Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Surveyor program

View on Wikipedia

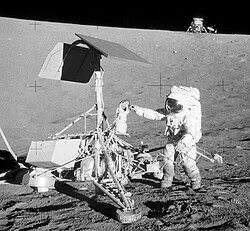

Surveyor 3 resting on the surface of the Moon, taken by Apollo 12 astronauts | |

| Program overview | |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Organization | NASA |

| Purpose | Demonstrate soft landing on the Moon |

| Status | Completed |

| Program history | |

| Cost | US$469 million |

| First flight | May 30–June 2, 1966 |

| Last flight | January 7–10, 1968 |

| Successes | 5 |

| Failures | 2 |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral LC-36 |

| Vehicle information | |

| Launch vehicle | Atlas-Centaur |

The Surveyor program was a NASA program that, from June 1966 through January 1968, sent seven robotic spacecraft to the surface of the Moon. Its primary goal was to demonstrate the feasibility of soft landings on the Moon. The Surveyor craft were the first American spacecraft to achieve soft landing on an extraterrestrial body. The missions called for the craft to travel directly to the Moon on an impact trajectory, a journey that lasted 63 to 65 hours, and ended with a deceleration of just over three minutes to a soft landing.[1]

The program was implemented by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) to prepare for the Apollo program, and started in 1960. JPL selected Hughes Aircraft in 1961 to develop the spacecraft system.[1] The total cost of the Surveyor program was officially $469 million.

Five of the Surveyor craft successfully soft-landed on the Moon, including the first one. The other two failed: Surveyor 2 crashed at high velocity after a failed mid-course correction, and Surveyor 4 lost contact (possibly exploding) 2.5 minutes before its scheduled touch-down.

All seven spacecraft are still on the Moon; none of the missions included returning them to Earth. Some parts of Surveyor 3 were returned to Earth by the crew of Apollo 12, which landed near it in 1969. The camera from this craft is on display at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC.[2]

Goals

[edit]The program performed several other services beyond its primary goal of demonstrating soft landings. The ability of spacecraft to make midcourse corrections was demonstrated, and the landers carried instruments to help evaluate the suitability of their landing sites for crewed Apollo landings. Several Surveyor spacecraft had robotic shovels designed to test lunar soil mechanics. Before the Soviet Luna 9 mission (landing four months before Surveyor 1) and the Surveyor project, it was unknown how deep the dust on the Moon was. If the dust was too deep, then no astronaut could land. The Surveyor program proved that landings were possible. Some of the Surveyors also had alpha scattering instruments and magnets, which helped determine the chemical composition of the soil.

The simple and reliable mission architecture was a pragmatic approach to solving the most critical space engineering challenges of the time, namely the closed-loop terminal descent guidance and control system, throttleable engines, and the radar systems required for determining the lander's altitude and velocity. The Surveyor missions were the first time that NASA tested such systems in the challenging thermal and radiation environment near the Moon.

Launch and lunar landing

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2020) |

Each Surveyor mission consisted of a single unmanned spacecraft designed and built by Hughes Aircraft Company. The launch vehicle was the Atlas-Centaur, which injected the craft directly into trans-lunar flightpath. The craft did not orbit the Moon on reaching it, but directly decelerated from impact trajectory, from 2.6 km/s relative to the Moon before firing retrorockets to a soft landing about 3 minutes 10 seconds later.

Each craft was planned to slow to about 110 m/s (4% of speed before retrofire) by a main solid fuel retrorocket, which fired for 40 seconds starting at an altitude of 75.3 km above the Moon, and then was jettisoned along with the radar unit at 11 km from the surface. The remainder of the trip to the surface, lasting about 2.5 minutes, was handled by smaller doppler radar units and three vernier engines running on liquid fuels fed to them using pressurized helium. (The successful flight profile of Surveyor 5 was given a somewhat shortened vernier flight sequence as a result of a helium leak.) The last 3.4 meters to the surface was accomplished in free fall from zero velocity at that height, after the vernier engines were turned off. This resulted in a landing speed of about 3 m/s. The free-fall to the surface was in an attempt to avoid surface contamination by rocket blast.

Surveyor 1 required a total of about 63 hours (2.6 days) to reach the Moon, and Surveyor 5 required 65 hours (2.7 days). The launch weights (at lunar injection) of the seven Surveyors ranged from 995.2 kilograms (2,194 lb) to 1,040 kilograms (2,290 lb), and their landing weights (minus fuel, jettisoned retrorocket, and radar unit) ranged from 294.3 kilograms (649 lb) to 306 kilograms (675 lb).

Missions

[edit]Surveyor 1

[edit]

Surveyor 1 was launched May 30, 1966 and sent directly into a trajectory to the Moon without any parking orbit. Its retrorockets were turned off at a height of about 3.4 meters above the lunar surface. Surveyor 1 fell freely to the surface from this height, and it landed on the lunar surface on June 2, 1966, on the Oceanus Procellarum. This location was at 2°28′26″S 43°20′20″W / 2.474°S 43.339°W.[3] This is within the northeast portion of the large crater called Flamsteed P (or the Flamsteed Ring). Flamsteed itself lies within Flamsteed P on the south side.

Surveyor 1 transmitted video data from the Moon beginning shortly after its landing through July 14, 1966, but with a period of no operations during the two-week long lunar night of June 14, 1966 through July 7, 1966.

The return of engineering information (temperatures, etc.) from Surveyor 1 continued through January 7, 1967, with several interruptions during the lunar nights. The spacecraft returned data on the motion of the Moon, which would be used to refine the map of its orbital path around the Earth as well as better determine the distance between the two worlds.[4]

Surveyor 2

[edit]Surveyor 2 was launched on September 20, 1966. A mid-course correction failure resulted in the spacecraft losing control.[5][6] Contact was lost with the spacecraft at 9:35 UTC, September 22.[6]

Surveyor 3

[edit]

Launched on April 17, 1967, Surveyor 3 landed on April 20, 1967, at the Mare Cognitum portion of the Oceanus Procellarum (S3° 01' 41.43" W23° 27' 29.55"), in a small crater that was subsequently named Surveyor. It transmitted 6,315 TV images to the Earth, including the first images to show what planet Earth looked like from the Moon's surface.[7]

Surveyor 3 was the first spacecraft to unintentionally lift off from the Moon's surface, which it did twice, due to an anomaly with Surveyor's landing radar, which did not shut off the vernier engines but kept them firing throughout the first touchdown and after it. Surveyor 3's TV and telemetry systems were found to have been damaged by its unplanned landings and liftoffs.[2]

Surveyor 3 was visited by Apollo 12 astronauts Pete Conrad and Alan Bean in November 1969, and remains the only probe visited by humans on another world. The Apollo 12 astronauts excised several components of Surveyor 3, including the television camera, and returned them to Earth for study.[8]

Surveyor 4

[edit]Launched on July 14, 1967, Surveyor 4 crashed after an otherwise flawless mission; telemetry contact was lost 2.5 minutes before touchdown. The solid-fuel retrorocket may have exploded near the end of its scheduled burn.[9] The planned landing target was Sinus Medii (Central Bay) at 0.4° north latitude and 1.33° west longitude.

Surveyor 5

[edit]

Surveyor 5 was launched on September 8, 1967 from Cape Canaveral.[10] It landed on Mare Tranquillitatis on September 11, 1967. The spacecraft transmitted excellent data for all experiments from shortly after touchdown until October 18, 1967, with an interval of no transmission from September 24 to October 15, 1967, during the first lunar night. Transmissions were received until November 1, 1967, when shutdown for the second lunar night occurred. Transmissions were resumed on the third and fourth lunar days, with the final transmission occurring on December 17, 1967. A total of 19,118 images were transmitted to Earth.[11]

Surveyor 6

[edit]

Surveyor 6 was the first spacecraft planned to lift off from the Moon's surface.[12]

It was launched on November 7, 1967, and landed on November 10, 1967 in Sinus Medii (near the crash site of Surveyor 4). The successful completion of this mission satisfied the Surveyor program's obligation to the Apollo project.

Surveyor 6's engines were restarted and burned for 2.5 seconds in the first lunar liftoff on November 17 at 10:32 UTC. This created 150 lbf (700 N) of thrust and lifted the vehicle 12 feet (4 m) from the lunar surface. After moving west eight feet, (2.5 m) the spacecraft once again successfully soft landed and continued functioning as designed. On November 24, 1967, the spacecraft was shut down for the two-week lunar night. Contact was made on December 14, 1967, but no useful data was obtained.

Surveyor 7

[edit]

Surveyor 7 was launched on January 7, 1968, landing on the lunar surface on January 10, 1968, on the outer rim of the crater Tycho. Operations of the spacecraft began shortly after the soft landing. On January 20, while the craft was still in daylight, the TV camera clearly saw two laser beams aimed at it from the night side of the crescent Earth, one from Kitt Peak National Observatory, Tucson, Arizona, and the other at Table Mountain at Wrightwood, California.[13][14]

Operations on the second lunar day occurred from February 12 to 21, 1968. The mission objectives were fully satisfied by the spacecraft operations. Battery damage was suffered during the first lunar night and transmission contact was subsequently sporadic. Contact with Surveyor 7 was lost on February 21, 1968.[15]

Surveyor mission list

[edit]

Surveyor-Model were generic mass simulators,[16][17] while Surveyor SD had the same structure as the real Surveyor landers with all equipment replaced by dummy weights.[18] These served to test Atlas-Centaur launch vehicle performance, and were not intended to reach the Moon.[16][17][18]

Of the seven Surveyor missions, five were successful.

| Mission | Launch | Rocket | Arrived at Moon | Disposition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surveyor-Model 1 | December 11, 1964 | Atlas-LV3C Centaur-C AC-4 | - | 165 × 178 km Earth orbit |

| Surveyor SD-1 | March 02, 1965 | Atlas-LV3C Centaur-C AC-5 | - | destroyed on launch |

| Surveyor SD-2 | August 11, 1965 | Atlas-LV3C Centaur-D AC-6 | - | 166 × 815085 km Earth orbit |

| Surveyor-Model 2 | April 08, 1966 | Atlas-LV3C Centaur-D AC-8 | - | 175 × 343 km Earth orbit |

| Surveyor 1 | May 30, 1966 | Atlas-LV3C Centaur-D AC-10 | June 2, 1966 | landed on Oceanus Procellarum |

| Surveyor 2 | September 20, 1966 | Atlas-LV3C Centaur-D AC-7 | September 23, 1966 | crashed near Copernicus crater |

| Surveyor-Model 3 | October 26,1966 | Atlas-LV3C Centaur-D AC-9 | - | 165 × 470040 km Earth orbit |

| Surveyor 3 | April 17, 1967 | Atlas-LV3C Centaur-D AC-12 | April 20, 1967 | landed on Oceanus Procellarum |

| Surveyor 4 | July 14, 1967 | Atlas-LV3C Centaur-D AC-11 | July 17, 1967 | crashed on Sinus Medii |

| Surveyor 5 | September 8, 1967 | Atlas-SLV3C Centaur-D AC-13 | September 11, 1967 | landed on Mare Tranquillitatis |

| Surveyor 6 | November 7, 1967 | Atlas-SLV3C Centaur-D AC-14 | November 10, 1967 | landed on Sinus Medii |

| Surveyor 7 | January 7, 1968 | Atlas-SLV3C Centaur-D AC-15 | January 10, 1968 | landed near Tycho crater |

Space Race competition

[edit]

During the time of the Surveyor missions, the United States was actively involved in the Space Race with the Soviet Union. Thus, the Surveyor 1 landing in June 1966, only four months after the Soviet Luna 9 probe landed in February, was an indication the programs were at similar stages.[19]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Kloman (1972). "NASA Unmanned Space Project Management - Surveyor and Lunar Orbiter" (PDF). NASA SP-4901.

- ^ a b https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraft/display.action?id=1967-035A – 24 January 2020

- ^ "Surveyor 1". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive.

- ^ "Aeronautics and Astronautics, 1967" (PDF). NASA. p. 5. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ "Central Moon Landing Try for Surveyor 2". The Deseret News. 19 September 1966.

- ^ a b "Surveyor 2". NSSDCA Master Catalog.

- ^ "First image of Earth from the surface of the Moon: Surveyor 3".

- ^ Robert Z. Pearlman (November 23, 2019). "50 Years On, Where Are the Surveyor 3 Moon Probe Parts Retrieved by Apollo 12?". Space.com. Retrieved October 2, 2024.

- ^ "Surveyor 4". NSSDCA Master Catalog.

- ^ "NASA - NSSDCA - Spacecraft - Telemetry Details". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved March 30, 2019.

- ^ "NASA - NSSDCA - Spacecraft - Details". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved March 30, 2019.

- ^ Siddiqi, Asif A. (2018). Beyond Earth: A Chronicle of Deep Space Exploration, 1958–2016 (PDF). The NASA history series (second ed.). Washington, DC: NASA History Program Office. p. 1. ISBN 9781626830424. LCCN 2017059404. SP2018-4041. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 24, 2019.

- ^ "Boeing: Satellite Development Center - Scientific Exploration - Surveyor". Archived from the original on February 7, 2010. Retrieved March 31, 2010. Notes on the laser experiment.

- ^ [1] photo of the beam from the 2-watt green argon Hughes laser at Table Mountain

- ^ "Surveyor VII". University of Arizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. November 28, 2017. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ^ a b "Surveyor Model 1 - NASA Science". science.nasa.gov. December 27, 2017. Retrieved October 2, 2024.

- ^ a b "Surveyor-Model". Gunter's Space Page. Retrieved October 2, 2024.

- ^ a b "Surveyor-SD". Gunter's Space Page. Retrieved October 2, 2024.

- ^ Reeves, Robert (1994). "Exploring the Moon". The superpower space race: An explosive rivalry through the solar system. Boston, MA, USA: Springer. pp. 101–130. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-5986-7_4. ISBN 978-1-4899-5986-7.

External links

[edit]- Surveyor (1966–1968)

- Surveyor Program Results (PDF) 1969

- Surveyor Program Results (Good Quality Color PDF) 1969

- Analysis of Surveyor 3 material and photographs returned by Apollo 12 (PDF) 1972

- Exploring the Moon: The Surveyor Program

- Details of Surveyor 1 launch, and also the entire program

- Digitizing the Surveyor Lander Imaging Dataset | Lunar and Planetary Laboratory & Department of Planetary Sciences | The University of Arizona

Surveyor program

View on GrokipediaBackground and Objectives

Historical Context

The launch of Sputnik 1 by the Soviet Union on October 4, 1957, ignited the Sputnik crisis, exposing perceived gaps in U.S. technological and scientific capabilities during the Cold War and prompting a major overhaul of American space policy. In direct response, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the National Aeronautics and Space Act into law on July 29, 1958, creating the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) as an independent civilian agency responsible for coordinating the nation's non-military aeronautics and space research efforts. This marked a shift from fragmented military-led initiatives, such as those under the Army Ballistic Missile Agency and Navy, to a unified civilian framework, absorbing the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) and integrating other federal space activities to foster peaceful exploration and technological advancement.[4][5] NASA's early lunar ambitions built on this foundation through the Ranger program, launched in 1959 under JPL management, which employed hard-landing spacecraft to transmit close-up photographs of the Moon's surface during impact. While Ranger provided valuable imagery, its destructive endpoints limited direct assessment of landing viability, underscoring the need for soft-landing precursors to the crewed Apollo missions announced in 1961. The Surveyor program emerged as this critical bridge, designed to demonstrate controlled descents and evaluate the lunar environment's compatibility with human exploration hardware.[6] Formally approved in spring 1960, the Surveyor program was assigned to NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory for oversight, with Hughes Aircraft Company selected as prime contractor in 1961 following a competitive evaluation of industry proposals. The initiative's total cost reached $469 million by completion—equivalent to roughly $4 billion in 2025 dollars, adjusted for inflation—reflecting the scale of technological development required. Its momentum surged after President John F. Kennedy's address to Congress on May 25, 1961, where he pledged to achieve a crewed lunar landing before decade's end, positioning Surveyor as an essential risk-reduction effort within the broader Apollo framework.[7][8][9][10][6] A key driver for Surveyor's initiation was mounting uncertainty about the Moon's surface bearing strength, informed by geological analyses and early spacecraft observations from 1959 to 1963, including Ranger missions that revealed potential hazards like fine dust or unstable regolith unable to support heavy landers. These studies, drawing on terrestrial analogs and preliminary orbital data, emphasized the risks of sinkage or instability, compelling NASA to prioritize in-situ testing to ensure Apollo's feasibility.[11]Program Goals

The primary goal of the Surveyor program was to demonstrate the feasibility of soft lunar landings and validate the technology for future manned missions, particularly to assess compatibility with Apollo spacecraft descent techniques and landing site selection.[1] This involved developing automated spacecraft capable of achieving controlled touchdowns on the Moon's surface to gather engineering data on landing dynamics and surface interaction.[1] Secondary objectives focused on scientific investigations of the lunar surface, including acquiring high-resolution photographic coverage for topographic and geologic mapping, performing soil mechanics tests with a surface sampler to evaluate properties such as bearing strength and cohesion, and conducting chemical composition analysis using an alpha-scattering instrument to identify elemental abundances.[1] These efforts aimed to provide essential data on the Moon's regolith characteristics and composition to support Apollo planning.[1] Tertiary aims included testing midcourse trajectory corrections for navigation precision, radar altimetry for descent control, and the spacecraft's durability in the lunar environment, encompassing radiation exposure and temperature extremes ranging from -280°F to +260°F.[1] Quantitative targets encompassed landing accuracy within approximately 15 km of the designated site and camera image resolution capable of resolving details as fine as 1/12 inch (about 2 mm) on the surface.[12][6]Development and Design

The Surveyor spacecraft were designed and built by Hughes Aircraft Company under contract to NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.[13]Spacecraft Architecture

The Surveyor spacecraft utilized a central spaceframe constructed from aluminum, forming a triangular structure measuring 3.0 meters across the base and 0.4 meters in height, with the overall landed mass ranging from 270 to 303 kilograms when fully fueled for vernier maneuvers.[1] This lightweight yet robust design provided mounting points for subsystems while minimizing mass to meet launch constraints.[14] Attached to the spaceframe were three folding landing legs, each incorporating solid-propellant vernier engines for fine attitude control, along with hydraulic shock absorbers and crushable honeycomb footpads to dissipate landing impact energies.[14] The legs deployed to a full extension of 4.1 meters, enabling the spacecraft to maintain stability on uneven lunar terrain with slopes up to 15 degrees.[1] Power was supplied by deployable solar panels covering 1.6 square meters, capable of generating a maximum of 85 watts under lunar noon conditions, paired with silver-zinc batteries that sustained operations for more than 200 hours, including through the extended lunar night.[14] Thermal management relied on passive louvers to regulate heat rejection and radioisotope heaters to prevent freezing of critical components amid temperature extremes from -150°C to +120°C.[1] For communication, the spacecraft featured two omnidirectional antennas for low-gain links and a high-gain planar array antenna, both operating in the S-band at 2.2 GHz to transmit telemetry data to NASA's Deep Space Network ground stations.[14] An onboard digital command decoder handled basic sequencing of operations and radar data processing, but the system offered no full autonomy, depending on real-time ground commands for mission adjustments.[1] This architecture supported the precise soft landings essential to the program's objectives.[14]Key Instruments and Technologies

The Surveyor spacecraft featured a television camera as its primary imaging system, utilizing a vidicon tube to capture high-resolution images of the lunar surface. This 600-line scan camera operated in both wide-angle and narrow-angle modes, providing fields of view of approximately 25.4° × 25.4° and 6.4° × 6.4°, respectively, with adjustable focus ranging from 1.23 meters to infinity. The camera supported remote pan and tilt control from Earth, enabling 360° azimuthal rotation and elevation adjustments from +40° to -60°, along with features such as polarizing filters, color filters, and an iris for photometric and polarimetric observations. It was capable of producing over 30,000 high-quality frames per mission through integration times up to 30 minutes, facilitating detailed topographic mapping, horizon measurements, and star surveys for attitude determination.[15][1][16] The surface sampler arm, deployed on select Surveyor missions, consisted of a 1.5-meter extensible pantograph boom equipped with a scoop-shaped claw for mechanical interaction with the lunar regolith. This arm, driven by motors and supported by a lazy-tongs mechanism with coiled springs, allowed for soil digging, trench excavation up to 20 cm deep, and the overturning of small rocks or fragments up to 12 cm in size. It conducted bearing strength tests by applying vertical loads, with capabilities up to approximately 3.6 kg, measuring soil mechanics through motor current feedback to assess cohesion, friction angle, and density. The sampler also incorporated horseshoe magnets rated at 700 gauss to evaluate the magnetic properties of surface materials, aiding in the characterization of regolith adhesion and composition.[1][17] The alpha scattering instrument employed a curium-242 radioactive source, with six collimated spots emitting alpha particles at 6.11 MeV energy and a half-life of 163 days, to perform in situ elemental analysis of the lunar soil. This device used silicon detectors to measure backscattered alpha particles and induced protons, alongside X-ray fluorescence generated by alpha interactions, enabling the identification of major elements such as silicon (18.5–20%), aluminum (6–9%), iron (~6%), and oxygen (~57–58%) in the regolith to depths of a few microns. The 13-kg instrument, deployable via the surface sampler arm or a nylon cord, operated at low power (2 W nominal, up to 17 W with heaters) across temperatures from -40°C to +50°C, with data transmission rates of 2200 bits per second for alpha spectra and 550 bits per second for protons. Calibration was achieved through an onboard pulse generator simulating 2.5–3.5 MeV events.[15][1] Additional engineering technologies included strain gauges mounted on the spacecraft's landing legs and shock absorbers to record axial loads and touchdown dynamics, providing data on surface impact forces during descent. Environmental sensors encompassed thermistors and platinum-resistance thermometers for monitoring temperatures across 74 components and the regolith surface, maintaining operational ranges like battery limits below 75°F. A radar altimeter and Doppler velocity sensor (RADVS) measured three-axis velocity from 0 to 10 m/s and altitude from 13 feet to 50,000 feet, supporting precise descent control with a target touchdown speed of about 3.4 m/s. These sensors ensured reliable performance in the lunar vacuum and thermal extremes.[15][13][1] Key innovations in the Surveyor program included the first widespread use of solid-state amplifiers in telemetry, radar, and television systems, enhancing signal processing reliability and reducing failure risks in the space environment. The electronics were radiation-hardened to withstand doses up to 10^5 rads, incorporating thermal blankets (75 layers of aluminized Mylar), gold-plated surfaces, and temperature-compensated designs to endure -50°C to +150°C fluctuations and cosmic radiation, enabling extended operations of over 17 months across missions. These advancements, integrated into the spacecraft architecture, facilitated autonomous instrument deployment and data return without human intervention.[15][1]Launch and Landing Procedures

Launch Vehicles and Sequence

The Surveyor program utilized the Atlas LV-3C launch vehicle paired with the Centaur upper stage as its primary rocket system for all missions, enabling direct injection into a translunar trajectory. The Atlas booster, derived from the SM-65 missile, provided initial ascent with its MA-5 engine cluster consisting of two booster engines, one sustainer engine, and two vernier engines, while the Centaur stage employed two Pratt & Whitney RL10A-3 liquid hydrogen/liquid oxygen engines, each producing approximately 15,000 pounds of thrust. This configuration had a lift-off mass of about 302,000 pounds and could deliver roughly 6,000 kilograms to low Earth orbit, sufficient for the approximately 1,000-kilogram Surveyor spacecraft plus adapters and vernier propulsion systems.[18][19] Pre-launch preparations began with spacecraft integration at the Hughes Aircraft Company facility in El Segundo, California, where the Surveyor lander was mated to the Centaur stage and enclosed in a payload fairing. The integrated stack underwent rigorous vibration and shock testing to simulate launch stresses, followed by transportation to Cape Canaveral's Space Launch Complex 36 for final assembly with the Atlas booster. Propellant loading included RP-1 and liquid oxygen for the Atlas, liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen for the Centaur, and hydrazine for the spacecraft's vernier engines used in attitude control and trajectory corrections. Countdown procedures emphasized precise timing, with lift-off targeted within seconds of the launch window to align with lunar transit opportunities.[20][18] Launches occurred from Cape Canaveral's SLC-36, with the sequence initiating at lift-off (T+0) on an azimuth of approximately 72-102 degrees depending on the mission. The Atlas booster engines ignited simultaneously, achieving booster engine cutoff (BECO) at about 142 seconds and sustainer engine cutoff (SECO) at roughly 239 seconds, placing the vehicle approximately 3,000 kilometers downrange over the Atlantic. Centaur ignition followed shortly after at around 251 seconds, burning for about 438 seconds to perform translunar injection (TLI), reaching a velocity of approximately 10.5 kilometers per second at an altitude of 90 nautical miles. Spacecraft separation occurred about 757 seconds post-liftoff, after which the Surveyor entered a free-coast phase.[18] The translunar trajectory involved a 63- to 65-hour coast to the Moon, during which a single midcourse correction maneuver was typically performed using the spacecraft's hydrazine-fueled vernier engines, imparting a delta-v of 30 to 99 meters per second to refine the aim point. This correction, often executed 16 to 20 hours after launch, ensured accurate lunar approach within the vernier system's capabilities. The overall system demonstrated high reliability, with seven operational launches successfully conducted between 1966 and 1968, building on two prior test flights: Surveyor SD-1 on March 2, 1965, which failed due to an early engine shutdown and explosion, and Surveyor SD-2 on August 11, 1965, which successfully simulated a lunar transfer trajectory.[18][21][22]Descent and Soft Landing Mechanics

The descent phase of the Surveyor missions began as the spacecraft approached the Moon directly from its translunar trajectory on a near-vertical path at velocities around 2.6 km/s. The radar altimeter and Doppler velocity sensor (RADVS) system initiated lock-on at altitudes of approximately 80 km, providing real-time altitude and velocity measurements through four radar beams to guide the terminal descent.[23] The solid-propellant retro-rocket ignited at approximately 80 km altitude, delivering a thrust of 35,600 to 44,500 N for roughly 40 seconds until burnout at about 12 km altitude, decelerating the vehicle from approximately 2.6 km/s to 120-130 m/s while the spacecraft oriented its roll axis perpendicular to the surface.[23] This phase addressed the high inertial velocity from the translunar trajectory, with the retro-rocket jettisoned post-burnout to avoid contamination.[1] In the final descent, three throttleable vernier engines, fueled by hypergolic propellants such as monomethylhydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide, provided precise control with individual thrusts ranging from 133 to 462 N. These engines operated in a closed-loop guidance mode, using RADVS data for velocity and altitude feedback alongside an inertial measurement unit (IMU) with gyroscopes for attitude stabilization, targeting a vertical touchdown speed below 3.7 m/s and horizontal velocity under 0.5 m/s.[23] The system incorporated basic hazard avoidance through radar echo analysis, capable of detecting slopes exceeding 15° or obstacles larger than 1 m, with an automated abort sequence if unsafe conditions were identified during the approach.[1] The three-legged landing gear facilitated a sequential touchdown, with load-relief mechanisms in the shock absorbers distributing impact forces up to 7,100 N across the footpads, allowing the spacecraft to settle upright.[24] Key challenges included managing dust ejection from engine plumes, which was predicted to rise less than 1 m but was observed to create surface disturbances visible in post-landing imagery, and preventing cratering beneath the engines. To mitigate these, the vernier engines shut down at approximately 4 m altitude, initiating a brief free-fall phase to the surface.[23] Success was defined by an upright orientation with tilt less than 10°, retention of signal lock for immediate telemetry transmission, and full power availability from solar panels and batteries post-touchdown, criteria met in the program's successful missions through rigorous pre-flight simulations of lunar gravity and regolith interactions.[1]Missions

Surveyor 1

Surveyor 1, launched on May 30, 1966, at 14:41:01 UTC from Cape Kennedy's Pad 36A aboard an Atlas-Centaur rocket, marked the inaugural mission of NASA's Surveyor program.[13] The spacecraft traveled for approximately 63 hours before achieving a successful soft landing on June 2, 1966, at 06:17:36 UTC in the Oceanus Procellarum region at coordinates approximately 2.5° S, 43.3° W.[25] This touchdown, occurring at a velocity of about 3.4 m/s, represented the first U.S. soft landing on the lunar surface, validating the program's landing gear design with its three shock-absorbing legs equipped with strain gauges that measured surface interactions.[13] During operations, Surveyor 1 transmitted 11,237 television images over its primary mission duration of 43 days, capturing high-resolution views of the surrounding terrain, including panoramic mosaics that revealed a flat, cratered mare landscape with scattered rocks up to 1 meter in size.[12] The spacecraft's imaging system, a single television camera with adjustable focus and tilt, operated continuously during lunar daylight, providing real-time data on surface features and confirming the site's suitability for future crewed landings. Additionally, initial soil interaction assessments from leg strain data and the absence of significant dust ejection during descent indicated a cohesive, fine-grained regolith with sufficient bearing strength to support the lander's 267 kg mass, yielding a penetration depth of about 11 cm in one leg.[26] Minor anomalies included a partial failure in one low-gain antenna deployment, though communications remained robust, and successful command verifications were conducted from NASA's Goldstone tracking station, enabling precise attitude adjustments.[25] The mission's batteries, with a capacity of 162 ampere-hours at lunar sunset, demonstrated resilience by powering through the first lunar night, allowing intermittent signals until final contact loss on January 7, 1967, after surviving temperatures as low as -140°C.[13] This extended operation served as a critical proof-of-concept for lunar surface endurance, gathering engineering data that affirmed the spacecraft's thermal and power systems for prolonged stays. Overall, Surveyor 1's success, achieved just months after the Soviet Luna 13's landing earlier that year, provided essential baseline validation for the Apollo program's lunar module design and site selection criteria.[27]Surveyor 2

Surveyor 2, launched on September 20, 1966, at 12:32 UT from Cape Canaveral's Launch Complex 36A aboard an Atlas-Centaur rocket (AC-7), was the second spacecraft in NASA's Surveyor program aimed at achieving a soft landing on the Moon.[28] The mission targeted Sinus Medii, a central lunar plain considered a potential Apollo landing site due to its representative mare terrain.[12] Following a nominal launch and initial coast phase, the spacecraft underwent a planned midcourse correction approximately 16 hours and 28 minutes after liftoff to refine its trajectory toward the intended landing site.[29] The midcourse maneuver involved a 9.8-second burn from the spacecraft's three vernier engines, each capable of 30-104 pounds of thrust, to achieve a delta-v of approximately 9.6 m/s and correct for any post-injection errors.[29] However, the starboard vernier engine (Engine 3) failed to ignite, likely due to an oxidizer flow restriction or electrical issue, while the other two engines fired unevenly at 85 lb and 65 lb thrust, respectively.[29] This imbalance caused a loss of attitude control, initiating an uncontrolled spin that telemetry indicated at around 360° per minute, with fuel sloshing exacerbating the instability.[30] Despite 39 subsequent attempts to reignite the failed engine and restore stability over the next day, the spacecraft continued tumbling, and contact was lost on September 22, 1966, at 09:35 UT, just 30 seconds after retro-rocket ignition for descent.[28] The probe ultimately crashed into the lunar surface on September 23, 1966, at approximately 5°30' N, 12° W, southeast of Copernicus crater, with no further signals received post-impact.[31] A post-mission investigation by NASA's Failure Review Board analyzed telemetry data, confirming the vernier malfunction through strain gauge readings showing no thrust from the affected engine and gyroscopic evidence of the spin.[29] The exact cause remained undetermined, but possibilities included a propulsion system anomaly or command sequencing error during the burn.[29] This failure delayed the Surveyor program by several months, as resources shifted to thorough reviews, pushing the next launch to April 1967.[12] Key engineering adjustments for subsequent missions, including Surveyor 3 onward, incorporated redundant engine readiness checks, enhanced pre-burn diagnostics, design modifications to the vernier system for better reliability, and improved guidance software with additional command redundancy to prevent attitude loss.[29] These changes ensured more robust midcourse corrections and contributed to the success of later landings.[12]Surveyor 3

Surveyor 3, the third spacecraft in NASA's uncrewed lunar landing program, launched on April 17, 1967, at 07:05:01 GMT from Cape Kennedy's Launch Complex 36B aboard an Atlas-Centaur rocket.[32] The mission achieved a soft landing on April 20, 1967, at 00:04:53 GMT in the Oceanus Procellarum at coordinates 2.94° S latitude and 23.34° W longitude, near a 200-meter-diameter crater known as West Crater.[32] During descent, the spacecraft experienced an anomaly when the main retro-rocket failed to shut off properly due to radar confusion from reflective surface rocks, resulting in two brief bounces—approximately 10 meters and 3 meters high—before final touchdown.[32] This event provided valuable data on landing dynamics but did not compromise the mission's primary objectives of surface imaging and soil mechanics testing.[33] Following activation, Surveyor 3 operated successfully for the duration of the first lunar day, transmitting over 6,300 television images of the surrounding terrain using its dual-lens camera system.[32] The surface sampler arm, a key instrument for mechanical testing, performed extensive experiments including digging four trenches to a maximum depth of about 18 cm and conducting eight bearing tests along with 14 impact tests by dropping the scoop from varying heights.[32] These activities assessed soil properties, revealing a bearing strength of up to approximately 0.7 N/cm², comparable to wet sand, and a friction coefficient between 1.0 and 1.2, which informed future landing site evaluations.[32] The spacecraft was commanded into a low-power hibernation mode on May 2, 1967, ahead of the first lunar night, but reactivation attempts on May 13 failed, marking the end of operations after about 23 Earth days on the surface.[32] Mission operations encountered several anomalies, notably with the television camera, which experienced erratic stepping in both azimuth and elevation modes—failing in 432 of 10,045 azimuth commands and 67 of 3,594 elevation commands—likely due to thermal stresses causing mirror sticking or contamination from possible lunar dust or vernier engine residues.[32] Overheating led to calibration errors, and glare from low sun angles exacerbated imaging issues, though the system remained functional for most transmissions.[32] Telemetry data also degraded intermittently due to arcing in the ionized plasma from the landing, but solar panels performed nominally without significant power loss, providing adequate energy throughout the active period.[32] In a unique post-mission development, Apollo 12 astronauts Pete Conrad and Alan Bean visited the Surveyor 3 site on November 19, 1969, landing their Lunar Module approximately 155 meters away, and retrieved components including the television camera and a portion of the surface sampler scoop for return to Earth. Initial analysis of the camera revealed traces of the bacterium Streptococcus mitis, prompting claims of microbial survival in the lunar environment after 31 months of exposure to vacuum, radiation, and temperature extremes.[34] Subsequent investigations, including a 2011 study, debunked these claims, attributing the bacteria to terrestrial contamination introduced during handling of the samples after retrieval on Earth.[35]Surveyor 4

Surveyor 4, the fourth spacecraft in NASA's Surveyor program, was launched on July 14, 1967, from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station aboard an Atlas-Centaur rocket, targeting a landing site in Sinus Medii near the Moon's center.[36] The mission proceeded nominally through the cruise phase, during which the spacecraft executed 10 successful midcourse corrections to refine its trajectory toward the lunar surface.[37] Additionally, the television camera captured and transmitted 25 images of Earth and space during transit, providing early verification of the imaging system's functionality despite the lack of lunar surface operations.[37] As the spacecraft approached touchdown on July 17, 1967, terminal descent began with the ignition of the solid-propellant retrorocket at an altitude of approximately 11 kilometers, followed shortly by the hypergolic vernier engines for fine velocity control.[37] However, telemetry contact was abruptly lost 2.5 minutes before the planned landing, with signal cutoff occurring at an altitude of 295 meters.[37] Analysis indicated the most probable cause was an explosion in one of the vernier engines due to unintended hypergolic ignition of residual propellants, possibly triggered by a pressure anomaly or structural issue during the descent phase.[37] This event contrasted with the prior Surveyor 3's complete success, highlighting vulnerabilities in the propulsion system's transition from retrorocket to vernier control.[37] The failure resulted in no surface operations or post-landing data, limiting scientific yield to the pre-descent telemetry and cruise-phase imagery that confirmed spacecraft health up to the final moments.[37] Post-mission review identified key improvements for subsequent flights, including enhanced venting in the hypergolic fuel systems to mitigate ignition risks from propellant residues and the implementation of stricter abort thresholds in the descent software to detect and respond to propulsion anomalies more rapidly.[37] These modifications contributed to the resilience demonstrated in later missions like Surveyor 5, which overcame its own propulsion challenges to achieve the program's first chemical soil analysis.[38]Surveyor 5

Surveyor 5 was launched on September 8, 1967, from Cape Kennedy aboard an Atlas-Centaur rocket, marking the program's first mission equipped with a chemical analysis instrument for lunar soil.[38] The spacecraft successfully landed on September 11, 1967, at 00:46:44 UTC in the Mare Tranquillitatis at coordinates 1.41°N, 23.18°E, on basaltic mare terrain within the inner slope of a small crater measuring approximately 9 by 12 meters.[38] [39] During touchdown, the lander experienced a brief slide of about 0.8 meters downslope on the 19.5° incline, with one footpad penetrating the surface to a depth of around 12 cm in the loose, granular soil, confirming the presence of slightly cohesive regolith capable of supporting landing loads.[38] [39] The mission's primary operations focused on deploying the alpha scattering instrument, the first such device activated on the lunar surface, which operated continuously for 14 days during the initial lunar day to analyze soil composition through particle interactions.[40] [39] This experiment revealed a basaltic-like material with approximately 20% silicon and 15-20% iron by weight, providing the inaugural in-situ chemical profile of extraterrestrial soil and validating the instrument's principles of alpha particle backscattering for elemental detection.[40] Additionally, the spacecraft's television camera captured over 18,000 high-resolution images during the first lunar day, documenting the surrounding terrain, including crater features and soil textures, while a surface sampler arm scooped roughly 0.1 kg of regolith for mechanical testing and magnet attachment experiments.[38] [39] A brief power fluctuation occurred due to dust accumulation on the solar panels following vernier engine firings that simulated landing effects, but the system recovered fully, enabling continued data transmission.[39] Surveyor 5 remained active for 89 days post-landing, enduring three lunar nights through battery preservation and solar reactivation, with additional imaging and limited alpha scattering resumed during the second and fourth lunar days before final cessation on December 17, 1967.[41] [39] This extended performance highlighted the spacecraft's robustness against thermal extremes and surface hazards, shifting the Surveyor program toward advanced analytical capabilities beyond basic imaging and engineering verification.[38]Surveyor 6

Surveyor 6 was launched on November 7, 1967, at 07:39:01 UT from Cape Canaveral's Launch Complex 36B aboard an Atlas-Centaur rocket, marking the sixth successful soft-landing attempt in NASA's Surveyor program.[15] The spacecraft touched down on the lunar surface on November 10, 1967, at 01:01:04 UT in the Sinus Medii region, near the Moon's center as viewed from Earth, at approximate coordinates of 0.47°N latitude and 1.43°W longitude.[42] This central mare site provided an ideal location for broad-surface observations, building on prior missions' equatorial data. Following landing, Surveyor 6 transmitted over 30,000 high-resolution images during its primary operations, capturing detailed panoramas, close-ups of the regolith, and environmental surveys that offered the program's clearest views to date thanks to an improved camera mirror design ensuring clean optics.[15] On November 17, 1967—seven days after landing—the spacecraft executed the program's first lunar "hop" maneuver, firing its vernier engines for 2.5 seconds to lift approximately 3 meters vertically and translate 2.5 meters laterally westward, enabling stereo imaging from a new vantage point and demonstrating surface mobility potential.[42] This restart of the propulsion system after idle validated engine reliability in vacuum conditions.[15] The mission faced several operational challenges, including thermal switch failures that caused premature shutdowns by draining battery power during the lunar night and a helium leak detected nine days post-landing, which precluded additional engine firings.[15] Solar panels, while performing 4% above nominal output initially, required frequent manual adjustments to manage overvoltage tripping and maintain battery temperatures below critical thresholds, though no structural damage from landing was reported.[15] Operations continued through the first lunar day until sunset on November 24, 1967, with hibernation for the subsequent night; brief reactivation occurred on December 14, 1967, during the second lunar day for limited imaging before final loss of contact, spanning about 34 days on the surface across one full lunar night.[42]Surveyor 7

Surveyor 7, the final mission in the Surveyor program, launched on January 7, 1968, at 06:30 UTC from Cape Canaveral's Launch Complex 36A aboard an Atlas-Centaur rocket. After a three-day transit, the spacecraft executed a retro-rocket burn for descent, achieving a soft landing on January 10, 1968, at 01:05 UTC in the lunar highlands near Tycho crater. The landing site, at coordinates 40.97° S latitude and 11.44° W longitude, lay approximately 29 km north of the crater's rim on a rugged ejecta blanket characterized by rolling terrain, numerous rocks, and blocky debris. This location was selected to investigate non-mare geology, contrasting with prior missions in smoother basaltic plains.[43][1] Post-landing operations focused on imaging and in-situ analysis in this challenging highland environment. The television camera captured 21,038 photographs, including detailed views of ejecta blocks up to several meters across, ray patterns from secondary impacts, and the spacecraft's own hardware against a backdrop of fractured rocks and shallow craters. The surface sampler arm conducted soil mechanics experiments, such as bearing tests and trenching up to 20 cm deep, revealing cohesive fine-grained regolith overlying coarser, harder subsurface material; in one instance, the sampler strained against an immovable rock fragment at about 3 cm depth, highlighting the terrain's fragmented nature. Additionally, the arm manipulated small objects, including magnetic tests that attracted 1.2-cm soil particles.[1][43] A key highlight was the alpha-scattering instrument's chemical analysis of three samples: the undisturbed surface, a nearby anorthosite-like rock, and a trenched area. Positioned by the surface sampler, the instrument detected approximately 46.7 hours of data across these sites during the first lunar day, with an additional 34 hours on the third sample in the second lunar day. Results indicated low concentrations of iron-group elements (titanium through copper) at about 7% iron oxide—roughly half that of mare sites—alongside elevated aluminum (around 28%) and oxygen as the dominant element (>50%), consistent with highland anorthositic compositions. Silicon followed as the next most abundant, supporting distinctions in highland crustal materials from basaltic maria.[44][45] The mission encountered several anomalies tied to the site's ruggedness. The local terrain slope of about 3° resulted in the spacecraft tilting approximately 6° toward the Sun due to compression in the landing legs' shock absorbers, with footpads penetrating less than 6 cm into the thin regolith (estimated 2–15 cm thick). The alpha-scattering instrument initially failed to deploy fully owing to a nylon cord snag, requiring sampler assistance after 57 hours, which delayed analysis and contributed to elevated background noise from curium-242 recoil, limiting some spectral data quality in the early phases. Horizon irregularities up to 0.2° further complicated attitude determinations, though overall spacecraft stability allowed continued operations.[1] Surveyor 7 remained active for a total of 28 days across two lunar days, with power-on time exceeding 80 hours into the first lunar night and revival on February 12, 1968, for the second day until final contact at 00:24 UTC on February 21, 1968. These extended operations, despite instrument constraints, provided the first detailed data on highland geology, confirming thinner regolith, higher rock abundance (0.6% coverage by blocks >20 cm), elevated albedo (13.4%), and reduced heavy-element content compared to maria sites, informing models of lunar crustal differentiation.[43][1]Scientific Achievements

Surface Imaging and Mapping

The Surveyor program's imaging efforts produced over 87,000 photographs from its five successful missions, providing unprecedented close-range views of the lunar surface. These images, captured by television cameras mounted on the landers, enabled the creation of panoramic mosaics that collectively documented areas up to several square kilometers around each landing site, though detailed topographic coverage focused on regions within tens of meters of the spacecraft. The mosaics were assembled from sequences of overlapping frames taken at varying elevations and azimuths, offering 360-degree panoramas that extended from the horizon to the spacecraft's immediate vicinity. This visual dataset formed the foundation for early lunar cartography, revealing the Moon's regolith texture and micro-topography in far greater detail than prior telescopic observations.[39] Key findings from the imaging highlighted a rugged yet cohesive surface characterized by small-scale features. Wide-angle views captured craters as small as 2 centimeters in diameter alongside larger depressions up to 60 meters across, while rock fragments ranging from millimeters to over 100 meters were distributed with surface coverage of 4-18% for particles larger than 1 millimeter. Stereo pairs, generated by slight camera tilts or auxiliary mirrors, facilitated 3D topographic reconstructions with elevation accuracies of ±10 centimeters, delineating slopes up to 20 degrees and subtle undulations that indicated ongoing mass wasting in highland terrains. These observations underscored the lunar surface's homogeneity at shallow depths, with a thick layer of fine powder overlaying more consolidated material. The first close-up images also exposed the glassy, vesicular nature of regolith particles, suggesting impacts from meteoroids had melted and fused surface materials into agglutinates.[39] Imaging techniques relied on real-time transmission to Earth via radio telemetry, with the camera scanning frames at rates of 8 to 40 lines per second depending on resolution mode (200 or 600 lines per frame). Signals were relayed through the Deep Space Network and processed at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), where scan converters transformed the slow-scan vidicon output into standard television displays for immediate analysis. Post-mission enhancements at JPL included photometric corrections to account for lighting variations, enabling quantitative measurements of surface brightness.[46][39] Photometric analysis of the images determined the lunar surface's normal albedo to range from 0.07 to 0.12, with undisturbed mare regolith averaging 0.073-0.085 and disturbed areas appearing darker due to increased roughness scattering. Rocks exhibited higher albedos of 0.14-0.22, often with specular highlights from smooth facets. These values, derived from luminance profiles across phase angles of 20° to 90°, confirmed the surface's grayish tone and low reflectivity, influenced by sub-micron iron particles in the regolith. Polarization data from filtered images further revealed particle sizes predominantly under 10 microns, aiding models of light scattering on airless bodies.[47][39] The imaging contributions directly supported Apollo mission planning by mapping potential hazards such as boulder fields and steep slopes, which informed safe landing site selection in mare regions. For instance, stereo-derived topography identified navigable plains while flagging risks like 10-20 centimeter elevation changes that could destabilize descent engines. These visuals reduced uncertainties in surface traversability, validating the regolith's load-bearing capacity for human-rated landers and paving the way for subsequent manned exploration.[12][39]Soil Mechanics and Composition Analysis

The Soil Mechanics Surface Sampler (SMSS) on Surveyors 3 and 7 provided critical in situ measurements of lunar regolith's physical properties, revealing a fine-grained, cohesive material capable of supporting spacecraft loads while exhibiting low shear strength near the surface. Bearing strength varied with depth and mission site, ranging from less than 0.1 N/cm² in the uppermost millimeter to 0.2 N/cm² at 1–2 mm, increasing to 1.8 N/cm² at 1–2 cm, and reaching 4.2–5.6 N/cm² at approximately 4–5 cm, as measured by footpad imprints on successful missions and sampler bearing tests on Surveyor 3. Cohesion was estimated at 0.035–0.17 N/cm² (0.35–1.7 kPa), with Mohr-Coulomb modeling indicating values of 0.035–0.05 N/cm² (0.35–0.5 kPa) sufficient to maintain vertical trench walls up to 15–20 cm deep without collapse. The internal friction angle was consistently 35°–37°, derived from angle-of-repose observations in drainage features and inclined-plane simulations, reflecting the regolith's granular nature dominated by particles finer than 60 μm. Penetration depths during sampler operations and footpad contacts ranged from 5 cm in compacted layers to 25 cm in loose subsurface material, with Surveyor 3 achieving up to 15 cm and Surveyor 7 up to 20 cm in trenching tests. Bulk density was approximately 1.5 g/cm³ near the surface, increasing with depth due to compaction, as inferred from sampler dynamics and porosity estimates of around 50%.[39][48] The alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS) on Surveyors 5, 6, and 7 enabled the first in situ chemical analysis of lunar regolith, distinguishing compositional differences between basaltic maria and anorthositic highlands. In the maria sites of Surveyors 5 and 6 (Mare Tranquillitatis and Sinus Medii), atomic abundances indicated oxygen at 58 ± 5%, silicon at 18.5 ± 3%, aluminum at 6.5 ± 2%, and iron at 13 ± 3%, corresponding to oxide weight percentages of approximately 41% SiO₂, 14% Al₂O₃, 15–18% total iron (as Fe and FeO), and trace titanium at 5–7%. Highlands regolith at Surveyor 7 (Tycho ejecta) showed lower iron (7–10% total Fe) and higher aluminum (up to 25% Al₂O₃, consistent with anorthositic trends), with SiO₂ around 45% and reduced titanium (3–5%), highlighting a more felsic, plagioclase-rich composition compared to the iron-enriched basalts of the maria. These results, normalized to terrestrial basalt standards, confirmed the regolith's volcanic origins, with trace elements like titanium concentrated in ilmenite phases in mare soils.[39] Scoop and bearing tests using the SMSS simulated interactions relevant to Lunar Module (LM) descent, demonstrating the regolith's capacity to resist deep excavation under engine plume loads. On Surveyors 3 and 7, repeated scooping and trenching at angles up to 20° produced no craters exceeding 10 cm in depth, even under simulated dynamic loads equivalent to LM footpad pressures of 4–6 N/cm², as the soil's cohesion and friction prevented wholesale failure. Density measurements via reflectometry and sampler response corroborated the 1.5 g/cm³ value, supporting models of minimal blowout during controlled descent. These experiments validated the regolith's "fairy castle" structure—loose yet self-supporting—ensuring LM stability without significant surface disruption.[39][49] Derived soil failure models adapted the Mohr-Coulomb criterion for lunar conditions, expressing shear strength as , where is cohesion (0.35–0.5 kPa), is normal stress, and is the friction angle (35°–37°), accounting for reduced gravity ( m/s²) that lowers effective stress compared to terrestrial analogs. This framework, calibrated from Surveyor bearing and tilt tests, predicted stable footings for loads up to 6 N/cm² at depths beyond 6 cm, informing regolith behavior under low-gravity shear.[39][48]| Parameter | Maria (Surveyors 5, 6) | Highlands (Surveyor 7) |

|---|---|---|

| SiO₂ (wt%) | ~41% | ~45% |

| Al₂O₃ (wt%) | ~14% | ~25% |

| Total Fe (wt%) | 15–18% | 7–10% |

| Ti (wt%) | 5–7% | 3–5% |

.jpg/250px-Surveyor_diagram(English_captions).jpg)

.jpg)