Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

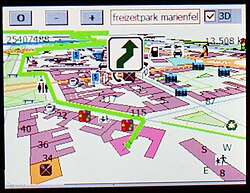

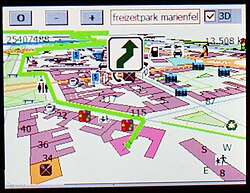

Automotive navigation system

View on Wikipedia

An automotive navigation system is part of the automobile controls or a third party add-on used to find direction in an automobile. It typically uses a satellite navigation device to get its position data which is then correlated to a position on a road. When directions are needed routing can be calculated. On the fly traffic information (road closures, congestion) can be used to adjust the route.

Dead reckoning using distance data from sensors attached to the drivetrain, an accelerometer, a gyroscope, and a magnetometer can be used for greater reliability, as GNSS signal loss and/or multipath can occur due to urban canyons or tunnels.

Mathematically, automotive navigation is based on the shortest path problem, within graph theory, which examines how to identify the path that best meets some criteria (shortest, cheapest, fastest, etc.) between two points in a large network.

Automotive navigation systems are crucial for the development of self-driving cars.[1]

History

[edit]Automotive navigation systems represent a convergence of a number of diverse technologies, many of which have been available for many years, but were too costly or inaccessible. Limitations such as batteries, display, and processing power had to be overcome before the product became commercially viable.[2]

- 1961: Hidetsugu Yagi designed a wireless-based navigation system. This design was still primitive and intended for military-use.

- 1966: General Motors Research (GMR) was working on a non-satellite-based navigation and assistance system called DAIR (Driver Aid, Information & Routing). After initial tests GM found that it was not a scalable or practical way to provide navigation assistance. Decades later, however, the concept would be reborn as OnStar (founded 1996).[3]

- 1971: Compact Cassette based navigation following pre-determined routes, instructions would be read followed by a tone that would tell a controller to continue the cassette after the distance (denoted by the tone) had been reached. [4]

- 1973: Japan's Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) and Fuji Heavy Industries sponsored CATC (Comprehensive Automobile Traffic Control), a Japanese research project on automobile navigation systems.[5]

- 1979: MITI established JSK (Association of Electronic Technology for Automobile Traffic and Driving) in Japan.[5]

- 1980: Electronic Auto Compass with new mechanism on the Toyota Crown.

- 1981: The earlier research of CATC led to the first generation of automobile navigation systems from Japanese companies Honda, Nissan and Toyota. They used dead reckoning technology.[5]

- 1981: Honda's Electro Gyrocator was the first commercially available car navigation system. It used inertial navigation systems, which tracked the distance traveled, the start point, and direction headed.[6] It was also the first with a map display.[5]

- 1981: Navigation computer on the Toyota Celica (NAVICOM).[7]

- 1983: Etak was founded. It made an early system that used map-matching to improve on dead reckoning instrumentation. Digital map information was stored on standard cassette tapes.[8]

- 1987: Toyota introduced the World's first CD-ROM-based navigation system on the Toyota Crown.[9]

- 1989: Gregg Howe of Design Works USA applied Hunter Systems $40,000 navigational computer to the Magna Torrero Concept Car. Originally developed to locate hydrants for fire departments, this system utilized both satellite signals & dead reckoning improving overall system accuracy due to civilian GPS limitations. This system also boast a color raster scan monitor, rather than the monochromatic vector mapping displays used by predecessors.[10][11][12]

- 1990: Mazda Eunos Cosmo became the first production car with built-in GPS-navigation system[13]

- 1991: General Motors partnered with the American Automotive Association, Florida Department of Transportation, as well as the city of Orlando to create TravTek (short for Travel Technology) which was a computerized in-car navigation system. A fleet of 100 Oldsmobile Toronados were rolled out with the system with 75 available for rent through Avis' Orlando International Airport office, the other 25 were test-driven by local drivers. A computer system was installed in the trunk of the vehicle with a special antenna mounted in the back and was hooked up to the video screen in the Oldsmobile Toronado (an option in the standard Toronado) to display the navigation. TravTek covered a 12,000 square mile area in Orlando and its metro areas, as well as contained listings for restaurants, AAA-approved hotels and attractions.[14]

- 1991: Toyota introduced GPS car navigation on the Toyota Soarer.

- 1991: Mitsubishi introduced GPS car navigation on the Mitsubishi Debonair (MMCS: Mitsubishi Multi Communication System).[15]

- 1992: Voice assisted GPS navigation system on the Toyota Celsior.

- 1993: The Austrian channel ORF airs a presentation of the software company bitMAP and its head Werner Liebig's invention, an electronic city map including street names and house numbers, using a satellite-based navigation system. bitMAP attends Comdex in Las Vegas the same year, but doesn't manage to market itself properly.[16][17][18]

- 1994: BMW 7 series E38 first European model featuring GPS navigation. The navigation system was developed in cooperation with Philips (Philips CARIN).[19]

- 1995: Oldsmobile introduced the first GPS navigation system available in a United States production car, called GuideStar.[20] The navigation system was developed in cooperation with Zexel. Zexel partnered with Avis Car Rental to make the system widely available in rental cars. This provided many in the United States general public with their first opportunity to use car navigation.

- 1995: Device called "Mobile Assistant" or short, MASS, produced by Munich-based company ComRoad AG, won the title "Best Product in Mobile Computing" on CeBit by magazine Byte. It offered turn-by-turn navigation via wireless internet connection, with both GPS and speed sensor in the car.

- 1995: Acura introduced the first hard disk drive-based navigation system in the 1996 RL.[21]

- 1997: Navigation system using Differential GPS developed as a factory-installed option on the Toyota Prius[22]

- 1998: First DVD-based navigation system introduced on the Toyota Progres.

- 2000: The United States made a more accurate GPS signal available for civilian use.[23]

- 2003: Toyota introduced the first Hard disk drive-based navigation system and the industry's first DVD-based navigation system with a built-in Electronic throttle control

- 2007: Toyota introduced Map on Demand, a technology for distributing map updates to car navigation systems, developed as the first of its kind in the world

- 2008: World's first navigation system-linked brake assist function and Navigation system linked to Adaptive Variable Suspension System (NAVI/AI-AVS) on Toyota Crown

- 2009: With a release of mobile navigation app from Sygic for iOS new era of a mobile device navigation systems had begun gaining in popularity since

Technology

[edit]

The road database is a vector map. Street names or numbers and house numbers, as well as points of interest (waypoints), are encoded as geographic coordinates. This enables users to find a desired destination by street address or as geographic coordinates. (See map database management.)

Map database formats are almost uniformly proprietary, with no industry standards for satellite navigation maps, although some companies are trying to address this with SDAL (Shared Data Access Library) and Navigation Data Standard (NDS). Map data vendors such as Tele Atlas and Navteq create the base map in a GDF (Geographic Data Files) format, but each electronics manufacturer compiles it in an optimized, usually proprietary manner. GDF is not a CD standard for car navigation systems. GDF is used and converted onto the CD-ROM in the internal format of the navigation system. CDF (CARiN Database Format) is a proprietary navigation map format created by Philips.

SDAL is a proprietary map format developed by Navteq, which was released royalty free in the hope that it would become an industry standard for digital navigation maps, has not been very widely adopted by the industry. Vendors who used this format include:

Navigation Data Standard (NDS)

[edit]The Navigation Data Standard (NDS) initiative, is an industry grouping of car manufacturers, navigation system suppliers and map data suppliers whose objective is the standardization of the data format used in car navigation systems, as well as allow a map update capability. The NDS effort began in 2004 and became a registered association in 2009.[24] Standardization would improve interoperability, specifically by allowing the same navigation maps to be used in navigation systems from 20 manufacturers.[25] Companies involved include BMW, Volkswagen, Daimler, Renault, ADIT, Aisin AW, Alpine Electronics, Navigon, Navis-AMS, Bosch, DENSO, Mitsubishi, Harman International Industries, Panasonic, Preh Car Connect formerly TechniSat, PTV, Continental AG, Clarion, Navteq, Navinfo Archived 2020-08-01 at the Wayback Machine, TomTom and Zenrin.

Media

[edit]The road database may be stored in solid state read-only memory (ROM), optical media (CD or DVD), solid state flash memory, magnetic media (hard disk), or a combination. A common scheme is to have a base map permanently stored in ROM that can be augmented with detailed information for a region the user is interested in. A ROM is always programmed at the factory; the other media may be preprogrammed, downloaded from a CD or DVD via a computer or network connection, or directly using a card reader.

Some navigation device makers provide free map updates for their customers. These updates are often obtained from the vendor's website, which is accessed by connecting the navigation device to a PC.

Real-time data

[edit]Some systems can receive and display information on traffic congestion using either TMC, RDS, or by GPRS/3G data transmission via mobile phones.

In practice, Google has updated Google Maps for Android and iOS to alert users when a faster route becomes available in 2014. This change helps integrate real-time data with information about the more distant parts of a route.[26]

Integration and other functions

[edit]- The color LCD screens on some automotive navigation systems can also be used to display television broadcasts or DVD movies.

- A few systems integrate (or communicate) with mobile phones for hands-free talking and SMS messaging (i.e., using Bluetooth or Wi-Fi).

- Automotive navigation systems can include personal information management for meetings, which can be combined with a traffic and public transport information system.

Original factory equipment

[edit]Many vehicle manufacturers offer a satellite navigation device as an option in their vehicles. Customers whose vehicles did not ship with GNSS can therefore purchase and retrofit the original factory-supplied GNSS unit. In some cases this can be a straightforward "plug-and-play" installation if the required wiring harness is already present in the vehicle. However, with some manufacturers, new wiring is required, making the installation more complex.

The primary benefit of this approach is an integrated and factory-standard installation. Many original systems also contain a gyrocompass and/or an accelerometer and may accept input from the vehicle's speed sensors and reverse gear engagement signal output, thereby allowing them to navigate via dead reckoning when a GPS signal is temporarily unavailable.[27] However, the costs can be considerably higher than other options.

SMS

[edit]Establishing points of interest in real-time and transmitting them via GSM cellular telephone networks using the Short Message Service (SMS) is referred to as Gps2sms. Some vehicles and vessels are equipped with hardware that is able to automatically send an SMS text message when a particular event happens, such as theft, anchor drift or breakdown. The receiving party (e.g., a tow truck) can store the waypoint in a computer system, draw a map indicating the location, or see it in an automotive navigation system.

See also

[edit]- Augmented reality

- Automatic vehicle location

- Autonomous car

- Electronic Route Guidance System

- GPS eXchange Format

- GPS navigation device

- Global Positioning System (GPS)

- Guidance, navigation, and control

- List of auto parts

- Map database management

- Mapscape BV

- Mobile data terminal

- Navigation Data Standard (NDS)

- NavPix

- Navteq

- Personal navigation assistant (PNA)

- TomTom

- Traffic Message Channel (TMC)

- Hybride Navigation (Hybrid)

- Garmin

References

[edit]- ^ Zhao, Jianfeng; Liang, Bodong; Chen, Qiuxia (2018-01-02). "The key technology toward the self-driving car". International Journal of Intelligent Unmanned Systems. 6 (1): 2–20. doi:10.1108/IJIUS-08-2017-0008. ISSN 2049-6427.

- ^ Cartographies of Travel and Navigation, James R. Akerman, p.277

- ^ "This is the evolution of in-car navigation technology (pictures)". www.gpspower.net.

- ^ "Sat nav - without a satellite - in 1971?". BBC Archive Youtube. 21 December 2021. Retrieved 2023-12-31.

- ^ a b c d Cartographies of Travel and Navigation, James R. Akerman, p.279

- ^ "Japanese inventions that changed the way we live". CNN. 13 June 2017. Retrieved 2022-04-12.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-04-11. Retrieved 2016-04-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "IVHS: Positioning and Navigation". www.wirelesscommunication.nl.

- ^ "Toyota Crown Royal 1987". favcars.com/. Retrieved 2015-01-19.

- ^ "1990 Magna Torrero Concept Car". testdrivejunkie.com. 2012-04-04.

- ^ Motor Trend - June 1989

- ^ 4x4 & Offroad - June 1989

- ^ "1993 Eunos/Mazda Cosmo Classic Drive Uncosmopolitan: Meet the Rarest Mazda in America". Motor Trend. TEN: The Enthusiast Network. 31 January 2013. Retrieved 2015-01-18.

- ^ "GM RIDES THE SMART HIGHWAY - Chicago Tribune". www.chicagotribune.com. 31 August 1997. Retrieved 2021-04-28.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Mitsubishi DEBONAIR Commercial 1991 Japan". YouTube. 16 January 2015.

- ^ "Mit falschen Karten". Bod.de. Retrieved 2022-04-12.

- ^ "BitMAP on TV (ORF) ZIB1 - YouTube". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2020-02-27. Retrieved 2018-09-12.

- ^ "Bitmap Digital City Map". www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at.

- ^ Gulde, Dirk (15 July 2014). "20 JAHRE NAVIGATION Was ist aus ihnen geworden?". auto-motor-und-sport.de/. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- ^ "How In-Dash Navigation Worked In 1992 – Olds Was First". jesda.com/. Retrieved 2015-01-19.

- ^ "1996 Acura 3.5 RL Interior". Honda Newsroom. Archived from the original on 2018-06-16. Retrieved 2018-06-16.

- ^ "Autoradio GPS Android pas cher, Caméra radar de recul - Player Top". player-top.fr. Retrieved 2016-07-18.

- ^ "The United States' Decision to Stop Degrading Global Positioning System Accuracy". Clinton4.nara.gov. 2000-05-01. Archived from the original on 2016-12-23. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ^ "Short History of NDS" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2012-11-05.

- ^ "NDS Partners, NDS Association". NDS Association. Archived from the original on 2015-02-13. Retrieved 2015-02-13.

- ^ Palmer, Brian (2014-02-17). "How mapping software gathers and uses traffic information. The key element is you". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2019-10-08.

- ^ In-Car Positioning and Navigation Technologies—A Survey, I. Skog, and P. Händel, [1]