Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Glossary of anarchism

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

The following is a list of terms specific to anarchists. Anarchism is a political and social movement which advocates voluntary association in opposition to authoritarianism and hierarchy.

A

[edit]- Acracy

- The negation of rule or "government by none". While "anarchy" refers to the absence of a hierarchical society-organizing power principle, "acracy" refers to the absence of coercion; the condition of acracy is one of voluntary order. Derived from the Greek α- [no] and κρατία [system of government].

- Adhocracy

- A form of organic organization according to which different parts of an organization are temporarily assembled to meet the requirements of that particular point in time.[1]

- Affinity group

- A small non-hierarchical collective of individuals who collaborate on direct action via consensus decision-making.[2]

- Anarch

- Coined by Ernst Jünger, this refers to the ruler (i.e. individual) in a state of anarchy analogous to the monarch in a state of monarchy, a conception influenced by Max Stirner's notion of the sovereign individual.[3]

- Anarchism without adjectives

- A form of anarchism which does not declare affiliation with any specific subtype of anarchism (as may be suffixed to anarcho- or anarcha-), instead positioning itself as pluralistic, tolerant of all anarchist schools of thought.[4]

- Anarchy

- Derived from the Ancient Greek ἀν (without) + ἄρχειν (to rule) "without archons," "without rulers".[5]

- Anomie

- Social disorder and civil war in an absence of government, used to separate anarchy as in social order and absence of government.

- Ansoc

- Clipping of anarcho-socialism and/or anarcho-socialist used in informal discourse, particularly in blogs or other internet forums.

- Anti-systemic library

- A library which is not organised hierarchically and that has no catalogue. The concept is influenced by the ideas of the Situationists.

- Autonomism

- A set of radical left-wing political movements in Western Europe which emerged in the late 20th century.

- Archon

- A Greek word meaning "ruler"; the absence of archons and archy (rule) defines a state of anarchy. Derived from the Ancient Greek άρχων, pl. άρχοντες.

B

[edit]- Biennio rosso

- The "two red years" of political agitation, strikes and land occupation by Italian workers in 1919 and 1920.[6]

- Black anarchism

- A political philosophy primarily of African Americans, opposed to what it sees as the oppression of people of colour by the white ruling class through the power of the state.[7]

- Black bloc

- An affinity group, or cluster of affinity groups that assembles during protests, demonstrations, or other forms of direct action. Black blocs are noted for the distinctive all-black clothing worn by members to conceal their identity and for their intentional defiance of state property law.[8][9]

- Bourse du Travail

- A distinctively French form of working class organization of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, bourses du travail promoted mutual aid, education, and self-organization amongst their members.[10]

C

[edit]- Companion

- A term used to speak about a fellow anarchist, akin to 'comrade' in communism and a former organizational structure of anarchism.[11][12][13]

- Consensus decision-making

- A participatory decision making process for collectives that seeks the resolution or mitigation of minority objections (according to the principle of inclusivity) as well as the agreement of the majority of participants.[14][15][16]

- Cost the limit of price

- A maxim coined by individualist anarchist Josiah Warren (1798–1874) to express a normative conception of the labor theory of value—that is, that the price of a good or service should never exceed its cost.[17]

- Counter-economics

- Abbreviation of "counter-establishment economics", a concept in agorist theory of the use and advocacy of black and grey markets and the underground economy to erode the moral authority of and the perceived necessity for the state.

D

[edit]…When a revolutionary situation develops, counter-institutions have the potential of functioning as a real alternative to the existing structure and reliance on them becomes as normal as reliance on the old authoritarian institutions. This is when counter-institutions constitute dual power.

Dual power is a state of affairs in which people have created institutions that fulfill all the useful functions formerly provided by the state. The creation of a general state of dual power is a necessary requirement for a successful revolution…

- Dispute resolution organization (DRO)

- A private (or possibly cooperative) organization specialized in resolving disputes that would arise in an anarchical society (similar to a PDA).[19]

- Diversity of tactics

- A united front of solidarity between participants who disagree on specific choice of tactics. For instance, during a protest action, demonstrators can create zones with varying degrees of tactical risk, rather than imposing a single code.[20]

- Dual power

- The concept of revolution through the creation of "counter-institutions" in place of and in opposition to state power.[18] Used in anarcho-communist discourse, it is distinct from the earlier use of the phrase by non-anarchist communists such as Vladimir Lenin.

- Dumpster diving

- Physically searching through the discarded belongings in a dumpster or other trash receptacle, with the intention of salvaging useful material such as food or information.[21]

E

[edit]- Epistemological anarchism

- A theory in the philosophy of science advanced by Paul Feyerabend which holds that there are no useful and exception-free rules governing the progress of science, and that the pragmatic approach is a Dadaistic "anything goes" attitude of methodological pluralism.[22]

F

[edit]- Food rescue

- The practice of retrieving edible food that would otherwise go to waste and distributing it to those in need.[23]

- Free school

- A decentralized network in which skills, information and knowledge are shared with neither the social hierarchy nor the institutional environment of formal schooling.

- Free soviets

- Following the Russian Revolution, the concept of workers' councils (soviets) that were self-governing and free from party control.[24]

- Freeganism

- An anti-consumerist lifestyle according to which participants attempt to restrict their consumption of natural resources and participation in the conventional economy to using salvaged and discarded goods.[25]

- Freigeld

- A monetary system in the Freiwirtschaft theory, according to which units of currency retain their value or lose it at a certain rate, making inflation and profiting from interest impossible. Freigeld is a German phrase with the literal meaning "free money".[26]

G

[edit]- Give-away shop

- Second-hand stores where all goods are free. An example of a gift economy.[27]

- Guerrilla gardening

- Nonviolent direct action whereby disused plots are converted to gardens without seeking the permission of the putative property owners.[28] Related: squatting.

H

[edit]- Haymarket Martyrs

- The seven anarchists tried and executed for the murder of a Chicago policeman during the Haymarket affair.[29]

- Haymarket Tragedy

- Hierarchy

- See social hierarchy

- Horizontalidad (also Horizontalism)

- A form of non-hierarchical social organization which utilises direct democracy and consensus decision-making.[30]

I

[edit]

- Illegalism

- A doctrine which rejects all moral obligations and governmental law in favour of the satisfaction of one's own desires.[31] Pioneered by the Bonnot Gang in France and heavily influenced by the individualist anarchist philosophy of Max Stirner.[31]

- Immediatism

- A philosophy which demands the embracing of immediate social interactions with people as a means of countering the antisocial consequences of consumerist capitalism.[32]

- Individual reclamation (reprise individuelle)

- The idea that, given that capitalists steal from individuals and the people, it would be legitimate to steal from them in return. This was theorized by Clément Duval and Vittorio Pini and serves as the ideological foundation for the illegalist tendency[33].

- Infoshop

- A space (often a social center) that serves as a node for anarchists involved with radical movements and countercultures for trading publications (typically books, zines, stickers and posters), meeting and networking with similar individuals and groups.[34] The primary directive of an infoshop is the dissemination of information.[35] Related: zine library.

- Invisible dictatorship

- A vanguardist organisation of revolutionaries first proposed by Mikhail Bakunin.[36]

J

[edit]- Jurisdictional arbitrage

- Exploitation of differences in national laws and regulations[37] to maximise liberty. Related: dynamic geography, panarchism.

K

[edit]- Kabouters

- Dutch anarchists influenced by Peter Kropotkin who sought to promote awareness of alternatives to authoritarian and capitalist solutions to social problems in 1960s Amsterdam.[38]

L

[edit]- Land and liberty

- A slogan expressing the desire of freedom from landowners originally used by the revolutionary leaders of the Mexican Revolution. Spanish: Tierra y Libertad, Russian: Земля и Воля Zemlya i Volya.

- Law of equal liberty

- A doctrine asserting that each individual has the right to assert their fullest liberty to act so long as it does not extend them greater liberty than any other individual. Named by Herbert Spencer.

- Lifestylism

- Anarchists who prioritize cultural and identity protest over class struggle politics. Associated with Murray Bookchin's 1995 essay in pejorative reference to anarcho-primitivists, poststructural anarchists, and individualists/egoists.[39]

- Lois scélérates

- A pejorative term for a set of French laws passed during 1893–1894 restricting the freedom of the anarchist press in the aftermath of an outbreak of propaganda of the deed.

M

[edit]

- Makhnovshchina

- Mass movement to establish anarchist-communism in Ukraine, led by the Ukrainian anarchist revolutionary Nestor Makhno (1888–1934) and his followers in the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine.

- Modern School

- American schools formed in the early 20th century based on the ideas of educator and anarchist Francesc Ferrer i Guàrdia and modelled after his Escuela Moderna.[40]

- Mutual aid

- The voluntary reciprocal exchange of resources and services for mutual benefit. Related: gift economy, voluntarism.

N

[edit]- Netwar

- Low-intensity social conflict employing a network structure for organisational control and communication.[41] Related: Security culture.

P

[edit]- Panarchy (political philosophy)

- Participatory politics

- Polycentric law

- Popular assembly

- Post-left

- Prefigurative politics

- Primitivist

- Used interchangeably with anarcho-primitivist.

- Propaganda of the deed

- Property is theft!

- Provo

- Punk house

R

[edit]- Radical cheerleading

- Really Really Free Market

- A free market based on the principle of gift economics whereby participants bring gifts and resources to share with one another, without money being exchanged.[42] Related: participatory economics, voluntary association.

- Refusal of work

- Responsible autonomy

- Revolutionary spontaneity

- Rewilding

- Reprise individuelle

S

[edit]Samizdat—the production of literature banned by the former communist governments of eastern Europe; the term is a play on the term for the Soviet state press, and translates to "self-publishing." Throughout the greater part of the twentieth century, the best literature, philosophy, and history in the Soviet Union and its satellite states was copied by photo-reproduction and distributed through underground channels—just as it is here in the United States today.

- Seasteading

- The creation of permanent dwellings on the ocean, analogous to homesteading on land. A seastead is a structure meant for permanent occupation on the ocean.[44]

- Security culture

- Secrecy practiced by an affinity group which engages in illegal activities, and its precautions to avoid surveillance or infiltration by law enforcement.[45] Related: direct action, netwar

- Somatherapy

- Spokescouncil

- Spontaneous order

- Street reclamation

- Swaraj

T

[edit]- TANSTAAFL

- Acronym coined by libertarian science fiction writer Robert A. Heinlein in The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress for "There Ain't No Such Thing As A Free Lunch". Used to express scepticism towards socialist economics.[46]

- Tragic Week

- The name given to a series of violent confrontations between the Spanish army and the anarchist-backed working classes in Catalunyan cities from July 25-August 2, 1909.[47]

- Trial of the thirty

- A show trial in 1894 in Paris aimed at legitimizing the lois scélérates passed in 1893–1894 against the French anarchist movement and at restricting press freedom by proving the existence of an effective association between anarchists.[48] French: Procès des trente

V

[edit]- Veganarchism

- The political philosophy of veganism (more specifically animal liberation) and anarchism, creating a combined praxis as a means for social revolution.

- Voluntarism

- The use of or reliance on voluntary action to maintain an institution, carry out a policy, or achieve an end.[49]

- Voluntaryism

- A political philosophy which advocates voluntary association as the foundation of society, and opposes coercion and aggression.

W

[edit]

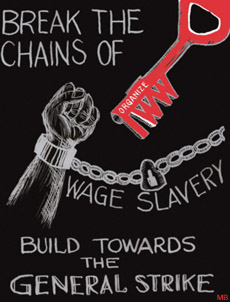

- Wage slavery

- A term which asserts a similarity between slavery—the ownership and control of one person by another—and wage labour.[50]

- Workers' self-management

- A form of workplace decision-making in which the workers rather than professional managers decide on issues related to the operation of the business.[51]

Z

[edit]- Zenarchy

- Compound of zen and "archy". The social order which arises from meditation. As a doctrine, zenarchism is the belief that "universal enlightenment" is a prerequisite to the abolition of the state.[52]

- Zine

- A low-circulation, non-commercial periodical of original or appropriated texts and images. Usually reproduced via photocopier on a variety of colored paper stock.

- Zine library

- A repository of zines and other associated artifacts, such as small press books. Zine libraries are typically run on a minimal budget, and have a close association with infoshops and other forms of DIY culture and independent media.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Alvesson, Mats (1995). Management of Knowledge-Intensive Companies. Walter De Gruyter Inc. p. 93. ISBN 978-3110128659.

- ^ Recipes for Disaster, p.28-31

- ^ Warrior, Waldgänger, Anarch: An essay on Ernst Jünger's concept of the sovereign individual Archived 2008-06-09 at the Wayback Machine by Abdalbarr Braun. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ Esenwein, George Richard "Anarchist Ideology and the Working Class Movement in Spain, 1868–1898" [p. 135]

- ^ Anarchy Merriam-Webster's Online dictionary

- ^ Macdonald, Hamish (1998). Mussolini and Italian Fascism. Trans-Atlantic Publications. p. 17. ISBN 978-0748733866.

- ^ Daquan, Bridger (2007). Delusion Addiction. Trafford Publishing. p. 118. ISBN 978-1425117696.

- ^ "Blocs, Black and Otherwise". Crimethinc.com. CrimethInc. 20 November 2003. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ^ ACME Collective, A communique from one section of the black bloc of N30 in Seattle.

- ^ Ogg, Frederic Austin (1917). Economic development of modern Europe. New York: The Macmillan company. p. 464. OCLC 603770.

- ^ Testard, François (2024). "Le non-recours intentionnel aux minima sociaux : sociologie d'expériences radicales". Transversales (in French) (24): 8.

- ^ Bouhey 2008, p. 68-81.

- ^ Bouhey 2008, p. 93-100.

- ^ Cohn, Jesse (2006). Anarchism and the Crisis of Representation. Selinsgrove Pa.: Susquehanna University Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-1575911052.

- ^ Graeber, David (2007). "The Twilight of Vanguardism". In Macphee, Josh (ed.). Realizing the Impossible. Stirling: AK Press. ISBN 978-1904859321.

- ^ Antliff, Allan (2004). Only a Beginning. Arsenal Pulp Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-1551521671.

- ^ Tucker, Benjamin R., "State Socialism and Anarchism Archived 1999-01-17 at the Wayback Machine", Individual Liberty, Vanguard Press, New York, 1926

- ^ a b Jarach, Lawrence (Winter 2002–2003). "Anarcho-Communists, Platformism, and Dual Power: Innovation or Travesty?". Anarchy: A Journal of Desire Armed (54). Retrieved 2008-08-02.

- ^ Molyneux, Stefan (October 24, 2005). "The Stateless Society". LewRockwell.com. Retrieved 2008-08-02.

- ^ Starr, Amory (May 2006). "' (Excepting Barricades Erected to Prevent Us from Peacefully Assembling)': So-called 'Violence' in the Global North Alterglobalization Movement". Social Movement Studies. 5 (1): 61–81. doi:10.1080/14742830600621233. ISSN 1474-2837. S2CID 146798880.

- ^ Dubrawsky, Ido (2007). How to Cheat at Securing Your Network. Syngress. p. 50. ISBN 978-1597492317.

- ^ Feyerabend, Paul (1993). Against Method. London: Verso. ISBN 9780860916468.

- ^ Levinson, David, ed. (2004). Encyclopedia of Homelessness. Thousand Oaks. p. 286. ISBN 978-0761927518.

- ^ Graziosi, Andrea (1996). The Great Soviet Peasant War: Bolsheviks and Peasants, 1917–1933. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-916458-83-6. OCLC 40684852.

- ^ Kurutz, Steven (June 21, 2007). "Not Buying It". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

the small but growing subculture of anticonsumerists who call themselves freegans — the term derives from vegans, the vegetarians who forsake all animal products, as many freegans also do

- ^ Zweig, Ferdynand (1934). The Economics of Consumers' Credit. London: P. S. King & Son. p. 7. OCLC 5358381.

- ^ Logs : micro-fondements d'émancipation sociale et artistique. Maisons-Alfort, France : Ére, [2005- ]. ISBN 2-915453-04-7 OCLC 60370621 p.20

- ^ Notes from Nowhere (2003). We Are Everywhere. London: Verso. p. 150. ISBN 978-1859844472.

- ^ Foner, Philip S., ed. (1969). The Autobiographies of the Haymarket Martyrs. New York: Pathfinder Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0873488792.

- ^ Sitrin, Marina (2006). Horizontalism. Stirling: AK Press. ISBN 978-1904859581.

- ^ a b Parry, Richard (1987). "From illegality to illegalism". The Bonnot Gang. London: Rebel Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0946061044.

- ^ Bey, Hakim (1994). Immediatism. AK Press. ISBN 978-1873176429.

- ^ Bouhey 2008, p. 145-155.

- ^ Filippo, Roy (2003). A New World in Our Hearts. Stirling: AK Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-1902593616.

- ^ Curran, James (2003). Contesting Media Power. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 57. ISBN 978-0742523852.

- ^ Clark, John P. (2004). Anarchy, Geography, Modernity. Lexington: Lexington Books. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-0739108055.

- ^ Williams, P. (2001). "Transnational Criminal Networks" (PDF). Networks and Netwars: The Future of Terror, Crime, and Militancy. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- ^ Woodcock, George (2004). Anarchism: a History of Libertarian Ideas and Movements. Peterborough: Broadview Press. p. 371. ISBN 978-1551116297.

- ^ Morris, Brian (2014). "The Political Legacy of Murray Bookchin". Anthropology, Ecology, and Anarchism: A Brian Morris Reader. PM Press. pp. 169–170. ISBN 978-1-60486-986-6.

- ^ Brennan, Elizabeth (1998). Who's Who of Pulitzer Prize Winners. Phoenix: Oryx Press. p. 257. ISBN 978-1573561112.

- ^ Arquilla, J.; Ronfeldt, D. (1996). The Advent of Netwar. RAND Corporation. ISBN 978-0833024145.

- ^ Recipes for Disaster, p. 241

- ^ "Glossary of Terms, part IV". Rolling Thunder (4): 6–8. Spring 2007.

- ^ Friedman, Patri (14 April 2008). "A Brief Introduction to the Seasteading Institute". Seasteading.org. Seasteading Institute. Retrieved 2008-06-23.

- ^ Starr, Amory; Fernandez, Luis A.; Scholl, Christian (2011). Shutting Down the Streets: Political Violence and Social Control in the Global Era. NYU Press. pp. 114, 142. ISBN 9780814741009. Retrieved 4 May 2019.; Anonymous (2005). Recipes for Disaster. Crimethinc.Workers Collective. p. 461. ISBN 978-0970910141.

- ^ Stover, Leon (1987). Robert A. Heinlein. Boston: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0805775099.

- ^ Bookchin, Murray (1997). The Spanish Anarchists. Stirling: AK Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-1873176047.

- ^ Jean Maitron, Le mouvement anarchiste en France, Tel Gallimard (first ed. François Maspero, 1975), tome I, chapter VI, "Le Procès des Trente. Fin d'une époque", pp.251-261

- ^ "Voluntarism". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company. Archived from the original on 2009-02-08. Retrieved 2008-09-18.

- ^ Malachowski, Alan (2001). Business Ethics. New York: Routledge. pp. 98–99. ISBN 978-0415184625.

- ^ Taras, Ray (1984). Ideology in a Socialist State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 89–92. ISBN 978-0521262712.

- ^ Gorightly, Adam (2003). The Prankster and the Conspiracy. Paraview Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-1931044660.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bouhey, Vivien (2008), Les Anarchistes contre la République [The Anarchists against the Republic], Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes (PUR)

Glossary of anarchism

View on GrokipediaAnarchism fundamentally opposes coercive authority, particularly the state and involuntary hierarchies, proposing instead societies organized through voluntary associations, mutual aid, and self-management.[2][3] Central terms include anarchy as the absence of government enabling free individual action; coercion as any threat-based domination to be eradicated; direct action involving personal or collective initiatives bypassing official channels; and mutual aid as reciprocal cooperation fostering social solidarity without compulsion.[2][4]

The lexicon reflects anarchism's diversity, spanning individualist strands prioritizing personal sovereignty against collectivist forms emphasizing communal equality and anti-capitalism, with debates over tactics ranging from pacifist education to revolutionary confrontation.[2] Empirical assessments of anarchist experiments, such as during the Spanish Civil War, reveal initial decentralized production gains but ultimate collapses amid external aggression and internal coordination failures, underscoring causal challenges in sustaining non-hierarchical orders absent unified defense mechanisms.[5] Primary anarchist texts provide the most direct terminological authority, though their partisan advocacy warrants cross-verification against historical outcomes rather than uncritical acceptance.[2]

A

Terms beginning with A

Affinity group: A small, autonomous collective of 5 to 20 individuals who collaborate on direct actions or projects based on pre-existing trust and shared affinity, originating in early 20th-century anarchist and labor movements, particularly during the Spanish Civil War where they formed the structure of groups like the FAI.[6][7] Agorism: A libertarian anarchist strategy developed by Samuel Edward Konkin III in the 1970s, advocating counter-economics—peaceful, voluntary black and gray market activities—to undermine the state and establish a free society through agoras (open markets) without political engagement.[8][9] Anarchism: A political philosophy originating in the 19th century with Pierre-Joseph Proudhon's 1840 declaration in What is Property? rejecting coercive authority, particularly the state, in favor of voluntary associations and mutual aid; Mikhail Bakunin expanded it to view the state as the primary source of hierarchy and exploitation, emphasizing collective action against all forms of imposed power.[10][11] Anarcho-capitalism: A variant of anarchism formulated by Murray Rothbard in works from the 1950s onward, positing a stateless society organized through private property, free markets, and contractual defense agencies, where all services including law and security are provided competitively without monopoly.[12][13] Anarcho-communism: An anarchist tradition advanced by Peter Kropotkin in the late 19th century, advocating the abolition of private property, wage labor, and the state in favor of communal ownership of means of production and distribution according to need, achieved through mutual aid and federated communes without authoritarian structures.[14][15] Anarcho-syndicalism: A revolutionary unionism integrating anarchist principles with syndicalist tactics, emerging from the First International in the 1860s and peaking in organizations like the CNT during the 1936 Spanish Revolution, where workers' syndicates aim to expropriate industry and dismantle the state through direct action and federalist coordination.[16][17]B

Terms beginning with B

Black blocA black bloc is a protest tactic employed by anarchist and anti-authoritarian groups, involving participants dressing in black clothing, masks, and helmets to conceal individual identities and facilitate collective direct action.[18] This approach originated in Europe during the 1980s autonomous movements and gained prominence at events like the 1999 WTO protests in Seattle, where it enabled property damage against corporate targets while protecting participants from surveillance and arrest.[19] Anarchists view the tactic as a form of "propaganda of the deed," projecting unified resistance against state and capital, though it has drawn criticism from pacifist anarchists for escalating confrontations and alienating potential allies.[20] Black flag

The black flag serves as a primary symbol of anarchism, representing the negation of all state authority, nationalism, and hierarchical flags, first prominently used by anarchists in the late 19th century.[21] Popularized by figures like Louise Michel during the 1880s in France, it embodies refusal of compromise with power structures and solidarity in revolt, often flown alongside the red-and-black flag in anarcho-communist contexts.[22] In practice, it has appeared in strikes, insurrections, and protests, such as the Haymarket affair in 1886, signaling total opposition to wage labor and governance.[23] Bolshevism (anarchist critique)

Anarchists critique Bolshevism as a form of state socialism that substitutes vanguard party rule for worker self-management, leading to authoritarian consolidation rather than abolition of hierarchy.[24] Mikhail Bakunin warned in 1873 that Marxist statism would empower a new elite, predicting the Bolshevik Revolution's outcome where the party bureaucracy oppressed the proletariat, as evidenced by the suppression of soviets and Kronstadt rebellion in 1921.[25] This opposition underscores anarchism's rejection of transitional states, favoring immediate federalist organization over centralized dictatorship.[11]

C

Terms beginning with C

Collectivist anarchismCollectivist anarchism, also termed anarcho-collectivism, emerged in the mid-19th century as a branch of social anarchism emphasizing the abolition of private property in the means of production and their transfer to workers' associations organized on federalist principles.[26] Distribution of goods would occur via labor vouchers redeemable for products based on hours worked, distinguishing it from later anarchist communism's "to each according to need" principle.[27] Mikhail Bakunin, a key proponent, advocated this during the First International (1864–1876), influencing groups like the Jura Federation in Switzerland, where collectives managed production democratically without wage labor or state oversight.[26] Spanish anarchists during the 1936–1939 Revolution applied similar models in Catalonia and Aragon, collectivizing over 8 million hectares of land and 2,000 enterprises under worker control, though challenged by civil war dynamics.[28] Critics within anarchism, including communists like Peter Kropotkin, argued labor-based remuneration perpetuated inequality by tying value to output rather than abundance.[28] Communalism

Communalism, developed by Murray Bookchin in the late 20th century, posits a confederal network of directly democratic municipal assemblies as the basis for a stateless society, integrating ecological principles with libertarian socialism.[29] Bookchin, initially aligned with anarchism, formalized it in works like The Ecology of Freedom (1982), emphasizing "libertarian municipalism" where communities recall delegates and prioritize local self-governance over abstract individual liberty.[30] It rejects both state socialism and market capitalism, advocating rotation of roles, majority rule with protections for minorities, and inter-municipal confederations for coordination, as trialed in Rojava's democratic confederalism since 2012.[31] Bookchin distanced communalism from anarchism by 1995, critiquing the latter's perceived anti-organizational "lifestylism" and insufficient emphasis on institutional ecology, though it retains anarchist roots in anti-statism and federalism.[32] Empirical applications, such as Vermont's town meetings, demonstrate scalable direct democracy but face scalability critiques in urban contexts exceeding 30,000 residents.[33] Communist anarchism

Communist anarchism, or anarcho-communism, advocates the immediate abolition of money, wages, and private property, replacing them with communal production and free distribution "from each according to ability, to each according to need."[28] Originating in the 1870s–1880s, it built on collectivist foundations but rejected labor vouchers; Errico Malatesta's 1883 Geneva Congress declaration and Peter Kropotkin's The Conquest of Bread (1892) argued post-revolutionary abundance from automation and cooperation would render remuneration obsolete.[34] It gained traction in the Second International debates and influenced the Makhnovshchina in Ukraine (1918–1921), where Nestor Makhno's forces established soviets distributing grain and tools without currency amid Bolshevik opposition.[28] Unlike Marxist communism's transitional state, it insists on immediate statelessness via insurrectionary federations, as seen in the 1920 Kronstadt uprising's demands for soviet power without Bolsheviks.[35] Proponents cite historical communes like the Paris sections of 1793, where sans-culottes practiced egalitarian rationing during scarcity, validating feasibility under duress.[28] Consensus decision-making

Consensus decision-making in anarchism seeks unanimous agreement or active consent from all participants, avoiding majority votes to prevent minority coercion and foster collective ownership of outcomes.[36] Rooted in Quaker practices but adapted by 1960s counterculture and anarchist affinity groups, it involves proposal testing, amendments via "stacking," and options like "stand aside" for non-binding dissent, as outlined in anarchist handbooks since the 1970s.[37] Applied in squats and cooperatives, such as the Clandestine Insurgent Rebel Clown Army's actions, it prioritizes horizontalism but risks paralysis; Occupy Wall Street's 2011 general assemblies stalled on logistics due to blocks, prompting critiques of it enabling de facto vetoes by disruptors.[38] Empirical studies of affinity groups show higher cohesion when groups limit to 5–15 members, with fall-back to modified consensus (e.g., 80% supermajority) in larger bodies like the Zapatista caracoles.[39] Anarchist theorists like Gelderloos argue it counters hierarchy only if paired with rotation and skill-sharing, lest it devolve into informal leadership.[37] Counter-economics

Counter-economics, central to agorist theory, denotes voluntary, non-violent market activities evading state regulation—encompassing black, gray, and white markets—to erode governmental revenue and build parallel institutions toward anarchy.[8] Coined by Samuel Edward Konkin III in New Libertarian Manifesto (1980), it contrasts with political activism, positing that taxation funds 40–50% of state budgets (per U.S. IRS data, 1970s), so withdrawing economic participation via barter, crypto, or untaxed labor accelerates collapse.[40] Agorists, a market anarchist strain, applied it in 1980s networks like the Agorist Institute, promoting entrepreneurship in prohibited goods (e.g., unlicensed services) to foster class conflict between "statists" and "agorists."[41] Historical parallels include 19th-century mutual aid societies evading usury laws, though critics like left-anarchists decry commodification risks perpetuating exploitation absent collective controls.[42] Konkin projected a "phase three" revolution where counter-economic networks, growing at 10–20% annually via compounding evasion, render states obsolete by 2050, based on exponential adoption models.[8]

D

Terms beginning with D

Decentralization denotes the principle of distributing decision-making and organizational functions away from centralized hierarchies toward federated, local, or voluntary networks in anarchist theory. Anarchists contend that centralization inherently fosters coercion and inefficiency, as evidenced by historical state failures in resource allocation during crises, such as the Soviet Union's famines in the 1930s despite centralized planning.[4] This approach aligns with empirical observations of resilient small-scale economies, like mutual aid networks during the 2010 Haitian earthquake, where decentralized coordination outperformed top-down aid.[43] Direct action constitutes a core tactic in anarchism, involving immediate, self-organized efforts by individuals or groups to achieve objectives without relying on intermediaries like governments or representatives. Originating in labor struggles, such as the French syndicalist movements of the early 1900s led by figures like Émile Pouget, it emphasizes personal agency over petitioning authorities, as Pouget argued in 1910 that workers must seize power directly rather than delegate it.[44] Anarchists distinguish it from indirect methods like voting, citing data from strikes where direct interventions, such as factory occupations during the 1936 Spanish Revolution, yielded tangible gains in wages and conditions before state suppression.[45] Critics within broader leftist traditions note its risks of isolation, but proponents counter with evidence of sustained community resilience, as in the Zapatista autonomy projects since 1994.[46] Dual power describes a revolutionary strategy where alternative, non-state institutions parallel and challenge existing authority structures, a concept adapted by some anarchists from Bolshevik theorist Vladimir Lenin's 1917 analysis of the Russian Soviets. In anarchist usage, it involves building counter-institutions like cooperatives or assemblies to erode state legitimacy, as practiced in the Makhnovist movement in Ukraine from 1918 to 1921, where peasant councils operated alongside but against Bolshevik control.[43] However, purist anarchists reject it as potentially statist, arguing it risks legitimizing hierarchy through temporary duality, with historical precedents like the Paris Commune of 1871 showing how such setups can collapse into vanguardism absent total abolition. Empirical assessments, such as Rojava's democratic confederalism since 2012, illustrate mixed outcomes: initial gains in gender equality and local governance but ongoing conflicts with centralizing forces.[47]E

Terms beginning with E

EgoismEgoism, as a key concept in individualist anarchism, asserts that individuals should act solely in accordance with their own self-interest, rejecting external moral, religious, or societal obligations as spooks or fixed ideas that subordinate the unique self.[48] Originating with Max Stirner's 1844 publication Der Einzige und sein Eigentum (The Ego and Its Own), it posits the egoist as the sovereign actor who forms voluntary associations only when beneficial, influencing thinkers like Benjamin Tucker who integrated it into critiques of state-enforced privilege and capitalist monopoly. Unlike collectivist anarchism, egoism prioritizes conscious self-ownership over altruism or communal duty, viewing cooperation as unions of egoists united by mutual advantage rather than ethical imperatives.[49] This stance critiques both statism and capitalism as mechanisms that alienate individuals from their own power, advocating insurrectionary rejection of all authority.[50] Exploitation

Exploitation in anarchist thought describes the process whereby capitalists or property owners appropriate the surplus value produced by workers, paying wages below the full worth of labor output and thereby perpetuating economic hierarchy and coercion.[51] Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, in works like What is Property? (1840), analyzed it as arising from unequal exchange and private control of productive resources, enabling owners to dictate terms and extract unearned profit without worker consent.[52] Anarchists distinguish this from voluntary exchange by emphasizing inherent power imbalances under capitalism, where lack of access to means of production forces wage labor; remedies include worker expropriation of capital and mutualist banking to equalize bargaining.[53] Unlike Marxist solutions relying on state seizure, anarchists advocate direct action, syndicates, and abolition of wage systems to eliminate exploitation at its root through decentralized, non-hierarchical production.[54]

F

Terms beginning with F

Federalism denotes, within anarchist theory, a bottom-up organizational principle wherein autonomous groups and individuals voluntarily coordinate through federations lacking centralized authority or coercive power. This contrasts with state federalism, which imposes top-down structures; anarchist federalism emphasizes revocable delegates and consensus-based decision-making to ensure no hierarchy emerges. Pioneered by thinkers like Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in the 19th century, it structures society via nested voluntary associations, from local communes to broader networks, prioritizing direct democracy and mutual agreements over representation. [55] [56] Free association refers to voluntary, non-coercive relationships among individuals or groups in anarchist society, absent state enforcement, private property in means of production, or class divisions. It forms the basis for economic and social organization, where workers and communities self-manage production and distribution through mutual agreements, rejecting imposed contracts or hierarchies. This principle, articulated in mutualist and collectivist anarchism, enables fluid alliances for collective needs while preserving individual autonomy and exit rights. [57] [58] Free love advocates the rejection of state-sanctioned marriage and monogamous norms as tools of patriarchal and coercive control, promoting consensual relationships unbound by legal or religious institutions. Anarchists like Emma Goldman in the early 20th century championed it as essential to personal liberty, arguing that marriage perpetuates property rights over bodies and labor, particularly women's. It aligns with broader anarchist critiques of authority in intimate spheres, favoring mutual respect and opposition to prostitution as wage slavery's extension. [59] [60]G

Terms beginning with G

General strike In anarchist theory, particularly anarcho-syndicalism, the general strike refers to a coordinated work stoppage across industries aimed at seizing the means of production and dismantling capitalist and state structures, rather than merely pressuring for reforms.[61] Anarchists view it as an evolutionary process where workers progressively assume control through direct action, eschewing electoral or vanguardist methods, as evidenced in historical precedents like the federalist tendencies during the First International.[61] This contrasts with reformist interpretations that limit strikes to wage negotiations, emphasizing instead its role in fostering self-organization and revolutionary expropriation.[61] Green anarchism Green anarchism, also termed eco-anarchism, integrates anarchist opposition to hierarchy with ecological critique, advocating the abolition of industrial civilization to restore symbiotic relations with non-human life and ecosystems.[62] It rejects anthropocentrism, industrial technology, and domestication as root causes of environmental degradation, promoting instead bioregional autonomy and primitive skills for sustainable existence without coercive institutions.[62] Proponents argue that all forms of domination—social, economic, and ecological—stem from the same hierarchical impulses, necessitating a holistic dismantling rather than partial reforms like green capitalism.[62] This strand overlaps with anarcho-primitivism but extends to broader anti-civilization perspectives, critiquing science and progress as tools of control.[62]H

Terms beginning with H

Heteronomy Heteronomy denotes determination of one's actions by external authorities or laws imposed from outside, contrasting with autonomy where individuals self-govern through voluntary cooperation. In anarchist thought, heteronomy manifests in state-imposed rules and hierarchical structures that compel obedience, undermining personal and collective self-determination; anarchists advocate dismantling such systems to foster autonomous associations based on mutual aid and free agreement.[63] This opposition stems from classical anarchist critiques, such as Pierre-Joseph Proudhon's emphasis on justice as reciprocal liberty without external coercion, viewing heteronomous governance as inherently exploitative. Hierarchy Hierarchy in anarchism refers to layered structures of authority where power concentrates unequally, enabling domination and coercion, which anarchists identify as the root of social ills like exploitation and inequality. Anarchists argue hierarchies arise from institutional monopolies on violence, such as the state, and propose their abolition through decentralized, voluntary networks to achieve egalitarian organization.[64] This stance traces to thinkers like Mikhail Bakunin, who in 1873 warned that hierarchical socialism replicates state power under proletarian guise, perpetuating vanguard rule over the masses.[65] Empirical examples include anarchist critiques of Bolshevik centralism post-1917, where imposed hierarchies led to authoritarianism despite revolutionary aims, contrasting with horizontal alternatives in movements like the Spanish CNT during the 1936-1939 Civil War, which managed collectives without top-down command. Horizontalism Horizontalism describes non-hierarchical forms of organization emphasizing equality, direct participation, and consensus decision-making, rejecting vertical authority in favor of networked, peer-based coordination. Emerging prominently in late 20th-century movements like the Zapatista uprising in Chiapas, Mexico, starting January 1, 1994, it prioritizes grassroots autonomy over representative structures, influencing global protests such as Occupy Wall Street in 2011.[64] Anarchists view horizontalism as practically realizing anti-authoritarian principles, as seen in affinity groups during the 1999 Seattle WTO protests, where decentralized actions disrupted trade talks without centralized leadership.[66] Critics from statist left traditions, including some Marxists, contend it hampers scalability against entrenched power, yet proponents cite historical successes like the Makhnovshchina in Ukraine (1918-1921), where horizontal peasant armies resisted both White and Red forces through federated councils.[67]I

Terms beginning with I

Illegalism is a tendency within individualist anarchism that justifies acts of theft, fraud, and other illegal activities targeting property as direct assaults on capitalist structures and state authority, viewing such practices as consistent with rejecting wage labor and proprietary norms.[68] Emerging primarily in France, Italy, Belgium, and Switzerland during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, illegalism gained prominence through figures associated with the Bonnot Gang, who between 1911 and 1912 conducted armed robberies and a bombing to fund anarchist activities and challenge bourgeois morality.[69] Proponents, such as Émile Armand, argued that illegalism aligns with egoist principles by prioritizing personal autonomy over legal constraints, critiquing reformist anarchism for compromising with societal laws.[70] Critics within broader anarchism, including some social anarchists, contend that illegalism risks alienating potential allies and romanticizes isolated acts without building collective power, though its defenders maintain it embodies uncompromising rejection of exploitation.[71] Individualist anarchism emphasizes the sovereignty of the individual over collective or state-imposed structures, advocating voluntary associations, mutual exchange, and personal responsibility as alternatives to coercive hierarchies.[72] Originating in the 19th century through thinkers like Max Stirner, who in The Ego and Its Own (1844) promoted egoism as the basis for rejecting external moralities, and American figures such as Benjamin Tucker and Lysander Spooner, who critiqued capitalism as a product of state-granted privileges like patents and tariffs.[73] Unlike social anarchism's focus on communal ownership, individualist variants often endorse free markets without state intervention, arguing that genuine competition would erode monopolies and enable workers to retain full product of their labor via mutual banking and cost-the-limit pricing.[74] This strand influenced later libertarian thought but remains distinct in its opposition to both capitalism and communism, prioritizing the unique over the general will, as articulated by John Henry Mackay in coining "individualist anarchism" to differentiate from revolutionary collectivism.[75] Insurrectionary anarchism prioritizes immediate, decentralized acts of revolt through small affinity groups over mass organization or waiting for favorable historical conditions, viewing insurrection as an ongoing process of attack against authority rather than a singular event.[76] Developing from Italian anarchist traditions in the late 19th century and refined by theorists like Alfredo M. Bonanno in works such as Insurrectionary Anarchy (1977), it rejects formal parties or unions as recuperative, instead promoting autonomous actions that propagate anarchy by example and disrupt power directly.[77] Insurrectionaries draw from historical precedents like the Galleanist movement led by Luigi Galleani, who between 1903 and 1932 advocated propaganda by deed through bombings and strikes targeting U.S. industrialists and officials.[78] The approach critiques syndicalism for potential co-optation, emphasizing that true revolution arises from the convergence of multiple insurrections exploiting crises, as seen in informal networks during events like the 1977 Italian "Years of Lead."[79] While effective in inspiring direct action, it faces criticism for underemphasizing sustained solidarity, though adherents argue it avoids the pitfalls of hierarchical vanguards.[80]J

Terms beginning with J

Jura Federation. The Jura Federation, formally the Fédération romande and later the Jura Federation of the International Workingmen's Association, was an anarchist organization founded on November 12, 1871, at a congress in Sonvilier, Switzerland, by anti-authoritarian socialists opposing Karl Marx's centralist tendencies within the First International. Centered among watchmakers in the Jura Mountains region of French-speaking Switzerland, it advocated federalism, workers' self-management, and rejection of state socialism, serving as a hub for Mikhail Bakunin's ideas of collective anarchism. [81] The federation coordinated international anarchist activity, publishing propaganda like the Bulletin de la Fédération Jurassienne and hosting congresses that emphasized mutual aid and anti-statism. [25] At its 1880 congress in La Chaux-de-Fonds, delegates adopted anarchist communism as the prevailing doctrine, influencing global anarchist movements by prioritizing abolition of wage labor and private property in favor of communal production. [82] Despite repression from Swiss authorities and internal debates, it dissolved by the mid-1880s but exemplified early anarchist internationalism grounded in local industrial worker networks. [83] Justice. In anarchist thought, justice refers to restitution and voluntary resolution of conflicts without coercive state institutions, emphasizing individual responsibility, community mediation, and prevention of harm through mutual agreements rather than punitive retribution. Anarchist theorists like David Wieck argue that true justice arises from non-coercive social norms where aggression against persons or property prompts compensatory remedies, such as restitution to victims, enforced via decentralized defense associations or social ostracism, avoiding the state's monopolized violence that often perpetuates inequality. [84] This contrasts with statist justice systems, which anarchists critique for privileging rulers and failing to address root causes like economic disparity; instead, anarchism posits justice as emergent from free associations ensuring equity without hierarchical adjudication. [85] Historical anarchist practices, such as those in the Spanish Revolution (1936–1939), implemented restorative councils for disputes, prioritizing rehabilitation and collective defense over incarceration, though outcomes varied due to wartime conditions. [86] Critics from non-anarchist perspectives question scalability, but proponents maintain empirical evidence from stateless societies shows lower coercion when power is diffused. [87]K

Terms beginning with K

Kabouters Kabouters, meaning "gnomes" in Dutch, referred to an anarchist group and political movement active primarily in the Netherlands during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Originating as a successor to the Provo countercultural movement, the Kabouters employed absurdist, playful tactics combining direct action, humor, and spectacle to challenge authority, urban development, and capitalist norms.[88] Influenced by Peter Kropotkin's ideas on mutual aid and communal organization, they advocated for ecological sustainability, free public spaces, and grassroots decision-making, often framing their activism around whimsical symbols like gnomes to subvert serious political discourse.[89] In April 1970, the Kabouters achieved electoral success by securing five seats on Amsterdam's 45-member city council through a campaign promising "groen kabouterakkoord" (green gnome accord) initiatives, including expanded squatting rights, free urban farming plots, and opposition to property speculation.[90] [91] Their council participation highlighted tensions within anarchism, as members debated reconciling anti-statist principles with electoral involvement, ultimately using positions to disrupt bureaucratic processes and promote community self-management.[92] The movement's emphasis on joy, creativity, and non-violent provocation distinguished it from more class-struggle-oriented anarchism, influencing later environmental and lifestyle anarchists by demonstrating cultural insurgency as a form of resistance.[93] By the mid-1970s, the group had largely dissolved amid internal divisions and shifting countercultural dynamics, though their legacy persists in Dutch activist traditions of ludic politics.[94]L

Terms beginning with L

Libertarian socialism is a political philosophy that advocates for the abolition of coercive state authority and capitalist hierarchies in favor of voluntary cooperation, worker self-management, and communal ownership of resources, emphasizing individual liberty alongside collective social organization.[95] It overlaps significantly with classical anarchism, particularly social anarchism, but distinguishes itself by explicitly rejecting authoritarian socialism, such as Leninist vanguardism, in favor of decentralized, non-hierarchical structures.[95] Proponents argue that true socialism requires libertarian methods to prevent the recreation of oppressive power dynamics, as evidenced in historical experiments like the Spanish CNT-FAI collectives during the 1936-1939 Revolution, where workers managed production without state mediation.[95] Lifestyle anarchism refers to a form of anarchism prioritizing personal autonomy, individual ethical choices, and cultural rebellion over organized mass movements for systemic change, often manifesting in practices like veganism, squatting, or anti-consumerist lifestyles.[96] Criticized by Murray Bookchin in his 1995 essay as a retreat from revolutionary politics into mysticism, primitivism, or vague anti-authoritarianism, it allegedly dilutes anarchism's potential by substituting symbolic gestures for confronting institutional power.[96] Bookchin contended that this approach, influenced by post-1960s counterculture, fosters narcissism and eschews rational social analysis, contrasting it with historical social anarchism's focus on class struggle and institutional reconstruction.[96] Defenders view it as a valid expression of immediate freedom, though it remains divisive, with Bookchin ultimately deeming the divide between lifestyle and social variants "unbridgeable."[96] Lumpenproletariat, a term originating in Marxist analysis to describe the "social scum" detached from productive labor—such as criminals, vagrants, and the chronically unemployed—has been reinterpreted in anarchist thought as a potentially revolutionary force unbound by bourgeois norms.[97] Mikhail Bakunin, in his 1870s writings, elevated the lumpenproletariat above the disciplined industrial proletariat, portraying urban outcasts and peasants as instinctive rebels driven by instinctual anti-authoritarianism rather than ideological discipline.[97] Unlike Marx's dismissal of them as counter-revolutionary parasites, Bakunin saw their marginality as embodying "actually existing anarchism," capable of spontaneous insurrection against both state and capital, as theorized in his advocacy for federated alliances of instinctive masses over proletarian vanguards.[97] This perspective influenced later anarchists like Erich Mühsam, who in the early 20th century highlighted their inherent anti-bourgeois ethos as a basis for direct action.[98]M

Terms beginning with M

MakhnovshchinaThe Makhnovshchina refers to the anarchist revolutionary movement in Ukraine from 1918 to 1921, led by Nestor Makhno, which sought to establish stateless communes based on free soviets, collective land ownership, and armed self-defense against both White and Red armies during the Russian Civil War.[99] The movement controlled territory in southern Ukraine, implementing agrarian reforms where peasants expropriated landlords' estates and organized production through voluntary councils, rejecting centralized Bolshevik authority in favor of federated, bottom-up decision-making.[100] It drew support from rural peasants, peaking with an insurgent army of up to 50,000 fighters by 1920, but collapsed after military defeats by Red Army forces in late 1921, with Makhno exiled thereafter.[99] Mutual aid

Mutual aid denotes voluntary cooperation among individuals or groups to meet collective needs through reciprocal support, a principle central to anarchist theory as an alternative to hierarchical state or market coercion.[101] Peter Kropotkin advanced the concept in his 1902 work Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, drawing on biological evidence from species behaviors to argue that solidarity, not competition, drives social evolution and human progress, countering Malthusian and Darwinist interpretations emphasizing struggle.[102] In practice, it manifests in autonomous networks like food distribution or disaster relief, emphasizing horizontal organization without leaders or profit motives, as seen in anarchist responses to crises where participants coordinate directly to share resources.[102] Mutualism

Mutualism is an anarchist economic doctrine originating with Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, advocating reciprocal exchange through free markets, mutual credit banks, and workers' control of production to eliminate exploitation without abolishing exchange or possession based on use.[103] It posits labor notes or time-based currency issued by mutual banks to facilitate equitable trade, enabling producers to retain full value of their output minus costs, as outlined in Proudhon's 1840 What Is Property? where he declared property as theft under capitalist absentee ownership but endorsed possession tied to labor.[104] Distinct from collectivism or communism, mutualism permits individual enterprise and contracts but opposes usury, rent, and profit from non-labor, aiming for a federated society of voluntary associations; modern variants adapt it to critique both state socialism and capitalism.[103]

N

Terms beginning with N

Anarcho-nihilism is a tendency within post-left anarchism that rejects constructive programs for social change, emphasizing instead the total negation and destruction of civilization, authority, and imposed values as ends in themselves rather than means to an alternative society.[105] Proponents view reality as devoid of inherent meaning or progress, prioritizing individual insurrection and attack over organized revolution or utopian visions, often critiquing mainstream anarchism for its reformist or moralistic tendencies.[105] This current draws historical influence from 19th-century Russian nihilism, a movement of the 1860s–1880s that combined materialist atheism, hedonism, and direct action against Tsarist authority, including assassinations like that of Tsar Alexander II in 1881 by the group Narodnaya Volya.[105] In contemporary usage, it manifests in informal affinity groups engaging in sabotage or propaganda of the deed, without commitment to ideological purity or collective structures.[106] Anarcho-naturism, also termed naturist anarchism, integrates anarchist opposition to hierarchy and coercion with naturist practices promoting harmony with nature through vegetarianism, nudism, free love, and small-scale ecological communities.[107] Emerging in late 19th-century Europe, particularly France and Spain, it sought to abolish industrial society alongside state and capitalist institutions, advocating voluntary, non-exploitative living in alignment with natural human impulses.[108] Key early influences included geographer Élisée Reclus, who linked anarchism to environmental stewardship; Leo Tolstoy's Christian anarchism with its emphasis on simple living; and Henry David Thoreau's transcendentalist critique of civilization.[107] By the early 20th century, it influenced naturist colonies and publications in Spain, such as those by Emilio Majó, though it waned amid broader anarchist repression during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939).[109] Modern echoes appear in green anarchism, but the pure form remains marginal, critiqued for potential escapism from urban class struggle.[110]P

Terms beginning with P

Personal property. In anarchist thought, personal property refers to items used directly by individuals for personal needs or production, such as tools, clothing, or homes, which are distinguished from private property that enables exploitation through absentee ownership or rent extraction.[111] Anarchists argue that personal property supports individual autonomy without hierarchical control, as opposed to capitalist private property that concentrates power.[112] Platformism. Platformism is an organizational approach in anarchism that advocates for structured anarchist groups based on theoretical unity, tactical unity, collective responsibility, and federalism to effectively engage in revolutionary activity and influence broader social movements.[113] Originating from the 1926 Organizational Platform of the General Union of Anarchists, drafted by Nestor Makhno and others in exile after the Russian Revolution, it seeks to overcome the fragmentation of anarchism by creating enduring organizations capable of coordinating actions while maintaining anarchist principles.[114] Critics within anarchism view it as potentially overly centralized, but proponents emphasize its role in building mass influence without vanguardism.[115] Primitivism. Anarcho-primitivism, often shortened to primitivism in anarchist contexts, critiques civilization as inherently coercive, advocating the dismantling of industrial society, technology, and symbolic divisions of labor to return to pre-civilized, small-scale, autonomous communities inspired by hunter-gatherer societies.[116] It posits that domestication, agriculture, and urbanization initiated hierarchy and alienation around 10,000 years ago, rendering modern progress illusory and destructive to human freedom and ecology.[117] Thinkers like John Zerzan argue that language, art, and technology themselves alienate, though the tendency emphasizes anti-systemic opposition rather than literal replication of past lifestyles.[118] Private property. Anarchists oppose private property as a system of exclusionary ownership over land, resources, and means of production that allows a minority to extract surplus value from others' labor, perpetuating exploitation and inequality.[119] Pierre-Joseph Proudhon famously declared "property is theft" in 1840, arguing it arises not from natural right but from social arrangements enabling idleness to live off workers.[112] While individualist anarchists like Benjamin Tucker defended limited private property under mutualist banking to abolish rent and interest, social anarchists seek its abolition in favor of communal or possessory use to eliminate coercive hierarchies.[120] Propaganda of the deed. Propaganda of the deed denotes revolutionary actions, often violent, intended to inspire mass uprising by demonstrating anarchism's feasibility and striking against authority, a tactic prominent in late 19th-century insurrectionary anarchism.[121] Coined in the 1870s by Italian anarchists like Errico Malatesta and popularized by Johann Most, it involved assassinations and bombings, such as the 1898 killing of Empress Elisabeth of Austria, but largely failed to spark widespread revolt, leading to its decline by the early 20th century amid state repression.[122] Modern interpretations broaden it to non-violent exemplars of mutual aid, though historical usage centered on direct confrontation to propagate ideas through exemplary force.[123] Proudhonism. Proudhonism encompasses the mutualist philosophy of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, emphasizing federalism, workers' self-management, and the abolition of private property in favor of possession based on use, while rejecting state socialism and capitalism.[124] In works like What Is Property? (1840), Proudhon advocated reciprocal exchange through mutual credit banks and federated producers' associations to achieve economic justice without authority.[125] His rationalist, anti-utopian approach influenced anarchism's critique of both state and capital, though his views on gender and gradualism drew later criticism; it laid groundwork for syndicalism and remains foundational to market-oriented anarchist variants.[125]R

Terms beginning with R

RecuperationIn anarchist theory, recuperation refers to the process by which radical or subversive ideas, movements, or practices are co-opted, neutralized, or integrated into the dominant capitalist or state structures, thereby diluting their revolutionary potential.[126] This concept, originating from Situationist International critiques in the mid-20th century, highlights how opposition can be transformed into commodities or reforms that reinforce existing power relations, such as turning protest symbols into marketable merchandise or absorbing activist demands into bureaucratic policies.[127] Anarchists view recuperation as a key mechanism of social control, exemplified in historical instances like the commercialization of punk aesthetics or the institutionalization of environmental activism within state frameworks, urging ongoing vigilance against such absorption to preserve autonomous resistance.[128] Rational anarchy

Rational anarchy denotes a form of social organization based on voluntary cooperation and individual responsibility without imposed authority, emphasizing direct popular sovereignty through mechanisms like voting on laws while rejecting hierarchical mediation.[129] Coined in 19th-century anarchist discourse, as articulated by figures like Émile Digeon, it posits that true anarchy arises from rational adherence to mutual duties derived from personal accountability rather than external rulers, contrasting with irrational or coercive governance.[130] Later interpretations, such as in Robert A. Heinlein's 1966 novel The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress, frame it as a recognition that individuals bear ultimate responsibility for outcomes in a stateless society, aligning with anarchist critiques of absentee authority while grounding order in self-governance and ethical reciprocity.[131]

S

Terms beginning with S

Syndicalism is a revolutionary strategy within anarchism that emphasizes labor unions, or syndicates, as the primary means to abolish capitalism and the state through direct action, such as general strikes and workplace expropriation.[132] Anarcho-syndicalism, its most prominent variant, posits that federated unions can organize production and distribution in a stateless society, rejecting political parties in favor of economic self-management by workers.[16] This approach emerged in the late 19th century among European anarchists influenced by Mikhail Bakunin, who advocated workers' organizations as dual-power structures capable of seizing control during insurrections.[133] Historical examples include the Spanish CNT's role in the 1936 revolution, where syndicates collectivized industries, demonstrating syndicalism's practical application despite ultimate defeat by fascist and communist forces.[17] Synthesis anarchism denotes an organizational principle aiming to unify diverse anarchist tendencies—such as communist, syndicalist, and individualist—into a single federation without ideological hegemony, prioritizing practical cooperation over doctrinal purity.[134] Coined in the 1920s by figures like Voline and Sébastien Faure amid post-Russian Revolution fragmentation, it counters platformism's emphasis on tactical unity by embracing pluralism to broaden the movement's appeal and resilience.[134] Proponents argue this synthesis fosters mutual aid across differences, as seen in early 20th-century French and Russian groups, though critics contend it dilutes revolutionary focus by accommodating incompatible views like egoism and collectivism.[135] Spontaneity, in anarchist theory, refers to self-organized, non-hierarchical action arising from shared needs or circumstances, exemplified by the "theory of spontaneous order" where common interests generate voluntary associations without central authority.[136] Anarchists like Colin Ward highlighted its historical precedents, from medieval commons to modern squats, positing that spontaneity counters imposed structures by enabling adaptive, bottom-up coordination, as in the 1910-1920 shop stewards' movements in Britain.[136] Murray Bookchin described it as unconstrained behavior fostering creativity, yet warned against romanticizing it without organizational supports to prevent co-optation or failure, distinguishing it from undirected chaos.[137] This concept underpins critiques of vanguardism, asserting that mass actions, like the 1968 French general strike involving 10 million workers, reveal innate capacities for self-governance.[137] Squatting constitutes a direct action tactic in anarchism involving the occupation of vacant properties to assert use-rights over ownership, challenging capitalist property norms and creating autonomous spaces for communal living and activism.[138] Originating as a survival strategy, it aligns with anarchist rejection of absentee landlordism, with historical instances like 1970s European movements establishing social centers that hosted countercultural projects until state crackdowns.[139] Anarchists view squatting as prefigurative politics, subverting real estate dominance while experimenting with consensus-based management, though evictions—such as the 2010 Dutch ban affecting hundreds of sites—underscore its precariousness against legal and police reprisals.[138][139]T

Terms beginning with T

Temporary Autonomous Zone (TAZ)A concept introduced by anarchist writer Hakim Bey (pseudonym of Peter Lamborn Wilson) in his 1991 book T.A.Z.: The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism, published by Autonomedia.[140] The TAZ describes short-lived spaces or moments of autonomy where individuals escape state control, creating temporary communities based on voluntary participation, creativity, and mutual aid without hierarchical structures.[141] Bey contrasts it with permanent revolutions, arguing it avoids direct confrontation with the state, instead "raiding" spaces of time, land, or imagination for fleeting liberation, as in pirate utopias or festivals.[140] Critics within anarchism view the TAZ as insufficiently committed to sustained social transformation, potentially romanticizing ephemerality over structural change.[142] Treintismo

A faction within the Spanish National Confederation of Labor (CNT) during the Second Spanish Republic, emerging in the early 1930s and named after the "Manifesto of the Thirty" signed by 30 CNT members on August 3, 1931.[143] Led by figures like Ángel Pestaña, treintistas advocated a pragmatic, reformist approach to anarcho-syndicalism, emphasizing union organization, legal participation in elections, and gradual preparation for revolution over immediate insurrection. This positioned them against the more purist, insurrectionary stance of the Iberian Anarchist Federation (FAI), which accused them of diluting anarchist principles through collaboration with republican institutions.[144] The movement gained traction amid CNT's growth to over 1 million members by 1931 but waned after internal conflicts, including Pestaña's expulsion in 1932, contributing to tensions before the 1936 Spanish Revolution.[145] Tax resistance

A practice of refusing to pay taxes, particularly those funding war or state coercion, rooted in anarchist opposition to involuntary extraction as a form of theft and legitimation of hierarchy.[146] In the U.S., anarchists have historically resisted federal income taxes and phone taxes since the 1960s Vietnam War era, viewing them as direct support for militarism and imperialism.[147] Influenced by thinkers like Henry David Thoreau's 1849 essay Civil Disobedience, which inspired non-payment of poll taxes for moral resistance, modern examples include Catholic Worker movement members like Dorothy Day, who cited anarchist Ammon Hennacy's total tax refusal starting in 1941.[148] Anarchist tax resisters prioritize voluntary mutual aid over state redistribution, often facing legal penalties but using nonviolent tactics to highlight coercion.[149]

V

Terms beginning with V

Veganarchism is a political philosophy integrating veganism—defined as abstaining from animal products and exploitation—with anarchism's opposition to all hierarchies, including speciesism.[150] Proponents argue that state and capitalist structures perpetuate animal oppression alongside human domination, advocating direct action for animal liberation as part of broader social revolution.[150] This synthesis emerged in the late 20th century among green anarchists, emphasizing mutual aid extending to non-human animals and critiquing industrial agriculture as coercive.[151] Voluntaryism denotes a doctrine insisting on voluntary association as the sole legitimate basis for social order, rejecting coercion including taxation and state monopoly on force.[152] Originating with 19th-century thinkers like Auberon Herbert, it posits that all services, including defense and dispute resolution, should arise from consensual contracts rather than imposed authority.[152] Within anarchism, voluntaryism aligns closely with individualist and market-oriented variants, prioritizing non-aggression and private property, though collectivists critique it for potentially enabling capitalist hierarchies under voluntary guise.[153] Historical applications include proposals for competing private agencies replacing state functions, as outlined in Herbert's 1897 pamphlet The Principles of Voluntaryism and Free Life.[152]W

Terms beginning with W

Wage slavery Wage slavery denotes the anarchist critique of capitalist wage labor as a system wherein workers, lacking independent access to land or productive resources, must sell their labor power to employers for survival, subjecting them to coercive dependency despite formal freedom to contract.[154] Anarchists contend this arrangement extracts surplus value through unequal bargaining power, mirroring slavery's alienation of labor while avoiding chattel bondage, as workers retain nominal liberty to quit but face impoverishment or starvation as alternatives.[155] The term underscores how private ownership of means of production enforces involuntary subordination, with employers dictating terms akin to masters over slaves.[156] The phrase gained traction in 19th-century radical discourse, notably among American individualist anarchists like Lysander Spooner, who in works such as his 1834 "The Unconstitutionality of Slavery" extended abolitionist logic to wage systems, arguing that economic necessity compels consent indistinguishable from force.[157] European anarchists, including Mikhail Bakunin and Peter Kropotkin, integrated it into broader anti-capitalist analysis, viewing wage labor as perpetuating hierarchy and exploitation under the guise of free exchange; Bakunin, in "The Knouto-Germanic Empire and the Social Revolution" (1871), described it as modern serfdom binding workers to bourgeois overlords. Empirical observations of industrial conditions—such as 12-16 hour factory shifts in 19th-century Europe and America, where child labor and debt peonage were rampant—bolstered claims of systemic coercion, with data from the U.S. Census of 1880 revealing over 1 million children under 15 in wage labor amid widespread poverty.[158] Critics, including some economists, counter that wage labor enables voluntary exchange and mobility, citing rising real wages—from $0.20 daily for unskilled U.S. workers in 1860 to $1.50 by 1900, adjusted for inflation—as evidence against equivalence to slavery, where exit barriers were absolute.[156] Anarchists rebut this by emphasizing structural barriers: without collective ownership or mutual aid networks, individual quits yield little, as market concentration—e.g., monopolies controlling 70% of U.S. steel by 1901—limits alternatives, rendering "freedom" illusory.[155] This debate highlights anarchism's causal realism, tracing exploitation not to isolated contracts but to property regimes enabling it, with historical revolts like the 1877 U.S. railroad strikes involving 100,000 workers protesting wage cuts as affirmations of the concept's resonance.[158]Z

Terms beginning with Z

Zenarchy is a syncretic philosophy blending Zen Buddhist practices with anarchist principles, advocating a passive, non-confrontational route to social disorder through meditation, detachment, and rejection of political engagement. Coined by Kerry Wendell Thornley in his 1970s writings, it posits that true anarchy emerges from individual enlightenment rather than organized resistance, critiquing activist anarchism as perpetuating the hierarchies it seeks to dismantle.[159][160] Zine, short for fanzine or magazine, denotes a self-published, low-circulation booklet of original or compiled content, frequently employed in anarchist subcultures to propagate anti-authoritarian ideas, tactical knowledge, and cultural critiques beyond state-controlled or commercial channels. Emerging prominently in the 1970s punk scenes intertwined with anarchism, zines facilitate decentralized information sharing via photocopied or digital means, emphasizing amateur production and collective authorship to foster resistance networks.[161][162]Debates and Criticisms

Key Controversial Concepts in Anarchism