Recent from talks

Surveying and City Planning Timeline

Clockmaking Timeline

Almanac Publication and Advocacy Timeline

Early Life and Education Timeline

Mathematical Achievements Timeline

Personal Life and Relationships Timeline

Later Years and Legacy Timeline

Astronomy and Scientific Pursuits Timeline

Social and Political Context Timeline

Main milestones

Farm Life and Agricultural Interests Timeline

Nothing was collected or created yet.

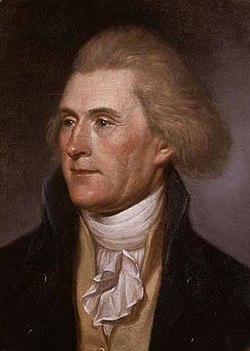

Benjamin Banneker

View on WikipediaThis article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: overly detailed quotes in references. (August 2023) |

Benjamin Banneker (November 9, 1731 – October 19, 1806) was an American naturalist, mathematician, astronomer and almanac author. A landowner, he also worked as a surveyor and farmer.

Key Information

Born in Baltimore County, Maryland, to a free African-American mother and a father who had formerly been enslaved, Banneker had little or no formal education and was largely self-taught. He became known for assisting Major Andrew Ellicott in a survey that established the original borders of the District of Columbia, the federal capital district of the United States.

Banneker's knowledge of astronomy helped him author a commercially successful series of almanacs. He corresponded with Thomas Jefferson on the topics of slavery and racial equality. Abolitionists and advocates of racial equality promoted and praised Banneker's works. Although a fire on the day of Banneker's funeral destroyed many of his papers and belongings, one of his journals and several of his remaining artifacts survived.

Banneker became a folk-hero after his death, leading to many accounts of his life being exaggerated or embellished.[2][3] The names of parks, schools and streets commemorate him and his works, as do other tributes.

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Banneker was born on November 9, 1731, in Baltimore County, Maryland, to Mary Banneky, a free black woman, and Robert, a freed slave from Guinea who died in 1759.[4][5]

There are two conflicting accounts of Banneker's family history. Banneker himself and his earliest biographers described him as having only African ancestry.[6][7][8] None of Banneker's surviving papers describe a white ancestor or identify the name of his grandmother.[7] However, two lines of later research both suggest that Banneker's mother was the daughter of a white woman and an African slave,[5][7][9][10]: 4 although they differ as to whether the Banneker surname came from his mother or father and the origin of the name, which could be from Banaka, a small village in the present-day Klay District of Bomi County in northwestern Liberia that had once participated in the African slave trade[5][11] or "Banaka", the home of the Vai people, who have lived there since about 1500 when they left the Mali Empire.[12]

In 1737, when he was 6, Banneker was named on the deed of his family's 100-acre (0.40 km2) farm in the Patapsco Valley in rural Baltimore County.[13][14][15][16]

In 1791, a letter writer stated that Banneker's parents had sent him to an obscure school where he learned reading, writing and arithmetic as far as double position.[clarification needed][17] In contrast, unverified accounts, first appeared in books published more than 140 years after Banneker's death suggest that, as a young teenager, Banneker met and befriended Peter Heinrich, a Quaker who later established a school near the Banneker family farm.[18][19] These accounts state that Heinrich shared his personal library and provided Banneker with his only classroom instruction.[19][20] Banneker's formal education (if any) presumably ended when he was old enough to help on his family's farm.[21]

Notable works

[edit]Around 1753, at about the age of 21, Banneker reportedly completed a wooden clock that struck on the hour. He appears to have modelled his clock from a borrowed pocket watch by carving each piece to scale. The clock continued to work until his death.[21][22]

After his father died in 1759, Banneker lived with his mother and sisters.[4][10] Records indicate that in 1768 and 1773, he was living in Baltimore.[23][24]

In 1772, brothers Andrew Ellicott, John Ellicott and Joseph Ellicott moved from Bucks County, Pennsylvania, and bought land along the Patapsco Falls near Banneker's farm on which to construct gristmills, around which the village of Ellicott's Mills (now Ellicott City) subsequently developed.[25][26][27][28] The Ellicotts were Quakers who held the same views on racial equality as did many of their faith.[25][29] Banneker studied the mills and became acquainted with their proprietors.[30][10] In 1788, George Ellicott, a son of Andrew Ellicott, loaned Banneker books and equipment to begin a more formal study of astronomy.[31][32][33] During the following year, Banneker sent George his work calculating a solar eclipse.[31][32][30]

In 1790, Banneker prepared an ephemeris for 1791, which he hoped would be placed within a published almanac.[34] However, he was unable to find a printer that was willing to publish and distribute the work.[31][35]

Survey of the original boundaries of the District of Columbia

[edit]

In early 1791, U.S. Secretary of State, Thomas Jefferson, asked surveyor Maj. Andrew Ellicott to survey an area for a new federal district. In February 1791, Ellicott left a survey in western New York to begin the district survey and hired Banneker to assist him, advancing him $60 for travel expenses to, and at, Georgetown.[36][37]

The territory that became the original District of Columbia was formed from land along the Potomac River ceded by the states of Maryland and Virginia to the federal government (see: Founding of Washington, D.C.).[36][37][38] a square to measure 10 miles (16 km) on each side, totaling 100 square miles (260 km2). Ellicott's team placed boundary marker stones at or near every mile point along the borders of the new capital territory.[36][37]

Banneker's role in the survey isn't entirely certain. Some biographers have stated that Banneker's duties consisted primarily of making astronomical observations and calculations to establish base points, including one at Jones Point in Alexandria, Virginia, where the survey started and where the south corner stone was to be located.[36][39] They have also stated that Banneker maintained a clock that he used to relate points on the ground to the positions of stars at specific times.[31][13]

However, there is little documentation to confirm Banneker's role[40][41] and a news report covering the April 15 dedication ceremony for the first boundary stone (the south corner stone) credits Andrew Ellicott with "ascertain[ing] the precise point from which the first line of the district was to proceed" [42] and did not mention Banneker.[43]

Banneker left the boundary survey in April 1791 due to other commitments, particularly the calculation of an ephemeris for the year of 1792.[44][45] The arrival of spring also required him to direct more attention to his farm than was needed during the winter.[45] Banneker, therefore, returned to his home near Ellicott's Mills.[31][45]

Andrew Ellicott's two younger brothers, who usually assisted him, had completed the New York survey about the same time and were able to join the survey of the federal district.[45] The surveying team laid the remaining Virginia marker stones in 1791, laying the Maryland stones and completed the boundary survey in 1792.[36][37][46]

Banneker's almanacs

[edit]After returning to Ellicott's Mills, Banneker made astronomical calculations that predicted eclipses and planetary conjunctions for inclusion in an almanac and ephemeris for the year of 1792.[4][35][29] To aid Banneker in his efforts to have his almanac published, Andrew Ellicott (who had been authoring almanacs and ephemerides of his own since 1780)[47] forwarded Banneker's ephemeris to James Pemberton, the president of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage.[31][35][13]

Pemberton then asked William Waring, a Philadelphia mathematician and ephemeris calculator,[48] and David Rittenhouse, a prominent American astronomer, almanac author,[49] surveyor and scientific instrument maker who was at the time serving as the president of the American Philosophical Society,[50] to confirm the accuracy of Banneker's work.[35][13] Waring endorsed Banneker's work, stating, "I have examined Benjamin Banneker's Almanac for 1792, and am of the Opinion that it well deserves the Acceptance and Encouragement of the Public."[13]

Rittenhouse responded to Pemberton by stating that Banneker's ephemeris "was a very extraordinary performance, considering the Colour of the Author" and that he "had no doubt that the Calculations are sufficiently accurate for the purposes of a common Almanac. .... Every instance of Genius amongst the Negroes is worthy of attention, because their suppressors seem to lay great stress on their supposed inferior mental abilities."[13] A biographer wrote that Banneker replied to Rittenhouse's endorsement by stating: "I am annoyed to find that the subject of my race is so much stressed. The work is either correct or it is not. In this case, I believe it to be perfect."[51]

Pemberton then made arrangements for Joseph Crukshank (a Philadelphia Quaker who was a founder of the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery and who had since 1770 been publishing almanacs, including at least one that Waring had calculated) to print Banneker's almanac.[31][52] Having thus secured the support of Pemberton, Rittenhouse and Waring, Banneker delivered a manuscript containing his ephemeris to William Goddard, a Baltimore printer who had published The Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia Almanack and Ephemeris for every year since 1782.[53] Goddard then agreed to print and distribute Banneker's work within an almanac and ephemeris for the year of 1792.[13]

Banneker's Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia Almanack and Ephemeris, for the Year of our Lord, 1792 was the first in a six-year series of almanacs and ephemerides that printers agreed to publish and sell.[31][35] At least 28 editions of the almanacs, some of which appeared during the same year, were printed in seven cities in five states: Baltimore; Philadelphia; Wilmington, Delaware; Alexandria, Virginia; Petersburg, Virginia; Richmond, Virginia; and Trenton, New Jersey.[31][54][55]

The title pages of the Baltimore editions of Banneker's 1792, 1793 and 1794 almanacs and ephemerides stated that the publications contained:

the Motions of the Sun and Moon, the True Places and Aspects of the Planets, the Rising and Setting of the Sun, Place and Age of the Moon, &c. – The Lunations, Conjunctions, Eclipses, Judgment of the Weather, Festivals, and other remarkable Days; Days for holding the Supreme and Circuit Courts of the United States, as also the useful Courts in Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia. Also – several useful Tables, and valuable Receipts. – Various Selections from the Commonplace–Book of the Kentucky Philosopher, an American Sage; with interesting and entertaining Essays, in Prose and Verse –the whole comprising a greater, more pleasing, and useful Variety than any Work of the Kind and Price in North America.[56][57]

In addition to the information that its title page described, the 1792 almanac contained a tide table listing the methods for calculating the time of high water at four locations along the Chesapeake Bay (Cape Charles and Point Lookout, Virginia; Annapolis and Baltimore, Maryland).[59] Later almanacs contained tables for making such calculations for those locations as well as for Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Halifax, Quebec, Hatteras, Nantucket and other places.[60] Monthly tables in each edition listed astronomical data and weather predictions for each of the months' dates.[61]

A Philadelphia edition of Banneker's 1795 almanac contained a lengthy account of a yellow fever epidemic that had struck that city in 1793. Written by a committee whose president was the city's mayor, Matthew Clarkson, the account related the presumed origins and causes of the epidemic, as well as the extent and duration of the event.[62]

The title pages of two Baltimore editions of Banneker's 1795 almanac had woodcut portraits of him as he may have appeared.[58][63] However, a biographer later concluded that the portraits were more likely portrayals of an idealized African-American youth.[64]

A Baltimore edition of Banneker's 1796 almanac contained a table enumerating the population of each U.S. state and the Southwest Territory as recorded in the 1790 United States census. The table listed the number of free persons and slaves in each state and the territory according to race and gender, as well as to whether they were above or below the age of 16 years. The table also listed the number of members of the U.S. House of Representatives that each state had during the almanac's year.[65]

The almanacs' editors prefaced the publications with adulatory references to Banneker and his race.[35][66] Editions of Banneker's 1792 and 1793 almanacs contained full or abridged copies of a lengthy commendatory letter that James McHenry,[67] the Secretary of the 1787 United States Constitutional Convention and self-described friend of Banneker, had written to Goddard and his partner, James Angell, in August 1791 to support the almanac's publication.[68]

As first published in Banneker's 1792 almanac and later given an increased circulation when re-published in Philadelphia within The American Museum, or Universal Magazine, McHenry's full letter began:

Benjamin Banneker, a free Negro, has calculated an Almanack, for the ensuing year, 1792, which being desirous to dispose of, to the best advantage, he has requested me to aid his application to you for that purpose. Having fully satisfied myself, in respect to his title to this type of authorship, if you can agree to him for the price of his work, I may venture to assure you it will do you credit, as Editors, while it will afford you the opportunity to encourage talents that have thus far surmounted the most discouraging circumstances and prejudices."[69]

In their preface to Banneker's 1792 almanac, the editors of the work wrote that they:

feel themselves gratified in the Opportunity of presenting to the Public, through the Medium of their Press, what must be considered as an extraordinary Effort of Genius — a complete and accurate EPHEMERIS for the Year 1792, calculated by a sable Descendant of Africa, .... — They flatter themselves that a philanthropic Public, in this enlightened Era, will be induced to give their Patronage and Support to this Work, not only on Account of its intrinsic Merit, (it having met the Approbation of several of the most distinguished Astronomers in America, particularly the celebrated Mr. Rittenhouse) but from similar Motives to those which induced the Editors to give this Calculation the Preference, the ardent desire of drawing modest Merit from Obscurity, and controverting the long-established illiberal Prejudice against the Blacks.[70]

After Goddard and Angell had published their 1792 Baltimore edition of the almanac, Angell wrote in the 1793 edition (which he alone edited) that abolitionists William Pitt, Charles James Fox and William Wilberforce had introduced the 1792 edition into the British House of Commons to aid their effort to end the British slave trade in Africa.[71][72] However, the British Parliament's report of the debate that accompanied this effort did not mention either Banneker or his almanac.[73]

Supported by Andrew, George and Elias Ellicott and heavily promoted by the Maryland and Pennsylvania abolition societies, the early editions of the almanacs achieved commercial success.[74] Printers then distributed at least nine editions of Banneker's 1795 almanac.[75] A Wilmington, Delaware, printer issued five editions for distribution by different vendors. Printers in Baltimore issued three versions of the almanac, while three Philadelphia printers also sold editions. A Trenton, New Jersey, printer additionally sold a version of the work.[76][77]

Banneker's journals

[edit]

Banneker kept a series of journals that contained his notebooks for astronomical observations, his diary and accounts of his dreams.[31][78] The journals additionally contained a number of mathematical calculations and puzzles.[31][78][79]

On the day of his funeral, a fire destroyed all but one of which Banneker's journals.

The surviving journal described in April 1800 Banneker's recollections of the 1749, 1766 and 1783 emergences of Brood X of the seventeen-year periodical cicada (Magicicada septendecim and related species)[80][81] and described an effect that the pathogenic fungus, Massospora cicadina, has on its host.[80][81][82] The journal also recorded Banneker's observations on the hives and behavior of honey bees.[80][83]

Political views

[edit]Banneker's 1792 almanac contained an extract from an anonymous essay entitled "On Negro Slavery, and the Slave Trade" that the Columbian Magazine had published in 1790.[84] After quoting a statement that David Rittenhouse had made (that Negroes "have been doomed to endless slavery by us — merely because their bodies have been disposed to reflect or absorb the rays of light in a way different from ours"), the extract concluded:

The time, it is hoped is not very remote, when those ill-fated people, dwelling in this land of freedom, shall commence a participation with the white inhabitants, in the blessings of liberty; and experience the kindly protection of government, for the essential rights of human nature.[85]

A Philadelphia edition of Banneker's 1793 almanac that Joseph Crukshank published contained copies of pleas for peace that the English anti-slavery poet William Cowper and others had authored,[86] as well as anti-slavery speeches and writings from England and America. The latter included extracts from speeches that William Pitt, Matthew Montagu and Charles James Fox had given to the British House of Commons in 1792 during the debate on a motion for the abolition of the British slave trade,[87] an extract from a 1789 poem by an English Quaker, Thomas Wilkinson,[88] and an extract from a query in Thomas Jefferson's 1787 Notes on the State of Virginia.[89][29]

Crukshank's edition of Banneker's 1793 almanac also contained a copy of "A Plan of a Peace-Office, for the United States".[90] Although the almanac did not identify the Plan's author, writers later attributed the work to Dr. Benjamin Rush, a signer of the 1776 Declaration of Independence.[91]

The Plan proposed the appointment of a "Secretary of Peace", described the Secretary's powers and advocated federal support and promotion of the Christian religion.[92]

Correspondence with Thomas Jefferson

[edit]

On August 19, 1791, after departing the federal capital area, Banneker wrote a letter to Thomas Jefferson, who in 1776 had drafted the United States Declaration of Independence and in 1791 was serving as United States Secretary of State.[93][94] Quoting language in the Declaration, the letter expressed a plea for justice for African Americans.

To support his plea, Banneker included within his letter a handwritten manuscript of an almanac for 1792 containing his ephemeris with his astronomical calculations. He retained handwritten copies of the letter and Jefferson's August 30, 1791, reply in a volume of manuscripts that became part of a journal.[95]

In late 1792, James Angell published a Baltimore edition of Banneker's 1793 almanac that contained copies of Banneker's letter and Jefferson's reply.[96] Soon afterwards, a Philadelphia printer distributed two sequential editions of a widely circulated pamphlet that also contained the letter and reply.[97]

The Universal Asylum, and Columbian Magazine also published Banneker's letter and Jefferson's reply in Philadelphia in late 1792.[98] The Magazine's editors (A Society of Gentlemen) titled the letter as being "from the famous self-taught astronomer, Benjamin Banneker, a black man".[98]

In his letter, Banneker accused Jefferson of criminally using fraud and violence to oppress his slaves.[93][99][100]

Jefferson's reply did not directly respond to Banneker's accusations, but instead expressed his support for the advancement of his "black brethren". His reply, which writers have characterized as "courteous", but "ambiguous" and "noncommittal",[101][102][103][104][105] stated:

Philadelphia Aug. 30. 1791.

Sir,

I thank you sincerely for your letter of the 19th. instant and for the Almanac it contained. no body wishes more than I do to see such proofs as you exhibit, that nature has given to our black brethren, talents equal to those of the other colours of men, & that the appearance of a want of them is owing merely to the degraded condition of their existence both in Africa & America. I can add with truth that no body wishes more ardently to see a good system commenced for raising the condition both of their body & mind to what it ought to be, as fast as the imbecillity of their present existence, and other circumstance which cannot be neglected, will admit. I have taken the liberty of sending your almanac to Monsieur de Condorcet, Secretary of the Academy of sciences at Paris, and member of the Philanthropic society because I considered it as a document to which your whole colour had a right for their justification against the doubts which have been entertained of them. I am with great esteem, Sir,

Your most obedt. humble servt.

Th: Jefferson[106]

Marie-Jean-Antoine-Nicolas de Caritat, Marquis de Condorcet, to whom Jefferson sent Banneker's almanac, was a noted French mathematician and abolitionist who was a member of the French Société des Amis des Noirs (Society of the Friends of the Blacks).[31][107] It appears that the Academy of Sciences itself did not receive the almanac.[29]

When writing his letter, Banneker informed Jefferson that his 1791 work with Andrew Ellicott on the District boundary survey had affected his work on his 1792 ephemeris and almanac.[93][108]

On the same day that he replied to Banneker (August 30, 1791), Jefferson sent a letter to the Marquis de Condorcet that contained the following paragraph relating to Banneker's race, abilities, almanac and work with Andrew Ellicott:

I am happy to be able to inform you that we have now in the United States a negro, the son of a black man born in Africa, and of a black woman born in the United States, who is a very respectable mathematician. I procured him to be employed under one of our chief directors in laying out the new federal city on the Patowmac, & in the intervals of his leisure, while on that work, he made an Almanac for the next year, which he sent me in his own hand writing, & which I inclose to you. I have seen very elegant solutions of Geometrical problems by him. Add to this that he is a very worthy & respectable member of society. He is a free man. I shall be delighted to see these instances of moral eminence so multiplied as to prove that the want of talents observed in them is merely the effect of their degraded condition, and not proceeding from any difference in the structure of the parts on which intellect depends.[109][110]

In 1809, three years after Banneker's death, Jefferson expressed a different opinion of Banneker in a letter to Joel Barlow that criticized a "diatribe" that a French abolitionist, Henri Grégoire, had written in 1808[111] saying that while "we know ourselves of Banneker. we know he had spherical trigonometry enough to make almanacs, but not without the suspicion of aid from Ellicot, who was his neighbor & friend, & never missed an opportunity of puffing him. I have a long letter from Banneker which shews him to have had a mind of very common stature indeed".[112][113]

Death

[edit]

For reasons that are unclear, the four editions of his 1797 almanac were the last ones that printers published.[114][115] After selling much of his homesite to the Ellicotts and others,[14][116] he probably died in his log cabin nine years later on October 19, 1806, aged 74.[117][118] (Some sources state that Banneker died on Sunday, October 9, 1806, which was actually a Thursday.)[4][119][120][118] His chronic alcoholism, which worsened as he aged, may have contributed to his death.[121]

Banneker never married.[122] An obituary concluded "Mr. Banneker is a prominent instance to prove that a descendant of Africa is susceptible of as great mental improvement and deep knowledge into the mysteries of nature as that of any other nation".[123]

A commemorative obelisk that the Maryland Bicentennial Commission and the State Commission on Afro American History and Culture erected in 1977 near his unmarked grave stands in the yard of the Mount Gilboa African Methodist Episcopal Church in Oella, Maryland (see Mount Gilboa Chapel).[124]

Artifacts

[edit]On the day of his funeral in 1806, a fire burned Banneker's log cabin to the ground, destroying many of his belongings and papers.[4][125][126]

- In 1813, William Goodard, who had published the Baltimore edition of Banneker's 1792 almanac (Banneker's first published almanac), donated the manuscript for the almanac to the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts.[127]

- The Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston holds in its collections the August 17, 1791, handwritten letter that Banneker sent to Thomas Jefferson.[128] Jefferson endorsed the letter as received on August 21, 1791.[129]

- The Library of Congress holds a copy of Jefferson's August 30, 1791, handwritten reply to Banneker.[130] Jefferson produced this document on a letter copying press made by James Watt & Co. that he used before he sent his reply to Banneker.[131] He retained the copy in his files.[132]

- The Library of Congress also holds a copy of Jefferson's August 30, 1791, handwritten letter to the Marquis de Condorcet that described Banneker's race, abilities, almanac and work with Andrew Ellicott.[109] Jefferson produced this document on his copying press before sending the handwritten letter to the Marquis.[133]

- The Library of Congress holds a handwritten duplicate of Jefferson's letter to the Marquis de Condorcet. The pagination in the duplicate differs from that in the copy that Jefferson produced on his copying press. The Library attributes the duplicate to Jefferson.[134]

- The Princeton University Library holds within its Straus Autograph Collection the recipient's copy of the handwritten letter that Jefferson sent to Joel Barlow in 1809. Jefferson's letter cited the letter that Banneker had sent to him in 1791. Barlow endorsed Jefferson's letter after he received it.[135]

- The Library of Congress holds a copy of Jefferson's 1809 letter to Joel Barlow that Jefferson had retained in his files after sending his handwritten letter to Barlow.[112] Jefferson used a polygraph device that enabled him to make the copy at the same time that he was writing the original. An Englishman, John Isaac Hawkins, and an American, Charles Willson Peale, had earlier developed this device with the help of Jefferson's suggestions.[135][136]

- In 1987, a member of the Ellicott family, which had retained Banneker's only remaining journal, donated that document and other Banneker manuscripts to the Maryland Historical Society in Baltimore.[137] The family also retained several items that Banneker had used after borrowing them from George Ellicott, as well as some that Banneker himself had owned.[125][138]

- In 1996, a descendant of George Ellicott decided to sell at auction some of those items, including a drop-leaf table, candlesticks, candle molds, maps, letters and diaries.[139] Although supporters of the planned Benjamin Banneker Historical Park and Museum in Oella, Maryland, had hoped to obtain these and several other items related to Banneker and the Ellicotts, a Virginia investment banker won most of the items with a series of bids that totaled $85,000. The purchaser stated that he expected to keep some of the items and to donate the rest to the planned African American Civil War Memorial museum in Washington, D.C.[140][141][142]

- In 1997, it was announced that the artifacts would initially be exhibited in the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and then loaned to the Banneker-Douglass Museum in Annapolis, Maryland. After completion of the Benjamin Banneker Historical Park and Museum in Oella, the artifacts would be loaned to that facility for a period of twenty years.[143] The Oella museum displayed the table, candle molds and candlesticks after it opened in 1998.[144]

Mythology and commemorations

[edit]

A substantial mythology exaggerating Banneker's accomplishments has developed during the two centuries that have elapsed since his death, becoming a part of African-American culture.[145][146] Several such urban legends describe Banneker's alleged activities in the Washington, D.C., area around the time that he assisted Andrew Ellicott in the federal district boundary survey.[41][147][148] Others involve his clock, his astronomical works, his almanacs and his journals.[147][149]

A United States postage stamp and the names of a number of recreational and cultural facilities, schools, streets, and other facilities and institutions throughout the United States have commemorated Banneker's documented and mythical accomplishments throughout the years since he lived. In 1983, Rita Dove, a future Poet Laureate of the United States,[150] wrote a biographical poem about Banneker while on the faculty of Arizona State University.[151][152]

Electronic copies of Banneker's publications

[edit]- Banneker, Benjamin (1791). "Benjamin Banneker's Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia Almanack and EPHEMERIS, for the YEAR of our LORD, 1792; Being BISSEXTILE, or LEAP-YEAR, and the Sixteenth Year of AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE, which commenced July 4, 1776" (48 digitized images). Baltimore: Printed and sold, Wholesale and Retail, by William Goddard and James Angell, at their printing-office, in Market-Street. – Sold, also, by Mr. Joseph Crukshank, Printer, in Market-Street, and Mr. Daniel Humphreys, Printer, in South-Front-Street, Philadelphia – and by Messrs. Hanson and Bond, Printers, in Alexandria. LCCN 98650590. OCLC 39311640. Archived from the original on April 21, 2020. Retrieved April 21, 2020 – via Library of Congress.

- Banneker, Benjamin (1792a). Banneker's Almanack and Ephemeris for the Year of Our Lord 1793; being The First After Bissextile or Leap Year. Philadelphia: Printed and Sold by Joseph Crukshank, No. 87, High-Street.

- (1) In Whiteman, Maxwell (ed.). Banneker's Almanack and Ephemeris for the Year of Our Lord 1793; being The First After Bissextile or Leap Year and Banneker's Almanac, For the Year 1795, Being the Third After Leap Year: Afro-American History Series: Rhistoric Publication No. 202 (47 digitized images). Rhistoric publications (1969 Reprint ed.). Rhistoric Publications, a division of Microsurance Inc. LCCN 72077039. OCLC 907004619. Retrieved June 14, 2017 – via HathiTrust Digital Library.

- (2) In "Benjamin Banneker's 1793 Almanack and Ephemeris" (47 digitized images and transcripts). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution: Smithsonian Digital Volunteers: Transcription Center. Archived from the original on April 15, 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- Banneker, Benjamin (1792b). Copy of a letter from Benjamin Banneker to the secretary of state, with his answer (1 digitized image). Philadelphia: Printed and sold by Daniel Lawrence, No. 33. North Fourth-Street, Near Race. LCCN 17022848. OCLC 614046208. Retrieved March 16, 2020 – via Library of Congress.

- (1) Pages 3–10: Banneker, Benjamin (August 19, 1791). Copy of a letter from Benjamin Banneker, &c (8 digitized images). Baltimore County, Maryland.

- (2) Pages 11–12: Jefferson, Thomas (August 30, 1791). To Mr. Benjamin Banneker (2 digitized images). Philadelphia.

- A Society of Gentlemen, ed. (October 1792). "(1) Letter from the famous self-taught astronomer, Benjamin Banneker, a black man, to Thomas Jefferson, Esq., Secretary of State (2) Mr. Jefferson's answer to the preceding letter: To Mr. Benjamin Banneker" (1 digitized image). The Universal Asylum, and Columbian Magazine. 6. Philadelphia: Printed for the Proprietors, by William Young, Bookseller, Philadelphia: 222–224. LCCN sn98034230. OCLC 50655818. Retrieved September 23, 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- Banneker, Benjamin (1794). Banneker's Almanac, for the Year 1795: Being the Third After Leap Year: Containing, (besides every thing necessary in an almanac,) an Account of the Yellow Fever, lately prevalent in Philadelphia, with the Number of those who died, from the First of August till the Ninth of November, 1793 (35 digitized images). Rhistoric publications. Philadelphia: Printed for William Young, Bookseller, no. 52, the Corner of Chesnut and Second—streets. OCLC 62824552. In Whiteman, Maxwell (ed.). Banneker's Almanack and Ephemeris for BISSEXTILE or Leap Year and Bannekeer's Almanac, For the Year 1795, Being the Third After Leap Year: Afro-American History Series: Rhistoric Publication No. 202 (1 digitized image). Rhistoric publications (1969 Reprint ed.). Rhistoric Publications, a division of Microsurance Inc. LCCN 72077039. OCLC 907004619. Retrieved June 14, 2017 – via HathiTrust Digital Library.

- Banneker, Benjamin (1795). Bannaker's Maryland, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Virginia, Kentucky, and North Carolina Almanack and EPHEMERIS, for the YEAR of our LORD 1796; Being BISSEXTILE, or LEAP YEAR; The Twentieth Year of AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE, And Eighth Year of the FEDERAL GOVERNMENT (35 digitized images). Baltimore: Printed for Philip Edwards, James Keddie, and Thomas, Andrews and Butler; and Sold at their respective Stores, Wholesale and Retail. OCLC 62824546. Retrieved June 13, 2017 – via HathiTrust Digital Library.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ (1) Cropped image extracted from Highsmith, Carol M. (photographer). ""Benjamin Banneker: Surveyor-Inventor-Astronomer", mural by Maxime Seelbinder, at the Recorder of Deeds building, built in 1943. 515 D St., NW, Washington, D.C." (photograph). Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. Archived from the original on November 1, 2017. Retrieved November 5, 2017.

(2) "Recorder of Deeds Building: Seelbinder Mural – Washington DC". The Living New Deal. Archived from the original on January 11, 2020. Retrieved January 11, 2020..

(3) Norfleet, Nicole (March 11, 2010). "D.C. Recorder of Deeds moving but fate of murals unclear". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on October 3, 2016. Retrieved October 3, 2016.

(4) Sefton, D. P., DC Preservation League, Washington, D.C. (July 1, 2010). "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Recorder of Deeds Building" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: District of Columbia Office of Planning. pp. 18–19. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 5, 2016. Retrieved October 3, 2016.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Boyd, Julian P., ed. (1974). "Locating the Federal District: Editorial Note: Footnote number 119". The Papers of Thomas Jefferson: 24 January–31 March 1791. Vol. 19. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 41–43. ISBN 9780691185255. LCCN 50007486. OCLC 1045069058. Retrieved March 27, 2019 – via Google Books.

Recent biographical accounts of Benjamin Banneker (1731–1806)…have done his memory a disservice by obscuring his real achievements under a cloud of extravagant claims to scientific accomplishment that have no foundation in fact. The single notable exception is Silvio A. Bedini's The Life of Benjamin Banneker (New York, 1972), a work of painstaking research and scrupulous attention to accuracy

- ^ Maryland Historical Society Library Department (February 6, 2014). "The Dreams of Benjamin Banneker". H. Furlong Baldwin Library: Underbelly. Maryland Historical Society. Archived from the original on September 17, 2020. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

Over the 200 years since the death of Benjamin Banneker (1731–1806), his story has become a muddled combination of fact, inference, misinformation, hyperbole, and legend. Like many other figures throughout history, the small amount of surviving source material has nurtured the development of a degree of mythology surrounding his story.

- ^ a b c d e "Benjamin Banneker | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com.

- ^ a b c Heinegg, Paul (December 11, 2016). "Banneker Family". Free African Americans of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland and Delaware: Free African Americans of Maryland and Delaware: Adams-Butler. Archived from the original on June 24, 2017. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- ^ (1) Banneker, 1792b, p. 6. "Sir, I freely and cheerfully acknowledge, that I am of the African race, and in that color which is natural to them of the deepest dye"

(2) McHenry, pp. 185-186. "BENJAMIN BANNEKER, a free Negro, has calculated an Almanack for the ensuing Year, 1792, ..... . "This Man is about fifty-nine years in age; he was born in Baltimore county; his father was an African, and his mother, the offspring of African parents."

(3) Latrobe, p. 6. "His father was a native African, and his mother the child of natives of Africa; so that to no admixture of the blood of the white man was he indebted for his peculiar and extraordinary abilities." - ^ a b c Perot, full text, pp. 5, 19–21, 33–36, 67.

- ^ (1) Russell, George Ely (December 2006). "Molly Welsh: Alleged Grandmother of Benjamin Banneker". National Genealogical Society Quarterly. 94 (4). National Genealogical Society: 305–314. ISSN 0027-934X. LCCN 17012813. OCLC 50612104. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ^ Johnson, Richard (January 18, 2018). "Benjamin Banneker (1731-1806)". Black Past. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020.

Benjamin seems to have served as an indentured laborer on the Prince George's County plantation of Mary Welsh, who had dealings with the Bannaky family and in 1773 executed her dead husband's instructions to release several of her labor force including "Negro Ben, born free age 43." Walsh was surely not Banneker's grandmother, as argued by many biographers, but she did leave him a substantial legacy. He then lived alone as a tobacco farmer near the Patapsco River.

- ^ a b c Tyson, Martha (Ellicott) (June 30, 1854). "A sketch of the life of Benjamin Banneker; from notes taken in 1836". [Baltimore] Printed by J. D. Toy – via Internet Archive.

- ^ (1) "Banaka Map — Satellite Images of Banaka". maplandia.com: google maps world gazetteer. 2016. Archived from the original on May 6, 2020. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

This place is situated in Klay, Bomi Terr., Liberia, its geographical coordinates are 6° 49' 44" North, 10° 46' 21" West and its original name (with diacritics) is Banaka.

(2) "Banaka / Bomi County". getamap.net. 2020. Archived from the original on May 6, 2020. Retrieved May 6, 2020.Banaka (Banaka) is a populated place .... in Bomi County (Bomi), Liberia (Africa) .... . It is located at an elevation of 117 meters above sea level.

(3) "Where is Banaka in Liberia Located?". GoMapper. 2020. Archived from the original on May 6, 2020. Retrieved May 6, 2020.Banaka is a place with a very small population in the country of Liberia .... . Cities, towns and places near Banaka include Bonja, Kuodi, Wuefa and Fassa. The closest major cities include Monrovia, Freetown, Conakry and Daloa.

(4) Coordinates of Banaka: 6°49′43″N 10°46′19″W / 6.828698°N 10.7719071°W - ^ Heinegg, Paul (2021). "Banneker Family". Free African Americans of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland and Delaware: Free African Americans of Maryland and Delaware: Adams-Butler. Archived from the original on September 14, 2021. Retrieved September 14, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bedini, Silvio A. (June 30, 1971). "The life of Benjamin Banneker". New York, Scribner – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Hurry, Robert J. (2007). "Banneker, Benjamin". In Hockey, Thomas (ed.). Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer. pp. 91–92. ISBN 9780387310220. OCLC 65764986. Retrieved July 29, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Glawe, Eddie (February 13, 2014). "Feature: Benjamin Banneker". xyHt. Archived from the original on August 18, 2015. Retrieved March 26, 2025.

This indenture made this tenth day of March in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred thirty seven between Richard Gist... of the one part, Robert Bannaky and [his son] Benjamin Bannaky... of the other part

- ^ Facsimile of handwritten deed conveying property from Richard Gist to Robert Bannaky and Benjamin Bannaky. In Clark, James W., Maryland Commission on Afro-American and Indian History and Culture, Annapolis, Maryland (June 14, 1976). "Benjamin Banneker Homesite" (PDF). Maryland State Historical Trust: Inventory Form for State Historic Sites Survey. Annapolis, Maryland: Maryland State Archives. p. 16. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 18, 2015. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ (1) McHenry, pp. 185-186. "This man is about fifty-nine years of age; he was born in Baltimore county; his father was an African, and his mother the offspring of African parents. His father and mother having obtained their freedom, were enabled to send him to an obscure school, where he learned, as a boy, reading, writing, and arithmetic, as far as double position.

(2) "Double position". Webster's 1913 Dictionary. Archived from the original on June 14, 2020. Retrieved June 14, 2020.(Arith.) the method of solving problems by proceeding with each of two assumed numbers, according to the conditions of the problem, and by comparing the difference of the results with those of the numbers, deducing the correction to be applied to one of them to obtain the true result.

(3) Adams, Daniel (1807). "Section III. § 10. Position: Double Position". The Scholar's Arithmetic; or, Federal Accountant (4th ed.). Keene, New Hampshire: Printed by and for John Prentiss, (proprietor of the copy-right) and sold at his book-store, wholesale and retail.--Sold also by the principal booksellers in New-England, and at the Rensselaer book-store, Troy, N.Y. pp. 201–202. LCCN 38021948. OCLC 1153971636. Retrieved June 22, 2020 – via HathiTrust Digital Library. - ^ (1) Graham, 1949, p. 45. Not until all the tobacco was in and "the Christmas" over was the school opened. Among the boys who sat on the smooth log facing Peter Heinrich was the dark boy. .... The dark boy's name seemed rather long. For Peter Heinrich wrote "Benjamin Banneker". .... And thus the spelling was changed from that in the earliest records.

(2) Bedini, 1972, p. 300. "Martha Tyson's posthumous book was the last work about Banneker to be based on original materials. During the next several decades, numerous articles in periodicals and newspapers mentioned Banneker's life and works, but each was based on earlier publications without contributing new materials. .... Finally, in 1949 another biography of Banneker appeared. This work by Shirley Graham was highly fictionalized and written for young people. It became popular, but the lack of distinction between fact and fiction in its presentation, while a compliment to the writing skill of Shirley Graham, has resulted in yet more confusion concerning Banneker's achievements and their importance." - ^ a b (1) Cerami, 2002, pp. 24–28.

(2) Corrigan, 2003, p. 2 "Cerami constructs a credible narrative of Banneker's life, but fails to document his research." - ^ Graham, 1949, p. 52. "The school was now housed in a building all its own and was supported by the Society of Friends. Though Ben was no longer a regular attendant he still considered himself a pupil. Very often when his days work was done he rode over to Master Heinrich's house for talk or to exchange a book"

- ^ a b John Hazlehurst Boneval Latrobe, Maryland Historical Society (June 30, 1845). "Memoir of Benjamin Banneker: Read Before the Maryland Historical Society, at ..." Printed by John D. Toy – via Internet Archive.

- ^ (1) Tyson, pp. 5, 9–10, 18.

(2) Hartshorne, Henry, ed. (June 21, 1884). "Book Notice: Banneker, the Afric-American Astronomer. From the posthumous papers of M.E. Tyson. Edited by Her Daughter. Phila. 1020 Arch Street. 1884". Friends Review: A Religious, Literary and Miscellaneous Journal. 37 (46). Philadelphia: Franklin E. Paige: 729. Archived from the original on January 16, 2017. Retrieved January 16, 2017.

(3) Bedini, 1964, p. 22.

(4) Bedini, 1999, p. 44. "Completed in 1753, Bannekers' clock continued to operate until his death, more than 50 years later."

(5) Bedini, 2008 "At about the age of twenty-one he (Banneker) constructed a striking wall clock, without ever having seen one. .... The clock continued to function successfully for more than fifty years, until his death."

(6) Bailey, Chris H. (1975). Two Hundred Years of American Clocks & Watches. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc. p. 73. ISBN 0139351302. LCCN 75013714. OCLC 756413530. Retrieved March 29, 2019. - ^ (1) Heinegg, Paul (December 11, 2016). "Banneker Family". Free African Americans of Maryland and Delaware. Archived from the original on June 24, 2017. Retrieved June 24, 2017.

(2) "Petitions for and against removal of the county seat of Baltimore County from Joppa to Baltimore Town, 1768: A. Petitions for removal of the County Seat" (PDF). Maryland State Archives (Archives of Maryland On-Line). 61: 520–554. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 9, 2018. Retrieved February 9, 2018.Benjamin Banneker (page 551)

- ^ Bedini, 1999, pp. 47, 368–369.

- ^ a b "Historic Ellicott City's History". ellicottcity.net. Ellicott City, Maryland: Ellicott City Graphic Arts. Archived from the original on August 10, 2015. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

- ^ Tyson, Martha Ellicott (1865). "A Brief Account of the Settlement of Ellicott's Mills". A Brief Account of the Settlement of Ellicott's Mills, with Fragments of History therewith Connected: Written at the request of Evan T. Ellicott, Baltimore, 1865: Read before the Maryland Historical Society, Nov. 3, 1870. Baltimore: Printed by J. Murphy: Printer to the Maryland Historical Society. pp. 3–4. LCCN rc01003387. OCLC 777869103. Retrieved December 2, 2020 – via Internet Archive.

The earliest observable change in the agricultural system of Maryland, was occasioned by a purchase made in 1772, by the brothers Joseph, Andrew and John Ellicott, of lands and mill-sites on the Patapsco river, 10 miles west of Baltimore, and by the building of their mills for grinding wheat and other grains. The purchase embraced the lands, on both sides of the Patapsco, for four miles in extent, and included all the water power within that distance, .....

- ^ Mayer, Brantz (1871). "Baltimore: From the End of the War with Great Britain and the Opening of the South American Trade to the Present Time". Baltimore: Past and Present. With Biographical Sketches of its Representative Men. Baltimore: Richardson & Bennett. p. 93. LCCN rc01003450. OCLC 1041066526. Retrieved December 2, 2020 – via Internet Archive.

In the city, and within the compass of twenty miles around it, there were upwards of sixty grain mills, of various descriptions, in which it was said that fully a million and a quarter of dollars were invested. This, of course, was an element of great prospective wealth, especially as the water power for manufactures, within the radius of those twenty miles, at Patapsco Falls, ....

- ^ Arnold, Melissa (January 2, 2001). "Ellicotts, Banneker found common ground in science". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "The life of Benjamin Banneker". Maryland Historical Society. June 30, 1999 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Williams, George Washington (June 30, 1885). "History of the Negro race in America from 1619 to 1880. Negroes as slaves, as soldiers, and as citizens; together with a preliminary consideration of the unity of the human family, an historical sketch of Africa, and an account of the negro governments of Sierra Leone and Liberia". New York, London, G.P. Putnam's Sons – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Glawe". February 13, 2014. Archived from the original on August 18, 2015. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- ^ a b "Catonsville, MD – Oella – Benjamin Banneker's Historical Park & Museum – Time Line". May 31, 2010. Archived from the original on May 31, 2010.

- ^ (1) Bedini, 1969, p. 8.

(2) Bedini, 1999, pp. 81–87; p. 371, references 3, 4, 5; p. 382, reference 12.

(3) Arnold, Melissa (January 2, 2001). "Ellicotts, Banneker found common ground in science". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

(4) McHenry, p. 186. "It is about three years since mr. George Ellicott lent him Mayer's tables, Ferguson's astronomy, Leadbeater's lunar tables and some astronomical instruments, but without accompanying them with either hint or instruction, that might further his studies, or lead him to apply them to any useful result. These books and instruments, the first of the kind that he had ever seen, opened a new world to Benjamin, and from thence forward he employed his leisure in astronomical researches."

(5) Mayer, Tobias (1770). Maskelyne, Nevil (ed.). New and correct tables of the motions of the sun and moon (in Latin and English). London: William and John Richardson: Sold by John Nourse, John Mount and Thomas Page. OCLC 981762891. Retrieved June 22, 2020 – via Google Books.

(6) Ferguson, James (1756). Astronomy Explained Upon Sir Isaac Newton's Principles,: And Made Easy to Those who Have Not Studied Mathematics. London: Printed for, and sold by the author, at the Globe, opposite Cecil-street in the Strand. LCCN ltf91075548. OCLC 55560074. Retrieved June 22, 2020 – via Google Books.

(7) Leadbetter, Charles (1742). A Compleat System of Astronomy (2nd ed.). London: J. Wilcox. LCCN 45046785. OCLC 822001557. Retrieved June 22, 2020. - ^ McHenry, p. 186. "He (Banneker) now took up the idea for calculations for an almanac, and actually completed and entire set for the last year, upon his original stock of arithmetic. Encouraged by this first attempt, he entered upon his calculation for 1792, which as well as the former, he began and finished without the least information, or assistance, from any person or other books, than those that I have mentioned; so that, whatever merit is attached to his present performance, is exclusively and peculiarly his own."

- ^ a b c d e f Tise, Larry E. (June 30, 1998). The American Counterrevolution: A Retreat from Liberty, 1783–1800. Stackpole Books. ISBN 9780811701006 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e National Capital Planning Commission (1976). "History". Boundary markers of the Nation's Capital: a proposal for their preservation & protection: a National Capital Planning Commission Bicentennial report. Washington, D.C.: National Capital Planning Commission; For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, United States Government Printing Office. p. 9. OCLC 3772302. Retrieved February 22, 2016 – via HathiTrust Digital Library.

... Andrew Ellicott retained Banneker to make the astronomical calculations necessary to establish the location of the south corner stone, while Ellicott and the field crews did the actual surveying.

- ^ a b c d (1) Bedini, 1999, pp. 110–114, 133–134.

(2) "Boundary Stones of the District of Columbia". boundarystones.org. Archived from the original on December 27, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2014..

(3) Crew, pp. 87–103.

(4) Langelan, Chas (August 24, 2012). "Andrew Ellicott and his Survey of the Federal Territory on the Potomac, 1791–1793". Philip Lee Philips Society Annual Conference: Visualizing The Nation's Capital: Two Centuries of Mapping Washington, D.C., Session 2 (moderator: Bill Stanley). Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. Archived from the original (transcript) on March 2, 2016. Retrieved February 21, 2016. - ^ "Text of Residence Act". American Memory: A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 – 1875: Statutes at Large, 1st Congress, 2nd Session, p. 130, July 16, 1790: Chapter 28: An Act for establishing the temporary and permanent seat of the Government of the United States. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on September 13, 2009. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- ^ Bedini, 1972, p. 137. "He (Banneker) served in the true sense of an assistant to Ellicott himself, making notes for him, making calculations as required, and using the astronomical equipment for establishing base points."

- ^ Bedini, 1972, p. 103. "Curiously enough, the record of Banneker's participation rests on extremely meager documentation, consisting of a statement written in a letter by Thomas Jefferson and two statements made by Banneker himself."

- ^ a b Boyd, Julian P., ed. (1974). "Locating the Federal District: Editorial Note: Footnote number 119". The Papers of Thomas Jefferson: 24 January–31 March 1791. Vol. 19. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 41–43. ISBN 9780691185255. LCCN 50007486. OCLC 1045069058. Retrieved March 27, 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ (1) "New Federal City" (PDF). Columbian Centennial. No. 744. Boston, Massachusetts: Benjamin Russell. May 7, 1791. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 30, 2016. Retrieved October 9, 2016 – via boundarystones.org.

(2) Bedini, 1972, pp. 124, 314 - ^ (1) Bedini, 1969, p. 25.

(2) "New Federal City" (PDF). Columbian Centennial. No. 744. Boston, Massachusetts: Benjamin Russell. May 7, 1791. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 30, 2016. Retrieved October 9, 2016 – via boundarystones.org. - ^ Banneker, 1792b, pp. 9–10. "And altho I had almost declined to make my calculation for the ensuing year, in consequence of that time which I had allotted therefor being taking up at the Federal Territory by the request of Mr. Andrew Ellicott, yet finding myself under several engagments to Printers of this state, to whom I had communicated my design, upon my return to my place of residence, I industriously applied myself thereto, ....".

- ^ a b c d Bedini, 1999, pp. 132, 136.

- ^ Bedini, 1999, pp. 129, 132–136.

- ^ (1) Davis, Nancy M. (August 26, 2001). "Andrew Ellicott: Astronomer…mathematician…surveyor". Philadelphia Connection. Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation: Philadelphia Chapter. Archived from the original on September 29, 2018. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

After the war, he (Ellicott) returned to Fountainvale, the family home in Ellicott Upper Mills, and published a series of almanacs, The United States Almanack. (The earliest known copy is dated 1782.)

(2) Drake, p. 214. "The MARYLAND, Delaware, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and North-Carolina Almanack and Ephemeris for 1781. By Andrew Ellicott. Baltimore: M. K. Goddard: Philadelphia: Benjamin January."

(3) Drake, p. 511. "UNITED States Almanack for 1782. By Andrew Ellicott. Chatham: Shepard Kollock."

(4) Drake, p. 215. "ELLICOTT'S Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia Almanack and Ephemeris for 1786. Baltimore: Goddard and Langworthy."

(5) Drake, p. 216. "ELLICOTT'S Maryland and Virginia Almanack, and Ephemeris for 1787. Baltimore: John Hayes."

(6) Drake, p. 216. "The MARYLAND and Virginia Almanack, and Ephemeris for 1788. By Andrew Ellicott. Baltimore: John Hayes."

(7) Drake, p. 216. "POOR Robin's Almanac for 1788. By Andrew Ellicott. Frederick-Town: Matthias Bartgis. .... 2112"

(8) Drake, p. 217. "ELLICOTT'S Maryland and Virginia Almanack, and Ephemeris for 1789. Baltimore: John Hayes."

(9) Drake, p. 217. "ELLICOTT'S Maryland and Virginia Almanack, and Ephemeris for 1790. Baltimore: John Hayes."

(10) Drake, p. 217. "ELLICOTT'S Maryland and Virginia Almanack and Ephemeris for 1791. Baltimore: John Hayes."

(11) Bedini, 1999, pp. 97, 109, 210. - ^ (1) Morrison, p. 70. "The New-Jersey almanack for 1788. The astronomical calculations by Wm. Waring. Trenton: Isaac Collins."

(2) Morrison, p. 138. "Poulson's town and country almanac for 1789. The astronomical calculations by Wm. Waring, teacher of mathematics in the Friends' academy. Philadelphia: Zachariah Poulson, junior".

(3) Morrison, p. 70. "The New-Jersey almanack for 1789. By Wm. Waring. Trenton: Isaac Collins."

(4) Morrison, p. 70. "The New-Jersey almanack for 1790. By Wm. Waring. Trenton: Isaac Collins."

(5) Morrison, p. 139. "Poor Will's almanac for 1790. The astronom. calculations by Wm. Waring. Philadelphia: Joseph Crukshank."

(6) Morrison, p. 139. "Poulson's town and country almanac for 1790. By Wm. Waring. Philadelphia: Zachariah Poulson, jr."

(7) Morrison, p. 139. "Poulson's town and country almanac for 1791. By Wm. Waring. Philadelphia: Zachariah Poulson, jr." - ^ (1) Morrison, p. 156. "The Virginia Almanac for 1774. By the celebrated Mr. Rittenhouse, Philomath. Williamsburg: William Rind."

(2) Morrison, p. 157. "The Virginia Almanac for 1780. By David Rittenhouse, Philo. Williamsburg: J. Dixon & T. Nicolson."

(3) Drake, p. 214. "The MARYLAND, Virginia and Pennsylvania Almanack and Ephemeris for 1780. By David Rittenhouse. Baltimore: M. K. Goddard."

(5) Morrison, p. 132. "The Continental almanac for 1781. By Anthony Sharpe, Philom. Philadelphia: Francis Bailey."

(6) Morrison, p. 132. "The Continental pocket almanac for 1781. By Anthony Sharpe (i.e., David Rittenhouse). Philadelphia: Francis Bailey. 1780." - ^ "David Rittenhouse (1732–1796)". Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Archives & Records Center. Archived from the original on January 23, 2019. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- ^ Cerami, p. 150. "I am annoyed to find that the subject of my race is so much stressed," he (Banneker) remarked. "The work is either correct or it is not. In this case, I believe it to be perfect."

- ^ (1) Bedini, 1972, p. 157.

(2) Morrison, p. 123-140.

(3) Morrison, p. 139. "Poor Will's almanac for 1790. The astronom. calculations by Wm. Waring. Philadelphia: Joseph Crukshank." - ^ (1) Drake, pp. 214–218.

(2) Bedini, 1972, pp. 164–173.

(3) "Almanac". In Pursuit of a Vision: Two Centuries of Collecting at the American Antiquarian Society. Worcester, Massachusetts: American Antiquarian Society. 2012. Archived from the original on August 15, 2017. Retrieved February 11, 2018.Benjamin Banneker. Holographic manuscript of his 1792 almanac and ephemeris, with the published edition: Benjamin Banneker's Almanack. Baltimore: William Goddard and James Angell …, both 1791. Manuscript: Gift of William Goddard, 1813. Published almanac: Gift of Samuel L. Munson, 1925

- ^ (1) List of Banneker's almanacs: Bedini, 1999, pp. 393–396. "Banneker's Letters and Almanacs"

(2) List of Banneker's almanacs, with links: "Benjamin Banneker". Shakeospeare. The University of Iowa Libraries. March 3, 2017. Archived from the original on March 14, 2017. Retrieved March 14, 2017. - ^ (1) Banneker, Benjamin (1791). Benjamin Banneker's Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia Almanack and EPHEMERIS, for the YEAR of our LORD, 1792; Being BISSEXTILE, or LEAP-YEAR, and the Sixteenth Year of AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE, which commenced July 4, 1776 (48 digitized images). Baltimore: Printed and sold, Wholesale and Retail, by William Goddard and James Angell, at their printing-office, in Market-Street. – Sold, also, by Mr. Joseph Crukshank, Printer, in Market-Street, and Mr. Daniel Humphreys, Printer, in South-Front-Street, Philadelphia – and by Messrs. Hanson and Bond, Printers, in Alexandria. LCCN 98650590. OCLC 39311640. Retrieved April 21, 2020 – via Library of Congress. Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 393, Reference 2.

(2) Banneker, Benjamin (1791). Benjamin Banneker's Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia Almanack and Ephemeris for 1792. Baltimore: William Goddard and James Angell. Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 393, Reference 3.

(3) Banneker, Benjamin (1791). Banneker's almanac for 1792. Philadelphia: Printed for William Young, Bookseller, No. 52, Second-street, the corner of Chesnut-street. Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 393, Reference 4.

(4) Banneker, Benjamin (1792). Benjamin Banneker's 1793 Almanack and Ephemeris; being The First After Bissextile or Leap-Year. Philadelphia: Printed and Sold by Joseph Crukshank, No. 87, High-Street.

(a) Complete almanac (47 digitized images and transcripts). Archived from the original on April 15, 2020. Retrieved April 26, 2020 – via Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution: Smithsonian Digital Volunteers: Transcription Center.

(b) "Title Page" (1 digitized image). Archived from the original on April 26, 2020. Retrieved April 26, 2020 – via American Antiquarian Society: Black Self-Publishing.

Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 394, Reference 5.

(5) (a) Banneker, Benjamin (1792). "Title Page". Benjamin Banneker's almanac, for the year of our Lord, 1793; Being the first after BISSEXTILE, or LEAP-YEAR, and the Seventeenth Year of AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE, which commenced July 4, 1776 (1 digitized image). Baltimore: Printed and sold, wholesale and retail, by William Goddard and James Angell, at their printing-office, in Market-Street. An original copy of Benjamin Banneker Almanac: Contributor: Michael Ventura / Alamy Stock Photo. LCCN 98650590. OCLC 1053084527. Retrieved March 1, 2021 – via Alamy.

(b) Banneker, Benjamin (1792). "Title Page". Benjamin Banneker's almanac, for the year of our Lord, 1793; Being the first after BISSEXTILE, or LEAP-YEAR, and the Seventeenth Year of AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE, which commenced July 4, 1776 (1 digitized image). Baltimore: Printed and sold, wholesale and retail, by William Goddard and James Angell, at their printing-office, in Market-Street. Exhibit in Benjamin Banneker Museum, Oella, Maryland. Photographer: F. Delvanthal. LCCN 98650590. OCLC 1053084527. Archived from the original on November 9, 2019. Retrieved November 9, 2019 – via Flickr (February 18, 2017).

(c) Banneker, Benjamin (February 18, 2017). "Page for October". Benjamin Banneker's almanac, for the year of our Lord, 1793; Being the first after BISSEXTILE, or LEAP-YEAR, and the Seventeenth Year of AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE, which commenced July 4, 1776 (1 digitized image). Baltimore: Printed and sold, wholesale and retail, by William Goddard and James Angell, at their printing-office, in Market-Street. Exhibit in Benjamin Banneker Museum, Oella, Maryland. Photographer: F. Delvanthal. LCCN 98650590. OCLC 1053084527. Archived from the original on November 9, 2019. Retrieved November 9, 2019 – via Flickr (February 18, 2017)..

Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 394, Reference 6.

(6) Banneker, Benjamin (1793). "Title Page". Banneker's ALMANACK and EPHEMERIS, for the YEAR of our LORD, 1794; Being The Second After Bissextile or Leap-Year (1 digitized image). Philadelphia: Printed and sold by Joseph Crukshank, No. 87, High-Street. OCLC 62824554. Archived from the original on April 26, 2020. Retrieved April 26, 2020 – via American Antiquarian Society: Black Self-Publishing. Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 394, Reference 7.

(7) Banneker, Benjamin (1793). "Title Page". Benjamin Banneker's Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia almanack and ephemeris, for the year of our Lord, 1794; Being the second after BISSEXTILE, or LEAP-YEAR, and the Eigtheenth Year of AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE, which commenced July 4, 1776 (1 digitized image). Baltimore: Printed and sold, wholesale and retail, by James Angell, at his printing-office, in Market-Street. OCLC 62824561. Archived from the original on March 1, 2021. Retrieved March 1, 2021 – via American Antiquarian Society: Black Self-Publishing. Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 394, Reference 8.

(8) Banneker, Benjamin (1793). "Title Page". Benjamin Banneker's ALMANAC, for the Year of our Lord, 1794. Being the Second after Leap-Year (1 digitized image). Philadelphia: Printed by William Young, No. 52, Second-street, the corner of Chesnut-street. OCLC 226246930. Archived from the original on March 1, 2021. Retrieved April 26, 2020 – via American Antiquarian Society: Black Self-Publishing. Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 394, Reference 9.

(9) Banneker, Benjamin (1793). The Virginia almanack, for the year of our Lord, 1794. ... / Calculated by that ingenious self taught astronomer Benjamin Banneker, a black man. ... Petersburg Va.: Printed by William Prentis. OCLC 62840340. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020. Retrieved June 4, 2020 – via General catalog of the American Antiquarian Society. Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 394, Reference 10.

(10) Banneker, Benjamin (1794). "Bannaker's Bannaker's New-Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia almanac, or ephemeris, for the year of our Lord 1795; Being the Third after Leap-Year;——the Nineteenth Year of American Independence, and the Seventh of our Federal Government——Which may the Governor of the World prosper!". Wilmington, Delaware: Printed by S. & J. Adams. LCCN 2002205264. OCLC 49848126. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Retrieved February 28, 2021 – via Library of Congress. In "Benjamin Banneker's Almanac". Exhibition: Thomas Jefferson: Creating A Virginia Republic: Benjamin Banneker: Benjamin Banneker's Almanac. Library of Congress. Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 394, Reference 11.

(11) Banneker, Benjamin (1794). "Title Page". Bannaker's Wilmington almanac, or ephemeris, for the year of our Lord 1795; ——Being the Third after Leap-Year——; The Nineteenth Year of American Independence and the Seventh of our Federal Government——Which may the Governor of the World prosper! (1 digitized image). Wilmington, Delaware: Printed by S. & J. Adams, for Frederick Craig. OCLC 62824551. Archived from the original on March 1, 2021. Retrieved March 1, 2021 – via American Antiquarian Society: Black Self-Publishing. Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 395, Reference 12..

(12) Banneker, Benjamin (1794). Banneker's Almanac, for the Year 1795: Being the Third After Leap Year: Containing, (besides every thing necessary in an almanac,) an Account of the Yellow Fever, lately prevalent in Philadelphia, with the Number of those who died, from the First of August till the Ninth of November, 1793 (35 digitized images). Rhistoric publications. Philadelphia: Printed for William Young, Bookseller, no. 52, the Corner of Chesnut and Second—streets. OCLC 62824552. In Whiteman, 1969.

(13) Banneker, Benjamin (1794). Benjamin Bannaker's Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia almanac, for the year of our Lord 1795: Being the Third after Leap-Year. Philadelphia: Printed for William Gibbons, Cherry Street. OCLC 62824556. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020. Retrieved June 5, 2020 – via General catalog of the American Antiquarian Society. Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 395, Reference 14.

(14) Banneker, Benjamin (1794). Benjamin Bannaker's Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia almanac, for the year of our Lord 1795: Being the Third after Leap-Year. Philadelphia: Printed for Jacob Johnson & Co., No. 147 Market-Street.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 395, Reference 15. (15) Banneker, Benjamin (1794). Bannaker's Wilmington almanac, or ephemeris, for the year of our Lord 1795, ... Early American imprints. Wilmington, Delaware: Printed by S. & J. Adams. OCLC 22052469. Retrieved April 23, 2020 – via Villanova University: Falvey Memorial Library. Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 395, Reference 16. (16) Banneker, Benjamin (1794). Bannaker's Wilmington almanac, or ephemeris, for the year of our Lord 1795, Being the Third after Leap Year. Wilmington, Delaware: Printed by S. & J. Adams, for W. C. Smyth. Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 395, Reference 17. (17) Banneker, Benjamin (1794). Benjamin Bannakar's Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia almanac for 1795. Wilmington, Delaware: Printed by S. & J. Adams. Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 395, Reference 18. (18) (a) Bannaker, Benjamin (1794). "Title Page (with portrait of Banneker)". Bannaker's New-Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia Almanac, or Ephemeris, for the Year of our LORD 1795; Being the Third after Leap-Year. Baltimore, Maryland: Printed by S. & J. Adams. OCLC 62824547. Archived from the original (1 digitized image) on August 13, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2014 – via Library Company of Philadelphia. (b) Banneker, Benjamin (1794). "Title Page (with portrait of Banneker)". Banneker's New-Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia almanac, or Ephemeris, for the year of our Lord 1795: Being the Third after Leap-Year. Baltimore: Printed by S. & J. Adams. OCLC 62824547. Archived from the original (1 digitized image) on March 1, 2021. Retrieved April 23, 2020 – via American Antiquarian Society: Black Self-Publishing. Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 395, Reference 19. (19) Banneker, Benjamin (1794). New-Jersey & Pennsylvania Almanac, for the year of our Lord 1795: Being the Third after Leap-Year, and the Twentieth of American Independence, after the Fourth of July, Containing, Besides the Usual Requisites of an Almanac, A Variety of Entertaining Matter, in Prose and Verse. To Which is Added, An Account of the Yellow Fever, in Philadelphia. The Astronomical Calculations by Benjamin Banneker, An African. Trenton, New Jersey: Printed and Sold, Wholesale and Retail, by Mathias Day. OCLC 701855077. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020. Retrieved June 5, 2020 – via General catalog of the American Antiquarian Society. Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 395, Reference 20. (20) Banneker, Benjamin (1794). Banneker's New-Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia almanac, or Ephemeris, for the year of our Lord 1795: Being the Third after Leap-Year. Early American imprints. Wilmington, Delaware: Printed by S. & J. Adams. LCCN 2002205264. OCLC 1053444725. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved April 23, 2020 – via Villanova University: Falvey Memorial Library. Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 395, Reference 21. (21) Bannaker, Benjamin (1794). The Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia Almanack for the Year of our Lord 1795; Being the Third after Leap-Year. Baltimore: Printed by James Angell for Fisher and Cole. Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 396, Reference 22. (22) Banneker, Benjamin (1794). The Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia almanac, for the Year of Our Lord, 1795; Being the Third after Leap-Year. Wilmington, Delaware: Printed and sold by S. and J. Adams. Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 395, Reference 23. (23) (a) Bannaker, Benjamin (1794). "Title Page (with portrait of Banneker)". Benjamin Bannaker's Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia ALMANAC for the YEAR of our LORD 1795; Being the Third after Leap-Year (1 digitized image). Baltimore: Printed for And Sold by John Fisher, Stationer. OCLC 1053398713. Archived from the original on March 1, 2021. Retrieved March 1, 2021 – via American Antiquarian Society: Black Self-Publishing. (b) Bannaker, Benjamin (1794). "Title Page (with portrait of Banneker)". Benjamin Bannaker's Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia ALMANAC for the YEAR of our LORD 1795; Being the Third after Leap-Year. Baltimore: Printed for And Sold by John Fisher, Stationer. Archived from the original (1 digitized image) on July 24, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2019. In "Cover: Benjamin Bannaker" (Document). Baltimore, Maryland: Maryland Historical Society. 2018. (c) "Africans in America: Part 2: Historical Documents: Bannaker's New-Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia Almanac, or Ephemeris, for the Year of our LORD 1795; Being the Third after Leap-Year". Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2021. Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 396, Reference 24. (24) (a) Banneker, Benjamin (1795). Bannaker's Maryland, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Virginia, Kentucky, and North Carolina Almanack and EPHEMERIS, for the YEAR of our LORD 1796; Being BISSEXTILE, or LEAP YEAR; The Twentieth Year of AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE, And Eighth Year of the FEDERAL GOVERNMENT (35 digitized images). Baltimore: Printed for Philip Edwards, James Keddie, and Thomas, Andrews and Butler; and Sold at their respective Stores, Wholesale and Retail. OCLC 62824546. Retrieved June 13, 2017 – via HathiTrust Digital Library. (b) Banneker, Benjamin (1795). "Title Page". Bannaker's Maryland, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Virginia, Kentucky, and North Carolina Almanack and EPHEMERIS, for the YEAR of our LORD 1796; Being BISSEXTILE, or LEAP YEAR; The Twentieth Year of AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE, And Eighth Year of the FEDERAL GOVERNMENT (1 digitized image). Baltimore: Printed for Philip Edwards, James Keddie, and Thomas, Andrews and Butler; and Sold at their respective Stores, Wholesale and Retail. OCLC 62824546. Archived from the original on March 2, 2021 – via American Antiquarian Society: Black Self-Publishing.(b) Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 396, Reference 25. (25) Banneker, Benjamin. "Title Page". Bannaker's Virginia and North Carolina almanack and ephemeris, for the year of our Lord 1797 (1 digitized image). Petersburg VA: Printed by William Prentis and William Y. [i.e. T.] Murray. OCLC 62824548. Archived from the original on March 1, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2020 – via American Antiquarian Society: Black Self-Publishing. Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 396, Reference 26. (26) Banneker, Benjamin. "Title Page". Bannaker's Virginia, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Kentucky Almanack and EPHEMERIS, for the YEAR of our LORD 1797; Being the First after BISSEXTILE or LEAP-YEAR; The Twenty-First Year of AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE, And Ninth Year of the FEDERAL GOVERNMENT. Baltimore: Printed by Christopher Jackson, no. 67, Market-Street, for George Keatinge's book-store. [Copy right secured.] OCLC 62824549. Archived from the original (1 digitized image) on April 23, 2020. Retrieved April 23, 2020 – via American Antiquarian Society: Black Self-Publishing. Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 396, Reference 27. (27) Banneker, Benjamin. "Title Page". Bannaker's Virginia, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Kentucky almanack and ephemeris, for the year of our Lord 1797; Being the First after BISSEXTILE or LEAP-YEAR; The Twenty-First Year of AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE, And Ninth Year of the FEDERAL GOVERNMENT (1 digitized image). Richmond: Printed by Samuel Pleasants, Jun. near the vendue office. By privilege. OCLC 62824550. Archived from the original on March 1, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2020 – via American Antiquarian Society: Black Self-Publishing. Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 396, Reference 28. (28) Banneker, Benjamin. "Title Page". Bannaker's Maryland and Virginia almanack and ephemeris, for the year of our Lord 1797 (1 digitized image). Baltimore: Printed by Christopher Jackson, for George Keatinge's Wholesale and Retail book store, no. 140 Market-Street. ISBN 9780938420590. OCLC 62824545. In Bedini, 1999, p. 224. Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 396, Reference 29. - ^ (1) Banneker, 1791. Title Page (1 digitized image).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

(2) Latrobe, pp. 10–11. - ^ (1) Banneker, Benjamin (1792). Benjamin Banneker's almanac, for the year of our Lord, 1793; Being the first after BISSEXTILE, or LEAP-YEAR, and the Seventeenth Year of AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE, which commenced July 4, 1776 (1 digitized image). Baltimore: Printed and sold, wholesale and retail, by William Goddard and James Angell, at their printing-office, in Market-Street. Exhibit in Benjamin Banneker Museum, Oella, Maryland. Photographer: F. Delvanthal. LCCN 98650590. OCLC 1053084527. Archived from the original on November 9, 2019. Retrieved March 1, 2021 – via Flickr (February 18, 2017).

(2) Banneker, Benjamin (1793). Benjamin Banneker's Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia almanack and ephemeris, for the year of our Lord, 1794; Being the second after BISSEXTILE, or LEAP-YEAR, and the Eigtheenth Year of AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE, which commenced July 4, 1776 (1 digitized image). Baltimore: Printed and sold, wholesale and retail, by James Angell, at his printing-office, in Market-Street. OCLC 62824561. Archived from the original on March 1, 2021. Retrieved March 1, 2021 – via American Antiquarian Society: Black Self-Publishing. - ^ a b Woodcut portrait of Benjamin Bannaker (Banneker) in (a) Bannaker, Benjamin (1794). "Title Page (with portrait of Banneker)". Benjamin Bannaker's Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia ALMANAC for the YEAR of our LORD 1795; Being the Third after Leap-Year. Baltimore: Printed for And Sold by John Fisher, Stationer. Archived from the original (1 digitized image) on July 24, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2019. In "Cover: Benjamin Bannaker" (Document). Baltimore, Maryland: Maryland Historical Society. 2018.

(b) Bannaker, Benjamin (1794). "Title Page (with portrait of Banneker)". Benjamin Bannaker's Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia ALMANAC for the YEAR of our LORD 1795; Being the Third after Leap-Year. Baltimore: Printed for And Sold by John Fisher, Stationer. OCLC 62824557. Archived from the original on March 1, 2021. Retrieved June 5, 2020 – via General catalog of the American Antiquarian Society.

(c) "Benjamin Banneker's Almanac: 1795". Africans in America: Part 2: Bannaker's New-Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland and Virginia Almanac, or Ephemeris, for the Year of our LORD 1795; Being the Third after Leap-Year. Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). Archived from the original on November 27, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

Cited in Bedini, 1999, p. 396, Reference 24. - ^ (1) Bedini, 1999, p. 231.

(2) Banneker, 1791, p. 5. "A Tide-Table for the Chesapeake Bay." - ^ (1) Bedini, 1999, p. 232.

(2) Banneker, 1792a, p. 34. "RULE: To find the Time of High-Water at the following Places."

(3) Banneker, 1794, p. 4. "RULE to find the Time of High-water at the following Places:"

(4) Banneker, 1795, p. 32. "TABLE, ..." - ^ (1) Bedini, 1999, pp. 225–226.

(2) Banneker, 1791, pp. 7–18.

(3) Banneker, 1792a, pp. 4–26.

(4) Banneker, Benjamin. "Page for October". Benjamin Banneker's almanac, for the year of our Lord, 1793; Being the first after BISSEXTILE, or LEAP-YEAR, and the Seventeenth Year of AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE, which commenced July 4, 1776 (1 digitized image of photograph). Baltimore: Printed and sold, wholesale and retail, by William Goddard and James Angell, at their printing-office, in Market-Street. LCCN 98650590. OCLC 1053084527. Archived from the original on November 9, 2019. Retrieved November 9, 2019 – via Flickr. On display in the Benjamin Banneker Museum, Oella, Maryland. Photographed by F. Delventhal, February 18, 2017.

(5) Banneker, 1794, pp. 5–16.