Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Executive functions

View on Wikipedia

| Neuropsychology |

|---|

|

In cognitive science and neuropsychology, executive functions (collectively referred to as executive function and cognitive control) are a set of cognitive processes that support goal-directed behavior, by regulating thoughts and actions through cognitive control, selecting and successfully monitoring actions that facilitate the attainment of chosen objectives. Executive functions include basic cognitive processes such as attentional control, cognitive inhibition, inhibitory control, working memory, and cognitive flexibility. Higher-order executive functions require the simultaneous use of multiple basic executive functions and include planning and fluid intelligence (e.g., reasoning and problem-solving).[1][2][3][4]

Executive functions gradually develop and change across the lifespan of an individual and can be improved at any time over the course of a person's life.[2] Similarly, these cognitive processes can be adversely affected by a variety of events which affect an individual.[2] Both neuropsychological tests (e.g., the Stroop test) and rating scales (e.g., the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function) are used to measure executive functions. They are usually performed as part of a more comprehensive assessment to diagnose neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Cognitive control and stimulus control, which is associated with operant and classical conditioning, represent opposite processes (internal vs external or environmental, respectively) that compete over the control of an individual's elicited behaviors;[5] in particular, inhibitory control is necessary for overriding stimulus-driven behavioral responses (stimulus control of behavior).[2] The prefrontal cortex is necessary but not solely sufficient for executive functions;[2][6][7] for example, the caudate nucleus and subthalamic nucleus also have a role in mediating inhibitory control.[2][8]

Cognitive control is impaired in addiction,[8] attention deficit hyperactivity disorder,[2][8] autism,[9] and a number of other central nervous system disorders. Stimulus-driven behavioral responses that are associated with a particular rewarding stimulus tend to dominate one's behavior in an addiction.[8]

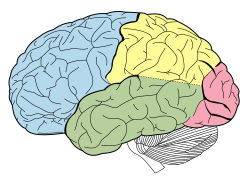

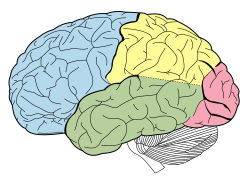

Neuroanatomy

[edit]Historically, the executive functions have been seen as regulated by the prefrontal regions of the frontal lobes,[10][11] but it is still a matter of ongoing debate if that really is the case.[6] Even though articles on prefrontal lobe lesions commonly refer to disturbances of executive functions and vice versa, a review found indications for the sensitivity but not for the specificity of executive function measures to frontal lobe functioning. This means that both frontal and non-frontal brain regions are necessary for intact executive functions. Probably the frontal lobes need to participate in basically all of the executive functions, but they are not the only brain structure involved.[6]

Neuroimaging and lesion studies have identified the functions which are most often associated with the particular regions of the prefrontal cortex and associated areas.[6]

- The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) is involved with "on-line" processing of information such as integrating different dimensions of cognition and behavior.[12] As such, this area has been found to be associated with verbal and design fluency, ability to maintain and shift set, planning, response inhibition, anticipation of conflict stimuli,[13] working memory, organisational skills, reasoning, problem-solving, and abstract thinking.[6][14]

- The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is involved in emotional drives, experience and integration.[12] Associated cognitive functions include inhibition of inappropriate responses, decision making and motivated behaviors. Lesions in this area can lead to low drive states such as apathy, abulia or akinetic mutism and may also result in low drive states for such basic needs as food or drink and possibly decreased interest in social or vocational activities and sex.[12][15]

- The orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) plays a key role in impulse control, maintenance of set, monitoring ongoing behavior and socially appropriate behaviors.[12] The orbitofrontal cortex also has roles in representing the value of rewards based on sensory stimuli and evaluating subjective emotional experiences.[16] Lesions can cause disinhibition, impulsivity, aggressive outbursts, sexual promiscuity and antisocial behavior.[6]

Furthermore, in their review, Alvarez and Emory state that:[6]

The frontal lobes have multiple connections to cortical, subcortical and brain stem sites. The basis of "higher-level" cognitive functions such as inhibition, flexibility of thinking, problem solving, planning, impulse control, concept formation, abstract thinking, and creativity often arise from much simpler, "lower-level" forms of cognition and behavior. Thus, the concept of executive function must be broad enough to include anatomical structures that represent a diverse and diffuse portion of the central nervous system.

The cerebellum also appears to be involved in mediating certain executive functions, as do the ventral tegmental area and the substantia nigra.[17][18][19]

In humans, high contents of cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) is found in frontal neocortical areas, subserving higher cognitive and executive functions, and in the posterior cingulate, a region pivotal for consciousness and higher cognitive processing by its activation.[20]

Hypothesized role

[edit]The executive system is thought to be heavily involved in handling novel situations outside the domain of some of our 'automatic' psychological processes that could be explained by the reproduction of learned schemas or set behaviors. Psychologists Don Norman and Tim Shallice have outlined five types of situations in which routine activation of behavior would not be sufficient for optimal performance:[21][page needed]

- Those that involve planning or decision-making

- Those that involve error correction or troubleshooting

- Situations where responses are not well-rehearsed or contain novel sequences of actions

- Dangerous or technically difficult situations

- Situations that require the overcoming of a strong habitual response or resisting temptation.

A prepotent response is a response for which immediate reinforcement (positive or negative) is available or has been previously associated with that response.[22][page needed]

Executive functions are often invoked when it is necessary to override prepotent responses that might otherwise be automatically elicited by stimuli in the external environment. For example, on being presented with a potentially rewarding stimulus, such as a tasty piece of chocolate cake, a person might have the automatic response to take a bite. However, where such behavior conflicts with internal plans (such as having decided not to eat chocolate cake while on a diet), the executive functions might be engaged to inhibit that response.

Although suppression of these prepotent responses is ordinarily considered adaptive, problems for the development of the individual and the culture arise when feelings of right and wrong are overridden by cultural expectations or when creative impulses are overridden by executive inhibitions.[23][page needed]

Historical perspective

[edit]Although research into the executive functions and their neural basis has increased markedly over recent years, the theoretical framework in which it is situated is not new. In the 1940s, the British psychologist Donald Broadbent drew a distinction between "automatic" and "controlled" processes (a distinction characterized more fully by Shiffrin and Schneider in 1977),[24] and introduced the notion of selective attention, to which executive functions are closely allied. In 1975, the US psychologist Michael Posner used the term "cognitive control" in his book chapter entitled "Attention and cognitive control".[25]

The work of influential researchers such as Michael Posner, Joaquin Fuster, Tim Shallice, and their colleagues in the 1980s (and later Trevor Robbins, Bob Knight, Don Stuss, and others) laid much of the groundwork for recent research into executive functions. For example, Posner proposed that there is a separate "executive" branch of the attentional system, which is responsible for focusing attention on selected aspects of the environment.[26] The British neuropsychologist Tim Shallice similarly suggested that attention is regulated by a "supervisory system", which can override automatic responses in favour of scheduling behaviour on the basis of plans or intentions.[27] Throughout this period, a consensus emerged that this control system is housed in the most anterior portion of the brain, the prefrontal cortex (PFC).

Psychologist Alan Baddeley had proposed a similar system as part of his model of working memory[28] and argued that there must be a component (which he named the "central executive") that allows information to be manipulated in short-term memory (for example, when doing mental arithmetic).

Development

[edit]The executive functions are among the last mental functions to reach maturity. This is due to the delayed maturation of the prefrontal cortex, which is not completely myelinated until well into a person's third decade of life. Development of executive functions tends to occur in spurts, when new skills, strategies, and forms of awareness emerge. These spurts are thought to reflect maturational events in the frontal areas of the brain.[29] Attentional control appears to emerge in infancy and develop rapidly in early childhood. Cognitive flexibility, goal setting, and information processing usually develop rapidly during ages 7–9 and mature by age 12. Executive control typically emerges shortly after a transition period at the beginning of adolescence.[30] It is not yet clear whether there is a single sequence of stages in which executive functions appear, or whether different environments and early life experiences can lead people to develop them in different sequences.[29]

Early childhood

[edit]Inhibitory control and working memory act as basic executive functions that make it possible for more complex executive functions like problem-solving to develop.[31] Inhibitory control and working memory are among the earliest executive functions to appear, with initial signs observed in infants, 7 to 12 months old.[29][30] Then in the preschool years, children display a spurt in performance on tasks of inhibition and working memory, usually between the ages of 3 and 5 years.[29][32] Also during this time, cognitive flexibility, goal-directed behavior, and planning begin to develop.[29] Nevertheless, preschool children do not have fully mature executive functions and continue to make errors related to these emerging abilities – often not due to the absence of the abilities, but rather because they lack the awareness to know when and how to use particular strategies in particular contexts.[33]

Preadolescence

[edit]Preadolescent children continue to exhibit certain growth spurts in executive functions, suggesting that this development does not necessarily occur in a linear manner, along with the preliminary maturing of particular functions as well.[29][30] During preadolescence, children display major increases in verbal working memory;[34] goal-directed behavior (with a potential spurt around 12 years of age);[35] response inhibition and selective attention;[36] and strategic planning and organizational skills.[30][37][38] Additionally, between the ages of 8 and 10, cognitive flexibility in particular begins to match adult levels.[37][38] However, similar to patterns in childhood development, executive functioning in preadolescents is limited because they do not reliably apply these executive functions across multiple contexts as a result of ongoing development of inhibitory control.[29]

Adolescence

[edit]Many executive functions may begin in childhood and preadolescence, such as inhibitory control. Yet, it is during adolescence when the different brain systems become better integrated. At this time, youth implement executive functions, such as inhibitory control, more efficiently and effectively and improve throughout this time period.[39][40] Just as inhibitory control emerges in childhood and improves over time, planning and goal-directed behavior also demonstrate an extended time course with ongoing growth over adolescence.[32][35] Likewise, functions such as attentional control, with a potential spurt at age 15,[35] along with working memory,[39] continue developing at this stage.

Adulthood

[edit]The major change that occurs in the brain in adulthood is the constant myelination of neurons in the prefrontal cortex.[29] At age 20–29, executive functioning skills are at their peak, which allows people of this age to participate in some of the most challenging mental tasks. These skills begin to decline in later adulthood. Working memory and spatial span are areas where decline is most readily noted. Cognitive flexibility, however, has a late onset of impairment and does not usually start declining until around age 70 in normally functioning adults.[29] Impaired executive functioning has been found to be the best predictor of functional decline in the elderly.[41]

Exercise, even at light intensity, significantly improves executive function with the strongest effects seen in children, adolescents, and individuals with ADHD. Low- to moderate-intensity exercise was particularly effective in enhancing these higher-order cognitive processes.[42]

Models

[edit]Top-down inhibitory control

[edit]Aside from facilitatory or amplificatory mechanisms of control, many authors have argued for inhibitory mechanisms in the domain of response control,[43] memory,[44] selective attention,[45] theory of mind,[46][47] emotion regulation,[48] as well as social emotions such as empathy.[49] A recent review on this topic argues that active inhibition is a valid concept in some domains of psychology/cognitive control.[50]

Working memory model

[edit]One influential model is Baddeley's multicomponent model of working memory, which is composed of a central executive system that regulates three subsystems: the phonological loop, which maintains verbal information; the visuospatial sketchpad, which maintains visual and spatial information; and the more recently developed episodic buffer that integrates short-term and long-term memory, holding and manipulating a limited amount of information from multiple domains in temporal and spatially sequenced episodes.[28][51]

Researchers have found significant positive effects of biofeedback-enhanced relaxation on memory and inhibition in children.[52] Biofeedback is a mind-body tool where people can learn to control and regulate their body to improve and control their executive functioning skills. To measure one's processes, researchers use their heart rate and or respiratory rates.[53] Biofeedback-relaxation includes music therapy, art, and other mindfulness activities.[53]

Executive functioning skills are important for many reasons, including children's academic success and social emotional development. According to the study "The Efficacy of Different Interventions to Foster Children's Executive Function Skills: A Series of Meta-Analyses", researchers found that it is possible to train executive functioning skills.[52] Researchers conducted a meta-analytic study that looked at the combined effects of prior studies in order to find the overarching effectiveness of different interventions that promote the development of executive functioning skills in children. The interventions included computerized and non-computerized training, physical exercise, art, and mindfulness exercises.[52] However, researchers could not conclude that art activities or physical activities could improve executive functioning skills.[52]

Supervisory attentional system (SAS)

[edit]Another conceptual model is the supervisory attentional system (SAS).[54][55] In this model, contention scheduling is the process where an individual's well-established schemas automatically respond to routine situations while executive functions are used when faced with novel situations. In these new situations, attentional control will be a crucial element to help generate new schema, implement these schema, and then assess their accuracy.

Self-regulatory model

[edit]Russell Barkley proposed a widely known model of executive functioning that is based on self-regulation. Primarily derived from work examining behavioral inhibition, it views executive functions as composed of four main abilities.[56] One element is working memory that allows individuals to resist interfering information. [clarification needed] A second component is the management of emotional responses in order to achieve goal-directed behaviors. Thirdly, internalization of self-directed speech is used to control and sustain rule-governed behavior and to generate plans for problem-solving. Lastly, information is analyzed and synthesized into new behavioral responses to meet one's goals. Changing one's behavioral response to meet a new goal or modify an objective is a higher level skill that requires a fusion of executive functions including self-regulation, and accessing prior knowledge and experiences.

According to this model, the executive system of the human brain provides for the cross-temporal organization of behavior towards goals and the future and coordinates actions and strategies for everyday goal-directed tasks. Essentially, this system permits humans to self-regulate their behavior so as to sustain action and problem-solving toward goals specifically and the future more generally. Thus, executive function deficits pose serious problems for a person's ability to engage in self-regulation over time to attain their goals and anticipate and prepare for the future.[57]

Teaching children self-regulation strategies is a way to improve their inhibitory control and their cognitive flexibility. These skills allow children to manage their emotional responses. These interventions include teaching children executive function-related skills that provide the steps necessary to implement them during classroom activities and educating children on how to plan their actions before acting upon them.[52] Executive functioning skills are how the brain plans and reacts to situations.[52][58] Offering new self-regulation strategies allow children to improve their executive functioning skills by practicing something new. It is also concluded that mindfulness practices are shown to be a significantly effective intervention for children to self-regulate. This includes biofeedback-enhanced relaxation. These strategies support the growth of children's executive functioning skills.[52]

Problem-solving model

[edit]Yet another model of executive functions is a problem-solving framework where executive functions are considered a macroconstruct composed of subfunctions working in different phases to (a) represent a problem, (b) plan for a solution by selecting and ordering strategies, (c) maintain the strategies in short-term memory in order to perform them by certain rules, and then (d) evaluate the results with error detection and error correction.[59]

Lezak's conceptual model

[edit]One of the most widespread conceptual models on executive functions is Lezak's model.[60] This framework proposes four broad domains of volition, planning, purposive action, and effective performance as working together to accomplish global executive functioning needs. While this model may broadly appeal to clinicians and researchers to help identify and assess certain executive functioning components, it lacks a distinct theoretical basis and relatively few attempts at validation.[61]

Miller and Cohen's model

[edit]In 2001, Earl Miller and Jonathan Cohen published their article "An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function", in which they argue that cognitive control is the primary function of the prefrontal cortex (PFC), and that control is implemented by increasing the gain of sensory or motor neurons that are engaged by task- or goal-relevant elements of the external environment.[62] In a key paragraph, they argue:

We assume that the PFC serves a specific function in cognitive control: the active maintenance of patterns of activity that represent goals and the means to achieve them. They provide bias signals throughout much of the rest of the brain, affecting not only visual processes but also other sensory modalities, as well as systems responsible for response execution, memory retrieval, emotional evaluation, etc. The aggregate effect of these bias signals is to guide the flow of neural activity along pathways that establish the proper mappings between inputs, internal states, and outputs needed to perform a given task.

Miller and Cohen draw explicitly upon an earlier theory of visual attention that conceptualises perception of visual scenes in terms of competition among multiple representations – such as colors, individuals, or objects.[63] Selective visual attention acts to 'bias' this competition in favour of certain selected features or representations. For example, imagine that you are waiting at a busy train station for a friend who is wearing a red coat. You are able to selectively narrow the focus of your attention to search for red objects, in the hope of identifying your friend. Desimone and Duncan argue that the brain achieves this by selectively increasing the gain of neurons responsive to the color red, such that output from these neurons is more likely to reach a downstream processing stage, and, as a consequence, to guide behaviour. According to Miller and Cohen, this selective attention mechanism is in fact just a special case of cognitive control – one in which the biasing occurs in the sensory domain. According to Miller and Cohen's model, the PFC can exert control over input (sensory) or output (response) neurons, as well as over assemblies involved in memory, or emotion. Cognitive control is mediated by reciprocal PFC connectivity with the sensory and motor cortices, and with the limbic system. Within their approach, thus, the term "cognitive control" is applied to any situation where a biasing signal is used to promote task-appropriate responding, and control thus becomes a crucial component of a wide range of psychological constructs such as selective attention, error monitoring, decision-making, memory inhibition, and response inhibition.

Miyake and Friedman's model

[edit]Miyake and Friedman's theory of executive functions proposes that there are three aspects of executive functions: updating, inhibition, and shifting.[64] A cornerstone of this theoretical framework is the understanding that individual differences in executive functions reflect both unity (i.e., common EF skills) and diversity of each component (e.g., shifting-specific). In other words, aspects of updating, inhibition, and shifting are related, yet each remains a distinct entity. First, updating is defined as the continuous monitoring and quick addition or deletion of contents within one's working memory. Second, inhibition is one's capacity to supersede responses that are prepotent in a given situation. Third, shifting is one's cognitive flexibility to switch between different tasks or mental states.

Miyake and Friedman also suggest that the current body of research in executive functions suggest four general conclusions about these skills. The first conclusion is the unity and diversity aspects of executive functions.[65][66] Second, recent studies suggest that much of one's EF skills are inherited genetically, as demonstrated in twin studies.[67] Third, clean measures of executive functions can differentiate between normal and clinical or regulatory behaviors, such as ADHD.[68][69][70] Last, longitudinal studies demonstrate that EF skills are relatively stable throughout development.[71][72]

Banich's "cascade of control" model

[edit]This model from 2009 integrates theories from other models, and involves a sequential cascade of brain regions involved in maintaining attentional sets in order to arrive at a goal. In sequence, the model assumes the involvement of the posterior dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), the mid-DLPFC, and the posterior and anterior dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (ACC).[73]

The cognitive task used in the article is selecting a response in the Stroop task, among conflicting color and word responses, specifically a stimulus where the word "green" is printed in red ink. The posterior DLPFC creates an appropriate attentional set, or rules for the brain to accomplish the current goal. For the Stroop task, this involves activating the areas of the brain involved in color perception, and not those involved in word comprehension. It counteracts biases and irrelevant information, like the fact that the semantic perception of the word is more salient to most people than the color in which it is printed.

Next, the mid-DLPFC selects the representation that will fulfill the goal. The task-relevant information must be separated from other sources of information in the task. In the example, this means focusing on the ink color and not the word.

The posterior dorsal ACC is next in the cascade, and it is responsible for response selection. This is where the decision is made whether the Stroop task participant will say "green" (the written word and the incorrect answer) or "red" (the font color and correct answer).

Following the response, the anterior dorsal ACC is involved in response evaluation, deciding whether one's response were correct or incorrect. Activity in this region increases when the probability of an error is higher.

The activity of any of the areas involved in this model depends on the efficiency of the areas that came before it. If the DLPFC imposes a lot of control on the response, the ACC will require less activity.[73]

Recent work using individual differences in cognitive style has shown exciting support for this model. Researchers had participants complete an auditory version of the Stroop task, in which either the location or semantic meaning of a directional word had to be attended to. Participants that either had a strong bias toward spatial or semantic information (different cognitive styles) were then recruited to participate in the task. As predicted, participants that had a strong bias toward spatial information had more difficulty paying attention to the semantic information and elicited increased electrophysiological activity from the ACC. A similar activity pattern was also found for participants that had a strong bias toward verbal information when they tried to attend to spatial information.[74]

Assessment

[edit]Assessment of executive functions involves gathering data from several sources and synthesizing the information to look for trends and patterns across time and settings. Apart from standardized neuropsychological tests, other measures can and should be used, such as behaviour checklists, observations, interviews, and work samples. From these, conclusions may be drawn on the use of executive functions.[75]

There are several different kinds of instruments (e.g., performance based, self-report) that measure executive functions across development. These assessments can serve a diagnostic purpose for a number of clinical populations.

- Behavioural Assessment of Dysexecutive Syndrome (BADS)[76]

- Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF). Ages 2-90 covered by different versions of the scale.[76]

- Barkley Deficits in Executive Functioning Scales (BDEFS)[77]

- Behavioral Dyscontrol Scale (BDS)[78]

- Comprehensive Executive Function Inventory (CEFI)[79]

- CogScreen[80]

- Continuous Performance Task (CPT)[81]

- Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT)[82]

- d2 Test of Attention[83]

- Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS)[84]

- Digit Span Test[84]

- Ruff Figural Fluency Test[85]

- Halstead Category Test[86]

- Hayling and Brixton tests[87][88]

- Iowa gambling task[89]

- Jansari assessment of Executive Functions (JEF)[90]

- Kaplan Baycrest Neurocognitive Assessment (KBNA)[91]

- Kaufman Short Neuropsychological Assessment[92]

- Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test (PASAT)[93]

- Pediatric Attention Disorders Diagnostic Screener (PADDS)[94]

- Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure[84]

- Stroop Test[95]

- Test of Variables of Attention (T.O.V.A.)[96]

- Tower of London Test[97]

- Trail-Making Test (TMT) or Trails A & B[95]

- Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST)[95]

- Symbol Digit Modalities Test[98]

Experimental evidence

[edit]The executive system has been traditionally quite hard to define, mainly due to what psychologist Paul W. Burgess calls a lack of "process-behaviour correspondence".[99] That is, there is no single behavior that can in itself be tied to executive function, or indeed executive dysfunction. For example, it is quite obvious what reading-impaired patients cannot do, but it is not so obvious what exactly executive-impaired patients might be incapable of.

This is largely due to the nature of the executive system itself. It is mainly concerned with the dynamic, "online" co-ordination of cognitive resources, and, hence, its effect can be observed only by measuring other cognitive processes. In similar manner, it does not always fully engage outside of real-world situations. As neurologist Antonio Damasio has reported, a patient with severe day-to-day executive problems may still pass paper-and-pencil or lab-based tests of executive function.[100]

Theories of the executive system were largely driven by observations of patients with frontal lobe damage. They exhibited disorganized actions and strategies for everyday tasks (a group of behaviors now known as dysexecutive syndrome) although they seemed to perform normally when clinical or lab-based tests were used to assess more fundamental cognitive functions such as memory, learning, language, and reasoning. It was hypothesized that, to explain this unusual behaviour, there must be an overarching system that co-ordinates other cognitive resources.[101]

Much of the experimental evidence for the neural structures involved in executive functions comes from laboratory tasks such as the Stroop task or the Wisconsin Card Sorting Task (WCST). In the Stroop task, for example, human subjects are asked to name the color that color words are printed in when the ink color and word meaning often conflict (for example, the word "RED" in green ink). Executive functions are needed to perform this task, as the relatively overlearned and automatic behaviour (word reading) has to be inhibited in favour of a less practiced task – naming the ink color. Recent functional neuroimaging studies have shown that two parts of the PFC, the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), are thought to be particularly important for performing this task.

Context-sensitivity of PFC neurons

[edit]Other evidence for the involvement of the PFC in executive functions comes from single-cell electrophysiology studies in non-human primates, such as the macaque monkey, which have shown that (in contrast to cells in the posterior brain) many PFC neurons are sensitive to a conjunction of a stimulus and a context. For example, PFC cells might respond to a green cue in a condition where that cue signals that a leftwards fast movement of the eyes and the head should be made, but not to a green cue in another experimental context. This is important, because the optimal deployment of executive functions is invariably context-dependent.

One example from Miller & Cohen involves a pedestrian crossing the street. In the United States, where cars drive on the right side of the road, an American learns to look left when crossing the street. However, if that American visits a country where cars drive on the left, such as the United Kingdom, then the opposite behavior would be required (looking to the right). In this case, the automatic response needs to be suppressed (or augmented) and executive functions must make the American look to the right while in the UK.

Neurologically, this behavioural repertoire clearly requires a neural system that is able to integrate the stimulus (the road) with a context (US or UK) to cue a behaviour (look left or look right). Current evidence suggests that neurons in the PFC appear to represent precisely this sort of information.[citation needed] Other evidence from single-cell electrophysiology in monkeys implicates ventrolateral PFC (inferior prefrontal convexity) in the control of motor responses. For example, cells that increase their firing rate to NoGo signals[102] as well as a signal that says "don't look there!"[103] have been identified.

Attentional biasing in sensory regions

[edit]Electrophysiology and functional neuroimaging studies involving human subjects have been used to describe the neural mechanisms underlying attentional biasing. Most studies have looked for activation at the 'sites' of biasing, such as in the visual or auditory cortices. Early studies employed event-related potentials to reveal that electrical brain responses recorded over left and right visual cortex are enhanced when the subject is instructed to attend to the appropriate (contralateral) side of space.[104]

The advent of bloodflow-based neuroimaging techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) has more recently permitted the demonstration that neural activity in a number of sensory regions, including color-, motion-, and face-responsive regions of visual cortex, is enhanced when subjects are directed to attend to that dimension of a stimulus, suggestive of gain control in sensory neocortex. For example, in a typical study, Liu and coworkers[105] presented subjects with arrays of dots moving to the left or right, presented in either red or green. Preceding each stimulus, an instruction cue indicated whether subjects should respond on the basis of the colour or the direction of the dots. Even though colour and motion were present in all stimulus arrays, fMRI activity in colour-sensitive regions (V4) was enhanced when subjects were instructed to attend to the colour, and activity in motion-sensitive regions was increased when subjects were cued to attend to the direction of motion. Several studies have also reported evidence for the biasing signal prior to stimulus onset, with the observation that regions of the frontal cortex tend to come active prior to the onset of an expected stimulus.[106]

Connectivity between the PFC and sensory regions

[edit]Despite the growing currency of the 'biasing' model of executive functions, direct evidence for functional connectivity between the PFC and sensory regions when executive functions are used, is to date rather sparse.[107] Indeed, the only direct evidence comes from studies in which a portion of frontal cortex is damaged, and a corresponding effect is observed far from the lesion site, in the responses of sensory neurons.[108][109] However, few studies have explored whether this effect is specific to situations where executive functions are required. Other methods for measuring connectivity between distant brain regions, such as correlation in the fMRI response, have yielded indirect evidence that the frontal cortex and sensory regions communicate during a variety of processes thought to engage executive functions, such as working memory,[110] but more research is required to establish how information flows between the PFC and the rest of the brain when executive functions are used. As an early step in this direction, an fMRI study on the flow of information processing during visuospatial reasoning has provided evidence for causal associations (inferred from the temporal order of activity) between sensory-related activity in occipital and parietal cortices and activity in posterior and anterior PFC.[111] Such approaches can further elucidate the distribution of processing between executive functions in PFC and the rest of the brain.

Bilingualism and executive functions

[edit]A growing body of research demonstrates that bilinguals might show advantages in executive functions, specifically inhibitory control and task switching.[112][113][114][page needed] A possible explanation for this is that speaking two languages requires controlling one's attention and choosing the correct language to speak. Across development, bilingual infants,[115] children,[113] and elderly[116] show a bilingual advantage when it comes to executive functioning. The advantage does not seem to manifest in younger adults.[112] Bimodal bilinguals, or people who speak one oral language and one sign language, do not demonstrate this bilingual advantage in executive functioning tasks.[117] This may be because one is not required to actively inhibit one language in order to speak the other. Bilingual individuals also seem to have an advantage in an area known as conflict processing, which occurs when there are multiple representations of one particular response (for example, a word in one language and its translation in the individual's other language).[118] Specifically, the lateral prefrontal cortex has been shown to be involved with conflict processing. However, there are still some doubts. In a meta-analytic review, researchers concluded that bilingualism did not enhance executive functioning in adults.[119]

In disease or disorder

[edit]The study of executive function in Parkinson's disease suggests subcortical areas such as the amygdala, hippocampus and basal ganglia are important in these processes. Dopamine modulation of the prefrontal cortex is responsible for the efficacy of dopaminergic drugs on executive function, and gives rise to the Yerkes–Dodson Curve.[120] The inverted U represents decreased executive functioning with excessive arousal (or increased catecholamine release during stress), and decreased executive functioning with insufficient arousal.[121] The low activity polymorphism of catechol-O-methyltransferase is associated with slight increase in performance on executive function tasks in healthy persons.[122]

Executive functions are impaired in multiple disorders including anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, schizophrenia and autism.[123] Lesions to the prefrontal cortex, such as in the case of Phineas Gage, may also result in deficits of executive function. Damage to these areas may also manifest in deficits of other areas of function, such as motivation, and social functioning.[124]

Future directions

[edit]Other important evidence for executive functions processes in the prefrontal cortex have been described. One widely cited review article[125] emphasizes the role of the medial part of the PFC in situations where executive functions are likely to be engaged – for example, where it is important to detect errors, identify situations where stimulus conflict may arise, make decisions under uncertainty, or when a reduced probability of obtaining favourable performance outcomes is detected. This review, like many others,[126] highlights interactions between medial and lateral PFC, whereby posterior medial frontal cortex signals the need for increased executive functions and sends this signal on to areas in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex that actually implement control. Yet there has been no compelling evidence at all that this view is correct, and, indeed, one article showed that patients with lateral PFC damage had reduced ERNs (a putative sign of dorsomedial monitoring/error-feedback)[127] – suggesting, if anything, that the direction of flow of the control could be in the reverse direction. Another prominent theory[128] emphasises that interactions along the perpendicular axis of the frontal cortex, arguing that a 'cascade' of interactions between anterior PFC, dorsolateral PFC, and premotor cortex guides behaviour in accordance with past context, present context, and current sensorimotor associations, respectively.

Recent research on network energy in brain functional connectivity reveals that energy is selectively allocated to relevant brain networks during cognitive tasks. Canonical networks involved in executive functions, such as the prefrontal cortex in working memory tasks, exhibit efficient network organization, requiring a smaller share of energy.[129]

Advances in neuroimaging techniques have allowed studies of genetic links to executive functions, with the goal of using the imaging techniques as potential endophenotypes for discovering the genetic causes of executive function.[130]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 6: Widely Projecting Systems: Monoamines, Acetylcholine, and Orexin". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 155–157. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

DA has multiple actions in the prefrontal cortex. It promotes the "cognitive control" of behavior: the selection and successful monitoring of behavior to facilitate attainment of chosen goals. Aspects of cognitive control in which DA plays a role include working memory, the ability to hold information "on line" in order to guide actions, suppression of prepotent behaviors that compete with goal-directed actions, and control of attention and thus the ability to overcome distractions. ... Noradrenergic projections from the LC thus interact with dopaminergic projections from the VTA to regulate cognitive control.

- ^ a b c d e f g Diamond A (2013). "Executive functions". Annual Review of Psychology. 64: 135–168. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750. PMC 4084861. PMID 23020641.

Core EFs are inhibition [response inhibition (self-control—resisting temptations and resisting acting impulsively) and interference control (selective attention and cognitive inhibition)], working memory, and cognitive flexibility (including creatively thinking "outside the box," seeing anything from different perspectives, and quickly and flexibly adapting to changed circumstances). ... EFs and prefrontal cortex are the first to suffer, and suffer disproportionately, if something is not right in your life. They suffer first, and most, if you are stressed (Arnsten 1998, Liston et al. 2009, Oaten & Cheng 2005), sad (Hirt et al. 2008, von Hecker & Meiser 2005), lonely (Baumeister et al. 2002, Cacioppo & Patrick 2008, Campbell et al. 2006, Tun et al. 2012), sleep deprived (Barnes et al. 2012, Huang et al. 2007), or not physically fit (Best 2010, Chaddock et al. 2011, Hillman et al. 2008). Any of these can cause you to appear to have a disorder of EFs, such as ADHD, when you do not. You can see the deleterious effects of stress, sadness, loneliness, and lack of physical health or fitness at the physiological and neuroanatomical level in the prefrontal cortex and at the behavioral level in worse EFs (poorer reasoning and problem-solving, forgetting things, and impaired ability to exercise discipline and self-control). ...

EFs can be improved (Diamond & Lee 2011, Klingberg 2010). ... At any age across the life cycle EFs can be improved, including in the elderly and in infants. There has been much work with excellent results on improving EFs in the elderly by improving physical fitness (Erickson & Kramer 2009, Voss et al. 2011) ... Inhibitory control (one of the core EFs) involves being able to control one's attention, behavior, thoughts, and/or emotions to override a strong internal predisposition or external lure, and instead do what's more appropriate or needed. Without inhibitory control we would be at the mercy of impulses, old habits of thought or action (conditioned responses), and/or stimuli in the environment that pull us this way or that. Thus, inhibitory control makes it possible for us to change and for us to choose how we react and how we behave rather than being unthinking creatures of habit. It doesn't make it easy. Indeed, we usually are creatures of habit and our behavior is under the control of environmental stimuli far more than we usually realize, but having the ability to exercise inhibitory control creates the possibility of change and choice. ... The subthalamic nucleus appears to play a critical role in preventing such impulsive or premature responding (Frank 2006).

Figure 4: Executive functions and related terms - ^ Chan RC, Shum D, Toulopoulou T, Chen EY (March 2008). "Assessment of executive functions: review of instruments and identification of critical issues". Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 23 (2): 201–216. doi:10.1016/j.acn.2007.08.010. PMID 18096360.

The term "executive functions" is an umbrella term comprising a wide range of cognitive processes and behavioral competencies which include verbal reasoning, problem-solving, planning, sequencing, the ability to sustain attention, resistance to interference, utilization of feedback, multitasking, cognitive flexibility, and the ability to deal with novelty (Burgess, Veitch, de lacy Costello, & Shallice, 2000; Damasio, 1995; Grafman & Litvan, 1999; Shallice, 1988; Stuss & Benson, 1986; Stuss, Shallice, Alexander, & Picton, 1995).

- ^ Miyake A, Friedman NP (2012-01-31). "The Nature and Organization of Individual Differences in Executive Functions: Four General Conclusions". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 21 (1): 8–14. doi:10.1177/0963721411429458. ISSN 0963-7214. PMC 3388901. PMID 22773897.

- ^ Washburn DA (2016). "The Stroop effect at 80: The competition between stimulus control and cognitive control". Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior. 105 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1002/jeab.194. PMID 26781048.

Today, arguably more than at any time in history, the constructs of attention, executive functioning, and cognitive control seem to be pervasive and preeminent in research and theory. Even within the cognitive framework, however, there has long been an understanding that behavior is multiply determined, and that many responses are relatively automatic, unattended, contention-scheduled, and habitual. Indeed, the cognitive flexibility, response inhibition, and self-regulation that appear to be hallmarks of cognitive control are noteworthy only in contrast to responses that are relatively rigid, associative, and involuntary.

- ^ a b c d e f g Alvarez JA, Emory E (2006). "Executive function and the frontal lobes: A meta-analytic review". Neuropsychology Review. 16 (1): 17–42. doi:10.1007/s11065-006-9002-x. PMID 16794878. S2CID 207222975.

- ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 13: Higher Cognitive Function and Behavioral Control". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 315. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

However, damage to the prefrontal cortex has a significant deleterious effect on social behavior, decision making, and adaptive responding to the changing circumstances of life. ... Several subregions of the prefrontal cortex have been implicated in partly distinct aspects of cognitive control, although these distinctions remain somewhat vaguely defined. The anterior cingulate cortex is involved in processes that require correct decision-making, as seen in conflict resolution (eg, the Stroop test, see in Chapter 16), or cortical inhibition (eg, stopping one task and switching to another). The medial prefrontal cortex is involved in supervisory attentional functions (eg, action-outcome rules) and behavioral flexibility (the ability to switch strategies). The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, the last brain area to undergo myelination during development in late adolescence, is implicated in matching sensory inputs with planned motor responses. The ventromedial prefrontal cortex seems to regulate social cognition, including empathy. The orbitofrontal cortex is involved in social decision making and in representing the valuations assigned to different experiences.

- ^ a b c d Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 13: Higher Cognitive Function and Behavioral Control". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. pp. 313–321. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4.

• Executive function, the cognitive control of behavior, depends on the prefrontal cortex, which is highly developed in higher primates and especially humans.

• Working memory is a short-term, capacity-limited cognitive buffer that stores information and permits its manipulation to guide decision-making and behavior. ...

These diverse inputs and back projections to both cortical and subcortical structures put the prefrontal cortex in a position to exert what is often called "top-down" control or cognitive control of behavior. ... The prefrontal cortex receives inputs not only from other cortical regions, including association cortex, but also, via the thalamus, inputs from subcortical structures subserving emotion and motivation, such as the amygdala (Chapter 14) and ventral striatum (or nucleus accumbens; Chapter 15). ...

In conditions in which prepotent responses tend to dominate behavior, such as in drug addiction, where drug cues can elicit drug seeking (Chapter 15), or in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; described below), significant negative consequences can result. ... ADHD can be conceptualized as a disorder of executive function; specifically, ADHD is characterized by reduced ability to exert and maintain cognitive control of behavior. Compared with healthy individuals, those with ADHD have diminished ability to suppress inappropriate prepotent responses to stimuli (impaired response inhibition) and diminished ability to inhibit responses to irrelevant stimuli (impaired interference suppression). ... Functional neuroimaging in humans demonstrates activation of the prefrontal cortex and caudate nucleus (part of the striatum) in tasks that demand inhibitory control of behavior. Subjects with ADHD exhibit less activation of the medial prefrontal cortex than healthy controls even when they succeed in such tasks and utilize different circuits. ... Early results with structural MRI show thinning of the cerebral cortex in ADHD subjects compared with age-matched controls in prefrontal cortex and posterior parietal cortex, areas involved in working memory and attention. - ^ Solomon M (13 November 2007). "Cognitive control in autism spectrum disorders". International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience. 26 (2): 239–47. doi:10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2007.11.001. PMC 2695998. PMID 18093787.

- ^ Stuss DT, Alexander MP (2000). "Executive functions and the frontal lobes: A conceptual view". Psychological Research. 63 (3–4): 289–298. doi:10.1007/s004269900007. PMID 11004882. S2CID 28789594.

- ^ Burgess PW, Stuss DT (2017). "Fifty Years of Prefrontal Cortex Research: Impact on Assessment". Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 23 (9–10): 755–767. doi:10.1017/s1355617717000704. PMID 29198274. S2CID 21129441.

- ^ a b c d Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Loring DW (2004). Neuropsychological Assessment (4th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-511121-7. OCLC 456026734.

- ^ Martínez-Molina MP, Valdebenito-Oyarzo G, Soto-Icaza P, Zamorano F, Figueroa-Vargas A, Carvajal-Paredes P, Stecher X, Salinas C, Valero-Cabré A, Polania R, Billeke P (2024). "Lateral prefrontal theta oscillations causally drive a computational mechanism underlying conflict expectation and adaptation". Nature Communications. 15 (1): 9858. Bibcode:2024NatCo..15.9858M. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-54244-8. PMC 11564697. PMID 39543128.

- ^ Clark L, Bechara A, Damasio H, Aitken M, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW (2008). "Differential effects of insular and ventromedial prefrontal cortex lesions on risky decision making". Brain. 131 (5): 1311–1322. doi:10.1093/brain/awn066. PMC 2367692. PMID 18390562.

- ^ Allman JM, Hakeem A, Erwin JM, Nimchinsky E, Hof P (2001). "The anterior cingulate cortex: the evolution of an interface between emotion and cognition". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 935 (1): 107–117. Bibcode:2001NYASA.935..107A. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03476.x. PMID 11411161. S2CID 10507342.

- ^ Rolls ET, Grabenhorst F (2008). "The orbitofrontal cortex and beyond: From affect to decision-making". Progress in Neurobiology. 86 (3): 216–244. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.09.001. PMID 18824074. S2CID 432027.

- ^ Koziol LF, Budding DE, Chidekel D (2012). "From movement to thought: executive function, embodied cognition, and the cerebellum". Cerebellum. 11 (2): 505–25. doi:10.1007/s12311-011-0321-y. PMID 22068584. S2CID 4244931.

- ^ Noroozian M (2014). "The role of the cerebellum in cognition: beyond coordination in the central nervous system". Neurologic Clinics. 32 (4): 1081–104. doi:10.1016/j.ncl.2014.07.005. PMID 25439295.

- ^ Trutti AC, Mulder MJ, Hommel B, Forstmann BU (2019-05-01). "Functional neuroanatomical review of the ventral tegmental area". NeuroImage. 191: 258–268. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.01.062. hdl:11245.1/751fe3c1-b9ab-4e95-842d-929af69887ed. ISSN 1053-8119. PMID 30710678. S2CID 72333763.

- ^ Burns HD, Van Laere K, Sanabria-Bohórquez S, Hamill TG, Bormans G, Eng Ws, Gibson R, Ryan C, Connolly B, Patel S, Krause S, Vanko A, Van Hecken A, Dupont P, De Lepeleire I (2007-06-05). "[18F]MK-9470, a positron emission tomography (PET) tracer for in vivo human PET brain imaging of the cannabinoid-1 receptor". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (23): 9800–9805. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.9800B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703472104. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1877985. PMID 17535893.

- ^ Norman DA, Shallice T (1980). "Attention to action: Willed and automatic control of behaviour". In Gazzaniga MS (ed.). Cognitive neuroscience: a reader. Oxford: Blackwell (published 2000). p. 377. ISBN 978-0-631-21660-5.

- ^ Barkley RA, Murphy KR (2006). Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Clinical Workbook. Vol. 2 (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. ISBN 978-1-59385-227-6. OCLC 314949058.

- ^ Cherkes-Julkowski M (2005). The DYSfunctionality of Executive Function. Apache Junction, AZ: Surviving Education Guides. ISBN 978-0-9765299-2-7. OCLC 77573143.

- ^ Shiffrin RM, Schneider W (March 1977). "Controlled and automatic human information processing: II: Perceptual learning, automatic attending, and a general theory". Psychological Review. 84 (2): 127–90. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.227.1856. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.127.

- ^ Posner MI, Snyder C (1975). "Attention and cognitive control". In Solso RL (ed.). Information processing and cognition: the Loyola symposium. Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates. ISBN 978-0-470-81230-3.

- ^ Posner MI, Petersen SE (1990). "The attention system of the human brain". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 13 (1): 25–42. doi:10.1146/annurev.ne.13.030190.000325. PMID 2183676. S2CID 2995749.

- ^ Shallice T (1988). From neuropsychology to mental structure. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31360-5.

- ^ a b Baddeley AD (1986). Working memory. Oxford psychology series. Vol. 11. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-852116-7. OCLC 13125659.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i De Luca CR, Leventer RJ (2008). "Developmental trajectories of executive functions across the lifespan". In Anderson P, Anderson V, Jacobs R (eds.). Executive functions and the frontal lobes: a lifespan perspective. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis. pp. 24–47. ISBN 978-1-84169-490-0. OCLC 182857040.

- ^ a b c d Anderson PJ (2002). "Assessment and development of executive functioning (EF) in childhood". Child Neuropsychology. 8 (2): 71–82. doi:10.1076/chin.8.2.71.8724. hdl:10818/30790. PMID 12638061. S2CID 26861754.

- ^ Senn TE, Espy KA, Kaufmann PM (2004). "Using path analysis to understand executive function organization in preschool children". Developmental Neuropsychology. 26 (1): 445–464. doi:10.1207/s15326942dn2601_5. PMID 15276904. S2CID 35850139.

- ^ a b Best JR, Miller PH, Jones LL (2009). "Executive functions after age 5: Changes and correlates". Developmental Review. 29 (3): 180–200. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2009.05.002. PMC 2792574. PMID 20161467.

- ^ Espy KA (2004). "Using developmental, cognitive, and neuroscience approaches to understand executive functions in preschool children". Developmental Neuropsychology. 26 (1): 379–384. doi:10.1207/s15326942dn2601_1. PMID 15276900. S2CID 35321260.

- ^ Brocki KC, Bohlin G (2004). "Executive functions in children aged 6 to 13: A dimensional and developmental study;". Developmental Neuropsychology. 26 (2): 571–593. doi:10.1207/s15326942dn2602_3. PMID 15456685. S2CID 5979419.

- ^ a b c Anderson VA, Anderson P, Northam E, Jacobs R, Catroppa C (2001). "Development of executive functions through late childhood and adolescence in an Australian sample". Developmental Neuropsychology. 20 (1): 385–406. doi:10.1207/S15326942DN2001_5. PMID 11827095. S2CID 32454853.

- ^ Klimkeit EI, Mattingley JB, Sheppard DM, Farrow M, Bradshaw JL (2004). "Examining the development of attention and executive functions in children with a novel paradigm". Child Neuropsychology. 10 (3): 201–211. doi:10.1080/09297040409609811. PMID 15590499. S2CID 216140710.

- ^ a b De Luca CR, Wood SJ, Anderson V, Buchanan JA, Proffitt T, Mahony K, Pantelis C (2003). "Normative data from the CANTAB I: Development of executive function over the lifespan". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 25 (2): 242–254. doi:10.1076/jcen.25.2.242.13639. PMID 12754681. S2CID 36829328.

- ^ a b Luciana M, Nelson CA (2002). "Assessment of neuropsychological function through use of the Cambridge Neuropsychological Testing Automated Battery: Performance in 4- to 12-year-old children". Developmental Neuropsychology. 22 (3): 595–624. doi:10.1207/S15326942DN2203_3. PMID 12661972. S2CID 39133614.

- ^ a b Luna B, Garver KE, Urban TA, Lazar NA, Sweeney JA (2004). "Maturation of cognitive processes from late childhood to adulthood". Child Development. 75 (5): 1357–1372. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.498.6633. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00745.x. PMID 15369519.

- ^ Leon-Carrion J, García-Orza J, Pérez-Santamaría FJ (2004). "Development of the inhibitory component of the executive functions in children and adolescents". International Journal of Neuroscience. 114 (10): 1291–1311. doi:10.1080/00207450490476066. PMID 15370187. S2CID 45204519.

- ^ Mansbach WE, Mace RA (2019). "Predicting Functional Dependence in Mild Cognitive Impairment: Differential Contributions of Memory and Executive Functions". The Gerontologist. 59 (5): 925–935. doi:10.1093/geront/gny097. PMID 30137363.

- ^ Singh B, Bennett H, Miatke A, Dumuid D, Curtis R, Ferguson T, Brinsley J, Szeto K, Petersen JM, Gough C, Eglitis E, Simpson CE, Ekegren CL, Smith AE, Erickson KI, Maher C (2025-03-06). "Effectiveness of exercise for improving cognition, memory and executive function: a systematic umbrella review and meta-meta-analysis". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 59 (12). BMJ: bjsports–2024–108589. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2024-108589. ISSN 0306-3674. PMC 12229068. PMID 40049759.

- ^ Aron AR, Poldrack RA (March 2006). "Cortical and subcortical contributions to Stop signal response inhibition: role of the subthalamic nucleus". Journal of Neuroscience. 26 (9): 2424–33. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4682-05.2006. PMC 6793670. PMID 16510720.

- ^ Anderson MC, Green C (March 2001). "Suppressing unwanted memories by executive control". Nature. 410 (6826): 366–9. Bibcode:2001Natur.410..366A. doi:10.1038/35066572. PMID 11268212. S2CID 4403569.

- ^ Tipper SP (May 2001). "Does negative priming reflect inhibitory mechanisms? A review and integration of conflicting views". The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section A. 54 (2): 321–43. doi:10.1080/713755969. PMID 11394050. S2CID 14162232.

- ^ Stone VE, Gerrans P (2006). "What's domain-specific about theory of mind?". Social Neuroscience. 1 (3–4): 309–19. doi:10.1080/17470910601029221. PMID 18633796. S2CID 24446270.

- ^ Decety J, Lamm C (December 2007). "The role of the right temporoparietal junction in social interaction: how low-level computational processes contribute to meta-cognition". Neuroscientist. 13 (6): 580–93. doi:10.1177/1073858407304654. PMID 17911216. S2CID 37026268.

- ^ Ochsner KN, Gross JJ (May 2005). "The cognitive control of emotion". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 9 (5): 242–9. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2005.03.010. PMID 15866151. S2CID 151594.

- ^ Decety J, Grèzes J (March 2006). "The power of simulation: imagining one's own and other's behavior". Brain Research. 1079 (1): 4–14. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2005.12.115. PMID 16460715. S2CID 19807048.

- ^ Aron AR (June 2007). "The neural basis of inhibition in cognitive control". Neuroscientist. 13 (3): 214–28. doi:10.1177/1073858407299288. PMID 17519365. S2CID 41427583.

- ^ Baddeley A (2002). "16 Fractionating the Central Executive". In Knight RL, Stuss DT (eds.). Principles of frontal lobe function. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. pp. 246–260. ISBN 978-0-19-513497-1. OCLC 48383566.

- ^ a b c d e f g Takacs Z, Kassai R (2019). "The Efficacy of Different Interventions to Foster Children's Executive Function Skills: A Series of Meta-Analyses". Psychological Bulletin. 145 (7): 653–697. doi:10.1037/bul0000195. PMID 31033315. S2CID 139105027.

- ^ a b Yu B, Funk M (2018). "Unwind: A Musical Biofeedback for Relaxation assistance". Behaviour & Information Technology. 37 (8): 800–814. doi:10.1080/0144929X.2018.1484515.

- ^ Norman DA, Shallice T (1986) [1976]. "Attention to action: Willed and automatic control of behaviour". In Shapiro DL, Schwartz G (eds.). Consciousness and self-regulation: advances in research. New York: Plenum Press. pp. 1–14. ISBN 978-0-306-33601-0. OCLC 2392770.

- ^ Shallice T, Burgess P, Robertson I (1996). "The domain of supervisory processes and temporal organisation of behaviour". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 351 (1346): 1405–1412. doi:10.1098/rstb.1996.0124. PMID 8941952. S2CID 18631884.

- ^ Barkley RA (1997). "Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: Constructing a unifying theory of ADHD". Psychological Bulletin. 121 (1): 65–94. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.65. PMID 9000892. S2CID 1182504.

- ^ Russell A. Barkley: Executive Functions - What They Are, How They Work, and Why They Evolved. Guilford Press, 2012. ISBN 978-1-4625-0535-7.

- ^ Diamond A (2013). "Executive Functions". Annual Review of Psychology. 64: 135–168. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750. PMC 4084861. PMID 23020641.

- ^ Zelazo PD, Carter A, Reznick J, Frye D (1997). "Early development of executive function: A problem-solving framework". Review of General Psychology. 1 (2): 198–226. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.1.2.198. S2CID 143042967.

- ^ Lezak MD (1995). Neuropsychological assessment (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509031-4. OCLC 925640891.

- ^ Anderson PJ (2008). "Towards a developmental framework of executive function". In Anderson V, Jacobs R, Anderson PJ (eds.). Executive functions and the frontal lobes: A lifespan perspective. New York: Taylor & Francis. pp. 3–21. ISBN 978-1-84169-490-0. OCLC 182857040.

- ^ Miller EK, Cohen JD (2001). "An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 24 (1): 167–202. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167. PMID 11283309. S2CID 7301474.

- ^ Desimone R, Duncan J (1995). "Neural mechanisms of selective visual attention". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 18 (1): 193–222. doi:10.1146/annurev.ne.18.030195.001205. PMID 7605061. S2CID 14290580.

- ^ Miyake A, Friedman NP, Emerson MJ, Witzki AH, Howerter A, Wager TD (2000). "The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex 'frontal lobe' tasks: A latent variable analysis". Cognitive Psychology. 41 (1): 49–100. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.485.1953. doi:10.1006/cogp.1999.0734. PMID 10945922. S2CID 10096387.

- ^ Vaughan L, Giovanello K (2010). "Executive function in daily life: Age-related influences of executive processes on instrumental activities of daily living". Psychology and Aging. 25 (2): 343–355. doi:10.1037/a0017729. PMID 20545419.

- ^ Wiebe SA, Espy KA, Charak D (2008). "Using confirmatory factor analysis to understand executive control in preschool children: I. Latent structure". Developmental Psychology. 44 (2): 573–587. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.44.2.575. PMID 18331145. S2CID 9579710.

- ^ Friedman NP, Miyake A, Young SE, DeFries JC, Corley RP, Hewitt JK (2008). "Individual differences in executive functions are almost entirely genetic in origin". Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 137 (2): 201–225. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.137.2.201. PMC 2762790. PMID 18473654.

- ^ Friedman NP, Haberstick BC, Willcutt EG, Miyake A, Young SE, Corley RP, Hewitt JK (2007). "Greater attention problems during childhood predict poorer executive functioning in late adolescence". Psychological Science. 18 (10): 893–900. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01997.x. PMID 17894607. S2CID 14687502.

- ^ Friedman NP, Miyake A, Robinson JL, Hewitt JK (2011). "Developmental trajectories in toddlers' self restraint predict individual differences in executive functions 14 years later: A behavioral genetic analysis". Developmental Psychology. 47 (5): 1410–1430. doi:10.1037/a0023750. PMC 3168720. PMID 21668099.

- ^ Young SE, Friedman NP, Miyake A, Willcutt EG, Corley RP, Haberstick BC, Hewitt JK (2009). "Behavioral disinhibition: Liability for externalizing spectrum disorders and its genetic and environmental relation to response inhibition across adolescence". Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 118 (1): 117–130. doi:10.1037/a0014657. PMC 2775710. PMID 19222319.

- ^ Mischel W, Ayduk O, Berman MG, Casey BJ, Gotlib IH, Jonides J, Kross E, Teslovich T, Wilson NL, Zayas V, Shoda Y (2011). "'Willpower' over the lifespan: Decomposing self-regulation". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 6 (2): 252–256. doi:10.1093/scan/nsq081. PMC 3073393. PMID 20855294.

- ^ Moffit TE, Arseneault L, Belsky D, Dickson N, Hancox RJ, Harrington H, Houts R, Poulton R, Roberts BW, Ross S, Sears MR, Thomson WM, Caspi A (2011). "A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (7): 2693–2698. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.2693M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1010076108. PMC 3041102. PMID 21262822.

- ^ a b Banich MT (2009). "Executive function: The search for an integrated account" (PDF). Current Directions in Psychological Science. 18 (2): 89–94. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01615.x. S2CID 15935419.

- ^ Buzzell GA, Roberts DM, Baldwin CL, McDonald CG (2013). "An electrophysiological correlate of conflict processing in an auditory spatial Stroop task: The effect of individual differences in navigational style". International Journal of Psychophysiology. 90 (2): 265–71. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.08.008. PMID 23994425.

- ^ Castellanos I, Kronenberger WG, Pisoni DB (2016). "Questionnaire-based assessment of executive functioning: Psychometrics". Applied Neuropsychology: Child. 7 (2): 1–17. doi:10.1080/21622965.2016.1248557. PMC 6260811. PMID 27841670.

Clinical evaluation of EF typically includes an office- based visit involving administration of a battery of neuropsychological assessment instruments. Despite their advantages, however, individually-administered neuro-psychological measures of EF have two primary limitations: First, in most cases, they must be individually administered and scored by a technician or professional in an office setting, which limits their utility for screening or brief assessment purposes. Second, relations between office-based neuropsychological measures of EF and actual behavior in the daily environment are modest (Barkley, 2012), leading to some caution when applying neuropsychological test results to conclusions about behavioral outcomes. As a result of these limitations of office-based neuropsychological tests of EF, parent- and teacher-report behavior checklist measures of EF have been developed for both screening purposes and to complement the results of performance-based neuropsychological testing by providing reports of EF behavior in daily life (Barkley, 2011b; Gioia et al., 2000; Naglieri & Goldstein, 2013). These checklists have the advantage of good psychometrics, strong ecological validity, and high clinical utility as a result of their ease of administration, scoring, and interpretation."

- ^ a b Souissi S, Chamari K, Bellaj T (2022). "Assessment of executive functions in school-aged children: A narrative review". Frontiers in Psychology. 12 991699. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.991699. PMC 9674032. PMID 36405195.

- ^ "Barkley Deficits in Executive Functioning Scale".

- ^ Grigsby J, Kaye K, Robbins LJ (1992). "Reliabilities, norms, and factor structure of the Behavioral Dyscontrol Scale". Perceptual and Motor Skills. 74 (3): 883–892. doi:10.2466/pms.1992.74.3.883. PMID 1608726. S2CID 36759879.

- ^ Naglieri JA, Goldstein S (2014). "Using the Comprehensive Executive Function Inventory (CEFI) to Assess Executive Function: From Theory to Application". Handbook of Executive Functioning. Springer. pp. 223–244. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-8106-5_14. ISBN 978-1-4614-8105-8.

- ^ Chee SM, Bigornia VE, Logsdon DL (January 2021). "The Application of a Computerized Cognitive Screening Tool in Naval Aviators". Military Medicine. 186 (1): 198–204. doi:10.1093/milmed/usaa333. PMID 33499454.

- ^ Escobar-Ruiz V, Arias-Vázquez PI, Tovilla-Zárate CA, Doval E, Jané-Ballabriga MC (2023). "Advances and Challenges in the Assessment of Executive Functions in Under 36 Months: a Scoping Review". Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders. 8 (3): 365–383. doi:10.1007/s41252-023-00366-x.

- ^ Barry D, Bates ME, Labouvie E (May 2008). "FAS and CFL Forms of Verbal Fluency Differ in Difficulty: A Meta-analytic Study". Applied Neuropsychology. 12 (2): 97–106. doi:10.1080/09084280802083863. PMC 3085831. PMID 18568601.

- ^ Arán Filippetti V, Gutierrez M, Krumm G, Mateos D (October 2022). "Convergent validity, academic correlates and age- and SES-based normative data for the d2 Test of attention in children". Applied Neuropsychology. Child. 11 (4): 629–639. doi:10.1080/21622965.2021.1923494. PMID 34033722. S2CID 235200347.

- ^ a b c Nyongesa MK, Ssewanyana D, Mutua AM, Chongwo E, Scerif G, Newton CR, Abubakar A (2019). "Assessing Executive Function in Adolescence: A Scoping Review of Existing Measures and Their Psychometric Robustness". Frontiers in Psychology. 10 311. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00311. PMC 6405510. PMID 30881324.

- ^ Eersel ME, Joosten H, Koerts J, Gansevoort RT, Slaets JP, Izaks GJ (23 March 2015). "Longitudinal Study of Performance on the Ruff Figural Fluency Test in Persons Aged 35 Years or Older". PLOS ONE. 10 (3) e0121411. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1021411V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0121411. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 4370451. PMID 25799403.

- ^ Borkowska AR, Daniluk B, Adamczyk K (7 October 2021). "Significance of the Diagnosis of Executive Functions in Patients with Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 18 (19) 10527. doi:10.3390/ijerph181910527. ISSN 1660-4601. PMC 8507634. PMID 34639827.

- ^ Burgess, P. & Shallice, T. (1997) The Hayling and Brixton Tests. Test manual. Bury St Edmunds, UK: Thames Valley Test Company.

- ^ Martyr A, Boycheva E, Kudlicka A (2017). "Assessing inhibitory control in early-stage Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease using the Hayling Sentence Completion Test". Journal of Neuropsychology. 13 (1): 67–81. doi:10.1111/jnp.12129. hdl:10871/28177. ISSN 1748-6653. PMID 28635178.

- ^ Toplak ME, Sorge GB, Benoit A, West RF, Stanovich KE (1 July 2010). "Decision-making and cognitive abilities: A review of associations between Iowa Gambling Task performance, executive functions, and intelligence". Clinical Psychology Review. 30 (5): 562–581. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.002. ISSN 0272-7358. PMID 20457481.

- ^ Jansari AS, Devlin A, Agnew R, Akesson K, Murphy L, Leadbetter T (2014). "Ecological Assessment of Executive Functions: A New Virtual Reality Paradigm". Brain Impairment. 15 (2): 71–87. doi:10.1017/BrImp.2014.14. S2CID 145343946.

- ^ Freedman M, Leach L, Carmela Tartaglia M, Stokes KA, Goldberg Y, Spring R, Nourhaghighi N, Gee T, Strother SC, Alhaj MO, Borrie M, Darvesh S, Fernandez A, Fischer CE, Fogarty J, Greenberg BD, Gyenes M, Herrmann N, Keren R, Kirstein J, Kumar S, Lam B, Lena S, McAndrews MP, Naglie G, Partridge R, Rajji TK, Reichmann W, Uri Wolf M, Verhoeff NP, Waserman JL, Black SE, Tang-Wai DF (18 July 2018). "The Toronto Cognitive Assessment (TorCA): normative data and validation to detect amnestic mild cognitive impairment". Alzheimer's Research & Therapy. 10 (1): 65. doi:10.1186/s13195-018-0382-y. ISSN 1758-9193. PMC 6052695. PMID 30021658.

- ^ Wuerfel E, Weddige A, Hagmayer Y, Jacob R, Wedekind L, Stark W, Gärtner J (22 March 2018). "Cognitive deficits including executive functioning in relation to clinical parameters in paediatric MS patients". PLOS ONE. 13 (3) e0194873. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1394873W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0194873. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5864068. PMID 29566099.

- ^ Nikravesh M, Jafari Z, Mehrpour M, Kazemi R, Shavaki YA, Hossienifar S, Azizi MP (2017). "The paced auditory serial addition test for working memory assessment: Psychometric properties". Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran. 31: 349–354. doi:10.14196/mjiri.31.61. PMC 5804453. PMID 29445690.

- ^ Newman E, Reddy LA (March 2017). "Diagnostic Utility of the Pediatric Attention Disorders Diagnostic Screener". Journal of Attention Disorders. 21 (5): 372–380. doi:10.1177/1087054714526431. ISSN 1087-0547. PMID 24639402. S2CID 8460518.

- ^ a b c Faria CA, Alves HV, Charchat-Fichman H (2015). "The most frequently used tests for assessing executive functions in aging". Dementia and Neuropsychology. 9 (2): 149–155. doi:10.1590/1980-57642015DN92000009. PMC 5619353. PMID 29213956.

- ^ Memória CM, Muela HC, Moraes NC, Costa-Hong VA, Machado MF, Nitrini R, Bortolotto LA, Yassuda MS (2018). "Applicability of the Test of Variables of Attention – T.O.V.A in Brazilian adults". Dementia & Neuropsychologia. 12 (4): 394–401. doi:10.1590/1980-57642018dn12-040009. ISSN 1980-5764. PMC 6289477. PMID 30546850.

- ^ Nyongesa MK, Ssewanyana D, Mutua AM, Chongwo E, Scerif G, Newton CR, Abubakar A. "Assessing Executive Function in Adolescence: A Scoping Review of Existing Measures and Their Psychometric Robustness". Frontiers in Psychology. 10.

- ^ Benedict RH, DeLuca J, Phillips G, LaRocca N, Hudson LD, Rudick R, Consortium MS (April 2017). "Validity of the Symbol Digit Modalities Test as a cognition performance outcome measure for multiple sclerosis". Multiple Sclerosis. 23 (5): 721–733. doi:10.1177/1352458517690821. PMC 5405816. PMID 28206827.

- ^ Rabbitt P (1997). "Theory and methodology in executive function research". Methodology of frontal and executive function. East Sussex: Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-86377-485-0.

- ^ Saver JL, Damasio AR (1991). "Preserved access and processing of social knowledge in a patient with acquired sociopathy due to ventromedial frontal damage". Neuropsychologia. 29 (12): 1241–9. doi:10.1016/0028-3932(91)90037-9. PMID 1791934. S2CID 23273038.

- ^ Shimamura AP (2000). "The role of the prefrontal cortex in dynamic filtering". Psychobiology. 28 (2): 207–218. doi:10.3758/BF03331979. S2CID 140274181.

- ^ Sakagami M, Tsutsui K, Lauwereyns J, Koizumi M, Kobayashi S, Hikosaka O (1 July 2001). "A code for behavioral inhibition on the basis of color, but not motion, in ventrolateral prefrontal cortex of macaque monkey". The Journal of Neuroscience. 21 (13): 4801–8. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-13-04801.2001. PMC 6762341. PMID 11425907.

- ^ Hasegawa RP, Peterson BW, Goldberg ME (August 2004). "Prefrontal neurons coding suppression of specific saccades". Neuron. 43 (3): 415–25. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2004.07.013. PMID 15294148. S2CID 1769456.

- ^ Hillyard SA, Anllo-Vento L (February 1998). "Event-related brain potentials in the study of visual selective attention". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 95 (3): 781–7. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95..781H. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.3.781. PMC 33798. PMID 9448241.

- ^ Liu T, Slotnick SD, Serences JT, Yantis S (December 2003). "Cortical mechanisms of feature-based attentional control". Cerebral Cortex. 13 (12): 1334–43. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.129.2978. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhg080. PMID 14615298.

- ^ Kastner S, Pinsk MA, De Weerd P, Desimone R, Ungerleider LG (April 1999). "Increased activity in human visual cortex during directed attention in the absence of visual stimulation". Neuron. 22 (4): 751–61. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80734-5. PMID 10230795.

- ^ Miller BT, d'Esposito M (November 2005). "Searching for "the top" in top-down control". Neuron. 48 (4): 535–8. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.002. PMID 16301170. S2CID 7481276.

- ^ Barceló F, Suwazono S, Knight RT (April 2000). "Prefrontal modulation of visual processing in humans". Nature Neuroscience. 3 (4): 399–403. doi:10.1038/73975. PMID 10725931. S2CID 205096636.

- ^ Fuster JM, Bauer RH, Jervey JP (March 1985). "Functional interactions between inferotemporal and prefrontal cortex in a cognitive task". Brain Research. 330 (2): 299–307. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(85)90689-4. PMID 3986545. S2CID 20675580.

- ^ Gazzaley A, Rissman J, d'Esposito M (December 2004). "Functional connectivity during working memory maintenance". Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 4 (4): 580–99. doi:10.3758/CABN.4.4.580. PMID 15849899.

- ^ Shokri-Kojori E, Motes MA, Rypma B, Krawczyk DC (May 2012). "The network architecture of cortical processing in visuo-spatial reasoning". Scientific Reports. 2 (411): 411. Bibcode:2012NatSR...2..411S. doi:10.1038/srep00411. PMC 3355370. PMID 22624092.

- ^ a b Antoniou M (2019). "The Advantages of Bilingualism Debate". Annual Review of Linguistics. 5 (1): 395–415. doi:10.1146/annurev-linguistics-011718-011820. ISSN 2333-9683. S2CID 149812523.