Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

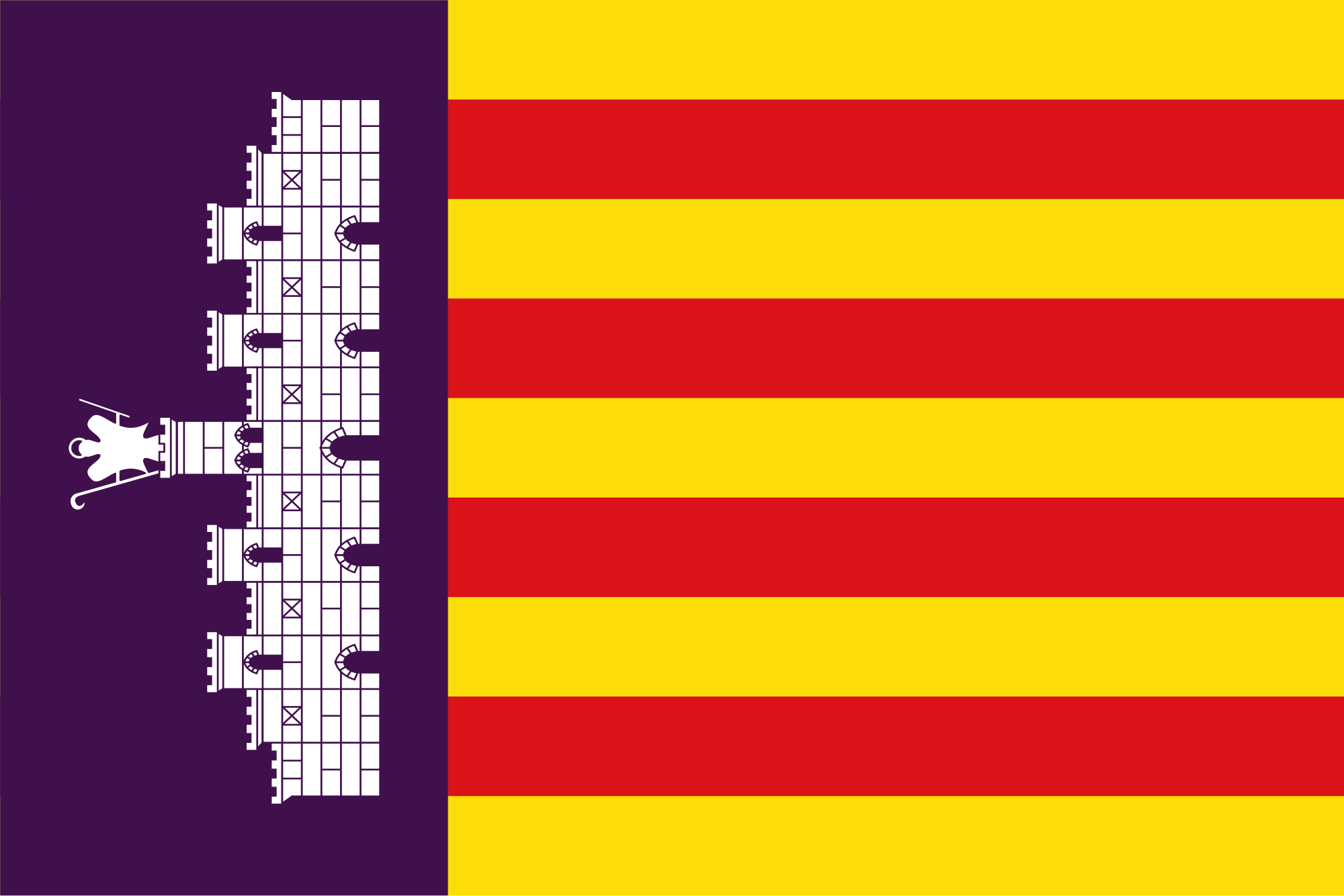

Mallorca

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Carthage 4th century BC – 201 BC

Roman Republic 123–27 BC

- Roman Empire 27 BC – 455 AD

- Vandal Kingdom 455–534

- Byzantine Empire 534–903

- Umayyad state of Córdoba 903–1015

- Taifa of Dénia 1015–1076

- Taifa of Majorca 1076–1115

- Almoravid dynasty 1115–1158

- Taifa of Majorca 1158–1203

- Almohad Caliphate 1203–1229

Crown of Aragon 1229–1276

Kingdom of Mallorca 1276–1343

Crown of Aragon 1343–1715

Kingdom of Spain 1715–1808

Kingdom of Spain 1813–1931

Second Spanish Republic 1931–1936

Spanish State 1936–1978

Spain 1978–present

Balearic Islands 1983–present

Mallorca,[a] also spelled Majorca in English,[b][2][3] is the largest of Spain's Balearic Islands, and the seventh largest island in the Mediterranean Sea.

Its capital, Palma, is also the capital of the autonomous community of the Balearic Islands. The Balearic Islands have been an autonomous region of Spain since 1983.[4] Two smaller islands lie just off the coast of Mallorca: Cabrera (southeast of Palma) and Dragonera (west of Palma). The island's anthem is "La Balanguera".

Along with other Balearic Islands, Menorca, Ibiza, and Formentera, Mallorca is a highly popular holiday destination, particularly for tourists from the Netherlands, Ireland, Germany, and the United Kingdom. The international airport, Palma de Mallorca Airport, is one of the busiest in Spain; it was used by 28 million passengers in 2017, with use increasing every year between 2012 and 2017.[5]

Etymology

[edit]The name derives from Classical Latin insula maior, "larger island". Later, in Medieval Latin, this became Maiorca, "the larger one", in comparison to Menorca, "the smaller one". This was then hypercorrected to Mallorca by central Catalan scribes, which later came to be accepted as the standard spelling.[6]

History

[edit]Prehistoric settlements

[edit]

The Balearic Islands were first colonised by humans during the 3rd millennium BC, around 2500–2300 BC from the Iberian Peninsula or southern France, by people associated with the Bell Beaker culture.[8][9] The arrival of humans resulted in the rapid extinction of the three species of terrestrial mammals native to Mallorca, the dwarf goat-antelope Myotragus balearicus, the giant dormouse Hypnomys morpheus, and the shrew Nesiotites hidalgo, all three of which had been continuously present on Mallorca for over 5 million years.[10] The island's prehistoric settlements are called talaiots or talayots. The people of the islands raised Bronze Age megaliths as part of their Talaiotic culture.[11] A non-exhaustive list of settlements is the following:

- Capocorb Vell (Llucmajor municipality)

- Necròpoli de Son Real (east of Can Picafort, Santa Margalida municipality)

- Novetiforme Alemany (Magaluffa, Calvià, Miconio)

- Poblat Talaiòtic de S'Illot (S'Illot, Sant Llorenç des Cardassar municipality)

- Poblat Talaiòtic de Son Fornés (Montuïri municipality)

- Sa Canova de Morell (road to Colònia de Sant Pere, Artà municipality)

- Ses Païsses (Artà municipality)

- Ses Talaies de Can Jordi (Santanyí municipality)

- S'Hospitalet Vell (road to Cales de Mallorca, Manacor municipality)

Phoenicians, Romans, and Late Antiquity

[edit]

The Phoenicians, a seafaring people from the Levant, arrived around the eighth century BC and established numerous colonies.[12] The island eventually came under the control of Carthage in North Africa, which had become the principal Phoenician city. After the Second Punic War, Carthage lost all of its overseas possessions and the Romans took over.[13]

The island was occupied by the Romans in 123 BC under Quintus Caecilius Metellus Balearicus. It flourished under Roman rule, during which time the towns of Pollentia (Alcúdia), and Palmaria (Palma) were founded. In addition, the northern town of Bocchoris, dating back to pre-Roman times, was a federated city to Rome.[14] The local economy was largely driven by olive cultivation, viticulture, and salt mining. Mallorcan soldiers were valued within the Roman legions for their skill with the sling (Balearic slingers).[15]

In 427, Gunderic and the Vandals captured the island. Geiseric, son of Gunderic, governed Mallorca and used it as his base to loot and plunder settlements around the Mediterranean[16] until Roman rule was restored in 465.

Middle Ages

[edit]Late Antiquity and Early Middle Ages

[edit]In 534, Mallorca was recaptured from the Vandals by the Eastern Roman Empire, led by Apollinarius. Under Roman rule, Christianity thrived and numerous churches were built.

From 707, the island was increasingly attacked by Muslim raiders from North Africa. Recurrent invasions led the islanders to ask Charlemagne for help.[16]

Islamic Mallorca

[edit]

In 902, Issam al-Khawlani(es)(ca) (Arabic: عصام الخولاني) conquered the Balearic Islands, and they became part of the Emirate of Córdoba. The town of Palma was reshaped and expanded, and became known as Medina Mayurqa. Later on, with the Caliphate of Córdoba at its height, the Muslims improved agriculture with irrigation and developed local industries.

The caliphate was dismembered in 1015. Mallorca came under rule by the Taifa of Dénia, and from 1087 to 1114, was an independent Taifa. During that period, the island was visited by Ibn Hazm. However, an expedition of Pisans and Catalans in 1114–15, led by Ramon Berenguer III, Count of Barcelona, overran the island, laying siege to Palma for eight months. After the city fell, the invaders retreated due to problems in their own lands. They were replaced by the Almoravides from North Africa, who ruled until 1176. The Almoravides were replaced by the Almohad dynasty until 1229. Abu Yahya was the last Moorish leader of Mallorca.[17]

Medieval Mallorca

[edit]In the ensuing confusion and unrest, King James I of Aragon, also known as James the Conqueror, launched an invasion which landed at Santa Ponça, Mallorca, on 8–9 September 1229 with Catalan forces consisting of 15,000 men and 1,500 horses. His forces entered the city of Medina Mayurqa on 31 December 1229. In 1230, he annexed the island to his Crown of Aragon under the name Regnum Maioricae.

Modern era

[edit]

From 1479, the Crown of Aragon was in dynastic union with that of Castile. The Barbary corsairs of North Africa often attacked the Balearic Islands, and in response, the people built coastal watchtowers and fortified churches. In 1570, King Philip II of Spain and his advisors were considering complete evacuation of the Balearic islands.[18]

In the early 18th century, the War of the Spanish Succession resulted in the replacement of that dynastic union with a unified Spanish monarchy under the rule of the new Bourbon Dynasty. The last episode of the War of Spanish Succession was the conquest of the island of Mallorca. It took place on 2 July 1715 when the island capitulated to the arrival of a Bourbon fleet. In 1716, the Nueva Planta decrees made Mallorca part of the Spanish province of Baleares, roughly the same to present-day Illes Balears province and autonomous community.

20th century and today

[edit]A Nationalist stronghold at the start of the Spanish Civil War, Mallorca was subjected to an amphibious landing, on 16 August 1936, aimed at driving the Nationalists from Mallorca and reclaiming the island for the Republic. Although the Republicans heavily outnumbered their opponents and managed to push 12 km (7.5 mi) inland, superior Nationalist air power, provided mainly by Fascist Italy as part of the Italian occupation of Majorca, forced the Republicans to retreat and to leave the island completely by 12 September. Those events became known as the Battle of Majorca.[19]

Since the 1950s, the advent of mass tourism has transformed the island into a destination for foreign visitors and attracted many service workers from mainland Spain. The boom in tourism caused Palma to grow significantly.

In the 21st century, urban redevelopment, under the so‑called Pla Mirall (English "Mirror Plan"), attracted groups of immigrant workers from outside the European Union, especially from Africa and South America.[20]

Archaeology

[edit]In September 2019, A 3,200-year-old well-preserved Bronze Age sword was discovered by archaeologists under the leadership of Jaume Deya and Pablo Galera on the Mallorca Island in the Puigpunyent from the stone megaliths site called Talaiot.[21] Specialists assumed that the weapon was made when the Talaiotic culture was in critical decline. The sword will be on display at the nearby Majorca Museum.[22]

Palma

[edit]The capital of Mallorca, Palma, was founded as a Roman camp called Palmaria upon the remains of a Talaiotic settlement. The turbulent history of the city had it subject to several Vandal sackings during the fall of the Western Roman Empire. It was later reconquered by the Byzantines, established by the Moors (who called it Medina Mayurqa), and finally occupied by James I of Aragon. In 1983, Palma became the capital of the autonomous region of the Balearic Islands. Palma has a famous tourist attraction, the cathedral, Catedral-Basílica de Santa María de Mallorca, standing in the heart of the City looking out over the sea.[23]

Climate

[edit]Mallorca has a Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csa), with mild and relatively wet winters and hot, bright, dry summers. Precipitation in the Serra de Tramuntana is markedly higher. Summers are hot in the plains, and winters are mild, getting colder and wetter in the Tramuntana range, where brief episodes of snow during the winter are not unusual, especially in the Puig Major. The two wettest months in Mallorca are October and November. Storms and heavy rain are not uncommon during the autumn.[24]

| Climate data for Palma de Mallorca, Port (1991–2020), extremes since 1978 (Satellite view) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 24.2 (75.6) |

24.4 (75.9) |

26.6 (79.9) |

28.0 (82.4) |

32.0 (89.6) |

36.5 (97.7) |

38.0 (100.4) |

37.8 (100.0) |

35.5 (95.9) |

31.2 (88.2) |

27.6 (81.7) |

23.4 (74.1) |

38.0 (100.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 16.5 (61.7) |

16.5 (61.7) |

18.3 (64.9) |

20.3 (68.5) |

23.5 (74.3) |

27.3 (81.1) |

29.9 (85.8) |

30.4 (86.7) |

27.8 (82.0) |

24.4 (75.9) |

20.1 (68.2) |

18.3 (64.9) |

22.8 (73.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.7 (54.9) |

12.6 (54.7) |

14.3 (57.7) |

16.4 (61.5) |

19.5 (67.1) |

23.3 (73.9) |

26.0 (78.8) |

26.6 (79.9) |

23.8 (74.8) |

20.6 (69.1) |

16.3 (61.3) |

13.8 (56.8) |

18.8 (65.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 8.9 (48.0) |

8.7 (47.7) |

10.2 (50.4) |

12.4 (54.3) |

15.5 (59.9) |

19.3 (66.7) |

22.1 (71.8) |

22.7 (72.9) |

20.0 (68.0) |

16.8 (62.2) |

12.6 (54.7) |

10.1 (50.2) |

14.9 (58.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 0.0 (32.0) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

1.6 (34.9) |

4.4 (39.9) |

8.0 (46.4) |

11.0 (51.8) |

16.4 (61.5) |

15.8 (60.4) |

10.0 (50.0) |

8.4 (47.1) |

3.8 (38.8) |

2.5 (36.5) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 44.4 (1.75) |

36.7 (1.44) |

29.1 (1.15) |

37.5 (1.48) |

31.6 (1.24) |

13.9 (0.55) |

5.1 (0.20) |

21.7 (0.85) |

58.2 (2.29) |

72.6 (2.86) |

67.8 (2.67) |

49.3 (1.94) |

467.9 (18.42) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 6.2 | 5.9 | 4.6 | 4.7 | 3.1 | 1.9 | 0.6 | 1.8 | 5.3 | 6.3 | 7.2 | 5.9 | 53.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 170 | 176 | 218 | 250 | 300 | 329 | 356 | 323 | 238 | 211 | 165 | 157 | 2,893 |

| Source 1: NOAA[25] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: AEMET[26] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Palma de Mallorca Airport (1991–2020), extremes since 1954 (Satellite view) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.5 (72.5) |

24.0 (75.2) |

28.6 (83.5) |

30.1 (86.2) |

35.0 (95.0) |

41.4 (106.5) |

40.6 (105.1) |

40.2 (104.4) |

38.2 (100.8) |

33.6 (92.5) |

27.2 (81.0) |

23.8 (74.8) |

41.4 (106.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 15.8 (60.4) |

15.9 (60.6) |

18.2 (64.8) |

20.7 (69.3) |

24.4 (75.9) |

28.7 (83.7) |

31.6 (88.9) |

31.8 (89.2) |

28.2 (82.8) |

24.3 (75.7) |

19.4 (66.9) |

16.8 (62.2) |

23.0 (73.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.3 (50.5) |

10.3 (50.5) |

12.2 (54.0) |

14.6 (58.3) |

18.3 (64.9) |

22.4 (72.3) |

25.3 (77.5) |

25.7 (78.3) |

22.6 (72.7) |

18.9 (66.0) |

14.2 (57.6) |

11.5 (52.7) |

17.2 (62.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 4.7 (40.5) |

4.7 (40.5) |

6.2 (43.2) |

8.6 (47.5) |

12.1 (53.8) |

16.1 (61.0) |

19.0 (66.2) |

19.7 (67.5) |

17.0 (62.6) |

13.6 (56.5) |

9.0 (48.2) |

6.2 (43.2) |

11.4 (52.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −6.0 (21.2) |

−10.0 (14.0) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

1.6 (34.9) |

6.0 (42.8) |

11.0 (51.8) |

10.8 (51.4) |

5.6 (42.1) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

−10.0 (14.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 40.0 (1.57) |

32.4 (1.28) |

23.1 (0.91) |

32.3 (1.27) |

28.5 (1.12) |

13.3 (0.52) |

3.7 (0.15) |

16.2 (0.64) |

56.9 (2.24) |

67.0 (2.64) |

61.7 (2.43) |

46.9 (1.85) |

422 (16.62) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 6.0 | 5.3 | 4.1 | 4.4 | 3.3 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 1.7 | 5.1 | 6.0 | 6.7 | 5.8 | 50.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 160 | 168 | 212 | 246 | 292 | 325 | 349 | 317 | 231 | 202 | 159 | 150 | 2,811 |

| Source 1: NOAA[27] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: AEMET[28] | |||||||||||||

| Palma de Mallorca sea temperature | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °C (°F) | 14.4 (57.9) |

13.9 (57.0) |

14.1 (57.4) |

15.9 (60.7) |

18.9 (66.1) |

22.5 (72.5) |

24.9 (76.7) |

26.0 (78.8) |

25.0 (77.1) |

22.7 (72.9) |

19.7 (67.4) |

16.3 (61.4) |

19.5 (67.2) |

| Mean daily daylight hours | 10.0 | 11.0 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 14.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 14.0 | 12.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 12.2 |

| Average Ultraviolet index | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 5.3 |

| Source: seatemperature.org[29] | |||||||||||||

| Source: Weather Atlas[30] | |||||||||||||

Geography

[edit]

Geology

[edit]Mallorca and the other Balearic Islands are geologically an extension of the fold mountains of the Betic Cordillera of Andalusia. They consist primarily of sediments deposited in the Tethys Sea during the Mesozoic era. These marine deposits have given rise to calcareous rocks which are often fossiliferous. The folding of the Betic Cordillera and Mallorcan ranges resulted from subduction of the African Plate beneath the Eurasian Plate with eventual collision.[31] Tectonic movements led to different elevation and lowering zones in the late Tertiary, which is why the connection to the mainland has been severed at the current sea level.

The limestones, which predominate throughout Mallorca, are readily water-soluble, and have given rise to extensive areas of karst. In addition to limestone, dolomitic rocks are mainly present in the mountainous regions of Mallorca; the Serra de Tramuntana and the Serres de Llevant. The Serres de Llevant also contain marl, the more rapid erosion of which has resulted in the lower elevations of the island's southeastern mountains. Marl is limestone with a high proportion of clay minerals. The eroded material was washed into the sea or deposited in the interior of the island of the Pla de Mallorca, bright marls in the north-east of the island and ferrous clays in the middle of Mallorca, which gives the soil its characteristic reddish colour.[32]

Mountains of Mallorca

[edit]Mallorca features a landscape characterised by a series of mountain ranges. The highest peak, Puig Major, stands at approximately 1,445 meters (4,741 feet) above sea level.[33] Other notable peaks include Puig de Massanella, Puig Tomir, Puig de l'Ofre, and Puig des Teix, all exceeding 1,000 meters (3,280 feet) in elevation.[34] These mountains are part of the Serra de Tramuntana range with numerous peaks over 1,000 meters, offering opportunities for hiking and exploration with views of the Mediterranean. While not towering in comparison to some mountain ranges globally, the Mallorcan mountains provide visitors with diverse outdoor experiences and panoramic views of the island's rugged terrain and coastline.

Ten tallest mountains of Mallorca

[edit]| Mountain Name | Meters | Feet |

|---|---|---|

| Puig Major | 1,445 | 4,741 |

| Puig de Massanella | 1,364 | 4,475 |

| Puig Tomir | 1,103 | 3,619 |

| Puig de l'Ofre | 1,091 | 3,579 |

| Puig des Teix | 1,064 | 3,491 |

| Serra de Tramuntana (Various Peaks) | Over 1,000 | Over 3,280 |

| Puig de Galatzó | 1,027 | 3,369 |

| Puig de sa Rateta | 1,117 | 3,301 |

| Puig de sa Font | 1045 | 3,264 |

| Puig d'en Galileu | 1115 | 3,100 |

Regions

[edit]

Mallorca is the largest island of Spain by area and second most populated (after Tenerife in the Canary Islands).[35][36] Mallorca has two mountainous regions, the Serra de Tramuntana and Serres de Llevant. Both are about 70 km (43 mi) in length and occupy the northwestern and eastern parts of the island respectively.

The highest peak in Mallorca is Puig Major, at 1,445 m (4,741 ft), in the Serra de Tramuntana.[37] As this is a military zone, the neighbouring peak at Puig de Massanella is the highest accessible peak at 1,364 m (4,475 ft). The northeast coast comprises two bays: the Badia de Pollença and the larger Badia d'Alcúdia.

The northern coast is rugged and has many cliffs. The central zone, extending from Palma, is a generally flat, fertile plain known as Es Pla. The island has a variety of caves both above and below the sea – two of the caves, the above sea level Coves dels Hams and the Coves del Drach, also contain underground lakes and are open to tours. Both are located near the eastern coastal town of Porto Cristo. Small uninhabited islands lie off the southern and western coasts; the Cabrera Archipelago is administratively grouped with Mallorca (in the municipality of Palma), while Dragonara is administratively included in the municipality of Andratx. Other notable areas include the Alfabia Mountains, Es Cornadors and Cap de Formentor. The Cap de Formentor is one of the places where the tourists can enjoy the pleasure of its beach which is golden and very thin.[38]

World Heritage Site

[edit]The Cultural Landscape of the Serra de Tramuntana was registered as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2011.[39]

Municipalities

[edit]

The island (including the small offshore islands of Cabrera and Dragonera) is administratively divided into 53 municipalities. The areas and populations of the municipalities (according to the Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Spain) are:

| Municipality | Area (km2) |

Census Population 1 November 2001 |

Census Population 1 November 2011 |

Census Population 1 January 2021 |

Estimated Population 1 January 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alaró | 45.7 | 4,050 | 5,273 | 5,800 | 5,948 |

| Alcúdia | 60.0 | 12,500 | 18,914 | 20,694 | 21,725 |

| Algaida | 89.8 | 3,749 | 5,272 | 6,013 | 6,230 |

| Andratx | 81.5 | 7,753 | 11,234 | 11,780 | 12,096 |

| Ariany | 23.1 | 766 | 892 | 906 | 976 |

| Artà | 139.8 | 6,176 | 7,562 | 8,180 | 8,324 |

| Banyalbufar | 18.1 | 517 | 559 | 541 | 578 |

| Binissalem | 29.8 | 5,166 | 7,640 | 8,931 | 9,225 |

| Búger | 8.29 | 950 | 1,014 | 1,089 | 1,152 |

| Bunyola | 84.7 | 5,029 | 6,270 | 7,115 | 7,343 |

| Calvià | 145.0 | 35,977 | 49,807 | 51,831 | 53,496 |

| Campanet | 34.6 | 2,309 | 2,536 | 2,654 | 2,785 |

| Campos | 149.7 | 6,360 | 9,712 | 11,471 | 11,817 |

| Capdepera | 54.9 | 8,239 | 11,281 | 12,212 | 12,585 |

| Consell | 13.7 | 2,407 | 3,778 | 4,240 | 4,291 |

| Costitx | 15.4 | 924 | 1,113 | 1,398 | 1,520 |

| Deià | 15.2 | 654 | 684 | 686 | 688 |

| Escorca | 139.4 | 257 | 258 | 183 | 195 |

| Esporles | 35.3 | 4,066 | 4,845 | 5,153 | 5,283 |

| Estellencs | 13.4 | 347 | 363 | 326 | 361 |

| Felanitx | 169.8 | 14,882 | 18,045 | 18,211 | 18,636 |

| Fornalutx | 19.5 | 618 | 695 | 681 | 715 |

| Inca | 58.3 | 23,029 | 30,359 | 33,719 | 34,459 |

| Lloret de Vistalegre | 17.4 | 981 | 1,308 | 1,469 | 1,591 |

| Lloseta | 12.1 | 4,760 | 5,690 | 6,318 | 6,453 |

| Llubí | 34.9 | 1,806 | 2,235 | 2,405 | 2,462 |

| Llucmajor | 327.3 | 24,277 | 35,995 | 38,475 | 39,156 |

| Manacor | 260.3 | 31,255 | 40,348 | 44,878 | 46,614 |

| Mancor de la Vall | 19.9 | 892 | 1,321 | 1,570 | 1,643 |

| Maria de la Salut | 30.5 | 1,972 | 2,122 | 2,235 | 2,333 |

| Marratxí | 54.2 | 23,410 | 34,538 | 38,351 | 39,455 |

| Montuïri | 41.1 | 2,344 | 2,856 | 3,061 | 3,142 |

| Muro | 58.6 | 6,107 | 7,010 | 7,547 | 7,842 |

| Palma | 208.7 | 333,801 | 402,044 | 424,837 | 430,640 |

| Petra | 70.0 | 1,911 | 2,876 | 3,051 | 3,151 |

| Pollença | 151.7 | 13,808 | 16,057 | 16,903 | 17,260 |

| Porreres | 86.9 | 4,069 | 5,459 | 5,630 | 5,749 |

| Puigpunyent | 42.3 | 1,250 | 1,878 | 2,073 | 2,090 |

| Santa Eugènia | 20.3 | 1,224 | 1,686 | 1,774 | 1,870 |

| Santa Margalida | 86.5 | 7,800 | 11,725 | 12,830 | 13,231 |

| Santa Maria del Camí | 37.6 | 4,959 | 6,443 | 7,526 | 7,579 |

| Santanyí | 124.9 | 8,875 | 12,427 | 12,364 | 12,561 |

| Sant Joan | 38.5 | 1,634 | 2,029 | 2,173 | 2,204 |

| Sant Llorenç des Cardassar | 82.1 | 6,503 | 8,490 | 9,058 | 9,378 |

| Sa Pobla | 48.6 | 10,388 | 12,999 | 14,064 | 14,296 |

| Selva | 48.8 | 2,927 | 3,699 | 4,113 | 4,289 |

| Sencelles | 52.9 | 2,146 | 3,113 | 3,616 | 3,876 |

| Ses Salines | 39.1 | 3,389 | 5,007 | 5,021 | 5,032 |

| Sineu | 47.7 | 2,736 | 3,696 | 4,156 | 4,387 |

| Sóller | 42.8 | 10,961 | 13,882 | 13,621 | 13,747 |

| Son Servera | 42.6 | 9,432 | 11,915 | 12,072 | 12,129 |

| Valldemossa | 42.9 | 1,708 | 1,990 | 2,047 | 2,053 |

| Vilafranca de Bonany | 24.0 | 2,466 | 2,984 | 3,553 | 3,691 |

Comarques

[edit]Population

[edit]Mallorca is the most populous island in the Balearic Islands and the second most populous island in Spain, after Tenerife,[40] in the Canary Islands, being also the fourth most populous island in the Mediterranean after Sicily, Sardinia and Cyprus.[41] It had a Census population of 920,605 inhabitants at the start of 2021,[42] and an official estimate of 940,332 at the start of 2023.[1]

Economy

[edit]

Since the 1950s, Mallorca has become a major tourist destination, and the tourism business has become the main source of revenue for the island.[43]

The island's popularity as a tourist destination has steadily grown since the 1950s, with many artists and academics choosing to visit and live on the island. The number of visitors to Mallorca continued to increase with holiday makers in the 1970s approaching 3 million a year. In 2010 over 6 million visitors came to Mallorca. In 2013, Mallorca was visited by nearly 9.5 million tourists, and the Balearic Islands as a whole reached 13 million tourists.[44] In 2017, ten million tourists visited the island.[45] The rapid growth of the tourism industry has led to some locals protesting the effects of mass tourism on the island.[46][47][48]

Mallorca has been jokingly referred to as the 17th Federal State of Germany, due to the high number of German tourists,[49][50] although people from the island reject this label and deem it "an insult".[51]

Due to a high number of expats choosing to settle down in the area, Mallorca has recently also become a business hub economy of its own, due to a high number of particularly foreign enterprises choosing to either relocate, or expand, to the island.

Attempts to build illegally caused a scandal in 2006 in Port Andratx that the newspaper El País named "caso Andratx".[52] A main reason for illegal building permits, corruption and black market construction is that communities have few ways to finance themselves other than through permits.[53] The former mayor was incarcerated in 2009 after being prosecuted for taking bribes to permit illegal house building.[54][55]

Top 10 arrivals by nationality

[edit]Data from Institute of Statistics of Balearic Islands[56]

| Rank | Country, region, or territory | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Germany | 3,237,745 | 3,731,458 | 3,710,313 | 3,450,687 | 3,308,604 | 2,224,709 |

| 2 | United Kingdom | 1,985,311 | 2,165,774 | 2,105,981 | 1,986,354 | 1,898,838 | 1,324,294 |

| 3 | Spain | 1,059,612 | 1,088,973 | 985,557 | 1,192,033 | 1,195,822 | 759,825 |

| 4 | Nordic countries | 641,920 | 758,940 | 758,637 | 668,328 | 572,041 | 387,875 |

| 5 | Benelux | 345,837 | 366,130 | 363,911 | 360,973 | 368,930 | 284,845 |

| 6 | Switzerland | 325,241 | 334,871 | 312,491 | 292,226 | 280,401 | 188,826 |

| 7 | France | 323,241 | 328,681 | 337,891 | 349,712 | 316,124 | 187,589 |

| 8 | Italy | 203,520 | 165,473 | 154,227 | 173,680 | 200,851 | 135,535 |

| 9 | Austria | 163,477 | 175,530 | 160,890 | 138,287 | 181,993 | 107,991 |

| 10 | Ireland | 104,556 | 100,059 | 104,827 | 115,164 | 158,646 | 68,456 |

Politics and government

[edit]

Regional government

[edit]The Balearic Islands, of which Mallorca forms part, are one of the autonomous communities of Spain. As a whole, they are currently governed by the People's Party of the Balearic Islands (PP), with Marga Prohens as their President.[57]

Insular government

[edit]The specific government institution for the island is the Insular Council of Mallorca commonly known as Council of Mallorca, created in 1978.[58]

It is responsible for culture, roads, railways (see Serveis Ferroviaris de Mallorca) and municipal administration. As of September 2023, Llorenç Galmés (PP) serves as president of the Insular Council.[59]

Results of the elections to the Council of Mallorca

[edit]Elections are held every four years concurrently with local elections. From 1983 to 2007, councilors were indirectly elected from the results of the election to Parliament of the Balearic Islands for the constituency of Mallorca. Since 2007, however, separate direct elections are held to elect the Council.

Island Councilors of the Council of Mallorca since 1978 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Election | Distribution | President | ||||||||

| 1979[60] |

|

Jeroni Albertí (UCD) (1979-1982) | ||||||||

| Maximilià Morales (UCD) (1982-1983) | ||||||||||

| 1983 |

|

Jeroni Albertí (UM) | ||||||||

| 1987 |

|

Joan Verger (PP) | ||||||||

| 1991 |

| |||||||||

| 1995 |

|

Maria Antònia Munar (UM) | ||||||||

| 1999 |

| |||||||||

| 2003 |

| |||||||||

| 2007 |

|

Francina Armengol (PSIB–PSOE) | ||||||||

| 2011 |

|

Maria Salom (PP) | ||||||||

| 2015 |

|

Miquel Ensenyat (MÉS) | ||||||||

| 2019 |

|

Catalina Cladera (PSIB–PSOE) | ||||||||

| 2023 |

|

Llorenç Galmés (PP) | ||||||||

Culture

[edit]Archduke Ludwig Salvator of Austria

[edit]

Archduke Ludwig Salvator of Austria (Catalan: Arxiduc Lluís Salvador) was a pioneer of tourism in the Balearic Islands. He first arrived on the island in 1867, travelling under his title "Count of Neuendorf". He later settled in Mallorca, buying up wild areas of land in order to preserve and enjoy them. Nowadays, a number of hiking routes are named after him.[61]

Ludwig Salvator loved the island of Mallorca. He became fluent in Catalan, carried out research into the island's flora and fauna, history, and culture to produce his main work, Die Balearen, a comprehensive collection of books about the Balearic Islands, consisting of 7 volumes. It took him 22 years to complete.[62]

Nowadays, several streets or buildings on the island are named after him (i.e., Arxiduc Lluís Salvador).

Chopin in Mallorca

[edit]

The Polish composer and pianist Frédéric Chopin, together with French writer Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin (pseudonym: George Sand), resided in Valldemossa in the winter of 1838–39. Apparently, Chopin's health had already deteriorated and his doctor recommended that he go to the Balearic Islands to recuperate, where he still spent a rather miserable winter.[63][64]

Nonetheless, his time in Mallorca was a productive period for Chopin. He managed to finish the Preludes, Op. 28, that he started writing in 1835. He was also able to undertake work on his Ballade No. 2, Op. 38; two Polonaises, Op. 40; and the Scherzo No. 3, Op. 39.[65]

Literature

[edit]French writer Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin (pseudonym: George Sand), at that time in a relationship with Chopin, described her stay in Mallorca in A Winter in Majorca, published in 1855. Other famous writers used Mallorca as the setting for their works. While on the island, the Nicaraguan poet Rubén Darío started writing the novel El oro de Mallorca, and wrote several poems, such as La isla de oro.[66]

The poet Miquel Costa i Llobera wrote in 1875 his famous ode, the Pine of Formentor, as well as other poems concerning old Mallorcan traditions and fantasies. Many of the works of Baltasar Porcel take place in Mallorca.

Agatha Christie visited the island in the early 20th century and stayed in Palma and Port de Pollença.[67] She would later write the book Problem at Pollensa Bay and Other Stories, a collection of short stories, of which the first one takes place in Port de Pollença, starring Parker Pyne.

Jorge Luis Borges visited Mallorca twice, accompanied by his family.[68] He published his poems La estrella (1920) and Catedral (1921) in the regional magazine Baleares.[69] The latter poem shows his admiration for the monumental Cathedral of Palma.[70]

Nobel Prize winner Camilo José Cela came to Mallorca in 1954, visiting Pollença, and then moving to Palma, where he settled permanently.[71] In 1956, Cela founded the magazine Papeles de Son Armadans.[72] He is also credited as founder of Alfaguara.

The English writer and poet Robert Graves moved to Mallorca with his family in 1946. The house is now a museum. He died in 1985 and was buried in the small churchyard on a hill at Deià.[73] Ira Levin set part of his dystopian novel This Perfect Day in Mallorca, making the island a centre of resistance in a world otherwise dominated by a computer.

Music and dance

[edit]The Ball dels Cossiers is the island's traditional dance. It is believed to have been imported from Catalonia in the 13th or 14th century, after the Aragonese conquest of the island under King Jaime I.[74] In the dance, three pairs of dancers, who are typically male, defend a "Lady," who is played by a man or a woman, from a demon or devil. Another Mallorcan dance is Correfoc, an elaborate festival of dance and pyrotechnics that is also of Catalan origin. The island's folk music strongly resembles that of Catalonia, and is centered around traditional instruments like the xeremies (bagpipe) and guitarra de canya (a reed or bone xylophone-like instrument suspended from the neck).[75] While folk music is still played and enjoyed by many on the island, a number of other musical traditions have become popular in Mallorca in the 21st century, including electronic dance music, classical music, and jazz, all of which have annual festivals on the island.[76]

Art

[edit]Joan Miró, a Spanish painter, sculptor, and ceramicist, had close ties to the island throughout his life. He married Pilar Juncosa in Palma in 1929 and settled permanently in Mallorca in 1954.[77] The Fundació Pilar i Joan Miró in Mallorca has a collection of his works. Es Baluard in Palma is a museum of modern and contemporary art which exhibits the work of Balearic artists and artists related to the Balearic Islands.

Film

[edit]The Evolution Mallorca International Film Festival is the fastest growing Mediterranean film festival and has taken place annually every November since 2011, attracting filmmakers, producers, and directors globally. It is hosted at the Teatro Principal in Palma de Mallorca.[78][better source needed]

Mallorcan cartographic school

[edit]

Mallorca has a long history of seafaring. The Majorcan cartographic school or the "Catalan school" refers to a collection of cartographers, cosmographers, and navigational instrument makers who flourished in Mallorca and partly in mainland Catalonia in the 13th, 14th, and 15th centuries. Mallorcan cosmographers and cartographers developed breakthroughs in cartographic techniques, namely the "normal portolan chart", which was fine-tuned for navigational use and the plotting by compass of navigational routes, prerequisites for the discovery of the New World.

Cuisine

[edit]

In 2005, there were over 2,400 restaurants on the island of Mallorca according to the Mallorcan Tourist Board, ranging from small bars to full restaurants.[citation needed] Olives and almonds are typical of the Mallorcan diet. Among the foods that are typical from Mallorca are sobrassada, arròs brut (saffron rice cooked with chicken, pork and vegetables), and the sweet pastry ensaïmada. Also Pa amb oli is a popular dish.[79]

Herbs de Majorca is a herbal liqueur.

Language

[edit]The two official languages of Mallorca are Catalan and Spanish,[80] a dialect of the former being the indigenous language of Mallorca.[81] The local dialect of Catalan spoken in the island is Mallorquí, with slightly different variants in most villages. Education is bilingual in Catalan and Spanish, with some teaching of English.[82]

In 2012, the then-governing People's Party announced its intention to end preferential treatment for Catalan in the island's schools to bring parity to the two languages of the island. It was said that this could lead Mallorcan Catalan to become extinct in the fairly near future, as it was being used in a situation of diglossia in favour of the Spanish language.[83] However, following a May 2015 election that swept a pro-Catalan party into power, this policy was dropped.[84]

Transportation

[edit]

A trackless train is in operation in several tourist areas.[85]

Water transport

[edit]There are approximately 79 ferries between Mallorca and other destinations every week, most of them to mainland Spain.

- Baleària

- to the Balearic Islands from Dénia, Valencia and Barcelona

- Trasmediterránea

Cycling

[edit]One of Europe's most popular cycling destinations, Mallorca cycling routes such as the popular 24 km cycle track (segregated cycle lane) which runs between Porto Cristo and Cala Bona via Sa Coma and Cala Millor are must rides.

Renowned Mallorcans

[edit]

Some of the earliest famous Mallorcans lived on the island before its reconquest from the Moors. Famous Mallorcans include:

- Ramon Llull, a medieval friar, writer and philosopher, who wrote the first major work of Catalan Literature;

- Al-Humaydī, Moorish historian, born on the island in 1029.

- Abraham Cresques, a 14th-century Jewish cartographer of the Majorcan cartographic school from Palma, believed to be the author of the Catalan Atlas;

- Catalina Tomas, 16th-century canoness and mystic, one of the patron saints of the island

- Junípero Serra, the Franciscan friar who founded the mission chain in Alta California in 1769.

- Miquel Costa i Llobera, a famous Mallorcan poet, who wrote The Pine of Formentor.

- Joaquín Jovellar y Soler, 19th century military commander.

- Antonio Maura, two-time Spanish Prime Minister during the reign of King Alfonso XIII.

- Robert Graves, English writer and poet who lived for many years in Mallorca, buried in a small churchyard on a hill at Deià

- Joan Daurer, painter active between 1358-1374.

Notable residents, alive in modern times

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2015) |

- Eaktay Ahn (1906–1965), founder of the Balearic Symphony Orchestra and composer of the Korean national anthem, lived in Mallorca from 1946 until his death in 1965.[86]

- Jeffrey Archer, English novelist, owns a villa in Mallorca[87]

- Marco Asensio, Spanish footballer, former Real Madrid player and currently at Paris Saint-Germain, was born in Palma, Mallorca.

- Miquel Barceló, contemporary painter, created sculptures in Palma Cathedral.

- Concha Buika, contemporary flamenco singer. Concha Buika was born on 11 May 1972, in Palma de Mallorca.

- Jean Batten, the New Zealand aviator, died in Mallorca in 1982.

- Conor Benn, British professional boxer, spent twelve years of his childhood living in Mallorca.[88]

- Nigel Benn, former British professional boxer who moved with his family to Mallorca following the conclusion of his boxing career.[89]

- Maria del Mar Bonet, musician, member of the Catalan language group Els Setze Jutges in the 1960s with brother Joan Ramon Bonet.

- Samuel Bouriah, better known as DJ Sammy, dance artist and producer.

- Faye Emerson and Anne Lindsay Clark, divorcees of Elliott Roosevelt and John Aspinwall Roosevelt (US Officials and sons of Franklin Delano Roosevelt) respectively, retired to Mallorca in 1965. Emerson died in Deià in 1983.

- Sheila Ferguson, resident, a former member of the Three Degrees.

- Rudy Fernández basketball player.

- Curt Flood, baseball player, purchased a bar in Palma, Majorca after leaving the Washington Senators in 1971.

- Antònia Font, contemporary pop band in the Mallorcan dialect of Catalan.

- Toni Kroos, footballer for Real Madrid and Germany national football team.

- Cynthia Lennon (1939–2015), former wife of John Lennon, lived and died in Mallorca.

- Jorge Lorenzo professional motorcycle road racer, won the world 250cc Grand Prix motorcycle title in 2006 and 2007, and the 2010, 2012 & 2015 MotoGP World Championships.

- Colm Meaney, Irish actor, resides in the town of Sóller.

- Mads Mikkelsen, Danish actor, purchased a vacation home in Mallorca, where he spends most of his time.[90]

- Joan Mir, professional motorcycle road racer and 2020 MotoGP World Champion.

- Carlos Moyá, former world No.1 tennis player and coach of Rafael Nadal.

- Xisco Muñoz, former footballer and coach (FC Dinamo Tbilisi, Watford F.C), was born in Manacor.

- Rafael Nadal, 22-time major champion and former world No. 1 tennis player, lives in Manacor.

- Toni Nadal, Rafael Nadal's uncle and his former coach.

- Miguel Ángel Nadal, Rafael Nadal's uncle, former FC Barcelona and Spanish international footballer.

- John Noakes, former British TV presenter, lived in Andratx.

- Jean Emile Oosterlynck, the Flemish painter, lived in Mallorca from 1979 until his death in 1996.

- Hana Soukupova, supermodel, owns a villa in Mallorca.

- José María Sicilia, painter, resides in the town of Sóller.

- Jørn Utzon, an architect best known for designing the Sydney Opera House, designed and built two houses in Mallorca, Can Lis and Can Feliz.

- Agustí Villaronga (born 1953), filmmaker, born in Palma.

Gallery

[edit]-

La Seu, Palma Cathedral

-

Lakes Cúber and Gorg Blau, Serra de Tramuntana

-

Puig Major, highest peak in Mallorca

-

Sunrise across Pollensa Bay, Port de Pollença

-

Cap de Ses Salines

-

Cala Agulla, Capdepera

-

Aerial of Cala Amarador beach

-

Aerial of Cala Llombards beach

-

Platja de Palma beach

-

Aerial of Platja de Palma beach

-

Sa Foradada

-

Port de Sóller

-

Platja de Muro

-

Port Adriano

See also

[edit]- Gymnesian Islands

- Observatorio Astronómico de Mallorca

- RCD Mallorca – local association football club

Notes

[edit]- ^ Balearic Catalan: [məˈʎɔɾkə, -cə]; Spanish: [maˈʎoɾka]

- ^ English: /məˈjɔːrkə, maɪ-, -ˈdʒɔːr-/, mə-YOR-kə, my-, -JOR-

References

[edit]- ^ a b Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Madrid, 2023.

- ^ "Mallorca: definition". Collins Dictionary. n.d. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ^ Keenan, Steve (6 July 2009). "Mallorca v Majorca: which is correct?". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 6 June 2010. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

- ^ Tisdall, Nigel (2003). Mallorca. Thomas Cook Publishing. p. 15. ISBN 9781841573274.

- ^ "Presentación". AENA Aeropuerto de Palma de Mallorca (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 11 November 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ^ "Diccionari català-valencià-balear". dcvb.iec.cat. Archived from the original on 20 September 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "The Mallorca Black pig: Production system, conservation and breeding strategies" Archived 24 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, J. Jaume, M. Gispert, M.A. Oliver, E. Fàbrega, N. Trilla, and J. Tibau. Institut Balear de Biologia Animal. 2008. Retrieved 24 February 2017

- ^ Fernandes, Daniel M.; Mittnik, Alissa; Olalde, Iñigo; Lazaridis, Iosif; Cheronet, Olivia; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Bernardos, Rebecca; Broomandkhoshbacht, Nasreen; Carlsson, Jens; Culleton, Brendan J. (1 March 2020). "The spread of steppe and Iranian-related ancestry in the islands of the western Mediterranean". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 4 (3): 334–345. Bibcode:2020NatEE...4..334F. doi:10.1038/s41559-020-1102-0. ISSN 2397-334X. PMC 7080320. PMID 32094539.

- ^ Alcover, Josep Antoni (1 March 2008). "The First Mallorcans: Prehistoric Colonization in the Western Mediterranean". Journal of World Prehistory. 21 (1): 19–84. doi:10.1007/s10963-008-9010-2. ISSN 1573-7802. S2CID 161324792. Archived from the original on 25 October 2023. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ Valenzuela, Alejandro; Torres-Roig, Enric; Zoboli, Daniel; Pillola, Gian Luigi; Alcover, Josep Antoni (29 November 2021). "Asynchronous ecological upheavals on the Western Mediterranean islands: New insights on the extinction of their autochthonous small mammals". The Holocene. 32 (3): 137–146. doi:10.1177/09596836211060491. hdl:11584/322952. ISSN 0959-6836. S2CID 244763779. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ^ Tisdall, Nigel (2003). Mallorca. Thomas Cook Publishing. p. 11. ISBN 9781841573274.

- ^ López Castro, José Luis (31 October 2019), Doak, Brian R.; López-Ruiz, Carolina (eds.), "The Iberian Peninsula", The Oxford Handbook of the Phoenician and Punic Mediterranean, Oxford University Press, pp. 583–602, doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190499341.013.38, ISBN 978-0-19-049934-1, retrieved 17 September 2025

- ^ Lazenby, John Francis (1996). The First Punic War: A Military History. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2673-3.

- ^ Oppidum Bocchoritanum Archived 16 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine. The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites .

- ^ History of Mallorca. North South Guides.

- ^ a b The Dark Ages in Mallorca Archived 7 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine mallorcaincognita.com, not dated

- ^ Moorish Mallorca Archived 7 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine mallorcaincognita.com, not dated.

- ^ The Pillage People, Contemporary Balears.

- ^ The Spanish Civil War, Hugh Thomas (2001)

- ^ "Large rise in number of foreign nationals" Archived 26 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine. The Mallorca. 15 January 2009.

- ^ Emblematic objects for societies in transition. An archaeological and archaeometric study of the sword of Serral de ses Abelles (Puigpunyent, Mallorca). Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports Volume 40, Part A, December 2021, 103201

- ^ Margaritoff, Marco (20 September 2019). "3,200-Year-Old Bronze Age Sword Unearthed On Spanish Island Of Mallorca". All That's Interesting. Archived from the original on 30 October 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ "Fantastic views from the top of Palma Cathedral". Majorca Daily Bulletin. 3 May 2019. Archived from the original on 29 January 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ "Weather Mallorca - All about Mallorca". abcMallorca. Archived from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- ^ "WMO Normals Spain 1991–2020, Palma Puerto (Excel)". NOAA. Archived from the original on 16 October 2023. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- ^ "Extreme values: Palma, Puerto - Absolute extreme values - Selector - State Meteorological Agency - AEMET - Spanish Government". Archived from the original on 16 October 2023. |title=Extreme values: Palma, Puerto |publisher=AEMET |accessdate=7 October 2023

- ^ "WMO Normals Spain 1991–2020, Palma Aeropuerto (Excel)". NOAA. Archived from the original on 16 October 2023. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- ^ "Extreme values: Palma de Mallorca, Aeropuerto". AEMET. Archived from the original on 16 October 2023. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- ^ "Palma de Mallorca Sea Temperature". seatemperature.org. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- ^ "Palma, Spain - Climate data". Weather Atlas. Archived from the original on 16 March 2017. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- ^ "Entstehung Mallorcas [German]". Archived from the original on 28 May 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ^ "Ein Felsen, der aus dem Meer gewachsen ist" [German], interview with geologist Rosa Mateos in Mallorca Magazin 13/2009, pp. 62-63.

- ^ "Puig de Massanella : Climbing, Hiking & Mountaineering : SummitPost". www.summitpost.org. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

- ^ "Climb to the highest mountains of Mallorca (Mallorca)". illesbalears.travel. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

- ^ Cifra de población referida al 1 January 2009 según el Instituto Nacional de Estadística

- ^ "The Largest Islands Of Spain By Size". worldatlas.com. Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ Tisdall, Nigel (2003). Mallorca. Thomas Cook Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 9781841573274.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Las playas menos famosas de la isla de Mallorca". Vipealo. 3 December 2020. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- ^ "Cultural Landscape of the Serra de Tramuntana – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Unesco. 27 June 2011. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ "Real Decreto 1458/2018, de 14 de diciembre, por el que se declaran oficiales las cifras de población resultantes de la revisión del Padrón municipal referidas al 1 de enero de 2018" [Royal Decree 1458/2018, of 14 December, by which the population numbers resulting from the review of the municipal register as of 01 January 2018 are declared official] (PDF) (in Spanish). Ministerio de Economía y Empresa. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 December 2018. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- ^ Mallorca, cuarta isla más poblada del Mediterráneo Archived 1 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine, ver 1 January 2016

- ^ Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Madrid, 2021.

- ^ Margottini, Claudio; Canuti, Paolo; Sassa, Kyoji (2013). Landslide Science and Practice. Vol. 7: Social and Economic Impact and Policies. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 105. ISBN 9783642313134. Archived from the original on 25 October 2023. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ^ "Flujo de turistas (FRONTUR)". ibestat.cat. 2014. Archived from the original on 30 December 2014.

- ^ Balearic Islands Tourism Board (24 July 2017). "BALEARIC ISLANDS REGIONAL CONTEXT SURVEY" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 July 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ^ Florio, Erin (19 July 2018). "Spanish Island Tells Tourists to Stay Home". Condé Nast Traveler. Archived from the original on 15 December 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ^ Yoeli-Rimmer, Orr (31 October 2017). "Mass tourism in Mallorca: Trouble in paradise". Cafébabel. Archived from the original on 21 April 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ^ "Mallorca aims for refined cocktails, not party tourism | DW | 18 April 2019". DW.COM. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ^ "100 Jahre Mallorca-Tourismus: Das 17. deutsche Bundesland" [100 Years Majorca Tourism: The 17th German Federal State]. Spiegel Online (in German). 29 June 2005. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ^ Emilio Rappold (29 July 2014). "Mallorca ist das 17. Bundesland" [Mallorca is the 17th federal state]. HuffingtonPost.de (in German). Archived from the original on 6 December 2015. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ^ Martín, Mercedes Rodríguez (26 July 2024). "Los lemas antituristas en el "paraíso" de Mallorca resuenan en Alemania: "Vuelos asesinos"". Libre Mercado (in European Spanish). Retrieved 17 December 2024.

- ^ "La investigación del 'caso Andratx' descubre un 'pelotazo' de 10 millones en suelo rústico" [The investigation of the 'Andratx case' discovers a 'pelotazo' of 10 million on the ground]. El País (in Spanish). 30 November 2006. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Johannes Höflich, Jo Angerer (2010). "Bedrohte Paradiese (2/3): Mallorca und die Balearen – Ferienparadies am Abgrund" [Threatened Paradises (2/3): Majorca and the Balearic Islands – holiday paradise on the brink] (documentary). phoenix (in German). WDR. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Andreu Manresa (29 December 2009). "El ex alcalde de Andratx y un ex director general entran en prisión" [The former mayor of Andratx and a former director general enter a rustic prison]. El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 28 October 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Patrick Sawer (21 February 2009). "Scott gives evidence in holiday homes affair". Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ "Turistas con destino principal las Illes Balears por periodo, isla y país de residencia" [Tourists with the Balearic Islands as their main destination by period, island and country of residence] (in Spanish). Institut d'Estadistica de les Illes Balears. Archived from the original on 30 December 2014. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- ^ "Real Decreto 603/2023, de 6 de julio, por el que se nombra Presidenta de las Illes Balears a doña Margarita Prohens Rigo" (PDF). Boletín Oficial del Estado (in Spanish) (161). Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado: 96063. 7 July 2023. ISSN 0212-033X. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 July 2023. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ^ Blasco Esteve, Avelino (2016). "Consejos insulares y diputaciones provinciales". Documentación Administrativa (3). Madrid: Instituto Nacional de Administración Pública. doi:10.24965/da.v0i3.10371. ISSN 1989-8983. Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ "Llorenç Galmés (PP), nuevo presidente del Consell de Mallorca en coalición con Vox". 8 July 2023. Archived from the original on 15 July 2023. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ^ "1979 Preautonomous elections in the Balearic Islands" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2024.

- ^ "Camí de l'Arxiduc" [Path of the Archduke]. Mallorca Aventura (in Catalan). Archived from the original on 28 January 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^ "Die Balearen in Wort und Bild" [The Balearic Islands in words and pictures] (in German). Archived from the original on 29 December 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ^ Nigel Tisdall (29 December 2009). "Majorca: sun, sand and Chopin". Travel. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ^ Mary Ann Sieghart (5 February 2011). "George Sand's Mallorca". Independent. Archived from the original on 17 April 2015. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ^ Zamoyski (2010), p. 168 (loc. 2646).

- ^ "Rubén Darío en Mallorca" (PDF). Centro Virtual Cervantes (in Spanish). Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 December 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ "Agatha Christie: inspired by Mallorca – Illes Balears". Govern de les Illes Balears. Archived from the original on 30 December 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ "Jorge Luis Borges and Mallorca". Balearsculturaltour. Archived from the original on 28 September 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^ "Jorge Luis Borges — Revistas y Diarios" [Jorge Luis Borges — Journals and Diaries] (in Spanish). Argentine Cultural Ephemerides. Archived from the original on 30 December 2014.

- ^ Carlos Meneses. "Borges y España — Mallorca en Borges" [Borges and Spain — Mallorca in Borges]. Centro Virtual Cervantes (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2 May 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^ José Carlos Llop (17 January 2002). "Cautivos en la isla: En la muerte de Camilo José Cela" [Captives on the island: In the death of Camilo José Cela]. EL Cultural (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 4 January 2017. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ^ "El nacimiento de Papeles de Son Armadans" [The birth of Papeles de Son Armadans]. Papeles de Son Armadans (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 18 May 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^ Barkham, Patrick (27 October 2012). "'I didn't just bury the past, I buried it alive'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ "Ritual made dance: the Ball dels Cossiers". Illes Balears. Archived from the original on 6 April 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ^ "Traditional music and dance in Mallorca". My Guide Mallorca. 9 September 2016. Archived from the original on 1 October 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ^ "Music Scene in Mallorca". See Majorca. Archived from the original on 26 June 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- ^ "Joan Miró en Mallorca". Fundació Pilar i Joan Miró a Mallorca (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 1 November 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ^ "Evolution Mallorca International Film Festival". abcMallorca. Archived from the original on 7 November 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ "Restaurants". Infomallorca. Consell de Mallorca. Archived from the original on 25 October 2023. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- ^ Article 4 of the "Estatut d'autonomia de les Illes Balears" [Statute of Autonomy of the Balearic Islands] (PDF) (in Catalan). 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 May 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

Catalan language, Balearic Islands' own language, will have, together with the Spanish language, the character of official language.

- ^ Bruyèl-Olmedo, Antonio; Juan-Garau, Maria (19 September 2015). "Minority languages in the linguistic landscape of tourism: the case of Catalan in Mallorca". Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 36 (6): 598–619. doi:10.1080/01434632.2014.979832. ISSN 0143-4632. S2CID 145220830. Archived from the original on 2 August 2022. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ "History of Majorca". Majorcan Villas. Archived from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- ^ Andreu Manresa (17 July 2012). "El PP recorta el peso oficial del catalán en Baleares" [The PP reduces the official standing of Catalan in the Balearic Islands]. El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 26 May 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- ^ Andreu Manresa (3 July 2015). "La izquierda de Baleares "entierra" el trilingüismo y potencia el catalán" [The left of the Balearic Islands "buries" trilingualism and promotes Catalan]. El País (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 22 September 2017. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ^ "Rent a boat mallorca guide". Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 20 September 2020. Thursday, 10 September 2020

- ^ "Mallorca". www.illesbalears.es. Archived from the original on 8 October 2016. Retrieved 15 May 2016.

- ^ Emma Wells (31 October 2010). "It's Archer's best plot yet". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ "Watch as Conor Benn speaks fluent Spanish to trash talk opponent in face-off". talkSPORT. 9 April 2021. Archived from the original on 12 June 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ Machell, Ben. "Boxer Conor Benn: why I've followed my father, Nigel, into the ring". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Archived from the original on 12 June 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ "Mads Mikkelsen: A Great Dane". Living in Mallorca. 12 December 2018. Archived from the original on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

External links

[edit]Mallorca

View on GrokipediaMallorca, the largest island in Spain's Balearic Islands archipelago in the western Mediterranean Sea, spans 3,640 square kilometers and supports a population of approximately 949,000 residents as of 2024.[1][2] The island's terrain varies from the rugged Serra de Tramuntana mountain range in the northwest, a UNESCO World Heritage site recognized for its cultural landscape of terraces and historic settlements, to extensive sandy beaches and fertile plains in the east and south.[3] Its Mediterranean climate, characterized by mild winters and hot summers, underpins a landscape shaped by prehistoric Talaiotic settlements dating back to around 1300 BC, followed by successive occupations including Roman conquest in 123 BC, Arab rule from the 8th century, and Christian reconquest by Aragonese forces in 1229.[4] Economically, tourism dominates, accounting for about 75% of output and attracting over 14 million visitors annually by recent peaks, though this reliance has fueled debates over resource strain and local displacement amid record visitor numbers despite protests.[5][6] Palma de Mallorca, the island's capital and primary port, serves as an administrative and cultural hub with a history tracing to Roman origins.[4]

Etymology

Name origins and historical usage

The name Mallorca originates from the Classical Latin phrase insula maior, translating to "larger island," a designation highlighting its comparative size to the smaller insula minor (Menorca) within the Balearic archipelago.[7][8] This Latin form, Maiorica, reflected Roman administrative usage following their conquest around 123 BCE, distinguishing the island from its neighbors in Mediterranean cartography and records.[8] Under Islamic rule from 902 to 1229 CE, the island adopted the Arabic name Mayūrqa or Mayorqa, as documented in medieval Arabic sources, which adapted the Latin root while incorporating Semitic linguistic influences from prior Phoenician-Punic settlements in the region.[9] Following the Christian reconquest led by James I of Aragon in 1229, the name shifted to the Catalan Mallorca, solidifying in post-medieval Iberian documentation and legal texts.[8] The anglicized spelling Majorca emerged in English-language contexts during the early modern period, likely through phonetic transcription of the Latin or Catalan forms in nautical charts and travelogues, and endured in British tourism branding into the 20th century despite the official Spanish and Catalan preference for Mallorca.[10][8] This variant persists in some non-Spanish references but has largely yielded to Mallorca in contemporary international usage.[10]History

Prehistoric settlements and early inhabitants

Human settlement in Mallorca began during the late Neolithic to early Bronze Age, with the earliest evidence of human presence dated to around the 3rd millennium BCE, later than in other Mediterranean islands.[11] Archaeological findings indicate initial colonization involved small groups introducing agriculture, including cereals, and domesticated animals such as sheep and goats, marking a shift from hunter-gatherer economies.[12] Rapid population growth followed, supported by environmental adaptation and resource exploitation.[12] The dominant prehistoric culture on Mallorca was the Talayotic culture, spanning the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age from approximately 1300 BCE to the Roman conquest in 123 BCE.[13] This society constructed monumental talayots—large, dry-stone towers up to 10 meters high, either circular or square-based—likely serving defensive, communal, or ceremonial functions, built without mortar using local limestone.[14] Associated settlements featured circular houses, defensive walls, and evidence of bronze metallurgy, with tools and weapons indicating technological advancement and possible trade networks for metals and obsidian.[13] Agriculture intensified, with terracing and irrigation precursors evident, sustaining a dispersed settlement pattern across the island.[15] Key archaeological sites include the Son Real necropolis near Can Picafort, comprising over 100 tombs in circular, square, and irregular forms from the Talayotic period, yielding pottery, weapons, bones, and signs of varied burial practices such as cremation and inhumation.[16] Approximately 300 Talayotic settlements have been identified island-wide, reflecting a substantial and organized prehistoric population estimated in the thousands, with continuity in subsistence patterns into later eras.[15] These findings, derived from excavations emphasizing empirical stratigraphy and artifact analysis, underscore a self-sufficient insular society prior to external contacts.[17]Ancient civilizations: Phoenicians, Romans, and Byzantines

The Phoenicians, originating from the Levant, initiated maritime trade networks across the western Mediterranean around the 8th century BC, establishing contacts with the Balearic Islands, including Mallorca, where local Talaiotic culture prevailed.[18] Archaeological evidence from sites in Mallorca reveals imported Phoenician goods such as ceramics and metals, indicating trading posts rather than large-scale colonization, with Ibiza serving as the primary Phoenician settlement in the archipelago. Under Carthaginian expansion from the 6th century BC, Punic influence intensified, marked by the adoption of burial practices and pottery styles at proto-urban sites, potentially including precursors to later settlements like Alcúdia, though permanent Punic towns remained sparse on Mallorca compared to other islands. Roman conquest of Mallorca occurred in 123 BC under praetor Quintus Caecilius Metellus Balearicus, who subdued the indigenous Balearic slingers and incorporated the island into Roman Hispania.[19] Metellus founded Pollentia adjacent to modern Alcúdia as the provincial capital, featuring a forum, amphitheater accommodating up to 8,000 spectators, and an early Christian basilica by the 5th century AD.[20] Roman engineering introduced paved roads spanning approximately 100 kilometers, aqueducts, and rural villas, fostering economic specialization in olive cultivation and viticulture; excavations at villas like Sa Mesquida yield amphorae fragments evidencing export-oriented production of olive oil and wine to mainland markets.[19] This infrastructure supported a population estimated at 20,000–30,000 by the 1st century AD, shifting from subsistence to integrated Mediterranean trade.[21] After Vandal raids devastated Roman settlements around 425–455 AD, Byzantine general Belisarius reconquered the Balearics in 534 AD as part of Emperor Justinian I's Mediterranean campaigns, restoring imperial administration until the Umayyad Muslim invasion in 902–903 AD.[22] Byzantine governance emphasized defense, with fortifications reusing Roman materials and sparse ecclesiastical structures like modified basilicas, but material culture shows continuity in pottery and coinage rather than innovation.[23] Artifacts remain limited, including African Red Slip ware and Byzantine coins, suggesting a period of relative isolation and decline in urban centers like Pollentia, which saw reduced occupation by the 7th century.[24]Islamic conquest and rule (902–1229)

The Muslim conquest of Mallorca occurred in 902, when forces under the Emirate of Córdoba annexed the island to their territories, ending Byzantine influence and integrating it into the Islamic world.[25] This expedition, likely dispatched from North African bases aligned with Córdoba, established control over the Balearic archipelago, with Mallorca as the primary center. The capital was founded as Madînat Mayûrqa (City of Mallorca) at the site of present-day Palma, featuring a planned urban layout including fortifications, mosques, and administrative structures that facilitated governance and trade.[26][27] Following incorporation into the Umayyad Emirate, Mallorca's political status evolved with the collapse of the Córdoba caliphate in 1031, leading to the emergence of taifa kingdoms. Initially under the Taifa of Dénia, the island gained independence as the Taifa of Mallorca around 1015–1031, ruled by the Arab Banu Sanad dynasty until 1116.[26][28] Subsequent control shifted to the Almoravid Banu Ghaniya family, Berber rulers from North Africa, who maintained authority amid intermittent Christian incursions, such as the failed Pisan-Catalan siege of Palma in 1114–1115.[4] Internal divisions persisted between Arab elites, who held higher social status, and Berber military settlers, often leading to tensions over resources and power.[29][30] Society under Muslim rule comprised a stratified mix of Arab administrators, Berber warriors, converted locals (muladis), and non-Muslim dhimmis including Mozarabic Christians and Jews, who retained communities and places of worship but paid the jizya tax.[31][32] While policies allowed religious practice, conversion to Islam was incentivized for social mobility, and the ruling class remained predominantly Arab-Berber, with indigenous elements gradually assimilating. The taifa period saw economic orientation toward maritime activities, including raids on Christian Mediterranean coasts for slaves and goods, which supplemented local production but invited retaliatory expeditions.[33] Agricultural productivity surged due to introduced irrigation systems, such as qanats and watermills, enabling cultivation of arid lands and boosting output of crops like almonds, oranges, figs, and olives—many newly widespread from North African and Eastern origins.[34] These innovations, including terracing and pest control methods, transformed Mallorca into a key exporter of foodstuffs, supporting urban growth in Madînat Mayûrqa and rural rahals (hamlets).[35] Infrastructure developments, like the preserved Arab baths in Palma, underscored hydraulic expertise applied to public hygiene and industry.[36] However, reliance on Berber tribal loyalties and vulnerability to North African dynastic shifts contributed to instability, as seen in Almoravid and later Almohad interventions.Reconquest and medieval Christian era (1229–1715)

In September 1229, James I of Aragon launched a military expedition against the Almohad-controlled island of Mallorca, deploying approximately 15,000 troops via a fleet that landed near Santa Ponsa before advancing to besiege the capital, Medina Mayurqa (present-day Palma).[28] The city surrendered on 31 December 1229, marking the effective end of Muslim rule on the main island, though mopping-up operations continued into 1231 against pockets of resistance.[37] Following the victory, James I oversaw the repopulation of depopulated areas with Christian settlers primarily from Catalonia, Aragon, and southern France, while dividing conquered lands into feudal estates granted to participating nobles such as Nuño Sánchez and the Templars, alongside crown-retained domains around Palma and key ports.[28] The surviving Muslim population, known as Mudéjars, was initially permitted to remain as tributaries under Christian overlordship, preserving some Islamic legal customs and contributing labor to agriculture and crafts, though their numbers dwindled over time due to emigration, conversion pressures, and later expulsions.[38] A vibrant Jewish community, augmented by migrants from Catalan territories, established an aljama in Palma's Call Major quarter, playing key roles in trade, medicine, and cartography—exemplified by figures like Abraham Cresques—until pogroms in 1391 and forced conversions by 1435 decimated their presence.[39] Construction of the Gothic-style Palma Cathedral (La Seu) commenced in 1229 on the ruins of the main mosque, symbolizing Christian dominance, with its foundational phases reflecting early Catalan architectural influences amid ongoing feudal consolidation.[40] In 1276, James I detached Mallorca from direct Aragonese rule by granting it as a separate kingdom to his son James II, encompassing the Balearic Islands alongside Roussillon, Cerdagne, and Montpellier, which fostered a brief era of autonomy focused on maritime commerce until Peter IV of Aragon invaded and reannexed it in 1343–1344, citing vassalage breaches.[28] The subsequent decades ushered in a decadencia marked by demographic collapse from the 1348 Black Death, which halved the island's population to around 20,000–30,000, compounded by feudal exactions, pirate raids, and agricultural stagnation that ignited peasant revolts against noble privileges in the 1330s–1450s, including uprisings demanding tax relief and land reforms.[41] Economic revival gained traction by the late 14th century through expanded Mediterranean trade networks linking Palma to Italian city-states and North Africa, spurring artisan guilds for silk, leather, and shipbuilding that bolstered urban prosperity despite intermittent crises like the 1391 anti-Jewish violence.[39] This medieval framework persisted under the Crown of Aragon until the War of the Spanish Succession, during which Mallorcan allegiance to Habsburg claimant Archduke Charles prompted Bourbon forces loyal to Philip V to besiege and occupy the island on 2 July 1715, effectively dismantling its autonomous institutions via impending Nueva Planta decrees.[42]Bourbon reforms and 19th-century developments

The Nueva Planta decrees of 1715, promulgated by Philip V following the War of the Spanish Succession, abolished the independent Kingdom of Mallorca's institutions and privileges, fully incorporating the island into the centralized Bourbon monarchy of Spain and subjecting it to Castilian legal and administrative frameworks.[43] This integration eliminated local fueros, replacing them with royal intendants and uniform governance to enhance fiscal extraction and military recruitment, aligning Mallorca with Bourbon efforts to consolidate absolutist control across former Aragonese territories.[44] Throughout the 18th century, Bourbon administrative reforms extended to Mallorca via intensified tax collection and infrastructure projects, such as road improvements and port enhancements in Palma, aimed at boosting trade and agricultural output under mercantilist policies. These measures prioritized royal revenue over local autonomy, though implementation faced resistance from entrenched landowners. By the early 19th century, agricultural modernization gained momentum, with initiatives to expand olive, almond, and vineyard cultivation using improved irrigation and crop rotation techniques, positioning wine exports—particularly malvasía—as a economic mainstay, accounting for significant portions of island revenue by mid-century. The phylloxera vastatrix epidemic, introduced from American vines and reaching Mallorca in 1891, ravaged over 90% of the island's vineyards by the early 1900s, causing widespread economic distress and forcing farmers to abandon en masse or experiment with resistant rootstocks through grafting.[45] In response, producers diversified into frost-resistant crops like figs and carob, alongside limited replanting, which gradually stabilized rural economies but marked a shift from monoculture dependence.[46] Politically, 19th-century Mallorca witnessed the emergence of liberal factions in Palma, advocating constitutionalism and free trade amid Spain's turbulent shifts from absolutism to successive pronunciamientos, contrasting with rural traditionalism. The Carlist Wars (1833–1840, 1846–1849, and 1872–1876), pitting dynastic liberals against absolutist claimants, imposed indirect burdens through conscription, disrupted commerce, and fiscal strains, though major combat bypassed the island, fostering local instability via polarized militias and economic blockades that hampered exports.[47] These conflicts ultimately reinforced liberal dominance in urban centers by 1876, paving for modest administrative reforms under the Restoration.20th century: Civil War, Franco era, and tourism boom

The Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) saw Mallorca rapidly fall under Nationalist control following the July 1936 uprising, with the island serving as a base for Nationalist operations in the western Mediterranean. Republican forces attempted an amphibious landing between August 16 and September 4, 1936, targeting Palma and other key sites, but the operation failed amid fierce resistance and Italian naval and air support for the Nationalists.[48] [49] Post-victory, Francoist repression ensued, including executions, imprisonment, and purges of suspected Republicans, intellectuals, and leftists, contributing to the broader pattern of approximately 50,000 to 200,000 extra-judicial deaths across Nationalist-held Spain during and immediately after the war.[50] Under Francisco Franco's dictatorship from 1939 onward, Mallorca's economy remained tied to agriculture—primarily olives, almonds, cereals, and livestock—amid Spain's policy of autarky and international isolation, which exacerbated postwar devastation and led to widespread poverty and stagnation through the 1940s and early 1950s.[51] Gold reserves were depleted, foreign trade collapsed, and the island's GDP per capita lagged behind prewar levels, with limited industrialization and reliance on subsistence farming.[51] This isolation eased slightly after 1950 with U.S. aid and Spain's alignment against communism, but economic recovery was slow until the 1959 Stabilization Plan liberalized trade and encouraged foreign investment.[52] The 1960s marked a pivotal shift as mass tourism exploded under Franco's regime, driven by affordable package holidays from Germany, the UK, and Scandinavia, transforming Mallorca from an agrarian outpost to Europe's premier sun-and-sea destination.[53] Visitor numbers surged from approximately 360,000 in 1960—roughly matching 1930s levels—to over 2 million by 1970, fueled by expanded airport infrastructure at Palma (handling 1.5 million passengers annually by 1969) and rapid hotel construction, often on subdivided agricultural land.[5] [53] This boom pivoted the economy, with tourism generating up to 75% of GDP by the late 20th century, but it spurred land speculation, uneven wealth distribution favoring developers and urban elites, and displacement of traditional farming communities as fertile coastal plots were repurposed for resorts.[54][55]Post-1975 democracy and recent events (including 2024–2025 protests)