Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

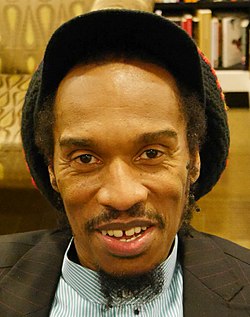

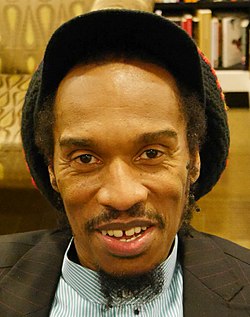

Benjamin Zephaniah

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Benjamin Obadiah Iqbal Zephaniah (15 April 1958 – 7 December 2023) was a British writer, dub poet, actor, musician and professor of poetry and creative writing. Over his lifetime, he was awarded 20 honorary doctorates in recognition of his contributions to literature, education, and the arts. He was included in The Times list of Britain's top 50 post-war writers in 2008. In his work, Zephaniah drew on his lived experiences of incarceration, racism and his Jamaican heritage.

He won the BBC Radio 4 Young Playwrights Festival Award in 1998 and was the recipient of at least sixteen honorary doctorates. A ward at Ealing Hospital was also named in his honour. His second novel, Refugee Boy, was the recipient of the 2002 Portsmouth Book Award in the Longer Novel category. In 1982, he released an album, Rasta, which featured the Wailers performing for the first time since the death of Bob Marley, acting as a tribute to Nelson Mandela. It topped the charts in Yugoslavia, and due to its success Mandela invited Zephaniah to host the president's Two Nations Concert at the Royal Albert Hall, London, in 1996. As an actor, he had a major role in the BBC's Peaky Blinders between 2013 and 2022.

A vegan and animal rights activist, as well as an anarchist, Zephaniah supported changing the British electoral system from first-past-the-post to alternative vote. In 2003, Zephaniah was offered appointment as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE). He publicly rejected the honour, stating that: "I get angry when I hear that word 'empire'; it reminds me of slavery, it reminds of thousands of years of brutality, it reminds me of how my foremothers were raped and my forefathers, brutalised".

Early life

[edit]Benjamin Obadiah Iqbal Zephaniah was born on 15 April 1958,[1][2][3] in the Handsworth district of Birmingham, England, where he was also raised.[4][5] He referred to this area as the "Jamaican capital of Europe".[6] The son of parents who had migrated from the Caribbean – Oswald Springer, a Barbadian postman, and Leneve (née Honeyghan),[7] a Jamaican nurse who came to Britain in 1956 and worked for the National Health Service[8] – he had a total of seven younger siblings, including his twin sister, Velda.[2][3][9]

Zephaniah wrote that he was strongly influenced by the music and poetry of Jamaica and what he called "street politics", and he said in a 2005 interview:

Well, for most of the early part of my life I thought poetry was an oral thing. We used to listen to tapes from Jamaica of Louise Bennett, who we think of as the queen of all dub poets. For me, it was two things: it was words wanting to say something and words creating rhythm. Written poetry was a very strange thing that white people did.[10]

His first performance was in church when he was 11 years old, resulting in him adopting the name Zephaniah (after the biblical prophet),[2] and by the age of 15, his poetry was already known among Handsworth's Afro-Caribbean and Asian communities.[11]

He was educated at Broadway School, Birmingham, from which he was expelled aged 13, unable to read or write due to dyslexia.[9][3][2] He was sent to Boreatton Park approved school in Baschurch, Shropshire.[12]

The gift, during his childhood, of an old, manual typewriter inspired him to become a writer. It is now in the collection of Birmingham Museums Trust.[13]

As a youth, he spent time in borstal and in his late teens received a criminal record and served a prison sentence for burglary.[2][9][14][15] Tired of the limitations of being a black poet communicating with black people only, he decided to expand his audience, and in 1979, at the age of 22, he headed to London, where his first book would be published the next year.[16][17]

While living in London, Zephaniah was assaulted during the 1981 Brixton riots and chronicled his experiences on his 1982 album Rasta.[18] He experienced racism on a regular basis:[19]

They happened around me. Back then, racism was very in your face. There was the National Front against black and foreign people, and the police were also very racist. I got stopped four times after I bought a BMW when I became successful with poetry. I kept getting stopped by the police, so I sold it.

In a session with John Peel on 1 February 1983 – one of two Peel sessions he recorded that year – Zephaniah's responses were recorded in such poems as "Dis Policeman", "The Boat", "Riot in Progress" and "Uprising Downtown".[20][21]

Written work and poetry

[edit]Having moved to London, Zephaniah became actively involved in a workers' co-operative in Stratford, which led to the publication of his first book of poetry, Pen Rhythm (Page One Books, 1980). He had earlier been turned down by other publishers who did not believe there would be an audience for his work, and "they didn't understand it because it was supposed to be performed".[22] Three editions of Pen Rhythm were published. Zephaniah said that his mission was to fight the dead image of poetry in academia, and to "take [it] everywhere" to people who do not read books, so he turned poetry readings into concert-like performances,[16] sometimes with The Benjamin Zephaniah Band.[16][23]

His second collection of poetry, The Dread Affair: Collected Poems (1985), contained a number of poems attacking the British legal system.[24] Rasta Time in Palestine (1990), an account of a visit to the Palestinian occupied territories, contained poetry and travelogue.[25]

Zephaniah was poet-in-residence at the chambers of Michael Mansfield QC, and sat in on the inquiry into Bloody Sunday and other cases,[26] these experiences led to his Too Black, Too Strong poetry collection (2001).[9] We Are Britain! (2002) is a collection of poems celebrating cultural diversity in Britain.[24]

He published several collections of poems, as well as novels, specifically for young people.[27] Talking Turkeys (1994), his first poetry book for children, was reprinted after six weeks.[28][29] In 1999, he wrote his first novel Face – a story of "facial discrimination", as he described it[27] – which was intended for teenagers, and sold some 66,000 copies.[23][30][31][32] Poet Raymond Antrobus, who was given the novel when he had just started attending a deaf school, has written: "I remember reading the whole thing in one go. I was very self-conscious about wearing hearing aids and I needed stories that humanised disability, as Face did. I was still struggling with my literacy at the time, and I understood Benjamin as someone who was self-taught and had been marginalised within the education system. And so he really felt like an ambassador for young people like me."[33]

Zephaniah's second novel Refugee Boy, about a 14-year-old refugee from Ethiopia and Eritrea,[34] was published in August 2001. It was the recipient of the 2002 Portsmouth Book Award in the Longer Novel category,[27][35] and went on to sell 88,000 copies.[23] In 2013, Refugee Boy was adapted as a play by Zephaniah's long-time friend Lemn Sissay, staged at the West Yorkshire Playhouse.[36][37][38]

In May 2011, Zephaniah accepted a year-long position as poet-in-residence at Keats House in Hampstead, London, his first residency role for more than ten years. In accepting the role, he commented: "I don't do residencies, but Keats is different. He's a one-off, and he has always been one of my favourite poets."[39][40] The same year, he was appointed professor of poetry and creative writing at Brunel University London.[2][41][42]

In 2016, Zephaniah wrote the foreword to Angry White People: Coming Face-to-Face with the British Far Right by Hsiao-Hung Pai.[43]

Zephaniah's frank autobiography, The Life and Rhymes of Benjamin Zephaniah, was published to coincide with his 60th birthday in 2018, when BBC Sounds broadcast him reading his own text. "I'm still as angry as I was in my twenties," he said.[44][45] The book was nominated as "autobiography of the year" at the National Book Awards.[4]

The Birmingham Mail dubbed him "The people's laureate".[46]

On the publication of his young adult novel Windrush Child in 2020, Zephaniah was outspoken about the importance of the way history is represented in the curriculum of schools.[47][48]

Acting and media appearances

[edit]Zephaniah made minor appearances in several television programmes in the 1980s and 1990s, including The Comic Strip Presents... (1988), EastEnders (1993), The Bill (1994), and Crucial Tales (1996).[49] In 1990, he appeared in the film Farendj, directed by Sabine Prenczina and starring Tim Roth.[50]

He was the "castaway" on the 8 June 1997 episode of the BBC Radio 4 programme Desert Island Discs, where his chosen book was the Poetical Works of Shelley.[51]

In 2005, BBC One broadcast a television documentary about his life, A Picture of Birmingham, by Benjamin Zephaniah, which was repeated by BBC Two on 7 December 2023.[52]

In December 2012, he was guest editor of an episode of the BBC Radio 4 programme Today, for which he commissioned a "good news bulletin".[53][54]

Between 2013 and 2022, Zephaniah played the role of preacher Jeremiah "Jimmy" Jesus in BBC television drama Peaky Blinders, appearing in 14 episodes across the six series.[55]

In 2020, he appeared as a panellist on the BBC television comedy quiz show QI, on the episode "Roaming".[56]

Music

[edit]In 1982, Zephaniah released the album Rasta, which featured the Wailers' first recording since the death of Bob Marley as well as a tribute to the political prisoner (later to become South African president) Nelson Mandela. The album gained Zephaniah international prestige[57] and topped the Yugoslavian pop charts.[11][57] It was because of this recording that he was introduced to Mandela, and in 1996, Mandela requested that Zephaniah host the president's Two Nations Concert at the Royal Albert Hall, London.[19][58]

Zephaniah released a total of seven albums of original music.[3][59]

Views

[edit]Zephaniah was connected with – and served as patron for – many organizations that aligned with his beliefs.[60][61]

Animal rights and veganism

[edit]Zephaniah became a vegetarian at the age of 11,[62] and then became a vegan at the age of 13,[63][64] when he read poems about "shimmering fish floating in an underwater paradise, and birds flying free in the clear blue sky".

He was an honorary patron of The Vegan Society,[65] Viva!,[66] and EVOLVE! Campaigns,[67] and was an animal rights advocate. In 2004, he wrote the foreword to Keith Mann's book From Dusk 'til Dawn: An insider's view of the growth of the Animal Liberation Movement, a book about the Animal Liberation Front. In August 2007, he announced that he would be launching the Animal Liberation Project, alongside People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals.[68] In February 2001, his book The Little Book of Vegan Poems was published by AK Press.[69]

Anti-racism activism

[edit]Zephaniah spoke extensively about his personal experiences of anti-Black racism in Britain and incorporated his experiences in much of his written work.[70]

In 2012, Zephaniah worked with anti-racism organisation Newham Monitoring Project, with whom he made a video,[71][72] and Tower Hamlets Summer University (Futureversity) about the impact of Olympic policing on black communities.[73] In that same year, he also wrote about cases of racially abusive language employed by police officers and "the reality of police racism that many of us experience all the time".[74]

In November 2003, Zephaniah was offered appointment in the 2004 New Year Honours as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE), for which he said he had been recommended by Tony Blair. But he publicly rejected the honour[75][76] and in a subsequent article for The Guardian, elaborated on learning about being considered for the award and his reasons for rejecting it: "Me? I thought, OBE me? Up yours, I thought. I get angry when I hear that word 'empire'; it reminds me of slavery, it reminds of thousands of years of brutality, it reminds me of how my foremothers were raped and my forefathers brutalised... Benjamin Zephaniah OBE – no way Mr Blair, no way Mrs Queen. I am profoundly anti-empire."[77][78]

Other activism

[edit]Zephaniah spoke in favour of a British republic and the dis-establishment of the Crown.[79] In 2015, he called for Welsh and Cornish to be taught in English schools, saying: "Hindi, Chinese and French are taught [in schools], so why not Welsh? And why not Cornish? They're part of our culture."[80]

Zephaniah supported Amnesty International in 2005, speaking out against homophobia in Jamaica, saying: "For many years Jamaica was associated with freedom fighters and liberators, so it hurts when I see that the home of my parents is now associated with the persecution of people because of their sexual orientation."[81]

In 2016, Zephaniah curated We Are All Human, an exhibition at London's Southbank Centre presented by the Koestler Trust, which exhibited art works by prisoners, detainees and ex-offenders.[82]

Zephaniah was a supporter of the Palestine Solidarity Campaign and joined demonstrations calling for an end to the Israeli occupation of Palestinian lands, describing the activism as the "Anti Apartheid movement". He was also a supporter of the BDS (Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions) movement.[83][84]

Political views

[edit]Zephaniah self-identified as an anarchist;[85] observing in a 2022 interview: "...there are places that live without government and live peacefully and happily. A lack of power means people of course aren't fighting over it and the main objective of society is to look after each other."[86] He appeared in literature to support changing the British electoral system from first-past-the-post to alternative vote for electing members of parliament to the House of Commons in the Alternative Vote referendum in 2011.[87] In a 2017 interview, commenting on the ongoing Brexit negotiations, Zephaniah stated: "For left-wing reasons, I think we should leave the EU but the way that we're leaving is completely wrong."[88]

In December 2019, along with 42 other leading cultural figures, he signed a letter endorsing the Labour Party under Jeremy Corbyn's leadership in the 2019 general election. The letter stated: "Labour's election manifesto under Jeremy Corbyn's leadership offers a transformative plan that prioritises the needs of people and the planet over private profit and the vested interests of a few."[89][90]

Achievements and recognition

[edit]

In 1998, Zephaniah was a winner of the BBC Young Playwrights Festival Award with his first ever radio play Hurricane Dub.[1][27][91]

In 1999, he was the subject of an illustrated biographical children's book by Verna Wilkins, entitled Benjamin Zephaniah: A Profile, published in the Black Stars Series of Tamarind Books.[92]

Zephaniah was awarded at least 16 honorary doctorates,[93] by institutions including the University of North London (in 1998),[1] the University of Central England (1999), Staffordshire University (2001),[94] London South Bank University (2003), the University of Exeter, the Open University (2004),[95] Birmingham City University (2005), the University of Westminster (2006), the University of Birmingham (2008)[96] and the University of Hull (DLitt, 2010).[97]

In 2008, he was listed at 48 in The Times list of 50 greatest post-war writers.[98] A ward at Ealing Hospital was named in his honour.[93]

He was awarded Best Original Song in the Hancocks 2008, Talkawhile Awards for Folk Music (as voted by members of Talkawhile.co.uk[99]) for "Tam Lyn Retold", recorded with The Imagined Village project on their eponymous 2007 album. He collected the award at The Cambridge Folk Festival on 2 August 2008, describing himself as a "Rasta Folkie".[100]

To mark National Poetry Day in 2009, the BBC ran an online poll to find the nation's favourite poet, with Zephaniah taking third place in the public vote, behind T. S. Eliot and John Donne, and being the only living poet to be named in the top 10.[101][102]

Zephaniah's 2020 reality television series Life & Rhymes, on Sky Arts, celebrating spoken-word performances,[103][104] won a British Academy Television Award (BAFTA), the Lew Grade Award for Best Entertainment Programme, in 2021.[105][106][3][42]

In April 2025, Brunel University held a Benjamin Zephaniah Day in a campus space newly named in his honour. His wife Qian Zephaniah, Michael Rosen, Jeremy Corbyn and Linton Kwesi Johnson attended.[107]

In May 2025, Birmingham City University renamed the former University House in honour of Zephaniah.[108]

Personal life

[edit]Zephaniah lived for many years in east London; however, in 2008, he began dividing his time between Moulton Chapel near Spalding, Lincolnshire, and Beijing in China.[109][108] He was a keen language learner and studied Mandarin Chinese for more than a decade.[110]

Zephaniah was married for 12 years to Amina, a theatre administrator. His infertility – which he discussed openly[111] – meant that they could not have children and his criminal record prevented them from adopting.[3] They divorced in 2001.[112]

In 2017, Zephaniah married Qian Zheng, whom he had met on a visit to China three years earlier, and who survives him.[2]

In May 2018, in an interview of BBC Radio 5 Live, Zephaniah admitted that he had been violent to a former partner, confessing to having hit her. He said:

The way I treated some of my girlfriends was terrible. At one point I was violent. I was never like one of these persons who have a girlfriend, who'd constantly beat them, but I could lose my temper sometimes... There was one girlfriend that I had, and I actually hit her a couple of times, and as I got older I really regretted it. It burned my conscience so badly. It really ate at me, you know. And I'm a meditator. It got in the way of my meditation.[113]

His cousin, Michael Powell, died in police custody, at Thornhill Road police station in Birmingham, in September 2003 and Zephaniah regularly raised the matter,[77][114] continuously campaigning with his brother Tippa Naphtali, who set up a national memorial fund in Powell's name to help families affected by deaths in similar circumstances.[115]

Zephaniah's family was Christian but he became a Rastafarian at a young age.[116][117] He gave up smoking cannabis in his thirties.[118]

He was a supporter of Aston Villa F.C. – having been taken to matches as a boy, by an uncle[3][119] – and was the patron for an Aston Villa supporters' website,[120] as well as an ambassador for the club's charity, the Aston Villa Foundation.[121][122]

Death and legacy

[edit]Zephaniah died on 7 December 2023, at the age of 65, after being diagnosed with a brain tumour eight weeks previously.[3][4][123][124] His friend of nearly twenty years, Joan Armatrading, gave a tribute to him on Newsnight on BBC Two after hearing the news of his death. Writing on Twitter, she said: "I am in shock. Benjamin Zephaniah has died age 65. What a thoughtful, kind and caring man he was. The world has lost a poet, an intellectual and a cultural revolutionary. I have lost a great friend."[125]

The BBC later re-broadcast Zephaniah's documentary A Picture of Birmingham, in which he revisited his birthplace and his former approved school.[52] Fiona Bruce, the presenter of BBC's Question Time, on which Zephaniah was a regular panellist, paid tribute to him, saying: "He was an all round, just tremendous bloke" for whom she had "huge affection and respect".[126]

According to Martin Glynn of Birmingham City University, Zephaniah was "never an establishment person", but "got into spaces" where he felt he could be heard. Glynn said: "He was the James Brown of dub poetry, the godfather... Linton Kwesi Johnson spoke to the political classes, but Benjamin was a humanist, he made poetry popular and loved music. He had his own studio.... He did what John Cooper Clarke did with poetry and that was bringing it into the mainstream."[127]

The family issued a statement on 7 December regarding Benjamin Zephaniah's death, saying: "Thank you for the love you have shown Professor Benjamin Zephaniah."[128]

Aston Villa Football Club paid tribute to Zephaniah on Saturday, 9 December 2023, in advance of their home match against Arsenal F.C., by playing on the big screens his ode to Villa, originally recorded in 2015.[129][130]

His private funeral, attended by close friends and family, took place on 28 December, and it was requested that well-wishers plant flowers, trees or plants in Zephaniah’s honour, rather than sending cut flowers.[131][132]

An artwork featuring Zephaniah that appeared on the wall of an underpass in Hockley, Birmingham, in March 2024 was accidentally painted over by a council sub-contractor employed to remove graffiti, although Zephaniah's family had been given assurances that the mural would be protected.[133][134] Following a public backlash,[135] an apology was issued,[136][137] and new artwork was subsequently commissioned from black artists, to be unveiled on 14 April at Handsworth Park.[138][139]

As a tribute, in April 2024, BBC Radio 4 broadcast the 2018 Book of the Week recording of Zephaniah reading his autobiography, The Life and Rhymes of Benjamin Zephaniah.[140]

In September 2024, an outdoor space at Brunel University of London was named after Zephaniah.[141] Since April 2025, Brunel University also hosts a "Benjamin Zephaniah Day" near the date of 15 April (Zephaniah's birthday).[142]

Books

[edit]Poetry

[edit]- Pen Rhythm (1980), Page One, ISBN 978-0907373001

- The Dread Affair: Collected Poems (1985), Arena, ISBN 978-0099392507

- Rasta time in Palestine (1990), Shakti Publishing Ltd., ISBN 978-0951655108

- City Psalms (1992), Bloodaxe Books, ISBN 978-1852242305

- Inna Liverpool (1992), AK Press, ISBN 978-1873176757

- Talking Turkeys (1994), Puffin Books, ISBN 978-0140363302

- Propa Propaganda (1996), Bloodaxe Books, ISBN 978-1852243722

- Funky Chickens (1997), Puffin, ISBN 978-0140379457

- School's Out: Poems Not for School (1997), AK Press, ISBN 978-1873176498

- Funky Turkeys (audiobook) (1999), Puffin, ASIN B07VJJ8WCX[143]

- Wicked World! (2000), Puffin Random House, ISBN 978-0141306834

- Too Black, Too Strong (2001), Bloodaxe Books, ISBN 978-1852245542

- The Little Book of Vegan Poems (2001), AK Press, ISBN 978-1902593333

- Reggae Head (2006), spoken word audio CD, 57 Productions, ISBN 978-1899021055

- To Do Wid Me (2013), Bloodaxe Books, feature film by Pamela Robertson-Pearce released on DVD with accompanying book, ISBN 978-1852249434

- Dis Poetry (2025), Bloodaxe Books, ISBN 978-1780377414

Novels

[edit]- Face (1999), Bloomsbury (published in children's and adult editions)

- Refugee Boy (2001), Bloomsbury

- Gangsta Rap (2004), Bloomsbury

- Teacher's Dead (2007), Bloomsbury

- Terror Kid (2014), Bloomsbury[144]

- Windrush Child (2020), Scholastic, ISBN 978-0702302725

Biographies

[edit]- We Sang Across the Sea: The Empire Windrush and Me (2022), Scholastic. ISBN 978-0702311161 – a biography of Mona Baptiste written by Zephaniah and illustrated by Onyinye Iwu.[145]

Children's books

[edit]- We Are Britain (2002), Frances Lincoln Publishers

- Primary Rhyming Dictionary (2004), Chambers Harrap

- J Is for Jamaica (2006), Frances Lincoln

- My Story (2011), Collins

- When I Grow Up (2011), Frances Lincoln

- Nature Trail (2021), Hachette children

- We Sang Across the Sea (2022), Hachette children

- People Need People (2022), Hachette children

- Leave Trees Please (2025), Scholastic

Other

[edit]- Kung Fu Trip (2011), Bloomsbury

- The Life And Rhymes of Benjamin Zephaniah (2018), Simon & Schuster[44]

Plays

[edit]- Playing the Right Tune (1985)

- Job Rocking (1987). Published in Black Plays: 2, ed. Yvonne Brewster, Methuen Drama, 1989.

- Delirium (1987)

- Streetwise (1990)

- Mickey Tekka (1991)

- Listen to Your Parents (included in Theatre Centre: Plays for Young People – Celebrating 50 Years of Theatre Centre, 2003, Aurora Metro; also published by Longman, 2007)

- Face: The Play (with Richard Conlon)

Acting roles

[edit]- Didn't You Kill My Brother? (1987) – Rufus

- Farendj (1989) – Moses

- Dread Poets' Society (1992) – himself

- Truth or Dairy (1994) – The Vegan Society (UK)

- Crucial Tales (1996) – Richard's father

- Making the Connection (2010) – Environment Films / The Vegan Society (UK)

- Peaky Blinders (2013–2022) – Jeremiah Jesus

Discography

[edit]Albums

[edit]- Rasta (1982), Upright (reissued 1989), Workers Playtime (UK Indie #22)[146]

- Us An Dem (1990), Island

- Back to Roots (1995), Acid Jazz

- Belly of De Beast (1996), Ariwa

- Naked (2005), One Little Indian

- Naked & Mixed-Up (2006), One Little Indian (Benjamin Zephaniah Vs. Rodney-P)

- Revolutionary Minds (2017), Fane Productions

Singles and EPs

[edit]- Dub Ranting EP (1982), Radical Wallpaper

- Big Boys Don't Make Girls Cry 12-inch single (1984), Upright

- Free South Africa (1986)

- Crisis 12-inch single (1992), Workers Playtime

Guest appearances

[edit]- Empire (1995), Bomb the Bass with Zephaniah & Sinéad O'Connor

- Heading for the Door by Back to Base (2000), MPR Records

- Illegal (2000), from "Himawari" by Swayzak

- Theatricks (2000), by Kinobe

- Open Wide (2004), Dubioza kolektiv (C) & (P) Gramofon

- Rebel by Toddla T (2009), 1965 Records

- New Dawn (2009) by Pat D & Lady Paradox[147]

- Take A Ride and I Have A Dream (2013) by L.B. Dub Corp[148]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Gregory, Andy (2002). International Who's Who in Popular Music 2002. Europa. p. 562. ISBN 1-85743-161-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mason, Peter (7 December 2023). "Benjamin Zephaniah obituary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 December 2023. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Benjamin Zephaniah, poet treasured as 'The people's laureate' who performed to a reggae backbeat – obituary". The Telegraph. 7 December 2023. Retrieved 8 December 2023 – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ^ a b c McIntosh, Steven (7 December 2023). "Benjamin Zephaniah: Writer and poet dies aged 65". BBC News. Archived from the original on 7 December 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ "Benjamin Zephaniah". British Council. Archived from the original on 3 October 2007.

- ^ Gordon, Mandisa (28 October 2014). "Handsworth Spirit". BBC. Archived from the original on 11 August 2021. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ Zephaniah, Benjamin (2019). The Life and Rhymes of Benjamin Zephaniah. Scribner UK. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-471-16895-6.

- ^ "Coronavirus: Benjamin Zephaniah 'scared' after two family members die of COVID-19". Sky News. 5 June 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d Kellaway, Kate (4 November 2001). "Dread poet's society". The Observer. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ Jones, Simon Joseph (24 May 2005). "Dread Right?". High Profiles. Archived from the original on 13 December 2023. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ a b Larkin, Colin (1998). The Virgin Encyclopedia of Reggae. Virgin Books. ISBN 0-7535-0242-9.

- ^ "Benjamin Zephaniah: Shrewsbury ex-teacher remembers 'star' pupil". BBC News. 8 December 2023. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ "Aston Hall 1". Antiques Roadshow. Series 44. Episode 4. 7 November 2021. BBC Television. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ Alberge, Dalya (28 January 2018). "'I went off the rails': how Benjamin Zephaniah went from borstal to poet". The Observer. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2023 – via The Guardian.

- ^ "Interview with Raw Edge Magazine: Benjamin talks about how life in prison helped change his future as a poet". Raw Edge. No. 5. Autumn–Winter 1997. Archived from the original on 20 May 2009.

- ^ a b c "Biography". Benjamin Zephaniah. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ Cousins, Emily (7 June 2010). "Benjamin Zephaniah (1958– )". Blackpast.org. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ hukla, Anu S (10 April 2018). "' Reforming has done nothing. That's why I'm an anarchist.' An interview with Benjamin Zephaniah". Red Pepper. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ a b Maciuca, Andra (29 October 2019). "Benjamin Zephaniah on Nelson Mandela, Bob Marley and race riots". Saffron Walden Reporter. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ "BENJAMIN ZEPHANIAH John Peel 1st February 1983". 6 April 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2023 – via YouTube.

- ^ "6 Music Live Hour | Benjamin Zephaniah - Archive session (1994)". BBC Radio 6. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ "Benjamin Zephaniah – Poet, Novelist, Playwright and Activist". h2g2. BBC. 12 May 2008. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ a b c Bayley, Sian (7 December 2023). "Benjamin Zephaniah dies aged 65". The Bookseller. Archived from the original on 13 December 2023. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ a b Alghanem, Alanoud Abdulaziz (21 May 2023). "Remaking Britain: The Afro-Caribbean Impact on English Literature". Journal of Namibian Studies: History Politics Culture. 33: 2096–2118. doi:10.59670/jns.v33i.833. ISSN 2197-5523. S2CID 259408168.

- ^ Sathyadas, Susan (2017). "Benjamin Zephaniah: Contemporary Voice of Resistance in Black Britain" (PDF). International Journal of English and Literature. 7 (4): 83–90. doi:10.24247/ijelaug20179 (inactive 1 July 2025).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of July 2025 (link) - ^ Berlins, Marcel (20 November 2000). "Poetic justice". The Guardian.

- ^ a b c d "Literature | Benjamin Zephaniah". British Council. Archived from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ "BBC – Arts – Poetry: Out Loud". www.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Zephaniah, Benjamin (October 2015). Talking Turkeys. www.penguin.co.uk. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ "FACE by Benjamin Zephaniah (The Play) | Teaching Resources". www.tes.com. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Cart, Michael. "Face By Benjamin Zephaniah. | Booklist Online". Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021 – via www.booklistonline.com.

- ^ "Children's Book Review: FACE by Benjamin Zephaniah, Author . Bloomsbury $15.95 (208p) ISBN 978-1-58234-774-5". PublishersWeekly.com. November 2002. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Antrobus, Raymond (16 December 2023). "Benjamin Zephaniah remembered by Raymond Antrobus". The Guardian.

- ^ Bethal: The Girl With the Reading Habit, DG Readers (23 November 2015). "Children's books | Refugee Boy by Benjamin Zephaniah - review". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ "High Profile: Dread Right? Simon Jones talks to Benjamin Zephaniah". Third Way. Vol. 28, no. 5. Hymns Ancient & Modern Ltd. Summer 2005. p. 20.

- ^ Sissay, Lemn; Goddard, Lynette (1 October 2022). "Refugee Boy by Lemn Sissay". Drama & Theatre. Archived from the original on 1 July 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ "Benjamin Zephaniah's Refugee Boy steps on stage". BBC News. 14 March 2013. Archived from the original on 20 November 2023. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ Brown, Jonathan (18 March 2013). "Refugee Boy, West Yorkshire Playhouse, Leeds". The Independent. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ Greenstreet, Rosanna (14 October 2011). "Q&A: Benjamin Zephaniah". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Zephaniah, Benjamin. "Benjamin Zephaniah to take up Keats House residency". www.foyles.co.uk. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ "Professor Benjamin Zephaniah | Professor - Creative Writing". Brunel University London. Archived from the original on 16 December 2023. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ a b Buchanunn, Joe (8 December 2023). "Professor Benjamin Zephaniah, Brunel Professor of Creative Writing, dies aged 65". Brunel University London. Archived from the original on 9 December 2023. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ Zephaniah, Benjamin (28 February 2016). "Benjamin Zephaniah on fighting the far right: 'If we did nothing we would be killed on the streets'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 February 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ a b Jonasson, Jonas (15 August 2017). "S&S scoops Zephaniah's memoir". The Bookseller. Archived from the original on 27 August 2018. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- ^ "The Life And Rhymes of Benjamin Zephaniah". BBC Sounds. 30 April 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ The Life And Rhymes of Benjamin Zephaniah. Simon & Schuster. 2 May 2019. ISBN 9781471168956. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ Zephaniah, Benjamin (12 October 2020). "Black people will not be respected until our history is respected". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 14 December 2023. Retrieved 14 December 2023.

- ^ Drabble, Emily (29 October 2020). "Benjamin Zephaniah on Windrush Child: 'We have to learn from the past'". BookTrust. Archived from the original on 14 December 2023. Retrieved 14 December 2023.

- ^ "Benjamin Zephaniah". IMDb. Archived from the original on 15 December 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ Prenczina, Sabine (27 March 1991). "Farendj" (Drama). Tim Roth, Marie Matheron, Matthias Habich, Joe Sheridan. River Films, Sofica Lumière, Trimark Entertainment. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ "BBC Radio 4 - Desert Island Discs, Benjamin Zephaniah". BBC. Archived from the original on 4 November 2023. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ a b "BBC One – A Picture of Birmingham, by Benjamin Zephaniah". BBC. Archived from the original on 30 August 2022. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ "Today: Monday 31st December". BBC Radio 4 | Today. 31 December 2012. Archived from the original on 13 December 2023. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ "Today Advent Calendar: 8th December". BBC Radio 4. 8 December 2023. Archived from the original on 13 December 2023. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ Layton, Josh (7 January 2018). "Peaky Blinders actor on the real-life character behind TV role". BirminghamLive. Archived from the original on 15 December 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ "Roaming". QI. Series R. Episode 11. BBC Television. Archived from the original on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ a b Cobley, Mike (21 June 2023). "Brighton Magazine – Benjamin Zephaniah: Well Read Rastafarian Poet Comes To Lewes". Magazine.brighton.co.uk. Archived from the original on 15 December 2023. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ^ "Benjamin Zephaniah – Nelson Mandela | urbanimage.tv". urbanimage.photoshelter.com. Archived from the original on 15 December 2023. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Perry, Kevin (7 March 2006). "Benjamin Zephaniah interview about Naked". London: The Beaver. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ^ "Biography | CV Type Thing". Benjamin Zephaniah. Archived from the original on 26 November 2023. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ Zephaniah, Benjamin (30 October 2012). "Youth Unemployment: I Wanted to Use Poetry to Speak for Myself". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 16 December 2023. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ Zephaniah, Benjamin (28 December 2022). "'I'll stop saying I don't eat meat – and tell people I don't eat animals': the thing I'll do differently in 2023". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ Ridgers, Karin (4 July 2016). "Benjamin Zephaniah: The Interview". www.veganfoodandliving.com. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Hind, John (17 July 2010). "Interview: Benjamin Zephaniah". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ "Honorary Patrons". Vegansociety.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- ^ "Benjamin Zephaniah". Viva! The Vegan Charity. 23 February 2024 [Original date 6 November 2020].

- ^ "Evolve Campaigns". EVOLVE! Campaigns. Archived from the original on 15 December 2023. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- ^ "UK | Benjamin Zephaniah set to launch 'Animal Liberation Project'". Arkangel Magazine. 1 August 2007. Archived from the original on 17 April 2008.

- ^ "The Little Book Of Vegan Poems by Benjamin Zephaniah | Waterstones". www.waterstones.com. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Morris, Natalie (26 October 2020). "Benjamin Zephaniah: 'The racist thugs of my youth are older and wear suits now'". Metro. Archived from the original on 15 December 2023. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ "Benjamin Zephaniah – Put the Number in Your Phone". Newham Monitoring Project. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- ^ York, Melissa (30 March 2012). "Know your civil rights during 2012 Games". Newham Recorder. Archived from the original on 14 December 2023. Retrieved 14 December 2023.

- ^ Raffray, Nathalie (7 December 2023). "Obituary: 'Trailblazer' poet Benjamin Zephania dies aged 65". Ham&High. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ Zephaniah, Benjamin (26 October 2012). "The police don't work for us". The Guardian.

- ^ Mills, Merope (27 November 2003). "Rasta poet publicly rejects his OBE". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 August 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- ^ "British poet Benjamin Zephaniah dies aged 65: family". The Citizen. 8 December 2023. Archived from the original on 9 December 2023. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ a b Zephaniah, Benjamin (27 November 2003). "'Me? I thought, OBE me? Up yours, I thought'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 May 2020. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ Mills, Merope (27 November 2003). "Rasta poet publicly rejects his OBE". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 December 2023. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ "Statement of Principles". Republic. 29 April 2011. Archived from the original on 3 August 2009. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- ^ "Benjamin Zephaniah calls for English schools to teach Welsh". BBC News. 10 August 2015. Archived from the original on 9 December 2023. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- ^ "Jamaica: Benjamin Zephaniah calls on Jamaicans everywhere to stand up against homophobia". Amnesty International. 9 June 2005. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ^ Bankes, Ariane (8 January 2018). "Why we need to free art by prisoners from behind bars". Apollo Magazine. Archived from the original on 1 February 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ Sagir, Ceren (12 May 2019). "Thousands in London call for an end to Israeli occupation of Palestine". Morning Star. Archived from the original on 14 July 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Bratu, Alex (7 May 2019). "Birmingham poet Benjamin Zephaniah backs national demonstration for Palestine". I Am Birmingham. Archived from the original on 17 July 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- ^ Zephaniah, Benjamin (June 2019). "Why I Am an Anarchist". Dog Section Press. Archived from the original on 21 June 2019.

- ^ Seth, Arjun (27 October 2022). "Benjamin Zephaniah: 'I can make people think and change their minds'". Palatinate. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ "Benjamin Zephaniah 'airbrushed from Yes to AV leaflets'". BBC News. 3 April 2011. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ "Benjamin Zephaniah Q&A: 'My first racist attack was a brick in the back of the head'". New Statesman. 4 December 2017. Archived from the original on 10 May 2020. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- ^ "Letters | Vote for hope and a decent future". The Guardian. 3 December 2019. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ Proctor, Kate (3 December 2019). "Coogan and Klein lead cultural figures backing Corbyn and Labour". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 September 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- ^ "BBC Radio Young Writers: 25 Years On". BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ Wilkins, Verna (1999). Benjamin Zephaniah: A Profile. London: Tamarind. ISBN 9781870516389.

- ^ a b "Benjamin Zephaniah". Evolutionary Arts Hackney. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ "Recipients of Honorary Awards". Staffordshire University. Archived from the original on 22 February 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees". Open University. Archived from the original on 8 June 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ Collins, Tony (11 July 2008). "University honour for Doug Eliis". Birmingham Mail. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012.

- ^ "Honorary Graduates". University of Hull. Archived from the original on 9 December 2023. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ "Benjamin Zephaniah". TimesOnline UK. 5 January 2008. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011.

- ^ "TalkAwhile UK Acoustic music forum". Talkawhile.co.uk. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- ^ "Best Original Song". Talkawhile.co.uk. 3 August 2008. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- ^ "T.S. Eliot voted Britain's favourite poet in BBC poll". Reuters. 8 October 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ "The Nation's Favourite Poet Result - TS Eliot is your winner!". bbc.co.uk/poetryseason. BBC. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ "Life & Rhymes" on IMDb.

- ^ "How to watch BAFTA-winning Life & Rhymes". radiotimes.com. 7 June 2021. Archived from the original on 7 June 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ "BAFTA Award winning Sky Original Life & Rhymes returns for a second series on Sky Arts". Sky. 18 June 2021. Archived from the original on 13 February 2023. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ "BAFTA TV 2021: The Winners and Nominations for the Virgin Media British Academy Television Awards and British Academy Television Craft Awards". BAFTA. 28 April 2021. Archived from the original on 7 June 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ "Brunel honours Zephaniah with special celebration". The Voice. May 2025. p. 3.

- ^ a b Asokan, Shyamantha (19 May 2025). "University names building after Benjamin Zephaniah". BBC News. Retrieved 23 June 2025.

- ^ Barber, Lynn (18 January 2009). "The interview: Benjamin Zephaniah". The Observer. Archived from the original on 30 March 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ "Benjamin Zephaniah on Learning Mandarin Chinese (Podcast)". ImLearningMandarin.com. 12 November 2021. Archived from the original on 5 March 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ Zephaniah, Benjamin (5 August 2022). "Benjamin Zephaniah: I'm 64 and my infertility still brings me to tears". inews.co.uk. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ "Arts and Books". The Independent. 19 June 2009.

- ^ Rodger, James (2 May 2018). "Benjamin Zephaniah admits to hitting ex-girlfriend". BirminghamLive. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ Balloo, Stephanie (11 July 2018). "Police paid £300,000 to the family of man who died in custody". Birmingham Live. Archived from the original on 18 January 2022. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

Birmingham poet Benjamin Zephaniah, had said: "We have been asking questions for 10 years, protesting for 10 years, writing letters, and poems, and statements for 10 years, but most of all we have been collectively grieving for 10 years.

- ^ Youle, Emma (30 April 2021). "'That's What They Do To Us': Benjamin Zephaniah On His Experiences Of Police Racism". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 14 December 2023. Retrieved 14 December 2023.

- ^ Zephaniah, Benjamin (7 August 2012). "Has Snoop Dogg seen the Rastafari light, or is this just a midlife crisis?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- ^ Wilmers, Mischa (4 February 2014). "Benjamin Zephaniah: 'It is my duty to help and inspire'". New Internationalist. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ O'Connor, Joanne (6 May 2018). "Benjamin Zephaniah: 'I don't want to grow old alone'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 May 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ Zephaniah, Benjamin (18 May 2009). "Villa fans, violence and me". The Observer. Archived from the original on 11 December 2023. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ "A Poet Called Benjamin Zephaniah". Benjaminzephaniah.com. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- ^ Aston Villa FC (7 December 2023). "Tribute to Benjamin Zephaniah". avfc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 11 December 2023. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ "Aston Villa pay homage to lifelong fan Benjamin Zephaniah". The Voice. 8 December 2023. Archived from the original on 8 December 2023. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ Farber, Alex (7 December 2023). "Benjamin Zephaniah, writer and poet, dies aged 65". The Times. Archived from the original on 7 December 2023.

- ^ Creamer, Ella (7 December 2023). "British poet Benjamin Zephaniah dies aged 65". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 9 December 2023. Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ Armatrading, Joan [@ArmatradingJoan] (7 December 2023). "I am in shock. Benjamin Zephaniah has died age 65. What a thoughtful, kind and caring man he was. The world has lost a poet, an intellectual and a cultural revolutionary. I have lost a great friend" (Tweet). Retrieved 8 December 2023 – via Twitter.

- ^ Question Time [@bbcquestiontime] (7 December 2023). "'He was an all round, just tremendous bloke' Fiona Bruce pays tribute to poet Benjamin Zephaniah, a regular panellist on Question Time, who she says she had 'huge affection and respect for'" (Tweet). Retrieved 8 December 2023 – via Twitter.

- ^ Pearce, Vanessa; Giles Latcham (8 December 2023). "Benjamin Zephaniah: The James Brown of dub poetry". Archived from the original on 9 December 2023. Retrieved 8 December 2023 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ Sinclair, Luke (7 December 2023). "Renowned British poet and Peaky Blinders star, Benjamin Zephaniah, passes away at 65". Herald.Wales. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ "Benjamin Zephaniah: Ode to Aston Villa". BBC Sport. 22 July 2015. Archived from the original on 11 December 2023. Retrieved 11 December 2023 – via YouTube.

- ^ Browning, Oliver (10 December 2023). "Aston Villa pay moving tribute to poet Benjamin Zephaniah ahead of Arsenal win". The Independent. Archived from the original on 11 December 2023. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ^ O'Connor, Roisin (28 December 2023). "Benjamin Zephaniah fans asked to plant flowers in poet's memory as funeral takes place". The Independent.

- ^ Badshah, Nadeem (28 December 2023). "Benjamin Zephaniah laid to rest in private funeral". The Guardian.

- ^ Murray, Jessica (5 April 2024). "Apology after Benjamin Zephaniah mural painted over in Birmingham". The Guardian.

- ^ Haynes, Jane (5 April 2024). "Zephaniah family frustration over mural that 'took hours to create and minutes to destroy' in error". Birmingham Live. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ Haynes, Jane (2 April 2024). "Backlash as Hockley mural of beloved Benjamin Zephaniah painted over". Birmingham Live. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ Dawkins, Andrew (4 April 2024). "Apology after Benjamin Zephaniah mural removed". BBC News, West Midlands. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ Eichler, William (8 April 2024). "Council contractor apologises after painting over Zephaniah mural". LocalGov. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ Thorpe, Vanessa (7 April 2024). "Birmingham mural honours legacy of poet giant Benjamin Zephaniah". The Observer.

- ^ "Benjamin Zephaniah mural: Tribute to be unveiled for Birmingham writer and poet". Newsround. CBBC. 8 April 2024. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ "The Life and Rhymes of Benjamin Zephaniah". BBC Radio 4. April 2024. Retrieved 9 April 2024.

- ^ Sudan, Richard (7 September 2024). "'His love was for everybody': emotional tributes as Brunel University unveils plaque to Benjamin Zephaniah". Voice Online. Retrieved 9 January 2025.

- ^ Shukla, Anu (15 April 2025). "'His delivery cut through class barriers': Moby, Mala and other musicians on working with Benjamin Zephaniah". The Guardian.

- ^ "Funky Turkeys" Archived 10 December 2023 at the Wayback Machine, Penguin.

- ^ Zephaniah, Benjamin (2014). Terror Kid. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1471401770.

- ^ Zephaniah, Benjamin (7 April 2022). We Sang Across the Sea: The Empire Windrush and Me. Illustrated by Onyinye Iwu. Scholastic. ISBN 978-0702311161.

- ^ Lazell, Barry (1997), Indie Hits 1980–1989, Cherry Red Books, ISBN 0-9517206-9-4.

- ^ "Interview: Pat D & Lady Paradox". The Find Mag. 22 November 2009.

- ^ Coultate, Aaron (28 August 2013). "Luke Slater presents L.B. Dub Corp album". Resident Advisor. Retrieved 20 February 2025.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Benjamin Zephaniah at IMDb

- Benjamin Zephaniah discography at Discogs

- "British Jamaican Rastafarian Writer, Dub Poet Benjamin Zephaniah on Poetry, Politics and Revolution", 20 September 2010 – video report by Democracy Now!

- "'A hero to millions': Benjamin Zephaniah remembered by Michael Rosen, Kae Tempest and more", The Guardian, 7 December 2023.

- Deirdre Osborne, "Remembering Benjamin Zephaniah", Goldsmiths University of London, 7 December 2023.

- Portraits of Benjamin Zephaniah at the National Portrait Gallery, London

Benjamin Zephaniah

View on GrokipediaEarly Life

Childhood and Family Background

Benjamin Zephaniah was born Benjamin Obadiah Iqbal Springer on 15 April 1958 in the Handsworth district of Birmingham, England, to immigrant parents from the Caribbean: his father, a postman originally from Barbados, and his mother, a nurse from Jamaica.[10][11] He grew up as one of eight children in a large working-class household strained by poverty, where siblings shared rudimentary facilities such as a single tin bath for bathing.[12][5] Handsworth, a multicultural enclave with strong Jamaican ties that Zephaniah later called the "Jamaican capital of Europe," immersed him in his family's heritage of oral storytelling, reggae rhythms, and dub music traditions imported from Jamaica.[13][14] These elements, alongside early exposure to Caribbean poetry recited by relatives and tapes of Jamaican artists, laid foundational influences on his rhythmic, performance-oriented style, though formal adoption of Rastafarianism came later in adolescence.[15] The family's economic precarity and domestic challenges were compounded by the broader context of 1960s and 1970s Birmingham, a period of acute urban poverty, industrial decline, and escalating racial hostilities toward Caribbean immigrants, including street violence and discrimination that tested young Zephaniah's resilience.[16][17] These experiences amid familial instability—marked by the strains of supporting eight children on modest wages—instilled an early awareness of social inequities and cultural defiance.[12][5]Education Challenges and Early Interests

Zephaniah encountered substantial difficulties in formal education stemming from undiagnosed dyslexia, which impaired his ability to read and write. By age 13, he had been excluded from multiple schools, culminating in expulsion from Broadway School in Birmingham for persistent behavioral problems, including intellectual disputes with teachers that were exacerbated by his unrecognized learning challenges.[18][19][20] Lacking conventional literacy skills upon leaving school, Zephaniah turned to self-directed pursuits, immersing himself in reggae music as a primary influence, particularly the lyrics and rhythms of Bob Marley, whose work he admired from adolescence and even corresponded with directly. This exposure fostered his interest in rhythmic language and performance, leading him to experiment with spoken-word expressions amid Birmingham's dynamic multicultural street environment in Handsworth.[21][22] In this context of urban youth pressures, including temptations toward petty crime and gang affiliations, poetry emerged as a constructive channel for Zephaniah's energies, enabling him to articulate experiences of marginalization and creativity without deeper criminal immersion, though he initially engaged in minor offenses and faced institutional responses like approved schooling.[23][19][24]Literary Career

Development as a Dub Poet

Zephaniah commenced his performances as a dub poet in Birmingham during the 1970s, delivering recitations in local pubs, festivals, and churches without formal training, often starting as early as age 11.[13] These amateur outings evolved from self-taught experimentation, fusing spoken verse with reggae beats and Rastafarian oral traditions imported via Jamaican immigrant communities, prioritizing rhythmic improvisation over scripted literacy to engage audiences directly.[25] By the late 1970s, his style had coalesced into dub poetry—a performative genre originating in Jamaica around that decade—characterized by "verbal riddim" where tongue and body mimic dub music's echoic, bass-heavy pulses, rendering poetry a live, communal act unbound by page constraints.[26][27] This innovation distinguished Zephaniah's work by subverting literary hierarchies, favoring accessibility and political urgency over elitist conventions; he eschewed musical accompaniment in many instances to spotlight unadorned voice as instrument, making dub a tool for immediate critique rather than archival text.[25][23] Rooted in reggae's militant ethos and Rastafarian defiance, his delivery incorporated patois-inflected English to evoke resistance, transforming pubs into arenas for voicing lived realities.[14] Early themes fixated on urban squalor in post-industrial Handsworth, fractured ethnic identities amid racial tensions, and grassroots pushback against systemic marginalization, as evidenced in his raw, beat-driven rants that galvanized Black British youth.[28][29] Transitioning from regional obscurity, Zephaniah relocated to London around 1980 at age 22, where intensified gigs propelled his ascent; his debut collection Pen Rhythm (1980) captured this oral essence in print for the first time, followed by broader anthology inclusions that amplified dub's reach beyond live circuits.[1] By 1983, television appearances and collaborations underscored his maturation into a nationally acclaimed figure, cementing dub poetry's viability as a subversive, anti-establishment medium challenging canonical gatekeeping.[30][31]Key Poetry Collections and Themes

Zephaniah's early poetry collections, beginning with Pen Rhythm published in 1980, established his dub poetry style rooted in performance and oral tradition.[32] This debut featured rhythmic verses drawn from Birmingham's working-class immigrant communities, emphasizing spoken delivery over printed form. Subsequent works like The Dread Affair: Collected Poems (1985) compiled prior pieces, incorporating illustrations and focusing on raw depictions of street life and resistance to conformity.[33] [34] A hallmark of Zephaniah's approach was the use of phonetic spelling to transcribe Jamaican Creole dialect, such as rendering "the" as "de" or "you" as "yu," which mirrored natural speech patterns and challenged the dominance of standard English in literature.[35] This technique, evident across collections like City Psalms (1992), preserved cultural authenticity while critiquing linguistic imposition as a tool of cultural erasure.[36] City Psalms showcased poems such as "Dis Poetry," which satirized elitist literary norms, and "Money," exploring economic disparities, blending urban grit with rhythmic accessibility.[37] Recurring themes centered on personal agency amid systemic barriers, including skepticism toward institutional authority and advocacy for self-reliance in the face of poverty and prejudice.[38] Poems often highlighted racism's causal role in social fragmentation, as in critiques of exploitative "race industries" that profited from minority suffering without addressing root inequalities.[39] Rastafarian-influenced motifs promoted natural living and communal ethics, rejecting consumerism and state overreach as drivers of alienation.[26] Later volumes like Propa Propaganda (1996) and Too Black, Too Strong (2001) extended these motifs to broader injustices, including state violence and minority rights, maintaining a focus on autobiographical realism over abstraction.[40] While Zephaniah's live readings drew diverse crowds and boosted post-1990s poetry interest, his non-conventional form garnered limited formal literary recognition, with critics noting its divergence from canonical standards as a barrier to mainstream awards.[41] [42]Novels and Prose Works

Zephaniah's debut novel, Face, published in 1999, centers on Martin Bishop, a confident teenage boy from an inner-city London background whose life unravels after a joyriding escapade culminates in a car crash that leaves him severely disfigured.[43] The plot traces Martin's physical recovery and psychological reckoning, where the causal chain of his reckless decisions forces confrontation with superficial judgments, bullying, and his own diminished self-image, underscoring individual agency in overcoming adversity rather than reliance on external validation.[43] Themes of identity reconstruction and anti-racism emerge through Martin's interactions, as he navigates prejudice tied to his altered appearance and ethnic heritage, ultimately rebuilding relationships via personal determination.[44] In 2001, Zephaniah released Refugee Boy, drawing from the Eritrean-Ethiopian War of 1998–2000, which displaced thousands along contested borders like Badme.[45] The narrative follows Alem Kelo, a 14-year-old sent from his war-torn home to London by his father for safety, only to face abandonment and entanglement in the UK's asylum bureaucracy after his father's return.[46] Alem's ordeal highlights the tangible perils of cross-border conflict—forced separation, survival instincts amid violence—and the procedural delays in asylum processing, where individual adaptation to hostile environments, such as foster care and schoolyard xenophobia, drives the story over idealized integration narratives.[47] Empirical parallels to real Eritrean refugee cases underscore the novel's grounding in documented border displacements and policy frictions, emphasizing causal disruptions from geopolitical strife on personal trajectories.[45][46] Subsequent novels like Teacher's Dead (2007) and Terror Kid (2014) extend these motifs into educational dysfunction and counter-terrorism scrutiny, respectively, maintaining a focus on youthful protagonists grappling with systemic barriers through self-reliant navigation.[32] Zephaniah's prose across these works employs straightforward syntax and vernacular dialogue, mirroring his performance poetry origins to prioritize accessibility and rhythmic flow, though some analyses note its unadorned structure limits literary depth in favor of plot momentum.[43] This style facilitates exploration of migration's concrete costs—economic precarity, cultural dislocation—and identity forged via pragmatic choices, sidestepping abstracted multiculturalism for verifiable individual strategies amid institutional inertia.[47]Children's Books and Broader Writings

Zephaniah's debut children's poetry collection, Talking Turkeys!, released in 1994 by Viking Children's Books, marked his entry into youth literature with dub-infused verses that challenged authority while promoting animal welfare and ecological awareness.[48][49] The work's rhythmic, oral style drew from his performance background, rendering complex ideas like anti-racism and self-reliance accessible without overt lecturing.[50] Poems such as the title piece urged empathy toward animals during holidays, framing ethical choices as extensions of personal liberty.[51] Follow-up collections, including Wicked World! in 1999 and Funky Chickens, sustained this approach by weaving global inequities and environmental stewardship into playful narratives, fostering independent ethical reasoning among readers aged 8–12.[52] These volumes prioritized verifiable observations over prescriptive morals, using humor and repetition to highlight causal links between human actions and natural consequences, such as habitat destruction.[53] Their reception evidenced strong youth appeal, with Talking Turkeys! achieving immediate bestseller status and enduring sales through multiple editions.[54] Beyond poetry, Zephaniah's essays and autobiographical reflections addressed self-directed learning, drawing from his dyslexia diagnosis in adulthood after formal schooling failures.[18] He described dyslexia not as an inherent flaw but as a spur to creative adaptation, where intuitive pattern recognition bypassed rote memorization deficits in institutional settings.[55] In pieces like his 2015 Guardian contribution, he advocated autodidactic strategies—such as verbal composition and iterative refinement—for youth, positioning them as triumphs of raw cognitive agency over standardized education's limitations.[18] These writings implicitly critiqued systemic overreach by emphasizing empirical self-testing of ideas, aligning with his broader output's stress on unmediated inquiry.[56]Musical Contributions

Albums and Recordings

Benjamin Zephaniah's recordings emphasized dub poetry set to reggae and dub backings, integrating his spoken-word style with rhythmic instrumentation to amplify themes of social injustice, anti-imperialism, and personal liberation drawn from his poetic works. His discography reflects a commitment to raw, message-driven production rather than mainstream commercial appeal, often involving live musicians or dub specialists for an authentic roots sound. Early releases prioritized political urgency, such as opposition to apartheid, while later efforts incorporated heavier dub effects and broader collaborations.[57][58] The debut album Rasta, released in 1982 on Upright Records, marked Zephaniah's entry into recorded music and featured the Wailers' first post-Bob Marley session, including tracks like "Free South Africa" decrying apartheid and "13 Dead" referencing urban unrest.[59] This self-titled effort captured a DIY ethos through minimalistic production focused on vocal delivery over sparse reggae beats, achieving niche influence in dub poetry circles without significant chart penetration.[58] Subsequent works expanded this fusion, as seen in Us An Dem (1990, Mango Records), which blended dub poetry with tracks addressing gun violence ("Everybody Hav a Gun"), religious conflict ("Religious War"), and systemic divides ("Us and Dem"), produced by Paul "Groucho" Smyke for a more structured yet politically charged sound.[60][61] The album maintained thematic continuity with Zephaniah's writings by prioritizing lyrical critique over polished hooks, contributing to his reputation in underground reggae scenes despite limited verifiable commercial metrics.[62] Later albums like Back to Roots (1995) featured laid-back roots reggae dub poems backed by live instrumentation on topics including solidarity ("One Tribe") and resistance ("Self Defence"), while Belly of De Beast (1996), produced by Mad Professor, delivered heavy dance dub with bass-heavy mixes on issues like cultural awakening ("Wake Up") and conflict ("War").[63][64] Naked (2000) shifted toward poetry over diverse beats crafted by drummer Trevor Morais, incorporating contributions from artists such as Dennis Bovell and Howard Jones, and included a companion lyrics booklet to underscore textual primacy.[65] These recordings exemplified Zephaniah's preference for collaborative, ethos-driven production that echoed his poetry's directness, fostering influence in alternative music communities over broad market success.[58]| Album Title | Release Year | Label | Key Production Notes and Themes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rasta | 1982 | Upright | Wailers collaboration; anti-apartheid tracks like "Free South Africa"; raw dub poetry focus.[59] |

| Us An Dem | 1990 | Mango | Paul "Groucho" Smyke production; social division, violence themes.[61] |

| Back to Roots | 1995 | Acid Jazz | Live musicians; roots dub on unity and defense.[63] |

| Belly of De Beast | 1996 | Ariwa | Mad Professor production; heavy dub, cultural and war critiques.[64] |

| Naked | 2000 | Papayo | Trevor Morais beats with guest artists; poetry-centric with lyrics book.[65] |

Collaborations and Musical Style

Zephaniah's notable musical collaborations often bridged his dub poetry with reggae traditions, exemplified by his 1982 partnership with The Wailers on the track "Free South Africa," recorded at Bob Marley's Tuff Gong Studios in Kingston, Jamaica—the band's first performance since Marley's death earlier that year.[1] This work extended Jamaican reggae's protest heritage, rooted in anti-apartheid advocacy, into a British context by layering Zephaniah's spoken-word critique over the Wailers' rhythmic foundation, directly supporting Nelson Mandela's cause as he later acknowledged hearing the tribute during imprisonment.[4] Later collaborations included "Empire" with Sinéad O'Connor, fusing his patois-inflected verses with her vocals to address colonial legacies, and electronic crossovers such as "Word & Sound" with Natty and Mala, which integrated dub poetry into UK bass and jungle elements.[66] These partnerships causally linked Zephaniah's output to Jamaican influences while adapting them for broader anti-establishment messaging, though they prioritized ideological alignment over commercial viability.[67] Zephaniah's musical style centered on dub poetry, a form originating in Jamaica that combines performative spoken word with reggae and dub instrumentation, emphasizing unrefined authenticity derived from street-level oral traditions rather than studio polish.[10] His lyrics, delivered in patois with call-and-response structures, drew directly from Rastafarian rhythms and Birmingham's multicultural soundscape, rejecting mainstream production techniques to preserve causal fidelity to raw, communal expression—evident in live festival sets that amplified visibility without compromising anti-commercial principles.[26] This approach influenced the UK dub scene by injecting political urgency into spoken-word performance, positioning Zephaniah as a pioneer who elevated dub poetry's accessibility yet limited crossover appeal due to deliberate avoidance of sanitized formats favored by industry gatekeepers.[31] Empirical metrics of reach, such as repeated Glastonbury appearances in the 1980s and 1990s, underscore how his style fostered niche cult followings tied to ideological refusals, rather than chart dominance.[1]Performing Arts Involvement

Acting Roles in Film and Television

Zephaniah's acting career featured selective appearances in British television and film, often emphasizing characters from marginalized urban communities that aligned with his Birmingham roots and Rastafarian perspective. His roles typically involved brief but impactful portrayals, prioritizing authenticity over volume, as evidenced by his limited but memorable credits spanning the 1980s to 2010s.[68] In the crime drama Peaky Blinders (2013–2022), Zephaniah portrayed Jeremiah "Jimmy" Jesus, a Jamaican-born preacher and confidant to protagonist Tommy Shelby, across eight episodes in series 4 (2017) and series 5 (2019).[69][70] The character served as a spiritual advisor to the Shelby gang, reflecting early 20th-century immigrant experiences in Birmingham's underclass, with Zephaniah's performance noted for its rhythmic delivery informed by his dub poetry background.[71] This role marked his most prominent on-screen presence, leveraging his persona to depict resilience amid historical gang violence and social exclusion.[72] Earlier credits included Rufus in the 1988 television film Didn't You Kill My Brother?, a drama exploring Rastafarian family dynamics and police confrontation in London.[68] He also appeared as Moses in the 1989 French film Farendj, portraying a figure navigating displacement.[73] Minor television parts encompassed a vagrant in The Bill and a derelict man in EastEnders, alongside God Complex in the short Zen Motoring (year unspecified).[74]| Year | Title | Role | Medium |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1988 | Didn't You Kill My Brother? | Rufus | TV Film[68] |

| 1989 | Farendj | Moses | Film[73] |

| 2011–2013 | Mad Dogs | Unspecified | TV Series[73] |

| 2017–2019 | Peaky Blinders (Series 4–5) | Jeremiah Jesus | TV Series[69] |

Media Appearances and Public Performances

Zephaniah served as Writer in Residence for Liverpool from 1988 to 1990, during which he conducted public poetry readings and workshops, including performances at schools and open houses that emphasized direct interaction with audiences on themes of urban life and identity.[1][75] On December 2, 1988, as part of this role, he performed his poem "Inna Liverpool" for ITN news, capturing local dialect and experiences in an unrehearsed style that highlighted his dub poetry roots over scripted delivery.[76] In media engagements, Zephaniah appeared in BBC interviews that showcased his spoken-word approach, such as a 2004 broadcast on BBC Sounds where he recounted personal anecdotes from his childhood and creative development without adhering to a formal script.[77] He also featured in an extended discussion on BBC Radio 4's The Verb, focusing on his poetic process and live performance techniques.[78] These appearances often blended ideological commentary with rhythmic recitation, drawing occasional critique for their didactic tone in prioritizing message over entertainment, as noted in reflections on his advocacy-driven style.[79] Public performances extended to collaborative readings, including a 2009 BBC Poetry Season segment where Zephaniah recited "The British" alongside students, demonstrating his emphasis on accessible, interactive poetry dissemination rather than polished production.[80] Such events, verifiable through broadcast archives and residency records, underscored his preference for unmediated audience engagement, distinguishing these from rehearsed acting roles by their improvisational and exhortative elements.[81]Activism and Ideology

Animal Rights Advocacy and Veganism

Benjamin Zephaniah adopted a vegan diet at age 13 in the early 1970s, influenced by Rastafarian principles emphasizing an ital lifestyle of plant-based eating to maintain bodily purity and harmony with nature.[82][83] He later described his initial motivation as opposition to animal suffering and exploitation, framing it as a rejection of enslavement akin to historical human injustices, rather than primarily health or environmental concerns.[84][85] This commitment persisted lifelong, with Zephaniah serving as an honorary patron of the Vegan Society and publicly testifying in interviews and writings that veganism aligned ethical imperatives against violence toward sentient beings, including links to personal health benefits from avoiding processed animal products.[86][87] His advocacy included collaborations with organizations like PETA, for which he featured in campaigns highlighting animal cruelty, such as public statements equating meat consumption to murder and promoting vegan alternatives.[88] Zephaniah supported Animal Aid for decades, critiqued practices like the UK's badger cull in 2023, and endorsed anti-blood sports efforts, including bans on foxhunting through groups like the Irish Council Against Blood Sports.[89][90][91] While no records detail personal farm animal rescues or direct policy lobbying by Zephaniah, his public platform amplified calls for systemic change, integrating animal ethics into broader anti-exploitation narratives in poetry and media appearances.[92] Empirically, Zephaniah's efforts raised cultural awareness of veganism, inspiring audiences through accessible performances and endorsements that correlated with growing UK vegan identification from under 1% in the 1970s to about 1.5% by 2023, though causation remains indirect amid wider trends like media exposure.[93] However, measurable policy outcomes were limited; despite support for initiatives like the 2004 Hunting Act, no major legislative shifts in farm animal welfare or meat reduction policies can be directly attributed to his advocacy, as UK animal agriculture output rose 10-15% in volume from 2000-2020 per government data.[94] Critics, including some in media analyses, noted a potential selective emphasis on animal over human-linked issues, such as how animal agriculture in impoverished regions sustains livelihoods amid poverty cycles, though Zephaniah countered by analogizing animal use to perpetuating dominance hierarchies that exacerbate human inequities.[95][85] This reflects a causal tension: individual ethical consistency advanced personal and niche influence but yielded marginal systemic impact against entrenched economic incentives in global meat production, which supplies protein to billions without viable short-term alternatives for food-insecure populations.Anti-Racism Efforts and Social Campaigns

Zephaniah drew from his personal experiences of repeated arrests in the 1970s, including convictions for theft and time in borstal, to critique police practices disproportionately targeting black youth under laws like the "sus" provision.[19][79] These encounters, which he described as involving framing and brutality, informed his lifelong opposition to stop-and-search abuses, though he acknowledged his own involvement in crimes during that period.[96] In the 1980s, Zephaniah actively supported the anti-apartheid movement through performances at demonstrations, youth camps, and events like the Artists Against Apartheid festival featuring South African musicians.[97][98] He also appeared at international solidarity concerts, such as the 1989 event at Gdansk Shipyard in Poland, using poetry to highlight racial oppression in South Africa.[99] Zephaniah campaigned against stop-and-search disparities later in his career, launching the "Stop and Search on Trial" initiative in 2014 as patron of the Newham Monitoring Project, a London-based group documenting police misconduct against ethnic minorities.[100][101] The effort sought to challenge disproportionate targeting, citing his cousin's death in custody and ongoing data showing black individuals stopped at rates five times higher than whites in some areas, though quantifiable policy impacts from the campaign remain unestablished.[102] Following the 2011 England riots, Zephaniah's poem "Why You Don't Riot" emphasized personal and community factors in preventing unrest, noting that individuals with stable employment, housing, and sustenance were less prone to participation, implicitly prioritizing internal self-regulation over exclusive attribution to state failures.[103] This stance contrasted with narratives framing riots solely as responses to systemic racism, reflecting his view that economic pressures and individual choices causally underpin such events. To satirize layered prejudices, Zephaniah wore a T-shirt emblazoned with "More blacks, more dogs, more Irish"—a phrase echoing 1970s tabloid rhetoric—during a performance at the Whitby Musicport festival in the 2010s, aiming to provoke reflection on historical dismissals of marginalized groups.[104] While Zephaniah's advocacy amplified visibility of interracial tensions, it correlated with no empirically verifiable reductions in racial policing disparities, which UK statistics show persisting into the 2020s with black arrest rates remaining elevated.[102] His work occasionally addressed intra-ethnic conflicts, as in critiques of Indian oppression of black communities in Britain, underscoring causal complexities beyond white racism alone, yet such nuances were less central than external critiques in his public campaigns.[105]Political Positions and Institutional Critiques