Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Aqaba

View on Wikipedia

Aqaba (English: /ˈækəbə/ AK-ə-bə,[2] US also /ˈɑːk-/ AHK-;[3] Arabic: الْعَقَبَة, romanized: al-ʿAqaba, pronounced [ælˈʕæqɑba, ælˈʕæɡæba]) is the only coastal city in Jordan and the largest and most populous city on the Gulf of Aqaba.[4] Situated in southernmost Jordan, Aqaba is the administrative center of the Aqaba Governorate.[5] The city had a population of 148,398 in 2015 and a land area of 375 square kilometres (144.8 sq mi).[6] Aqaba has significant trade and tourism. The Port of Aqaba also serves other countries in the region.[7]

Key Information

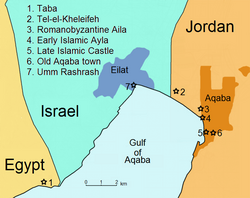

Aqaba's strategic location at the northeastern tip of the Red Sea between the continents of Asia and Africa has made its port important for thousands of years.[7] The ancient city was called Elath, known in Latin as Aela) and in Arabic as Ayla. Its strategic location and proximity to copper mines made it a regional hub for copper production and trade in the Chalcolithic period.[8]

Aela became a bishopric under Byzantine rule and later became a Latin Catholic titular see after Islamic conquest around AD 650, when it became known as Ayla; the name Aqaba is late medieval.[9] In the Great Arab Revolt's Battle of Aqaba Arab forces defeated the Ottoman defenders.[10]

Aqaba's location next to Wadi Rum and Petra has made it one of the major tourist attractions in Jordan.[11] The city is administered by the Aqaba Special Economic Zone Authority, which has turned Aqaba into a low-tax, duty-free city, attracting several mega projects like Ayla Oasis, Saraya Aqaba, Marsa Zayed and expansion of the Port of Aqaba.[12] They are expected to turn the city into a major tourism hub in the region.[13] However, industrial and commercial activities remain important, due to the strategic location of the city as the country's only seaport.[14] The city sits right across the border from Eilat, likewise Israel's only port on the Red Sea. After the 1994 Israel–Jordan peace treaty, there were plans and hopes of establishing a trans-border tourism and economic area, but few of those plans have come to fruition.[15][16][17]

Name

[edit]In antiquity, the name of the city was Elath or Ailath. The name is presumably derived from the Semitic name of a tree in the genus Pistacia.[18] Modern Eilat (established 1947), situated about 5 km north-west of Aqaba, also takes its name from the ancient settlement. In the Hellenistic period, it was renamed Berenice (Ancient Greek: Βερενίκη Bereníkē), but the original name survived, and under Roman rule was re-introduced in the forms Aila,[19] Aela or Haila, adopted in Byzantine Greek as Αἴλα Aíla and in Arabic as Ayla (آيلا).[20] The crusaders called the city Elyn.[21]

The present name comes from the identically-named Gulf of Aqaba, named that as early as 150 A.D. (or somewhat later, if added by a subsequent editor), as evidenced by the plotting of a Mt. Acabe ('Ακάβη όρος) in Ptolemy's Geography[22], which mountain is shown directly across from the mouth of the Gulf of Aqaba, on the western coast of the Red Sea, probably somewhere in the vicinity of modern Hurghada, Egypt, and ancient Mons Claudianus, both of which placenames could also themselves be derived cognate forms of the word Aqaba, the former by morphological drift, the latter as a translation into Latin, wherein "Claudianus" also suggests limping or stumbling[23], a perfect semantic overlap for the literal Arabic meaning of "Aqaba" (عقبة), as an "obstacle," "stumbling block," or "spine." Thus the Gulf of Aqaba may've in turn gotten its name from this older region, West of it, around Mt. Acabe (not necessarily a single identifiable mountain), construed as the rough spine of highland that must be crossed, to pass thru the natural trade corridor there, from the Upper Nile to the Red Sea, along modern Egyptian Highway 60.

This name first became mentioned in connection with the city itself of Aqaba, in the 12th century, as ʿaqabat Aylah (عقبة آيلة, 'the mountain-pass of Ayla'), mentioned by Idrisi, at a time when the settlement had been mostly reduced to a military stronghold, properly referring to the pass just to the north-east of the settlement (29°33′32″N 35°05′42″E / 29.559°N 35.095°E, now traversed by the Jordanian Aqaba Highway).[24][25]

History

[edit]

Nearby Chalcolithic sites

[edit]

Excavations at two tells (archaeological mounds) Tall Hujayrat Al-Ghuzlan and Tall Al-Magass, both a few kilometres north of modern-day Aqaba city, revealed inhabited settlements from c. 4000 BC during the Chalcolithic period, with thriving copper production on a large scale.[26] This period is largely unknown due to the absence of written historical sources.[8] University of Jordan archaeologists have discovered the sites, where they found[where?] a small building whose walls were inscribed with human and animal drawings, suggesting that the building was used as a religious site. The people who inhabited the site had developed an extensive water system in irrigating their crops which were mostly made up of grapes, olives and wheat. Several different-sized clay pots were also found suggesting that copper production was a major industry in the region, the pots being used in melting the copper and reshaping it. Scientific studies performed on-site revealed that it had undergone two earthquakes, with the latter one leaving the site completely destroyed.[27]

Early history

[edit]Elath

[edit]The Edomites, who ruled over Edom just south of the Dead Sea, are believed to have built the first port in Aqaba called Elath around 1500 BC,[citation needed] turning it into a major hub for the trade of copper as the Phoenicians helped them develop their maritime economy. They profited from its strategic location at the junction of trading routes between Asia and Africa.[citation needed]

Tell el-Kheleifeh

[edit]Archaeologists have investigated an Iron Age settlement at Tell el-Kheleifeh, immediately west of Aqaba, inhabited between the 8th and 4th centuries BCE.[28]

Undefined

[edit]Around 735 BC, the city[dubious – discuss] was conquered by the Assyrian empire. Because of the wars the Assyrians were fighting in the east, their trading routes were diverted to the city and the port witnessed relative prosperity. The Babylonians conquered it in 600 BC. During this time, Elath witnessed great economic growth, which is attributed to the business background of its rulers who realized how important the city's location was. The Persian Achaemenid Empire took the city in 539 BC.[29][unreliable source?][dubious – discuss]

Classical antiquity

[edit]Hellenistic period

[edit]The city continued to grow and prosper which made it a major trading hub by the time of the Greek rule by 300 BC, after the Wars of Alexander the Great, it was described by a Greek historian to be "one of the most important trading cities in the Arab World".[29] The Ptolemaic Greeks called it Berenice.[30]

The Nabatean kingdom had its capital north of the city, at Petra.

Roman period

[edit]

In 64 BC, following the Roman conquest, they[who?] annexed the city and called it Aela (also Haila, Aelana, in Greek rendered Αἴλα Aila).[31][28]

Both Petra and Aela were under strong Nabatean influence despite the Roman rule.[dubious – discuss] Aela reached its peak during Roman times, the great long-distance road the Via Traiana Nova led south from Bostra through Amman, terminating in Aela, where it connected with a west road leading to the Paralia and Roman Egypt.

Around AD 106 Aela was one of the main ports[clarification needed] for the Romans.[dubious – discuss]

Late Roman and Byzantine periods

[edit]The Aqaba Church was constructed under Roman rule between 293 and 303 and is considered to be the oldest known purpose-built Christian church in the world.[32] By the time of Eusebius, Aela became the garrison of the Legio X Fretensis, which was moved to Aela from Jerusalem.[33]

One of the oldest known texts written in the Arabic alphabet is a late 4th-century inscription found in Jabal Ram 50 kilometres (31 miles) east of Aqaba.[34]

The city became a Christian bishopric at an early stage. Its bishop Peter was present at the First Council of Nicaea,[35] the first ecumenical council, in 325. Beryllus was at the Council of Chalcedon in 451, and Paul at the synod called by Patriarch Peter of Jerusalem in 536 against Patriarch Anthimus I of Alexandria, a council attended by bishops of the Late Roman provinces of Palaestina Prima, Palaestina Secunda and Palaestina Tertia, to the last-named of which Aela belonged.[36][37]

A citadel was also built in the area[where?][when?] that became the focal point of the Roman southern defense system.[clarification needed]

In the 6th century, Procopius of Caesarea mentioned a Jewish population in Eilat and its surroundings which enjoyed autonomy until the time of Justinian I (r. 527–565).[clarification needed]

According to Ibn Ishaq, Muhammad himself reached Aila during the expedition of Tabuk of 630, and extracted tribute from the city.[38]

During the Late Byzantine or even Early Muslim period, Aila was the origin of what came to be known as the Ayla-Axum amphoras.[39]

Early Muslim Ayla

[edit]Aila fell to the Islamic armies by 629, and the ancient settlement was left to decay, while a new Arab city was established outside its walls under Uthman ibn Affan,[40] known as Ayla (Arabic: آيلا).

The Early Muslim city was excavated in 1986 by a team from the University of Chicago. Artefacts are now on exhibit at Aqaba Archaeological Museum and Jordan Archaeological Museum in Amman.[citation needed] The fortified city was inscribed in a rectangle of 170 × 145 meters, with walls 2.6 meters thick and 4.5 meters high, surrounding a fortified structure, occupying an area of 35 × 55 meters.[dubious – discuss][citation needed] 24 towers defended the city. The city had four gates on all four sides, defining two main lines intersecting at the centre. The intersection of these two thoroughfares was indicated by a tetrapylon (a four-way arch), which was later transformed into a luxury residential building decorated with frescoes dated to the tenth century.[citation needed] This type of urban structure, known as a misr (pl. amsar), is typical of early Islamic fortified settlements.[citation needed]

-

Early Muslim Ayla

-

Early Muslim Ayla

The city prospered from 661 to 750 under the Umayyads and beyond under the Abbasids (750–970) and the Fatimids (970–1116). Ayla took advantage of its key position as an important step on the road to India and Arab spices (frankincense, myrrh), between the Mediterranean Sea and the Arabian Peninsula. The city is also mentioned in several stories of the Arabian Nights.[citation needed]

The geographer Shams Eddin Muqaddasi describes Ayla as nearby the ruined ancient city.[41]

The city was mentioned in Medieval[when?] Arabic sources as having a mixed population of Jews and Christians. It subsequently became an important station for pilgrim caravans on the way to Mecca.[clarification needed][42]

The city was "completely destroyed" by the 1068 Near East earthquake.[43]

Crusader/Ayyubid and Mamluk periods

[edit]

Baldwin I of Jerusalem took over the city in 1115 without encountering much resistance. The centre of the city then moved to 500 meters along the coast to the south, and the crusader fortress of Elyn was built, which allowed the Kingdom of Jerusalem to dominate all roads between Damascus, Egypt, and Arabia, protecting the Crusader states from the east and allowing for profitable raids on trade caravans passing through the area. In order to secure this strategic position, Baldwin also built and garrisoned a fortress on Pharaoh's Island (called Île de Graye by the Franks), the modern Jazīrat Fir'aun in Egyptian territorial waters about 7 kilometres (4 miles) west of Aqaba.[21]

The garrison of Elyn (now serving primarily as a military outpost) was further strengthened in 1142 by Pagan the Butler, Lord of Oultrejourdain, who pursued an ambitious program of castle building throughout his domain. However, there was no large-scale settlement of Europeans in the area, and the region between the Dead Sea and the Gulf of Aqaba remained mainly inhabited by Bedouins, who were obliged to pay tribute to the Lordship of Oultrejourdain.[44] Despite all efforts to fortify the region, the city was captured in 1170 by a squadron sent by Saladin as he was besieging Gaza; while it was successfully raided by Raynald of Châtillon in 1182,[45] it was never retaken by the Crusaders.[46]

The old fort was rebuilt, as Aqaba Fortress, by Mamluk sultan Al-Ashraf Qansuh Al-Ghuri in the early 16th century. For the next four centuries, the site was a simple fishing village of little importance.[citation needed]

Modern history

[edit]During World War I, the Ottoman forces were forced to withdraw from Aqaba in 1917 after the Battle of Aqaba, led by T. E. Lawrence and the Arab forces of Auda Abu Tayi and Sherif Nasir. The capture of Aqaba allowed the British to supply the Arab forces.[10] In 1918, the regions of Aqaba and Ma'an were officially incorporated into the Kingdom of the Hejaz. In 1925, Ibn Saud the ruler of Nejd with the help of his Wahhabi Ikhwan troops successfully annexed the Hejaz, but gave up the Ma'an and Aqaba to the British protectorate of Transjordan.[47]

-

Lawrence of Arabia on a camel in Aqaba in 1917

-

Aqaba in 1937

-

1822 area map by Eduard Rüppell, modern borders overlaid. His "Ruines d'Elana" is the site of Tell el-Kheleifeh.

The Jordanian census of 1961 found 8,908 inhabitants in 'Aqaba.[48]

In 1965, King Hussein, through an exchange deal with Saudi Arabia, gave 6,000 square kilometres (2,317 square miles) of desert land in Jordanian territories in exchange for other territories, including 12 kilometres (7 miles) of an extension of prime coastline south of Aqaba, which included the Yamanieh coral reef.[49] Aqaba was a major site for imports of Iraqi goods in the 1980s until the Persian Gulf War.[50]

In 1997, the Aqaba Marine Reserve was established within the southern boundaries of the Gulf of Aqaba.

Geography

[edit]The city lies at Jordan's southernmost point, on the Gulf of Aqaba lying at the tip of the Red Sea. Its strategic location is shown in the fact that it is located at the crossroads of the continents of Asia and Africa, while bordering Israel, Egypt and Saudi Arabia.[51]

Climate

[edit]Aqaba has a hot desert climate (Köppen climate classification BWh) with mild, sometimes warm winters and very hot dry summers. Subzero temperatures can be observed every few years. The record high temperature of 49.6 °C (121.3 °F) was registered on 14 August 2025 [52]. The record low temperature of −3.9 °C (25.0 °F) was on January 16, 2008, as in Eilat.

| Climate data for Aqaba (King Hussein International Airport) (1989–2018 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 20.4 (68.7) |

22.5 (72.5) |

26.4 (79.5) |

31.3 (88.3) |

35.5 (95.9) |

38.7 (101.7) |

40.1 (104.2) |

39.7 (103.5) |

36.9 (98.4) |

32.9 (91.2) |

27.2 (81.0) |

22.1 (71.8) |

31.1 (88.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 14.9 (58.8) |

16.6 (61.9) |

20.1 (68.2) |

24.6 (76.3) |

28.6 (83.5) |

31.5 (88.7) |

33.3 (91.9) |

33.2 (91.8) |

30.7 (87.3) |

26.9 (80.4) |

21.4 (70.5) |

16.5 (61.7) |

24.9 (76.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 9.3 (48.7) |

10.6 (51.1) |

13.8 (56.8) |

17.8 (64.0) |

21.6 (70.9) |

24.3 (75.7) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.6 (79.9) |

24.4 (75.9) |

20.9 (69.6) |

15.6 (60.1) |

10.9 (51.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 4.2 (0.17) |

4.0 (0.16) |

2.7 (0.11) |

1.5 (0.06) |

0.5 (0.02) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

4.6 (0.18) |

2.3 (0.09) |

3.5 (0.14) |

23.4 (0.92) |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 58.5 | 53.3 | 49.6 | 41.7 | 38.8 | 38.4 | 39.7 | 43.3 | 48.5 | 51.6 | 53.0 | 57.0 | 47.8 |

| Source: Jordan Meteorological Department[53] | |||||||||||||

Local government

[edit]In August 2000, the Aqaba Special Economic Zone Authority (ASEZA) was established which acted as the statutory institution empowered with administrative, fiscal, regulatory and economic responsibilities.[54]

Administrative divisions

[edit]Jordan is divided into 12 administrative divisions, each called a Governorate. Aqaba Governorate divides into 3 Districts, some of which are divided into Subdistricts and further divided into villages.

Economy

[edit]With status as Jordan's special economic zone, Aqaba's economy is based on the tourism and port industry sectors.[4][7] Aqaba's location next to Wadi Rum and Petra has strengthened the city's location on the world map and made it one of the major tourist attractions in Jordan.[11] The city is administered by the Aqaba Special Economic Zone Authority, which has turned Aqaba into a low-tax, duty-free city, attracting several mega projects like Ayla Oasis, Saraya Aqaba, Marsa Zayed and expansion of the Port of Aqaba.[12] They are expected to turn the city into a major tourism hub in the region.[13] Industrial and commercial activities remain important, due to the strategic location of the city as the country's only seaport.[14]

Aqaba is the only seaport of Jordan so virtually all of Jordan's exports depart from here. Heavy machinery industry is also flourishing in the city with regional assembly plants being located in Aqaba such as the Land Rover Aqaba Assembly Plant. By 2008 the ASEZ had attracted $18bn in committed investments, beating its $6bn target by 2020 by a third and more in less than a decade. The goal was adjusted to bring in another $12bn by 2020, but in 2009 alone, deals worth $14bn were inked.[55] Some projects currently under construction are:

- Marsa Zayed a $10 billion is the largest mega mixed-use development project ever envisioned in both Jordan and the region. Marsa Zayed will host facilities including residential neighborhoods, commercial outlets and amenities, entertainment venues, financial and business facilities, and a number of hotels. Additionally, the property will feature marinas and a cruise ship terminal. Marsa Zayed will encompass 6.4 million square meters of built-up property.

- Saraya Aqaba, a $1.5 billion resort with a man made lagoon, luxury hotels, villas, and townhouses that will be completed by 2017.[needs update]

- Ayla Oasis, a $1.5 billion resort around a man made lagoon with hotels, villas, an 18-hole golf course designed by Greg Norman. It also has an Arabian Venice theme with apartment buildings built along canals only accessible by walkway or boat. This project will be completed by 2017.

- Tala Bay, Tala Bay was developed in a distinctive architectural style that blends Jordanian and regional architecture with total cost of US$680 million. Another distinguishing feature of this single community resort is its two-kilometer private sandy beach on the Red Sea.

- The Red Sea Astrarium (TRSA), the world's only Star Trek themed park, worth $1.5 billion would have been completed by 2014 but cancelled in 2015.

- Port relocation. Aqaba's current port will be relocated to the southernmost part of the province near the Saudi border. Its capacity will surpass that of the current port. The project costs $5 billion, and it will be completed by 2013.

- Aqaba will be connected by the national rail system which will be completed by 2013. The rail project will connect Aqaba with all Jordan's main cities and economic centers and several countries like Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Syria.

- The Aqaba Container Terminal (ACT) handled a record 587,530 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) in 2008, an increase of 41.6% on the previous year. To accommodate the rise in trade on the back of the increasing popularity of container shipping and the stabilising political situation in Iraq, the Aqaba Development Corporation (ADC) has announced plans for a new port. The port relocation 20 kilometres (12 miles) to the south will cost an estimated $600m and will improve infrastructure, while freeing up space for development in the city. Plans for upgrading the King Hussein International Airport (KHIA) and the development of a logistics centre will also help position Aqaba as a regional hub for trade and transport.[55]

Tourism

[edit]

Aqaba has a number of luxury hotels, including in the Tala Bay resort 20 km further to the south, which service those who come for fun on the beaches as well as Scuba diving. Aqaba offers more than thirty primary diving locations, with the majority of them accommodating divers of all skill levels. These diving sites comprise fringing reefs that extend for over 25 kilometers, reaching all the way to the border with Saudi Arabia.

It also offers activities which take advantage of its desert location. Its many coffee shops offer mansaf and knafeh, and baqlawa desserts. Another very popular venue is the Turkish Bath (Hamam) built in 306 AD, in which locals and visitors alike come to relax after a hot day.

In 2006, the Tourism Division of the Aqaba Special Economic Zone Authority (ASEZA) reported that the number of tourists visiting the Zone in 2006 rose to about 432,000, an increase of 5% over previous year. Approximately 65%, or 293,000 were Jordanians. Of foreign tourists, Europeans visited the Zone in the largest numbers, with about 98,000 visiting during the year. The division has financed tourism advertising and media campaigns with the assistance of the European Union.[56]

Aqaba has been chosen for the site of a new waterfront building project that would rebuild Aqaba with new man-made water structures, new high-rise residential and office buildings, and more tourist services to place Aqaba on the investment map and challenge other centers of waterfront development throughout the region.

Aqaba was chosen as the Arab Tourism City of 2011.[57][58][59][14]

During the 5-day holiday at both the end of Ramadan and Eid Al-Adha, Jordanian and western expats flock into the city with numbers reaching up to 50,000 visitors. During this time the occupancy rate of most hotels there reaches as high as 90%, and are often fully booked.[60]

The several development projects (i.e. Ayla, Saraya etc.) now taking place in Aqaba provide "opportunities of empowerment" for local populations that want to expand their agency within the city. According to Fulbright scholar Kimberly Cavanagh development projects will help exhibit the ways global- local partnerships and the resultant cultural exchanges, can result in mutually beneficial outcomes.[61]

Demographics

[edit]The city of Aqaba has one of the highest population growth rates in Jordan in 2011, and only 44% of the buildings in the city had been built before 1990.[62] A special census for Aqaba city was carried by the Jordanian department of statistics in 2007, the total population of Aqaba by the census of 2007 was 98,400. The 2011 population estimate is 136,200. The results of the census compared to the national level are indicated as follows:

| Demographic data of the city of Aqaba (2007) compared to Kingdom of Jordan nationwide[62] | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aqaba City (2007) | Jordan (2004 census) | |||||||||

| 1 | Total population | 98,400 | 5,350,000 | |||||||

| 2 | Growth rate | 4.3% | 2.3% | |||||||

| 3 | Male to Female ratio | 56.1 to 43.9 | 51.5 to 48.5 | |||||||

| 4 | Ratio of Jordanians to Foreign Nationals | 82.1 to 17.9 | 93 to 7 | |||||||

| 5 | Number of households | 18,425 | 946,000 | |||||||

| 6 | Persons per household | 4.9 | 5.3 | |||||||

| 7 | Percent of population below 15 years of age | 35.6% | 37.3% | |||||||

| 8 | Percent of population over 65 years of age | 1.7% | 3.2% | |||||||

Religion

[edit]

ِIslam represents the majority of the population of Aqaba, but Christianity still exists today. Approximately 5,000 Christian families live in the city.[63] There are several churches in the city and multiple Christian schools including Rosary Sisters School Aqaba.[64][65]

Cityscape

[edit]

Residential buildings in Aqaba are made up of 4 stories, of which are covered with sandstone or limestone. The city has no high-rises; however, Marsa Zayed project is planned to dramatically change that reality through the construction of several high-rise towers that host hotels, residential units, offices and clinics.

Culture

[edit]Museums

[edit]The largest museum in Aqaba is the Aqaba Archaeological Museum.

Lifestyle

[edit]Aqaba has recently experienced a great growth in its nightlife, especially during the dramatic increase of tourist number in the 2000s.[citation needed]

Transport

[edit]Rail

[edit]The Aqaba railway which transported phosphate to the old port ceased operations in 2018. A successor line to transport phosphate from Al Shidiya and Ghor es-Safi to the new terminal in Port of Aqaba is planned through an agreement between Jordan's Ministry for Transport and Etihad Rail.[66]

There has been propositions to connect Eilat to Aqaba by rail.[67][68]

Airports

[edit]King Hussein International Airport is the only civilian airport outside of Amman in the country, located to the north of Aqaba. It is a 20-minutes drive away from the city center. Regular flights are scheduled from Amman to Aqaba with an average flying time of 45 minutes which is serviced by Royal Jordanian Airlines and Jordan Aviation Airlines. Several international airlines connect the city to Istanbul, Dubai, Alexandria, Sharm el-Sheikh, and other destinations in Asia and Europe.[69] Since the 1994 Peace Treaty between Israel and Jordan, there were plans to jointly develop airport infrastructure in the region.[70] However, when Israel built Ramon Airport only 10 km distant from King Hussein International Airport, this happened without consulting the Jordanian side, which caused a slight deterioration of bilateral relations between the two countries and concerns over the safety of having two airports so close together.[71][72]

Roads

[edit]

Aqaba is connected by an 8,000 kilometres (5,000 mi) modern highway system to surrounding countries. The city is connected to the rest of Jordan by the Desert Highway and the King's Highway that provides access to the resorts and settlements on the Dead Sea.[69] Aqaba is connected to Eilat in Israel by taxi and bus services passing through the Wadi Araba crossing. And to Haql in Saudi Arabia by the Durra Border Crossing. There are many bus services between Aqaba and Amman and the other major cities in Jordan, JETT and Trust International are the most common lines. These tourist buses are spacious and installed with air conditioning and bathrooms.[73]

Port

[edit]

The Port of Aqaba is the only port in Jordan. Regular ferry routes to Taba are available on a daily basis and are operated by several companies such as Sindbad for Marine Transportation and Arab Bridge Maritime. The routes serve mainly the Egyptian coastal cities on the gulf like Taba and Sharm Al Sheikh.[69] In 2006, the port was ranked as being the "Best Container Terminal" in the Middle East by Lloyd's List. The port was chosen for its recent improvements and its ability to handle local traffic as well as international traffic to four neighboring countries.[74]

Wildlife

[edit]The Gulf of Aqaba is rich with marine life. The gulf is home to approximately 500 fish species, with many being permanent residents, like lion fish and octopus, while others are migratory, typically appearing during the summer, such as sailfish, considered the fastest fish in the ocean, as well as the world's largest fish, the whale shark. Marine mammals and reptiles also inhabit the gulf during summer, hawksbill sea turtles, and bottle nosed dolphins call Aqaba's gulf home as well. A large number of predatory shark species used to inhabit Aqaba's gulf but, due to overfishing and pollution, this population is in decline. While mostly deep water sharks such as the tiger sharks and thresher sharks are present, there are also a small number of reef sharks as well. The world's fastest shark, the short-fin mako shark is the most commonly caught species by fishermen in Aqaba. Whale sharks, locally known as Battan, are the most commonly sighted. Conservationists are working hard to protect Aqaba's shark population.[75][76]

The gulf of Aqaba hosts more than 390 bird species including migratory birds such as the greater flamingo, great white pelican and the pink-backed pelican.[77]

Education

[edit]There is a University of Jordan Aqaba Branch.

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]Aqaba is twinned with:

Alcamo, Italy[78]

Alcamo, Italy[78] Basra, Iraq[citation needed]

Basra, Iraq[citation needed] Hammamet, Tunisia[79]

Hammamet, Tunisia[79] Saint Petersburg, Russia[80]

Saint Petersburg, Russia[80] Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt[81]

Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt[81] Ürümqi, China[82]

Ürümqi, China[82]

Gallery

[edit]-

View of Aqaba

-

The Eastern Gate of the ruins of Ayla

-

Sunset

-

View of the city

-

Aqaba fort

-

View of Aqaba

-

One of the resorts in the city

-

Shatt Al-Ghandour gardens

-

The Red Sea Summit in Aqaba in 2003

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The General Census – 2015" (PDF). Department of Population Statistics. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917], Peter Roach; James Hartmann; Jane Setter (eds.), English Pronouncing Dictionary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 3-12-539683-2

- ^ "Aqaba". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ a b "العقبة.. مدينة الشمس والبـــحر والسلام". Ad Dustour (in Arabic). 1 April 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2016. [permanent dead link]

- ^ "Fact Sheet". Aqaba Special Economic Zone Authority. Aqaba Special Economic Zone Authority. 2013. Archived from the original on 24 September 2017. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ^ a b Ghazal, Mohammad (22 January 2016). "Population stands at around 10.24 million, including 2.9 million guests". The Jordan Times. The Jordan News. Archived from the original on 8 February 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2016.

- ^ a b c "Port expansion strengthens Jordanian city of Aqaba's position as modern shipping hub". The Worldfolio. Worldfolio Ltd. 27 February 2015. Archived from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ^ a b Florian Klimscha (2011), Long-range Contacts in the Late Chalcolithic of the Southern Levant. Excavations at Tall Hujayrat al-Ghuzlan and Tall al-Magass near Aqaba, Jordan, archived from the original on 31 August 2021, retrieved 22 April 2016

- ^ "العقبة.. ثغر الاردن الباسم". Ad-Dustor Newspaper. 21 June 2013. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ^ a b "The Taking of Akaba – 1917 – T.E. Lawrence, Auda abu Tayi, Prince Feisal, Port of Aqaba". www.cliohistory.org. Archived from the original on 31 May 2019. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ a b "Jordan tapping popularity of UEFA Champions League to promote tourism". The Jordan Times. The Jordan News. 26 March 2015. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ^ a b "King checks on Aqaba Mega-Projects". The Jordan Times. 7 June 2012. Archived from the original on 28 September 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ^ a b "Aqaba has caught mega-project fever from its Gulf neighbours". Your Middle East. 29 April 2013. Archived from the original on 28 June 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ^ a b c Jean-Eric Aubert; Jean-Louis Reiffers (2003). Knowledge Economies in the Middle East and North Africa: Toward New Development Strategies. World Bank Publications. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-8213-5701-9. Archived from the original on 16 December 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ "Cross border interactions across a formerly hostile border: The case of Eilat, Israel and Aqaba, Jordan". Researchgate.net. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ Gradus, Yehuda (1 May 2001). "Is Eilat-Aqaba a bi-national city? Can economic opportunities overcome the barriers of politics and psychology?". GeoJournal. 54 (1): 85–99. Bibcode:2001GeoJo..54...85G. doi:10.1023/A:1021196800473. S2CID 141312410. Retrieved 5 December 2021 – via Springer Link.

- ^ "Working Paper 15 : Municipal Cooperation across Securitized Borders in the PostConflict Environment: The Gulf of Aqaba" (PDF). Euborderscapes.eu. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ Grinzweig, Michael (1993). Cohen, Meir; Schiller, Eli (eds.). "From the Items of the Name Eilat". Ariel (in Hebrew) (93–94: Eialat – Human, Sea and Desert). Ariel Publishing: 110.

- ^ TSAFRIR, YORAM (1986). "The Transfer of the Negev, Sinai and Southern Transjordan from 'Arabia' to 'Palaestina.'". Israel Exploration Journal. 36 (1/2). Israel Exploration Society: 78. JSTOR 27926015. Archived from the original on 18 May 2021. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

Aila is described as a city of Arabia

- ^ The Umayyads: The Rise of Islamic Art. AIRP. 2000. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-874044-35-2. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ a b Steven Runciman (1952). A History of the Crusades: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East 1100-1187. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 79.

- ^ Ptolemaeus, Claudius (1843). Geographia. Leipzig: Karl Friedrich August Nobbe. p. vol. 1, p. 252. Retrieved 24 September 2025.

- ^ Lewis and Short (1879). A Latin Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. C.53.claudeo. Retrieved 24 September 2025.

- ^ Moshe Sharon (1997). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae. Vol. 3. p. 89.

- ^ Yoel Elitsur (2004). Ancient place names in the Holy Land. Magnes Press. p. 35.

- ^ Trudy Ring; Robert M. Salkin; Sharon La Boda (1994). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Middle East and Africa, المجلد 4. Taylor & Francis. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-884964-03-9. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ "اكتشافات أثرية في موقع حجيرة الغزلان بوادي اليتيم في جنوب الأردن". Alghad (in Arabic). 18 February 2008. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ a b "Aqaba". ArcGIS StoryMaps. Archived from the original on 15 March 2021. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ^ a b "The Beach of History (3700 BC to date)". aqaba.jo. AQABA. Archived from the original on 28 September 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ^ Mayhew 2006

- ^ In classical texts the Roman city is known as Aela, occasionally Haila or Aelana. Aela is the standard form of the name in Roman-era classical studies.

See:

Glen Warren Bowersock (1994). Roman Arabia. Harvard University Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-674-77756-9. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

Neil Asher Silberman (2012). The Oxford Companion to Archaeology. Oxford University Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-19-973578-5. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

Averil Cameron; Peter Garnsey, eds. (1928). The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 13. Cambridge University Press. p. 846. ISBN 978-0-521-30200-5. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) [Stéphanie Benoist (editor), Rome, A City and Its Empire in Perspective (BRILL 2012 ISBN 978-9-00423123-8), p. 128] Suzanne Richard, Near Eastern Archaeology: A Reader Archived 26 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine (Eisenbrauns 2003 ISBN 978-1-57506083-5), p. 436 - ^ "First purpose-built church". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ^ Hannah Cotton (editor), Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaeae/Palaestinae Archived 26 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine (Walter de Gruyter 2010 ISBN 978-31-1022219-7), pp. 25–26 [Brian M. Fagan, Charlotte Beck (editors), The Oxford Companion to Archaeology] (Oxford University Press 1996 ISBN 978-0-19507618-9), p. 617. Benjamin H. Isaac, The Near East Under Roman Rule: Selected Papers Archived 30 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine (BRILL 1998 ISBN 978-9-00410736-6), p. 336

- ^ Di Taylor; Tony Howard (1997). Treks and Climbs in Wadi Rum, Jordan. Cicerone Press Limited. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-85284-254-3. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ Irfan Shahid, Byzantium and the Arabs in the Fourth Century (Dumbarton Oaks, 1984) page 345.

- ^ Siméon Vailhé, v. Aela, in Dictionnaire d'Histoire et de Géographie ecclésiastiques Archived 3 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine, vol. I, Paris 1909, coll. 647–648

- ^ Siméon Vailhé, Notes de géographie ecclésiastique Archived 6 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine, in Échos d'Orient, tome 3, nº 6 (1900), pp. 337–338

- ^ Francis E. Peters, Muhammad and the Origins of Islam, p. 241 Archived 26 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ M. Raith – R. Hoffbauer – H. Euler – P. Yule – K. Damgaard, The view from Ẓafār – an archaeometric study of the ʿAqaba late Roman period pottery complex and distribution in the 1st millennium CE, Zeitschrift für Orient-Archäologie 6, 2013f, 320–50

- ^ "The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago – Aqaba Project". Aqaba project. The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ "حفريات أثرية.. العقبة منطقة اقتصادية منذ 6 آلاف سنة". Al-Rai Newspaper. 10 July 2009. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ Gil, Moshe (27 February 1997). A History of Palestine, 634-1099. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521599849. Archived from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- ^ Klinger, Y.; Avoua, J. P.; Dorbath, L.; Abou Karaki, N.; Tisnerat, N. (2000). "Seismic behaviour of the Dead Sea fault along the Araba valley, Jordan". Geophysical Journal International. 142 (3). Wiley-Blackwell: 772. Bibcode:2000GeoJI.142..769K. doi:10.1046/j.1365-246x.2000.00166.x.

The AD 1068 event caused major damage from the Banyas area in northern Israel to Hejaz, and the ancient city of Aila (at the present location of Aqaba and Eilat) was completely destroyed.

- ^ Steven Runciman (1952). A History of the Crusades: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East 1100-1187. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 186.

- ^ Steven Runciman (1952). A History of the Crusades: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East 1100-1187. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 318.

- ^ Steven Runciman (1952). A History of the Crusades: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East 1100-1187. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. pp. 356–357.

- ^ "Jordan - History - the Making of Transjordan". Archived from the original on 21 September 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ^ Government of Jordan, Department of Statistics, 1964, pp. 613

- ^ "Aqaba". kinghussein.gov.jo. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ Eliyahu Kanovsky (1992). The Economic Consequences of the Persian Gulf War: Accelerating Opec's Demise. Washington Institute for Near East Policy. ISBN 978-0-944029-18-3. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ "Location". aqaba.jo. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ^ "40340: Aqaba Airport (Jordan)". ogimet.com. OGIMET. 13 August 2025. Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ "دائرة الأرصاد الجوية > معلومات مناخية وزراعية > المعدلات العامة" (in Arabic). Jordan Meteorological Department. Archived from the original on 21 February 2024. Retrieved 21 December 2024.

- ^ "Aseza". Aqabazone.com. Archived from the original on 5 July 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ a b [1] Archived 29 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Final Ann Rep Eng" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "King visits Aqaba Special Economic Zone Authority | ASEZA". Aqabazone.com. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ Sadeh, Danny (20 June 1995). "Arkia to operate flights to Aqaba – Israel Travel, Ynetnews". Ynetnews. Ynetnews.com. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "ATO: Jordan turned Aqaba into a distinguished city". Zawya. 10 February 2010. Archived from the original on 17 June 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Over 50,000 vacationers visited Aqaba during Eid Al Adha". jordantimes.com. 29 September 2015. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ^ Cavanagh, Kimberly (15 May 2020). "Exploring the tourism development landscape in Aqaba". ACOR Jordan. Archived from the original on 22 November 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ a b "DoS Jordan Aqaba Census" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "أبناء الطائفة المسيحية في العقبة يطالبون بمقعد نيابي". Al-Ghad Newspaper (in Arabic). 19 April 2012. Archived from the original on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ "Construction of a Church and Multi-Purpose Hall in Aqaba". lpj.org. 20 August 2010. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ^ "Raising awareness on solar energy among school students in El Aqaba governorate". NATIONAL ENERGY RESEARCH CENTER. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ^ "Etihad Rail leads new railway construction in Jordan". 6 September 2024.

- ^ "The Red-Med Railway: New Opportunities for China, Israel, and the Middle East". Besacenter.org. 11 December 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ Medzini, Ronen (27 July 2010). "Netanyahu, Abdullah discuss rail cooperation". Ynetnews. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ a b c "Getting to Aqaba". aqaba.jo. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ^ "Israel, Jordan plan joint Aqaba airport". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ "Israel's New Airport Is Angering Jordan, a Rare Friend in the Region". Haaretz. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ "Airport planned for Israel-Jordan border clouds neighborly ties". Reuters.com. 22 June 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ Mayhew 2006, p. 226

- ^ "Top 10 Middle East Ports". ArabianSupplyChain.com. 31 October 2006. Archived from the original on 17 March 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Marine Life | Aqaba". Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- ^ "Aqaba Bird Observatory - Aqaba". Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2020.

- ^ "Siglato gemellaggio tra Alcamo e il Governatore di Aqaba nel Regno della Giordania". alqamah.it (in Italian). Alqama H. 26 November 2013. Archived from the original on 7 November 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ "Coopération Internationale". nabeul.gov.tn (in French). Gouvernorat de Nabeul. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ "Международные и межрегиональные связи". gov.spb.ru (in Russian). Federal city of Saint Petersburg. Archived from the original on 5 January 2018. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ "اتفاقية توأمة بين شرم الشيخ والعقبة". alghad.tv (in Arabic). Al Ghad. 16 December 2015. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2020.

- ^ "Aqaba's twin city Urumchi donates medical equipment for COVID-19 response". adc.jo. Aqaba Development Corporation. 15 April 2020. Archived from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Mayhew, Bradley (April 2006) [1987]. Jordan (6th ed.). Footscray: Lonely Planet. ISBN 1-74059-789-3.

- Government of Jordan, Department of Statistics (1964). First Census of Population and Housing. Volume I: Final Tables; General Characteristics of the Population (PDF).

External links

[edit]Aqaba

View on GrokipediaHistorically, Aqaba—anciently known as Ayla—has served as a strategic port for over 5,500 years, facilitating regional trade from prehistoric times through Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman periods.[5] During World War I, it gained prominence when Arab forces under T.E. Lawrence captured it from Ottoman control in 1917, marking a key victory in the Arab Revolt.[6] Today, Aqaba remains Jordan's primary maritime hub, with its port ranking as the second-largest on the Red Sea, underscoring its enduring role in national and regional connectivity.[3]

Name and Etymology

Historical and Linguistic Origins

The settlement at the northern end of the Gulf of Aqaba was known in ancient Hebrew texts as Elath, a name referring to its location near copper mines and as a regional hub.[7] This designation appears in biblical accounts, such as in the Books of Kings, associating it with King Solomon's maritime activities around the 10th century BCE.[8] Under Roman rule from the 1st century CE, the name evolved to Aela in Latin, reflecting administrative continuity as a key port on trade routes.[9] Byzantine and early Islamic periods preserved variants like Aila, Ailana, or Ayla in Greek, Latin, and Arabic sources, denoting the fortified city established by the 4th century CE.[10] Archaeological evidence from the site confirms continuous occupation under these names, with structures including an early church dated to circa 300 CE and Islamic fortifications from the 7th-8th centuries.[11] The modern name Aqaba derives from Arabic al-ʿaqabah, meaning "the obstacle" or "steep incline," alluding to the rugged mountains encircling the city and the challenging ascent from the coast.[12] This appellation, shortened from Aqabat Aylah ("pass of Ayla"), emerged in the 12th century and became standard during Mamluk rule in the 14th century, when the port's strategic bypass via the mountain pass was emphasized in historical records.[13] The root ʿ-q-b in Semitic languages relates to concepts of following or heel, extending metaphorically to barriers or elevations, consistent with the topography.[14] Prior to this, medieval Arabic texts continued using Ayla for the urban center, highlighting a linguistic shift from the ancient site's designation to a descriptive geographic term.[5]Geography

Location and Physical Features

Aqaba lies at the northeastern extremity of the Red Sea, specifically at the northern terminus of the Gulf of Aqaba, which forms a narrow inlet bounded by the Sinai Peninsula to the west and the Arabian Peninsula to the east.[15] Its geographic coordinates are approximately 29°31′N 35°00′E.[16] As Jordan's sole coastal city, Aqaba provides the kingdom with its only maritime access via a 26-kilometer shoreline along the gulf.[17] The city's position places it adjacent to Israel's Eilat across a short maritime boundary to the west, with Saudi Arabia bordering to the southeast and Egypt's Taba region visible across the gulf waters.[15] The urban area occupies a narrow coastal plain at near sea level, with elevations averaging around 5 to 50 meters above the gulf.[18] Immediately inland, the terrain rises abruptly into arid mountain ranges, including the Aqaba Mountains and extensions of the Edom highlands, where peaks such as Jabal Umm ad Dami reach 1,854 meters, marking Jordan's highest point.[19] These formations, part of the broader Arabah rift system, feature steep wadis, rocky plateaus, and desert scrub vegetation, transitioning into the expansive Badia desert further east.[20] The Gulf of Aqaba, integral to Aqaba's physical setting, is a tectonic rift valley characterized by deep waters—reaching over 1,800 meters in places—and steep, coral-encrusted shores that support diverse marine ecosystems despite the surrounding hyper-arid land.[15] This configuration, resulting from the East African Rift's extension, creates a stark contrast between the enclosed, saline gulf and the rain-shadowed continental interior.[15]Climate and Environmental Setting

Aqaba exhibits a hot desert climate classified as BWh under the Köppen-Geiger system, characterized by extreme aridity, high solar radiation, and significant diurnal temperature variations.[21] [22] Annual precipitation averages approximately 30-36 mm, concentrated in brief winter events, with January recording the highest monthly total of about 7-8 mm; evaporation rates exceed 4,400 mm per year in southern Jordan, far outpacing rainfall and reinforcing desert conditions.[23] [24] Average relative humidity hovers around 26%, contributing to dry air that amplifies heat stress in summer.[23] Temperatures range from winter lows of 10°C (50°F) to summer highs exceeding 39°C (103°F), with August marking the warmest month at an average of 34°C (93°F) and January the coolest at 16°C (61°F); rare extremes dip below 7°C (45°F) or surpass 42°C (108°F).[25] [23] Winds, often from the northwest, average 18 km/h (11 mph), occasionally intensifying into sirocco-like events that elevate dust levels.[23] The environmental setting juxtaposes terrestrial aridity with marine richness. Inland, Aqaba lies in the Syrian-East African Rift, flanked by the Edom Mountains to the east and arid wadis draining into the Gulf of Aqaba, supporting sparse xerophytic vegetation adapted to minimal water availability.[26] The gulf's fringing coral reefs host over 265 coral species and diverse vertebrate and invertebrate biodiversity, forming a biodiversity hotspot sustained by nutrient-poor but warm, clear waters averaging 22-28°C seasonally.[27] These reefs face threats from coastal urbanization, industrial pollution, overfishing, and sedimentation linked to port expansion and population growth, though some species demonstrate resilience to elevated temperatures up to 2-3°C above global averages.[28] [29] Desertification exacerbates dust deposition on reefs, while desalination brine discharge poses localized salinity risks.[30] Conservation efforts, including marine protected areas, aim to mitigate these pressures amid regional economic development.[31]History

Prehistoric Settlements

The earliest evidence of human settlement in the Aqaba region consists of Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age villages located on the alluvial fan of Wadi al-Yutum, north of the modern city. Tall al-Magass and Tall Hujayrat al-Ghuzlan, dating from approximately 4500 to 3000 BCE, represent the oldest known occupations, characterized by mud-brick architecture and specialized copper production.[32][33] These sites indicate adaptation to the arid environment through exploitation of local wadi resources and early metallurgy, with no confirmed Neolithic precursors identified in the immediate area.[34] Excavations at Tall Hujayrat al-Ghuzlan, initiated in the 1990s by the German Archaeological Institute and the University of Jordan's ASEYM project, have uncovered stratified remains spanning the Late Chalcolithic to Early Bronze I periods. Structures include rectangular houses, courtyards, and industrial zones with hearths and smelting facilities, supported by radiocarbon dates calibrating to 4000–3500 BCE for initial phases.[35][36] Artifacts such as incised pottery, basalt vessels, flint implements, and copper slag attest to domestic life, crafting, and proto-urban organization linked to regional trade.[37] Tall al-Magass, adjacent and contemporaneous, yields similar evidence of copper processing, including 6500-year-old smelting residues, highlighting the site's role in early resource extraction from nearby Timna ores.[38] Both settlements demonstrate mobility patterns and long-distance contacts, with material culture showing affinities to northern Levantine Chalcolithic traditions amid southern arid adaptations.[39] Destruction layers at Tall Hujayrat al-Ghuzlan suggest seismic events contributed to abandonment phases, marking transitions in prehistoric occupation.[40]Ancient and Biblical Periods

The region encompassing modern Aqaba was identified in antiquity as Elath (Hebrew: Elot or Elath) and closely linked to the biblical port of Ezion-Geber, situated at the northern terminus of the Gulf of Aqaba in the territory historically associated with Edom.[41] These sites facilitated maritime access to the Red Sea, supporting trade in copper from nearby Arabah mines and exotic goods. Archaeological surveys indicate early Iron Age activity, including Edomite settlements exploiting regional mineral resources, though monumental structures from this era remain elusive.[42] In the Hebrew Bible, Ezion-Geber appears as a encampment during the Israelites' exodus wanderings, listed sequentially with stations like the Wilderness of Zin (Numbers 33:35-36).[43] By the 10th century BCE, under King Solomon (circa 970-931 BCE), Ezion-Geber served as the base for a Phoenician-assisted fleet constructed "beside Eloth on the shore of the Red Sea, in the land of Edom," which undertook voyages to Ophir, returning with 420 talents of gold, almug wood, and precious stones after three years (1 Kings 9:26-28; 2 Chronicles 8:17-18).[44] This enterprise, aided by Hiram I of Tyre's shipwrights, underscores the site's role in early Israelite maritime commerce, though direct archaeological corroboration of the fleet is absent, with interpretations relying on biblical accounts and contextual evidence from Timna Valley copper production.[45] Excavations at Tell el-Kheleifeh, approximately 500 meters northwest of Aqaba, conducted by Nelson Glueck between 1938 and 1940, uncovered an Iron Age II fortified enclosure, smelting installations, and Edomite pottery dated roughly to the 9th-6th centuries BCE, prompting initial identification with Ezion-Geber.[45] Reassessments, including stratigraphic reanalysis, portray the site as a modest industrial outpost or caravanserai rather than a major royal port, lacking evidence of extensive shipbuilding or 10th-century monumental architecture.[45] Israel Finkelstein's 2014 study posits dual active loci in the Iron Age: Tell el-Kheleifeh for metallurgical functions and the precursor to Roman Aila (modern Aqaba) as the principal harbor, aligning biblical Elath with the latter while questioning Glueck's singular attribution.[42] No confirmed 8th-century BCE strata at Tell el-Kheleifeh support biblical notices of Judahite fortification under Azariah (2 Kings 14:22) or subsequent loss to Aram-Damascus under Rezin (2 Kings 16:6).[42] The area's strategic port function persisted into the late Iron Age under Edomite and Judahite influence, evidenced by scarab seals and trade artifacts indicating connections to Egypt and Arabia, though the precise delineation between Ezion-Geber and Elath remains debated among scholars, with some proposing Ezion-Geber as a distinct anchorage east of Elath proper.[41] Biblical texts portray the locales as proximate twins (Deuteronomy 2:8), emphasizing their joint role in regional control rather than discrete urban entities.[46]Classical Antiquity

Aila, the Roman and Byzantine name for the settlement at modern Aqaba, originated as a Nabataean port in response to disruptions in the incense trade routes following Roman control of Egypt in the late 1st century BCE.[47] Nabataean development focused on exploiting the site's position at the northern Gulf of Aqaba for maritime commerce, with evidence of pottery and structures indicating occupation from the 1st century BCE.[48] Roman annexation of the Nabataean kingdom in 106 CE under Emperor Trajan integrated Aila into the province of Arabia Petraea as its southernmost port city.[49] The Romans initiated the Via Nova Traiana from Aila northward to Bostra between 111 and 116 CE, enhancing overland connectivity for trade and military logistics.[50] Aila functioned as a vital emporium, channeling luxury goods like spices, incense, and eastern imports into the Roman economy via Red Sea shipping routes.[51] Archaeological excavations by the Roman Aqaba Project have uncovered harbor infrastructure, including quays and warehouses, supporting its role in sustaining legionary garrisons and facilitating exchange with India and Arabia.[52] In the late Roman period, Aila hosted a purpose-built church constructed between 293 and 303 CE, marking one of the earliest documented Christian basilicas and reflecting the site's growing Christian community amid imperial tolerance under Diocletian.[52] By the 4th century CE, under Byzantine administration from around 300 CE, Aila's strategic port status persisted, with diverse ceramics indicating sustained international trade networks despite regional shifts.[53] The site's fortifications and epigraphic evidence, including inscriptions from legionary units, underscore its military importance in securing the eastern frontier against nomadic incursions.[54]Early Islamic Era

The early Islamic settlement at Aqaba, known as Ayla, emerged following the Muslim conquest of the Byzantine port city of Aila around 650 AD during the caliphate of Uthman ibn Affan.[50] This new foundation was established as a miṣr, a fortified garrison town typical of early Islamic urban planning, positioned adjacent to the decaying Byzantine settlement to the south.[55] Archaeological evidence indicates a deliberate layout with axial streets, defensive walls enclosing an area of approximately 70 hectares, and structures including administrative buildings and residential quarters, reflecting organized military and civilian settlement.[56] Central to Ayla was the construction of an early congregational mosque, dated to the mid-7th century, which served as a hub for religious, judicial, and educational activities.[57] Excavations reveal the mosque's initial phase (ca. 650–750 AD) featured deep column foundations and Umayyad-era artifacts, with later expansions under the Umayyads altering its orientation and scale to align with evolving architectural norms.[50] The site's ceramics and coins from this Rashidun-to-Umayyad transition confirm continuous occupation and trade links, positioning Ayla as a key Red Sea port facilitating commerce between the Arabian Peninsula, Egypt, and beyond.[58] Ayla's strategic maritime role amplified during the Umayyad period (661–750 AD), with evidence of shipbuilding and port infrastructure supporting naval expeditions and pilgrimage routes.[59] However, the city suffered significant damage from an earthquake in 748 AD, which disrupted structures including the mosque and walls, though reconstruction followed under Abbasid oversight.[59] These developments underscore Ayla's transition from a conquest outpost to a prosperous entrepôt, bolstered by its location at the Gulf of Aqaba's northern terminus.[60]Medieval and Ottoman Periods

Following the Crusader capture of Ayla in 1116 AD during the reign of Baldwin I of Jerusalem, the city's inhabitants largely abandoned the site, relocating to a new settlement further south that formed the basis of modern Aqaba.[50][61] The early Islamic urban center, established around 650 AD, thus ended after approximately 450 years, exacerbated by prior damage from the 1068 AD earthquake.[50][48] Crusader control integrated Ayla into the Lordship of Transjordan, with fortifications including castles on the nearby island of Jazirat Fara'un, but the mainland site saw no significant rebuilding.[62][63] This hold persisted until approximately 1189 AD, after which Ayyubid forces under Saladin reasserted Muslim dominance in the region, though archaeological evidence indicates minimal redevelopment of the abandoned Ayla.[62] Under subsequent Mamluk rule from the 13th century, Aqaba's strategic Red Sea position prompted defensive measures, culminating in the construction of a fortress by Sultan Qansuh al-Ghuri between 1510 and 1517 AD to safeguard pilgrimage and trade routes.[64] This structure, built inland near the new settlement, replaced earlier island defenses and symbolized Mamluk efforts to secure the gulf approaches amid declining regional commerce.[65] The Ottoman Empire incorporated Aqaba in 1517 AD following their defeat of the Mamluks, administering it as a minor garrison post within the Eyalet of Damascus.[65] The fortress functioned primarily as a military outpost, with the town evolving into a modest fishing village overshadowed by silting sands and bypassed trade paths.[58] Pilgrim traffic, once vital via the gulf, waned as overland routes to Mecca gained precedence, contributing to Aqaba's stagnation as a peripheral Ottoman holding until the 19th century.[58] By the early 20th century, the population numbered only a few hundred, centered around subsistence activities rather than commerce.[58]Modern Development and Independence

Following the successful Arab assault on Aqaba in July 1917, led by forces under T. E. Lawrence and Faisal bin Hussein during the Arab Revolt against Ottoman rule, the port fell to British and Arab control.[6] The city was subsequently integrated into the Emirate of Transjordan, established in 1921 east of the Jordan River under British Mandate administration with Abdullah bin Hussein as emir. Transjordan secured formal independence via the Anglo-Transjordanian Treaty signed on March 22, 1946, which terminated the mandate, followed by the proclamation of the Hashemite Kingdom of Transjordan on May 25, 1946; Aqaba, as the emirate's—and later kingdom's—only Red Sea access point, underscored its strategic maritime significance from inception.[66] The 1948 Arab-Israeli War resulted in Jordan's loss of Mediterranean outlets like Haifa and Jaffa, compelling reliance on Aqaba as the principal gateway for imports and exports. This shift prompted accelerated port infrastructure initiatives, including the first development blueprint in 1952, informed by trade data from 1948–1951 projecting needs for general cargo, phosphates, and potash handling. Formal establishment of the port via royal decree occurred in 1952, with initial berths and warehouses constructed to accommodate growing volumes, marking Aqaba's transition from a minor anchorage to Jordan's core commercial harbor.[67][68][69] A pivotal boundary accord with Saudi Arabia, ratified on August 9, 1965, redefined the southern frontier, ceding Jordanian desert territories inland while acquiring approximately 19 kilometers of additional Gulf of Aqaba shoreline south of Aqaba, thereby extending maritime access and enabling resort and port expansions.[70] This adjustment facilitated subsequent modernization, culminating in the 2001 launch of the Aqaba Special Economic Zone (ASEZ) under Law No. 32 of 2000, which introduced tax exemptions, streamlined regulations, and investment incentives to catalyze trade, logistics, tourism, and industrial growth, propelling Aqaba's population and GDP contributions amid regional diversification efforts.[71][72]Strategic and Geopolitical Role

Regional Position and Borders

Aqaba occupies the northeastern tip of the Gulf of Aqaba, an inlet of the Red Sea, at coordinates 29°31′N 35°00′E.[73] This positioning places it as Jordan's southernmost city and the country's only coastal outlet, with Jordan's total Red Sea coastline spanning 26 kilometers.[74] The gulf itself extends approximately 160 kilometers southward, varying in width from 12 to 17 miles, and forms a critical maritime corridor linking the Mediterranean via the Suez Canal to the Indian Ocean.[75] The Aqaba region's land borders align with Jordan's southwestern frontiers: to the west lies Israel, with the border commencing at the gulf's head near the Wadi Araba Border Crossing, which connects Aqaba to Eilat and facilitates trade and tourism since its establishment following the 1994 Israel-Jordan peace treaty.[73] To the south and east, Saudi Arabia borders Aqaba along a segment of the 731-kilometer Jordan-Saudi Arabia boundary, including access points like the Durra crossing for regional connectivity.[76] Jordan shares no direct land border with Egypt in this area; Egypt's Sinai Peninsula borders the gulf further west, opposite Israeli territory, resulting in shared maritime zones rather than terrestrial adjacency.[77] This configuration positions Aqaba at the convergence of four national territories—Jordan, Israel, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia—creating a strategically compact zone where maritime boundaries delineate overlapping interests in navigation and resources.[78] The short Jordanian coastline, measuring about 25 kilometers between Israeli and Saudi borders, underscores Aqaba's role as a focal point for regional geopolitics, with historical delimitations avoiding a precise quadripoint on land.[79]Military and Diplomatic Significance

Aqaba's military significance dates to World War I, when Arab forces under Sherif Nasir ibn Ali and Auda abu Tayi, advised by T.E. Lawrence, captured the port from the Ottoman Empire on July 6, 1917, following a surprise overland attack across the Sinai Peninsula.[80] This victory, achieved without significant naval support, opened a vital supply route for the Arab Revolt and British advances into Palestine, marking a turning point in the campaign against Ottoman control in the region.[81] In the modern era, Aqaba hosts the Royal Jordanian Navy's primary base, leveraging Jordan's limited 26-kilometer coastline along the Gulf of Aqaba as its only maritime access to the Red Sea.[82] Established with a specialized boat platoon in 1957 and relocated to the Gulf in 1967, the base supports naval operations, including joint exercises with allies such as the U.S. Navy's Infinite Defender in September 2025, enhancing maritime security and interoperability in the Red Sea.[83] Diplomatically, Aqaba's position at the northern tip of the Gulf of Aqaba amplifies its role in regional agreements, particularly the Israel-Jordan peace treaty signed on October 26, 1994, which designated the Gulf as an international waterway ensuring unimpeded navigation for both nations.[84] The treaty delineated maritime boundaries between Aqaba and Israel's Eilat, resolving disputes and enabling security cooperation amid shared vulnerabilities in the Red Sea corridor.[85] This framework has facilitated bilateral initiatives, including naval coordination and economic ties, underscoring Aqaba's importance in stabilizing Jordan's access to global trade routes.[86]Economy

Aqaba Special Economic Zone Framework

The Aqaba Special Economic Zone (ASEZ) was established pursuant to Jordan's Law No. 32 of 2000, with formal operations launching in 2001 to transform the city into a hub for trade, investment, and sustainable development.[87] [88] The law delineates the zone's boundaries via a Council of Ministers decision, informed by recommendations from the overseeing authority, encompassing Aqaba's core urban, port, and industrial areas while allowing amendments for public interest or operational needs.[87] Core objectives focus on attracting foreign direct investment, expanding export-oriented industries, enhancing logistics and tourism infrastructure, and integrating Aqaba into global markets, all while prioritizing environmental safeguards and economic diversification.[89] [90] The Aqaba Special Economic Zone Authority (ASEZA) administers the framework as an independent public entity, empowered to promulgate specialized regulations on customs procedures, land use, investment approvals, and ecological standards, exempt from Jordan's general investment law provisions.[89] [90] Governance operates through a six-member Board of Commissioners, chaired by a designated leader, which oversees policy formulation, regulatory enforcement, and strategic planning, supported by subsidiaries like the Aqaba Development Corporation for one-stop investor services.[89] This structure enables rapid decision-making, including automated customs via ASYCUDA systems and a four-step online registration process for businesses, minimizing bureaucratic delays.[88] Incentives under the framework include a flat 5% income tax on net profits for zone-registered entities, zero percent sales tax on most goods and services, full exemptions from income tax on transit and re-exported merchandise, and waivers on customs duties for raw materials processed within the zone for export.[88] [91] Additional measures encompass 40-50% discounts on port handling fees for transit and export cargo, unrestricted foreign equity ownership, allowances for up to 70% expatriate labor in workforce compositions, and five-year renewable residency permits for non-Jordanians investing JD 100,000 or more in residential property, including duty-free imports of household goods and vehicles.[88] These provisions, combined with public-private partnership models like build-operate-transfer schemes, have facilitated over USD 26 billion in pledged investments since 2001.[88]Port Operations and International Trade

The Aqaba Port serves as Jordan's sole maritime gateway, facilitating the majority of the country's imports and exports while also handling transit cargo for landlocked neighbors such as Iraq and Syria.[92] Operated by the Aqaba Ports Corporation under the Aqaba Special Economic Zone Authority (ASEZA), the port encompasses specialized facilities including the Aqaba Container Terminal (ACT), managed by APM Terminals, alongside bulk cargo terminals for phosphates and potash, general cargo berths, and roll-on/roll-off (Ro-Ro) operations for vehicles.[93] In 2024, the port processed 824,199 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) of containers, reflecting an 8.29% decline from 2023 amid regional disruptions, yet achieved a 43% increase in vessel calls to 494 ships.[94] Container operations at ACT demonstrated resilience and growth in 2025, with throughput reaching a record 94,541 TEUs in September, surpassing the prior monthly high of 92,348 TEUs set in May.[95] From January to September 2025, inbound containers totaled 370,608 TEUs, a rise from 313,808 TEUs in the same period of 2024, while overall container traffic grew 19%, driven by heightened regional demand and transit volumes that nearly tripled their share despite Red Sea tensions.[96][97] Exports increased by 5.7% over the period, supporting Jordan's key shipments of apparel and agricultural products.[96] Bulk cargo handling underscores the port's role in Jordan's mineral exports, with phosphate shipments reaching 4.36 million tons and potash 1.59 million tons through mid-2025, alongside 448,152 tons of iron exports.[98] Imports primarily consist of consumer goods, machinery, and petroleum derivatives, with vehicle imports and exports surging 81.8% in early 2025 due to demand from neighboring markets.[99] The port's strategic incentives under ASEZA, including tax exemptions and streamlined customs, position Aqaba as a regional transshipment hub, though vulnerabilities to geopolitical events like Red Sea blockades highlight dependencies on alternative routing via the Gulf of Aqaba.[100] Jordan's broader trade flows through Aqaba favor exports to the United States ($3.11 billion), India ($1.93 billion), and Saudi Arabia ($1.77 billion), with imports dominated by China and the US.[101]Tourism and Hospitality Sector

Aqaba's tourism sector primarily revolves around its 27-kilometer Red Sea coastline, which supports scuba diving, snorkeling, and beach activities amid coral reefs and marine biodiversity. The Gulf of Aqaba's clear waters host dive sites including shipwrecks like the Cedar Pride and reef formations such as the Japanese Garden, drawing enthusiasts for year-round accessibility due to stable water temperatures.[102] The hospitality industry has expanded through incentives in the Aqaba Special Economic Zone, which has secured over USD 20 billion in committed investments, largely directed toward real estate and tourism projects.[88] These include mixed-use developments like Saraya Aqaba, featuring four 5-star hotels, residential units, and conference facilities as part of a USD 1.5 billion initiative.[3] Hotel capacity growth targets increasing rooms from approximately 4,650 to 12,000, enhancing accommodation options for international visitors.[103] Recent international financing underscores ongoing development, with the International Finance Corporation providing a USD 35.5 million loan in July 2024 to Ayla Oasis Development Company for Marina Village expansion, aimed at unlocking tourism potential and job creation.[104] Similarly, 2024 investments from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, IFC, and Jordan's Central Bank support the Pulse hotel construction and sustainable enhancements to Ayla Marina Village.[105] Peak season occupancy has hit 95% of permitted capacity, as during Eid al-Fitr 2021, reflecting demand surges.[106] Aqaba contributes to Jordan's national tourism recovery, where visitor arrivals reached 3.29 million in the first half of 2025, an 18% increase from 2024, bolstered by new air links and hotel additions.[107] Efforts include nominating the Aqaba Marine Reserve for UNESCO World Heritage status to promote conservation alongside tourism.[108] The sector benefits from SEZ policies like 50% exemptions on transport licenses in 2025, facilitating visitor mobility.[109]Industrial and Digital Initiatives

The Aqaba Special Economic Zone (ASEZ) hosts several industrial initiatives aimed at fostering manufacturing and logistics. The Aqaba International Industrial Estate (AIIE), spanning key areas for production and storage, attracts over 100 investors focused on sectors including metalworking, renewable energy components, food processing, garments, and plastics manufacturing.[3] [110] This estate benefits from ASEZ incentives such as duty-free imports and a flat 5% corporate tax rate, positioning it as a hub for light and medium industries.[111] The Southern Industrial Zone, adjacent to port facilities, supports expanded sites for industrial operations and transportation infrastructure.[112] Key projects include the Jordan Phosphate Mines Company's industrial complex in Aqaba, which features a fourth phosphoric acid concentration line to enhance phosphate processing capacity.[113] In August 2025, construction began on an integrated industrial complex in ASEZ and the nearby Sheidiya area, designed to consolidate manufacturing, warehousing, and support services.[114] These developments leverage Aqaba's strategic location for export-oriented production, with Qualified Industrial Cities providing allocated land for such activities.[112] Digital initiatives in Aqaba emphasize connectivity and innovation. The Aqaba Digital Hub (ADH), launched on October 22, 2025, serves as a gateway for digital transformation, featuring AI-ready infrastructure and Tier III data centers to link regional and global networks via Jordan's Red Sea access.[115] [116] Complementing this, Aqaba Digital City enhances national cybersecurity and data protection standards, positioning Jordan among leaders in secure digital environments.[117] In September 2025, ASEZ introduced an esports strategy to draw investments into the digital and creative economy, aiming to establish Aqaba as a regional center for gaming and related technologies.[118] These efforts align with broader national goals for digital economy growth, supported by high internet penetration and youth-driven tech adoption.[119]Governance and Administration

Local Government Structure

The local government of Aqaba is administered by the Aqaba Special Economic Zone Authority (ASEZA), a financially and administratively autonomous institution established in 2001 under Jordan's Aqaba Special Economic Zone Law No. 32 of 2000, which empowers it to manage, regulate, and operate the zone while functioning as the de facto municipality.[89][120] ASEZA handles integrated services including urban planning, public works, investment promotion, tourism development, and city services, subsuming traditional municipal roles within the special economic zone that encompasses the city.[89][121] At the core of ASEZA's governance is the Board of Commissioners, which oversees strategic direction, policy formulation, and regulatory enforcement, with members including ministerial-level commissioners responsible for key operational areas such as economic development and infrastructure.[122] The Chairman leads the Board and chairs the Planning, Coordination, and Follow-Up Committee, which convenes monthly to review development plans, budgets, and regulatory compliance, while the Vice Chairman supervises designated directorates as assigned by the Board.[122][121] ASEZA's operational structure comprises 23 directorates—covering sectors like investment, tourism, customs, environment, and city services—and four specialized units for internal control, legal affairs, and related functions, enabling comprehensive local administration tailored to Aqaba's economic priorities.[121] Specialized ad hoc committees may be formed by the Board for targeted issues, ensuring flexible governance, though ultimate authority resides with the Board issuing implementation instructions based on the Chairman's recommendations.[121] This framework operates independently under the Prime Minister, distinguishing Aqaba from standard Jordanian municipalities governed by the 2015 Municipalities Law, which applies elsewhere but is overridden by ASEZA's mandate in the zone.[120][89]Administrative Divisions and Policies