn of the 20th century, inhabitants of Altishahr increasingly articulated a shared Turkic Muslim consciousness, influencing modern ethno-nationalist interpretations of the term.[14]Geography

Physical Landscape

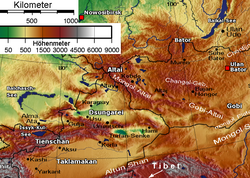

Altishahr comprises the southern portion of the Tarim Basin, an endorheic sedimentary basin characterized by a flat, low-lying topography enclosed by formidable mountain ranges. The northern margin is defined by the Tian Shan Mountains, the southern by the Kunlun Mountains, and the western by the Pamir Plateau, creating a rain shadow that exacerbates aridity across the region.[9] [15] Elevations within the basin generally range from 800 to 1,500 meters above sea level, with the central expanse dominated by the expansive Taklamakan Desert, featuring vast dune fields and shifting sands. Seasonal meltwater from glacial sources in the encircling highlands feeds ephemeral rivers, such as tributaries of the Tarim River, which originate in the Tian Shan and Kunlun ranges before dissipating into the desert interior. These waterways sustain narrow ribbons of fertile oases amid the hyper-arid surroundings, enabling historical agricultural settlements in areas like Kashgar and Hotan.[16] [17] [18] The climate is marked by extreme continentality and minimal annual precipitation, typically under 50 mm in the desert core, due to orographic barriers blocking moist air masses. Summer daytime temperatures frequently surpass 40°C, while winters bring sub-zero conditions and periodic frost, with the Tarim River freezing from December to March in some reaches. Vegetation is sparse, confined largely to salt-tolerant shrubs and riparian zones along oases, underscoring the basin's reliance on irrigation for habitability.[15] [19]Boundaries and Relation to Xinjiang

Altishahr encompasses the Tarim Basin, a vast endorheic basin in southern Xinjiang bounded by the Tian Shan mountains to the north, the Kunlun Mountains to the south, the Pamir range to the southwest, and extending eastward toward the Lop Nor basin.[9] The Taklamakan Desert occupies its central expanse, isolating northern and southern oasis networks historically centered on six key cities: Kashgar, Yarkand, Aksu, Kucha, Karashar, and Turpan.[20] Geographically and ethnically distinct from the northern Dzungarian Basin's steppe landscapes and nomadic populations, Altishahr featured sedentary Turkic-Muslim communities in irrigated oases.[14] The Qing Dynasty conquered Altishahr in 1759 after defeating the Dzungar Khanate, incorporating its urban centers alongside the northern territories into imperial administration.[14] In the modern context, Altishahr aligns with southern Xinjiang within the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, which spans over 1.6 million square kilometers and integrates both the Tarim Basin and Dzungaria.[21] Following 19th-century revolts and reconquest by 1877, the Qing formalized unified governance by establishing Xinjiang Province in 1884, designating the combined regions as a "new frontier."[21] This administrative consolidation persisted through the Republican era and into the People's Republic, despite historical separations in pre-Qing polities.[21]Demographics

Ethnic Groups and Historical Migrations

Altishahr's population is predominantly Uyghur, a Turkic ethnic group that constitutes the majority in the region's oases, including Kashgar, Yarkand, Hotan, Aksu, Kucha, and Karashahr, reflecting their historical settlement patterns in the Tarim Basin.[14] Minority groups include Pamiri Tajiks in the southwestern mountain areas, such as Taxkorgan, who speak Eastern Iranian languages and maintain distinct cultural practices, as well as smaller communities of Kyrgyz nomads in the highlands and Hui Muslims in trading centers.[14] These demographics stem from layered historical settlements, with Uyghurs forming over 80% of the southern Xinjiang population as of recent censuses, though intermixing and modern migrations have introduced Han Chinese elements in urban peripheries.[14] Prior to Turkic dominance, the Tarim Basin hosted Indo-European-speaking populations from the Bronze Age onward, including Tocharians in the northern and central oases like Kucha and Karashahr, who practiced Buddhism and left linguistic records in Tocharian A and B languages documented in manuscripts from the 5th to 8th centuries CE.[22] Southern areas, such as Hotan and Yarkand, were inhabited by Eastern Iranian Saka groups, evidenced by archaeological sites and Khotanese Saka texts from the 5th to 10th centuries CE.[23] Genomic analysis of Bronze Age mummies from sites like Xiaohe (circa 2000–1500 BCE) reveals a local population with primarily ancient North Eurasian and Baikal-related East Asian ancestry, distinct from steppe pastoralist migrations like Afanasievo, indicating indigenous continuity rather than wholesale replacement.[24] The defining migration shaping modern ethnic groups began after the destruction of the Uyghur Khaganate in Mongolia by Kyrgyz forces in 840 CE, prompting nomadic Uyghur tribes—originally from the Orkhon Valley—to relocate southward into the Tarim Basin's oases over the following centuries.[25] These migrants, speaking an early form of Turkic, intermarried with residual Indo-European locals, adopted oasis agriculture and Buddhism initially, and established the Uyghur Idiqut state (Kingdom of Qocho) by the 9th century, centered in the Turfan depression but extending influence to Altishahr's cities.[25] Concurrently, Karluk Turks infiltrated from the west, contributing to the ethnogenesis of contemporary Uyghurs through linguistic and genetic admixture, as confirmed by studies showing modern Uyghur DNA blending ancient Tarim Basin locals with post-840 CE Turkic inputs.[25] [24] By the 10th–11th centuries, further Turkic migrations, including Oghuz and Qarluk groups under the Karakhanid Khanate, accelerated Turkicization and Islamization, displacing or assimilating Tocharian and Iranian remnants, with Uyghur as the consolidated ethno-linguistic identity emerging by the 15th century amid Chagatai Turkic cultural synthesis.[25] Later influxes, such as Mongol elements during the 13th-century conquests and limited Tibetan Buddhist Dzungar presence until the Qing campaigns of 1755–1759, added minor genetic layers but did not alter Uyghur predominance in the core oases.[14] This migratory history underscores Altishahr's role as a crossroads, where Turkic settlers overlaid but did not eradicate pre-existing substrates, fostering a hybrid demographic resilient to subsequent imperial integrations.[25]Population Dynamics

The population of Altishahr, confined largely to the Tarim Basin oases, has long exhibited low density due to environmental constraints and intermittent conflict, with historical observers in the 19th century describing the region as underpopulated relative to its irrigable land potential, estimated at around 200,000 for key centers like Hotan alone.[26] Qing-era stabilization after the 1759 conquest enabled modest growth through agricultural expansion and reduced raiding, though reliable aggregates remain elusive, reflecting traditional census methods focused on taxable households rather than total inhabitants. By the late 19th century, the combined oases supported perhaps 1 million people, predominantly Turkic Muslims, sustained by cotton, grain, and Silk Road commerce.[27] Incorporation into the People's Republic of China in 1949 marked accelerated dynamics, with southern Xinjiang's population—encompassing Altishahr—rising from roughly 3.65 million in 1953 (75% Uyghur regionally) to over 10 million by 2000, driven by declining mortality, high fertility (averaging 6-7 births per woman pre-1970s), and limited in-migration compared to the north.[27] [28] Uyghur numbers increased absolutely from 3.61 million across Xinjiang in 1953 to 11.62 million in 2020, maintaining dominance in southern prefectures like Kashgar (91% Uyghur, population 3.35 million in 2000) and Hotan, where Han settlement focused on administration and infrastructure rather than mass relocation.[27] [28] Recent trends show fertility convergence, with Uyghur rates dropping from 4.37 in 1980 to below replacement by the 2010s under family planning enforcement, contrasting Han rates and prompting projections of 4.5 million fewer Uyghur births by 2040 if disparities persist.[29] [28] This shift, amid state policies promoting "optimized" ethnic structures, has fueled debates over voluntary versus coercive elements, with official data emphasizing overall prosperity and ethnic harmony post-1949.[30] [28] Urbanization and economic incentives continue to draw some Han to southern cities, but Altishahr's demographics retain a Uyghur core, with 2020 estimates exceeding 12 million in the four core prefectures.[27]History

Ancient and Pre-Uyghur Eras

The Tarim Basin oases, encompassing the historical region of Altishahr, show evidence of early human settlement from the Neolithic period, with pastoralist communities emerging by the early Bronze Age. Archaeological excavations have uncovered cemetery sites such as Xiaohe, dating to approximately 2100–1700 BCE, containing naturally preserved mummies with Caucasian-like features, including light hair and European-style clothing such as woolen boats and wheat agriculture.[24] Genomic studies of these Tarim Basin mummies reveal an autochthonous population with primary ancestry linked to Ancient North Eurasian-related groups from the Baikal region, lacking the Western Steppe pastoralist admixture typical of contemporaneous Afanasievo culture to the north; this suggests local continuity from hunter-gatherer forebears rather than large-scale migration from the Pontic-Caspian steppe.[24] Linguistic evidence points to these early inhabitants likely speaking proto-Tocharian languages, an Indo-European branch isolated in the basin, supported by later textual records and toponyms.[31] By the late Bronze and early Iron Ages (circa 1000–500 BCE), the southern Tarim oases developed into semi-urban settlements influenced by interactions with neighboring steppe nomads, including possible Saka (Eastern Scythian) groups. The Kingdom of Khotan, centered in the modern Hotan oasis, emerged as a prominent polity around the 3rd century BCE, with its ruling elite speaking Khotanese, an Eastern Iranian language of the Indo-European family.[32] Chinese annals from the Han dynasty (2nd century BCE) first document Khotan as one of thirty-six kingdoms in the Western Regions, noting its role in jade trade and early Buddhist adoption, potentially introduced via Indian or Central Asian missionaries by the 1st century BCE.[32] Similarly, the Shule kingdom around Kashgar exhibited comparable Indo-Iranian cultural traits, with fortifications and irrigation systems supporting oasis agriculture amid the Taklamakan Desert.[33] During the early centuries CE, Altishahr's city-states experienced successive foreign influences, including Han Chinese military expeditions establishing the Western Protectorate in 60 BCE, which briefly imposed tributary relations until the 1st century CE.[32] The Yuezhi, possibly originating from the Tarim fringes, migrated westward around 176–160 BCE, displacing the Saka and contributing to the Kushan Empire's formation in northern India, while leaving cultural imprints like coinage and Zoroastrian elements in Khotan.[32] By the 5th–7th centuries CE, Mahayana Buddhism dominated, with Khotan hosting major monasteries and serving as a Silk Road conduit for texts, art, and pilgrims; Chinese pilgrim Faxian recorded over 4,000 monks there circa 400 CE.[34] Tibetan incursions from the 7th century onward eroded Tang Chinese suzerainty (restored intermittently from 640–670 CE), setting the stage for Turkic nomadic pressures, though the core populations remained Indo-European speakers practicing Buddhism until the 8th century.[32]Uyghur Settlement and Islamicization

The collapse of the Uyghur Khaganate in 840 CE, following its defeat by the Kyrgyz tribes, prompted the mass migration of Uyghur populations from the Mongolian steppes toward the Tarim Basin, where groups settled among the oases of both northern and southern regions, including the southern Altishahr area encompassing cities like Kashgar and Yarkand.[35] These migrants, fleeing southward, intermingled with indigenous populations such as the Indo-European Tocharians and Sogdians, gradually Turkicizing the linguistic and cultural landscape of the Tarim oases through intermarriage and assimilation over the 9th and 10th centuries.[36] In the southern oases, Uyghur-related Turkic tribes, particularly Karluks who later contributed to Uyghur ethnogenesis, established dominance amid fragmented local kingdoms, laying the foundation for sedentary Uyghur communities adapted to oasis agriculture and trade.[37] The Kara-Khanid Khanate, emerging around 840 CE from a confederation of Turkic tribes including Uyghur elements in the Kashgar and Ferghana regions, accelerated Uyghur settlement in Altishahr by consolidating control over the southern Tarim oases through military expansion and alliances.[38] This khanate's rulers fostered the integration of nomadic Turkic groups into the oasis economies, promoting permanent settlements that evolved into the urban centers of Altishahr, with populations relying on irrigated farming of wheat, cotton, and fruits alongside caravan trade.[39] Islamicization of Altishahr commenced with the Kara-Khanid Khanate's adoption of Sunni Islam, initiated by the conversion of its ruler Satuq Bughra Khan around 934 CE, marking the first instance of a Turkic sovereign embracing the faith and initiating proselytization among his subjects.[38] This shift propelled missionary activities and jihads, culminating in the conquest of the Buddhist Kingdom of Khotan by Yusuf Qadir Khan circa 1006 CE, which eliminated major non-Muslim strongholds in the southern Tarim Basin and facilitated the rapid spread of Islam through intermarriage, taxation incentives for converts, and suppression of Buddhist institutions.[40] Although pockets of Buddhism and Manichaeism persisted into the 14th century in remote oases, the process was largely complete by the 15th century, transforming Altishahr into a predominantly Muslim region with Uyghur Turks forming the core sedentary population under Islamic legal and cultural frameworks.[40]Khanates and External Conquests

The Yarkand Khanate, founded in 1514 by Sa'id Khan, a Chagatai descendant from the eastern Moghulistan branch, unified the oases of Altishahr through conquests starting from Kashgar and extending to Yarkand, Khotan, and Aksu by 1516.[41] Sa'id Khan, invited by local Muslim leaders to counter non-Chagatai rulers, established a Sunni Turkic-Mongol dynasty that emphasized Islamic governance and patronized scholars, consolidating control over the Tarim Basin's six primary cities—Kashgar, Yarkand, Khotan, Aksu, Yangihisar, and Uch Turpan—amid fragmentation following the Timurid collapse.[41] Under Abd al-Rashid Khan (r. 1533–1565), the khanate reached its zenith, incorporating Turpan Khanate territories by 1563 and fostering trade along Silk Road routes, with annual revenues estimated at over 1 million tanga in silver from oasis agriculture and caravans.[42] Successive rulers faced internal challenges, including succession disputes and influence from Naqshbandi Sufi networks like the Khojas, who wielded spiritual authority over temporal khans. By the mid-17th century, the khanate's power waned due to factional strife between Afaqi (descendants of Makhdum-i A'zam) and Ishaqi Khoja lineages, exacerbating economic strains from over-taxation and raids by Kazakh nomads. In 1677, during a revolt against the unpopular Khan Ismail, Afaqi Khoja Hidayat Allah invited Dzungar intervention, prompting Batur Khongtaiji's forces to invade Altishahr. The Dzungar conquest unfolded from 1678 to 1680, with Dzungar cavalry overwhelming Yarkand defenses; Khan Ismail was captured and executed in 1680, marking the effective end of independent Chagatai rule in Altishahr.[43] The Tibetan Buddhist Dzungars, originating from the Ili Valley, subjugated the region as a vassal territory, imposing heavy tribute—reportedly 100,000 sheep and vast grain levies annually—while stationing garrisons in key oases and suppressing Islamic practices to assert dominance over the Uyghur Muslim population.[43] This external conquest integrated Altishahr into the Dzungar Khanate's domain, disrupting local khanate structures and fueling Khoja-led resistance, though nominal puppet rulers persisted in some areas until around 1705.[42] Dzungar overlordship prioritized resource extraction for steppe warfare, contrasting with the khanate's oasis-centric administration, and sowed seeds for later revolts by exacerbating ethnic and religious tensions.Qing Conquest and Modern Integration

The Qing dynasty's conquest of Altishahr occurred as part of the broader Dzungar–Qing Wars, culminating between 1757 and 1759. Following the defeat of the Dzungar Khanate in northern Xinjiang (Dzungaria) by 1757, Qing forces under generals like Agui advanced southward into the Tarim Basin oases, subduing local Khoja leaders who had briefly asserted independence amid Dzungar collapse. By October 1759, the Qing had captured key cities including Kashgar, Yarkand, and Hotan, establishing direct imperial control over Altishahr after suppressing resistance from Afaqi Khoja forces.[44][45] Qing administration integrated Altishahr through a system of military garrisons, agricultural colonies (tuntian), and a hierarchical beg bureaucracy, where local Muslim elites (beks) managed taxation, justice, and agriculture under Manchu oversight. The Qianlong Emperor formalized the region as Xinjiang ("New Frontier") in 1760, dividing Altishahr into eighteen xian (districts) grouped under three beglerbegi (governors) in Kashgar, Yarkand, and Hotan, with an ambans stationed in key cities to enforce loyalty. This structure maintained Islamic practices but imposed Qing fiscal policies, including land surveys and corvée labor, fostering relative stability until the Dungan Revolt of 1864.[46][47] After the Qing dynasty's collapse in 1912, Xinjiang fragmented under Republican warlords, with Yang Zengxin ruling from 1912 to 1928 and Sheng Shicai from 1933 to 1944, who alternately aligned with Soviet and Nationalist Chinese interests while suppressing local unrest. The People's Republic of China incorporated Xinjiang in 1949 following the defeat of Sheng's regime and the short-lived Ili Rebellion coalition, establishing the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in 1955 to formalize ethnic administration amid Han Chinese migration and infrastructure projects.[48][49] Modern integration has emphasized economic development, with state-led initiatives since the 1950s promoting resource extraction, rail links like the Lanzhou–Ürümqi–Korla Railway (completed 1962), and agricultural expansion, increasing Xinjiang's GDP contribution to China's economy while altering demographic balances through subsidized Han settlement. These policies, justified as advancing multi-ethnic unity, have involved centralized control over local governance, reducing traditional Uyghur authority structures in favor of party-state mechanisms.[50][51]

Culture and Religion

Uyghur Cultural Elements

Uyghur culture in Altishahr, the historical region encompassing oases such as Kashgar, Yarkand, and Khotan, reflects a synthesis of Turkic nomadic heritage, Persian influences, and Islamic traditions adapted to the Tarim Basin's sedentary agrarian life. Central to this are oral epics, storytelling, and artisanal crafts like carpet weaving and knife-making, which emphasize intricate geometric patterns and motifs drawn from desert landscapes and Islamic symbolism. These elements persisted through centuries of rule by khanates and later Qing administration, maintaining continuity despite external pressures.[52] The Uyghur language, a Karluk branch of Turkic languages, dominates in Altishahr, with southern dialects spoken in cities like Kashgar and Yarkand featuring distinct phonetic traits such as softer vowels and vocabulary influenced by Persian and Arabic loanwords related to religion and trade. These dialects differ from northern variants, incorporating local toponyms and agricultural terms tied to oasis farming, and are primarily written in a modified Arabic script historically used for religious texts and poetry. Literacy in these dialects supported a rich manuscript tradition of mystical literature and chronicles.[14] Performing arts form a cornerstone, exemplified by the Xinjiang Uyghur Muqam, recognized by UNESCO in 2005 as an intangible cultural heritage comprising twelve suites of songs, dances, and instrumental pieces performed on lutes like the satar and drums like the dutar. In southern Xinjiang, Muqam variants from Kashgar emphasize rhythmic complexity and narrative poetry recounting heroic tales, often accompanied by group dances with synchronized hand gestures and footwork evoking caravan movements. Folk dances, such as those in Hotan and Kuqa, prioritize improvisational elements tied to wedding and harvest celebrations, blending athletic spins with lyrical expressions of emotion.[53][54] Cuisine in Altishahr revolves around wheat-based staples and lamb, with dishes like polo—a pilaf of rice, carrots, raisins, and mutton—served communally during gatherings, reflecting Islamic halal practices and Silk Road exchanges. Breads such as nan, baked in tandoor ovens, and yogurt-based drinks like ayran accompany meals, while sweets like halvah incorporate sesame and honey. These foods underscore seasonal abundance from oasis irrigation, with techniques preserved through family transmission.[55] Traditional attire includes the doppa, a square embroidered skullcap for men denoting regional styles—Kashgar variants feature floral silk threads symbolizing prosperity—and colorful atlas silk robes for women, dyed with saffron and indigo from local plants. Festivals reinforce these elements: Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha involve mosque prayers, feasting on sacrificed sheep, and communal dances in Yarkand and Kashgar, while mazar shrine pilgrimages at sites like Imam Asim in Khotan feature Muqam recitals and vows for fertility or health, drawing pilgrims for multi-day events with poetry recitation. Nowruz, marking spring equinox around March 21, includes picnics, egg-tapping games, and semi-religious rituals blending pre-Islamic Zoroastrian roots with Sunni observance.[56][57]Islamic Influence and Practices

Islam arrived in Altishahr, the Tarim Basin oases, through trade routes and conquests by Turkic Muslim dynasties, with the Kara-Khanid Khanate initiating widespread conversions among sedentary Turkic populations from the 10th century onward, establishing Sunni Islam of the Hanafi madhhab as the prevailing school.[14] By the 16th century, under the Yarkand Khanate and influence of Naqshbandi Sufi missionaries like Ahmad Kasani (Makhdum-i Azam, 1461–1542), the region's inhabitants, including Uyghur-speaking communities, had largely abandoned Buddhism and other prior faiths for Islam, integrating it into oasis-based social structures.[58] This process was gradual, driven by intermarriage, missionary activity, and political alliances rather than coercion, as evidenced by the persistence of pre-Islamic elements in folklore until later centuries.[13] Sufism, particularly the Naqshbandi order, profoundly shaped Islamic practices in Altishahr, with khojas—hereditary religious leaders claiming descent from the Prophet Muhammad—serving as spiritual guides, judges, and political influencers from the late 16th century.[59] The order emphasized silent dhikr (remembrance of God), adherence to sharia, and community welfare, fostering networks across oases like Kashgar and Yarkand; these tariqas (Sufi paths) organized initiations, charitable endowments (waqfs), and dispute resolution outside formal khanate courts. Key sites included the Apak Khoja Mausoleum in Kashgar, built around 1640 as a burial complex for Naqshbandi leaders, which drew pilgrims for ziyarat (visitation rituals) involving prayer, supplication at saints' tombs, and seasonal festivals commemorating figures like Afaq Khoja (1626–1694).[60] Such practices mirrored Central Asian norms, blending orthodox rituals like the five daily salat and Ramadan fasting with esoteric elements, though rival khoja factions (e.g., White and Black Mountains) occasionally sparked intra-Muslim conflicts over succession and doctrine.[61] Daily and communal observances centered on mosques (masjids) as hubs for education, where mullas taught Quranic exegesis, fiqh, and Turkic-Arabic literacy; Friday jumu'ah prayers reinforced communal solidarity, often accompanied by khutbahs addressing local governance.[62] Lifecycle rites—circumcision (sunnat), marriage contracts (nikah) with mahr stipends, and funerals with collective janazah—adhered to Hanafi rites, while Sufi influences promoted ethical conduct via silsila (chain of transmission) recitations.[58] Pre-Qing autonomy allowed these practices to evolve indigenously, with minimal Wahhabi or Salafi intrusion until 20th-century external contacts, preserving a syncretic form attuned to agrarian oasis life rather than urban scholasticism.[13]Economy and Trade

Historical Silk Road Significance

Altishahr, encompassing the oases of Kashgar, Yarkand, Khotan, Aksu, and Kucha in the Tarim Basin, formed critical nodes on the southern branch of the Silk Road, facilitating overland trade between China and the West from the 2nd century BCE onward. These settlements, sustained by rivers flowing from the surrounding mountains, enabled caravans to circumvent the Taklamakan Desert, exchanging Chinese silk for western commodities such as horses, glassware, and precious stones. Khotan, in particular, emerged as a renowned source of jade and fine silks, with its kingdom controlling key passes and contributing to the safeguarding of trade routes as noted in ancient records of interactions with the Han dynasty.[63][64] Kashgar served as a primary convergence point where northern and southern routes intersected, allowing merchants to proceed to Central Asia, India, and beyond, while Yarkand acted as an intermediary station linking Kashgar to Khotan and branching northward to Aksu. This network not only propelled economic exchange but also disseminated technologies, religions, and ideas; for instance, Buddhism propagated westward from India through Khotan and eastward into China via these oases, with archaeological evidence from sites like Kucha revealing extensive monastic complexes tied to trade prosperity. The region's strategic position amplified its role during periods of empire expansion, such as under the Kushans and Tang, when control over Altishahr ensured dominance over trans-Eurasian commerce.[65][66][67] Trade volumes peaked between the 1st and 8th centuries CE, with Altishahr's markets handling diverse goods including spices, textiles, and metals, though disruptions from nomadic incursions and shifting political powers periodically altered flows. By the medieval era, Islamic influences integrated into the trade framework following the conversion of these kingdoms, yet the oases retained their centrality until maritime routes diminished overland traffic in the 15th century. Historical gazetteers and traveler accounts underscore Altishahr's enduring significance as a cultural and economic crossroads, bridging Eastern and Western civilizations for over a millennium.[63][68]Contemporary Economic Role

The economy of Altishahr, encompassing the southern Tarim Basin oases such as Kashgar and Hotan, centers on resource extraction, agriculture, and emerging manufacturing, integrated within Xinjiang's broader framework as a key supplier of raw materials to China's national economy. The Tarim Basin hosts China's largest oil and gas reserves, estimated at 16 billion tonnes, with the Tarim oilfield driving significant production; in 2021, China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) reported new discoveries contributing to annual outputs exceeding 30 million tonnes of oil equivalent.[69] This sector underscores Altishahr's role in national energy security, with pipelines linking the basin to eastern China facilitating exports and domestic supply. Agriculture remains foundational, particularly oasis-based cultivation sustained by the Tarim River system, which supports over one-third of China's cotton output through irrigated farming in areas like Hotan and Kashgar.[70] Cotton, alongside grapes and other cash crops, dominates due to the region's arid climate and soil suited for long-staple varieties, positioning southern Xinjiang as China's primary cotton production base amid challenges like water scarcity.[71] Industrial development, spurred by state-led investments in special economic zones, has accelerated growth; Kashgar's GDP reached US$20.1 billion in 2023, quadrupling from 2010 levels through manufacturing and infrastructure projects like the southern Xinjiang "power expressway loop" completed in 2025, which enhanced connectivity and lifted regional GDP from 481.7 billion yuan in earlier baselines to support poverty alleviation efforts.[72][73] These initiatives aim for sustained expansion, with Xinjiang targeting high-quality development in 2025 via deepened reforms and resource utilization.[74]Political Status and Controversies

Uyghur Identity and Nationalism

The modern Uyghur ethnic identity, primarily associated with the sedentary Muslim populations of Altishahr's Tarim Basin oases, emerged as a self-conscious national construct in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when local Muslim intellectuals began rediscovering and appropriating the historical legacy of the 8th–9th century Uyghur Khaganate to unify diverse Turkic-speaking communities under a shared ethnonym.[75] This process involved blending Islamic, linguistic, and Turkic cultural elements with modernist reforms, distinguishing oasis dwellers from nomadic groups like Kazakhs and emphasizing descent from ancient Central Asian states rather than direct continuity with medieval nomads who had migrated southward after the khaganate's fall.[75] [76] Soviet nationalities policies post-1917 further shaped this identity among Xinjiang émigrés in Russia, where "Uyghuristan"—encompassing Altishahr—was promoted as a distinct territorial entity in the 1920s.[75] Influences from pan-Turkism, propagated via Ottoman reformers, and Jadidist movements in Russian Central Asia—stressing secular education, language standardization, and anti-colonial awakening—propelled nationalist sentiments among Altishahr's elites, who viewed Han Chinese expansion as a threat to local autonomy.[75] [76] By 1931, under Republican China's ethnic classification system and with Soviet advisory input, "Uyghur" was formalized to denote the Tarim Basin's Turkic Muslims, fostering petitions for self-rule and cultural preservation amid warlord governance.[76] Early expressions included protest literature by figures like Shair Akhun and Khislat Kashgari, decrying assimilation post-Qing conquest, which crystallized opposition around ethnic and religious lines.[76] Nationalist aspirations peaked with the Turkish-Islamic Republic of East Turkestan, declared on November 12, 1933, in Kashgar after uprisings against Sheng Shicai's regime and Hui warlord incursions, advocating independence through a blend of Turkic unity, sharia governance, and administrative modernism led by local jadidist-inspired insurgents.[76] [77] The short-lived state, lasting until February 1934 when suppressed by Chinese forces, highlighted Altishahr's role as a nationalist hearth, though internal factions between Islamists and secularists underscored tensions in the movement.[76] A parallel 1860s insurgency under Yakub Beg had briefly established a similar polity in Altishahr, invoking pan-Islamic solidarity against Qing rule until its collapse in 1877.[76] The Second East Turkestan Republic, proclaimed November 1944 in northern Xinjiang's Ili region amid anti-Sheng revolts, extended nationalist rhetoric southward, drawing Altishahr support for multi-ethnic Turkic self-determination under Soviet backing, with figures like Ehmetjan Qasim promoting autonomy before its 1949 incorporation into the People's Republic of China.[76] [78] Under PRC rule, Uyghur identity gained official status as a recognized nationality with nominal autonomy in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, yet nationalist currents—framed by Beijing as separatist threats—persisted underground, erupting in events like the April 1990 Baren Township clash, where insurgents sought Islamic governance.[76] Diaspora organizations, such as the World Uyghur Congress founded in 2004, continue to articulate nationalism through cultural advocacy and calls for self-determination, often citing historical republics as precedents against perceived assimilation.[76]Chinese Administration and Development

The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR), which includes the historical Altishahr area in the Tarim Basin, has been under the administration of the People's Republic of China since 1949, with the autonomous region formally established on October 1, 1955. Governance follows the PRC's unitary system, where the regional People's Congress and government chairmanship—often held by an ethnic Uyghur—operate under the overarching authority of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region Committee, led by a Party secretary typically appointed from Han Chinese cadres in Beijing. This structure emphasizes centralized control, with the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC, or Bingtuan), founded in 1954, exercising paramilitary, economic, and administrative functions, particularly in southern Xinjiang's oases like Kashgar and Hotan prefectures, where it manages over 7% of the region's land for agriculture and security.[79][80] Development initiatives in Altishahr have prioritized resource extraction, infrastructure, and poverty reduction, leveraging the Tarim Basin's oil, gas, and arable potential. The XPCC spearheaded land reclamation efforts post-1950s, expanding irrigated farmland from under 100,000 hectares in 1949 to over 600,000 hectares by the 1990s, focusing on cotton, wheat, and fruit production in southern prefectures.[81] More recently, energy infrastructure has accelerated: a 4,197-km extra-high-voltage power transmission loop encircling the Tarim Basin was completed in July 2025 to integrate renewable sources and stabilize supply for industrial growth, while a circumferential natural gas pipeline project commenced in April 2024 to exploit basin reserves exceeding 7 trillion cubic meters.[82][83] A 12.5-gigawatt solar and wind mega-base in the Taklamakan Desert, announced in 2024, aims to position southern Xinjiang as a green energy hub, reducing reliance on coal amid national carbon goals.[84] Population dynamics under this administration reflect state-driven migration and urbanization. The 2020 census recorded Xinjiang's total population at 25.85 million, up 18.1% from 2010, with Han Chinese growing 25.4% to 10.93 million—largely via economic migration—while Uyghurs increased 16.2% to 11.62 million; in southern Xinjiang, Han influx through XPCC settlements has risen from negligible pre-1949 levels to approximately 10-15% of local populations by 2020, facilitating labor for development projects but altering ethnic demographics.[85][86] Official narratives frame these as poverty alleviation successes, with per capita GDP in Hotan and Kashgar prefectures rising from ¥5,000 in 2000 to over ¥40,000 by 2023, supported by World Bank-backed irrigation in minority-heavy counties.[87] However, implementation has involved heightened security measures since 2014, including vocational training centers cited by PRC sources as countering extremism, though Western reports allege mass detentions exceeding one million, often relying on satellite imagery and defector accounts whose verifiability is contested by Beijing.[80][88]International Debates and Claims

Internationally, Altishahr is recognized as an integral part of China's Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, with no sovereign state or major international body disputing Chinese territorial control since the Qing dynasty's conquest in 1759.[89] The United Nations and all member states treat Xinjiang, including Altishahr, as sovereign Chinese territory, reflecting post-World War II norms on territorial integrity and the absence of widespread support for separatist claims.[90] Brief episodes of de facto independence, such as the First East Turkestan Islamic Republic (1933–1934) centered in Kashgar within Altishahr and the Second East Turkestan Republic (1944–1949) in northern Xinjiang, lacked international recognition and ended through military reintegration by Chinese forces.[91] Uyghur exile organizations, including the World Uyghur Congress, advocate for Altishahr's recognition as part of an independent East Turkestan, citing historical Uyghur cultural dominance in the Tarim Basin oases and periods of autonomy under figures like Yakub Beg (1865–1877).[91] These claims emphasize pre-Qing Turkic-Islamic rule and portray Chinese administration as colonial occupation, but they receive no formal endorsement from governments and are countered by China as threats to national unity amid past separatist violence, including the 1990 Baren uprising in Aksu Prefecture, Altishahr.[89] Diaspora narratives often frame Altishahr's six historical cities (Kashgar, Yarkand, Hotan, Aksu, Kucha, and Karashahr) as a distinct Uyghur homeland, yet empirical data shows continuous multi-ethnic settlement and economic integration under Chinese governance, with Uyghur population growth from approximately 7.2 million in 1990 to 11.6 million in 2020 contradicting allegations of systematic extermination.[89] Debates intensify over human rights in Altishahr, where Western governments and NGOs allege mass detentions, forced labor, and cultural suppression targeting Uyghurs since 2017, with the U.S. designating these as genocide in 2021 based on leaked documents and satellite imagery of facilities.[92] The 2022 UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) assessment documented serious violations, including arbitrary detention of over one million in "vocational training centers" (per Chinese terminology) potentially amounting to crimes against humanity, particularly in southern Xinjiang's Uyghur-majority areas like Kashgar and Hotan.[90] China rejects these as biased, attributing policies to countering extremism linked to groups like the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), designated terrorist by the UN in 2002, and cites deradicalization successes, poverty reduction from 32% to near zero in Xinjiang by 2020, and voluntary participation in skills programs.[89] Joint statements by 39–43 countries at the UN (2020–2021) urged access for investigators, while Muslim-majority states like Pakistan and Saudi Arabia have endorsed China's narrative, highlighting divisions influenced by geopolitical alliances over empirical consensus.[93][92]References

- https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/Altishahr

.jpg/250px-万国来朝图_(Uqturpan_delegates_in_Peking_in_1761).jpg)

.jpg/1613px-万国来朝图_(Uqturpan_delegates_in_Peking_in_1761).jpg)