Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Solid South

View on WikipediaThis article possibly contains original research. (April 2025) |

Key Information

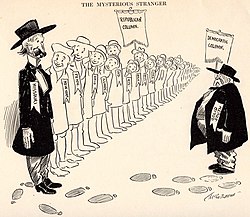

The Solid South was the electoral voting bloc for the Democratic Party in the Southern United States between the end of the Reconstruction era in 1877 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[1][2] In the aftermath of the Compromise of 1877 and the failure of the Lodge Bill of 1890, Southern Democrats disenfranchised nearly all blacks in all the former states of the Confederate States of America during the late 19th century and the early 20th century.[3]

During this period, the Democratic Party controlled southern state legislatures and most local, state and federal officeholders in the South were Democrats. This resulted in a one-party system, in which a candidate's victory in Democratic primary elections was tantamount to election to the office itself. White primaries were another means that the Democrats used to consolidate their political power, excluding blacks from voting.[4]

The "Solid South" included all 11 former Confederate states: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia. It also included to a lesser extent Kentucky and Oklahoma,[a] which remained electorally competitive during the Jim Crow era.[5] The Border states of Delaware, Maryland, and West Virginia were rarely identified with the Solid South after the 1896 United States presidential election, while Missouri became a bellwether state after the 1904 United States presidential election.[6] The Solid South only began to fall after World War II, and ended in the 1960s as a result of the Civil rights movement.[7]

The Solid South can also refer to the "Southern strategy" that has been employed by Republicans since the 1960s to increase their electoral power in the South. Republicans have been the dominant party in most political offices within the South since 2010.[8] The main exception to this trend has been the state of Virginia.[9]

Background

[edit]

At the start of the American Civil War, there were 34 states in the United States, 15 of which were slave states. Slavery was also legal in the District of Columbia until 1862. Eleven of these slave states seceded from the United States to form the Confederacy: South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina.[11]

The southern slave states that stayed in the Union were Maryland, Missouri,[c] Delaware, and Kentucky, and they were referred to as the border states. Kentucky and Missouri both had dual competing Confederate governments, the Confederate government of Kentucky and the Confederate government of Missouri. The Confederacy controlled more than half of Kentucky and the southern portion of Missouri early in the war but largely lost control in both states after 1862.[13] West Virginia, created in 1863 from Unionist and Confederate counties of Virginia, was represented in both Union and Confederate legislatures, and was the only border state to have civilian voting in the 1863 Confederate States House of Representatives elections.[14][15]

By the time the Emancipation Proclamation was made in 1863, Tennessee was already under Union control. Accordingly, the Proclamation applied only to the 10 remaining Confederate states. Some of the border states abolished slavery before the end of the Civil War—Maryland in 1864,[16] Missouri in 1865,[17] one of the Confederate states, Tennessee in 1865,[18] West Virginia in 1865,[19] and the District of Columbia in 1862. However, slavery persisted in Delaware,[20] Kentucky,[21] and 10 of the 11 former Confederate states, until the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution abolished slavery throughout the United States on December 18, 1865.[22]

Democratic dominance of the South originated in the struggle of white Southerners during and after Reconstruction (1865–1877) to reestablish white supremacy and disenfranchise black people. The federal government of the United States under the Republican Party had defeated the Confederacy, abolished slavery, and enfranchised black people. In several states, Black voters were a majority or close to it. Republicans supported by black people controlled state governments in these states. Thus the Democratic Party became the vehicle for the white supremacist Redeemers.[23] The Ku Klux Klan, as well as other insurgent paramilitary groups such as the White League and Red Shirts from 1874, acted as "the military arm of the Democratic party" to disrupt Republican organizing, and to engage in voter intimidation and voter suppresion of black voters.[24]

Redemption

[edit]

The end of Reconstruction and the creation of the Solid South was caused by the Southern Democratic Redeemers, and enabled by some Republicans.[23] Joseph P. Bradley was a Supreme Court associate justice from 1870 to 1892, and was a Republican appointed by Republican president Ulysses S. Grant. Bradley was a key enabler of the creation of the Solid South, both as a judge and in his tie-breaking role in the 15-member Electoral Commission that decided the disputed 1876 presidential election.[25]

The 1872 Louisiana gubernatorial election was won by Republican William Pitt Kellogg. The Colfax massacre occurred on April 13, 1873, in Colfax, Louisiana. An estimated 62–153 Black men were murdered while surrendering to a mob of former Confederate soldiers and members of the Ku Klux Klan. Three White men also died during the confrontation.[25] In 1874, the Battle of Liberty Place occurred in which the White League attempted to overthrow Kellogg's Republican government in New Orleans, Louisiana,[26] which was suppressed by federal troops sent by Republican president Ulysses S. Grant.[27]

It was due to Bradley's intervention that prisoners charged in the Colfax Massacre of 1873 were freed, after he happened to attend their trial and ruled that the federal law they were charged under was unconstitutional. This resulted in the federal government's bringing the case on appeal to the Supreme Court as United States v. Cruikshank (1875). The court's ruling was that because the massacre was not a state action, the federal government would not intervene on paramilitary and group attacks on individuals. It essentially opened the door to heightened paramilitary activity in the South that forced Republicans from office, suppressed black voting, and opened the way for white Democratic takeover of state legislatures.[25]

The Mississippi Plan of 1874–1875 was developed by white Southern Democrats to reverse Republican strength in Mississippi, particularly to remove Republican governor Adelbert Ames. White paramilitary organizations such as the Red Shirts arose to serve as "the military arm of the Democratic Party." The first step was to persuade scalawags (white Republicans) to vote with the Democratic party, with outright attacks and political pressure convincing many scalawags to switch parties or flee the state. The second step of the Mississippi Plan was intimidation of African American voters, with the Red Shirts often using violence, including whippings and murders, and intimidation at the polls. The Red Shirts were joined in the violence by white paramilitary groups known as "rifle clubs," who frequently provoked riots at Republican rallies, shooting down dozens of blacks in the ensuing conflicts.[28] Ultimately, Adelbert Ames was unable to organize a state militia and signed a peace treaty with Democratic leaders. In return for disarming the few militia units he had assembled, they promised to guarantee a full, free, fair election, a promise they did not keep. In November 1875, Democrats terrorized a large part of the Republican vote into staying home, driving voters from the polls with shotguns and cannons, and gaining firm control of both houses of the Mississippi legislature. The state legislature, convening in 1876, drew up articles of impeachment against Ames. Rather than face an impeachment trial, Ames's lawyers made a deal: once the legislature had dropped all charges, he would resign his office, which occurred on March 29, 1876.[23]

Compromise of 1877

[edit]

Republican Daniel Henry Chamberlain was born in Massachusetts and had served as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army with the 5th Massachusetts Colored Volunteer Cavalry, a regiment of Black troops. Chamberlain was elected Governor of South Carolina in 1874 and sought re-election in 1876.[29] Both Republicans, Bradley and Chamberlain, played crucial roles on opposing sides of the creation of the Solid South. Bradley gave Republican Rutherford B. Hayes the presidency in the 1876 presidential election, which in turn caused Chamberlain to lose the South Carolina governorship as part of the Compromise of 1877.[30]

In the aftermath of the Panic of 1873, poor economic conditions caused voters to turn against the Republican Party. In the 1874 congressional elections, the Democratic Party assumed control of the U.S. House of Representatives for the first time since the Civil War. Public opinion in the North began to steer away from Reconstruction. With the depression, ambitious railroad building programs crashed across the South, leaving most Southern states deep in debt and burdened with heavy taxes. Most Southern states fell to Democratic control in the South, as the Republican Party lost electoral power in the South.[31]

Democrat Samuel J. Tilden was elected governor of New York in 1874, and had supported the Union during the American Civil War. Republican Rutherford B. Hayes had served in the Union army as an officer, served in Congress from 1865 to 1867, and served as governor of Ohio from 1868 to 1872 and 1876 to 1877 before his swearing-in as president. The 1876 presidential election was extremely controversial, as Hayes lost the popular vote to Tilden 47.9%–50.9%, but ultimately won the Electoral College 185-184. Hayes won three former Confederate states, all by extremely narrow margins: South Carolina, Florida, and Louisiana. Yet all three states were concurrently won by Democratic gubernatorial nominees by narrow margins as well.[30]

The concurrent 1876 South Carolina gubernatorial election in particular was extremely close, and rife with violence and likely electoral fraud. Chamberlain ran against Democrat Wade Hampton III, who was a Lieutenant General in the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia during the Civil War, and a leader of the Redeemers. Hampton's campaign for governor was marked by extensive violence by the Red Shirts, who intimidated and suppressed Black voters in the state in the same way as the Mississippi Plan of 1874–1875.[32] Immediately after the 1876 South Carolina gubernatorial results were announced, both the Republican and Democratic parties accused each other of fraud. Hampton received 92,261 votes to Chamberlain's 91,127, that is 50.3% to 49.7%. However, the State Board of Canvassers, which was composed of five Republicans, declared that the elections in Edgefield County and Laurens County were so tainted by fraud that their results would be excluded from the final tally. This changed the Republican tally from a 1,134-vote loss to a 3,145-vote victory.[33]

To summarize, Republican Rutherford B. Hayes was ultimately elected president by winning the Electoral College 185-184, despite losing the popular vote 47.9-50.9%. The tipping-point state was South Carolina, which Hayes had won 91,786 to 90,897 (50.24% to 49.76%), for South Carolina's 7 electoral votes. And Democrat Wade Hampton III was elected governor of South Carolina, on the same ballot, 92,261 to 91,127 (50.3% to 49.7%). This was in a state whose elections had been conducted in an atmosphere of widespread violence and fraud, and led to the disputed government of South Carolina of 1876–77. In 2001, Ronald F. King used modern statistical techniques on the election returns and concluded: "Application of social science methodology to the gubernatorial election of 1876 in South Carolina confirms charges of fraud raised by Republicans at the time of the election.... [the result] was the product of massive voter fraud and intimidation of black voters."[34]

From December 1876 to April 1877, the Republican and Democratic parties in South Carolina each claimed to be the legitimate government, declaring that they controlled the governorship and state legislature. Each government debated and passed laws, raised militias, collected taxes, and conducted other business as if the other did not exist.[35] And not only were the presidential and gubernatorial elections in South Carolina disputed, but they were also disputed in Louisiana and Florida, causing similar dual government disputes in those two states. In Louisiana, Democrat Francis T. Nicholls had defeated Stephen B. Packard 84,487 to 76,477 (52.49% to 47.51%) in the 1876 Louisiana gubernatorial election, yet Republican Rutherford B. Hayes had defeated Democrat Samuel J. Tilden in Louisiana 75,315 to 70,508 (51.65% to 48.35%) on the same ballot. And in Florida, Republican Rutherford B. Hayes had defeated Democrat Samuel J. Tilden 23,849 to 22,927 (50.99% to 49.01%), yet on the same ballot Democrat George F. Drew defeated Republican Marcellus L. Stearns 24,613 to 24,116 (50.51% to 49.49%) in the 1876 Florida gubernatorial election. Most importantly, the 1876 presidential election was also disputed with Tilden having 184 electoral votes, Hayes having 165 electoral votes, and the 20 disputed electoral votes all needing to go to Hayes to give him a majority of 185 out of 369 electoral votes.[30]

To resolve the 1876 presidential election, an "Electoral Commission" was created, consisting of fifteen members: five representatives selected by the House, five senators selected by the Senate, four Supreme Court justices named in the law, and a fifth Supreme Court justice selected by the other four. Originally, it was planned that the commission would consist of seven Democrats and seven Republicans, with an independent (Justice David Davis) as the fifteenth member of the commission. According to historian Roy Morris Jr., "no one, perhaps not even Davis himself, knew which presidential candidate he preferred." Just as the Electoral Commission Bill was passing Congress, Davis was elected to the Senate by Democrats in the Illinois legislature, who believed that they had purchased Davis' support for Tilden, but this was a miscalculation: Davis promptly excused himself from the commission and resigned as a Justice in order to take his Senate seat. Because of this, Davis was unable to assume the spot, always intended for him, as one of the Supreme Court's members of the Commission. His replacement on the Commission was Republican Supreme Court Justice Joseph P. Bradley, resulting in an 8–7 majority for Republicans, which in turn awarded Hayes the 20 disputed electoral votes on party-line votes, and thus Hayes had won the presidency by an electoral vote of 185–184 despite losing the popular vote 47.9% to 50.9%.[30]

Hayes was peacefully sworn in as president privately on Saturday, March 3, 1877 and publicly on Monday March 5, 1877. On March 31, Hampton and Chamberlain met with President Hayes to discuss the situation in South Carolina. On April 3, Hayes ordered the withdrawal of federal troops from South Carolina, which they did on April 10. Chamberlain, realizing that he could not continue in his role without the support of federal troops, resigned on April 11, 1877.[36] Embittered, Chamberlain blamed the President for having betrayed the mass of South Carolina's voters; the state's population was 58% African American. After conceding the governorship to Hampton, Chamberlain stated, "If a majority of people in a State are unable by physical force to maintain their rights, they must be left to political servitude." After Chamberlain's concession, Hampton was declared the sole governor of South Carolina.[33] Chamberlain left the state and moved to New York City, and became a successful Wall Street attorney. South Carolina would not elect another Republican governor until 1974, 100 years after Chamberlain was elected in 1874.[35] Hampton was later elected to the U.S. Senate by the South Carolina legislature for two terms, from 1879 to 1891.[32]

This series of events is referred to as the Compromise of 1877, a corrupt bargain by which Republican Rutherford B. Hayes was elected president despite losing the popular vote while Southern Democrats were given state-level power in the former Confederate states despite having committed violence and electoral fraud against African Americans. The loser of the Compromise of 1877 were African Americans, as Republicans allowed Southern Democrats to create hegemony in the former Confederate states, depriving African Americans of the protection of federal troops and the ability to elect Republican candidates in statewide and congressional races.[30] Republicans never won a single Deep South state again until they won Louisiana in 1956, and Republican Barry Goldwater won all the Deep South states in 1964. This was despite the fact that African Americans constituted a majority or near-majority of the populations of the Deep South states, at least until the Great Migration.[7]

Failure of the 1890 Lodge Bill

[edit]

Republican Henry Cabot Lodge was an American politician and statesman from Massachusetts, who served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1887 to 1893, and in United States Senate from 1893 to 1924.[citation needed] In 1890, Lodge co-authored the Federal Elections Bill, along with Senator George Frisbie Hoar of Massachusetts, that guaranteed federal protection for African American voting rights. Although the proposed legislation was supported by President Benjamin Harrison, the bill was blocked due to the efforts of filibustering Democrats[37] and Republican William M. Stewart of Nevada in the Senate.

Republican William M. Stewart described how he helped defeat the Lodge Bill in his own memoir, published in 1908. Stewart worked with other Democrats, including Arthur Pue Gorman of Maryland, to defeat the Lodge Bill.[citation needed]

Democrat Grover Cleveland was elected governor of New York in 1882, and was elected President in 1884, becoming the first Democratic President after the Civil War.

During the late 19th century, the state of New York was a swing state in presidential elections. Cleveland won the popular vote in all three of his presidential elections, but these were suspect due to the disenfranchisement of African Americans who mostly favored Harrison in the South, as was noted by Republican politicians at the time and by modern scholars. In particular, Republican Benjamin Harrison won Cleveland's home state of New York in 1888, which single-handedly cost Cleveland the 1888 presidential election given New York had 36 electoral votes.[38][39][40]

Also, the former Confederate state of Virginia was competitive in the first two of Cleveland's three elections. Cleveland won Virginia in 1884 by 2.15% and Virginia in 1888 by just 0.53%, but won Virginia in 1892 by 17.46%.

In 1892, Cleveland had campaigned against the Lodge Bill,[41] which would have strengthened voting rights protections through the appointing of federal supervisors of congressional elections upon a petition from the citizens of any district. The Enforcement Act of 1871 had provided for a detailed federal overseeing of the electoral process, from registration to the certification of returns. Cleveland succeeded in ushering in the 1894 repeal of this law.[42]

Final failures

[edit]The failure of the Lodge Bill led to unsuccessful attempts to have the federal courts protect voting rights in Williams v. Mississippi (1898) and Giles v. Harris (1903). These cases were a few years after Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which had upheld "separate but equal" racial segregation laws.[citation needed]

Ultimately, national Republicans gave up on voting rights for African Americans and winning the eleven former Confederate states, both because of opposition from Southern Democrats and the fact they did not need them to win presidential elections and majorities in Congress. In the 1896 presidential election, Republican William McKinley won the popular vote 51.0% to 46.7% and the Electoral College 271-176. McKinley did win the border states Delaware, Maryland, West Virginia, and Kentucky (except for 1 electoral vote in the latter), but lost all the 11 former Confederate states. Republicans did not win even a single former Confederate state from 1880 until they won Tennessee in the 1920 presidential election, though they may have been able to had the Lodge Bill passed.[43]

When a group of white supremacists violently overthrew the duly elected government of Wilmington, North Carolina, on November 10, 1898, in an event that came to be recognized as the Wilmington massacre of 1898, Republican President William McKinley refused requests by Black leaders to send in federal marshals or federal troops to protect black citizens,[44] and ignored city residents' appeals for help to recover from the widespread destruction of the predominantly black neighborhood of Brooklyn, the majority-black neighborhood in Wilmington.[45] This was despite the fact that McKinley was the last president to have served in the American Civil War; he was the only one to begin his service as an enlisted man and ended it as a brevet major. McKinley had voted for the Lodge Bill, and was defeated in the 1890 U.S. House elections as a representative from Ohio.[citation needed]

In 1900, as the 56th Congress considered proposals for apportioning its seats among the 45 states following the 1900 Federal Census, Representative Edgar D. Crumpacker (R-IN) filed an independent report urging that the Southern states be stripped of seats due to the large numbers of voters they had disfranchised. He noted this was provided for in Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment, which provided for stripping representation from states that reduced suffrage due to race. From 1896 until 1900, the House of Representatives with a Republican majority had acted in more than thirty cases to set aside election results from Southern states where the House Elections Committee had concluded that "[B]lack voters had been excluded due to fraud, violence, or intimidation".[46] However, in the early 1900s, it began to back off, after Democrats won a majority, which included Southern delegations that were solidly in Democratic hands. However, concerted opposition by the Southern Democratic bloc was aroused, and the effort failed.[47]

Scale of the disfranchisement

[edit]

Some Northern Congressmen continued to raise the issue of Black disfranchisement and resulting malapportionment. For instance, on December 6, 1920, Representative George H. Tinkham (R-MA) offered a resolution for the Committee of Census to investigate the alleged disfranchisement of African Americans.[48] Tinkham argued there should be reapportionment in the House related to the voting population of southern states, rather than the general population as enumerated in the census. Such reapportionment was authorized by the Constitution, and would reflect reality so that the South should not get representation for voters it had disfranchised.[48]

Tinkham detailed how outsized the South's representation was related to the total number of voters in the former Confederate states in the 1918 U.S. House elections, compared to other states with the same number of representatives, as shown in the following table:[48]

| State | Number of Representatives | Total Vote | Former Confederate state? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Florida | 4 | 31,613 | Yes |

| Colorado | 4 | 208,855 | No |

| Maine | 4 | 121,836 | No |

| Nebraska | 6 | 216,014 | No |

| West Virginia | 6 | 211,643 | No |

| South Carolina | 7 | 25,433 | Yes |

| Louisiana | 8 | 44,794 | Yes |

| Kansas | 8 | 425,641 | No |

| Alabama | 10 | 62,345 | Yes |

| Minnesota | 10 | 299,127 | No |

| Iowa | 10 | 316,377 | No |

| California | 11 | 644,790 | No |

| Georgia | 12 | 59,196 | Yes |

| New Jersey | 12 | 338,461 | No |

| Indiana | 13 | 565,216 | No |

Tinkham was defeated by the Democratic Southern Bloc, and also by fears amongst the northern business elites of increasing the voting power of Northern urban working classes,[49] whom both northern business and Southern planter elites believed would vote for large-scale income redistribution at a Federal level.[50]

History

[edit]Redeemers

[edit]

By 1876, "Redeemer" Democrats had taken control of all state governments in the South. From then until the 1960s, state and local government in the South was almost entirely monopolized by Democrats. The Democrats elected all but a handful of U.S. Representatives and Senators, and Democratic presidential candidates regularly swept the region – from 1880 through 1944, winning a cumulative total of 182 of 187 states. The Democrats reinforced the loyalty of white voters by emphasizing the suffering of the South during the war at the hands of "Yankee invaders" under Republican leadership, and the noble service of their white forefathers in "the Lost Cause". This rhetoric was effective with many Southerners. However, this propaganda was totally ineffective in areas that had been loyal to the Union during the war, such as East Tennessee. Most of East Tennessee welcomed U.S. troops as liberators, and voted Republican even in the Solid South period.[51]

Despite White Southerners' complaints about Reconstruction, several Southern states kept most provisions of their Reconstruction constitutions for more than two decades, until late in the 19th century.[52] Disfranchisement of African Americans was a gradual and sometimes haphazard process, and began first in the Deep South states that had the largest African American populations.[53] In Georgia, a poll tax was first imposed in 1877. In South Carolina, an indirect literacy test and multiple-ballot box law, called the "Eight Box Law," was enacted in 1882.[54]

Even after white Democrats regained control of state legislatures, some black candidates were elected to local offices and state legislatures in the South. Black U.S. Representatives were elected from the South as late as the 1890s, usually from overwhelmingly black areas. Intimidation of African American voters and outright electoral fraud were common, before widespread disfranchisement began after the failure of the Lodge Bill of 1890.[55]

Third parties

[edit]In Virginia, the bi-racial Readjuster Party existed from 1877 to 1895, electing William E. Cameron in 1881 as the 39th Governor of Virginia from 1882 to 1886.[56] William Mahone served as a U.S. Senator from Virginia from 1881 to 1887 as a member of the Readjuster Party.[57] Democratic president Grover Cleveland narrowly won Virginia in 1884 51.05% to 48.90%, and won Virginia in 1888 by just 49.99% to 49.46%, a 0.53 percentage point margin and the closest the Republican Party came to winning a former Confederate state until Warren G. Harding won Tennessee in 1920.[58]

In Arkansas, the 1888 and 1890 gubernatorial elections were competitive, with Democrat James Philip Eagle winning only 54.09% to 45.91% and 55.51% to 44.49%, respectively. Eagle ran against a fusion ticket of the Union Labor and Republican parties, with the Republican party endorsing the Union Labor party candidates.[59] Wealthy white landowners were extremely angry that poor blacks and whites might be uniting against them. In 1891, the Arkansas Democratic Party thus introduced a poll tax that would weigh extremely heavily upon poor Union Labor supporters and also introduced the secret ballot which would make it more difficult for illiterate blacks and poor whites to cast a vote even if they could pay the poll tax.[60]

Populist Party

[edit]

The People's Party, usually known as the Populist Party or simply the Populists, was an agrarian populist party political party that was founded in 1892.[61] The Populists developed a following in the South, among poor white people who resented the Democratic Party establishment. Populists formed alliances with Republicans (including black Republicans) and challenged the Democratic bosses. In some cases, the Populists and their allies defeated their Democratic opponents.[43]

Unfortunately, the success of the Populist Party was a major impetus for even more thorough disfranchisement. The Populist Party was dissolved in 1909, by which point disfranchisement of African Americans was virtually complete. The Populist Party did win some U.S. House seats in the former Confederate states, including Thomas E. Watson of Georgia (1891–1893) and several representatives in North Carolina.[62] The Populists also elected North Carolina U.S. Senator Marion Butler (1895–1901).[63]

In North Carolina, Republican Daniel Lindsay Russell was elected Governor of North Carolina in 1896 on a fusionist ticket, a collaboration between Republicans and Populists, and served as the 49th governor of North Carolina from 1897 to 1901.[64] On November 8, 1898, a part-black fusion slate won elections in Wilmington, then the state's largest city and with a black majority. Alfred Waddell, whom Russell had defeated for Congress in 1878, led thousands of white rioters in the Wilmington Insurrection of 1898; they seized the city government by force, and destroyed the only black-owned newspaper in the state.[65] Although Russell was not up for election in 1898, Democrats used him as a foil in their campaign that year, attacking him for undermining "white supremacy" and fanning fears of "negro rule" to regain control of the state legislature.[66] To prevent fusionist coalitions or Republicans winning office again, in 1899 the Democrats used their control of the North Carolina legislature to pass an amendment that effectively disenfranchised blacks and many poor whites. As a result, voter rolls dropped dramatically, blacks were excluded from the political system, and the Republican Party was crippled in the state.[67]

In Alabama, Reuben Kolb sought to unite poor farmers and sharecroppers with industrial workers and Black voters as a Populist in 1892 and 1894. The gubernatorial elections he lost in 1892 and 1894 are considered to have had widespread vote tampering and fraud.[68][69] In 1894, Kolb retreated from his brief flirtation with the idea of Black rights, "a telling reflection of the shallow commitment of Kolb and many of his followers to the notion of racial equality." And, after the Populist party's electoral failure in 1896, "Kolb confessed his apostasy and pathetically pleaded to be allowed to return to the party of white supremacy."[70][71]

In Louisiana, the 1896 Louisiana gubernatorial election was competitive, with incumbent Democratic governor Murphy J. Foster defeating the Republican-Populist fusion candidate John Newton Pharr (1829–1903), a sugar planter from St. Mary Parish. Pharr had possibly gained a majority of votes cast and won twenty-six of the then fifty-nine parishes, with his greatest strength in north central Louisiana and the Florida Parishes to the east of Baton Rouge.[72] With the assistance of the Democratic political machine based in New Orleans, Foster officially received 116,116 votes (57 percent) to Pharr's 87,698 ballots (43 percent).[73] The election was heavily marked by fraud which benefited Foster and widespread violence to suppress black Republican voting, and a clear accounting of the election results is unknown.[74] Subsequently, as governor, Foster signed off on the new Louisiana Constitution of 1898, establishing a poll tax, literacy test, grandfather clause, and the secret ballot that made voting by poor whites much more difficult and producing a reduction in the number of registered black voters by 96 percent, from 130,334 to 5,320. After Foster's re-election in 1896, Louisiana general elections were non-competitive. The only competition took place in Democratic primaries.[75]

In Georgia, Thomas E. Watson had long supported black enfranchisement throughout the South, as a basic tenet of his populist philosophy.[76] He condemned lynching and tried to protect black voters from lynch mobs. The Populists made significant runs for governor in 1892, 1894, and 1896, which would have been stronger but for large scale electoral fraud.[77] However, after 1900 Watson's interpretation of populism shifted. He no longer viewed the populist movement as being racially inclusive. By 1908, Watson identified as a white supremacist and ran as such during his presidential bid. He used his highly influential magazine and newspaper to launch vehement diatribes against blacks.[76]

Disfranchisement

[edit]To prevent bi-racial and Populist coalitions in the future and to stop relying on violence and electoral fraud associated with suppressing the black vote during elections, Southern Democrats acted to disfranchise both black people and poor white people.[78] From 1890 to 1910, after the failure of the Lodge Bill and beginning with Mississippi in 1890, all 11 former Confederate states adopted new constitutions and other laws which included various devices to restrict voter registration. These changes disfranchised virtually all black and many poor white residents.[3] These devices applied to all citizens; in practice they disfranchised most black citizens and also "would remove [from voter registration rolls] the less educated, less organized, more impoverished whites as well – and that would ensure one-party Democratic rules through most of the 20th century in the South".[79][80] All the Southern states adopted provisions that restricted voter registration and suffrage, including new requirements for poll taxes, longer residency, and subjective literacy tests. Some also used the device of grandfather clauses, exempting voters who had a grandfather voting by a particular year (usually before the Civil War, when black people could not vote.)[81]

In 1900, U.S. Senator Benjamin Tillman explained how African Americans were disenfranchised in his state of South Carolina in a white supremacist speech:

In my State there were 135,000 negro voters, or negroes of voting age, and some 90,000 or 95,000 white voters.... Now, I want to ask you, with a free vote and a fair count, how are you going to beat 135,000 by 95,000? How are you going to do it? You had set us an impossible task.

We did not disfranchise the negroes until 1895. Then we had a constitutional convention convened which took the matter up calmly, deliberately, and avowedly with the purpose of disfranchising as many of them as we could under the fourteenth and fifteenth amendments. We adopted the educational qualification as the only means left to us, and the negro is as contented and as prosperous and as well protected in South Carolina to-day as in any State of the Union south of the Potomac. He is not meddling with politics, for he found that the more he meddled with them the worse off he got. As to his "rights"—I will not discuss them now. We of the South have never recognized the right of the negro to govern white men, and we never will.... I would to God the last one of them was in Africa and that none of them had ever been brought to our shores.[82]

White Democrats also opposed Republican economic policies such as the high tariff and the gold standard, both of which were seen as benefiting Northern industrial interests at the expense of the agrarian society of the South during the 19th century. Nevertheless, holding all political power was at the heart of their resistance. From 1876 through 1944, the national Democratic party opposed any calls for civil rights for black people. In Congress, Southern Democrats blocked such efforts whenever Republicans targeted the issue.[83][7]

White Democrats passed "Jim Crow" laws which reinforced white supremacy through racial segregation.[84] The Fourteenth Amendment provided for apportionment of representation in Congress to be reduced if a state disenfranchised part of its population. However, this clause was never applied to Southern states that disenfranchised black residents. No black candidate was elected to any office in the South for decades after the turn of the century. Black residents were also excluded from juries and other participation in civil life.[3]

Electoral dominance

[edit]

Democratic candidates won by large margins in a majority of Southern states in every presidential election from 1876 to 1948, except for 1928, when the Democratic candidate was Al Smith, a Catholic New Yorker. Even in that election, the divided South provided Smith with nearly three-fourths of his electoral votes. Scholar Richard Valelly credited Woodrow Wilson's 1912 election to the disfranchisement of black people in the South, and also noted far-reaching effects in Congress, where the Democratic South gained "about 25 extra seats in Congress for each decade between 1903 and 1953".[d][3] Journalist Matthew Yglesias argues:

The weird thing about Jim Crow politics is that white southerners with conservative views on taxes, moral values, and national security would vote for Democratic presidential candidates who didn't share their views. They did that as part of a strategy for maintaining white supremacy in the South.[85]

Some of the former Confederate states, particularly those that were not majority-African American, likely would have still voted Democratic even if African Americans were not disenfranchised due to partisan loyalty. In particular, Texas had never voted for a Republican presidential candidate until 1928, even during Reconstruction.[86] The border state of Kentucky still remained a Democratic stronghold in presidential elections, even though it did not disenfranchise African Americans.[4]

In the Deep South (South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana), Democratic dominance was overwhelming, with Democrats routinely receiving 80%–90% of the vote, and only a tiny number of Republicans holding state legislative seats or local offices.[7] Mississippi and South Carolina were the most extreme cases – between 1900 and 1944, only in 1928, when the three subcoastal Mississippi counties of Pearl River, Stone and George went for Hoover, did the Democrats lose even one of these two states' counties in any presidential election.[87]

The German-American Texas counties of Gillespie and Kendall, Arkansas Ozarks counties of Newton and Searcy, and a number of counties in Appalachian parts of Alabama and Georgia would vote Republican in presidential elections through this period.[88] Arkansas consistently voted Democratic from 1876 to 1964, though Democratic margins were lower than in the Deep South.[88] Even in 1939, Florida was described as "still very largely an empty State," with only North Florida largely settled until after World War II.[89] In Louisiana, non-partisan tendencies remained strong among wealthy sugar planters in Acadiana (Cajun Country) and within the business elite of New Orleans.[90]

In East Tennessee, Western North Carolina, and Southwest Virginia, Republicans retained a significant presence in these remote Appalachian regions which supported the Union during the Civil War and had few African Americans, winning occasional U.S. House seats and often drawing over 40% in presidential votes statewide.[91] In particular, Tennessee's 1st and 2nd congressional districts have been continuously held by Republicans since 1881 and 1867, respectively, to the present day. Although Tennessee disenfranchised African Americans, support for Republicans remained high in East Tennessee and kept the state relatively competitive during the Jim Crow era, although Democrats almost always still won statewide.[92]

1920s onwards

[edit]

By the 1920s, as memories of the Civil War faded, the Solid South cracked slightly. For instance, a Republican was elected U.S. Representative from Texas in 1920, serving until 1932. The Republican national landslides in 1920 and 1928 had some effects.[93] In the 1920 elections, Tennessee elected a Republican governor and five out of 10 Republican U.S. Representatives, and became the first former Confederate state to vote for a Republican candidate for U.S. President since Reconstruction.[94] North Carolina abolished its poll tax in 1920.[95][96]

In the 1928 presidential election, Al Smith received serious backlash as a Catholic in the largely Protestant South in 1928.[97] Southern Baptist churches ordered their followers to vote against Smith, claiming that he would close down Protestant churches, end freedom of worship, and prohibit reading the Bible.[97] However, it was widely believed that Republican Herbert Hoover supported integration or at least was not committed to maintaining racial segregation, overcoming opposition to Smith's campaign in areas with large nonvoting black populations.[97] Smith only managed to carry Arkansas (the home state of his running mate Joseph T. Robinson) and the 5 states of the Deep South, and nearly lost Alabama by less than 3%.[93]

The boll weevil, a species of beetle that feeds on cotton buds and flowers, crossed the Rio Grande near Brownsville, Texas, to enter the United States from Mexico in 1892.[98] It reached southeastern Alabama in 1909, and by the mid-1920s had entered all cotton-growing regions in the U.S., traveling 40 to 160 miles per year. The boll weevil contributed to Southern farmers' economic woes during the 1920s, a situation exacerbated by the Great Depression in the 1930s.[99] The boll weevil infestation has been credited with bringing about economic diversification in the Southern US, including the expansion of peanut cropping. The citizens of Enterprise, Alabama, erected the Boll Weevil Monument in 1919, perceiving that their economy had been overly dependent on cotton, and that mixed farming and manufacturing were better alternatives.[100] By 1922, it was taking 8% of the cotton in the country annually. A 2020 NBER paper found that the boll weevil spread contributed to fewer lynchings, less Confederate monument construction, less KKK activity, and higher non-white voter registration.[101]

Southern demography also began to change.[102] From 1910 through 1970, about 6.5 million black Southerners moved to urban areas in other parts of the country in the Great Migration, and demographics began to change Southern states in other ways. The failures of the South's cotton crop due to the boll weevil was a major impetus for the Great Migration, although not the only one.[103]

However, with the Democratic national landslide of 1932, the South again became solidly Democratic.[104] A number of conservative Southern Democrats felt chagrin at the national party's growing friendliness to organized labor during the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration, forming the conservative coalition with conservative Republicans in 1937 to stymie further New Deal legislation.[105] Roosevelt was unsuccessful in attempting to purge some of these conservative Southern Democrats in white primaries in the 1938 elections, such as Senator Walter George of Georgia and Senator Ellison Smith of South Carolina, in contrast to successfully ousting representative and chair of the House Rules Committee John J. O'Connor of New York.[106]

In the 1930s, black voters outside the South largely switched to the Democrats,[107] and other groups with an interest in civil rights (notably Jews, Catholics, and academic intellectuals) became more powerful in the party.[108] Louisiana abolished its poll tax in 1934,[109] as did Florida in 1937.[110]

The Republican Party began to make gains in the South after World War II, as the South industrialized and urbanized.[111][7] World War II marked a time of dramatic change within the South from an economic standpoint, as new industries and military bases were developed by the federal government, providing much-needed capital and infrastructure in the former Confederate states.[112][111] Per capita income jumped 140% from 1940 to 1945, compared to 100% elsewhere in the United States. Dewey Grantham said the war "brought an abrupt departure from the South's economic backwardness, poverty, and distinctive rural life, as the region moved perceptively closer to the mainstream of national economic and social life."[113][114][115]

Florida began to expand rapidly after World War II, with retirees and other migrants in Central and South Florida becoming a majority of the state's population. Many of these new residents brought their Republican voting habits with them, diluting traditional Southern hostility to the Republicans.[116] In 1944, the Supreme Court ruled 8–1 in Smith v. Allwright against white primary systems, and most Southern states ended their racially discriminatory primary elections.[117] They retained other techniques of disenfranchisement, such as poll taxes and literacy tests, which in theory applied to all potential voters, but in practice were administered in a discriminatory manner by white officials.[118]

Oklahoma

[edit]

Oklahoma was considered part of the Solid South, but did not become a state until 1907, and shared characteristics of both the border states and the former Confederate states in the Upper South. Oklahoma disenfranchised its African American population, which comprised less than 10% of the state's population from 1870 to 1960.[120] However, Oklahoma did not enact a poll tax and remained electorally competitive at the state and federal levels during the Jim Crow era.[121] Oklahoma elected three Republican U.S. Senators before 1964: John W. Harreld (1921–1927), William B. Pine (1925–1931), and Edward H. Moore (1943–1949).[121] Oklahoma had a strong Republican presence in Northwestern Oklahoma, which had close ties to neighboring Kansas, a Republican stronghold.[122]

During the Civil War, most of present-day Oklahoma was designated as Indian Territory and permitted slavery, with most tribal leaders aligning with the Confederacy.[123] However, some tribes and bands sided with the Union, resulting in bloody conflict in the territory, with severe hardships for all residents.[124][125] The Oklahoma Territory was settled through a series of land runs from 1889 to 1895, which included significant numbers of Republican settlers from the Great Plains.[126]

Oklahoma did not have a Republican governor until Henry Bellmon was elected in 1962, though Republicans were still able to draw over 40% of the vote statewide during the Jim Crow era.[127] Democrats were strongest in Southeast Oklahoma, known as "Little Dixie", whose white settlers were Southerners seeking a start in new lands following the American Civil War.[121] In Guinn v. United States (1915), the Supreme Court invalidated the Oklahoma Constitution's "old soldier" and "grandfather clause" exemptions from literacy tests. Oklahoma and other states quickly reacted by passing laws that created other rules for voter registration that worked against blacks and minorities.[128]

However, Oklahoma did not enact a poll tax, unlike the former Confederate states.[120] As a result, Oklahoma was still competitive at the presidential level, voting for Warren G. Harding in 1920 and Herbert Hoover in 1928. Oklahoma shifted earlier to supporting Republican presidential candidates, with the state voting for every Republican ticket since 1952, except for Lyndon B. Johnson in his 1964 landslide. Oklahoma is the only Southern state to have never voted for a Democratic presidential candidate after 1964. It was one of only two Southern states, the other being Virginia, to be carried by Republican Gerald Ford in the 1976 presidential election.[129]

Border states

[edit]

In contrast to the 11 former Confederate states, where almost all blacks were disenfranchised during the first half to two-thirds of the twentieth century, for varying reasons blacks remained enfranchised in the border states despite movements for disfranchisement during the 1900s.[130] Note that Missouri is classified as a Midwestern state by the Census bureau, and also did not disenfranchise its African American population.[131]

The border states, being the northern region of the Upper South, had close ties to the industrializing and urbanizing Northeast and Midwest, experiencing a realignment in the 1896 United States presidential election.[132][133]

African Americans generally comprised a significantly lower percentage of the populations of the border states than the percentages in the former Confederate states from 1870 to 1960. Less than 10% of the populations of West Virginia and Missouri were African American. In Kentucky, 5–20% of the state's population was African American. In Delaware, 10–20% of the state's population was African American. In Maryland, 15–25% of the state's population was African American.[134]

West Virginia

[edit]For West Virginia, "reconstruction, in a sense, began in 1861".[135] Unlike the other southern border states, West Virginia did not send the majority of its soldiers to the Union and a substantial portion of the state continued to be controlled by the Confederacy till later in the war.[136] West Virginia was the last slave state admitted into the Union in 1863, and was the only state in the Border South to also participate in the 1863 Confederate elections. The prospect of those returning ex-Confederates prompted the Wheeling state government to implement laws that restricted their right of suffrage, practicing law and teaching, access to the legal system, and subjected them to "war trespass" lawsuits.[137] The lifting of these restrictions in 1871 resulted in the election of John J. Jacob, a Democrat, to the governorship. It also led to the rejection of the war-time constitution by public vote and a new constitution written under the leadership of ex-Confederates such as Samuel Price, Allen T. Caperton and Charles James Faulkner. In 1876 the state Democratic ticket of eight candidates were all elected, seven of whom were Confederate veterans.[138] For nearly a generation West Virginia was part of the Solid South.[139]

However, Republicans returned to power in 1896, controlling the governorship for eight of the next nine terms, and electing 82 of 106 U.S. Representatives until 1932.[140] In 1932, as the nation swung to the Democrats, West Virginia again became solidly Democratic. It was perhaps the most reliably Democratic state in the nation between 1932 and 1996, being one of just two states (along with Minnesota) to vote for a Republican president as few as three times in that interval. Moreover, unlike Minnesota (or other nearly as reliably Democratic states like Massachusetts and Rhode Island), it usually had a unanimous (or nearly unanimous) congressional delegation and only elected two Republicans as governor (albeit for a combined 20 years between them).[141]

Kentucky

[edit]Kentucky did usually vote for the Democratic Party in the majority of presidential elections from 1877 to 1964 and was generally considered part of the Solid South, but was still a competitive state at both the state and federal levels.[142] The Democratic Party in the state was heavily divided over free silver and the role of corporations in the middle 1890s, and lost the governorship for the first time in forty years in 1895.[143] In contrast to the former Confederate States, Kentucky was part of the Upper South and bordered the industrial Midwest across the Ohio River, and had a significant urban working class who supported Republicans.[144] In the 1896 presidential election, the state was exceedingly close, with McKinley becoming the first Republican presidential candidate to carry Kentucky, by a mere 277 votes, or 0.06352%. McKinley's victory was, by percentage margin, the seventh-closest popular results for presidential electors on record.[e]

Before the Civil War, Kentucky had a southern plantation economy heavily relying on slavery with tobacco plantations in the central and western portions of the state. Kentucky remained mostly in the Union during the Civil War, though it was heavily contested, with the Confederacy controlling half the state early in the war. Delegates from 68 of 110 Kentucky counties signed an ordinance of secession at the Russellville Convention and formed the Confederate government of Kentucky, joining the CSA on December 10, 1861 with the signature of Jefferson Davis. However, some pro-Union eastern counties in the state have never voted Democratic to this day, similar to neighboring East Tennessee. The secessionist central and western areas of the state were strongly Democratic during the Jim Crow era.[145]

Kentucky remained extremely competitive at the state level even after the failure of the Lodge Bill, due to the state being mostly White and the divide between formerly secessionist and unionist areas. Lexington's city government had passed a poll tax in 1901, but it was declared invalid in state circuit courts. Six years later, a new state legislative effort to disenfranchise blacks failed because of the strong organization of the Republican Party in the pro-Union regions of the state.[145]

Republicans won Kentucky in the 1924 and 1928 presidential elections, the former of which was the only state that Warren G. Harding lost in the 1920 presidential election, but Coolidge won in the 1924 presidential election.[146][147] Kentucky also elected some Republican governors during this period, such as William O'Connell Bradley (1895–1899), Augustus E. Willson (1907–1911), Edwin P. Morrow (1919–1923), Flem D. Sampson (1927–1931), and Simeon Willis (1943–1947).[148]

Maryland

[edit]Before the Civil War, Maryland had a southern plantation economy focused around tobacco plantations using slavery centered in Southern Maryland and the Eastern Shore. During the war despite initially voting against secession, due to Southern sympathies in the state and requests by the state for Northern troops to leave the state. the Federal government put Maryland very quickly under Northern military occupation and imprisoned a portion of the state legislature, as well as suspending Habeas Corpus to force the state to stay in the Union and deter any attempts at secession. Maryland very narrowly, by a vote of 30,174 to 28,380 (52% to 48%), abolished slavery in 1864.[149] Maryland was considered part of the Solid South and voted for the Democratic Party presidential candidate from 1868 to 1892, but the 1896 presidential election was a realignment in the state, similar to West Virginia. Maryland voted for the Republican Party presidential candidate from 1896 to 1928, except for Democrat Woodrow Wilson in 1912 and 1916.[150]

In contrast to the former Confederate states, nearly half the African American population was free before the Civil War, and some had accumulated property. Literacy was high among African Americans and, as Democrats crafted means to exclude them, suffrage campaigns helped reach blacks and teach them how to resist.[151] In 1895, a biracial Republican coalition enabled the election of Lloyd Lowndes, Jr. as governor (1896 to 1900).[151]

The Democrat-dominated state legislature tried to pass disfranchising bills in 1905, 1907, and 1911, but was rebuffed on each occasion, in large part because of black opposition and strength. Black men comprised 20% of the electorate and had established themselves in several cities, where they had comparative security. In addition, immigrant men comprised 15% of the voting population and opposed these measures. The legislature had difficulty devising requirements against blacks that did not also disadvantage immigrants.[152] In 1910, the legislature proposed the Digges Amendment to the state constitution. It would have used property requirements to effectively disenfranchise many African American men as well as many poor white men (including new immigrants). The Maryland General Assembly passed the bill, which Governor Austin Lane Crothers supported. Before the measure went to popular vote, a bill was proposed that would have effectively passed the requirements of the Digges Amendment into law. Due to widespread public opposition, that measure failed, and the amendment was also rejected by the voters of Maryland with 46,220 votes for and 83,920 votes against the proposal.[153]

Nationally Maryland citizens achieved the most notable rejection of a black-disfranchising amendment. The power of black men at the ballot box and economically helped them resist these bills and disfranchising effort. In 1911, Republican Phillips Lee Goldsborough (1912 to 1916) was elected governor, succeeding Crothers. Maryland elected two more Republican governors from 1877 to 1964, Harry Nice (1935 to 1939) and Theodore McKeldin (1951 to 1959).[154]

Delaware

[edit]Before the war, Delaware used slavery in the southern portion of the state but it was very sparse compared to other southern states even in the Upper South. During the war, despite there being some Southern sympathies in the state, the state legislature very quickly rejected secession and didnt consider it further. Despite Delaware being a southern border state and not abolishing slavery until the ratification of the 13th amendment, due its proximity to the Northeast and not bordering any of the former Confederate States, Delaware voted for the Republican Party in a majority of presidential elections from 1876 to 1964 (12 out of 23).[155]

For a generation bitter memories of Republican actions during the Civil War had kept the Democrats firmly in control of the government throughout Delaware. However, during this period gas executive J. Edward Addicks, a Philadelphia millionaire, established residence in Delaware, and began pouring money into the Republican Party, especially in Kent and Sussex County.[156] He succeeded in reigniting the Republican Party, which would soon become the dominant party in the state. In 1894, Republican Joshua H. Marvil was elected as the first Republican governor of Delaware since Reconstruction.[157] The allegiance of industries with the Republican party allowed them to gain control of Delaware's governorship throughout most of the twentieth century. The Republican Party ensured Black people could vote because of their general support for Republicans and thus undid restrictions on Black suffrage.[158]

Delaware was generally associated with the Solid South and voted for the Democratic Party presidential candidate from 1876 to 1892, but then consistently voted for the Republican Party presidential candidate from 1896 to 1932, except in 1912 for Woodrow Wilson when the Republican Party split. Delaware voted for Republican Herbert Hoover in 1932, despite Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt winning in a landslide.[159]

Missouri

[edit]A southern state with a plantation economy based around tobacco, hemp, and cotton in the central and southeastern portions of the state using enslaved labor before the war. Although a southern border state during the Civil War and heavily contested and claimed by the Confederacy with the Confederate government of Missouri, Missouri abolished slavery in January 1865, before the Civil War ended.[160] Missouri enacted racial segregation, but did not disenfranchise African Americans, who comprised less than 10% of the state's population from 1870 to 1960. In particular, Missouri never implemented a poll tax as a requirement to vote, unlike even neighboring Kentucky or Tennessee.[161]

Although generally considered part of the Solid South until 1904. Between the Civil War and the end of World War II, Missouri transitioned from a rural southern state to a hybrid industrial-service-agricultural midwestern state as the Midwest rapidly industrialized and expanded into Missouri. Missouri received major Midwestern migration after the war, overtaking the state's original Southern population, including in Kansas City, Missouri and St. Louis.[131] Missouri voted for the Republican presidential candidate in the 1904 presidential election for the first time since 1872, repositioning itself from being associated with the Solid South to being seen as a bellwether state throughout the twentieth century. From 1904 until 2004, Missouri only backed a losing presidential candidate once, in 1956.[162] Missouri also elected some Republican governors before 1964, beginning with Herbert S. Hadley (1909–1913).[163]

Presidential voting

[edit]

The 1896 election resulted in the first break in the Solid South. Florida politician Marion L. Dawson, writing in the North American Review, observed: "The victorious party not only held in line those States which are usually relied upon to give Republican majorities ... More significant still, it invaded the Solid South, and bore off West Virginia, Maryland, and Kentucky; caused North Carolina to tremble in the balance and reduced Democratic majorities in the following States: Alabama, 39,000; Arkansas, 29,000; Florida, 6,000; Georgia, 49,000; Louisiana, 33,000; South Carolina, 6,000; and Texas, 29,000. These facts, taken together with the great landslide of 1894 and 1895, which swept Missouri and Tennessee, Maryland and Kentucky over into the country of the enemy, have caused Southern statesmen to seriously consider whether the so-called Solid South is not now a thing of past history".[164] The former Confederate states stayed mostly a single bloc until the 1960s, with a brief break in the 1920s, however.

In the 1904 election, Missouri supported Republican Theodore Roosevelt, while Maryland awarded its electors to Democrat Alton Parker, despite Roosevelt's winning by 51 votes.[165] Missouri was a bellwether state from 1904 to 2004, voting for the winner of every presidential election except in 1956.[166] By the 1916 election, disfranchisement of blacks and many poor whites was complete, and voter rolls had dropped dramatically in the South. Closing out Republican supporters gave a bump to Woodrow Wilson, who took all the electors across the South (apart from Delaware and West Virginia), as the Republican Party was stifled without support by African Americans.[3]

The 1920 presidential election was a referendum on President Wilson's League of Nations. Pro-isolation sentiment in the South benefited Republican Warren G. Harding, who won Tennessee, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Maryland. In 1924, Republican Calvin Coolidge won Kentucky, Missouri, and Maryland.[93]

In 1928, Herbert Hoover, benefiting from bias against his Democratic opponent Al Smith (who was a Roman Catholic and opposed Prohibition),[167] won not only those Southern states that had been carried by either Harding or Coolidge (Tennessee, Kentucky, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Maryland), but also won Florida, North Carolina, Texas, and Virginia, none of which had voted Republican since Reconstruction. He furthermore came within 3% of carrying the Deep South state of Alabama. Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover all carried the two Southern states that had supported Hughes in 1916, West Virginia and Delaware. Al Smith received serious backlash as a Catholic in the largely Protestant South in 1928, carrying only his running mate Joseph T. Robinson's home state of Arkansas and the 5 states of the Deep South.[168] The only place where Smith's Catholicism helped him in the South was heavily-Catholic Acadiana in Louisiana.[169] Smith nearly lost Alabama, which he held by 3%, which had Hoover won, would have physically split the Solid South.[170]

The South appeared "solid" again during the period of Franklin D. Roosevelt's political dominance, as his New Deal welfare programs and military buildup invested considerable money in the South, benefiting many of its citizens, including during the Dust Bowl. Roosevelt carried all the 11 former Confederate states and Oklahoma in each of his four presidential elections.[171]

After World War II

[edit]

Democratic President Harry S. Truman, who grew up in the border state of Missouri where segregation was practiced and largely accepted, issued Executive Order 9981 in July 1948, prohibiting racial segregation in the armed forces.[172] Truman's support of the civil rights movement, combined with the adoption of a civil rights plank in the 1948 Democratic platform proposed by future Vice President Hubert Humphrey,[173] prompted many Southerners to walk out of the Democratic National Convention and form the Dixiecrat Party.[174] This splinter party played a significant role in the 1948 election; the Dixiecrat candidate, Strom Thurmond, carried Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, his native South Carolina, and one electoral vote from Tennessee.[7]

Despite this, in one of the greatest election upsets in American history,[175][176] incumbent Democratic President Harry S. Truman defeated heavily favored Republican New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey. Truman won every electoral vote in the former Confederate states not won by Thurmond.[177] Three former Confederate states repealed their poll taxes after World War II, specifically Georgia (1945), South Carolina (1951), and Tennessee (1953).[178][179]

In the elections of 1952 and 1956, the popular Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower, commander of the Allied armed forces during World War II, carried several Southern states, with especially strong showings in the new suburbs.[180] Even in the Deep South, Eisenhower's performances were relatively competitive, sometimes winning at least 40% of the vote statewide.[181] Most of the Southern states he carried had voted for at least one of the Republican winners in the 1920s, but in 1956, Eisenhower carried Louisiana, becoming the first Republican to win the state since Rutherford B. Hayes in 1876. The rest of the Deep South voted for his Democratic opponent, Adlai Stevenson.[182]

In the 1960 election, the Democratic nominee, John F. Kennedy, continued his party's tradition of selecting a Southerner as the vice presidential candidate (in this case, Senator Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas).[183] Kennedy and Johnson, however, both supported civil rights.[184] In October 1960, when Martin Luther King Jr. was arrested at a peaceful sit-in in Atlanta, Georgia, Kennedy placed a sympathetic phone call to King's wife, Coretta Scott King, and Kennedy's brother Robert F. Kennedy helped secure King's release. King expressed his appreciation for these calls. Although King made no endorsement, his father, who had previously endorsed Republican Richard Nixon, switched his support to Kennedy.[185]

By the mid-1960s, changes had come in many Southern states. Former Dixiecrat Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina changed parties in 1964; Texas elected a Republican Senator in 1961;[186] Florida and Arkansas elected Republican governors in 1966, as did Virginia in 1969. In the Upper South, where Republicans had always been a small presence, Republicans gained a few seats in the House and Senate.[108]

Because of these and other events, the Democrats lost ground with white voters in the South, as those same voters increasingly lost control over what was once a whites-only Democratic Party in much of the South.[187] The 1960 election was the first in which a Republican presidential candidate received electoral votes from the former Confederacy while losing nationally. Nixon carried Virginia, Tennessee, and Florida, which he would also win in 1968 and 1972. Though the Democrats also won Alabama and Mississippi, slates of unpledged electors, representing Democratic segregationists, awarded those states' electoral votes to Harry Byrd, rather than Kennedy.[188]

The parties' positions on civil rights continued to evolve in the run up to the 1964 election. The Democratic candidate, Johnson, who had become president after Kennedy's assassination, spared no effort to win passage of a strong Civil Rights Act of 1964. After signing the landmark legislation, Johnson said to his aide, Bill Moyers: "I think we just delivered the South to the Republican Party for a long time to come."[189] In contrast, Johnson's Republican opponent, Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona, voted against the Civil Rights Act, believing it enhanced the federal government and infringed on the private property rights of businessmen.[190] Goldwater did support civil rights in general and universal suffrage, and voted for the 1957 Civil Rights Act (though casting no vote on the 1960 Civil Rights Act), as well as voting for the Twenty-fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which banned poll taxes as a requirement for voting. This was one of the devices that states used to disfranchise African Americans and the poor.[191][192][193]

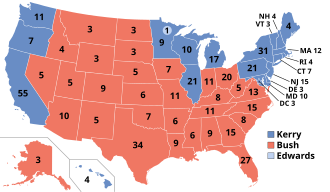

In November 1964, Johnson won a landslide electoral victory, and the Republicans suffered significant losses in Congress. Goldwater, however, besides carrying his home state of Arizona, carried the Deep South: voters in Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and South Carolina had switched parties for the first time since Reconstruction.[194] Goldwater notably won only in Southern states that had voted against Republican Richard Nixon in 1960, while not winning a single Southern state which Nixon had carried. Previous Republican inroads in the South had been concentrated on high-growth suburban areas, often with many transplants, as well as on the periphery of the South.[2][1]

Harold D, Woodman summarizes the explanation that external forces caused the disintegration of the Jim Crow South from the 1920s to the 1970s:

- When a significant change finally occurred, its impetus came from outside the South. Depression-bred New Deal reforms, war-induced demand for labor in the North, perfection of cotton-picking machinery, and civil rights legislation and court decisions finally... destroyed the plantation system, undermined landlord or merchant hegemony, diversified agriculture and transformed it from a labor- to a capital-intensive industry, and ended the legal and extra-legal support for racism. The discontinuity that war, invasion, military occupation, the confiscation of slave property, and state and national legislation failed to bring in the mid-19th century, finally arrived in the second third of the 20th century. A "second reconstruction" created a real New South.[102]

Southern strategy

[edit]

The "Southern strategy" was the long-term Republican Party electoral strategy to increase political support among white voters in the Southern United States since the 1960s. According to a quantitative analysis done by Ilyana Kuziemko and Ebonya Washington, racial backlash played a central role in the decline in relative white Southern Democratic identification.[196][197][198] Support for the civil rights movement in the 1960s by Democratic presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson solidified the Democrats' support within the African American community. African Americans have consistently voted between 85% and 95% Democratic since the 1960s.[199][200][201]

Although Richard Nixon carried 49 states in 1972, including every Southern state, the Republican Party remained quite weak at the local and state levels across the entire South for decades. Glenn Feldman argues that "the South did not become Republican so much as the Republican Party became southern."[202] Republicans first won a majority of U.S. House seats in the South in the 1994 "Republican Revolution", and only began to dominate the South after the 2010 elections.[8][203] Many analysts believe the Southern Strategy that has been employed by Republicans since the 1960s is now virtually complete, with Republicans in dominant, almost total, control of political offices in the South since the 2010s.[204][205][206]

Scholars have debated the extent to which ideological "divisions over the size of government (including taxes, social programs, and regulation), national security, and moral issues such as abortion and gay rights, with racial issues only one of numerous areas about which liberals and conservatives disagree," were responsible for the realignment.[207][208][209][210] When looked at broadly, studies have shown that White Southerners tend to be more conservative, both fiscally and socially,[211][212][85] than most non-Southerners and African Americans.[213][214] Historically, Southern Democrats were generally more conservative than non-Southern Democrats, joining factions such as the conservative coalition and Boll weevils.[215][216]

Yellow dog Democrats is a term for voters in the Southern United States who voted solely for Democratic Party candidates, though they would often split their tickets and vote for Republican presidential candidates. Some have argued that the South remained Democratic for decades because it was only until Yellow dog Democrats died out or stopped ticket-splitting for Democrats that Republicans began to dominate the South.[204] The conservative coalition lasted until 1994, and Bill Clinton was far less liberal than 21st century Democrats.[210]

The two Virginias, Virginia and West Virginia, have realigned in opposite directions since 1964.[141] Virginia went from voting Republican for president from 1968 to 2004 to always voting Democratic for president since 2008.[9] West Virginia has always voted Republican since 2000, after previously only voting Republican in 1972 and 1984.[217] In the 2024 United States presidential election, West Virginia gave the Republican presidential nominee 70% of the vote, the highest vote share in the state’s history. Meanwhile, Virginia voted for a Democratic presidential nominee who lost the popular vote, for the first time since 1924, a century earlier.[218]

1965 to 1980

[edit]

In the 1968 election, Richard Nixon saw the cracks in the Solid South as an opportunity to tap into a group of voters who had historically been beyond the reach of the Republican Party. With the aid of Harry Dent and South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond, who had switched to the Republican Party in 1964, Nixon ran his 1968 campaign on states' rights and "law and order". As a key component of this strategy, he selected as his running mate Maryland Governor Spiro Agnew.[219] Liberal Northern Democrats accused Nixon of pandering to Southern whites, especially with regard to his "states' rights" and "law and order" positions, which were widely understood by black leaders to legitimize the status quo of Southern states' discrimination.[220] This tactic was described in 2007 by David Greenberg in Slate as "dog-whistle politics".[221] According to an article in The American Conservative, Nixon adviser and speechwriter Pat Buchanan disputed this characterization.[222][223]

The independent candidacy of George Wallace, former Democratic governor of Alabama, partially negated Nixon's Southern Strategy.[224] With a much more explicit attack on integration and black civil rights, Wallace won all but two of Goldwater's states (the exceptions being South Carolina and Arizona) as well as Arkansas and one of North Carolina's electoral votes. Nixon picked up Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Florida, Oklahoma, Kentucky, Missouri, and Delaware. The Democrat, Hubert Humphrey, won Texas, heavily unionized West Virginia, and heavily urbanized Maryland. Writer Jeffrey Hart, who worked on the Nixon campaign as a speechwriter, said in 2006 that Nixon did not have a "Southern Strategy", but "Border State Strategy" as he said that the 1968 campaign ceded the Deep South to George Wallace. Hart suggested that the press called it a "Southern Strategy" as they are "very lazy".[225]

The 1968 election had been the first election in which both the Upper South and Deep South bolted from the Democratic party simultaneously. The Upper South had backed Eisenhower in 1952 and 1956, as well as Nixon in 1960.[226] The Deep South had backed Goldwater just four years prior. Despite the two regions of the South still backing different candidates, Wallace in the Deep South and Nixon in the Upper South, only Texas, Maryland, and West Virginia had held up against the majority Nixon-Wallace vote for Humphrey.[224] By 1972, Nixon had swept the South altogether, Upper and Deep South alike, marking the first time in American history a Republican won every Southern state.[227]

In the 1976 election, former Georgia governor Jimmy Carter gave Democrats a short-lived comeback in the South, winning every state in the old Confederacy except for Virginia, which was narrowly lost.[228] However, in his unsuccessful 1980 re-election bid, the only Southern states he won were his native state of Georgia, West Virginia, and Maryland. The year 1976 was the last year a Democratic presidential candidate won a majority of Southern electoral votes, or won Texas, Mississippi, Alabama, and South Carolina in a presidential election.[203] The Republicans took all the region's electoral votes in the 1984 election and every state except West Virginia in 1988.[229]

1980 to 1999

[edit]

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the South was still overwhelmingly Democratic at the state level, with majorities in all state legislatures, most U.S. House delegations, and many so-called New South governorships.[210] These New South governors were still relatively conservative, but avoided race-baiting. Some supported new government services, but typically avoided large tax increases and redistributionist programs.[230] Many conservative Southern white voters split their tickets, supporting conservative Democrats for local and statewide office while simultaneously voting for Republican presidential candidates.[216][227]

Republicans held 10 of the 22 US Senate seats and 39 seats in the US House of Representatives from the South after the 1980 elections, after winning control of the U.S. Senate for the first time since 1952. Republican president Ronald Reagan was able to form a governing majority due to a coalition between Republicans and conservative Southern Democrats, known as the boll weevils, named after the species of beetle destructive to cotton crops.[231]

Over the next 30 years, this gradually changed. Veteran Democratic officeholders retired or died, and older voters who were still rigidly Democratic died off.[202][204] As part of the Republican Revolution in the 1994 elections, Republicans captured a majority of the U.S. House's southern seats for the first time, which allowed them to win control of the U.S. House for the first time since 1952.[232] There were also increasing numbers of migrants from other areas, especially in Florida, Georgia, Texas, North Carolina, and Virginia.[233]

Some former Southern Democrats became Republicans, such as Kent Hance (1985), Rick Perry (1989), and Ralph Hall (2004) from Texas; Billy Tauzin (1995) and Jimmy Hayes (1995) from Louisiana; Richard Shelby (1994) and Kay Ivey (2002) from Alabama; and Nathan Deal (1995) and Sonny Perdue (1998) from Georgia.[234][198]