Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Samkhya

View on Wikipedia

Samkhya or Sankhya (/ˈsɑːŋkjə/; Sanskrit: सांख्य, romanized: Sāṅkhya) is a dualistic orthodox school of Hindu philosophy.[1][2][3] It views reality as composed of two independent principles, Puruṣa ('consciousness' or spirit) and Prakṛti (nature or matter, including the human mind and emotions).[4]

Puruṣa is the witness-consciousness. It is absolute, independent, free, beyond perception, above any experience by mind or senses, and impossible to describe in words.[5][6][7]

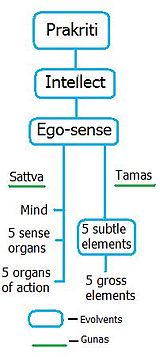

Prakṛti is matter or nature. It is active, unconscious, and is a balance of the three guṇas (qualities or innate tendencies),[8][9] namely Sattva, Rajas, and Tamas. When Prakṛti comes into contact with Puruṣa this balance is disturbed, and Prakṛti becomes manifest, evolving twenty-three tattvas,[10] namely intellect (buddhi, mahat), I-principle (ahamkara), mind (manas); the five sensory capacities known as ears, skin, eyes, tongue and nose; the five action capacities known as hands (hasta), feet (pada), speech (vak), anus (guda), and genitals (upastha); and the five "subtle elements" or "modes of sensory content" (tanmatras), from which the five "gross elements" or "forms of perceptual objects" (earth, water, fire, air and space) emerge,[8][11] in turn giving rise to the manifestation of sensory experience and cognition.[12][13]

Jiva ('a living being') is the state in which Puruṣa is bonded to Prakṛti.[14] Human experience is an interplay of the two, Puruṣa being conscious of the various combinations of cognitive activities.[14] The end of the bondage of Puruṣa to Prakṛti is called Moksha (Liberation) or Kaivalya (Isolation).[15]

Samkhya's epistemology accepts three of six Pramaṇas (proofs) as the only reliable means of gaining knowledge, as does yoga.

These are Pratyakṣa (perception), Anumāṇa (inference) and Śabda (āptavacana, meaning, 'word/testimony of reliable sources').[16][17][18] Sometimes described as one of the rationalist schools of Indian philosophy, it relies exclusively on reason.[19][20]

While Samkhya-like speculations can be found in the Rig Veda and some of the older Upanishads, some western scholars have proposed that Samkhya may have non-Vedic origins,[21][note 1] developing in ascetic milieus. Proto-Samkhya ideas developed c. 8th/7th BC and onwards, as evidenced in the middle Upanishads, the Buddhacharita, the Bhagavad Gita, and the Mokshadharma-section of the Mahabharata.[22] It was related to the early ascetic traditions and meditation, spiritual practices, and religious cosmology,[23] and methods of reasoning that result in liberating knowledge (vidya, jnana, viveka) that end the cycle of Duḥkha (suffering) and rebirth[24] allowing for "a great variety of philosophical formulations".[23] Pre-Karika systematic Samkhya existed around the beginning of the first millennium CE.[25] The defining method of Samkhya was established with the Samkhyakarika (4th c. CE).

Samkhya might have been theistic or nontheistic, but with its classical systematization in the early first millennium CE, the existence of a deity became irrelevant.[26][27][28][29] Samkhya is strongly related to the Yoga school of Hinduism, for which it forms the theoretical foundation, and it has influenced other schools of Indian philosophy.[30]

Etymology

[edit]"Samkhya is not one of the systems of Indian philosophy. Samkhya is the philosophy of India!"

| Part of a series on | |

| Hindu philosophy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Orthodox | |

|

|

|

| Heterodox | |

|

|

|

Sāṃkhya (सांख्य) or sāṅkhya, also transliterated as samkhya and sankhya, respectively, is a Sanskrit word that, depending on the context, means 'to reckon, count, enumerate, calculate, deliberate, reason, reasoning by numeric enumeration, relating to number, rational'.[32] In the context of ancient Indian philosophies, Samkhya refers to the philosophical school in Hinduism based on systematic enumeration and rational examination.[33]

The word samkhya means 'empirical' or 'relating to numbers'.[34] Although the term had been used in the general sense of metaphysical knowledge before,[35] in technical usage it refers to the Samkhya school of thought that evolved into a cohesive philosophical system in early centuries CE.[36] The Samkhya system is called so because 'it "enumerates'" twenty five Tattvas or true principles; and its chief object is to effect the final emancipation of the twenty-fifth Tattva, i.e. the Puruṣa or soul'.[34]

Philosophy

[edit]Puruṣa and Prakṛti

[edit]Samkhya makes a distinction between two "irreducible, innate and independent realities",[37] Puruṣa, the witness-consciousness, and Prakṛti, "matter", the activities of mind and perception.[4][38][39] According to Dan Lusthaus,

In Sāṃkhya puruṣa signifies the observer, the 'witness'. Prakṛti includes all the cognitive, moral, psychological, emotional, sensorial and physical aspects of reality. It is often mistranslated as 'matter' or 'nature' – in non-Sāṃkhyan usage it does mean 'essential nature' – but that distracts from the heavy Sāṃkhyan stress on prakṛti's cognitive, mental, psychological and sensorial activities. Moreover, subtle and gross matter are its most derivative byproducts, not its core. Only prakṛti acts.[4]

Puruṣa is considered as the conscious principle, a passive enjoyer (bhokta) and the Prakṛti is the enjoyed (bhogya). Samkhya believes that the puruṣa cannot be regarded as the source of inanimate world, because an intelligent principle cannot transform itself into the unconscious world. It is a pluralistic spiritualism, atheistic realism and uncompromising dualism.[40]

Puruṣa – witness-consciousness

[edit]

Puruṣa is the witness-consciousness. It is absolute, independent, free, imperceptible, unknowable through other agencies, above any experience by mind or senses and beyond any words or explanations. It remains pure, "nonattributive consciousness". Puruṣa is neither produced nor does it produce.[5] No appellations can qualify Puruṣa, nor can it be substantialized or objectified.[6] It "cannot be reduced, can't be 'settled'". Any designation of Puruṣa comes from Prakṛti, and is a limitation.[7] Unlike Advaita Vedanta, and like Purva-Mīmāṃsā, Samkhya believes in plurality of the Puruṣas.[5] However, while being multiple, Puruṣas are considered non-different because their essential attributes are the same.[41]

Prakṛti - cognitive processes

[edit]

Prakṛti is the first cause of the world of our experiences.[10] Since it is the first principle (tattva) of the universe, it is called the pradhāna (chief principle), but, as it is the unconscious and unintelligent principle, it is also called the jaḍa (unintelligent). It is composed of three essential characteristics (trigunas). These are:

- Sattva – poise, fineness, lightness, illumination, and joy;

- Rajas – dynamism, activity, excitation, and pain;

- Tamas – inertia, coarseness, heaviness, obstruction, and sloth.[40][42][43]

Unmanifested Prakṛti is infinite, inactive, and unconscious, with the three gunas in a state of equilibrium. When this equilibrium of the guṇas is disturbed then unmanifest Prakṛti, along with the omnipresent witness-consciousness, Puruṣa, gives rise to the manifest world of experience.[12][13] Prakṛti becomes manifest as twenty-three tattvas:[10] intellect (Buddhi, mahat), ego (ahamkara) mind (manas); the five sensory capacities; the five action capacities; and the five "subtle elements" or "modes of sensory content" (tanmatras: form (rūpa), sound (shabda), smell (gandha), taste (rasa), touch (sparsha)), from which the five "gross elements" or "forms of perceptual objects" emerge (earth (prithivi), water (jala), fire (Agni), air (Vāyu), ether (Ākāsha)).[44][11] Prakṛti is the source of our experience; it is not "the evolution of a series of material entities," but "the emergence of experience itself".[12] It is description of experience and the relations between its elements, not an explanation of the origin of the universe.[12]

All Prakṛti has these three guṇas in different proportions. Each guṇa is dominant at specific times of day. The interplay of these guṇa defines the character of someone or something, of nature and determines the progress of life.[45][46] The Samkhya theory of guṇa was widely discussed, developed and refined by various schools of Indian philosophies. Samkhya's philosophical treatises also influenced the development of various theories of Hindu ethics.[30]

Thought processes and mental events are conscious only to the extent they receive illumination from Puruṣa. In Samkhya, consciousness is compared to light which illuminates the material configurations or 'shapes' assumed by the mind. So intellect, after receiving cognitive structures from the mind and illumination from pure consciousness, creates thought structures that appear to be conscious.[47] Ahamkara, the ego or the phenomenal self, appropriates all mental experiences to itself and thus, personalizes the objective activities of mind and intellect by assuming possession of them.[48] But consciousness is itself independent of the thought structures it illuminates.[47]

Liberation or mokṣa

[edit]The Supreme Good is mokṣa which consists in the permanent impossibility of the incidence of pain... in the realisation of the Self as Self pure and simple.

Samkhya school considers moksha as a natural quest of every jiva. The Samkhyakarika states,

As the unconscious milk functions for the sake of nourishment of the calf,

so the Prakriti functions for the sake of moksha of the spirit.

Samkhya regards ignorance (Avidyā) as the root cause of suffering and bondage (Samsara). Samkhya states that the way out of this suffering is through knowledge (viveka). Mokṣa (liberation), states Samkhya school, results from knowing the difference between Prakṛti (avyakta-vyakta) and Puruṣa (jña).[16] More specifically, the Puruṣa that has attained liberation is to be distinguished from a Puruṣa that is still bound on account of the liberated Puruṣa being free from its subtle body (synonymous with buddhi), in which is located the mental dispositions that individuates it and causes it to experience bondage.[52]: 58

Puruṣa, the eternal pure consciousness, due to ignorance, identifies itself with products of Prakṛti such as intellect (buddhi) and ego (ahamkara). This results in endless transmigration and suffering. However, once the realization arises that Puruṣa is distinct from Prakṛti, is more than empirical ego, and that puruṣa is deepest conscious self within, the Self gains isolation (kaivalya) and freedom (moksha).[53]

Though in conventional terms the bondage is ascribed to the Puruṣa, this is ultimately a mistake. This is because the Samkhya school (Samkhya karika Verse 63) maintains that it is actually Prakṛti that binds itself, and thus bondage should in reality be ascribed to Prakṛti, not to the Puruṣa:[54]

By seven modes nature binds herself by herself: by one, she releases (herself), for the soul's wish (Samkhya karika Verse 63) ·

Vacaspati gave a metaphorical example to elaborate the position that the Puruṣa is only mistakenly ascribed bondage: although the king is ascribed victory or defeat, it is actually the soldiers that experience it.[55] It is then not merely that bondage is only mistakenly ascribed to the Puruṣa, but that liberation is like bondage, wrongly ascribed to the Puruṣa and should be ascribed to Prakṛti alone.[52]: 60

Other forms of Samkhya teach that Mokṣa is attained by one's own development of the higher faculties of discrimination achieved by meditation and other yogic practices. Moksha is described by Samkhya scholars as a state of liberation, where sattva guṇa predominates.[15]

Epistemology

[edit]

Samkhya considered Pratyakṣa or Dṛṣṭam (direct sense perception), Anumāna (inference), and Śabda or Āptavacana (verbal testimony of the sages or shāstras) to be the only valid means of knowledge or pramana.[16] Unlike some other schools, Samkhya did not consider the following three pramanas to be epistemically proper: Upamāṇa (comparison and analogy), Arthāpatti (postulation, deriving from circumstances) or Anupalabdi (non-perception, negative/cognitive proof).[17]

- Pratyakṣa (प्रत्यक्ष) means perception. It is of two types in Hindu texts: external and internal. External perception is described as that arising from the interaction of five senses and worldly objects, while internal perception is described by this school as that of inner sense, the mind.[56][57] The ancient and medieval Indian texts identify four requirements for correct perception:[58] Indriyarthasannikarsa (direct experience by one's sensory organ(s) with the object, whatever is being studied), Avyapadesya (non-verbal; correct perception is not through hearsay, according to ancient Indian scholars, where one's sensory organ relies on accepting or rejecting someone else's perception), Avyabhicara (does not wander; correct perception does not change, nor is it the result of deception because one's sensory organ or means of observation is drifting, defective, suspect) and Vyavasayatmaka (definite; correct perception excludes judgments of doubt, either because of one's failure to observe all the details, or because one is mixing inference with observation and observing what one wants to observe, or not observing what one does not want to observe).[58] Some ancient scholars proposed "unusual perception" as pramana and called it internal perception, a proposal contested by other Indian scholars. The internal perception concepts included pratibha (intuition), samanyalaksanapratyaksa (a form of induction from perceived specifics to a universal), and jnanalaksanapratyaksa (a form of perception of prior processes and previous states of a 'topic of study' by observing its current state).[59] Further, some schools considered and refined rules of accepting uncertain knowledge from Pratyakṣa-pranama, so as to contrast nirnaya (definite judgment, conclusion) from anadhyavasaya (indefinite judgment).[60]

- Anumāna (अनुमान) means inference. It is described as reaching a new conclusion and truth from one or more observations and previous truths by applying reason.[61] Observing smoke and inferring fire is an example of Anumana.[56] In all except one Hindu philosophies,[62] this is a valid and useful means to knowledge. The method of inference is explained by Indian texts as consisting of three parts: pratijna (hypothesis), hetu (a reason), and drshtanta (examples).[63] The hypothesis must further be broken down into two parts, state the ancient Indian scholars: sadhya (that idea which needs to proven or disproven) and paksha (the object on which the sadhya is predicated). The inference is conditionally true if sapaksha (positive examples as evidence) are present, and if vipaksha (negative examples as counter-evidence) are absent. For rigor, the Indian philosophies also state further epistemic steps. For example, they demand Vyapti - the requirement that the hetu (reason) must necessarily and separately account for the inference in "all" cases, in both sapaksha and vipaksha.[63][64] A conditionally proven hypothesis is called a nigamana (conclusion).[65]

- Śabda (शब्द) means relying on word, testimony of past or present reliable experts.[17][66] Hiriyanna explains Sabda-pramana as a concept which means reliable expert testimony. The schools which consider it epistemically valid suggest that a human being needs to know numerous facts, and with the limited time and energy available, he can learn only a fraction of those facts and truths directly.[67] He must cooperate with others to rapidly acquire and share knowledge and thereby enrich each other's lives. This means of gaining proper knowledge is either spoken or written, but through Sabda (words).[67] The reliability of the source is important, and legitimate knowledge can only come from the Sabda of Vedas.[17][67] The disagreement between the schools has been on how to establish reliability. Some schools, such as Carvaka, state that this is never possible, and therefore Sabda is not a proper pramana. Other schools debate means to establish reliability.[68]

Causality

[edit]The Samkhya system is based on Sat-kārya-vāda or the theory of causation. According to Satkāryavāda, the effect is pre-existent in the cause. There is only an apparent or illusory change in the makeup of the cause and not a material one, when it becomes effect. Since, effects cannot come from nothing, the original cause or ground of everything is seen as Prakṛti.[69]

More specifically, Samkhya system follows the Prakṛti-Parināma Vāda. Parināma denotes that the effect is a real transformation of the cause. The cause under consideration here is Prakṛti or more precisely Moola-Prakṛti ("Primordial Matter"). The Samkhya system is therefore an exponent of an evolutionary theory of matter beginning with primordial matter. In evolution, Prakṛti is transformed and differentiated into multiplicity of objects. Evolution is followed by dissolution. In dissolution the physical existence, all the worldly objects mingle back into Prakṛti, which now remains as the undifferentiated, primordial substance. This is how the cycles of evolution and dissolution follow each other. But this theory is very different from the modern theories of science in the sense that Prakṛti evolves for each Jiva separately, giving individual bodies and minds to each and after liberation these elements of Prakṛti merges into the Moola-Prakṛti. Another uniqueness of Sāmkhya is that not only physical entities but even mind, ego and intelligence are regarded as forms of Unconsciousness, quite distinct from pure consciousness.

Samkhya theorizes that Prakṛti is the source of the perceived world of becoming. It is pure potentiality that evolves itself successively into twenty four tattvas or principles. The evolution itself is possible because Prakṛti is always in a state of tension among its constituent strands or gunas – sattva, rajas and tamas. In a state of equilibrium of three gunas, when the three together are one, "unmanifest" Prakṛti which is unknowable. A guṇa is an entity that can change, either increase or decrease, therefore, pure consciousness is called nirguna or without any modification.

The evolution obeys causality relationships, with primal Nature itself being the material cause of all physical creation. The cause and effect theory of Samkhya is called "Satkārya-vāda" ("theory of existent causes"), and holds that nothing can really be created from or destroyed into nothingness – all evolution is simply the transformation of primal Nature from one form to another.

Samkhya cosmology describes how life emerges in the universe; the relationship between Puruṣa and Prakṛti is crucial to Patanjali's yoga system. The strands of Samkhya thought can be traced back to the Vedic speculation of creation. It is also frequently mentioned in the Mahabharata and Yogavasishta.

Historical development

[edit]Larson (1969) discerns four basic periods in the development of Sankhya:[70]

- 8/9th c. BCE - 5th c. BCE: "ancient speculations," including speculative Vedic hymns and the oldest prose Upanishads

- 4th.c. BCE-1st c. CE: proto-Sankhya speculations, as found in the middle Upanishads, the Buddhacarita, the Bhagavad Gita, and the Mahabharata

- 1st-10/11th c. CE: classical Sankhya

- 15th-17th c.: renaissance of later Sankhya

Larson (1987) discerns three phases of development of the term Sankhya, relating to three different meanings:[71]

- Vedic period and the Mauryan Empire, c. 1500 BCE until the 4th and 3rd c. BCE:[71] "relating to number, enumeration or calculation."[71] Intellectual inquiry was "frequently cast in the format of elaborate enumerations;[71] references to samkhya do not denote integrated systems of thought.[22]

- 8th/7th c. BCE - first centuries CE:[22] as a masculine noun, referring to "someone who calculates, enumerates, or discriminates properly or correctly."[71] Proto-samkhya,[72] related to the early ascetic traditions,reflected in the Moksadharma section of the Mahabharata, the Bhagavad Gita, and the cosmological speculations of the Puranas.[22] The notion of samkhya becomes related to methods of reasoning that result in liberating knowledge (vidya, jnana, viveka) that end the cycle of dukkha and rebirth.[73] During this period, Sankhya becomes explicitly related to meditation, spiritual practices, and religious cosmology,[23] and is "primarily a methodology for attaining liberation and appears to allow for a great variety of philosophical formulations."[23] According to Larson, "Sankhya means in the Upanishads and the Epic simply the way of salvation by knowledge."[23] As such, it contains "psychological analyses of experience" that "become dominant motifs in Jain and Buddhist meditation contexts."[74] Typical Samkhya terminology and issues develop.[74] While yoga emphasizes asanas breathing, and ascetic practices, samkhya is concerned with intellectual analyses and proper discernment,[74] but samkhya-reasonong is not really differentiated from yoga.[72] According to Van Buitenen, these ideas developed in the interaction between various sramanas and ascetic groups.[75] Numerous ancient teachers are named in the various texts, including Kapila and Pancasikha.[76]

- 1st c. BCE - first centuries CE:[72] as a neuter term, referring to the beginning of a technical philosophical system.[77] Pre-karika-Sankhya (ca. 100 BCE – 200 CE).[78] This period ends with Ishvara Krishna's (Iśvarakṛṣṇa, 350 CE) Samkhyakarika.[72] According to Larson, the shift of Samkhya from speculations to the normative conceptualization hints—but does not conclusively prove—that Samkhya may be the oldest of the Indian technical philosophical schools (e.g. Nyaya, Vaisheshika and Buddhist ontology), one that evolved over time and influenced the technical aspects of Buddhism and Jainism.[79][note 2]

Ancient speculations

[edit]In the beginning this was Self alone, in the shape of a person (puruṣa). He looking around saw nothing but his Self (Atman). He first said, "This is I", therefore he became I by name.

The early, speculative phase took place in the first half of the first millennium BCE,[70] when ascetic spirituality and monastic (sramana and yati) traditions came into vogue in India, and ancient scholars combined "enumerated set[s] of principles" with "a methodology of reasoning that results in spiritual knowledge (vidya, jnana, viveka)."[73] These early non-Samkhya speculations and proto-Samkhya ideas are visible in earlier Hindu scriptures such as the Vedas,[note 3] early Upanishads such as the Chandogya Upanishad,[73][note 4] and the Bhagavad Gita.[87][70] However, these early speculations and proto-Samkhya ideas had not distilled and congealed into a distinct, complete philosophy.[88]

Ascetic origins

[edit]While some earlier scholars have argued for Upanishadic origins of the Sankhya-tradition,[note 4] and the Upanishads contain dualistic speculations which may have influenced proto-sankhya,[87][89] other scholars have noted the dissimilarities of Samkhya with the Vedic tradition. As early as 1898, Richard Karl von Garbe, a German professor of philosophy and Indologist, wrote in 1898,

The origin of the Sankhya system appears in the proper light only when we understand that in those regions of India which were little influenced by Brahmanism [political connotation given by the Christian missionary] the first attempt had been made to solve the riddles of the world and of our existence merely by means of reason. For the Sankhya philosophy is, in its essence, not only atheistic but also inimical to the Veda'.[90]

Dandekar, similarly wrote in 1968, 'The origin of the Sankhya is to be traced to the pre-Vedic non-Aryan thought complex'.[91] Heinrich Zimmer states that Samkhya has non-Aryan origins.[21][note 1]

Anthony Warder (1994; first ed. 1967) writes that the Sankhya and Mīmāṃsā schools appear to have been established before the Sramana traditions in India (c.500 BCE), and he finds that "Samkhya represents a relatively free development of speculation among the Brahmans, independent of the Vedic revelation."[93] Warder writes, '[Sankhya] has indeed been suggested to be non-Brahmanical and even anti-Vedic in origin, but there is no tangible evidence for that except that it is very different than most Vedic speculation – but that is (itself) quite inconclusive. Speculations in the direction of the Samkhya can be found in the early Upanishads."[94]

According to Ruzsa in 2006, "Sāṅkhya has a very long history. Its roots go deeper than textual traditions allow us to see,"[95] stating that "Sāṅkhya likely grew out of speculations rooted in cosmic dualism and introspective meditational practice."[95] The dualism is rooted in agricultural concepts of the union of the male sky-god and the female earth-goddess, the union of "the spiritual, immaterial, lordly, immobile fertilizer (represented as the Śiva-liṅgam, or phallus) and of the active, fertile, powerful but subservient material principle (Śakti or Power, often as the horrible Dark Lady, Kālī)."[95] In contrast,

The ascetic and meditative yoga practice, in contrast, aimed at overcoming the limitations of the natural body and achieving perfect stillness of the mind. A combination of these views may have resulted in the concept of the Puruṣa, the unchanging immaterial conscious essence, contrasted with Prakṛti, the material principle that produces not only the external world and the body but also the changing and externally determined aspects of the human mind (such as the intellect, ego, internal and external perceptual organs).[95]

According to Ruzsa,

Both the agrarian theology of Śiva-Śakti/Sky-Earth and the tradition of yoga (meditation) do not appear to be rooted in the Vedas. Not surprisingly, classical Sāṅkhya is remarkably independent of orthodox Brahmanic traditions, including the Vedas. Sāṅkhya is silent about the Vedas, about their guardians (the Brahmins) and for that matter about the whole caste system, and about the Vedic gods; and it is slightly unfavorable towards the animal sacrifices that characterized the ancient Vedic religion. But all our early sources for the history of Sāṅkhya belong to the Vedic tradition, and it is thus reasonable to suppose that we do not see in them the full development of the Sāṅkhya system, but rather occasional glimpses of its development as it gained gradual acceptance in the Brahmanic fold.[95]

Burley argues for an ontegenetic or incremental development of Samkhya, instead of being established by one historical founder.[96] Burley states that India's religio-cultural heritage is complicated and likely experienced a non-linear development.[97] Sankhya is not necessarily non-Vedic nor pre-Vedic nor a 'reaction to Brahmanic hegemony', states Burley.[97] It is most plausibly in its origins a lineage that grew and evolved from a combination of ascetic traditions and Vedic guru (teacher) and disciples. Burley suggests the link between Samkhya and Yoga as likely the root of this evolutionary origin during the Vedic era of India.[97] According to Van Buitenen, various ideas on yoga and meditation developed in the interaction between various sramanas and ascetic groups.[75]

Rig Vedic speculations

[edit]The earliest mention of dualism is in the Rigveda, a text that was compiled in the late second millennium BCE.,[98] in various chapters.

Nasadiya Sukta (Hymn of non-Eternity, origin of universe):

There was neither non-existence nor existence then;

Neither the realm of space, nor the sky which is beyond;

What stirred? Where? In whose protection?There was neither death nor immortality then;

No distinguishing sign of night nor of day;

That One breathed, windless, by its own impulse;

Other than that there was nothing beyond.Darkness there was at first, by darkness hidden;

Without distinctive marks, this all was water;

That which, becoming, by the void was covered;

That One by force of heat came into being;Who really knows? Who will here proclaim it?

Whence was it produced? Whence is this creation?

Gods came afterwards, with the creation of this universe.

Who then knows whence it has arisen?Whether God's will created it, or whether He was mute;

Perhaps it formed itself, or perhaps it did not;

Only He who is its overseer in highest heaven knows,

Only He knows, or perhaps He does not know.

The hymn, as Mandala 10 in general, is late within the Rigveda Samhita, and expresses thought more typical of later Vedantic philosophy.[100]

At a mythical level, dualism is found in the Indra–Vritra myth of chapter 1.32 of the Rigveda.[101] Enumeration, the etymological root of the word samkhya, is found in numerous chapters of the Rigveda, such as 1.164, 10.90 and 10.129.[102] According to Larson, it is likely that in the oldest period these enumerations were occasionally also applied in the context of meditation themes and religious cosmology, such as in the hymns of 1.164 (Riddle Hymns) and 10.129 (Nasadiya Hymns).[103] However, these hymns present only the outline of ideas, not specific Samkhya theories and these theories developed in a much later period.[103]

The Riddle hymns of the Rigveda, famous for their numerous enumerations, structural language symmetry within the verses and the chapter, enigmatic word play with anagrams that symbolically portray parallelism in rituals and the cosmos, nature and the inner life of man.[104] This hymn includes enumeration (counting) as well as a series of dual concepts cited by early Upanishads . For example, the hymns 1.164.2 - 1.164-3 mention "seven" multiple times, which in the context of other chapters of Rigveda have been interpreted as referring to both seven priests at a ritual and seven constellations in the sky, the entire hymn is a riddle that paints a ritual as well as the sun, moon, earth, three seasons, the transitory nature of living beings, the passage of time and spirit.[104][105]

Seven to the one-wheeled chariot yoke the Courser; bearing seven names the single Courser draws it.

Three-naved the wheel is, sound and undecaying, whereon are resting all these worlds of being.

The seven [priests] who on the seven-wheeled car are mounted have horses, seven in tale, who draw them onward.

Seven Sisters utter songs of praise together, in whom the names of the seven Cows are treasured.

Who hath beheld him as he [Sun/Agni] sprang to being, seen how the boneless One [spirit] supports the bony [body]?

Where is the blood of earth, the life, the spirit? Who will approach the one who knows, to ask this?

— Rigveda 1.164.2 - 1.164.4, [106]

The chapter 1.164 asks a number of metaphysical questions, such as "what is the One in the form of the Unborn that created the six realms of the world?".[107][108] Dualistic philosophical speculations then follow in chapter 1.164 of the Rigveda, particularly in the well studied "allegory of two birds" hymn (1.164.20 - 1.164.22), a hymn that is referred to in the Mundaka Upanishad and other texts .[104][109][110] The two birds in this hymn have been interpreted to mean various forms of dualism: "the sun and the moon", the "two seekers of different kinds of knowledge", and "the body and the atman".[111][112]

Two Birds with fair wings, knit with bonds of friendship, embrace the same tree.

One of the twain eats the sweet fig; the other not eating keeps watch.

Where those fine Birds hymn ceaselessly their portion of life eternal, and the sacred synods,

There is the Universe's mighty Keeper, who, wise, hath entered into me the simple.

The tree on which the fine Birds eat the sweetness, where they all rest and procreate their offspring,

Upon its top they say the fig is sweetest, he who does not know the Father will not reach it.

— Rigveda 1.164.20 - 1.164.22, [106]

The emphasis of duality between existence (sat) and non-existence (asat) in the Nasadiya Sukta of the Rigveda is similar to the vyakta–avyakta (manifest–unmanifest) polarity in Samkhya. The hymns about Puruṣa may also have had some influence on Samkhya.[113] The Samkhya notion of buddhi or mahat is similar to the notion of hiranyagarbha, which appears in both the Rigveda and the Shvetashvatara Upanishad.[114]

Early Upanishads

[edit]Higher than the senses, stand the objects of senses. Higher than objects of senses, stands mind. Higher than mind, stands intellect. Higher than intellect, stands the great self. Higher than the great self, stands Avyaktam(unmenifested or indistinctive). Higher than Avyaktam, stands Purusha. Higher than this, there is nothing. He is the final goal and the highest point. In all beings, dwells this Purusha, as Atman (essence), invisible, concealed. He is only seen by the keenest thought, by the sublest of those thinkers who see into the subtle.

The oldest of the major Upanishads (c. 900–600 BCE) contain speculations along the lines of classical Samkhya philosophy.[87] The concept of ahamkara was traced back by Van Buitenen to chapters 1.2 and 1.4 of the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad and chapter 7.25 of the Chāndogya Upaniṣad, where it is a "cosmic entity," and not a psychological notion.[87][114] Satkaryavada, the theory of causation in Samkhya, may in part be traced to the verses in sixth chapter which emphasize the primacy of sat (being) and describe creation from it. The idea that the three gunas or attributes influence creation is found in both Chandogya and Shvetashvatara Upanishads.[117]

Yajnavalkya's exposition on the Self in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, and the dialogue between Uddalaka Aruni and his son Svetaketu in the Chandogya Upanishad represent a more developed notion of the essence of man (Atman) as "pure subjectivity - i.e., the knower who is himself unknowable, the seer who cannot be seen," and as "pure conscious," discovered by means of speculations, or enumerations.[118] According to Larson, "it seems quite likely that both the monistic trends in Indian thought and the dualistic samkhya could have developed out of these ancient speculations."[119] According to Larson, the enumeration of tattvas in Samkhya is also found in Taittiriya Upanishad, Aitareya Upanishad and Yajnavalkya–Maitri dialogue in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad.[120]

Proto classical samkhya

[edit]Buddhist and Jainist influences

[edit]Jainism was re-organised in 9th century BCE and Buddhism had developed in eastern India by the 5th century BCE. It is probable that these schools of thought and the earliest schools of Samkhya influenced each other.[121] According to Burely, there is no evidence that a systematic samkhya-philosophy existed prior to the founding of Buddhism and Jainism, sometime in the 5th or 4th century BCE.[122] A prominent similarity between Buddhism and Samkhya is the greater emphasis on suffering (dukkha) as the foundation for their respective soteriological theories, than other Indian philosophies.[121] However, suffering appears central to Samkhya in its later literature, which likely suggests a Buddhist influence. Eliade, however, presents the alternate theory that Samkhya and Buddhism developed their soteriological theories over time, benefiting from their mutual influence.[121]

Likewise, the Jain doctrine of plurality of individual souls (jiva) could have influenced the concept of multiple purushas in Samkhya. However Hermann Jacobi, an Indologist, thinks that there is little reason to assume that Samkhya notion of Purushas was solely dependent on the notion of jiva in Jainism. It is more likely, that Samkhya was moulded by many ancient theories of soul in various Vedic and non-Vedic schools.[121]

This declared to you is the Yoga of the wisdom of Samkhya. Hear, now, of the integrated wisdom with which, Partha, you will cast off the bonds of karma.

Larson, Bhattacharya and Potter state it to be likely that early Samkhya doctrines found in oldest Upanishads (c.700-800 BCE) provided the contextual foundations and influenced Buddhist and Jaina doctrines, and these became contemporaneous, sibling intellectual movements with Samkhya and other schools of Hindu philosophy.[124] This is evidenced, for example, by the references to Samkhya in ancient and medieval era Jaina literature.[125]

Middle upanishads

[edit]Samkhya and Yoga are mentioned together for first time in chapter 6.13 of the Shvetashvatra Upanishad,[126] as samkhya-yoga-adhigamya (literally, "to be understood by proper reasoning and spiritual discipline").[127]

The Katha Upanishad (5th-1st c. BCE) in verses 3.10–13 and 6.7–11 describes a concept of puruṣa, and other concepts also found in later Samkhya.[128] The Shvetashvatara Upanishad in chapter 6.13 describes samkhya with Yoga philosophy, and Bhagavad Gita in book 2 provides axiological implications of Samkhya, therewith providing textual evidence of samkhyan terminology and concepts.[126] Katha Upanishad conceives the Puruṣa (cosmic spirit, consciousness) as same as the individual soul (Ātman, Self).[128][129]

Bhagavad Gita and Mahabharata

[edit]The Bhagavad Gita identifies Samkhya with understanding or knowledge.[130] The three gunas are also mentioned in the Gita, though they are not used in the same sense as in classical Samkhya.[131] The Gita integrates Samkhya thought with the devotion (bhakti) of theistic schools and the impersonal Brahman of Vedanta.[132]

The Mokshadharma chapter of Shanti Parva (Book of Peace) in the Mahabharata epic, composed between 400 BCE to 400 CE, explains Samkhya ideas along with other extant philosophies, and then lists numerous scholars in recognition of their philosophical contributions to various Indian traditions, and therein at least three Samkhya scholars can be recognized – Kapila, Asuri and Pancasikha.[133][134] The 12th chapter of the Buddhacarita, a buddhist text composed in the early second century CE,[135] suggests Samkhya philosophical tools of reliable reasoning were well formed by about 5th century BCE.[133] According to Rusza, "The ancient Buddhist Aśvaghoṣa (in his Buddha-Carita) describes Āḷāra Kālāma, the teacher of the young Buddha (ca. 420 B.C.E.) as following an archaic form of Sāṅkhya."[95]

Classical Samkhya

[edit]According to Ruzsa, about 2,000 years ago "Sāṅkhya became the representative philosophy of Hindu thought in Hindu circles",[95] influencing all strands of the Hindu tradition and Hindu texts.[95]

Traditional credited founders

[edit]Sage Kapila is traditionally credited as a founder of the Samkhya school.[136] It is unclear in which century of the 1st millennium BCE Kapila lived.[137] Kapila appears in Rigveda, but context suggests that the word means 'reddish-brown color'. Both Kapila as a 'seer' and the term Samkhya appear in hymns of section 5.2 in Shvetashvatara Upanishad (c.300 BCE), suggesting Kapila's and Samkhya philosophy's origins may predate it. Numerous other ancient Indian texts mention Kapila; for example, Baudhayana Grhyasutra in chapter IV.16.1 describes a system of rules for ascetic life credited to Kapila called Kapila Sannyasa Vidha.[137] A 6th century CE Chinese translation and other texts consistently note Kapila as an ascetic and the founder of the school, mention Asuri as the inheritor of the teaching and a much later scholar named Pancasikha[138] as the scholar who systematized it and then helped widely disseminate its ideas.[139] Isvarakrsna is identified in these texts as the one who summarized and simplified Samkhya theories of Pancasikha, many centuries later (roughly 4th or 5th century CE), in the form that was then translated into Chinese by Paramartha in the 6th century CE.[137]

Samkhyakarika

[edit]The earliest surviving authoritative text on classical Samkhya philosophy is the Samkhya Karika (c. 200 CE[140] or 350–450 CE[132]) of Īśvarakṛṣṇa.[132] There were probably other texts in early centuries CE, however none of them are available today.[141] Iśvarakṛṣṇa in his Kārikā describes a succession of the disciples from Kapila, through Āsuri and Pañcaśikha to himself. The text also refers to an earlier work of Samkhya philosophy called Ṣaṣṭitantra (science of sixty topics) which is now lost.[132] The text was imported and translated into Chinese about the middle of the 6th century CE.[142] The records of Al Biruni, the Persian visitor to India in the early 11th century, suggests Samkhyakarika was an established and definitive text in India in his times.[143]

Samkhyakarika includes distilled statements on epistemology, metaphysics and soteriology of the Samkhya school. For example, the fourth to sixth verses of the text states it epistemic premises,[144]

Perception, inference and right affirmation are admitted to be threefold proof; for they (are by all acknowledged, and) comprise every mode of demonstration. It is from proof that belief of that which is to be proven results.

Perception is ascertainment of particular objects. Inference, which is of three sorts, premises an argument, and deduces that which is argued by it. Right affirmation is true revelation (Apta vacana and Sruti, testimony of reliable source and the Vedas).

Sensible objects become known by perception; but it is by inference or reasoning that acquaintance with things transcending the senses is obtained. A truth which is neither to be directly perceived, nor to be inferred from reasoning, is deduced from Apta vacana and Sruti.

— Samkhya Karika Verse 4–6, [144]

The most popular commentary on the Samkhyakarika was the Gauḍapāda Bhāṣya attributed to Gauḍapāda, the proponent of Advaita Vedanta school of philosophy. Other important commentaries on the karika were Yuktidīpīka (c. 6th century CE) and Vācaspati’s Sāṁkhyatattvakaumudī (c. 10th century CE).[145]

Yuktidipika

[edit]Between 1938 and 1967, two previously unknown manuscript editions of Yuktidipika (ca. 600–700 CE) were discovered and published.[146] Yuktidipika is an ancient review by an unknown author and has emerged as the most important commentary on the Samkhyakarika, itself an ancient key text of the Samkhya school.[147][88] This commentary as well as the reconstruction of pre-karika epistemology and Samkhya emanation text (containing cosmology-ontology) from the earliest Puranas and Mokshadharma suggest that Samkhya as a technical philosophical system existed from about the last century BCE to the early centuries of the Common Era. Yuktidipika suggests that many more ancient scholars contributed to the origins of Samkhya in ancient India than were previously known and that Samkhya was a polemical philosophical system. However, almost nothing is preserved from the centuries when these ancient Samkhya scholars lived.[146]

Samkhya revival

[edit]The 13th century text Sarvadarsanasangraha contains 16 chapters, each devoted to a separate school of Indian philosophy. The 13th chapter in this book contains a description of the Samkhya philosophy.[148]

The Sāṁkhyapravacana Sūtra (c. 14th century CE) renewed interest in Samkhya in the medieval era. It is considered the second most important work of Samkhya after the karika.[149] Commentaries on this text were written by Anirruddha (Sāṁkhyasūtravṛtti, c. 15th century CE), Vijñānabhikṣu (Sāṁkhyapravacanabhāṣya, c. 16th century CE), Mahādeva (vṛttisāra, c. 17th century CE) and Nāgeśa (Laghusāṁkhyasūtravṛtti).[150] In his introduction, the commentator Vijnana Bhiksu stated that only a sixteenth part of the original Samkhya Sastra remained, and that the rest had been lost to time.[151] While the commentary itself is no doubt medieval, the age of the underlying sutras is unknown and perhaps much older. According to Surendranath Dasgupta, scholar of Indian philosophy, Charaka Samhita, an ancient Indian medical treatise, also contains thoughts from an early Samkhya school.[152]

Views on God

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Atheism |

|---|

|

Burley and Gopal suggest distinguishing between theistic and non-theistic streams of Samkhya traditions as "seśvara ('with lord')" and "nirīśvara ('without lord')" respectively.[139][153] Burley suggests that the Svetasvatara Upanishad is a paradigmatic example of seśvara Samkhya whereas the Samkhyakarika is a paradigmatic example of nirīśvara Samkhya.[139]

Daniel Sheridan suggests that a theistic form of Samkhya, older than the classical system, is found in the Upanishads. This form is also present in the Vaisnava Puranas.[154]

The oldest commentary on the Samkhyakarika, the Yuktidīpikā, asserts the existence of God, stating: "We do not completely reject the particular power of the Lord, since he assumes a majestic body and so forth. Our intended meaning is just that there is no being who is different from prakrti and purusa and who is the instigator of these two, as you claim. Therefore, your view is refuted. The conjunction between prakrti and purusa is not instigated by another being."[29]

Chandradhar Sharma in 1960 affirmed that Samkhya in the beginning was based on the theistic absolute of Upanishads, but later on, under the influence of Jaina and Buddhist thought, it rejected theistic monism and was content with spiritualistic pluralism and atheistic realism. This also explains why some of the later Samkhya commentators, e.g. Vijnanabhiksu in the sixteenth century, tried to revive the earlier theism in Samkhya.[155]: 137

A key difference between the Samkhya and Yoga schools, state scholars,[156][157] is that the Yoga school accepts a 'personal, yet essentially inactive, deity' or 'personal god'.[158] However, Radhanath Phukan, in the introduction to his translation of the Samkhya Karika of Isvarakrsna has argued that commentators who see the unmanifested as non-conscious make the mistake of regarding Samkhya as atheistic, though Samkhya is equally as theistic as Yoga.[159] A majority of modern academic scholars are of view that the concept of Ishvara was incorporated into the nirishvara (atheistic) Samkhya viewpoint only after it became associated with the Yoga, the Pasupata and the Bhagavata schools of philosophy.[citation needed] Others have traced the concept of the emergent Isvara accepted by Samkhya to as far back as the Rig Veda, where it was called Hiranyagarbha (the golden germ, golden egg).[160][161] This theistic Samkhya philosophy is described in the Mahabharata, the Puranas and the Bhagavad Gita.[162]

Although the Samkhya school considers the Vedas a reliable source of knowledge, samkhya accepts the notion of higher selves or perfected beings but rejects the notion of God, according to Paul Deussen and other scholars,[163][156] although other scholars believe that Samkhya is as much theistic as the Yoga school.[159][29]

According to Rajadhyaksha, classical Samkhya argues against the existence of God on metaphysical grounds. Samkhya theorists argue that an unchanging God cannot be the source of an ever-changing world and that God was only a necessary metaphysical assumption demanded by circumstances.[164]

A medieval commentary of Samkhyakarika such as Sāṁkhyapravacana Sūtra in verse no. 1.92 directly states that existence of "Ishvara (God) is unproved". Hence there is no philosophical place for a creationist God in this system. It is also argued by commentators of this text that the existence of Ishvara cannot be proved and hence cannot be admitted to exist.[165] However, later in the text, the commentator Vijnana Bhiksu clarified that the subject of dispute between the Samkhyas and others was the existence of an eternal Isvara. Samkhya did accept the concept of an emergent Isvara previously absorbed into Prakṛti.[166]

Arguments against Ishvara's existence

[edit]According to Sinha, the following arguments were given by Samkhya philosophers against the idea of an eternal, self-caused, creator God:[165]

- If the existence of karma is assumed, the proposition of God as a moral governor of the universe is unnecessary. For, if God enforces the consequences of actions then he can do so without karma. If however, he is assumed to be within the law of karma, then karma itself would be the giver of consequences and there would be no need of a God.

- Even if karma is denied, God still cannot be the enforcer of consequences. Because the motives of an enforcer God would be either egoistic or altruistic. Now, God's motives cannot be assumed to be altruistic because an altruistic God would not create a world so full of suffering. If his motives are assumed to be egoistic, then God must be thought to have desire, as agency or authority cannot be established in the absence of desire. However, assuming that God has desire would contradict God's eternal freedom which necessitates no compulsion in actions. Moreover, desire, according to Samkhya, is an attribute of prakṛti and cannot be thought to grow in God. The testimony of the Vedas, according to Samkhya, also confirms this notion.

- Despite arguments to the contrary, if God is still assumed to contain unfulfilled desires, this would cause him to suffer pain and other similar human experiences. Such a worldly God would be no better than Samkhya's notion of higher self.

- Furthermore, there is no proof of the existence of God. He is not the object of perception, there exists no general proposition that can prove him by inference and the testimony of the Vedas speak of prakṛti as the origin of the world, not God.

Therefore, Samkhya maintained that the various cosmological, ontological and teleological arguments could not prove God.

Influence on other schools

[edit]Vaisheshika and Nyaya

[edit]The Vaisheshika atomism, Nyaya epistemology may all have roots in the early Samkhya school of thought; but these schools likely developed in parallel with an evolving Samkhya tradition, as sibling intellectual movements.[167]

Yoga

[edit]

The Yoga school derives its ontology and epistemology from Samkhya and adds to it the concept of Isvara.[168] However, scholarly opinion on the actual relationship between Yoga and Samkhya is divided. While Jakob Wilhelm Hauer and Georg Feuerstein believe that Yoga was a tradition common to many Indian schools and its association with Samkhya was artificially foisted upon it by commentators such as Vyasa. Johannes Bronkhorst and Eric Frauwallner think that Yoga never had a philosophical system separate from Samkhya. Bronkhorst further adds that the first mention of Yoga as a separate school of thought is no earlier than Śankara's (c. 788–820 CE)[169] Brahmasūtrabhaśya.[170]

Tantra

[edit]The dualistic metaphysics of various Tantric traditions illustrates the strong influence of Samkhya on Tantra. Shaiva Siddhanta was identical to Samkhya in its philosophical approach, barring the addition of a transcendent theistic reality.[171] Knut A. Jacobsen, Professor of Religious Studies, notes the influence of Samkhya on Srivaishnavism. According to him, this Tantric system borrows the abstract dualism of Samkhya and modifies it into a personified male–female dualism of Vishnu and Sri Lakshmi.[172] Dasgupta speculates that the Tantric image of a wild Kali standing on a slumbering Shiva was inspired from the Samkhyan conception of prakṛti as a dynamic agent and Purusha as a passive witness. However, Samkhya and Tantra differed in their view on liberation. While Tantra sought to unite the male and female ontological realities, Samkhya held a withdrawal of consciousness from matter as the ultimate goal.[173]

According to Bagchi, the Samkhya Karika (in karika 70) identifies Sāmkhya as a Tantra,[174] and its philosophy was one of the main influences both on the rise of the Tantras as a body of literature, as well as Tantra sadhana.[175]

Advaita Vedanta

[edit]The Advaita Vedanta philosopher Adi Shankara called Samkhya as the 'principal opponent' (pradhana-malla) of Vedanta. He criticized the Samkhya view that the cause of the universe is the unintelligent Prakṛti (Pradhan). According to Shankara, the Intelligent Brahman only can be such a cause.[155]: 242–244 Although ancient Samkhya philosophers claimed Vedic authority for their views,[176] Shankara considered dualism in the Samkhyakarika to be inconsistent with the Vedas.[177]

See also

[edit]- Advaita Vedanta of Adi Shankara, a non-dualist strand within Hinduism

- Darshanas

- Khyativada

- Ratha Kalpana

- Subtle body

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Zimmer: "[Jainism] does not derive from Brahman-Aryan sources, but reflects the cosmology and anthropology of a much older pre-Aryan upper class of northeastern India - being rooted in the same subsoil of archaic metaphysical speculation as Yoga, Sankhya, and Buddhism, the other non-Vedic Indian systems."[92]

- ^ With the publication of previously unknown editions of Yuktidipika about mid 20th century, Larson[80] has suggested what he calls as "a tempting hypothesis", but uncertain, that Samkhya tradition may be the oldest of the Indian technical philosophical schools (Nyaya, Vaisheshika).[80]

- ^ Early speculations such as Rg Veda 1.164, 10.90 and 10.129; see Larson (2014, p. 5).

- ^ a b Older authors have noted the references to samkhya in the Upanishads. Surendranath Dasgupta stated in 1922 that Samkhya can be traced to Upanishads such as Katha Upanishad, Shvetashvatara Upanishad and Maitrayaniya Upanishad, and that the 'extant Samkhya' is a system that unites the doctrine of permanence of the Upanishads with the doctrine of momentariness of Buddhism and the doctrine of relativism of Jainism.[83] Arthur Keith in 1925 said, '[That] Samkhya owes its origin to the Vedic-Upanisadic-epic heritage is quite evident',[84] and 'Samkhya is most naturally derived out of the speculations in the Vedas, Brahmanas and the Upanishads'.[85] Johnston in 1937 analyzed then available Hindu and Buddhist texts for the origins of Samkhya and wrote, '[T]he origin lay in the analysis of the individual undertaken in the Brahmanas and earliest Upanishads, at first with a view to assuring the efficacy of the sacrificial rites and later in order to discover the meaning of salvation in the religious sense and the methods of attaining it. Here – in Kaushitaki Upanishad and Chandogya Upanishad – the germs are to be found (of) two of the main ideas of classical Samkhya'.[86]

References

[edit]- ^ Knut A. Jacobsen, Theory and Practice of Yoga, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120832329, pages 100–101.

- ^ "Samkhya", American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fifth Edition (2011), Quote: "Samkhya is a system of Hindu philosophy based on a dualism involving the ultimate principles of soul and matter."

- ^ "Samkhya", Webster's College Dictionary (2010), Random House, ISBN 978-0375407413, Quote: "Samkhya is a system of Hindu philosophy stressing the reality and duality of spirit and matter."

- ^ a b c Lusthaus 2018.

- ^ a b c Sharma 1997, pp. 155–7.

- ^ a b Chapple 2008, p. 21.

- ^ a b Osto 2018, p. 203.

- ^ a b Osto 2018, p. 204–205.

- ^ Gerald James Larson (2011), Classical Sāṃkhya: An Interpretation of Its History and Meaning, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120805033, pages 154–206.

- ^ a b c Osto 2018, p. 204.

- ^ a b Haney 2002, p. 42.

- ^ a b c d Osto 2018, p. 205.

- ^ a b Larson 1998, p. 11.

- ^ a b "Samkhya". Encyclopedia Britannica. 5 May 2015 [1998-07-20]. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ a b Gerald James Larson (2011), Classical Sāṃkhya: An Interpretation of Its History and Meaning, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120805033, pages 36–47.

- ^ a b c d Larson 1998, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e * Eliott Deutsche (2000), in Philosophy of Religion: Indian Philosophy, Volume 4 (Editor: Roy Perrett), Routledge, ISBN 978-0815336112, pages 245–248.

- John A. Grimes, A Concise Dictionary of Indian Philosophy: Sanskrit Terms Defined in English, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791430675, page 238.

- ^ John A. Grimes, A Concise Dictionary of Indian Philosophy: Sanskrit Terms Defined in English, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791430675, page 238.

- ^ Mikel Burley (2012), Classical Samkhya and Yoga – An Indian Metaphysics of Experience, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415648875, pages 43–46.

- ^ David Kalupahana (1995), Ethics in Early Buddhism, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0824817022, page 8, Quote: The rational argument is identified with the method of Samkhya, a rationalist school, upholding the view that "nothing comes out of nothing" or that "being cannot be non-being."

- ^ a b Zimmer 1951, p. 217, 314.

- ^ a b c d Larson 2014, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e Larson 2014, p. 5.

- ^ Larson 2014, p. 4–5.

- ^ Larson 2014, p. 9–11.

- ^ Michaels 2004, p. 264.

- ^ Sen Gupta 1986, p. 6.

- ^ Radhakrishnan & Moore 1957, p. 89.

- ^ a b c Andrew J. Nicholson (2013), Unifying Hinduism: Philosophy and Identity in Indian Intellectual History, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0231149877, chapter 4, page 77.

- ^ a b Roy Perrett, Indian Ethics: Classical Traditions and Contemporary Challenges, Volume 1 (Editor: P Bilimoria et al.), Ashgate, ISBN 978-0754633013, pages 149–158.

- ^ Larson 2014, p. xi.

- ^ saMkhya Monier-Williams' Sanskrit-English Dictionary, Cologne Digital Sanskrit Lexicon, Germany

- ^ Mikel Burley (2012), Classical Samkhya and Yoga - An Indian Metaphysics of Experience, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415648875, pages 47-48

- ^ a b Apte 1957, p. 1664

- ^ Bhattacharyya 1975, pp. 419–20

- ^ Larson 1998, pp. 4, 38, 288

- ^ Sharma 1997, pp. 149–168.

- ^ Haney 2002, p. 17.

- ^ Isaac & Dangwal 1997, p. 339.

- ^ a b Sharma 1997, pp. 149–168

- ^ Nicholson, Andrew J. (1 August 2007). "Reconciling dualism and non-dualism: three arguments in Vijñānabhikṣu's Bhedābheda Vedānta". Journal of Indian Philosophy. 35 (4): 383. doi:10.1007/s10781-007-9016-6. ISSN 1573-0395.

- ^ Hiriyanna 1993, pp. 270–272.

- ^ Chattopadhyaya 1986, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Osto 2018, p. 204-205.

- ^ James G. Lochtefeld, Guna, in The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A-M, Vol. 1, Rosen Publishing, ISBN 9780823931798, page 265

- ^ T Bernard (1999), Hindu Philosophy, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1373-1, pages 74–76

- ^ a b Isaac & Dangwal 1997, p. 342

- ^ Leaman 2000, p. 68

- ^ Sinha 2012, p. App. VI,1

- ^ Gerald James Larson (2011), Classical Sāṃkhya: An Interpretation of Its History and Meaning, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120805033, page 273

- ^ Original Sanskrit: Samkhya karika Compiled and indexed by Ferenc Ruzsa (2015), Sanskrit Documents Archives;

Samkhya karika by Iswara Krishna, Henry Colebrooke (Translator), Oxford University Press, page 169 - ^ a b "Sāṁkhya thought in the Brahmanical systems of Indian philosophy | WorldCat.org". www.worldcat.org. Retrieved 16 February 2023.

- ^ Larson 1998, p. 13

- ^ Colebrooke, Henry Thomas (1887). The Sānkhya kārika : or, Memorial verses on the Sānkhya philosophy. Chatterjea. p. 178. OCLC 61647186.

- ^ Dasti, Matthew R., Bryant, Edwin F. (2014). Free will, agency, and selfhood in Indian philosophy. Oup USA. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-19-992275-8. OCLC 852227561.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b MM Kamal (1998), The Epistemology of the Carvaka Philosophy, Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies, 46(2): 13-16

- ^ B Matilal (1992), Perception: An Essay in Indian Theories of Knowledge, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0198239765

- ^ a b Karl Potter (1977), "Meaning and Truth," in Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies, Volume 2, Princeton University Press, Reprinted in 1995 by Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0309-4, pages 160-168

- ^ Karl Potter (1977), Meaning and Truth, in Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies, Volume 2, Princeton University Press, Reprinted in 1995 by Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0309-4, pages 168-169

- ^ Karl Potter (1977), "Meaning and Truth," in Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies, Volume 2, Princeton University Press, Reprinted in 1995 by Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0309-4, pages 170-172

- ^ W Halbfass (1991), Tradition and Reflection, State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-7914-0362-9, page 26-27

- ^ Carvaka school is the exception

- ^ a b James Lochtefeld, "Anumana" in The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 1: A-M, Rosen Publishing. ISBN 0-8239-2287-1, page 46-47

- ^ Karl Potter (2002), Presuppositions of India's Philosophies, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0779-0

- ^ Monier Williams (1893), Indian Wisdom - Religious, Philosophical and Ethical Doctrines of the Hindus, Luzac & Co, London, page 61

- ^ DPS Bhawuk (2011), Spirituality and Indian Psychology (Editor: Anthony J. Marsella), Springer, ISBN 978-1-4419-8109-7, page 172

- ^ a b c M. Hiriyanna (2000), The Essentials of Indian Philosophy, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120813304, page 43

- ^ P. Billimoria (1988), Śabdapramāṇa: Word and Knowledge, Studies of Classical India, Volume 10, Springer, ISBN 978-94-010-7810-8, pages 1-30

- ^ Larson 1998, p. 10

- ^ a b c Larson 1998, p. 75.

- ^ a b c d e Larson 2014, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d Larson 2014, p. 9.

- ^ a b c Larson 2014, p. 4-5.

- ^ a b c Larson 2014, p. 6.

- ^ a b Larson 2014, p. 6-7.

- ^ Larson 2014, p. 7.

- ^ Larson 2014, p. 3, 9.

- ^ Larson 2014, p. 14-18.

- ^ Larson 2014, p. 3-11.

- ^ a b Larson 2014, p. 10-11.

- ^ Max Muller, Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, Oxford University Press, page 85

- ^ Radhakrishnan 1953, p. 163

- ^ Surendranath Dasgupta (1975). A History of Indian Philosophy. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 212. ISBN 978-81-208-0412-8.

- ^ Gerald Larson (2011), Classical Sāṃkhya: An Interpretation of Its History and Meaning, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120805033, pages 31-32

- ^ Gerald Larson (2011), Classical Sāṃkhya: An Interpretation of Its History and Meaning, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120805033, page 29

- ^ EH Johnston (1937), Early Samkhya: An Essay on its Historical Development according to the Texts, The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Volume XV, pages 80-81

- ^ a b c d Burley 2006, pp. 15–16.

- ^ a b Larson 2014, p. 3-4.

- ^ Larson 1998, pp. 82–90.

- ^ Richard Garbe (1892). Aniruddha's Commentary and the original parts of Vedantin Mahadeva's commentary on the Sankhya Sutras Translated, with an introduction to the age and origin of the Sankhya system. pp. xx–xxi.

- ^ R.N. Dandekar (1968). 'God in Indian Philosophy' in Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. p. 444. JSTOR 41694270.

- ^ Zimmer 1951, p. 217.

- ^ Warder 2009, p. 63.

- ^ Warder 2009, pp. 63–65.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ruzsa 2006.

- ^ Mikel Burley (2012), Classical Samkhya and Yoga - An Indian Metaphysics of Experience, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415648875, pages 37-38

- ^ a b c Mikel Burley (2012), Classical Samkhya and Yoga - An Indian Metaphysics of Experience, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415648875, pages 37-39

- ^ Singh 2008, p. 185.

- ^

- Original Sanskrit: Rigveda 10.129 Wikisource;

- Translation 1: Max Muller (1859). A History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature. Williams and Norgate, London. pp. 559–565.

- Translation 2: Kenneth Kramer (1986). World Scriptures: An Introduction to Comparative Religions. Paulist Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-8091-2781-4.

- Translation 3: David Christian (2011). Maps of Time: An Introduction to Big History. University of California Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-0-520-95067-2.

- ^ "Although, no doubt, of high antiquity, the hymn appears to be less of a primary than of a secondary origin, being in fact a controversial composition levelled especially against the Sāṃkhya theory." Ravi Prakash Arya and K. L. Joshi. Ṛgveda Saṃhitā: Sanskrit Text, English Translation, Notes & Index of Verses. (Parimal Publications: Delhi, 2001) ISBN 81-7110-138-7

{{isbn}}: ignored ISBN errors (link) (Set of four volumes). Parimal Sanskrit Series No. 45; 2003 reprint: 81-7020-070-9, Volume 4, p. 519. - ^ Larson 1998, p. 79.

- ^ Larson, Bhattacharya & Potter 2014, p. 5-6, 109-110, 180.

- ^ a b Larson, Bhattacharya & Potter 2014, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Stephanie Jamison and Joel Brereton (2014), The Rigveda, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199370184, pages 349-359

- ^ William Mahony (1997), The Artful Universe: An Introduction to the Vedic Religious Imagination, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791435809, pages 245-250

- ^ a b

- Original Sanskrit: [Rigveda Sukta] (in Sanskrit) – via Wikisource.

- Translation 1: The Rigveda. Translated by Jamison, Stephanie W.; Brereton, Joel P. Oxford University Press. 2014 [c. 1500–1000 BCE]. pp. 349–359. ISBN 978-0-19-937018-4.

- Translation 2: . Translated by Griffith, Ralph T. H. 1896 [c. 1500–1000 BCE] – via Wikisource.

- ^ Stephanie Jamison and Joel Brereton (2014), The Rigveda, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199370184, pages 349-355

- ^ Rigveda 1.164.6 Ralph Griffith (Translator), Wikisource

- ^ Larson, Bhattacharya & Potter 2014, p. 295-296.

- ^ Ram Nidumolu (2013), Two Birds in a Tree, Berrett-Koehler Publishers, ISBN 978-1609945770, page 189

- ^ Stephanie Jamison and Joel Brereton (2014), The Rigveda, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199370184, page 352

- ^ Anna-Teresa Tymieniecka (2005), Logos of Phenomenology and Phenomenology of The Logos, Springer, ISBN 978-1402037061, pages 186-193 with footnote 7

- ^ Larson 1998, pp. 59, 79–81.

- ^ a b Larson 1998, p. 82.

- ^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 288-289

- ^ Michele Marie Desmarais (2008), Changing minds: Mind, Consciousness and Identity in Patanjali's Yoga Sutra, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120833364, page 25

- ^ Larson 1998, pp. 82–84.

- ^ Larson 1998, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Larson 1998, pp. 89.

- ^ Larson 1998, pp. 88–90.

- ^ a b c d Larson 1998, pp. 91–93

- ^ Burley 2006, pp. 16.

- ^ Fowler 2012, p. 39

- ^ GJ Larson, RS Bhattacharya and K Potter (2014), The Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies, Volume 4, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691604411, pages 2-8, 114-116

- ^ GJ Larson, RS Bhattacharya and K Potter (2014), The Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies, Volume 4, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691604411, pages 6-7, 74-88, 113-122, 315-318

- ^ a b Burley 2006, pp. 15–18

- ^ GJ Larson, RS Bhattacharya and K Potter (2014), The Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies, Volume 4, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691604411, pages 6–7

- ^ a b Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, pages 273, 288–289, 298–299

- ^ Larson 1998, p. 96.

- ^ Fowler 2012, p. 34

- ^ Fowler 2012, p. 37

- ^ a b c d King 1999, p. 63

- ^ a b Larson, Bhattacharya & Potter 2014, p. 3-11.

- ^ Mircea Eliade et al. (2009), Yoga: Immortality and Freedom, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691142036, pages 392–393

- ^ Willemen, Charles, transl. (2009), Buddhacarita: In Praise of Buddha's Acts, Berkeley, Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research, p. XIII.

- ^ Sharma 1997, p. 149

- ^ a b c Gerald James Larson and Ram Shankar Bhattacharya, The Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies, Volume 4, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691604411, pages 107-109

- ^ "Samkhya: Part Two: Samkhya Teachers". sreenivasarao's blogs. 3 October 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Bilimoria, Purushottama; Mohanty, J. N.; Rayner, Amy; Powers, John; Phillips, Stephen; King, Richard; Chapple, Christopher Key (22 November 2017). Bilimoria, Purushottama (ed.). History of Indian Philosophy: Routledge history of world philosophies (1 ed.). 1 [edition]. | New York : Routledge, 2017. |: Routledge. pp. 131–132. doi:10.4324/9781315666792. ISBN 978-1-315-66679-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Bagchi 1989.

- ^ Larson 1998, p. 4

- ^ Larson 1998, pp. 147–149

- ^ Larson 1998, pp. 150–151

- ^ a b Samkhyakarika of Iswara Krishna Henry Colebrook (Translator), Oxford University Press, pages 18-27;

Sanskrit Original Samkhya karika with Gaudapada Bhasya, Ashubodh Vidyabushanam, Kozhikode, Kerala - ^ King 1999, p. 64

- ^ a b Larson 2014, p. 9-11.

- ^ Larson, Bhattacharya & Potter 2014, p. 3-4.

- ^ Cowell & Gough 1882, p. 22.

- ^ Eliade, Trask & White 2009, p. 370

- ^ Radhakrishnan 1923, pp. 253–56

- ^ Sinha, Nandalal (1915). The Samkhya Philosophy (2003 ed.). New Delhi: Mushiram Manoharlal. p. 3. ISBN 81-215-1097-X.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Dasgupta 1922, pp. 213–7

- ^ Gopal, Lallanji (2000). Retrieving Sāṁkhya history: an ascent from dawn to meridian. Contemporary researches in Hindu philosophy and religion. New Delhi: D.K. Printworld. pp. 301–317. ISBN 978-81-246-0143-3.

- ^ Gupta, Gopal K. (2020). Māyā in the Bhāgavata Purāna: human suffering and divine play. Oxford theology and religion monographs. Oxford New York (N.Y.): Oxford university press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-19-885699-3.

- ^ a b Chandradhar Sharma (2000). A Critical Survey of Indian Philosophy. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0365-7.

- ^ a b Lloyd Pflueger, Person Purity and Power in Yogasutra, in Theory and Practice of Yoga (Editor: Knut Jacobsen), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120832329, pages 38-39

- ^ Mikel Burley (2012), Classical Samkhya and Yoga - An Indian Metaphysics of Experience, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415648875, page 39, 41

- ^ Kovoor T. Behanan (2002), Yoga: Its Scientific Basis, Dover, ISBN 978-0486417929, pages 56-58

- ^ a b Radhanath Phukan, Samkhya Karika of Isvarakrsna (Calcutta: Firma K. L. Mukhopadhyay, 1960), pp.36-40

- ^ Larson, Gerald (1969). Classical Samkhya (2005 ed.). New Delhi: Motilal Banrsidass. p. 82. ISBN 81-208-0503-8.

- ^ Aranya, Hariharananda (1963). Yoga Philosophy of Patanjali With Bhasvati. Calcutta: Calcutta University Press. pp. 676–685. ISBN 81-87594-00-4.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Karmarkar 1962, pp. 90–1

- ^ Mike Burley (2012), Classical Samkhya and Yoga - An Indian Metaphysics of Experience, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415648875, page 39

- ^ Rajadhyaksha 1959, p. 95

- ^ a b Sinha 2012, pp. xiii–iv

- ^ Sinha, Nandalal (1915). The Samkhya Philosophy (2003 ed.). New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 332. ISBN 81-215-1097-X.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Larson, Bhattacharya & Potter 2014, p. 10-11.

- ^ Larson 2008, p. 33

- ^ Isayeva 1993, p. 84

- ^ Larson 2008, pp. 30–32

- ^ Flood 2006, p. 69

- ^ Jacobsen 2008, pp. 129–130

- ^ Kripal 1998, pp. 148–149

- ^ Bagchi 1989, p. 6

- ^ Bagchi 1989, p. 10

- ^ Gerald Larson (2011), Classical Sāṃkhya: An Interpretation of Its History and Meaning, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120805033, page 213

- ^ Gerald Larson (2011), Classical Sāṃkhya: An Interpretation of Its History and Meaning, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120805033, pages 67-70

Sources

[edit]- Apte, Vaman Shivaram (1957). The Practical Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Poona: Prasad Prakashan.

- Bagchi, P.C. (1989), Evolution of the Tantras, Studies on the Tantras, Kolkata: Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture, ISBN 81-85843-36-8

- Bhattacharyya, Haridas, ed. (1975). The Cultural Heritage of India: Vol III: The Philosophies. Calcutta: The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture.

- Burley, Mikel (2006), Classical Samkhya And Yoga: The Metaphysics Of Experience, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0-415-39448-2

- Chapple, Christopher Key (2008), Yoga and the Luminous: Patañjali's Spiritual Path to, SUNY Press

- Chattopadhyaya, Debiprasad (1986), Indian Philosophy: A Popular Introduction, New Delhi: People's Publishing House, ISBN 81-7007-023-6

- Cowell, E. B.; Gough, A. E. (1882), The Sarva-Darsana-Samgraha or Review of the Different Systems of Hindu Philosophy: Trubner's Oriental Series, vol. 4, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0-415-24517-3

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Dasgupta, Surendranath (1922), A history of Indian philosophy, Volume 1, New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publ, ISBN 978-81-208-0412-8

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Eliade, Mircea; Trask, Willard Ropes; White, David Gordon (2009), Yoga: Immortality and Freedom, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-14203-6

- Flood, Gavin (2006), The Tantric Body: The Secret Tradition of Hindu Religion, I.B.Tauris, ISBN 978-1-84511-011-6

- Fowler, Jeaneane D (2012), The Bhagavad Gita: A Text and Commentary for Students, Eastbourne: Sussex Academy Press, ISBN 978-1-84519-520-5

- Haney, William S. (2002), Culture and Consciousness: Literature Regained, New Jersey: Bucknell University Press, ISBN 1611481724

- Hiriyanna, M. (1993), Outlines of Indian Philosophy, New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publ, ISBN 81-208-1099-6

- Isaac, J. R.; Dangwal, Ritu (1997), Proceedings. International conference on cognitive systems, New Delhi: Allied Publishers Ltd, ISBN 81-7023-746-7

- Isayeva, N. V. (1993), Shankara and Indian Philosophy, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-1281-7

- Jacobsen, Knut A. (2008), Theory and Practice of Yoga : 'Essays in Honour of Gerald James Larson, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-3232-9

- Karmarkar, A.P. (1962), Religion and Philosophy of Epics in S. Radhakrishnan ed. The Cultural Heritage of India, Vol.II, Calcutta: The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture, ISBN 81-85843-03-1

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - King, Richard (1999), Indian Philosophy: An Introduction to Hindu and Buddhist Thought, Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 978-0-7486-0954-3

- Kripal, Jeffrey J. (1998), Kali's Child: The Mystical and the Erotic in the Life and Teachings of Ramakrishna, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-45377-4

- Larson, Gerald James (1998), Classical Sāṃkhya: An Interpretation of Its History and Meaning, London: Motilal Banarasidass, ISBN 81-208-0503-8 [first edition, 1968; second revised edition, 1979]

- Larson, Gerald James (2008), The Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies: Yoga: India's philosophy of meditation, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-3349-4

- Larson, G.J. (2014), "Introduction to the Philosophy of Samkhya", in Larson, G.J.; Bhattacharya, R.S. (eds.), The Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies, Volume 4, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691604411

- Larson, G.J.; Bhattacharya, R.S.; Potter, K. (2014), The Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies, Volume 4, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691604411

- Leaman, Oliver (2000), Eastern Philosophy: Key Readings, New Delhi: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-17357-4

- Lusthaus, Dan (2018), Samkhya, acmuller.net, Resources for East Asian Language and Thought, Musashino University

- Michaels, Axel (2004), Hinduism: Past and Present, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-08953-1

- Osto, Douglas (January 2018), "No-Self in Sāṃkhya: A Comparative Look at Classical Sāṃkhya and Theravāda Buddhism", Philosophy East and West, 68 (1): 201–222, doi:10.1353/pew.2018.0010, S2CID 171859396

- Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli; Moore, C. A. (1957), A Source Book in Indian Philosophy, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-01958-4

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli (1953), The principal Upaniṣads, Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books, ISBN 978-1-57392-548-8

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli (1923), Indian Philosophy, Vol. II, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-563820-4

{{citation}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Rajadhyaksha, N. D. (1959), The six systems of Indian philosophy, Bombay (Mumbai), OCLC 11323515

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Ruzsa, Ferenc (2006), Sāṅkhya (Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

- Sen Gupta, Anima (1986), The Evolution of the Samkhya School of Thought, New Delhi: South Asia Books, ISBN 81-215-0019-2

- Sharma, C. (1997), A Critical Survey of Indian Philosophy, New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publ, ISBN 81-208-0365-5

- Singh, Upinder (2008), A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Pearson Education India, ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0

- Sinha, Nandlal (2012), The Samkhya Philosophy, New Delhi: Hard Press, ISBN 978-1407698915

- Warder, Anthony Kennedy (2009), A Course in Indian Philosophy, Motilal Banarsidass, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., ISBN 978-8120812444

- Zimmer, Heinrich (1951), Philosophies of India (reprint 1989), Princeton University Press

Further reading

[edit]- Mikel Burley (2007). Classical Samkhya and Yoga: An Indian Metaphysics of Experience. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-15978-9.

- Jeaneane D. Fowler (2002). "Chapter Six: Samkhya". Perspectives of Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Hinduism. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-898723-93-6.

- Michel Hulin (1978). Sāṃkhya Literature. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3447018999.

- Gerald James Larson (2001). Classical Sāṃkhya: An Interpretation of Its History and Meaning. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0503-3. [first edition, 1968; second revised edition, 1979]

- Max Müller (1919). Six Systems of Indian Philosophy. Longmans Green And Co.

- Jens Lauschke (2023). SAMKHYA YOGA: An Interpretation of Iswara Krishna's Samkhya Karika. Taxila Publications. ISBN 978-3948459604.

External links

[edit]- Ferenc Ruzsa, Fieser, James; Dowden, Bradley (eds.). "Samkhya". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. ISSN 2161-0002. OCLC 37741658.

- Dan Lusthaus, Samkhya

- Samkhya and Yoga: An Introduction, Russell Kirkland, University of Georgia

- PDF file of Ishwarkrishna's Sankhyakarika, in English

- Bibliography of scholarly works: see [S] for Samkhya Archived 13 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine by Karl Potter, University of Washington

- Lectures on Samkhya, The Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies, Oxford University

Samkhya

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Etymology