Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Federal Aviation Administration

View on Wikipedia

Seal of the Federal Aviation Administration | |

Flag of the FAA | |

| |

FAA headquarters in Washington, D.C. | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | August 23, 1958 |

| Preceding agency | |

| Jurisdiction | U.S. federal government |

| Headquarters | Orville Wright Federal Building 800 Independence Avenue SW Washington, D.C., U.S. 20591 38°53′13″N 77°1′22″W / 38.88694°N 77.02278°W |

| Annual budget | US$19.807 billion (FY2024) |

| Agency executives |

|

| Parent agency | U.S. Department of Transportation |

| Key document | |

| Website | faa.gov |

| Footnotes | |

| [1][2] | |

| Part of a series on the |

| United States space program |

|---|

|

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is a U.S. federal government agency within the U.S. Department of Transportation that regulates civil aviation in the United States and surrounding international waters.[3]: 12, 16 Its powers include air traffic control, certification of personnel and aircraft, setting standards for airports, and protection of U.S. assets during the launch or re-entry of commercial space vehicles. Powers over neighboring international waters were delegated to the FAA by authority of the International Civil Aviation Organization.

The FAA was created in August 1958 as the Federal Aviation Agency, replacing the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA). In 1967, the FAA became part of the newly formed U.S. Department of Transportation and was renamed the Federal Aviation Administration.

Major functions

[edit]The FAA's roles include:

- Regulating U.S. commercial space transportation

- Regulating air navigation facilities' geometric and flight inspection standards

- Encouraging and developing civil aeronautics, including new aviation technology

- Issuing, suspending, or revoking pilot certificates

- Regulating civil aviation to promote transportation safety in the United States, especially through local offices called Flight Standards District Offices

- Developing and operating a system of air traffic control and navigation for both civil and military aircraft

- Researching and developing the National Airspace System and civil aeronautics

- Developing and carrying out programs to control aircraft noise and other environmental effects of civil aviation

Organizations

[edit]The FAA operates five "lines of business".[4] Their functions are:

- Air Traffic Organization (ATO): provides air navigation service within the National Airspace System. In ATO, employees operate air traffic control facilities comprising Airport Traffic Control Towers (ATCT), Terminal Radar Approach Control Facilities (TRACONs), and Air Route Traffic Control Centers (ARTCC).[5]

- Aviation Safety (AVS): responsible for aeronautical certification of personnel and aircraft, including pilots, airlines, and mechanics.[6]

- Airports (ARP): plans and develops the national airport system; oversees standards for airport safety, inspection, design, construction, and operation. The office awards $3.5 billion annually in grants for airport planning and development.[7]

- Office of Commercial Space Transportation (AST): ensures protection of U.S. assets during the launch or reentry of commercial space vehicles.[8]

- Security and Hazardous Materials Safety (ASH): responsible for risk reduction of terrorism and other crimes and for investigations, materials safety, infrastructure protection, and personnel security.[9]

Regions and Aeronautical Center operations

[edit]

The FAA is headquartered in Washington, D.C.,[10] and also operates the William J. Hughes Technical Center near Atlantic City, New Jersey, for support and research, and the Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, for training. The FAA has nine regional administrative offices:

- Alaskan Region – Anchorage, Alaska

- Northwest Mountain – Seattle, Washington

- Western Pacific – Los Angeles, California

- Southwest – Fort Worth, Texas

- Central – Kansas City, Missouri

- Great Lakes – Chicago, Illinois

- Southern – Atlanta, Georgia

- Eastern – New York, New York

- New England – Boston, Massachusetts

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2023) |

Background

[edit]The Air Commerce Act of May 20, 1926, is the cornerstone of the U.S. federal government's regulation of civil aviation. This landmark legislation was passed at the urging of the aviation industry, whose leaders believed the airplane could not reach its full commercial potential without federal action to improve and maintain safety standards. The Act charged the Secretary of Commerce with fostering air commerce, issuing and enforcing air traffic rules, licensing pilots, certifying aircraft, establishing airways, and operating and maintaining aids to air navigation. The newly created Aeronautics Branch, operating under the Department of Commerce assumed primary responsibility for aviation oversight.

In fulfilling its civil aviation responsibilities, the U.S. Department of Commerce initially concentrated on such functions as safety regulations and the certification of pilots and aircraft. It took over the building and operation of the nation's system of lighted airways, a task initiated by the Post Office Department. The Department of Commerce improved aeronautical radio communications—before the founding of the Federal Communications Commission in 1934, which handles most such matters today—and introduced radio beacons as an effective aid to air navigation.

The Aeronautics Branch was renamed the Bureau of Air Commerce in 1934 to reflect its enhanced status within the Department. As commercial flying increased, the Bureau encouraged a group of airlines to establish the first three centers for providing air traffic control (ATC) along the airways. In 1936, the Bureau itself took over the centers and began to expand the ATC system. The pioneer air traffic controllers used maps, blackboards, and mental calculations to ensure the safe separation of aircraft traveling along designated routes between cities.

In 1938, the Civil Aeronautics Act transferred the federal civil aviation responsibilities from the Commerce Department to a new independent agency, the Civil Aeronautics Authority. The legislation also expanded the government's role by giving the CAA the authority and the power to regulate airline fares and to determine the routes that air carriers would serve.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt split the authority into two agencies in 1940: the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA) and the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB). CAA was responsible for ATC, airman and aircraft certification, safety enforcement, and airway development. CAB was entrusted with safety regulation, accident investigation, and economic regulation of the airlines. The CAA was part of the Department of Commerce. The CAB was an independent federal agency.

On the eve of America's entry into World War II, CAA began to extend its ATC responsibilities to takeoff and landing operations at airports. This expanded role eventually became permanent after the war. The application of radar to ATC helped controllers in their drive to keep abreast of the postwar boom in commercial air transportation. In 1946, meanwhile, Congress gave CAA the added task of administering the federal-aid airport program, the first peacetime program of financial assistance aimed exclusively at development of the nation's civil airports.

Formation

[edit]The approaching era of jet travel (and a series of midair collisions—most notably the 1956 Grand Canyon mid-air collision) prompted passage of the Federal Aviation Act of 1958. This legislation passed the CAA's functions to a new independent body, the Federal Aviation Agency. The act also transferred air safety regulation from the CAB to the FAA, and gave it sole responsibility for a joint civil-military system of air navigation and air traffic control. The FAA's first administrator, Elwood R. Quesada, was a former Air Force general and adviser to President Eisenhower.

The same year witnessed the birth of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), which was created in response to the Soviet Union (USSR) launch of the first manmade satellite. NASA assumed NACA's aeronautical research role.

1960s reorganization

[edit]In 1967, a new U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) combined major federal responsibilities for air and surface transport. The Federal Aviation Agency's name changed to the Federal Aviation Administration as it became one of several agencies (e.g., Federal Highway Administration, Federal Railroad Administration, the Coast Guard, and the Saint Lawrence Seaway Commission) within DOT. The FAA administrator no longer reported directly to the president, but instead to the Secretary of Transportation. New programs and budget requests would have to be approved by DOT, which would then include these requests in the overall budget and submit it to the president.

At the same time, a new National Transportation Safety Board took over the Civil Aeronautics Board's (CAB) role of investigating and determining the causes of transportation accidents and making recommendations to the secretary of transportation. CAB was merged into DOT with its responsibilities limited to the regulation of commercial airline routes and fares.

The FAA gradually assumed additional functions. The hijacking epidemic of the 1960s had already brought the agency into the field of civil aviation security. In response to the hijackings on September 11, 2001, this responsibility is now primarily taken by the Department of Homeland Security. The FAA became more involved with the environmental aspects of aviation in 1968 when it received the power to set aircraft noise standards. Legislation in 1970 gave the agency management of a new airport aid program and certain added responsibilities for airport safety. During the 1960s and 1970s, the FAA also started to regulate high altitude (over 500 feet) kite and balloon flying.

1970s and deregulation

[edit]By the mid-1970s, the agency had achieved a semi-automated air traffic control system using both radar and computer technology. This system required enhancement to keep pace with air traffic growth, however, especially after the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 phased out the CAB's economic regulation of the airlines. A nationwide strike by the air traffic controllers union in 1981 forced temporary flight restrictions but failed to shut down the airspace system. During the following year, the agency unveiled a new plan for further automating its air traffic control facilities, but progress proved disappointing. In 1994, the FAA shifted to a more step-by-step approach that has provided controllers with advanced equipment.[11]

In 1979, Congress authorized the FAA to work with major commercial airports to define noise pollution contours and investigate the feasibility of noise mitigation by residential retrofit programs. Throughout the 1980s, these charters were implemented.

In the 1990s, satellite technology received increased emphasis in the FAA's development programs as a means to improvements in communications, navigation, and airspace management. In 1995, the agency assumed responsibility for safety oversight of commercial space transportation, a function begun eleven years before by an office within DOT headquarters. The agency was responsible for the decision to ground flights after the September 11 attacks.

21st century

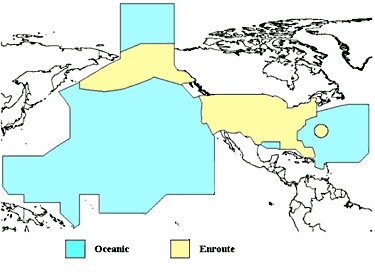

[edit]In December 2000, an organization within the FAA called the Air Traffic Organization,[12] (ATO) was set up by presidential executive order. This became the air navigation service provider for the airspace of the United States and for the New York (Atlantic) and Oakland (Pacific) oceanic areas. It is a full member of the Civil Air Navigation Services Organisation.

The FAA issues a number of awards to holders of its certificates. Among these are demonstrated proficiencies as an aviation mechanic (the AMT Awards), a flight instructor (Gold Seal certification), a 50-year aviator (Wright Brothers Master Pilot Award), a 50-year mechanic (Charles Taylor Master Mechanic Award) or as a proficient pilot. The latter, the FAA "WINGS Program", provides a lifetime series of grouped proficiency activities at three levels (Basic, Advanced, and Master) for pilots who have undergone several hours of ground and flight training since their last WINGS award, or "Phase". The FAA encourages volunteerism in the promotion of aviation safety. The FAA Safety Team, or FAASTeam, works with Volunteers at several levels and promotes safety education and outreach nationwide.

On March 18, 2008, the FAA ordered its inspectors to reconfirm that airlines are complying with federal rules after revelations that Southwest Airlines flew dozens of aircraft without certain mandatory inspections.[13] The FAA exercises surprise Red Team drills on national airports annually.

On October 31, 2013, after outcry from media outlets, including heavy criticism [14] from Nick Bilton of The New York Times,[15][16] the FAA announced it will allow airlines to expand the passengers use of portable electronic devices during all phases of flight, but mobile phone calls would still be prohibited (and use of cellular networks during any point when aircraft doors are closed remains prohibited to-date). Implementation initially varied among airlines. The FAA expected many carriers to show that their planes allow passengers to safely use their devices in airplane mode, gate-to-gate, by the end of 2013. Devices must be held or put in the seat-back pocket during the actual takeoff and landing. Mobile phones must be in airplane mode or with mobile service disabled, with no signal bars displayed, and cannot be used for voice communications due to Federal Communications Commission regulations that prohibit any airborne calls using mobile phones. From a technological standpoint, cellular service would not work in-flight because of the rapid speed of the airborne aircraft: mobile phones cannot switch fast enough between cellular towers at an aircraft's high speed. However, the ban is due to potential radio interference with aircraft avionics. If an air carrier provides Wi-Fi service during flight, passengers may use it. Short-range Bluetooth accessories, like wireless keyboards, can also be used.[17]

In July 2014, in the wake of the downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, the FAA suspended flights by U.S. airlines to Ben Gurion Airport during the 2014 Israel–Gaza conflict for 24 hours. The ban was extended for a further 24 hours but was lifted about six hours later.[18]

The FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018 gives the FAA one year to establish minimum pitch, width and length for airplane seats, to ensure they are safe for passengers.[19][20][21]

As of 2018, the FAA plans to replace the "FAA Telecommunications Infrastructure" (FTI) program with the "FAA Enterprise Network Services" (FENS) program.[22][23]

The first FAA licensed orbital human space flight took place on November 15, 2020, carried out by SpaceX on behalf of NASA.[24][25]

History of FAA Administrators

[edit]The administrator is appointed for a five-year term.[26]

| No. | Portrait | Administrator | Term start date | End date | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 |

|

Elwood Richard Quesada | November 1, 1958 | January 20, 1961 | |

2 |

|

Najeeb Halaby | March 3, 1961 | July 1, 1965 | |

3 |

|

William F. McKee | July 1, 1965 | July 31, 1968 | [27] |

4 |

|

John H. Shaffer | March 24, 1969 | March 14, 1973 | [27] |

5 |

|

Alexander Butterfield | March 14, 1973 | March 31, 1975 | |

6 |

|

John L. McLucas | November 24, 1975 | April 1, 1977 | |

7 |

|

Langhorne Bond | May 4, 1977 | January 20, 1981 | |

8 |

|

J. Lynn Helms | April 22, 1981 | January 31, 1984 | |

9 |

|

Donald D. Engen | April 10, 1984 | July 2, 1987 | |

10 |

|

T. Allan McArtor | July 22, 1987 | February 17, 1989 | |

11 |

|

James B. Busey IV | June 30, 1989 | December 4, 1991 | |

12 |

|

Thomas C. Richards | June 27, 1992 | January 20, 1993 | |

13 |

|

David R. Hinson | August 10, 1993 | November 9, 1996 | |

14 |

|

Jane Garvey | August 4, 1997 | August 2, 2002 | |

15 |

|

Marion Blakey | September 12, 2002 | September 13, 2007 | |

acting |

|

Robert A. Sturgell | September 14, 2007 | January 15, 2009 | |

acting |

|

Lynne Osmus | January 16, 2009 | May 31, 2009 | [28] |

16 |

|

Randy Babbitt | June 1, 2009 | December 6, 2011 | [29][30] |

| acting |  |

Michael Huerta | December 7, 2011 | January 10, 2013 | |

17

|

January 10, 2013 | January 6, 2018 | [31][32] | ||

acting |

|

Daniel K. Elwell | January 6, 2018 | August 12, 2019 | [33][34][35] |

18 |

|

Stephen Dickson | August 12, 2019 | March 31, 2022 | [36][37] |

acting |

|

Billy Nolen | April 1, 2022 | June 9, 2023 | [38][39] |

acting |

|

Polly Trottenberg | June 9, 2023 | October 27, 2023 | [40] |

19 |

|

Michael Whitaker | October 27, 2023 | January 20, 2025 | [41][42] |

acting |

|

Chris Rocheleau | January 30, 2025 | July 10, 2025 | [43] |

20 |

|

Bryan Bedford | July 10, 2025 | Present | [44] |

On March 19, 2019, President Donald Trump announced he would nominate Stephen Dickson, a former executive and pilot at Delta Air Lines, to be the next FAA Administrator.[45][34][35] On July 24, 2019, the Senate confirmed Dickson by a vote of 52–40.[46][47] He was sworn in as Administrator by Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao on August 12, 2019.[47] On February 16, 2022, Dickson announced his resignation as FAA Administrator, effective March 31, 2022.[48] In September 2023, President Joe Biden announced that he would be nominating Mike Whitaker to lead the FAA. Whitaker previously served as deputy administrator of the FAA under President Barack Obama.[49]

Criticism

[edit]Conflicting roles

[edit]The FAA has been cited as an example of regulatory capture, "in which the airline industry openly dictates to its regulators its governing rules, arranging for not only beneficial regulation, but placing key people to head these regulators."[50] Retired NASA Office of Inspector General Senior Special Agent Joseph Gutheinz, who used to be a Special Agent with the Office of Inspector General for the Department of Transportation and with FAA Security, is one of the most outspoken critics of FAA. Rather than commend the agency for proposing a $10.2 million fine against Southwest Airlines for its failure to conduct mandatory inspections in 2008, he was quoted as saying the following in an Associated Press story: "Penalties against airlines that violate FAA directives should be stiffer. At $25,000 per violation, Gutheinz said, airlines can justify rolling the dice and taking the chance on getting caught. He also said the FAA is often too quick to bend to pressure from airlines and pilots."[51] Other experts have been critical of the constraints and expectations under which the FAA is expected to operate. The dual role of encouraging aerospace travel and regulating aerospace travel are contradictory. For example, to levy a heavy penalty upon an airline for violating an FAA regulation which would impact their ability to continue operating would not be considered encouraging aerospace travel.

On July 22, 2008, in the aftermath of the Southwest Airlines inspection scandal, a bill was unanimously approved in the House to tighten regulations concerning airplane maintenance procedures, including the establishment of a whistleblower office and a two-year "cooling off" period that FAA inspectors or supervisors of inspectors must wait before they can work for those they regulated.[52][53] The bill also required rotation of principal maintenance inspectors and stipulated that the word "customer" properly applies to the flying public, not those entities regulated by the FAA.[52] The bill died in a Senate committee that year.[54]

In September 2009, the FAA administrator issued a directive mandating that the agency use the term "customers" to refer to only the flying public.[55]

Lax regulatory oversight

[edit]In 2007, two FAA whistleblowers, inspectors Charalambe "Bobby" Boutris and Douglas E. Peters, alleged that Boutris said he attempted to ground Southwest after finding cracks in the fuselage of an aircraft, but was prevented by supervisors he said were friendly with the airline.[56] This was validated by a report by the Department of Transportation which found FAA managers had allowed Southwest Airlines to fly 46 airplanes in 2006 and 2007 that were overdue for safety inspections, ignoring concerns raised by inspectors. Audits of other airlines resulted in two airlines grounding hundreds of planes, causing thousands of flight cancellations.[52] The House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee held hearings in April 2008. Jim Oberstar, former chairman of the committee, said its investigation uncovered a pattern of regulatory abuse and widespread regulatory lapses, allowing 117 aircraft to be operated commercially although not in compliance with FAA safety rules.[56] Oberstar said there was a "culture of coziness" between senior FAA officials and the airlines and "a systematic breakdown" in the FAA's culture that resulted in "malfeasance, bordering on corruption".[56] In 2008 the FAA proposed to fine Southwest $10.2 million for failing to inspect older planes for cracks,[51] and in 2009 Southwest and the FAA agreed that Southwest would pay a $7.5 million penalty and would adopt new safety procedures, with the fine doubling if Southwest failed to follow through.[57]

Changes to air traffic controller application process

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2025) |

In 2014, the FAA modified its approach to air traffic control hiring. It launched more "off the street bids", allowing anyone with either a four-year degree or five years of full-time work experience to apply, rather than the closed college program or Veterans Recruitment Appointment bids, something that had last been done in 2008. Thousands were hired, including veterans, Collegiate Training Initiative graduates, and people who are true "off the street" hires. The move was made to open the job up to more people who might make good controllers but did not go to a college that offered a CTI program. Before the change, candidates who had completed coursework at participating colleges and universities could be "fast-tracked" for consideration. However, the CTI program had no guarantee of a job offer, nor was the goal of the program to teach people to work actual traffic. The goal of the program was to prepare people for the FAA Academy in Oklahoma City, OK. Having a CTI certificate allowed a prospective controller to skip the Air Traffic Basics part of the academy, about a 30- to 45-day course, and go right into Initial Qualification Training (IQT). All prospective controllers, CTI or not, have had to pass the FAA Academy in order to be hired as a controller. Failure at the academy means FAA employment is terminated. In January 2015 they launched another pipeline, a "prior experience" bid, where anyone with an FAA Control Tower Operator certificate (CTO) and 52 weeks of experience could apply. This was a revolving bid, every month the applicants on this bid were sorted out, and eligible applicants were hired and sent directly to facilities, bypassing the FAA academy entirely.

In the process of promoting diversity, the FAA revised its hiring process.[58][59] The FAA later issued a report that the "bio-data" was not a reliable test for future performance. However, the "Bio-Q" was not the determining factor for hiring, it was merely a screening tool to determine who would take a revised Air Traffic Standardized Aptitude Test (ATSAT). Due to cost and time, it was not practical to give all 30,000 some applicants the revised ATSAT, which has since been validated. In 2015 Fox News levied criticism that the FAA discriminated against qualified candidates.[60]

In December 2015, a reverse discrimination lawsuit was filed against the FAA seeking class-action status for the thousands of men and women who spent up to $40,000 getting trained under FAA rules before they were abruptly changed. The prospects of the lawsuit are unknown, as the FAA is a self-governing entity and therefore can alter and experiment with its hiring practices, and there was never any guarantee of a job in the CTI program.[61]

Close Calls

[edit]In August 2023 The New York Times published an investigative report that showed overworked air traffic controllers at understaffed facilities making errors that resulted in 46 near collisions in the air and on the ground in the month of July alone.[62]

Next Generation Air Transportation System

[edit]A May 2017 letter from staff of the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure to members of the same committee sent before a meeting to discuss air traffic control privatization noted a 35-year legacy of failed air traffic control modernization management, including NextGen. The letter said the FAA initially described NextGen as fundamentally transforming how air traffic would be managed. In 2015, however, the National Research Council noted that NextGen, as currently executed, was not broadly transformational and that it is a set of programs to implement a suite of incremental changes to the National Airspace System (NAS).[63][64]

More precise Performance Based Navigation can reduce fuel burn, emissions, and noise exposure for a majority of communities, but the concentration of flight tracks also can increase noise exposure for people who live directly under those flight paths.[65][66] A feature of the NextGen program is GPS-based waypoints, which result in consolidated flight paths for planes. The result of this change is that many localities experience huge increases in air traffic over previously quiet areas. Complaints have risen with the added traffic and multiple municipalities have filed suit.[67]

Staffing cuts

[edit]In 2025, despite the ongoing overhaul of the U.S. ATC system—spanning past administrations and on into the Trump presidency—DOGE elimination of numerous FAA management positions has not only demoralized staff, but by eliminating deep expertise at a very critical juncture also threatens to degrade the ability of the agency to expedite modernization efforts.[68] In the resulting leadership vacuum, “ …the FAA is losing not only its chief air traffic official, Tim Arel, but also its associate administrator for commercial space, his deputy, the director of the audit and evaluation office, the assistant administrator for civil rights and the assistant administrator for finance and management …” in addition to: multiple leadership positions in programs within the Air Traffic Organization, including mission support and safety, technical operations, and technical training.[68]

Boeing 737 MAX controversy

[edit]As a result of the March 10, 2019 Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 crash and the Lion Air Flight 610 crash five months earlier, most airlines and countries began grounding the Boeing 737 MAX 8 (and in many cases all MAX variants) due to safety concerns, but the FAA declined to ground MAX 8 aircraft operating in the U.S.[69] On March 12, the FAA said that its ongoing review showed "no systemic performance issues and provides no basis to order grounding the aircraft."[70] Some U.S. Senators called for the FAA to ground the aircraft until an investigation into the cause of the Ethiopian Airlines crash was complete.[70] U.S. Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao said that "If the FAA identifies an issue that affects safety, the department will take immediate and appropriate action."[71] The FAA resisted grounding the aircraft until March 13, 2019, when it received evidence of similarities in the two accidents. By then, 51 other regulators had already grounded the plane,[72] and by March 18, 2019, all 387 aircraft in service were grounded. Three major U.S. airlines—Southwest, United, and American Airlines—were affected by this decision.[73]

Further investigations also revealed that the FAA and Boeing had colluded on recertification test flights, attempted to cover up important information and that the FAA had retaliated against whistleblowers.[74]

Regulatory process

[edit]Designated Engineering Representative

[edit]A Designated Engineering Representative (DER) is an engineer who is appointed under 14 CFR section 183.29 to act on behalf of a company or as an independent consultant (IC).[75] The DER system enables the FAA to delegate certain involvement in airworthiness exams, tests, and inspections to qualified technical people outside of the FAA.[76] Qualifications and policies for appointment of Designated Airworthiness Representatives are established in FAA Order 8100.8, Designee Management Handbook. Working procedures for DERs are prescribed in FAA Order 8110.37, Designated Engineering Representative (DER) Handbook.

- Company DERs act on behalf of their employer and may only approve, or recommend that the FAA approves, technical data produced by their employer.

- Consultant DERs are appointed to act as independent DERs and may approve, or recommend that the FAA approves, technical data produced by any person or organization.

Neither type of DER is an employee of either the FAA or the United States government. While a DER represents the FAA when acting under the authority of a DER appointment; a DER has no federal protection for work done or the decisions made as a DER. Neither does the FAA provide any indemnification for a DER from general tort law. "The FAA cannot shelter or protect DERs from the consequences of their findings."[77]

Designated Airworthiness Representative (DAR)

[edit]A DAR[78] is an individual appointed in accordance with 14 CFR 183.33 who may perform examination, inspection, and testing services necessary to the issuance of certificates. There are two types of DARs: manufacturing, and maintenance.

- Manufacturing DARs must possess aeronautical knowledge, experience, and meet the qualification requirements of FAA Order 8100.8.

- Maintenance DARs must hold:

- a mechanic's certificate with an airframe and powerplant rating, under 14 CFR part 65 Certification: Airmen Other Than Flight Crewmembers, or

- a repairman certificate and be employed at a repair station certificated under 14 CFR part 145, or an air carrier operating certificate holder with an FAA-approved continuous airworthiness program, and must meet the qualification requirements of Order 8100.8, Chapter 14.

Specialized Experience – Amateur-Built and Light-Sport Aircraft DARs Both Manufacturing DARs and Maintenance DARs may be authorized to perform airworthiness certification of light-sport aircraft. DAR qualification criteria and selection procedures for amateur-built and light-sport aircraft airworthiness functions are provided in Order 8100.8.

Continued Airworthiness Notification to the International Community (CANIC)

[edit]A Continued Airworthiness Notification to the International Community (commonly abbreviated as CANIC) is a notification from the FAA to civil airworthiness authorities of foreign countries of pending significant safety actions.[79]

The FAA Airworthiness Directives Manual,[80] states the following:

8. Continued Airworthiness Notification to the International Community (CANIC).

- a. A CANIC is used to notify civil airworthiness authorities of other countries of pending significant safety actions. A significant safety action can be defined as, but not limited to, the following:

- (1) Urgent safety situations;

- (2) The pending issuance of an Emergency AD;

- (3) A safety action that affects many people, operators;

- (4) A Special Federal Aviation Regulation (SFAR);

- (5) Other high interest event (e.g., a special certification review).

Notable CANICs

[edit]The FAA issued a CANIC to state the continued airworthiness of the Boeing 737 MAX, following the crash of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302.[81][82][83][84]

Another CANIC notified the ungrounding of the MAX, ending a 20-month grounding.[85]

Proposed regulatory reforms

[edit]FAA reauthorization and air traffic control reform

[edit]U.S. law requires that the FAA's budget and mandate be reauthorized on a regular basis. On July 18, 2016, President Obama signed a second short-term extension of the FAA authorization, replacing a previous extension that was due to expire that day.[86]

The 2016 extension (set to expire itself in September 2017) left out a provision pushed by Republican House leadership, including House Transportation and Infrastructure (T&I) Committee Chairman Bill Shuster (R-PA). The provision would have moved authority over air traffic control from the FAA to a non-profit corporation, as many other nations, such as Canada, Germany and the United Kingdom, have done.[87] Shuster's bill, the Aviation Innovation, Reform, and Reauthorization (AIRR) Act,[88] expired in the House at the end of the 114th Congress.[89]

The House T&I Committee began the new reauthorization process for the FAA in February 2017. It is expected that the committee will again urge Congress to consider and adopt air traffic control reform as part of the reauthorization package. Shuster has additional support from President Trump, who, in a meeting with aviation industry executives in early 2017 said the U.S. air control system is "totally out of whack."[90]

See also

[edit]- Acquisition Management System

- Airport Improvement Program

- Aviation Safety Knowledge Management Environment

- Federal Aviation Regulations

- Civil aviation authority (generic term)

- Office of Dispute Resolution for Acquisition

- SAFO, Safety Alert for Operators

- United States government role in civil aviation

- Weather Information Exchange Model

References

[edit]- ^ Wald, Matthew L. (22 August 2007). "F.A.A. Chief to Lead Industry Group". The New York Times. eISSN 1553-8095. ISSN 0362-4331. OCLC 1645522. Archived from the original on 28 July 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

- ^ Birnbaum, Jeffrey H. (August 22, 2007). "FAA Chief To Become Aerospace Lobbyist". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- ^ Van Loo, Rory (August 1, 2018). "Regulatory Monitors: Policing Firms in the Compliance Era". Faculty Scholarship. 119 (2): 369. Archived from the original on June 4, 2020. Retrieved October 10, 2020.

- ^ Key Officials Archived June 28, 2021, at the Wayback Machine FAA. Retrieved on June 20, 2021.

- ^ Air Traffic Organization Archived May 7, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. FAA.gov (December 5, 2017). Retrieved on March 14, 2019.

- ^ Aviation Safety (AVS) Archived May 8, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. FAA.gov (November 29, 2018). Retrieved on March 14, 2019.

- ^ Airports Archived May 12, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. FAA. Retrieved on June 20, 2021.

- ^ Office of Commercial Space Transportation Archived May 19, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. FAA.gov (June 5, 2018). Retrieved on March 14, 2019.

- ^ "Security and Hazardous Materials Safety". FAA. Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- ^ "Regional Offices & Aeronautical Center". FAA. April 6, 2011. Archived from the original on November 17, 2018. Retrieved March 24, 2012.

- ^ FAA History Archived July 2, 2008, at the Wayback Machine from official website.

- ^ Air Traffic Organization Archived April 19, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Official website.

- ^ FAA looking to see if airlines made safety repairs Archived March 21, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Dwight Silverman (October 7, 2013). "If the FAA changes its electronics rules, you can thank a reporter". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved November 16, 2014.

- ^ Clampet, Jason (October 31, 2013). "The Internet Is Thanking Nick Bilton for the FAA's New Rules". Skift. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015.

- ^ Bilton, Nick (October 9, 2013). "Disruptions: How the F.A.A., Finally, Caught Up to an Always-On Society". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 30, 2019. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- ^ "At last! FAA green lights gadgets on planes". Fox News. Archived from the original on November 1, 2013. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ^ "British Airways CEO insists flights over Iraq are safe". The UK News. Archived from the original on August 8, 2014. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- ^ Josephs, Leslie (September 27, 2018). "House passes bill to require minimum standards for airplane seat size, legroom". CNBC. Archived from the original on September 28, 2018. Retrieved September 28, 2018.

- ^ "FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018" (PDF). October 5, 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 3, 2019. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- ^ Davis, Jeff (September 24, 2018). "Summary of Final Compromise FAA Reauthorization Act of 2018". Eno Center for Transportation. Archived from the original on July 28, 2019. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

Section 577 of the bill requires the FAA to issue rules establishing minimum width, length and seat pitch of airline seats.

- ^ Daniel Elwell. "FTI Mission Support Network Status and Future Plans: Report to Congress". 2018. p. 6 and p. A-1.

- ^ "FAA Enterprise Network Services Program".

- ^ "Crew-1 is headed to Space Station, launching the NASA/SpaceX venture". CNBC. November 10, 2020. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved November 10, 2020.

- ^ "NASA certifies SpaceX's Crew Dragon for astronaut flights, gives 'go' for Nov. 14 launch". Space.com. November 11, 2020. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ^ Rose, Joel (December 12, 2024). "FAA chief Mike Whitaker announces that he will step down in January". NPR. Retrieved January 10, 2025.

- ^ a b "William F. McKee". Air Progress: 76. August 1989.

- ^ Lichman, Barbara E. (January 6, 2009). "New Acting Administrator for the FAA: Lynne A. Osmus". Aviation & Airport.

- ^ "Randy Babbitt". IBM Center for The Business of Government.

- ^ "Babbitt leaves U.S. Aviation agency amid safety, fund debate". Daily Herald (Arlington Heights, Illinois). December 6, 2011.

- ^ Stegon, David (January 10, 2013). "Huerta sworn in as FAA administrator". FedScoop.

- ^ Davis, Jeff (December 13, 2024). "FAA Administrator to Resign on January 20". Eno Center for Transportation.

- ^ Farrell, Paul (March 13, 2019). "Dan Elwell: 5 Fast Facts You Need To Know". Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ^ a b Hsu, Tiffany; Kaplan, Thomas; Wichter, Zach (March 19, 2019). "Trump Picks Former Delta Executive Stephen Dickson as F.A.A. Chief". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 20, 2019. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- ^ a b Pasztor, Andy; Tangel, Andrew (March 19, 2019). "White House to Nominate Steve Dickson as Permanent FAA Head". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on March 19, 2019. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- ^ "Stephen M. Dickson Sworn in as Administrator of the Federal Aviation Administration". FAA. August 12, 2019.

- ^ Muntean, Pete (February 16, 2022). "FAA Administrator Steve Dickson is resigning". CNN.

- ^ "Billy Nolen, FRAeS–FAA Administrator (Acting)". Federal Aviation Administration. Archived from the original on April 18, 2022. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ Duncan, Ian (March 26, 2022). "Top FAA safety official named as interim leader of agency". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on March 27, 2022. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ "Polly Trottenberg". Federal Aviation Administration. Retrieved January 18, 2024.

- ^ Duncan, Ian (October 24, 2023). "Senate confirms new FAA administrator, filling a role vacant for 18 months". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 24, 2023.

- ^ Dougherty, Hugh (January 29, 2025). "FAA Administrator Quit on Jan. 20 After Elon Musk Told Him to Resign". Yahoo News.

- ^ "Donald Trump names new acting FAA administrator in wake of "tragedy of terrible proportions"". Politico. January 30, 2025. Retrieved January 30, 2025.

- ^ Cisneros, Raul (July 25, 2025). "FAA Administrator Bryan Bedford visits AirVenture". Experimental Aircraft Association.

- ^ Naylor, Brian (March 19, 2019). "Trump To Nominate Former Delta Airlines Executive To Lead FAA". NPR. Archived from the original on March 20, 2019. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- ^ "U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes 116th Congress - 1st Session". U.S. Senate. Archived from the original on August 4, 2019. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

- ^ a b "Stephen M. Dickson Sworn in as Administrator of the Federal Aviation Administration" (Press release). Federal Aviation Administration. August 12, 2019. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ Duncan, Ian (February 16, 2022). "FAA administrator Steve Dickson to resign next month". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on February 20, 2022. Retrieved February 17, 2022.

- ^ Tangel, Andrew (September 7, 2023). "Mike Whitaker Is President Biden's Pick to Lead FAA". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ^ Solomon, Steven Davidoff (June 11, 2010). "The Government's Elite and Regulatory Capture". DealBook. The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 20, 2020. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- ^ a b Koenig, David (March 6, 2008). "Southwest Airlines faces $10.2 million fine". Mail Tribune. Associated Press. Archived from the original on September 25, 2012. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ a b c Lowe, Paul (September 1, 2008). "Bill proposes distance between airlines and FAA regulators". AINonline. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ Congress.gov, "H.R.6493 - Aviation Safety Enhancement Act of 2008". Archived October 1, 2021, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Congress.gov, "S.3440 - Aviation Safety Enhancement Act of 2008". Archived October 1, 2021, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "FAA will stop calling airlines 'customers'". USA Today. Reuters. September 18, 2009. Archived from the original on December 24, 2010. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- ^ a b c Johanna Neuman, "FAA's 'culture of coziness' targeted in airline safety hearing", Los Angeles Times (April 3, 2008). Archived January 23, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ John Hughes for Bloomberg News. March 2, 2009. Southwest Air Agrees to $7.5 Million Fine, FAA Says (Update2) Archived September 24, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Shapiro, Adam; Browne, Pamela (May 20, 2015). "Trouble in the Skies". Fox Business. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved January 3, 2016.

- ^ Reily, Jason L. (June 2, 2015). "Affirmative Action Lands in the Air Traffic Control Tower". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 2, 2016. Retrieved January 3, 2016.

- ^ "Unqualified air traffic control candidates cheating to pass FAA exams?". Fox Business. May 20, 2015. Archived from the original on January 23, 2016. Retrieved January 3, 2016.

- ^ Shapiro, Adam (December 30, 2015). "Reverse Discrimination Suit Filed Against FAA, Hiring Fallout Continues". Fox Business. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016. Retrieved January 3, 2016.

- ^ Ember, Sydney; Steel, Emily; Abraham, Leanne; Lutz, Eleanor; Koeze, Ella (August 21, 2023). "Airline Close Calls Happen Far More Often Than Previously Known". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 22, 2023.

- ^ "Committee Hearing on "The Need to Reform FAA and Air Traffic Control to Build a 21st Century Aviation System for America"" (PDF). Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure. May 12, 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 20, 2018. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- ^ "Latest Inspector General Report Underscores Need for Air Traffic Control Reform". Archived from the original on December 23, 2018. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- ^ "FAA facing backlash over noise issues created by PBN flight paths". Archived from the original on October 21, 2016.

- ^ "A Closer Look at How FAA is 'Tone-Deaf' on NextGen Noise Impacts". Aviation Impact Reform. April 19, 2015. Archived from the original on December 18, 2019. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- ^ McLaughlin, Katy (July 6, 2018). "Affluent—and Angry—Homeowners Raise Ruckus Over Roar of Overhead Planes". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on December 18, 2019. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- ^ a b Duncan, Ian; Aratani, Lori; Natanson, Hannah; Gilbert, Daniel (May 8, 2025). "Trump accelerates upgrades of air traffic control systems amid FAA departures". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved May 15, 2025.

- ^ "US and Canada are the only two nations still flying many Boeing 737 MAX planes". CNN. March 12, 2019. Archived from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- ^ a b "U.S. Senate to hold crash hearing as lawmakers urge grounding Boeing 737 MAX 8". Reuters. March 12, 2019. Archived from the original on July 10, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- ^ "U.S. to mandate design changes on Boeing 737 MAX 8 after crashes". Euronews. March 12, 2019. Archived from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- ^ "Editorial: Why was the FAA so late to deplane from Boeing's 737 Max?". Los Angeles Times. March 14, 2019. Archived from the original on July 20, 2021. Retrieved July 20, 2021.

- ^ Austen, Ian; Gebrekidan, Selam (March 13, 2019). "Trump Announces Ban of Boeing 737 Max Flights". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 13, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2019.

- ^ "FAA and Boeing manipulated 737 Max tests during recertification". December 18, 2020. Archived from the original on July 10, 2022. Retrieved August 25, 2022.

- ^ "faa.gov: "Engineering and Flight Test Designees - Designated Engineering Representative (DER)"". Archived from the original on June 8, 2009. Retrieved May 31, 2009.

- ^ "FAA Order 8110.37F" (PDF). p. 2-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 29, 2019.

- ^ "FAA Order 8100.8D" (PDF). p. 3-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 18, 2022. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ^ "Designated Airworthiness Representative (DAR)". Archived from the original on December 17, 2013. Retrieved December 17, 2013.

- ^ "Lessons Learned". lessonslearned.faa.gov. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ Airworthiness Directives Manual (PDF). FAA. May 17, 2010. pp. Chapter 6, section 8. Continued Airworthiness Notification to the International Community (CANIC). FAA-IR-M-8040.1C. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ Continued Airworthiness Notification to the International Community (PDF). FAA. March 11, 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 3, 2019. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ LeBeau, Phil (March 20, 2019). "FAA says reviewing 737 Max software fix is 'an agency priority'". CNBC. Archived from the original on October 20, 2019. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ "FAA Says Boeing 737 MAX 8 Is 'Airworthy' Despite Second Crash". Time. Archived from the original on May 21, 2019. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ Rodrigo, Chris Mills (March 11, 2019). "Former FAA safety inspector urges caution over Boeing 737: 'I've never, ever done this'". The Hill. Archived from the original on October 20, 2019. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

- ^ "CANIC" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration. November 18, 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 24, 2020.

- ^ "FAA reauthorization signed into law: Travel Weekly". www.travelweekly.com. Archived from the original on March 9, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ Carey, Susan; Pasztor, Andy (July 13, 2016). "Senate Passes FAA Reauthorization Bill". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ "H.R.4441 - 114th Congress (2015-2016): Aviation Innovation, Reform, and Reauthorization Act of 2016". Congress.gov. February 11, 2016. Archived from the original on February 15, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ "Congress, Trump Administration Must Prioritize Air Traffic Control Reform". Competitive Enterprise Institute. December 12, 2016. Archived from the original on March 9, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ "Congressional Hearings on FAA Reauthorization and Automated Vehicles; FTA Withholds Funding from DC, MD, VA for Missing WMATA Safety Oversight Deadline". The National Law Review. Archived from the original on March 9, 2017. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Records of the Federal Aviation Administration in the National Archives (Record Group 237) Archived January 16, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- Federal Aviation Administration in the Federal Register

- Works by or about Federal Aviation Administration at the Internet Archive

- Works by Federal Aviation Administration at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- FAA HIMS Program Overview – An independent educational resource explaining the FAA’s Human Intervention Motivation Study (HIMS) Program structure and certification process.

Federal Aviation Administration

View on GrokipediaCore Functions and Responsibilities

Air Traffic Management and Operations

The Federal Aviation Administration's Air Traffic Organization oversees the safe and efficient management of the National Airspace System (NAS), which encompasses approximately 24 million square miles of airspace over the continental United States, Alaska, and oceanic regions extending to international boundaries. This includes directing over 44,000 average daily flights through a network of facilities that provide en route, terminal, and airport-level control services.[11] Controllers maintain aircraft separation using established minimum distances, typically 3 nautical miles laterally or 1,000 feet vertically in en route airspace, adjusted for procedural and radar environments to prevent collisions and ensure orderly flow.[12] En route traffic is managed by 21 Air Route Traffic Control Centers (ARTCCs), which handle high-altitude and oceanic flights using long-range surveillance. Terminal operations occur at 149 Terminal Radar Approach Control (TRACON) facilities, managing arrivals and departures within 30-50 miles of airports, while over 500 airport towers direct ground movements and low-altitude takeoffs and landings. Surveillance relies on a combination of primary and secondary radar for target acquisition, supplemented by Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B), which provides GPS-derived position data broadcast from aircraft to ground stations, offering higher update rates (every second) and coverage in radar gaps compared to radar's 4-12 second intervals.[13] Communication protocols include VHF radio for voice instructions and Controller-Pilot Data Link Communications (CPDLC) for text-based clearances, with phraseology standardized to minimize ambiguity, such as "cleared to" for routings or "maintain" for altitudes.[14] The NAS integrates with military operations through coordination at the Air Traffic Control System Command Center (ATCSCC), which deconflicts Department of Defense activities like training routes, and adheres to International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) standards for transoceanic and border-crossing traffic. In emergencies, protocols include issuing Notices to Air Missions (NOTAMs) for hazards or restrictions and implementing ground stops to halt departures at specific airports or nationwide when capacity is overwhelmed or threats arise; for instance, following the September 11, 2001, attacks, the FAA issued a NOTAM grounding all civilian flights within U.S. airspace, resulting in over 4,500 aircraft diverted or grounded by September 14.[15] Traffic Management Initiatives (TMIs), such as miles-in-trail spacing or rerouting, dynamically balance demand and capacity during disruptions like severe weather.[16]Safety Regulation and Enforcement

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) mandates and enforces safety standards for civil aviation operations under authority granted by the Federal Aviation Act, primarily through the Federal Aviation Regulations (FARs) codified in Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations, which specify requirements for flight operations, aircraft maintenance practices, and equipment performance to minimize hazards.[17] [18] These regulations evolve via notice-and-comment rulemaking informed by empirical safety data, ensuring standards reflect causal factors in aviation incidents rather than unsubstantiated assumptions.[19] Compliance monitoring occurs through systematic inspection programs administered by FAA aviation safety inspectors, who conduct ramp checks, records reviews, and audits of air carriers, repair stations, and operators to detect deviations that could compromise flight safety.[20] Enforcement escalates for non-compliance posing risks, including civil penalties up to $99,756 per violation for hazardous materials infractions or higher for severe cases, alongside certificate suspensions or revocations when holders demonstrate unfitness, as detailed in FAA Order 2150.3C.[21] [22] The agency compiles and publishes quarterly enforcement reports to document actions against regulated entities, promoting transparency in sanction application.[23] Risk prioritization drives enforcement via the FAA's Safety Management System (SMS), which employs data analytics from sources like the Aviation Safety Information Analysis and Sharing (ASIAS) to quantify hazard probabilities and severities, enabling targeted interventions over uniform oversight.[24] [25] Safety Risk Management within SMS systematically identifies threats—such as pilot fatigue or maintenance lapses—assesses their potential impacts, and mandates controls like procedural mitigations when risks exceed acceptable thresholds.[26] The FAA coordinates with the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) on accident probes through its Office of Accident Investigation and Prevention, supplying regulatory expertise to analyze causal chains and derive preventive measures, such as rulemaking for procedural reforms, without usurping NTSB's independence in fault attribution.[27] [28] Post-investigation adjustments, informed by empirical reconstructions, have historically addressed systemic vulnerabilities, exemplified by regulatory updates following incident patterns in areas like runway incursions.[27]Certification of Aircraft, Personnel, and Airports

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) conducts type certification to approve the design of new aircraft, engines, propellers, and appliances, ensuring compliance with airworthiness standards under 14 CFR Part 21, Subpart B.[29] This process involves submitting data, test results, and engineering analyses to demonstrate safety, with the FAA issuing a type certificate upon verification that the design meets minimum standards for structural integrity, performance, and systems reliability as mandated by 49 U.S.C. § 44704.[30] For modifications to existing certified designs, the FAA issues supplemental type certificates, which typically require 3-5 years to complete, compared to 5-9 years for entirely new type certificates.[31] Airmen certification encompasses pilots, mechanics, and flight dispatchers, requiring passage of knowledge and practical tests, along with meeting medical fitness standards outlined in 14 CFR Part 61 for pilots and Part 65 for mechanics and dispatchers. Private pilot eligibility demands at least 17 years of age, English proficiency, a third-class medical certificate, 40 hours of flight time including specific cross-country and night training, and successful completion of written and checkride examinations.[32] Commercial pilot certification escalates requirements to 250 total flight hours, 23 years of age, and instrument rating proficiency, enabling compensated operations while prohibiting carriage of passengers or property for hire without further airline transport pilot credentials.[33] All certificate holders must undergo recurrent training and biennial flight reviews to maintain currency, with medical certificates renewed periodically based on class (first-class every 6-12 months for airline pilots, third-class every 60 months for private pilots).[34] Airport certification under 14 CFR Part 139 applies to facilities serving scheduled air carrier operations with more than 9 passenger seats or unscheduled operations with 31 or more seats, mandating an Airport Operating Certificate after FAA inspection of operations manuals, emergency plans, and infrastructure.[35] Certificated airports must maintain runway safety areas meeting dimensional standards (e.g., 1,000 feet long by 500 feet wide for Class I runways), conduct regular wildlife hazard assessments and management programs to mitigate bird strikes, and implement snow and ice control plans during winter operations.[36] Compliance involves unannounced FAA inspections, record-keeping for movements and incidents, and updates to certification plans every 24 months or after significant changes, ensuring infrastructure supports safe takeoffs, landings, and ground movements.[37]Promotion of Aviation Development and Standards

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) promotes aviation development by developing and harmonizing standards that enhance interoperability and efficiency, complementing its regulatory mandate to ensure safety. Through voluntary standards and international alignment, the agency facilitates innovation and reduces operational barriers for the industry, such as duplicative certification processes for aircraft and systems.[38] This dual approach supports economic growth in aviation while maintaining rigorous safety oversight, as evidenced by the FAA's emphasis on standards that industry can adopt to streamline global operations.[39] In collaboration with the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), the FAA advances global standards alignment to minimize redundant certifications and promote harmonized practices across borders. The agency's Office of International Affairs coordinates U.S. participation in ICAO's Standards and Recommended Practices (SARPs), ensuring compliance and influencing worldwide adoption of technologies like NextGen systems for improved airspace efficiency.[40] This effort reduces certification costs for manufacturers exporting to multiple markets, as seen in bilateral agreements that align FAA rules with foreign authorities, thereby accelerating aircraft type validations and market access.[41] For instance, harmonization initiatives in avionics and loads standards have streamlined regulatory approvals since the 1990s, fostering industry competitiveness without compromising safety benchmarks.[42][43] The FAA supports infrastructure development through the Airport Improvement Program (AIP), which provides federal grants to public agencies for enhancing airport capacity and safety features. In fiscal year 2025, AIP allocated over $3.18 billion in entitlement and discretionary funds for projects including runways, taxiways, signage, and lighting upgrades at public-use airports.[44] These grants also fund noise abatement measures, such as compatible land-use planning and mitigation technologies, to address community impacts while enabling airport expansions that accommodate growing air traffic.[45] A recent example includes $431.8 million awarded to 60 airports in 2024 for safety and environmental improvements, demonstrating tangible investments in infrastructure resilience.[46] FAA research initiatives drive adoption of emerging technologies, integrating unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) into the national airspace to expand commercial applications like delivery and inspection services. Through the UAS Integration Pilot Program launched in 2017, the agency partnered with over 100 stakeholders to test operations beyond visual line of sight, yielding data on detect-and-avoid systems that improve airspace efficiency by enabling scalable drone fleets without dedicated corridors.[47] Ongoing research includes flight tests and risk assessments, supporting standards for UAS traffic management that could reduce operational costs by up to 30% in urban areas through optimized routing.[48] In sustainable aviation fuels (SAF), the FAA funds studies to certify drop-in fuels from renewable sources, targeting lifecycle greenhouse gas reductions of up to 80% compared to conventional jet fuel. The Aviation Sustainability Center (ASCENT) program awarded $27.2 million in 2024 to universities for emissions research, including SAF supply chain development and engine compatibility testing.[49] These efforts, part of broader Continuous Lower Energy, Emissions, and Noise (CLEEN) phases, project efficiency gains such as 10% smaller noise contours by 2050 through integrated fuel and technology advancements, aiding the industry's path to net-zero emissions.[50][51]Organizational Structure

Leadership and Administrator Role

The Administrator of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is appointed by the President of the United States with the advice and consent of the Senate, serving a statutory term of five years while reporting directly to the Secretary of Transportation.[52] This structure insulates the role from short-term political pressures, though historical tenures have frequently been abbreviated by changes in administration or resignation.[53] The Administrator exercises broad authority over the agency's 46,000 employees, including directing rulemaking processes under Title 49 of the United States Code, allocating budgets for air traffic control modernization and safety programs, and declaring emergencies such as temporary flight restrictions or immediate regulatory actions to mitigate hazards.[54][55] Among the Administrator's emergency powers is the ability to promulgate rules effective immediately without public notice or comment periods when an imminent threat to aviation safety exists, as authorized by 49 U.S.C. § 46105(c) and § 106(f).[56] For example, in response to the January 11, 2023, outage of the Notice to Air Missions (NOTAM) system—triggered by a corrupted database file that halted all domestic departures for over 90 minutes—the acting Administrator oversaw system restoration, issued a nationwide ground stop, and established a safety review team to analyze root causes and recommend upgrades to prevent recurrence.[57][58] This incident underscored the Administrator's central role in crisis management, prompting accelerated investments in resilient technology infrastructure.[59] Since the FAA's creation under the Federal Aviation Act of 1958, 20 individuals have served as Administrator, often bringing backgrounds in military aviation, airline operations, or regulatory experience. The position's evolution reflects shifting priorities from post-World War II expansion to modern challenges like drone integration and controller shortages. The following table enumerates all confirmed Administrators with their service periods:| No. | Name | Term |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Elwood R. Quesada | 1958–1961 |

| 2 | Najeeb E. Halaby | 1961–1965 |

| 3 | William F. McKee | 1965–1968 |

| 4 | John H. Shaffer | 1968–1969 |

| 5 | Alexander Butterfield | 1969–1971 |

| 6 | John L. McLucas | 1971–1975 |

| 7 | Langhorne Bond | 1975–1977 |

| 8 | J. Lynn Helms | 1977–1981 |

| 9 | Donald D. Engen | 1984–1987 |

| 10 | T. Allan McArtor | 1987–1989 |

| 11 | James B. Busey | 1989–1991 |

| 12 | Thomas C. Richards | 1991–1992 |

| 13 | David R. Hinson | 1993–1996 |

| 14 | Jane F. Garvey | 1997–2002 |

| 15 | Marion C. Blakey | 2002–2007 |

| 16 | Robert A. Sturgell (acting) | 2007–2008 |

| 17 | J. Randolph Babbitt | 2009–2011 |

| 18 | Michael P. Huerta | 2013–2018 |

| 19 | Stephen M. Dickson | 2019–2022 |

| 20 | Bryan Bedford | 2025–present |

Key Headquarters Offices and Divisions

The Federal Aviation Administration's headquarters offices in Washington, D.C., oversee critical policy, regulatory, and operational functions central to national aviation safety and efficiency. These entities develop standards, certify systems and personnel, and coordinate with field operations to implement nationwide programs.[64] Aviation Safety (AVS) manages aircraft certification, production approvals, and continued airworthiness, alongside certifying pilots, mechanics, and other aviation professionals. It enforces safety regulations through inspections, investigations, and corrective actions to mitigate risks in design, manufacturing, and operations. AVS also addresses human factors in aviation to reduce errors and enhance system reliability.[65] Air Traffic Organization (ATO) serves as the FAA's operational arm, delivering air navigation services across 29.4 million square miles of U.S. airspace, including en route centers, terminal facilities, and technical operations. Led by a Chief Operating Officer, the ATO manages air traffic flow, develops procedures for safe separation of aircraft, and integrates advanced technologies like NextGen for improved capacity and efficiency.[66] Within AVS, the Flight Standards Service establishes and enforces regulations for flight operations, maintenance, and personnel qualifications under Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations. It conducts surveillance of air carriers and repair stations, issues certificates, and updates standards to adapt to evolving aviation technologies and practices.[67] The Office of Airports (ARP) leads national airport planning, funding allocation through programs like the Airport Improvement Program, and standards for design, construction, and environmental compliance. It ensures airports meet safety criteria while supporting infrastructure development for commercial, general, and cargo aviation.[68] The FAA Reauthorization Act of 2024, signed May 16, 2024, mandates organizational reforms including enhanced leadership structures and workforce training to bolster oversight in these headquarters divisions, aiming to address staffing shortages and improve regulatory agility through fiscal year 2028.[69][70]Regional and Field Operations

The Federal Aviation Administration divides its operational oversight into nine regional offices, each responsible for adapting national aviation policies to local conditions across designated geographic areas, including states and territories. These offices coordinate inspections of aircraft, airports, and air carriers; enforce regulatory compliance through audits and investigations; and facilitate collaboration with local stakeholders such as airport authorities and aviation businesses to address region-specific safety challenges.[71] At the field level, Flight Standards District Offices (FSDOs), numbering over 80 nationwide and reporting to regional administrations, perform hands-on tasks including certification of air carriers and operations, aircraft maintenance oversight, incident investigations, and responses to immediate threats like unauthorized low-altitude flights or accident reporting. FSDOs conduct routine surveillance and enforcement to verify adherence to Federal Aviation Regulations, such as 14 CFR parts governing flight operations and airworthiness, often initiating corrective actions or legal referrals for violations.[72][72] Specialized facilities support regional and field activities, notably the Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, which delivers training programs for FAA inspectors, air traffic controllers, and technical staff, encompassing courses on regulatory enforcement, safety inspections, and operational procedures to standardize skills across regions. Established in 1972 and expanded over decades, the center handles thousands of training sessions annually, integrating field feedback to refine curricula for practical application in diverse environments.[73] Regional offices contribute operational data to national systems via tools like the Traffic Flow Management System, enabling real-time integration for events such as convective weather outbreaks; for example, during summer thunderstorms in the Eastern Region, field teams coordinate with National Weather Service forecasts to implement targeted ground delay programs or airspace reroutes, reducing delays attributed to weather by up to 20% in affected corridors through localized adjustments. Such responses prioritize causal factors like reduced visibility or turbulence, drawing on empirical data from regional surveillance radars and incident reports to inform national decision-making without overriding local expertise.[15][74]Historical Development

Early Aviation Regulation and Pre-FAA Era

The federal government's initial involvement in civil aviation regulation began with the Air Commerce Act of May 20, 1926, which assigned the Department of Commerce responsibility for promoting air commerce through safety measures, including issuing and enforcing air traffic rules, licensing pilots, certifying aircraft, establishing airways, and maintaining navigation aids.[3] This legislation marked the first comprehensive federal framework for non-military aviation, forming the Aeronautics Branch within the Commerce Department to oversee these functions, though enforcement remained limited amid rapid technological advancements and commercial growth.[3] In 1934, the Aeronautics Branch was reorganized into the Bureau of Air Commerce, which expanded efforts by establishing early air traffic control centers, such as the one in Newark in 1936.[3] The Civil Aeronautics Act of June 23, 1938, further centralized authority by creating the independent Civil Aeronautics Authority (CAA), an entity tasked with economic regulation, safety rulemaking, accident investigation via an Air Safety Board, and operational oversight.[3] This authority was soon restructured into the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) for independent functions like route certification, fare setting, and investigations, while the Administrator of Civil Aeronautics—housed under the Commerce Department—handled day-to-day operations, including certification of pilots, aircraft, and airports, as well as air traffic control.[3] Despite these steps, the dual structure perpetuated fragmentation, with the CAB focusing on economic and investigative roles separate from operational execution. Post-World War II, civil aviation experienced explosive growth, with commercial air traffic more than doubling by 1956 compared to wartime levels, driven by faster propeller aircraft and the introduction of jetliners like the de Havilland Comet in 1952, which flew at speeds over 480 mph versus the DC-3's 180 mph.[3] However, air traffic control infrastructure lagged, relying on visual flight rules that permitted deviations from assigned airways for sightseeing, and lacking unified authority over military and civilian flights, which contributed to rising mid-air collision risks.[3] This vulnerability was starkly demonstrated on June 30, 1956, when Trans World Airlines Flight 2 (a Lockheed L-1049 Super Constellation) and United Airlines Flight 718 (a Douglas DC-7) collided at approximately 21,000 feet over the Grand Canyon, killing all 128 people aboard in the deadliest U.S. commercial aviation disaster to that point.[75] [3] The accident, involving deviations from airways under clear visual conditions without radar coverage or coordinated control, underscored the inadequacies of the pre-existing regulatory regime, where the Civil Aeronautics Administration's limited mandate failed to impose mandatory instrument flight rules or integrate military airspace management, fueling demands for a single federal entity to prioritize safety over fragmented jurisdictional lines.[3]Formation of the FAA in 1958

The Federal Aviation Act of 1958, signed into law by President Dwight D. Eisenhower on August 23, 1958, established the Federal Aviation Agency as an independent entity to centralize aviation safety regulation and air traffic control.[76] This legislation responded directly to a series of fatal mid-air collisions in the mid-1950s, including the June 30, 1956, crash over the Grand Canyon between a TWA Lockheed Super Constellation and a United Airlines Douglas DC-7, which killed all 128 people aboard both aircraft due to inadequate air traffic separation in uncontrolled airspace.[75] Further incidents, such as the April 21, 1958, collision near Las Vegas between a United Airlines DC-7 and a U.S. Air Force F-100 Super Sabre jet trainer at 21,000 feet, which claimed 49 lives, underscored the dangers of fragmented oversight between civil and military operations amid rising jet traffic volumes.[77] These accidents, occurring against the backdrop of Cold War military aviation demands, highlighted the need for unified control of the national airspace to prevent conflicts between commercial flights and high-speed military aircraft.[78] The Act transferred regulatory and promotional functions previously handled by the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA) to the new agency, while vesting it with exclusive authority over air traffic rules, aircraft certification, and the safe utilization of navigable airspace by both civil and military users.[3] This shift dissolved the CAA's divided responsibilities—where safety enforcement competed with economic promotion—and empowered the agency to issue binding safety regulations without prior reliance on the Civil Aeronautics Board for approval.[79] Military-civil integration was a core mandate, requiring coordination with the Department of Defense to establish common procedures for airspace access, addressing prior jurisdictional overlaps that had contributed to near-misses and collisions.[1] The agency's formation on August 23, 1958, marked the end of the CAA's 20-year tenure, with full operational transition by November 1, 1958.[3] Retired U.S. Air Force Lieutenant General Elwood R. "Pete" Quesada was appointed as the first Federal Aviation Agency Administrator on November 1, 1958, bringing tactical airpower expertise from World War II to address jet-age challenges like supersonic speeds and en route congestion.[80] Under Quesada's leadership, the agency prioritized radar-based air traffic enhancements, including the expansion of positive control zones where controllers issued mandatory radar vectors to maintain separation, reducing reliance on procedural clearances alone.[81] These measures yielded verifiable safety gains, with mid-air collision rates declining as radar coverage expanded; for instance, the introduction of en route radar facilities post-1958 enabled real-time monitoring that prevented several potential incidents in high-traffic corridors.[82] By 1960, Quesada's initiatives had laid groundwork for beacon-equipped positive control testing, contributing to a broader drop in accident rates as civil and military flights operated under unified protocols.[3]Reorganizations and Growth in the 1960s-1970s

The Department of Transportation Act, enacted on October 15, 1966, created a cabinet-level Department of Transportation (DOT) that consolidated federal transportation functions, subordinating the FAA to the Secretary of Transportation while affirming the agency's primacy in aviation safety regulation.[3][83] This structural shift integrated FAA operations into broader policy coordination but preserved its operational autonomy in safety matters, amid concerns from agency leaders about potential dilution of expertise-driven decision-making.[83] The reorganization reflected the era's push for unified transportation oversight as air traffic volumes surged, with the FAA absorbing new responsibilities under DOT while expanding its workforce and facilities to handle jet-era demands. Commercial aviation experienced explosive growth in the 1960s-1970s, with revenue passenger miles increasing at a compound annual rate exceeding 12% from the late 1940s through 1973, driven by affordable jet travel and economic expansion that nearly tripled passenger enplanements over the decade.[84] This boom, fueled by technological advances like turbofan engines enabling efficient long-haul flights, strained existing infrastructure, prompting the FAA to initiate modernization of the National Airspace System (NAS). In 1970, the agency issued its National Aviation System Plan, outlining long-range investments in automation, radar upgrades, and airway facilities to accommodate projected traffic doublings, building on experimental computer integrations from 1965 onward.[85][86] Concurrently, the introduction of wide-body jets—such as the Boeing 747, certified by the FAA in 1969—necessitated regulatory adaptations for higher passenger densities, including enhanced evacuation standards and structural integrity rules to mitigate risks from larger fuselages and fuel loads.[87] The FAA also navigated high-profile initiatives like the supersonic transport (SST) program, which secured federal funding in the early 1960s for designs by Boeing and Lockheed, with the agency providing certification oversight and noise studies.[88] However, escalating development costs surpassing $1 billion, coupled with sonic boom environmental impacts, led Congress to terminate U.S. SST funding in March 1971, effectively ending the effort absent private viability.[89] Paralleling these technological pursuits, a wave of aircraft hijackings—reaching 27 attempts in 1970, many successful—prompted FAA countermeasures, including voluntary deterrence protocols in the late 1960s and mandatory passenger screening expansions by February 1972 across all U.S. scheduled airlines using magnetometers and hand searches.[90][91] These responses causally linked rising operational volumes to proactive security layering, sustaining safety amid volume-driven complexity without compromising the era's growth trajectory.Deregulation, Expansion, and Post-1980s Changes