Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Ferromagnetism

View on Wikipedia

| Condensed matter physics |

|---|

|

Ferromagnetism is a property of certain materials (such as iron) that results in a significant, observable magnetic permeability, and in many cases, a significant magnetic coercivity, allowing the material to form a permanent magnet. Ferromagnetic materials are noticeably attracted to a magnet, which is a consequence of their substantial magnetic permeability.

Magnetic permeability describes the induced magnetization of a material due to the presence of an external magnetic field. For example, this temporary magnetization inside a steel plate accounts for the plate's attraction to a magnet. Whether or not that steel plate then acquires permanent magnetization depends on both the strength of the applied field and on the coercivity of that particular piece of steel (which varies with the steel's chemical composition and any heat treatment it may have undergone).

In physics, multiple types of material magnetism have been distinguished. Ferromagnetism (along with the similar effect ferrimagnetism) is the strongest type and is responsible for the common phenomenon of everyday magnetism.[1] A common example of a permanent magnet is a refrigerator magnet.[2] Substances respond weakly to magnetic fields by three other types of magnetism—paramagnetism, diamagnetism, and antiferromagnetism—but the forces are usually so weak that they can be detected only by lab instruments.

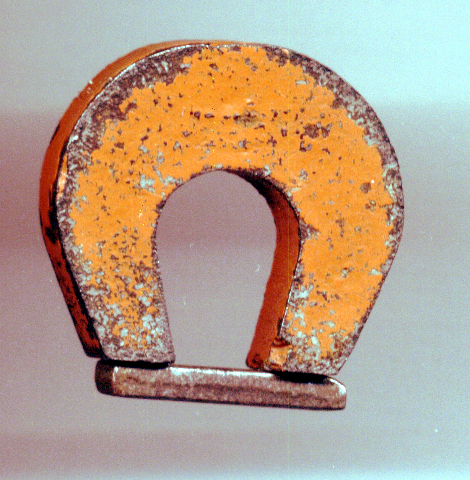

Permanent magnets (materials that can be magnetized by an external magnetic field and remain magnetized after the external field is removed) are either ferromagnetic or ferrimagnetic, as are the materials that are strongly attracted to them. Relatively few materials are ferromagnetic; the common ones are the metals iron, cobalt, nickel and most of their alloys, and certain rare-earth metals.

Ferromagnetism is widely used in industrial applications and modern technology, in electromagnetic and electromechanical devices such as electromagnets, electric motors, generators, transformers, magnetic storage (including tape recorders and hard disks), and nondestructive testing of ferrous materials.

Ferromagnetic materials can be divided into magnetically "soft" materials (like annealed iron) having low coercivity, which do not tend to stay magnetized, and magnetically "hard" materials having high coercivity, which do. Permanent magnets are made from hard ferromagnetic materials (such as alnico) and ferrimagnetic materials (such as ferrite) that are subjected to special processing in a strong magnetic field during manufacturing to align their internal microcrystalline structure, making them difficult to demagnetize. To demagnetize a saturated magnet, a magnetic field must be applied. The threshold at which demagnetization occurs depends on the coercivity of the material. The overall strength of a magnet is measured by its magnetic moment or, alternatively, its total magnetic flux. The local strength of magnetism in a material is measured by its magnetization.

Terms

[edit]Historically, the term ferromagnetism was used for any material that could exhibit spontaneous magnetization: a net magnetic moment in the absence of an external magnetic field; that is, any material that could become a magnet. This definition is still in common use.[3]

In a landmark paper in 1948, Louis Néel showed that two levels of magnetic alignment result in this behavior. One is ferromagnetism in the strict sense, where all the magnetic moments are aligned. The other is ferrimagnetism, where some magnetic moments point in the opposite direction but have a smaller contribution, so spontaneous magnetization is present.[4][5]: 28–29

In the special case where the opposing moments balance completely, the alignment is known as antiferromagnetism; antiferromagnets do not have a spontaneous magnetization.

Materials

[edit]| Material | Curie temp. (K) |

|---|---|

| Co | 1388 |

| Fe | 1043 |

| Fe2O3[a] | 948 |

| NiOFe2O3[a] | 858 |

| CuOFe2O3[a] | 728 |

| MgOFe2O3[a] | 713 |

| MnBi | 630 |

| Ni | 627 |

| Nd2Fe14 B | 593 |

| MnSb | 587 |

| MnOFe2O3[a] | 573 |

| Y3Fe5O12[a] | 560 |

| CrO2 | 386 |

| MnAs | 318 |

| Gd | 292 |

| Tb | 219 |

| Dy | 88 |

| EuO | 69 |

Ferromagnetism is an unusual property that occurs in only a few substances. The common ones are the transition metals iron, nickel, and cobalt, as well as their alloys and alloys of rare-earth metals. It is a property not just of the chemical make-up of a material, but of its crystalline structure and microstructure. Ferromagnetism results from these materials having many unpaired electrons in their d-block (in the case of iron and its relatives) or f-block (in the case of the rare-earth metals), a result of Hund's rule of maximum multiplicity. There are ferromagnetic metal alloys whose constituents are not themselves ferromagnetic, called Heusler alloys, named after Fritz Heusler. Conversely, there are non-magnetic alloys, such as types of stainless steel, composed almost exclusively of ferromagnetic metals.

Amorphous (non-crystalline) ferromagnetic metallic alloys can be made by very rapid quenching (cooling) of an alloy. These have the advantage that their properties are nearly isotropic (not aligned along a crystal axis); this results in low coercivity, low hysteresis loss, high permeability, and high electrical resistivity. One such typical material is a transition metal-metalloid alloy, made from about 80% transition metal (usually Fe, Co, or Ni) and a metalloid component (B, C, Si, P, or Al) that lowers the melting point.

A relatively new class of exceptionally strong ferromagnetic materials are the rare-earth magnets. They contain lanthanide elements that are known for their ability to carry large magnetic moments in well-localized f-orbitals.

The table lists a selection of ferromagnetic and ferrimagnetic compounds, along with their Curie temperature (TC), above which they cease to exhibit spontaneous magnetization.

Unusual materials

[edit]Most ferromagnetic materials are metals, since the conducting electrons are often responsible for mediating the ferromagnetic interactions. It is therefore a challenge to develop ferromagnetic insulators, especially multiferroic materials, which are both ferromagnetic and ferroelectric.[8]

A number of actinide compounds are ferromagnets at room temperature or exhibit ferromagnetism upon cooling. PuP is a paramagnet with cubic symmetry at room temperature, but which undergoes a structural transition into a tetragonal state with ferromagnetic order when cooled below its TC = 125 K. In its ferromagnetic state, PuP's easy axis is in the ⟨100⟩ direction.[9]

In NpFe2 the easy axis is ⟨111⟩.[10] Above TC ≈ 500 K, NpFe2 is also paramagnetic and cubic. Cooling below the Curie temperature produces a rhombohedral distortion wherein the rhombohedral angle changes from 60° (cubic phase) to 60.53°. An alternate description of this distortion is to consider the length c along the unique trigonal axis (after the distortion has begun) and a as the distance in the plane perpendicular to c. In the cubic phase this reduces to c/a = 1.00. Below the Curie temperature, the lattice acquires a distortion

which is the largest strain in any actinide compound.[11] NpNi2 undergoes a similar lattice distortion below TC = 32 K, with a strain of (43 ± 5) × 10−4.[11] NpCo2 is a ferrimagnet below 15 K.

In 2009, a team of MIT physicists demonstrated that a lithium gas cooled to less than one kelvin can exhibit ferromagnetism.[12] The team cooled fermionic lithium-6 to less than 150 nK (150 billionths of one kelvin) using infrared laser cooling. This demonstration is the first time that ferromagnetism has been demonstrated in a gas.

In rare circumstances, ferromagnetism can be observed in compounds consisting of only s-block and p-block elements, such as rubidium sesquioxide.[13]

In 2018, a team of University of Minnesota physicists demonstrated that body-centered tetragonal ruthenium exhibits ferromagnetism at room temperature.[14]

Electrically induced ferromagnetism

[edit]Recent research has shown evidence that ferromagnetism can be induced in some materials by an electric current or voltage. Antiferromagnetic LaMnO3 and SrCoO have been switched to be ferromagnetic by a current. In July 2020, scientists reported inducing ferromagnetism in the abundant diamagnetic material iron pyrite ("fool's gold") by an applied voltage.[15][16] In these experiments, the ferromagnetism was limited to a thin surface layer.

Explanation

[edit]The Bohr–Van Leeuwen theorem, discovered in the 1910s, showed that classical physics theories are unable to account for any form of material magnetism, including ferromagnetism; the explanation rather depends on the quantum mechanical description of atoms. Each of an atom's electrons has a magnetic moment according to its spin state, as described by quantum mechanics. The Pauli exclusion principle, also a consequence of quantum mechanics, restricts the occupancy of electrons' spin states in atomic orbitals, generally causing the magnetic moments from an atom's electrons to largely or completely cancel.[17] An atom will have a net magnetic moment when that cancellation is incomplete.

Origin of atomic magnetism

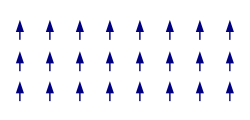

[edit]One of the fundamental properties of an electron (besides that it carries charge) is that it has a magnetic dipole moment, i.e., it behaves like a tiny magnet, producing a magnetic field. This dipole moment comes from a more fundamental property of the electron: its quantum mechanical spin. Due to its quantum nature, the spin of the electron can be in one of only two states, with the magnetic field either pointing "up" or "down" (for any choice of up and down). Electron spin in atoms is the main source of ferromagnetism, although there is also a contribution from the orbital angular momentum of the electron about the nucleus. When these magnetic dipoles in a piece of matter are aligned (point in the same direction), their individually tiny magnetic fields add together to create a much larger macroscopic field.

However, materials made of atoms with filled electron shells have a total dipole moment of zero: because the electrons all exist in pairs with opposite spin, every electron's magnetic moment is cancelled by the opposite moment of the second electron in the pair. Only atoms with partially filled shells (i.e., unpaired spins) can have a net magnetic moment, so ferromagnetism occurs only in materials with partially filled shells. Because of Hund's rules, the first few electrons in an otherwise unoccupied shell tend to have the same spin, thereby increasing the total dipole moment.

These unpaired dipoles (often called simply "spins", even though they also generally include orbital angular momentum) tend to align in parallel to an external magnetic field – leading to a macroscopic effect called paramagnetism. In ferromagnetism, however, the magnetic interaction between neighboring atoms' magnetic dipoles is strong enough that they align with each other regardless of any applied field, resulting in the spontaneous magnetization of so-called domains. This results in the large observed magnetic permeability of ferromagnetics, and the ability of magnetically hard materials to form permanent magnets.

Exchange interaction

[edit]When two nearby atoms have unpaired electrons, whether the electron spins are parallel or antiparallel affects whether the electrons can share the same orbit as a result of the quantum mechanical effect called the exchange interaction. This in turn affects the electron location and the Coulomb (electrostatic) interaction and thus the energy difference between these states.

The exchange interaction is related to the Pauli exclusion principle, which says that two electrons with the same spin cannot also be in the same spatial state (orbital). This is a consequence of the spin–statistics theorem and that electrons are fermions. Therefore, under certain conditions, when the orbitals of the unpaired outer valence electrons from adjacent atoms overlap, the distributions of their electric charge in space are farther apart when the electrons have parallel spins than when they have opposite spins. This reduces the electrostatic energy of the electrons when their spins are parallel compared to their energy when the spins are antiparallel, so the parallel-spin state is more stable. This difference in energy is called the exchange energy. In simple terms, the outer electrons of adjacent atoms, which repel each other, can move further apart by aligning their spins in parallel, so the spins of these electrons tend to line up.

This energy difference can be orders of magnitude larger than the energy differences associated with the magnetic dipole–dipole interaction due to dipole orientation,[18] which tends to align the dipoles antiparallel. In certain doped semiconductor oxides, RKKY interactions have been shown to bring about periodic longer-range magnetic interactions, a phenomenon of significance in the study of spintronic materials.[19]

The materials in which the exchange interaction is much stronger than the competing dipole–dipole interaction are frequently called magnetic materials. For instance, in iron (Fe) the exchange force is about 1,000 times stronger than the dipole interaction. Therefore, below the Curie temperature, virtually all of the dipoles in a ferromagnetic material will be aligned. In addition to ferromagnetism, the exchange interaction is also responsible for the other types of spontaneous ordering of atomic magnetic moments occurring in magnetic solids: antiferromagnetism and ferrimagnetism. There are different exchange interaction mechanisms which create the magnetism in different ferromagnetic,[20] ferrimagnetic, and antiferromagnetic substances—these mechanisms include direct exchange, RKKY exchange, double exchange, and superexchange.

Magnetic anisotropy

[edit]Although the exchange interaction keeps spins aligned, it does not align them in a particular direction. Without magnetic anisotropy, the spins in a magnet randomly change direction in response to thermal fluctuations, and the magnet is superparamagnetic. There are several kinds of magnetic anisotropy, the most common of which is magnetocrystalline anisotropy. This is a dependence of the energy on the direction of magnetization relative to the crystallographic lattice. Another common source of anisotropy, inverse magnetostriction, is induced by internal strains. Single-domain magnets also can have a shape anisotropy due to the magnetostatic effects of the particle shape. As the temperature of a magnet increases, the anisotropy tends to decrease, and there is often a blocking temperature at which a transition to superparamagnetism occurs.[21]

Magnetic domains

[edit]

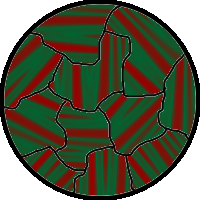

The spontaneous alignment of magnetic dipoles in ferromagnetic materials would seem to suggest that every piece of ferromagnetic material should have a strong magnetic field, since all the spins are aligned; yet iron and other ferromagnets are often found in an "unmagnetized" state. This is because a bulk piece of ferromagnetic material is divided into tiny regions called magnetic domains[22] (also known as Weiss domains). Within each domain, the spins are aligned, but if the bulk material is in its lowest energy configuration (i.e. "unmagnetized"), the spins of separate domains point in different directions and their magnetic fields cancel out, so the bulk material has no net large-scale magnetic field.

Ferromagnetic materials spontaneously divide into magnetic domains because the exchange interaction is a short-range force, so over long distances of many atoms, the tendency of the magnetic dipoles to reduce their energy by orienting in opposite directions wins out. If all the dipoles in a piece of ferromagnetic material are aligned parallel, it creates a large magnetic field extending into the space around it. This contains a lot of magnetostatic energy. The material can reduce this energy by splitting into many domains pointing in different directions, so the magnetic field is confined to small local fields in the material, reducing the volume of the field. The domains are separated by thin domain walls a number of molecules thick, in which the direction of magnetization of the dipoles rotates smoothly from one domain's direction to the other.

Magnetized materials

[edit]

Thus, a piece of iron in its lowest energy state ("unmagnetized") generally has little or no net magnetic field. However, the magnetic domains in a material are not fixed in place; they are simply regions where the spins of the electrons have aligned spontaneously due to their magnetic fields, and thus can be altered by an external magnetic field. If a strong-enough external magnetic field is applied to the material, the domain walls will move via a process in which the spins of the electrons in atoms near the wall in one domain turn under the influence of the external field to face in the same direction as the electrons in the other domain, thus reorienting the domains so more of the dipoles are aligned with the external field. The domains will remain aligned when the external field is removed, and sum to create a magnetic field of their own extending into the space around the material, thus creating a "permanent" magnet. The domains do not go back to their original minimum energy configuration when the field is removed because the domain walls tend to become 'pinned' or 'snagged' on defects in the crystal lattice, preserving their parallel orientation. This is shown by the Barkhausen effect: as the magnetizing field is changed, the material's magnetization changes in thousands of tiny discontinuous jumps as domain walls suddenly "snap" past defects.

This magnetization as a function of an external field is described by a hysteresis curve. Although this state of aligned domains found in a piece of magnetized ferromagnetic material is not a minimal-energy configuration, it is metastable, and can persist for long periods, as shown by samples of magnetite from the sea floor which have maintained their magnetization for millions of years.

Heating and then cooling (annealing) a magnetized material, subjecting it to vibration by hammering it, or applying a rapidly oscillating magnetic field from a degaussing coil tends to release the domain walls from their pinned state, and the domain boundaries tend to move back to a lower energy configuration with less external magnetic field, thus demagnetizing the material.

Commercial magnets are made of "hard" ferromagnetic or ferrimagnetic materials with very large magnetic anisotropy such as alnico and ferrites, which have a very strong tendency for the magnetization to be pointed along one axis of the crystal, the "easy axis". During manufacture the materials are subjected to various metallurgical processes in a powerful magnetic field, which aligns the crystal grains so their "easy" axes of magnetization all point in the same direction. Thus, the magnetization, and the resulting magnetic field, is "built in" to the crystal structure of the material, making it very difficult to demagnetize.

Curie temperature

[edit]As the temperature of a material increases, thermal motion, or entropy, competes with the ferromagnetic tendency for dipoles to align. When the temperature rises beyond a certain point, called the Curie temperature, there is a second-order phase transition and the system can no longer maintain a spontaneous magnetization, so its ability to be magnetized or attracted to a magnet disappears, although it still responds paramagnetically to an external field. Below that temperature, there is a spontaneous symmetry breaking and magnetic moments become aligned with their neighbors. The Curie temperature itself is a critical point, where the magnetic susceptibility is theoretically infinite and, although there is no net magnetization, domain-like spin correlations fluctuate at all length scales.

The study of ferromagnetic phase transitions, especially via the simplified Ising spin model, had an important impact on the development of statistical physics. There, it was first clearly shown that mean field theory approaches failed to predict the correct behavior at the critical point (which was found to fall under a universality class that includes many other systems, such as liquid-gas transitions), and had to be replaced by renormalization group theory.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Ferromagnetic material properties

- Hysteresis – Dependence of the state of a system on its history

- Orbital magnetization

- Stoner criterion – Condition for ferromagnetism

- Thermo-magnetic motor – Magnet motor

- Neodymium magnet – Strongest type of permanent magnet from an alloy of neodymium, iron and boron

References

[edit]- ^ Chikazumi, Sōshin (2009). Physics of ferromagnetism. English edition prepared with the assistance of C. D. Graham, Jr. (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-19-956481-1.

- ^ Bozorth, Richard M. Ferromagnetism, first published 1951, reprinted 1993 by IEEE Press, New York as a "Classic Reissue". ISBN 0-7803-1032-2.

- ^ Somasundaran, P., ed. (2006). Encyclopedia of surface and colloid science (2nd ed.). New York: Taylor & Francis. p. 3471. ISBN 978-0-8493-9608-3.

- ^ Cullity, B. D.; Graham, C. D. (2011). "6. Ferrimagnetism". Introduction to Magnetic Materials. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-21149-6.

- ^ Aharoni, Amikam (2000). Introduction to the theory of ferromagnetism (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850809-0.

- ^ Kittel, Charles (1986). Introduction to Solid State Physics (sixth ed.). John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-471-87474-4.

- ^ Jackson, Mike (2000). "Wherefore Gadolinium? Magnetism of the Rare Earths" (PDF). IRM Quarterly. 10 (3). Institute for Rock Magnetism: 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-07-12. Retrieved 2016-08-08.

- ^ Hill, Nicola A. (2000-07-01). "Why Are There so Few Magnetic Ferroelectrics?". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 104 (29): 6694–6709. doi:10.1021/jp000114x. ISSN 1520-6106.

- ^ Lander G. H.; Lam D. J. (1976). "Neutron diffraction study of PuP: The electronic ground state". Phys. Rev. B. 14 (9): 4064–4067. Bibcode:1976PhRvB..14.4064L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.14.4064.

- ^ Aldred A. T.; Dunlap B. D.; Lam D. J.; Lander G. H.; Mueller M. H.; Nowik I. (1975). "Magnetic properties of neptunium Laves phases: NpMn2, NpFe2, NpCo2, and NpNi2". Phys. Rev. B. 11 (1): 530–544. Bibcode:1975PhRvB..11..530A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.11.530.

- ^ a b Mueller M. H.; Lander G. H.; Hoff H. A.; Knott H. W.; Reddy J. F. (Apr 1979). "Lattice distortions measured in actinide ferromagnets PuP, NpFe2, and NpNi2" (PDF). J. Phys. Colloque C4, Supplement. 40 (4): C4-68–C4-69. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-05-09.

- ^ G.-B. Jo; Y.-R. Lee; J.-H. Choi; C. A. Christensen; T. H. Kim; J. H. Thywissen; D. E. Pritchard; W. Ketterle (2009). "Itinerant Ferromagnetism in a Fermi Gas of Ultracold Atoms". Science. 325 (5947): 1521–1524. arXiv:0907.2888. Bibcode:2009Sci...325.1521J. doi:10.1126/science.1177112. PMID 19762638. S2CID 13205213.

- ^ Attema, Jisk J.; de Wijs, Gilles A.; Blake, Graeme R.; de Groot, Robert A. (2005). "Anionogenic Ferromagnets" (PDF). Journal of the American Chemical Society. 127 (46). American Chemical Society (ACS): 16325–16328. Bibcode:2005JAChS.12716325A. doi:10.1021/ja0550834. ISSN 0002-7863. PMID 16287327.

- ^ Quarterman, P.; Sun, Congli; Garcia-Barriocanal, Javier; D. C., Mahendra; Lv, Yang; Manipatruni, Sasikanth; Nikonov, Dmitri E.; Young, Ian A.; Voyles, Paul M.; Wang, Jian-Ping (2018). "Demonstration of Ru as the 4th ferromagnetic element at room temperature". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 2058. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.2058Q. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-04512-1. PMC 5970227. PMID 29802304.

- ^ "'Fool's gold' may be valuable after all". phys.org. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ Walter, Jeff; Voigt, Bryan; Day-Roberts, Ezra; Heltemes, Kei; Fernandes, Rafael M.; Birol, Turan; Leighton, Chris (1 July 2020). "Voltage-induced ferromagnetism in a diamagnet". Science Advances. 6 (31) eabb7721. Bibcode:2020SciA....6.7721W. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abb7721. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 7439324. PMID 32832693.

- ^ Feynman, Richard P.; Robert Leighton; Matthew Sands (1963). The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Vol. 2. Addison-Wesley. pp. Ch. 37.

- ^ Chikazumi, Sōshin (2009). Physics of ferromagnetism. English edition prepared with the assistance of C. D. Graham, Jr. (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 129–130. ISBN 978-0-19-956481-1.

- ^ Assadi, M. H. N.; Hanaor, D. A. H. (2013). "Theoretical study on copper's energetics and magnetism in TiO2 polymorphs". Journal of Applied Physics. 113 (23): 233913-1 – 233913-5. arXiv:1304.1854. Bibcode:2013JAP...113w3913A. doi:10.1063/1.4811539. S2CID 94599250.

- ^ García, R. Martínez; Bilovol, V.; Ferrari, S.; de la Presa, P.; Marín, P.; Pagnola, M. (2022-04-01). "Structural and magnetic properties of a BaFe12O19/NiFe2O4 nanostructured composite depending on different particle size ratios". Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials. 547 168934. doi:10.1016/j.jmmm.2021.168934. ISSN 0304-8853. S2CID 245150523.

- ^ Aharoni, Amikam (1996). Introduction to the Theory of Ferromagnetism. Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-851791-2.

- ^

Feynman, Richard P.; Robert B. Leighton>; Matthew Sands (1963). The Feynman Lectures on Physics. Vol. I. Pasadena: California Inst. of Technology. pp. 37.5 – 37.6. ISBN 0-465-02493-9.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help)

External links

[edit] Media related to Ferromagnetism at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ferromagnetism at Wikimedia Commons- Electromagnetism – ch. 11, from an online textbook

- Sandeman, Karl (January 2008). "Ferromagnetic Materials". DoITPoMS. Dept. of Materials Sci. and Metallurgy, Univ. of Cambridge. Retrieved 2019-06-22. Detailed nonmathematical description of ferromagnetic materials with illustrations

- Magnetism: Models and Mechanisms in E. Pavarini, E. Koch, and U. Schollwöck: Emergent Phenomena in Correlated Matter, Jülich 2013, ISBN 978-3-89336-884-6

Ferromagnetism

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition and Key Properties

Ferromagnetism is a fundamental magnetic property observed in certain materials, characterized by the spontaneous alignment of atomic magnetic moments, resulting in a net magnetization without the need for an external magnetic field. This phenomenon occurs below a critical temperature known as the Curie temperature (), above which the material transitions to a paramagnetic state and loses its spontaneous magnetization. The ability to retain this magnetization after the removal of an external field distinguishes ferromagnets as permanent magnets.[5][6][7] Key properties of ferromagnetic materials include their high magnetic susceptibility, denoted as , which is positive () and typically orders of magnitude larger than in paramagnetic materials, leading to strong attraction to external fields. Another hallmark is the hysteresis in the magnetization curve, where the magnetization lags behind changes in the applied field, enabling energy storage and the creation of stable magnetic states. This hysteresis arises from the alignment of atomic magnetic moments within microscopic regions called domains, which collectively produce the macroscopic permanent magnetism.[8][9][10] In contrast to paramagnetism, where atomic moments align temporarily with an external field but randomize upon its removal (yielding small positive ), and diamagnetism, which induces a weak opposing magnetization (), ferromagnetism involves cooperative, persistent alignment. Antiferromagnetism features antiparallel alignment of moments with no net magnetization, while ferrimagnetism shows partial cancellation leading to a reduced net moment, both lacking the full spontaneous magnetization of ferromagnets. Everyday manifestations include refrigerator magnets that adhere to metallic surfaces and compass needles that align with Earth's magnetic field due to their ferromagnetic cores.[3][11][12][13]Historical Background

The phenomenon of ferromagnetism has roots in ancient observations of natural magnets. Around 600 BCE, the Greek philosopher Thales of Miletus noted that lodestone, a naturally occurring form of magnetite (Fe₃O₄), could attract iron fragments, marking one of the earliest recorded descriptions of magnetic attraction.[14] Similarly, ancient Chinese texts from the same era describe the use of lodestone for divination and early navigational compasses, demonstrating practical awareness of its directional properties.[15] Systematic study began in the Renaissance with William Gilbert's seminal 1600 treatise De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure, which distinguished magnetism from electricity and proposed that Earth itself acts as a giant magnet, explaining compass behavior through experimental investigations of lodestone and iron.[16] In the late 19th century, Pierre Curie advanced understanding in 1895 by discovering that ferromagnetic materials lose their strong magnetic properties above a critical temperature, transitioning to paramagnetic behavior, a finding derived from precise measurements of magnetic susceptibility under varying temperatures.[17] Building on this, Pierre Weiss proposed in 1907 the molecular field theory, positing that atomic magnetic moments in ferromagnets align due to an internal "molecular field" from neighboring atoms, which also introduced the concept of magnetic domains to explain saturation and hysteresis.[18] The 20th century brought quantum mechanical explanations, with Werner Heisenberg's 1928 theory attributing ferromagnetism to quantum exchange interactions between electron spins, where the Pauli exclusion principle favors parallel alignments in certain electron configurations, resolving the classical puzzle of spontaneous magnetization.[19] This laid the groundwork for further developments in the 1930s, including Felix Bloch's calculations of spin-wave excitations (magnons) describing low-temperature magnetization reductions and Edmund Stoner's band theory linking ferromagnetism to electron density of states at the Fermi level in metals.[20] Post-1950s experimental confirmations solidified these ideas, as advanced microscopy techniques directly visualized magnetic domain walls and structures, validating Weiss's domain hypothesis through observations of stripe and closure domains.[21] More recently, the 2017 discovery of intrinsic ferromagnetism in monolayer CrI₃, a van der Waals material, extended these concepts to two dimensions, revealing layer-dependent Curie temperatures up to 45 K via magneto-optical Kerr effect measurements.[22] Subsequent research has identified additional 2D ferromagnets with higher Curie temperatures approaching room temperature, such as CrGaS₃ (theoretically 520–814 K) and ferromagnetic semiconductors achieving 530 K experimentally as of 2025.[23][24] Studies of ferromagnetism profoundly influenced 19th-century technology, particularly through integrations with electromagnetism that enabled practical electric motors; Michael Faraday's 1821 demonstration of continuous rotation via electromagnetic torque, building on Oersted's 1820 linkage of current and magnetism, paved the way for devices like the 1830s prototypes by Joseph Henry and Thomas Davenport.[25]Ferromagnetic Materials

Traditional Materials

Traditional ferromagnetic materials primarily consist of elemental metals, alloys, and certain oxide compounds that exhibit strong, spontaneous magnetization below their respective Curie temperatures. These materials form the foundation of magnetic technologies due to their well-characterized properties and ease of production.[26] Among the elemental ferromagnets, iron (Fe), nickel (Ni), and cobalt (Co) are the most prominent. Iron has a Curie temperature of 1043 K and a saturation magnetization of 2.15 T, making it suitable for applications requiring high magnetic flux density.[27] Nickel exhibits a lower Curie temperature of 627 K and saturation magnetization of 0.64 T, while cobalt displays the highest Curie temperature at 1388 K with a saturation magnetization of 1.79 T.[27] These elements generally possess low coercivities, typically below 0.1 kA/m for pure bulk forms, which facilitates easy magnetization but limits their use in permanent magnets without alloying.[28] Alloys such as permalloys (typically 80% Ni-20% Fe) enhance soft magnetic properties with relative permeabilities exceeding 100,000 and saturation magnetizations around 0.8 T, alongside very low coercivities of about 0.008 kA/m.[29] Their Curie temperature is approximately 853 K.[30] Alnico alloys (Al-Ni-Co, e.g., Alnico 5 with ~8% Al, 14% Ni, 24% Co, balance Fe) are cast permanent magnets with Curie temperatures of 810–860°C (1083–1133 K), saturation magnetizations near 1.25 T, and coercivities of 50–720 Oe (4–57 kA/m), offering high temperature stability for demanding environments.[31][32] Compounds like magnetite (Fe₃O₄), a naturally occurring mineral, demonstrate ferromagnetic behavior with a Curie temperature of 853 K (580°C) and saturation magnetization of approximately 0.60 T, though it technically exhibits ferrimagnetism due to antiparallel sublattice alignments.[33][9] Its low coercivity and abundance make it historically significant in geological magnetism studies. Neodymium-iron-boron (Nd₂Fe₁₄B) represents a high-performance permanent magnet compound with a Curie temperature of 585 K (312°C), saturation magnetization of 1.60 T, and high coercivities up to 1500 kA/m, enabling compact, strong magnets.[34] These materials are prepared through smelting of ores in blast furnaces for elements like iron and subsequent alloying via melting in induction furnaces under controlled atmospheres to achieve desired compositions.[35] Common applications include permalloys and iron-based alloys in transformer cores for efficient energy transfer, alnico and Nd₂Fe₁₄B in electric motors for torque generation, and Nd₂Fe₁₄B in hard disk drives for data storage.[36][37]| Material | Curie Temperature (K) | Saturation Magnetization (T) | Coercivity (kA/m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iron (Fe) | 1043 | 2.15 | ~0.08 |

| Nickel (Ni) | 627 | 0.64 | ~0.02–1.8 |

| Cobalt (Co) | 1388 | 1.79 | ~0.06–5.7 |

| Permalloy (80Ni-20Fe) | 853 | 0.80 | ~0.008 |

| Alnico 5 | 1083–1133 | 1.25 | 4–57 |

| Magnetite (Fe₃O₄) | 853 | 0.60 | Low (<1) |

| Nd₂Fe₁₄B | 585 | 1.60 | Up to 1500 |