Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Spectrum (physical sciences)

View on Wikipedia

In the physical sciences, the term spectrum was introduced first into optics by Isaac Newton in the 17th century, referring to the range of colors observed when white light was dispersed through a prism.[1][2] Soon the term referred to a plot of light intensity or power as a function of frequency or wavelength, also known as a spectral density plot.

Later it expanded to apply to other waves, such as sound waves and sea waves that could also be measured as a function of frequency (e.g., noise spectrum, sea wave spectrum). It has also been expanded to more abstract "signals", whose power spectrum can be analyzed and processed. The term now applies to any signal that can be measured or decomposed along a continuous variable, such as energy in electron spectroscopy or mass-to-charge ratio in mass spectrometry. Spectrum is also used to refer to a graphical representation of the signal as a function of the dependent variable.

Etymology

[edit]In Latin, spectrum means "image" or "apparition", including the meaning "spectre". Spectral evidence is testimony about what was done by spectres of persons not present physically, or hearsay evidence about what ghosts or apparitions of Satan said. It was used to convict a number of persons of witchcraft at Salem, Massachusetts in the late 17th century. The word "spectrum" [Spektrum] was strictly used to designate a ghostly optical afterimage by Goethe in his Theory of Colors and Schopenhauer in On Vision and Colors.

The prefix "spectro-" is used to form words relating to spectra. For example, a spectrometer is a device used to record spectra and spectroscopy is the use of a spectrometer for chemical analysis.Electromagnetic spectrum

[edit]

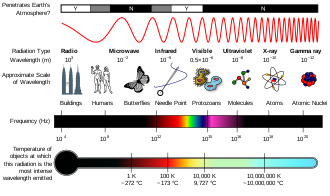

Electromagnetic spectrum refers to the full range of all frequencies of electromagnetic radiation[3] and also to the characteristic distribution of electromagnetic radiation emitted or absorbed by that particular object. Devices used to measure an electromagnetic spectrum are called spectrograph or spectrometer. The visible spectrum is the part of the electromagnetic spectrum that can be seen by the human eye. The wavelength of visible light ranges from 390 to 700 nm.[4] The absorption spectrum of a chemical element or chemical compound is the spectrum of frequencies or wavelengths of incident radiation that are absorbed by the compound due to electron transitions from a lower to a higher energy state. The emission spectrum refers to the spectrum of radiation emitted by the compound due to electron transitions from a higher to a lower energy state.

Light from many different sources contains various colors, each with its own brightness or intensity. A rainbow, or prism, sends these component colors in different directions, making them individually visible at different angles. A graph of the intensity plotted against the frequency (showing the brightness of each color) is the frequency spectrum of the light. When all the visible frequencies are present equally, the perceived color of the light is white, and the spectrum is a flat line. Therefore, flat-line spectra in general are often referred to as white, whether they represent light or another type of wave phenomenon (sound, for example, or vibration in a structure).

In radio and telecommunications, the frequency spectrum can be shared among many different broadcasters. The radio spectrum is the part of the electromagnetic spectrum corresponding to frequencies lower below 300 GHz, which corresponds to wavelengths longer than about 1 mm. The microwave spectrum corresponds to frequencies between 300 MHz (0.3 GHz) and 300 GHz and wavelengths between one meter and one millimeter.[5][6] Each broadcast radio and TV station transmits a wave on an assigned frequency range, called a channel. When many broadcasters are present, the radio spectrum consists of the sum of all the individual channels, each carrying separate information, spread across a wide frequency spectrum. Any particular radio receiver will detect a single function of amplitude (voltage) vs. time. The radio then uses a tuned circuit or tuner to select a single channel or frequency band and demodulate or decode the information from that broadcaster. If we made a graph of the strength of each channel vs. the frequency of the tuner, it would be the frequency spectrum of the antenna signal.

In astronomical spectroscopy, the strength, shape, and position of absorption and emission lines, as well as the overall spectral energy distribution of the continuum, reveal many properties of astronomical objects. Stellar classification is the categorisation of stars based on their characteristic electromagnetic spectra. The spectral flux density is used to represent the spectrum of a light-source, such as a star.

In radiometry and colorimetry (or color science more generally), the spectral power distribution (SPD) of a light source is a measure of the power contributed by each frequency or color in a light source. The light spectrum is usually measured at points (often 31) along the visible spectrum, in wavelength space instead of frequency space, which makes it not strictly a spectral density. Some spectrophotometers can measure increments as fine as one to two nanometers and even higher resolution devices with resolutions less than 0.5 nm have been reported.[7] the values are used to calculate other specifications and then plotted to show the spectral attributes of the source. This can be helpful in analyzing the color characteristics of a particular source.

Mass spectrum

[edit]

A plot of ion abundance as a function of mass-to-charge ratio is called a mass spectrum. It can be produced by a mass spectrometer instrument.[8] The mass spectrum can be used to determine the quantity and mass of atoms and molecules. Tandem mass spectrometry is used to determine molecular structure.

Energy spectrum

[edit]In physics, the energy spectrum of a particle is the number of particles or intensity of a particle beam as a function of particle energy. Examples of techniques that produce an energy spectrum are alpha-particle spectroscopy, electron energy loss spectroscopy, and mass-analyzed ion-kinetic-energy spectrometry.

Displacement

[edit]Oscillatory displacements, including vibrations, can also be characterized spectrally.

- For water waves, see wave spectrum and tide spectrum.

- Sound and non-audible acoustic waves can also be characterized in terms of its spectral density, for example, timbre and musical acoustics.

-

Spectrum of tides measured at Fort Pulaski in 2012.[10] This Fourier transform was computed using SourceForge[11]

Acoustical measurement

[edit]In acoustics, a spectrogram is a visual representation of the frequency spectrum of sound as a function of time or another variable.

A source of sound can have many different frequencies mixed. A musical tone's timbre is characterized by its harmonic spectrum. Sound in our environment that we refer to as noise includes many different frequencies. When a sound signal contains a mixture of all audible frequencies, distributed equally over the audio spectrum, it is called white noise.[12]

The spectrum analyzer is an instrument which can be used to convert the sound wave of the musical note into a visual display of the constituent frequencies. This visual display is referred to as an acoustic spectrogram. Software based audio spectrum analyzers are available at low cost, providing easy access not only to industry professionals, but also to academics, students and the hobbyist. The acoustic spectrogram generated by the spectrum analyzer provides an acoustic signature of the musical note. In addition to revealing the fundamental frequency and its overtones, the spectrogram is also useful for analysis of the temporal attack, decay, sustain, and release of the musical note.

-

Approximate frequency ranges corresponding to ultrasound, with rough guide of some applications

-

Acoustic spectrogram of the words "Oh, no!" said by a young girl, showing how the discrete spectrum of the sound (bright orange lines) changes with time (the horizontal axis)

-

Spectrogram of dolphin vocalizations

Continuous versus discrete spectra

[edit]

In the physical sciences, the spectrum of a physical quantity (such as energy) may be called continuous if it is non-zero over the whole spectrum domain (such as frequency or wavelength) or discrete if it attains non-zero values only in a discrete set over the independent variable, with band gaps between pairs of spectral bands or spectral lines.[13]

The classical example of a continuous spectrum, from which the name is derived, is the part of the spectrum of the light emitted by excited atoms of hydrogen that is due to free electrons becoming bound to a hydrogen ion and emitting photons, which are smoothly spread over a wide range of wavelengths, in contrast to the discrete lines due to electrons falling from some bound quantum state to a state of lower energy. As in that classical example, the term is most often used when the range of values of a physical quantity may have both a continuous and a discrete part, whether at the same time or in different situations. In quantum systems, continuous spectra (as in bremsstrahlung and thermal radiation) are usually associated with free particles, such as atoms in a gas, electrons in an electron beam, or conduction band electrons in a metal. In particular, the position and momentum of a free particle has a continuous spectrum, but when the particle is confined to a limited space its spectrum becomes discrete.

Often a continuous spectrum may be just a convenient model for a discrete spectrum whose values are too close to be distinguished, as in the phonons in a crystal.

The continuous and discrete spectra of physical systems can be modeled in functional analysis as different parts in the decomposition of the spectrum of a linear operator acting on a function space, such as the Hamiltonian operator.

The classical example of a discrete spectrum (for which the term was first used) is the characteristic set of discrete spectral lines seen in the emission spectrum and absorption spectrum of isolated atoms of a chemical element, which only absorb and emit light at particular wavelengths. The technique of spectroscopy is based on this phenomenon.

Discrete spectra are seen in many other phenomena, such as vibrating strings, microwaves in a metal cavity, sound waves in a pulsating star, and resonances in high-energy particle physics. The general phenomenon of discrete spectra in physical systems can be mathematically modeled with tools of functional analysis, specifically by the decomposition of the spectrum of a linear operator acting on a functional space.

In classical mechanics

[edit]In classical mechanics, discrete spectra are often associated to waves and oscillations in a bounded object or domain. Mathematically they can be identified with the eigenvalues of differential operators that describe the evolution of some continuous variable (such as strain or pressure) as a function of time and/or space.

Discrete spectra are also produced by some non-linear oscillators where the relevant quantity has a non-sinusoidal waveform. Notable examples are the sound produced by the vocal cords of mammals.[14][15]: p.684 and the stridulation organs of crickets,[16] whose spectrum shows a series of strong lines at frequencies that are integer multiples (harmonics) of the oscillation frequency.

A related phenomenon is the appearance of strong harmonics when a sinusoidal signal (which has the ultimate "discrete spectrum", consisting of a single spectral line) is modified by a non-linear filter; for example, when a pure tone is played through an overloaded amplifier,[17] or when an intense monochromatic laser beam goes through a non-linear medium.[18] In the latter case, if two arbitrary sinusoidal signals with frequencies f and g are processed together, the output signal will generally have spectral lines at frequencies |mf + ng|, where m and n are any integers.

In quantum mechanics

[edit]In quantum mechanics, the discrete spectrum of an observable refers to the pure point spectrum of eigenvalues of the operator used to model that observable.[19][20]

Discrete spectra are usually associated with systems that are bound in some sense (mathematically, confined to a compact space).[citation needed] The position and momentum operators have continuous spectra in an infinite domain, but a discrete (quantized) spectrum in a compact domain and the same properties of spectra hold for angular momentum, Hamiltonians and other operators of quantum systems.

The quantum harmonic oscillator and the hydrogen atom are examples of physical systems in which the Hamiltonian has a discrete spectrum. In the case of the hydrogen atom the spectrum has both a continuous and a discrete part, the continuous part representing the ionization.

-

The discrete part of the emission spectrum of hydrogen

-

Spectrum of sunlight above the atmosphere (yellow) and at sea level (red), revealing an absorption spectrum with a discrete part (such as the line due to O

2) and a continuous part (such as the bands labeled H

2O) -

Spectrum of light emitted by a deuterium lamp, showing a discrete part (tall sharp peaks) and a continuous part (smoothly varying between the peaks). The smaller peaks and valleys may be due to measurement errors rather than discrete spectral lines.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^

OpenStax Astronomy, "Spectroscopy in Astronomy". OpenStax CNX. September 29, 2016 "OpenStax CNX". Archived from the original on February 17, 2017. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

OpenStax Astronomy, "Spectroscopy in Astronomy". OpenStax CNX. September 29, 2016 "OpenStax CNX". Archived from the original on February 17, 2017. Retrieved February 17, 2017.

- ^ Newton, Isaac (1671). "A letter of Mr. Isaac Newton … containing his new theory about light and colours …". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 6 (80): 3075–3087. Bibcode:1671RSPT....6.3075N. doi:10.1098/rstl.1671.0072. The word "spectrum" to describe a band of colors that has been produced, by refraction or diffraction, from a beam of light first appears on p. 3076.

- ^ "Electromagnetic spectrum". Imagine the Universe! Dictionary. NASA. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ^ Starr, Cecie (2005). Biology: Concepts and Applications. Thomson Brooks/Cole. p. 94. ISBN 0-534-46226-X.

- ^ Pozar, David M. (1993). Microwave Engineering Addison–Wesley Publishing Company. ISBN 0-201-50418-9.

- ^ Sorrentino, R. and Bianchi, Giovanni (2010) Microwave and RF Engineering Archived August 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, John Wiley & Sons, p. 4, ISBN 047066021X.

- ^ Noui, Louahab; Hill, Jonathan; Keay, Peter J; Wang, Robert Y; Smith, Trevor; Yeung, Ken; Habib, George; Hoare, Mike (2002-02-01). "Development of a high resolution UV spectrophotometer for at-line monitoring of bioprocesses". Chemical Engineering and Processing: Process Intensification. 41 (2): 107–114. Bibcode:2002CEPPI..41..107N. doi:10.1016/S0255-2701(01)00122-2. ISSN 0255-2701.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "mass spectrum". doi:10.1351/goldbook.M03749

- ^ Munk, Walter H. (2010). "Origin and Generation of Waves". Coastal Engineering Proceedings. 1: 1. doi:10.9753/icce.v1.1.

- ^ "Datums - NOAA Tides & Currents". tidesandcurrents.noaa.gov. December 2013. Archived from the original on 2022-12-06. Retrieved 2023-03-22.

- ^ "A More Accurate Fourier Transform". SourceForge. 7 July 2015. Retrieved 2023-03-22.

- ^ "white noise definition". yourdictionary.com. Archived from the original on June 30, 2015.

- ^ "Continuous Spectrum - klinics.lib.kmutt.ac.th". KMUTT: Thailands Science General. 2 (1): 22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-08-20 – via KMUTT.

In physics, a continuous spectrum usually means a set of achievable values for some physical quantity (such as energy or wavelength), best described as an interval of real numbers. It is the opposite of a discrete spectrum, a set of achievable values that are discrete in the mathematical sense where there is a positive gap between each value.

- ^ Hannu Pulakka (2005), Analysis of human voice production using inverse filtering, high-speed imaging, and electroglottography. Master's thesis, Helsinki University of Technology.

- ^ Lindblom, Björn; Sundberg, Johan (2007). "The Human Voice in Speech and Singing". Springer Handbook of Acoustics. New York, NY: Springer New York. pp. 669–712. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-30425-0_16. ISBN 978-0-387-30446-5.

- ^ Popov, A. V.; Shuvalov, V. F.; Markovich, A. M. (1976). "The spectrum of the calling signals, phonotaxis, and the auditory system in the cricket Gryllus bimaculatus". Neuroscience and Behavioral Physiology. 7 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 56–62. doi:10.1007/bf01148749. ISSN 0097-0549. PMID 1028002. S2CID 25407842.

- ^ Paul V. Klipsch (1969), Modulation distortion in loudspeakers Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine Journal of the Audio Engineering Society.

- ^ Armstrong, J. A.; Bloembergen, N.; Ducuing, J.; Pershan, P. S. (1962-09-15). "Interactions between Light Waves in a Nonlinear Dielectric". Physical Review. 127 (6). American Physical Society (APS): 1918–1939. Bibcode:1962PhRv..127.1918A. doi:10.1103/physrev.127.1918. ISSN 0031-899X.

- ^ Simon, B. (1978). "An Overview of Rigorous Scattering Theory". p. 3. S2CID 16913591.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ Teschl, G. (2009). "5.2 The RAGE theorem". Mathematical Methods in Quantum Mechanics (PDF). Providence, R.I: American Mathematical Soc. ISBN 978-0-8218-4660-5.

![Classification of the spectrum of ocean waves according to wave period[9]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/db/Munk_ICCE_1950_Fig1.svg/500px-Munk_ICCE_1950_Fig1.svg.png)

![Spectrum of tides measured at Fort Pulaski in 2012.[10] This Fourier transform was computed using SourceForge[11]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/93/Tides_Fourier_Transform.png/250px-Tides_Fourier_Transform.png)