Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

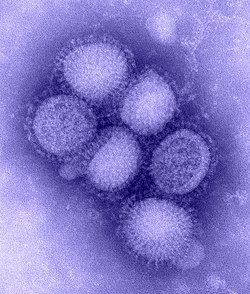

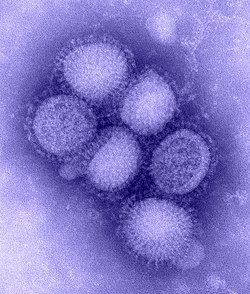

Influenza A virus subtype H1N1

View on Wikipedia

| Influenza A virus subtype H1N1 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Negarnaviricota |

| Class: | Insthoviricetes |

| Order: | Articulavirales |

| Family: | Orthomyxoviridae |

| Genus: | Alphainfluenzavirus |

| Species: | |

| Serotype: | Influenza A virus subtype H1N1

|

| Strains | |

| Influenza (flu) |

|---|

|

Influenza A virus subtype H1N1 (A/H1N1) is a subtype of influenza A virus (IAV). Some human-adapted strains of H1N1 are endemic in humans and are one cause of seasonal influenza (flu).[1] Other strains of H1N1 are endemic in pigs (swine influenza) and in birds (avian influenza).[2] Subtypes of IAV are defined by the combination of the antigenic hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N) proteins in the viral envelope; for example, "H1N1" designates an IAV subtype that has a type-1 H protein and a type-1 N protein.[3]

All subtypes of IAV share a negative-sense, segmented RNA genome.[1] Under rare circumstances, one strain of the virus can acquire genetic material through genetic reassortment from a different strain and thus evolve to acquire new characteristics, enabling it to evade host immunity and occasionally to jump from one species of host to another.[4][5] Major outbreaks of H1N1 strains in humans include the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic, the 1977 Russian flu pandemic and the 2009 swine flu pandemic, all of which were caused by strains of A(H1N1) virus which are believed to have undergone genetic reassortment.[6]

Each year, three influenza strains are chosen for inclusion in the forthcoming year's seasonal flu vaccination by the Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System of the World Health Organization (WHO). Since 1999, every annual formulation has included one strain of A/H1N1 as well as two other influenza strains – together representing strains thought most likely to cause significant human suffering in the coming season.[7][8][9]

Swine influenza

[edit]Swine influenza (also known as swine flu or pig flu) is a respiratory disease that occurs in pigs that is caused by the Influenza A virus. Influenza viruses that are normally found in swine are known as swine influenza viruses (SIVs). The three main subtypes of SIV that circulate globally are A(H1N1), A(H1N2), and A(H3N2). These subtypes are well adapted to pigs and are different from human influenza viruses of the same subtype.[10]

Swine influenza virus is common throughout pig populations worldwide. Transmission of the virus from pigs to humans is not common and does not always lead to human influenza, often resulting only in the production of antibodies in the blood. If transmission does cause human influenza, it is called zoonotic swine flu or a variant virus. People with regular exposure to pigs are at increased risk of swine flu infection. Properly cooking the meat of an infected animal removes the risk of infection.

Pigs experimentally infected with the strain of swine flu that caused the human pandemic of 2009–10 showed clinical signs of flu within four days, and the virus spread to other uninfected pigs housed with the infected ones.[11]

Incidents

[edit]1918–1920 flu pandemic

[edit]The 1918 flu was an unusually severe and deadly strain of H1N1[12] swine influenza, which killed from 17[13] to 50 or more million people worldwide over about a year in 1918 and 1920. It was one of the deadliest pandemics in human history.

The 1918 flu caused an abnormally high number of deaths, possibly due to it provoking a cytokine storm in the body.[14][15] (The H5N1 bird flu, also an Influenza A virus, has a similar effect.)[16] After the 1918 flu infected lung cells, it frequently led to overstimulation of the immune system via release of immune response-stimulating cytokines (proteins that transmit signals between cells) into the lung tissue. This leads to extensive leukocyte migration towards the lungs, resulting in the destruction of lung cells and secretion of blood and mucus into the alveoli and airways. This makes it difficult for the patient to breathe and can result in suffocation. In contrast to other pandemics, which mostly kill the old and the very young, the 1918 pandemic killed unusual numbers of young adults, which may have been due to their healthy immune systems mounting a too-strong and damaging response to the infection.[17]

The term "Spanish" flu was coined because Spain was at the time the only European country where the press were printing reports of the outbreak, which had killed thousands in the armies fighting World War I (1914–1918). Other countries suppressed the news in order to protect morale.[18]

1976 swine flu outbreak

[edit]In 1976, a novel swine influenza A (H1N1) caused severe respiratory illness in 13 soldiers, with one death at Fort Dix, New Jersey. The virus was detected only from 19 January to 9 February and did not spread beyond Fort Dix.[19] Retrospective serologic testing subsequently demonstrated that up to 230 soldiers had been infected with the novel virus, which was an H1N1 strain. The cause of the outbreak is still unknown, and no exposure to pigs was identified.[20]

1977 Russian flu

[edit]The 1977 Russian flu pandemic was caused by strain Influenza A/USSR/90/77 (H1N1). It infected mostly children and young adults under 23; because a similar strain was prevalent in 1947–57, most adults had substantial immunity.[21][22] Later analysis found that the re-emergent strain had been circulating for approximately one year before it was detected in China and Russia.[23][24] The virus was included in the 1978–79 influenza vaccine.[25][26][27][28]

2009 A(H1N1) pandemic

[edit]

In the 2009 flu pandemic, the virus isolated from patients in the United States was found to be made up of genetic elements from four different flu viruses – North American swine influenza, North American avian influenza, human influenza, and swine influenza virus typically found in Asia and Europe – "an unusually mongrelised mix of genetic sequences."[29] This new strain appears to be a result of reassortment of human influenza and swine influenza viruses, in all four different strains of subtype H1N1.

Preliminary genetic characterization found that the hemagglutinin (HA) gene was similar to that of swine flu viruses present in U.S. pigs since 1999, but the neuraminidase (NA) and matrix protein (M) genes resembled versions present in European swine flu isolates. The six genes from American swine flu are themselves mixtures of swine flu, bird flu, and human flu viruses.[30] While viruses with this genetic makeup had not previously been found to be circulating in humans or pigs, there is no formal national surveillance system to determine what viruses are circulating in pigs in the U.S.[31]

In April 2009, an outbreak of influenza-like illness (ILI) occurred in Mexico and then in the United States;[32] the CDC reported seven cases of novel A/H1N1 influenza and promptly shared the genetic sequences on the GISAID database.[33][34] With similar timely sharing of data for Mexican isolates,[35] by 24 April it became clear that the outbreak of ILI in Mexico and the confirmed cases of novel influenza A in the southwest US were related and WHO issued a health advisory on the outbreak of "influenza-like illness in the United States and Mexico".[32] The disease then spread very rapidly, with the number of confirmed cases rising to 2,099 by 7 May, despite aggressive measures taken by the Mexican government to curb the spread of the disease.[36] The outbreak had been predicted a year earlier by noticing the increasing number of replikins, a type of peptide, found in the virus.[37]

On 11 June 2009, the WHO declared an H1N1 pandemic, moving the alert level to phase 6, marking the first global pandemic since the 1968 Hong Kong flu.[38] On 25 October 2009, U.S. President Barack Obama officially declared H1N1 a national emergency.[39] The President's declaration caused many U.S. employers to take actions to help stem the spread of the swine flu and to accommodate employees and / or workflow which may have been impacted by an outbreak.[40]

A study conducted in coordination with the University of Michigan Health Service – scheduled for publication in the December 2009 American Journal of Roentgenology – warned that H1N1 flu can cause pulmonary embolism, surmised as a leading cause of death in this pandemic. The study authors suggest physician evaluation via contrast enhanced CT scans for the presence of pulmonary emboli when caring for patients diagnosed with respiratory complications from a "severe" case of the H1N1 flu.[41] H1N1 may induce other embolic events, such as myocardial infarction, bilateral massive DVT, arterial thrombus of infrarenal aorta, thrombosis of right external iliac vein and common femoral vein or cerebral gas embolism. The type of embolic events caused by H1N1 infection are summarized in a 2010 review by Dimitroulis Ioannis et al.[42]

The 21 March 2010 worldwide update, by the U.N.'s World Health Organization (WHO), states that "213 countries and overseas territories/communities have reported laboratory confirmed cases of pandemic influenza H1N1 2009, including at least 16,931 deaths."[43] As of 30 May 2010[update], worldwide update by World Health Organization (WHO) more than 214 countries and overseas territories or communities have reported laboratory confirmed cases of pandemic influenza H1N1 2009, including over 18,138 deaths.[44] The research team of Andrew Miller showed pregnant patients are at increased risk.[45] It has been suggested that pregnant women and certain populations such as native North Americans have a greater likelihood of developing a T helper type 2 response to H1N1 influenza which may be responsible for the systemic inflammatory response syndrome that causes pulmonary edema and death.[46]

On 26 April 2011, an H1N1 pandemic preparedness alert was issued by the World Health Organization for the Americas.[47] In August 2011, according to the U.S. Geological Survey and the CDC, northern sea otters off the coast of Washington state were infected with the same version of the H1N1 flu virus that caused the 2009 pandemic and "may be a newly identified animal host of influenza viruses".[48] In May 2013, seventeen people died during an H1N1 outbreak in Venezuela, and a further 250 were infected.[49] As of early January 2014, Texas health officials have confirmed at least thirty-three H1N1 deaths and widespread outbreak during the 2013/2014 flu season,[50] while twenty-one more deaths have been reported across the US. Nine people have been reported dead from an outbreak in several Canadian cities,[51] and Mexico reports outbreaks resulting in at least one death.[52] Spanish health authorities have confirmed 35 H1N1 cases in the Aragon region, 18 of whom are in intensive care.[53] On 17 March 2014, three cases were confirmed with a possible fourth awaiting results occurring at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.[54]

2012 India outbreak

[edit]With more than 300 infections and over 20 deaths, India's health ministry declared an outbreak "well under control" with "no reason to panic" in April 2012.[55]

2015 India outbreak

[edit]According to the Indian Health Ministry, 31,974 cases of swine flu had been reported and 1,895 people had died from an outbreak by mid-March.[56][57]

2017 Maldives outbreak

[edit]Maldives reported swine flu in early 2017;[58][better source needed] 501 people were tested for the disease and 185 (37%) of those tested were positive for the disease. Four of those who tested positive from these 185 died due to this disease.[59]

The total number of people who have died due to the disease is unknown. Patient Zero was never identified.[60]

Schools were closed for a week due to the disease, but were ordered by the Ministry of Education to open after the holidays even though the disease was not fully under control.[61]

2017 Myanmar outbreak

[edit]Myanmar reported H1N1 in late July 2017. As of 27 July, there were 30 confirmed cases and six people had died.[62] The Ministry of Health and Sports of Myanmar sent an official request to WHO to provide help to control the virus; and also mentioned that the government would be seeking international assistance, including from the UN, China and the United States.[63]

2017–18 Pakistan outbreak

[edit]Pakistan reported H1N1 cases mostly arising from the city of Multan, with deaths resulting from the epidemic reaching 42.[64] There have also been confirmed cases in cities of Gujranwala and Lahore.

2019 Malta outbreak

[edit]An outbreak of swine flu in the European Union member state was reported in mid-January 2019, with the island's main state hospital overcrowded within a week, with more than 30 cases being treated.[65]

2019 Morocco outbreak

[edit]In January 2019 an outbreak of H1N1 was recorded in Morocco, with nine confirmed fatalities.[66]

2019 Iran outbreak

[edit]In November 2019 an outbreak of H1N1 was recorded in Iran, with 56 fatalities and 4,000 people hospitalized.[67]

G4 virus

[edit]The G4 virus, also known as the "G4 swine flu virus" (G4) and "G4 EA H1N1", is a swine influenza virus strain discovered in China.[68] The virus is a variant genotype 4 (G4) Eurasian avian-like (EA) H1N1 virus that mainly affects pigs, but there is some evidence of it infecting people.[68] A 2020 peer-reviewed paper from the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) stated that "G4 EA H1N1 viruses possess all the essential hallmarks of being highly adapted to infect humans ... Controlling the prevailing G4 EA H1N1 viruses in pigs and close monitoring of swine working populations should be promptly implemented."[69]

Michael Ryan, executive director of the World Health Organization (WHO) Health Emergencies Program, stated in July 2020 that this strain of influenza virus was not new and had been under surveillance since 2011.[70] The Chinese CDC said it had implemented an influenza surveillance program in 2010, analyzing more than 400,000 tests annually, to facilitate early identification of influenza.[71] Of those, 13 A(H1N1) cases were detected, of which three were of the G4 variant.[71]

The study stated that almost 30,000 swine had been monitored via nasal swabs between 2011 and 2018.[69] While other variants of the virus have appeared and diminished, the study claimed the G4 variant had sharply increased since 2016 to become the predominant strain.[69][72] The Chinese Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs rebutted the study, saying that the number of pigs sampled was too small to demonstrate G4 had become the dominant strain and that the media had interpreted the study "in an exaggerated and nonfactual way".[73] They also said the infected workers "did not show flu symptoms and the test sample is not representative of the pig population in China".[71]

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said the study suggested that human infection by the G4 virus is more common than it was thought to be.[68] Both the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC)[74] and the US CDC[68] stated that, like all flu viruses with pandemic potential, the variant is a concern that will be monitored.[74] The ECDC stated that "the most important intervention in preparing for the pandemic potential of influenza viruses is the development and use of human vaccines ...".[74] Health officials (including Anthony Fauci) have said that the virus should be monitored, particularly among those in close contact with pigs, but it is not an immediate threat.[75] While there have been no reported cases or evidence of the virus outside China as of July 2020,[75] Smithsonian Magazine reported in July 2020 that scientists agree that the virus should be closely monitored, but because it "so far cannot jump from person to person", it should not be a cause for alarm yet.[76]

Infection in pregnancy

[edit]Pregnant women who contract the H1N1 infection are at greater risk of developing complications because of hormonal changes, physical changes and changes to their immune system to accommodate the growing fetus.[77] For this reason the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that those who are pregnant be vaccinated to prevent the influenza virus. The vaccination should not be taken by people who have had a severe allergic reaction to the influenza vaccination. Those who are moderately to severely ill, with or without a fever should wait until they recover before vaccination.[78]

Antiviral treatment

[edit]Pregnant women who become infected with the influenza are advised to contact their doctor immediately. Influenza can be treated with prescription antiviral medications. Oseltamivir (trade name Tamiflu) and zanamivir (Relenza) are two neuraminidase inhibitors (antiviral medications) recommended. They are most effective when taken within two days of becoming sick.[79]

Since 1 October 2008, the CDC has tested 1,146 seasonal influenza A (H1N1) viruses for resistance against oseltamivir and zanamivir. It was found that 99.6% of the samples were resistant to oseltamivir while none were resistant to zanamivir. After 2009 Influenza A (H1N1) virus samples were tested, only 4% (of 853 samples) showed resistance to oseltamivir (again, no samples showed resistance to zanamivir).[80] A study conducted in Japan during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic concluded that infants exposed to either oseltamivir or zanamivir had no short term adverse effects.[81] Both amantadine and rimantadine have been found to be teratogenic and embryotoxic (malformations and toxic effects on the embryo) when given at high doses in animal studies.[82]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Influenza A Subtypes and the Species Affected | Seasonal Influenza (Flu) | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 13 May 2024. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ Jilani TN, Jamil RT, Siddiqui AH (30 November 2020). "H1N1 Influenza". H1N1 Influenza in StatPearls. StatPearls. PMID 30020613. Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ CDC (1 February 2024). "Influenza Type A Viruses". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ Shao W, Li X, Goraya MU, Wang S, Chen JL (August 2017). "Evolution of Influenza A Virus by Mutation and Re-Assortment". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 18 (8): 1650. doi:10.3390/ijms18081650. PMC 5578040. PMID 28783091.

- ^ Eisfeld AJ, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y (January 2015). "At the centre: influenza A virus ribonucleoproteins". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 13 (1): 28–41. doi:10.1038/nrmicro3367. PMC 5619696. PMID 25417656.

- ^ Clancy, Susan (2008). "Genetics of the Influenza Virus | Learn Science at Scitable". www.nature.com. Nature Education 1(1):83. Retrieved 17 August 2024.

- ^ "Seasonal Flu Vaccines | CDC". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 12 March 2024. Retrieved 19 August 2024.

- ^ "Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS)". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- ^ Anker M, Schaaf D, World Health Organization (2000). WHO report on global surveillance of epidemic-prone infectious diseases (PDF) (Report). World Health Organization (WHO). hdl:10665/66485. WHO/CDS/CSR/ISR/2000.1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 October 2022.

- ^ "Factsheet on swine influenza in humans and pigs". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). 14 March 2023. Retrieved 17 August 2024.

- ^ "Humans May Give Swine Flu To Pigs In New Twist To Pandemic". Sciencedaily.com. 10 July 2009. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ^ "1918 Pandemic (H1N1 virus) | Pandemic Influenza (Flu) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 22 March 2020. Archived from the original on 27 March 2020. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ P. Spreeuwenberg; et al. (1 December 2018). "Reassessing the Global Mortality Burden of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic". American Journal of Epidemiology. 187 (12): 2561–2567. doi:10.1093/aje/kwy191. PMC 7314216. PMID 30202996.

- ^ Kobasa D, Jones SM, Shinya K, et al. (January 2007). "Aberrant innate immune response in lethal infection of macaques with the 1918 influenza virus". Nature. 445 (7125): 319–323. Bibcode:2007Natur.445..319K. doi:10.1038/nature05495. PMID 17230189. S2CID 4431644.

- ^ Kash JC, Tumpey TM, Proll SC, et al. (October 2006). "Genomic analysis of increased host immune and cell death responses induced by 1918 influenza virus". Nature. 443 (7111): 578–581. Bibcode:2006Natur.443..578K. doi:10.1038/nature05181. PMC 2615558. PMID 17006449.

- ^ Cheung CY, Poon LL, Lau AS, et al. (December 2002). "Induction of proinflammatory cytokines in human macrophages by influenza A (H5N1) viruses: a mechanism for the unusual severity of human disease?". Lancet. 360 (9348): 1831–1837. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11772-7. PMID 12480361. S2CID 43488229.

- ^ Palese P (December 2004). "Influenza: old and new threats". Nat. Med. 10 (12 Suppl): S82–87. doi:10.1038/nm1141. PMID 15577936. S2CID 1668689.

- ^ Barry, John M. (2004). The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Greatest Plague in History. Viking Penguin. ISBN 978-0-670-89473-4. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- ^ Gaydos JC, Top FH, Hodder RA, Russell PK (January 2006). "Swine influenza a outbreak, Fort Dix, New Jersey, 1976". Emerging Infect. Dis. 12 (1): 23–28. doi:10.3201/eid1201.050965. PMC 3291397. PMID 16494712.

- ^ "Pandemic H1N1 2009 Influenza". CIDRAP. Center for Infectious Disease Research & Policy, University of Minnesota. Archived from the original on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 30 July 2011.

- ^ "Origin of current influenza H1N1 virus". virology blog. 2 March 2009. Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ "New Strain May Edge Out Seasonal Flu Bugs". NPR. 4 May 2009. Archived from the original on 26 January 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ Nakajima, Katsuhisa; Desselberger, Ulrich; Palese, Peter (July 1978). "Recent human influenza A (H1N1) viruses are closely related genetically to strains isolated in 1950". Nature. 274 (5669): 334–339. Bibcode:1978Natur.274..334N. doi:10.1038/274334a0. PMID 672956. S2CID 4207293.

- ^ Wertheim, Joel. O. (2010). "The Re-Emergence of H1N1 Influenza Virus in 1977: A Cautionary Tale for Estimating Divergence Times Using Biologically Unrealistic Sampling Dates". PLOS ONE. 5 (6) e11184. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...511184W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011184. PMC 2887442. PMID 20567599.

- ^ "Interactive health timeline box 1977: Russian flu scare". CNN. Archived from the original on 22 March 2007.

- ^ "Invasion from the Steppes". Time magazine. 20 February 1978. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007.

- ^ "Pandemic Influenza: Recent Pandemic Flu Scares". Global Security. Archived from the original on 24 June 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2007.

- ^ "Russian flu confirmed in Alaska". State of Alaska Epidemiology Bulletin (9). 21 April 1978. Archived from the original on 27 September 2006. Retrieved 17 April 2007.

- ^ "Deadly new flu virus in US and Mexico may go pandemic". New Scientist. 26 April 2009. Archived from the original on 29 April 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2009.

- ^ Susan Watts (25 April 2009). "Experts concerned about potential flu pandemic". BBC. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (April 2009). "Swine influenza A (H1N1) infection in two children – Southern California, March–April 2009". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 58 (15): 400–402. PMID 19390508. Archived from the original on 1 October 2009. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ^ a b "Influenza-like illness in the United States and Mexico". Disease Outbreak News. World Health Organization. 24 April 2009. Archived from the original on 26 April 2009. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ^ "Viral gene sequences to assist update diagnostics for swine influenza A(H1N1)" (PDF). World Health Organization. 15 April 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ Butler, Declan (27 April 2009). "Swine flu outbreak sweeps the globe". Nature news.2009.408. doi:10.1038/news.2009.408.

- ^ "Influenza cases by a new sub-type: Regional Update". Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Epidemiological Alerts Vol. 6, No. 15. 29 April 2009. Archived from the original on 1 September 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Influenza A(H1N1) – update 19". Disease Outbreak News. World Health Organization. 7 May 2009. Archived from the original on 7 May 2009. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ^ "Efforts To Quickly Develop Swine Flu Vaccine". Science Daily. 4 June 2009. Archived from the original on 31 July 2009. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

One company, Replikins, actually predicted over a year ago that significant outbreaks of the H1N1 flu virus would occur within 6–12 months.

- ^ "H1N1 Pandemic – It's Official". 11 June 2009. Archived from the original on 15 June 2009.

- ^ "Obama declares swine flu a national emergency". The Daily Herald. 2009. Archived from the original on 29 October 2009. Retrieved 26 October 2009.

- ^ "The Arrival of H1N1 Influenza: Legal Considerations and Practical Suggestions for Employers". The National Law Review. Davis Wright Tremaine, LLP. 2 November 2009. Archived from the original on 15 October 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ^ Mollura DJ, Asnis DS, Crupi RS, et al. (December 2009). "Imaging Findings in a Fatal Case of Pandemic Swine-Origin Influenza A (H1N1)". AJR Am J Roentgenol. 193 (6): 1500–1503. doi:10.2214/AJR.09.3365. PMC 2788497. PMID 19933640.

- ^ Dimitroulis I, Katsaras M, Toumbis (October 2010). "H1N1 infection and embolic events. A multifaceted disease". Pneumon. 29 (3): 7–13. Archived from the original on 13 December 2019. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ^ "Situation updates – Pandemic (H1N1) 2009". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 2 May 2009. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ^ "Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 – update 103". Disease Outbreak News. World Health Organization. 4 June 2010. Archived from the original on 9 June 2010. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ^ "H1N1 Pandemic Flu Hits Pregnant Women Hard". Businessweek.com. 24 May 2010. Archived from the original on 5 June 2010. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ^ McAlister VC (October 2009). "H1N1-related SIRS?". CMAJ. 181 (9): 616–617. doi:10.1503/cmaj.109-2028. PMC 2764762. PMID 19858268.

- ^ "WHO Issues H1N1 Pandemic Alert". Recombinomics.com. 26 April 2011. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2011.

- ^ Rogall, Gail Moede (8 April 2014). "Sea Otters Can Get the Flu, Too". U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ^ "H1N1 flu outbreak kills 17 in Venezuela: media". Reuters. 27 May 2013. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "North Texas confirmed 20 flu deaths – Xinhua". English.news.cn. Archived from the original on 12 January 2014.

- ^ "9 deaths caused by H1N1 flu in Alberta". Cbc.ca. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ^ "Un muerto en Coahuila por influenza AH1N1". Vanguardia.com.mx. 3 January 2014. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

- ^ "Aumentan a 35 los hospitalizados por gripe A en Aragón". Cadenaser.com. 12 January 2014. Archived from the original on 12 January 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- ^ "Three cases of H1N1 reported at CAMH". Thestar.com. 21 March 2014. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ^ "India swine flu 'under control'". BBC News. 12 April 2012. Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ "Swine flu toll inches towards 1,900". The Hindu. 19 March 2015. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ Murhekar M, Mehendale S (June 2016). "The 2015 influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 outbreak in India". Indian J. Med. Res. 143 (6): 821–823. doi:10.4103/0971-5916.192077. PMC 5094123. PMID 27748308.

- ^ "Makeshift flu clinics swamped as H1N1 cases rise to 82". Maldives Independent.com. 15 March 2017. Archived from the original on 24 March 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ "Breaking: Swine flu gai Ithuru meehaku maruve, ithuru bayaku positive vejje". Mihaaru.com. 25 March 2017. Archived from the original on 25 March 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ "H1N1 death toll rises to three". Maldives Independent.com. 21 March 2017. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ "Schools to open after flu outbreak". Maldives Independent.com. 23 March 2017. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ Lone, Wa; Lewis, Simon (27 July 2017). "Myanmar tracks spread of H1N1 as outbreak claims sixth victim". Reuters. Archived from the original on 11 December 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ Htet Naing Zaw (27 July 2017). "Myanmar Asks WHO to Help Fight H1N1 Virus". The Irrawaddy. Archived from the original on 28 August 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ "Toll rises to 42 as 3 more succumb to swine flu". The Nation. 24 January 2018. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ Caruana, Claire; Xuereb, Matthew (18 January 2019). "Swine flu outbreak at Mater Dei hospital, St Vincent de Paul". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 16 August 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ "Swine flu outbreak kills 9 in Morocco". Al Arabiya. AFP. 2 February 2019. Archived from the original on 16 August 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ "آنفولانزا و راههای درمان آن را بشناسید" [Learn about the flu and how to treat it]. yjc.ir (in Persian). Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d "CDC takes action to prepare against 'G4' swine flu viruses in China with pandemic potential" (Press release). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2 July 2020. Archived from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ a b c Sun H, Xiao Y, Liu J, et al. (29 June 2020). "Prevalent Eurasian avian-like H1N1 swine influenza virus with 2009 pandemic viral genes facilitating human infection". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (29): 17204–17210. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11717204S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1921186117. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 7382246. PMID 32601207.

- ^ "Recently publicized swine flu not new, under surveillance since 2011: WHO expert". Xinhuanet. 2 July 2020. Archived from the original on 3 July 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ a b c "The swine flu virus is not a new virus and does not very spread and is pathogenic to humans and animals [translated from Chinese]". Ministry of Agriculture of the People's Republic of China. 2020. Archived from the original on 20 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020. Translation via "Eurasian avian-like A(H1N1) swine influenza viruses" (PDF). European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 13 July 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ Cohen, Jon (29 June 2020). "Swine flu strain with human pandemic potential increasingly found in pigs in China". Science. doi:10.1126/science.abd5761. S2CID 225687803.

- ^ "China says G4 swine flu virus not new; does not infect humans easily". Reuters. 4 July 2020. Archived from the original on 4 July 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- ^ a b c "Eurasian avian-like A(H1N1) swine influenza viruses" (PDF). European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 13 July 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ a b Garcia de Jesus E (2 July 2020). "4 reasons not to worry about that 'new' swine flu in the news". Science News. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ Machemer T (6 July 2020). "New Swine flu strain with pandemic potential isn't cause for alarm". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 11 July 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ Boon, Lim (23 September 2011). "Influenza A H1N1 2009 (Swine Flu) and Pregnancy". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of India. 61 (4): 389–393. doi:10.1007/s13224-011-0055-2. PMC 3295877. PMID 22851818.

- ^ "Key Facts about Seasonal Flu Vaccine". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ "What You Should Know About Flu Antiviral Drugs". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 23 January 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ "2008–2009 Influenza Season Week 32 ending 15 August 2009". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ^ Saito, S; Minakami, H; Nakai, A; Unno, N; Kubo, T; Yoshimura, Y (August 2013). "Outcomes of infants exposed to oseltamivir or zanamivir in utero during pandemic (H1N1) 2009". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 209 (2) e1-9. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.04.007. PMID 23583838.

- ^ "Pandemic OBGYN". Sarasota Memorial Health Care System. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

External links

[edit]- Influenza Research Database Database of influenza genomic sequences and related information.

- Centers For Disease Control and Prevention H1N1 Flu (Swine Flu).

- H1N1 Flu, 2009: Hearings before the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, United States Senate, of the One Hundred Eleventh Congress, First Session: 29 April 2009, Coordinating the Federal Response; 21 September 2009, Protecting Our Community: Field Hearing in Hartford, CT; 21 October 2009, Monitoring the Nation's Response; 17 November 2009, Getting the Vaccine to Where It is Most Needed.

Influenza A virus subtype H1N1

View on GrokipediaVirology and Classification

Genomic Structure and Replication

The genome of influenza A virus subtype H1N1 consists of eight linear, single-stranded, negative-sense RNA segments, encapsidated by nucleoprotein (NP) and associated with the heterotrimeric viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) comprising PB2, PB1, and PA subunits to form viral ribonucleoprotein complexes (vRNPs).[12] These segments total approximately 13,500 nucleotides across strains such as A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (H1N1), with each encoding specific viral proteins: segment 1 (PB2, polymerase basic 2); segment 2 (PB1, polymerase basic 1, plus the accessory protein PB1-F2 via alternative reading frame); segment 3 (PA, polymerase acidic); segment 4 (HA, hemagglutinin subtype H1); segment 5 (NP); segment 6 (NA, neuraminidase subtype N1); segment 7 (M1, matrix protein 1, and M2, matrix protein 2 ion channel via splicing); and segment 8 (NS1, non-structural protein 1, and NS2/NEP, nuclear export protein via splicing).[13] The H1 HA and N1 NA genes confer subtype specificity, enabling receptor binding to α-2,6-linked sialic acids predominant in human upper respiratory epithelia.[13] Replication initiates with virion attachment to host sialic acid-containing receptors via HA trimers on the viral envelope, followed by clathrin-mediated endocytosis into endosomes.[14] Endosomal acidification (pH ~5.0–6.0) triggers conformational change in HA, facilitating fusion of viral and endosomal membranes, while M2 proton channels acidify the virion interior to disrupt M1-NP interactions and release vRNPs into the cytoplasm for nuclear import via NP nuclear localization signals and importin-α/β.[14] In the nucleus, primary transcription by the RdRp produces capped, polyadenylated viral mRNAs through cap-snatching—stealing 5' cap structures from nascent host pre-mRNAs via PB2 cap-binding and PB1 endonuclease activity—enabling cytoplasmic translation of viral proteins, including new polymerase subunits that amplify transcription.[14] Genome replication proceeds via synthesis of full-length, positive-sense complementary RNAs (cRNAs) from vRNA templates, which serve as replicative intermediates for asymmetric production of new negative-sense vRNAs; this polymerase switching from transcription to replication requires accumulating NP to prevent mRNA synthesis and involves panhandle structures formed by complementary termini of vRNA/cRNA for circularization and polymerase re-entry.[14] Unlike transcription, replication does not require priming, yielding uncapped vRNAs that encapsidate with NP and RdRp to form progeny vRNPs.[14] Progeny vRNPs are exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm via NS2/NEP-mediated recruitment of the cellular CRM1 exportin pathway, associating with M1 at the plasma membrane where HA and NA are trafficked via Golgi.[14] Virion assembly involves selective packaging of one copy of each of the eight vRNPs into the envelope-embedded M1 lattice, driven by segment-specific packaging signals at vRNA termini that promote higher-order interactions; budding occurs at lipid rafts enriched in HA and NA, with M2 facilitating scission and NA enzymatically cleaving sialic acids to release nascent virions and prevent aggregation.[14] The entire cycle completes in 6–8 hours per infected cell, yielding 10^3–10^4 virions, with nuclear localization distinguishing influenza A replication from cytoplasmic RNA viruses.[14]Antigenic Properties and Evolution

The antigenic properties of influenza A H1N1 viruses are governed by their hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) surface glycoproteins, which elicit the primary humoral immune response. HA, responsible for receptor binding and membrane fusion, features a globular head domain with five major antigenic sites—Sa, Sb, Ca1, Ca2, and Cb—that are hotspots for neutralizing antibody binding.[15] These sites, comprising hypervariable loops, undergo frequent amino acid substitutions under selective pressure from host immunity, altering epitope recognition without abolishing receptor specificity. NA, which cleaves sialic acid to release progeny virions, also harbors antigenic epitopes, though HA mutations dominate observed antigenic variation.[16] Antigenic evolution in H1N1 proceeds via two mechanisms: gradual antigenic drift through point mutations in HA and NA genes, and abrupt antigenic shift via reassortment of genomic segments with other influenza subtypes. Drift accumulates substitutions, such as those at HA positions 156, 159, and 189, enabling immune escape and necessitating annual vaccine updates; for instance, post-2009 H1N1pdm09 strains evolved into clades like 6B.1A with changes including T135K and I295V, reducing cross-reactivity with prior variants by up to fourfold in hemagglutination inhibition assays.[17][18] Shift, exemplified by the 2009 pandemic strain's emergence from a triple reassortant swine virus incorporating North American avian, swine, and human genes with Eurasian swine NA and M segments, introduces novel HA subtypes to immunologically naive populations, facilitating pandemics.[17][19] Phylogenetic analyses reveal H1N1's evolutionary trajectory as constrained by functional constraints on HA's receptor-binding pocket and stem domain, with antigenic changes clustering in the head to balance immune evasion and transmissibility. From 2009 to 2023, H1N1pdm09 diversified into approximately five antigenic clusters, driven by epistatic interactions among substitutions that preserve glycan shielding and receptor affinity.[20] This co-evolution of antigenic and molecular traits underscores the virus's adaptation to human hosts, with swine serving as a mixing vessel amplifying reassortant potential.[21] Surveillance data indicate that while drift predominates in seasonal circulation, shifts remain a latent risk, particularly from zoonotic reservoirs.[18]Key Variants and Reassortants

The Influenza A virus subtype H1N1 has evolved through repeated reassortment events, generating distinct lineages that have circulated in humans and swine populations. Reassortment, a form of antigenic shift, occurs when two different influenza viruses co-infect a host cell, allowing packaging of novel combinations of the eight genomic RNA segments. These events have been pivotal in the emergence of pandemic strains and enzootic variants.[22] The 1918 pandemic H1N1 virus resulted from a reassortment event circa 1915, where a preexisting human H1 hemagglutinin (HA) gene, likely derived from an avian source after 1901, combined with seven avian-origin segments including neuraminidase (NA) and internal protein genes, possibly from an H7N1 avian virus. This reassortant virus adapted to mammals, causing the deadly Spanish flu pandemic and establishing lineages in both human seasonal circulation (until 1957) and swine as the classical H1N1 strain. The classical swine H1N1 lineage traces directly to the 1918 virus, maintaining genetic continuity with minimal reassortment for decades.[23][24] In 1977, an H1N1 variant antigenically and genetically resembling human strains from the early 1950s re-emerged in China and spread globally, known as the Russian flu despite primarily affecting younger populations with prior immunity gaps. Genetic analysis reveals 98.4% HA identity to 1948–1951 isolates, with only four amino acid differences, suggesting derivation from a frozen laboratory stock rather than natural reassortment or evolution. No evidence of reassortment with contemporary strains was identified in this event.[25] Swine populations have served as reservoirs for H1N1 reassortants, notably the triple-reassortant (TR) H1N1 viruses that emerged in North America around 1998. These incorporated HA and NA from classical swine H1N1, with internal genes reassorted from avian (PB2, PA), human H3N2 (PB1), and classical swine origins, enabling enhanced replication and transmission in pigs. This TR backbone facilitated further reassortments, contributing to zoonotic risks.[26][27] The 2009 pandemic A(H1N1)pdm09 virus exemplifies a complex reassortant, arising in swine from co-circulating North American TR and Eurasian avian-like H1N1 lineages. Its genome comprises segments from multiple sources, as detailed below:| Gene Segment | Origin |

|---|---|

| HA | Eurasian swine H1N1 (avian-like) |

| NA | North American classical swine H1N1 (via TR) |

| PB2 | North American avian (via TR) |

| PB1 | North American swine H3N2 (human-derived, via TR) |

| PA | North American avian (via TR) |

| NP | North American classical swine H1N1 (via TR) |

| M | Eurasian swine H1N1 |

| NS | North American classical swine H1N1 (via TR) |

Historical Context and Major Pandemics

Pre-20th Century Origins

The hemagglutinin (HA) H1 subtype of influenza A viruses traces its phylogenetic origins to avian reservoirs, where influenza A has circulated for millennia among wild aquatic birds. Molecular clock analyses estimate that divergences among HA subtypes, including H1 from H2 and H3, occurred several hundred to several thousand years ago, reflecting long-term evolution in avian hosts driven by antigenic drift and host immune pressures.[30] These ancient avian H1 genes represent the foundational precursors to mammalian H1 lineages, with genetic diversity shaped by periodic reassortment events in bird populations.[31] No direct virological or serological evidence confirms circulation of H1N1 viruses in humans prior to the early 20th century. Historical accounts of influenza-like illnesses exist from antiquity, such as outbreaks described by Hippocrates around 412 BCE and epidemics in Europe during the 16th–19th centuries (e.g., 1510, 1557, 1580, 1675, 1732–1733, 1782, and 1830–1833), but retrospective subtyping is impossible without viral isolates, and these were likely caused by other influenza A subtypes or non-influenza pathogens based on phylogenetic reconstructions of known strains.[3] The absence of documented swine influenza before 1918 further suggests that pre-20th century zoonotic spillovers, if any, did not establish sustained H1N1 transmission in pigs or humans.[3] Genetic studies of the 1918 pandemic H1N1 progenitor indicate that a mammal-adapted H1 HA lineage arose shortly before that event, with molecular dating placing the emergence of a human H1 virus precursor around 1900–1907, followed by acquisition of avian neuraminidase (N1) and polymerase genes.[23] This timeline implies that any pre-1900 H1 incursions into mammals were either extinct, subclinical, or undetected, as no archived sequences or epidemiological signatures link H1N1 directly to 19th-century human outbreaks. Shared ancestry between human and classical swine H1N1 is estimated at 1912–1918, postdating 19th-century records.[32] Thus, while the H1 subtype's deep evolutionary roots predate human civilization, the specific H1N1 configurations pathogenic to humans originated in the avian-mammalian interface of the early 1900s.[33]1918–1920 Flu Pandemic

The 1918 influenza pandemic was caused by an H1N1 subtype of influenza A virus with genes of avian origin, marking it as the most severe pandemic in recorded history.[5] It resulted in an estimated 50 million deaths worldwide, with figures ranging up to 100 million in some analyses, including approximately 675,000 fatalities in the United States.[34] [35] The virus exhibited unusual virulence, particularly affecting young adults aged 20–40 years, leading to a W-shaped mortality curve rather than the typical U-shape dominated by infants and the elderly.[36] This pattern stemmed from the virus's ability to trigger hypercytokinemia, or cytokine storm, in robust immune systems.[36] The pandemic emerged in three waves from spring 1918 to early 1920. The initial mild wave appeared in March 1918, with over 100 soldiers falling ill at Camp Funston, Fort Riley, Kansas, on March 11, shortly after the arrival of new recruits.[37] A second, deadlier wave struck in August–September 1918, spreading rapidly from military camps to civilian populations across the United States and Europe, exacerbated by World War I troop mobilizations and global shipping.[38] By October 1918, the virus had reached peak lethality in the U.S., claiming an estimated 195,000 American lives that month alone.[37] A third wave in early 1919 further prolonged the outbreak before subsiding.[39] Evidence points to the virus's origin in Haskell County, Kansas, as early as January 1918, based on contemporaneous medical reports of localized outbreaks in this rural area before amplification at nearby military bases.[40] Phylogenetic analysis of reconstructed viral genomes supports an avian progenitor that adapted to humans, with no direct swine intermediary required, though debates persist on precise zoonotic pathways.[3] The name "Spanish flu" arose from Spain's uncensored press reporting during wartime neutrality, despite the virus not originating there.[39] Confirmation of the H1N1 subtype came from genomic reconstruction efforts using preserved autopsy tissues from 1918 victims, including lung samples from Alaskan Inuit buried in permafrost.[34] These efforts, completed by 2005, revealed the full eight-segment genome, showing adaptations like enhanced polymerase activity and hemagglutinin cleavage that enabled efficient human airway infection and evasion of innate immunity.[41] Recent sequencing of European samples from 1918 further corroborates genomic stability with minor local variants, underscoring the virus's capacity for rapid dispersal via human vectors.[42]2009 A(H1N1)pdm09 Pandemic

In March 2009, the novel influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus, a quadruple reassortant containing genes from North American swine, Eurasian swine, avian, and human influenza viruses, emerged and began circulating in humans.[7] The first laboratory-confirmed cases were identified in Mexico by late March, with initial reports of severe illness and deaths among young adults prompting heightened surveillance.[43] By April 2009, cases were reported in the United States, with the virus rapidly spreading through human-to-human transmission via respiratory droplets, facilitated by international travel.[7] On April 25, 2009, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a public health emergency of international concern due to the virus's potential for pandemic spread, escalating to phase 6 (pandemic) on June 11, 2009, after sustained transmission in multiple countries.[44] Global surveillance estimated 43,000 to 89,000 laboratory-confirmed cases and over 3,900 deaths by July 6, 2009, though underreporting was significant due to limited testing capacity.[45] Retrospective modeling indicated the virus infected 11% to 21% of the global population, with excess respiratory mortality ranging from 151,700 to 575,400 deaths worldwide in 2009, disproportionately affecting individuals under 65 years old—unlike seasonal influenza, which primarily burdens the elderly.[46][47] The case-fatality ratio was estimated at 0.02% to 0.4%, lower than the 1918 pandemic's 2.5% but contributing to excess mortality in younger, healthier populations, including pregnant women and those with obesity or underlying conditions.[48][45] Public health responses included antiviral stockpiling (e.g., oseltamivir), social distancing measures, and accelerated vaccine development; monovalent vaccines were licensed in the United States by the FDA on September 15, 2009, following clinical trials showing immunogenicity similar to seasonal vaccines.[2] In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported over 60 million illnesses, 274,000 hospitalizations, and 12,469 deaths attributable to the virus by August 2010, with vaccination coverage reaching about 20% of the population.[49] The pandemic wave peaked in October-November 2009 in the Northern Hemisphere, subsiding by mid-2010 as population immunity increased and the virus integrated into seasonal circulation patterns.[7] WHO downgraded the pandemic status on August 10, 2010, noting the virus's transition to a seasonal strain, though it continued to cause annual epidemics with varying severity.[50] Empirical data highlighted the virus's lower overall lethality compared to historical pandemics but underscored vulnerabilities in non-elderly groups, informing future preparedness for reassortant influenza threats.[46][51]Other Notable Outbreaks

1976 Swine Flu Outbreak

In January 1976, an outbreak of respiratory illness occurred among U.S. Army recruits training at Fort Dix, New Jersey, with reports of a large number of cases emerging by mid-month.[52] Laboratory analysis by the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research identified the causative agent as a novel influenza A virus strain, designated A/New Jersey/76 (Hsw1N1), which exhibited antigenic similarity to the 1918 pandemic virus based on serological testing.[53] The outbreak affected over 200 individuals, resulting in 13 cases of severe respiratory disease and one death from influenza pneumonia in a previously healthy 19-year-old recruit, Private David Lewis, who collapsed during a forced march on February 4.[53] [3] Despite evidence of limited person-to-person transmission within the military base, the virus did not spread beyond Fort Dix to the civilian population or other military installations, as confirmed by subsequent surveillance.[54] The isolation of this swine-origin H1N1 strain prompted alarm among public health officials due to its serological cross-reactivity with the 1918 virus, which had caused an estimated 50 million deaths worldwide, raising fears of a potential repeat pandemic in the absence of population immunity to H1N1 subtypes since 1957.[55] On February 13, 1976, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was notified, leading to collaborative virological confirmation and a World Health Organization consultation in March that recommended vaccine production against the A/New Jersey/76 strain.[52] CDC Director David Sencer advocated for a precautionary national immunization program, citing the 1918 precedent and the virus's zoonotic origin from swine reservoirs, though critics later noted that the strain's transmissibility was inefficient and its pathogenicity overstated relative to historical pandemics.[55] [54] In response, President Gerald Ford announced on March 24, 1976, a plan for a nationwide vaccination campaign targeting the entire U.S. population of approximately 215 million, formalized as the National Influenza Immunization Program (NIIP) with $135 million in emergency funding approved by Congress in April.[56] Vaccine manufacturers, including Merck and major pharmaceutical firms, produced monovalent H1N1 vaccines adjuvanted with preservatives like thimerosal and formaldehyde-inactivated whole virus, with clinical trials demonstrating adequate immunogenicity but variable neuraminidase content across lots.[57] Rollout began in October 1976 after resolving manufacturer liability concerns via federal indemnity, achieving vaccination of about 40 million civilians and military personnel by December, though logistical challenges and public hesitancy limited coverage to roughly 20-25% of the target population.[3] [58] No widespread pandemic materialized, with only sporadic, contained detections of the A/New Jersey/76 strain in swine and rare human cases thereafter, underscoring the outbreak's limited epidemic potential despite initial concerns.[53] The program encountered setbacks from unrelated influenza activity misattributed to swine flu and, critically, reports of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), a rare autoimmune neuropathy, emerging in late November 1976 among vaccine recipients.[55] CDC surveillance identified an excess risk of approximately 1 additional GBS case per 100,000 vaccinations, totaling an estimated 450-530 excess cases linked to the campaign, with symptoms typically appearing 2-3 weeks post-vaccination and a case-fatality rate of about 5% in affected individuals.[59] [55] This led to a temporary halt on December 16, 1976, and eventual suspension of the NIIP, prompting congressional investigations that criticized the decision-making process for insufficient evidence of imminent threat and overreliance on historical analogies, though proponents defended it as prudent risk mitigation given the unknowns of emerging zoonotic strains.[56] [55] The episode highlighted challenges in balancing preparedness against false alarms, influencing future pandemic response frameworks to emphasize surveillance over preemptive mass interventions.[55]1977 Russian Flu Re-emergence

The 1977 re-emergence of the H1N1 influenza A virus, known as the Russian flu, involved the sudden return of a strain antigenically and genetically similar to those circulating globally between 1947 and 1957, after an absence of over two decades.[60][61] The virus was first isolated in May 1977 among military recruits in northern China, near Tientsin, before spreading northward into the Soviet Union by late summer.[62] By November 1, 1977, the Soviet Union reported an index case in a 22-year-old man in Moscow, prompting official notification to the World Health Organization on December 7, 1977.[63][64] Genetic sequencing revealed that the 1977 H1N1 strain exhibited minimal nucleotide evolution compared to 1950s isolates, lacking the expected accumulation of mutations over 20 years, which indicated it derived directly from preserved laboratory stocks rather than natural reassortment or animal reservoirs.[61][65] This antigenic conservation meant the virus closely resembled human H1N1 variants from the early 1950s, enabling partial immunity in adults over 25–30 years old who had prior exposure, thus restricting severe cases predominantly to younger populations born after 1957.[66][67] Epidemiologically, the outbreak manifested as a mild epidemic with rapid transmission in closed settings like schools and military bases, spreading globally by early 1978 but without the excess mortality typical of true pandemics.[66] In the Soviet Union, it affected primarily individuals under 25, with an estimated attack rate of around 7% in affected younger cohorts through mid-January 1978.[66] Overall mortality remained low, with clinical severity comparable to seasonal influenza and fewer complications in vulnerable groups due to the strain's attenuated virulence profile.[60][68] The prevailing explanation for the re-emergence attributes it to a laboratory accident, likely during influenza research or live vaccine trials in China, where the virus escaped containment and seeded human transmission.[65][68] Supporting evidence includes the virus's phylogenetic clustering with archived lab strains and its simultaneous appearance in multiple distant locations without intermediate animal hosts, inconsistent with natural zoonotic spillover.[63][62] This event, occurring amid heightened global vaccine research following the 1976 swine flu alert, underscores risks of handling historical pathogens but did not prompt widespread policy changes at the time.[62]Post-2009 Regional Outbreaks

Following the declaration of the post-pandemic phase by the World Health Organization on August 10, 2010, the A(H1N1)pdm09 virus integrated into seasonal influenza circulation, contributing to annual epidemics with varying regional intensity rather than global waves. In temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere, activity typically peaked in winter months, while tropical areas like parts of Asia experienced year-round transmission with episodic surges. Surveillance data indicated patterns of low circulation ("skip years") followed by resurgence, particularly for A(H1N1)pdm09 between 2011 and 2013 in Europe and Eastern Asia, where initial post-pandemic waves gave way to reduced activity before renewed dominance.[69] The 2010–2011 influenza season marked an early post-pandemic example of heightened regional severity, with A(H1N1)pdm09 overrepresented among hospitalized patients experiencing critical illness compared to influenza A(H3N2) or B viruses. In the United States, influenza activity peaked in early February 2011, with laboratory-confirmed cases showing pH1N1 associated with 27 pediatric deaths and increased hospitalization rates among those with underlying conditions.[70] European surveillance similarly reported disproportionate severe cases linked to A(H1N1)pdm09 during the 2011–2012 season across multiple countries, reflecting viral adaptations and waning population immunity.[71] A prominent regional outbreak occurred in India during the 2014–2015 winter, where A(H1N1)pdm09 caused over 30,000 laboratory-confirmed cases and approximately 2,000 deaths nationwide by mid-2015, with clusters in states including Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Delhi.[72] [73] This surge, exceeding prior post-pandemic activity in the country, was driven by rapid community spread and limited antiviral access, affecting adults aged 20–39 disproportionately and straining healthcare resources in urban centers. Genetic analyses of circulating strains revealed minor antigenic drift but retained pandemic-era markers of transmissibility.[74] Subsequent seasons saw sporadic regional elevations, such as the predominance of A(H1N1)pdm09 in the United States during 2023–2024, which included a second wave of activity and elevated hospitalizations, though not classified as outbreak-level by CDC thresholds. In Asia, off-season surges in 2025, including Japan and India, involved H1N1 strains amid broader influenza rises, potentially linked to climatic factors and travel, but lacked the mortality scale of 2015. These events underscore the virus's capacity for localized epidemics through antigenic evolution and immunity gaps, prompting targeted vaccination campaigns in affected regions.[75] [76]Zoonotic Transmission and Swine Reservoirs

Origins in Swine Populations

The classical swine H1N1 influenza A virus lineage emerged through the adaptation of the 1918 human pandemic H1N1 strain in pig populations shortly after the outbreak, marking the first documented establishment of this subtype in swine.[3] Concurrent respiratory disease outbreaks in United States swine herds during the 1918–1919 human pandemic provided early evidence of this zoonotic transfer, with the virus likely spilling over from infected humans to pigs, where it became enzootic.[77] Genetic analyses confirm that the swine-adapted virus retained core features of the human 1918 strain, including its hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) genes, enabling persistent circulation without significant antigenic drift for decades.[24] The first isolation of H1N1 from swine occurred in 1930 in the United States, solidifying the recognition of pigs as a reservoir for this subtype.[3] This classical lineage dominated North American swine populations for nearly 60 years, characterized by genetic stability and low pathogenicity in pigs compared to human strains, though it occasionally caused mild respiratory illness.[78] Phylogenetic studies trace its evolutionary continuity back to the 1918 event, distinguishing it from later reassortants by its lack of significant gene segment exchanges until the late 1990s.[79] Independently, an avian-origin H1N1 lineage, termed "avian-like," entered European swine populations around 1979, originating from wild birds and adapting without initial human intermediacy.[80] This strain diverged antigenically from the classical North American lineage, reflecting regional differences in viral ecology and host adaptation.[24] Both lineages underscore pigs' role as susceptible hosts due to their expression of both α-2,6-linked (human-preferred) and α-2,3-linked (avian-preferred) sialic acid receptors on respiratory epithelial cells, facilitating initial colonization and subsequent maintenance.[81] These origins highlight swine as long-term reservoirs, with sporadic human-to-swine spillovers reinforcing diversity, as seen in post-2009 introductions of pandemic H1N1 segments into global pig herds.[82]G4 Eurasian Avian-Like Strain

The G4 genotype Eurasian avian-like H1N1 swine influenza virus emerged through reassortment events involving the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase genes of avian origin Eurasian avian-like H1N1 strains with internal genes derived from the 2009 pandemic H1N1 virus and triple-reassortant lineages, initially detected in Chinese pigs around 2010 but rapidly expanding after 2016.[83][84] By 2018, this genotype accounted for over 50% of H1N1 detections in pigs across multiple Chinese provinces, displacing prior dominant strains through enhanced transmissibility in swine populations.[83] Genetic analyses reveal adaptive mutations in the hemagglutinin protein that improve binding to human-type sialic acid receptors, facilitating mammalian host adaptation.[84][85] In swine reservoirs, the virus exhibits high prevalence, with surveillance data from 2011–2018 indicating its dominance in eastern and central China, often co-circulating with other subtypes like H3N2, leading to further reassortants.[83] Experimental infections demonstrate efficient replication and shedding in pigs, comparable to endemic strains, underscoring its establishment as a stable lineage.[84] The internal genes, originating from human pandemic strains during 2009–2010, evolve at higher rates, potentially enhancing antigenic drift and evasion of immunity.[85] Zoonotic spillover has been documented through serological surveys, revealing antibodies against G4 strains in 4.4% of swine workers versus 0.4% in the general population in China from 2015–2018, indicating occupational exposure risks.[83] The first confirmed human infection occurred in 2019 in Yunnan Province, involving a virus isolate with 99.7% homology to contemporaneous swine strains, though no sustained human-to-human transmission was observed.[84] In vitro and ferret model studies show enhanced replication in human airway epithelia and limited airborne transmission, but with receptor-binding preferences shifting toward human cells, raising concerns for pandemic potential if additional adaptations occur.[84][86] Public health assessments classify G4 EA H1N1 as a candidate for vaccine inclusion due to its prevalence and zoonotic markers, with calls for enhanced swine surveillance in Asia to monitor reassortment with human or avian viruses.[87] No widespread human outbreaks have been reported as of 2025, but its circulation in dense pig farming regions amplifies spillover risks.[85]Pathogenesis and Clinical Features

Viral Entry and Immune Response

The hemagglutinin (HA) surface glycoprotein of human H1N1 influenza A viruses preferentially binds to sialic acid residues attached via α2,6-linkages to galactose on glycoconjugates of respiratory epithelial cells, enabling initial attachment primarily in the upper human airway.[88] This specificity distinguishes human-adapted H1N1 strains, such as the 2009 pandemic variant, from avian influenza viruses that favor α2,3-linkages, though the 1918 H1N1 strain exhibited dual binding capability to both linkage types, contributing to its broader tissue tropism including the lower respiratory tract.[88] [89] Neuraminidase (NA) supports entry indirectly by cleaving sialic acids to prevent viral aggregation and facilitate mucus penetration.[90] Following receptor engagement, the virus undergoes clathrin-mediated endocytosis or, less commonly, macropinocytosis, forming an endocytic vesicle that traffics inward.[90] Acidification of the endosome to approximately pH 5.0–6.0 triggers a conformational rearrangement in HA, exposing its fusion peptide and driving hemifusion followed by complete pore formation between viral and endosomal membranes; this process releases the viral genome as ribonucleoprotein complexes into the host cytoplasm.[90] Concurrently, the M2 proton channel equilibrates pH within the virion interior, promoting dissociation of the matrix protein M1 from the genome for uncoating.[90] Proteolytic activation of HA by host proteases like TMPRSS2 at the cell surface or in endosomes is essential for fusion competence in H1N1 strains.[90] Innate immune recognition of H1N1 viral RNA occurs via cytosolic RIG-I and endosomal TLRs/7/8, rapidly inducing type I interferons (IFN-α/β) from infected epithelial cells, plasmacytoid dendritic cells, and macrophages, which establish an antiviral state through interferon-stimulated genes and recruit natural killer cells for early cytotoxicity.[91] Pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-18 are secreted, amplifying inflammation but risking vascular leakage and edema if dysregulated.[91] [92] Adaptive responses emerge within days, with CD4+ T helper cells coordinating B-cell production of neutralizing IgG antibodies targeting HA and NA to block entry and release, while CD8+ cytotoxic T cells eliminate infected cells via perforin/granzyme pathways.[91] Severe H1N1 pathogenesis, as in the 1918 and 2009 pandemics, often involves a hyperinflammatory "cytokine storm" where NLRP3 inflammasome activation and unchecked type I IFN/TNF-α/IL-6 responses cause excessive lung immunopathology, endothelial damage, and acute respiratory distress syndrome, disproportionately affecting young adults with robust immunity in 1918 due to amplified innate signaling.[92] [93] Elevated IL-17 and delayed viral clearance exacerbate this in 2009 cases, with host factors like obesity impairing resolution.[92] Reconstruction studies of 1918 H1N1 confirm its induction of higher proinflammatory profiles compared to seasonal strains, underscoring viral determinants in immune overreaction.[92]Symptoms and Complications

The symptoms of Influenza A virus subtype H1N1 infection typically manifest abruptly and resemble those of seasonal influenza, including high fever (often above 38°C), cough, sore throat, rhinorrhea or nasal congestion, muscle aches (myalgia), headache, chills, and profound fatigue.[94][2] Gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea occur more frequently with H1N1 than with some other subtypes, particularly in children, affecting up to 25-30% of cases during the 2009 pandemic.[95][45] In young children, additional signs may include irritability, dehydration from poor oral intake, and lethargy, sometimes progressing to shock or seizures in severe presentations.[45] Complications arise primarily from respiratory involvement and are more severe in H1N1 than in typical seasonal strains, with primary viral pneumonia or secondary bacterial superinfections (e.g., by Streptococcus pneumoniae or Staphylococcus aureus) leading to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and respiratory failure in approximately 10-20% of hospitalized cases during the 2009 outbreak.[2][96] Exacerbation of underlying conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma, increases hospitalization risk, while rare systemic effects include myocarditis, encephalitis, or multi-organ dysfunction, contributing to a case fatality rate of 0.01-0.1% overall but higher (up to 4-5%) in critically ill patients requiring mechanical ventilation.[97][98] Neurological complications, reported in about 1-2% of hospitalized individuals, range from confusion and Guillain-Barré syndrome to transverse myelitis, though causality remains debated beyond temporal association.[99][100]Infection in Vulnerable Populations

Pregnant women faced markedly elevated risks during the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, with an odds ratio of 22.4 (95% CI 9.2–54.5) for hospitalization compared to non-pregnant adults of reproductive age.[101] Among reported cases in the United States, 65.9% of pregnant women with confirmed H1N1 were hospitalized, and 22.6% of those required intensive care unit admission; pregnant women accounted for approximately 5% of total U.S. H1N1-related deaths despite comprising about 1% of the population.[102] Common complications included preterm birth (30.2% of live births with known gestational age) and underlying conditions such as asthma (22.9%) and obesity (13.0%).[102] Obesity independently increased the likelihood of severe outcomes in H1N1 infection, particularly among adults under 60 years. In a study of over 9,000 hospitalized patients in China, obesity (BMI ≥28 kg/m²) yielded an odds ratio of 1.91 (95% CI 1.57–2.31) for severe illness in ages 18–59, with higher prevalence among severe cases (19%) than non-severe (14%).[103] This association persisted after adjusting for confounders like age and comorbidities, linking adiposity to impaired immune responses and prolonged viral shedding.[103] Individuals with chronic conditions exhibited heightened vulnerability, including chronic lung disease (odds ratio 6.6, 95% CI 3.8–11.6), diabetes (3.8, 95% CI 2.2–6.5), and heart disease (2.3, 95% CI 1.2–4.1) for hospitalization.[101] Immunosuppression conferred an odds ratio of 5.5 (95% CI 2.8–10.9).[101] Young children under 5 years and those with asthma requiring medication (odds ratio 4.3, 95% CI 2.7–6.8) also faced increased hospitalization risks, though overall pediatric mortality remained low relative to adults.[101] In contrast to seasonal influenza, where elderly individuals over 65 bear the highest burden, the 2009 H1N1 pandemic showed reduced infection and mortality rates in this group due to cross-reactive antibodies from prior exposures to antigenically similar H1N1 strains, such as those circulating before 1957.[51] Adults over 60 exhibited preexisting immunity, resulting in lower seroprevalence of novel strain antibodies but protection against severe disease.[95] Median age of hospitalized cases was 45 years, with peak risks in ages 16–25 and 46–55.[101] In seasonal H1N1 circulation post-2010, vulnerability patterns resemble typical influenza, emphasizing young children under 5, the elderly over 65, pregnant women, and those with chronic illnesses, though specific H1N1 strain data underscore ongoing risks from comorbidities like obesity in non-elderly adults.[104]Epidemiology and Global Spread

Seasonal Circulation Patterns

In temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere, such as the United States and Europe, seasonal epidemics of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 typically peak during the winter months, with the highest activity occurring between December and February.[105][106] Surveillance data from the CDC indicate that influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 accounted for 53.1% of subtyped seasonal influenza A viruses during the 2024–25 season in the US, aligning with this winter peak pattern observed in prior years.[107] Factors contributing to this seasonality include lower humidity, indoor crowding, and reduced vitamin D levels, which facilitate viral transmission and survival.[108] In the Southern Hemisphere, circulation mirrors the Northern pattern but offset by six months, with peaks generally from June to August during their winter.[104] WHO global surveillance through FluNet confirms this hemispheric dichotomy, where A(H1N1)pdm09 activity synchronizes with cooler, drier conditions, though intensity varies annually based on antigenic drift and population immunity.[109] Tropical and subtropical regions exhibit less pronounced seasonality for A(H1N1)pdm09, with year-round circulation or bimodal peaks often tied to rainy seasons that enhance aerosol transmission.[104] Unlike A/H3N2, which shows more uniform global seeding and rapid dissemination, A(H1N1)pdm09 maintains regionally persistent lineages with slower inter-hemispheric exchange, as evidenced by genomic analyses of pre-2009 and post-pandemic strains.[110][111] This pattern underscores the virus's reliance on local reservoirs and human mobility for sustained epidemics rather than broad antigenic shifts.[112]Transmission Dynamics

The primary mode of transmission for Influenza A virus subtype H1N1 is through large respiratory droplets expelled during coughing, sneezing, or speaking by infected individuals, which can infect susceptible persons within close proximity (typically less than 1-2 meters).[113] Experimental studies in animal models, including ferrets, have demonstrated efficient airborne transmission via fine aerosol particles for H1N1 strains, including the 2009 pandemic variant, supporting a role for this route in enclosed or poorly ventilated settings.[114] Fomite-mediated transmission, involving contact with virus-contaminated surfaces followed by self-inoculation to the eyes, nose, or mouth, occurs but is considered less efficient than direct respiratory routes, with viral viability on surfaces lasting up to 24-48 hours under typical environmental conditions.[113] The incubation period for H1N1 infection ranges from 1 to 4 days, with a median of approximately 2 days, during which the virus replicates asymptomatically before clinical symptoms emerge.[2] Infected individuals shed viable virus starting about 1 day before symptom onset and remain contagious for 5-7 days afterward in adults, though shedding can extend to 10 days or longer in children and immunocompromised persons, facilitating secondary transmission within households or communities.[115][2] Transmission dynamics of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic strain exhibited a basic reproduction number (R₀) estimated at 1.28 (range 0.89-2.08) based on systematic reviews of global data, indicating moderate transmissibility lower than that of prior pandemics such as 1918 (R₀ ≈ 1.4-2.8).[116] Household secondary attack rates were approximately 10-15%, with most transmissions occurring early after index case symptom onset (mean serial interval of 2.6 days), and higher rates observed from child index cases to other household members compared to adult-to-adult spread.[117] These parameters align closely with seasonal H1N1 circulation patterns, though pandemic waves showed enhanced spread in school-aged children due to behavioral factors like close contact in educational settings.[118]Mortality and Case Fatality Rates

The 1918 H1N1 influenza pandemic resulted in an estimated 50 to 100 million deaths worldwide, representing one of the deadliest events in human history, with mortality concentrated in young adults aged 20 to 40 years due to a dysregulated cytokine response. Case fatality rates (CFRs) varied by location and wave, ranging from 0.35% in initial milder waves to 2.3% during peak mortality periods in urban centers like New York City, where excess death rates reached 1.7 to 2.3 per 1,000 population. These figures reflect underreporting and diagnostic limitations of the era, but empirical reconstructions from death certificates and military records confirm the virus's exceptional lethality compared to subsequent seasonal strains.[119][35][120] In contrast, the 2009 H1N1pdm09 pandemic caused far lower mortality, with global estimates of 150,000 to 575,000 excess deaths, including approximately 284,000 attributed to respiratory and cardiovascular complications, primarily in individuals under 65 years. Laboratory-confirmed deaths totaled around 18,500 by mid-2010, but modeling adjusted for underascertainment yielded a CFR of 0.001% to 0.007% of the infected population, or 1 to 10 deaths per 100,000 infections, with heterogeneity across studies due to surveillance biases and varying testing rates. This rate was lower than many seasonal influenza strains, particularly in developed countries with access to antivirals and supportive care, though higher burdens occurred in indigenous and low-resource populations.[121][122]70121-4/fulltext) Post-2009, the H1N1pdm09 strain integrated into seasonal circulation, exhibiting CFRs comparable to or below other influenza A subtypes, typically 0.016% to 0.062% per confirmed infection in population-based studies, with annual global deaths from seasonal influenza (including H1N1) estimated at 290,000 to 650,000 respiratory fatalities. Excess mortality modeling for H1N1-dominant seasons shows rates of 0.05 to 0.09 per 1,000 influenza-like illness cases, influenced by vaccination coverage and comorbidities rather than inherent viral virulence. These patterns underscore H1N1's evolution toward milder pathogenicity in immune-experienced populations, though vulnerable groups like the obese and pregnant continue to face elevated risks.[123][122]| Pandemic/Period | Estimated Global Deaths | CFR Range | Key Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1918 H1N1 | 50–100 million | 0.35–2.3% | Cytokine storm in young adults; poor diagnostics[119] |

| 2009 H1N1pdm09 | 150,000–575,000 | 0.001–0.01% | Underreporting; milder in vaccinated/treated[122] |

| Seasonal H1N1 | 290,000–650,000 annual (all flu) | 0.016–0.062% | Comorbidities; immunity buildup[123] |