Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Behar

View on Wikipedia

Behar, BeHar, Be-har, or B'har (בְּהַר—Hebrew for "on the mount," the fifth word, and the first distinctive word, in the parashah) is the 32nd weekly Torah portion (פָּרָשָׁה, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the ninth in the Book of Leviticus. The parashah tells the laws of the Sabbatical year (שמיטה, Shmita) and limits on debt servitude. The parashah constitutes Leviticus 25:1–26:2. It is the shortest of the weekly Torah portions in the Book of Leviticus (although not the shortest in the Torah). It is made up of 2,817 Hebrew letters, 737 Hebrew words, 57 verses, and 99 lines in a Torah Scroll (סֵפֶר תּוֹרָה, Sefer Torah). [1]

Jews generally read it in May. The lunisolar Hebrew calendar contains up to 55 weeks, the exact number varying between 50 in common years and 54 or 55 in leap years. In leap years (for example, 2024 and 2027), parashah Behar is read separately. In common years (for example, 2025 and 2026), parashah Behar is combined with the next parashah, Bechukotai, to help achieve the needed number of weekly readings.[2]

In years when the first day of Passover falls on a Sabbath (as it does in 2022), Jews in Israel and Reform Jews read the parashah following Passover one week before Conservative and Orthodox Jews in the Diaspora. In such years, Jews in Israel and Reform Jews celebrate Passover for seven days and thus read the next parashah (in 2018, Shemini) on the Sabbath one week after the first day of Passover, while Conservative and Orthodox Jews in the Diaspora celebrate Passover for eight days and read the next parashah (in 2018, Shemini) one week later. In some such years (for example, 2018), the two calendars realign when Conservative and Orthodox Jews in the Diaspora read Behar together with Bechukotai while Jews in Israel and Reform Jews read them separately.[3]

Readings

[edit]In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or עליות, aliyot.[4]

First reading—Leviticus 25:1–13

[edit]In the first reading, on Mount Sinai, God told Moses to tell the Israelites the law of the Sabbatical year for the land.[5] The people could work the fields for six years, but in the seventh year, the land was to have a Sabbath of complete rest during which the people were not to sow their fields, prune their vineyards, or reap the aftergrowth.[6] They could, however, eat whatever the land produced on its own.[7] The people were further to hallow the 50th year, the Jubilee year, and to proclaim release for all with a blast on the horn.[8] Each Israelite was to return to his family and his ancestral land holding.[9]

Second reading—Leviticus 25:14–18

[edit]In the second reading, in selling or buying property, the people were to charge only for the remaining number of crop years until the jubilee, when the land would be returned to its ancestral holder.[10]

Third reading—Leviticus 25:19–24

[edit]In the third reading, God promised to bless the people in the sixth year, so that the land would yield a crop sufficient for three years.[11] God prohibited selling the land beyond reclaim, for God owned the land, and the people were but strangers living with God.[12]

Fourth reading—Leviticus 25:25–28

[edit]In the fourth reading, if one fell into straits and had to sell land, his nearest relative was to redeem what was sold.[13] If one had no one to redeem, but prospered and acquired enough wealth, he could refund the pro rata share of the sales price for the remaining years until the jubilee, and return to his holding.[14]

Fifth reading—Leviticus 25:29–38

[edit]In the fifth reading, if one sold a house in a walled city, one could redeem it for a year, and thereafter the house would pass to the purchaser beyond reclaim and not be released in the jubilee.[15] But houses in villages without encircling walls were treated as open country subject to redemption and release through the jubilee.[16] Levites were to have a permanent right of redemption for houses and property in the cities of the Levites.[17] The unenclosed land about their cities could not be sold.[18] If a kinsman fell into straits and came under one's authority by virtue of his debts, one was to let him live by one's side as a kinsman and not exact from him interest.[19] Israelites were not to lend money to countrymen at interest.[20]

Sixth reading—Leviticus 25:39–46

[edit]In the sixth reading, if the kinsman continued in straits and had to give himself over to a creditor for debt, the creditor was not to subject him to the treatment of a slave, but to treat him as a hired or bound laborer until the jubilee year, at which time he was to be freed to go back to his family and ancestral holding.[21] Israelites were not to rule over such debtor Israelites ruthlessly.[22] Israelites could, however, buy and own as inheritable property slaves from other nations.[23]

Seventh reading—Leviticus 25:47–26:2

[edit]In the seventh reading, if an Israelite fell into straits and came under a resident alien's authority by virtue of his debts, the Israelite debtor was to have the right of redemption.[24] A relative was to redeem him or, if he prospered, he could redeem himself by paying the pro rata share of the sales price for the remaining years until the jubilee.[25] God again told the people they shall not make idols and shall keep God's Sabbaths. [26]

Readings according to the triennial cycle

[edit]Jews who read the Torah according to the triennial cycle of Torah reading read the parashah according to a different schedule.[27]

In inner-biblical interpretation

[edit]The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[28]

Leviticus chapter 25

[edit]Yom Kippur

[edit]Leviticus 25:8–10 refers to the Festival of Yom Kippur. In the Hebrew Bible, Yom Kippur is called:

- the Day of Atonement (יוֹם הַכִּפֻּרִים, Yom HaKippurim)[29] or a Day of Atonement (יוֹם כִּפֻּרִים, Yom Kippurim);[30]

- a Sabbath of solemn rest (שַׁבַּת שַׁבָּתוֹן, Shabbat Shabbaton);[31] and

- a holy convocation (מִקְרָא-קֹדֶשׁ, mikrah kodesh).[32]

Much as Yom Kippur, on the 10th of the month of Tishrei, precedes the Festival of Sukkot, on the 15th of the month of Tishrei, Exodus 12:3–6 speaks of a period starting on the 10th of the month of Nisan preparatory to the Festival of Passover, on the 15th of the month of Nisan.

Leviticus 16:29–34 and 23:26–32 and Numbers 29:7–11 present similar injunctions to observe Yom Kippur. Leviticus 16:29 and 23:27 and Numbers 29:7 set the Holy Day on the tenth day of the seventh month (Tishrei). Leviticus 16:29 and 23:27 and Numbers 29:7 instruct that "you shall afflict your souls." Leviticus 23:32 makes clear that a full day is intended: "you shall afflict your souls; in the ninth day of the month at evening, from evening to evening." And Leviticus 23:29 threatens that whoever "shall not be afflicted in that same day, he shall be cut off from his people." Leviticus 16:29 and 23:28 and Numbers 29:7 command that you "shall do no manner of work." Similarly, Leviticus 16:31 and 23:32 call it a "Sabbath of solemn rest." And in Leviticus 23:30, God threatens that whoever "does any manner of work in that same day, that soul will I destroy from among his people." Leviticus 16:30, 16:32–34, and 23:27–28, and Numbers 29:11 describe the purpose of the day to make atonement for the people. Similarly, Leviticus 16:30 speaks of the purpose "to cleanse you from all your sins," and Leviticus 16:33 speaks of making atonement for the most holy place, the tent of meeting, the altar; and the priests. Leviticus 16:29 instructs that the commandment applies both to "the home-born" and to "the stranger who sojourns among you." Leviticus 16:3–25 and 23:27 and Numbers 29:8–11 command offerings to God. And Leviticus 16:31 and 23:31 institute the observance as "a statute forever."

Leviticus 16:3–28 sets out detailed procedures for the priest's atonement ritual during the time of the Temple.

Leviticus 25:8–10 instructs that after seven Sabbatical years, on the Jubilee year, on the day of atonement, the Israelites were to proclaim liberty throughout the land with the blast of the horn and return all people to their possessions and to their families.

In Isaiah 57:14–58:14, the Haftarah for Yom Kippur morning, God describes "the fast that I have chosen [on] the day for a man to afflict his soul." Isaiah 58:3–5 makes clear that "to afflict the soul" was understood as fasting. But Isaiah 58:6–10 goes on to impress that "to afflict the soul," God also seeks acts of social justice: "to loose the fetters of wickedness, to undo the bands of the yoke," "to let the oppressed go free," "to give your bread to the hungry, and . . . bring the poor that are cast out to your house," and "when you see the naked, that you cover him."

The Duty To Redeem

[edit]Tamara Cohn Eskenazi wrote that Biblical laws required Israelites to act as redeemers for relatives in four situations: (1) redemption of land in Leviticus 25:25–34, (2) redemption of persons from slavery, especially in Leviticus 25:47–50, (3) redemption of objects dedicated to the sanctuary in Leviticus 27:9–28, and (4) avenging the blood of a murdered relative in Numbers 35.[33]

Naboth

[edit]In 1 Kings 21:2, Naboth the Jezreelite refused to sell his vineyard to King Ahab because the land is an inheritance subject to the rule in Leviticus 25:23.[34]

Leviticus chapter 26

[edit]Leviticus 26:1 directs the Israelites not to rear up a pillar (מַצֵּבָה, matzeivah). Exodus 23:24 directed the Israelites to break in pieces the Canaanites' pillars (מַצֵּבֹתֵיהֶם, matzeivoteihem). And Deuteronomy 16:22 prohibits setting up a pillar (מַצֵּבָה, matzeivah), "which the Lord your God hates." But before these commandments were issued, in Genesis 28:18, Jacob took the stone on which he had slept, set it up as a pillar (מַצֵּבָה, matzeivah), and poured oil on the top of it.

In early nonrabbinic interpretation

[edit]The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these early nonrabbinic sources:[35]

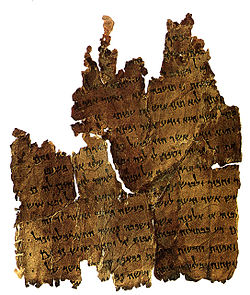

Leviticus chapter 25

[edit]The Damascus Document of the Qumran sectarians prohibited non-cash transactions with Jews who were not members of the sect. Professor Lawrence Schiffman of New York University read this regulation as an attempt to avoid violating prohibitions on charging interest to one's fellow Jew in Exodus 22:25; Leviticus 25:36–37; and Deuteronomy 23:19–20. Apparently, the Qumran sect viewed prevailing methods of conducting business through credit to violate those laws.[36]

In classical rabbinic interpretation

[edit]The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:[37]

Leviticus chapter 25

[edit]Leviticus 25:1–34—a Sabbatical year for the land

[edit]Tractate Sheviit in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Jerusalem Talmud interpreted the laws of the Sabbatical year in Exodus 23:10–11, Leviticus 25:1–34, and Deuteronomy 15:1–18 and 31:10–13.[38]

The Mishnah asked until when a field with trees could be plowed in the sixth year. The House of Shammai said as long as such work would benefit fruit that would ripen in the sixth year. But the House of Hillel said until Shavuot. The Mishnah observed that in reality, the views of two schools approximate each other.[39] The Mishnah taught that one could plow a grain-field in the sixth year until the moisture had dried up in the soil (that it, after Passover, when rains in the Land of Israel cease) or as long as people still plowed in order to plant cucumbers and gourds (which need a great deal of moisture). Rabbi Simeon objected that if that were the rule, then we would place the law in the hands of each person to decide. But the Mishnah concluded that the prescribed period in the case of a grain-field was until Passover, and in the case of a field with trees, until Shavuot.[40] But Rabban Gamaliel and his court ordained that working the land was permitted until the New Year that began the seventh year.[41] Rabbi Joḥanan said that Rabban Gamaliel and his court reached their conclusion on Biblical authority, noting the common use of the term "Sabbath" (שַׁבַּת, Shabbat) in both the description of the weekly Sabbath in Exodus 31:15 and the Sabbath-year in Leviticus 25:4. Thus, just as in the case of the Sabbath Day, work is forbidden on the day itself, but allowed on the day before and the day after, so likewise in the Sabbath Year, tillage is forbidden during the year itself, but allowed in the year before and the year after.[42]

The Mishnah taught that we encourage the work of non-Jews in the Sabbatical year, but not that of Jews. And we inquire after the non-Jews’ wellbeing for the sake of peace.[43]

Rabbi Isaac taught that the words of Psalm 103:20, "mighty in strength that fulfill His word," speak of those who observe the Sabbatical year. Rabbi Isaac said that we often find that a person fulfills a precept for a day, a week, or a month, but it is remarkable to find one who does so for an entire year. Rabbi Isaac asked whether one could find a mightier person than one who sees one's field untilled, see one's vineyard untilled, and yet pays one's taxes and does not complain. And Rabbi Isaac noted that Psalm 103:20 uses the words "that fulfill His word (דְבָר, devar)," and Deuteronomy 15:2 says regarding observance of the Sabbatical year, "And this is the manner (דְּבַר, devar) of the release," and argued that "dabar" means the observance of the Sabbatical year in both places.[44]

The Mishnah taught that the fines for rape, seduction, the husband who falsely accused his bride of not having been a virgin (as in Deuteronomy 22:19), and any judicial court matter are not canceled by the Sabbatical year.[45]

The Mishnah told that when Hillel the Elder observed that the nation withheld from lending to each other and were transgressing Deuteronomy 15:9, "Beware lest there be in your mind a base thought," he instituted the prozbul, a court exemption from the Sabbatical year cancellation of a loan. The Mishnah taught that any loan made with a prozbul is not canceled by the Sabbatical year.[46] The Mishnah recounted that a prozbul would provide: "I turn over to you, so-and-so, judges of such and such a place, that any debt that I may have outstanding, I shall collect it whenever I desire." And the judges or witnesses would sign below.[47]

The Mishnah employed the prohibition of Leviticus 25:4 to imagine how one could with one action violate up to nine separate commandments. One could (1) plow with an ox and a donkey yoked together (in violation of Deuteronomy 22:10) (2 and 3) that are two animals dedicated to the sanctuary, (4) plowing mixed seeds sown in a vineyard (in violation of Deuteronomy 22:9), (5) during a Sabbatical year (in violation of Leviticus 25:4), (6) on a Festival-day (in violation of, for example, Leviticus 23:7), (7) when the plower is a priest (in violation of Leviticus 21:1) and (8) a Nazirite (in violation of Numbers 6:6) plowing in a contaminated place. Chananya ben Chachinai said that the plower also may have been wearing a garment of wool and linen (in violation of Leviticus 19:19 and Deuteronomy 22:11). They said to him that this would not be in the same category as the other violations. He replied that neither is the Nazirite in the same category as the other violations.[48]

The Gemara implied that the sin of Moses in striking the rock at Meribah compared favorably to the sin of David. The Gemara reported that Moses and David were two good leaders of Israel. Moses begged God that his sin be recorded, as it is in Numbers 20:12, 20:23–24, and 27:13–14, and Deuteronomy 32:51. David, however, begged that his sin be blotted out, as Psalm 32:1 says, "Happy is he whose transgression is forgiven, whose sin is pardoned." The Gemara compared the cases of Moses and David to the cases of two women whom the court sentenced to be lashed. One had committed an indecent act, while the other had eaten unripe figs of the seventh year in violation of Leviticus 25:6. The woman who had eaten unripe figs begged the court to make known for what offense she was being flogged, lest people say that she was being punished for the same sin as the other woman. The court thus made known her sin, and the Torah repeatedly records the sin of Moses.[49]

The latter parts of tractate Arakhin in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of the jubilee year in Leviticus 25:8–34.[50]

The Mishnah taught that the jubilee year had the same ritual as Rosh Hashanah for blowing the shofar and for blessings. But Rabbi Judah said that on Rosh Hashanah, the blast was made with a ram's horn shofar, while on jubilee the blast was made with an antelope's (or some say a goat's) horn shofar.[51]

The Mishnah taught that exile resulted from (among other things) transgressing the commandment (in Leviticus 25:3–5 and Exodus 23:10–11) to observe a Sabbatical year for the land.[52] And pestilence resulted from (among other things) violation of the laws governing the produce of the Sabbatical year.[53]

A midrash interpreted the words "it shall be a jubilee unto you" in Leviticus 25:10 to teach that God gave the year of release and the jubilee to the Israelites alone, and not to other nations. And similarly, the midrash interpreted the words "To give you the land of Canaan" in Leviticus 25:38 to teach that God gave the Land of Israel to the Israelites alone.[54]

A baraita taught that they ceased counting Jubilee Years from the time that the tribe of Reuben and the tribe of Gad and half the tribe of Manasseh were exiled, as Leviticus 25:10 states: "And you shall proclaim liberty throughout the land to all its inhabitants; it shall be a Jubilee for you," indicating that the laws of the Jubilee Year apply only when all its inhabitants are in the Land of Israel, and not when some Israelites have been exiled.[55] And a baraita noted that Rabbi Judah HaNasi said that Deuteronomy 15:2 states in the context of the cancellation of debts: "And this is the manner of the abrogation: He shall abrogate." The baraita taught that the verse speaks of two types of abrogation: One is the release of land, and one is the abrogation of monetary debts. Since the two are equated, one can deduce that at a time when they release land, when the Jubilee Year is practiced, they abrogate monetary debts; but at a time when they do not release land, such as the present time, when the Jubilee Year is no longer practiced, they also do not abrogate monetary debts. But the Sages instituted that despite this, the Sabbatical Year still abrogates debt in the present, in remembrance of the Torah-mandated Sabbatical Year. Hillel saw that the people of the nation refrained from lending to each other, so he instituted the prosbol.[56]

Chapter 4 of Tractate Bava Metzia in the Mishnah, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud, and chapter 3 of the tractate in the Tosefta interpreted the law of fraud in Leviticus 25:14.[57] The Mishnah defined as fraud overcharging by one-sixth of the purchase price. And the Mishnah taught that a person defrauded had until that person had time to show the purchase to a merchant or a kinsman to retract the sale.[58] The Mishnah taught that the law of fraud applied to both the buyer and the seller, both the ordinary person and the merchant. Rabbi Judah said that the law of fraud did not apply to the merchant. The Mishnah taught that the one who was defrauded had the upper hand: The person defrauded could demand from the other the money paid or the amount by which that person was defrauded.[59] The Mishnah taught that one who stole something worth even a perutah (the minimum amount of significant value) from a fellow and swore falsely about it had to go after the victim even as far as Media to return it.[60] The Mishnah taught that just as the laws of fraud applied to buying and selling, so too did they apply to the spoken word.[61] The Mishnah taught that one could not ask how much an object costs if one did not wish to buy it.[62]

At a feast, Rabbi served his disciples tender and tough cuts of beef tongue. When his disciples chose the tender over the tough, Rabbi instructed them so to let their tongues be tender to one another. Rabbi taught that this was the meaning of Leviticus 25:14 when Moses admonished: "And if you sell anything ... you shall not wrong one another."[63] Similarly, a midrash concluded that these words of Leviticus 25:14 taught that anyone who wrongs a neighbor with words will be punished according to Scripture.[64]

In a baraita, the Rabbis interpreted the words "you shall not wrong one another" in Leviticus 25:17 to prohibit verbal wrongs, as Leviticus 25:14 had already addressed monetary wrongs. The baraita cited as examples of verbal wrongs: (1) reminding penitents of their former deeds, (2) reminding converts' children of their ancestors' deeds, (3) questioning the propriety of converts' coming to study Torah, (4) speaking to those visited by suffering as Job's companions spoke to him in Job 4:6–7, and (5) directing donkey drivers seeking grain to a person whom one knows has never sold grain. The Gemara said that Scripture uses the words "and you shall fear your God" (as in Leviticus 25:17) concerning cases where intent matters, cases that are known only to the heart. Rabbi Joḥanan said on the authority of Rabbi Simeon ben Yoḥai that verbal wrongs are more heinous than monetary wrongs, because of verbal wrongs it is written (in Leviticus 25:17), "and you shall fear your God," but not of monetary wrongs (in Leviticus 25:14). Rabbi Eleazar said that verbal wrongs affect the victim's person, while monetary wrongs affect only the victim's money. Rabbi Samuel bar Naḥmani said that while restoration is possible in cases of monetary wrongs, it is not in cases of verbal wrongs. And a Tanna taught before Rav Naḥman bar Isaac that one who publicly makes a neighbor blanch from shame is as one who sheds blood. Whereupon Rav Naḥman remarked how he had seen the blood rush from a person's face upon such shaming.[65]

Reading the words of Leviticus 25:17, "And you shall not mistreat each man his colleague (עֲמִיתוֹ, amito)," Rav Ḥinnana, son of Rav Idi, taught that the word עֲמִיתוֹ, amito, is interpreted as a contraction of עִם אִתּוֹ, im ito, meaning: "One who is with him. " Thus one must not mistreat one who is with one in observance of Torah and commandments.[66]

The Gemara taught that the Torah three times prohibits verbally mistreating a convert—in Exodus 22:20, "And you shall neither mistreat a convert"; in Leviticus 19:33, "And when a convert lives in your land, you shall not mistreat him"; and in Leviticus 25:17, "And you shall not mistreat, each man his colleague." And the Torah similarly three times prohibits oppressing the convert—in Exodus 22:20, "And you shall neither mistreat a convert, nor oppress him"; in Exodus 23:9, "And you shall not oppress a convert"; and in Exodus 22:24, "And you shall not be to him like a creditor." Reading Exodus 22:20, "And you shall not mistreat a convert nor oppress him, because you were strangers in the land of Egypt," a baraita reported that Rabbi Nathan taught that one should not mention in another a defect that one has oneself. Thus, since the Jewish people were themselves strangers, they should not demean a convert because he is a stranger in their midst. And this explains the adage that one who has a person hanged in the family does not say to another member of the household: Hang a fish for me, as the mention of hanging is demeaning for that family.[66]

Expanding on Leviticus 25:23, in which God says that "the land is Mine," Rabbi Elazar of Bartotha said that you and all that is yours is Gods; and thus 1 Chronicles 29:14 says with regards to David: "for everything comes from You, and from Your own hand have we given you."[67]

Rabbi Phinehas in the name of Rabbi Reuben interpreted the words "If your brother grows poor ... then shall his kinsman ... redeem" in Leviticus 25:25 to exhort Israel to acts of charity. Rabbi Phinehas taught that God will reward with life anyone who gives a coin to a poor person, for the donor could be giving not just a coin, but life. Rabbi Phinehas explained that if a loaf costs ten coins, and a poor person has but nine, then the gift of a single coin allows the poor person to buy the loaf, eat, and become refreshed. Thus, Rabbi Phinehas taught, when illness strikes the donor, and the donor's soul presses to leave the donor's body, God will return the gift of life.[68] Similarly, Rav Naḥman taught that Leviticus 25:25 exhorts Israel to acts of charity, because fortune revolves like a wheel in the world, sometimes leaving one poor and sometimes well off.[69] And similarly, Rabbi Tanḥum son of Rabbi Ḥiyya taught that Leviticus 25:25 exhorts Israel to acts of charity, because God made the poor as well as the rich, so that they might benefit each other; the rich one benefiting the poor one with charity, and the poor one benefiting the rich one by affording the rich one the opportunity to do good. Bearing this in mind, when Rabbi Tanhum's mother went to buy him a pound of meat, she would buy him two pounds, one for him and one for the poor.[70]

The Gemara employed Leviticus 25:29 to deduce that the term יָמִים, yamim, (literally "days") sometimes means "a year," and Rab Hisda thus interpreted the word יָמִים, yamim, in Genesis 24:55 to mean "a year." Genesis 24:55 says, "And her brother and her mother said: ‘Let the maiden abide with us יָמִים, yamim, at the least ten." The Gemara reasoned that if יָמִים, yamim, in Genesis 24:55 means "days" and thus to imply "two days" (as the plural implies more than one), then Genesis 24:55 would report Rebekah's brother and mother suggesting that she stay first two days, and then when Eliezer said that that was too long, nonsensically suggesting ten days. The Gemara thus deduced that יָמִים, yamim, must mean "a year" in Genesis 24:55, as Leviticus 25:29 implies when it says, "if a man sells a house in a walled city, then he may redeem it within a whole year after it is sold; for a full year (יָמִים, yamim) shall he have the right of redemption." Thus Genesis 24:55 might mean, "Let the maiden abide with us a year, or at the least ten months." The Gemara then suggested that יָמִים, yamim, might mean "a month," as Numbers 11:20 suggests when it uses the phrase "a month of days (יָמִים, yamim)." The Gemara concluded, however, that יָמִים, yamim, means "a month" only when the term "month" is specifically mentioned, but otherwise means either "days" (at least two) or "a year."[71]

Leviticus 25:35–55—limits on debt servitude

[edit]The Sifra read the words of Leviticus 25:35, "You shall support him," to teach that one should not let one's brother who grows poor to fall down. The Sifra compared financial strains to a load on a donkey. While the donkey is still standing in place, a single person can take hold of it and lead it. But if the donkey falls to the ground, five people cannot pick it up again.[72]

In the words, "Take no interest or increase, but fear your God," in Leviticus 25:36, "interest" (נֶשֶׁךְ, neshech) literally means "bite." A midrash played on this meaning, teaching not to take interest from the poor person, not to bite the poor person as the serpent—cunning to do evil—bit Adam. The midrash taught that one who exacts interest from an Israelite thus has no fear of God.[73]

Rav Naḥman bar Isaac (explaining the position of Rabbi Eleazar) interpreted the words "that your brother may live with you" in Leviticus 25:36 to teach that one who has exacted interest should return it to the borrower, so that the borrower could survive economically.[74]

A baraita considered the case where two people were traveling on a journey, and one had a container of water; if both drank, they would both die, but if only one drank, then that one might reach civilization and survive. Ben Patura taught that it is better that both should drink and die, rather than that only one should drink and see the other die. But Rabbi Akiva interpreted the words "that your brother may live with you" in Leviticus 25:36 to teach that concern for one's own life takes precedence over concern for another's.[75]

Part of chapter 1 of Tractate Kiddushin in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of the Hebrew servant in Exodus 21:2–11 and 21:26–27; Leviticus 25:39–55; and Deuteronomy 15:12–18.[76]

Abaye said that because the law (in Leviticus 25:39–43 and elsewhere) required the master to treat a Hebrew slave well—and as an equal in food, drink, and sleeping accommodations—it was said that buying a Hebrew slave was like buying a master.[77] The Rabbis taught in a baraita that the words of Deuteronomy 15:16 regarding the Hebrew servant, "he fares well with you," indicate that the Hebrew servant had to be "with"—that is, equal to—the master in food and drink. Thus, the master could not eat white bread and have the servant eat black bread. The master could not drink old wine and have the servant drink new wine. The master could not sleep on a feather bed and have the servant sleep on straw. Hence, they said that buying a Hebrew servant was like buying a master. Similarly, Rabbi Simeon deduced from the words of Leviticus 25:41, "Then he shall go out from you, he and his children with him," that the master was liable to provide for the servant's children until the servant went out. And Rabbi Simeon deduced from the words of Exodus 21:3, "If he is married, then his wife shall go out with him," that the master was responsible to provide for the servant's wife, as well.[78]

The Sifra read Leviticus 25:42, "For they are My servants," to imply that God's deed of servitude came first, and therefore, Israelites may serve others only as God permits. And the Sifra read Leviticus 25:42, "whom I took out of the land of Egypt" to imply that God took the Israelites out on the condition that they not be sold as slaves are sold.[79]

Rabbi Joḥanan read Leviticus 25:42, "They shall not be sold as bondsmen," to prohibit abduction. The Gemara asked where Scripture formally prohibited abduction (as Deuteronomy 22:7 and Exodus 21:16 state only the punishment). Rabbi Josiah said that Exodus 20:13, "You shalt not steal," did so. Rabbi Joḥanan said that Leviticus 25:42, “They shall not be sold as bondsmen,” did so. The Gemara harmonized the two teachings by interpreting Rabbi Josiah to state the prohibition for stealing (including abduction) and Rabbi Joḥanan to state the prohibition for selling the kidnapped person.[80]

Rabbi Levi interpreted Leviticus 25:55 to teach that God claimed Israel as God's own possession when God said, "To Me the children of Israel are servants."[81]

Reading Exodus 21:6, regarding the Hebrew servant who chose not to go free and whose master brought him to the doorpost and bore his ear through with an awl, Rabban Joḥanan ben Zakkai explained that God singled out the ear from all the parts of the body because the servant had heard God's Voice on Mount Sinai proclaiming in Leviticus 25:55, "For to me the children of Israel are servants, they are my servants," and not servants of servants, and yet the servant acquired a master for himself when he might have been free. And Rabbi Simeon bar Rabbi explained that God singled out the doorpost from all other parts of the house because the doorpost was witness in Egypt when God passed over the lintel and the doorposts (as reported in Exodus 12) and proclaimed (in the words of Leviticus 25:55), "For to me the children of Israel are servants, they are my servants," and not servants of servants, and so God brought them forth from bondage to freedom, yet this servant acquired a master for himself.[82]

In medieval Jewish interpretation

[edit]The parashah is discussed in these medieval Jewish sources:[83]

Leviticus chapter 25

[edit]Baḥya ibn Paquda taught that those who are alone, without family or relatives, should let their companionship be with God during their time of loneliness, and trust in God during their period of being a stranger. Baḥya counseled that they should contemplate that the soul is also a stranger in this world, and that all people are like strangers here, as Leviticus 25:23 says, "because you are strangers and temporary residents with Me." Baḥya encouraged them to reflect in their hearts that all those who have relatives here, in a short time, will be left solitary strangers.[84]

Maimonides taught that the laws of the Sabbatical year and the Jubilee imply sympathy with others and promote the well-being of humanity, as about these precepts Exodus 23:11 states, "That the poor of your people may eat," and the land will also increase its produce and improve when it remains fallow for some time. Others of these laws prescribe kindness to servants and the poor, by renouncing claims to debts in the year of release and relieving servants of their bondage in the Sabbatical year. Some of these precepts secure for people a permanent source of economic well-being by providing that the land should remain the permanent property of its owners and could not be sold, as Leviticus 25:23 says, "And the land shall not be sold forever." In this way, people's property remained intact for them and their heirs, and they could consume only the land's produce.[85]

In modern interpretation

[edit]The parashah is discussed in these modern sources:

Leviticus chapter 25

[edit]In 1877, August Klostermann observed the singularity of Leviticus 17–26 as a collection of laws and designated it the "Holiness Code."[86]

Jay Sklar identified the following chiastic structure in Leviticus 25–27:[87]

- A—laws about redemption (Leviticus 25)

- B—blessings for covenant obedience and curses for covenant disobedience (Leviticus 26)

- A'—laws about redemption (Leviticus 27)

William Dever noted that Leviticus 25:29–34 recognizes three land-use distinctions: (1) walled cities (עִיר חוֹמָה, ir chomot); (2) unwalled villages (חֲצֵרִים, chazeirim, specially said to be unwalled); and (3) land surrounding such a city (שְׂדֵה מִגְרַשׁ, sedeih migrash) and the countryside (שְׂדֵה הָאָרֶץ, sedeih ha-aretz, "fields of the land").[88]

Commandments

[edit]According to Sefer ha-Chinuch, there are 7 positive and 17 negative commandments in the parashah:[89]

- Not to work the land during the seventh year[90]

- Not to work with trees to produce fruit during that year[90]

- Not to reap crops that grow wild that year in the normal manner[91]

- Not to gather grapes which grow wild that year in the normal way[91]

- The Sanhedrin must count seven groups of seven years.[92]

- To blow the shofar on the tenth of Tishrei to free the slaves[93]

- The Sanhedrin must sanctify the 50th year.[9]

- Not to work the soil during the 50th year[94]

- Not to reap in the normal manner that which grows wild in the fiftieth year[94]

- Not to pick grapes which grew wild in the normal manner in the fiftieth year[94]

- To buy and sell according to Torah law[95]

- Not to overcharge or underpay for an article[95]

- Not to insult or harm anybody with words[96]

- Not to sell the land in Israel indefinitely[97]

- To carry out the laws of sold family properties[98]

- To carry out the laws of houses in walled cities[99]

- Not to sell the fields but they shall remain the Levites' before and after the Jubilee year[18]

- Not to lend with interest[20]

- Not to have a Hebrew servant do menial slave labor[100]

- Not to sell a Hebrew servant as a slave is sold[101]

- Not to work a Hebrew servant oppressively[22]

- Canaanite slaves must be kept forever[102]

- Not to allow a non-Jew to work a Hebrew servant oppressively[103]

- Not to bow down on smooth stone[104]

Haftarah

[edit]The haftarah for the parashah is Jeremiah 32:6–27.

When parashah Behar is combined with parashah Behukotai, the haftarah is the haftarah for Behukotai, Jeremiah 16:19–17:14.

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Torah Stats for VaYikra". Akhlah Inc. Retrieved October 11, 2023.

- ^ "Parashat Behar". Hebcal. Retrieved May 4, 2015.

- ^ See Hebcal Jewish Calendar and compare results for Israel and the Diaspora.

- ^ See, e.g., Menachem Davis, editor, The Schottenstein Edition Interlinear Chumash: Vayikra/Leviticus (Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2008), pages 174–86.

- ^ Leviticus 25:1–2.

- ^ Leviticus 25:3–5.

- ^ Leviticus 25:6–7.

- ^ Leviticus 25:8–10.

- ^ a b Leviticus 25:10.

- ^ Leviticus 25:14–17.

- ^ Leviticus 25:20–22.

- ^ Leviticus 25:23.

- ^ Leviticus 25:25.

- ^ Leviticus 25:26–27.

- ^ Leviticus 25:29–30.

- ^ Leviticus 25:31.

- ^ Leviticus 25:32–33.

- ^ a b Leviticus 25:34.

- ^ Leviticus 25:35–36.

- ^ a b Leviticus 25:37.

- ^ Leviticus 25:39–42.

- ^ a b Leviticus 25:43.

- ^ Leviticus 25:44–46.

- ^ Leviticus 25:47–48.

- ^ Leviticus 25:48–52.

- ^ Leviticus 26:1–2.

- ^ See, e.g., Richard Eisenberg, "A Complete Triennial Cycle for Reading the Torah," Proceedings of the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement: 1986–1990 (New York: The Rabbinical Assembly, 2001), pages 383–418.

- ^ For more on inner-Biblical interpretation, see, e.g., Benjamin D. Sommer, "Inner-biblical Interpretation," in Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, editors, The Jewish Study Bible, 2nd edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), pages 1835–41.

- ^ Leviticus 23:27 and 25:9.

- ^ Leviticus 23:28.

- ^ Leviticus 16:31 and 23:32.

- ^ Leviticus 23:27 and Numbers 29:7.

- ^ Tamara Cohn Eskenazi and Tikva Frymer-Kensky, The JPS Bible Commentary: Ruth (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2011), page liv.

- ^ Robert Jamieson, Andrew R. Fausset, and David Brown, A Commentary on the Old and New Testaments (Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 1997), volume 1, page 362 (commentary on 1 Kings 21).

- ^ For more on early nonrabbinic interpretation, see, e.g., Esther Eshel, "Early Nonrabbinic Interpretation," in Adele Berlin and Marc Brettler, editors, Jewish Study Bible, 2nd edition, pages 1841–59.

- ^ Lawrence H. Schiffman, Reclaiming the Dead Sea Scrolls: The History of Judaism, the Background of Christianity, the Lost Library of Qumran (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1994), page 107 (citing Zadokite Fragments 13:14–16 = Da 18 II 1–4).

- ^ For more on classical rabbinic interpretation, see, e.g., Yaakov Elman, "Classical Rabbinic Interpretation," in Adele Berlin and Marc Brettler, editors, Jewish Study Bible, 2nd edition, pages 1859–78.

- ^ Mishnah Sheviit 1:1–10:9; Tosefta Sheviit 1:1–8:11; Jerusalem Talmud Sheviit 1a–87b.

- ^ Mishnah Sheviit 1:1.

- ^ Mishnah Sheviit 2:1.

- ^ Tosefta Sheviit 1:1.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Moed Katan 4a.

- ^ Mishnah Sheviit 5:9.

- ^ Leviticus Rabbah 1:1.

- ^ Mishnah Sheviit 10:2.

- ^ Mishnah Sheviit 10:3.

- ^ Mishnah Sheviit 10:4.

- ^ Mishnah Makkot 3:9; Babylonian Talmud Makkot 21b.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Yoma 86b.

- ^ Mishnah Arakhin 7:1–9:8; Tosefta Arakhin 5:1–19; Babylonian Talmud Arakhin 24a–34a.

- ^ Mishnah Rosh Hashanah 3:5; Babylonian Talmud Rosh Hashanah 26b.

- ^ Mishnah Avot 5:9.

- ^ Mishnah Avot 5:8.

- ^ Exodus Rabbah 15:23.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Arakhin 32b.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Gittin 36a–b.

- ^ Mishnah Bava Metzia 4:1–12; Tosefta Bava Metzia 3:13–29; Jerusalem Talmud Bava Metzia 12a–16b; Babylonian Talmud Bava Metzia 44a–60b.

- ^ Mishnah Bava Metzia 4:3; Tosefta Bava Metzia 3:15; Jerusalem Talmud Bava Metzia 14a; Babylonian Talmud Bava Metzia 49b.

- ^ Mishnah Bava Metzia 4:4; Jerusalem Talmud Bava Metzia 14b; Babylonian Talmud Bava Metzia 51a.

- ^ Mishnah Bava Metzia 4:7; Jerusalem Talmud Bava Metzia 15b; Babylonian Talmud Bava Metzia 55a.

- ^ Mishnah Bava Metzia 4:10; Tosefta Bava Metzia 3:25; Jerusalem Talmud Bava Metzia 16a; Babylonian Talmud Bava Metzia 58b.

- ^ Mishnah Bava Metzia 4:10; Jerusalem Talmud Bava Metzia 16a; Babylonian Talmud Bava Metzia 58b.

- ^ Leviticus Rabbah 33:1.

- ^ Leviticus Rabbah 33:5.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Bava Metzia 58b.

- ^ a b Babylonian Talmud Bava Metzia 59a.

- ^ Mishnah Avot 3:7.

- ^ Leviticus Rabbah 34:2.

- ^ Leviticus Rabbah 34:3.

- ^ Leviticus Rabbah 34:5.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Ketubot 57b.

- ^ Sifra Behar, Parashah 5 (275:5:1).

- ^ Exodus Rabbah 31:13.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Bava Metzia 61b–62a.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Bava Metzia 62a.

- ^ Mishnah Kiddushin 1:2; Tosefta Kiddushin 1:5–6; Jerusalem Talmud Kiddushin 5b–11b (1:2); Babylonian Talmud Kiddushin 14b–22b.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Kiddushin 20a.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Kiddushin 22a.

- ^ Sifra Parashat Behar, Parashah 6 (257:1:1–2).

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Sanhedrin 86a.

- ^ Exodus Rabbah 30:1; see also Exodus Rabbah 33:5.

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Kiddushin 22b.

- ^ For more on medieval Jewish interpretation, see, e.g., Barry D. Walfish, "Medieval Jewish Interpretation," in Adele Berlin and Marc Brettler, editors, Jewish Study Bible, 2nd Edition', pages 1891–915.

- ^ Baḥya ibn Paquda, Chovot HaLevavot (Duties of the Heart), section 4, chapter 4.

- ^ Maimonides, The Guide for the Perplexed, part 3, chapter 39.

- ^ Menahem Haran, "Holiness Code," in Encyclopaedia Judaica (Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House, 1972), column 820.

- ^ Jay Sklar, Leviticus (Downers Grove, Illinois: Inter-Varsity Press, 2014), page 297.

- ^ William G. Dever, The Lives of Ordinary People in Ancient Israel: When Archaeology and the Bible Intersect (Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2012), pages 133–34.

- ^ Charles Wengrov, translator, Sefer HaḤinnuch: The Book of [Mitzvah] Education (Jerusalem: Feldheim Publishers, 1984), volume 3, pages 363–461.

- ^ a b Leviticus 25:4.

- ^ a b Leviticus 25:5.

- ^ Leviticus 25:8.

- ^ Leviticus 25:9.

- ^ a b c Leviticus 25:11.

- ^ a b Leviticus 25:14.

- ^ Leviticus 25:17.

- ^ Leviticus 25:23.

- ^ Leviticus 25:24.

- ^ Leviticus 25:29.

- ^ Leviticus 25:39.

- ^ Leviticus 25:42.

- ^ Leviticus 25:46.

- ^ Leviticus 25:53.

- ^ Leviticus 26:1.

Further reading

[edit]The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these sources:

Ancient

[edit]

- Code of Hammurabi § 117. Babylonia, Circa 1780 BCE. In e.g. Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament. Edited by James B. Pritchard, pages 163, 170–71. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969. (3-year limit on debt servitude for wife or child).

- Julius Lewy. "The Biblical Institution of deror in the Light of Akkadian Documents." Eretz-Israel, volume 5 (1958): pages 21–31.

Biblical

[edit]- Exodus 21:1–11 (slavery); 23:10–11 (Sabbatical year)

- Leviticus 26:34–35 (Sabbatical year).

- Deuteronomy 15:1–6 (Sabbatical year); 15:12–18 (Sabbatical year); 31:10–13 (Sabbatical year).

- 2 Kings 4:1–7 (slavery).

- Isaiah 61:1–2 (proclaim release).

- Jeremiah 32:6–15 (next of kin redeemer); 34:6–27 (releasing Hebrew slaves).

- Ezekiel 7:12–13, 19 (economic equalization); 46:17 (year of release).

- Amos 2:6 (slavery).

- Psalms 4:9 (dwell in safety); 15:5 (lending); 37:26 (lending); 39:12 (God chastens man for iniquity); 119:19 (sojourner on earth).

- Nehemiah 5:1–13 (slavery).

- 2 Chronicles 36:20–21 (Sabbatical year).

Early nonrabbinic

[edit]

- Jubilees chs. 1–50 Land of Israel, 2nd Century BCE.

- Quran 2:275; 3:130. Arabia, 7th century. (Islam's parallel prohibition of interest, or riba).

Classical rabbinic

[edit]- Mishnah: Sheviit 1:1–10:9; Rosh Hashanah 3:5; Ketubot 9:9; Nedarim 9:4; Kiddushin 1:2–3; Bava Metzia 5:1–11; Sanhedrin 3:4; Makkot 3:9; Avot 5:8–9; Bekhorot 9:10; Arakhin 7:1–9:8. Land of Israel, circa 200 CE. In, e.g., The Mishnah: A New Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, pages 68–93, 304, 424, 487, 544, 588, 618, 687, 807, 821–24. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988.

- Tosefta: Sheviit 1:1–8:11; Maaser Sheni 2:15; Sotah 5:11; Kiddushin 1:5–6; Bava Kamma 7:5; Bava Metzia 3:25; 4:2; Avodah Zarah 4:5; Arakhin 4:9; 5:1–19. Land of Israel, circa 250 CE. In, e.g., The Tosefta: Translated from the Hebrew, with a New Introduction. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 1, pages 203–49, 307, 853, 926–27; volume 2, pages 987, 1042, 1044, 1275, 1507, 1512–17. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2002.

- Sifra Behar (245:1–259:2). Land of Israel, 4th Century CE. In, e.g., Sifra: An Analytical Translation. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 3, pages 291–344. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1988.

- Jerusalem Talmud: Peah 67a; Demai 24a, 48b; Sheviit 1a–87b; Maasrot 31b, 42b; Orlah 8a; Shabbat 56a–57a; Pesachim 34a; Rosh Hashanah 7b, 15b, 20b, 22b; Megillah 2b; Ketubot 24b, 25b; Nedarim 32a; Gittin 20a, 23b–24a; Kiddushin 1b, 6a, 7a–b, 10b–11b; Bava Metzia 14a, 17a, 23a, 24a; Sanhedrin 4b, 40a, 41a–b. Tiberias, Land of Israel, circa 400 CE. In, e.g., Talmud Yerushalmi. Edited by Chaim Malinowitz, Yisroel Simcha Schorr, and Mordechai Marcus, volumes 3–4, 6a–b, 9, 12, 14, 18, 24, 26, 31, 33, 38, 40, 42, 44–45. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2006–2018. And reprinted in, e.g., The Jerusalem Talmud: A Translation and Commentary. Edited by Jacob Neusner and translated by Jacob Neusner, Tzvee Zahavy, B. Barry Levy, and Edward Goldman. Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, 2009.

- Mekhilta According to Rabbi Ishmael 1:2. Land of Israel, late 4th Century. In, e.g., Mekhilta According to Rabbi Ishmael. Translated by Jacob Neusner, volume 1, page 6. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1988.

- Leviticus Rabbah 1:1; 2:2; 7:6; 29:11; 33:1–34:16. Land of Israel, 5th Century. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbah: Leviticus. Translated by Harry Freedman and Maurice Simon, volume 4, pages 2, 21, 98, 378, 418–45. London: Soncino Press, 1939.

- Babylonian Talmud: Berakhot 12b, 36b, 47b; Shabbat 33a, 96b, 131b; Pesachim 51b, 52b; Yoma 65b, 86b; Sukkah 3a, 39a, 40a–b; Beitzah 34b, 37b; Rosh Hashanah 2a, 6b, 8b–9b, 13a, 24a, 26a, 27b, 30a, 33b–34a; Taanit 6b, 19b; Megillah 3b, 5b, 10b, 22b, 23b; Moed Katan 2a–4a, 13a; Chagigah 3b; Yevamot 46a, 47a, 78b, 83a; Ketubot 43a–b, 57b, 84a, 110b; Nedarim 42a, 58b, 61a; Nazir 5a, 61b; Sotah 3b; Gittin 25a, 36a–39a, 44b, 47a, 48b, 65a, 74b; Kiddushin 2b, 8a, 9a, 14b–17b, 20a–22b, 26a, 33b, 38b, 40b, 53a, 58a, 67b; Bava Kamma 28a, 62b, 69a–b, 82b, 87a, 101a–02a, 103a, 112a, 113a–b, 116b, 117b; Bava Metzia 10a, 12a, 30b, 47b, 51a, 56b, 57b, 58b–59b, 60b–61b, 65a, 71a, 73b, 75b, 79a, 82a, 88b, 106a, 109a, 114a; Bava Batra 10a, 80b, 91b, 102b, 110b, 112a, 137a, 139a; Sanhedrin 10b, 12a, 15a, 24b, 26a, 39a, 65b, 86a, 101b, 106b; Makkot 3b, 8a–b, 11b–12a, 13a, 21b; Shevuot 4b, 16a, 45a; Avodah Zarah 9b, 20a, 50b, 54b, 62a; Menachot 84a; Chullin 6a, 114b, 120b; Bekhorot 12b–13b, 51a, 52b; Arakhin 14b, 15b, 18b, 24a–34a; Temurah 6b, 27a; Niddah 8b, 47a–48a, 51b. Sasanian Empire, 6th Century. In, e.g., Talmud Bavli. Edited by Yisroel Simcha Schorr, Chaim Malinowitz, and Mordechai Marcus, 72 volumes. Brooklyn: Mesorah Pubs., 2006.

- Midrash Tanhuma, Behar. 6th–7th Century. In, e.g., Metsudah Midrash Tanchuma: Vayikra. Translated and annotated by Avraham Davis, edited by Yaakov Y.H. Pupko, 5:502–30. Monsey, N.Y.: Eastern Book Press, 2006.

Medieval

[edit]- Rashi. Commentary. Leviticus 25–26. Troyes, France, late 11th Century. In, e.g., Rashi. The Torah: With Rashi's Commentary Translated, Annotated, and Elucidated. Translated and annotated by Yisrael Isser Zvi Herczeg, volume 3, pages 317–46. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1994.

- Rashbam. Commentary on the Torah. Troyes, early 12th century. In, e.g., Rashbam's Commentary on Leviticus and Numbers: An Annotated Translation. Edited and translated by Martin I. Lockshin, pages 131–37. Providence: Brown Judaic Studies, 2001.

- Judah Halevi. Kuzari. 2:18. Toledo, Spain, 1130–1140. In, e.g., Jehuda Halevi. Kuzari: An Argument for the Faith of Israel. Introduction by Henry Slonimsky, page 93. New York: Schocken, 1964.

- Abraham ibn Ezra. Commentary on the Torah. Mid-12th century. In, e.g., Ibn Ezra's Commentary on the Pentateuch: Leviticus (Va-yikra). Translated and annotated by H. Norman Strickman and Arthur M. Silver, volume 3, pages 239–61. New York: Menorah Publishing Company, 2004.

- Maimonides. Mishneh Torah: Hilchot Shemita V'Yovel (Laws of the Sabbatical and Jubilee Years). Egypt. Circa 1170–1180. In, e.g., Mishneh Torah: Sefer Zeraim: The Book of Agricultural Ordinances. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, pages 716–837. New York: Moznaim Publishing, 2005.

- Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed, part 1, chapter 12; part 3, chapters 38, 45. Cairo, Egypt, 1190. In, e.g., Moses Maimonides. The Guide for the Perplexed. Translated by Michael Friedländer, pages 24, 340, 357. New York: Dover Publications, 1956.

- Hezekiah ben Manoah. Hizkuni. France, circa 1240. In, e.g., Chizkiyahu ben Manoach. Chizkuni: Torah Commentary. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 3, pages 819–29. Jerusalem: Ktav Publishers, 2013.

- Naḥmanides. Commentary on the Torah. Jerusalem, circa 1270. In, e.g., Ramban (Nachmanides): Commentary on the Torah. Translated by Charles B. Chavel, volume 3, pages 409–54. New York: Shilo Publishing House, 1974.

- Zohar, part 3, pages 107b–111a. Spain, late 13th Century. In, e.g., The Zohar. Translated by Harry Sperling and Maurice Simon. 5 volumes. London: Soncino Press, 1934.

- Bahya ben Asher. Commentary on the Torah. Spain, early 14th century. In, e.g., Midrash Rabbeinu Bachya: Torah Commentary by Rabbi Bachya ben Asher. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 5, pages 1821–45. Jerusalem: Lambda Publishers, 2003.

- Jacob ben Asher (Baal Ha-Turim). Rimze Ba'al ha-Turim. Early 14th century. In, e.g., Baal Haturim Chumash: Vayikra/Leviticus. Translated by Eliyahu Touger, edited, elucidated, and annotated by Avie Gold, volume 3, pages 1271–93. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 2000.

- Jacob ben Asher. Perush Al ha-Torah. Early 14th century. In, e.g., Yaakov ben Asher. Tur on the Torah. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 3, pages 969–85. Jerusalem: Lambda Publishers, 2005.

- Isaac ben Moses Arama. Akedat Yizhak (The Binding of Isaac). Late 15th century. In, e.g., Yitzchak Arama. Akeydat Yitzchak: Commentary of Rabbi Yitzchak Arama on the Torah. Translated and condensed by Eliyahu Munk, volume 2, pages 669–73. New York, Lambda Publishers, 2001.

Modern

[edit]- Isaac Abravanel. Commentary on the Torah. Italy, between 1492 and 1509. In, e.g., Abarbanel: Selected Commentaries on the Torah: Volume 3: Vayikra/Leviticus. Translated and annotated by Israel Lazar, pages 230–52. Brooklyn: CreateSpace, 2015.

- Obadiah ben Jacob Sforno. Commentary on the Torah. Venice, 1567. In, e.g., Sforno: Commentary on the Torah. Translation and explanatory notes by Raphael Pelcovitz, pages 614–25. Brooklyn: Mesorah Publications, 1997.

- Moshe Alshich. Commentary on the Torah. Safed, circa 1593. In, e.g., Moshe Alshich. Midrash of Rabbi Moshe Alshich on the Torah. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 2, pages 751–71. New York, Lambda Publishers, 2000.

- Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan, 3:40; Review & Conclusion. England, 1651. Reprint edited by C. B. Macpherson, pages 503–04, 723. Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Classics, 1982.

- Shabbethai Bass. Sifsei Chachamim. Amsterdam, 1680. In, e.g., Sefer Vayikro: From the Five Books of the Torah: Chumash: Targum Okelos: Rashi: Sifsei Chachamim: Yalkut: Haftaros, translated by Avrohom Y. Davis, pages 483–529. Lakewood Township, New Jersey: Metsudah Publications, 2012.

- Chaim ibn Attar. Ohr ha-Chaim. Venice, 1742. In Chayim ben Attar. Or Hachayim: Commentary on the Torah. Translated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 3, pages 1271–91. Brooklyn: Lambda Publishers, 1999.

- Nachman of Breslov. Teachings. Bratslav, Ukraine, before 1811. In Rebbe Nachman's Torah: Breslov Insights into the Weekly Torah Reading: Exodus-Leviticus. Compiled by Chaim Kramer, edited by Y. Hall, pages 419–25. Jerusalem: Breslov Research Institute, 2011.

- Samuel David Luzzatto (Shadal). Commentary on the Torah. Padua, 1871. In, e.g., Samuel David Luzzatto. Torah Commentary. Translated and annotated by Eliyahu Munk, volume 3, pages 984–93. New York: Lambda Publishers, 2012.

- Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter. Sefat Emet. Góra Kalwaria (Ger), Poland, before 1906. Excerpted in The Language of Truth: The Torah Commentary of Sefat Emet. Translated and interpreted by Arthur Green, pages 201–07. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 1998. Reprinted 2012.

- Hermann Cohen. Religion of Reason: Out of the Sources of Judaism. Translated with an introduction by Simon Kaplan; introductory essays by Leo Strauss, pages 126, 152–53. New York: Ungar, 1972. Reprinted Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1995. Originally published as Religion der Vernunft aus den Quellen des Judentums. Leipzig: Gustav Fock, 1919.

- H. G. Wells. “Serfs, Slaves, Social Classes and Free Individuals.” In The Outline of History: Being a Plain History of Life and Mankind, pages 254–59. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1920. Revised edition Doubleday and Company, 1971.

- Alexander Alan Steinbach. Sabbath Queen: Fifty-four Bible Talks to the Young Based on Each Portion of the Pentateuch, pages 100–03. New York: Behrman's Jewish Book House, 1936.

- Thomas Mann. Joseph and His Brothers. Translated by John E. Woods, page 356. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005. Originally published as Joseph und seine Brüder. Stockholm: Bermann-Fischer Verlag, 1943. (sacred stone).

- Isaac Mendelsohn. "Slavery in the Ancient Near East." Biblical Archaeologist, volume 9 (1946): pages 74–88.

- Isaac Mendelsohn. Slavery in the Ancient Near East. New York: Oxford University Press, 1949.

- Electric Prunes. "Kol Nidre." In Release of an Oath. Reprise Records, 1968. (track based on the Yom Kippur Kol Nidre prayer).

- Gordon J. Wenham. The Book of Leviticus, pages 313–29. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1979.

- Pinchas H. Peli. Torah Today: A Renewed Encounter with Scripture, pages 147–50. Washington, D.C.: B'nai B'rith Books, 1987.

- Ben Zion Bergman. "A Question of Great Interest: May a Synagogue Issue Interest-Bearing Bonds?" New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 1988. YD 167:1.1988a. In Responsa: 1980–1990: The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement. Edited by David J. Fine, pages 319–23. New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2005.

- Avram Israel Reisner. "Dissent: A Matter of Great Interest" New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 1988. YD 167:1.1988b. In Responsa: 1980–1990: The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement. Edited by David J. Fine, pages 324–28. New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2005.

- Elliot N. Dorff. "A Jewish Approach to End-Stage Medical Care." New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 1990. YD 339:1.1990b. In Responsa: 1980–1990: The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement. Edited by David J. Fine, pages 519, 531–32, 564. New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2005. (implications of God's ownership of the universe on the duty to maintain life and health).

- Harvey J. Fields. A Torah Commentary for Our Times: Volume II: Exodus and Leviticus, pages 150–61. New York: UAHC Press, 1991.

- John E. Hartley. Leviticus, pages 415–48. Dallas: Word Books, 1992.

- Jacob Milgrom. "Sweet Land and Liberty: Whether real or utopian, the laws in Leviticus seem to be a more sensitive safeguard against pauperization than we, here and now, have devised." Bible Review, volume 9 (number 4) (August 1993).

- Walter C. Kaiser Jr., " The Book of Leviticus," in The New Interpreter's Bible, volume 1, pages 1166–79. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1994.

- Judith S. Antonelli. "Mother Nature." In In the Image of God: A Feminist Commentary on the Torah, pages 322–28. Northvale, New Jersey: Jason Aronson, 1995.

- Elliot N. Dorff. "Family Violence." New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 1995. HM 424.1995. In Responsa: 1991–2000: The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement. Edited by Kassel Abelson and David J. Fine, pages 773, 792. New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2002. (verbal abuse).

- Ellen Frankel. The Five Books of Miriam: A Woman's Commentary on the Torah, pages 188–90. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1996.

- W. Gunther Plaut. The Haftarah Commentary, pages 308–17. New York: UAHC Press, 1996.

- Elliot N. Dorff. "Assisted Suicide." New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 1997. YD 345.1997a. In Responsa: 1991–2000: The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement. Edited by Kassel Abelson and David J. Fine, pages 379, 380. New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2002. (implications for assisted suicide of God's ownership of the universe).

- Sorel Goldberg Loeb and Barbara Binder Kadden. Teaching Torah: A Treasury of Insights and Activities, pages 214–19. Denver: A.R.E. Publishing, 1997.

- Jacob Milgrom. "Jubilee: A Rallying Cry for Today's Oppressed: The laws of the Jubilee year offer a blueprint for bridging the gap between the have and have-not nations." Bible Review, volume 13 (number 2) (April 1997).

- Mary Douglas. Leviticus as Literature, pages 219–20, 242–44. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Susan Freeman. Teaching Jewish Virtues: Sacred Sources and Arts Activities, pages 332–46. Springfield, New Jersey: A.R.E. Publishing, 1999. (Leviticus 25:36, 43).

- Michael Hudson. "Proclaim Liberty Throughout the Land: The economic roots of the Jubilee." Bible Review, volume 15 (number 1) (February 1999).

- Michael Hudson … and forgive them their debts: Lending, Foreclosure and Redemption – From Bronze Age Finance to the Jubilee Year Dresden: ISLET-Verlag Dresden, 2018.

- Joel Roth. "Organ Donation." New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 1999. YD 336.1999-. In Responsa: 1991–2000: The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement. Edited by Kassel Abelson and David J. Fine, pages 194, 258–59. New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2002. (implications for organ donation of one's duty to assist another).

- Frank H. Gorman Jr. "Leviticus." In The HarperCollins Bible Commentary. Edited by James L. Mays, pages 163–64. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, revised edition, 2000.

- Sharon Brous and Jill Hammer. "Proclaiming Liberty throughout the Land." In The Women's Torah Commentary: New Insights from Women Rabbis on the 54 Weekly Torah Portions. Edited by Elyse Goldstein, pages 238–45. Woodstock, Vermont: Jewish Lights Publishing, 2000.

- Jacob Milgrom. Leviticus 23–27, volume 3B, pages 2145–271. New York: Anchor Bible, 2000.

- James Rosen. "Mental Retardation, Group Homes and the Rabbi." New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2000. YD 336:1.2000. In Responsa: 1991–2000: The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Conservative Movement. Edited by Kassel Abelson and David J. Fine, pages 337–46. New York: Rabbinical Assembly, 2002.

- Lainie Blum Cogan and Judy Weiss. Teaching Haftarah: Background, Insights, and Strategies, pages 406–12. Denver: A.R.E. Publishing, 2002.

- Michael Fishbane. The JPS Bible Commentary: Haftarot, pages 197–202. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2002.

- Robert S. Kawashima, "The Jubilee, Every 49 or 50 Years?" Vetus Testamentum, volume 53, number 1 (January 2003): pages 117–20.

- Joseph Telushkin. The Ten Commandments of Character: Essential Advice for Living an Honorable, Ethical, Honest Life, pages 290–91. New York: Bell Tower, 2003.

- Robert Alter. The Five Books of Moses: A Translation with Commentary, pages 653–60. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2004.

- Roy Gane. Leviticus, Numbers, pages 429–48. Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2004.

- Jacob Milgrom. Leviticus: A Book of Ritual and Ethics: A Continental Commentary, pages 298–317. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2004.

- Baruch J. Schwartz. "Leviticus." In The Jewish Study Bible. Edited by Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, pages 269–73. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Nancy Wechsler-Azen. "Haftarat Behar: Jeremiah 32:6–27." In The Women's Haftarah Commentary: New Insights from Women Rabbis on the 54 Weekly Haftarah Portions, the 5 Megillot & Special Shabbatot. Edited by Elyse Goldstein, pages 146–50. Woodstock, Vermont: Jewish Lights Publishing, 2004.

- John S. Bergsma. "Once Again, the Jubilee, Every 49 or 50 Years?" Vetus Testamentum, volume 55 (number 1) (January 2005): pages 121–25.

- Antony Cothey. “Ethics and Holiness in the Theology of Leviticus.” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, volume 30 (number 2) (December 2005): pages 131–51.

- Professors on the Parashah: Studies on the Weekly Torah Reading Edited by Leib Moscovitz, pages 216–24. Jerusalem: Urim Publications, 2005.

- Bernard J. Bamberger. "Leviticus." In The Torah: A Modern Commentary: Revised Edition. Edited by W. Gunther Plaut; revised edition edited by David E.S. Stern, pages 849–63. New York: Union for Reform Judaism, 2006.

- John S. Bergsma. The Jubilee from Leviticus to Qumran. Brill, 2006.

- Calum Carmichael. Illuminating Leviticus: A Study of Its Laws and Institutions in the Light of Biblical Narratives. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

- Suzanne A. Brody. "Lost Jubilee." In Dancing in the White Spaces: The Yearly Torah Cycle and More Poems, page 92. Shelbyville, Kentucky: Wasteland Press, 2007.

- Shai Cherry. "The Hebrew Slave." In Torah Through Time: Understanding Bible Commentary, from the Rabbinic Period to Modern Times, pages 101–31. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 2007.

- James L. Kugel. How To Read the Bible: A Guide to Scripture, Then and Now, pages 150, 291, 302, 345, 609–10, 683. New York: Free Press, 2007.

- Christophe Nihan. From Priestly Torah to Pentateuch: A Study in the Composition of the Book of Leviticus. Coronet Books, 2007.

- Yosef Zvi Rimon. Shemita: From the Sources to Practical Halacha. The Toby Press, 2008.

- The Torah: A Women's Commentary. Edited by Tamara Cohn Eskenazi and Andrea L. Weiss, pages 747–64. New York: URJ Press, 2008.

- Bruce Feiler. “Proclaim Liberty Throughout the Land.” In America's Prophet: Moses and the American Story, pages 35–72. New York: William Morrow, 2009.

- Roy E. Gane. "Leviticus." In Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary. Edited by John H. Walton, volume 1, pages 322–23. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2009.

- Reuven Hammer. Entering Torah: Prefaces to the Weekly Torah Portion, pages 185–87. New York: Gefen Publishing House, 2009.

- Alicia Jo Rabins. "Snow/Scorpions and Spiders." In Girls in Trouble. New York: JDub Music, 2009. (Miriam's perspective on her banishment).

- Jacob J. Staub. “Neither Oppress nor Allow Others to Oppress You: Parashat Behar (Leviticus 25:1–26:2).” In Torah Queeries: Weekly Commentaries on the Hebrew Bible. Edited by Gregg Drinkwater, Joshua Lesser, and David Shneer; foreword by Judith Plaskow, pages 174–78. New York: New York University Press, 2009.

- Stuart Lasine. “Everything Belongs to Me: Holiness, Danger, and Divine Kingship in the Post-Genesis World.” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, volume 35 (number 1) (September 2010): pages 31–62.

- Jerry Z. Muller. "The Long Shadow of Usury." In Capitalism and the Jews, pages 15–71. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010.

- Eric Nelson. "‘For the Land Is Mine': The Hebrew Commonwealth and the Rise of Redistribution." In The Hebrew Republic: Jewish Sources and the Transformation of European Political Thought, pages 57–87. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2010.

- Jeffrey Stackert. "Leviticus." In The New Oxford Annotated Bible: New Revised Standard Version with the Apocrypha: An Ecumenical Study Bible. Edited by Michael D. Coogan, Marc Z. Brettler, Carol A. Newsom, and Pheme Perkins, pages 178–80. New York: Oxford University Press, Revised 4th Edition 2010.

- Joseph Telushkin. Hillel: If Not Now, When? pages 52–54. New York: Nextbook, Schocken, 2010. (sale of a house in a walled city).

- David Graeber. Debt: The First 5000 Years. Brooklyn: Melville House, 2011. (debt cancellations, restoration of order).

- Sun-Jong Kim. "The Group Identity of the Human Beneficiaries in the Sabbatical Year (Lev 25:6)." Vetus Testamentum, volume 61 (number 1) (2011): pages 71–81.

- William G. Dever. The Lives of Ordinary People in Ancient Israel: When Archaeology and the Bible Intersect, pages 133–34, 290. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2012.

- Shmuel Herzfeld. "Are Jews Free Today." In Fifty-Four Pick Up: Fifteen-Minute Inspirational Torah Lessons, pages 179–83. Jerusalem: Gefen Publishing House, 2012.

- Stephen Beard. "Britain Wants To Be Hub for Sharia Banking." Marketplace. (July 18, 2013) (adaptation to Islam's parallel prohibition on charging interest).

- Nicholas Kristof. "When Emily Was Sold for Sex." The New York Times. (February 13, 2014): page A27. (human trafficking in our time).

- Ellen Frankel. "Taking Stock: How can we restore a balance to our lives and to the earth?" The Jerusalem Report, volume 25 (number 3) (May 19, 2014): page 47.

- Walk Free Foundation. The Global Slavery Index 2014. Australia, 2014.

- Joanna Paraszczuk. "Modernizing the Agricultural Sabbath: Science is called in to cope with the requirements of shmita." The Jerusalem Report, volume 25 (number 15) (November 3, 2014): pages 30–33.

- Pablo Diego-Rosell and Jacqueline Joudo Larsen. "35.8 Million Adults and Children in Slavery Worldwide." Gallup. (November 17, 2014).

- Jay Sklar. Leviticus: An Introduction and Commentary, pages 296–314. Downers Grove, Illinois: Inter-Varsity Press, 2014.

- Jonathan Sacks. Covenant & Conversation: A Weekly Reading of the Jewish Bible: Leviticus: The Book of Holiness, pages 359–400. Jerusalem: Maggid Books, 2015.

- Jonathan Sacks. Lessons in Leadership: A Weekly Reading of the Jewish Bible, pages 169–73. New Milford, Connecticut: Maggid Books, 2015.

- Jonathan Sacks. Essays on Ethics: A Weekly Reading of the Jewish Bible, pages 201–05. New Milford, Connecticut: Maggid Books, 2016.

- Mary Green Swig, Steven L. Swig, and Roger Hickey. "For the Student Debt Movement, JUBILEE is an Old Idea Made New." Campaign for America's Future. February 3, 2016.

- Shai Held. The Heart of Torah, Volume 2: Essays on the Weekly Torah Portion: Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy, pages 76–85. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2017.

- Steven Levy and Sarah Levy. The JPS Rashi Discussion Torah Commentary, pages 103–05. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2017.

- Pekka Pitkänen. “Ancient Israelite Population Economy: Ger, Toshav, Nakhri and Karat as Settler Colonial Categories.” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, volume 42 (number 2) (December 2017): pages 139–53.

- Julia Rhyder. "Sabbath and Sanctuary Cult in the Holiness Legislation: A Reassessment." Journal of Biblical Literature, volume 138, number 4 (2019): pages 721–40.

- U.S. Department of State. Trafficking in Persons Report: June 2019. (slavery in the present day).

- Abigail Pogrebin and Dov Linzer. It Takes Two to Torah: An Orthodox Rabbi and Reform Journalist Discuss and Debate Their Way Through the Five Books of Moses, pages 182–86. Bedford, New York: Fig Tree Books, 2024.

External links

[edit]

Texts

[edit]Commentaries

[edit]- Academy for Jewish Religion, California

- Academy for Jewish Religion, New York

- Aish.com

- American Jewish University—Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies[dead link]

- Chabad.org

- Hadar

- Jewish Theological Seminary

- MyJewishLearning.com

- Orthodox Union

- Pardes from Jerusalem

- Reconstructing Judaism

- Union for Reform Judaism

- United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism

- Yeshiva University

Behar

View on GrokipediaOverview

Position in the Annual Torah Reading Cycle

Parashat Behar constitutes the thirty-second weekly Torah portion (parashah) in the annual cycle of 54 parshiyot, which systematically divides the Five Books of Moses for weekly public reading on Shabbat.[8] This cycle commences with Parashat Bereshit on the Shabbat immediately following Simchat Torah and advances sequentially, ensuring the complete Torah is recited over the course of approximately one Hebrew year, culminating in Parashat V'Zot HaBerakhah on Simchat Torah.[9] Behar encompasses Leviticus 25:1–26:2, succeeding Parashat Emor (the thirty-first portion) and preceding Parashat Bechukotai (the thirty-third).[10] The precise timing of Behar's reading varies annually due to the lunisolar Hebrew calendar's intercalation, typically falling in late spring on the Gregorian calendar, such as May 21 in 5782 (2022 CE) or May 25 in 5784 (2024 CE).[11][4] In non-leap years, which feature 50 or 51 Shabbatot between Simchat Torah observances, certain portions including Behar are combined with adjacent ones to fit the cycle; thus, Behar-Bechukotai forms a double reading as the thirty-second and thirty-third portions in Diaspora Ashkenazi practice.[6] Leap years, with an extra month (Adar II), accommodate 52–54 Shabbatot, allowing more portions to be read singly, though customs differ: Israeli and Sephardic communities often maintain separate readings for Behar and Bechukotai regardless, prioritizing the full 54 divisions over calendar constraints.[12]Core Themes and Scope

Parashat Behar, spanning Leviticus 25:1–26:2, delineates laws governing agricultural rest, property transactions, and social equity in ancient Israelite society, framed as divine instructions given to Moses on Mount Sinai. The portion emphasizes the land's ultimate ownership by God, with Israelites positioned as temporary stewards obligated to permit periodic sabbatical cessation of cultivation. Every seventh year, known as Shemitah, fields must lie fallow, prohibiting sowing, pruning, or harvesting in the usual manner, while natural growth is deemed permissible for all, including the poor and animals, to foster communal reliance on divine sustenance rather than human labor. This mandate extends the weekly Sabbath principle to the earth itself, underscoring a theology of rest that applies to creation broadly.[1][4] Central to the scope is the Yovel, or Jubilee year, proclaimed on the Day of Atonement following seven Shemitah cycles (49 years), with the 50th year serving as a comprehensive societal reset. During Yovel, all ancestral lands revert to original tribal or familial owners, Hebrew indentured servants are emancipated, and no sowing or harvesting occurs, reinforcing prevention of perpetual land concentration or debt bondage among kin. These provisions address redemption mechanisms for sold fields or houses, valuing properties based on remaining years until Yovel, and distinguish between permanent alien purchases and redeemable Israelite holdings, reflecting a causal framework where economic cycles avert entrenched inequality without negating individual agency in transactions. Prohibitions against usury in loans to fellow Israelites, alongside commands to sustain the impoverished through interest-free aid and field gleanings, integrate welfare into covenantal obedience, positing that such practices ensure survival and dignity amid hardship.[13][14] Thematically, Behar promotes causal realism in socioeconomic policy by linking land productivity to divine sovereignty, cautioning that exploitation leads to collective vulnerability, as evidenced by assurances of bountiful prior harvests to cover the rest periods. It scopes beyond ritual to civil law, regulating servitude by mandating humane treatment of Hebrew bondsmen—treating them as hired workers rather than chattel—and culminating in an exhortation to observe commandments faithfully, tying observance to the Sinai revelation for holistic fidelity. Traditional exegesis views these as blueprints for a stable agrarian polity, where periodic liberation curtails oligarchic tendencies, though historical implementation varied due to enforcement challenges in post-exilic contexts.[2][15]Textual Structure

Division into Traditional Aliyot

In traditional Jewish liturgy, Parashat Behar (Leviticus 25:1–26:2) is divided into seven aliyot for the Shabbat Torah reading, with each aliyah consisting of a contiguous set of verses assigned to an individual who recites the blessings before and after the reading.[16][17] These divisions follow established Ashkenazic and Sephardic customs, ensuring that no aliyah ends mid-sentence or violates Talmudic guidelines from Megillah 22a–23a on minimum verse lengths and parashah boundaries.[18] The aliyot emphasize the parashah's progression from agricultural sabbaticals to economic and social regulations, culminating in foundational commandments:| Aliyah | Verse Range | Key Content |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lev. 25:1–13 | Introduction to shemitah (sabbatical year) and yovel (Jubilee), including land rest and shofar proclamation on Yom Kippur.[16] |

| 2 | Lev. 25:14–18 | Ethical commerce rules, pricing land sales relative to Jubilee years, and prohibitions on oppression.[16] |

| 3 | Lev. 25:19–24 | Divine provision during sabbatical years and the inalienable status of land as God's property.[16] |

| 4 | Lev. 25:25–28 | Redemption rights for ancestral fields, with calculations based on remaining Jubilee years.[16] |

| 5 | Lev. 25:29–38 | Rules for redeeming houses in cities (walled vs. unwalled), Levitical perpetual redemption rights, and bans on usury among Israelites.[16] |

| 6 | Lev. 25:39–46 | Treatment of indentured Hebrew servants as hired workers, not slaves, with distinctions from non-Hebrew servitude.[16] |

| 7 | Lev. 25:47–26:2 | Redemption from foreign servitude, Jubilee manumission, and concluding exhortations against idolatry, to keep Shabbat, and to revere the sanctuary.[16][17] |