Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Space travel in science fiction

View on Wikipedia

Space travel,[1]: 69 [2]: 209–210 [3]: 511–512 or space flight[2]: 200–201 [4] (less often, starfaring or star voyaging[2]: 217, 220 ) is a science fiction theme that has captivated the public and is almost archetypal for science fiction.[4] Space travel, interplanetary or interstellar, is usually performed in space ships, and spacecraft propulsion in various works ranges from the scientifically plausible to the totally fictitious.[1]: 8, 69–77

While some writers focus on realistic, scientific, and educational aspects of space travel, other writers see this concept as a metaphor for freedom, including "free[ing] mankind from the prison of the solar system".[4] Though the science fiction rocket has been described as a 20th-century icon,[5]: 744 according to The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction "The means by which space flight has been achieved in sf – its many and various spaceships – have always been of secondary importance to the mythical impact of the theme".[4] Works related to space travel have popularized such concepts as time dilation, space stations, and space colonization.[1]: 69–80 [5]: 743

While generally associated with science fiction, space travel has also occasionally featured in fantasy, sometimes involving magic or supernatural entities such as angels.[a][5]: 742–743

History

[edit]

A classic, defining trope of the science fiction genre is that the action takes place in space, either aboard a spaceship or on another planet.[3]: 511–512 [4] Early works of science fiction, termed "proto SF" – such as novels by 17th-century writers Francis Godwin and Cyrano de Bergerac, and by astronomer Johannes Kepler – include "lunar romances", much of whose action takes place on the Moon.[b][4] Science fiction critic George Slusser also pointed to Christopher Marlowe's Doctor Faustus (1604) – in which the main character is able to see the entire Earth from high above – and noted the connections of space travel to earlier dreams of flight and air travel, as far back as the writings of Plato and Socrates.[5]: 742 In such a grand view, space travel, and inventions such as various forms of "star drive", can be seen as metaphors for freedom, including "free[ing] mankind from the prison of the solar system".[4]

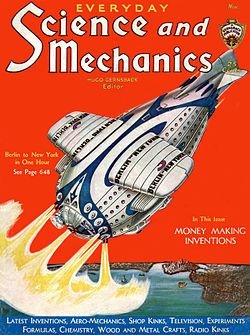

In the following centuries, while science fiction addressed many aspects of futuristic science as well as space travel, space travel proved the more influential with the genre's writers and readers, evoking their sense of wonder.[1]: 69 [4] Most works were mainly intended to amuse readers, but a small number, often by authors with a scholarly background, sought to educate readers about related aspects of science, including astronomy; this was the motive of the influential American editor Hugo Gernsback, who dubbed it "sugar-coated science" and "scientifiction".[1]: 70 Science fiction magazines, including Gernsback's Science Wonder Stories, alongside works of pure fiction, discussed the feasibility of space travel; many science fiction writers also published nonfiction works on space travel, such as Willy Ley's articles and David Lasser's book, The Conquest of Space (1931).[1]: 71 [5]: 743

From the late 19th and early 20th centuries on, there was a visible distinction between the more "realistic", scientific fiction (which would later evolve into hard sf)[8]), whose authors, often scientists like Konstantin Tsiolkovsky and Max Valier, focused on the more plausible concept of interplanetary travel (to the Moon or Mars); and the more grandiose, less realistic stories of "escape from Earth into a Universe filled with worlds", which gave rise to the genre of space opera, pioneered by E. E. Smith[c] and popularized by the television series Star Trek, which debuted in 1966.[4][5]: 743 [9] This trend continues to the present, with some works focusing on "the myth of space flight",[d] and others on "realistic examination of space flight";[e] the difference can be described as that between the authors' concern with the "imaginative horizons rather than hardware".[4]

The successes of 20th-century space programs, such as the Apollo 11 Moon landing, have often been described as "science fiction come true" and have served to further "demystify" the concept of space travel within the Solar System. Henceforth writers who wanted to focus on the "myth of space travel" were increasingly likely to do so through the concept of interstellar travel.[4] Edward James wrote that many science fiction stories have "explored the idea that without the constant expansion of humanity, and the continual extension of scientific knowledge, comes stagnation and decline."[10]: 252 While the theme of space travel has generally been seen as optimistic,[3]: 511–512 some stories by revisionist authors, often more pessimistic and disillusioned, juxtapose the two types, contrasting the romantic myth of space travel with a more down-to-Earth reality.[f][4] George Slusser suggests that "science fiction travel since World War II has mirrored the United States space program: anticipation in the 1950s and early 1960s, euphoria into the 1970s, modulating into skepticism and gradual withdrawal since the 1980s."[5]: 743

On the screen, the 1902 French film A Trip to the Moon, by Georges Méliès, described as the first science fiction film, linked special effects to depictions of spaceflight.[5]: 744 [11] With other early films, such as Woman in the Moon (1929) and Things to Come (1936), it contributed to an early recognition of the rocket as the iconic, primary means of space travel, decades before space programs began.[5]: 744 Later milestones in film and television include the Star Trek series and films, and the film 2001: A Space Odyssey by Stanley Kubrick (1968), which visually advanced the concept of space travel, allowing it to evolve from the simple rocket toward a more complex space ship.[5]: 744 Stanley Kubrick's 1968 epic film featured a lengthy sequence of interstellar travel through a mysterious "star gate". This sequence, noted for its psychedelic special effects conceived by Douglas Trumbull, influenced a number of later cinematic depictions of superluminal and hyperspatial travel, such as Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979).[12]: 159 [13] I

Means of travel

[edit]

Generic terms for engines enabling science fiction spacecraft propulsion include "space drive" and "star drive".[g][2]: 198, 216 In 1977 The Visual Encyclopedia of Science Fiction listed the following means of space travel: anti-gravity,[h] atomic (nuclear), bloater,[i] cannon one-shot,[j] Dean drive,[k] faster-than-light (FTL), hyperspace,[l] inertialess drive,[m][1]: 75 ion thruster,[n] photon rocket, plasma propulsion engine, Bussard ramjet,[o] R. force,[p] solar sail,[q] spindizzy,[r] and torchship.[s][1]: 8, 69–77

The 2007 Brave New Words: The Oxford Dictionary of Science Fiction lists the following terms related to the concept of space drive: gravity drive,[t] hyperdrive,[u] ion drive, jump drive,[v] overdrive, ramscoop (a synonym for ram-jet), reaction drive,[w] stargate,[x] ultradrive, warp drive[y] and torchdrive.[2]: 94, 141, 142, 253 Several of these terms are entirely fictitious or are based on "rubber science", while others are based on real scientific theories.[1]: 8, 69–77 [2]: 142 Many fictitious means of travelling through space, in particular, faster than light travel, tend to go against the current understanding of physics, in particular, the theory of relativity.[17]: 68–69 Some works sport numerous alternative star drives; for example the Star Trek universe, in addition to its iconic "warp drive", has introduced concepts such as "transwarp", "slipstream" and "spore drive", among others.[18]

Many, particularly early, writers of science fiction did not address means of travel in much detail, and many writings of the "proto-SF" era were disadvantaged by their authors' living in a time when knowledge of space was very limited — in fact, many early works did not even consider the concept of vacuum and instead assumed that an atmosphere of sorts, composed of air or "aether", continued indefinitely.[z][4] Highly influential in popularizing the science of science fiction was the 19th-century French writer Jules Verne, whose means of space travel in his 1865 novel, From the Earth to the Moon (and its sequel, Around the Moon), was explained mathematically, and whose vehicle — a gun-launched space capsule — has been described as the first such vehicle to be "scientifically conceived" in fiction.[aa][4][1]: 69 [5]: 743 Percy Greg's Across the Zodiac (1880) featured a spaceship with a small garden, an early precursor of hydroponics.[1]: 69 Another writer who attempted to merge concrete scientific ideas with science fiction was the turn-of-the-century Russian writer and scientist, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, who popularized the concept of rocketry.[4][19][ab] George Mann mentions Robert A. Heinlein's Rocket Ship Galileo (1947) and Arthur C. Clarke's Prelude to Space (1951) as early, influential modern works that emphasized the scientific and engineering aspects of space travel.[3]: 511–512 From the 1960s on, growing popular interest in modern technology also led to increasing depictions of interplanetary spaceships based on advanced plausible extensions of real modern technology.[ac][3]: 511–512 The Alien franchise features ships with ion propulsion, a developing technology at the time that would be used years later in the Deep Space 1, Hayabusa 1 and SMART-1 spacecraft.[20]

Interstellar travel

[edit]Slower than light

[edit]With regard to interstellar travel, in which faster-than-light speeds are generally considered unrealistic, more realistic depictions of interstellar travel have often focused on the idea of "generation ships" that travel at sub-light speed for many generations before arriving at their destinations.[ad] Other scientifically plausible concepts of interstellar travel include suspended animation[ae] and, less often, ion drive, solar sail, Bussard ramjet, and time dilation.[af][1]: 74

Faster than light

[edit]

Some works discuss Einstein's general theory of relativity and challenges that it faces from quantum mechanics, and include concepts of space travel through wormholes or black holes.[ag][3]: 511–512 Many writers, however, gloss over such problems, introducing entirely fictional concepts such as hyperspace (also, subspace, nulspace, overspace, jumpspace, or slipstream) travel using inventions such as hyperdrive, jump drive, warp drive, or space folding.[ah][1]: 75 [3]: 511–512 [16][22][15][21]: 214 Invention of completely made-up devices enabling space travel has a long tradition — already in the early 20th century, Verne criticized H. G. Wells' The First Men in the Moon (1901) for abandoning realistic science (his spaceship relied on anti-gravitic material called "cavorite").[1]: 69 [5]: 743 Of fictitious drives, by the mid-1970s the concept of hyperspace travel was described as having achieved the most popularity, and would subsequently be further popularized — as hyperdrive — through its use in the Star Wars franchise.[1]: 75 [22] While the fictitious drives "solved" problems related to physics (the difficulty of faster-than-light travel), some writers introduce new wrinkles — for example, a common trope involves the difficulty of using such drives in close proximity to other objects, in some cases allowing their use only beginning from the outskirts of the planetary systems.[ai][1]: 75–76

While usually the means of space travel is just a means to an end, in some works, particularly short stories, it is a central plot device. These works focus on themes such as the mysteries of hyperspace, or the consequences of getting lost after an error or malfunction.[1]: 74–75 [aj]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ For example, C.S. Lewis' Perelandra (1942); Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's The Little Prince (1943); the 1988 film The Adventures of Baron Munchausen; and Diana Wynne Jones' 2000 novel Year of the Griffin.[5]: 742

- ^ Somnium (1634), The Man in the Moone (1638), Comical History of the States and Empires of the Moon (1657).[6][7][1]: 69 See also A True Story (c. 2nd century).

- ^ with his Skylark series, which debuted in 1928,[4]

- ^ In addition to space opera, this genre includes Robert A. Heinlein's The Man Who Sold the Moon (1950) and James Blish's short story, "Surface Tension" (1952).[4]

- ^ Examples include Stephen Baxter's novel Voyage (1996) and Andy Weir's novel The Martian (2011).[4]

- ^ Examples include Nigel Balchin's Kings of Infinite Space (1967), Barry N. Malzberg's The Falling Astronauts (1971), and Dan Simmons's Phases of Gravity (1989)

- ^ The term "space drive" was used as early as 1932 (John W. Campbell, Invaders from Infinite); and "star drive", in 1948 (Paul Anderson, Genius). "Space drive" is the more generic, whereas "star drive" implies the capability of interstellar travel.[2]: 198, 216

- ^ An early concept, introduced by Daniel Defoe in The Consolidator (1705) and also used in H. G. Wells' The First Men in the Moon (1901). Some writers and inventors gave unique names to their anti-gravity drives — for example, the Dean drive or James Blish's spindizzy.[1]: 69, 76

- ^ A term invented by Harry Harrison in his Bill, the Galactic Hero (1965)[1]: 108

- ^ A classic idea popularized in the 19th century by Jules Verne's From the Earth to the Moon (1865).[1]: 69

- ^ Dean drive is a real-world, patented invention that promised to generate an anti-gravity force. Before slipping into obscurity, it was briefly promoted by American sci-fi magazine editor John W. Campbell in one of his editorials.[1]: 76 [14]: 181–182

- ^ A popular concept in science fiction, first used in John W. Campbell's Islands of Space (1957), which also introduced the term "space warp".[1]: 77 [15][16]

- ^ Inertialess drive is one of the early terms for fictitious space drives, introduced in E.E. Smith's 1934 Tri-planetary Lensman series.[1]: 75

- ^ Devices that provide steady thrust through a stream of accelerated ions, successfully tested by NASA in the 1990s.[2]: 142

- ^ A scientifically plausible concept of giant scoops that collect interstellar hydrogen to generate fuel during travel. A concept adopted, among others, by Larry Niven in his Known Space series, e.g., World of Ptavvs (1965),[1]: 76

- ^ A term invented by George Griffith in his A Honeymoon in Space (1901).[1]: 69, 108

- ^ An early treatment of this idea is Cordwainer Smith's The Lady Who Sailed the Soul (1960).[1]: 74 This concept was revisited by a number of other writers, such as Arthur C. Clarke in The Wind from the Sun (1972) and Robert L. Forward in Future Magic (1988).[5]: 743

- ^ An anti-gravity engine used in James Blish's Cities in Flight series that began in 1950.[1]: 76–77

- ^ A torchship is a ship powered by a torchdrive, a type of nuclear or fusion drive. Brave New Words cites the first use of the word "torchship" in Robert Heinlein's Sky Lift (1953), and that of "torch drive" in Larry Niven's 1976 essay "Words in SF".[2]: 142, 246

- ^ A drive that uses some form of gravity control — which generally implies anti-gravity as well — to propel the ship. Term used by Poul Anderson in his Star Ship (1950).[2]: 81–82, 142

- ^ "Hyperdrive", "overdrive", and "ultradrive" are all defined in Brave New Words as space drives that propel spaceships faster than the speed of light; while "overdrive" and "ultradrive" have no additional characteristic, "hyperdrive" causes spaceships to "enter hyperspace". Brave New Words cites an unspecified story in the January 1949 Startling Stories as the first occurrence of the term "hyperdrive". "Overdrive" is attributed to Murray Leinster's First Contact (1945), and "ultradrive" to Poul Anderson's Tiger by Tail (1958).[2]: 94, 141, 142, 253

- ^ Drive that teleports ships instantaneously from one point to another.[2]: 142 The concept of "jumps" between stars was popularized by Isaac Asimov's Foundation series, which debuted in 1942.[1]: 75 [2]: 142 The term "jump drive" was used in Harry Harrison's Ethical Engineer (1963).[2]: 104

- ^ Classic, proven slower-than-light drive that generates thrust by ejecting matter in the direction opposite to that of travel — in other words, a rocket. The term was used as early as 1949 in Theodore Sturgeon's Minority Report.[2]: 142, 162

- ^ A fixed teleporter for spaceships. Also known as a "jump gate". The term "star gate" was used in Arthur C. Clarke's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968); "stargate", by Robert Holdstock and Malcolm Edwards in Tour of the Universe (1980), and "jump gate", in the Babylon 5 TV series that debuted in 1993.[2]: 105–106, 142, 217

- ^ A device that distorts the shape of the space-time continuum.[2]: 142 A concept popularized by the Star Trek TV series, but with precedents which often use the term "space warp", such as the John W. Campbell's Islands of Space (1957).[1]: 77 [15] Robert A. Heinlein's Starman Jones had already considered the concepts of "folds" in space in 1953.[5]: 743 Brave New Words gives the earliest example of the term "space-warp drive" in Fredric Brown's Gateway to Darkness (1949), and also cites an unnamed story from Cosmic Stories (May 1941) as using the word "warp" in the context of space travel, though use of this term as a "bend or curvature" in space which facilitates travel can be traced to several works as far back as the mid-1930s, e.g., to Jack Williamson's The Cometeers (1936).[2]: 212, 268

- ^ This theme has occasionally been revisited in modern works, such as Bob Shaw's Land and Overland trilogy that begins with The Ragged Astronauts (1986), set between a pair of planets, Land and Overland, which orbit a common center of gravity, close enough to each other that they share a common atmosphere.[4]

- ^ Verne's idea of using a cannon shot as means of propulsion did not stand the test of time, and the proposed hydraulic shock absorbers and padded walls would not have saved the capsule's crew from death at take-off.[1]: 69

- ^ Tsiolkovsky's Beyond the Planet Earth (1920, but begun in 1896) describes travel to the Moon and the asteroid belt in a rocket spaceship.[1]: 69

- ^ As seen in Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).[3]: 511–512

- ^ The concept was explored as early as 1934 in Laurence Manning's The Living Galaxy, and shortly after, in 1940, in Don Wilcox's The Voyage That Lasted 600 Years (1940). The concept was popularized in Robert A. Heinlein's Universe, later expanded into the novel Orphans of the Sky (1964). Other classics featuring this concept include Brian Aldiss' Non-Stop (1958) and Gene Wolfe's Book of the Long Sun series that began in 1993.[1]: 73 [3]: 485–486, 511–512 [5]: 743

- ^ This concept featured, for example, in A. E. van Vogt's Far Centaurus (1944).[1]: 74

- ^ Bussard ramjets and time dilation feature prominently in Poul Anderson's Tau Zero (1970).[3]: 511–512 [1]: 76 [5]: 743 Time dilation has also been a major plot device in a number of works, for example L. Ron Hubbard's To the Stars (1950), in which the returning astronauts face a society in which centuries have passed.

- ^ Wormhole travel is depicted, for example, in Joe Haldeman's Forever War series that started in 1972.[1]: 77

- ^ Space folding is a term used in, among others, Frank Herbert's Dune (1965).[21]: 214

- ^ The idea appears in Thomas N. Scortia's Sea Change (1956).[1]: 76

- ^ This is the main theme of Frederick Pohl's The Mapmakers (1955).[1]: 75 Consider also the aptly named Lost in Space.[23]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al Ash, Brian (1977). The Visual Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Harmony Books. ISBN 978-0-517-53174-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Prucher, Jeff (2007-05-07). Brave New Words: The Oxford Dictionary of Science Fiction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-988552-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Mann, George (2012-03-01). The Mammoth Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 978-1-78033-704-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "Themes : Space Flight : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". www.sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2021-09-01.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Slusser, George (2005). "Space Travel". In Westfahl, Gary (ed.). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Themes, Works, and Wonders. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32952-4.

- ^ "Authors : Godwin, Francis : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". www.sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2021-09-03.

- ^ "Authors : Cyrano de Bergerac : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". www.sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2021-09-03.

- ^ "Themes : Hard SF : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". www.sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2021-09-03.

- ^ "Media : Star Trek : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". www.sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2021-09-03.

- ^ James, Edward (1999). "Per ardua ad astra: Authorial Choice and the Narrative of Interstellar Travel". In Elsner, Jaś; Rubiés, John (eds.). Voyages and Visions: Towards a Cultural History of Travel. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-020-7.

- ^ Creed, Barbara (2009), Darwin's Screens: Evolutionary Aesthetics, Time and Sexual Display in the Cinema, Academic Monographs, p. 58, ISBN 978-0-522-85258-5

- ^ Frinzi, Joe R. (24 August 2018). Kubrick's Monolith: The Art and Mystery of 2001: A Space Odyssey. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-2867-7.

- ^ "Dark Star". Kitbashed. 9 August 2013. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ George Arfken (1 January 1984). University Physics. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-323-14202-1. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ a b c "Themes : Space Warp : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". www.sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2021-09-04.

- ^ a b "Themes : Hyperspace : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". www.sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2021-09-03.

- ^ Nicholls, Peter; Langford, David; Stableford, Brian M., eds. (1983). "Faster than light and relativity". The Science in Science Fiction. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-53010-9.

- ^ Dwilson, Stephanie Dube (2017-10-09). "'Star Trek: Discovery' New Spore Drive vs. Other Faster-Than-Warp Tech". Heavy.com. Retrieved 2021-09-09.

- ^ "Authors : Tsiolkovsky, Konstantin : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". www.sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2021-09-03.

- ^ Rodriguez Baquero, Oscar Augusto (2017). La presencia humana más allá del sistema solar [Human presence beyond the solar system] (in Spanish). RBA. p. 18-19. ISBN 978-84-473-9090-8.

- ^ a b Grazier, Kevin R. (2007-12-11). The Science of Dune: An Unauthorized Exploration into the Real Science Behind Frank Herbert's Fictional Universe. BenBella Books, Inc. ISBN 978-1-935251-40-8.

- ^ a b "5 Faster-Than-Light Travel Methods and Their Plausibility". The Escapist. 2014-06-18. Retrieved 2021-09-03.

- ^ "Media : Lost in Space : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". www.sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2021-09-08.

Further reading

[edit]- Alcubierre, Miguel (2017-06-20). "Astronomy and space on the big screen: How accurately has cinema portrayed space travel and other astrophysical concepts?". Metode Science Studies Journal (7): 211–219. doi:10.7203/metode.7.8530. hdl:10550/79712. ISSN 2174-9221.

- Clarke, Arthur C. (September 1950). "Space-Travel in Fact and Fiction". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. 9 (5): 213–230.

- Fraknoi, Andrew (January 2024). "Science Fiction Stories with Good Astronomy & Physics: A Topical Index" (PDF). Astronomical Society of the Pacific (7.3 ed.). p. 19. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-02-10. Retrieved 2024-03-23.

- Freedman, Russell (1963). 2000 Years of Space Travel. Holiday House.

- Kanas, Nick (November 2015). "Ad Astra! Interstellar Travel in Science Fiction". Analog. 135 (11): 4–7.

- Ley, Willy (1964). "Writer's Choice". Missiles, Moonprobes, and Megaparsecs. New American Library. pp. 112–125.

- May, Andrew (2018). "Journey into Space". Rockets and Ray Guns: The Sci-Fi Science of the Cold War. Science and Fiction. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 41–79. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-89830-8_2. ISBN 978-3-319-89830-8.

- Mollmann, Steven (2011). "Space Travel in Science Fiction". In Grossman, Leigh (ed.). Sense of Wonder: A Century of Science Fiction. Wildside Press LLC. ISBN 978-1-4344-4035-8.

- Moskowitz, Sam (October 1959). Santesson, Hans Stefan (ed.). "Two Thousand Years of Space Travel". Fantastic Universe. Vol. 11, no. 6. pp. 80–88, 79. ISFDB series #18631.

- Moskowitz, Sam (February 1960). Santesson, Hans Stefan (ed.). "To Mars And Venus in the Gay Nineties". Fantastic Universe. Vol. 12, no. 4. pp. 44–55. ISFDB series #18631.

- Ruehrwein, Donald (May 1, 1979). "A History of Interstellar Space Travel (As Presented in Science Fiction)". Odyssey. 5 (5): 14–17.

- Russo, Arturo (2001). "Dreams of Space Flight". In Bleeker, Johan A.M.; Geiss, Johannes; Huber, Martin C.E. (eds.). The Century of Space Science. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 26–29. ISBN 978-94-010-0320-9.

- Weitekamp, Margaret A. (2019). ""Ahead, Warp Factor Three, Mr. Sulu": Imagining Interstellar Faster-Than-Light Travel in Space Science Fiction". The Journal of Popular Culture. 52 (5): 1036–1057. doi:10.1111/jpcu.12844. ISSN 1540-5931. S2CID 211643287.

- Westfahl, Gary (2022). "Spaceships—Rockets to Ride: The Spaceships of Science Fiction". The Stuff of Science Fiction: Hardware, Settings, Characters. McFarland. pp. 41–50. ISBN 978-1-4766-8659-2.

External links

[edit]- "The Science Fiction and Fantasy Research Database. Search Records by Subject: SPACE TRAVEL". sffrd.library.tamu.edu. Retrieved 2021-12-21.