Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Comedy film

View on Wikipedia

The comedy film is a film genre that emphasizes humor. These films are designed to amuse audiences and make them laugh.[1] Films in this genre typically have a happy ending, with dark comedy being an exception to this rule. Comedy is one of the oldest genres in film, and it is derived from classical comedy in theatre. Some of the earliest silent films were slapstick comedies, which often relied on visual depictions, such as sight gags and pratfalls, so they could be enjoyed without requiring sound. To provide drama and excitement to silent movies, live music was played in sync with the action on the screen, on pianos, organs, and other instruments.[2] When sound films became more prevalent during the 1920s, comedy films grew in popularity, as laughter could result from both burlesque situations but also from humorous dialogue.

Comedy, compared with other film genres, places more focus on individual star actors, with many former stand-up comics transitioning to the film industry due to their popularity.[3]

In The Screenwriters Taxonomy (2017), Eric R. Williams contends that film genres are fundamentally based upon a film's atmosphere, character, and story, and therefore, the labels "drama" and "comedy" are too broad to be considered a genre.[4] Instead, his taxonomy argues that comedy is a type of film that contains at least a dozen different sub-types.[5] A number of hybrid genres have emerged, such as action comedy and romantic comedy.

History

[edit]Silent film era

[edit]

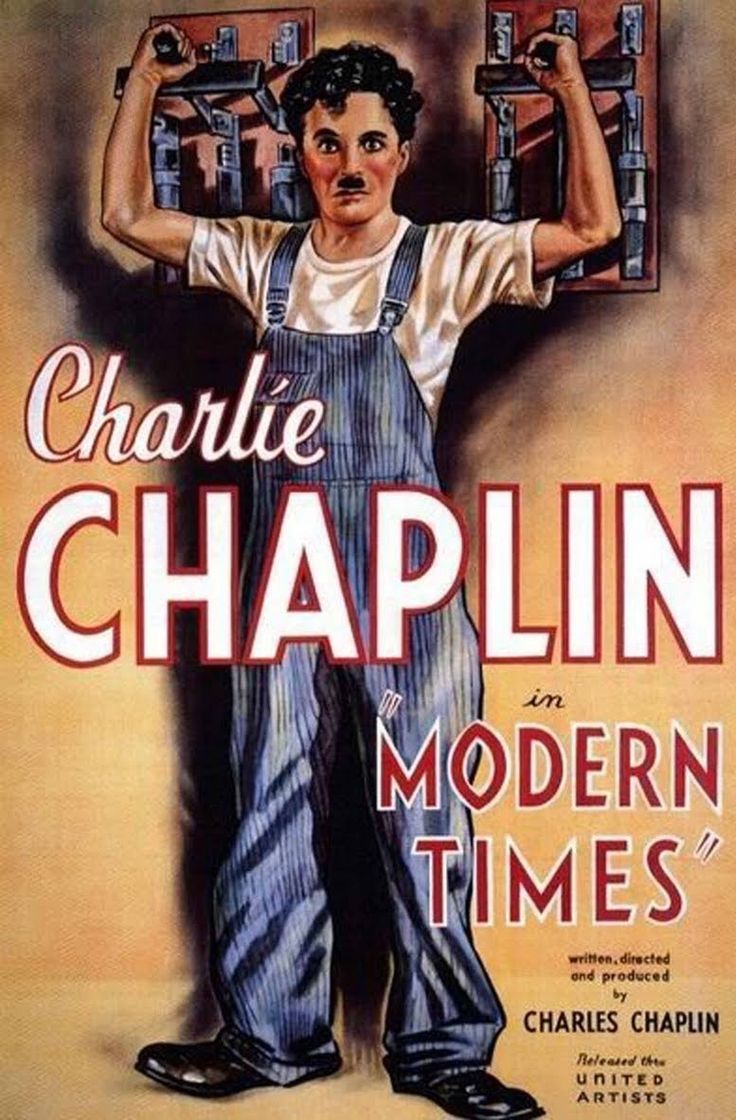

The first comedy film was L'Arroseur Arrosé (1895), directed and produced by film pioneer Louis Lumière. Less than a minute long, it shows a boy playing a prank on a gardener. The most notable comedy actors of the silent film era (1895–1927) were Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, and Buster Keaton, though they were able to make the transition into "talkies" after the 1920s.

Social commentary in comedy

[edit]Film-makers in the 1960s skillfully employed the use of comedy film to make social statements by building their narratives around sensitive cultural, political or social issues. Such films include Dr Strangelove, or How I Learned to Love the Bomb, Guess Who's Coming to Dinner? and The Graduate.[6]

Camp and bawdy comedy

[edit]In America, the sexual revolution drove an appetite for comedies that celebrated and parodied changing social morals, including Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice and Fanny Hill.[6] In Britain, a camp sensibility lay behind the successful Carry On films, while in America subversive independent film-maker John Waters made camp films for college audiences with his drag queen friends that eventually found a mainstream audience.[7] The success of the American television show Saturday Night Live drove decades of cinema with racier content allowed on television drawing on the program's stars and characters, with bigger successes including Wayne's World, Mean Girls, Ghostbusters and Animal House.[6]

Present era

[edit]Parody and joke-based films continue to find audiences.[6]

Reception

[edit]While comedic films are among the most popular with audiences at the box office, there is an 'historical bias against a close and serious consideration of comedy' when it comes to critical reception and conferring of awards, such as at the Academy Awards. Film writer Cailian Savage observes "Comedies have won Oscars, although they’ve usually been comedy-dramas, involved very depressing scenes, or appealed to stone-hearted drama lovers in some other way, such as Shakespeare in Love."

Sub-types

[edit]- Anarchic comedy: a random or stream-of-consciousness type of humor that often lampoons a form of authority.[8] The genre dates from the silent era. Notable examples are films produced by Monty Python.[9] Other examples include A Night at the Opera (1935) and Dirty Work (1998).

- Bathroom comedy (or gross-out comedy): Gross out films are often aimed at the young adult market (18–24) and rely heavily on vulgar, sexual, or "toilet" humor. They often contain a large amount of profanity and nudity.[10] Examples include Porky's (1981) and There's Something About Mary (1998).

- Black comedy: film deals with taboo subjects—including death, murder, crime, suicide, and war—in a satirical manner.[11] Examples include Do the Right Thing (1989) and In Bruges (2008).

- Comedy of ideas: This sub-type uses comedy to explore serious ideas such as religion, sex, or politics. Often, the characters represent particular divergent world views and are forced to interact for comedic effect and social commentary.[12] Some examples include both Wag the Dog (1997) and The Invention of Lying (2009).

- Comedy of manners: satirizes the mores and affectations of a social class. The plot is often concerned with an illicit love affair or other scandal. Generally, the plot is less important for its comedic effect than its witty dialogue. This form of comedy has a long ancestry that dates back at least as far as Much Ado About Nothing by William Shakespeare, published in 1623.[13] Examples include Breakfast at Tiffany's (1961) and Under the Tuscan Sun (2003).

- Farce: Farcical films exaggerate situations beyond the realm of possibility—thereby making them entertaining.[14] Examples include What's Up, Doc? (1972).

- Mockumentary: comedies are fictional but use a doc-style that includes interviews and "documentary" footage, along with regular scenes. Examples include This Is Spinal Tap (1984) and I'm Still Here (2010).

- Musical comedy: a film genre has its roots in the 1920s, with Disney's Steamboat Willie (1928) being the most popular of these early films. The subgenre resurged with popularity in the 1970s, with movies such as Bugsy Malone (1976) and Grease (1978) gaining status as cult classics.

- Observational comedy: films find humor in the common practices of everyday life.[15] Some film examples of observational humor include Purely Belter (2000) and The Big Year (2011).

- Parody (or spoof): A parody or spoof film satirizes other film genres or classic films. Such films employ sarcasm, stereotyping, mockery of scenes from other films, and the obviousness of meaning in a character's actions.[16] Examples of this form include Young Frankenstein (1974) and Airplane! (1980).

- Sex comedy: The humor is primarily derived from sexual situations and desire,[17] as in Animal House (1978) and How to Be a Latin Lover (2017).

- Sitcom: where humor comes from knowing a stock group of characters (or character types) and then exposing them to different situations to create humorous and ironic juxtaposition.[18] Examples include After Hours (1985) and Hot Tub Time Machine (2010).

- Straight comedy: This broad sub-type applies to films that do not attempt a specific approach to comedy but, rather, use comedy for comedic sake.[19] Anger Management (2003) and Bridesmaids (2011) are examples of straight comedy films.

- Slapstick film: involve exaggerated, boisterous physical action to create impossible and humorous situations. Because it relies predominantly on visual depictions of events, it does not require sound. Accordingly, the subgenre was ideal for silent movies and was prevalent during that era.[1] Stars of slapstick include Harold Lloyd, Roscoe Arbuckle, Charlie Chaplin, Peter Sellers and Norman Wisdom. Some of these stars, as well as acts such as Laurel and Hardy and the Three Stooges, also found success incorporating slapstick comedy into sound films. Modern examples of slapstick comedy include Mouse Hunt (1997) and Nacho Libre (2006).

- Surreal humor: Although not specifically linked to the history of surrealism, surreal comedies comedies include behavior and storytelling techniques that are illogical—including bizarre juxtapositions, absurd situations, and unpredictable reactions to normal situations.[19] Some examples are Brazil (1985) and Barton Fink (1991).

Hybrid sub-genres

[edit]According to Williams' taxonomy, all film descriptions should contain their type (comedy or drama) combined with one (or more) sub-genres.[5] This combination does not create a separate genre, but rather, provides a better understanding of the film.

- Action comedy: Films of this type blend comic antics and action where the stars combine one-liners with a thrilling plot and daring stunts. The genre became a specific draw in North America in the 1980s when comedians such as Eddie Murphy started taking more action-oriented roles, such as in 48 Hrs. (1982) and Beverly Hills Cop (1984).

- Sub-genres of the action comedy (labeled macro-genres by Williams) include:[5]

- Martial arts films: Slapstick martial arts films became a mainstay of Hong Kong action cinema through the work of Jackie Chan among others, such as Who Am I? (1998). Kung Fu Panda is an action comedy that focuses on the martial art of kung fu.

- Superhero films: Some action films focus on superheroes; for example, The Incredibles, Hancock, Kick-Ass, and Deadpool.

- Buddy films: Films starring mismatched partners for comedic effects, such as in Midnight Run, Rush Hour, 21 Jump Street, Bad Boys, Starsky and Hutch, Tango & Cash, Lethal Weapon, and Stakeout.

- Comedy thriller: Comedy thriller is a type that combines elements of humor and suspense. Films such as Silver Streak, Charade, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, American Psycho, Mr. and Mrs. Smith, Grosse Point Blank, The Thin Man, The Big Fix, and The Lady Vanishes.

- Comedy mystery: Comedy mystery is a film genre combining elements of comedy and mystery fiction. Though the genre arguably peaked in the 1930s and 1940s, comedy-mystery films have been continually produced since.[20] Examples include the Pink Panther series,[21]Scooby-Doo films, Clue (1985) and Knives Out (2019). See also List of comedy-mystery films

- Crime comedy: A hybrid mix of crime and comedy films, examples include Inspector Palmu's Mistake (1960), Oh Brother Where Art Thou? (2000), Take the Money and Run (1969) and Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988).

- Fantasy comedy: Fantasy comedy films use magic, supernatural or mythological figures for comedic purposes. Some fantasy comedy includes an element of parody, or satire, turning fantasy conventions on their head, such as the hero becoming a cowardly fool or the princess being a klutz. Examples of these films include Big, Being John Malkovich, Ted, Hook, Night at the Museum, Groundhog Day, Click, and A Thousand Words.

- Comedy horror: Comedy horror is a genre/type in which the usual dark themes and "scare tactics" attributed to horror films are treated with a humorous approach. These films either often goofy horror cliches, such as in Scream, The Rocky Horror Picture Show, Little Shop of Horrors, Dracula: Dead and Loving It, and Scary Movie where campy styles are favored. Some are much more subtle and do not parody horror, such as An American Werewolf in London. Another style of comedy horror can also rely on over-the-top violence and gore such as in The Evil Dead (1981), The Return of the Living Dead (1985), Braindead (1992), and Doghouse (2009) – such films are sometimes known as splatstick, a portmanteau of the words splatter and slapstick. It would be reasonable to put Ghostbusters in this category.

- Day-in-the-life comedy: Day-in-the-life films take small events in a person's life and raise their level of importance. The "small things in life" feel as important to the protagonist (and the audience) as the climactic battle in an action film, or the final shootout in a western.[5]Often, the protagonists deal with multiple, overlapping issues in the course of the film.[5] The day-in-the-life comedy often finds humor in commenting upon the absurdity or irony of daily life; for example The Terminal (2004) or Waitress (2007). Character humor is also used extensively in day-in-the-life comedies, as can be seen in American Splendor (2003).

- Romantic comedy: Romantic comedies are humorous films with central themes that reinforce societal beliefs about love (e.g., themes such as "love at first sight", "love conquers all", or "there is someone out there for everyone"); the story typically revolves around characters falling into (and out of, and back into) love.[22] Amélie (2001), Annie Hall (1977), Charade (1963), City Lights (1931), Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994), It (1927), The Lobster (2015), My Wife, the Director General (1966), My Favorite Wife (1940), Pretty Woman (1990), Some Like It Hot (1959), Something's Gotta Give (2003) and When Harry Met Sally... (1989) are examples of romantic comedies.

- Screwball comedy: A subgenre of the romantic comedy, screwball comedies appears to focus on the story of a central male character until a strong female character takes center stage; at this point, the man's story becomes secondary to a new issue typically introduced by the woman; this story grows in significance and, as it does, the man's masculinity is challenged by the sharp-witted woman, who is often his love interest.[5] Typically it can include a romantic element, an interplay between people of different economic strata, quick and witty repartee, some form of role reversal, and a happy ending. Some examples of screwball comedy during its heyday include It Happened One Night (1934), Bringing Up Baby (1938), The Philadelphia Story (1940), His Girl Friday (1940), Mr. & Mrs. Smith (1941); more recent examples include Continental Divide (1981), Rat Race (2001), and Our Idiot Brother (2011).

- Science fiction comedy: Science fiction comedy films often exaggerate the elements of traditional science fiction films to comic effect. Examples include Spaceballs, Coneheads, Galaxy Quest, Mars Attacks!, Men in Black, and many more.

- Sports comedy: Sports comedy combines the genre of comedy with that of the sports film genre. Thematically, the story is often one of "Our Team" versus "Their Team"; their team will always try to win, and our team will show the world that they deserve recognition or redemption; the story does not always have to involve a team.[4] The story could also be about an individual athlete or the story could focus on an individual playing on a team. The comedic aspect of this super-genre often comes from physical humor (BASEketball - 1998), character humor (Space Jam - 1996), or the juxtaposition of bad athletes succeeding against the odds (The Benchwarmers - 2006).

- War comedy: War films typically tell the story of a small group of isolated individuals who – one by one – get killed (literally or metaphorically) by an outside force until there is a final fight to the death; the idea of the protagonists facing death is a central expectation in a war film.[4] War comedies infuse this idea of confronting death with a morbid sense of humor. In a war film even though the enemy may out-number, or out-power, the hero, we assume that the enemy can be defeated if only the hero can figure out how.[23] Often, this strategic sensibility provides humorous opportunities in a war comedy. Examples include Good Morning, Vietnam; M*A*S*H; Stripes and others.

- Western comedy: Films in the Western super-genre often take place in the American Southwest or Mexico, with a large number of scenes occurring outside so we can soak in nature's rugged beauty.[4] Visceral expectations for the audience include fistfights, gunplay, and chase scenes. There is also the expectation of spectacular panoramic images of the countryside including sunsets, wide open landscapes, and endless deserts and sky.[5] Western comedies often find their humor in specific characters (Three Amigos, 1986), in interpersonal relationships (Lone Ranger, 2013) or in creating a parody of the western (Rango, 2011).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Comedy Films". Filmsite.org. Retrieved 29 April 2002.

- ^ Tucker, Bruce (13 December 2021). "The History of Silent Movies in the Theater". Octane Seating. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Vitale, Micaela Pérez (17 January 2022). "Stand-Up Comedians Who Became Great Actors". MovieWeb. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d Williams, Eric R. Screen adaptation: beyond the basics: techniques for adapting books, comics, and real-life stories into screenplays. Ayres, Tyler. New York. ISBN 978-1-315-66941-0. OCLC 986993829.

- ^ a b c d e f g Williams, Eric R. (2017). The Screenwriters Taxonomy: A Roadmap to Collaborative Storytelling. New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-10864-3. OCLC 993983488.

- ^ a b c d Staff (16 April 2014). "Laughs Of The Decades: A History Of Comedy In Film". Indiana University Bloomington Library. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ Marchese, David (18 March 2022). "John Waters Is Ready to Defend the Worst People in the World". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ "Absurd Comedy". Allmovies.

- ^ Sexton, Timothy. "Anarchic Comedy from the Silent Era to Monty Python". Yahoo! Movies.

- ^ Henderson, Jeffrey (1991). The maculate muse : obscene language in Attic comedy (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-802312-8. OCLC 252588785.

- ^ "Black humour". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ "Definition of Comedy of Ideas". Our Pastimes. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ British dramatists from Dryden to Sheridan. Nettleton, George Henry, 1874-1959, Case, Arthur Ellicott, 1894-1946, Stone, George Winchester, 1907-2000. (Southern Illinois University Press ed.). Carbondale, [Illinois]. 1975. ISBN 0-8093-0743-X. OCLC 1924010.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Farce | drama". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ Grable, Tim (24 February 2017). "What is funny about Observational Humor? (Updated for 2019)". The Grable Group. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ Mellon, Rory (2016). "A History of the Parody Movie". Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ McDonald, Tamar Jeffers (2007). Romantic comedy: boy meets girl meets genre. London: Wallflower. ISBN 978-0-231-50338-9. OCLC 813844867.

- ^ Dancyger, Ken. (2013). Alternative scriptwriting: beyond the Hollywood formula. Rush, Jeff. (5th ed.). Burlington, MA: Focal Press. ISBN 978-1-136-05362-7. OCLC 828423649.

- ^ a b Bown, Lesley (2011). The secrets to writing great comedy. London: Hodder Education. ISBN 978-1-4441-2892-5. OCLC 751058407.

- ^ "Film History of the 1930s". www.filmsite.org. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ "The Pink Panther: Inspector Clouseau arrives! - the Navhind Times". Archived from the original on 6 July 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ Williams, Eric R. (2019). Falling in Love with Romance Movies. Audible.

- ^ Williams, Eric R. (2018). "How to View and Appreciate Great Movies (episode 5: Story Shape and Tension)". English. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Thomas W. Bohn and Richard L. Stromgren, Light and Shadows: A History of Motion Pictures, 1975, Mayfield Publishing.

- Horton, Andrew S. (1991). Comedy/Cinema/Theory. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07040-0.

- King, Geoff (2002). Film Comedy. Wallflower Press. ISBN 978-1-903364-36-9.

- Rickman, Gregg (2004). The Film Comedy Reader. Limelight Editions. ISBN 978-0-87910-295-1.

- Weitz, Eric (2009). The Cambridge Introduction to Comedy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83260-1.

- Williams, Eric R. (2017) The Screenwriters Taxonomy: A Roadmap to Creative Storytelling. New York, NY: Routledge Press, Studies in Media Theory and Practice. ISBN 978-1-315-10864-3