Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

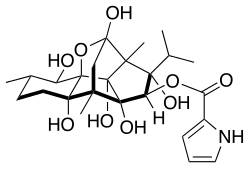

Ryanodine receptor

View on Wikipedia

Ryanodine receptors (RyR) make up a class of high-conductance, intracellular calcium channels present in various forms, such as animal muscles and neurons.[1] There are three major isoforms of the ryanodine receptor, which are found in different tissues and participate in various signaling pathways involving calcium release from intracellular organelles.[2]

Structure

[edit]Ryanodine receptors are multidomain homotetramers which regulate intracellular calcium ion release from the sarcoplasmic and endoplasmic reticula.[3] They are the largest known ion channels, with weights exceeding 2 megadaltons, and their structural complexity enables a wide variety of allosteric regulation mechanisms.[4][5]

RyR1 cryo-EM structure revealed a large cytosolic assembly built on an extended α-solenoid scaffold connecting key regulatory domains to the pore. The RyR1 pore architecture shares the general structure of the six-transmembrane ion channel superfamily. A unique domain inserted between the second and third transmembrane helices interacts intimately with paired EF-hands originating from the α-solenoid scaffold, suggesting a mechanism for channel gating by Ca2+.[1][6]

Etymology

[edit]The ryanodine receptors are named after the plant alkaloid ryanodine which shows a high affinity to them.

Isoforms

[edit]There are multiple isoforms of ryanodine receptors:

- RyR1 is primarily expressed in skeletal muscle

- It is essential for excitation-contraction coupling

- RyR2 is primarily expressed in myocardium (heart muscle)

- the major cellular mediator of calcium-induced calcium release (CICR) in animal cells.

- RyR3 is expressed more widely, but especially in the brain.[7]

- It is involved in neuroprotection, memory, pain modulation, and social behavior.[8]

Non-mammalian vertebrates typically express two RyR isoforms, referred to as RyR-alpha and RyR-beta. Many invertebrates, including the model organisms Drosophila melanogaster (fruitfly) and Caenorhabditis elegans, only have a single isoform. In non-metazoan species, calcium-release channels with sequence homology to RyRs can be found, but they are shorter than the mammalian ones and may be closer to inositol trisphosphate (IP3) receptors.

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Physiology

[edit]Ryanodine receptors mediate the release of calcium ions from the sarcoplasmic reticulum and endoplasmic reticulum, an essential step in muscle contraction.[1] In skeletal muscle, activation of ryanodine receptors occurs via a physical coupling to the dihydropyridine receptor (a voltage-dependent, L-type calcium channel), whereas in cardiac muscle, the primary mechanism of activation is calcium-induced calcium release, which causes calcium outflow from the sarcoplasmic reticulum.[9]

It has been shown that calcium release from a number of ryanodine receptors in a RyR cluster results in a spatiotemporally-restricted rise in cytosolic calcium that can be visualized as a calcium spark.[10] Calcium release from RyR has been shown to regulate ATP production in heart and pancreas cells.[11][12][13]

Ryanodine receptors are similar to the inositol trisphosphate (IP3 or InsP3) receptor, and stimulated to transport Ca2+ into the cytosol by recognizing Ca2+ on its cytosolic side, thus establishing a positive feedback mechanism; a small amount of Ca2+ in the cytosol near the receptor will cause it to release even more Ca2+ (calcium-induced calcium release/CICR).[1] However, as the concentration of intracellular Ca2+ rises, this can trigger closing of RyR, preventing the total depletion of SR. This finding indicates that a plot of opening probability for RyR as a function of Ca2+ concentration is a bell-curve.[14] Furthermore, RyR can sense the Ca2+ concentration inside the ER/SR and spontaneously open in a process known as store overload-induced calcium release (SOICR).[15]

RyRs are especially important in neurons and muscle cells. In heart and pancreas cells, another second messenger (cyclic ADP-ribose) takes part in the receptor activation.

The localized and time-limited activity of Ca2+ in the cytosol is also called a Ca2+ wave. The propagation of the wave is accomplished by the feedback mechanism of the ryanodine receptor. The activation of phospholipase C by GPCR or RTK triggers the production of inositol trisphosphate, which activates of the InsP3 receptor.

Pharmacology

[edit]- Antagonists:[16]

- Ryanodine locks the RyRs at half-open state at nanomolar concentrations, yet fully closes them at micromolar concentration.

- Dantrolene the clinically used antagonist

- Ruthenium red

- procaine, tetracaine, etc. (local anesthetics)

- Activators:[17]

- Agonist: 4-chloro-m-cresol and suramin are direct agonists, i.e., direct activators.

- Xanthines like caffeine and pentifylline activate it by potentiating sensitivity to native ligand Ca.

- Physiological agonist: Cyclic ADP-ribose can act as a physiological gating agent. It has been suggested that it may act by making FKBP12.6 (12.6 kilodalton FK506 binding protein, as opposed to 12 kDa FKBP12 which binds to RyR1) which normally bind (and blocks) RyR2 channel tetramer in an average stoichiometry of 3.6, to fall off RyR2 (which is the predominant RyR in pancreatic beta cells, cardiomyocytes and smooth muscles).[18]

A variety of other molecules may interact with and regulate ryanodine receptor. For example: dimerized Homer physical tether linking inositol trisphosphate receptors (IP3R) and ryanodine receptors on the intracellular calcium stores with cell surface group 1 metabotropic glutamate receptors and the Alpha-1D adrenergic receptor[19]

Ryanodine

[edit]The plant alkaloid ryanodine, for which this receptor was named, has become an invaluable investigative tool. It can block the phasic release of calcium, but at low doses may not block the tonic cumulative calcium release. The binding of ryanodine to RyRs is use-dependent, that is the channels have to be in the activated state. At low (<10 micromolar, works even at nanomolar) concentrations, ryanodine binding locks the RyRs into a long-lived subconductance (half-open) state and eventually depletes the store, while higher (~100 micromolar) concentrations irreversibly inhibit channel-opening.

Diamide insecticide

[edit]The diamides, an important class of insecticide making up 13% of the insecticide market,[20] work by activating insect RyRs.[21]

Associated proteins

[edit]RyRs form docking platforms for a multitude of proteins and small molecule ligands.[1] Accessory proteins bind these channels and regulate their gating, localization, expression, and integration with cellular signaling in a tissue- and isoform-specific manner.

FK506-Binding Proteins (FKBP12 / FKBP12.6) — aka Calstabin-1 and Calstabin-2 — stabilize the closed state of RyRs, preventing pathological Ca²⁺ leak.[8]

The cardiac-specific isoform (RyR2) is known to form a quaternary complex with luminal calsequestrin, junctin, and triadin.[22] Calsequestrin (CASQ) has multiple Ca2+ binding sites that bind with very low affinity, allowing easy ion release. It acts as RyR gate modulators by signaling when Ca2+ stores are full. Triadin and Junctin are sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) membrane proteins that link RyRs to CASQ and also respond to Ca²⁺ store levels.[23]

Calmodulin (CaM) and S100A1 both bind the same site on RyRs (especially RyR1 and RyR2), but exert opposite effects: Ca²⁺-bound CaM inhibits RyRs while S100A1 enhances its opening. Expression levels and competition between these proteins tune RyR responses to Ca²⁺ signals.[8]

Role in disease

[edit]RyR1 mutations are associated with malignant hyperthermia and central core disease.[24] Mutant-type RyR1 receptors exposed to volatile anesthetics or other triggering agents can display an increased affinity for cytoplasmic Ca2+ at activating sites as well as a decreased cytoplasmic Ca2+ affinity at inhibitory sites.[25] The breakdown of this feedback mechanism causes uncontrolled release of Ca2+ into the cytoplasm, and increased ATP hydrolysis resulting from ATPase enzymes shuttling Ca2+ back into the sarcoplasmic reticulum leads to excessive heat generation.[26]

RyR2 mutations play a role in stress-induced polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (a form of cardiac arrhythmia) and ARVD.[7] It has also been shown that levels of type RyR3 are greatly increased in PC12 cells overexpressing mutant human Presenilin 1, and in brain tissue in knockin mice that express mutant Presenilin 1 at normal levels,[27] and thus may play a role in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases, like Alzheimer's disease.[28]

The presence of antibodies against ryanodine receptors in blood serum has also been associated with myasthenia gravis (i.e., MG).[1] Individuals with MG who have antibodies directed against ryanodine receptors typically have a more severe form of generalized MG in which their skeletal muscle weaknesses involve muscles that govern basic life functions.[29]

Sudden cardiac death in several young individuals in the Amish community (four of which were from the same family) was traced to homozygous duplication of a mutant RyR2 (Ryanodine Receptor) gene.[30] Normal (wild type) ryanodine receptors are involved in CICR in heart and other muscles, and RyR2 functions primarily in the myocardium (heart muscle).

As potential drug targets

[edit]The expression, distribution, and gating of RyRs are modified by cellular proteins, presenting an opportunity to develop new drugs that target RyR channel complexes by manipulating these proteins. Several drugs, such as FK506, rapamycin, and K201, can modify interactions between RyRs and their accessory proteins.[8]

| Drug | Target | Effect | Clinical Use | Concerns |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FK506, Rapamycin | FKBP-RyR | Disrupts complex, causes leak | Immunosuppressant | Not RyR-specific |

| K201 (JTV519) | FKBP-RyR | Stabilizes complex, prevents leak | Heart Failure (still investigational) | Off-target SERCA inhibition |

| Dantrolene | RyR1, RyR3 | receptor antagonist | MH, spasticity | No effect on RyR2 |

| Doxorubicin, Tricyclic antidepressants | CASQ2 | Reduces Ca²⁺ buffering | Chemotherapy, antidepressants | Cardiotoxicity |

| Ivabradine | Unknown | Increases FKBP12/12.6 levels | Heart Failure (bradycardia) | Indirect mechanistic action |

| Statins | RyR3 upregulation | Myopathy | Hypercholesterolemia | Adverse skeletal muscle effects |

See also

[edit]- Diamide, a class of insecticide that act through ryanodine receptors

- Neuromuscular junction

- Dihydropyridine receptor

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Santulli G, Marks AR (2015). "Essential Roles of Intracellular Calcium Release Channels in Muscle, Brain, Metabolism, and Aging". Current Molecular Pharmacology. 8 (2): 206–222. doi:10.2174/1874467208666150507105105. PMID 25966694.

- ^ Bennett DL, Cheek TR, Berridge MJ, De Smedt H, Parys JB, Missiaen L, Bootman MD (1996-03-15). "Expression and function of ryanodine receptors in nonexcitable cells". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 271 (11): 6356–6362. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.11.6356. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 8626432.

- ^ Santulli G, Lewis D, des Georges A, Marks AR, Frank J (2018). "Ryanodine Receptor Structure and Function in Health and Disease". In Harris JR, Boekema EJ (eds.). Membrane Protein Complexes: Structure and Function. Vol. 87. Singapore: Springer Singapore. pp. 329–352. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-7757-9_11. ISBN 978-981-10-7756-2. PMC 5936639. PMID 29464565.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Lanner JT, Georgiou DK, Joshi AD, Hamilton SL (November 2010). "Ryanodine receptors: structure, expression, molecular details, and function in calcium release". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2 (11) a003996. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a003996. PMC 2964179. PMID 20961976.

- ^ Van Petegem F (January 2015). "Ryanodine receptors: allosteric ion channel giants". Journal of Molecular Biology. 427 (1): 31–53. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2014.08.004. PMID 25134758.

- ^ Zalk R, Clarke OB, des Georges A, Grassucci RA, Reiken S, Mancia F, et al. (January 2015). "Structure of a mammalian ryanodine receptor". Nature. 517 (7532): 44–49. Bibcode:2015Natur.517...44Z. doi:10.1038/nature13950. PMC 4300236. PMID 25470061.

- ^ a b Zucchi R, Ronca-Testoni S (March 1997). "The sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ channel/ryanodine receptor: modulation by endogenous effectors, drugs and disease states". Pharmacological Reviews. 49 (1): 1–51. doi:10.1016/S0031-6997(24)01312-7. PMID 9085308.

- ^ a b c d Mackrill JJ (2010-06-01). "Ryanodine receptor calcium channels and their partners as drug targets". Biochemical Pharmacology. 79 (11): 1535–1543. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2010.01.014. ISSN 0006-2952. PMID 20097179.

- ^ Fabiato A (July 1983). "Calcium-induced release of calcium from the cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum". The American Journal of Physiology. 245 (1): C1-14. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.1983.245.1.C1. PMID 6346892.

- ^ Cheng H, Lederer WJ, Cannell MB (October 1993). "Calcium sparks: elementary events underlying excitation-contraction coupling in heart muscle". Science. 262 (5134): 740–744. Bibcode:1993Sci...262..740C. doi:10.1126/science.8235594. PMID 8235594.

- ^ Bround MJ, Wambolt R, Luciani DS, Kulpa JE, Rodrigues B, Brownsey RW, et al. (June 2013). "Cardiomyocyte ATP production, metabolic flexibility, and survival require calcium flux through cardiac ryanodine receptors in vivo". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 288 (26): 18975–18986. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.427062. PMC 3696672. PMID 23678000.

- ^ Tsuboi T, da Silva Xavier G, Holz GG, Jouaville LS, Thomas AP, Rutter GA (January 2003). "Glucagon-like peptide-1 mobilizes intracellular Ca2+ and stimulates mitochondrial ATP synthesis in pancreatic MIN6 beta-cells". The Biochemical Journal. 369 (Pt 2): 287–299. doi:10.1042/BJ20021288. PMC 1223096. PMID 12410638.

- ^ Dror V, Kalynyak TB, Bychkivska Y, Frey MH, Tee M, Jeffrey KD, et al. (April 2008). "Glucose and endoplasmic reticulum calcium channels regulate HIF-1beta via presenilin in pancreatic beta-cells". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 283 (15): 9909–9916. doi:10.1074/jbc.M710601200. PMID 18174159.

- ^ Meissner G, Darling E, Eveleth J (January 1986). "Kinetics of rapid Ca2+ release by sarcoplasmic reticulum. Effects of Ca2+, Mg2+, and adenine nucleotides". Biochemistry. 25 (1): 236–244. doi:10.1021/bi00349a033. PMID 3754147.

- ^ Van Petegem F (September 2012). "Ryanodine receptors: structure and function". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 287 (38): 31624–31632. doi:10.1074/jbc.r112.349068. PMC 3442496. PMID 22822064.

- ^ Vites AM, Pappano AJ (March 1994). "Distinct modes of inhibition by ruthenium red and ryanodine of calcium-induced calcium release in avian atrium". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 268 (3): 1476–1484. doi:10.1016/S0022-3565(25)38589-7. PMID 7511166.

- ^ Xu L, Tripathy A, Pasek DA, Meissner G (September 1998). "Potential for pharmacology of ryanodine receptor/calcium release channels". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 853 (1): 130–148. Bibcode:1998NYASA.853..130T. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08262.x. PMID 10603942. S2CID 86436194.

- ^ Wang YX, Zheng YM, Mei QB, Wang QS, Collier ML, Fleischer S, et al. (March 2004). "FKBP12.6 and cADPR regulation of Ca2+ release in smooth muscle cells". American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology. 286 (3): C538 – C546. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00106.2003. PMID 14592808. S2CID 20900277.

- ^ Tu JC, Xiao B, Yuan JP, Lanahan AA, Leoffert K, Li M, et al. (October 1998). "Homer binds a novel proline-rich motif and links group 1 metabotropic glutamate receptors with IP3 receptors". Neuron. 21 (4): 717–726. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80589-9. PMID 9808459. S2CID 2851554.

- ^ Sparks TC (2024). "Insecticide mixtures—uses, benefits and considerations". Pest Management Science. 81 (3): 1137–1144. doi:10.1002/ps.7980. PMID 38356314.

- ^ Nauen R, Steinbach D (27 August 2016). "Resistance to Diamide Insecticides in Lepidopteran Pests". In Horowitz AR, Ishaaya I (eds.). Advances in Insect Control and Resistance Management. Cham: Springer (published 26 August 2016). pp. 219–240. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-31800-4_12. ISBN 978-3-319-31800-4.

- ^ Handhle A, Ormonde CE, Thomas NL, Bralesford C, Williams AJ, Lai FA, Zissimopoulos S (November 2016). "Calsequestrin interacts directly with the cardiac ryanodine receptor luminal domain". Journal of Cell Science. 129 (21): 3983–3988. doi:10.1242/jcs.191643. PMC 5117208. PMID 27609834.

- ^ Meissner G (2002-11-01). "Regulation of mammalian ryanodine receptors". Frontiers in Bioscience: A Journal and Virtual Library. 7 (4) A899: d2072–2080. doi:10.2741/A899. ISSN 1093-9946. PMID 12438018.

- ^ Robinson RL, Brooks C, Brown SL, Ellis FR, Halsall PJ, Quinnell RJ, et al. (August 2002). "RYR1 mutations causing central core disease are associated with more severe malignant hyperthermia in vitro contracture test phenotypes". Human Mutation. 20 (2): 88–97. doi:10.1002/humu.10098. PMID 12124989. S2CID 21497303.

- ^ Yang T, Ta TA, Pessah IN, Allen PD (July 2003). "Functional defects in six ryanodine receptor isoform-1 (RyR1) mutations associated with malignant hyperthermia and their impact on skeletal excitation-contraction coupling". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (28): 25722–25730. doi:10.1074/jbc.m302165200. PMID 12732639.

- ^ Reis M, Farage M, de Meis L (2002-01-01). "Thermogenesis and energy expenditure: control of heat production by the Ca(2+)-ATPase of fast and slow muscle". Molecular Membrane Biology. 19 (4): 301–310. doi:10.1080/09687680210166217. PMID 12512777. S2CID 10720335.

- ^ Chan SL, Mayne M, Holden CP, Geiger JD, Mattson MP (June 2000). "Presenilin-1 mutations increase levels of ryanodine receptors and calcium release in PC12 cells and cortical neurons". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (24): 18195–18200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M000040200. PMID 10764737.

- ^ Gong S, Su BB, Tovar H, Mao C, Gonzalez V, Liu Y, et al. (June 2018). "Polymorphisms Within RYR3 Gene Are Associated With Risk and Age at Onset of Hypertension, Diabetes, and Alzheimer's Disease". American Journal of Hypertension. 31 (7): 818–826. doi:10.1093/ajh/hpy046. PMID 29590321.

- ^ Gilhus NE (July 2023). "Myasthenia gravis, respiratory function, and respiratory tract disease". Journal of Neurology. 270 (7): 3329–3340. doi:10.1007/s00415-023-11733-y. PMC 10132430. PMID 37101094.

- ^ Tester DJ, Bombei HM, Fitzgerald KK, Giudicessi JR, Pitel BA, Thorland EC, et al. (March 2020). "Identification of a Novel Homozygous Multi-Exon Duplication in RYR2 Among Children With Exertion-Related Unexplained Sudden Deaths in the Amish Community". JAMA Cardiology. 5 (3): 13–18. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2019.5400. PMC 6990654. PMID 31913406.

External links

[edit]- Ryanodine+Receptor at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)