Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

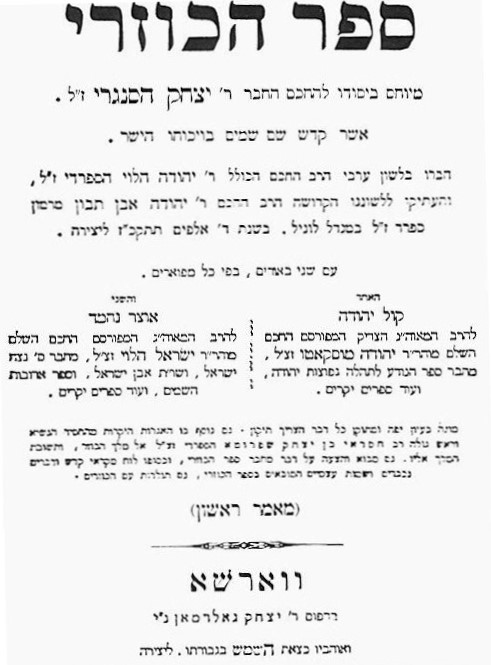

Kuzari

View on WikipediaThe Kuzari, full title Book of Refutation and Proof on Behalf of the Despised Religion[1] (Judeo-Arabic: כתאב אלרד ואלדליל פי אלדין אלדׄליל; Arabic: كتاب الحجة والدليل في نصرة الدين الذليل: Kitâb al-ḥujja wa'l-dalîl fi naṣr al-dîn al-dhalîl), also known as the Book of the Khazar (Hebrew: ספר הכוזרי: Sefer ha-Kuzari),[2] is one of the most famous works of the medieval Spanish Jewish philosopher, physician, and poet Judah Halevi, completed in the Hebrew year 4900 (1139-40CE).

Key Information

Originally written in Arabic, prompted by Halevi's contact with a Spanish Karaite,[3] it was then translated by numerous scholars, including Judah ben Saul ibn Tibbon, into Hebrew and other languages, and is regarded as one of the most important apologetic works of Jewish philosophy.[2] Divided into five parts (ma'amarim "articles"), it takes the form of a dialogue between a rabbi and the king of the Khazars, who has invited the former to instruct him in the tenets of Judaism in comparison with those of the other two Abrahamic religions: Christianity and Islam.[2]

Historical foundation

[edit]The Kuzari takes place during the conversion of a Khazar king and some Khazar nobles to Judaism. The historicity of the event is debated. The Khazar Correspondence, along with other historical documents, are said to indicate a conversion of the Khazar royalty and nobility to Judaism.[4][5][6][7] A minority of scholars, among them Moshe Gil and Shaul Stampfer, have challenged the document's claim to represent a real historical event.[8][9] The scale of conversions within the Khazar Khaganate (if, indeed, any occurred) is unknown.

Influence of the Kuzari

[edit]The Kuzari's emphasis on the uniqueness of the Jewish people, the Torah, and the land of Israel bears witness to a radical change of direction in Jewish thinking at that juncture in history, which coincided with the Crusades.[10] Setting aside the possible exception of the work of Maimonides, it had a profound impact on the subsequent development of Judaism,[11][12] and has remained central to Jewish religious tradition.[13]

Given what has been generally regarded as its pronounced anti-philosophical tendencies, a direct line has been drawn, prominently by Gershom Scholem, between it and the rise of the anti-rationalist Kabbalah movement.[14]

The ideas and style of the work played an important role in debates within the Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment) movement.[15]

Halevi claims that the knowledge of the Greeks and Romans had actually originated with Solomon and the ancient Hebrews and had then made their way via the Persians, Medians, and Chaldeans, their origin forgotten.[16][17]

Translations

[edit]In addition to the 12th-century Hebrew translation by Judah ben Saul ibn Tibbon,[18] which passed through eleven printed editions (1st ed. Fano, 1506), another (albeit less successful) Hebrew rendering was made by Judah ben Isaac Cardinal at the beginning of the 13th century. Only portions of latter translation have survived.

In 1887, the text was published in its original Arabic for the first time by Hartwig Hirschfeld; in 1977, an Arabic critical translation was published by David H. Baneth. Parallel to his Arabic edition, Hirschfeld also published a critical edition of the Ibn Tibbon translation of the text that was based upon six medieval manuscripts. In 1885, Hirschfeld published the first German translation, and in 1905 his English translation appeared. In 1972, the first modern translation, by Yehudah Even-Shemuel, into Modern Hebrew from the Arabic original was published. In 1994, a French translation by Charles Touati from the Arabic original was published. In 1997, a Hebrew translation by Rabbi Yosef Qafih from the Arabic original was published, which is now in its fourth edition (published in 2013). A 2009 English translation by Rabbi N. Daniel Korobkin is in print by Feldheim Publishers.

Contents

[edit]First essay

[edit]Introduction

[edit]After a short account of the incidents preceding the king's conversion and of his conversations with a philosopher, a Christian, and a Muslim concerning their respective beliefs, a rabbi appears in the discussion. His first statement startles the king, for instead of giving him proofs of the existence of God, he asserts and explains the miracles performed by God in favor of the Israelites.

The king expresses his astonishment at this exordium, which seems to him incoherent. The rabbi replies that the existence of God, the creation of the world, and other doctrines taught by the Jewish religion do not need any speculative demonstrations. Further, he presents the principle upon which his religious system is founded: that revealed religion is far superior to natural religion. The aim of ethical self-cultivation, which is the object of religion, is not to create in humans good intentions but to cause them to perform good deeds. This aim cannot be attained by philosophy, which is undecided about the nature of good, but can be secured by a religious education and life, which teaches what is good. As science is the sum of all truth found by successive generations, so religious training is based upon a set of traditions; in other words, history is an important factor in the development of human culture and science.

Creatio ex nihilo

[edit]Halevi writes that, as the Jews are the only depositaries of a written history of the development of the human race from the beginning of the world, the superiority of their traditions cannot be denied. Halevi asserts that no comparison is possible between Jewish culture, which in his view is based upon religious truth, and Greek culture, which is based upon science only. He holds that the wisdom of Greek philosophy lacked the divine support with which the Israelite prophets were endowed. Had a trustworthy tradition that the world was created out of nothing been known to Aristotle, he would have supported it by at least as strong arguments as those advanced by him to prove the eternity of matter. However, belief in the eternity of matter is not absolutely contrary to Jewish religious ideas: the biblical narrative of the Creation refers only to the beginning of the human race, and does not preclude the possibility of preexistent matter.

Still, relying upon tradition, Judaism assumes creatio ex nihilo, the theological position that the universe was created from nothing by a divine act. This assumption can be supported by compelling philosophical and theological arguments, which are comparable in strength to those favoring the concept of the eternity of matter—an idea proposing that the universe has no beginning and has existed infinitely in time. The objection that an absolutely perfect and infinite God could not have produced imperfect and finite beings—made by the Neoplatonists to the principle of creatio ex nihilo—is not removed by attributing the existence of all mundane things to the action of nature; for the latter is only a link in the chain of causes having its origin in the First Cause, which is God.

Superiority of his faith

[edit]Halevi then attempts to demonstrate the superiority of Judaism. The preservation of the Israelites in Egypt and in the wilderness, God's revelation of the Torah on Mount Sinai, and Israel's later history are, to him, evident proofs of its superiority. He impresses upon the king that the favor of God can be won only by following God's precepts in their totality, and that those precepts are binding only on Jews. The question of why the Jews were favored with God's instruction is answered in the Kuzari in line 95 of chapter 1: it was based upon their being descended from Adam, God's first child, who was perfect.[19] Later, Noah's most pious son was Shem. His most pious son was Arpachshad. Abraham was Arpachshad's descendant, Isaac was Abraham's most pious son, and Jacob was Isaac's most pious son. The sons of Jacob were all worthy, and their children became the Jews. The rabbi then shows (chapter 1:109–121) that the immortality of the soul, resurrection, reward, and punishment are all denoted in the Hebrew Bible and referred to in Jewish writings.

Second essay

[edit]Question of attributes

[edit]In the second essay, Halevi enters into a detailed discussion of some of the theological questions hinted at in the preceding one. To these belong, in the first place, those of the divine attributes. Halevi rejects entirely the doctrine of essential attributes, which had been propounded by Saadia Gaon and Bahya ibn Paquda.[further explanation needed] For him, there is no difference between essential and other attributes. Either the attribute affirms a quality in God, in which case essential attributes cannot be applied to him more than can any other, because it is impossible to predicate anything of him, or the attribute expresses only the negation of the contrary quality, and in that case, there is no harm in using any kind of attributes. Accordingly, Halevi divides all the attributes found in the Hebrew Bible into three classes: active, relative, and negative, which last class comprises all the essential attributes expressing mere negations.

Halevi enters into a lengthy discussion on the question of attributes being closely connected with that of anthropomorphism. Although opposed to the conception of God's corporeality as contrary to Jewish scripture, he would consider it wrong to reject all the sensuous concepts of anthropomorphism, as there is something in these ideas which fills the human soul with the awe of God.

The remainder of the essay comprises dissertations on the following subjects: the excellence of Israel, the land of prophecy, which is to other countries what the Jews are to other nations; the sacrifices; the arrangement of the Tabernacle, which, according to Halevi, symbolizes the human body; the prominent spiritual position occupied by Israel, whose relation to other nations is that of the heart to the limbs; the opposition evinced by Judaism toward asceticism, in virtue of the principle that the favor of God is to be won only by carrying out his precepts, and that these precepts do not command humans to subdue the inclinations suggested by the faculties of the soul, but to use them in their due place and proportion; and the excellence of the Hebrew language, which, although sharing now the fate of the Jews, is to other languages what the Jews are to other nations and what Israel is to other lands.

Third essay: The oral tradition

[edit]The third essay is devoted to the refutation of the teachings of Karaism and to the history of the development of the oral tradition in the Mishnah and Talmud. Halevi shows that there is no means of carrying out the precepts without having recourse to oral tradition; that such tradition has always existed may be inferred from many passages of the Hebrew Bible, the very reading of which is dependent upon it, since there were no vowels or accents in the original text.

Fourth essay: Names of God

[edit]The fourth essay opens with an analysis of the various names of God found in the Hebrew Bible. According to Halevi, all these names, with the exception of the Tetragrammaton, are attributes expressing the various states of God's activity in the world. The multiplicity of names no more implies a multiplicity in his essence than do the multifarious influences of the rays of the sun on various bodies imply a multiplicity of suns. To the prophet's intuitive vision, the actions proceeding from God appear under the images of the corresponding human actions. Angels are God's messengers, either existing for a long time or created only for special purposes.

Halevi shifts from discussing God's names and the nature of angels to emphasizing that the prophets offer a more genuine understanding of God than philosophers do. While he shows deep respect for the Sefer Yetzirah—quoting many passages from it—he quickly clarifies that Abraham's ideas were held by the patriarch before God revealed himself to him. The essay ends with examples of ancient Hebrew knowledge in astronomy and medicine.

Fifth essay: Arguments against philosophy

[edit]The fifth and last essay is devoted to a criticism of the various philosophical systems known at the time of the author. Halevi attacks by turns Aristotelian cosmology, psychology, and metaphysics. To the doctrine of emanation, based, according to him, upon the Aristotelian cosmological principle that no simple being can produce a compound being, he objects in the form of the following query: "Why did the emanation stop at the lunar sphere? Why should each intelligence think only of itself and of that from which it issued and thus give birth to one emanation, thinking not at all of the preceding intelligences, and thereby losing the power to give birth to many emanations?"

He argues against the theory of Aristotle that the soul of humankind is in its mind and that only the souls of philosophers will be united—after the death of their bodies—with the active intellect. "Is there," he asks, "any curriculum of the knowledge one has to acquire to win immortality? How is it that the soul of one man differs from that of another? How can one forget a thing once thought of?" and many other questions of the kind. He shows himself especially severe against the Motekallamin, whose arguments on the creation of the world, on God, and his unity he terms dialectic exercises and mere phrases.

However, Halevi is against limiting philosophical speculation to matters concerning creation and God; he follows the Greek philosophers in examining the creation of the material world. Thus, he admits that every being is made up of matter and form. The movement of celestial spheres formed the sphere of the elements, from the fusion of which all beings were created. This fusion, which varied according to climate, gave to matter the potentiality to receive from God a variety of forms: from the mineral, which is the lowest in the scale of creation, to humankind, which is the highest because of its possessing, in addition to the qualities of the mineral, vegetable, and animal, a hylic intellect that is influenced by the active intellect. This hylic intellect, which forms the rational soul, is a spiritual substance, not an accident, and therefore imperishable.

Discussions concerning the soul and its faculties naturally lead to the question of free will. Halevi upholds the doctrine of free will against the Epicurean and the Fatalist and endeavors to reconcile it with the belief in God's providence and omniscience.

Commentaries on the book

[edit]Six commentaries were printed in the fifteenth century, of which four are known. All were written in Hebrew:

- Edut LeYisrael (עדות לישראל, 'Witness to Yisrael') by Rabbi Shlomo ben Menachem. (This commentary is lost.)[20]

- Kol Yehudah (קול יהודה, 'Voice of Yehudah') by Rabbi Judah Moscato.

Commentaries by two students of Rabbi Shlomo ben Menachem: Rabbi Yaakov ben Parisol and Rabbi Netanel ben Nechemya Hacaspi.[21]

In the 20th century, two more commentaries were written, including:

- The Kuzari – Commentary by Rabbi Shlomo Aviner (four volumes).

- The Explained Kuzari by Rabbi David Cohen (three volumes).

Bibliography

[edit]- Yehuda ha-Levi. Kuzari. Translated by N. Daniel Korobkin as The Kuzari: In Defense of the Despised Faith. Northvale, N.J.: Jason Aronson, 1998. 2nd Edition (revised) published Jerusalem: Feldheim Publishers, 2009. (ISBN 978-1-58330-842-4)

- Yechezkel Sarna. Rearrangement of the Kuzari., Transl. Rabbi Avraham Davis. New York: Metsudah, 1986

- Adam Shear. The Kuzari and the shaping of Jewish identity, 1167–1900. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008 ISBN 978-0-521-88533-1

- D. M. Dunlop. History of the Jewish Khazars. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1954.

- Leo Strauss. "The Law of Reason in the Kuzari" in: Proceedings of the American Academy for Jewish Research, XIII (1943), pp. 47-96.

References

[edit]- ^ Dianna Lynn Roberts-Zauderer, Metaphor and Imagination in Medieval Jewish Thought: Moses ibn Ezra, Judah Halevi, Moses Maimonides, and Shem Tov ibn Falaquera . Palgrave Macmillan 2019 ISBN 978-3-030-29422-9 p.73.

- ^ a b c Silverstein, Adam J. (2015). "Abrahamic Experiments in History". In Blidstein, Moshe; Silverstein, Adam J.; Stroumsa, Guy G. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Abrahamic Religions. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 43–51. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199697762.013.35. ISBN 978-0-19-969776-2. LCCN 2014960132. S2CID 170623059.

- ^ Sarah Stroumsa, Maimonides in His World: Portrait of a Mediterranean Thinker, Princeton University Press 2011 ISBN 978-0-691-15252-3 p.40

- ^ Pritsak, Omeljan (September 1978). "The Khazar Kingdom's Conversion to Judaism". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 3 (2): 261–281.

- ^ Golden, Peter B. (1983). "Khazaria and Judaism". Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi. 3: 127–156.

- ^ Shapira, Dan (2008). "Jews in Khazaria". Encyclopedia of the Jewish Diaspora: Origins, Experiences, and Culture. Vol. 3. ABC-CLIO. pp. 1097–1104. ISBN 978-1851098736.

- ^ Brook, Kevin A. (2018). "Chapter 6: The Khazars' Conversion to Judaism". The Jews of Khazaria (3rd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-5381-0342-5.

- ^ Shaul Stampfer,Did the Khazars Convert to Judaism?, in Jewish Social Studies 2013, volume 19, issue 3-4 pp.1–72

- ^ Moshe Gil, Did the Khazars Convert to Judaism?, doi = 10.2143/REJ.170.3.2141801 in Revue des Études Juives, July–December 2011, volume 170, issue 3–4 pp.429–441.

- ^ Eliezer Schweid, The Land of Israel: National Home Or Land of Destiny, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press 1985 ISBN 978-0-838-63234-5 p.71.

- ^ Howard Kreisel, Prophecy: The History of an Idea in Medieval Jewish Philosophy, Springer 2012 ISBN 978-9-401-00820-4 p.95.

- ^ Henry Toledano, The Sephardic Legacy: Unique Features and Achievements , University of Scranton Press ISBN 978-1-589-66205-6·2010 p.184

- ^ Yonatan Mendel,The Creation of Israeli Arabic: Security and Politics in Arabic Studies in Israel, Springer 2014 ISBN 978-1-137-33737-5 pp.14-15.

- ^ Jonathan Dauber, Knowledge of God and the Development of Early Kabbalah, BRILL 2012 ISBN 978-9-004-23427-7 p.128 :'In my opinion there is a direct connection between Jehudah Halevi, the most Jewish of Jewish philosophers, and the Kabbalists. For the legitimate trustees of his spiritual heritage have been mystics, and not the succeeding generations of Jewish philosophers.'.

- ^ Adam Shear, 'Judah Halevi's Kuzari in the Haskalah: The reinterpretration and Reimaging of a Medieval Work,' in Ross Brann, Adam Sutcliffe,Renewing the Past, Reconfiguring Jewish Culture: From al-Andalus to the Haskalah, University of Pennsylvania Press ISBN 978-0-812-23742-9 pp.71-91

- ^ Fuss, Abraham M. (1994). "The Study of Science and Philosophy Justified by Jewish Tradition". The Torah U-Madda Journal. 5: 101–114. ISSN 1050-4745. JSTOR 40914819.

- ^ Shavit, Yaacov (2020-08-10), "Chapter Eight. Solomon, Aristoteles Judaicus, and the Invention of a Pseudo- Solomonic Library", An Imaginary Trio, De Gruyter, pp. 172–190, doi:10.1515/9783110677263-010/html, ISBN 978-3-11-067726-3, retrieved 2025-05-08

- ^ The Kuzari Book, Manuscript, Pharma-Italy, 14th Century, translated by Yehuda Ibn Tibon, Ktiv - National Library Israel website.

- ^ "Kuzari 1:101". Sefaria. Retrieved 18 October 2025.

- ^ Shwartz, Dov. Study of Philosophical Circles in Spain and Provence, before the Expulsion. page 12. Language: Hebrew.

- ^ For more information, see the translation of Yehudah Even-Shemuel, preface, p. 53

External links

[edit]- Resources on the Kuzari itself

- Complete English translation by Hartwig Hirschfeld (1905) at Wikisource.

- Complete Hebrew translation based on that of Rabbi Judah ibn Tibbon.

- Hebrew Fulltext

- Arabic original in Judeo-Arabic.

- Kuzari Video Lessons (Hebrew)[usurped] Link not working.

Kuzari

View on GrokipediaHistorical Context and Authorship

Yehuda Halevi's Life and Intellectual Background

Yehuda Halevi (c. 1075–1141), also known as Judah ha-Levi or Judah ben Samuel, was born in Tudela, in the Kingdom of Navarre (present-day Spain), during a period of relative cultural flourishing for Jews under Muslim rule in Al-Andalus.[4] Raised in an environment blending Sephardic Jewish traditions with Arabic literary and scientific influences, Halevi received a broad education encompassing biblical and Talmudic studies, Hebrew poetry, and elements of philosophy.[5] His family background supported early intellectual pursuits, and by adulthood, he had relocated to cities like Toledo, Córdoba, and Granada, where he trained as a physician and gained prominence in court circles.[6] Halevi practiced medicine, reportedly serving viziers and possibly the Almoravid ruler, while composing over 800 Hebrew poems—secular, liturgical, and philosophical—that earned him acclaim as one of medieval Judaism's greatest poets.[1] In his professional life, Halevi navigated the tensions of Almoravid rule, which imposed stricter Islamic governance on dhimmis after 1090, yet he thrived intellectually amid interactions with Muslim scholars and poets.[7] His poetic output reflected mastery of Arabic meters adapted to Hebrew, often exploring themes of divine love, exile, and human longing, with a corpus preserved largely through Genizah fragments and medieval anthologies.[8] Toward the end of his life, around 1140, Halevi experienced a profound spiritual shift, composing Zionides—elegiac poems yearning for Jerusalem—and embarking on a pilgrimage from Spain. He reached Alexandria in 1141, intending to settle in the Land of Israel, but died shortly after, possibly in Egypt or upon nearing Jerusalem's gates, amid unverified accounts of martyrdom.[8][6] Intellectually, Halevi engaged deeply with contemporaneous philosophical currents, studying Neoplatonist and emerging Aristotelian ideas prevalent in Islamic Spain, including works by Avicenna and al-Ghazali, while drawing from Jewish rationalists like Saadia Gaon (882–942).[1] He initially absorbed these influences during his youth but increasingly critiqued their abstraction from historical revelation and prophetic experience, advocating instead for Judaism's foundation in the collective Sinai event and the enduring election of Israel as a nation.[1] This perspective positioned him against the universalist rationalism of philosophers, whom he viewed as diluting particularist truths, favoring empirical tradition and divine influence over pure reason.[5] Halevi's thought also incorporated linguistic and poetic dimensions, seeing Hebrew as uniquely revelatory, informed by his bilingual immersion in Arabic and Hebrew literary traditions.[9]Inspiration from the Khazar Conversion

The Kuzari employs the legend of the Khazar conversion to Judaism as its central narrative framework, depicting a dialogue between a Khazar king seeking religious truth and a Jewish rabbi who guides him toward Judaism. Yehuda Halevi adapted this motif to illustrate a rational inquiry into faiths, where the king first consults pagan, philosophical, Christian, and Muslim representatives before being persuaded by the rabbi's emphasis on Judaism's national revelation at Sinai.[10][11] Medieval accounts, including Arabic sources such as those by al-Mas'udi (d. 956) and the 10th-century Khazar Correspondence between Spanish Jewish diplomat Hasdai ibn Shaprut and Khazar King Joseph, describe the Khazars—a Turkic people ruling a multi-ethnic empire in the Caucasus, southern Russia, and Ukraine from roughly 650 to 969—as having adopted Judaism among their elite around 740 or in the 9th century.[12][13] These texts portray the conversion as resulting from debates among Jewish, Christian, and Muslim envoys, with Judaism prevailing due to its perceived historical authenticity. Jewish refugees from Byzantine persecution and Radhanite merchants likely influenced this process, introducing Judaic practices to the court.[12] Halevi, aware of these traditions through earlier Jewish writings, transformed the legend into a philosophical device to defend rabbinic Judaism against Karaite schismatics and rationalist philosophers like those influenced by Aristotle. By setting the dialogue in Khazar lands—a distant, non-Semitic context—he underscored Judaism's universal appeal, independent of ethnic origins, and highlighted the improbability of fabricated mass revelations, as the Khazar king's subjects could verify the faith's claims.[14] Contemporary historians, however, question the legend's historicity and scope, citing scant archaeological evidence—such as the absence of synagogues, Hebrew inscriptions, or Judaic artifacts in excavated Khazar sites—and suggesting the conversion was confined to the khagan and nobility, with Islam and Christianity dominating among the populace. Seals bearing menorahs and names like "Sar Shlomo" provide limited corroboration, but no mass adoption is evident, potentially exaggerating the event for propagandistic purposes in medieval narratives. Halevi's use thus relies on the inspirational power of the tradition rather than empirical verification, prioritizing its apologetic utility in arguing for Judaism's experiential foundation over abstract philosophy.[15][16]Composition Date and Motivations

The Kuzari, formally known as the Book of Refutation and Proof on Behalf of the Despised Religion, was composed by Yehuda Halevi in stages, with initial drafts begun shortly after 1108 CE in response to queries from an unnamed heretical interlocutor, likely a Karaite thinker challenging core tenets of rabbinic Judaism.[1] The text was finalized around 1140 CE, coinciding with Halevi's preparations to leave Spain for the Land of Israel, shortly before his death in 1141 CE.[17] Written originally in Judeo-Arabic, it represents Halevi's culminating philosophical effort amid the cultural and religious tensions of al-Andalus under Almoravid rule. Halevi's principal motivation was to defend Judaism's foundational claims against rationalist philosophy, particularly the Aristotelian-Neoplatonic synthesis advanced by Muslim thinkers like al-Farabi and Avicenna, which prioritized abstract demonstrations of God's existence over historical revelation and divine particularism.[1] He critiqued these approaches for rendering God too remote and impersonal, incompatible with the biblical portrait of an active, covenant-making deity, and sought to demonstrate Judaism's epistemic superiority through the unverifiable-yet-public national revelation at Sinai, which no other faith could parallel.[1] The work also targeted Karaite denial of the oral law by affirming the continuity of tradition from Sinai, while refuting Christian and Muslim assertions that Judaism had been abrogated by subsequent individual revelations to Jesus or Muhammad.[1] By framing the arguments as a dialogue between the Khazar king and representatives of various faiths, culminating in the triumph of the Jewish sage's position, Halevi aimed to bolster the faith of diaspora Jews facing assimilation, persecution, and intellectual doubt, underscoring Judaism's unique historical validation over speculative mysticism or philosophy.[1] This structure privileged empirical testimony and causal realism in religious epistemology, countering the era's dominant trends toward universalist rationalism that diminished Judaism's distinctiveness.[18]Literary Form and Overall Structure

Dialogue Format and Narrative Device

The Kuzari is structured as a philosophical dialogue, primarily featuring exchanges between the King of the Khazars, initially portrayed as a pious pagan seeker, and a Jewish rabbi who serves as the primary exponent of Jewish doctrine.[1] An anonymous narrator frames the narrative, recounting the events as a historical recollection set in the Khazar kingdom approximately 400 years prior to the work's composition.[1] The dialogue begins with the king experiencing a recurring dream in which an angel declares, "Your intention is pleasing to God, but your actions are not," critiquing his pagan rituals despite his virtuous aims.[1][11] This dream functions as the central narrative device, catalyzing the king's quest for the true religion that aligns divine favor with proper conduct.[1] Motivated by the vision, the king summons and interrogates representatives from philosophy, Christianity, and Islam, finding their arguments deficient before turning to the rabbi for in-depth discourse.[11] The rabbi's responses, delivered in a question-and-answer format, systematically refute alternative worldviews and articulate Judaism's foundational principles, culminating in the king's conversion along with his court.[1] This setup draws on the semi-legendary account of the Khazars' adoption of Judaism around 740 CE, employing the historical motif to lend authenticity and dramatic progression to the philosophical inquiry.[11] The dialogue form facilitates a dynamic exploration of theological concepts, with the king's probing questions mirroring potential objections from rationalist critics, while the rabbi's replies emphasize empirical validation and historical testimony over abstract speculation.[1] Brief interventions by secondary figures, such as the philosopher, Christian, and Muslim scholars, highlight the limitations of their traditions in contrast to Judaism's claimed uniqueness.[1] Through this device, Halevi transforms a static defense of faith into an engaging narrative that underscores the superiority of revealed religion.[1]Division into Five Essays

The Kuzari is structured as a series of five essays, or ma'amarim, which organize the philosophical dialogue between the Khazar king and the rabbi into a logical progression, beginning with the king's initial inquiry into true religion and culminating in a comprehensive defense of Judaism against competing worldviews.[6] This division allows Yehuda Halevi to build arguments incrementally, with each ma'amar addressing a distinct phase of inquiry while referencing prior discussions to maintain continuity.[19] The format reflects medieval Jewish philosophical treatises, emphasizing dialectical advancement over linear exposition.[6] The first ma'amar sets the foundational narrative, recounting the king's dream-vision and his consultations with representatives of philosophy, Islam, and Christianity, before the rabbi introduces the empirical basis of Judaism through national revelation at Sinai, prioritizing historical miracles over abstract proofs.[6] The second ma'amar examines divine attributes, rejecting anthropomorphic interpretations while affirming Judaism's unique election, the sanctity of the Land of Israel, and the Hebrew language as vehicles of divine influence.[6] The third ma'amar shifts to defending the authority of oral tradition against scriptural literalism, such as Karaite challenges, underscoring the Talmud's role in interpreting and preserving Mosaic precepts for practical observance.[6] In the fourth ma'amar, the discussion turns to esoteric elements like the divine names, angelic intermediaries, and the superiority of prophetic intuition over rational deduction, illustrated by Hebrew etymologies and scientific insights derived from sacred texts.[6] The fifth and final ma'amar provides a capstone critique of Aristotelian philosophy and Islamic kalam, upholding human free will, the immortality of the soul, and creation ex nihilo as aligned with revelation rather than pagan-influenced metaphysics.[6] This sequential division ensures that the king's conversion is portrayed as intellectually rigorous, with each essay resolving objections raised in the preceding ones and preparing the ground for deeper explorations.[19]Core Arguments and Contents

First Essay: From Paganism to Monotheism and National Revelation

The First Essay of The Kuzari opens with the narrative of the Khazar king, who receives a divine warning in a dream from an angel: his pious intentions are commendable, but his practices do not attain the highest perfection possible for humanity. This prompts the king to investigate various doctrines, beginning with a philosopher who posits that true perfection lies in intellectual contemplation of abstract principles, such as the eternity of the universe and the immortality of the soul, without reliance on divine intervention or empirical miracles. The king rejects this, as it lacks demonstrable actions or historical validation of divine favor, emphasizing instead a quest for a path evidenced by tangible outcomes like prosperity, moral elevation, and prophetic influence. Subsequent consultations with a Christian and a Muslim representative highlight the limitations of religions grounded in private revelations to individual founders—Jesus and Muhammad, respectively—which the king views as unverifiable and prone to fabrication, since they depend on the credibility of solitary witnesses transmitted over generations without mass corroboration. The king then encounters a Jewish rabbi, who argues that authentic religion must originate in deeds preceding doctrines, tracing humanity's spiritual history from Adam's original monotheistic knowledge of the Creator, which degraded into pagan idolatry through ancestor worship, astral cults, and elemental veneration as people sought intermediaries for divine influence. Prophets emerged sporadically among nations to restore monotheism by demonstrating miracles and moral guidance, but these interventions were typically private or limited, allowing for doubt regarding their authenticity. Halevi posits that idolatry arose from a distorted intuition of divine unity, where humans attributed creative power to visible phenomena like stars or statues, mistaking them for independent agents rather than creations subservient to a singular God.[1] The essay's core pivot to Judaism underscores the uniqueness of its foundational event: the national revelation at Mount Sinai, where God communicated directly with the entire Israelite people—estimated at over 600,000 adult males plus families, totaling several million—amidst empirically observable phenomena such as thunder, lightning, and the giving of the tablets. This mass witness, detailed in Exodus 19–20, serves as irrefutable proof because no other religion claims a comparable public theophany; fabricating such an account would require convincing an entire nation and its descendants of an event their forebears collectively experienced or denied, rendering invention causally implausible.[1] Halevi contrasts this with private prophecies, which lack intergenerational verification and could be invented by a single author, arguing that Sinai's collective testimony establishes monotheism not through abstract reasoning but through historical continuity and empirical inescapability, as the event's memory persists unchallenged in Jewish tradition despite opportunities for denial. The rabbi thus frames Judaism's superiority in originating from this verifiable divine encounter, which elevated a nation from potential paganism to a covenantal monotheism sustained by ongoing observance.Second Essay: Attributes of God and Rejection of Philosophical Abstractions

In the second essay of the Kuzari, Yehuda Halevi, through the dialogue between the Rabbi and the Khazar king, examines the nature of divine attributes, emphasizing their relational and action-oriented character rather than essential properties that might imply composition or multiplicity in God. Halevi rejects the philosophical doctrine of essential attributes, which posits intrinsic qualities in the divine essence, arguing that such views compromise God's absolute unity.[20] Instead, he accepts relative attributes—such as "merciful," "jealous," or "just"—as descriptors borrowed from human experiences of reverence and denoting God's interactions with creation, without ascribing literal emotions or limitations to the divine.[20] These attributes reflect effects observable in the world, like divine providence manifesting as justice or compassion toward humanity.[1] Halevi addresses biblical anthropomorphisms, such as God "seeing," "hearing," or "descending" upon Sinai, interpreting them metaphorically to signify the impacts of divine actions rather than implying a corporeal form.[20] For instance, the "descent" at Sinai represents the manifestation of God's glory (kavod) as perceptible rays of divine influence, akin to light affecting the senses, not a physical movement.[20] This approach preserves God's incorporeality while affirming the biblical language's validity in conveying real providential events, contrasting with philosophical tendencies to dismiss such expressions as mere allegory devoid of concrete efficacy.[1] Central to the essay is Halevi's critique of Aristotelian and Neoplatonic abstractions, which portray God as a detached, purely intellectual first cause operating through necessary emanations without will or particular intervention.[1] The Rabbi argues that such models render divine will illusory, reducing creation to impersonal necessity and precluding miracles, prophecy, or specific historical acts like the Exodus.[20] Halevi counters that evidence of purposeful design in the universe—such as the ordered motion of celestial bodies—demonstrates an active divine volition, directly causative rather than mediated by abstract intermediaries.[20] Philosophers' denial of God's speech or direct influence, he contends, undermines the empirical reality of revelation, as the Ten Commandments' utterance exemplifies unmediated divine agency.[20] The essay links these attributes to Israel's unique status, positing the divine presence (Shekhinah) as an intensified influence channeled through the Jewish people and the Land of Israel, enabling prophecy and ritual efficacy.[20] Halevi describes the Shekhinah and glory as luminous extensions of God's power, most potent in Jerusalem and responsive to Israel's purity and adherence to covenantal laws, such as those given to Abraham.[20] This relational dynamic rejects universalistic philosophical emanations, insisting on a covenantal particularism where divine attributes manifest historically and nationally, fostering Israel's holiness amid diaspora challenges.[20]Third Essay: Oral Tradition and Historical Continuity

The Third Essay of the Kuzari examines the transmission and preservation of Jewish law through an unbroken oral tradition, emphasizing its essential role in enabling the practical observance of the Torah's commandments. Halevi, via the dialogue between the Rabbi (Haver) and the Khazar King, argues that the written Torah alone provides insufficient detail for fulfillment of the mitzvot, necessitating supplementary oral instructions given concurrently at Sinai. For instance, the Rabbi illustrates that specifics such as the form of tefillin, the proper sounding of the shofar, or the construction of the sukkah are absent from the written text but required for compliance, rendering isolated reliance on scripture impractical.[6][1] Central to the essay is the historical chain of transmission, traced from Moses—who received both written and oral Torah at Sinai around 1312 BCE—through Joshua, the elders, prophets, and the Men of the Great Assembly, culminating in the sages who codified the Mishnah under Rabbi Judah the Prince circa 200 CE. This lineage, akin to the one outlined in Mishnah Avot (Pirkei Avot 1:1), ensures fidelity across generations, as each link verifies the prior one's authenticity via public testimony and communal consensus rather than individual authority. The Rabbi contends that this continuity distinguishes Judaism, as alterations would have been detected and rejected by the masses, preserving doctrinal integrity without reliance on philosophical speculation.[6][21] Halevi devotes significant portions to refuting Karaite rejection of the oral law, portraying Karaism—a sect emerging in the 8th century CE under Anan ben David—as inconsistent and ahistorical. Karaites, who advocate scripture-only interpretation, inevitably devise their own customs (e.g., alternative calendar calculations or ritual practices) lacking the verified pedigree of rabbinic tradition, thus undermining their claim to purity. The Rabbi highlights that even Karaite founders drew selectively from oral sources before dissenting, and their innovations fail to achieve uniform observance, contrasting with the rabbinic system's tested efficacy over centuries. This critique underscores oral tradition's superiority, as it embodies collective wisdom refined through prophetic guidance and Sanhedrin adjudication, including enactments like the reading of Megillat Esther instituted post-Purim events in 473 BCE.[22][23][24] The essay further asserts the reliability of this tradition through its empirical testability: any deviation, such as false prophetic claims or legal innovations, invites immediate communal scrutiny and rejection, as evidenced by biblical precedents like the Deuteronomy 13 test for prophets (circa 1312 BCE). Halevi maintains that this mechanism sustains historical continuity, linking contemporary Jews to Sinaitic origins via documented successions and preserved texts like the Talmud, compiled between 200–500 CE. Unlike abstract philosophical systems, which lack verifiable origins, oral tradition's endurance amid exiles and persecutions—such as the Babylonian captivity from 586 BCE—affirms its divine provenance, as no fabricated system could maintain such coherence across millennia without collapse.[6][25]Fourth Essay: Divine Names and Linguistic Revelation

In the Fourth Essay of Kuzari, Yehuda Halevi, through the dialogue between the Rabbi and the Kuzari, examines the biblical names of God as expressions of divine attributes and actions, arguing that their Hebrew forms reveal profound insights into creation, governance, and prophetic influence. The essay begins with Elohim, interpreted as denoting the ruler or governor of the world, originally a plural form co-opted by ancient idolaters to describe astral deities or natural forces, yet signifying comprehensive dominion over existence.[26] Halevi contrasts this with the Tetragrammaton (YHWH), presented as God's proper, ineffable name unique to Israel, composed of consonants (yod, he, vav, he) that facilitate pronunciation and link directly to the revelation at Sinai via "Ehyeh asher ehyeh" (Exodus 3:14), emphasizing eternal self-existence and covenantal exclusivity.[26] Halevi further elucidates names like Adonai (Lord), which conveys divine sovereignty exercised through created intermediaries as tools of providence, and Shaddai (Almighty), denoting self-sufficiency and the bounding of chaotic forces in creation. These names, rooted in Hebrew etymology, are not mere labels but grammatical and semantic indicators of God's dynamic influence, from cosmic order (Elohim) to particularistic election (YHWH). The Rabbi asserts that such precision in nomenclature distinguishes Hebrew from other languages, which lack this alignment between word roots and metaphysical realities.[26] Central to the essay is the argument for Hebrew as the primordial "holy tongue" (lashon ha-kodesh), divinely imparted to Adam for naming creatures (Genesis 2:19), preserving uncorrupted essences post-Babel dispersion. Halevi posits that Hebrew's triconsonantal roots and phonetic structure enable words to mirror natural and divine principles, with letters like aleph symbolizing foundational unity and he evoking breath or revelation. This linguistic perfection facilitates angelic communication and prophetic vision, where divine influence permeates Israel through the names, enabling miracles and continuity of tradition.[26] Unlike speculative philosophies that abstract God beyond language, Halevi contends that Hebrew's revelatory capacity—evident in the names' historical efficacy—serves as empirical attestation of Judaism's divine origin, as non-Hebrew speakers cannot access this unmediated influence.[26] The Kuzari probes these ideas, questioning how names govern disparate realms, to which the Rabbi responds that they channel graduated divine action: general via Elohim, specific via YHWH and Adonai, culminating in Israel's elect status. Halevi thus frames linguistic revelation as integral to national prophecy, where Hebrew's sanctity ensures unaltered transmission of God's will, contrasting with corrupted tongues and affirming Judaism's unparalleled access to the divine.[26]Fifth Essay: Critique of Aristotelian Philosophy and Affirmation of Prophecy

In the fifth essay of the Kuzari, Yehuda Halevi transitions from earlier defenses of Judaism's historical and linguistic foundations to a pointed examination of speculative philosophy, particularly the Aristotelian tradition as adapted by Muslim thinkers such as al-Farabi and Avicenna. The Khazar king, having accepted the rabbi's arguments for revelation, now probes the limits of human reason in achieving proximity to God, asking whether the speculative intellect alone suffices for ultimate felicity. To address this, the rabbi summons a philosopher who outlines a rationalist worldview: the eternity of the cosmos as an emanation from necessary causes, the soul's ascent through syllogistic reasoning to conjunction with the active intellect, and ethics derived from natural law rather than divine command.[1] Halevi's critique, voiced through the rabbi, targets philosophy's foundational assumptions. He contends that Aristotelian causality, positing an infinite chain or uncaused prime mover, cannot rigorously prove creation ex nihilo, a doctrine essential to biblical theism, as it conflates potentiality with actuality and treats God as an impersonal necessity rather than a willful agent capable of miracles. The philosopher's abstract monotheism, reducing divine attributes to negative predicates, undermines the personal God of scripture who interacts historically and legislates specifically, rendering prophetic narratives—like the Sinai theophany—illusory or metaphorical. Halevi argues this rationalism leads to agnosticism on core truths, as human intellect remains passive and sense-bound, incapable of transcending material intermediaries without external divine influx.[27] Central to the essay's affirmation of prophecy is Halevi's distinction between intellectual contemplation and revelatory apprehension. Prophecy, he maintains, involves a holistic union of body and soul, facilitated by moral purification, isolation, and national election, culminating in sensory visions and auditory commands that convey unambiguous divine will. Unlike the philosopher's fleeting "taste" of the divine via logic, which yields no practical law or communal transformation, prophecy effects miracles, sustains tradition, and binds the Jewish people to the Shekhinah—God's indwelling presence—historically manifest in the Temple and land of Israel. This mode of knowledge, empirically rooted in mass-witnessed events, surpasses philosophy's probabilistic deductions, which falter on equivocations like the eternity-creation debate.[1] Halevi further dissects the philosopher's psychology, rejecting Avicennian models of the soul's immortality through intellect alone (as in Kuzari 5:12), insisting instead that true felicity requires prophetic preparation to receive "divine light" that illuminates first principles directly. He warns that overreliance on Greek syllogisms fosters heresy, as seen in mutakallimun excesses, and advocates a balanced approach: reason serves prophecy but cannot supplant it, preserving Judaism's particularism against universalist rationalism. The essay concludes by reinforcing that only through prophetic lineage and praxis can one approach God, not abstract speculation.[27]The Kuzari Principle: National Revelation as Empirical Proof

Historical Mass Witness Argument

The historical mass witness argument in the Kuzari centers on the claim that the divine revelation at Mount Sinai constituted a public event observed by the entire Israelite nation, thereby furnishing a robust basis for its historical veracity through collective testimony rather than isolated individual accounts. Rabbi Yehuda Halevi presents this in the dialogue between the Khazar king and the Jewish rabbi, where the rabbi asserts that Judaism originates not from a solitary prophet's private vision but from a mass auditory and visual experience involving the assembled people, who directly heard God's proclamation of the Ten Commandments amid thunder, lightning, and divine speech.[28] This national scale—traditionally enumerated as 600,000 adult males alongside women, children, and elders, totaling an estimated 2 to 3 million participants—creates an empirical anchor, as the event's details were imprinted on communal memory and transmitted intergenerationally without reliance on unverifiable personal authority.[2] Halevi contends that this mass witnessing inherently resists fabrication, as any contrived narrative of such a foundational occurrence would collapse under scrutiny from contemporaries or immediate descendants familiar with their forebears' lived experiences. If the story were invented centuries after the purported event, the originating generation could not impose it on a populace whose parents or grandparents would affirmatively deny participation in any comparable miracle, lacking inherited traditions or artifacts of the revelation.[29] The argument invokes the unbroken chain of Jewish historical continuity, wherein the event's recollection persists in ritual (e.g., the Shavuot commemoration) and textual records like the Torah, which explicitly challenges verification: "Ask now of the days past which were before you, since the day that God created man upon the earth... Has any people heard the voice of God speaking out of the midst of the fire, as you have heard, and lived?" (Deuteronomy 4:32–33).[30] This rhetorical appeal underscores the uniqueness of a verifiable public miracle, positioning it as causally improbable to forge en masse. The argument's historical dimension further emphasizes the persistence of this testimony across millennia, including during periods of exile and persecution, where no internal Jewish schisms successfully contested the Sinai event's occurrence despite theological disputes. Halevi contrasts this with pagan or prophetic traditions, which begin with singular intermediaries susceptible to doubt, arguing that only a genuine collective encounter could engender enduring national fealty to the law's divine origin.[28] Proponents maintain that archaeological or extra-biblical silence on the event does not negate the testimonial logic, as the argument prioritizes the internal coherence of transmitted national memory over external corroboration.[29]Causal Impossibility of Fabrication

The causal impossibility of fabricating a national revelation, as articulated in Rabbi Yehuda Halevi's Kuzari (completed circa 1140 CE), rests on the premise that such an event involves direct experiential knowledge by an entire population, precluding invention through deception or gradual myth-making. Halevi posits that if the Sinai revelation had not occurred, no prophet or group could successfully propagate the claim among contemporaries, as the purported witnesses—comprising hundreds of thousands—would immediately reject any assertion of collective auditory and visual phenomena they did not perceive. This initial barrier ensures that false traditions lack a viable causal mechanism for inception, since familial and communal verification would expose the absence of shared memory.[31] Transmission across generations amplifies this impossibility: parental testimony to children relies on the parents' own or inherited certainty from eyewitness forebears, forming an unbroken chain that collapses without foundational reality. Halevi illustrates this via the hypothetical Khazar king's inquiry, contrasting Judaism's mass event with religions founded on private visions, which can originate from individual claims untestable by the public. Fabrication would require coercing or deluding an entire nation into affirming non-events, defying human psychology and social dynamics, as skeptics within the group—inevitably present—would challenge the narrative based on lived absence of corroboration. Analyses of Halevi's argument emphasize that this causal hurdle explains why no comparable mass-revelation claims persist in other traditions, as invented stories erode under scrutiny from non-participants.[28][2] Empirical parallels, such as failed attempts to impose fabricated histories on populations (e.g., certain 20th-century ideological myths rejected by direct survivors' descendants), underscore the argument's realism, though Halevi grounds it in first-hand collective testimony's unforgeable nature rather than modern historiography. Critics, including some medieval philosophers like Maimonides, implicitly engage this by prioritizing rational proofs over revelatory uniqueness, but Halevi counters that mass events provide superior epistemic warrant due to their resistance to contrivance. This principle thus posits not mere historical anomaly but a causal filter: only veridical national experiences can sustain enduring belief without evidentiary voids.[1]Comparisons to Private Revelations in Other Religions

The Kuzari principle highlights the empirical robustness of Judaism's foundational revelation at Sinai, witnessed by an estimated 600,000 adult males and their families according to biblical accounts, as a collective national experience transmitted unbroken through generations, rendering fabrication implausible due to the absence of verifiable counter-evidence in Jewish tradition.[2] This stands in contrast to private revelations in other faiths, where divine communications or miracles are typically reported by individuals or small groups, susceptible to doubt over authenticity since they lack widespread contemporaneous corroboration and could theoretically arise from deception, delusion, or exaggeration without immediate communal disproof.[2] Halevi argues that such private claims, while potentially sincere, fail to compel universal assent in the manner of a mass event, as skeptics can always invoke alternative naturalistic explanations unrefuted by absent witnesses.[32] In Christianity, pivotal miracles like the virgin birth of Jesus and his resurrection are depicted in the New Testament as observed by limited audiences—Mary and Joseph for the former, and initially a handful of disciples for the latter—rather than an entire populace, permitting critiques that these could have been fabricated narratives spread post-event without the evidentiary barrier of national memory.[2] Halevi contends that even if such miracles occurred, they do not inherently validate superseding the Mosaic law, as biblical criteria for prophecy (Deuteronomy 13:2-6) require alignment with prior revelation, a test private Christian claims fail by introducing doctrinal innovations like the Trinity absent from Sinai's public tenets.[2] Notably, Christian traditions affirm the historicity of Sinai from the Hebrew Bible yet prioritize Jesus' personal authority, underscoring the Kuzari's point that private prophetic assertions depend on deferred faith rather than immediate collective verification.[33] Islam's origins similarly rest on Muhammad's private revelations, commencing in 610 CE in the seclusion of the Hira cave near Mecca, where he alone encountered the angel Gabriel delivering the Quran's initial verses, with subsequent suras received in isolation or to small circles, devoid of a Sinai-scale public theophany to anchor the community's belief.[2] Halevi critiques this as reliant on one man's testimony, bolstered by later miracles like the Quran's linguistic inimitability or the night journey (Isra and Mi'raj), which were not mass-witnessed but accepted through personal conviction and military successes, contrasting sharply with Judaism's non-proselytizing, memory-based proof.[34] Islamic doctrine acknowledges the Torah's Sinai event as prophetic history yet posits Muhammad's message as corrective, a progression Halevi deems unconvincing absent equivalent empirical grounding, as private origins invite perpetual scrutiny over potential human invention.[33] These comparisons extend to post-biblical movements like Mormonism, where Joseph Smith's 1820 vision of God and Jesus, followed by angelic deliverances of golden plates in 1827, were solitary experiences shared via testimony rather than national spectacle, mirroring the pattern of founder-centric revelations that Kuzari proponents argue cannot rival Sinai's causal improbability of collective invention.[2] Across these faiths, the shift from public to private epistemologies reflects a vulnerability to historical revisionism, as small-witness events permit doctrinal evolution without the inertial force of unbroken societal attestation, a dynamic Halevi leverages to affirm Judaism's unique evidential privilege.[32]Reception and Influence

Medieval and Kabbalistic Interpretations

Nachmanides (Ramban, 1194–1270), a pivotal medieval Jewish scholar and early kabbalist, frequently cited Yehuda Halevi's Kuzari in his writings, integrating its arguments on divine influence and prophecy into his own theological framework.[24] Although the Kuzari was not the dominant source for Nachmanides's thought, Halevi's conception of God's direct interaction with the world contributed to Nachmanides's views on the soul's ascent and the mechanics of divine providence.[35] In Kabbalistic circles, the Kuzari's esoteric allusions—particularly in its treatment of sacrificial rites as mechanisms for channeling divine overflow—were expanded upon by early kabbalists in Provence and Catalonia during the 13th century. Halevi provided an exoteric rationalization of sacrifices as symbolic accommodations to human weakness while hinting at deeper, non-rational purposes involving theurgic effects on upper realms, which kabbalists like Nachmanides interpreted through the lens of sefirotic structures to explain how rituals unify fragmented divine potencies.[35] This integration positioned the Kuzari as a bridge between philosophical critique and mystical praxis, with Halevi's ideas on human actions influencing celestial spheres prefiguring kabbalistic notions of theurgy, wherein earthly deeds actively shape the Godhead.[36] Later medieval kabbalists reinterpreted the Kuzari using established esoteric paradigms, such as applying sefirotic categories to Halevi's discussions of prophecy and national election, thereby reinforcing the text's emphasis on experiential revelation over abstract philosophy. Nachmanides's students and successors traced elements of the Kuzari's commentary on Sefer Yetzirah (e.g., in Kuzari 4:25) directly into kabbalistic exegesis of creation and linguistic mysticism, viewing Halevi's rejection of Aristotelian intermediaries as aligning with the doctrine of tzimtzum (divine contraction).[35] These interpretations sustained the Kuzari's relevance amid rising Maimonidean rationalism, prioritizing its causal realism in divine-human relations over purely speculative metaphysics.[37]Early Modern and Haskalah Engagements

In the early modern period, the Kuzari experienced renewed dissemination through print and scholarly engagement, particularly in Europe. Following medieval manuscripts, printed editions emerged, with the first Hebrew printing occurring in Constantinople around 1506, facilitating wider access among Jewish communities. In Renaissance Italy, the work received positive reception within a Platonist-humanist milieu, where it was cited as an authoritative text by Jewish scholars from the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries, often invoked to support defenses of Judaism against Christian polemics.[38][39] Christian Hebraists also contributed to its study, most notably through Johann Buxtorf the Younger's 1660 Latin translation, Liber Cosri, published in Basel. This edition included the Hebrew text alongside Buxtorf's translation and notes, marking the first Latin rendering and serving as a key resource for European scholars interested in Jewish philosophy. Buxtorf, a prominent Hebraist at the University of Basel, aimed to elucidate medieval Jewish thought for Christian audiences, though his work reflected the era's scholarly curiosity rather than theological endorsement.[40][41] During the Haskalah, the Jewish Enlightenment of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, engagements with the Kuzari were marked by reinterpretation amid tensions between its anti-rationalist stance and the movement's emphasis on reason and compatibility with secular knowledge. Maskilim, influenced by figures like Moses Mendelssohn who favored Maimonides' rationalism, often viewed Halevi's rejection of Aristotelian philosophy skeptically, yet selectively appropriated the Kuzari's arguments for Jewish particularity to counter assimilationist pressures and affirm cultural uniqueness during emancipation debates. Adam Shear notes that early Haskalah thinkers reimagined the text to align with Enlightenment ideals, transforming its medieval apologetic into a tool for modern Jewish identity formation.[41][42] This period saw the Kuzari invoked in broader intellectual discourses, including precursors to Wissenschaft des Judentums, where scholars like Moritz Steinschneider began cataloging and analyzing medieval works, though full critical reception intensified post-1840. Despite its limited centrality compared to rationalist texts, the Kuzari's emphasis on national revelation and experiential proof resonated in Haskalah-era apologetics against deism and skepticism, influencing responses to Christian Hebraism and internal reformist critiques.[43][44]Modern Revival in Religious Zionism and Apologetics

In the twentieth century, the Kuzari's central argument—subsequently termed the Kuzari principle—gained prominence in Jewish apologetics as a defense against secular skepticism and alternative religious claims, positing that the Sinai revelation's national scale renders fabrication causally implausible due to the absence of contemporary refutation or transmission failure across generations.[2] This principle asserts that private revelations, unlike the publicly witnessed event described in Exodus, lack the evidentiary chain of mass testimony preserved in Jewish tradition, making Judaism uniquely verifiable.[29] Outreach organizations such as Ohr Somayach and Aish HaTorah, founded in the 1970s amid the baal teshuva movement, integrated the argument into rationalist presentations aimed at educated seekers, with rabbis like Lawrence Kelemen employing it to argue that no comparable national origin myth exists without historical discontinuity.[2] [18] The principle's revival extended to countering modern biblical criticism, which questions the Pentateuch's antiquity; apologists maintain that the unbroken oral and written transmission of the Sinai event, corroborated by archaeological and textual evidence of early Israelite monotheism, aligns with Halevi's logic of empirical tradition over isolated prophecy.[45] By the late twentieth century, it appeared in works like Rabbi Dovid Gottlieb's Living Up to the Truth (1989), framing Judaism's truth claims as epistemically superior to those reliant on singular miracles or philosophical deduction.[29] Within Religious Zionism, emerging post-1967 Six-Day War as a synthesis of Orthodox Judaism and nationalism, the Kuzari's emphasis on the Jewish people's divine election and the land's indispensable role resonated with interpretations of statehood as redemptive continuity from ancient revelation.[1] Thinkers in this stream, influenced by Halevi's own attempted aliyah and poetic Zionism, invoked the text to theologically ground settlement and sovereignty, viewing the ingathering of exiles since 1948 as empirical fulfillment of the national covenant Halevi defended.[18] Yeshivot like Machon Meir, oriented toward Religious Zionist education for olim, incorporate Kuzari studies to link historical testimony with contemporary return to Zion, reinforcing causal realism in prophetic realization over assimilationist alternatives.[24] This adaptation counters diaspora-centric Orthodoxy by prioritizing geographic and collective dimensions of revelation.Criticisms and Scholarly Debates

Charges of Ethnocentrism and Supremacism

Critics of Judah Halevi's Kuzari have charged it with ethnocentrism for privileging the Jewish people's collective historical experience—particularly the mass revelation at Mount Sinai—as uniquely verifiable proof of divine truth, while dismissing private revelations in Christianity and Islam as potentially fabricated.[46] This framework, they argue, elevates Judaism not merely as true but as epistemologically superior due to its national transmission across generations, fostering an inward-looking particularism that resists universal philosophical standards.[47] Halevi's doctrine of the "divine influence" (amr ilahi), an intermediary force linking God to the Jewish people and inherited through lineage, has drawn accusations of biological essentialism akin to racial theorizing, as interpreted by mid-20th-century scholar Cedric Dover, who positioned Halevi alongside Islamicate thinkers in positing religion as racially determined.[48] Dover contended that Halevi's views imply a hereditary spiritual superiority for Jews, enabling traits like prophecy and moral resilience, which modern critics equate with supremacist ideology by linking identity to immutable group qualities rather than individual merit or reason.[49] Such charges often arise in contemporary academic contexts influenced by postcolonial and critical race frameworks, where Halevi's rejection of rationalist universalism—favoring empirical tradition over speculative philosophy—is reframed as exclusionary tribalism that devalues non-Jewish civilizations.[48] Secular Jewish thinkers, in particular, have critiqued the Kuzari's ethnocentric core as incompatible with egalitarian pluralism, viewing its affirmation of chosenness as a theological justification for cultural insularity that echoes supremacist rhetoric when applied to national identity.[50] These interpretations, however, frequently apply anachronistic lenses to a 12th-century text, overlooking Halevi's intent to defend Judaism amid Andalusian assimilation pressures rather than advocate domination.[51]Critiques of Anti-Rationalism and Fideism

Critics of Yehuda Halevi's Kuzari have argued that its prioritization of national revelation and prophetic intuition over philosophical demonstration fosters fideism, whereby faith in tradition supplants rigorous rational inquiry into foundational beliefs.[52] This perspective contrasts sharply with Moses Maimonides' approach in the Guide for the Perplexed, which integrates Aristotelian logic to establish God's existence and the rationality of divine law through demonstrable proofs accessible to intellect, rather than relying on historical events purportedly witnessed by a collective. Maimonidean rationalists contended that Halevi's dismissal of universal metaphysical reasoning in favor of a particularist "Jewish faculty" for prophecy risks rendering religious truth arbitrary and unverifiable, dependent on ethnic inheritance rather than logical necessity.[53] In the Haskalah era, Enlightenment-oriented Jewish thinkers further critiqued the Kuzari as emblematic of anti-rationalism, viewing its defense of rabbinic authority through skeptical attacks on philosophy as obstructive to intellectual progress and assimilation into modern science.[43] Adam Shear documents how maskilim in the 18th and 19th centuries rejected Halevi's fideistic skepticism—modeled partly on al-Ghazali's critique of causality—as promoting dogmatic suspension of critical doubt in favor of unexamined tradition, thereby associating Judaism with superstition amid rising empiricism.[43] Such objections highlighted that Halevi's moderate fideism, which concedes reason's limits in metaphysics while elevating revelation, ultimately privileges arational belief over empirical or logical validation, potentially insulating doctrines from falsification.[52] Modern scholarly analyses, such as those by Ehud Krinis, acknowledge Halevi's use of skeptical motifs to counter dogmatic rationalism but note critiques that this strategy veers toward fideistic evasion, where doubt about reason's scope serves to entrench non-rational commitments without alternative evidential standards.[54] Rationalist interpreters argue this undermines Judaism's compatibility with scientific method, as the Kuzari's empirical claim for Sinai revelation presupposes the very testimonial chain it seeks to prove, circularly bypassing independent rational scrutiny.[1] These critiques persist in philosophical debates, positing that true religious epistemology demands harmony between faith and reason, not the subordination of the latter to historical fiat.[55]Challenges to the Kuzari Principle's Logical Validity

Critics contend that the Kuzari principle exhibits circularity, as it presupposes the accuracy of the national tradition it seeks to validate; the claim of mass revelation at Sinai relies on the very oral and textual transmission whose veracity the argument aims to establish, without independent corroboration.[56] This reasoning assumes the tradition's fidelity to demonstrate the event's historicity, rendering the proof question-begging rather than demonstrative.[57] A further logical challenge arises from counterexamples of enduring national traditions attributing public, miraculous events to ancestors, undermining the principle's assertion of unique improbability for fabrication. For instance, the Lotus Sutra in Mahayana Buddhism recounts the Buddha's revelation to an assembly of hundreds of thousands of monks, deities, and beings, including levitations and other sensory phenomena, transmitted as a collective foundational experience across generations without widespread contemporary denial.[58][59] Similarly, ancient myths such as the Theban Greeks' belief in their divine origins from Cadmus and the sown men persist as national lore despite lacking historical basis, illustrating how communal identities can sustain unverifiable public-event narratives.[28] These cases suggest that mass traditions of extraordinary events are not logically precluded from arising through cultural consolidation, even absent direct witnesses. The principle also faces objection for conflating psychological improbability with logical impossibility, committing an argument from incredulity; while fabricating a false mass revelation may be sociologically difficult, it does not entail contradiction or entailment of truth, as traditions can evolve via embellishment, conflation of smaller events, or sincere collective misattribution over time.[29] Scholars note that applying deductive logic to complex cultural transmission overlooks empirical patterns of myth formation, where small kernels of experience expand into national epics without violating transmissibility constraints.[45] For example, biblical source criticism posits the Sinai narrative as a composite from disparate traditions, potentially amplifying a localized theophany into a panoramic event, which aligns with known mechanisms of oral historiography rather than requiring wholesale invention from nothingness.[45] Additionally, the argument employs asymmetrical standards, demanding unattainable fabrication for Judaism while permitting naturalistic explanations for analogous claims elsewhere, such as the gradual legend-building in other foundational religions.[56] This selective rigor fails to establish the principle's universal validity, as it does not preclude the possibility that the Jewish tradition, like others, reflects a sincere but distorted ancestral memory rather than verbatim historical fidelity. Proponents of revised formulations acknowledge these limits, proposing probabilistic rather than absolute evidential weight, but critics maintain that the original logical claim remains undermined by its vulnerability to empirical disconfirmation and incomplete causal accounting.[29][60]Textual History and Scholarship

Major Translations and Editions

The Kuzari, originally composed in Judeo-Arabic by Yehuda Halevi around 1140 CE, was first translated into Hebrew by Judah ibn Tibbon in 1167 CE, rendering it accessible to Jewish scholars in Europe and forming the basis for subsequent commentaries and standard editions.[61] This Hebrew version circulated in manuscripts until the first printed edition appeared in Fano, Italy, in 1506, commissioned by the ibn Yahya brothers David, Meir, and Shlomo.[62] Early modern editions included a Latin translation by Johannes Buxtorf the Younger, published in Basel in 1660, which provided the text to Christian Hebraists alongside the Hebrew of ibn Tibbon, accompanied by Buxtorf's introduction and notes.[40] In 1887, Hartwig Hirschfeld edited the first printed version of the original Judeo-Arabic text, paired with ibn Tibbon's Hebrew translation, based on a Bodleian manuscript.[61] The seminal English translation from the Arabic original was produced by Hartwig Hirschfeld in 1905, offering a scholarly rendering that remained standard for decades.[63] Modern Hebrew editions include Yehuda Even Shmuel's readable version with notes in 1973, Yosef Kafih's parallel Arabic-Hebrew text in 1997, and Michael Schwarz's precise modern Hebrew translation in 2017, featuring extensive annotations.[61] Significant English editions post-Hirschfeld encompass Daniel Korobkin's annotated translation, The Kuzari: In Defense of the Despised Faith, first published in 1998 as the initial new English version in nearly a century, drawing on medieval commentaries.[11] Contemporary bilingual Hebrew-English editions, such as those by Feldheim Publishers (2009), incorporate updated translations faithful to recent Hebrew interpretations like Ha-Kuzari Ha-Meforash.[64]| Year | Language | Translator/Editor | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1167 | Hebrew | Judah ibn Tibbon | First translation from Judeo-Arabic; standard medieval text.[61] |

| 1506 | Hebrew | Printed edition (Fano) | Initial print run, commissioned by ibn Yahya family.[62] |

| 1660 | Latin | Johannes Buxtorf the Younger | Bilingual Hebrew-Latin; aimed at European scholars.[40] |

| 1887 | Judeo-Arabic/Hebrew | Hartwig Hirschfeld | First Arabic print with Hebrew parallel.[61] |

| 1905 | English | Hartwig Hirschfeld | Scholarly translation from Arabic.[63] |

| 1998 | English | Daniel Korobkin | Annotated, based on classic commentaries.[11] |

| 2017 | Modern Hebrew | Michael Schwarz | Readable with glossary and notes.[61] |

Key Commentaries and Recent Studies

One notable medieval commentary is Heshek Shelomo by Solomon ben Judah of Lunel, a 14th-century Provençal scholar, which provides detailed exegesis on Halevi's arguments and has been the subject of a modern annotated critical edition published by Bar-Ilan University Press.[65] In the 20th century, Rabbi Shlomo Aviner produced a four-volume commentary emphasizing the Kuzari's role in religious apologetics and its relevance to contemporary Jewish faith.[66] Recent scholarship has examined the Kuzari's influence on early Kabbalah, with a 2023 study in the Harvard Theological Review analyzing Halevi's rationale for the sacrificial rite—centered on its role in divine-human communion—and demonstrating its integration into kabbalistic interpretations of ritual secrets, rather than mere replication.[35] Another line of inquiry addresses the historical Khazar motif in the text, as explored in a Brill publication tracing how Halevi's narrative framework contributed to the enduring myth of Jewish Khazar origins, potentially drawing from limited medieval sources on the conversion.[67] A 2016 analysis in peer-reviewed literature evaluates the Kuzari's compatibility with scientific inquiry, arguing that Halevi's critique of Aristotelian rationalism anticipates tensions between empirical science and revealed religion without rejecting reason outright.[68] In 2025, researchers identified annotations on a 1547 Venice edition of the Kuzari as attributable to Azariah de' Rossi, the 16th-century Italian-Jewish historian, offering new insights into Renaissance-era textual engagement and de' Rossi's selective critique of Halevi's historical claims.[69] These studies underscore ongoing debates about the Kuzari's philosophical premises, prioritizing textual evidence over unsubstantiated traditional narratives.References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Kitab_al_Khazari/Part_Two

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Kitab_al_Khazari/Part_Four