Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

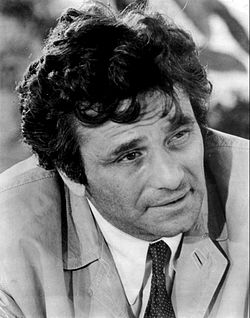

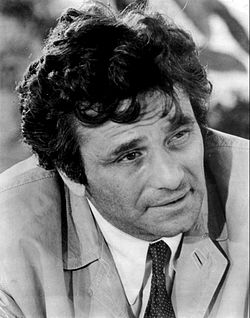

Peter Falk

View on Wikipedia

Peter Michael Falk (September 16, 1927 – June 23, 2011) was an American actor. He is best known for his role as Lieutenant Columbo on the NBC/ABC series Columbo (1968–1978, 1989–2003), for which he won four Primetime Emmy Awards (1972, 1975, 1976, 1990) and a Golden Globe Award (1973). In 1996, TV Guide ranked Falk No. 21 on its 50 Greatest TV Stars of All Time list.[1] He received a posthumous star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 2013.[2][3]

Key Information

He first starred as Columbo in two 2-hour "World Premiere" TV pilots; the first with Gene Barry in 1968 and the second with Lee Grant in 1971. The show then aired as part of The NBC Mystery Movie series from 1971 to 1978, and again on ABC from 1989 to 2003.[4]

Falk was twice nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, for Murder, Inc. (1960) and Pocketful of Miracles (1961), and won his first Emmy Award in 1962 for The Dick Powell Theatre. He was the first actor to be nominated for an Academy Award and an Emmy Award in the same year, achieving the feat twice (1961 and 1962). He went on to appear in such films as It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963), The Great Race (1965), Anzio (1968), Murder by Death (1976), The Cheap Detective (1978), The Brink's Job (1978), The In-Laws (1979), The Princess Bride (1987), Wings of Desire (1987), The Player (1992), and Next (2007), as well as many television guest roles.

Falk was also known for his collaborations with filmmaker, actor, and personal friend John Cassavetes, acting in films such as Husbands (1970), A Woman Under the Influence (1974), Big Trouble (1986), Elaine May's Mikey and Nicky (1976) and the Columbo episode "Étude in Black" (1972). He cameoed as a theatergoer in Cassavetes' 1977 film Opening Night.

Early life

[edit]

Born in Manhattan, New York City, Falk was the son of Michael Peter Falk, owner of a clothing and dry goods store, and his wife, Madeline (née Hochhauser).[5] Both his parents were Jewish.[6]

Falk's right eye was surgically removed when he was three because of a retinoblastoma.[a] He wore an artificial eye for most of his life.[7] The artificial eye was the cause of his trademark squint.[8] Despite this limitation, as a boy he participated in team sports, mainly baseball and basketball. In a 1997 interview in Cigar Aficionado magazine with Arthur Marx, Falk said:

I remember once in high school the umpire called me out at third base when I was sure I was safe. I got so mad I took out my glass eye, handed it to him and said, 'Try this.' I got such a laugh you wouldn't believe."[9]

Falk's first stage appearance was at age 12 in The Pirates of Penzance at Camp High Point[10] in upstate New York, where one of his camp counselors was Ross Martin.[b] Falk attended Ossining High School in Westchester County, New York, where he was a star athlete and president of his senior class.[11] He graduated in 1945.[12]

Falk briefly attended Hamilton College in Clinton, New York. He then tried to join the armed services, as World War II was drawing to a close. Rejected because of his missing eye, he joined the United States Merchant Marine and served as a cook and mess boy. Falk said of the experience in 1997: "There they don't care if you're blind or not. The only one on a ship who has to see is the captain. And in the case of the Titanic, he couldn't see very well, either."[9] Falk recalled in his autobiography:

A year on the water was enough for me, so I returned to college. I didn't stay long. Too itchy. What to do next? I signed up to go to Israel to fight in the war on its attack on Egypt. I wasn't passionate about Israel, I wasn't passionate about Egypt—I just wanted more excitement ... I got assigned a ship and departure date but the war was over before the ship ever sailed.[13]

After a year and a half in the Merchant Marine, Falk returned to Hamilton College and also attended the University of Wisconsin. He transferred to The New School for Social Research in New York City, which awarded him a bachelor's degree in literature and political science in 1951.

Falk traveled in Europe and worked on a railroad in Yugoslavia for six months.[14] He returned to New York, enrolling at Syracuse University,[9] but he recalled in his 2006 memoir, Just One More Thing, that he was unsure what he wanted to do with his life for years after leaving high school.[15] Falk obtained a Master of Public Administration degree at the Maxwell School of Syracuse University in 1953. The program was designed to train civil servants for the federal government, a career that Falk said in his memoir he had "no interest in and no aptitude for."[16]

Career

[edit]Early career

[edit]He applied for a job with the CIA, but he was rejected because of his membership in the Marine Cooks and Stewards Union while serving in the Merchant Marine, even though he was required to join and was not active in the union (which had been under fire for communist leanings).[17] He then became a management analyst with the Connecticut State Budget Bureau in Hartford.[18] In 1997, Falk characterized his Hartford job as "efficiency expert": "I was such an efficiency expert that the first morning on the job, I couldn't find the building where I was to report for work. Naturally, I was late, which I always was in those days, but ironically it was my tendency never to be on time that got me started as a professional actor."[9]

Stage career

[edit]

While working in Hartford, Falk joined a community theater group called the Mark Twain Masquers, where he performed in plays that included The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial, The Crucible, and The Country Girl by Clifford Odets. Falk also studied with Eva Le Gallienne, who was giving an acting class at the White Barn Theatre in Westport, Connecticut. Falk later recalled how he "lied his way" into the class, which was for professional actors. He drove down to Westport from Hartford every Wednesday, when the classes were held, and was usually late.[9] In his 1997 interview with Arthur Marx in Cigar Aficionado Magazine, Falk said of Le Gallienne: "One evening when I arrived late, she looked at me and asked, 'Young man, why are you always late?' and I said, 'I have to drive down from Hartford.'" She looked down her nose and said, "What do you do in Hartford? There's no theater there. How do you make a living acting?" Falk confessed he was not a professional actor. According to him Le Gallienne looked at him sternly and said: "Well, you should be." He drove back to Hartford and quit his job.[9] Falk stayed with the Le Gallienne group for a few months more, and obtained a letter of recommendation from Le Galliene to an agent at the William Morris Agency in New York.[9] In 1956, he left his job with the Budget Bureau and moved to Greenwich Village to pursue an acting career.[19]

Falk's first New York stage role was in an off-Broadway production of Molière's Don Juan at the Fourth Street Theatre that closed after its only performance on January 3, 1956. Falk played the second lead, Sganarelle.[20] His next theater role proved far better for his career. In May, he appeared as Rocky Pioggi at Circle in the Square in a revival of The Iceman Cometh directed by Jose Quintero, with Jason Robards playing the lead role of Theodore "Hickey" Hickman.[18][21]

Later in 1956, Falk made his Broadway debut, appearing in Alexander Ostrovsky's Diary of a Scoundrel. As the year came to an end, he appeared again on Broadway as an English soldier in Shaw's Saint Joan with Siobhán McKenna.[22] Falk continued to act in summer stock theater productions, including a staging of Arnold Schulman's A Hole in the Head, at the Colonie Summer Theatre (near Albany, NY) in July 1962; it starred Priscilla Morrill.

In 1972, Falk appeared in Broadway's The Prisoner of Second Avenue. According to film historian Ephraim Katz: "His characters derive added authenticity from his squinty gaze, the result of the loss of an eye..."[23] However, this production caused Falk a great deal of stress, both on and offstage. He struggled with memorizing a short speech, spending hours trying to memorize three lines. The next day at rehearsal, he reported behaving strangely and feeling a tingling sensation in his neck. This caught the attention of a stage manager, who told him to go "take a Valium". Only later did Falk realize he was having an anxiety attack. He would not go on to perform in any other plays, citing both this incident and his preference for acting in film and television productions.[24][25]

Early films

[edit]

Despite his stage success, a theatrical agent advised Falk not to expect much film acting work because of his artificial eye.[18] He failed a screen test at Columbia Pictures and was told by studio boss Harry Cohn: "For the same price I can get an actor with two eyes." He also failed to get a role in the film Marjorie Morningstar, despite a promising interview for the second lead.[26] His first film performances were in small roles in Wind Across the Everglades (1958), The Bloody Brood (1959), and Pretty Boy Floyd (1960). Falk's performance in Murder, Inc. (1960) was a turning point in his career. He was cast in the supporting role of killer Abe Reles in a film based on the real-life murder gang of that name who terrorized New York in the 1930s. The New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther, while dismissing the movie as "an average gangster film," singled out Falk's "amusingly vicious performance."[27] Crowther wrote:[27]

Mr. Falk, moving as if weary, looking at people out of the corners of his eyes and talking as if he had borrowed Marlon Brando's chewing gum, seems a travesty of a killer, until the water suddenly freezes in his eyes and he whips an icepick from his pocket and starts punching holes in someone's ribs. Then viciousness pours out of him and you get a sense of a felon who is hopelessly cracked and corrupt.

The film turned out to be Falk's breakout role. In his autobiography, Just One More Thing (2006), Falk said his selection for the film from thousands of other Off-Broadway actors was a "miracle" that "made my career" and that without it, he would not have received the other significant movie roles that he later played.[28] Falk, who played Reles again in the 1960 TV series The Witness, was nominated for a Best Supporting Actor Academy Award for his performance in the film.

In 1961, multiple Academy Award-winning director Frank Capra cast Falk in the comedy Pocketful of Miracles. The film was Capra's last feature, and although it was not the commercial success he hoped it would be, he "gushed about Falk's performance."[4] Falk was nominated for an Oscar for the role. In his autobiography, Capra wrote about Falk:

The entire production was agony ... except for Peter Falk. He was my joy, my anchor to reality. Introducing that remarkable talent to the techniques of comedy made me forget pains, tired blood, and maniacal hankerings to murder Glenn Ford (the film's star). Thank you Peter Falk.[29]: 480

For his part, Falk says he "never worked with a director who showed greater enjoyment of actors and the acting craft. There is nothing more important to an actor than to know that the one person who represents the audience to you, the director, is responding well to what you are trying to do." Falk once recalled how Capra reshot a scene even though he yelled "Cut and Print," indicating the scene was finalized. When Falk asked him why he wanted it reshot: "He laughed and said that he loved the scene so much he just wanted to see us do it again. How's that for support!"[4]

For the remainder of the 1960s, Falk had mainly supporting movie roles and TV guest-starring appearances. Falk portrayed one of two cabbies who falls victim to greed in the epic 1963 star-studded comedy It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, although he appears only in the last fifth of the movie. His other roles included the character of Guy Gisborne in the Rat Pack musical comedy Robin and the 7 Hoods (1964), in which he sings one of the film's numbers, and the spoof The Great Race (1965) with Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis.

Early television roles

[edit]

Falk first appeared on television in 1957, in the dramatic anthology programs that later became known as the "Golden Age of Television". In 1957, he appeared in one episode of Robert Montgomery Presents. He was also cast in Studio One, Kraft Television Theater, New York Confidential, Naked City, The Untouchables, Have Gun–Will Travel, The Islanders, and Decoy with Beverly Garland cast as the first female police officer in a series lead. Falk often portrayed unsavory characters on television during the early 1960s. In The Twilight Zone episode "The Mirror," Falk starred as a paranoid Castro-type revolutionary who, intoxicated with power, begins seeing would-be assassins in a mirror. He also starred in two of Alfred Hitchcock's television series, as a gangster terrified of death in a 1961 episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents and as a homicidal evangelist in 1962's The Alfred Hitchcock Hour.[30]

In 1961, Falk was nominated for an Emmy Award[31] for his performance in the episode "Cold Turkey" of James Whitmore's short-lived series The Law and Mr. Jones on ABC. On September 29, 1961, Falk and Walter Matthau guest-starred in the premiere episode, "The Million Dollar Dump", of ABC's crime drama Target: The Corruptors, with Stephen McNally and Robert Harland. He won an Emmy for "The Price of Tomatoes," a drama carried in 1962 on The Dick Powell Show.

In 1961, Falk earned the distinction of becoming the first actor to be nominated for an Oscar and an Emmy in the same year. He received nominations for his supporting roles in Murder, Inc. and the television program The Law and Mr. Jones. Incredibly, Falk repeated this double nomination in 1962, being nominated again for a supporting actor role in Pocketful of Miracles and best actor in "The Price of Tomatoes," an episode of The Dick Powell Show, for which he took home the award.[30]

In 1963, Falk and Tommy Sands appeared in "The Gus Morgan Story" on ABC's Wagon Train as brothers who disagreed on the route for a railroad. Falk played the title role of "Gus", and Sands was his younger brother, Ethan Morgan. After Ethan accidentally shoots wagonmaster Chris Hale, played by John McIntire, while in the mountains, Gus has to decide whether to rescue Hale or his brother (suffering from oxygen deprivation). This episode is remembered for its examination of how far a man will persist amid adversity to preserve his own life and that of his brother.[32]

Having had many roles in film and television during the early 1960s, Falk's first lead in a television series came with CBS's The Trials of O'Brien. The show ran from 1965 to 1966, its 22 episodes featuring Falk as a Shakespeare-quoting lawyer who defends clients while solving mysteries.[30] In 1966, he also co-starred in a television production of Brigadoon with Robert Goulet.

In 1971, Pierre Cossette produced the first Grammy Awards show on television with some help from Falk. Cossette writes in his autobiography, "What meant the most to me, though, is the fact that Peter Falk saved my ass. I love show business, and I love Peter Falk."[33]

Columbo

[edit]

Although Falk appeared in numerous other television roles in the 1960s and 1970s, he is best known as the star of the TV series Columbo, "everyone's favorite rumpled television detective."[4] His character, known for his catchphrase: "Just one more thing,"[34] is a shabby and deceptively absent-minded police detective driving a Peugeot 403, who had first appeared in the 1968 film Prescription: Murder. Columbo was created by William Link and Richard Levinson.[30] The show was of a type known as an inverted detective story; it typically reveals the murderer at the beginning, then shows how the Los Angeles homicide detective goes about solving the crime. Falk would describe his role to film historian and author David Fantle:

Columbo has a genuine mistiness about him. It seems to hang in the air ... [and] he's capable of being distracted ... Columbo is an ass-backwards Sherlock Holmes. Holmes had a long neck, Columbo has no neck; Holmes smoked a pipe, Columbo chews up six cigars a day.[4]

Television critic Ben Falk (no relation) added that Falk "created an iconic cop ... who always got his man (or woman) after a tortuous cat-and-mouse investigation." He also noted the idea for the character was "apparently inspired by Dostoyevsky's dogged police inspector, Porfiry Petrovich, in the novel Crime and Punishment."[35]

Peter Falk tries to analyze the character and notes the correlation between his own personality and Columbo's:

I'm a Virgo Jew, and that means I have an obsessive thoroughness. It's not enough to get most of the details; it's necessary to get them all. I've been accused of perfectionism. When Lew Wasserman (head of Universal Studios) said that Falk is a perfectionist, I don't know whether it was out of affection or because he felt I was a monumental pain in the ass.[4]

With "general amazement", Falk notes: "The show is all over the world. I've been to little villages in Africa with maybe one TV set, and little kids will run up to me shouting, 'Columbo, Columbo!'"[4] Singer Johnny Cash recalled acting in one episode ("Swan Song"), and although he was not an experienced actor, he writes in his autobiography, "Peter Falk was good to me. I wasn't at all confident about handling a dramatic role, and every day he helped me in all kinds of little ways."[36]

The first episode of Columbo as a series was directed in 1971 by a 24-year-old Steven Spielberg in one of his earliest directing jobs. Falk recalled the episode to Spielberg biographer Joseph McBride:

Let's face it, we had some good fortune at the beginning. Our debut episode, in 1971, was directed by this young kid named Steven Spielberg. I told the producers, Link and Levinson: "This guy is too good for Columbo" ... Steven was shooting me with a long lens from across the street. That wasn't common twenty years ago. The comfort level it gave me as an actor, besides it's a great look artistically—well, it told you that this wasn't any ordinary director.[37]

The character of Columbo had previously been played by Bert Freed in a 1960 television episode of The Chevy Mystery Show ("Enough Rope"), and by Thomas Mitchell on Broadway. Falk first played Columbo in Prescription: Murder, a 1968 TV movie, and the 1970 pilot for the series, Ransom for a Dead Man. From 1971 to 1978, Columbo aired regularly on NBC as part of the umbrella series NBC Mystery Movie. All episodes were of TV movie length, in a 90- or 120-minute slot including commercials. In 1989, the show returned on ABC in the form of a less frequent series of TV movies, still starring Falk, airing until 2003. Falk won four Emmys for his role as Columbo.[38]

Columbo was so popular, co-creator William Link wrote a series of short stories published as The Columbo Collection (Crippen & Landru, 2010) which includes a drawing by Falk of himself as Columbo, while the cover features a caricature of Falk/Columbo by Al Hirschfeld.[39]

Lieutenant Columbo owns a Basset Hound named Dog. Originally, it was not going to appear in the show because Peter Falk believed that it "already had enough gimmicks" but once the two met, Falk stated that Dog "was exactly the type of dog that Columbo would own", so he was added to the show and made his first appearance in 1972's "Étude In Black".[40]

Columbo's wardrobe was provided by Peter Falk; they were his own clothes, including the high-topped shoes and the shabby raincoat, which made its first appearance in Prescription: Murder. Falk would often ad lib his character's idiosyncrasies (fumbling through his pockets for a piece of evidence and discovering a grocery list, asking to borrow a pencil, becoming distracted by something irrelevant in the room at a dramatic point in a conversation with a suspect, etc.), inserting these into his performance as a way to keep his fellow actors off-balance. He felt it helped to make their confused and impatient reactions to Columbo's antics more genuine.[41] According to Levinson, the catchphrase "one more thing" was conceived when he and Link were writing the play: "we had a scene that was too short, and we'd already had Columbo make his exit. We were too lazy to retype the scene, so we had him come back and say, 'Oh, just one more thing...' It was never planned."[42]

Columbo featured an unofficial signature tune, the children's song "This Old Man". It was introduced in the episode "Any Old Port in a Storm" in 1973 and the detective can be heard humming or whistling it often in subsequent films. Peter Falk admitted that it was a melody he enjoyed, and one day it became a part of his character.[43] The tune was also used in various score arrangements throughout the three decades of the series, including opening and closing credits. A version of it, titled "Columbo", was created by one of the show's composers, Patrick Williams.[44]

A few years prior to his death, Falk had expressed interest in returning to the role. In 2007, he said he had chosen a script for one last Columbo episode, "Columbo: Hear No Evil". The script was renamed "Columbo's Last Case". ABC declined the project. In response, producers for the series attempted to shop the project to foreign production companies.[45][46] However, Falk was diagnosed with dementia in late 2007. Falk died on June 23, 2011, aged 83.[47][48][49]

Peter Falk won four Emmy Awards for his portrayal of Lieutenant Columbo in 1972, 1975, 1976 and 1990. Falk directed just one episode: "Blueprint for Murder" in 1971, although it is rumored that he and John Cassavetes were largely responsible for direction duties on "Étude in Black" in 1972. Falk's own favorite Columbo episodes were "Any Old Port in a Storm", "Forgotten Lady", "Now You See Him" and "Identity Crisis". Falk was rumored to be earning a record $300,000 per episode when he returned for season 6 of Columbo in 1976.[50] This doubled to $600,000 per episode when the series made its comeback in 1989. In 1997, "Murder by the Book" was ranked at No. 16 in TV Guide's '100 Greatest Episodes of All Time' list. Two years later, the magazine ranked Lieutenant Columbo No. 7 on its '50 Greatest TV Characters of All Time' list.[51]

Later career

[edit]

Falk was a close friend of independent film director John Cassavetes and appeared in his films Husbands, A Woman Under the Influence, and, in a cameo, at the end of Opening Night. Cassavetes guest-starred in the Columbo episode "Étude in Black" in 1972; Falk, in turn, co-starred with Cassavetes in Elaine May's film Mikey and Nicky (1976). Falk describes his experiences working with Cassavetes, specifically remembering his directing strategies: "Shooting an actor when he might be unaware the camera was running."

You never knew when the camera might be going. And it was never: 'Stop. Cut. Start again.' John would walk in the middle of a scene and talk, and though you didn't realize it, the camera kept going. So I never knew what the hell he was doing. [Laughs] But he ultimately made me, and I think every actor, less self-conscious, less aware of the camera than anybody I've ever worked with.[52]

In 1978, Falk appeared on the comedy TV show The Dean Martin Celebrity Roast, portraying his Columbo character, with Frank Sinatra the evening's victim.[53] Director William Friedkin said of Falk's role in his film The Brink's Job (1978): "Peter has a great range from comedy to drama. He could break your heart or he could make you laugh."[54]

Falk continued to work in films, including his performance as an ex-CIA officer of questionable sanity in the comedy The In-Laws. Director Arthur Hiller said during an interview that the "film started out because Alan Arkin and Peter Falk wanted to work together. They went to Warner Brothers and said, 'We'd like to do a picture,' and Warner said fine ... and out came The In-laws ... of all the films I've done, The In-laws is the one I get the most comments on."[54]: 290 Movie critic Roger Ebert compared the film with a later remake:

Peter Falk and Alan Arkin in the earlier film, versus Michael Douglas and Albert Brooks this time ... yet the chemistry is better in the earlier film. Falk goes into his deadpan lecturer mode, slowly and patiently explaining things that sound like utter nonsense. Arkin develops good reasons for suspecting he is in the hands of a madman.[55]

Falk appeared in The Great Muppet Caper, The Princess Bride, Murder by Death, The Cheap Detective, Vibes, Made, and in Wim Wenders' 1987 German language film Wings of Desire and its 1993 sequel, Faraway, So Close!. In Wings of Desire, Falk played a semi-fictionalized version of himself, a famous American actor who had once been an angel, but who had grown disillusioned with only observing life on Earth and had in turn given up his immortality. Falk described the role as "the craziest thing that I've ever been offered", but he earned critical acclaim for his supporting performance in the film.[56]

In 1998, Falk returned to the New York stage to star in an Off-Broadway production of Arthur Miller's Mr. Peters' Connections. His previous stage work included shady real estate salesman Shelley "the Machine" Levine in the 1986 Boston/Los Angeles production of David Mamet's prizewinning Glengarry Glen Ross.[57] Falk starred in a trilogy of holiday television movies – A Town Without Christmas (2001), Finding John Christmas (2003), and When Angels Come to Town (2004) – in which he portrayed Max, a quirky guardian angel who uses disguises and subterfuge to steer his charges onto the right path. In 2005, he starred in The Thing About My Folks. Although movie critic Roger Ebert was not impressed with most of the other actors, he wrote in his review: "... We discover once again what a warm and engaging actor Peter Falk is. I can't recommend the movie, but I can be grateful that I saw it, for Falk."[58] In 2007, Falk appeared with Nicolas Cage in the thriller Next.

Falk's autobiography, Just One More Thing, was published in 2006.[30]

Personal life

[edit]

Falk married Alyce Mayo, whom he met when the two were students at Syracuse University,[59] on April 17, 1960. The couple adopted two daughters, Catherine (who became a private investigator) and Jackie. Falk and his wife divorced in 1976. On December 7, 1977, he married actress Shera Danese,[60] who guest-starred in more episodes of the Columbo series than any other actress.

Falk was an accomplished artist, and in October 2006 he had an exhibition of his drawings at the Butler Institute of American Art.[61] He took classes at the Art Students League of New York for many years.[62][63]

Falk was a chess aficionado and a spectator at the American Open in Santa Monica, California, in November 1972, and at the U.S. Open in Pasadena, California, in August 1983.[64]

His memoir Just One More Thing (ISBN 978-0-78671795-8) was published by Carroll & Graf on August 23, 2006.

Health

[edit]

In December 2008, it was reported that Falk had been diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease.[65] In June 2009, at a two-day conservatorship trial in Los Angeles, one of Falk's personal physicians, Dr. Stephen Read, reported he had rapidly slipped into dementia after a series of dental operations in 2007.[66] Read said it was unclear whether Falk's condition had worsened as a result of anesthesia or some other reaction to the operations. Shera Danese Falk was appointed as her husband's conservator.[67]

Death

[edit]On the evening of June 23, 2011, Falk died at his longtime home on Roxbury Drive in Beverly Hills at the age of 83.[68][69] The causes of death were pneumonia and Alzheimer's disease.[70] His daughters said they would remember his "wisdom and humor".[71] He is buried at Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery in Los Angeles, California.[72]

His death was marked by tributes from many film celebrities including Jonah Hill and Stephen Fry.[73][74] Steven Spielberg said, "I learned more about acting from him at that early stage of my career than I had from anyone else".[75] Rob Reiner said: "He was a completely unique actor", and went on to say that Falk's work with Alan Arkin in The In-Laws was "one of the most brilliant comedy pairings we've seen on screen".[76] His epitaph reads: "I'm not here, I'm home with Shera."[77]

Peter Falk's Law

[edit]According to Falk's daughter Catherine, his second wife Shera Danese (who also was his conservator) allegedly stopped some of his family members from visiting him; did not notify them of major changes in his condition; and did not notify them of his death and funeral arrangements.[78] Catherine encouraged the passage in 2015 of legislation called colloquially "Peter Falk's Law".[78] The new law was passed in New York state to protect children from being cut off from news of serious medical and end-of-life developments regarding their parents or from contact with them. The law provides guidelines regarding visitation rights and notice of death with which an incapacitated person's guardians or conservators must comply.[79][60][80][81]

As of 2020, more than fifteen states had enacted such laws.[82] In introducing the measure, New York State Senator John DeFrancisco said, "For every wrong there should be a remedy. This bill gives a remedy to children of elderly and infirm parents who have been cut off from receiving information about their parents. It also gives them an avenue through the courts to obtain visitation rights with the parents."[83]

Filmography

[edit]Film

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1958 | Wind Across the Everglades | Writer | film debut |

| 1959 | The Bloody Brood | Nico | |

| 1960 | Pretty Boy Floyd | Shorty Walters | |

| Murder, Inc. | Abe Reles | Academy Award nomination | |

| The Secret of the Purple Reef | Tom Weber | ||

| 1961 | Pocketful of Miracles | Joy Boy | Academy Award nomination |

| 1962 | Pressure Point | Young Psychiatrist | |

| 1963 | The Balcony | Police Chief | |

| It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World | Third Cab Driver | ||

| 1964 | Robin and the 7 Hoods | Guy Gisborne | |

| Attack and Retreat | Medic Captain | ||

| 1965 | The Great Race | Maximilian Meen | |

| 1966 | Penelope | Lieutenant Horatio Bixbee | |

| 1967 | Luv | Milt Manville | |

| Too Many Thieves | Danny | ||

| 1968 | Anzio | Corporal Jack Rabinoff | |

| 1969 | Machine Gun McCain | Charlie Adamo | |

| Castle Keep | Sergeant Rossi | ||

| 1970 | Operation Snafu | Peter Pawney | |

| Husbands | Archie Black | ||

| 1974 | A Woman Under the Influence | Nick Longhetti | |

| 1976 | Griffin and Phoenix | Geoffrey Griffin | |

| Murder by Death | Sam Diamond | ||

| Mikey and Nicky | Mikey | ||

| 1977 | Opening Night | Himself | Cameo appearance, uncredited |

| 1978 | The Cheap Detective | Lou Peckinpaugh | |

| The Brink's Job | Tony Pino | ||

| Scared Straight! | Himself – Narrator | ||

| 1979 | The In-Laws | Vincent J. Ricardo | |

| 1981 | The Great Muppet Caper | Tramp | |

| ...All the Marbles | Harry Sears | ||

| 1986 | Big Trouble | Steve Rickey | |

| 1987 | Wings of Desire | Himself | |

| Happy New Year | Nick | ||

| The Princess Bride | Grandfather / Narrator | ||

| 1988 | Vibes | Harry Buscafusco | |

| 1989 | Cookie | Dominick "Dino" Capisco | |

| 1990 | In the Spirit | Roger Flan | |

| Tune in Tomorrow | Pedro Carmichael | ||

| 1992 | Faraway, So Close! | Himself | |

| The Player | |||

| 1995 | Roommates | Rocky Holzcek | |

| Cops n Roberts | Salvatore Santini | ||

| 1998 | Money Kings | Vinnie Glynn | |

| 2000 | Lakeboat | The Pierman | |

| Enemies of Laughter | Paul's Father | ||

| 2001 | Hubert's Brain | Thompson | Voice |

| Made | Max | ||

| Corky Romano | Francis A. "Pops" Romano | ||

| 2002 | Three Days of Rain | Waldo | |

| Undisputed | Mendy Ripstein | ||

| 2004 | Shark Tale | Don Ira Feinberg | Voice, cameo |

| 2005 | Checking Out | Morris Applebaum | |

| The Thing About My Folks | Sam Kleinman | ||

| 2007 | Three Days to Vegas | Gus 'Fitzy' Fitzgerald | |

| Next | Irv | ||

| 2009 | American Cowslip | Father Randolph | Final film role |

Television

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1957 | Robert Montgomery Presents | Season 8 Episode 36: "Return Visit" | |

| Studio One | Carmen's Assistant | Season 9 Episode 35: "The Mother Bit" | |

| Jack | Season 9 Episode 45: "Rudy" | ||

| Kraft Suspense Theatre | Radar Operator / Izzy | Season 10 Episode 26: "Collision" | |

| 1957–59 | Camera Three | Stendhal / Don Chucho | 8 episodes |

| 1958 | Naked City | Extortionist | Season 1 Episode 11: "Lady Bug, Lady Bug" |

| Kraft Suspense Theatre | Izzy | Season 11 Episode 44: "Night Cry" | |

| Decoy | Fred Dana | Season 1 Episode 37: "The Come Back" | |

| 1959 | Omnibus | Charlie | Season 7 Episode 13: "The Strange Ordeal of the Normandier" |

| Brenner | Fred Gaines | Season 1 Episode 4: "Blind Spot" | |

| Deadline | Al Bax | Season 1 Episode 11: "The Human Storm" | |

| New York Confidential | Pete | Season 1 Episode 11: "The Girl from Nowhere" | |

| Play of the Week | Mestizo | Season 1 Episode 2: "The Power and the Glory" | |

| 1960 | Season 1 Episode 14: "The Emperor's Clothes" | ||

| Naked City | Gimpy (uncredited) | Season 2 Episode 1: "A Death of Princes" | |

| The Islanders | Hooker | Season 1 Episode 6: "Hostage Island" | |

| Have Gun – Will Travel | Waller, Gambler | Season 4 Episode 9: "The Poker Fiend" | |

| The Witness | Abe Reles | Season 1 Episode 11: "Kid Twist" | |

| The Untouchables | Duke Mullen | Season 1 Episode 26: "The Underworld Bank" | |

| 1961 | Nate Selko | Season 3 Episode 1: "Troubleshooter" | |

| Naked City | Lee Staunton | Season 2 Episode 24: "A Very Cautious Boy" | |

| The Law and Mr. Jones | Sydney Jarmon | Season 1 Episode 20: "Cold Turkey" | |

| The Aquanauts | Jeremiah Wilson | Season 1 Episode 20: "The Jeremiah Adventure" | |

| Angel | Season 1 Episode 23: "The Double Adventure" | ||

| Cry Vengeance! | Priest | Television movie | |

| The Million Dollar Incident | Sammy | ||

| Alfred Hitchcock Presents | Meyer Fine | Season 6 Episode 28: "Gratitude" | |

| The Barbara Stanwyck Show | Joe | Season 1 Episode 32: "The Assassin" | |

| Target: The Corruptors! | Nick Longo | Season 1 Episode 1: "The Million Dollar Dump" | |

| The Twilight Zone | Ramos Clemente | Season 3 Episode 6: "The Mirror" | |

| 1962 | Naked City | Frankie O'Hearn | Season 3 Episode 25: "Lament for a Dead Indian" |

| The New Breed | Lopez | Season 1 Episode 15: "Cross the Little Line" | |

| 87th Precinct | Greg Brovane | Season 1 Episode 19: "The Pigeon" | |

| Here's Edie | Cabbie | Episode #1.1 | |

| The Alfred Hitchcock Hour | Robert Evans | Season 1 Episode 13: "Bonfire" | |

| The Dick Powell Show | Aristede Fresco | Season 1 Episode 17: "Price of Tomatoes" | |

| Dr. Alan Keegan | Season 2 Episode 4: "The Doomsday Boys" | ||

| The DuPont Show of the Week | Collucci | Season 1 Episode 24: "A Sound of Hunting" | |

| 1963 | The Dick Powell Show | Martin | Season 2 Episode 18: "The Rage of Silence" |

| Dr. Kildare | Matt Gunderson | Season 2 Episode 29: "The Balance and the Crucible" | |

| Wagon Train | Gus Morgan | Season 7 Episode 3: "The Gus Morgan Story" | |

| Bob Hope Presents the Chrysler Theatre | Bert Graumann | Season 1 Episode 4: "Four Kings" | |

| 1964 | The DuPont Show of the Week | Danilo Diaz | Season 3 Episode 21: "Ambassador at Large" |

| Ben Casey | Dr. Jimmy Reynolds | Season 4 Episode 6: "For Jimmy, the Best of Everything" | |

| Season 4 Episode 12: "Courage at 3:00 A.M." | |||

| 1965 | Bob Hope Presents the Chrysler Theatre | Bara | Season 2 Episode 19: "Perilous Times" |

| 1965–66 | The Trials of O'Brien | Daniel O'Brien | 22 episodes |

| 1966 | Bob Hope Presents the Chrysler Theatre | Mike Galway | Season 4 Episode 7: "Dear Deductible" |

| Brigadoon | Jeff Douglas | Television movie | |

| 1967 | The Red Skelton Hour | Colonel Hush-Hush | Season 16 Episode 16: "In One Head and Out the Other" |

| 1968 | A Hatful of Rain | Polo Pope | Television movie |

| 1968–2003 | Columbo | Lieutenant Columbo | 69 episodes |

| 1971 | The Name of the Game | Lewis Corbett | Season 3 Episode 15: "A Sister from Napoli" |

| A Step Out of Line | Harry Connors | Television movie | |

| 1978 | The Dean Martin Celebrity Roast | Columbo | Television special |

| 1992 | The Larry Sanders Show | Himself | Season 1 Episode 8: "Out of the Loop" |

| 1996 | The Sunshine Boys | Willie Clark | Television movie |

| 1997 | Pronto | Harry Arno | |

| 2000 | A Storm in Summer | Abel Shaddick | |

| 2001 | The Lost World | Reverend Theo Kerr | |

| A Town Without Christmas | Max | ||

| 2003 | Finding John Christmas | ||

| Wilder Days | James 'Pop Up' Morse | ||

| 2004 | When Angels Come to Town | Max | Television movie (final TV role) |

Theatre

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Venue |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1956 | Saint Joan | English Soldier | Walter Kerr Theatre, Broadway |

| Diary of a Scoundrel | Mamaev's Servant | Phoenix Theatre, off-Broadway | |

| 1956–57 | The Iceman Cometh | Rocky Pioggi | Circle in the Square Theatre, Broadway |

| 1964 | The Passion of Josef D. | Stalin | Ethel Barrymore Theatre, Broadway |

| 1971–73 | The Prisoner of Second Avenue | Mel Edison | Eugene O'Neill Theatre, Broadway |

| 2000 | Defiled | Brian Dickey | Geffen Playhouse, Los Angeles |

Awards and nominations

[edit]| Year | Category | Nominated work | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | Best Supporting Actor | Murder, Inc. | Nominated | [84] |

| 1961 | Pocketful of Miracles | Nominated | [85] |

| Year | Category | Nominated work | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primetime Emmy Awards | ||||

| 1961 | Outstanding Performance in a Supporting Role by an Actor or Actress in a Single Program | The Law and Mr. Jones (Episode: "Cold Turkey") | Nominated | [86] |

| 1962 | Outstanding Single Performance by an Actor in a Leading Role | The Dick Powell Show (Episode: "The Price of Tomatoes") | Won | |

| 1972 | Outstanding Continued Performance by an Actor in a Leading Role in a Dramatic Series | Columbo | Won | |

| 1973 | Outstanding Continued Performance by an Actor in a Leading Role (Drama Series – Continuing) | Nominated | ||

| 1974 | Best Lead Actor in a Limited Series | Nominated | ||

| 1975 | Outstanding Lead Actor in a Limited Series | Won | ||

| 1976 | Outstanding Lead Actor in a Drama Series | Won | ||

| 1977 | Nominated | |||

| 1978 | Nominated | |||

| 1990 | Won | |||

| 1991 | Nominated | |||

| 1994 | Nominated | |||

| Daytime Emmy Awards | ||||

| 2001 | Outstanding Performer in a Children's Special | A Storm in Summer | Nominated | [87] |

| Year | Category | Nominated work | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1961 | Most Promising Newcomer – Male | Murder, Inc. | Nominated | [88] |

| 1971 | Best Actor in a Television Series – Drama | Columbo | Nominated | |

| 1972 | Won | |||

| 1973 | Nominated | |||

| 1974 | Nominated | |||

| 1975 | Nominated | |||

| 1977 | Nominated | |||

| 1990 | Nominated | |||

| 1991 | Best Actor in a Miniseries or Motion Picture Made for Television | Columbo and the Murder of a Rock Star | Nominated | |

| 1993 | Columbo: It's All in the Game | Nominated |

Other Awards

[edit]| Year | Award | Category | Nominated work | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | AARP Movies for Grownups Awards | Best Grownup Love Story | The Thing About My Folks | Nominated | [87] |

| 1976 | Bambi Awards | TV Series International | Columbo | Won | |

| 1993 | Won | ||||

| 1975 | Bravo Otto | Best Male TV Star | — | Nominated | |

| 2004 | David di Donatello Awards | Golden Plate | — | Won | [89] |

| 2005 | Florida Film Festival | Lifetime Achievement Award | — | Won | [87] |

| 1972 | Golden Apple Awards | Male Star of the Year | — | Won | |

| 1976 | Goldene Kamera | Best German Actor | Columbo | Won | [90] |

| 1974 | Hasty Pudding Theatricals | Man of the Year | — | Won | [91] |

| 1962 | Laurel Awards | Top Male New Personality | — | Nominated | [87] |

| 2003 | Method Fest Independent Film Festival | Lifetime Achievement Award | — | Won | |

| 2006 | Milan Film Festival | Best Actor | The Thing About My Folks | Won[c] | [92] |

| 2006 | Online Film & Television Association Awards | Television Hall of Fame: Actors | — | Inducted | [93] |

| 2021 | Television Hall of Fame: Characters | Lt. Columbo (from Columbo) | Inducted | [94] | |

| 1989 | People's Choice Awards | Favorite Male TV Performer | — | Nominated | [87] |

| 1990 | — | Nominated | |||

| 1974 | Photoplay Awards | Favorite Male Star | — | Nominated | |

| 1976 | Favorite Movie | Murder by Death | Nominated | ||

| 2002 | Stinkers Bad Movie Awards | Worst Supporting Actor | Undisputed | Nominated | [95] |

| 2005 | TV Land Awards | Favorite "Casual Friday" Cop | Columbo | Nominated | [87] |

Other Honors

[edit]| Year | Honor | Category | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | Hollywood Walk of Fame | Television | Inducted | [96] |

Bibliography

[edit]- Falk, Peter (2006), Just One More Thing: Stories from My Life, New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, ISBN 0-7867-1795-5.

Further reading

[edit]- Richard A. Lertzman & William J Birnes (2017). Beyond Columbo: The life and times of Peter Falk. Shadow Lawn Press. ISBN 978-1-521-88149-1

Notes

[edit]- ^ This fact is alluded to in the 1997 Columbo episode "A Trace of Murder" (Series 13, episode 2), where Detective Columbo invites a colleague to help interview a suspect, stating, "three eyes are better than one".

- ^ They later acted together in The Great Race and the Columbo episode "Suitable For Framing".

- ^ Tied with Josh Hartnett for Lucky Number Slevin.

References

[edit]- ^ TV Guide: Guide to TV. Barnes & Noble. 2004. p. 596. ISBN 978-0-7607-5634-8.

- ^ "Peter Falk posthumously honored with star on Hollywood Walk of Fame". ABC7. July 26, 2013. Retrieved September 21, 2024.

- ^ "Peter Falk". Hollywood Star Walk. Los Angeles Times. July 25, 2013. Retrieved September 21, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fantle, David; Johnson, Tom (2004). Twenty-Five Years of Celebrity Interviews. Badger Books. pp. 216–17.

- ^ "Jerry Tallmer: Just 79 more things". NYC plus. September 16, 1927. Retrieved June 26, 2011.

- ^ "Peter Falk, TV's Rumpled 'Columbo' for More Than Three Decades, Dies at 83". Bloomberg. June 24, 2011.

- ^ "Peter Falk". thebiographychannel.co.uk. Bio. (UK). Archived from the original on June 10, 2009. Retrieved January 30, 2009.

- ^ "Peter Falk Biography". Biography. Archived from the original on January 19, 2019. Retrieved January 9, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g Marx, Arthur (November–December 1997). "Talk with Falk". Cigar Aficionado. Archived from the original on January 27, 2010. Retrieved February 2, 2009.

- ^ "Famous Alumni". Camp High Point. Retrieved October 18, 2010.

- ^ "Peter Falk – aka, Lieutenant Columbo". Ossining History on the Run. July 24, 2023. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ "Ossining High School Hall of Fame and Museum seeks oldest living OHS graduate". Ossining-Croton-On-Hudson, NY Patch. October 18, 2012. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ Falk 2006, p. 20.

- ^ Falk 2006, p. 26.

- ^ Falk 2006, p. 17.

- ^ Falk 2006, p. 29.

- ^ Falk 2006, p. 32.

- ^ a b c "Peter Falk Biography". peterfalk.com. Peter Falk. Archived from the original on January 30, 2009. Retrieved January 30, 2009.

- ^ "Peter Falk Biography". Official website of Peter Falk. Archived from the original on December 5, 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ Falk 2006, p. 42.

- ^ "Peter Falk". Internet Off Broadway Database. Lortel Archives, Lucille Lortel Foundation. Archived from the original on July 20, 2009. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ Peter Falk at the Internet Broadway Database

- ^ Katz, Ephraim. The Film Encyclopedia, HarperCollins (1998) p. 436

- ^ Kramer, Carol (February 6, 1972). "The 'Conceit' of Playing Lt. Columbo". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ^ "Peter Falk admitted that one form of acting gave him an anxiety attack". Me-TV Network. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ^ Falk 2006, pp. 51–55.

- ^ a b Crowther, Bosley (June 29, 1960). "Screen: 'Murder, Inc.': Story of Brooklyn Mob Retold at the Victoria". The New York Times. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ Falk 2006, p. 76.

- ^ Capra, Frank. The Name Above the Title: an Autobiography, Macmillan (1971)

- ^ a b c d e "16 fascinating facts about Peter Falk and 'Columbo'". Decades.com. June 23, 2011. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- ^ "Peter Falk". Television Academy.

- ^ "The Gus Morgan Story". The A.V. Club. August 12, 2010. Retrieved May 23, 2012.

- ^ Cossette, Pierre. Another Day in Showbiz, ECW Press (2002) p. 182

- ^ "Actor Peter Falk, TV's Columbo, Dies". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. June 26, 2011.

- ^ Falk, Ben. Television's Strangest Moments, Chrysalis Books (2005) p. 103

- ^ Cash, Johnny (1997). Cash: the Autobiography. Harper Collins. p. 197. ISBN 9780062515001.

- ^ McBride, Joseph. Steven Spielberg: A Biography, Simon and Schuster (1997) p. 191

- ^ "Actor Peter Falk dies at 83". Xinhua. June 25, 2011. Archived from the original on August 7, 2011. Retrieved June 25, 2011.

- ^ Link, William (May 2010). The Columbo Collection by William Link. Crippen & Landru Publishers. ISBN 978-1-932009-94-1. Archived from the original on March 19, 2017.

- ^ "A Lieutenant's best friend: Columbo and Dog". The Columbophile. July 24, 2016. Retrieved August 16, 2019.

- ^ Falk, Peter (August 24, 2007). Just One More Thing. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-7867-1939-6.

- ^ Dawidziak, Mark (November 1, 2019). The Columbo Phile: A Casebook (30th Anniversary ed.). Ohio: Commonwealth Book Company. p. 29. ISBN 978-1948986120.

- ^ "Columbo Sounds & Themes". Retrieved February 13, 2012.

- ^ "Columbo". ClassicThemes.com. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ "With aging Falk, 'Columbo' looks like a closed case". Daily News. New York. March 27, 2007. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ "A mystery Columbo can't seem to crack". Cleveland.com. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ Krystal, Becky (June 24, 2011). "Peter Falk of 'Columbo' dies at 83". Washington Post. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- ^ Marikar, Sheila (June 24, 2011). "Peter Falk, 'Columbo' Actor, Dies at 83". ABC News. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ "Peter Falk". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- ^ McWhiter, Norris (1981). Guinness Book of Records 1982. Guinness Superlatives Ltd. p. 113. ISBN 0-85112-232-9.

- ^ "Columbo facts". Columbophile.com. April 11, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- ^ Carney, Raymond. The Films of John Cassavetes, Cambridge Univ. Press (1994) p. 296

- ^ "Lt. Columbo Roasts Frank Sinatra (1978)", video clip

- ^ a b Emery, Robert J (2002). The Directors: Take Two. Allworth Press. p. 263. ISBN 9781581152197.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. Roger Ebert's Movie Yearbook 2006, Andrews McMeel Publ. (2006) p. 325

- ^ Kenny, J.M.; Wenders, Wim (2009). The Angels Among Us (Blu-ray). The Criterion Collection.

- ^ Coakley, Michael (March 2, 1986). "Peter Falk: TV's Rumpled Columbo Goes Legit In Mamet's "Glengarry"". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. Roger Ebert's Movie Yearbook 2009, Andrews McMeel Publ. (2009) p. 676

- ^ Falk 2006, p. 30.

- ^ a b Kim, Victoria (May 28, 2009). "Relatives Fight For Control of 'Columbo' Star Peter Falk". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 28, 2009.

- ^ Pinchot, Joe (October 2006). "It's all about the pose: actor Peter Falk keeps his drawings simple". The Sharon Herald. Retrieved June 26, 2011.

- ^ Litt, Steven (June 24, 2011) [October 10, 2006]. "My Interview with Peter Falk". The Plain Dealer. Cleveland. Retrieved June 26, 2011.

- ^ "Former Prominent Students, The Art Students League of New York". Theartstudentsleague.org. Retrieved June 26, 2011.

- ^ "Peter Falk, American Open, Santa Monica, November 1972, and United States Open, Pasadena, California, August 1983". Chess history.

- ^ Singh, Anita (December 16, 2008). "Columbo star Peter Falk has Alzheimer's". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022.

- ^ Anthony McCartney (June 1, 2009). ""Columbo" Actor Peter Falk Placed In Conservatorship". The Huffington Post. Associated Press. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016. Retrieved October 18, 2010.

- ^ "'Columbo' Star Peter Falk Dead at 83". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on January 2, 2014.

- ^ Bruce Weber (June 24, 2011). "Peter Falk, Rumpled and Crafty Actor In Television's "Columbo", Dies at 83". The New York Times.

- ^ Nick Allen. "Peter Falk" The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ "Peter Falk's Official Cause Of Death Revealed". PerezHilton.com. November 7, 2011. Archived from the original on August 29, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2012.

- ^ ""Columbo" actor Peter Falk dead at 83". Reuters. June 24, 2011. Retrieved June 26, 2011.

- ^ Taylor-Rosner, Noémie (February 15, 2017). Portraits de Los Angeles. Hikari Editions. ISBN 9782367740386.

- ^ "Tweets of the Week: Peter Falk Edition". The Wall Street Journal. June 24, 2011. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ "Celebrities mourn Peter Falk on Twitter". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ "Peter Falk's friends and co-stars pay tribute to the late actor". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ "Remembering TV's rumpled Columbo". The Daily News Egypt. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ "Peter Falk (1927–2011) – Find a Grave Memorial". findagrave.com. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ a b "Catherine Falk Organization – Peter Falk's Law: Right of Association Legislation". Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ "Peter Falk's Law Becomes a Reality in New York". esslawfirm.com. October 18, 2019.

- ^ "The Catherine Falk Story". Catherine Falk Organization. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- ^ Falk, Christine (February 23, 2016). "Letter of Catherine Falk (undated) annexed to Testimony to the House Committee on Judiciary (25 Feb. 2016) by Moira T. Chin, Office of the Public Guardian" (PDF). capitol.hawaii.gov. Hawai'i State Legislature. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ "Peter Falk Columbo's Estate Dispute". hackardlaw.com. August 13, 2018.

- ^ "Senate Passes Legislation to Protect Senior Citizens from Abuse and Exploitation". The New York State Senate. June 15, 2015. Archived from the original on May 16, 2020. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- ^ "The 33rd Academy Awards (1961) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. October 5, 2014. Archived from the original on October 15, 2015. Retrieved May 4, 2015.

- ^ "The 34th Academy Awards (1962) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. October 5, 2014. Archived from the original on February 15, 2015. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ^ "Peter Falk". Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. Retrieved November 5, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f "Peter Falk – Awards". IMDb. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ "Peter Falk". Golden Globe Awards. Retrieved November 5, 2024.

- ^ "Peter Falk". David di Donatello. Retrieved November 5, 2024.

- ^ "The award winners 1976". Goldene Kamera. November 27, 2023. Retrieved November 5, 2024.

- ^ "Past Men and Women of the Year". Hasty Pudding Theatricals. Retrieved November 5, 2024.

- ^ "History | Miff Awards". www.miffawards.com. Archived from the original on September 13, 2022. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ^ "Television Hall of Fame: Actors". Online Film & Television Association. Retrieved November 5, 2024.

- ^ "Television Hall of Fame: Productions". Online Film & Television Association. Retrieved November 5, 2024.

- ^ "Winners – 2002 Stinkers Bad Movie Awards". Stinkers Bad Movie Awards. Archived from the original on November 12, 2006. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ "Peter Falk". Hollywood Walk of Fame. July 25, 2013. Retrieved November 5, 2024.

External links

[edit]- Peter Falk at IMDb

- Peter Falk at the Internet Broadway Database

- Peter Falk at the Internet Off-Broadway Database (archived)

- Peter Falk at the TCM Movie Database

- Peter Falk on Charlie Rose

- Peter Falk discography at Discogs

- Peter Falk collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- "'Just One More Thing' About Falk, TV's 'Columbo'". Fresh Air. June 27, 2011. NPR. Transcript.

- Peter Falk at Emmys.com

- Peter Falk at Find a Grave

Peter Falk

View on GrokipediaEarly Life and Education

Childhood Adversity and Family Background

Peter Falk was born on September 16, 1927, in New York City to Michael Peter Falk (1898–1981), who owned a clothing and dry goods store, and Madeline Falk (née Hochhauser; 1904–2001), an accountant.[5][1] Both parents were Jewish, with Eastern European immigrant heritage tracing to Poland, Russia, and Hungary.[6] The family, which included no other children, later settled in Ossining, New York, where Falk spent his formative years on Prospect Avenue.[7][8] A primary adversity in Falk's early childhood occurred at age three, when his right eye was surgically removed due to retinoblastoma, a malignant tumor.[1][9] He adapted to a prosthetic eye thereafter, developing a distinctive squint that became a personal and professional trademark, though contemporary accounts indicate this did not significantly impede his childhood activities or social integration within his working-class Jewish community.[1][10] No additional major family hardships or economic struggles are documented in primary biographical records from this period.Academic Pursuits and Formative Experiences

Falk briefly attended Hamilton College in Clinton, New York, following his high school graduation in 1945, before enlisting as a cook in the Merchant Marine for approximately 18 months.[7] Upon returning, he enrolled at the University of Wisconsin and subsequently transferred to the New School for Social Research in New York City, where he earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in political science in 1951.[11][12] In 1953, Falk completed a Master of Public Administration degree at the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at Syracuse University, a program focused on training public sector efficiency analysts.[13][14] This graduate work built on his undergraduate studies in political science and reflected an initial career orientation toward government management and policy analysis, though Falk later pivoted to acting after brief professional stints in public service.[11] During his university years, Falk's experiences were marked by interruptions from military-related service and transfers between institutions, contributing to a delayed but completed formal education in public administration fields.[7] These academic pursuits provided foundational knowledge in governance and bureaucracy, elements that would subtly inform his portrayals of authority figures in later roles, though no direct contemporaneous involvement in theater or arts programs is documented from this period.[12]Pre-Acting Professional Life

Government Employment

Falk initially aspired to a career in federal intelligence after earning a bachelor's degree in political science and government from the University of Wisconsin in 1951, applying unsuccessfully for a position with the Central Intelligence Agency.[15] He subsequently obtained a role as a management analyst with the Connecticut State Budget Bureau in Hartford, where his duties centered on efficiency analysis for state operations, a position he later self-described as that of an "efficiency expert."[16] [17] During his approximately two years in this government post, Falk balanced administrative work with extracurricular acting pursuits, joining the local Mark Twain Maskers theater group to hone his skills in community productions.[14] The job provided financial stability amid his early professional uncertainties, including a prior certification as a public accountant, but it did not fully satisfy his growing theatrical ambitions.[1] In 1955, Falk resigned from the Budget Bureau at age 28 to dedicate himself entirely to acting, relocating to New York City for formal training and off-Broadway opportunities.[17] This transition marked the end of his brief foray into public sector employment, which he reflected upon as a pragmatic but ultimately unfulfilling interlude before his entertainment career took precedence.[18]Military Service and Post-War Transition

Falk attempted to enlist in the U.S. armed forces toward the end of World War II in 1945 but was rejected due to his prosthetic right eye, which had been removed at age three to halt the spread of retinoblastoma.[19][14] Undeterred, he joined the United States Merchant Marine, serving as a cook and mess boy, roles that accommodated his physical limitation while contributing to wartime logistics efforts.[2][14] This service, though not in combat branches, exposed him to maritime operations amid the conflict's closure, providing practical experience in disciplined, hierarchical environments.[20] Following his discharge from the Merchant Marine, Falk leveraged benefits akin to the G.I. Bill to pursue higher education, reflecting a pragmatic shift from wartime aspirations to structured civilian development.[14] He briefly enrolled at Hamilton College in Clinton, New York, before transferring to the University of Wisconsin for one semester and ultimately completing a Bachelor of Arts in political science at Syracuse University in 1951.[14] This academic path, funded by service-related entitlements, marked his transition into public administration interests, laying groundwork for subsequent roles in probation and parole systems rather than immediate entertainment pursuits.[14]Acting Career Beginnings

Stage Debuts and Theater Training

Falk's theater training began informally while employed as a management analyst for the Connecticut State Budget Bureau in Hartford during the mid-1950s. There, he joined the amateur Mark Twain Masquers community theater group, participating in multiple productions including The Caine Mutiny Court Martial, which provided his initial practical experience in stage performance.[21][22] Seeking more structured instruction, Falk enrolled in a summer drama class at the White Barn Theatre in Westport, Connecticut, led by renowned actress and director Eva Le Gallienne; he gained admission by falsely claiming professional status, as the course was restricted to experienced actors.[23][24] Le Gallienne recognized his potential and advised him to commit fully to acting, leading Falk to quit his stable government job in 1956 and move to New York City.[7][22] His stage debuts predated this professional pivot: at age 12, he appeared in The Pirates of Penzance during a summer camp production in upstate New York, and in high school at Ossining High School, he played a detective role shortly before graduation, an early indicator of his aptitude for investigative characters.[25][26] Falk's professional New York debut occurred in 1956 with off-Broadway and Broadway appearances, including a minor role as an English soldier in George Bernard Shaw's Saint Joan at the Phoenix Theatre and parts in Diary of a Scoundrel.[27][17] These early efforts, though small, marked his transition to full-time theater amid the competitive Off-Broadway scene.[28]Early Off-Broadway and Regional Roles

Falk's professional stage debut occurred on January 3, 1956, in an Off-Broadway production of Molière's Don Juan at the Fourth Street Theatre, adapted by Peter Vanel and directed by Walter Beakel, where he appeared alongside Albert Paulson and Bronia Stefan; the production closed after a single performance.[29] Later that year, he joined the acclaimed Off-Broadway revival of Eugene O'Neill's The Iceman Cometh at Circle in the Square, directed by José Quintero, portraying the bartender Rocky Pioggi in a cast featuring Jason Robards as Theodore Hickman.[30] [31] This production, which ran for over 200 performances and marked a significant revival of O'Neill's work, elevated Falk's visibility in New York theater circles, drawing praise for its ensemble intensity and Quintero's direction.[19] These early Off-Broadway appearances built on Falk's prior training at the New School for Social Research and informal study with Eva Le Gallienne, establishing him in the vibrant but precarious ecosystem of experimental and classical revivals that characterized mid-1950s Manhattan theater outside the commercial Broadway district.[18] While specific regional theater engagements prior to these New York roles remain sparsely documented, Falk's initial focus remained on the city's intimate venues, where low-budget productions allowed emerging actors like him to hone naturalistic techniques amid economic constraints.[19] His roles in Don Juan and The Iceman Cometh emphasized character-driven parts requiring physical expressiveness, compensating for his glass eye and leveraging his distinctive intensity, which later informed his screen persona.[18]Film Career

Breakthrough Films and Oscar Nominations

Falk's entry into feature films came with the 1960 gangster drama Murder, Inc., directed by Burt Balaban and Stuart Rosenberg, where he portrayed Abe Reles, a ruthless enforcer for the real-life Murder Incorporated syndicate led by Louis "Lepke" Buchalter.[32] The film, released on May 23, 1960, dramatized the syndicate's operations in 1930s Brooklyn, drawing from historical accounts of organized crime's contract killing arm, which was responsible for an estimated 400 murders.[32] Falk's performance as the volatile, informant-turning Reles marked his screen debut in a major role, showcasing his ability to blend menace with vulnerability, and earned him a nomination for Best Actor in a Supporting Role at the 33rd Academy Awards on April 17, 1961.[3] This recognition, despite competition from established stars like Peter Ustinov who won for Spartacus, propelled Falk from stage and television obscurity to Hollywood notice, with critics praising his intensity as a standout in an otherwise uneven production.[33] Building on this momentum, Falk appeared in Frank Capra's final directorial effort, Pocketful of Miracles, released December 18, 1961, playing Joy Boy, the scheming right-hand man to a New York gangster (Glenn Ford) in this sentimental comedy about a hobo (Bette Davis) whose luck turns miraculously.[34] Falk's portrayal of the oily, fast-talking mobster provided comic relief amid the film's Capra-corn optimism, contrasting his prior dramatic turn and demonstrating versatility.[35] The role secured his second consecutive Academy Award nomination for Best Actor in a Supporting Role at the 34th Oscars on April 9, 1962, where he lost to George Chakiris for West Side Story, but the back-to-back nods affirmed his rising status.[3] These films represented Falk's breakthrough by transitioning him from off-Broadway theater to substantive cinematic parts, garnering critical acclaim for his naturalistic delivery and expressive eyes—assets undimmed by his glass prosthetic left eye—while establishing him as a character actor adept at playing complex antagonists.[34]Supporting Roles in Major Pictures

Peter Falk delivered a brief but energetic performance as the Third Cab Driver in Stanley Kramer's 1963 epic comedy It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, an ensemble film featuring Spencer Tracy, Milton Berle, and Sid Caesar among others, centered on a chaotic cross-country pursuit of buried treasure. His role involved a tense taxi standoff that heightened the film's frenetic pace.[36] In Blake Edwards' 1965 road race comedy The Great Race, Falk portrayed Max, the dim-witted and loyal aide to Jack Lemmon's heroic racer The Great Leslie, engaging in sabotage schemes against rivals Tony Curtis and Natalie Wood across continents. The character's bumbling antagonism added to the film's extravagant slapstick sequences.[37] Falk played Lieutenant Horatio Bixbee, a shrewd police detective investigating a bank heist, in Arthur Hiller's 1966 crime comedy Penelope, opposite Natalie Wood as the kleptomaniac protagonist and Ian Bannen as her husband.[38] His portrayal of the lieutenant, marked by streetwise dialogue, provided comic relief and investigative drive in the caper narrative.[39] In Neil Simon's 1976 parody Murder by Death, directed by Robert Moore, Falk starred as Sam Diamond, a trench-coated private investigator spoofing Humphrey Bogart's hard-boiled archetypes, navigating a mansion murder mystery with suspects played by Peter Sellers, David Niven, and Truman Capote.[40] The role showcased Falk's gravelly voice and cynical demeanor amid the film's send-ups of detective tropes.[41] Falk appeared as the Grandfather, a warm narrator reading a fairy-tale book to his skeptical grandson (Fred Savage), in Rob Reiner's 1987 fantasy-adventure The Princess Bride, framing the story's sword fights, romance, and miracles involving Cary Elwes, Robin Wright, and Mandy Patinkin.[42] His gentle, storytelling delivery became one of the film's most endearing elements.Later Film Appearances

In the 1980s, Falk took on supporting roles that highlighted his wry, everyman charm in diverse genres. In Vibes (1988), he portrayed Harry Buscafusco, a quirky psychic sidekick aiding two reluctant mediums on a quest for mystical artifacts in Ecuador.[43] That same year, he collaborated with director Wim Wenders on Wings of Desire (1987, released in the U.S. in 1988), playing a meta-fictional version of himself as a former angel who sacrificed immortality to become a Hollywood actor, offering existential counsel to invisible angels observing human life in divided Berlin.[44] [45] The film's poetic exploration of mortality and choice drew acclaim for Falk's understated presence, bridging his detective persona with philosophical depth.[46] Falk also featured prominently in Rob Reiner's The Princess Bride (1987), as the Grandfather narrating a swashbuckling fairy tale of romance, revenge, and giants to his reluctant grandson, Peter Savage.[42] This framing device, delivered with gentle humor and affection, anchored the film's blend of parody and sincerity, contributing to its enduring popularity as a family adventure.[43] Into the 1990s and 2000s, Falk's film work shifted toward eclectic character parts amid his Columbo commitments. He played radio host Pedro Carmichael in Tune in Tomorrow... (1990), a satirical comedy about a novelist disrupting a New Orleans broadcast with absurd scripts.[47] In Faraway, So Close! (1993), Wenders' sequel to Wings of Desire, Falk reprised his angelic-turned-human figure, aiding protagonists in post-Wall Berlin amid supernatural turmoil.[44] Later credits included the boxing drama Undisputed (2002) as promoter Mendy Ripstein, facilitating a prison inmate showdown; the mob comedy Made (2001); and the spoof Corky Romano (2001), where he appeared as a mafia don.[48] Falk voiced the fish Don Feinberg in the animated Shark Tale (2004), a underwater crime tale featuring celebrity voices.[49] His final screen role came in American Cowslip (2009), portraying recovering alcoholic Stanley, in a low-budget drama about rural redemption.[50] These appearances, though sporadic, showcased Falk's versatility beyond television, often in films blending humor, pathos, and cultural commentary.Television Career

Initial Television Guest Spots

Falk's television career commenced in 1957 amid the waning years of live anthology programming, a format emblematic of the era's "Golden Age of Television," where actors honed skills in unscripted, high-stakes broadcasts. His earliest documented appearance was on CBS's Studio One in the episode "The Mother Bit," directed by Norman Felton, followed later that year by "Rudy," in which he portrayed the character Jack.[51][52] These minor roles showcased his emerging intensity, though the live format demanded precision under pressure, with no opportunity for retakes. Also in 1957, he appeared in NBC's Kraft Television Theatre episode "Collision," playing a radar operator in a drama centered on naval intrigue. By 1959, Falk secured a guest spot as Pete in the syndicated crime series New York Confidential, an episode titled "The Girl from Nowhere," delving into urban underworld elements. He also featured in Decoy, a short-lived NBC series starring Beverly Garland as an undercover operative, including the episode "The Comeback," which highlighted his ability to embody gritty, streetwise figures. Transitioning into the 1960s, Falk portrayed Nate Selko, a low-level hoodlum entangled in banking schemes, in season 1, episode 26 ("The Underworld Bank") of ABC's The Untouchables on April 21, 1960.[53] He returned to the series in 1961 for the season 3 premiere "The Troubleshooter," again as a mob enforcer navigating gambling rackets.[54] A pivotal moment arrived on January 16, 1962, with his guest lead in "The Price of Tomatoes," an episode of NBC's The Dick Powell Theatre. Falk played Aristede Fresco, a cunning Sicilian produce smuggler willing to kill to protect his operation amid U.S.-Mexico border tensions. This performance earned him the 1962 Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Single Performance by an Actor in a Leading Role, outshining nominees like Lee Marvin in Alcoa Premiere.[55] The role's blend of menace and pathos—Fresco's ruthless pragmatism clashing with fleeting vulnerability—signaled Falk's versatility in antagonist parts, drawing from his theater background while amplifying his screen presence through distinctive physicality and vocal inflections. Critics noted the episode's taut scripting by Robert Van Scoyk, which leveraged Falk's intensity to drive the narrative of extortion and betrayal.[56] These guest spots, often in crime and drama genres, built Falk's profile through recurring themes of moral ambiguity and urban decay, paving the way for larger roles. Additional early appearances included episodes of Naked City, Have Gun – Will Travel, and The Islanders, where he typically embodied extortionists or shadowy operatives, refining a persona that eschewed heroism for complex antiheroes.[57] By 1963–1964, such outings in anthology formats like Kraft Suspense Theatre further solidified his television foothold, though still as a guest before transitioning to series work.Creation and Portrayal of Lieutenant Columbo

The character of Lieutenant Columbo was created by screenwriters Richard Levinson and William Link as part of their development of the inverted detective story format, in which the crime and perpetrator are revealed upfront, with the narrative focusing on the detective's methodical unraveling of the case.[58] The character debuted on television in the episode "Enough Rope" of The Chevy Mystery Show, which aired live on NBC on July 31, 1960, with Bert Freed portraying Columbo as a homicide detective investigating a psychiatrist's plot to murder his wife.[59] [60] Levinson and Link expanded the premise into the stage play Prescription: Murder, which premiered on Broadway at the Hudson Theatre on January 2, 1962, and ran for 406 performances; in this production, Columbo was initially played by actors including Thomas Mitchell and later Victor Jory.[61] The play retained the core plot of a psychiatrist (Roy Flemming) conspiring with his mistress to kill his wife and frame another for the crime, with Columbo exposing the scheme through persistent questioning and observation of inconsistencies.[62] Peter Falk first portrayed Columbo in the television adaptation of Prescription: Murder, a pilot film directed by Richard Irving that aired on NBC on February 20, 1968, co-starring Gene Barry as the killer; Falk's performance earned him an Emmy nomination and secured the role for the subsequent series.[63] [64] Falk was cast after auditioning for the part, bringing a unique interpretation that emphasized the detective's unassuming demeanor to contrast with his intellectual acuity.[65] In portraying Columbo, Falk incorporated personal elements, such as wearing his own weathered tan raincoat—purchased for $15 in New York City during a mid-1960s rainstorm—which became the character's signature garment, symbolizing his disregard for appearances.[65] [66] He developed mannerisms including a habitual squint (influenced by his glass right eye from childhood), head-scratching, hand-waving, and pauses for effect, often improvising dialogue to enhance the facade of befuddlement that disarmed suspects.[67] Falk also introduced recurring traits like references to his unseen wife, smoking cheap cigars, and later adopting a mongrel dog named "Dog," despite initial reservations about the addition softening the character's edge.[68] Falk's portrayal emphasized causal realism in detection, with Columbo relying on empirical observation—such as overlooked physical evidence or behavioral slips—rather than intuition, trapping killers through their overconfidence in their alibis; this approach, refined through Falk's ad-libs and insistence on script revisions, distinguished the series from conventional whodunits.[66] [69] The character's "one more thing" interruptions, often used to revisit clues feigned as forgotten, exemplified Falk's technique of building tension via apparent absent-mindedness masking relentless logic.Columbo Series Success and Longevity

The Columbo series premiered on NBC in 1971 as part of the rotating NBC Mystery Movie anthology, following pilot telefilms aired in 1968 ("Prescription for Murder") and 1971 ("Ransom for a Dead Man").[70] This format positioned Columbo alongside other detective shows like McMillan & Wife and McCloud, airing 6 to 8 episodes per season, each typically 90 minutes to two hours in length. The limited schedule prioritized quality scripting and production over volume, contributing to sustained viewer engagement by avoiding weekly repetition.[71] Critical and audience success derived primarily from its inverted "howcatchem" structure, in which the crime and perpetrator are revealed upfront, shifting focus to Lieutenant Columbo's methodical unraveling of the case through observation, persistence, and subtle psychological pressure on suspects.[72] Peter Falk's embodiment of the disheveled, cigar-chomping detective—marked by apparent absent-mindedness masking razor-sharp intellect—earned widespread praise for humanizing the procedural genre and subverting expectations of polished authority figures.[73] The series featured high-profile guest stars, often portraying sophisticated killers whose alibis Columbo dismantles, enhancing prestige and drawing top acting talent.[74] Falk received four Primetime Emmy Awards for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Drama Series (1972, 1975, 1976, 1990), while the program accumulated 13 Emmys overall, alongside Golden Globe wins for Falk in 1972 and 1973.[75] These accolades underscored the show's influence on television mystery storytelling, with its emphasis on character-driven deduction over action or forensics.[76] After 43 episodes on NBC through 1978, Columbo entered hiatus but revived on ABC in 1989, producing 24 additional episodes until 2003, totaling 69 across 35 years.[77] The revival capitalized on enduring syndication popularity and Falk's irreplaceable presence, though later seasons reflected evolving production constraints; the series concluded amid Falk's health decline but maintained cultural relevance through reruns and retrospective acclaim for its intellectual rigor and replay value.[72]Post-Columbo TV Projects