Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Humerus fracture

View on Wikipedia

| Humerus fracture | |

|---|---|

| |

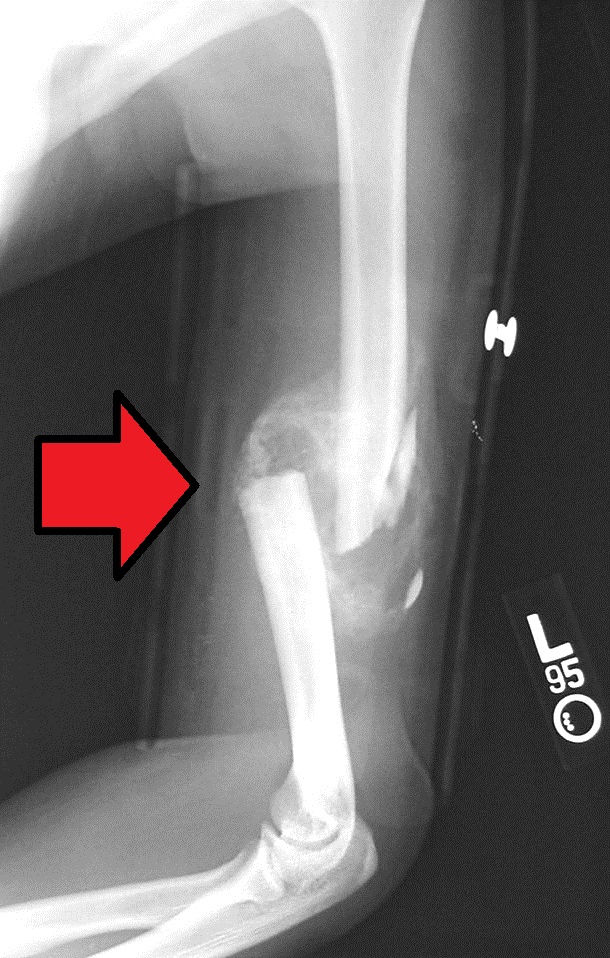

| Midshaft humerus fracture with callus formation | |

| Specialty | Orthopedics |

| Symptoms | Pain, swelling, bruising[1] |

| Complications | Injury to an artery or nerve, compartment syndrome[2] |

| Types | Proximal humerus, humerus shaft, distal humerus[1][2] |

| Causes | Trauma, cancer[2] |

| Diagnostic method | X-rays[2] |

| Treatment | Sling, splint, brace, surgery[1] |

| Prognosis | Generally good (proximal and shaft), Less good (distal)[2] |

| Frequency | ~4% of fractures[2] |

A humerus fracture is a break of the humerus bone in the upper arm.[1] Symptoms may include pain, swelling, and bruising.[1] There may be a decreased ability to move the arm and the person may present holding their elbow.[2] Complications may include injury to an artery or nerve, and compartment syndrome.[2]

The cause of a humerus fracture is usually physical trauma such as a fall.[1] Other causes include conditions such as cancer in the bone.[2] Types include proximal humeral fractures, humeral shaft fractures, and distal humeral fractures.[1][2] Diagnosis is generally confirmed by X-rays.[2] A CT scan may be done in proximal fractures to gather further details.[2]

Treatment options may include a sling, splint, brace, or surgery.[1] In proximal fractures that remain well aligned, a sling is often sufficient.[2] Many humerus shaft fractures may be treated with a brace rather than surgery.[2] Surgical options may include open reduction and internal fixation, closed reduction and percutaneous pinning, and intramedullary nailing.[2] Joint replacement may be another option.[2] Proximal and shaft fractures generally have a good outcome while outcomes with distal fractures can be less good.[2] They represent about 4% of fractures.[2]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

After a humerus fracture, pain is immediate, enduring, and exacerbated with the slightest movements. The affected region swells, with bruising appearing a day or two after the fracture. The fracture is typically accompanied by a discoloration of the skin at the site of the fracture.[3][4] A crackling or rattling sound may also be present, caused by the fractured humerus pressing against itself.[5] In cases in which the nerves are affected, then there will be a loss of control or sensation in the arm below the fracture.[6][4] If the fracture affects the blood supply, then the patient will have a diminished pulse at the wrist.[6] Displaced fractures of the humerus shaft will often cause deformity and a shortening of the length of the upper arm.[5] Distal fractures may also cause deformity, and they typically limit the ability to flex the elbow.[7]

Causes

[edit]Humerus fractures usually occur after physical trauma, falls, excess physical stress, or pathological conditions. Falls that produce humerus fractures among the elderly are usually accompanied by a preexisting risk factor for bone fracture, such as osteoporosis, a low bone density, or vitamin B deficiency.[8]

Proximal

[edit]Proximal humerus fractures most often occur among elderly people with osteoporosis who fall on an outstretched arm.[9] Less frequently, proximal fractures occur from motor vehicle accidents, gunshots, and violent muscle contractions from an electric shock or seizure.[10][5] Other risk factors for proximal fractures include having a low bone mineral density, having impaired vision and balance, and tobacco smoking.[11] A stress fracture of the proximal and shaft regions can occur after an excessive amount of throwing, such as pitching in baseball.[6]

Middle

[edit]Middle fractures are usually caused by either physical trauma or falls. Physical trauma to the humerus shaft tends to produce transverse fractures whereas falls tend to produce spiral fractures. Metastatic breast cancer may also cause fractures in the humerus shaft.[12] Long spiral fractures of the shaft that are present in children may indicate physical abuse.[5]

Distal

[edit]Distal humerus fractures usually occur as a result of physical trauma to the elbow region. If the elbow is bent during the trauma, then the olecranon is driven upward, producing a T- or Y-shaped fracture or displacing one of the condyles.[7]

Diagnosis

[edit]Definitive diagnosis of humerus fractures is typically made through radiographic imaging. For proximal fractures, X-rays can be taken from a scapular anteroposterior (AP) view, which takes an image of the front of the shoulder region from an angle, a scapular Y view, which takes an image of the back of the shoulder region from an angle, and an axillar lateral view, which has the patient lie on his or her back, lift the bottom half of the arm up to the side, and have an image taken of the axilla region underneath the shoulder.[9] Fractures of the humerus shaft are usually correctly identified with radiographic images taken from the AP and lateral viewpoints.[12] Damage to the radial nerve from a shaft fracture can be identified by an inability to bend the hand backwards or by decreased sensation in the back of the hand.[5] Images of the distal region are often of poor quality due to the patient being unable to extend the elbow because of pain. If a severe distal fracture is suspected, then a computed tomography (CT) scan can provide greater detail of the fracture. Nondisplaced distal fractures may not be directly visible; they may only be visible due to fat being displaced because of internal bleeding in the elbow.[7]

-

A fracture of the greater tuberosity as seen on AP X ray

-

A fracture of the greater tuberosity of the humerus

-

Fracture of the greater tuberosity of the humerus

-

Multi-fragmented, or comminuted fracture of the proximal humerus with involvement of the greater tuberosity

-

Proximal humerus fracture

-

A transverse fracture of the humerus shaft

-

A spiral fracture of the distal one-third of the humerus shaft

-

A displaced supracondylar fracture in a child

Classification

[edit]Fractures of the humerus are classified based on the location of the fracture and then by the type of fracture. There are three locations that humerus fractures occur: at the proximal location, which is the top of the humerus near the shoulder, in the middle, which is at the shaft of the humerus, and the distal location, which is the bottom of the humerus near the elbow.[9] Proximal fractures are classified into one of four types of fractures based on the displacement of the greater tubercle, the lesser tubercle, the surgical neck, and the anatomical neck, which are the four parts of the proximal humerus, with fracture displacement being defined as at least one centimeter of separation or an angulation greater than 45 degrees. One-part fractures involve no displacement of any parts of the humerus, two-part fractures have one part displaced relative to the other three; three-part fractures have two displaced fragments, and four-part fractures have all fragments displaced from each other.[13][14][3] Fractures of the humerus shaft are subdivided into transverse fractures, spiral fractures, "butterfly" fractures, which are a combination of transverse and spiral fractures, and pathological fractures, which are fractures caused by medical conditions.[12] Distal fractures are split between supracondylar fractures, which are transverse fractures above the two condyles at the bottom of the humerus, and intercondylar fractures, which involve a T- or Y-shaped fracture that splits the condyles.[7]

Treatment

[edit]The aim of treatment is to minimize pain and to restore as much normal function as possible. Most humerus fractures do not require surgical intervention.[4]

Proximal

[edit]One-part and two-part proximal fractures can be treated with a collar and cuff sling, adequate pain medicine, and follow up therapy. Two-part proximal fractures may require open or closed reduction depending on neurovascular injury, rotator cuff injury, dislocation, likelihood of union, and function. For three- and four-part proximal fractures, standard practice is to have open reduction and internal fixation to realign the separate parts of the proximal humerus. A humeral hemiarthroplasty may be required in proximal cases in which the blood supply to the region is compromised.[15] Compared with non-surgical treatment, surgery does not result in a better outcome for the majority of people with displaced proximal humeral fractures and is likely to result in a greater need for subsequent surgery.[16]

Middle

[edit]Fractures of the humerus shaft are most often uncomplicated, closed fractures that require nothing more than pain medicine and wearing a cast or sling. For midshaft fractures up to 12 weeks may be required for healing.[17]

In shaft and distal cases in which complications such as damage to the neurovascular bundle exist, then surgical repair is required.[18]

Prognosis

[edit]In most cases, people are discharged from an emergency department with pain medicine and a cast or sling. These fractures are typically minor and heal over the course of a few weeks.[4] Fractures of the proximal region, especially among elderly people, may limit future shoulder activity.[19][20] Severe fractures are usually resolved with surgical intervention, followed by a period of healing using a cast or sling.[11] Severe fractures often cause long-term loss of physical ability.[21] Complications in the recovery process of severe fractures include osteonecrosis, malunion or nonunion of the fracture, stiffness, and rotator cuff dysfunction, which require additional intervention in order for the patient to fully recover.[21]

Epidemiology

[edit]Humerus fractures are among the most common of fractures. Proximal fractures make up 5% of all fractures and 25% of humerus fractures,[9] middle fractures about 60% of humerus fractures (12% of all fractures),[12] and distal fractures the remainder. Among proximal fractures, 80% are one-part, 10% are two-part, and the remaining 10% are three- and four-part.[22] The most common location of proximal fractures is at the surgical neck of the humerus.[3] Incidence of proximal fractures increases with age, with about 75% of cases occurring among people over the age of 60.[11] In this age group, about three times as many women as men experience a proximal fracture.[23] Middle fractures are also common among the elderly, but they frequently occur among physically active young adult men who experience physical trauma to the humerus.[12] Distal fractures are rare among adults, occurring primarily in children who experience physical trauma to the elbow region.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h "Humerus Fracture (Upper Arm Fracture)". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Attum B, Thompson JH (6 June 2019). "Humerus Fractures Overview". StatPearls. PMID 29489190.

- ^ a b c Cuccurullo, 2014, p. 177

- ^ a b c d Cameron, et al., 2014, p. 167–170

- ^ a b c d e Auth, 2012, p. 167

- ^ a b c Cuccurullo, 2014, p. 178

- ^ a b c d e Cameron, et al., 2014, p. 170

- ^ Cameron, et al., 2014, p. 167, 169

- ^ a b c d Cameron, et al., 2014, p. 167

- ^ Crosby, et al., 2014, p. 4

- ^ a b c Crosby, et al., 2014, p. 23

- ^ a b c d e Cameron, et al., 2014, p. 169

- ^ Cameron, et al., 2014, pp. 167–168

- ^ Crosby, et al., 2014, pp. 11–19

- ^ Cameron, et al., 2014, pp. 168–169

- ^ Handoll HH, Elliott J, Thillemann TM, Aluko P, Brorson S (June 2022). "Interventions for treating proximal humeral fractures in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022 (6) CD000434. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000434.pub5. PMC 9211385. PMID 35727196.

- ^ Bounds EJ, Frane N, Kok SJ (2018). "Humeral Shaft Fractures". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 28846218.

- ^ Cameron, et al., 2014, pp. 169–170

- ^ Malhotra, 2013, p. 47

- ^ Crosby, et al., 2014, p. 31

- ^ a b Crosby, et al., 2014, p. 35

- ^ Cameron, et al., 2014, p. 168

- ^ Crosby, et al., 2014, p. 1

Bibliography

[edit]- Auth PD, Kerstein MD (30 July 2012). Physician Assistant Review. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 167. ISBN 978-1-4511-7129-7. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- Cameron P, Jelinek G, Kelly AM, Murray L, Brown AF (1 April 2014). Textbook of Adult Emergency Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 167–170. ISBN 978-0-7020-5438-9. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- Crosby L, Neviaser R (28 October 2014). Proximal Humerus Fractures: Evaluation and Management. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-08951-5. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- Cuccurullo SJ (25 November 2014). Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Board Review, Third Edition. Demos Medical Publishing. pp. 177–178. ISBN 978-1-61705-201-9. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- Malhotra R (15 December 2013). Mastering Orthopedic Techniques: Intra-articular Fractures. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers Pvt. Ltd. pp. 47–62. ISBN 978-93-5090-826-6. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

External links

[edit]Humerus fracture

View on GrokipediaClinical Presentation

Signs and Symptoms

A humerus fracture typically presents with severe pain at the site of injury, which is often immediate and intensifies with any movement of the arm.[2] This pain can radiate along the upper arm and significantly limits the patient's ability to use the affected limb, such as lifting or rotating the arm.[4] Patients frequently report a grinding or crunching sensation during attempted motion, reflecting the mechanical disruption of the bone.[4] Swelling and bruising, known as ecchymosis, commonly develop around the fracture site in the upper arm, often extending to adjacent areas like the shoulder or elbow.[5] The affected area becomes tender to touch, contributing to further discomfort and reluctance to manipulate the limb.[2] These soft tissue changes arise from local hemorrhage and inflammation following the bone break.[5] Functional impairment is prominent, with decreased range of motion and inability to perform routine tasks like raising the arm overhead or supporting weight.[1] In severe cases, visible deformity may occur, such as shortening, angulation, or an abnormal contour of the upper arm due to bone displacement.[2] If neurovascular structures are compromised by the fracture fragments or associated hematoma, patients may experience numbness, tingling, or weakness in the arm or hand, indicating potential nerve or vascular involvement.[4] Symptoms can vary modestly by fracture location along the humerus, but the primary manifestations of pain, swelling, and limited function are consistent across cases.[5]Physical Examination

The physical examination of a suspected humerus fracture begins with a systematic assessment to identify deformity, associated soft tissue injury, and neurovascular compromise, while minimizing patient discomfort. Inspection reveals swelling, ecchymosis, and potential skin tenting or open wounds indicating an open fracture, with ecchymosis often extending to the chest, arm, or forearm in proximal injuries due to hematoma spread. Deformity may present as shortening, varus angulation, or rotational malalignment, particularly in shaft fractures distal to the deltoid insertion, where the arm appears shortened and adducted. Skin integrity is evaluated for lacerations or punctures, as these suggest contamination and necessitate urgent intervention. Palpation is performed gently along the humerus to localize point tenderness, elicit crepitus from bone ends rubbing together, and assess abnormal mobility by rotating the humeral shaft while palpating the proximal or distal segments for unified motion. In proximal fractures, palpation of the humeral head during gentle rotation helps determine stability and detect crepitus, while shaft fractures often show focal tenderness and deformity at the mid-humerus. Distal fractures may exhibit tenderness over the elbow with crepitus in the olecranon fossa. Range of motion testing is limited by pain, with active and passive abduction, flexion, and rotation eliciting severe discomfort, particularly in proximal injuries where shoulder motion is restricted. Neurovascular examination is critical, as up to 18% of shaft fractures involve radial nerve injury, manifesting as wrist drop (weakness in wrist and finger extension) and sensory loss over the dorsal hand first web space. The axillary nerve is most commonly affected in proximal fractures, tested by deltoid contraction and sensation over the lateral shoulder, while distal fractures risk median, ulnar, or radial nerve deficits, assessed via motor function (e.g., thumb opposition for median) and sensory testing in dermatomes. Vascular status includes palpation of brachial, radial, and ulnar pulses, with comparison to the contralateral side and monitoring for capillary refill; absent pulses warrant immediate imaging or exploration.Etiology and Risk Factors

Mechanisms of Injury

Humerus fractures result from biomechanical forces that exceed the bone's structural integrity, typically involving direct trauma, indirect forces, or a combination thereof, leading to stress concentrations that propagate cracks in transverse, oblique, spiral, or comminuted patterns depending on the loading direction and magnitude.[6] Direct trauma applies localized perpendicular force, often causing transverse fractures through bending stress at the impact site, while indirect mechanisms like axial loading or torsion generate oblique or spiral patterns due to shear and twisting stresses along the bone's longitudinal axis.[7] High-energy mechanisms, such as motor vehicle accidents, produce comminuted fractures with multiple fragments from explosive force distribution, whereas low-energy events like ground-level falls result in simpler patterns, particularly in osteoporotic bone.[8] For proximal humerus fractures, the most common mechanism is a low-energy fall onto an outstretched hand (FOOSH) with the arm in abduction and external rotation, transmitting axial compression and varus stress to the humeral head, often in elderly patients.[7] In younger individuals, high-energy direct impacts from sports or vehicular collisions cause similar compression but with greater displacement.[8] A specific example is avulsion of the greater tuberosity, resulting from sudden contraction of the rotator cuff muscles (supraspinatus and infraspinatus) during forceful abduction or external rotation, often associated with anterior shoulder dislocation, where tensile stress pulls the tuberosity fragment away from the humerus.[9] Humeral shaft fractures predominantly arise from direct blows to the mid-arm, such as in assaults or falls onto the lateral humerus, generating transverse fracture lines perpendicular to the force vector due to localized bending stress concentration in the diaphysis.[10] Indirect mechanisms include FOOSH with the elbow extended, driving the distal humerus proximally and creating oblique or impacted patterns from axial compression.[11] High-energy scenarios like motor vehicle accidents account for about 30% of cases, leading to comminuted or segmental fractures from combined bending and torsional forces, while low-energy ground-level falls comprise 60%, typically yielding simpler transverse or spiral configurations.[10] Distal humerus fractures often stem from high-energy direct trauma in younger adults, such as dashboard impacts in motor vehicle collisions compressing the elbow posteriorly, resulting in supracondylar or intercondylar patterns with posterior displacement from varus or valgus stress.[12] Low-energy FOOSH in the elderly transmits axial load through the olecranon, hyperextending the elbow and fracturing the supracondylar region via tension on the anterior cortex and compression posteriorly.[13] Indirect varus or valgus forces from falls with the forearm twisted can isolate medial or lateral columns, producing T- or Y-shaped intra-articular fractures due to uneven stress distribution across the trochlea.[14]Predisposing Factors

Bone health issues, particularly osteoporosis and osteopenia, significantly increase the susceptibility to humerus fractures, especially fragility fractures of the proximal humerus in older adults.[7] Osteoporosis weakens bone density, making it more prone to low-energy trauma such as falls from standing height, and is particularly prevalent among postmenopausal women due to estrogen deficiency accelerating bone loss.[15] Similarly, osteopenia represents a precursor state that heightens fracture risk without the full severity of osteoporosis.[16] Age-related factors contribute distinctly across life stages, with higher incidence of proximal humerus fragility fractures in the elderly over 65 years due to cumulative bone loss and reduced muscle strength.[7] In children, particularly those aged 5 to 7 years, distal humerus fractures like supracondylar or greenstick types are more common, predisposed by the flexibility of immature bones with thicker periosteum that favors incomplete fractures during falls.[17] Comorbidities such as neurological conditions, including stroke, elevate fracture risk through impaired balance and increased fall propensity, with stroke survivors facing 1.4 to 7 times higher odds of humerus fractures compared to the general population.[18] Malignancy-related pathologic fractures of the humerus often stem from metastatic bone lesions weakening the cortex, commonly from primaries like breast, lung, or prostate cancer.[19] Lifestyle factors impairing bone integrity include chronic alcoholism and smoking, which reduce bone mineral density and healing capacity, thereby increasing humerus fracture susceptibility; for instance, alcohol consumption exceeding moderate levels disrupts calcium absorption, while smoking inhibits osteoblast activity.[20] Participation in high-risk activities, such as contact sports, predisposes individuals to humerus shaft fractures via direct impact or torsional forces. Anatomical variations, including pre-existing deformities or prior fractures, compromise bone strength and elevate the risk of subsequent humerus fractures by creating stress risers or altering load distribution.[21]Types and Classification

Proximal Humerus Fractures

Proximal humerus fractures involve the upper end of the humerus, including the humeral head, anatomic neck, surgical neck, greater tuberosity, and lesser tuberosity. These fractures are common in older adults due to osteoporosis and in younger patients from high-energy trauma. They are classified primarily using the Neer classification system, which divides the proximal humerus into four segments: the humeral head, shaft, greater tuberosity, and lesser tuberosity. A segment is considered displaced if separation exceeds 1 cm or angulation is greater than 45 degrees.[22]- One-part fractures: Nondisplaced or minimally displaced, involving any number of segments without significant separation; these represent the majority of cases and often include impacted fractures.

- Two-part fractures: Displacement of one segment, such as surgical neck, anatomic neck, greater tuberosity, or lesser tuberosity fractures.

- Three-part fractures: Displacement of two segments, typically involving the surgical neck plus one tuberosity.

- Four-part fractures: Displacement of all four segments, often with high risk of avascular necrosis due to disrupted blood supply to the humeral head; includes head-split and valgus impaction variants.

Humeral Shaft Fractures

Humeral shaft fractures occur in the diaphysis, defined as the region from the proximal surgical neck to approximately 5 cm proximal to the olecranon fossa in the distal humerus. These represent about 3-5% of all fractures and are often transverse, oblique, spiral, or comminuted, resulting from direct trauma or torsional forces. They are subclassified by location (proximal third, middle third, distal third) and pattern, with Holstein-Lewis fractures (distal third spiral) at higher risk for radial nerve injury.[10] The primary classification is the AO/OTA system (code 12), which categorizes based on fracture morphology:- Type A (simple fractures): Single fracture line, including spiral (A1), oblique (A2), or transverse (A3) patterns.

- Type B (wedge fractures): Multifragmentary with an intact wedge, subdivided into intact wedge (B1), fragmented wedge (B2), or bending wedge (B3).

- Type C (multifragmentary/complex fractures): Irregular, highly comminuted without a defined wedge, including segmental (C2) or highly irregular (C3) subtypes.

Distal Humerus Fractures

Distal humerus fractures involve the metaphysis and/or articular surface of the lower humerus, from 5 cm above the olecranon fossa to the supracondylar ridges. These account for 2% of fractures in adults and up to 60% in children (primarily supracondylar), often from falls or varus/valgus stresses. They are intra-articular in 50-70% of adult cases, complicating management due to elbow joint involvement.[26] Adult distal humerus fractures are classified using the AO/OTA system (code 13):- Type A (extra-articular): Supracondylar or transcondylar fractures without joint involvement, including simple (A1), wedge (A2), or complex (A3) metaphyseal patterns.

- Type B (partial articular): Involves part of the articular surface, such as lateral/medial condyle (B1), transcondylar (B2), or frontal plane (capitellar/trochlear, B3).

- Type C (complete articular): Fracture lines separate the articular surface from the shaft and cross both columns, with simple (C1), simple articular/simple metaphyseal (C2), or complex (C3) variants.

- Type I: Nondisplaced or minimally angulated (<5 degrees).

- Type II: Displaced with intact posterior cortex (IIa: angulated without rotation; IIb: with rotation).

- Type III: Completely displaced, unstable in all planes.

- Type IV: Unstable after reduction, with multidirectional instability.