Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Colorimetry

View on WikipediaColorimetry is "the science and technology used to quantify and describe physically the human color perception".[1] It is similar to spectrophotometry, but is distinguished by its interest in reducing spectra to the physical correlates of color perception, most often the CIE 1931 XYZ color space tristimulus values and related quantities.[2]

History

[edit]The Duboscq colorimeter was invented by Jules Duboscq in 1870. [3]

Instruments

[edit]Colorimetric equipment is similar to that used in spectrophotometry. Some related equipment is also mentioned for completeness.

- A tristimulus colorimeter measures the tristimulus values of a color.[4]

- A spectroradiometer measures the absolute spectral radiance (intensity) or irradiance of a light source.[5]

- A spectrophotometer measures the spectral reflectance, transmittance, or relative irradiance of a color sample.[5][6]

- A spectrocolorimeter is a spectrophotometer that can calculate tristimulus values.

- A densitometer measures the degree of light passing through or reflected by a subject.[4]

- A color temperature meter measures the color temperature of an incident illuminant.

Tristimulus colorimeter

[edit]In digital imaging, colorimeters are tristimulus devices used for color calibration. Accurate color profiles ensure consistency throughout the imaging workflow, from acquisition to output.

Spectroradiometer, spectrophotometer, spectrocolorimeter

[edit]The absolute spectral power distribution of a light source can be measured with a spectroradiometer, which works by optically collecting the light, then passing it through a monochromator before reading it in narrow bands of wavelength.

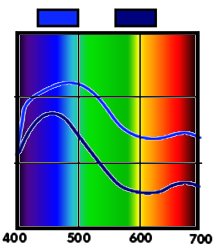

Reflected color can be measured using a spectrophotometer (also called spectroreflectometer or reflectometer), which takes measurements in the visible region (and a little beyond) of a given color sample. If the custom of taking readings at 10 nanometer increments is followed, the visible light range of 400–700 nm will yield 31 readings. These readings are typically used to draw the sample's spectral reflectance curve (how much it reflects, as a function of wavelength)—the most accurate data that can be provided regarding its characteristics.

The readings by themselves are typically not as useful as their tristimulus values, which can be converted into chromaticity co-ordinates and manipulated through color space transformations. For this purpose, a spectrocolorimeter may be used. A spectrocolorimeter is simply a spectrophotometer that can estimate tristimulus values by numerical integration (of the color matching functions' inner product with the illuminant's spectral power distribution).[6] One benefit of spectrocolorimeters over tristimulus colorimeters is that they do not have optical filters, which are subject to manufacturing variance, and have a fixed spectral transmittance curve—until they age.[7] On the other hand, tristimulus colorimeters are purpose-built, cheaper, and easier to use.[8]

The CIE (International Commission on Illumination) recommends using measurement intervals under 5 nm, even for smooth spectra.[5] Sparser measurements fail to accurately characterize spiky emission spectra, such as that of the red phosphor of a CRT display, depicted aside.

Color temperature meter

[edit]Photographers and cinematographers use information provided by these meters to decide what color balancing should be done to make different light sources appear to have the same color temperature. If the user enters the reference color temperature, the meter can calculate the mired difference between the measurement and the reference, enabling the user to choose a corrective color gel or photographic filter with the closest mired factor.[9]

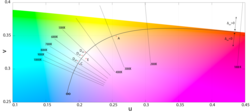

Internally the meter is typically a silicon photodiode tristimulus colorimeter.[9] The correlated color temperature can be calculated from the tristimulus values by first calculating the chromaticity co-ordinates in the CIE 1960 color space, then finding the closest point on the Planckian locus.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ohno, Yoshi (16 October 2000). CIE Fundamentals for Color Measurements (PDF). IS&T NIP16 Intl. Conf. on Digital Printing Technologies. pp. 540–45. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 May 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2009.

- ^ Gaurav Sharma (2002). Digital Color Imaging Handbook. CRC Press. pp. 15–17. ISBN 978-0-8493-0900-7.

- ^ Cal Poly Humboldthumboldt.edu Archived 8 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "ICC White Paper #5" (PDF). Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ^ a b c Lee, Hsien-Che (2005). "15.1: Spectral Measurements". Introduction to Color Imaging Science. Cambridge University Press. pp. 369–374. ISBN 0-521-84388-X.

The process recommended by the CIE for computing the tristimulus values is to use 1 nm interval or 5 nm interval if the spectral function is smooth

- ^ a b Schanda, János (2007). "Tristimulus Color Measurement of Self-Luminous Sources". Colorimetry: Understanding the CIE System. Wiley Interscience. pp. 135–157. doi:10.1002/9780470175637.ch6. ISBN 978-0-470-04904-4.

- ^ Andreas Brant, GretagMacbeth Corporate Support (7 January 2005). "Colorimeter vs. Spectro". Colorsync-users Digest. Archived from the original on 11 July 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2008.

- ^ Raymond Cheydleur, X-Rite (8 January 2005). "Colorimeter vs. Spectro". Colorsync-users Digest. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2008.

- ^ a b Salvaggio, Carl (2007). Michael R. Peres (ed.). The Focal Encyclopedia of Photography: Digital Imaging, Theory and Application (4E ed.). Focal Press. p. 741. ISBN 978-0-240-80740-9.

Further reading

[edit]- Schanda, János D. (1997). "Colorimetry" (PDF). In Casimer DeCusatis (ed.). Handbook of Applied Photometry. OSA/AIP. pp. 327–412. ISBN 978-1-56396-416-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 September 2005. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- Bala, Raja (2003). "Device Characterization" (PDF). In Gaurav Sharma (ed.). Digital Color Imaging Handbook. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-0900-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2008. Retrieved 5 May 2008.

- Gardner, James L. (May–June 2007). "Comparison of Calibration Methods for Tristimulus Colorimeters" (PDF). Journal of Research of the National Institute of Standards and Technology. 112 (3): 129–138. doi:10.6028/jres.112.010. PMC 4656001. PMID 27110460. S2CID 1949232. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2008. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- MacEvoy, Bruce (8 May 2008). "Overview of the development and applications of colorimetry". Handprint.com. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- Optronik – Photometers An informative brochure with background information and specifications of their equipment.

- Konica Minolta Sensing – Precise Color Communication – from perception to instrumentation Archived 27 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- HunterLab – FAQ | How to Measure Color of a Sample & Use An Index A guide to measuring color and appearance of objects. The section provides information on numerical scales and indices that are used throughout the world to remove subjective measurements and assumptions.

- NIST Publications related to colorimetry.

External links

[edit]- Colorlab MATLAB toolbox for color science computation and accurate color reproduction (by Jesus Malo and Maria Jose Luque, Universitat de Valencia). It includes CIE standard tristimulus colorimetry and transformations to a number of non-linear color appearance models (CIE Lab, CIE CAM, etc.).