Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Brass instrument

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2024) |

A brass instrument is a musical instrument that produces sound by sympathetic vibration of air in a tubular resonator in sympathy with the vibration of the player's lips. The term labrosone, from Latin elements meaning "lip" and "sound", is also used for the group, since instruments employing this "lip reed" method of sound production can be made from other materials like wood or animal horn, particularly early or traditional instruments such as the cornett, alphorn or shofar.[1]

There are several factors involved in producing different pitches on a brass instrument. Slides, valves, crooks (though they are rarely used today), or keys are used to change vibratory length of tubing, thus changing the available harmonic series, while the player's embouchure, lip tension and air flow serve to select the specific harmonic produced from the available series.

The view of most scholars (see organology) is that the term "brass instrument" should be defined by the way the sound is made, as above, and not by whether the instrument is actually made of brass. Thus one finds brass instruments made of wood, like the alphorn, the cornett, the serpent and the didgeridoo, while some woodwind instruments are made of brass, like the saxophone.

Families

[edit]Modern brass instruments generally come in one of two families:

- Valved brass instruments use a set of valves (typically three or four but as many as seven or more in some cases) operated by the player's fingers that introduce additional tubing, or crooks, into the instrument, changing its overall length. This family includes all of the modern brass instruments except the trombone: the trumpet, horn (also called French horn), euphonium, and tuba, as well as the cornet, flugelhorn, tenor horn (alto horn), baritone horn, sousaphone, and the mellophone. As valved instruments are predominant among the brasses today, a more thorough discussion of their workings can be found below. The valves are usually piston valves, but can be rotary valves; the latter are the norm for the horn (except in France) and are also common on the tuba.

- Slide brass instruments use a slide to change the length of tubing. The main instruments in this category are the trombone family, though valve trombones are occasionally used, especially in jazz. The trombone family's ancestor, the sackbut, and the folk instrument bazooka are also in the slide family.

| Part of a series on |

| Musical instruments |

|---|

There are two other families that have, in general, become functionally obsolete for practical purposes. Instruments of both types, however, are sometimes used for period-instrument performances of Baroque or Classical pieces. In more modern compositions, they are occasionally used for their intonation or tone color.

- Natural brass instruments only play notes in the instrument's harmonic series. These include the bugle and older variants of the trumpet and horn. The trumpet was a natural brass instrument prior to about 1795, and the horn before about 1820. In the 18th century, makers developed interchangeable crooks of different lengths, which let players use a single instrument in more than one key. Natural instruments are still played for period performances and some ceremonial functions, and are occasionally found in more modern scores, such as those by Richard Wagner and Richard Strauss.

- Keyed or Fingered brass instruments used holes along the body of the instrument, which were covered by fingers or by finger-operated pads (keys) in a similar way to a woodwind instrument. These included the cornett, serpent, ophicleide, keyed bugle and keyed trumpet. They are more difficult to play than valved instruments.

Bore taper and diameter

[edit]Brass instruments may also be characterised by two generalizations about geometry of the bore, that is, the tubing between the mouthpiece and the flaring of the tubing into the bell. Those two generalizations are with regard to

- the degree of taper or conicity of the bore and

- the diameter of the bore with respect to its length.

Cylindrical vs. conical bore

[edit]While all modern valved and slide brass instruments consist in part of conical and in part of cylindrical tubing, they are divided as follows:

- Cylindrical bore brass instruments are those in which approximately constant diameter tubing predominates. Cylindrical bore brass instruments are generally perceived as having a brighter, more penetrating tone quality compared to conical bore brass instruments. The trumpet, and all trombones are cylindrical bore. In particular, the slide design of the trombone necessitates this.

- Conical bore brass instruments are those in which tubing of constantly increasing diameter predominates. Conical bore instruments are generally perceived as having a more mellow tone quality than the cylindrical bore brass instruments. The "British brass band" group of instruments fall into this category. This includes the flugelhorn, cornet, tenor horn (alto horn), baritone horn, horn, euphonium and tuba. Some conical bore brass instruments are more conical than others. For example, the flugelhorn differs from the cornet by having a higher percentage of its tubing length conical than does the cornet, in addition to possessing a wider bore than the cornet. In the 1910s and 1920s, the E. A. Couturier company built brass band instruments utilizing a patent for a continuous conical bore without cylindrical portions even for the valves or tuning slide.

Whole-tube vs. half-tube

[edit]The resonances of a brass instrument resemble a harmonic series, with the exception of the lowest resonance, which is significantly lower than the fundamental frequency of the series that the other resonances are overtones of.[2] Depending on the instrument and the skill of the player, the missing fundamental of the series can still be played as a pedal tone, which relies mainly on vibration at the overtone frequencies to produce the fundamental pitch.[3][4] The bore diameter in relation to length determines whether the fundamental tone or the first overtone is the lowest partial practically available to the player in terms of playability and musicality, dividing brass instruments into whole-tube and half-tube instruments. These terms stem from a comparison to organ pipes, which produce the same pitch as the fundamental pedal tone of a brass instrument of equal length.[5]

Neither the horns nor the trumpet could produce the 1st note of the harmonic series ... A horn giving the C of an open 8 ft organ pipe had to be 16 ft (5 m). long. Half its length was practically useless ... it was found that if the calibre of tube was sufficiently enlarged in proportion to its length, the instrument could be relied upon to give its fundamental note in all normal circumstances. – Cecil Forsyth, Orchestration, p. 86[6]

- Whole-tube instruments have larger bores in relation to tubing length, and can play the fundamental tone with ease and precision. The tuba and euphonium are examples of whole-tube brass instruments.

- Half-tube instruments have smaller bores in relation to tubing length and cannot easily or accurately play the fundamental tone. The second partial (first overtone) is the lowest note of each tubing length practical to play on half-tube instruments. The trumpet and horn are examples of half-tube brass instruments.

Other brass instruments

[edit]The instruments in this list fall for various reasons outside the scope of much of the discussion above regarding families of brass instruments.

- Alphorn (wood)

- Conch (shell)

- Didgeridoo (wood, Australia)

- Natural horn (no valves or slides—except tuning crooks in some cases)

- Jazzophone

- Keyed bugle (keyed brass)

- Keyed trumpet (keyed brass)

- Serpent (keyed brass)

- Ophicleide (keyed brass)

- Shofar (animal horn)

- Vladimirskiy rozhok (wood, Russia)

- Vuvuzela (simple short horn, origins disputed but achieved fame or notoriety through many plastic examples in the 2010 World Cup)

- Lur

Valves

[edit]

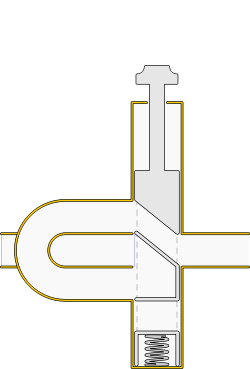

Valves are used to change the length of tubing of a brass instrument allowing the player to reach the notes of various harmonic series. Each valve pressed diverts the air stream through additional tubing, individually or in conjunction with other valves. This lengthens the vibrating air column thus lowering the fundamental tone and associated harmonic series produced by the instrument. Designs exist, although rare, in which this behaviour is reversed, i.e., pressing a valve removes a length of tubing rather than adding one. One modern example of such an ascending valve is the Yamaha YSL-350C trombone,[7] in which the extra valve tubing is normally engaged to pitch the instrument in B♭, and pressing the thumb lever removes a whole step to pitch the instrument in C. Valves require regular lubrication.

A core standard valve layout based on the action of three valves had become almost universal by (at latest) 1864 as witnessed by Arban's method published in that year. The effect of a particular combination of valves may be seen in the table below. This table is correct for the core three-valve layout on almost any modern valved brass instrument. The most common four-valve layout is a superset of the well-established three-valve layout and is noted in the table, despite the exposition of four-valve and also five-valve systems (the latter used on the tuba) being incomplete in this article.

| Valve combination | Effect on pitch | Interval | Tuning problems |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1⁄2 step | Minor second | |

| 1 | 1 step | Major second | |

| 1+2 or 3 | 1+1⁄2 step | Minor third | Very slightly sharp |

| 2+3 | 2 steps | Major third | Slightly sharp |

| 1+3 or 4 | 2+1⁄2 steps | Perfect fourth | Sharp (1+3 only) |

| 1+2+3 or 2+4 | 3 steps | Tritone | Very sharp (1+2+3 only) |

| 1+4 | 3+1⁄2 steps | Perfect fifth | |

| 1+2+4 or 3+4 | 4 steps | Augmented fifth | Flat |

| 2+3+4 | 4+1⁄2 steps | Major sixth | Slightly sharp |

| 1+3+4 | 5 steps | Minor seventh | Sharp |

| 1+2+3+4 | 5+1⁄2 steps | Major seventh | Very sharp |

Tuning

[edit]Since valves lower the pitch, a valve that makes a pitch too low (flat) creates an interval wider than desired, while a valve that plays sharp creates an interval narrower than desired. Intonation deficiencies of brass instruments that are independent of the tuning or temperament system are inherent in the physics of the most popular valve design, which uses a small number of valves in combination to avoid redundant and heavy lengths of tubing[8] (this is entirely separate from the slight deficiencies between Western music's dominant equal (even) temperament system and the just (not equal) temperament of the harmonic series itself). Since each lengthening of the tubing has an inversely proportional effect on pitch (Pitch of brass instruments), while pitch perception is logarithmic, there is no way for a simple, uncompensated addition of length to be correct in every combination when compared with the pitches of the open tubing and the other valves.[9]

Absolute tube length

[edit]For example, given a length of tubing equaling 100 units of length when open, one may obtain the following tuning discrepancies:

| Valve(s) | Desired pitch | Necessary valve length | Component tubing length | Difference | Slide positions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open tubing | A♯/B♭ | 0 | – | – | 1 |

| 2 | A | 5.9 | – | – | 2 |

| 1 | G♯/A♭ | 12.2 | – | – | 3 |

| 1+2 or 3 | G | 18.9 | 18.1 | 0.8 | 4 |

| 2+3 | F♯/G♭ | 25.9 | 24.8 | 1.1 | 5 |

| 1+3 or 4 | F | 33.5 | 31.1 | 2.4 | 6 or T |

| 1+2+3 or 2+4 | E | 41.4 | 37 | 4.4 | 7 or T+2 |

| 1+4 | D♯/E♭ | – | 45.7 | – | T+3 |

| 1+2+4 or 3+4 | D | – | 52.4 | – | T+4 |

| 2+3+4 | C♯/D♭ | – | 58.3 | – | T+5 |

| 1+3+4 | C | – | 64.6 | – | T+6 |

| 1+2+3+4 | B | – | 70.5 | – | T+7 |

Playing notes using valves (notably 1st + 3rd and 1st + 2nd + 3rd) requires compensation to adjust the tuning appropriately, either by the player's lip-and-breath control, via mechanical assistance of some sort, or, in the case of horns, by the position of the stopping hand in the bell. 'T' stands for trigger on a trombone.

Relative tube length

[edit]Traditionally, the valves lower the pitch of the instrument by adding extra lengths of tubing based on just intonation:[10]

- 1st valve: 1⁄8 of main tube, making an interval of 9:8, a pythagorean major second

- 2nd valve: 1⁄15 of main tube, making an interval of 16:15, a just minor second

- 3rd valve: 1⁄5 of main tube, making an interval of 6:5, a just minor third

Combining the valves and the harmonics of the instrument leads to the following ratios and comparisons to 12-tone equal tuning and to a common five-limit tuning in C:

| Valves | Har- monic |

Note | Ratio | Cents | Cents from 12ET |

Just tuning |

Cents from just |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ○○○ | 2 | C | 1:1 | 0 | 0 | 1:1 | 0 |

| ●●● | 3 | C♯/D♭ | 180:167 | 130 | 30 | 16:15 | 18 |

| ●○● | 3 | D | 60:53 | 215 | 15 | 9:8 | 11 |

| ○●● | 3 | D♯/E♭ | 45:38 | 293 | −7 | 6:5 | −23 |

| ●●○ | 3 | E | 180:143 | 398 | −2 | 5:4 | 12 |

| ●○○ | 3 | F | 4:3 | 498 | −2 | 4:3 | 0 |

| ○●○ | 3 | F♯/G♭ | 45:32 | 590 | −10 | 45:32 | 0 |

| ○○○ | 3 | G | 3:2 | 702 | 2 | 3:2 | 0 |

| ○●● | 4 | G♯/A♭ | 30:19 | 791 | −9 | 8:5 | −23 |

| ●●○ | 4 | A | 240:143 | 896 | −4 | 5:3 | 12 |

| ●○○ | 4 | A♯/B♭ | 16:9 | 996 | −4 | 9:5 | −22 |

| ○●○ | 4 | B | 15:8 | 1088 | −12 | 15:8 | 0 |

| ○○○ | 4 | C | 2:1 | 1200 | 0 | 2:1 | 0 |

| ●●○ | 5 | C♯/D♭ | 300:143 | 1283 | −17 | 32:15 | −29 |

| ●○○ | 5 | D | 20:9 | 1382 | −18 | 9:4 | −22 |

| ○●○ | 5 | D♯/E♭ | 75:32 | 1475 | −25 | 12:5 | −41 |

| ○○○ | 5 | E | 5:2 | 1586 | −14 | 5:2 | 0 |

Tuning compensation

[edit]The additional tubing for each valve usually features a short tuning slide of its own for fine adjustment of the valve's tuning, except when it is too short to make this practicable. For the first and third valves this is often designed to be adjusted as the instrument is played, to account for the deficiencies in the valve system.

In most trumpets and cornets, the compensation must be provided by extending the third valve slide with the third or fourth finger, and the first valve slide with the left hand thumb (see Trigger or throw below). This is used to lower the pitch of the 1–3 and 1–2–3 valve combinations. On the trumpet and cornet, these valve combinations correspond to low D, low C♯, low G, and low F♯, so chromatically, to stay in tune, one must use this method.

In instruments with a fourth valve, such as tubas, euphoniums, piccolo trumpets, etc. that valve lowers the pitch by a perfect fourth; this is used to compensate for the sharpness of the valve combinations 1–3 and 1–2–3 (4 replaces 1–3, 2–4 replaces 1–2–3). All three normal valves may be used in addition to the fourth to increase the instrument's range downwards by a perfect fourth, although with increasingly severe intonation problems.

When four-valved models without any kind of compensation play in the corresponding register, the sharpness becomes so severe that players must finger the note a half-step below the one they are trying to play. This eliminates the note a half-step above their open fundamental.

Manufacturers of low brass instruments may choose one or a combination of four basic approaches to compensate for the tuning difficulties, whose respective merits are subject to debate:

Compensation system

[edit]In the Compensation system, each of the first two (or three) valves has an additional set of tubing extending from the back of the valve. When the third (or fourth) valve is depressed in combination with another one, the air is routed through both the usual set of tubing plus the extra one, so that the pitch is lowered by an appropriate amount. This allows compensating instruments to play with accurate intonation in the octave below their open second partial, which is critical for tubas and euphoniums in much of their repertoire.

The compensating system was applied to horns to serve a different purpose. It was used to allow a double horn in F and B♭ to ease playing difficulties in the high register. In contrast to the system in use in tubas and euphoniums, the default 'side' of the horn is the longer F horn, with secondary lengths of tubing coming into play when the first, second or third valves are pressed; pressing the thumb valve takes these secondary valve slides and the extra length of main tubing out of play to produce a shorter B♭ horn. A later "full double" design has completely separate valve section tubing for the two sides, and is considered superior, although rather heavier in weight.

Additional valves

[edit]Initially, compensated instruments tended to sound stuffy and blow less freely due to the air being doubled back through the main valves. In early designs, this led to sharp bends in the tubing and other obstructions of the air-flow. Some manufacturers therefore preferred adding more 'straight' valves instead, which for example could be pitched a little lower than the 2nd and 1st valves and were intended to be used instead of these in the respective valve combinations. While no longer featured in euphoniums for decades, many professional tubas are still built like this, with five valves being common on CC- and BB♭-tubas and five or six valves on F-tubas.[citation needed]

Compensating double horns can also suffer from the stuffiness resulting from the air being passed through the valve section twice, but as this really only affects the longer F side, a compensating double can be very useful for a 1st or 3rd horn player, who uses the F side less.

Additional sets of slides on each valve

[edit]Another approach was the addition of two sets of slides for different parts of the range. Some euphoniums and tubas were built like this, but today, this approach has become highly exotic for all instruments except horns, where it is the norm, usually in a double, sometimes even triple configuration.

Trigger or throw

[edit]

Some valved brass instruments provide triggers or throws that manually lengthen (or, less commonly, shorten) the main tuning slide, a valve slide, or the main tubing. These mechanisms alter the pitch of notes that are naturally sharp in a specific register of the instrument, or shift the instrument to another playing range. Triggers and throws permit speedy adjustment while playing.

Trigger is used in two senses:

- A trigger can be a mechanical lever that lengthens a slide when pressed in a contrary direction. Triggers are sprung in such a way that they return the slide to its original position when released.

- The term "trigger" also describes a device engaging a valve to lengthen the main tubing, e.g. lowering the key of certain trombones from B♭ to F.

A throw is a simple metal grip for the player's finger or thumb, attached to a valve slide. The general term "throw" can describe a u-hook, a saddle (u-shaped grips), or a ring (ring-shape grip) in which a player's finger or thumb rests. A player extends a finger or thumb to lengthen a slide, and retracts the finger to return the slide to its original position.

Examples of instruments that use triggers or throws

[edit]Trumpet or cornet

[edit]Triggers or throws are sometimes found on the first valve slide. They are operated by the player's thumb and are used to adjust a large range of notes using the first valve, most notably the player's written top line F, the A above directly above that, and the B♭ above that. Other notes that require the first valve slide, but are not as problematic without it include the first line E, the F above that, the A above that, and the third line B♭.

Triggers or throws are often found on the third valve slide. They are operated by the player's fourth finger, and are used to adjust the lower D and C♯. Trumpets typically use throws, whilst cornets may have a throw or trigger.

Trombone

[edit]Trombone triggers are primarily but not exclusively[7] installed on the F-trigger, bass, and contrabass trombones[11] to alter the length of tubing, thus making certain ranges and pitches more accessible.

Euphoniums

[edit]A euphonium occasionally has a trigger on valves other than 2 (especially 3), although many professional quality euphoniums, and indeed other brass band instruments, have a trigger for the main tuning slide.[12]

Mechanism

[edit]The two major types of valve mechanisms are rotary valves and piston valves. The first piston valve instruments were developed just after the start of the 19th century. The Stölzel valve (invented by Heinrich Stölzel in 1814) was an early variety. In the mid 19th century the Vienna valve was an improved design. However many professional musicians preferred rotary valves for quicker, more reliable action, until better designs of piston valves were mass manufactured towards the end of the 19th century. Since the early decades of the 20th century, piston valves have been the most common on brass instruments except for the orchestral horn and the tuba.[13] See also the article Brass Instrument Valves.

Sound production in brass instruments

[edit]Because the player of a brass instrument has direct control of the prime vibrator (the lips), brass instruments exploit the player's ability to select the harmonic at which the instrument's column of air vibrates. By making the instrument about twice as long as the equivalent woodwind instrument and starting with the second harmonic, players can get a good range of notes simply by varying the tension of their lips (see embouchure).

Most brass instruments are fitted with a removable mouthpiece. Different shapes, sizes and styles of mouthpiece may be used to suit different embouchures, or to more easily produce certain tonal characteristics. Trumpets, trombones, and tubas are characteristically fitted with a cupped mouthpiece, while horns are fitted with a conical mouthpiece.

One interesting difference between a woodwind instrument and a brass instrument is that woodwind instruments are non-directional. This means that the sound produced propagates in all directions with approximately equal volume. Brass instruments, on the other hand, are highly directional, with most of the sound produced traveling straight outward from the bell. This difference makes it significantly more difficult to record a brass instrument accurately. It also plays a major role in some performance situations, such as in marching bands.

Manufacture

[edit]Metal

[edit]Traditionally the instruments are normally made of brass, polished and then lacquered to prevent corrosion. Some higher quality and higher cost instruments use gold or silver plating to prevent corrosion.

Alternatives to brass include other alloys containing significant amounts of copper or silver. These alloys are biostatic due to the oligodynamic effect, and thus suppress growth of molds, fungi or bacteria. Brass instruments constructed from stainless steel or aluminium have good sound quality but are rapidly colonized by microorganisms and become unpleasant to play.

Most higher quality instruments are designed to prevent or reduce galvanic corrosion between any steel in the valves and springs, and the brass of the tubing. This may take the form of desiccant design, to keep the valves dry, sacrificial zincs, replaceable valve cores and springs, plastic insulating washers, or nonconductive or noble materials for the valve cores and springs. Some instruments use several such features.[not specific enough to verify]

The process of making the large open end (bell) of a brass instrument is called metal beating. In making the bell of, for example, a trumpet, a person lays out a pattern and shapes sheet metal into a bell-shape using templates, machine tools, handtools, and blueprints. The maker cuts out the bell blank, using hand or power shears. He hammers the blank over a bell-shaped mandrel, and butts the seam, using a notching tool. The seam is brazed, using a torch and smoothed using a hammer or file. A draw bench or arbor press equipped with expandable lead plug is used to shape and smooth the bell and bell neck over a mandrel. A lathe is used to spin the bell head and to form a bead at the edge of bell head. Previously shaped bell necks are annealed, using a hand torch to soften the metal for further bending. Scratches are removed from the bell using abrasive-coated cloth.

Other materials

[edit]

A few specialty instruments are made from wood.

Instruments made mostly from plastic emerged in the 2010s as a cheaper and more robust alternative to brass.[14][15] Plastic instruments could come in almost any colour. The sound plastic instruments produce is different from the one of brass, lacquer, gold or silver.[16] This is because plastic is much less dense, or rather has less matter in a given space as compared to the aforementioned which causes vibrations to occur differently. While originally seen as a gimmick, these plastic models have found increasing popularity during the last decade and are now viewed as practice tools that make for more convenient travel as well as a cheaper option for beginning players.

Ensembles

[edit]Brass instruments are one of the major classical instrument families and are played across a range of musical ensembles.

Orchestras include a varying number of brass instruments depending on music style and era, typically:

- two or three trumpets

- four to eight French horns

- two or three tenor trombones

- one or two bass trombones; the second of which may be a contrabass trombone or cimbasso

- one tuba

- Baroque and classical period orchestras may include valveless trumpets or bugles, or have valved trumpets/cornets playing these parts, and they may include valveless horns, or have valved horns playing these parts.

- Romantic, modern, and contemporary orchestras may include larger numbers of brass including more exotic instruments.

Concert bands generally have a larger brass section than an orchestra, typically:

- four to six trumpets or cornets

- four French horns

- two to four tenor trombones

- one or two bass trombones

- two or three euphoniums or baritone horns

- two or three tubas

British brass bands are made up entirely of brass, mostly conical bore instruments. Typical membership is:

- one soprano cornet

- nine cornets

- one flugelhorn

- three tenor (alto) horns

- two baritone horns

- two tenor trombones

- one bass trombone

- two euphoniums

- two E♭ tubas

- two B♭ tubas

Quintets are common small brass ensembles; a quintet typically contains:

- two trumpets

- one horn

- one trombone

- one tuba or bass trombone

Big bands and other jazz bands commonly contain cylindrical bore brass instruments.

- A big band typically includes:

- four trumpets

- four tenor trombones

- one bass trombone (in place of one of the tenor trombones)

- Smaller jazz ensembles may include a single trumpet or trombone soloist.

Mexican bandas have:

- three trumpets

- three trombones

- two alto horns, also called "charchetas" and "saxores"

- one sousaphone, called "tuba"

Single brass instruments are also often used to accompany other instruments or ensembles such as an organ or a choir.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Baines 1993, pp. 39–40.

- ^ "Producing a harmonic sequence of notes with a trumpet". hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu.

- ^ "The Pedal Tone". hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu.

- ^ "Brass instrument (lip reed) acoustics: an introduction; Resonances and pedal notes". newt.phys.unsw.edu.au.

- ^ Schlesinger, Kathleen (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 182.

- ^ Forsyth 1914, p. 86.

- ^ a b Yamaha Catalog YSL-350C Archived 2009-04-28 at Archive-It with ascending B♭/C rotor

- ^ Understanding Brass Instrument Intonation, University of Oklahoma Horn Studio

- ^ "Brass instrument (lip reed) acoustics: an introduction". www.phys.unsw.edu.au. Archived from the original on 2014-08-14. Retrieved 2017-12-10.

- ^ Monk 1966, pp. 262–3.

- ^ "Yamaha Catalog "Professional Trombones"". yamaha.com. Archived from the original on 2009-09-01. Retrieved 2009-10-25.

- ^ The Besson Prestige euphonium.

- ^ The Early Valved Horn by John Q. Ericson, Associate Professor of horn at Arizona State University

- ^ Flynn, Mike (20 June 2013). "pBone plastic trombone". Jazzwise Magazine. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ^ "Korg UK takes on distribution of Tromba". Musical Instrument Professional. 2 May 2013. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2013.

- ^ "Plastic Sounds". dynamath.scholastic.com. Retrieved 2024-10-09.

Bibliography

[edit]- Baines, Anthony (1993). Brass Instruments: Their History and Development. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-27574-4. LCCN 93019988. OCLC 1285467070. OL 1411201M. Wikidata Q135363982.

- Forsyth, Cecil (1914), Orchestration, London: Macmillan Publishers, LCCN a14002863, OCLC 408500, OL 177040M, Wikidata Q121879329

- Monk, Christopher (1966), "The Older Brass Instruments: Cornet, Trombone, Trumpet", in Anthony Baines (ed.), Musical Instruments Through the Ages, New York: Walker & Company, LCCN 66022505, OCLC 3000440, Wikidata Q135361755

External links

[edit]- Brass Instruments Information on individual Brass Instruments

- The traditional manufacture of brass instruments, a 1991 video (RealPlayer format) featuring maker Robert Barclay; from the web site of the Canadian Museum of Civilization.

- The Orchestra: A User's Manual – Brass

- Brassmusic.Ru – Russian Brass Community Archived 2020-10-29 at the Wayback Machine

- Acoustics of Brass Instruments from Music Acoustics at the University of New South Wales

- Early Valve designs, John Ericson

- 3-Valve and 4-Valve Compensating Systems, David Werden

Brass instrument

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Characteristics

Definition

Brass instruments are aerophones classified as labrosones, in which sound is produced by the sympathetic vibration of an air column within a tubular resonator, initiated by the player's lips vibrating against a cup-shaped or funnel-shaped mouthpiece.[7] The instrument's body is typically constructed from brass or similar metallic alloys, which provide the necessary resonance and durability, though the classification emphasizes the lip-vibration mechanism over the material.[8] The designation "brass" stems from the historical and predominant use of brass—a copper-zinc alloy—as the construction material in Western orchestral and band instruments, valued for its malleability, corrosion resistance, and acoustic reflectivity that enhances projection and timbre.[9] This etymology highlights the material's role in the evolution of these instruments, even as modern variants may incorporate silver plating, gold lacquer, or other metals without altering their categorical status.[8] Central to their design are core components that facilitate sound production and control: the mouthpiece, where lip buzzing occurs to generate the initial vibration; the leadpipe, a curved initial section of tubing that receives and directs the airflow; valves (piston or rotary) or slides, which lengthen the air column to lower pitch; the bell, a flared terminus that amplifies and radiates the sound waves; and the interconnecting tubing, which forms the primary resonant pathway.[10][11] Prominent examples of brass instruments include the trumpet, known for its bright, piercing tone; the horn (or French horn), with its mellow, wide-ranging timbre; the trombone, featuring a slide for continuous pitch adjustment; and the tuba, the lowest-pitched member providing foundational bass support in ensembles.[7]Key Characteristics

Brass instruments are distinguished by their bright, projecting timbre, which arises from their metallic construction and the emphasis on higher harmonics in the overtone series. This results in a powerful, resonant sound that is capable of cutting through dense musical ensembles, providing clarity and presence in orchestral and band settings. The metallic materials, typically alloys like brass or bronze, vibrate efficiently to produce a spectrum rich in upper partials, contributing to the instrument family's characteristic brilliance and intensity.[12] A defining functional trait is the capability for overblowing, where players increase air pressure and lip tension to excite higher harmonics of the air column without relying on valves or slides for pitch alteration. This allows access to the full harmonic series, enabling a wide range of notes from a single tube length and facilitating agile performance across registers. Sound production begins with the vibration of the player's lips against the mouthpiece, briefly setting the air column into resonance.[13] The bell flare plays a crucial role in shaping this output, as its gradual expansion directs sound waves outward for enhanced projection while modifying tone color by reflecting lower frequencies back into the bore and amplifying mid-to-high overtones for a focused, directional quality.[8] Compared to woodwinds, brass instruments generally achieve greater volume and sustain due to their unified air exit through the bell, which improves impedance matching and allows sustained vibration without the energy loss from multiple tone holes.[14]History

Origins and Early Development

The origins of brass instruments trace back to ancient natural horns crafted from animal materials, serving primarily as signaling devices in rituals, warfare, and daily communication. One of the earliest known examples is the shofar, a ritual horn made from a ram's horn, used by ancient Near Eastern cultures including the Israelites for religious ceremonies and announcements, with traditions dating to around 2000 BCE.[15] This lip-vibrated instrument produced a piercing, limited harmonic series, emphasizing its role in evoking awe and rallying communities rather than melodic complexity. Similarly, in the Roman Empire during the 1st century CE, the tuba—a straight, bronze military horn approximately 1.2 meters long—functioned as a signaling tool for infantry commands in battles and processions, its conical bore allowing for loud, far-carrying tones without valves or slides.[16] These precursors highlight the foundational principle of brass sound production through lip vibration into a resonant tube, a concept that persisted across cultures. In medieval Europe and Asia, natural horns and trumpets evolved as essential signaling instruments, adapting ancient designs to feudal and nomadic needs. European examples included the oliphant, an ivory or horn trumpet used by nobility for hunting and warfare from the 10th to 14th centuries, while straight natural trumpets signaled troop movements in military contexts across the continent.[17] In Asia, similar instruments like the Oxus trumpets—bronze horns from Central Asian cultures around 2000–1800 BCE—continued in use for pastoral and ceremonial signaling, bridging ancient and medieval practices.[18] By the 15th century, European makers introduced crooks—interchangeable tubing segments—to natural horns and trumpets, enabling pitch adjustments for different keys without altering the instrument's core form, a development that enhanced versatility in ensemble and solo settings.[19] Non-Western traditions contributed distinct forms that paralleled European developments, often tied to environmental and cultural signaling roles. The didgeridoo, a long wooden aerophone with a conical bore hollowed by termites, originated among Indigenous Australian communities, with rock art evidence indicating use for rhythmic accompaniment in ceremonies dating back at least 1,500 years.[20] In the Alpine regions of Europe, the alphorn—a straight, wooden horn up to 4 meters long—emerged in the 16th century for communicating between mountain pastures, its deep, resonant calls guiding livestock and herdsmen across valleys.[21] These instruments underscore the global diversity of lip-reed designs, prioritizing acoustic projection over chromatic capability. A pivotal influence on early European brass came via trade routes connecting the Ottoman Empire and Persia to the West, where long straight trumpets (nafir) and curved horns introduced during the medieval period inspired adaptations in bore shape and length.[22] These exchanges, facilitated by Silk Road networks from the 13th to 15th centuries, blended Persian conical forms with Ottoman military signaling tools, enriching European designs and paving the way for Renaissance innovations up to the 16th century.[23]Modern Evolution

The invention of the valve system in 1818 by German horn players Heinrich Stölzel and Friedrich Blühmel marked a pivotal advancement in brass instrument design, enabling chromatic playing by mechanically lengthening the instrument's tubing to access notes outside the natural harmonic series.[24] This innovation transformed brass instruments from primarily diatonic signaling tools into versatile melodic and harmonic voices suitable for complex musical compositions. Subsequent refinements included the rotary valve, patented in 1835 by Joseph Riedl in Vienna, which featured a rotating mechanism for smoother airflow and quicker response compared to early piston designs.[25] In 1838, François Périnet in Paris developed the modern piston valve, characterized by angled ports that improved tuning and facilitated faster valve action, becoming the standard for French and American brass instruments.[26] By the late 19th century, compensating systems, pioneered by David James Blaikley in 1874 at Boosey & Co., addressed intonation challenges in lower registers by automatically adding extra tubing lengths when multiple valves were engaged, enhancing the accuracy of euphoniums and tubas.[27] Hector Berlioz's Grand Traité d'Instrumentation et d'Orchestration Modernes (1844) further propelled the evolution of brass usage in orchestral settings, advocating for expanded sections—including up to four horns, two cornets, four trumpets, three trombones, and an ophicleide—to achieve greater dynamic range and timbral variety in Romantic-era works.[28] This treatise influenced composers and conductors to integrate valved brass more prominently, standardizing larger ensembles that balanced brass with strings and woodwinds for fuller symphonic textures. In the 20th century, jazz emerged as a transformative force, prompting innovations like the widespread adoption of mutes—such as straight, cup, and plunger types—to produce varied timbres for expressive solos and ensemble blending, as seen in the works of Duke Ellington's orchestra.[29] Jazz also drove customizations in leadpipe designs, with narrower bores and tapered configurations on trumpets to facilitate brighter, more agile articulation suited to improvisational styles.[30] During and after World War II, material shortages prompted the development of plastic instruments, such as bugles made from Tenite plastic, and the incorporation of synthetic components like plastic mouthpieces and valve parts for durability and affordability in student instruments.[31][32] Since 2000, sustainability concerns have spurred the use of ecological materials in brass construction, such as recycled alloys and lead-free brasses to minimize environmental impact, alongside fully plastic models like the pBone trombone made from recyclable ABS for lightweight, corrosion-resistant alternatives.[33] These developments align with broader industry shifts toward energy-efficient manufacturing and biodegradable accessories. In contemporary music, digital amplification via pickups and microphones has enabled brass instruments to integrate seamlessly with electronic elements, expanding their role in hybrid ensembles and experimental compositions that blend acoustic resonance with processed sounds.[34]Classification

Bore Characteristics

Brass instruments are classified by the shape and diameter of their bore, which is the internal tubing through which air passes, significantly influencing the instrument's tone, playability, and projection. The two primary bore shapes are cylindrical and conical, each producing distinct acoustic properties due to how they affect airflow and wave propagation. Cylindrical bores feature tubing of relatively constant diameter, as seen in instruments like the trumpet and trombone, resulting in a brighter, more focused tone that facilitates easier production of high notes by emphasizing higher harmonics in the sound spectrum.[8][35] In contrast, conical bores gradually widen from the mouthpiece to the bell, characteristic of instruments such as the horn and tuba, yielding a warmer, mellower timbre with enhanced resonance in the lower register due to a more balanced distribution of even and odd harmonics.[8][36] This shape reduces airflow resistance compared to cylindrical bores, allowing for smoother low-note articulation and a richer overtone structure that contributes to the instrument's blending quality in ensembles.[35] Bore diameter variations further refine these effects, with narrower bores, such as those in the cornet (typically around 0.46 inches or 11.7 mm), increasing resistance to the player's breath and producing a compact, projecting sound ideal for soloistic clarity.[35] Wider bores, like in the bass trombone (often 0.562 inches or 14.3 mm), decrease resistance and promote a fuller, more voluminous tone with greater low-end projection, though they demand more air support from the performer.[35] These differences in diameter modulate the instrument's responsiveness and timbral focus without altering the fundamental pitch range. A related classification distinguishes whole-tube instruments, such as the tuba, from half-tube instruments like the trombone, based on the effective tubing length relative to the wavelength of the fundamental frequency. Whole-tube designs support even harmonics more prominently, contributing to their robust low-end response, while half-tube configurations emphasize odd harmonics, enhancing the clarity of upper partials in the harmonic series.[37] Acoustically, cylindrical bores in general amplify higher harmonics, leading to the characteristic "brassy" timbre, whereas the expanding nature of conical bores tempers these overtones for a smoother overall sound profile.[36]Pitch and Range Families

Brass instruments are classified into families primarily based on their standard pitch ranges, which align with traditional vocal designations such as soprano, alto, tenor, and bass, extending to contrabass and double contrabass for deeper tones. This grouping facilitates orchestral scoring, ensemble blending, and performer selection by emphasizing the instrument's fundamental playing range and octave position relative to concert pitch. The classification accounts for the instrument's design, including tubing length and mouthpiece size, which influence the lowest and highest playable notes, though bore shape primarily affects timbre rather than range boundaries.[38][39] The soprano family encompasses the highest-pitched brass instruments, designed for brilliant, piercing tones in upper registers. A representative example is the piccolo trumpet, typically pitched in B♭, which extends the standard trumpet's range upward by approximately an octave, sounding from about E4 to F6 in concert pitch. This instrument is valued in Baroque repertoire and modern ensembles for its agile, high-lying passages.[39] In the alto family, instruments occupy a mid-high range, providing melodic support with a warmer, more rounded timbre. The French horn, pitched in F and functioning as a transposing instrument, exemplifies this category; written C sounds as F a perfect fifth lower, with a practical range from F2 to F5 in concert pitch. Its notation in treble or bass clef reflects this transposition to ease reading for performers accustomed to certain fingerings.[39] The tenor family features instruments suited for middle-range melodies and harmonies, balancing agility with fuller tone. Key examples include the tenor trombone, pitched in B♭ (non-transposing in notation, sounding as written in bass clef), with a range from B♭1 to B♭4, and the trumpet in B♭ or C, ranging from F♯3 to C6 in concert pitch for the B♭ variant. The B♭ trumpet transposes written notes down a major second, while the C trumpet is non-transposing, allowing direct concert pitch reading.[39] Bass family instruments deliver foundational support with their low, resonant tones, essential for harmonic depth in ensembles. Prominent members are the bass trombone (extending the tenor range downward to E♭1 or lower with attachments), the euphonium in B♭ (transposing down a major second in bass clef notation, concert range from B♭1 to B♭4), and the tuba in CC or BB♭ (non-transposing or transposing down a major ninth/octave, reaching from C1 to F3 or lower). These instruments use bass clef notation, with tubas often requiring compensatory systems for accurate intonation across their wide spans.[38][39] Extending below the bass family, contrabass and double contrabass variants provide extreme low-end reinforcement, often in specialized or Wagnerian contexts. The Wagner tuba, available in tenor (B♭, range approximately B♭2 to F5) and bass (F, range approximately C2 to A4) forms, transposes like the euphonium and horn respectively, bridging horn and tuba timbres in operatic scores. The subcontrabass tuba, pitched in CCC or lower (an octave below the contrabass tuba), achieves ranges down to 16 Hz (C0), used rarely in experimental or large-scale works for its profound subsonic effects.[40][39]| Family | Example Instruments | Typical Key | Concert Pitch Range (Approximate) | Transposing? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soprano | Piccolo trumpet | B♭ | E4–F6 | Yes (down major second) |

| Alto | French horn | F | F2–F5 | Yes (down perfect fifth) |

| Tenor | Tenor trombone, Trumpet | B♭ (trombone non-transposing; trumpet B♭ or C) | B♭1–B♭4 (trombone); F♯3–C6 (B♭ trumpet) | Trombone: No; Trumpet: Yes/No |

| Bass | Bass trombone, Euphonium, Tuba | B♭ (euphonium); CC/BB♭ (tuba) | E♭1–B♭3 (bass trombone); B♭1–B♭4 (euphonium); C1–F3 (tuba) | Varies (euphonium yes, down major second in bass clef; tuba often no) |

| Contrabass/Double Contrabass | Wagner tuba (tenor/bass), Subcontrabass tuba | B♭/F (Wagner); CCC (subcontrabass) | B♭2–F5 (Wagner tenor); C2–A4 (Wagner bass); C0–C2 (subcontrabass) | Yes (like euphonium/horn) |