Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Croup

View on Wikipedia

| Croup | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Croupy cough, subglottic laryngitis, obstructive laryngitis, laryngotracheobronchitis |

| |

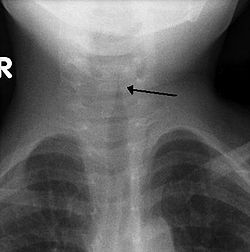

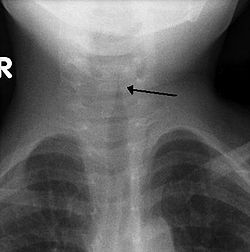

| The steeple sign as seen on an AP neck X-ray of a child with croup | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Pediatrics |

| Symptoms | "Barky" cough, stridor, fever, stuffy nose[2] |

| Duration | Usually 1–2 days but can last up to 7 days[3] |

| Causes | Mostly viral[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Epiglottitis, airway foreign body, bacterial tracheitis[4][5] |

| Prevention | Influenza and diphtheria vaccination[5] |

| Medication | Corticosteroids, epinephrine[4][5] |

| Frequency | 15% of children at some point[4][5] |

| Deaths | Rare[2] |

Croup (/kruːp/ KROOP), also known as croupy cough, is a type of respiratory infection that is usually caused by a virus.[2] The infection leads to swelling inside the trachea, which interferes with normal breathing and produces the classic symptoms of "barking/brassy" cough, inspiratory stridor, and a hoarse voice.[2] Fever and runny nose may also be present.[2] These symptoms may be mild, moderate, or severe.[3] It often starts or is worse at night and normally lasts one to two days.[6][2][3]

Croup can be caused by a number of viruses including parainfluenza and influenza virus.[2] Rarely is it due to a bacterial infection.[5] Croup is typically diagnosed based on signs and symptoms after potentially more severe causes, such as epiglottitis or an airway foreign body, have been ruled out.[4] Further investigations, such as blood tests, X-rays and cultures, are usually not needed.[4]

Many cases of croup are preventable by immunization for influenza and diphtheria.[5] Most cases of croup are mild and the patient can be treated at home with supportive care. Croup is usually treated with a single dose of steroids by mouth.[2][7] In more severe cases inhaled epinephrine may also be used.[2][8] Hospitalization is required in one to five percent of cases.[9]

Croup is a relatively common condition that affects about 15% of children at some point.[4] It most commonly occurs between six months and five years of age but may rarely be seen in children as old as fifteen.[3][4][9] It is slightly more common in males than females.[9] It occurs most often in autumn.[9] Before vaccination, croup was frequently caused by diphtheria and was often fatal.[5][10] This cause is now very rare in the Western world due to the success of the diphtheria vaccine.[11]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Croup is characterized by a "barking" cough, stridor, hoarseness, and difficult breathing which usually worsens at night.[2] The "barking" cough is often described as resembling the call of a sea lion.[5] The stridor is worsened by agitation or crying, and if it can be heard at rest, it may indicate critical narrowing of the airways. As croup worsens, stridor may decrease considerably.[2]

Other symptoms include fever, coryza (symptoms typical of the common cold), and indrawing of the chest wall–known as Hoover's sign.[2][12] Drooling or a very sick appearance can indicate other medical conditions, such as epiglottitis or tracheitis.[12]

Causes

[edit]Croup is usually deemed to be due to a viral infection.[2][4] Others use the term more broadly, to include acute laryngotracheitis (laryngitis and tracheitis together), spasmodic croup, laryngeal diphtheria, bacterial tracheitis, laryngotracheobronchitis, and laryngotracheobronchopneumonitis. The first two conditions involve a viral infection and are generally milder with respect to symptomatology; the last four are due to bacterial infection and are usually of greater severity.[5]

Viral

[edit]Viral croup or acute laryngotracheitis is most commonly caused by parainfluenza virus (a member of the paramyxovirus family), primarily types 1 and 2, in 75% of cases.[3] Other viral causes include influenza A and B, measles, adenovirus and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).[5] Spasmodic croup is caused by the same group of viruses as acute laryngotracheitis, but lacks the usual signs of infection (such as fever, sore throat, and increased white blood cell count).[5] Treatment, and response to treatment, are also similar.[3]

Bacteria and cocci

[edit]Croup caused by a bacterial infection is rare.[13] Bacterial croup may be divided into laryngeal diphtheria, bacterial tracheitis, laryngotracheobronchitis, and laryngotracheobronchopneumonitis.[5] Laryngeal diphtheria is due to Corynebacterium diphtheriae while bacterial tracheitis, laryngotracheobronchitis, and laryngotracheobronchopneumonitis are usually due to a primary viral infection with secondary bacterial growth. The most common cocci implicated are Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae, while the most common bacteria are Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis.[5]

Pathophysiology

[edit]The viral infection that causes croup leads to swelling of the larynx, trachea, and large bronchi[4] due to infiltration of white blood cells (especially histiocytes, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils).[5] Swelling produces airway obstruction which, when significant, leads to dramatically increased work of breathing and the characteristic turbulent, noisy airflow known as stridor.[4]

Diagnosis

[edit]Croup is typically diagnosed based on signs and symptoms.[4] The first step is to exclude other obstructive conditions of the upper airway, especially epiglottitis, an airway foreign body, subglottic stenosis, angioedema, retropharyngeal abscess, and bacterial tracheitis.[4][5]

A frontal X-ray of the neck is not routinely performed,[4] but if it is done, it may show a characteristic narrowing of the trachea, called the steeple sign, because of the subglottic stenosis, which resembles a steeple in shape. The steeple sign is suggestive of the diagnosis, but is absent in half of cases.[12]

Other investigations (such as blood tests and viral culture) are discouraged, as they may cause unnecessary agitation and thus worsen the stress on the compromised airway.[4] While viral cultures, obtained via nasopharyngeal aspiration, can be used to confirm the exact cause, these are usually restricted to research settings.[2] Bacterial infection should be considered if a person does not improve with standard treatment, at which point further investigations may be indicated.[5]

Severity

[edit]| Feature | Number of points assigned for this feature | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Chest wall retraction |

None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||

| Stridor | None | With agitation |

At rest | |||

| Cyanosis | None | With agitation |

At rest | |||

| Level of consciousness |

Normal | Disoriented | ||||

| Air entry | Normal | Decreased | Markedly decreased | |||

The most commonly used system for classifying the severity of croup is the Westley score. It is primarily used for research purposes rather than in clinical practice.[5] It is the sum of points assigned for five factors: level of consciousness, cyanosis, stridor, air entry, and retractions.[5] The points given for each factor is listed in the adjacent table, and the final score ranges from 0 to 17.[14]

- A total score of ≤ 2 indicates mild croup. The characteristic barking cough and hoarseness may be present, but there is no stridor at rest.[3]

- A total score of 3–5 is classified as moderate croup. It presents with easily heard stridor, but with few other signs.[3]

- A total score of 6–11 is severe croup. It also presents with obvious stridor, but also features marked chest wall indrawing.[3]

- A total score of ≥ 12 indicates impending respiratory failure. The barking cough and stridor may no longer be prominent at this stage.[3]

85% of children presenting to the emergency department have mild disease; severe croup is rare (<1%).[3]

Prevention

[edit]Croup is contagious during the first few days of the infection.[13] Basic hygiene including hand washing can prevent transmission.[13] There are no vaccines that have been developed to prevent croup,[13] however, many cases of croup have been prevented by immunization for influenza and diphtheria.[5] At one time, croup referred to a diphtherial disease, but with vaccination, diphtheria is now rare in the developed world.[5]

Treatment

[edit]Most children with croup have mild symptoms and supportive care at home is effective.[13] For children with moderate to severe croup, treatment with corticosteroids and nebulized epinephrine may be suggested. Steroids are given routinely, with epinephrine used in severe cases.[4] Children with oxygen saturation less than 92% should receive oxygen,[5] and those with severe croup may be hospitalized for observation.[12] In very rare severe cases of croup that result in respiratory failure, emergency intubation and ventilation may be required.[15] With treatment, less than 0.2% of children require endotracheal intubation.[14] Since croup is usually a viral disease, antibiotics are not used unless secondary bacterial infection is suspected.[2] The use of cough medicines, which usually contain dextromethorphan or guaifenesin, is also discouraged.[2]

Supportive care

[edit]Supportive care for children with croup includes resting and keeping the child hydrated.[13] Infections that are mild are suggested to be treated at home. Croup is contagious so washing hands is important.[13] Children with croup should generally be kept as calm as possible.[4] Over-the-counter medications for pain and fever may be helpful to keep the child comfortable.[13] There is some evidence that cool or warm mist may be helpful. However, the effectiveness of this approach is not clear.[4][5][13] If the child is showing signs of distress while breathing (inspiratory stridor, working hard to breathe, blue (or blue-ish) coloured lips, or decrease in the level of alertness), immediate medical evaluation by a doctor is required.[13]

Steroids

[edit]Corticosteroids, such as dexamethasone and budesonide, have been shown to improve outcomes in children with all severities of croup, however, the benefits may be delayed.[7] Significant relief may be obtained as early as two hours after administration.[7] While effective when given by injection, or by inhalation, giving the medication by mouth is preferred.[4] A single dose is usually all that is required, and is generally considered to be quite safe.[4] Dexamethasone at doses of 0.15, 0.3 and 0.6 mg/kg appear to be all equally effective.[16]

Epinephrine

[edit]Moderate to severe croup (for example, in the case of severe stridor) may be improved temporarily with nebulized epinephrine.[4] While epinephrine typically produces a reduction in croup severity within 10–30 minutes, the benefits are short-lived and last for only about 2 hours.[2][4] If the condition remains improved for 2–4 hours after treatment and no other complications arise, the child is typically discharged from the hospital.[2][4] Epinephrine treatment is associated with potential adverse effects (usually related to the dose of epinephrine) including tachycardia, arrhythmias, and hypertension.[15]

Oxygen

[edit]More severe cases of croup may require treatment with oxygen. If oxygen is needed, "blow-by" administration (holding an oxygen source near the child's face) is recommended, as it causes less agitation than use of a mask.[5]

Other

[edit]While other treatments for croup have been studied, none has sufficient evidence to support its use. There is tentative evidence that breathing heliox (a mixture of helium and oxygen) to decrease the work of breathing is useful in those with severe disease, however, there is uncertainty in the effectiveness and the potential adverse effects and/or side effects are not well known.[15] In cases of possible secondary bacterial infection, the antibiotics vancomycin and cefotaxime are recommended.[5] In severe cases associated with influenza A or B infections, the antiviral neuraminidase inhibitors may be administered.[5]

Prognosis

[edit]Viral croup is usually a self-limiting disease,[2] with half of cases resolving in a day and 80% of cases in two days.[6] It can very rarely result in death from respiratory failure and/or cardiac arrest.[2] Symptoms usually improve within two days, but may last for up to seven days.[3] Other uncommon complications include bacterial tracheitis, pneumonia, and pulmonary edema.[3]

Epidemiology

[edit]Croup affects about 15% of children, and usually presents between the ages of 6 months and 5–6 years.[4][5] It accounts for about 5% of hospital admissions in this population.[3] In rare cases, it may occur in children as young as 3 months and as old as 15 years.[3] Males are affected 50% more frequently than are females, and there is an increased prevalence in autumn.[5]

History

[edit]The word croup comes from the Early Modern English verb croup, meaning "to cry hoarsely." The noun describing the disease originated in southeastern Scotland and became widespread after Edinburgh physician Francis Home published the 1765 treatise An Inquiry into the Nature, Cause, and Cure of the Croup.[17][18]

Diphtheritic croup has been known since the time of Homer's ancient Greece, and it was not until 1826 that viral croup was differentiated from croup due to diphtheria by Bretonneau.[11][19] Viral croup was then called "faux-croup" by the French and often called "false croup" in English,[20][21] as "croup" or "true croup" then most often referred to the disease caused by the diphtheria bacterium.[22][23] False croup has also been known as pseudo croup or spasmodic croup.[24] Croup due to diphtheria has become nearly unknown in affluent countries in modern times due to the advent of effective immunization.[11][25]

One famous fatality of croup was Napoleon's designated heir, Napoléon Charles Bonaparte. His death in 1807 left Napoleon without an heir and contributed to his decision to divorce from his wife, the Empress Josephine de Beauharnais.[26]

Preston Brooks, a pro-slavery, pre-Civil War US congressman from South Carolina died unexpectedly from a violent attack of croup on January 27, 1857, a few weeks before the March 4 start of the new congressional term to which he had been re-elected.[27]

References

[edit]- ^ "Croup". Macmillan. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Rajapaksa S, Starr M (May 2010). "Croup – assessment and management". Aust Fam Physician. 39 (5): 280–2. PMID 20485713.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Johnson D (2009). "Croup". BMJ Clin Evid. 2009. PMC 2907784. PMID 19445760.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Everard ML (February 2009). "Acute bronchiolitis and croup". Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 56 (1): 119–33, x–xi. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2008.10.007. PMID 19135584.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Cherry JD (2008). "Clinical practice. Croup". N. Engl. J. Med. 358 (4): 384–91. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp072022. PMID 18216359.

- ^ a b Thompson M, Vodicka, TA, Blair, PS, Buckley, DI, Heneghan, C, Hay, AD, TARGET Programme, Team (11 December 2013). "Duration of symptoms of respiratory tract infections in children: systematic review". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 347 f7027. doi:10.1136/bmj.f7027. PMC 3898587. PMID 24335668.

- ^ a b c Aregbesola A, Tam CM, Kothari A, Le ML, Ragheb M, Klassen TP (10 January 2023). "Glucocorticoids for croup in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2023 (1) CD001955. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001955.pub5. PMC 9831289. PMID 36626194.

- ^ Bjornson C, Russell K, Vandermeer B, Klassen TP, Johnson DW (10 October 2013). "Nebulized epinephrine for croup in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10 (10) CD006619. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006619.pub3. PMC 11800190. PMID 24114291.

- ^ a b c d Bjornson CL, Johnson DW (15 October 2013). "Croup in children". CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 185 (15): 1317–23. doi:10.1503/cmaj.121645. PMC 3796596. PMID 23939212.

- ^ Steele V (2005). Bleed, blister, and purge : a history of medicine on the American frontier. Missoula, Mont.: Mountain Press. p. 324. ISBN 978-0-87842-505-1.

- ^ a b c Feigin, Ralph D. (2004). Textbook of pediatric infectious diseases. Philadelphia: Saunders. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-7216-9329-3.

- ^ a b c d "Diagnosis and Management of Croup" (PDF). BC Children's Hospital Division of Pediatric Emergency Medicine Clinical Practice Guidelines. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Baiu I, Melendez E (23 April 2019). "Croup". JAMA. 321 (16): 1642. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.2013. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 31012936. S2CID 242149254.

- ^ a b c Klassen TP (December 1999). "Croup. A current perspective". Pediatr. Clin. North Am. 46 (6): 1167–78. doi:10.1016/S0031-3955(05)70180-2. PMID 10629679.

- ^ a b c Moraa I, Sturman N, McGuire TM, van Driel ML (16 August 2021). "Heliox for croup in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (8) CD006822. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006822.pub6. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 8406495. PMID 34397099.

- ^ Port C (April 2009). "Towards evidence based emergency medicine: best BETs from the Manchester Royal Infirmary. BET 4. Dose of dexamethasone in croup". Emerg Med J. 26 (4): 291–2. doi:10.1136/emj.2009.072090. PMID 19307398. S2CID 6655787.

- ^ Kiple K (29 January 1993). The Cambridge World History of Human Disease. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 654–657. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521332866.092.

- ^ "croup | Origin and meaning of croup by Online Etymology Dictionary". www.etymonline.com. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ Marchessault V (November 2001). "Historical review of croup". Can J Infect Dis. 12 (6): 337–9. doi:10.1155/2001/919830. PMC 2094841. PMID 18159359.

- ^ Cormack JR (8 May 1875). "Meaning of the Terms Diphtheria, Croup, and Faux Croup". British Medical Journal. 1 (749): 606. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.749.606. PMC 2297755. PMID 20747853.

- ^ Loving S (5 October 1895). "Something concerning the diagnosis and treatment of false croup". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. XXV (14): 567–573. doi:10.1001/jama.1895.02430400011001d. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ Bennett JR (8 May 1875). "True and False Croup". British Medical Journal. 1 (749): 606–607. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.749.606-a. PMC 2297754. PMID 20747854.

- ^ Beard GM (1875). Our Home Physician: A New and Popular Guide to the Art of Preserving Health and Treating Disease. New York: E. B. Treat. pp. 560–564. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ^ Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases (8 ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. 2014. p. 762. ISBN 978-0-323-26373-3. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ Vanderpool P (December 2012). "Recognizing croup and stridor in children". American Nurse Today. 7 (12). Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ^ Bruce E (1995). Napoleon and Josephine. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- ^ "Death of Preston S. Brooks". Washington Evening Star. Washington, DC. 28 January 1857. p. 2.

External links

[edit]- "Croup". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Croup

View on GrokipediaClinical Presentation

Signs and Symptoms

Croup is characterized by a distinctive set of respiratory symptoms primarily affecting the upper airway in young children. The hallmark features include a barking or seal-like cough, inspiratory stridor—a high-pitched, wheezing sound during inhalation—hoarseness of the voice, and varying degrees of respiratory distress. These symptoms arise due to inflammation and narrowing of the larynx and trachea, leading to turbulent airflow.[2][1][9] Symptoms typically begin 1 to 2 days after the onset of an upper respiratory infection, such as a cold, and often intensify at night or in the early morning hours, potentially waking the child from sleep. This nocturnal worsening is attributed to the accumulation of secretions and positional changes that further compromise the airway. The barking cough may initially be mild but can escalate, becoming more frequent and harsh, especially with agitation or crying.[9][10][11] Associated symptoms commonly include a low-grade fever, coryza (runny or stuffy nose), and a hoarse or raspy voice, which may progress to temporary loss of voice in more pronounced cases. In mild presentations, children may exhibit only occasional coughing and stridor during activity or upset, with minimal impact on breathing. Severe cases, however, involve persistent stridor even at rest, visible retractions of the chest or neck muscles, increased respiratory effort, agitation, and in rare instances, cyanosis (bluish discoloration of the skin due to low oxygen).[1][12][13] Croup most frequently occurs in children between 6 months and 3 years of age, with peak incidence around 2 years, as their smaller airways are more susceptible to obstruction from swelling. Infants younger than 6 months or children older than 6 years are less commonly affected.[2][12][5]Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of croup encompasses several conditions that present with upper airway obstruction, stridor, or barking cough in children, necessitating careful clinical differentiation to guide management.[2] Common mimics include epiglottitis, bacterial tracheitis, foreign body aspiration, and spasmodic croup, each distinguished by specific historical and examination features.[5] Epiglottitis, classically caused by Haemophilus influenzae type B (now rare due to vaccination), but currently more often due to other bacteria such as streptococci or non-infectious causes, features sudden onset, high fever exceeding 39°C, drooling, dysphagia, and a muffled voice, with patients adopting a tripod position to maintain airway patency; unlike croup's viral prodrome, there is no barking cough, and agitation worsens symptoms dramatically.[2][14][15] Bacterial tracheitis typically follows a viral illness but progresses with persistent high fever, toxic appearance, purulent secretions, and severe respiratory distress unresponsive to initial therapies like racemic epinephrine, contrasting croup's milder course.[5] Foreign body aspiration presents abruptly with choking history, unilateral wheezing or stridor, and asymmetric breath sounds, often without fever or prodrome, differing from croup's bilateral involvement and gradual onset.[16] Spasmodic croup, a non-infectious variant linked to atopy or reflux, manifests as recurrent nocturnal episodes of stridor and barking cough without fever or toxicity, resolving quickly with supportive care and lacking the infectious etiology of classic croup.[2] A detailed history and physical examination are pivotal in distinguishing croup from these mimics; a typical viral upper respiratory prodrome with low-grade fever and nocturnal worsening supports croup, while rapid progression or absence of such history raises suspicion for bacterial or mechanical causes.[5] Atypical features warranting further evaluation include high fever greater than 39°C, drooling, tripod positioning, unilateral signs, or failure to improve with standard croup treatments, prompting consideration of urgent imaging or specialist consultation to rule out life-threatening alternatives.[16]| Condition | Typical Age | Key Distinguishing Features | Historical Clues |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epiglottitis | 3-12 years | High fever, drooling, dysphagia, tripod position, muffled voice | Sudden onset, no prodrome |

| Bacterial Tracheitis | <6 years | Toxic appearance, purulent secretions, unresponsive to epinephrine | Follows viral illness, rapid worsening |

| Foreign Body Aspiration | <3 years | Unilateral stridor/wheezing, asymmetric exam | Choking episode, abrupt onset |

| Spasmodic Croup | 6 mo-3 yr | No fever, recurrent nocturnal episodes | Atopic history, quick resolution |

Causes and Pathophysiology

Viral Causes

Croup is predominantly caused by viral infections, which account for the vast majority of cases, with parainfluenza viruses being the most common etiologic agents.[2] Parainfluenza viruses (types 1–3) account for approximately 75% of croup cases, with type 1 being the most common, responsible for biennial outbreaks in the fall of odd-numbered years in temperate climates.[5] Types 2 and 3 of parainfluenza virus are also frequently implicated, with type 2 causing sporadic cases year-round and type 3 peaking in spring and early summer.[17] Other viruses associated with croup include respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), which is more common in infants and during winter months; influenza A and B viruses, often circulating in winter; adenovirus; human metapneumovirus, typically seen in late winter to early spring; and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), associated with increased croup incidence during COVID-19 surges as of 2025.[2][18] These viruses contribute to the remaining cases, with seasonal variations influencing overall epidemiology—for instance, RSV and influenza drive increased incidence during colder months.[19] Transmission of these viruses occurs primarily through airborne respiratory droplets or direct contact with contaminated secretions, such as during close personal interactions or coughing.[2] The typical incubation period ranges from 2 to 6 days following exposure, after which upper airway inflammation develops.[5]Bacterial Causes

Bacterial causes of croup are rare, comprising less than 5% of all cases, and often manifest as secondary infections superimposed on initial viral laryngotracheobronchitis.[20] These superinfections typically involve pathogens such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, or Moraxella catarrhalis, which exacerbate the underlying inflammation and lead to more severe airway obstruction.[2] Patients with these secondary bacterial infections commonly exhibit higher fever, purulent secretions, and a toxic clinical appearance, distinguishing them from the milder viral forms and indicating a poorer short-term prognosis if untreated.[20] The incidence of such severe bacterial complications remains low, affecting fewer than 1% of croup cases overall and less than 3% of those requiring hospitalization.[2] Primary bacterial etiologies are even less common but include bacterial tracheitis, which can arise independently or as a complication of viral croup, primarily caused by Staphylococcus aureus or group A Streptococcus (Streptococcus pyogenes).[21] This condition involves bacterial invasion of the trachea, resulting in thick, purulent membranes that cause significant respiratory distress, often necessitating intensive care.[20] Additionally, Mycoplasma pneumoniae may produce a mild, croup-like illness in some children, though it rarely leads to the classic stridor and barking cough.[20] Viral predisposition to these bacterial overlays underscores the importance of monitoring for progression in initially viral presentations.[2] Historically, diphtheria due to Corynebacterium diphtheriae was a major primary bacterial cause of croup-like symptoms, frequently termed "membranous croup" in the pre-vaccine era before the 20th century.[22] This toxin-producing infection formed pseudomembranes in the larynx and trachea, mimicking viral croup but with higher mortality rates due to airway occlusion and systemic complications.[23] Widespread diphtheria vaccination since the mid-20th century has drastically reduced its incidence in developed countries, rendering it an exceedingly rare contributor today.[22]Non-infectious Causes

Spasmodic croup, a non-infectious variant, accounts for a minority of cases and is often triggered by allergic reactions or gastroesophageal reflux, leading to acute subglottic edema without a preceding viral illness.[24] It typically presents suddenly, often at night, with barking cough and stridor, and may recur in children with atopic conditions.[25]Pathophysiology

Croup arises from an initial infection that triggers an inflammatory response in the upper airway, primarily affecting the subglottic region.[2] This leads to a cascade of pathophysiological events characterized by the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α, which promote the recruitment of immune cells including lymphocytes, neutrophils, and histiocytes to the site of infection.[26][27] The resulting cellular infiltration and activation cause endothelial damage, loss of ciliary function, and increased vascular permeability in the lamina propria, submucosa, and adventitia of the larynx, trachea, and bronchi.[27] This inflammatory process peaks in intensity between 24 and 48 hours post-infection, with maximal edema and mucus production exacerbating airway compromise.[5] The hallmark of croup pathophysiology is subglottic edema, where swelling in the narrow subglottic space—circumscribed by the rigid cricoid cartilage—dramatically reduces the airway diameter, even a small increase in mucosal thickness can narrow the lumen by up to 75%.[24] Inflammation and accumulation of viscous mucus further obstruct the airway, creating a fixed partial obstruction that limits airflow and promotes turbulent flow, particularly during inspiration when negative intrathoracic pressure exacerbates the narrowing.[2][27] This turbulent airflow generates the characteristic inspiratory stridor, a high-pitched sound resulting from vibrations in the edematous subglottic tissues.[24] Radiographic imaging may reveal the "steeple sign" on anteroposterior neck X-ray, a tapered narrowing of the subglottic trachea resembling a church steeple, directly attributable to the circumferential edema in this region.[2][27] Overall, these mechanisms culminate in increased work of breathing and potential hypoxemia if the obstruction progresses, though the process is typically self-limited as the immune response resolves the inflammation over several days.[28]Diagnosis

Clinical Evaluation

The diagnosis of croup is primarily clinical, relying on a characteristic history and physical examination to confirm upper airway inflammation consistent with viral laryngotracheobronchitis in children, typically aged 6 months to 3 years.[29][2] Routine laboratory or imaging studies are generally unnecessary in typical cases, as the presentation of a barking cough, hoarseness, and inspiratory stridor following a viral prodrome strongly supports the diagnosis.[20] History taking focuses on recent upper respiratory infection symptoms, such as rhinorrhea, low-grade fever, and cough, which often precede the acute onset of stridor and barking cough by 1 to 2 days.[2] Inquiry into exposure to ill contacts is essential, given the contagious nature of common viral etiologies like parainfluenza.[20] Vaccination status should be reviewed to exclude vaccine-preventable conditions that may mimic croup, such as Haemophilus influenzae type b epiglottitis in unvaccinated children.[22] On physical examination, auscultation reveals inspiratory stridor, a high-pitched sound indicating laryngeal obstruction, often accompanied by a seal-like barking cough and hoarseness.[29] Assessment of respiratory effort includes evaluation for signs of distress, such as intercostal or subcostal retractions, nasal flaring, tachypnea, and, in severe cases, cyanosis or use of accessory muscles.[2] The examination should be performed calmly to avoid agitation, which can exacerbate stridor.[20] Ancillary tests are reserved for cases where the diagnosis is uncertain or mimics are suspected. A lateral neck radiograph may demonstrate the classic "steeple sign" of subglottic narrowing if performed, but it is not routine due to radiation exposure risks and the reliability of clinical findings in typical presentations.[29][2] Viral testing via nasopharyngeal swab is not recommended routinely, as it does not alter management and may distress the child.[20]Severity Classification

Severity classification in croup is essential for guiding clinical management and determining the appropriate level of care, with the Westley Croup Score serving as the most widely used standardized tool for assessing disease severity in children.[2] This score, originally developed in 1981 and validated in subsequent studies, evaluates five key clinical features to provide an objective measure, though it incorporates some subjective assessments.[6] The Westley Croup Score components are as follows:| Component | Scoring Details |

|---|---|

| Level of consciousness | Normal (including sleep): 0; Disoriented: 5 |

| Cyanosis | None: 0; With agitation: 4; At rest: 5 |

| Stridor | None: 0; With agitation: 1; At rest: 2 |

| Air entry | Normal: 0; Decreased: 1; Markedly decreased: 2 |

| Retractions | None: 0; Mild: 1; Moderate: 2; Severe: 3 |