Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Early Caliphate navy

View on Wikipedia

| Caliphate navy | |

|---|---|

ar-rāyat as-sawdāʾ black standard which used by the early Quraish tribe and the Rashidun caliphate as war standard[1] | |

| Active | 638–750 |

| Allegiance | Rashidun Caliphate, Umayyad caliphate,[2] early Abbasid Caliphate |

| Type | Naval force |

| Size | 200–1,800 ships[3][4][5][6][7] |

| Ports | |

| Nickname | Caliphate navy[11] |

| Engagements |

|

This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: intro section bad english in parts. (October 2024) |

The Arab Empire maintained and expanded a wide trade network across parts of Asia, Africa and Europe. This helped establish the Arab Empire (including the Rashidun, Umayyad, Abbasid Caliphates and also Fatimids) as the world's leading economic power throughout the 8th–13th centuries according to the political scientist John M. Hobson.[13] It is commonly believed that Mu‘awiya Ibn Abi Sufyan was the first planner and establisher of the Islamic navy.

The early caliphate naval conquest managed to mark long time legacy of Islamic maritime enterprises from the Conquest of Cyprus, the famous Battle of the Masts[14] up to of their successor states such as the area Transoxiana from area located in between the Jihun River(Oxus/Amu Darya) and Syr Darya, to Sindh (present day Pakistan), by Umayyad,[15] naval cove of "Saracen privateers" in La Garde-Freinet by Cordoban Emirate,[16] and the Sack of Rome by the Aghlabids in later era.[17][18][19]

Historian Eric E. Greek grouped Rashidun military constitution with their immediate successor states from the Umayyad until at least Abbasid caliphate era, along with their client emirates, as single entity, in accordance of Fred Donner criteria of functional states.[20] This grouping were particularly apply to the naval forces of the caliphate as a whole.[21] Meanwhile, Blankinship does not regard the transition of rule from Rashidun to Umayyad as the end of the military institution of the early caliphate, including its naval elements .[22] This remains at least until the end of the rule of the 10th Umayyad caliph, Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik, as Jihad as religious and political main motive for the military of 'early Jihad state' which spans from Rashidun caliphate until Hisham were still regarded by Blankinship as the same construct.[23]

Historical background

[edit]The history of Arabian Peninsula navigation was recorded at least from 2,000 years BC,[24] to even as far as the era of Sargon of Akkad (r. c. 2334-2284 BCE), when shipping industry in Magan, in present-day Oman are mentioned.[25][26] The Belitung ship is the oldest discovered Arabic ship to reach the Asian sea, dating back over 1,000 years.[27] Gus van Beek noted that all scholars accepted the south Arabians were engaged in early maritime trade on the Indian Ocean to the Arabian sea.[28] Gus van Beek also theorized the scheduling of the Arabo Indian naval trade were similar with modern era, which is usually done during southwest monsoon.[28] Hojjatollah Hezariyan concludes that the maritime trade activity on the Persian Gulf as indication of the earliest human navigation in history.[29]

Pre-Islamic Arabian maritime history

[edit]The pre-Islamic Arabian navigation and sea trade prospered on the beaches of Yemen, Hadhramaut, Oman, Yemen, and Hejaz, It was long contested by various powers in an attempt to control the sea trade.[29] According to Watt, the Quraish "were prosperous merchants who had obtained something similar to a trade monopoly between the Indian Ocean and East Africa on the one hand and the Mediterranean on the other.[30] Aside from a trade hub for goods arriving on the caravans from Yemen Syria, Mecca was also trading goods, arriving from merchant ships from Abyssinia at the port of Shaybah near Jeddah.[31][32]

The south Arabian navigation history were suggested by Gus van Beek that they are developed through their constant contacts with advanced maritime civilization.[28] According to biblical historiographical research by Charles Henry Stanley Davis, a semitic maritime civilization named Phoenicia which dated from 1100 and 200 BC had for a long time planted colonies of merchants in Yemen.[33] The prosperity of Gerrhan caused the Yemen and the Phoenician to open an Indian trade route for commerce.[34] The Phoenician colonies in Yemen has shipped merchant vessels came from India unloaded their cargoes in Yemen coasts and carried them across the Arabian desert to their hometown in Levant.[33] The Phoenician merchants also settled in Persian gulf in their effort of transporting commodities from India to their hometown.[35] Thus the trade activities between the local Yemenites and the Phoenician has formed a prosper ancient Arab kingdom, Gerrha.[34] The commodities which were brought by the Phoenician from Yemen and the Persian gulf were transported using Arabian caravans that crossed the desert towards Levant.[35]

During the second century 2nd century B.C, The Arabs, particularly the Azd branch who lived in east and south of Arabia,[36] were recorded has already dominated the seaborne enterprises between the Red Sea and India,[37] or even the 8th century BCE.[38][32] This historical tradition serves as the background after the advent of Islam for Muslim warriors, preachers, merchants and travelers to navigate not only in the Southern Mediterranean, the Red Sea, and parts of African Atlantic, but also the vast Indian Ocean.[16] The Arabs controlled also controlled the commerce from "Ezana" (the East African coast north of Somalia) to Indonesia,[39] and Sri Lanka to Oman, as Chinese explorer in 414, Faxian reported he met some Arab merchats in Sri Lanka,[40] the Euphrates past al-Hirah.[41] Later in the middle of the 6th century CE, one of the seven pre-Islamic poets, Tarafa bin al-'Abd, mentioned the water passage of khaliya safin in the sea. According to Arab chroniclers, khaliya safin were 'great ships', or 'ships that travel without seamen to make them move'. These monopoly once contested by the Greeks, who tried to challenge Arab control of maritime trade between India and Egypt during the early Middle Ages. However, they persisted as the Greek naval trade dwindled.[42] Biblical historiography also mentioned such Arabian mercantilism as Quran mentions trade with Sheba.[43] The Old Testament, while Book of Ezekiel mentioned Arabia and princes of Kedar trading lambs, rams, goats, and other materials.[44]

Later in the third century AD, inscription from Hadramaut has recorded the existence of 47 ships in the port of Qāni' has shown the strength of the Himyarite navy,[45] While in the late sixth century, the southern Arabia were caught in the naval campaign that involved Sasanian Empire and the Aksumite Empire in a conflict series over control of the Himyarite Kingdom in Yemen, Southern Arabia. After the Battle of Hadhramaut and the Siege of Sana'a in 570, where according to Tabari, the undermanned Yemeni-Sasanian alliance won a "miraculous" victory,[46] and the Aksumites were expelled from the Arabian peninsula.[47][48][49] The naval influence from Sasanid during that conflict prospered and continued until the emergence of Islam.[50]

Meanwhile, the eastern Arab also recorded naval activity, as during the rule of Shapur II, the Sassanid forces were recorded to be engaged in naval conflict with Arab pirates which operated within Persian Gulf, where their incursions have reached as far as Gor.[51][52] After the era of Shapur II, a coastal settlement of migratory independent Azd Arab in Qalhat are recorded for their pride for their ancestors long time resistances against Sassanid Empire.[53] However, there is report the Sasanian influences in Dibba, Sohar, and other ports within coastal Arabic kingdom of Julandi dynasty in the 5th-6th AD. At one uncertain location, Sasanian military of at has placed 4,000 troops to guard the coastal trade routes of the Sassanids.[54][55] While Bahrain island also experienced a strong garrison of Sassanid[54]Asawira patrolling their island in Darin port[55] Hojjatollah Hezariyan gave the outline of Oman political situation as for the first three centuries AD, coastal areas of Oman were practically divided between the Azd Arabs and the Sassanian Empire.[29]

History of caliphate navy

[edit]

During the lifetime of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, there were limited maritime activities such as the military expedition of Alqammah ibn Mujazziz.[56][57] When 'Alqamah bin Mujazziz Al-Mudlaji dispatched with 300 men to fight against some men from the Kingdom of Aksum, who gathered near the shores of Jeddah as they approached Mecca.[58][59] Abd and Jayfar from the Oman coast had previously cut ties with the Sassanid Empire, and swore loyalty to Muhammad,[8] while Bahraini Al-Ala al-Hadhrami also gave his loyalty, by sending a tribute of 80,000 Dirham to Muhammad.[54]

Ridda wars

[edit]After the death of Muhammad, Abu Bakr was unanimously accepted as head of the Muslim as Caliph. Troubles emerged soon afterwards, as Apostasy spread across the Arabian Peninsula with the exception of the people in Mecca, Medina, Ta'if and the Bani Abdul Qais of Oman.[60] This resulted in the long pacification campaigns of the Ridda wars. During the campaign, Abu Bakar secured support from Abd Al-Juland and his brother Jayfar, Azd Arab rulers of large harbors of coastal Oman.[54] Then the Julandi siblings gave an ultimatum to the Sassanid elements within their kingdom to submit to Islam. The Sassanid garrisons refused and so were expelled from the coasts as a result, thus giving the newborn caliphate vast coastal ports on eastern Arabia.[54] The Sassanid navy were pushed by the Muslim forces in eastern Arabia who pursued them overseas even as far as Dastagird.[54] The Sassanids that were encased in Dastagird then sued for peace and paid a ransom, so the Muslim forces pursuing them agreed to leave and return home.[54] Meanwhile, in the Arab kingdom of Bahrain, situation were also in favour of Rashidun caliphate as Al-Ala al-Hadhrami, the ruler of the kingdom who has pledged allegiance to the caliphate along with Arfajah, al-Ala general and the first Muslim Arab naval commander according Mahmoud Sheet Khattab.[61]

Red Sea and Persia

[edit]

In the year 12 AH (633 AD), Arfajah led further naval operations and conquered a large number of islands in the Gulf of Oman.[62] Ahmed Cevdet Pasha, who narrated from the text of Al-Waqidi, pointed out that Arfajah had no trouble raising an army and ships which needed to mount this naval invasion without the support of central caliphate, due to his notably wealthiness and powerful influence of followers from within his clan. Ahmed Jawdat further narrated that the background of Arfajah naval expedition from Al-Waqidi's book that Arfajah were filled by impetuous Jihad motivation as he launched the expedition without the permission of Umar, boarded the ships and marched for the conquest in the Sea of Oman.[63] However, Cevdet Pasha mistook as he though this campaign occurred during Umar caliphate, while in reality it is occurred during the caliphate of Abu Bakr.[64] Tabari narrated that as caliph Abu Bakar learned that Arfajah had acted without his consent, he immediately dismissed Arfajah from the navy command.[65] Later during the era of Umar, Naval activity of the caliphate continued as 'Alqama crossed the Red Sea toward Abyssinia with permission from Umar. The expedition was disastrous, and only a few ships returned safely to their home port. This accident probably became the reason of the reluctance of 'Umar Ibn al-Khattab to embark such naval adventures again for most time of his reign.[66] Meanwhile, in Bahrain, there constant naval raids by Persians.[67] Arfajah, who just conquered the town of Sawad immediately called back to Bahrain to reinforce al-Ala.[68]

|

| Caliph Umar praise Arfajah in his letter to Utbah ibn Ghazwan.[69] |

In the end of the year 13 AH (634 AD), al Ala ibn Hadhrami commanded Arfajah to start sending ships and boats for further maritime expedition,[70] as they are ordered by caliph Umar to detach himself from Al-Muthanna ibn Haritha while they are in Hirah.[71] This time, Arfajah, under al Ala, were attacking the island of Darin (Qatif) to exterminate the feeling apostate rebels who flee from mainland of Arabian peninsula toward that island.[72] Arfajah led the first Arab-Islamic naval campaign in history against Arab rebels on their own place in the final battle in Island of Darin (Qatif) and Juwathah.[73] The caliphate mariners also facing Persian Sassanid forces in Darin, as contrary to the Sassanian marines in Yemen of the Abna under Fayruz al-Daylami who pledge their allegiance to Abu Bakar and worked harmoniously with the Arabians in Yemen to quell the rebellion, the Sassanid mariners counterparts in Oman and Bahraini refused to submit to the caliphate.[74] In the final battle of Darin island in the fortress of Zarah, the caliphate mariners has finally subdued the final resistance after Arfajah soldier named Al-Bara' ibn Malik manage to kill the Persian Marzban commander, and managed to seize the wealth of the said commander of 30,000 coins after the battle.[75][76][Notes 1] However, caliph 'Umar saw that it was too much for single person to acquire spoils of war that huge, so the Caliph decided that al-Bara' should be given a fifth of that spoils instead of whole.[75][Notes 2]

After the island were subdued, Arfajah, under instruction from al Ala, started to sending ships towards Sassanid coast in Port of Tarout of the island. This continued Until Arfajah reached the port of Borazjan, where according to Ibn Sa'd Arfajah sunk many Persian navy ships in this battle,[78] Shuaib Al Arna'ut and al-Arqsoussi recorded the words of Al-Dhahabi regarding Arfaja naval campaign during this occasion: "...Arfaja sent to the coast of Persia, destroying many (enemy) ships, and conquered the island and built mosque..".[79]

It is said by historians this Arfajah operations in the coast of Persian Gulf secured the water ways for Muslims army and paving the way for the later Muslim conquest of Pars.[80] Ibn Balkhi wrote that Arfajah write his progress to al Ala, who in turn inform to 'Umar.[81] This satisfy 'Umar, who in turn instructed al Ala to further resupply Arfajah who still continued fighting off coast,[82] which Arfajah responds continued the naval campaigns the mainland of Fars.[83] The coastal incursions commenced by Arfajah spans from Jazireh-ye Shif to an Island,[84] which identified by Ahmad ibn Mājid as Lavan Island Then continued to until they reached Kharg Island.[85] Poursharianti recorded this second Arfajah naval adventure were ended with the annexation of Kharg, in month of Safar, 14 AH.[86]

However, this time caliph 'Umar disliked Arfajah unnecessarily dragged sea adventures, as the naval forces of Arfajah were originally dispatched to support Utbah ibn Ghazwan to conquer Ubulla.[83] Shortly, 'Umar instructed to dismiss Arfajah from his command and reassign al-Ala ibn Hadrami as his replacement.[83] although, Donnes said in his version that al-Ala died before he could assume the position.[83] regardless the versions, the caliph then later instructed Arfajah to bring 700 soldiers from Bahrain to immediately reinforce Utbah who is marching towards Al-Ubulla.[87] Arfajah manage to rendezvous with Utbah later in the location that will become a Basra city, and together they besiege Ubulla until they managed to capture the port city.[88]

Independent campaign in Pars

[edit]During the undergoing campaigns against Persian Sassanid, Al-Ala al-Hadhrami organised his mariners for another naval expedition in to three corps to attack Fars without consent from the caliph. They departed Bahrain by ship and travelled across the Persian Gulf to present day Iran that started raiding Persepolis.[89] The three corp commanders were:

- al-Jarud ibn Mu’alla

- al-Sawwar ibn Hammam

- Khulayd ibn al-Mundhir ibn Sawa

The first two corps were defeated, while Khulayd were cut off from their ships by the Persians leaving the army trapped in Fars. 'Umar angrily wrote to the governor of Basra, 'Utbah bin Ghazwan and said, Al-Ala' has commenced naval operation without his approval, while also sending reinforcements to rescue the ill-fated mariners of Al-Ala' who trapped inside enemy territory.[90]

In response, Utbah sent an army of 12,000 fighters, that were led by Asim ibn Amr al-Tamimi, Arfajah bin Harthama, Ahnaf ibn Qais, and Abu Sabrah bin Abi Rahm.[91][92] In this rescue operation, Arfajah advised Utbah on a strategy to send the forces of Abu Sabrah alone to the coastal area, in order to bait the Sassanid forces while they hid their main forces beyond the sight of the enemy and even the isolated Muslim forces that they intend to rescue. Then as Sassanid army saw Abu Sabrah came with only few soldiers, they immediately gave chase as they though it is the whole Muslim reinforcement soldiers. At this certain moment, Utbah commence Arfajah final plan to commit his main forces to flank the unexpected Sassanid force, causing heavy casualties on them and routing them, thus this operation of relieving the Muslim mariners which had been posed to danger of being isolated in the Persian soil succeeded.[93][94]

Umar then dismissed Al-Alaa as governor of Bahrain and appointed him to govern Basra.[95] The governor of Ta'if, Uthman ibn Abu-al-Aas appointed to manage military affair in Bahrain and Oman in 638 in the aftermath of this disastrous naval operation by Al -Ala against the Sasanian province of Fars.[96] Ibn Abu al-Aas immediately consolidated mariner forces from the port of Julfar(now Emirate of Ras Al Khaimah) then began his assault against Fars Sasanian until he subdued Bishapur in 643, [97] before continued sustained naval assault in littoral Iran which preceded the campaign in coastal Hind which only ended decade later about 650 when Sassanid power in Fars crumbled.[98]

Coastal campaign of Hind

[edit]The campaign in Hind managed to draw the area Transoxiana from area located in between the Jihun River(Oxus/Amu Darya) and Syr Darya, to Sindh (present day Pakistan).[15] Then Ibn Abu al-Aas dispatched naval expeditions against the remaining ports and positions Sassanids.[12] This naval operation immediately conflicted Hindu kingdoms of Kapisa-Gandhara in modern-day Afghanistan, Zabulistan and Sindh.[99][100] As Ibn al-Aas delegate the expeditions against Thane and Bharuch toward his brother, Hakam. Another sibling named al-Mughira were given the command to invade Debal.[101] Al-Baladhuri states they were victorious at Debal and Thane, and the Arabs returning to Oman without incurring any fatalities.[102] The raids were launched in late 636c. 636.[103][104] The contemporary Armenian historian Sebeos confirms these Arab raids against the Sasanian littoral.[12] However, this naval operations were launched without Umar's sanction and he disapproved of them upon learning of the operations.[100]

Nevertheless, they continued pushing as in 639 or 640, Ibn Abu-al-Aas and al-Hakam once again captured and garrisoned Arab troops in the Fars town of Tawwaj near the Persian Gulf coast, southwest of modern Shiraz. while delegate the affair of Bahrain to al-Mughira.[105][12] In 641 Ibn al-Aas established his permanent fortress at Tawwaj.[105] From Tawwaj in the same year, he captured the city of Reishahr and killed the Sasanian governor of Fars, Shahruk.[105] By 642 Ibn Abu-al-Aas subjugated the cities of Jarreh, Kazerun and al-Nubindjan.[105] until they reached "The Frontier of Al Hind", where now they engaged the first land battle against a ruler of an Indian kingdom named Rutbil, King of Zabulistan.[106] in the Battle of Rasil in 644 AD.[107][108][109] According to Baloch, the reasons Uthman ibn Abi al-'As launch this campaign without caliph consent were possibly zeal-driven adventures for the cause of jihad (holy struggle).[110] Meanwhile, George Malagaris opined this expedition have limited aim to protect the sea trade of caliphate from pirates attack.[111]

Nevertheless, this naval campaign towards Hind immediately terminated the moment Uthman ibn al-Affan ascended as caliph, as he immediately instructed the incumbent commanders of the expedition towards Makran, al-Hakam and Abdallah ibn Mu'ammar at-Tamimi, to cease their campaign and withdraw their position from river in Hind.[112]

Mediterranean campaign

[edit]

After the death of Umar, Uthman succeeded him as caliph. During the first half of his reign. the Rashidun army continued the conquests of Africa, Syria, and Persia further, while also began coastal raids in 652.[113]At this point, Rashidun caliphate reached the Sasanian eastern frontiers extended up to the lower Indus River. One of the first naval project from caliph Uthman were sending instruction to Abdallah ibn Mu'ammar at-Tamimi, the frontline commander of Rashidun army and fleet who has reached Makran to cancel his advance and retreat until the back of the river of Hind.[114]

First Cyprus conquest

[edit]

In 648 AD, Mu'awiya convinced the caliph that a new navy had to be established in order to confront the Byzantine naval threat. So he recruited Ubadah ibn al-Samit, along with some veteran companions of Muhammad such as Miqdad Ibn al-Aswad, Abu Dhar GhiFari, Shadaad ibn Aws, Khalid bin Zayd al-Ansari, and Abu Ayyub al-Ansari to participate in building the first Muslim standing Navy in Mediterrania that was to be led by Mu'awiya. Later Ubadah also joined Abdallah ibn Qais to build the first batch of the ships in Acre.[115]

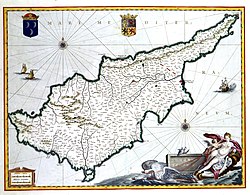

Mu'awiya and Ubadah departed from Acre and brought the massive fleet of 1,700 ships to Cyprus, as they reinforced by Abdallah ibn Sa'd who joined them from Alexandria.[116][117] Muawiya and Abdallah ibn Sa'd forces pacified almost every Byzantine garrison.[118][119] The entire island of Cyprus surrendered for the first time after their capital, Salamis was besieged for an unspecified time.[118] Later the Cypriots agreed to pay 7,200 gold coins Jizya annually.[117] In a different narrative the raid was instead conducted by Mu'awiya's admiral Abd Allah ibn Qays, who landed at Salamis before occupying the island.[120] In either case, the Cypriots were forced to pay a tribute.[120][121]

Asia Minor and Ruad Island

[edit]After Cyprus was pacified, Abdullah ibn Qais, one of the caliphate admirals continued his cruise in the Mediterranean Sea in the vicinity of Cyprus.[31] Ibn Qais is accredited with having fought fifty naval battles presumably along coasts of Asia Minor all of which was victorious.[118][119] In all these battles, not a single Muslim was killed or drowned.[31] Because of these victories the exploits of Abdullah ibn Qais became legendary. He was known as the sea warrior of Islam and won great bounty, even enjoying popularity among the common men of the enemy.[31][118] When the conquest of the island was reported to Uthman, he felt satisfied with the result of the first naval expedition. That made Uthman feel that the fears of Umar about naval warfare were unfounded.[118]

In 649, Caliphate mariners from the Island of Cyprus began infesting Ruad island (now known as Arwad) that is located off the coast of the city of Tartus. Junada ibn Abi Umayyah ad Dawsi brought four thousand men to invade Ruad using twenty boats, and a Greek guide who has been promised safety for him and his family as well as payment in treasure, in return for his assistance.[122] When they approached the island, the guide ordered them to anchor in the sea of the coast.[122] As the Muslim mariners approached Ruad garrison, fighting immediately erupted and all of the Byzantines soldiers were either killed or having fled, took shelter in houses.[122] With the spoils to Mu'awiya, Mu'awiya took out a fifth of it and sent it to Medina, and what was left, he divided among the Muslims.[122]

Second conquest of Cyprus

[edit]

In 652, Cyprus rebelled against the caliphate.[31][118] In response, Mu'awiya returned on an armada of 500 ships.[123][118] This time Mu'awiyah and al-Samit split their forces into two: one led by Mu'awiyah and the other by Abdallah ibn Sa'd.[118] However Umm Haram, wife of Ubadah ibn al-Samit accidentally fell when she was riding a mule as the ships landed at a spot two hours distant from Larnaca, broke her neck and was buried at that spot. The place where her tomb is now Hala Sultan Tekke mosque was built nearby her burial location.[31]

This punitive campaign was described in Tarikh fi Asr al-Khulafa ar-Rashidin as particularly brutal as many died in the campaign and many men from the Cyprus forces were taken captive.[118] Lapethos was heavily damaged, while the population often had to flee and take refuge in the interior,[124] and the Arabs plundered the island, built a fortified city with a mosque, and left a garrison of 12,000 men.[31] After they pacified Cyprus for the second time, Mu'awiya tasked Ubadah to manage the spoils of war. Mu'awiya also transferred portions of Muslim settlers from Baklabak, Syria, to Cyprus while also constructing mosques to help Islamization on the Island.[118] Mu'awiya ibn Hudayj of the Kinda tribe remained on the island for several years.[125]

Battle of the Masts & Sicily

[edit]Later, in the same year, an invasion commanded by either Abd Allah ibn Abi Sarh, or Mu'awiya's lieutenant Abu al-A'war captured most of the island.[14] Olympius, the Byzantine exarch of Ravenna, came to Sicily to oust the invaders but failed.[126] According to Michael the Syrian, shortly after this, in 653/654, Abu al-A'war commanded an expedition against Kos, which was captured and plundered due to the treason of the local bishop.[127] He proceeded to pillage Crete and Rhodes.[128] Rhodes was occupied by the naval forces of Caliph Mu'awiya I in 654, who carried off the remains of the Colossus of Rhodes.[129][130] The island was again captured by the Arabs in 673 as part of their first attack on Constantinople. When their fleet was destroyed by Greek fire before Constantinople and by storms on its return trip, however, the Umayyads evacuated their troops in 679/80 as part of the Byzantine–Umayyad peace treaty.[131]

Later in the same year, the caliphate launched the most successful military operation in the famous Battle of the Masts, or Battle of Dhat al-Shawary. The Byzantine fleet commanded by Emperor Constans II was forced to sail to Sicily to intercept the Muslim fleet.[14] Shortly before the naval battle of Phoenix, two brothers belonging to a Christian family from the Syrian port of Tripoli, after having committed serious sabotage in the Muslim fleet, escaped and joined the Byzantines .[4] Due to this serious sabotage, the caliphate arrived in the battle outnumbered by a margin of nearly 1 to 3 ships,[4] Ibn Khaldun giving number the Byzantine brought 600 ships.[132]

Waqidi reported the Byzantines drew their ships into tight formation.[31] First hand witness, Malik ibn Aws ibn al-Hadathaan, who was one of the naval officers present at the battle, narrates that the Sea wind blew unfavorably against the Muslim positions, which forced them to drop their anchors. As the wind stopped, the Muslim soldiers taunted the Byzantines to conduct the battle on land, which the Byzantine refused.[133] In response, the Muslims lashed their ships together in closed formation. 'Abdallah ibn Sa'd formed the Muslims in ranks along the sides of the ships and began ordering them ready in battle station while reciting the Qur'an.[31] As the Byzantine soldiers closed on their ships, the Muslims fought them in close combat in a bitter fight that lasted until the tide turned and that resulted in the Byzantine forces being repelled.[31] On one occasion, The Byzantine ships tried to drag and capture Abdullah ibn Sa'd command ship by tying their ships together with Ibn Sa'd command ship and trying to drag it away .[134] However, a brave marine named 'Ilqimah ibn Yazeed al-Ghutayfi sacrificed himself by jumping on the ropes and cutting them, saving Abdullah ibn Sa'd and his command ship.[134]

Byzantine casualties were massive and emperor himself just narrowly escaped from the slaughter.[31] This battle was so catastrophic for the Byzantines despite their numerical superiority, that Theophanes called it "The Yarmuk at the sea".[135]

Later in the year of 44 AH (664-665 AD), Mu'awiya ibn Hudayj launched a sudden attack towards island of Sicily.[136] Ibn Hudayj brought two hundred ships during this invasion which was prepared by his superior, Mu'awiyah.[137] Ibn Hudayj managed to seized massive spoils of war from this campaign, when he returned to Levant in 645 AD.[137] According to Al-Baladhuri, he invaded the island of Sicily on the authority of Mu'awiyah ibn Abi Sufyan, and the first Muslim commander to infest the island.[138] After the first invasion, Ibn Hudayj continued to raid the island routinely for the rest of the Muslim conquest.[139]

Isles of Hispania

[edit]Tabari reported that after the conquest of northern Africa was completed,[140] Abdullah ibn Sa'd continued to Spain. Spain had first been invaded some sixty years earlier during the caliphate of Uthman. Other prominent Muslim historians, like Ibn Kathir,[141] quoted the same narration. In the description of this campaign, two of Abdullah ibn Saad's generals, Abdullah ibn Nafi ibn Husain, and Abdullah ibn Nafi' ibn Abdul Qais, were ordered to invade the coastal areas of Spain by sea as they succeeded in conquering the coastal areas of Al-Andalus. The expedition did conquer some portions of Spain during the caliphate of Uthman, presumably establishing colonies on its coast. On this occasion, Uthman is reported to have addressed a letter to the invading force:

Constantinople will be conquered from the side of Al-Andalus. Thus if you conquer it you will have the honour of taking the first step towards the conquest of Constantinople. You will have your reward in this behalf both in this world and the next.[141]

According to the account of al-Tabari, when North Africa had been duly conquered by Abdullah ibn Sa'd, two of his generals, Abdullah ibn Nafi ibn Husain, and Abdullah ibn Nafi' ibn Abdul Qais, were commissioned to invade the coastal areas of Spain by sea.[141]

Later, Mu'awiyah captured Rhodes, which was seen as a major loss to the Byzantines as it was important trade route. The pacification of Rhodes was mounted by Junada ibn Abi Umayya al-Azdi who according to early Muslim sources, oversaw the naval raids against the Byzantine Empire during the governorship of Syria by Mu'awiyah. However, their activity were halted during the First Muslim Civil War (656–661).[142]

Umayyad era

[edit]

Some historians treated Rashidun armed forces, navy included, as single entity with their successors armed forces.[143][11][144] Historian Eric E. Greek remarked The immediate successor of Rashidun caliphate, Umayyad, were quickly absorbed state institution mechanism of the former.[143] By this fact, Greek grouped military constitution of Rashidun with later successor caliphates along with their emirate clients as one entity. Greek based this grouping on Fred Donner's criteria of functional states,[20] While Khalilieh noted the successor caliphates and emirates technically inherited the naval rights of Rashidun mariners.[11] Furthermore, researchers of Tahkim(political arbitration) and Suluh(political reconciliation) of Islamic jurisprudence theory generally agreed reconciliation between Hasan ibn Ali with Mu'awiya were lawful in accordance of Islamic jurists, as Khakimov theorized that the ascension of Mu'awiya are viewed as a legal transfer of power in the scope of caliphal institution, not a coup change of regime.[145]

Junada ibn Abi Umayya, ex-Rashidun naval commander who now served the Umayyad navy, resumed his raids,[146] as at least one raid led by Junada against the Byzantines in Rhodes in the period of 672/73–679/80.[147][148][149] Later, Junada leading two more naval campaigns against Rhodes in 678/79 and 679/80.[150] Tabari recorded Junada established a permanent Arab garrison in Rhodes, but the colony was frequently harassed by Byzantine ships which caused him to evacuate the colony.[147] Although, another Rashidun general that continued to serve Umayyad caliphate, Abu al-A'war remained on the island with 12,000 garrison soldiers until the peace treaty of 680, following the failure of the First Arab Siege of Constantinople. Abu al-A'war seems to have commanded this garrison for some time, since the 10th-century Byzantine emperor Constantine VII records that Abu al-A'war erected a tomb for his daughter, who died there, which survived to Constantine's day.[127] Aside from Rhodes, Junada also invaded Crete, and unnamed island in Sea of Marmara.[151]

Conquest of India

[edit]

Al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf, the governor of the 'Superprovince' of Iraq, sent his nephew, the 15 year old Muhammad ibn Qasim together with a naval force that departed from the port of Basra. The force consisted of 6,000 Syrian horsemen, 6,000 camel troops with 3,000 Bactrian camel to carry supplies, and also five large Manjaniq (catapult) engines named 'Uroos' (literal name 'The Bride') which required 500 men to operate them. Ibn Qasim successfully subdued the port of Debal, the port of Armabil (now Bela, Balochistan) and the port of Debal, after he joined with nearby Arab garrison land forces on the area, which rendezvoused with the Ibn Qasim naval force on the same day in Debal.[152] Since the era of the Rashidun caliphate of Umar, the Muslim naval forces aimed to control the coastal areas of Balochistan as it is invaluable for sea patrol within the Arabian gulf to Indian sea lane.[153]

After conquering Brahmanabad in Sindh, Ibn Qasim co-opted the local Brahman elite, whom he held in esteem, re-appointing them to posts held under the Brahman dynasty and offering honours and awards to their religious leaders and scholars.[154] Following his success in Sindh, Muhammad bin Qasim wrote to 'the kings of Hind' calling upon them to surrender and accept the faith of Islam.[155] Ibn Qasim then sent a cavalry of 10,000 to Kanauj, along with a decree from the Caliph. He himself went with an army to the prevailing frontier of Kashmir called panj-māhīyāt (in west Punjab).[156] Later, Ibn Qasim was recalled in 715 CE and died en route. Al-Baladhuri writes that, upon his departure, the kings of al-Hind had come back to their kingdoms. The period of Caliph Umar II (r. 717–720) was relatively peaceful. Umar invited the kings of "al-Hind" to convert to Islam and become his subjects, in return for which they would continue to remain kings. Hullishah of Sindh and other kings accepted the offer and adopted Arab names.[157] During the caliphates of Yazid II (r. 720–724) and Hisham (r. 724–743), the expansion policy was resumed. Junayd ibn Abd al-Rahman al-Murri (or Al Junayd) was appointed the governor of Sindh in 723 CE.

After subduing Sindh, Junayd sent campaigns to various parts of India. The justification was that these parts had previously paid tribute to Bin Qasim but then stopped. The first target was al-Kiraj (possibly Kangra valley), whose conquest effectively put an end to the kingdom, and the prompting land forces invasion of the caliphate,[158] although the outcome were not recorded.[159] Khalid Yahya Blankinship states that this was a full-scale invasion carried out with the intent of founding a new province of the Caliphate.[160] in 725, the caliphate forces fortified the ports of Mansura and Mahfuza which bordering Indus as Ribat town where the caliphate navy sent forth the naval raids.[89]

In 726 CE, the Caliphate replaced Al-Junayd by Tamim ibn Zaid al-Utbi as the governor of Sindh. During the next few years, all of the gains made by Junayd were lost, as according to Blankinship the possibility that the Indians must have revolted, or the problems were internal to the Arab forces.[161] After Tamim died, Al-Hakam restored order to Sindh and Kutch and built secure fortifications at Al-Mahfuzah and Al-Mansur. He then proceeded to retake Indian kingdoms previously conquered by Al-Junayd. The Arab sources are silent on the details of the campaigns. However, several Indian sources record victories over the Arab forces.[162] Indications are that Al-Hakam ibn Awana was overstretched. An appeal for reinforcements from the Caliphate in 737 is recorded, with 600 men being sent, a surprisingly small contingent. Even this force was absorbed in its passage through Iraq for quelling a local rebellion.[163] The death of Al-Hakam effectively ended the Arab presence to the east of Sindh. In the following years, the Arabs were preoccupied with controlling Sindh. They made occasional raids to the seaports of Kathiawar to protect their trading routes but did not venture inland into Indian kingdoms. These coastal incursions by al-Hakam which done in the areas which conquered by al-Junayd years ago were the last known Umayyad presence in Sind.[164]

Conquest of north Africa littorals & Iberia

[edit]The conquest of the Hispania area of the Iberian Peninsula which started during the era of caliph Uthman was resumed in the era of Umayyad under al-Walid I (Walid ibn Abd al-Malik). The commanders of the conquest were Tariq ibn-Ziyad and Musa bin Nusair in 711–712. At first, Musa Ibn Nasir was given the governorate of Ifriqiya, succeeding Hassan Ibn al-Nu`man in 78 AH (697 AD).[165][166] Musa started his career in Africa by quickly pacifying the rebellions of Berber remnants across northern Africa in the same year.[165] Although Ibn Idhari reported the campaign had ended in 86 AH (705).[167] During his tenure in Africa, Musa was known to be able to win the crowd of his Berbers subject in Africa and make sure they did not rebel against the caliphate[168] As the Byzantines resorted to sea invasions after losing their land battles, Musa proceeded to build an Arsenal (Dar al-Sina) near the ruins of Cartagena, to build a powerful fleet to protect the frontiers. In the year 89 AH (708 AD), Musa directed his son Abdullah to invade the Balearic Islands, and subdue Mallorca and Menorca.[169] Musa also mounted naval raids towards Sardinia and Sicily,[170] which returned with huge prize of war from each raids.[171] Then Musa in turn also conquered Tangier.[172] The expedition to conquer Sardinia began in 89 AH/707-708 AD. led by Atha ibn Rafi'. It was next led by 'Abd Allah ibn Murra who directed Musa ibn Nusayr. The latter brought back as many as 3,000 prisoners and considerable spoils in gold and silver.[173]

In 709 AD, Musa ibn Nusayr began to invade the Iberia.[174] Tariq ibn Ziyad, one of Berber Mawla of Musa, were credited for leading an army of 4.000 cavalry and 8.000 infantry defeated 100.000 visigoth army in the Battle of Guadalete as soon after he landed on Iberian peninsula[175] The Umayyad hosts of Andalusia, which in line with their successor of Emirate of Córdoba, has employed stitched war ships that harbored across the ports of Algeciras, Almuñécar, Pechina (Almeria Vera), Cartagena, Elche, Alicante, Port of modern-day Santa Maria, Qasr Abi Danish, Lisbon and Sagra[10] In the year 93 AH/ 710 AD Musa recaptured Sardinia although his fleet was destroyed on the way back, while about five decades later, on 135 AH/752-753 AD, the governor of Africa, 'Abd al-Rahman ibn Habib had prepared as well as possible to conquer both Sicily and Sardinia.[173]

Later, up to the farthest west, the Umayyad naval activity reached as far as the famed "pirate" cove beachheads at La Garde-Freinet in Southern France, were greatly feared. In one instance, the Muslim privateers once captured the Abbot of Cluny until ransomed by a hoard of ecclesiastical silver.[176]

Siege of Constantinople

[edit]Nevertheless, the caliphate reached it high tide of as al-Mas'udi and the account of Theophanes mentioned for the Siege of Constantinople has fielded an army led by Sulaiman ibn Mu'adh al-Antaki large as 1,800 ships with 120,000 troops, and siege engines and incendiary materials (naphtha) stockpiled. The supply train alone is said to have numbered 12,000 men, 6,000 camels and 6,000 donkeys, while 13th-century historian Bar Hebraeus, the troops included 30,000 volunteers(mutawa) for the Holy War (jihad).[5] [6][7]

Organization and sea routes

[edit]

The nature of the Ports, Sea route, and Armada of eastern Caliphate fleet were characterized by the Arabic trade route which existed before Islam, particularly the eastern route.[177]

There are some of earlier ports in Yemen that requisited by Islamic caliphate earlier before the conquest started:

- Aden, the port city of Yemen where the Sasanian governor, Badhan, converted to Islam and defected to the caliphate.[178] According to Agius, the blockade of Aden port by rulers of Kish Island during 1165 has seriously disrupted the trade line between Mediterranea and Indian sea. [179]

- Qanī(now Bi'r 'Ali), Harbor in Yemen which enabled trade route directly to India without needing to stop and resupply.[180]

- Mocha, A port city in the red sea.

Nevertheless, for the next decades the caliphate acquired more important sea ports such as Bahrain, Oman, Hadramaut, Yemen, and Hejaz themselves were situated on the shores of the Red Sea, the Indian Ocean, and Arabian Gulf, which suitable for maritime trades. Muslims' ships returning from India docked on the Yemen's coasts.[177] These ways are indeed the gateway for caliphate maritime contact to the far east Asia, such as India, China.[177] Baladhuri, Tabari, Dinawari, and Buzurg reported that Chinese ships were common sight in Ubulla.[181]

The route has reached even as far as Java island, when from Mu'awiya and caliph Umar ibn Abdul Aziz has reached the kingdom of Srivijaya. Mu'awiya, who at that time engaged in cordial and friendly letter with the king Sri Indravarman whom possibly had acquired Zanj slave as a gift from the caliphate.[182] Another sovereign in the Java island which have correspondece with Mu'awiya was Queen Sima from the Kingdom of Kalingga, as the delegations from the caliphate engaged in the missions of tradings and also for Islamic Da'wah in the area. the correspondence between the Caliph with the Queen were still preserved until today in Spanish museum in Granada[183] In 2020, there is convention from local Qur'an academic institution in north Sumatra that show an Umayyad coin artifact found in Tebing Tinggi province dated from 79 AH.[184] According to Indonesian historians seminar which organized by Aceh provincial government,[185] Hamka, and Reuben Levy, This contact happened during the reign of Mu'awiyah as caliph, where queen Shima regards Mu'awiyah as king of Ta-cheh in regards of Arab caliphate.[186] Both Hamka,[187] and Levy though that the envoys of Umayyad managed to reach Kalingga kingdom due to the improvements of caliphate maritime navigation, as Mu'awiyah were focusing the Caliphate navy at that time.[186] Levy also gave figure that the fleet of Umayyad envoys which reached Kalingga has 5,000 ships in number.[188]

These ports and trading routes, including those in the Red sea and Mediterranean sea has recorded to contain the caliphate Armada:

| Western Armada | 1st Cyprus(648–650) | 2nd Cyprus(652) | Phoenix(654) | Sicily(664–665) | Iberian Invasion(712–715) | Siege of Constantinople(717-718) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eastern Armada | 1st Expansion to India(711–712) | ||||||

| Ships | 1,700[116][117] | 500[123][118] | 200[3][4] | 200[189] | 1,800[5][6][7] | ||

| Crews | 12,000 Soldiers[118] | 12,000 soldiers(4,000 cavalry; 8,000 infantry)[176] | 12,000 soldiers(6,000 Horse Cavalry & infantry; 6,000 Camel cavalry)[190] | 30,000-120,000 Soldiers; 12,000 Logistic convoy(12,000 men; 6,000 camels; 6,000 donkeys)[5][6][7] | |||

| Siege engines | 5 'Arus Manjaniq( a type of gigantic Catapult require 500 personnels to operate one of it)[190] | unknown numbers of variouse siege engines, Greek Fire/Nafta throwing catapult engines[5][6][7][191] |

Eastern sea Armada

[edit]

The Islamic expansions in the East and the West were not destructive, Muslim authorities not only preserved all dockyards, naval bases, and systems in the former Byzantine and Persian provinces.[192] It is due to this soft policy toward the subjugated settlements, the naval influence from Sassanid and Pagan Azd Arabs were continued before the emergence of Islam,[50] were came to caliphate possession intact.[192] This were evidenced that the Sasanid forces came to supplant the Aksumite viceroys in Yemen.[48][49]

According to Hojjatollah, One of the key features of Arabian gulf was the gulf provided navigation and shipping all year with ports of the Persian Gulf, such as al-Ubullah, Siraf, Hormuz, and Kish, lying around the gulf.[29] Hojjatollah further adds, that The Muslims invasion of Sindh may as an economic necessity, while also translate as pretext for the invasion.[29] While Seyyed Suleiman Nadavi believes that the first Muslim invasions of Tan, Bruch and Dibel Bana had aimed for economic necessities.[29]

This trends were supported by harbours on the Arabian gulf and Persia that came to caliphate possession, such as:

- Al-Ubulla/Apologus(Charax Spasinu), A harbour belonged to Sassanid situated near Charax Spasini and the River Euphrates which served as replacement of Rishar port that situated south of Al-Ubulla .[193] Al-Ubulla were notable due to the city linens and shipbuilding production.[194] The Charax mint appears to have continued through the Sassanid Empire and into the Umayyad Empire, minting coin as late as AD 715.[195] Al-Ubulla port had long time enjoyed strategic position as important centre for caravan-routes that came from the north of Mesopotamia, Mediterranean and Indian route.[196] Consequently, Ubulla in the Arab Gulf and flooded the middle east with commodities such as camphor water, teak wood, high quality Indian sword,[196] bamboo and others. During the early Muslim conquests in the 630s, Al-Ubulla was conquered by the Arab forces of Utbah ibn Ghazwan in two separate occasions by[197][198] In a letter attributed to Utbah he describes the city as "hub for al-Bahrayn (eastern Arabia), Uman, al-Hind (India) and al-Tsin (China)".,[194] At least until the Mongol invasion.[194]

- Bahrain Island, an Azd Arabian maritime settlement within Arabian Gulf which ruled by Al-Ala'a Al-Hadrami.[199][200] The Bahrain region ruled by al-Ala'a with Munzir ibn Sawa Al Tamimi jointly, and both converted to Islam with entire populace.[201][202] Bahrain proved as povital naval launchpad for the caliphate conquest toward Persian and Sindh.

- Basra, Founded by Utba ibn Ghazwan and Arfajah, caliphate first admiral.[203] At first, Arfajah built seven complexes of Garrison which fitted 700 soldiers[203] However, the city port grow fast as Baladhuri estimates that around 636 AD, the number of caliphate regular soldiers in Basra totalled 80.000 Muqatilla (regular soldier)[Notes 3]. In Umayyad time, Basra has become a launchpad for caliphate navy led by Muhammad ibn Qasim which consisted 12,000 soldiers, 6,000 one humped camels, 3,000 two humped camels, and gigantic siege engines that need 500 crews to operate.[152]

- Dibba, large natural harbor on the east coast of the northern Emirates has been an important site of maritime trade and settlement for millennia, with relatively recent excavations underpinning the importance of the town as a site of entrepot trade throughout the Iron Age and into the late pre-Islamic era.[205][60] The Oman rulers of the 6th century, Abd and Jaifar Julandi has converted to Islam and supported the caliphate in Battle of Dibba[8]

- Debal, ancient founded in the 1st century CE, which was the most important trading city in Sindh. The port city was home to thousands of Sindhi sailors including the Bawarij. Ibn Hawqal, a 10th-century writer, geographer and chronicler, mentions huts of the city and the dry arid land surrounding the city that supported little agriculture. He mentions how efficiently the inhabitants of the city maintained fishing vessels and trade. The Abbasids were the first to build large stone structures including a city wall and a citadel. An earthquake in 893 AD reportedly destroyed the port city of Debal.[206] Debal became sea route used by Arabs to reach the Indian subcontinent ran from "The Euphrates of Maysan" to on the Indus River.[207]

- Julfar (in the area of today's Ras Al Khaimah) was an important port that was used as a staging post for the Islamic invasion of the Sasanian Empire.[208] During the caliphate of Abd al-Malik (65–86/685–705) it was a strategic harbour, a key to the control of Oman through the desert. Julfar was known for fishing and was a trading center which served the tribal families in the desert and mountains.

- Makran(Balochi/Persian: مكران), a semi-desert coastal strip in Sindh. first captured by Uthman ibn Abu al-Aas, and his brother Hakam ibn Abu al-Aas to raid and reconnoitre the Makran region.[209] In mid-644 the Battle of Rasil was fought here. Later it governed by the Habbari tribe after it stabilized by the conquest of Muhammad ibn Qasim during Umayyad era.

- Mansura and Mahfuza ports in Sindh bordering Indus which fortified as Ribat town for naval raids against the local kingdoms of Sindh.[89]

- Muscat, an independent Azd Arabian settlement located in Oman which retained their independence from Sassanid Empire[210][53][211] and was nicknamed as Cryptus Portus (the Hidden Port) by Ptolemy

- Muska(Samharam/Khor Rori).[212]

- Qalhat, an important stop in the wider Indian Ocean trade network, and was an Azd Oman coastal settlement which said where the Omani Arabs ancestors defeated the Sasanian forces in the battle of Salut. After the caliphate era, it became the second city of the kingdom of Ormus.[53]

- Rishar, a port located further south of the Al-Ubulla there is an important sea port connected the Sri-Lanka.[196] More importantly, evidence to suggest that from sasanian times, trade route for the Arabs, from the al-Ubulla has connected Indian Ocean to Mediterranean west west through the Silk road by the Euphrates river[49][213] Rishar port once housed a strong Sassanid navy which tasked to end piracy and encouraged pearl-fishing and trade.[196]

- Sohar, largest town in Oman region, it has been argued that Suhar is identified with the ancient town called 'Omanah'(Arabic: عُمَانَة)[214]

It is reported the pre-Islamic Seafaring Azd Arabian mariners[36][49] and Sasanian naval elements[215] were reportedly still strong and dominant force on those harbors, before being absorbed to the Islamic caliphate.[215][216] After the Muslim conquest of Persia, Historian David Nicolle pointed there are indication the naval war machines and crews of those harbors were absorbed by caliphate navy. This claim were attested by the Chinese source Old Book of Tang, Guangzhou was ravaged and burned by the mariners of the Arabs and the Persians in 758.[217]

Between 708 and 712 the army which departed from Shiraz under Qasim consisted of 6,000 Syrian heavy cavalry and detachments of mawali (sing. mawla; non-Arab, Muslim freedmen) from Iraq.[218] the borders of Sindh he was joined by an advance guard and 6,000 camel cavalry and later, reinforcements from the governor of Makran were transferred directly to Debal (Daybul), at the mouth of the Indus, by sea along with five manjaniks(catapults).[219] The manjaniq named al-Arus, which was. especially built at the order of Caliph al-Walid for this expedition, was so huge that 500 men used to operate it.[190]

Western Armada

[edit]

Similar to the eastern theater, the shipyards and harbours of Syrian coasts were mostly relative intact due to relatively peaceful conquests of the caliphate.[192] Mu'awiya initiated the Arab naval campaigns against the Byzantines in the eastern Mediterranean,[220] requisitioning the harbors within Syrian coasts.[221][120] Not only absorbing them, the caliphate also founded new maritime installations—arsenals and naval centers—along their maritime possessions in,[192] as Mu'awiya moved and ordered Caliphate engineer crews from eastern theater (Azd Omani Arabs according to Hossain[222] while Hourani said they are Persian engineers that has been subdued by the caliphate[223]) to repair existing ships, which seems abandoned after Battle of Yarmouk,[223][224] since commanders of Jund al Sham that involved early land campaign veterans such as Mu'awiyah ibn Abi Sufyan, Ubadah ibn al-Samit, Sufyan ibn 'Awf, Abdullah ibn Qays, Uthman ibn Abi al-As, Abdullah ibn, Sa'd, Busr ibn Abi Artat, and others, were aware of the strategic importance of the coastal frontiers of their territories along the Mediterranean.[225] The following harbours and port cities acquired by the Muslims are:

- Acre (Arabic: عكّا, ʻAkkā), Following the defeat of the Byzantine army of Heraclius by the Rashidun army of Khalid ibn al-Walid in the Battle of Yarmouk, and the capitulation of the Christian city of Jerusalem to the Caliph Umar, Acre came under the rule of the Rashidun Caliphate beginning in 638[226]

- Ayla (Arabic: آيلا). coastal settlement in Gulf of Aqaba, Sinai Peninsula, which fallen to Islamic armies by 650, and the ancient settlement was left to decay, while a new Arab city was established outside its walls under Uthman ibn Affan,[227] known as Ayla (Arabic: آيلا).

- Antioch and its port, Seleucia Pieria, was conquered by the Rashidun Caliphate during the Battle of the Iron Bridge. The city became known in Arabic as أنطاكية Anṭākiyah.

- Ashkelon (Philistine: 𐤀𐤔𐤒𐤋𐤍 *ʾAšqālān), also known as Ascalon (Arabic: عَسْقَلَان, ʿAsqalān), a coastal city within Syrian coast

- Beirut (Arabic: بيروت, romanized: ⓘ), port city conquered by the Muslims in 635.[228]

- Cyprus Island, an important island which served as satellite naval base for eastern Mediterranean sea. Consistently garrisoned with 12.000 soldiers from the time of Rashidun to early Umayyad

- Jaffa, served as a port of Ramla, then the provincial capital. Al-Muqaddasi (c. 945/946 – 991) described Yafah as "lying on the sea, is but a small town, although the emporium of Palestine and the port of Ar Ramlah. It is protected by a strong wall with iron gates, and the sea-gates also are of iron. The mosque is pleasant to the eye, and overlooks the sea. The harbour is excellent". [229]

- Jeddah Largely civilian port city. the third Muslim Caliph, Uthman Ibn Affan, turned it into a port making it the port of Makkah instead of Al Shoaib port southwest of Mecca.[230] Based on records of Ibn Rushd, Prior to 'Alqamah disaster against Aksum pirates that Caliph Umar already ordered Amr ibn al As to manage naval enterprises to transport corns and wheats from Egypt to Medina to relieve the famine in 639.[231] The Caliph reported to personally receive first twenty ship heavy laden with cargo from Egypt. al Maqdisi report there are no less than 3.000 camel loads of maize exported this way in a single shipping season.[232] To safeguard this enterprise, later caliphs also maintained regular naval patrols on the red sea.[233]

- Latakia, a harbour along the coastal area of Syria, Laodicea fell into Muslim rule after its attacked Ubadah ibn al-Samit during the Muslim conquest of Syria. The city was renamed al-Lādhiqīyah(اللَّاذِقِيَّة) and switched rule from the Rashidun Caliphate[234] .Arab geographer, Al-Muqaddasi (d. 991), mentions al-Lādhiqīyah as belonging to the district of Hims (Homs).[235]

- Roda Island, (al-Rawḋa[9]), an ancient fortress in the Nile Delta, located in the area known today as Coptic Cairo, near Fustat.[9] Following the Byzantine fleet raid against the coastal town of Barallus(Burullus[236]) in 53/672–3,[9] The Byzantines raids on the outpost of Burullus from the island of Roda, and seized most of the ships of the Arab soldiers.[237] this prompting Maslama ibn Mukhallad al-Ansari, Rashidun governor and general in Egypt, to start the project of building Egyptian naval fleet by establishing Arsenal#Etymology, or warship manufacturing dock on the island in the year 54 AH / 674 AD, where the Copts played vital role maintaining the fleet.[237][9] This military port has survived the span of Tulunid, Ikhshidid, Fatimid, Ayyubid, up until Mamluk era.[9] During the Abbasid era, under governance of Ahmad ibn Tulun, this port alone was guarded by at least 100 military ships.[9]

- Ruad Island port which Mu'awiya repopulated these coastal towns with a large number of Persians residing in Baalbek, where they had previously been sent by their country .[238] The Persians were tasked to build ships which were used to invade Cyprus island.[224]

- Tyre Arabic: صور, romanized: Ṣūr; In the late 640s, the caliph's governor Mu'awiya launched his naval invasions of Cyprus from Tyre.[239]

- Tunis, captured by the caliphate from Byzantine North Africa. (known in Arabic as Ifriqiya), and in c. 700, Tunis was founded and quickly became a major Muslim naval base. This not only exposed the Byzantine-ruled islands of Sicily and Sardinia, and the coasts of the Western Mediterranean to recurrent Muslim raids, but allowed the Muslims to Invade and conquer most of Visigothic Spain from 711 on.[240][241]

- Alexandria, important port town in Egypt which was captured by Amr ibn al-Aas. Following the death of Amr in 664, Utba was appointed governor of Egypt and he strengthened the Muslim Arab presence and elevated the political status of Alexandria by attaching 12,000 Arab troops to the city and constructing a Dar al-Imara (governor's palace).[242] Hourani mentioned that Alexandria as complete naval base which harbor capacious shipyards and Coptic skilled craftsmen. As Egypt lacked timbers and woods, Hourani theorized this had to be brought from the ports of Syria, such as Acre and Tyre.[223]

By requisitioning these Naval centres for military purpose, Mu'awiya rationale was that the Byzantine-held island posed a threat to Arab positions along the Syrian coast and it could be easily neutralized,[119] In addition to those coastal harbors, Umayyad caliphate also later housing ports in vast coastal area of Iberia Andalusia:

- Algeciras[10]

- Almuñécar[10]

- Pechina (Almeria)[10]

- Vera[10]

- Cartagena[10]

- Elche[10]

- Alicante[10]

- Port of modern-day Santa Maria[10]

- Qasr Abi Danish[10]

- Lisbon[10]

- Sagra [10]

Crews

[edit]The commanders of the caliphate naval forces were called Amir al Bahriyya,[192] while the mariner crews called Ahl al-Bahr[243]

For the Mediterranean armada, the crews of were at least divided into three components:

- Administrators & fighting forces, mainly consisted of Hejazi Arabs(Quraysh & Qaysi of western, central, and northern Arabs) holding Command staff and main combat units.[31] The Arabs were already known as amazing navigators as they used to navigate through the desert plains by use of the stars as they know method used at that time for navigating across the seas such as compass reading, star altitude measurement, knowledge of the relation to winds, tides, currents, and navigable season.[244][24] Administrative tasks of the Arab overseers includes the manage of the foreign populace due to the Arabs also known for expertize of language translators which helped the caliphate to coordinate the subdued populations.[31] Meanwhile, the combat tasks were also fallen upon them as the Arabs already known for their excellent fighting skills within the conquest duration, along with their superior disciplines and high morale. They transferred their landfighting ability for naval combat sea as the early generation of Arab Muslims also known as master swimmers.[31] Beside, the Muslims holds the instruction from caliph that should not the newly subdued and convert populace to hold such vital roles.[31]

- Engineers & shipbuilders, mainly consisted Omani and Yemeni Arabs(Southern & Eastern Azd Arabs[222]) were transported from the east to help building fleets in Syria. David Nicolle highlighted these eastern engineer crews were brought to the caliphate new naval bases in Palestine for their expertise for engineering and craftmanships.[224] This particularly helpful after the second conquest of Cyprus, Mu'awiyah expelled large portions of rebellious Cypriot Greeks. Unlike their brethren in Hijaz,[245] These Arabs were traditionally skilled mariners who already navigated the far easts of Indian sea for long time.[246] notable naval commander hailing from this branch were Arfajah, who led the first caliphate naval invasion against Sassanid coasts in Fars province.[247] Meanwhile, according to Hourani, the engineers of early caliphate navy were consisted of Persian stocks from Sassanid Empire, who were just subdued by the Rashidun caliphate in the conquest of the east.[223]

- Ship operators, mainly consisted of Egyptian Copts operated the ships; unlike the treacherous Cypriot Greeks, the Copts enjoyed warm relations with Muslims from the early days would have led to them training the Muslim soldiers and advising the Amirs on naval affairs.[31] Ibn khaldun recorded when government authority of Arab established firmly in certain area, they employed populace for their nautical expertize operating the ships.[248] The Copts are quite voluntary as caliph Uthman stressed there should not be conscription to be forced for naval enterprise,[249] While the Copts are known to despise the Byzantines and welcomed the Muslims rule in Egypt.[31] Amr ibn al-Aas, commander of Muslim conquest in Egypt, were recorded to invoked the common ancestry between Arabs and Egyptians through Hagar, mother of Ishmael, to gained sympathy of the newly subdued Egyptian populace.[250][251][252]

To contain those personnels, Amir al Bahr erected coastal defense garrison(Ribat) in all of their coastal area to defend the territory from enemy naval threats. Khalilieh theorized There were three types of Ribat instituted in the early Muslim caliphate:

- Ribāṭ towns, a fortified towns surrounded by watchtowers, often with inner forts, and garrisoned with cavalry troops to defend the coast from hostile raids.[225]

- military fortress. This included Sousse and Monastir in Tunisia, and Azdūd, Māḥūz Yubnā and Kafr Lām in Palestine. These fortresses, generally situated outside the town limits, in front of it and facing the enemy. These fortresses were consisted of round watchtowers at the corners and two semicircular towers protecting the main gate. The courtyards were surrounded by arms and food warehouses, stables for cattle and horses, larger and smaller rooms, as well as Mushalla for prayer.[225]

- military lookout tower. contain by at least five horsemens equipped with defensive and deterrent arms. Arsuf is thought to be one of the seven Ribats that protected the capital Ramla until the Crusader conquest.[225]

Lighthouses or also established during the time of Umayyad caliphs.[253] The caliphate coastal watchtowers are called Mihras.[254] Archeological excavations discovered that Mihras was square buildings with one preserved floor strengthened by eight buttresses, with two of them in each corners.[254] the general dimension of Mihrases were approximately 18.3 feet with each wall about 22.5 by 3.66 feet.[254] These Mihrases were dated about 13 AH(634 AD)-439 AH(1099 AD)Lighthouses or also established during the time of Umayyad caliphs.[253]

Strategy, equipment and combat

[edit]The naval warfare of early caliphates are described such as started with arrow skirmishes which followed with stone projectiles throwing, Then as the projectiles runs out, Some Muslim marines then jumped in the water and tied the ships together creating one large land mass on the sea as chained hooks used to tied Muslim ships to Byzantine ships,[134] Followed with, as Hourani mentions, close combat were favored by the Arab Muslim warriors who excelled in such warfare.[255]

Regarding heavy engines, the Rashidun caliphate and early Umayyads has used such catapults, mangonels, battering rams, ladders, grappling irons, and hooks for both sieges warfare and naval warfare.[256][134]

Navigational technology

[edit]Christides said that the maritime technology of Arabs are influenced by Greeks which they learned independently and Indo-Persian Red sea Nautical technology.[257] There are twelve that constitute the medieval Principles of Navigation which supposedly understood by Arab Muslims during the caliphate time, that contains the distances between ports due east and west, rhumbs of the compass, star altitude calculations, knowledge of the seasons and climates which pivotal for sea navigation, instruments of the ships, and ethical relations between the crew and passengers.[258]

Ships

[edit]The Muslim military vessels could reached as far as Tarsus from Jazirat al-Rawda.[259] Hourani mentions the wood materials were imported from Syria for the Copts built new ships.[260] During the conquest of Cyprus, Muslim ships were operated by Omani and Yemeni Azd Arabs, who are very skillful mariners[36] Modern Historians such as Agius and Hourani theorized Arab ships were similar enough to Byzantine warships such as Dromon.[261] The warships in both Mediterranean and Iberia armada of Spain have their planks nailed and their body stitched to protect the ships from salt water.[10] Tarek M. Muhammad argued were two or three big masts in the dromon-shīni seems to be correct only for the later period but the forecastle was between two masts were valid if the other masts were only supplementary. The dromon-shīni was equipped with a main castle(ξυλόκαστρον) as Superstructure, where a small number of fighters were placed, and a supplementary structure on the prow, stored the main weapons, incendiary "bombs", "fire pots", terracotta bottles filled with the same liquid launched with catapults, that can rain down a thousand meters around the ship. Rather than flame throwing siphon (machinery for launching liquid or Greek fire) ships like Byzantine.[262]

However, others such as Taylor and Dmitriev argued the caliphate disliked the Byzantine ship structure design and instead preferring huge Persian ships which can load huge siege engines and cavalry.[263][264][265] Taylor argued that the Arabs though Byzantine small ships did not work well for eastern theater of campaigns, as according to al-Jahiz, in the last decade of the 7th century CE, al-Hajjaj ibn Yusuf ath-Thaqafi, Tyrannical viceroy of Iraq, experimented to introduce flat-bottomed, nailed ships of Mediterranean style to the waters of the Arabian Gulf, which were failed at the end.[265] Furthermore, George Hourani implied this eastern influence from Persia in his book, Arab Sea crafting, amongst the port of Azd Arab in Oman,[29] which evidenced by Fars-Nama report that the sinking of two ships from Iranian fleet during their journey from al-Ubulla to Yemen.[29]

The huge carrier ships which caliphate favored are called khaliya safin(meaning "the great ship"[265]) by the Arabs.[265] one of earliest mentions about Khaliya safin were found in the poetry of Jarir, an Umayyad Poet.[266] The Umayyad poets described as "its like a fortress floating on the water and its mast are like the trunk of a palm tree".[266] Such ship was so great that during the invasion of Muhammad ibn Qasim to India, the ships which sent by Governor of Makran to reinforce him can load Manjaniq Arus, a gigantic catapult engine that was said to need 500 men to operate.[267] Dmitriev theorized the huge carrier ships the Arabs used for the conquests of Mediterranea like Khaliya Safin were likely inherited from Persians engineers design,[264] which are originally designed by the Persians so it could load cavalry troops, as Sasanian army were cavalry based.[263] However, Khaliya Safin carrier ship are already used by the Arabs even before the Islamic conquest,[42] While the Arabs who lived in Yemen and Oman also already knew nautical technology for long time, just like the Persians[36] According to Agius, the Safin ships were an "Ocean-going ships which operated from 600 to 625 CE.[268]

Another type of ship were Harraqa or 'fire ship',[261] which is the type most often equipped with Greek fire or Nafta based incendiary weapons. Agius theorized this ship were a ship that containing catapults which throwing fire ball rather than flame throwing ships like Byzantine.[261] George Hourani mentioned how Abdullah ibn Qais Al-Fazaari used to hurl flames at the enemy for naval battles during his undefeated 50 operations against Byzantine coasts, before the Battle of the Masts.[255] This was implied by Sebeos records that Mu'awiyah's fleet which was led by Bisr ibn abi Artha'ah were carrying unspecified artillery engines that can throw "balls of Greek fire" during the siege of Constantinople.[269][191] Another records of such incendiary 'ship-killing' weapons usage by the Muslims are come from the Viking raid on Seville, as the Emirate ships used an incendiary liquid thrown by catapults, to burn the invaders' ships,[270][270] which claims also came from Dionisius A. Agius.[271] Ibn Khatib recorded that Ismail I of Granada used an engine which worked with nafta.[272] which supported by Tabari reports regarding alat al-naft siege engine naft which shooting petrol(naft) or flaming rocks.[273]

Agius also added these siege carrying ships were carrying dabbaba (armoured [wooden] tanks)[274] According to Agius, these Harraqa ships which are river fit, were used to manoeuvre around enemy ships to assist larger ships,[271] while aside the incendiaries and artillery, the Harraqa ships also manned by archers as additional firepower.[271]

Another feature of naval warfare during the early caliphate era were the chained hooks used to grapple and drag the enemy ships from their original position.[134]

However, one of the most fearsome weapon used by caliphate navy were a giant trebuchet named 'Arus' that used by Muhammad ibn Qasim when he besieged the port of Debal in India.[275] It is said One of these machine required a force of 500 men to work its mechanism for discharging stone missile from its platform. the Arus stone missiles destroying the dome and the flag mast inside Debal and causing the port city defender terrified and lose heart, which immediately surrender to Ibn Qasim.[275]

Religious and political context

[edit]

The famous hadith regarding the prophecy and praise for naval expeditions sea narrated by Umm Haram widely considered to be one of the main driving force for early Muslim Arabs for the Jihad campaign on sea for later eras, particularly the conquest of Cyprus, which done by both Umm Haram and her husband, Ubadah, under the command of Mu'awiya,[31] while Allen Fromherz quoting verse: Your Lord is He Who drives the ship for you through the sea, in order that you may seek of His bounty. Truly, He is ever Most Merciful towards you.[276] for the implication of the motive of seaborne Jihad.[16]

One day the prophet Muhammad entered the house of Umm Haraam, and she provided him with food and started grooming his head. Then the Messenger of God slept, and then he woke up smiling. Umm Haraam asked, "What is making you smile, O Messenger of God?” He ﷺ said, "Some people of my ummah were shown to me (in my dream) campaigning for the sake of God, sailing on the green sea like kings on thrones".[31]

The policy of the early caliphates, which spans from Rashidun until Umayyad dynasty, was to judiciously select with particular emphasis of early concept of territorial expansion of Jihad and spread of Islam as their main strategic aims.[278] Blankinship regarded the military institution of the caliphate from the time of Rashidun and Umayyad as one element,[22] at least until the end of the rule of the 10th Umayyad caliph, Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik.[23] This is because the Rashidun caliphs, and the early Umayyad caliph, are still regarded Jihad expansion as their main religious and political motive.[23]

'Piracy in modern scholar view' misconception

[edit]Hassan Khalilieh argues that western scholars mistook the major Islamic naval expeditions by describing Islamic mediterranean territories as haven of pirates. In doing so, they confused the concept of hiraba (piracy/robbery of sea highways) with jihad (striving "in the Cause of God), Ghazw (military expedition) with qital (military engagement) which is based on prejudice and exclusive reliance on non Arabic source.[279] Thus Khalilieh argued, when Islamic jurists encountered act of piracy without legal predecent, they simply applied land law to the sea.[280]

Azeem said the caliphate navy principles and practices were advanced for their era before the development of the modern Western international law concerning the oceans.[281] Azeem said the Islamic law of the sea dealt with territorial sovereignty, freedom of navigation, and exploitation of marine resources. Islamic naval warfare is about the conduct of hostilities and neutrality at the seas, while Islamic maritime tradition concerns shipwreck, salvage, condition of vessels and duties of the captains, etc. These are three interconnected as well as separate entities of law. Azeem quoted Al-Dawoody, Legal Adviser for Islamic Law and Jurisprudence at the (ICRC). In this regards, the laws were consisted of Primary sources consisted of the Quran, Sunnah, ijma (consensus), and qiyas (analogy), while Secondary sources are consisted of several jurisprudential methods for developing the rules, such as istihsan (juristic discretion), maslahah mursalah(public interest), urf(custom), shar' man qablana(law of religions before Islam), madhhab al-sahabi (opinions of the Companions of Muhammad), sadd al-dharai (blocking the means to evil), and istishab (continuation of a previous rule).[282]

Gene Harold Outka, Professor of Philosophy and Christian Ethics of Yale University,[283] held that medieval juristic literature viewed war as a mundane and universal aspect of human existence, and as such, something the Islamic law should included within its purview scope, particularly regarding the law of Jihad.[284]

The example of usage of the traditions as the naval lawcode lawcode shown by Busr ibn abi Arta'ah, Rashidun and later Umayyad Amir of navy, who once quoted Muhammad's words regarding the legal punishments that found in Jami' al-Tirmidhi: "The hands are not cut in the battles.", which dealing about the matter of thievery(which normally the perpetrator hand should be cut during normal times) while the situation were during war times or during military expedition journey.[285] Sunan an-Nasa'i confirmed Busr narration from Busr colleague, Junadah ibn Abi Umayyah, who heard Busr quoting it.[286]

Naval legacy

[edit]Military legacy

[edit]

The 'Abbasid caliphate which succeeded Umayyad, operated their naval force from Taurus, while the Byzantines were based in the port of Cibyrrhaeot and Samian.[173] The Muslim naval invasion of Cyprus was continued during the 'Abbasid rule in the year 157 AH/773 AD, as naval forces were sent by Caliph al-Mansur to reconquer Cyprus and arrest the island governor.[173] However, Caliph Abu Ja‘far al-Mansur did not impose any new taxes on the Cypriots and he revoked the tax increases which has been imposed by Caliph Mu‘awiyah decades earlier.[173] In the first year of Caliph al-Mu‘tasim's reign, there were several battles with the Byzantines in Amorium, which ended in the heavy defeat of the Byzantine's in the year 223 A.H./838 A.D.[173] In addition, the conquest of Sicily and Crete by the Muslim navy, occurred in the same year.[173] Emperor Theophilus resorted to requesting aid from other states, such as from Louis the Pious, who had sent his navy to attack Levant and Egypt. In the year, 839 AD, Emperor Theophilus obtained the necessary reinforcements, although they did not make any gains.[173]

The caliphate armed forces had attacked the island of Crete from the 7th century AD onwards, as the 'Abbasid navy during the rule of Caliph Harun al-Rashid had sent Humayd ibn Ma’yuf al-Hamdani for this purpose.[173] During the reign of Caliph al-Ma’mun, he sent Abu Hafs 'Umar ibn 'Isa al-Andalusi, more famously known as al-Ikritish.[173] Later, Crete once again by the Muslim force from Spain during the reign of al-Ma’mun. In the year 226 AH/841 AD, a peace treaty was ratified by Theophilus and Caliph al-Mu‘tasim that was in force, until the Caliph ordered a naval expedition to attack Constantinople, while later in the year 227 AH/842 AD, the naval enterprise that was led Abu Dinar with 400 men to sail from the port of Levant.[173] The Caliph died in the same year as Theophilus and did not live to witness the destruction of his navy as the naval forces of the caliphate were hit by a sea storm at Chelidonian along the coast of Lycian. Seven Abbasid battleships later made a decision to return to the Levant.[173] At the end of the 3rd AH/early 10th AD, the Abbasid navy was already considered as formidable power in the Aegean Sea. At this time, there was a plot within the Byzantine nobility to depose Emperor Leo VI, known as Leo VI the Wise by General Andronicus, who was supported by his son, Constantine and an aristocrat named Eustace. This combination of three prominent rebels joining forces strength from the aspect of feudal land and naval commander descent. From the year 894 AD., Eustace was the Byzantine chief admiral.[173] In the year 289 AH/August 902 AD, Eustace engaged in conflict with the Muslim army and during the winter had met up with Nicholas Mysticus to come to an understanding for the common interest of all and the church.[173] Samonas, an Arabic eunuch, had entered into the Emperor's service and helped Emperor Leo VI to abort a plan by the relatives of Augusta Zoe who wished to overthrow the Emperor.[173] Samonas was then placed in personal service to the Emperor. However, Samonas attempted to flee to Levant in March 904 AD after betraying the Emperor, but was caught and brought back by the Byzantines.[173] On Leo VI's order, Samonas was executed. In the middle of Sha‘ban 291 AH/early July 904 AD, the naval army had 54 galleys which each of them carrying about 200 fighters as well as officers and was led by the Rashid al-Wardani or Ghulam Zurafa.[173]

Abbasids and Aghlabids

[edit]