Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Human leg

View on Wikipedia

| Human leg | |

|---|---|

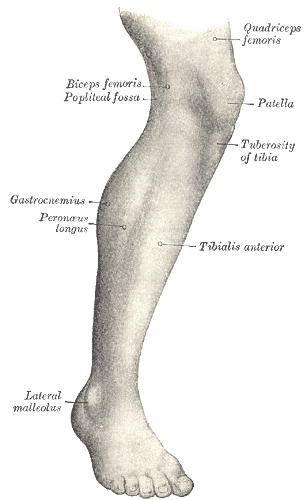

Lateral aspect of right leg | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | membrum inferius |

| FMA | 7184 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The leg is the entire lower limb of the human body, including the foot, thigh or sometimes even the hip or buttock region. The major bones of the leg are the femur (thigh bone), tibia (shin bone), and adjacent fibula. There are thirty bones in each leg.

The thigh is located in between the hip and knee.

The shank - the calf (rear) and the shin (front) - is located between the knee and the ankle..[1]

Legs are used for standing, many forms of human movement, recreation such as dancing, and constitute a significant portion of a person's mass. Evolution has led to the human leg's development into a mechanism specifically adapted for efficient bipedal gait.[2] While the capacity to walk upright is not unique to humans, other primates can only achieve this for short periods and at a great expenditure of energy.[3] In humans, female legs generally have greater hip anteversion and tibiofemoral angles, while male legs have longer femur and tibial lengths.[4]

In humans, each lower limb is divided into the hip, thigh, knee, leg, ankle and foot.

In anatomy, arm refers to the upper arm and leg refers to the lower leg.[5]

Structure

[edit]

In human anatomy, the lower leg or crus (or shank) is the part of the lower limb that lies between the knee and the ankle.[6][1] In the lower leg, the calf is the back portion, and the tibia or shinbone together with the smaller fibula make up the shin, the front of the lower leg.[7] Anatomists restrict the term leg to this use, rather than to the entire lower limb.[8] The thigh is between the hip and knee and makes up the rest of the lower limb.[1] The term lower limb or lower extremity is commonly used to describe all of the leg.

Evolution has provided the human body with two distinct features: the specialization of the upper limb for visually guided manipulation and the lower limb's development into a mechanism specifically adapted for an efficient bipedal gait.[2] While the capacity to walk upright is not unique to humans, other primates can only achieve this for short periods and at a great expenditure of energy.[3]

The human adaption to bipedalism has also affected the location of the body's center of gravity, the reorganization of internal organs, and the form and biomechanism of the trunk.[9] In humans, the double S-shaped vertebral column acts as a great shock-absorber which shifts the weight from the trunk over the load-bearing surface of the feet. The human legs are exceptionally long and powerful as a result of their exclusive specialization for support and locomotion—in orangutans the leg length is 111% of the trunk; in chimpanzees 128%, and in humans 171%. Many of the leg's muscles are also adapted to bipedalism, most substantially the gluteal muscles, the extensors of the knee joint, and the calf muscles.[10]

Bones

[edit]

The major bones of the leg are the femur (thigh bone), tibia (shin bone), and adjacent fibula, which are all long bones. The patella (kneecap) is a sesamoid bone (the largest in the body) in front of the knee. Most of the leg skeleton has bony prominences and margins that can be palpated, and some serve as anatomical landmarks that define the extent of the leg. These landmarks are the anterior superior iliac spine, the greater trochanter, the superior margin of the medial condyle of tibia, and the medial malleolus.[11] Notable exceptions to palpation are the hip joint, and the neck and body, or shaft of the femur.

Usually, the large joints of the lower limb are aligned in a straight line, which represents the mechanical longitudinal axis of the leg, the Mikulicz line. This line stretches from the hip joint (or more precisely the head of the femur), through the knee joint (the intercondylar eminence of the tibia), and down to the center of the ankle (the ankle mortise, the fork-like grip between the medial and lateral malleoli). In the tibial shaft, the mechanical and anatomical axes coincide, but in the femoral shaft they diverge 6°, resulting in the femorotibial angle of 174° in a leg with normal axial alignment. A leg is considered straight when, with the feet brought together, both the medial malleoli of the ankle and the medial condyles of the knee are touching. Divergence from the normal femorotibial angle is called genu varum if the center of the knee joint is lateral to the mechanical axis (intermalleolar distance exceeds 3 cm), and genu valgum if it is medial to the mechanical axis (intercondylar distance exceeds 5 cm). These conditions impose unbalanced loads on the joints and stretching of either the thigh's adductors and abductors.[12]

The angle of inclination formed between the neck and shaft of the femur (collodiaphysial angle) varies with age—about 150° in the newborn, it gradually decreases to 126–128° in adults, to reach 120° in old age. Pathological changes in this angle result in abnormal posture of the leg: a small angle produces coxa vara and a large angle coxa valga; the latter is usually combined with genu varum, and coxa vara leads genu valgum. Additionally, a line drawn through the femoral neck superimposed on a line drawn through the femoral condyles forms an angle, the torsion angle, which makes it possible for flexion movements of the hip joint to be transposed into rotary movements of the femoral head. Abnormally increased torsion angles result in a limb turned inward and a decreased angle in a limb turned outward; both cases resulting in a reduced range of a person's mobility.[13]

Muscles

[edit]Hip

[edit]| Movement | Muscles (in order of importance) |

|---|---|

| Lateral rotation |

•Sartorius |

| Medial rotation |

•Gluteus medius and |

| Extension |

•Gluteus maximus |

| Flexion |

•Iliopsoas |

| Abduction |

•Gluteus medius |

| Adduction |

•Adductor magnus |

| Notes | ♣ Also act on vertebral joints. * Also act on knee joint. |

There are several ways of classifying the muscles of the hip:

- By location or innervation (ventral and dorsal divisions of the plexus layer);

- By development on the basis of their points of insertion (a posterior group in two layers and an anterior group); and

- By function (i.e. extensors, flexors, adductors, and abductors).[15]

Some hip muscles also act either on the knee joint or on vertebral joints. Additionally, because the areas of origin and insertion of many of these muscles are very extensive, these muscles are often involved in several very different movements. In the hip joint, lateral and medial rotation occur along the axis of the limb; extension (also called dorsiflexion or retroversion) and flexion (anteflexion or anteversion) occur along a transverse axis; and abduction and adduction occur about a sagittal axis.[14]

The anterior dorsal hip muscles are the iliopsoas, a group of two or three muscles with a shared insertion on the lesser trochanter of the femur. The psoas major originates from the last vertebra and along the lumbar spine to stretch down into the pelvis. The iliacus originates on the iliac fossa on the interior side of the pelvis. The two muscles unite to form the iliopsoas muscle, which is inserted on the lesser trochanter of the femur. The psoas minor, only present in about 50 per cent of subjects, originates above the psoas major to stretch obliquely down to its insertion on the interior side of the major muscle.[16]

The posterior dorsal hip muscles are inserted on or directly below the greater trochanter of the femur. The tensor fasciae latae, stretching from the anterior superior iliac spine down into the iliotibial tract, presses the head of the femur into the acetabulum but also flexes, rotates medially, and abducts to hip joint. The piriformis originates on the anterior pelvic surface of the sacrum, passes through the greater sciatic foramen, and inserts on the posterior aspect of the tip of the greater trochanter. In a standing posture it is a lateral rotator, but it also assists extending the thigh. The gluteus maximus has its origin between (and around) the iliac crest and the coccyx, from where one part radiates into the iliotibial tract and the other stretches down to the gluteal tuberosity under the greater trochanter. The gluteus maximus is primarily an extensor and lateral rotator of the hip joint, and it comes into action when climbing stairs or rising from a sitting to a standing posture. Furthermore, the part inserted into the fascia latae abducts and the part inserted into the gluteal tuberosity adducts the hip. The two deep glutei muscles, the gluteus medius and minimus, originate on the lateral side of the pelvis. The medius muscle is shaped like a cap. Its anterior fibers act as a medial rotator and flexor; the posterior fibers as a lateral rotator and extensor; and the entire muscle abducts the hip. The minimus has similar functions and both muscles are inserted onto the greater trochanter.[17]

The ventral hip muscles function as lateral rotators and play an important role in the control of the body's balance. Because they are stronger than the medial rotators, in the normal position of the leg, the apex of the foot is pointing outward to achieve better support. The obturator internus originates on the pelvis on the obturator foramen and its membrane, passes through the lesser sciatic foramen, and is inserted on the trochanteric fossa of the femur. "Bent" over the lesser sciatic notch, which acts as a fulcrum, the muscle forms the strongest lateral rotators of the hip together with the gluteus maximus and quadratus femoris. When sitting with the knees flexed it acts as an abductor. The obturator externus has a parallel course with its origin located on the posterior border of the obturator foramen. It is covered by several muscles and acts as a lateral rotator and a weak adductor. The inferior and superior gemelli muscles represent marginal heads of the obturator internus and assist this muscle. These three muscles form a three-headed muscle (tricipital) known as the triceps coxae.[18] The quadratus femoris originates at the ischial tuberosity and is inserted onto the intertrochanteric crest between the trochanters. This flattened muscle act as a strong lateral rotator and adductor of the thigh.[19]

The adductor muscles of the thigh are innervated by the obturator nerve, with the exception of pectineus which receives fibers from the femoral nerve, and the adductor magnus which receives fibers from the tibial nerve. The gracilis arises from near the pubic symphysis and is unique among the adductors in that it reaches past the knee to attach on the medial side of the shaft of the tibia, thus acting on two joints. It share its distal insertion with the sartorius and semitendinosus, all three muscles forming the pes anserinus. It is the most medial muscle of the adductors, and with the thigh abducted its origin can be clearly seen arching under the skin. With the knee extended, it adducts the thigh and flexes the hip. The pectineus has its origin on the iliopubic eminence laterally to the gracilis and, rectangular in shape, extends obliquely to attach immediately behind the lesser trochanter and down the pectineal line and the proximal part of the Linea aspera on the femur. It is a flexor of the hip joint, and an adductor and a weak medial rotator of the thigh. The adductor brevis originates on the inferior ramus of the pubis below the gracilis and stretches obliquely below the pectineus down to the upper third of the Linea aspera. Except for being an adductor, it is a lateral rotator and weak flexor of the hip joint.[20]

The adductor longus has its origin at superior ramus of the pubis and inserts medially on the middle third of the Linea aspera. Primarily an adductor, it is also responsible for some flexion. The adductor magnus has its origin just behind the longus and lies deep to it. Its wide belly divides into two parts: One is inserted into the Linea aspera and the tendon of the other reaches down to adductor tubercle on the medial side of the femur's distal end where it forms an intermuscular septum that separates the flexors from the extensors. Magnus is a powerful adductor, especially active when crossing legs. Its superior part is a lateral rotator but the inferior part acts as a medial rotator on the flexed leg when rotated outward and also extends the hip joint. The adductor minimus is an incompletely separated subdivision of the adductor magnus. Its origin forms an anterior part of the magnus and distally it is inserted on the Linea aspera above the magnus. It acts to adduct and lateral rotate the femur.[21]

Thigh

[edit]| Movement | Muscles (in order of importance) |

|---|---|

| Extension | |

| Flexion |

•Semimembranosus |

| Medial rotation |

•Semimembranosus |

| Lateral rotation |

•Biceps femoris |

| *Insignificant assistance. | |

The muscles of the thigh can be classified into three groups according to their location: anterior and posterior muscles and the adductors (on the medial side). All the adductors except gracilis insert on the femur and act on the hip joint, and so functionally qualify as hip muscles. The majority of the thigh muscles, the "true" thigh muscles, insert on the leg (either the tibia or the fibula) and act primarily on the knee joint. Generally, the extensors lie on anterior of the thigh and flexors lie on the posterior. Even though the sartorius flexes the knee, it is ontogenetically considered an extensor since its displacement is secondary.[15]

Of the anterior thigh muscles the largest are the four muscles of the quadriceps femoris: the central rectus femoris, which is surrounded by the three vasti, the vastus intermedius, medialis, and lateralis. Rectus femoris is attached to the pelvis with two tendons, while the vasti are inserted to the femur. All four muscles unite in a common tendon inserted into the patella from where the patellar ligament extends it down to the tibial tuberosity. Fibers from the medial and lateral vasti form two retinacula that stretch past the patella on either sides down to the condyles of the tibia. The quadriceps is the knee extensor, but the rectus femoris additionally flexes the hip joint, and articular muscle of the knee protects the articular capsule of the knee joint from being nipped during extension. The sartorius runs superficially and obliquely down on the anterior side of the thigh, from the anterior superior iliac spine to the pes anserinus on the medial side of the knee, from where it is further extended into the crural fascia. The sartorius acts as a flexor on both the hip and knee, but, due to its oblique course, also contributes to medial rotation of the leg as one of the pes anserinus muscles (with the knee flexed), and to lateral rotation of the hip joint.[23]

There are four posterior thigh muscles. The biceps femoris has two heads: The long head has its origin on the ischial tuberosity together with the semitendinosus and acts on two joints. The short head originates from the middle third of the linea aspera on the shaft of the femur and the lateral intermuscular septum of thigh, and acts on only one joint. These two heads unite to form the biceps which inserts on the head of the fibula. The biceps flexes the knee joint and rotates the flexed leg laterally—it is the only lateral rotator of the knee and thus has to oppose all medial rotator. Additionally, the long head extends the hip joint. The semitendinosus and the semimembranosus share their origin with the long head of the biceps, and both attaches on the medial side of the proximal head of the tibia together with the gracilis and sartorius to form the pes anserinus. The semitendinosus acts on two joints; extension of the hip, flexion of the knee, and medial rotation of the leg. Distally, the semimembranosus' tendon is divided into three parts referred to as the pes anserinus profondus. Functionally, the semimembranosus is similar to the semitendinosus, and thus produces extension at the hip joint and flexion and medial rotation at the knee.[24] Posteriorly below the knee joint, the popliteus stretches obliquely from the lateral femoral epicondyle down to the posterior surface of the tibia. The subpopliteal bursa is located deep to the muscle. Popliteus flexes the knee joint and medially rotates the leg.[25]

Lower leg and foot

[edit]| Movement | Muscles (in order of importance) |

|---|---|

| Dorsi- flexion |

•Tibialis anterior |

| Plantar flexion |

•Triceps surae |

| Eversion |

•Fibularis (peroneus) longus |

| Inversion |

•Triceps surae |

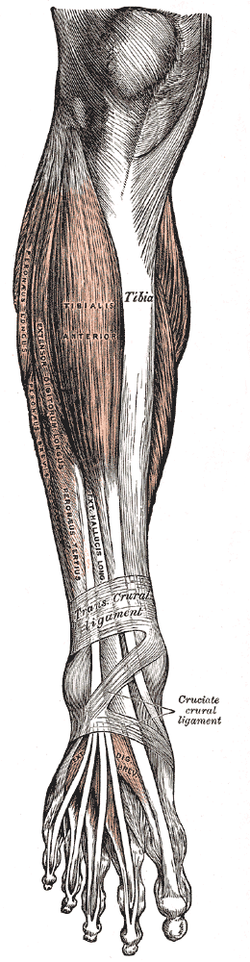

With the popliteus (see above) as the single exception, all muscles in the leg are attached to the foot and, based on location, can be classified into an anterior and a posterior group separated from each other by the tibia, the fibula, and the interosseous membrane. In turn, these two groups can be subdivided into subgroups or layers—the anterior group consists of the extensors and the peroneals, and the posterior group of a superficial and a deep layer. Functionally, the muscles of the leg are either extensors, responsible for the dorsiflexion of the foot, or flexors, responsible for the plantar flexion. These muscles can also classified by innervation, muscles supplied by the anterior subdivision of the plexus and those supplied by the posterior subdivision.[27] The leg muscles acting on the foot are called the extrinsic foot muscles whilst the foot muscles located in the foot are called intrinsic.[28]

Dorsiflexion (extension) and plantar flexion occur around the transverse axis running through the ankle joint from the tip of the medial malleolus to the tip of the lateral malleolus. Pronation (eversion) and supination (inversion) occur along the oblique axis of the ankle joint.[26]

Extrinsic

[edit]

Three of the anterior muscles are extensors. From its origin on the lateral surface of the tibia and the interosseus membrane, the three-sided belly of the tibialis anterior extends down below the superior and inferior extensor retinacula to its insertion on the plantar side of the medial cuneiform bone and the first metatarsal bone. In the non-weight-bearing leg, the anterior tibialis dorsal flexes the foot and lifts the medial edge of the foot. In the weight-bearing leg, it pulls the leg towards the foot. The extensor digitorum longus has a wide origin stretching from the lateral condyle of the tibia down along the anterior side of the fibula, and the interosseus membrane. At the ankle, the tendon divides into four that stretch across the foot to the dorsal aponeuroses of the last phalanges of the four lateral toes. In the non-weight-bearing leg, the muscle extends the digits and dorsiflexes the foot, and in the weight-bearing leg acts similar to the tibialis anterior. The extensor hallucis longus has its origin on the fibula and the interosseus membrane between the two other extensors and is, similarly to the extensor digitorum, is inserted on the last phalanx of big toe ("hallux"). The muscle dorsiflexes the hallux, and acts similar to the tibialis anterior in the weight-bearing leg.[29] Two muscles on the lateral side of the leg form the fibular (peroneal) group. The fibularis (peroneus) longus and fibularis (peroneus) brevis both have their origins on the fibula, and they both pass behind the lateral malleolus where their tendons pass under the fibular retinacula. Under the foot, the fibularis longus stretches from the lateral to the medial side in a groove, thus bracing the transverse arch of the foot. The fibularis brevis is attached on the lateral side to the tuberosity of the fifth metatarsal. Together, these two fibularis muscles form the strongest pronators of the foot.[30] The fibularis muscles are highly variable, and several variants can occasionally be present.[31]

Of the posterior muscles three are in the superficial layer. The major plantar flexors, commonly referred to as the triceps surae, are the soleus, which arises on the proximal side of both leg bones, and the gastrocnemius, the two heads of which arises on the distal end of the femur. These muscles unite in a large terminal tendon, the Achilles tendon, which is attached to the posterior tubercle of the calcaneus. The plantaris closely follows the lateral head of the gastrocnemius. Its tendon runs between those of the soleus and gastrocnemius and is embedded in the medial end of the calcaneus tendon.[32]

In the deep layer, the tibialis posterior has its origin on the interosseus membrane and the neighbouring bone areas and runs down behind the medial malleolus. Under the foot it splits into a thick medial part attached to the navicular bone and a slightly weaker lateral part inserted to the three cuneiform bones. The muscle produces simultaneous plantar flexion and supination in the non-weight-bearing leg, and approximates the heel to the calf of the leg. The flexor hallucis longus arises distally on the fibula and on the interosseus membrane from where its relatively thick muscle belly extends far distally. Its tendon extends beneath the flexor retinaculum to the sole of the foot and finally attaches on the base of the last phalanx of the hallux. It plantarflexes the hallux and assists in supination. The flexor digitorum longus, finally, has its origin on the upper part of the tibia. Its tendon runs to the sole of the foot where it forks into four terminal tendon attached to the last phalanges of the four lateral toes. It crosses the tendon of the tibialis posterior distally on the tibia, and the tendon of the flexor hallucis longus in the sole. Distally to its division, the quadratus plantae radiates into it and near the middle phalanges its tendons penetrate the tendons of the flexor digitorum brevis. In the non-weight-bearing leg, it plantar flexes the toes and foot and supinates. In the weight-bearing leg it supports the plantar arch.[25] (For the popliteus, see above.)

Intrinsic

[edit]The intrinsic muscles of the foot, muscles whose bellies are located in the foot proper, are either dorsal (top) or plantar (sole). On the dorsal side, two long extrinsic extensor muscles are superficial to the intrinsic muscles, and their tendons form the dorsal aponeurosis of the toes. The short intrinsic extensors and the plantar and dorsal interossei radiates into these aponeuroses. The extensor digitorum brevis and extensor hallucis brevis have a common origin on the anterior side of the calcaneus, from where their tendons extend into the dorsal aponeuroses of digits 1–4. They act to dorsiflex these digits.[33]

The plantar muscles can be subdivided into three groups associated with three regions: those of the big digit, the little digit, and the region between these two. All these muscles are covered by the thick and dense plantar aponeurosis, which together with two tough septa, form the spaces of the three groups. These muscles and their fatty tissue function as cushions that transmit the weight of the body downward. As a whole, the foot is a functional entity.[34]

The abductor hallucis stretches along the medial edge of the foot, from the calcaneus to the base of the first phalanx of the first digit and the medial sesamoid bone. It is an abductor and a weak flexor, and also helps maintain the arch of the foot. Lateral to the abductor hallucis is the flexor hallucis brevis, which originates from the medial cuneiform bone and from the tendon of the tibialis posterior. The flexor hallucis has a medial and a lateral head inserted laterally to the abductor hallucis. It is an important plantar flexor which comes into prominent use in classical ballet (i.e. for pointe work).[34] The adductor hallucis has two heads; a stronger oblique head which arises from the cuboid and lateral cuneiform bones and the bases of the second and third metatarsals; and a transverse head which arises from the distal ends of the third-fifth metatarsals. Both heads are inserted on the lateral sesamoid bone of the first digit. The muscle acts as a tensor to the arches of the foot, but can also adduct the first digit and plantar flex its first phalanx.[35]

The opponens digiti minimi originates from the long plantar ligament and the plantar tendinous sheath of the fibularis (peroneus) longus and is inserted on the fifth metatarsal. When present, it acts to plantar flex the fifth digit and supports the plantar arch. The flexor digiti minimi arises from the region of base of the fifth metatarsal and is inserted onto the base of the first phalanx of the fifth digit where it is usually merged with the abductor of the first digit. It acts to plantar flex the last digit. The largest and longest muscles of the little toe is the abductor digiti minimi. Stretching from the lateral process of the calcaneus, with a second attachment on the base of the fifth metatarsal, to the base of the fifth digit's first phalanx, the muscle forms the lateral edge of the sole. Except for supporting the arch, it plantar flexes the little toe and also acts as an abductor.[35]

The four lumbricales have their origin on the tendons of the flexor digitorum longus, from where they extend to the medial side of the bases of the first phalanx of digits two-five. Except for reinforcing the plantar arch, they contribute to plantar flexion and move the four digits toward the big toe. They are, in contrast to the lumbricales of the hand, rather variable, sometimes absent and sometimes more than four are present. The quadratus plantae arises with two slips from margins of the plantar surface of the calcaneus and is inserted into the tendon(s) of the flexor digitorum longus, and is known as the "plantar head" of this latter muscle. The three plantar interossei arise with their single heads on the medial side of the third-fifth metatarsals and are inserted on the bases of the first phalanges of these digits. The two heads of the four dorsal interossei arise on two adjacent metatarsals and merge in the intermediary spaces. Their distal attachment is on the bases of the proximal phalanges of the second-fourth digits. The interossei are organized with the second digit as a longitudinal axis; the plantars act as adductors and pull digits 3–5 towards the second digit; while the dorsals act as abductors. Additionally, the interossei act as plantar flexors at the metatarsophalangeal joints. Lastly, the flexor digitorum brevis arises from underneath the calcaneus to insert its tendons on the middle phalanges of digit 2–4. Because the tendons of the flexor digitorum longus run between these tendons, the brevis is sometimes called perforatus. The tendons of these two muscles are surrounded by a tendinous sheath. The brevis acts to plantar flex the middle phalanges.[36]

Flexibility

[edit]Flexibility can be simply defined as the available range of motion (ROM) provided by a specific joint or group of joints.[37] For the most part, exercises that increase flexibility are performed with intentions to boost overall muscle length, reduce the risks of injury and to potentially improve muscular performance in physical activity.[38] Stretching muscles after engagement in any physical activity can improve muscular strength, increase flexibility, and reduce muscle soreness.[39] If limited movement is present within a joint, the "insufficient extensibility" of the muscle, or muscle group, could be restricting the activity of the affected joint.[40]

Stretching

[edit]Stretching prior to strenuous physical activity has been thought to increase muscular performance by extending the soft tissue past its attainable length in order to increase range of motion.[37] Many physically active individuals practice these techniques as a "warm-up" in order to achieve a certain level of muscular preparation for specific exercise movements. When stretching, muscles should feel somewhat uncomfortable but not physically agonizing.

- Plantar flexion: One of the most popular lower leg muscle stretches is the step standing heel raises, which mainly involves the gastrocnemius, soleus, and the Achilles tendon.[41] Standing heel raises allow the individual to activate their calf muscles by standing on a step with toes and forefoot, leaving the heel hanging off the step, and plantar flexing the ankle joint by raising the heel. This exercise is easily modified by holding on to a nearby rail for balance and is generally repeated 5–10 times.

- Dorsiflexion: In order to stretch the anterior muscles of the lower leg, crossover shin stretches work well.[42] This motion will stretch the dorsiflexion muscles, mainly the anterior tibialis, extensor hallucis longus and extensor digitorum longus, by slowly causing the muscles to lengthen as body weight is leaned on the ankle joint by using the floor as resistance against the top of the foot.[42] Crossover shin stretches can vary in intensity depending on the amount of body weight applied on the ankle joint as the individual bends at the knee. This stretch is typically held for 15–30 seconds.

- Eversion and inversion: Stretching the eversion and inversion muscles allows for better range of motion to the ankle joint.[38] Seated ankle elevations and depressions will stretch the fibularis (peroneus) and tibilalis muscles that are associated with these movements as they lengthen. Eversion muscles are stretched when the ankle becomes depressed from the starting position. In like manner, the inversion muscles are stretched when the ankle joint becomes elevated. Throughout this seated stretch, the ankle joint is to remain supported while depressed and elevated with the ipsilateral (same side) hand in order to sustain the stretch for 10–15 seconds. This stretch will increase overall eversion and inversion muscle group length and provide more flexibility to the ankle joint for larger range of motion during activity.[37][38]

Blood supply

[edit]The arteries of the leg are divided into a series of segments.

In the pelvis area, at the level of the last lumbar vertebra, the abdominal aorta, a continuation the descending aorta, splits into a pair of common iliac arteries. These immediately split into the internal and external iliac arteries, the latter of which descends along the medial border of the psoas major to exits the pelvis area through the vascular lacuna under the inguinal ligament.[43]

The artery enters the thigh as the femoral artery which descends the medial side of the thigh to the adductor canal. The canal passes from the anterior to the posterior side of the limb where the artery leaves through the adductor hiatus and becomes the popliteal artery. On the back of the knee the popliteal artery runs through the popliteal fossa to the popliteal muscle where it divides into anterior and posterior tibial arteries.[43]

In the lower leg, the anterior tibial enters the extensor compartment near the upper border of the interosseus membrane to descend between the tibialis anterior and the extensor hallucis longus. Distal to the superior and extensor retinacula of the foot it becomes the dorsal artery of the foot. The posterior tibial forms a direct continuation of the popliteal artery which enters the flexor compartment of the lower leg to descend behind the medial malleolus where it divides into the medial and lateral plantar arteries, of which the posterior branch gives rise to the fibular artery.[43]

For practical reasons the lower limb is subdivided into somewhat arbitrary regions:[44] The regions of the hip are all located in the thigh: anteriorly, the subinguinal region is bounded by the inguinal ligament, the sartorius, and the pectineus and forms part of the femoral triangle which extends distally to the adductor longus. Posteriorly, the gluteal region corresponds to the gluteus maximus. The anterior region of the thigh extends distally from the femoral triangle to the region of the knee and laterally to the tensor fasciae latae. The posterior region ends distally before the popliteal fossa. The anterior and posterior regions of the knee extend from the proximal regions down to the level of the tuberosity of the tibia. In the lower leg the anterior and posterior regions extend down to the malleoli. Behind the malleoli are the lateral and medial retromalleolar regions and behind these is the region of the heel. Finally, the foot is subdivided into a dorsal region superiorly and a plantar region inferiorly.[44]

Veins

[edit]

The veins are subdivided into three systems. The deep veins return approximately 85 percent of the blood and the superficial veins approximately 15 percent. A series of perforator veins interconnect the superficial and deep systems. In the standing posture, the veins of the leg have to handle an exceptional load as they act against gravity when they return the blood to the heart. The venous valves assist in maintaining the superficial to deep direction of the blood flow.[45]

Superficial veins:

Deep veins:

- Femoral vein, whose segment is the common femoral vein

- Popliteal vein

- Anterior tibial vein

- Posterior tibial vein

- Fibular vein

Nerve supply

[edit]The sensory and motor innervation to the lower limb is supplied by the lumbosacral plexus, which is formed by the ventral rami of the lumbar and sacral spinal nerves with additional contributions from the subcostal nerve (T12) and coccygeal nerve (Co1). Based on distribution and topography, the lumbosacral plexus is subdivided into the lumbar plexus (T12-L4) and the Sacral plexus (L5-S4); the latter is often further subdivided into the sciatic and pudendal plexuses:[46]

The lumbar plexus is formed lateral to the intervertebral foramina by the ventral rami of the first four lumbar spinal nerves (L1-L4), which all pass through psoas major. The larger branches of the plexus exit the muscle to pass sharply downward to reach the abdominal wall and the thigh (under the inguinal ligament); with the exception of the obturator nerve which pass through the lesser pelvis to reach the medial part of the thigh through the obturator foramen. The nerves of the lumbar plexus pass in front of the hip joint and mainly support the anterior part of the thigh.[46]

The iliohypogastric (T12-L1) and ilioinguinal nerves (L1) emerge from the psoas major near the muscle's origin, from where they run laterally downward to pass anteriorly above the iliac crest between the transversus abdominis and abdominal internal oblique, and then run above the inguinal ligament. Both nerves give off muscular branches to both these muscles. Iliohypogastric supplies sensory branches to the skin of the lateral hip region, and its terminal branch finally pierces the aponeurosis of the abdominal external oblique above the inguinal ring to supply sensory branches to the skin there. Ilioinguinalis exits through the inguinal ring and supplies sensory branches to the skin above the pubic symphysis and the lateral portion of the scrotum.[47]

The genitofemoral nerve (L1, L2) leaves psoas major below the two former nerves, immediately divides into two branches that descends along the muscle's anterior side. The sensory femoral branch supplies the skin below the inguinal ligament, while the mixed genital branch supplies the skin and muscles around the sex organ. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (L2, L3) leaves psoas major laterally below the previous nerve, runs obliquely and laterally downward above the iliacus, exits the pelvic area near the iliac spine, and supplies the skin of the anterior thigh.[47]

The obturator nerve (L2-L4) passes medially behind psoas major to exit the pelvis through the obturator canal, after which it gives off branches to obturator externus and divides into two branches passing behind and in front of adductor brevis to supply motor innervation to all the other adductor muscles. The anterior branch also supplies sensory nerves to the skin on a small area on the distal medial aspect of the thigh.[48] The femoral nerve (L2-L4) is the largest and longest of the nerves of the lumbar plexus. It supplies motor innervation to iliopsoas, pectineus, sartorius, and quadriceps; and sensory branches to the anterior thigh, medial lower leg, and posterior foot.[48]

The nerves of the sacral plexus pass behind the hip joint to innervate the posterior part of the thigh, most of the lower leg, and the foot.[46] The superior (L4-S1) and inferior gluteal nerves (L5-S2) innervate the gluteus muscles and the tensor fasciae latae. The posterior femoral cutaneous nerve (S1-S3) contributes sensory branches to the skin on the posterior thigh.[49] The sciatic nerve (L4-S3), the largest and longest nerve in the human body, leaves the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen. In the posterior thigh it first gives off branches to the short head of the biceps femoris and then divides into the tibial (L4-S3) and common fibular nerves (L4-S2). The fibular nerve continues down on the medial side of biceps femoris, winds around the fibular neck and enters the front of the lower leg. There it divides into a deep and a superficial terminal branch. The superficial branch supplies the fibularis muscles and the deep branch enters the extensor compartment; both branches reaches into the dorsal foot. In the thigh, the tibial nerve gives off branches to semitendinosus, semimembranosus, adductor magnus, and the long head of the biceps femoris. The nerve then runs straight down the back of the leg, through the popliteal fossa to supply the ankle flexors on the back of the lower leg and then continues down to supply all the muscles in the sole of the foot.[50] The pudendal nerve (S2-S4) and coccygeal plexus (S5-Co)[51] supply the muscles of the pelvic floor and the surrounding skin.[52]

The lumbosacral trunk is a communicating branch passing between the sacral and lumbar plexuses containing ventral fibers from L4. The coccygeal nerve, the last spinal nerve, emerges from the sacral hiatus, unites with the ventral rami of the two last sacral nerves, and forms the coccygeal plexus.[46]

Lower leg and foot

[edit]The lower leg and ankle need to keep exercised and moving well as they are the base of the whole body. The lower extremities must be strong in order to balance the weight of the rest of the body, and the gastrocnemius muscles take part in much of the blood circulation.

Exercises

[edit]Isometric and standard

[edit]There are a number of exercises that can be done to strengthen the lower leg. For example, in order to activate plantar flexors in the deep plantar flexors one can sit on the floor with the hips flexed, the ankle neutral with knees fully extended as they alternate pushing their foot against a wall or platform. This kind of exercise is beneficial as it hardly causes any fatigue.[53] Another form of isometric exercise for the gastrocnemius would be seated calf raises which can be done with or without equipment. One can be seated at a table with their feet flat on the ground, and then plantar flex both ankles so that the heels are raised off the floor and the gastrocnemius flexed.[54] An alternate movement could be heel drop exercises with the toes being propped on an elevated surface—as an opposing movement this would improve the range of motion.[55] One-legged toe raises for the gastrocnemius muscle can be performed by holding one dumbbell in one hand while using the other for balance, and then standing with one foot on a plate. The next step would be to plantar flex and keep the knee joint straight or flexed slightly. The triceps surae is contracted during this exercise.[56] Stabilization exercises like the BOSU ball squat are also important especially as they assist in the ankles having to adjust to the ball's form in order to balance.[57]

Strengthening the lower leg is essential for improving overall leg stability, balance, and injury prevention. Several effective exercises target the muscles in the lower leg, including the calves, tibialis anterior, and other supporting muscles. Calf raises are a foundational exercise: standing with feet hip-width apart, you raise your heels off the ground and lower them back down, effectively strengthening the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles. Seated calf raises, performed while sitting with a weight on your knees, focus specifically on the soleus muscle, which is crucial for endurance activities.

To target the tibialis anterior, toe raises are highly effective. Standing with feet flat, you lift your toes off the ground while keeping your heels planted, then lower them back down. For improved ankle mobility, ankle circles—rotating your ankle clockwise and counterclockwise while seated or standing—are beneficial. Similarly, heel walks, where you walk on your heels with toes lifted, strengthen the tibialis anterior and enhance balance.

Using equipment like resistance bands can add versatility to your routine. For example, looping a band around your foot and pulling it toward you strengthens various lower leg muscles. Jump rope is another excellent option, enhancing calf strength, coordination, and cardiovascular fitness. Finally, box jumps, where you jump onto a sturdy box or platform, develop explosive strength in the calves and lower legs.

Incorporating these exercises into your workout routine can significantly improve lower leg strength and stability. Begin with a proper warm-up and gradually increase intensity to prevent injury. If you have specific fitness goals or medical conditions, consulting a fitness professional or physical therapist is recommended.

Clinical significance

[edit]

Lower leg injury

[edit]Lower leg injuries are common while running or playing sports. About 10% of all injuries in athletes involve the lower extremities.[58] The majority of athletes sprain their ankles; this is mainly caused by the increased loads onto the feet when they move into the foot down or in an outer ankle position. All areas of the foot, which are the forefoot, midfoot, and rearfoot, absorb various forces while running and this can also lead to injuries.[59] Running and various activities can cause stress fractures, tendinitis, musculotendinous injuries, or any chronic pain to our lower extremities such as the tibia.[58]

Types of activities

[edit]Injuries to quadriceps or hamstrings are caused by the constant impact loads to the legs during activities, such as kicking a ball. While doing this type of motion, 85% of that shock is absorbed to the hamstrings; this can cause strain to those muscles.[59]

- Jumping – is another risk because if the legs do not land properly after an initial jump, there may be damage to the meniscus in the knees, sprain to the ankle by everting or inverting the foot, or damage to the Achilles tendon and gastrocnemius if there is too much force while plantar flexing.[59]

- Weight lifting – such as the improperly performed deep squat, is also dangerous to the lower limbs, because the exercise can lead to an overextension, or an outstretch, of our ligaments in the knee and can cause pain over time.[59]

- Running – the most common activity associated with lower leg injury. There is constant pressure and stress being put on the feet, knees, and legs while running by gravitational force. Muscle tears in our legs or pain in various areas of the feet can be a result of poor biomechanics of running.

Running

[edit]The most common injuries in running involve the knees and the feet. Various studies have focused on the initial cause of these running related injuries and found that there are many factors that correlate to these injuries. Female distance runners who had a history of stress fracture injuries had higher vertical impact forces than non-injured subjects.[60] The large forces onto the lower legs were associated with gravitational forces, and this correlated with patellofemoral pain or potential knee injuries.[60] Researchers have also found that these running-related injuries affect the feet as well, because runners with previous injuries showed more foot eversion and over-pronation while running than non-injured runners.[61] This causes more loads and forces on the medial side of the foot, causing more stress on the tendons of the foot and ankle.[61] Most of these running injuries are caused by overuse: running longer distances weekly for a long duration is a risk for injuring the lower legs.[62]

Prevention tools

[edit]Voluntary stretches to the legs, such as the wall stretch, condition the hamstrings and the calf muscle to various movements before vigorously working them.[63] The environment and surroundings, such as uneven terrain, can cause the feet to position in an unnatural way, so wearing shoes that can absorb forces from the ground's impact and allow for stabilizing the feet can prevent some injuries while running as well. Shoes should be structured to allow friction-traction at the shoe surface, space for different foot-strike stresses, and for comfortable, regular arches for the feet.[59]

Summary

[edit]The chance of damaging our lower extremities will be reduced by having knowledge about some activities associated with lower leg injury and developing a correct form of running, such as not over-pronating the foot or overusing the legs. Preventative measures, such as various stretches, and wearing appropriate footwear, will also reduce injuries.

Fracture

[edit]A fracture of the leg can be classified according to the involved bone into:

- Femoral fracture (in the upper leg)

- Crus fracture (in the lower leg)

Pain management

[edit]Lower leg and foot pain management is critical in reducing the progression of further injuries, uncomfortable sensations and limiting alterations while walking and running. Most individuals suffer from various pains in their lower leg and foot due to different factors. Muscle inflammation, strain, tenderness, swelling and muscle tear from muscle overuse or incorrect movement are several conditions often experienced by athletes and the common public during and after high impact physical activities. Therefore, suggested pain management mechanisms are provided to reduce pain and prevent the progression of injury.

Plantar fasciitis

[edit]A plantar fasciitis foot stretch is one of the recommended methods to reduce pain caused by plantar fasciitis (Figure 1). To do the plantar fascia stretch, while sitting in a chair place the ankle on the opposite knee and hold the toes of the impaired foot, slowly pulling back. The stretch should be held for approximately ten seconds, three times per day.[64]

Medial tibial stress syndrome (shin splint)

[edit]Several methods can be utilized to help control pain caused by shin splints. Placing ice on the affected area prior to and after running will aid in reducing pain. In addition, wearing orthoses (orthotic devices), including a neoprene sleeve (Figure 2) and wearing appropriate footwear such as a foot arch can help to eliminate the condition. Stretching and strengthening of the anterior tibia or medial tibia by performing exercises of plantar and dorsi flexors such as calf stretch can also help in easing the pain.[65]

Achilles tendinopathy

[edit]There are numerous appropriate approaches to handling pain resulting from Achilles tendinitis. The primary action is to rest. Activities that do not provide additional stress to the affected tendon are also recommended. Wearing orthothics or prostheses will provide cushion and will prevent the affected Achilles tendon from experiencing further stress when walking and performing therapeutic stretches. A few stretch modalities or eccentric exercises such as toe extension and flexion and calf and heel stretch are beneficial in lowering pain with Achilles tendinopathy patients (Figure 4)[66]

Society and culture

[edit]

In Norse mythology, the race of Jotuns was born from the legs of Ymir. In Finnic mythology, the Earth was created from the shards of the egg of a goldeneye that fell from the knees of Ilmatar. While this story isn't found in other Finno-Ugric mythologies, Pavel Melnikov-Pechersky has noted several times that the beauty of legs is commonly mentioned in Mordvin mythology as a characteristic of both female mythological characters and real Erzyan and Mokshan women.

In medieval Europe, showing legs was one of the biggest taboos for women, especially the ones with a high social status. In Victorian England several centuries later legs were not to be mentioned at all (not only human ones, but even those of a table or a piano), and referred to as "limbs" instead.[67] Miniskirts and other clothing that reveal legs first became popular in mid-20th century science fiction. Since then, it became mainstream in Western cultures, with female legs frequently being focused on in films, TV ads, music videos, dance shows and various kinds of sports (i.e. ice skating or women's gymnastics).[68]

Many men who are attracted to female legs tend to regard them aesthetically almost as much as they do sexually, perceiving legs as more elegant, suggestive, sensual, or seductive (especially with clothing that makes legs easy to be revealed and concealed), whereas female breasts or buttocks are viewed as much more "in your face" sexual.[68] That said, legs (especially the inside of the upper leg that has the most sensitive and delicate skin) are considered to be one of the most sexualized elements of a woman's body, especially in Hollywood movies.[69]

Both men and women generally consider long legs attractive,[70] which may explain the preference for tall fashion models. Men also tend to favor women who have a higher leg length to body ratio, but the opposite is true of women's preferences in men.[68]

Adolescent and adult women in many Western cultures often remove the hair from their legs.[71] Toned, tanned, shaved legs are sometimes perceived as a sign of youthfulness and are often considered attractive in these cultures.

Men generally do not shave their legs in any culture. However, leg-shaving is a generally accepted practice in modeling. It is also fairly common in sports where the hair removal makes the athlete appreciably faster by reducing drag; the most common case of this is competitive swimming.[72]

Image gallery

[edit]-

Surface anatomy of human leg

-

Muscles of the gluteal and posterior femoral regions

-

Small saphenous vein and its tributaries

-

The popliteal, posterior tibial, and peroneal arteries

-

Nerves of the right lower extremity, posterior view

-

Leg bones

See also

[edit]- Distraction osteogenesis (leg lengthening)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Muscolino, Joseph (2016). "1 - Basic Kinesiology Terminology". The Muscular System Manual: The Skeletal Muscles of the Human Body. Elsevier. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-323-32771-8.

- ^ a b Striedter, Georg; Bullock, Theodore; Preuss, Todd; Rubenstein, John (2016). "3.12 - Evolved Mechanisms of High-Level Visual Perception in Primates". Evolution of Nervous Systems. Elsevier. pp. 222–226. ISBN 978-0-128-04096-6.

- ^ a b Hefti, Fritz (2015). "4 - Spine, trunk". Pediatric Orthopedics in Practice (2 ed.). Springer Science+Business Media. p. 87. doi:10.1007/978-3-662-46810-4. ISBN 978-3-662-46810-4.

- ^ Shultz SJ, Nguyen AD, Schmitz RJ (2008). "Differences in lower extremity anatomical and postural characteristics in males and females between maturation groups". J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 38 (3): 137–49. doi:10.2519/jospt.2008.2645. PMID 18383647.

- ^ "Lower leg anatomy".

- ^ Tortora, Gerard; Nielsen, Mark (2020). "27 - Surface Anatomy". Principles of Human Anatomy. John Wiley & Sons. p. 995. ISBN 978-1-119-66286-0.

- ^ McDowell, Julie (2010). "11 - The Skeletal System". Encyclopedia of Human Body Systems. Vol. 2. ABC-CLIO. p. 587. ISBN 978-0-313-39176-7.

- ^ Patton, Kevin (2015). "1 - Organization of the Body". Anatomy and Physiology. Elsevier. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-323-34139-4. OCLC 928962548.

- ^ Soames, Roger; Palastanga, Nigel (2018). "3 - Lower limb". Anatomy and Human Movement (7 ed.). Elsevier. pp. 220–222. ISBN 978-0-702-07259-8.

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p. 360

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p. 361

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p. 362

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 196

- ^ a b Platzer (2004), pp. 244–47

- ^ a b Platzer, (2004), p. 232

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 234

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 236

- ^ Moore, Keith L. (2018). Clinically oriented anatomy (Eighth ed.). Philadelphia. p. 728. ISBN 9781496347213.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Platzer (2004), p. 238

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 240

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 242

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 252

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 248

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 250

- ^ a b Platzer (2004), p. 264

- ^ a b Platzer (2004), p. 266

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 256

- ^ Starkey, Chad; Brown, Sara (2015). "8 - Foot and Toe Pathologies". Examination of Orthopedic & Athletic Injuries (4 ed.). F. A. Davis Company. p. 175. ISBN 978-0-8036-4503-5.

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 258

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 260

- ^ Chaitow (2000), p. 554

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 262

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 268

- ^ a b Platzer (2004), p. 270

- ^ a b Platzer (2004), p. 272

- ^ Platzer (2004), p. 274

- ^ a b c Alter, M. J. (2004). Science of Flexibility (3rd ed., pp. 1–6). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- ^ a b c Lower Extremity Stretching Home Exercise Program (April 2010). In Aurora Healthcare.

- ^ Nelson, A. G., & Kokkonen, J. (2007). Stretching Anatomy. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- ^ Weppler, C. H., & Magnusson, S. P. (March 2010). Increasing Muscle Extensibility: A Matter of Increasing Length or Modifying Sensation. Physical Therapy, 90, 438–49.

- ^ Roth, E. Step Stretch for the Foot. AZ Central. http://healthyliving.azcentral.com/step-stretch-foot-18206.html Archived 5 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Shea, K. (12 August 2013). Shin Stretches for Runners. Livestrong. http://www.livestrong.com/article/353394-shin-stretches-for-runners/

- ^ a b c Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p. 464

- ^ a b Platzer (2004), p. 412

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), pp. 466–67

- ^ a b c d Thieme Atlas of anatomy (2006), pp. 470–71

- ^ a b Thieme Atlas of anatomy (2006), pp. 472–73

- ^ a b Thieme Atlas of anatomy (2006), pp. 474–75

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), p. 476

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), pp. 480–81

- ^ Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, A. Wayne; Mitchell, Adam W. M.; Tibbitts, Richard; Richardson, Paul (14 July 2014). Gray's Atlas of Anatomy. Churchill Livingstone. p. 252. ISBN 978-1-4557-4802-0.

- ^ Thieme Atlas of Anatomy (2006), pp. 482–83

- ^ Masood, Tahir; Bojsen-Møller, Jens; Kalliokoski, Kari K.; Kirjavainen, Anna; Äärimaa, Ville; Peter Magnusson, S.; Finni, Taija (2014). "Differential contributions of ankle plantarflexors during submaximal isometric muscle action: A PET and EMG study" (PDF). Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology. 24 (3): 367–74. doi:10.1016/j.jelekin.2014.03.002. hdl:11250/284479. PMID 24717406. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 April 2019.

- ^ Jeong, Siwoo; Lee, Dae-Yeon; Choi, Dong-Sung; Lee, Hae-Dong (2014). "Acute effect of heel-drop exercise with varying ranges of motion on the gastrocnemius aponeurosis-tendon's mechanical properties". Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology. 24 (3): 375–79. doi:10.1016/j.jelekin.2014.03.004. PMID 24717405.

- ^ Starrett, Kelly; Cordoza, Glen (2013). Becoming a Supple Leopard: The Ultimate Guide to Resolving Pain, Preventing Injury, and Optimizing Athletic Performance. Las Vegas: Victory Belt. p. 391. ISBN 978-1-936608-58-4.

- ^ Delavier, Frédéric (2010). "One-Leg Toe Raises". Strength Training Anatomy. Human Kinetics. pp. 150–51. ISBN 978-0-7360-9226-5.

- ^ Clark, Micheal A.; Lucett, Scott C.; Corn, Rodney J., eds. (2008). "Ball Squat, Curl to Press". NASM Essentials of Personal Fitness Training. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-7817-8291-3.

- ^ a b Kjaer, M., Krogsgaard, M., & Magnusson, P. (Eds.). (2008). Textbook of Sports Medicine Basic Science and Clinical Aspects of Sports Injury and Physical Activity. Chichester, GBR: John Wiley & Sons.[page needed]

- ^ a b c d e Bartlett, R. (1999). Sports Biomechanics: Preventing Injury and Improving Performance. London, GBR: Spon Press.[page needed]

- ^ a b Hreljac, Alan; Ferber, Reed (2006). "A biomechanical perspective of predicting injury risk in running: review article". International Sportmed Journal. 7 (2): 98–108. hdl:10520/EJC48590.

- ^ a b Willems, T.M.; De Clercq, D.; Delbaere, K.; Vanderstraeten, G.; De Cock, A.; Witvrouw, E. (2006). "A prospective study of gait related risk factors for exercise-related lower leg pain". Gait & Posture. 23 (1): 91–98. doi:10.1016/j.gaitpost.2004.12.004. PMID 16311200.

- ^ Malisoux, Laurent; Nielsen, Rasmus Oestergaard; Urhausen, Axel; Theisen, Daniel (2014). "A step towards understanding the mechanisms of running-related injuries". Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 18 (5): 523–28. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2014.07.014. PMID 25174773.

- ^ Spiker, Ted (7 March 2007). "Build Stronger Lower Legs". Runner's World.

- ^ "Easing the pain of plantar fasciitis. To relieve heel pain, simple therapies may be all you need". Harvard Women's Health Watch. 14 (12): 4–5. 2007. PMID 17722355.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Garl, Tim (2004). "Lower Leg Pain in Basketball Players". FIBA Assist Magazine: 61–62.

- ^ Knobloch, Karsten; Schreibmueller, Louisa; Longo, Umile Giuseppe; Vogt, Peter M. (2008). "Eccentric exercises for the management of tendinopathy of the main body of the Achilles tendon with or without the AirHeel Brace. A randomized controlled trial. A: Effects on pain and microcirculation". Disability & Rehabilitation. 30 (20–22): 1685–91. doi:10.1080/09638280701786658. PMID 18720121. S2CID 36134550.

- ^ Swati Gautam. "When legs were taboo". Telegraph India. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ a b c Leon F. Seltzer. "Why Do Men Find Women's Legs So Alluring?". Psychology Today. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ Smith, Lauren E., «A Leg Up For Women? Stereotypes of Female Sexuality in American Culture through an Analysis of Iconic Film Stills of Women's Legs Archived 16 December 2023 at the Wayback Machine». Senior Theses, Trinity College, Hartford, CT 2013.

- ^ Ian Sample (17 January 2008). "Why men and women find longer legs more attractive". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 November 2023.

- ^ Phil Edwards (22 May 2015). "How the beauty industry convinced women to shave their legs". Vox. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ Michelle Martin. "Why Men Should Shave Their Legs". TriathlonOz. Archived from the original on 7 December 2023. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

Literature specified by multiple pages above:

- Chaitow, Leon; Walker DeLany, Judith (2000). Clinical Application of Neuromuscular Techniques: The Lower Body. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 0-443-06284-6. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- consulting editors, Lawrence M. Ross, Edward D. Lamperti; authors, Michael Schuenke, Erik Schulte, Udo Schumacher. (2006). Thieme Atlas of Anatomy: General Anatomy and Musculoskeletal System. Thieme. ISBN 1-58890-419-9.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Platzer, Werner (2004). Color Atlas of Human Anatomy, Vol. 1: Locomotor System (5th ed.). Thieme. ISBN 3-13-533305-1.

External links

[edit]- Interactive images at InnerBody

- Leg Anatomy detailed guide for medical college students and medical professionals.