Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hydrogen chalcogenide

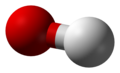

View on WikipediaHydrogen chalcogenides (also chalcogen hydrides or hydrogen chalcides) are binary compounds of hydrogen with chalcogen atoms (elements of group 16: oxygen, sulfur, selenium, tellurium, polonium, and livermorium). Water, the first chemical compound in this series, contains one oxygen atom and two hydrogen atoms, and is the most common compound on the Earth's surface.[1]

Dihydrogen chalcogenides

[edit]The most important series, including water, has the chemical formula H2X, with X representing any chalcogen. They are therefore triatomic. They take on a bent structure and as such are polar molecules. Water is an essential compound to life on Earth today,[2] covering 70.9% of the planet's surface. The other hydrogen chalcogenides are usually extremely toxic, and have strong unpleasant scents usually resembling rotting eggs or vegetables. Hydrogen sulfide is a common product of decomposition in oxygen-poor environments and as such is one chemical responsible for the smell of flatulence. It is also a volcanic gas. Despite its toxicity, the human body intentionally produces it in small quantities for use as a signaling molecule.

Water can dissolve the other hydrogen chalcogenides (at least those up to hydrogen telluride), forming acidic solutions known as hydrochalcogenic acids. Although these are weaker acids than the hydrohalic acids, they follow a similar trend of acid strength increasing with heavier chalcogens, and also form in a similar way (turning the water into a hydronium ion H3O+ and the solute into a XH− ion). It is unknown if polonium hydride forms an acidic solution in water like its lighter homologues, or if it behaves more like a metal hydride (see also hydrogen astatide).

| Compound | As aqueous solution | Chemical formula | Geometry | pKa | model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hydrogen oxide oxygen hydride water (oxidane) |

water | H2O | 13.995 |

| |

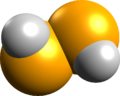

| hydrogen sulfide sulfur hydride (sulfane) |

hydrosulfuric acid | H2S |  |

7.0 |

|

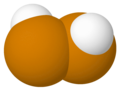

| hydrogen selenide selenium hydride (selane) |

hydroselenic acid | H2Se |  |

3.89 |

|

| hydrogen telluride tellurium hydride (tellane) |

hydrotelluric acid | H2Te |  |

2.6 |

|

| hydrogen polonide polonium hydride (polane) |

hydropolonic acid | H2Po | ? |

| |

| hydrogen livermoride[3] livermorium hydride (livermorane) |

hydrolivermoric acid | H2Lv | ? |

|

Some properties of the hydrogen chalcogenides follow:[4]

| Property | H2O | H2S | H2Se | H2Te | H2Po |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melting point (°C) | 0.0 | −85.6 | −65.7 | −51 | −35.3 |

| Boiling point (°C) | 100.0 | −60.3 | −41.3 | −4 | 36.1 |

| −285.9 | +20.1 | +73.0 | +99.6 | ? | |

| Bond angle (H–X–H) (gas) | 104.45° | 92.1° | 91° | 90° | 90.9° (predicted)[5] |

| Dissociation constant (HX−, K1) | 1.8 × 10−16 | 1.3 × 10−7 | 1.3 × 10−4 | 2.3 × 10−3 | ? |

| Dissociation constant (X2−, K2) | 0 | 7.1 × 10−15 | 1 × 10−11 | 1.6 × 10−11 | ? |

Many of the anomalous properties of water compared to the rest of the hydrogen chalcogenides may be attributed to significant hydrogen bonding between hydrogen and oxygen atoms. Some of these properties are the high melting and boiling points (it is a liquid at room temperature), as well as the high dielectric constant and observable ionic dissociation. Hydrogen bonding in water also results in large values of heat and entropy of vaporisation, surface tension, and viscosity.[6]

The other hydrogen chalcogenides are highly toxic, malodorous gases. Hydrogen sulfide occurs commonly in nature and its properties compared with water reveal a lack of any significant hydrogen bonding.[7] Since they are both gases at STP, hydrogen can be simply burned in the presence of oxygen to form water in a highly exothermic reaction; such a test can be used in beginner chemistry to test for the gases produced by a reaction as hydrogen will burn with a pop. Water, hydrogen sulfide, and hydrogen selenide may be made by heating their constituent elements together above 350 °C, but hydrogen telluride and polonium hydride are not attainable by this method due to their thermal instability; hydrogen telluride decomposes in moisture, in light, and in temperatures above 0 °C. Polonium hydride is unstable, and due to the intense radioactivity of polonium (resulting in self-radiolysis upon formation), only trace quantities may be obtained by treating dilute hydrochloric acid with polonium-plated magnesium foil. Its properties are somewhat distinct from the rest of the hydrogen chalcogenides, since polonium is a metal while the other chalcogens are not, and hence this compound is intermediate between a normal hydrogen chalcogenide or hydrogen halide such as hydrogen chloride, and a metal hydride like stannane. Like water, the first of the group, polonium hydride is also a liquid at room temperature. Unlike water, however, the strong intermolecular attractions that cause the higher boiling point are van der Waals interactions, an effect of the large electron clouds of polonium.[4]

Dihydrogen dichalcogenides

[edit]Dihydrogen dichalcogenides have the chemical formula H2X2, and are generally less stable than the monochalcogenides, commonly decomposing into the monochalcogenide and the chalcogen involved.

The most important of these is hydrogen peroxide, H2O2, a pale blue, nearly colourless liquid that has a lower volatility than water and a higher density and viscosity. It is important chemically as it can be either oxidised or reduced in solutions of any pH, can readily form peroxometal complexes and peroxoacid complexes, as well as undergoing many proton acid/base reactions. In its less concentrated form hydrogen peroxide has some major household uses, such as a disinfectant or for bleaching hair; much more concentrated solutions are much more dangerous.

| Compound | Chemical formula | Bond length | Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| hydrogen peroxide (dioxidane) |

H2O2 |  |

|

| hydrogen disulfide (disulfane) |

H2S2 |  | |

| hydrogen diselenide[8] (diselane) |

H2Se2 | — |  |

| hydrogen ditelluride[9] (ditellane) |

H2Te2 | — |  |

Some properties of the hydrogen dichalcogenides follow:

| Property | H2O2 | H2S2 | H2Se2 | H2Te2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melting point (°C) | −0.43 | −89.6 | ? | ? |

| Boiling point (°C) | 150.2 (decomposes) | 70.7 | ? | ? |

An alternative structural isomer of the dichalcogenides, in which both hydrogen atoms are bonded to the same chalcogen atom, which is also bonded to the other chalcogen atom, have been examined computationally. These H2X+–X– structures are ylides. This isomeric form of hydrogen peroxide, oxywater, has not been synthesized experimentally. The analogous isomer of hydrogen disulfide, thiosulfoxide, has been detected by mass spectrometry experiments.[10]

It is possible for two different chalcogen atoms to share a dichalcogenide, as in hydrogen thioperoxide (H2SO); more well-known compounds of similar description include sulfuric acid (H2SO4).

Higher dihydrogen chalcogenides

[edit]All straight-chain hydrogen chalcogenides follow the formula H2Xn.

Higher hydrogen polyoxides than H2O2 are not stable.[11] Trioxidane, with three oxygen atoms, is a transient unstable intermediate in several reactions. The next two in the oxygen series, tetraoxidane and pentaoxidane, have also been synthesized and found to be highly reactive. An alternative structural isomer of trioxidane, in which the two hydrogen atoms are attached to the central oxygen of the three-oxygen chain rather than one on each end, has been examined computationally.[12]

Beyond H2S and H2S2, many higher polysulfanes H2Sn (n = 3–8) are known as stable compounds.[13] They feature unbranched sulfur chains, reflecting sulfur's tendency for catenation. Starting with H2S2, all known polysulfanes are liquids at room temperature. H2S2 is colourless while the other polysulfanes are yellow; the colour becomes richer as n increases, as do the density, viscosity, and boiling point. A table of physical properties is given below.[14]

| Compound | Density at 20 °C (g·cm−3) | Vapour pressure (mmHg) | Extrapolated boiling point (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| H2S | 1.363 (g·dm−3) | 1740 (kPa, 21 °C) | −60 |

| H2S2 | 1.334 | 87.7 | 70 |

| H2S3 | 1.491 | 1.4 | 170 |

| H2S4 | 1.582 | 0.035 | 240 |

| H2S5 | 1.644 | 0.0012 | 285 |

| H2S6 | 1.688 | ? | ? |

| H2S7 | 1.721 | ? | ? |

| H2S8 | 1.747 | ? | ? |

However, they can easily be oxidised and are all thermally unstable, disproportionating readily to sulfur and hydrogen sulfide, a reaction for which alkali acts as a catalyst:[14]

- 8 H2Sn → 8 H2S + (n − 1) S8

They also react with sulfite and cyanide to produce thiosulfate and thiocyanate respectively.[14]

An alternative structural isomer of the trisulfide, in which the two hydrogen atoms are attached to the central sulfur of the three-sulfur chain rather than one on each end, has been examined computationally.[12] Thiosulfurous acid, a branched isomer of the tetrasulfide, in which the fourth sulfur is bonded to the central sulfur of a linear dihydrogen trisulfide structure ((HS)2S+−S−), has also been examined computationally.[15] Thiosulfuric acid, in which two sulfur atoms branch off of the central of a linear dihydrogen trisulfide structure has been studied computationally as well.[16]

Higher polonium hydrides may exist.[17]

Other hydrogen-chalcogen compounds

[edit]

Some monohydrogen chalcogenide compounds do exist and others have been studied theoretically. As radical compounds, they are quite unstable. The two simplest are hydroxyl (HO) and hydroperoxyl (HO2). The compound hydrogen ozonide (HO3) is also known,[18] along with some of its alkali metal ozonide salts are (various MO3).[19] The respective sulfur analogue for hydroxyl is sulfanyl (HS) and HS2 for hydroperoxyl.

One or both of the protium atoms in water can be substituted with the isotope deuterium, yielding respectively semiheavy water and heavy water, the latter being one of the most famous deuterium compounds. Due to the high difference in density between deuterium and regular protium, heavy water exhibits many anomalous properties. The radioisotope tritium can also form tritiated water in much the same way. Another notable deuterium chalcogenide is deuterium disulfide. Deuterium telluride (D2Te) has slightly higher thermal stability than protium telluride, and has been used experimentally for chemical deposition methods of telluride-based thin films.[20]

Hydrogen shares many properties with the halogens; substituting the hydrogen with halogens can result in chalcogen halide compounds such as oxygen difluoride and dichlorine monoxide, alongside ones that may be impossible with hydrogen such as chlorine dioxide.

Hydrogen Ions

[edit]One of the most well-known hydrogen chalcogenide ions is the hydroxide ion, and the related hydroxy functional group. The former is present in alkali metal, alkaline earth, and rare-earth hydroxides, formed by reacting the respective metal with water. The hydroxy group appears commonly in organic chemistry, such as within alcohols. The related bisulfide/sulfhydryl group appears in hydrosulfide salts and thiols, respectively.

The hydronium (H3O+) ion is present in aqueous acidic solutions, including the hydrochalcogenic acids themselves, as well as pure water alongside hydroxide.

References

[edit]- ^ "CIA – The world factbook". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

- ^ "About the International Decade for Action 'Water for Life' 2005-2015".

- ^ Nash, Clinton S.; Crockett, Wesley W. (2006). "An Anomalous Bond Angle in (116)H2. Theoretical Evidence for Supervalent Hybridization". The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 110 (14): 4619–4621. Bibcode:2006JPCA..110.4619N. doi:10.1021/jp060888z. PMID 16599427.

- ^ a b Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 766–7

- ^ Sumathi, K.; Balasubramanian, K. (1990). "Electronic states and potential energy surfaces of H2Te, H2Po, and their positive ions". Journal of Chemical Physics. 92 (11): 6604–6619. Bibcode:1990JChPh..92.6604S. doi:10.1063/1.458298.

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 623

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 682

- ^ Goldbach, Andreas; Saboungi, Marie-Louise; Johnson, J. A.; Cook, Andrew R.; Meisel, Dan (2000). "Oxidation of Aqueous Polyselenide Solutions. A Mechanistic Pulse Radiolysis Study". J. Phys. Chem. A. 104 (17): 4011–4016. Bibcode:2000JPCA..104.4011G. doi:10.1021/jp994361g.

- ^ Hop, Cornelis E. C. A.; Medina, Marco A. (1994). "H2Te2 Is Stable in the Gas Phase". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1994 (116): 3163–4. Bibcode:1994JAChS.116.3163H. doi:10.1021/ja00086a072.

- ^ Gerbaux, Pascal; Salpin, Jean-Yves; Bouchoux, Guy; Flammang, Robert (2000). "Thiosulfoxides (X2S=S) and disulfanes (XSSX): first observation of organic thiosulfoxides". International Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 195/196: 239–249. Bibcode:2000IJMSp.195..239G. doi:10.1016/S1387-3806(99)00227-4.

- ^ Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 633–8

- ^ a b Dobado, J. A.; Martínez-García, Henar; Molina, José; Sundberg, Markku R. (1999). "Chemical Bonding in Hypervalent Molecules Revised. 2. Application of the Atoms in Molecules Theory to Y2XZ and Y2XZ2 (Y = H, F, CH3; X = O, S, Se; Z = O, S) Compounds". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121 (13): 3156–3164. Bibcode:1999JAChS.121.3156D. doi:10.1021/ja9828206.

- ^ R. Steudel "Inorganic Polysulfanes H2S2 with n > 1" in Elemental Sulfur and Sulfur-Rich Compounds II (Topics in Current Chemistry) 2003, Volume 231, pp 99-125. doi:10.1007/b13182

- ^ a b c Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 683

- ^ Laitinen, Risto S.; Pakkanen, Tapani A.; Steudel, Ralf (1987). "Ab initio study of hypervalent sulfur hydrides as model intermediates in the interconversion reactions of compounds containing sulfur–sulfur bonds". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 109 (3): 710–714. Bibcode:1987JAChS.109..710L. doi:10.1021/ja00237a012.

- ^ Nishimoto, Akiko; Zhang, Daisy Y. (2003). "Hypervalency in sulfur? Ab initio and DFT studies of the structures of thiosulfate and related sulfur oxyanions". Sulfur Letters. 26 (5/6): 171–180. doi:10.1080/02786110310001622767. S2CID 95470892.

- ^ Liu, Yunxian; Duan, Defang; Tian, Fubo; Li, Da; Sha, Xiaojing; Zhao, Zhonglong; Zhang, Huadi; Wu, Gang; Yu, Hongyu; Liu, Bingbing; Cui, Tian (2015). "Phase diagram and superconductivity of polonium hydrides under high pressure". arXiv:1503.08587 [cond-mat.supr-con].

- ^ Cacace, F.; de Petris, G.; Pepi, F.; Troiani, A. (1999). "Experimental Detection of Hydrogen Trioxide". Science. 285 (5424): 81–82. doi:10.1126/science.285.5424.81. PMID 10390365.

- ^ Wiberg 2001, p. 497

- ^ Xiao, M. & Gaffney, T. R. Tellurium (Te) Precursors for Making Phase Change Memory Materials. (Google Patents, 2013) (https://www.google.ch/patents/US20130129603)

Bibliography

[edit]- Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. doi:10.1016/C2009-0-30414-6. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

Hydrogen chalcogenide

View on GrokipediaGeneral Characteristics

Definition and Classification

Hydrogen chalcogenides, also known as chalcogen hydrides, are binary compounds composed of hydrogen and one or more atoms from the chalcogen elements of group 16 in the periodic table.[4] The chalcogens include oxygen (O), sulfur (S), selenium (Se), tellurium (Te), polonium (Po), and the synthetic element livermorium (Lv). The term "chalcogen" derives from the Greek words chalkos (meaning copper or ore) and genes (meaning former or producer), highlighting the historical association of these elements with copper ore formation; it was first proposed in 1932 by German chemist Werner Fischer. These elements exhibit a clear trend of increasing metallic character down the group, transitioning from the nonmetals oxygen and sulfur at the top to the metalloids selenium and tellurium, and finally to the post-transition metal polonium./09%3A_Group_16/9.01%3A_The_Group_16_Elements-_The_Chalcogens) Livermorium, being highly radioactive and synthetic, has limited experimental data but is predicted to follow this trend toward greater metallicity. Hydrogen chalcogenides are primarily classified based on the number of chalcogen atoms in the molecule and the nature of the compound. The principal series consists of dihydrogen monochalcogenides with the general formula , where X denotes a chalcogen atom; examples include water () and hydrogen sulfide ().[4] Further classification encompasses dihydrogen dichalcogenides (), such as dihydrogen disulfide (), and higher dihydrogen polychalcogenides (, where ), known as polysulfanes or analogous polyselenanes/polytelluranes for heavier chalcogens (e.g., up to ).[5] Additional categories include ionic species like hydrosulfide ions () and radicals such as hydroxyl ().[6] This encyclopedia entry focuses exclusively on purely binary hydrogen-chalcogen compounds, excluding ternary or more complex species such as sulfuric acid ().[6] The stability of hydrogen chalcogenides tends to decrease with increasing atomic number of the chalcogen.[4]Bonding and Molecular Structure

The hydrogen chalcogenides, general formula H₂E (where E is O, S, Se, or Te), feature bent molecular geometries as described by the Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion (VSEPR) theory. Each central chalcogen atom contributes six valence electrons, forming two single bonds to hydrogen atoms while retaining two lone pairs of electrons. This arrangement corresponds to an AX₂E₂ notation, yielding a tetrahedral electron-pair geometry but a nonlinear molecular shape due to the repulsion between the lone pairs and bonding pairs, which compresses the H–E–H angle below the ideal tetrahedral value of 109.5°./09%3A_Molecular_Geometry_and_Covalent_Bonding_Models/9.02%3A_VSEPR_-_Molecular_Geometry) The H–E–H bond angles decrease progressively down the group, from 104.45° in H₂O to 92.1° in H₂S, 91° in H₂Se, and 89.5° in H₂Te. This trend results from the increasing atomic size and lower electronegativity of the heavier chalcogens, which lead to greater s-character in the bonding orbitals and reduced hybridization effects, allowing the bond angles to approach the 90° expected for pure p-orbital overlap.65.pdf) Concurrently, the E–H bond lengths increase with the size of the central atom: 95.8 pm for O–H, 134 pm for S–H, 146 pm for Se–H, and 170 pm for Te–H, reflecting weaker orbital overlap and longer covalent bonds in the heavier congeners.[7] The central chalcogen atoms adopt sp³ hybridization in these molecules, forming four equivalent sp³ hybrid orbitals that accommodate the two σ-bonding pairs to hydrogen and the two lone pairs. This hybridization model explains the tetrahedral electron arrangement and the resulting bent structure, with the lone pairs occupying hybrid orbitals that exert stronger repulsion on the bonding pairs./10%3A_Bonding_in_Polyatomic_Molecules/10.02%3A_Hybrid_Orbitals_in_Water) Intermolecular forces vary significantly across the series. In H₂O, strong hydrogen bonding predominates due to oxygen's high electronegativity, enabling effective interactions between the partially positive hydrogen atoms and lone pairs on adjacent molecules. In contrast, the heavier H₂S, H₂Se, and H₂Te rely mainly on dipole–dipole forces and London dispersion forces, as the decreased electronegativity of S, Se, and Te diminishes the polarity of the E–H bonds and prevents significant hydrogen bonding. Bond dissociation energies for the E–H bonds also decrease down the group, indicating progressively weaker bonds: approximately 463 kJ/mol for H–O, 366 kJ/mol for H–S, with further reductions for H–Se and H–Te. These values reflect the diminishing bond strength due to poorer overlap between the hydrogen 1s orbital and the larger, more diffuse valence orbitals of the heavier chalcogens.[8]Dihydrogen Monochalcogenides

Water and Its Unique Properties

Water (H₂O) exhibits distinctive physical properties that set it apart from other hydrogen chalcogenides. At standard atmospheric pressure, it melts at 0 °C and boils at 100 °C, allowing it to exist as a liquid over a wide temperature range relevant to Earth's climate.[9] Its density reaches a maximum of 1 g/cm³ at 4 °C, after which it anomalously expands upon further cooling and freezing, resulting in ice being less dense than liquid water and thus floating on its surface.[10] This expansion, which increases volume by about 9% during freezing, arises from the open tetrahedral structure formed by hydrogen bonds in the solid phase.[11] The unique properties of water stem largely from its extensive hydrogen bonding network, where each molecule can form up to four hydrogen bonds with neighboring molecules. This network contributes to water's high specific heat capacity of 4.184 J/g·K, enabling it to absorb significant thermal energy with minimal temperature change and thus moderate environmental temperatures.[12] Similarly, the cohesive forces from hydrogen bonds produce a high surface tension of approximately 72 mN/m at 25 °C, allowing phenomena such as capillary action and the support of small objects on the water surface.[13] Chemically, water displays amphoteric behavior, capable of acting as either an acid or a base depending on the reactant. It undergoes autoionization to produce hydronium (H₃O⁺) and hydroxide (OH⁻) ions, with the ion product K_w equal to 1.0 × 10^{-14} at 25 °C, establishing the pH scale for aqueous solutions.[14] The hydronium ion itself is a strong acid with a pK_a of approximately -1.7, representing the lower limit of acidity in water.[15] Water participates in key redox reactions, including oxidation to molecular oxygen (O₂) during processes like photosynthesis and electrolysis, and reduction to hydrogen gas (H₂) in electrolytic decomposition. In hydrolysis reactions, water molecules cleave chemical bonds in larger compounds, such as esters or amides, by donating a hydroxyl group and accepting a proton, facilitating metabolic breakdown in biological systems.[16][17][18] Biologically, water serves as the universal solvent for life, enabling the dissolution and transport of nutrients, ions, and metabolites essential for cellular processes, and comprising 65–90% of the mass of living organisms. Environmentally, it covers about 71% of Earth's surface, primarily as oceans, and drives the global water cycle through evaporation, condensation, precipitation, and runoff, regulating climate and sustaining ecosystems.[19][20][21] Water exists in various isotopic forms, including light water (¹H₂¹⁶O) and heavier isotopologues like deuterium oxide (²H₂O, or heavy water) and those with ¹⁸O, which influence physical properties slightly and are detailed further in discussions of isotopologues.[22]Hydrogen Sulfide, Selenide, Telluride, and Heavier Analogues

The dihydrogen monochalcogenides beyond water, namely hydrogen sulfide (H₂S), hydrogen selenide (H₂Se), and hydrogen telluride (H₂Te), exhibit physical properties that trend with increasing atomic number of the chalcogen atom, primarily due to enhanced molecular polarizability and weaker intermolecular forces compared to hydrogen bonding in water. These compounds are colorless gases at standard conditions, with boiling points rising down the group as van der Waals interactions strengthen with larger, more polarizable electron clouds. The following table summarizes key physical properties:| Compound | Boiling Point (°C) | Molecular Weight (g/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| H₂S | -60.3 | 34.08 |

| H₂Se | -41.3 | 80.98 |

| H₂Te | -2.0 | 129.62 |