Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cosmogony

View on Wikipedia

Cosmogony, also spelled as cosmogeny,[1] or cosmogenesis[2] is any model concerning the origin of the cosmos or the universe.[3][4]

Types

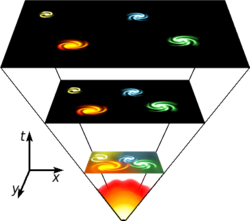

[edit]While cosmogony generally refers to origin stories, the nature and subject of these stories varies with times and sources. Ancient Greece developed a cosmogony focused on the origin of matter, space, and time with a transition from Chaos to Cosmos. This was a form of "philosophical cosmogony" that is distinct from modern empirical science but which nevertheless dealt with many similar questions.[5]: 7 Another type of cosmogony focuses on the formation and evolution of the Solar System.[4] or sometimes the formation of galaxies.[3] The standard cosmological model of the early development of the universe is the Big Bang theory,[6] but it is based on a model known to fail at the very earliest times.[7]: 275 Thus modern cosmogony is not generally a consequence of modern cosmology theories.

Scientific cosmogenesis

[edit]A Big Bang model for the dynamics of the universe is widely agreed among cosmologists. Like most physical models, Big Bang models describe changes of state. Few physical models are designed to determine initial conditions: initial states are given by experimental measurements or by hypothesis. In cosmology, the initial state would be the origin of the universe. It is considered a valid challenge to address but there are significant disagreements over even the form of acceptable answers.[8]

Initial singularity

[edit]Since the Big Bang model describes an expanding and cooling universe, it must have been denser and hotter in the past. Conceptually the model can be extrapolated back to time zero. However, this process cannot be run all the way back to time zero: the standard model assumes a density low enough to avoid quantum effects. As the model is followed to smaller times the density exceeds the validity of general relativity.[8] This point in time is called the Planck time.[citation needed]

General relativity initial state

[edit]One approach to the limitations of running Big Bang model back to time zero simply stops extrapolating when the limit of valid general relativity is reached. This model by itself fails in several ways. First, the observable universe is much more homogeneous than an extrapolated Big Bang can account for. This problem is called the horizon problem because events on opposite sides of the horizon could not have mixed in the early universe and thus should not be homogeneous now. Second, the expansion of the universe reduces curvature or equivalently increases flatness. Since the universe now is observed to be close to flat, a universe extrapolated back in time would have to be extremely flat. This almost but not quite zero curvature seems unnatural, an issue called the flatness problem. Third, this extrapolation gives poor results when compared to measurements of large scale structure and of the cosmic microwave background (CMB).[8]

Initial state theories

[edit]Several different theories have been proposed as alternative to simple extrapolation of general relativity. The most successful approach is called inflation. In this model the universe goes through a very short phase of intense expansion not predicted by general relativity. The expansion is so immense and fast that all pre-existing particles are diluted and replaced by particles emerging from the field that drove inflation in an process called reheating. An initially homogeneous universe, inflated by an enormous factor explains why we can see homogeneous features across distances which ordinary causality asserts are independent.[8] When combined with the Big Bang and other concepts of cosmology, inflation becomes the consensus or standard model of cosmology, a model which successfully predicts details of large scale structure and the CMB.[citation needed] While inflation has been successful in developing an initial state for Big Bang models, it does not by itself describe the origin of the universe. The rapid expansion erases evidence of physical processes occurring before inflation.[8]

Quantum cosmology

[edit]Sean M. Carroll, who specializes in theoretical cosmology and field theory, explains two competing explanations for the origins of the singularity, which is the center of a space in which a characteristic is limitless[9] (one example is the singularity of a black hole, where gravity is the characteristic that becomes limitless — infinite).

When the universe started to expand, the Big Bang occurred, which evidently began the universe.[citation needed] The other explanation, the Hartle–Hawking state, held by proponents such as Stephen Hawking, asserts that time did not exist when it emerged along with the universe. This assertion implies that the universe does not have a beginning, as time did not exist "prior" to the universe. Hence, it is unclear whether properties such as space or time emerged with the singularity and the known universe.[9][10][clarification needed]

Mythology

[edit]

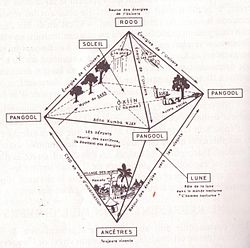

In mythology, creation or cosmogonic myths are narratives describing the beginning of the universe or cosmos.

Some methods of the creation of the universe in mythology include:

- the will or action of a supreme being or beings,

- the process of metamorphosis,

- the copulation of female and male deities,

- from chaos,

- or via a cosmic egg.[11]

Creation myths may be etiological, attempting to provide explanations for the origin of the universe. For instance, Eridu Genesis, the oldest known creation myth, contains an account of the creation of the world in which the universe was created out of a primeval sea (Abzu).[12][13] Creation myths vary, but they may share similar deities or symbols. For instance, the ruler of the gods in Greek mythology, Zeus, is similar to the ruler of the gods in Roman mythology, Jupiter.[14] Another example is the ruler of the gods in Tagalog mythology, Bathala, who is similar to various rulers of certain pantheons within Philippine mythology such as the Bisaya's Kaptan.[15][16]

Compared with cosmology

[edit]In the humanities, the distinction between cosmogony and cosmology is blurred. For example, in theology, the cosmological argument for the existence of God (pre-cosmic cosmogonic bearer of personhood) is an appeal to ideas concerning the origin of the universe and is thus cosmogonical.[17] Some religious cosmogonies have an impersonal first cause (for example Taoism).[18]

However, in astronomy, cosmogony can be distinguished from cosmology, which studies the universe and its existence, but does not necessarily inquire into its origins. There is therefore a scientific distinction between cosmological and cosmogonical ideas. Physical cosmology is the science that attempts to explain all observations relevant to the development and characteristics of the universe on its largest scale. Some questions regarding the behaviour of the universe have been described by some physicists and cosmologists as being extra-scientific or metaphysical. Attempted solutions to such questions may include the extrapolation of scientific theories to untested regimes (such as the Planck epoch), or the inclusion of philosophical or religious ideas.[10][17][6]

See also

[edit]- Anthropic principle – Hypothesis about sapient life and the universe

- Chronology of the universe – History and future of the universe

- Cosmography – Science of mapping the universe

- Ultimate fate of the universe – Theories about the end of the universe

- Why is there anything at all?

References

[edit]- ^ Halliwell, Jonathan J. (July 1989). "The dichotomy of cosmogeny". Nature. 340 (6228): 17–18. doi:10.1038/340017a0. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Layzer, David, ed. (1990). Cosmogenesis: the growth of order in the universe. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-802221-3.

- ^ a b Ridpath, Ian (2012). A Dictionary of Astronomy. Oxford University Press.

- ^ a b Woolfson, Michael Mark (1979). "Cosmogony Today". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 20 (2): 97–114. Bibcode:1979QJRAS..20...97W.

- ^ Gregory, Andrew (2007). Ancient Greek cosmogony. London: Duckworth. ISBN 978-0-7156-3477-6.

- ^ a b Wollack, Edward J. (10 December 2010). "Cosmology: The Study of the Universe". Universe 101: Big Bang Theory. NASA. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ^ Peacock, J. A. (28 December 1998). Cosmological Physics (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511804533. ISBN 978-0-521-41072-4.

- ^ a b c d e Smeenk, Christopher; Ellis, George (2017), Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), "Philosophy of Cosmology", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2017 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 16 September 2025

- ^ a b Carroll, Sean (28 April 2012). "A Universe from Nothing?". Science for the Curious. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- ^ a b Carroll, Sean; Carroll, Sean M. (2003). Spacetime and Geometry: An Introduction to General Relativity. Pearson.

- ^ Long, Charles. "Creation Myth". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ "Eridu Genesis Mesopotamia Epic". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. 20 July 1998. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- ^ Morris, Charles (1897). "The Primeval Ocean". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 49: 12–17. JSTOR 4062253.

- ^ Thury, Eva; Devinney, Margaret (2017). Introduction to Mythology Contemporary Approaches to Classical and World Myths, 4th ed. Madison Avenue, New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 4, 187.

- ^ Garverza, J. K. (2014). The Myths of the Philippines. University of the Philippines.

- ^ Jocano, F. L. (1969). Philippine Mythology. Quezon City: Capitol Publishing House Inc.

- ^ a b Smeenk, Christopher; Ellis, George (Winter 2017). "Philosophy of Cosmology". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- ^ "BBC - Religions - Taoism: Gods and spirits". www.bbc.co.uk. BBC.

External links

[edit] Media related to Cosmogony at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cosmogony at Wikimedia Commons