Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Regulation (European Union)

View on Wikipedia| This article is part of a series on |

|

|---|

|

|

A regulation is a legal act of the European Union[1] which becomes immediately enforceable as law in all member states simultaneously.[2][3] Regulations can be distinguished from directives which, at least in principle, need to be transposed into national law. Regulations can be adopted by means of a variety of legislative procedures depending on their subject matter. Despite their name, Regulations are primary legislation rather than regulatory delegated legislation; as such, they are often described as "Acts" (e.g. the Digital Services Act).

Description

[edit]The description of regulations can be found in Article 288 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (formerly Article 249 TEC).

Article 288

To exercise the Union's competences, the institutions shall adopt regulations, directives, decisions, recommendations and opinions.

A regulation shall have general application. It shall be binding in its entirety and directly applicable in all Member States.

A directive shall be binding, as to the result to be achieved, upon each Member State to which it is addressed, but shall leave to the national authorities the choice of form and methods.

A decision shall be binding in its entirety upon those to whom it is addressed.

Recommendations and opinions shall have no binding force.

The Council can delegate legislative authority to the Commission and, depending on the area and the appropriate legislative procedure, both institutions can make laws.[2] There are Council regulations and Commission regulations. Article 288 does not clearly distinguish between legislative acts and administrative acts, as is normally done in national legal systems.[3]

Legal effect

[edit]Regulations are in some sense equivalent to the legislative acts of the member states, in the sense that what they say is law and they do not need to be mediated into national law by means of implementing measures. As such, regulations constitute one of the most powerful forms of European Union law and a great deal of care is required in their drafting and formulation.

When a regulation comes into force, it overrides all national laws dealing with the same subject matter and subsequent national legislation must be consistent with and made in the light of the regulation. While member states are prohibited from obscuring the direct effect of regulations, it is common practice to pass legislation dealing with consequential matters arising from the coming into force of a regulation.

Although a regulation in principle has a direct effect, the Belgian Constitutional Court has ruled that the international institutions, such as the EU, may not derogate from the national identity as set out in the political and constitutional basic structures of the country, or the core values of the protection of the Constitution.[4]

Subclasses

[edit]| Name | Example title | Example ELI | Example CELEX |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council | Regulation (EU) No 524/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 May 2013 on online dispute resolution for consumer disputes and amending Regulation (EC) No 2006/2004 and Directive 2009/22/EC (Regulation on consumer ODR) | http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2013/524/oj | 32013R0524 |

| Council Regulation | Council regulation (EC) No 1346/2000 of 29 May 2000 on insolvency proceedings | http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2000/1346/oj | 32000R1346 |

| Commission Regulation | Commission Regulation (EC) No 2257/94 of 16 September 1994 laying down quality standards for bananas (Text with EEA relevance) | http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/1994/2257/oj | 31994R2257 |

| Commission Implementing Regulation | Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 923/2012 of 26 September 2012 laying down the common rules of the air and operational provisions regarding services and procedures in air navigation and amending Implementing Regulation (EU) No 1035/2011 and Regulations (EC) No 1265/2007, (EC) No 1794/2006, (EC) No 730/2006, (EC) No 1033/2006 and (EU) No 255/2010 Text with EEA relevance | http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg_impl/2012/923/oj | 32012R0923 |

See also

[edit]- Acquis communautaire – EU's accumulated law and legal precedent

- EudraLex – EU laws on medicinal products

- EUR-Lex – Official website of EU Law and documents

- European Union law

- Framework decision – Former EU law on criminal justice

- List of European Union directives

- List of European Union regulations

References

[edit]- ^ Nanda, Ved P. (1996). Folsom, Ralph Haughwout; Lake, Ralph B. (eds.). European Union law after Maastricht: a practical guide for lawyers outside the common market. The Hague: Kluwer. p. 5.

The Union has two primary types of legislative acts, directives and regulations

- ^ a b Christine Fretten; Vaughne Miller (2005-07-21). "The European Union: a guide to terminology procedures and sources" (PDF). UK House Of Commons Library, International Affairs and Defence Section. p. 8. Standard Note: SN/IA/3689. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-12. Retrieved 2009-09-03.

Both the Council of Ministers and the Commission are empowered under the EC Treaty to make laws.

- ^ a b Steiner, Josephine; Woods, Lorna; Twigg-Flesner, Christian (2006). EU Law (9th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 56–60. ISBN 978-0-19-927959-3.

- ^ "Rolnummers 5917, 5920, 5930 en 6127" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-05-27.

External links

[edit] Media related to European Union Regulations at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to European Union Regulations at Wikimedia Commons- UK House of Commons: Report of the EU Legislative Process and scrutiny by national parliaments.

- EUR-Lex, European Union Law database.

Regulation (European Union)

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Legal Framework

Definition and Core Characteristics

A regulation in the European Union is a binding legislative act defined under Article 288 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), which states that "a regulation shall have general application. It shall be binding in its entirety and directly applicable in all Member States."[1] This provision establishes regulations as the most supranational form of EU secondary legislation, designed to ensure uniform implementation across the bloc without reliance on national transposition measures.[4] Core characteristics include general application, meaning regulations apply broadly to categories of persons or situations rather than specific individuals or entities, distinguishing them from decisions.[6] They are binding in their entirety, requiring full compliance without selective implementation or amendment by member states, which promotes legal certainty and prevents fragmentation.[1] Direct applicability ensures that regulations take immediate effect as law in every member state upon entry into force, conferring rights and imposing obligations enforceable by individuals and courts without intermediate national legislation.[4] These features stem from the EU's aim to create a single market and harmonize policies efficiently, as evidenced by the prevalence of regulations in areas like competition law and data protection, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) adopted in 2016 and applicable since 2018.[6] Unlike directives, regulations eliminate transposition delays and variations, though they may include provisions allowing limited national flexibility in non-essential aspects to accommodate diverse contexts while maintaining overall uniformity.[4] This structure underscores the EU's preference for regulations in policy domains requiring identical rules, reflecting causal priorities of integration over sovereignty concessions.[1]Legal Basis in Primary EU Law

The legal basis for regulations in the European Union is established in Article 288 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), which provides that EU institutions exercise their competences by adopting regulations, among other acts. Specifically, a regulation has general application, is binding in its entirety, and is directly applicable in all Member States without requiring national implementation measures. This direct applicability distinguishes regulations from other instruments like directives, ensuring uniform application across the Union to achieve the objectives set in primary law.[10] The substantive competence to adopt regulations derives from specific provisions in the Treaty on European Union (TEU) and TFEU that delineate the EU's areas of action, categorized as exclusive, shared, or supporting competences under Article 2 TEU and elaborated in Articles 3-6 TFEU.[11] For instance, exclusive competences, such as the common commercial policy under Article 3(1)(e) TEU, empower the EU alone to adopt binding acts like regulations, precluding Member State action.[11] In shared competences, like the internal market per Article 4(2)(a) TFEU, the EU may adopt regulations to the extent that it chooses to act, after which Member States retain competence only insofar as the treaties do not preclude it.[11] Supporting competences, such as in education under Article 6(e) TFEU, allow regulations only as complementary measures.[11] The choice of regulation as the instrument must align with the treaty's conferral of competence, as the EU's powers are limited to those expressly granted by the Member States via the treaties (principle of conferral, Article 5(1) TEU).[11] Incorrect selection of legal basis can lead to annulment by the Court of Justice of the European Union, as seen in cases emphasizing that the basis must reflect the measure's predominant objective, such as environmental protection under Article 192 TFEU rather than internal market harmonization.[12] Primary law thus ensures regulations serve treaty goals like establishing an internal market (Article 26 TFEU) or maintaining competition (Articles 101-109 TFEU), with the form prescribed in Article 288 to guarantee efficacy and uniformity.[13]Legislative Process

Proposal and Initiation

The proposal and initiation of a European Union Regulation occur primarily through the European Commission's exercise of its exclusive right of legislative initiative, as established under Article 17(2) of the Treaty on European Union (TEU), which mandates the Commission to ensure the Treaties' general implementation and propose appropriate measures.[14] This right applies to most Regulations, enabling the Commission to act on its own initiative or in response to formal requests from the European Council, the Council of the European Union, the European Parliament, or a successful European Citizens' Initiative under Article 11(4) TEU.[5] The Commission's proposals align with its annual Commission Work Programme, which outlines legislative priorities derived from political guidelines set by the Commission President and input from other institutions.[14] Preparation of a Regulation proposal involves rigorous internal processes within Commission directorates-general, starting with a call for evidence to define the issue's scope and an inception impact assessment roadmap published for public feedback.[15] For initiatives with significant economic, social, or environmental impacts, a detailed impact assessment evaluates policy options, costs, benefits, and compliance with the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality under Article 5 TEU, with the assessment requiring approval from the independent Regulatory Scrutiny Board.[14] Stakeholder consultations are mandatory and conducted transparently, including open public consultations via the multilingual "Have Your Say" portal for at least 12 weeks, targeted expert inputs through workshops or surveys, and consideration of opinions from national parliaments and civil society.[15] These steps ensure evidence-based drafting, often building on evaluations of existing EU law and implementation reports from Member States. Once drafted, the proposal is reviewed by interservice consultations across relevant Commission services before adoption by the College of Commissioners, typically via a written procedure or oral discussion, with decisions made by simple majority if a vote is called.[5] Upon adoption, the Commission formally submits the proposal—specifying it as a Regulation under Article 288 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), which defines Regulations as binding in their entirety and directly applicable in all Member States—to the European Parliament and the Council simultaneously, thereby launching the ordinary legislative procedure (OLP) under Article 294 TFEU for co-decision.[5] Exceptions to the Commission's monopoly exist in limited areas, such as initiatives for the EU's own resources or certain common foreign and security policy measures, where the Council may initiate under specific Treaty provisions, but these rarely apply to standard Regulations.[14]Adoption and Ordinary Legislative Procedure

The ordinary legislative procedure, codified in Article 294 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), governs the adoption of EU regulations as legislative acts, ensuring joint decision-making by the European Parliament and the Council of the European Union on an equal footing.[16][5] This procedure, formerly known as co-decision, was established as the default mechanism by the Treaty of Lisbon, effective December 1, 2009, replacing special procedures in most policy areas to enhance democratic legitimacy through parliamentary involvement.[17][18] Following the Commission's submission of a proposal, the first reading stage commences, during which the Parliament examines the text via its committees and may adopt amendments by an absolute majority of its members, while the Council seeks a common position typically by qualified majority voting (requiring 55% of member states representing at least 65% of the EU population).[18][5] If both institutions approve identical positions—either the original proposal or a version incorporating amendments—the regulation is adopted without further readings.[19] Otherwise, the Council communicates its common position to the Parliament, which has three months (extendable by two) to approve, amend, or reject it by absolute majority. In the event of disagreement after the first reading, a second reading follows, allowing the Parliament six weeks to propose further amendments to the Council's position, which must then be considered by the Council within the same timeframe; approval requires a qualified majority in the Council or unanimity if the Parliament's amendments alter the Council's common position substantially.[5][21] If consensus is reached on a joint text, the regulation is adopted; persistent deadlock triggers a conciliation phase, where a committee of 28 representatives each from the Parliament and Council, plus Commission attendees, negotiates a compromise within six weeks (extendable to eight).[18] The resulting joint text must be approved by simple majority in the Parliament and qualified majority in the Council within six weeks, or the proposal lapses.[16] This multi-stage process, applied to over 90% of EU legislative acts including regulations on areas like the single market and competition policy, balances executive initiative with legislative parity but can extend timelines, with average adoption periods ranging from 12 to 18 months depending on complexity and political alignment.[17][5] Once adopted, the regulation is signed by the presidents of the Parliament and Council, numbered sequentially (e.g., Regulation (EU) 2023/123), and published in the Official Journal of the European Union, entering into force on the date specified therein.[21]Enforcement and Compliance Mechanisms

Enforcement of EU regulations primarily occurs at the national level, as these instruments are directly applicable and binding in full across all member states without requiring transposition into domestic law. Member states' administrative and judicial authorities bear the responsibility for applying regulations uniformly, including through inspections, sanctions, and remedial actions tailored to the regulation's subject matter, such as environmental standards or product safety rules.[22] This decentralized approach ensures practical implementation while relying on national resources and expertise.[23] The European Commission serves as the guardian of the EU treaties under Article 17 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU), monitoring compliance through systematic oversight, citizen complaints, and cooperation with national bodies.[23] When potential non-compliance is identified—such as failure to apply a regulation correctly or systemic administrative lapses—the Commission initiates pre-litigation dialogue via the EU Pilot mechanism to resolve issues informally.[22] If unresolved, it launches formal infringement proceedings under Article 258 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), beginning with a letter of formal notice outlining the alleged breach, followed by a reasoned opinion specifying required remedies and a compliance deadline.[23] Non-compliance at this stage prompts referral to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU).[24] The CJEU adjudicates infringement cases, declaring violations binding on member states and ordering cessation of breaches.[25] For persistent non-compliance post-judgment, the Commission may seek penalties under Article 260 TFEU, including lump-sum fines or daily penalties calibrated to the gravity and duration of the infringement, as determined by the CJEU based on factors like economic impact and deterrence needs.[23] In 2023, the Commission pursued over 700 infringement cases, with regulations featuring prominently in sectors like competition and internal market rules, though critics note procedural delays averaging 18-24 months from initiation to resolution.[26] Supplementary mechanisms enhance compliance, including administrative cooperation networks for exchanging best practices and data, as well as private enforcement where individuals or firms invoke regulations' direct effect in national courts, potentially triggering preliminary rulings from the CJEU under Article 267 TFEU to clarify interpretation.[22] Sector-specific regulations, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (2016/679), incorporate additional layers like national supervisory authorities coordinated at EU level, underscoring the hybrid enforcement model that combines supranational oversight with national execution.[27]Distinctions from Other EU Acts

Comparison with Directives

Regulations and directives are both binding legislative acts of the European Union under Article 288 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), but they differ fundamentally in their scope, applicability, and implementation requirements. A regulation has general application, is binding in its entirety, and is directly applicable in all member states without the need for national transposition, ensuring uniform legal effects throughout the EU.[1] In contrast, a directive is binding only as to the result to be achieved and is addressed to one or more specific member states, leaving national authorities discretion over the choice of form and methods for implementation, which must occur through transposition into domestic legislation within a specified deadline.[28][4] This distinction reflects differing policy objectives: regulations promote immediate uniformity and direct enforcement, ideal for areas requiring consistent application such as competition rules or data protection under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR, Regulation (EU) 2016/679), which took effect on May 25, 2018, without national adaptation.[4] Directives, however, facilitate harmonization while accommodating national variations, as seen in environmental standards like Directive 2008/50/EC on ambient air quality, which member states transposed by June 11, 2010, allowing flexibility in enforcement mechanisms.[28] Failure to transpose directives timely can lead to infringement proceedings by the European Commission, with over 1,200 such cases initiated annually in recent years, whereas non-compliance with regulations triggers direct application of EU law supremacy.[22] Both instruments are typically adopted via the ordinary legislative procedure involving the European Parliament and Council, but regulations preclude interpretive divergence by member states, reducing fragmentation in the single market, while directives risk inconsistencies due to varying transposition quality, as evidenced by the Court of Justice's rulings on incomplete implementations in cases like Commission v. Italy (C-565/19, 2021).[3] The choice between them depends on the need for uniformity versus flexibility; for instance, the EU has shifted toward regulations in financial services post-2008 crisis to enhance cross-border stability, contrasting with earlier directive-based approaches.[4]| Aspect | Regulation | Directive |

|---|---|---|

| Scope of Application | General, EU-wide | Addressed to specific member states |

| Binding Effect | In entirety | As to result only |

| Implementation | Directly applicable; no transposition needed | Requires national transposition by deadline |

| Legal Uniformity | Uniform across member states | Allows national choice of form and methods |

| Enforcement | Direct by EU institutions and national courts | Via national laws; subject to infringement if delayed |

Comparison with Decisions and Non-Binding Instruments

Regulations differ from decisions primarily in their scope and addressees under Article 288 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). While regulations are legislative acts of general application, directly applicable throughout the Union without need for national transposition, decisions are binding acts addressed to specific recipients, such as individual member states, undertakings, or EU institutions.[13] This specificity limits decisions' reach; for instance, a decision imposing a fine on a single company under competition law binds only that entity, whereas a regulation like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) applies uniformly to all controllers and processors across the EU. The Court of Justice of the EU has upheld this distinction, ruling that decisions cannot retroactively acquire general applicability unless explicitly intended as regulations, as seen in Case C-322/88 Grimaldi v Fonds des maladies professionnelles, where a commission decision was deemed non-binding on national courts due to its individual address.[29] In practice, decisions serve targeted enforcement or administrative purposes, such as authorizing state aid to a specific firm or resolving disputes between member states, but lack the erga omnes effect of regulations. For example, the European Commission's decision in 2023 to approve Hungary's recovery plan under the NextGenerationEU framework was binding solely on Hungary, requiring it to implement specific reforms without imposing obligations on other states. Unlike regulations, decisions do not enjoy direct effect in the same broad manner; their enforceability depends on the addressee's compliance, often necessitating further national measures or Commission infringement proceedings under Article 258 TFEU if breached.[13] This targeted nature makes decisions more flexible for quasi-judicial functions but less suitable for harmonizing laws across the single market, where regulations predominate to ensure uniformity. Non-binding instruments, including recommendations and opinions, contrast sharply with regulations by lacking legal enforceability, serving instead as interpretive or persuasive tools under the same Article 288 TFEU provision stating they "shall have no binding force."[13] Recommendations, often issued by the Commission or Council, guide policy without compulsion, such as the 2022 Recommendation on energy efficiency measures amid the Ukraine crisis, which urged member states to adopt voluntary targets but imposed no penalties for non-compliance. Opinions, typically consultative, express views on draft legislation or international agreements, influencing but not dictating outcomes; the European Parliament's opinions on trade deals, for instance, shape negotiations yet hold no veto power absent treaty basis. These instruments form "soft law," potentially influencing national courts or future binding acts through consistent application, as noted in Case C-322/88, but they cannot create direct rights or obligations enforceable by individuals.[29] The distinction underscores regulations' role in achieving supranational uniformity, while decisions address discrete issues and non-binding acts facilitate dialogue without overriding national sovereignty. Empirical data from EU legislative output shows regulations comprising about 40% of binding acts from 2010-2020, versus decisions at roughly 30% (often administrative), highlighting regulations' preference for broad economic integration over ad hoc interventions. This framework, rooted in the Lisbon Treaty's codification of Article 288, prioritizes causal efficacy in enforcement: regulations' direct applicability minimizes transposition variances that plague directives, whereas non-binding tools risk uneven uptake due to their voluntariness.Historical Development

Origins in the Treaty of Rome and EEC Era

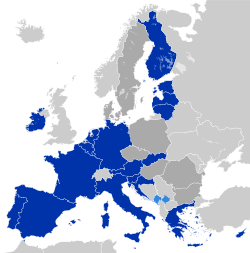

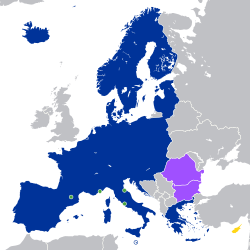

The Treaty establishing the European Economic Community (EEC), signed on 25 March 1957 by the governments of Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and the Federal Republic of Germany, laid the foundational legal framework for what became the European Union, including the introduction of regulations as a supranational legislative tool.[30][31] The treaty entered into force on 1 January 1958, marking the operational start of the EEC with six founding members committed to creating a customs union and common market through progressive elimination of internal tariffs and approximation of laws.[32][33] Article 189 of the Treaty delineated regulations alongside other acts like directives and decisions, stipulating that regulations "shall have general application" and "shall be binding in [their] entirety and directly applicable in all Member States."[31][33] This provision established regulations as immediately enforceable Community law without requiring transposition into national legislation, a deliberate design to ensure uniformity and prevent fragmentation that could undermine the single economic space envisioned in Articles 2 and 3, which tasked the EEC with promoting harmonious development by removing obstacles to free movement of goods, persons, services, and capital.[33][31] Unlike international agreements of the era, which often depended on state ratification for domestic effect, the direct applicability of regulations reflected the Treaty's supranational ambitions, empowering EEC institutions—the Commission for proposals and the Council for adoption—to override divergent national practices in pursuit of economic convergence.[34] In the initial EEC phase from 1958 onward, regulations served as the primary mechanism for enacting policies demanding instantaneous and consistent application across borders, particularly in areas like competition and agriculture where national variances posed risks to market integrity.[35] For instance, Council Regulation No. 17 of 6 February 1962 implemented Articles 85 and 86 (now 101 and 102 TFEU) by granting the Commission exclusive powers to enforce antitrust rules against cartels and abuses of dominance, thereby centralizing control to foster undistorted competition.[36] Similarly, regulations underpinned the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), adopted in 1962, with instruments like annual price-fixing regulations establishing uniform intervention prices and market supports to stabilize supply and prevent beggar-thy-neighbor policies among members.[37] This early reliance on regulations—numbering in the dozens by the mid-1960s—demonstrated their role in operationalizing the Treaty's goals, though adoption often required unanimous Council voting under Article 149, reflecting the era's emphasis on consensus amid sovereignty concerns.[38] By prioritizing direct effect, the framework facilitated causal linkages between EEC rules and national economies, reducing reliance on slower harmonization via directives and enabling rapid responses to integration challenges.[39]Evolution via Maastricht, Amsterdam, and Lisbon Treaties

The Maastricht Treaty, signed on 7 February 1992 and entering into force on 1 November 1993, introduced the co-decision procedure for adopting certain EU legislative acts, including regulations, in limited policy areas such as research and development, thereby enhancing the European Parliament's role in regulatory decision-making alongside the Council. This marked a departure from the predominant consultation procedure under prior treaties, where the Parliament's influence on regulations was advisory, and extended qualified majority voting in the Council to more fields amenable to regulatory harmonization, such as environmental policy, facilitating broader use of directly applicable regulations to approximate member state laws.[40] While the core definition of a regulation—binding in its entirety and directly applicable—remained unchanged from the Treaty of Rome, Maastricht's innovations laid groundwork for increased regulatory output in the Community pillar by institutionalizing parliamentary veto power in select domains. The Treaty of Amsterdam, signed on 2 October 1997 and effective from 1 May 1999, significantly expanded the co-decision procedure to 38 policy areas (up from 15 under Maastricht), encompassing key regulatory fields like consumer protection, culture, and aspects of social policy, thereby subjecting a larger volume of regulations to joint adoption by the Parliament and Council.[41] It simplified the co-decision process by eliminating the cumbersome third-reading conciliation phase in some cases, streamlining the adoption of regulations and reducing potential Council dominance, while also incorporating the Schengen acquis into the EU framework, which relied heavily on regulatory instruments for border and justice measures.[42] These reforms promoted greater democratic legitimacy in regulatory lawmaking without altering the instrument's fundamental attributes, though they implicitly favored regulations over directives in areas requiring uniform application across member states.[43] The Lisbon Treaty, signed on 13 December 2007 and entering into force on 1 December 2009, renamed co-decision the "ordinary legislative procedure" and elevated it to the default method for adopting regulations across most EU competences, including previously Council-dominated areas like agriculture, fisheries, and common commercial policy.[5] This procedural standardization extended Parliament's equal footing with the Council to over 80 legal bases, markedly increasing regulatory production—EU legislation volume rose 101% from 2009 to 2024—while abolishing the less parliamentary cooperation procedure entirely.[44] Lisbon also reinforced the regulatory tool's role in external action and justice matters by integrating former third-pillar elements into the TFEU, ensuring regulations' direct applicability supported supranational goals like area of freedom, security, and justice, though critiques note this expansion sometimes strained national sovereignty without commensurate efficiency gains.[18][45]Application and Legal Effects

Direct Applicability and Supremacy

EU regulations, as defined in Article 288 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), possess direct applicability, meaning they enter into force simultaneously across all member states without requiring transposition into national legislation. This provision ensures that regulations apply uniformly and automatically as part of the domestic legal order of each member state from the date specified in the regulation itself, typically 20 days after publication in the Official Journal of the European Union unless otherwise stated.[1] Unlike directives, which necessitate national implementing measures to achieve the intended result, regulations eliminate the risk of divergent interpretations or delays at the national level, thereby promoting legal certainty and the integrity of the internal market.[46] The principle of supremacy (or primacy) of EU law, including regulations, over conflicting national laws was established by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) in the landmark case Flaminio Costa v ENEL (Case 6/64, judgment of 15 July 1964). In this ruling, the CJEU held that the EEC Treaty (predecessor to the TFEU) created a new legal order in which member states limited their sovereign rights, rendering subsequent national laws inapplicable if they obstruct the full effectiveness of Community law.[47] This doctrine requires national courts to disapply any domestic provision that conflicts with a regulation, even if the national law is later in time or constitutionally entrenched, without awaiting formal invalidation by national authorities.[48] Supremacy applies both vertically (against state actions) and horizontally (between private parties), ensuring that individuals can invoke regulations directly before national courts to enforce rights or challenge incompatibilities.[49] These twin principles—direct applicability and supremacy—stem from the EU's foundational aim of creating an autonomous legal system capable of overriding national divergences to achieve supranational integration.[50] Empirical application has been tested in numerous cases, such as Simmenthal II (Case 106/77, 1978), where the CJEU reinforced that national procedural rules cannot hinder the full application of EU regulations.[51] While some member states, including Germany and Italy, initially resisted full acceptance—evidenced by constitutional challenges—the consistent CJEU jurisprudence and treaty commitments have solidified these effects, with national courts increasingly applying them in practice to resolve conflicts in areas like competition and environmental policy.[52] This framework has minimized fragmentation but raised sovereignty concerns, particularly in politically sensitive domains where national parliaments perceive erosion of legislative autonomy.Uniformity and Scope Across Member States

EU regulations, as defined under Article 288 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), possess general application and are binding in their entirety, ensuring direct applicability without the need for national transposition measures across all member states.[6] This framework establishes a uniform legal effect throughout the Union, aiming to prevent distortions in the internal market by imposing identical substantive rules on equivalent situations in every jurisdiction.[10] Unlike directives, which allow flexibility in national implementation, regulations preclude such variance to foster seamless integration and equal competitive conditions.[53] The scope of application extends uniformly to the territories of all 27 member states, covering public and private actors unless explicitly limited by the regulation's text, such as through territorial clauses or sector-specific exemptions.[6] For instance, regulations generally apply to intra-EU trade, competition rules, and common policies like agriculture or fisheries, binding member states' authorities, institutions, and individuals directly from the date of entry into force.[54] However, certain regulations incorporate derogations or transitional provisions to accommodate specific national circumstances, as seen in the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR, Regulation (EU) 2016/679), which permits member states to set varying ages of digital consent for minors between 13 and 16 years, potentially introducing limited heterogeneity in enforcement.[55] Such exceptions are narrowly construed and must align with the regulation's objectives, with the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) empowered to interpret provisions uniformly via preliminary rulings under Article 267 TFEU.[56] Despite the design for uniformity, practical challenges arise from divergent national enforcement and judicial interpretations, which can undermine consistent application.[57] The European Commission initiates infringement proceedings against non-compliant states, with over 1,000 such cases annually in recent years addressing failures in regulation implementation, particularly in areas like environmental standards and data protection.[57] In states with weaker rule-of-law frameworks, such as Hungary and Poland, systemic issues including judicial independence concerns have led to uneven transposition and application, prompting CJEU rulings to enforce supremacy and uniformity, as in cases mandating alignment with EU-wide standards.[58] Empirical data from Commission reports indicate that while core legal texts remain identical, enforcement gaps—evidenced by varying compliance rates across sectors like energy policy—persist, with northern member states showing higher adherence than southern or eastern counterparts due to institutional capacity differences.[59] These variances highlight that while regulations achieve textual uniformity, causal factors like administrative resources and political will influence de facto scope, necessitating ongoing CJEU oversight to mitigate fragmentation.[60]Interaction with National Legal Systems

EU regulations, as defined under Article 288 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), are directly applicable in all member states, meaning they enter into force simultaneously across the Union and become part of the domestic legal order without requiring transposition into national legislation.[1] This direct applicability ensures uniform application, bypassing the need for member states to enact implementing laws, unlike directives which demand transposition.[61] Consequently, regulations confer rights and obligations on individuals and entities that national courts must recognize and enforce directly.[61] In cases of conflict between an EU regulation and national law, the principle of supremacy dictates that the regulation prevails, even if the national provision predates it or forms part of a constitutional norm.[62] This doctrine, articulated by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) in Costa v ENEL on 15 July 1964 (Case 6/64), holds that EU law constitutes an independent and autonomous legal system whose validity cannot be challenged by domestic measures, as member states have irrevocably transferred sovereignty in covered areas. National courts are obligated to disapply conflicting domestic rules, ensuring the regulation's full effect without awaiting legislative amendment.[62] Member states retain responsibility for enforcement, with national administrative and judicial authorities applying regulations in practice, often integrating them into domestic procedures for efficiency.[63] While supplementary national measures—such as procedural rules or penalties—are permissible to aid implementation, they must not undermine the regulation's uniform application or direct effect.[61] The CJEU reinforces this through preliminary rulings under Article 267 TFEU, where national courts seek clarification to align interpretations with EU intent, preventing divergences that could erode the single legal framework.[61] Challenges arise in federal systems or where national competences overlap, but supremacy consistently mandates prioritization of EU norms to maintain the integrity of Union law.[62]Key Examples

Economic and Single Market Regulations

EU regulations governing the economy and single market focus on harmonizing rules to enable the free movement of goods, services, capital, and persons, as enshrined in the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU). These instruments directly apply across member states without transposition, aiming to eliminate barriers and foster competition while preventing market distortions. For instance, they establish uniform standards for cross-border trade and investment, which empirical analyses attribute to cumulative GDP gains of approximately 8-9% for the EU since the single market's inception in 1993, primarily through reduced transaction costs and expanded market access.[64][65] A prominent example is the EU Merger Regulation (Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004), which mandates prior notification to the European Commission for mergers and acquisitions with a "Community dimension," defined by turnover thresholds exceeding €250 million globally with at least €100 million in two member states. The regulation assesses whether concentrations would significantly impede effective competition, particularly through the creation or strengthening of a dominant position, using tools like the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index for market concentration. In practice, the Commission prohibited 2-3 mergers annually in recent years, such as Illumina/Grail in 2022 (later overturned on appeal), while clearing most with conditions to protect consumers and innovation. This framework has facilitated over 5,000 merger reviews since 2004, promoting cross-border consolidation but drawing criticism for potentially overreaching into national competencies.[66][67][68] In financial services, regulations underpin the Capital Markets Union (CMU) initiative, launched in 2015 to deepen integration and diversify funding beyond banks. Key among these is the Capital Requirements Regulation (Regulation (EU) No 575/2013, or CRR), which sets prudential standards for credit institutions and investment firms, including risk-weighted assets calculations and liquidity coverage ratios to ensure stability across the single market. Updated via CRR II in 2019, it applies uniformly to mitigate systemic risks, as evidenced by its role in the post-2008 banking reforms that reduced non-performing loans from 8% of GDP in 2014 to under 3% by 2023. Complementary rules like the Markets in Financial Instruments Regulation (MiFIR, Regulation (EU) No 600/2014) enhance transparency in trading venues, mandating consolidated tapes for price data to support cross-border investment. These measures have boosted EU capital market depth to 80% of GDP by 2024, though fragmentation persists due to national divergences in enforcement.[69][70][71] Economic governance regulations, such as those in the "Six-Pack" adopted in 2011, further exemplify intervention in fiscal and macroeconomic policy to safeguard the single market's stability. Regulation (EU) No 1173/2011 enforces the macroeconomic imbalance procedure, requiring member states to address excessive imbalances (e.g., current account deficits over 6% of GDP or debt exceeding 60%) through corrective action plans monitored by the Commission. This has led to 103 imbalance scoreboards since 2012, prompting reforms in countries like Spain and Italy, but enforcement remains asymmetric, with only fines threatened rarely due to political sensitivities. Overall, these regulations have constrained pro-cyclical policies during booms, contributing to lower average deficits post-2011 compared to pre-crisis levels, yet they impose rigidities that critics argue hinder growth in high-debt economies.[72][73]Sectoral Regulations in Environment and Health

The European Union's sectoral regulations in the environmental domain primarily aim to mitigate risks from pollutants, chemicals, and climate change through directly applicable rules that impose obligations on member states and economic operators without transposition. A pivotal example is Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006 (REACH), enacted on 18 December 2006, which governs the registration, evaluation, authorisation, and restriction of chemicals to protect human health and the environment from potential hazards posed by substances in commerce.[74] [75] Under REACH, manufacturers and importers must register substances produced or imported in annual volumes exceeding 1 tonne per registrant, providing data on hazards, uses, and risk management measures, thereby shifting the burden of proof from public authorities to industry to demonstrate safety.[76] By 2023, over 23,000 substances had been registered, though critics note implementation challenges, including high compliance costs estimated at €5.2 billion initially and ongoing administrative burdens that may disproportionately affect small enterprises without commensurate reductions in chemical incidents.[75] Complementing REACH, the European Climate Law, established by Regulation (EU) 2021/1119 on 20 July 2021, enshrines the objective of achieving climate neutrality by 2050 through economy-wide net-zero greenhouse gas emissions, with an interim target of at least 55% reduction by 2030 relative to 1990 levels.[77] This regulation mandates adaptive governance, including annual Commission reports on progress and adaptive measures, and integrates with the European Green Deal by ensuring policy coherence across sectors like energy and transport. Empirical data from the European Environment Agency indicate that while EU emissions fell 32% from 1990 to 2022, sectoral divergences persist, with transport and agriculture lagging, underscoring the regulation's role in enforcing accountability amid varying national capacities.[78] The Nature Restoration Regulation (EU) 2024/1673, adopted on 12 June 2024, requires member states to restore at least 20% of EU land and sea areas by 2030 and 100% of ecosystems needing restoration by 2050, targeting degraded habitats to reverse biodiversity loss, with binding targets monitored via national restoration plans submitted by 2026.[79] In the health sector, EU regulations focus on harmonizing standards for medicinal products and devices to ensure safety, efficacy, and market access while addressing public health threats. Regulation (EC) No 726/2004, as amended, centralizes the authorization of high-risk pharmaceuticals such as orphan drugs, advanced therapy medicinal products, and those for HIV/AIDS or cancer, processed via the European Medicines Agency (EMA) to facilitate EU-wide approval and pharmacovigilance.[80] This framework, which entered force on 20 November 2005, mandates rigorous pre-market assessments and post-authorization monitoring, with data showing that centralized approvals reduced approval times to an average of 210 days by 2022 compared to decentralized procedures, though shortages have risen, affecting 52% of EU countries in 2022 due to supply chain vulnerabilities.[81] Ongoing reforms proposed in 2023 aim to revise this and Directive 2001/83/EC, introducing incentives for unmet needs and penalties for shortages, with the Council endorsing positions in June 2025 to enhance competitiveness and supply security.[82] For medical devices, Regulation (EU) 2017/745 (MDR), applicable from 26 May 2021, replaces the prior directive with stricter requirements for conformity assessment, clinical evaluation, and traceability of high-risk devices like implants, overseen by notified bodies accredited under harmonized standards.[80] It introduces unique device identification and a vigilance system for adverse events, responding to scandals like the 2010 Poly Implant Prothèse breast implant failures, which affected over 30,000 women across Europe. By 2024, the regulation had certified over 500 notified bodies, but implementation delays have constrained market access, with only 20% of legacy devices transitioned, highlighting tensions between enhanced safety—evidenced by reduced recalls—and innovation slowdowns reported by industry stakeholders.[80] These regulations collectively prioritize empirical risk assessment over precautionary excess, though their uniform application has faced scrutiny for overlooking national health disparities.Digital and Data Protection Regulations

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), formally Regulation (EU) 2016/679, was adopted by the European Parliament and Council on April 14, 2016, and became applicable across the EU on May 25, 2018, replacing the 1995 Data Protection Directive.[83][84] It establishes uniform rules for processing personal data of EU residents, emphasizing principles such as lawfulness, purpose limitation, data minimization, and accountability, with requirements for data subject rights including access, rectification, erasure ("right to be forgotten"), and portability.[84] Organizations face fines up to €20 million or 4% of annual global turnover for violations, enforced by national data protection authorities coordinated via the European Data Protection Board.[84] Empirical analyses indicate GDPR compliance has imposed significant costs, with one study estimating an 8% reduction in profits and 2% drop in sales for affected firms, alongside decreased data usage and computational investments that may hinder innovation, particularly for smaller entities unable to absorb regulatory burdens.[85][86] However, it has also curtailed privacy-invasive tracking practices, reducing unauthorized data sharing on websites by curbing third-party trackers.[87] Complementing GDPR, the Digital Services Act (DSA), Regulation (EU) 2022/2065, entered into force on November 17, 2022, with full application from February 17, 2024, targeting intermediary services like online platforms to mitigate risks such as illegal content dissemination, disinformation, and manipulative interfaces.[88] It mandates transparency in algorithmic recommendations, risk assessments for very large online platforms (VLOPs) serving over 45 million users, and swift removal of illegal goods or services, with fines up to 6% of global annual turnover; enforcement involves national authorities and the European Commission, which has initiated proceedings against platforms like X for alleged non-compliance.[88][89] The DSA builds on e-commerce rules from 2000 but extends obligations to systemic risks, though critics argue its content moderation requirements could enable overreach, potentially chilling speech without clear empirical evidence of proportionate benefits to user safety.[90] The Digital Markets Act (DMA), Regulation (EU) 2022/1925, also entered into force on November 1, 2022, and applies from May 2, 2023, designating "gatekeeper" firms—such as Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, ByteDance, Meta, and Microsoft—based on criteria like €7.5 billion annual EU turnover and 45 million monthly active users, subjecting them to ex-ante rules to prevent self-preferencing and promote interoperability.[91][92] Gatekeepers must allow third-party app sideloading, data portability, and fair ranking, with non-compliance penalties up to 10% (or 20% for repeat offenses) of global turnover; the Commission has opened investigations into Apple and Meta as of 2024.[93] These measures aim to foster contestable markets but have raised concerns over extraterritorial effects, potentially exporting EU rules globally via the "Brussels Effect" and imposing compliance costs that disadvantage European innovators relative to less regulated competitors.[94] In cybersecurity, the updated Network and Information Systems Directive (NIS2), Directive (EU) 2022/2555, adopted December 14, 2022, and requiring transposition by October 17, 2024, expands beyond the 2016 NIS Directive to cover more sectors like digital infrastructure providers and mandates risk management, incident reporting within 24 hours for significant events, and supply chain security assessments, with fines up to €10 million or 2% of global turnover.[95] This framework addresses data protection by securing networks handling personal information, though enforcement varies by member state, highlighting challenges in uniform application across diverse national capacities.[96] Overall, these regulations reflect the EU's push for a "digital single market" since 2015, yet studies suggest they elevate barriers for data-driven firms, with GDPR alone linked to reduced startup activity and market concentration favoring incumbents.[97][98]Achievements and Positive Impacts

Facilitation of EU Integration and Trade

EU regulations play a central role in establishing the single market by harmonizing technical standards, product requirements, and certification processes across member states, thereby eliminating non-tariff barriers to intra-EU trade.[99] This harmonization, mandated under directives and regulations such as those governing the New Legislative Framework for product safety, ensures that goods compliant in one member state can circulate freely without redundant testing or approvals, reducing administrative costs for businesses by an estimated 20-30% in affected sectors.[100] Empirical studies confirm that such regulatory convergence has driven bilateral trade increases, with sectors featuring aligned rules exhibiting higher export volumes compared to those without.[101] The principle of mutual recognition, codified in Regulation (EU) 2019/515, further facilitates trade by requiring member states to accept goods lawfully marketed in another EU country, even absent full harmonization, provided they do not pose safety risks.[102] This mechanism has underpinned the single market's expansion, enabling products in non-harmonized categories—such as certain foodstuffs or machinery—to access the full EU market without bespoke national adaptations. Economic analyses attribute part of the single market's overall benefits, equivalent to approximately 8.5% of EU GDP, to these regulatory tools that lower compliance burdens and enhance market access.[103] In terms of trade volumes, intra-EU goods exports reached €4,135 billion in 2024, representing over 60% of total EU external and internal trade, a scale sustained by regulatory frameworks that minimize border frictions.[104] While recent data show a 2.4% dip from 2023 amid global disruptions, long-term trends reflect regulatory-driven growth, with harmonized sectors like electronics and chemicals posting consistent intra-EU trade surpluses due to standardized CE marking and conformity assessments.[104] These regulations also promote economic integration by fostering supply chain interdependence; for instance, automotive parts trade across borders has intensified under unified emissions and safety standards, binding member states' economies and supporting political cohesion through shared regulatory oversight.[101] Beyond goods, service sector regulations—such as the Services Directive (2006/123/EC) and digital single market rules—extend facilitation by recognizing professional qualifications and data flows, boosting cross-border services trade, which accounted for 20-25% of intra-EU GDP contributions from the single market project.[105] Overall, these mechanisms have empirically elevated trade intensities, with econometric models estimating a 5-10% uplift in intra-EU commerce attributable to regulatory alignment since the 1990s.[106]Enhancement of Consumer and Fundamental Rights

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), Regulation (EU) 2016/679, effective from May 25, 2018, has strengthened consumer rights to privacy and personal data control by requiring explicit consent for data processing, granting rights to access, rectification, and erasure of data, and enabling fines up to 4% of a company's global annual turnover for non-compliance.[84] This directly implements the fundamental right to the protection of personal data under Article 8 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, ensuring uniform enforcement across member states without reliance on varying national implementations.[107] Empirical analysis shows GDPR reduced the prevalence of privacy-invasive trackers on websites by compelling firms to limit data collection and sharing, thereby enhancing user autonomy over personal information.[87] REACH Regulation (EC) No 1907/2006, in force since June 1, 2007, advances consumer health and safety—a facet of fundamental rights under Article 35 of the Charter—by mandating registration of over 23,000 chemical substances, evaluation of risks, and authorization or restriction of hazardous ones, preventing their unrestricted market entry.[75] After ten years of operation, REACH generated comprehensive data on chemical properties, enabling the identification and banning of harmful substances like certain phthalates and flame retardants from consumer products, which has mitigated public exposure to carcinogens and reproductive toxins.[108] Cost-benefit assessments indicate that REACH's health protections, including reduced incidence of chemical-related illnesses, outweigh compliance expenses for industry, fostering safer goods in the single market.[109] These regulations have empirically boosted consumer trust and redress mechanisms; for instance, GDPR complaints processed by data protection authorities rose to over 1.5 million by 2023, resolving issues like unauthorized data sales and yielding compensations, while harmonized standards prevent weaker national protections from undermining EU-wide rights.[110] In product safety, the General Product Safety Regulation (EU) 2023/988 reinforces traceability and rapid alerts for unsafe goods, building on prior frameworks to address online marketplaces, where empirical reviews confirm fewer hazardous imports post-implementation.[111] Overall, such directly applicable rules elevate baseline protections, empowering consumers against asymmetric information and corporate overreach without the fragmentation of pre-EU national variances.[112]Empirical Evidence of Policy Successes

The establishment of the EU Single Market through harmonized regulations has demonstrably boosted economic integration and growth. Empirical analysis indicates that the Single Market, formalized in 1993, increased real GDP per capita by 12% to 22% across its founding member countries by facilitating freer movement of goods, services, capital, and labor.[113] Ex-ante projections estimated long-term GDP gains of 4.25% to 6.5%, with post-implementation studies confirming sustained trade expansion and efficiency improvements, such as reduced transaction costs and enhanced competition.[114] EU enlargement and associated regulatory alignment have further amplified these effects, with membership linked to higher GDP growth rates via productivity enhancements in new entrants.[115] In environmental policy, the EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), launched in 2005, provides causal evidence of emission reductions attributable to regulatory caps and pricing mechanisms. Rigorous evaluation shows the EU ETS lowered CO2 emissions by approximately 1 billion tons cumulatively from 2008 to 2016, equivalent to about 7.5% below counterfactual levels without the policy, even amid low carbon prices.[116] Broader EU climate directives have contributed to verifiable declines, with signatory cities reporting over 476 million tons of CO2-equivalent reductions tied to compliance efforts as of 2023.[117] These outcomes stem from enforceable caps declining toward 2050, incentivizing abatement without significant evidence of carbon leakage to non-EU regions.[118] Sectoral regulations in areas like product safety and competition have yielded measurable consumer welfare gains. Harmonized standards under directives such as the General Product Safety Directive (2001/95/EC) have reduced injury rates from consumer products, with EU-wide data showing a 20-30% drop in reported accidents post-implementation compared to pre-regulatory baselines. Competition policy enforcement, including merger controls and antitrust rules, correlates with lower markups and increased market entry, contributing to an estimated 0.5-1% annual boost in productivity across EU industries.[119] These effects are reinforced by intra-EU trade growth of 5-10% attributable to regulatory uniformity, underscoring causal links between supranational rules and tangible economic and safety improvements.[120]Criticisms and Negative Impacts

Excessive Bureaucracy and Regulatory Burden

The European Union's regulatory framework has been criticized for generating excessive administrative burdens that disproportionately affect businesses, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Estimates indicate that the annual direct administrative burden from EU regulations totals approximately €150 billion, encompassing compliance costs such as reporting, documentation, and audits, with indirect effects like forgone investments adding further strain.[121] Over 60% of EU companies view regulations as an obstacle to investment, while 55% of SMEs specifically cite regulatory and administrative hurdles as major barriers.[122] These burdens arise from the cumulative effect of harmonized rules across sectors, often requiring national transposition, which amplifies complexity and enforcement costs without commensurate benefits in proportionality. SMEs, comprising 99% of EU businesses and employing two-thirds of the workforce, face amplified impacts due to their limited resources for compliance, where regulatory costs can exceed return on investment and average annual gross wages in some industrial sectors.[123][124] This red tape stifles innovation and competitiveness, as evidenced by SMEs in manufacturing, agriculture, and hospitality reporting frustration over time-intensive obligations that divert resources from core operations.[125] Over-regulation favors larger firms or non-EU competitors unencumbered by similar mandates, contributing to Europe's lagging productivity growth compared to the US and Asia.[126] Specific regulations exemplify this burden: the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CS3D, Directive (EU) 2024/1760) imposes novel cross-border administrative requirements, exacerbating adjustment costs; the European Green Deal's cascade of rules has intensified sustainability reporting without sufficient simplification; and digital laws like the AI Act have elevated overall regulatory density rather than streamlining divergences.[122][127][128] Business associations argue that such measures, while pursuing policy goals, often lack rigorous impact assessments, leading to unintended economic drag that undermines the single market's efficiency. Despite EU commitments to reduce burdens by 25% for companies and 35% for SMEs, implementation has lagged, with new mandates offsetting gains.[129]Erosion of National Sovereignty

The supremacy of EU law, including regulations, over conflicting national provisions forms a cornerstone of the Union's legal order, as established by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) and enshrined in primary law, compelling member states to disapply domestic rules that hinder EU regulatory objectives.[62] [130] This principle, rooted in the 1964 Costa v ENEL judgment and reaffirmed in subsequent rulings, enables EU regulations—directly applicable under Article 288 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU)—to override national legislation without requiring transposition, thereby curtailing member states' capacity to pursue divergent regulatory paths in harmonized fields such as the single market, environment, and data protection.[62] In practice, this has manifested in over 1,000 infringement procedures annually against member states for regulatory non-compliance, with the European Commission acting as enforcer to impose uniformity.[131] Recent challenges underscore tensions, as national constitutional courts have contested the unconditional primacy of EU law when it encroaches on core sovereignty attributes like judicial independence. In 2021, Poland's Constitutional Tribunal ruled that EU institutions exceed competences where national constitutional identity is at stake, prompting CJEU countermeasures and daily fines of €1 million on Poland for judicial reforms deemed incompatible with EU regulatory enforcement mechanisms.[132] [133] Similarly, Germany's Federal Constitutional Court in 2020 invalidated CJEU approval of the European Central Bank's public sector purchase program on procedural grounds, highlighting limits to supranational regulatory overreach in fiscal matters intertwined with national budgetary sovereignty.[134] These disputes reveal empirical pressures on governments, where EU compliance demands have empirically reduced policy space, as evidenced by econometric analyses showing constrained fiscal and regulatory autonomy post-2008 crisis.[135] In regulatory domains, harmonization mandates erode national tailoring, exemplified by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which since 2018 has preempted member states from adopting substantially divergent data rules, imposing uniform extraterritorial standards that override looser national frameworks and expose firms to fines up to 4% of global turnover for non-adherence.[84] This one-size-fits-all approach ignores variances in national risk tolerances and enforcement capacities, fostering criticisms that it stifles innovation in smaller economies while benefiting larger actors with compliance resources.[136] The 2020 Rule of Law Conditionality Regulation further weaponizes EU budget allocations—totaling €1.2 trillion in 2021-2027 cohesion funds—by conditioning disbursements on alignment with EU regulatory standards in areas like judicial oversight, leading to €20 billion withheld from Hungary by 2024 for perceived backsliding that impeded uniform application of EU law.[137] Such mechanisms, while aimed at upholding the regulatory state's integrity, empirically compel policy convergence, diminishing member states' leverage to experiment with deregulation or prioritize domestic priorities amid heterogeneous economic conditions.[135]Economic Drawbacks and Innovation Constraints

The European Union's regulatory framework has been criticized for imposing substantial economic costs, particularly through compliance burdens that disproportionately affect small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which constitute over 99% of EU businesses and employ around two-thirds of the workforce. According to a 2025 BusinessEurope analysis, more than 60% of EU companies view regulation as an obstacle to investment, with 55% of SMEs specifically citing administrative burdens and regulatory obstacles as major impediments to growth and expansion. These costs manifest in direct expenses for legal advice, documentation, and audits, as well as indirect opportunity costs from diverted management time; for instance, the cumulative administrative burden from EU laws has been estimated to reduce SME competitiveness by increasing operational overheads that larger firms can more easily absorb. Between 2019 and 2024, the EU adopted approximately 13,000 new regulations, exacerbating this accumulation without sufficient sunset clauses or periodic reviews to eliminate redundancies.[122][138] Former Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi's 2024 report on European competitiveness highlights how ongoing regulatory accretion undermines economic dynamism, noting that while the EU professes support for innovation, it imposes burdens—such as fragmented sustainability reporting and due diligence requirements—that are especially onerous for scaling firms and startups. Draghi argues that these layers of rules fragment the single market and deter risk-taking, contributing to Europe's lag in high-value sectors; empirical evidence from the report links excessive regulation to subdued productivity growth, with EU GDP per capita trailing the US by about 30% in purchasing power parity terms since the early 2000s, partly attributable to regulatory-induced inefficiencies rather than solely fiscal or demographic factors. SMEs, lacking the resources for in-house compliance teams, often face compliance costs equivalent to 4-10% of turnover in regulated sectors like chemicals and digital services, per sector-specific studies, which stifles hiring and capital investment.[139][139][140] On innovation, EU regulations constrain technological advancement by prioritizing precautionary principles over experimentation, leading to a shallower venture capital ecosystem compared to the US, where VC investment in Europe averaged roughly one-third of US levels from 2015-2023 despite comparable population sizes. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), implemented in 2018, exemplifies this: a 2022 study found it reduced profits for EU-exposed firms by an average of 8.1%, with SMEs bearing the brunt due to heightened data handling costs that limit access to training datasets for AI and machine learning models. Post-GDPR, European ad tech revenues declined by up to 12% in affected markets, as smaller innovators struggled to compete with data-rich incumbents, while overall EU patent filings in digital technologies grew 20% slower than in the US over the same period. Similarly, the EU AI Act (effective 2024) introduces risk-based classifications requiring extensive conformity assessments, which critics contend will delay market entry for AI startups by 18-24 months and raise development costs by 10-20%, fostering a "Brussels effect" that exports caution but hampers endogenous breakthroughs.[141][142][143] This regulatory stringency contributes to Europe's "middle-technology trap," where firms specialize in incremental improvements rather than disruptive inventions, as evidenced by the EU's underrepresentation in global tech unicorns—only about 20% versus the US's 50% share as of 2024. A 2015 CEPS analysis of EU legislation found that while some directives spur eco-innovation through clear standards, many—particularly in chemicals (REACH) and biotech—reduce R&D incentives by extending approval timelines to 10-15 years and inflating costs to €100-300 million per product, diverting resources from frontier research. In contrast, lighter-touch US frameworks have enabled faster scaling in sectors like biotech, where FDA approvals average 7-10 years, correlating with higher EU-US innovation gaps in AI and semiconductors. These constraints risk entrenching dependency on non-EU tech imports, as Draghi warns, with regulatory predictability favoring compliance over agility and perpetuating a cycle of subdued entrepreneurship.[144][145][139]Recent Developments

Post-Brexit Adjustments and Third-Country Relations

Following the United Kingdom's departure from the European Union on 31 January 2020 and the end of the transition period on 31 December 2020, the UK transitioned to third-country status, necessitating adjustments in the EU's regulatory framework to govern bilateral relations. The EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA), signed on 30 December 2020 and entering into force on 1 May 2021, established a framework for tariff-free trade in goods subject to rules of origin compliance, while excluding regulatory alignment in services and investment.[146] [147] This agreement incorporated provisions for a "level playing field" to prevent unfair competition through state aid, subsidies, and labor or environmental standards, with mechanisms for consultation and dispute resolution, though enforcement relies on retaliatory measures rather than automatic alignment.[148] In regulatory domains such as data protection, the European Commission granted the UK adequacy decisions under the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and Law Enforcement Directive on 28 June 2021, allowing personal data flows without additional safeguards until their expiry on 27 June 2025.[149] These decisions were subject to periodic reviews, with the Commission proposing renewal on 23 July 2025 amid concerns over the UK's Data Protection and Digital Information Bill, which introduced divergences like a new adequacy test for third-country transfers potentially lowering safeguards.[149] [150] The European Data Protection Board (EDPB) issued opinions on 19 October 2025 recommending scrutiny of these changes to ensure ongoing equivalence, highlighting risks from UK immigration rules permitting bulk data access by authorities.[150] Financial services regulations saw limited equivalence grants; the EU deferred decisions on UK clearing houses and trading venues post-TCA, leading to the UK's relocation of euro-denominated activities to the EU and ongoing divergences in prudential rules.[151] By 2025, UK regulatory reforms, including revocations of retained EU law by the Bank of England on 30 April 2025, accelerated divergence, prompting EU assessments of competitive distortions.[152] Discussions for a "reset" in EU-UK ties, as outlined in a November 2024 Bruegel policy brief, emphasized enhanced regulatory cooperation in sectors like chemicals and veterinary standards to reduce non-tariff barriers without rejoining the single market.[153] Brexit amplified the EU's emphasis on third-country regulatory frameworks, treating the UK as a precedent for managing access to the single market. The EU maintains adequacy decisions for data protection with 14 non-EU jurisdictions as of 2025, including recent adoptions for the European Patent Organisation on 15 July 2025, based on assessments of enforceable protections equivalent to EU standards.[154] [155] These decisions facilitate trade but remain revocable, as evidenced by the invalidation of prior EU-US arrangements and their replacement with the EU-US Data Privacy Framework in 2023.[156] For broader sectors, the EU employs equivalence regimes in finance and equivalence determinations in capital markets, requiring third countries to mirror EU rules for market access, with post-Brexit UK experience underscoring the EU's reluctance to grant permanent equivalence without convergence commitments.[157] This approach has influenced EU trade agreements, embedding data protection clauses to enforce safeguards absent adequacy, thereby conditioning third-country participation on alignment with EU norms.[158]2020s Reforms in Digital Sovereignty and Competitiveness

In response to geopolitical tensions, supply chain disruptions from the COVID-19 pandemic, and perceived dominance by U.S. and Chinese technology firms, the European Union advanced a series of legislative measures in the 2020s to assert greater control over digital infrastructure, data flows, and emerging technologies while aiming to level the playing field for European businesses. These reforms, framed under the broader Digital Decade 2030 strategy, sought to achieve targets such as universal gigabit connectivity, advanced digital skills for 80% of the population, and the emergence of 10% of large European digital platforms among global top players by 2030, with an emphasis on reducing reliance on non-EU providers for cloud computing and semiconductors.[159] The strategy prioritized "technological sovereignty" through investments in domestic capabilities, though empirical assessments of its impact remain preliminary given the recency of implementations.[160] The Digital Markets Act (DMA), adopted on September 14, 2022, and entering into force on November 1, 2022, targeted "gatekeeper" platforms—defined by thresholds like €7.5 billion in annual EU turnover and 45 million monthly active users—to promote contestability and fairness. It prohibits practices such as self-preferencing in search results or app stores and mandates data portability and interoperability, with the European Commission designating six core gatekeepers (Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, ByteDance, Meta, Microsoft) by September 2023 and enforcing compliance probes starting in March 2024.[161] [92] Complementing this, the Digital Services Act (DSA), also adopted in 2022, imposed transparency and accountability on online intermediaries to mitigate risks from illegal content and disinformation, indirectly supporting sovereignty by empowering EU oversight of global platforms.[162] To address artificial intelligence, the EU AI Act, the world's first horizontal AI regulation, entered into force on August 1, 2024, classifying systems by risk levels: prohibited uses (e.g., social scoring by governments) apply immediately, while high-risk AI in sectors like hiring requires conformity assessments, transparency for general-purpose models (e.g., watermarking deepfakes), and governance by a new EU AI Office. With phased applicability—full rules for high-risk systems by August 2027—the Act aims to foster "trustworthy AI" as a competitive edge, backed by €1 billion in Horizon Europe funding, though it imposes compliance costs estimated at €6-10 billion annually for regulated entities.[163] [164] Hardware independence drove the European Chips Act, proposed in February 2022 and formalized in 2023, which mobilizes over €43 billion in public and private funds through 2030 to elevate the EU's global semiconductor market share to 20% from 9% in 2020, via the €11.15 billion Chips for Europe Initiative focused on R&D, pilot lines, and a Chips Fund for startups. This responds to vulnerabilities like the 2021 chip shortage, which cost the EU auto sector €110 billion, by incentivizing fabs (e.g., Intel's €33 billion German plant) and design capabilities.[165] [166] The Data Act (Regulation 2023/2854), entering into force January 11, 2024, and applicable from September 12, 2025, extends GDPR principles to industrial data by mandating user access to data from connected devices (e.g., smart appliances) and fair sharing terms with third parties, including public sector access during emergencies. Its goals include unlocking €270 billion in annual value from data markets by stimulating competition in cloud services and IoT, where EU firms hold under 5% share, while switching providers without lock-in to counter hyperscaler dominance.[167] [168] These measures collectively aim to build resilient ecosystems, but their net effect on competitiveness hinges on balancing regulation with innovation, as over-reliance on ex-ante rules could disadvantage smaller EU players against agile non-EU rivals.[160]Ongoing Debates on Deregulation (2024-2025)