Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Lepidosauria

View on Wikipedia

| Lepidosauria | |

|---|---|

| |

| Collage of five lepidosaurs. Clockwise from top left: tuatara, black mamba, green iguana, Smaug breyeri and reticulated python | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Lepidosauromorpha |

| Superorder: | Lepidosauria Haeckel, 1866 |

| Orders and genera | |

| |

The Lepidosauria (/ˌlɛpɪdoʊˈsɔːriə/, from Greek meaning scaled lizards) is a superorder[1] of reptiles, containing the orders Squamata and Rhynchocephalia. Squamata also includes lizards and snakes.[2] Squamata contains over 9,000 species, making it by far the most species-rich and diverse order of non-avian reptiles in the present day.[3] Rhynchocephalia was a formerly widespread and diverse group of reptiles in the Mesozoic Era.[4] However, it is represented by only one living species: the tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus), a superficially lizard-like reptile native to New Zealand.[5][6]

Lepidosauria is a monophyletic group (i.e. a clade), containing all descendants of the last common ancestor of squamates and rhynchocephalians.[7] Lepidosaurs can be distinguished from other reptiles via several traits, such as large keratinous scales which may overlap one another. Purely in the context of modern taxa, Lepidosauria can be considered the sister taxon to Archelosauria, which includes Testudines (turtles), Aves (birds) and Crocodilia (crocodilians). Lepidosauria is encompassed by Lepidosauromorpha, a broader group defined as all reptiles (living or extinct) closer to lepidosaurs than to archosaurs.

Evolution

[edit]Lepidosauromorpha is thought to have split from their sister group, Archelosauria, during the Permian period.[8] The earliest members of Lepidosauromorpha date to the Early Triassic. The oldest known definitive lepidosaur is the rhynchocephalian Agriodontosaurus from the Helsby Sandstone Formation of the United Kingdom, dating to the upper Anisian stage of the Middle Triassic, approximately 244 to 241.5 million years ago.[9] The next earliest rhynchocephalian, Wirtembergia, is known from the Ladinian stage of the Middle Triassic.[10] Sophineta is known from older rocks in the Early Triassic, but its exact placement within the broader clade Lepidosauromorpha is uncertain and it may not be a true lepidosaur.[11] While the lepidosaur Megachirella may represent a stem-group squamate from the Middle Triassic,[12] the earliest modern members of the group are known from the Middle Jurassic.[13] Squamates underwent a great radiation in the Cretaceous,[14] while rhynchocephalians declined during the same time period.[15]

Description

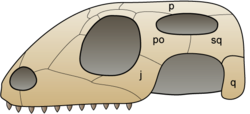

[edit]Extant reptiles are in the clade Diapsida, named for the two pairs of temporal fenestrae present on the skull behind the eye socket.[16] Until recently, Diapsida was said to be composed of Lepidosauria and their sister taxa Archosauria.[17] The Lepidosauria is then split into Squamata[18] and Rhynchocephalia. More recent morphological studies[19][20] and molecular studies[21][22][23][24][25][26][excessive citations] also place turtles firmly within Diapsida, even though they lack temporal fenestrations.

The reptiles in the Lepidosauria can be distinguished from other reptiles by a variety of characteristics.[27] Lepidosaurs are suggested to be distinguished from more primitive lepidosauromorphs by the development of a conch on the quadrate, allowing for the development of a tympanic membrane in the ear (a trait lost in the tuatara, but present in early rhynchocephalians), as well as the development of a subolfactory process on the frontal bones of the skull.[11][28]

The group Squamata[18] includes snakes, lizards, and amphisbaenians. Squamata can be characterized by the reduction or loss of limbs. Snakes and legless lizards have evolved the complete loss of their limbs. The upper jaw of Squamates is movable on the cranium, a configuration called kinesis.[29] This is made possible by a loose connection between the quadrate and its neighboring bones.[30] Without this, snakes would not be able consume prey that are much larger than themselves. Amphisbaenians are mostly legless like snakes, but are generally much smaller. Three species of amphisbaenians have kept reduced front limbs and these species are known for actively burrowing in the ground.[31] The tuatara and some extinct rhynchocephalians have a more rigid skull with a complete lower temporal bar closing the lower temporal fenestra formed by the fusion of the jugal and quadrate/quadratojugal bones, similar to the condition found in primitive diapsids. However early rhynchocephalians and lepidosauromorphs had an open lower temporal fenestra, without a complete temporal bar, so this is thought to be a reversion rather than retention. The temporal bar is thought to stabilise the skull during biting.[32]

Male squamates have evolved a pair of hemipenises instead of a single penis with erectile tissue that is found in crocodilians, birds, mammals, and turtles. The hemipenis can be found in the base of the tail. The tuatara does not have a hemipenis, but instead has shallow paired outpocketings of the posterior wall of the cloaca.[17]

Second, most lepidosaurs have the ability to autotomize their tails. However, this trait has been lost on some recent species. In lizards and rhynchocephalians, fracture planes are present within the vertebrae of the tail that allow for its removal. Some lizards have multiple fracture planes, while others just have a single fracture plane. The regrowth of the tail is not always complete and is made of a solid rod of cartilage rather than individual vertebrae.[17] In snakes, the tail separates between vertebrae and some do not experience regrowth.[17]

Third, the scales in lepidosaurs are horny (keratinized) structures of the epidermis, allowing them to be shed collectively, contrary to the scutes seen in other reptiles.[17] This is done in different cycles, depending on the species. However, lizards generally shed in flakes while snakes shed in one piece. Unlike scutes, lepidosaur scales will often overlap like roof tiles.

Biology and ecology

[edit]

Squamates are represented by viviparous, ovoviviparous, and oviparous species. Viviparous means that the female gives birth to live young, Ovoviviparous means that the egg will develop inside the female's body and Oviparous means that the female lays eggs. A few species within Squamata have the ability to reproduce asexually.[33] The tuatara lays eggs that are usually about one inch in length and which take about 14 months to incubate.[29]

While in the egg, the Squamata embryo develops an egg tooth on the premaxillary that helps the animal emerge from the egg.[34] A reptile will increase three to twentyfold in length from hatching to adulthood.[34] There are three main life history events that lepidosaurs reach: hatching/birth, sexual maturity, and reproductive senility.[34]

Because gular pumping is so common in squamates, and is also found in the tuatara, it is assumed that it is an original trait in the group.[35]

Most lepidosaurs rely on camouflage as one of their main defenses. Some species have evolved to blend in with their ecosystem, while others are able to change their skin color to blend in with their current surroundings. The ability to autotomize the tail is another defense that is common among lepidosaurs. Other species, such as the Echinosauria, have evolved the defense of feigning death.[34]

Hunting and diet

[edit]

Viperines can sense their prey's infrared radiation through bare nerve endings on the skin of their heads.[34] Also, viperines and some boids have thermal receptors that allow them to target their prey's heat.[34] Many snakes are able to obtain their prey through constriction. This is done by first biting the prey, then coiling their body around the prey. The snake then tightens its grip as the prey struggles, which leads to suffocation.[34] Some snakes have fangs that produce venomous bites, which allows the snake to consume unconscious, or even dead, prey. Also, some venoms include a proteolytic component that aids in digestion.[34] Chameleons grasp their prey with a projectile tongue. This is made possible by a hyoid mechanism, which is the contraction of the hyoid muscle that drives the tip of the tongue outwards.[34]

Within the Lepidosauria there are herbivores, omnivores, insectivores, and carnivores. The herbivores consist of iguanines, some agamids, and some skinks.[34] Most lizard species and some snake species are insectivores. The remaining snake species, tuataras, and amphisbaenians, are carnivores. While some snake species are generalist, others eat a narrow range of prey - for example, Salvadora only eat lizards.[34] The remaining lizards are omnivores and can consume plants or insects. The broad carnivorous diet of the tuatara may be facilitated by its specialised shearing mechanism, which involves a forward movement of the lower jaw following jaw closure.[36]

While birds, including raptors, wading birds and roadrunners, and mammals are known to prey on reptiles, the major predator is other reptiles. Some reptiles eat reptile eggs, for example the diet of the Nile monitor includes crocodile eggs, and small reptiles are preyed upon by larger ones.[34]

Conservation

[edit]

The geographic ranges of lepidosaurs are vast and cover all but the most extreme cold parts of the globe. Amphisbaenians exist in Florida, mainland Mexico, including Baja California, the Mediterranean region, the Middle East, North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa, South America, and the Caribbean.[30] The tuatara is confined to only a few rocky islands of New Zealand, where it digs burrows to live in and preys mostly on insects.[29]

Climate change has led to the need for conservation efforts to protect the existence of the tuatara. This is because it is not possible for this species to migrate on its own to cooler areas. Conservationists are beginning to consider the possibility of translocating them to islands with cooler climates.[37] The range of the tuatara has already been minimized by the introduction of cats, rats, dogs, and mustelids to New Zealand.[38] The eradication of the mammals from the islands where the tuatara still survives has helped the species increase its population. An experiment observing the tuatara population after the removal of the Polynesian rat showed that the tuatara expressed an island-specific increase of population after the rats' removal.[39] However, it may be difficult to keep these small mammals from reinhabiting these islands.

Habitat destruction is the leading negative impact of humans on reptiles. Humans continue to develop land that is important habitat for the lepidosaurs. The clear-cutting of land has also led to habitat reduction. Some snakes and lizards migrate toward human dwellings because there is an abundance of rodent and insect prey. However, these reptiles are seen as pests and are often exterminated.[17]

Interactions with humans

[edit]

Snakes are commonly feared throughout the world. Bounties were paid for dead cobras under the British Raj in India; similarly, there have been advertised rattlesnake roundups in North America. Data shows that between 1959 and 1986 an average of 5,563 rattlesnakes were killed per year in Sweetwater, Texas, due to rattlesnake roundups, and these roundups have led to documented declines and local extirpations of rattlesnake populations, especially Eastern Diamondbacks in Georgia.[17]

People have introduced species to the lepidosaurs' natural habitats that have increased predation on the reptiles. For example, mongooses were introduced to Jamaica from India to control the rat infestation in sugar cane fields. As a result, the mongooses fed on the lizard population of Jamaica, which has led to the elimination or decrease of many lizard species.[17] Actions can be taken by humans to help endangered reptiles. Some species are unable to be bred in captivity, but others have thrived. There is also the option of animal refuges. This concept is helpful to contain the reptiles and keep them from human dwellings. However, environmental fluctuations and predatorial attacks still occur in refuges.[34]

Reptile skins are still being sold. Accessories, such as shoes, boots, purses, belts, buttons, wallets, and lamp shades, are all made out of reptile skin.[17] In 1986, the World Resource Institute estimated that 10.5 million reptile skins were traded legally. This total does not include the illegal trades of that year.[17] Horned lizards are popularly harvested and stuffed.[17] Some humans are making a conscious effort to preserve the remaining species of reptiles, however.

References

[edit]- ^ Herrera-Flores, Jorge A.; Stubbs, Thomas L.; Elsler, Armin; Benton, Michael J. (2018-04-06). "Taxonomic reassessment of Clevosaurus latidens Fraser, 1993 (Lepidosauria, Rhynchocephalia) and rhynchocephalian phylogeny based on parsimony and Bayesian inference". Journal of Paleontology. 92 (4): 734–742. doi:10.1017/jpa.2017.136. ISSN 0022-3360.

- ^ Pyron, RA; Burbrink, FT; Wiens, JJ (2013). "A phylogeny and revised classification of Squamata, including 4,161 species of lizards and snakes". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 13 (1): 93. Bibcode:2013BMCEE..13...93P. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-13-93. PMC 3682911. PMID 23627680.

- ^ Uetz, Peter (13 January 2010). "The original descriptions of reptiles". Zootaxa. 2334 (1): 59–68. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2334.1.3.

- ^ Jones, M.E.H. (2009). "Dentary Tooth Shape in Sphenodon and Its Fossil Relatives (Diapsida: Lepidosauria: Rhynchocephalia)". Frontiers of Oral Biology. 13: 9–15. doi:10.1159/000242382. ISBN 978-3-8055-9229-1. PMID 19828962.

- ^ Hay, Jennifer M.; Sarre, Stephen D.; Lambert, David M.; Allendorf, Fred W.; Daugherty, Charles H. (June 2010). "Genetic diversity and taxonomy: a reassessment of species designation in tuatara (Sphenodon: Reptilia)". Conservation Genetics. 11 (3): 1063–1081. Bibcode:2010ConG...11.1063H. doi:10.1007/s10592-009-9952-7. hdl:10072/30480. S2CID 24965201.

- ^ Jones, M.E.H.; Cree, A. (2012). "Tuatara". Current Biology. 22 (23): 986–987. Bibcode:2012CBio...22.R986J. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2012.10.049. PMID 23218010.

- ^ Evans, S.E.; Jones, M.E.H. (2010). "The Origin, early history and diversification of lepidosauromorph reptiles". In Bandyopadhyay, S. (ed.). New Aspects of Mesozoic Biodiversity. Lecture Notes in Earth Sciences. Vol. 132. pp. 27–44. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-10311-7_2. ISBN 978-3-642-10310-0.

- ^ Simões, T. R.; Kammerer, C. F.; Caldwell, M. W.; Pierce, S. E. (2022). "Successive climate crises in the deep past drove the early evolution and radiation of reptiles". Science Advances. 8 (33) eabq1898. Bibcode:2022SciA....8.1898S. doi:10.1126/sciadv.abq1898. PMC 9390993. PMID 35984885.

- ^ Marke, Daniel; Whiteside, David I.; Sethapanichsakul, Thitiwoot; Coram, Robert A.; Fernandez, Vincent; Liptak, Alexander; Newham, Elis; Benton, Michael J. (2025-09-10). "The oldest known lepidosaur and origins of lepidosaur feeding adaptations". Nature: 1–10. doi:10.1038/s41586-025-09496-9. ISSN 1476-4687.

- ^ Sues, Hans-Dieter; Schoch, Rainer R. (2023-11-07). "The oldest known rhynchocephalian reptile from the Middle Triassic (Ladinian) of Germany and its phylogenetic position among Lepidosauromorpha". The Anatomical Record. 307 (4): 776–790. doi:10.1002/ar.25339. ISSN 1932-8486. PMID 37937325. S2CID 265050255.

- ^ a b Ford, David P.; Evans, Susan E.; Choiniere, Jonah N.; Fernandez, Vincent; Benson, Roger B. J. (2021-08-25). "A reassessment of the enigmatic diapsid Paliguana whitei and the early history of Lepidosauromorpha". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 288 (1957) 20211084. doi:10.1098/rspb.2021.1084. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 8385343. PMID 34428965.

- ^ Simōes, Tiago R.; Caldwell, Michael W.; Talanda, Mateusz; Bernardi, Massimo; Palci, Alessandro; Vernygora, Oksana; Bernardini, Federico; Mancini, Lucia; Nydam, Randall L. (30 May 2018). "The origin of squamates revealed by a Middle Triassic lizard from the Italian Alps". Nature. 557 (7707): 706–709. Bibcode:2018Natur.557..706S. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0093-3. PMID 29849156. S2CID 44108416.

- ^ Rage, Jean-Claude (December 2013). "Mesozoic and Cenozoic squamates of Europe". Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments. 93 (4): 517–534. Bibcode:2013PdPe...93..517R. doi:10.1007/s12549-013-0124-x. ISSN 1867-1594. S2CID 128588324.

- ^ Herrera-Flores, Jorge A.; Stubbs, Thomas L.; Benton, Michael J. (March 2021). "Ecomorphological diversification of squamates in the Cretaceous". Royal Society Open Science. 8 (3) rsos.201961. Bibcode:2021RSOS....801961H. doi:10.1098/rsos.201961. ISSN 2054-5703. PMC 8074880. PMID 33959350.

- ^ Anantharaman, S.; DeMar, David G.; Sivakumar, R.; Dassarma, Dilip Chandra; Wilson Mantilla, Gregory P.; Wilson Mantilla, Jeffrey A. (2022-06-30). "First rhynchocephalian (Reptilia, Lepidosauria) from the Cretaceous–Paleogene of India". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 42 (1). Bibcode:2022JVPal..42E8059A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2022.2118059. ISSN 0272-4634.

- ^ Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas Sturges (1986). The Vertebrate Body. Saunders. ISBN 978-0-03-058446-6.[page needed]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Pough, F. Harvey; Andrews, Robin M.; Cadle, John E.; Crump, Martha L.; Savitzky, Alan H.; Wells, Kentwood D. (1998). Herpetology. Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-850876-0.[page needed]

- ^ a b Reeder, Tod W.; Townsend, Ted M.; Mulcahy, Daniel G.; Noonan, Brice P.; Wood, Perry L.; Sites, Jack W.; Wiens, John J. (24 March 2015). "Integrated Analyses Resolve Conflicts over Squamate Reptile Phylogeny and Reveal Unexpected Placements for Fossil Taxa". PLOS ONE. 10 (3) e0118199. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1018199R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0118199. PMC 4372529. PMID 25803280.

- ^ Rieppel, O.; DeBraga, M. (1996). "Turtles as diapsid reptiles" (PDF). Nature. 384 (6608): 453–5. Bibcode:1996Natur.384..453R. doi:10.1038/384453a0. S2CID 4264378.

- ^ Müller, Johannes (2004). "The relationships among diapsid reptiles and the influence of taxon selection" (PDF). In Arratia, G; Wilson, M.V.H.; Cloutier, R. (eds.). Recent Advances in the Origin and Early Radiation of Vertebrates. Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil. pp. 379–408. ISBN 978-3-89937-052-2.

- ^ Mannen, Hideyuki; Li, Steven S. -L. (Oct 1999). "Molecular evidence for a clade of turtles". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 13 (1): 144–148. Bibcode:1999MolPE..13..144M. doi:10.1006/mpev.1999.0640. PMID 10508547.

- ^ Zardoya, R.; Meyer, A. (1998). "Complete mitochondrial genome suggests diapsid affinities of turtles". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 95 (24): 14226–14231. Bibcode:1998PNAS...9514226Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.24.14226. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 24355. PMID 9826682.

- ^ Iwabe, N.; Hara, Y.; Kumazawa, Y.; Shibamoto, K.; Saito, Y.; Miyata, T.; Katoh, K. (2004-12-29). "Sister group relationship of turtles to the bird-crocodilian clade revealed by nuclear DNA-coded proteins". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 22 (4): 810–813. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi075. PMID 15625185.

- ^ Roos, Jonas; Aggarwal, Ramesh K.; Janke, Axel (Nov 2007). "Extended mitogenomic phylogenetic analyses yield new insight into crocodylian evolution and their survival of the Cretaceous–Tertiary boundary". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 45 (2): 663–673. Bibcode:2007MolPE..45..663R. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2007.06.018. PMID 17719245.

- ^ Katsu, Y.; Braun, E. L.; Guillette, L. J. Jr.; Iguchi, T. (2010-03-17). "From reptilian phylogenomics to reptilian genomes: analyses of c-Jun and DJ-1 proto-oncogenes". Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 127 (2–4): 79–93. doi:10.1159/000297715. PMID 20234127. S2CID 12116018.

- ^ Tyler R. Lyson; Erik A. Sperling; Alysha M. Heimberg; Jacques A. Gauthier; Benjamin L. King; Kevin J. Peterson (2012-02-23). "MicroRNAs support a turtle + lizard clade". Biology Letters. 8 (1): 104–107. Bibcode:2012BiLet...8..104L. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2011.0477. PMC 3259949. PMID 21775315.

- ^ Evans, S.E. (2003). "At the feet of the dinosaurs: the early history and radiation of lizards" (PDF). Biological Reviews. 78 (4): 513–551. doi:10.1017/S1464793103006134. PMID 14700390. S2CID 4845536. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-02-19.

- ^ Evans, Susan E. (2016), Clack, Jennifer A.; Fay, Richard R; Popper, Arthur N. (eds.), "The Lepidosaurian Ear: Variations on a Theme", Evolution of the Vertebrate Ear, Springer Handbook of Auditory Research, vol. 59, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 245–284, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46661-3_9, ISBN 978-3-319-46659-0, retrieved 2024-01-08

- ^ a b c Bellairs, Angus d'A (1960). Reptiles life history, evolution, and structure. Harper. OCLC 692993911.[page needed]

- ^ a b Benton, M. J (1988). The Phylogeny and classification of the tetrapods. Oxford. OCLC 681456805.[page needed]

- ^ Vidal, Nicolas; Hedges, S. Blair (February 2009). "The molecular evolutionary tree of lizards, snakes, and amphisbaenians". Comptes Rendus Biologies. 332 (2–3): 129–139. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2008.07.010. PMID 19281946. S2CID 23137302.

- ^ Simões, Tiago R.; Kinney-Broderick, Grace; Pierce, Stephanie E. (2022-03-03). "An exceptionally preserved Sphenodon-like sphenodontian reveals deep time conservation of the tuatara skeleton and ontogeny". Communications Biology. 5 (1): 195. doi:10.1038/s42003-022-03144-y. ISSN 2399-3642. PMC 8894340. PMID 35241764.

- ^ Smith, James G (2010). "Survival estimation in a long-lived monitor lizard: radio-tracking of Varanus mertensi". Population Ecology. 52 (1): 243–247. Bibcode:2010PopEc..52..243S. doi:10.1007/s10144-009-0166-0. S2CID 43055329.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Zug, George R. (1993). Herpetology: An Introductory Biology of Amphibians and Reptiles. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-782620-2.[page needed]

- ^ Functional morphology and evolution of aspiration breathing in tetrapods

- ^ Jones, M.E.H.; O'Higgins, P.; Fagan, M.; Evans, S.E.; Curtis, N. (2012). "Shearing mechanics and the influence of a flexible symphysis during oral food processing in Sphenodon (Lepidosauria: Rhynchocephalia)". The Anatomical Record. 295 (7): 1075–1091. doi:10.1002/ar.22487. PMID 22644955. S2CID 45065504.

- ^ Besson, A. A.; Cree, A. (2011). "Integrating physiology into conservation: an approach to help guide translocations of a rare reptile in a warming environment". Animal Conservation. 14 (1): 28–37. Bibcode:2011AnCon..14...28B. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2010.00386.x. S2CID 84015883.

- ^ Nelson, Nicola J.; et al. (2002). "Establishing a new wild population of tuatara (Sphendon guntheri)". Conservation Biology. 16 (4): 887–894. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2002.00381.x. S2CID 85262510.

- ^ Towns, David R (2009). "Eradication as reverse invasion: lesions from Pacific Rat (Rattus exulans) removals on New Zealand islands". Biol Invasions. 11 (7): 1719–1733. Bibcode:2009BiInv..11.1719T. doi:10.1007/s10530-008-9399-7. S2CID 44200993.

External links

[edit]Lepidosauria

View on GrokipediaLepidosauria is a monophyletic clade of diapsid reptiles defined as the most recent common ancestor of Squamata and Rhynchocephalia (including the tuatara Sphenodon) and all descendants thereof, encompassing over 12,000 extant species primarily within Squamata (lizards, snakes, and amphisbaenians) alongside the two species of tuatara.[1][2]

This group represents the most species-rich lineage of land-dwelling vertebrates, with Squamata alone accounting for the vast majority of diversity due to extensive adaptive radiations.[1][3]

Lepidosaurs originated during the Triassic period, approximately 240–250 million years ago, as evidenced by integrated molecular and fossil data pushing back the crown-group divergence from earlier estimates.[3]

Key defining traits include overlapping keratinous scales, periodic ecdysis (skin shedding), and in many squamates, a kinetic skull enabling flexible jaw movement for prey capture, though the tuatara retains a more rigid acrodont dentition and skull structure reflective of its basal position.[4][5]

Ecologically, lepidosaurs exhibit remarkable versatility, occupying terrestrial, arboreal, fossorial, and marine niches worldwide, with evolutionary innovations such as limblessness in snakes and amphisbaenians facilitating specialized locomotion and foraging strategies.[6][7]

Classification and Phylogeny

Defining Characteristics

Lepidosauria is diagnosed by several synapomorphic traits that unite Squamata (lizards, snakes, and amphisbaenians) and Rhynchocephalia (tuatara), distinguishing the clade from other saurians. These include a transverse cloacal slit oriented horizontally, contrasting with the longitudinal configuration in archosaurs and turtles; a distally notched (forked) tongue associated with enhanced vomeronasal chemoreception; and modifications to the middorsal scale row, reflecting adaptations in integumentary shedding.[7] Cranial synapomorphies encompass streptostyly, wherein the quadrate articulates loosely with the skull for increased gape and kineticism, along with specific reductions in temporal bars and dental attachments (pleurodont or acrodont).[8] Postcranially, lepidosaurs exhibit symmetrical metacarpals, facilitating flexible manus mobility, and caudal vertebrae with prezygapophyseal-zygapophyseal fracture planes enabling autotomy for predator escape.[8] The epidermis features overlapping keratinous scales shed cyclically via ecdysis, a process mediated by beta-keratin layers unique to squamates among extant reptiles, though shared ancestrally in the clade.[4] These characteristics, supported by over 35 morphological synapomorphies in analyses uniting Sphenodon and squamates exclusive of other amniotes, underscore Lepidosauria's monophyly despite secondary losses in derived lineages like snakes (e.g., limbs).[7] Such traits reflect adaptations for terrestrial locomotion, sensory acuity, and defensive strategies, with fossil evidence confirming their Triassic origins around 240 million years ago.[3] Variations exist, as rhynchocephalians retain acrodont dentition and less pronounced kinesis compared to the pleurodont, highly kinetic skulls of squamates.[9]Major Clades and Relationships

Lepidosauria comprises two extant clades: Sphenodontia (also known as Rhynchocephalia), represented solely by the tuatara genus Sphenodon with two living species (S. punctatus and S. guntheri), and Squamata, which includes all lizards, snakes, and amphisbaenians and accounts for over 11,000 species.[1][10][7] Sphenodontia forms the sister group to Squamata, with the divergence dated to the Early Triassic at a minimum of 245–241 million years ago based on fossil evidence from jaw material assigned to early rhynchocephalians.[1] This basal split reflects the deep phylogenetic division within Lepidosauria, where Sphenodontia retains plesiomorphic traits such as acrodont dentition and a more rigid skull, contrasting with the derived cranial kinesis in Squamata.[3] Squamata exhibits greater diversity and adaptive radiation, with internal relationships resolved through integrated molecular and morphological phylogenies. A landmark 2013 analysis of 4161 species using sequence data from multiple genes supported the monophyly of major groups including Iguania, Gekkota, Scincomorpha, Anguimorpha, Serpentes, and Amphisbaenia, while recovering Amphisbaenia as sister to Lacertiformes (a lacertoform subgroup) and placing Dibamidae basally.[11] Subsequent studies, such as a 2021 supertree incorporating fossil and extant taxa, position Gekkota as the earliest diverging crown squamate clade, followed by a polytomy resolving into iguanians and scleroglossans (the latter encompassing anguiomorphs, scincomorphs, snakes, and amphisbaenians).[12] A 2023 genomic review reinforces this topology, with Dibamia or Gekkota near the base, succeeded by Scincoidea and then derived lineages like Toxicofera (a debated clade uniting Anguimorpha, Iguania, and Serpentes via shared toxin-delivery traits, though not universally supported in morphological datasets).[13] Key squamate clades include:- Gekkota: Approximately 1,800 species of geckos, flap-footed lizards, and blind lizards, characterized by adhesive toe pads in many taxa and nocturnal habits; basal position supported across molecular phylogenies.[11][12]

- Iguania: Encompassing iguanas, chameleons, and agamids (~1,900 species), unified by tongue-based prey capture and often diurnal, arboreal lifestyles; sister to scleroglossans in recent trees.[11]

- Scincomorpha: Includes skinks, whiptails, and lacertids (~6,000 species), featuring diverse limb reductions and burrowing adaptations; forms a clade with anguimorphs and snakes in combined analyses.[11][13]

- Anguimorpha: Monitor lizards, glass lizards, and allies (~200 species), notable for forked tongues and predatory ecology; closely related to snakes within scleroglossans.[11]

- Serpentes: Snakes (~3,900 species), derived from lizard-like ancestors with limblessness and specialized jaw mechanics for ingestion; nested within Squamata, often sister to anguimorphs or amphisbaenians.[11][6]

- Amphisbaenia: Worm lizards (~200 species), fossorial specialists with reduced eyes and elongated bodies; phylogeny places them near lacertids or as part of a broader scleroglossan radiation.[11]

Taxonomic Debates and Controversies

The Toxicofera hypothesis, advanced in 2005, proposes that a clade comprising Iguania, Anguimorpha, and Serpentes shares a common origin of venom-delivery systems, challenging traditional morphological classifications that positioned Iguania as the basal squamate group and separated snakes from lizards.[15] This view gained traction through molecular phylogenies, with genomic-scale analyses recovering strong support for Toxicofera monophyly and rejecting alternatives like Scleroglossa.[16] Critics, however, contend that the hypothesis overinterprets homologous oral glands as a unified venom system in varanid lizards and disrupts established macroevolutionary trends in squamate morphology derived from extensive fossil and anatomical data. Integrated morphological-molecular studies have mitigated some conflicts by favoring Toxicofera but highlight biases in datasets, such as underweighting morphological characters from fossils, underscoring ongoing tensions in resolving squamate deep phylogeny.[17] Placement of early Mesozoic fossils remains contentious, particularly for taxa like Paliguana whitei from the Early Triassic Cynognathus Assemblage Zone of South Africa, described in 1920 and long debated for its potential as the earliest lepidosaur due to features like diapsid skull fenestration.[18] Reassessments using computed tomography have rejected lepidosaurian affinities, instead positioning Paliguana as a basal lepidosauromorph or more distant stem diapsid, thereby excluding it from crown-group Lepidosauria (Rhynchocephalia + Squamata) and preserving a Triassic rather than Permian origin for the clade.[18] Such revisions address discrepancies between sparse, incomplete fossils—often leading to misassignments—and molecular clock estimates, with recent discoveries like Agriodon (Agriodontosaurus) from the earliest Triassic (ca. 245–241 Ma) confirming the Rhynchocephalia-Pan-Squamata split within crown Lepidosauria and resolving prior uncertainties from fragmentary material.[1] These debates extend to stem lepidosaurs, where poor preservation and limited taxa hinder robust phylogenies, complicating divergence timing and character evolution; for instance, eolacertilians like Paliguana were once invoked to push lepidosaur origins earlier but now illustrate the risks of overinterpreting isolated elements without comprehensive comparative anatomy.[18] While molecular data dominate resolutions within living Squamata, fossil-inclusive analyses emphasize the need for denser sampling to integrate extinct branches, such as enigmatic Jurassic forms, avoiding overreliance on extant taxa that may obscure total-group diversity.[1]Evolutionary History

Triassic Origins and Stem Lepidosaurs

The origins of Lepidosauria, the clade encompassing squamates (lizards and snakes) and rhynchocephalians (tuatara and relatives), are rooted in the Triassic period (252–201 million years ago), with integrated molecular clock estimates and fossil discoveries converging on an initial divergence during the Early to Middle Triassic.[3] This timeline challenges prior molecular hypotheses placing the origin in the Permian, as the earliest unambiguous fossils appear in Middle Triassic strata, indicating rapid post-Permian-Triassic extinction diversification among sauropsids.[3] Basal lepidosaurs likely evolved in terrestrial environments amid recovering ecosystems, exhibiting primitive traits such as acrodont dentition precursors and flexible skulls adapted for insectivory.[19] The oldest known crown lepidosaur is Agriodontosaurus schultzei, unearthed from the Middle Triassic (~245 million years ago) Otter Sandstone Formation in Devon, United Kingdom, preserving a partial skeleton with specialized cranial features like pleurodont teeth and a reinforced palate suggestive of early adaptations for grasping prey.[1] This specimen, approximately 7 million years older than prior records, confirms lepidosaur presence by the Anisian stage (247–242 million years ago) and reveals mosaic evolution in feeding mechanics, including robust jaw mechanics absent in some later forms.[1] Concurrently, a diminutive (~2 cm skull) stem-lepidosauromorph from the Middle Triassic Vellberg locality in Germany highlights pre-crown experimentation with elongate bodies and reduced limb girdles, bridging earlier kuehneosaurids to true lepidosaurs.[20] Stem lepidosaurs, positioned outside the crown but within the total group, are exemplified by Taytalura alcoberi from the Late Triassic (~231 million years ago) Ischigualasto Formation in Argentina, a three-dimensionally preserved skull displaying plesiomorphic traits like unfused frontals and a broad quadrate that prefigure sphenodontian architecture while lacking derived squamate specializations.[19] This taxon suggests stem forms retained generalized lizard-like morphologies, with features such as multiple infralabial foramina and a streptostylic quadrate facilitating early cranial kinesis.[19] Additional Middle Triassic evidence includes a basal rhynchocephalian from Vellberg, Germany (~240 million years ago), the earliest definitive member of that subclade, featuring acrodont marginal teeth and a complete temporal bar indicative of the clade's antiquity.[3] These fossils collectively document a Triassic stem-to-crown transition marked by incremental refinements in dentition and skull modularity, predating the Jurassic dominance of squamates.[3]Mesozoic Diversification

During the Jurassic, Squamata exhibited an initial morphological radiation, with disparity in form increasing markedly from approximately 174 to 145 million years ago, establishing diverse ecological niches that foreshadowed their later dominance.[21] This diversification contrasted with the earlier Mesozoic prominence of Rhynchocephalia, which had been the more speciose lepidosaur clade through the Triassic and into the Early Jurassic, occupying varied habitats alongside dinosaurs.[22] Fossil evidence indicates rhynchocephalians achieved peak diversity during this era, with multiple genera documented in Laurasian and Gondwanan deposits, though sampling biases may inflate perceived early abundances.[23] In the Cretaceous, squamate evolution accelerated, with ecomorphological disparity expanding between 110 and 90 million years ago, driven by adaptations in locomotion, diet, and habitat use that preceded a surge in taxonomic diversity around 84 million years ago.[24] Lizards and snakes underwent a pronounced radiation, yielding stem-group representatives of major extant lineages, while rhynchocephalians persisted but began showing signs of relative decline in diversity compared to their Jurassic peak.[25] Unequivocal snake fossils emerge in Early Cretaceous strata (circa 130–100 million years ago), suggesting a possible Gondwanan origin based on their initial distributional patterns.[23] This Mesozoic trajectory reflects a gradual shift in lepidosaurian success, from rhynchocephalian-led assemblages in the Jurassic to squamate predominance by the Late Cretaceous, influenced by environmental opportunities and competitive dynamics, though end-Cretaceous extinction patterns spared both clades disproportionately relative to other reptiles.[3] Phylogenetic analyses integrating molecular clocks and fossils support crown-group squamates originating no later than the Middle Jurassic, enabling their adaptive radiation amid fluctuating continental configurations and climates.[14]Cenozoic Patterns and Recent Fossil Discoveries

Following the Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) boundary mass extinction approximately 66 million years ago, squamates within Lepidosauria experienced an 83% species-level extinction, eliminating many lineages such as polyglyphanodontians and reducing morphological disparity dramatically.[25] Surviving squamates, however, underwent selective recovery, with post-extinction assemblages in North America, such as those from the Denver Formation (ca. 128 kyr after the boundary), showing lower diversity but ecosystem restructuring toward modern-like configurations dominated by smaller-bodied forms.[26] This led to a prolonged radiation through the Paleogene and Neogene, marked by ecomorphological expansions in dietary modes, locomotion, and habitat use, culminating in over 11,000 extant species by integrating conserved cranial architectures with adaptive innovations.[14] [27] Rhynchocephalians, in contrast, displayed a stark decline in the Cenozoic, with fossil records becoming sparse after the Mesozoic; global distribution achieved by the Early Jurassic gave way to relictual Gondwanan persistence, evidenced by rare Paleogene finds like a younger species of Kawasphenodon from Patagonia (ca. 60–55 Ma), the only unambiguous post-K–Pg South American representative.[28] Cenozoic rhynchocephalians are limited to isolated jaws, such as sphenodontine dentition from the Early Miocene Manuherikia Group of New Zealand (19–16 Ma) closely resembling the extant tuatara Sphenodon punctatus, indicating continuity in dentary morphology but no broader diversification.[29] Higher evolutionary rates in body size for rhynchocephalians relative to squamates underscore their failure to rebound, contrasting with squamate success and contributing to the clade's near-extinction outside New Zealand.[30] Recent fossil analyses have refined Cenozoic patterns, including a 2025 study of Denver Basin squamates documenting pre- (ca. 57 kyr before) and post-K–Pg faunas, revealing selective survivorship favoring certain ecomorphs and early signs of recovery amid ecosystem upheaval.[26] For snakes, molecular and fossil integration links crown-group diversification to post-K–Pg colonization of Asia, driving clade expansions like Alethinophidia.[31] Rhynchocephalian Cenozoic discoveries remain incremental, with no major new taxa reported since 2014, emphasizing their marginal role compared to Mesozoic abundance.[28] These findings highlight causal drivers like niche vacancy post-extinction favoring squamate adaptability over rhynchocephalian conservatism.[23]Morphology and Anatomy

Cranial and Dental Features

Lepidosaurs exhibit diapsid skulls with two temporal fenestrae, often reduced or modified through evolutionary bone loss and gain patterns that facilitate cranial kinesis.[32] The streptostylic condition, where the quadrate articulates loosely with the squamosal, allows anteroposterior swinging to increase gape during feeding.[33] In Squamata, this is enhanced by mesokinetic and metakinetic joints, enabling dorsal flexion of the snout and posterior skull regions for greater kinetic flexibility compared to the more rigid cranium of Rhynchocephalia.[33] [34] Rhynchocephalians, exemplified by Sphenodon, retain primitive features such as a large postorbital area, high parietal table, and a jaw joint positioned below the tooth row, supporting durophagous feeding on hard prey.[35] Squamate skulls show disparate morphology, with frequent reductions in elements like the supratemporal and tabular bones, adapting to diverse ecologies from burrowing to aerial predation.[36] [27] Dentition in Lepidosauria is homodont and polyphyodont, with continuous replacement, but implantation varies phylogenetically.[37] Pleurodonty, where teeth attach to the medial jaw surface with shallow roots, represents the plesiomorphic condition across Lepidosauria.[38] Acrodonty, with teeth fused directly to the jaw apices, evolved in Rhynchocephalia, featuring enlarged palatine tooth rows and posteriorly extended dentaries for shearing vegetation or crushing invertebrates. Squamates retain pleurodont teeth, often with labial flanges and variable crown shapes reflecting dietary shifts, such as conical for piercing or multicuspid for grinding.[37] [39] Enamel is typically thin and prismatic, with microwear textures distinguishing diets: shallow furrows in carnivores versus deep, rough features in herbivores or molluscivores.[40] [41]Postcranial Skeleton

The postcranial skeleton of lepidosaurs encompasses the axial components, including the vertebral column and associated ribs, as well as the appendicular elements comprising the pectoral and pelvic girdles and limbs. The vertebral column exhibits regional differentiation into cervical, dorsal (or thoracic), sacral, and caudal series, with total presacral counts typically ranging from 25 to 30 in rhynchocephalians and basal squamates, though greatly expanded in elongate forms like snakes. Vertebral centra in Rhynchocephalia are amphicoelous or nearly cylindrical without a pronounced posterior condyle, reflecting a more primitive condition, whereas Squamata display procoelous centra with a concave anterior cotyle and convex posterior ball-and-socket articulation, enhancing flexibility in locomotion. Squamate vertebrae additionally feature zygosphene-zygantrum articulations on the neural arches, interlocking adjacent vertebrae for lateral stability absent in rhynchocephalians.[42][43][42] Ribs in lepidosaurs are bicephalic, articulating via capitulum to the centrum and tuberculum to the diapophysis, and extend along the trunk to support the body wall; in snakes and elongate lizards, they form an expansive ventral basket enclosing viscera. Rhynchocephalians retain gastralia (abdominal ribs) along the ventral midline, a plesiomorphic trait lost in squamates. The pectoral girdle consists of a robust scapulocoracoid, clavicles, and interclavicle, with the coracoid remaining unfused to the scapula in adults, facilitating limb mobility. The pelvic girdle features three ossified elements—ilium, ischium, and pubis—articulating with elongated sacral ribs, though fusion occurs in some derived squamates.[44][45][46] Appendicular skeletons in lepidosaurs are pentadactyl in basal forms, with symmetrical metacarpals and metatarsals as a lepidosaurian synapomorphy, but show extensive reduction in squamates adapted to fossorial, aquatic, or serpentine lifestyles. Limb reduction proceeds proximo-distally, often retaining proximal elements like humerus or femur while losing digits or distal segments, as seen in amphisbaenians and snakes where vestigial girdles persist internally. In limbed taxa, forelimbs support digging or climbing via elongated phalanges, while hindlimbs may elongate for jumping in forms like basilisks. These variations correlate with ecological shifts, with limb loss linked to vertebral elongation rather than simple homology.[8][47][48]Integumentary System

The integument of lepidosaurs consists of a multi-layered epidermis overlying a dermis composed of collagen fibers and elastic components, adapted for protection, water retention, and flexibility. The epidermis features an outer beta-layer rich in beta-keratins, which are cysteine-rich proteins unique to sauropsids and forming thin filaments (3-4 nm in diameter) that provide hardness and resistance to abrasion in scales, claws, and scutes.[49] [50] Alpha-keratins, intermediate filament proteins, predominate in the softer, living layers beneath, supporting structural integrity during epidermal cycling.[51] Lepidosaurian scales are epidermal derivatives, typically imbricate and keratinized, differing from the bony scutes of crocodilians or turtles by being fully shed during renewal. The epidermis renews cyclically via a shedding complex, where a shedding plane separates the outer (shed) and inner (retained) epidermal generations, facilitating ecdysis for growth, repair, and parasite removal.[52] In squamates, ecdysis occurs periodically—annually or more frequently depending on species, size, and conditions—with snakes often shedding the entire integument as a transparent "spectacle" over eyes and opaque skin elsewhere, while lizards shed in irregular patches.[53] Rhynchocephalians, such as the tuatara, lack such synchronized whole-body shedding, instead sloughing granular, beaded scales in fragments irregularly, reflecting a more primitive retention pattern.[54] Certain squamates, particularly anguids and cordylids, incorporate osteoderms—dermal bones of calcium phosphate embedded within or beneath scales—forming a protective armor that integrates skeletal and integumentary systems, though absent in snakes and rhynchocephalians.[55] Glands are sparse compared to amphibians, limited to precloacal or femoral pores in some lizards secreting waxy lipids for pheromones or lubrication, with minimal mucous glands aiding minor hydration.[56] Coloration arises from dermal chromatophores (iridophores, melanophores) interacting with overlying keratin, enabling camouflage and signaling without the photonic structures seen in some archosaurs.[52]Physiology

Thermoregulation and Energetics

Lepidosaurs, comprising squamates and the tuatara, are ectothermic vertebrates that derive body heat primarily from environmental sources rather than endogenous production.[57] They achieve thermoregulation mainly through behavioral adjustments, such as shuttling between sun-exposed basking sites and shaded retreats to elevate or lower body temperature (Tb) toward species-specific optima.[58] Physiological mechanisms, including limited vasodilation or vasoconstriction and color change in some lizards, provide supplementary control but are secondary to behavior.[59] Field studies of active squamates reveal Tb often ranging from 25–40°C, influenced by operative environmental temperatures, habitat structure, and predation risks, with deviations from preferred Tb signaling thermoregulatory constraints.[60] [61] In squamates, thermal sensitivity shapes performance traits like locomotion and digestion, following a thermal performance curve where rates peak at optimal Tb before declining at extremes.[62] Lizards from colder habitats may acclimate to select higher Tb, countering latitudinal gradients via plasticity.[59] Snakes exhibit similar patterns but with greater reliance on postprandial thermoregulation to accelerate digestion, often seeking warmer microhabitats after feeding.[63] The tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus), adapted to cooler New Zealand climates, selects lower Tb (typically 15–25°C) and shows behavioral avoidance of high temperatures exceeding 28°C, limiting activity in warmer conditions.[64] [65] Unlike many squamates, tuatara display reduced evaporative water loss at elevated temperatures, aiding persistence in mesic environments but constraining metabolic acceleration.[66] Energetics in lepidosaurs reflect ectothermy's efficiency, with resting or standard metabolic rates (SMR) scaling allometrically to body mass (explaining ~92% of variance in squamates) and increasing exponentially with Tb via Q10 effects (typically 2–3-fold per 10°C rise).[67] [68] Squamate SMR is lower than endotherms, enabling intermittent foraging and prolonged fasting—e.g., some snakes survive months without prey—while daily energy expenditure remains modest (often <10% of endotherm equivalents).[2] Tuatara exhibit comparably low SMR, with juveniles showing higher rates than mass-predicted at 13–18°C but adults aligning with reptilian baselines at 30°C (55% of expected for similar-sized lizards).[64] [69] These traits impose trade-offs: optimal Tb boosts foraging efficiency but elevates predation risk, while suboptimal Tb reduces growth and reproduction, as evidenced by countergradient variation in developmental metabolism across populations.[70] [63] Overall, low energetic demands facilitate high abundance in diverse habitats but render lepidosaurs vulnerable to thermal mismatches from climate shifts.[71]Reproduction and Life History

Lepidosaurs exhibit internal fertilization, with squamates possessing paired hemipenes and rhynchocephalians achieving it via cloacal apposition.[72] Reproductive modes are predominantly oviparous across the clade, though squamates display remarkable diversity, including over 100 independent evolutionary transitions to viviparity and approximately 40 origins of obligate parthenogenesis, making them the only vertebrates with true parthenogenetic reproduction.[73][74] Viviparity in squamates often correlates with cooler climates but does not significantly alter offspring numbers or sizes compared to oviparity.[75][76] Parthenogenesis typically arises via interspecific hybridization and is facultative in some species, such as certain boas and Komodo dragons, but obligate forms predominate in lineages like whiptail lizards, often leading to reduced genetic diversity and higher extinction risks.[77][78] In squamates, oviparous species lay clutches averaging 2–10 eggs in lizards and 6–15 in snakes, with larger clutches associated with higher latitudes, greater productivity, and seasonality; insular taxa tend toward smaller clutches.[79][80] Many females store sperm post-insemination, enabling delayed fertilization and multiple clutches from one mating.[81] Viviparous forms retain eggs until hatching within the oviduct, with evolutionary losses of eggshell calcification marking the shift from oviparity.[82] Rhynchocephalians, represented solely by tuatara (Sphenodon spp.), are strictly oviparous, with females producing 6–10 eggs per clutch after 1–3 years of yolk accumulation and up to 7 months of shell formation; eggs are laid in burrows and incubated for 12–16 months, with embryonic development arresting during winter.[83] Incubation duration is temperature-dependent, ranging from 150 days at 25°C to 328 days at 18°C, influencing hatchling sex via temperature-dependent determination.[84] Life history traits in lepidosaurs scale similarly with adult body mass across lizards, snakes, and tuatara, reflecting ectothermic constraints on growth and reproduction.[85] Squamates generally reach sexual maturity in 1–3 years, reproduce annually or biennially, and exhibit lifespans from a few years in small species to decades in larger ones, with iteroparity common except in semelparous forms like some blindsnakes. Tuatara mature slowly, at 10–20 years, with females breeding every 2–5 years and males annually thereafter; longevity exceeds 100 years, contributing to low population growth rates despite stable clutch sizes uncorrelated with female body size in some populations.[86] These traits underscore lepidosaurs' adaptation to variable environments, with squamate flexibility contrasting tuatara conservatism.Sensory and Neural Adaptations

Lepidosaurs display diverse sensory adaptations reflecting their ecological niches, with Squamata showing greater variation than the more conservative Rhynchocephalia. Vision in diurnal lizards often includes tetrachromatic color perception via four cone types, enabling discrimination of ultraviolet and longer wavelengths, whereas snakes typically possess dichromatic vision with reduced acuity suited to low-light hunting.[87] Olfaction is prominent across the clade, supported by expanded vomeronasal organs for detecting pheromones and environmental volatiles, with snakes exhibiting particularly extensive olfactory epithelia and receptor gene repertoires that vary by foraging mode—higher in active foragers like varanids.[88] Auditory systems are structurally heterogeneous; lizards and tuatara retain tympanic middle ears sensitive to airborne sounds up to 6-7 kHz, while snakes have lost external ears and rely on quadrate-jaw conduction for substrate-borne vibrations below 1 kHz.[89][90] Thermoreception represents a specialized sensory innovation in certain squamates, absent in rhynchocephalians. Pit organs in crotaline vipers and boid pythons consist of facial pits housing infrared-sensitive membranes with TRPA1 ion channels that detect thermal contrasts as low as 0.001°C, integrating with visual tectal pathways to form multimodal prey-tracking maps effective at distances up to 1 meter in darkness.[91] This system evolved convergently in these lineages, with pit membrane neurons projecting to the accessory optic tectum for sub-millisecond temporal resolution.[92] The tuatara uniquely retains a functional parietal eye, a dorsally positioned photoreceptive organ with melanopsin-expressing cells that modulates circadian and thermoregulatory responses to photoperiod changes, though lacking image-forming capability.[93] Neural adaptations underpin these sensory capabilities, with lepidosaur brains featuring proportionally large optic tecta for visuomotor integration and elongated olfactory tracts in scent-reliant species. Endocasts reveal clade-wide encephalization quotients below 0.5 relative to body mass, but with rhynchocephalians showing modest pallial expansion for associative processing compared to the tectal dominance in squamates.[94] [95] Snakes exhibit neural modifications including hypertrophied vomeronasal projections and trigeminal pathways channeling infrared signals, enabling bimodal sensory fusion without dedicated cortical areas.[95] Inner ear labyrinth diversity correlates with auditory sensitivity, with elongated semicircular canals in agile climbers enhancing vestibular input to cerebellar circuits.[94] These traits, conserved from Triassic ancestors, facilitate rapid behavioral responses in varied habitats.[1]Ecology and Behavior

Habitat Utilization and Distribution

Lepidosaurs, dominated by Squamata with over 11,000 species, achieve a near-cosmopolitan distribution across all continents except Antarctica, extending into marine habitats via fully aquatic sea snakes and semi-aquatic sea kraits.[23] [2] This broad range reflects adaptations to varied thermal regimes, from temperate zones with viviparous species in high latitudes to equatorial tropics, though polar extremes limit presence due to ectothermy constraints.[22] Squamates exploit diverse microhabitats, including terrestrial ground-dwellers, arboreal climbers, fossorial burrowers like amphisbaenians, and saxicolous forms on rocky outcrops, with habitat selection driven by foraging mode, predation avoidance, and thermoregulation needs.[7] For instance, many lizards favor sun-exposed rocks or vegetation for basking, while snakes often utilize leaf litter or soil for ambush predation, enabling coexistence through niche partitioning in shared ecosystems.[96] Aquatic forms, such as hydrophiine sea snakes, are confined to warm coastal and coral reef waters of the Indo-Pacific, totaling around 60 species specialized for underwater lung ventilation and prey capture.[2] In contrast, Rhynchocephalia persists only in the tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus), endemic to 32 offshore islands around New Zealand, where populations occupy coastal forests, scrublands, and burrows shared with seabirds for thermoregulatory benefits.[97] Tuatara prefer cool, humid microclimates with burrow temperatures averaging 16–20°C and humidity near 80%, avoiding mainland habitats due to historical competition and predation post-human arrival.[98] This restricted distribution underscores their relictual status, with fossils indicating former Gondwanan-wide presence before isolation and extinction pressures reduced range.[99]Foraging and Diet

Lepidosaurs employ diverse foraging strategies, including sit-and-wait ambush predation and active wide foraging, which are phylogenetically conserved within many squamate families and linked to prey detection via chemical cues.[100] Diets across Lepidosauria are predominantly carnivorous, focusing on arthropods, small vertebrates, and invertebrates, though some lizard lineages have incorporated plant material, influencing jaw morphology evolution.[101] In Squamata, approximately 81.7% of lizards with known diets are carnivorous, while all snakes and amphisbaenians are obligate carnivores; herbivory occurs mainly in specific iguana-like groups.[102] Snakes exhibit an evolutionary expansion in dietary breadth originating over 150 million years ago, enabling consumption of larger, more varied prey relative to body size compared to lizards.[103] Lizard foraging alternates with thermoregulation in many species, such as teiid lizards that bask before actively searching for mobile invertebrate prey.[4] Snakes often use ambush tactics but include active hunters, with food transport involving inertial feeding via cranio-cervical movements in active foragers like varanids.[104] Dietary specialization correlates with cranial adaptations, where durophagous taxa process harder prey like beetles through enhanced shearing mechanics.[105] Rhynchocephalians, represented by tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus), are selective nocturnal predators foraging primarily around burrows, consuming mainly large insects such as beetles (Coleoptera), spiders (Araneae), and wētā (Orthoptera).[106] Their diet varies seasonally and by habitat, shifting to seabird eggs and chicks (e.g., fairy prions) in late spring and summer, with occasional predation on lizards, frogs, or conspecifics; larger individuals access higher trophic levels including vertebrates.[107][108] Tuatara gape size and fat stores increase with body size, facilitating predation on larger, more profitable prey.[109]Defensive Mechanisms and Predation

Lepidosaurs exhibit a range of morphological and behavioral defenses against predators, with caudal autotomy being a key adaptation in many lizards and the tuatara, enabling voluntary tail detachment at specialized fracture planes to divert attacks and facilitate escape, followed by regeneration over weeks to months.[110][111] This strategy incurs costs such as reduced locomotor performance, fat reserves, and future escape efficacy until regrowth completes.[112] Embedded osteoderms in the scales of anguid, cordylid, and teiid lizards form bony armor that resists penetration by predator teeth or claws, though their defensive role may vary with species-specific thickness and distribution.[55] Snakes, lacking autotomizable tails, primarily use behavioral displays for deterrence, including body coiling, head triangulation to mimic venomous species, hissing, cloacal popping, and rapid bluff strikes without biting.[113][114] Cryptic coloration, immobility, and thanatosis (feigning death) serve as passive defenses across lepidosaurs, minimizing detection by visual predators like birds and mammals.[115] Chemical repellents from cloacal glands, producing foul-smelling liquid or solid discharges, occur in tropidurids and some colubrids, deterring close-range threats through taste and odor aversion.[116] Predation strategies in lepidosaurs reflect ecological niches, with most species being sit-and-wait or active foragers targeting invertebrates, small vertebrates, and eggs. Lizards often lunge to seize prey with jaws, employing lateral head shaking to subdue struggling items like insects or rodents before swallowing.[117] Advanced snakes (Caenophidia) inject complex proteinaceous venoms via specialized fangs to rapidly immobilize prey through neurotoxicity, hemotoxicity, or myotoxicity, enabling consumption of vertebrates larger than their heads.[117] Basal snakes like boas and pythons rely on constriction, coiling to exert increasing pressure that disrupts circulation and respiration, as documented in over 100 prey types for Boa constrictor alone.[118] Tuatara are selective nocturnal predators, using acrodont teeth for crushing exoskeletons of large insects, seabird eggs, and juvenile lizards, with seasonal shifts toward more vertebrate prey in summer.[106] Venom in toxicoferans evolved primarily for efficient prey subjugation but provides secondary defense via envenomation-induced pain.[119]Diversity and Biogeography

Squamata Radiation

Squamata, encompassing lizards, snakes, and amphisbaenians, represents the predominant radiation within Lepidosauria, accounting for over 11,700 extant species and comprising the largest clade of terrestrial vertebrates.[120] This diversity vastly exceeds that of the sole surviving rhynchocephalian genus Sphenodon, highlighting Squamata's exceptional evolutionary success.[12] The clade's global distribution spans all continents except Antarctica, facilitated by adaptations to terrestrial, arboreal, fossorial, and aquatic habitats.[24] The origins of Squamata trace to the Middle Triassic approximately 242 million years ago, with stem-group forms diverging from rhynchocephalians earlier in the Triassic around 250 million years ago.[12] Fossil records remain sparse through the Triassic to Early Cretaceous (252–100 Ma), but phylogenetic analyses indicate an initial morphological radiation in the Middle to Late Jurassic (174–145 Ma), marked by the emergence of major modern lineages such as iguanians, gekkotans, and scleroglossans.[21] This Jurassic phase involved elevated evolutionary rates in cranial elements, particularly the frontal bone, driving early ecomorphological divergence.[27] Diversification accelerated during the Cretaceous, coinciding with the Cretaceous Terrestrial Revolution around 100 million years ago, when angiosperm dominance and insect diversification expanded ecological opportunities.[121] Ecomorphological expansion in this period included adaptations for varied locomotion, such as limb reduction in snakes and amphisbaenians, and specialized feeding mechanisms, including the streptostylic skull enabling kinetic jaw movement.[24] [14] Post-Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction events further propelled species richness, with snakes exhibiting a macroevolutionary singularity in dietary breadth originating over 150 million years ago.[103] These innovations, combined with high speciation rates in lineages like gekkotans and colubroid snakes, underpin Squamata's dominance, though rates vary phylogenetically with some clades showing stasis.[122]Rhynchocephalia Persistence

Rhynchocephalia, a lineage of lepidosaurs sister to Squamata, exhibited substantial diversity during the Triassic and Jurassic periods, with fossil records documenting over 20 genera across Laurasia and Gondwana, including forms adapted to terrestrial, aquatic, and arboreal niches.[123][124] This radiation peaked in the Mesozoic, but by the Early Cretaceous, the group began a marked decline, with most Laurasian taxa vanishing from the fossil record, potentially due to competitive exclusion by the rapidly diversifying Squamata, which occupied overlapping ecological roles with greater adaptability and higher evolutionary rates in certain traits.[125][126] In Gondwanan regions, rhynchocephalians persisted longer, with lineages surviving into the Paleogene, as evidenced by fossils from South America indicating post-K-Pg (66 million years ago) endurance before regional extinctions.[28] The persistence of Rhynchocephalia through the Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction event, which eradicated non-avian dinosaurs and many other reptile groups, underscores their resilience, with Sphenodon-like forms documented in Paleocene deposits, contrasting the broader lepidosaur faunal turnover.[28][127] Survival likely stemmed from conservative life-history strategies, including ectothermy suited to stable, temperate environments, protracted longevity (up to 100 years or more in extant tuatara), and low metabolic demands that buffered against resource scarcity post-extinction.[128] These traits, coupled with dietary flexibility (omnivory including invertebrates and vegetation) and burrowing behaviors, enabled niche retention in insular or refugial habitats less impacted by immediate post-K-Pg ecological disruptions.[129] Biogeographic isolation played a pivotal role in long-term persistence, particularly for the extant genus Sphenodon (tuatara), confined to offshore islands of New Zealand where mammalian competitors and predators were absent until human arrival around 1280 CE.[130] This Gondwanan refugium, separated since the Late Cretaceous, precluded the intense biotic pressures—such as squamate competition and mammalian predation—that drove continental extinctions, as seen in Miocene South American records marking the group's final Gondwanan decline outside New Zealand.[29][131] Morphological stasis in Sphenodon, with skeletal features resembling Jurassic ancestors, further facilitated endurance in low-disturbance settings, though fossil cranial variation challenges a strict "living fossil" designation by revealing adaptive disparity in extinct relatives.[131] Today, Sphenodon punctatus and the closely related S. guntheri represent the sole surviving rhynchocephalians, with populations numbering approximately 55,000–70,000 individuals across 32 islands, sustained by traits like temperature-dependent sex determination and delayed sexual maturity (up to 20 years).[128] Their persistence highlights how evolutionary conservatism and geographic vicariance can preserve ancient lineages amid clade-wide attrition, though ongoing threats from habitat alteration and invasive species underscore vulnerability in this relict taxon.[130]Global Patterns and Endemism

Squamates, the dominant clade within Lepidosauria, exhibit a nearly cosmopolitan distribution across all continents except Antarctica, extending to numerous oceanic islands, while rhynchocephalians are restricted to offshore islands of New Zealand.[132][133] This disparity underscores the extensive radiation of squamates, which comprise over 11,000 species, contrasting with the single extant rhynchocephalian genus Sphenodon.[134] Global patterns of lepidosaur diversity reveal peaks in tropical and subtropical latitudes, with major hotspots in the Indo-Malayan region, Australasia, Madagascar, sub-Saharan Africa, and the Neotropics, influenced by historical vicariance from Gondwanan fragmentation and subsequent dispersal.[135] Biogeographic analyses identify 24 evolutionarily distinct bioregions for lepidosaurs, where boundaries often align with physical barriers such as oceans, mountain ranges, and deserts, shaping phylogenetic turnover and regional uniqueness.[136] Endemism in Lepidosauria is pronounced in isolated habitats, reflecting adaptive radiations and limited dispersal. Rhynchocephalians exemplify relictual endemism, with Sphenodon persisting only on approximately 30 New Zealand islands following historical extirpations on the mainland.[97] Among squamates, high levels of species and phylogenetic endemism occur in biodiversity hotspots; for instance, Madagascar harbors over 90% endemic reptiles, predominantly squamates like chameleons and geckos, while Australia features numerous endemic genera, particularly in skinks and agamids, comprising a significant portion of its ~800 lizard species.[137] Other centers include the Western Ghats with multiple endemic dwarf gecko lineages and the Cerrado biome, where ~40% of squamates are endemic, highlighting vicariant patterns driven by habitat fragmentation.[138][139] These patterns emphasize the role of geographic isolation in fostering lepidosaur diversity, with implications for conservation prioritizing endemic-rich areas.[140]Conservation and Anthropogenic Impacts

Primary Threats from Human Activity

Habitat destruction driven by agricultural expansion, urbanization, and logging constitutes the predominant anthropogenic threat to Lepidosauria, exacerbating extinction risks across Squamata and Rhynchocephalia. A comprehensive global evaluation of over 10,000 reptile species, including the vast majority of lepidosaurs, identifies these land-use changes as the primary drivers, with agriculture alone implicated in threats to 60% of evaluated species facing habitat loss. Forest-inhabiting lepidosaurs exhibit elevated vulnerability, with 30% classified as threatened compared to 14% in arid environments, reflecting the disproportionate impact on biodiverse tropical habitats where many squamate radiations occur.[141][141][141] Direct exploitation through hunting, commercial harvesting, and illegal wildlife trade further imperils lepidosaur populations, particularly snakes and lizards sought for skins, pets, and traditional uses. Annual global seizures by enforcement agencies exceed 4,000 live reptiles, including snakes, lizards, and related taxa, underscoring the scale of unregulated trafficking that depletes wild stocks and facilitates disease transmission. In regions like Africa and Asia, species such as girdled lizards and pythons face intense pressure from pet trade demand, often evading regulations via misdeclaration or captive-bred falsifications.[142][142] Introduced invasive species, facilitated by human transport and habitat alteration, amplify threats especially to insular lepidosaurs like the tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus), where rats, mice, and cats prey on juveniles and compete for resources. New Zealand's tuatara populations, confined to predator-free islands following mainland extirpation, remain susceptible to inadvertent invasions and poaching, with habitat modification compounding recovery challenges. For squamates in Australia, feral cats overlap with 70% of threatened species ranges, correlating with higher IUCN threat listings.[130][130][143]Population Trends and Vulnerability Assessments

Approximately 19.6% of the world's squamate species—encompassing over 10,000 lizards and snakes—are classified as threatened (Vulnerable, Endangered, or Critically Endangered) under IUCN Red List criteria, based on a comprehensive 2022 global reptile assessment involving assessments of 10,196 species.[141] This threat level is lower than for turtles (57.9%) or crocodilians (50%) but higher than the overall tetrapod average, with particular vulnerability in certain families such as iguanids (73.8% threatened) and certain island endemics affected by habitat fragmentation and invasive species.[144] Data deficiencies persist for many tropical and understudied species, potentially underestimating true extinction risks, as only about 4,000 squamates were formally assessed prior to 2015, covering roughly 70% of genera.[122] Global population trends for squamates remain poorly documented due to sparse long-term monitoring, with available time-series data biased toward temperate and charismatic taxa; nonetheless, the Living Planet Index indicates an average 54-55% decline in reptile populations from 1970 to 2012, though lizards and snakes comprise just 1-2% of monitored series, limiting generalizability to Lepidosauria.[145] Regional patterns show stability or increases in many mainland populations adapted to human-modified landscapes, contrasted by sharp declines on islands (e.g., 30% of forest-dwelling reptiles at risk versus 14% in arid habitats) driven by predation and land-use change.[146] Rhynchocephalia, represented solely by the two tuatara species (Sphenodon punctatus and S. guntheri), holds Least Concern status on the IUCN Red List as of recent evaluations, reflecting self-sustaining populations on predator-free islands and successful translocations.[147] However, vulnerability assessments highlight risks from low genetic diversity and climate sensitivity, with long-term monitoring on Brothers Island revealing a significant decline in body condition from 1949 to 2003, attributed to density-dependent factors and potential warming effects producing excess males.[148] Wild populations number in the tens of thousands but remain fragmented, with conservation reliant on invasive species control to prevent localized extinctions.[130]Management Approaches and Utilization

Management of Lepidosauria emphasizes habitat preservation, invasive species eradication, and population recovery via translocations and captive breeding to counter threats like habitat loss and predation. Global assessments identify priority areas for reptile conservation, integrating Lepidosauria into strategies prioritizing evolutionary distinctiveness and threat levels.[141] In New Zealand, tuatara recovery plans involve eradicating invasive mammals from offshore islands followed by reintroductions, boosting populations from remnant sites.[149] [150] Artificial incubation of eggs has sustained threatened tuatara groups, with programs achieving high hatch success over 18 years.[151] For Squamata, invasive species management targets introduced populations, such as green iguanas (Iguana iguana), through seasonal male-targeted removals and nocturnal trapping to prevent ecosystem disruption in Pacific islands.[152] [153] Spatial ecology data enhances control of invasive snakes on islands by optimizing patrol routes.[154] Captive breeding supports reintroductions for endangered lizards, with evidence reviews confirming efficacy in head-starting and release programs.[155] [156] Human utilization of Lepidosauria centers on Squamata for commercial purposes, regulated under CITES to mitigate overexploitation. Reptile skin trade, primarily from snakes and lizards, supplies leather goods, with historical volumes exceeding millions of skins annually from species like pythons and monitors.[157] [158] The pet trade drives demand for diverse Squamata, including monitors, contributing to wild harvests but also captive propagation in some cases.[159] Snake venoms are harvested for antivenom production, immunizing animals like horses to generate antibodies against envenomations responsible for over 100,000 annual deaths, and serve as sources for pharmaceuticals targeting cardiovascular conditions.[160] [161] Sustainable practices, including ranching, aim to balance utilization with population viability.[157]References

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Osteology_of_the_Reptiles/Chapter_2