Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Manatee

View on Wikipedia

| Manatees | |

|---|---|

| |

| West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Sirenia |

| Family: | Trichechidae |

| Subfamily: | Trichechinae |

| Genus: | Trichechus Linnaeus, 1758 |

| Type species | |

| Trichechus manatus Linnaeus, 1758

| |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

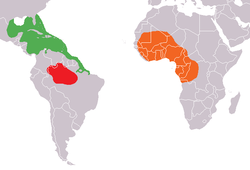

Manatees (/ˈmænətiːz/, family Trichechidae, genus Trichechus) are large, fully aquatic, mostly herbivorous marine mammals sometimes known as sea cows. There are three accepted living species of Trichechidae, representing three of the four living species in the order Sirenia: the Amazonian manatee (Trichechus inunguis), the West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus), and the West African manatee (Trichechus senegalensis). They measure up to 4.0 metres (13 ft 1 in) long, weigh as much as 590 kilograms (1,300 lb),[2] and have paddle-like tails.

Manatees are herbivores and eat over 60 different freshwater and saltwater plants. Manatees inhabit the shallow, marshy coastal areas and rivers of the Caribbean Sea, the Gulf of Mexico, the Amazon basin, and West Africa.

The main causes of death for manatees are human-related issues, such as habitat destruction and human objects. Their slow-moving, curious nature has led to violent collisions with propeller-driven boats and ships. Some manatees have been found with over 50 scars on them from propeller blades. Natural causes of death include adverse temperatures, predation by crocodiles on young, and disease.

Etymology

[edit]The etymology of the name is unclear, with connections having been made to Latin manus "hand" and to the term manaty "breast" from the Carib language of native South Americans.[3] The Carib term may refer to the mammary glands of the manatee, which are located on their chests under their armpits.[4][5] The term sea cow is a reference to the species' slow, peaceful, herbivorous nature, reminiscent of that of bovines.[6] Lamantin (from French lamantin) was commonly used as an alternative name until the 20th century.[7]

Taxonomy

[edit]Manatees are three of the four living species in the order Sirenia. The fourth is the Eastern Hemisphere's dugong. The Sirenia are thought to have evolved from four-legged land mammals more than 60 million years ago, with the closest living relatives being the Proboscidea (elephants) and Hyracoidea (hyraxes).[8]

Description

[edit]

Manatees weigh 400 to 550 kg (880 to 1,210 lb), and average 2.8 to 3.0 m (9 ft 2 in to 9 ft 10 in) in length, sometimes growing to 4.6 m (15 ft 1 in) and 1,775 kg (3,913 lb) and females tend to be larger and heavier than males. At birth, baby manatees weigh about 30 kg (66 lb) each. The female manatee has two teats, one under each flipper,[9] a characteristic that was used to make early links between the manatee and elephants.

The lids of manatees' small, widely spaced eyes close in a circular manner. The manatee has a large, flexible, prehensile upper lip, used to gather food and eat and for social interaction and communication. Manatees have shorter snouts than their fellow sirenians, the dugongs.

Manatee adults have no incisor or canine teeth, just a set of cheek teeth, which are not clearly differentiated into molars and premolars. These teeth are repeatedly replaced throughout life, with new teeth growing at the rear as older teeth fall out from farther forward in the mouth, somewhat as elephants' teeth do.[10][11] At any time, a manatee typically has no more than six teeth in each jaw of its mouth.[11]

The manatee's tail is paddle-shaped, and is the clearest visible difference between manatees and dugongs; a dugong tail is fluked, similar in shape to that of a whale.

The manatee is unusual among mammals in having just six cervical vertebrae,[12] a number that may be due to mutations in the homeotic genes.[13] All other mammals have seven cervical vertebrae,[14] other than the two-toed and three-toed sloths.

Like the horse, the manatee has a simple stomach, but a large cecum, in which it can digest tough plant matter. Generally, the intestines are about 45 meters, unusually long for an animal of the manatee's size.[15]

Evolution

[edit]Fossil remains of manatee ancestors - also known as sirenians - date back to the Early Eocene.[16][17] It is thought that they reached the isolated area of the South American continent and became known as Trichechidae. In the Late Miocene, trichechids were likely restricted in South American coastal rivers and they fed on many freshwater plants. Dugongs inhabited the West Atlantic and Caribbean waters and fed on seagrass meadows instead. As the sea grasses began to grow, manatees adapted to the changing environment by growing supernumerary molars. Sea levels lowered and increased erosion and silt runoff was caused by glaciation. This increased the tooth wear of the bottom-feeding manatees.[18]

Behavior

[edit]

Apart from mothers with their young, or males following a receptive female, manatees are generally solitary animals.[11] Manatees spend approximately 50% of the day sleeping submerged, surfacing for air regularly at intervals of less than 20 minutes. The remainder of the time is mostly spent grazing in shallow waters at depths of 1–2 m (3 ft 3 in – 6 ft 7 in). The Florida subspecies (T. m. latirostris) has been known to live up to 60 years.

Locomotion

[edit]Generally, manatees swim at about 5 to 8 km/h (3 to 5 mph). However, they have been known to swim at up to 30 km/h (20 mph) in short bursts.[19]

Intelligence and learning

[edit]

Manatees are capable of understanding discrimination tasks and show signs of complex associative learning. They also have good long-term memory.[20] They demonstrate discrimination and task-learning abilities similar to dolphins and pinnipeds in acoustic and visual studies.[21] Social interactions between manatees are highly complex and intricate, which may indicate higher intelligence than previously thought, although they remain poorly understood by science.[22]

Reproduction

[edit]Manatees typically breed once every two years; generally only a single calf is born. Gestation lasts about 12 months and to wean the calf takes a further 12 to 18 months,[11] although females may have more than one estrous cycle per year.[23]

Communication

[edit]Manatees emit a wide range of sounds used in communication, especially between cows and their calves.[24] Their ears are large internally but the external openings are small, and they are located four inches behind each eye.[25] Adults communicate to maintain contact and during sexual and play behaviors. Taste and smell, in addition to sight, sound, and touch, may also be forms of communication.[26]

Diet

[edit]Manatees are herbivores and eat over 60 different freshwater (e.g., floating hyacinth, pickerel weed, alligator weed, water lettuce, hydrilla, water celery, musk grass, mangrove leaves) and saltwater plants (e.g., sea grasses, shoal grass, manatee grass, turtle grass, widgeon grass, sea clover, and marine algae).[27][28] Using their divided upper lip, an adult manatee will commonly eat up to 10%–15% of their body weight (about 50 kg) per day. Consuming such an amount requires the manatee to graze for up to seven hours a day.[29] To be able to cope with the high levels of cellulose in their plant based diet, manatees utilize hindgut fermentation to help with the digestion process.[30] Manatees have been known to eat small numbers of fish from nets.[31]

Feeding behavior

[edit]

Manatees use their flippers to "walk" along the bottom whilst they dig for plants and roots in the substrate. When plants are detected, the flippers are used to scoop the vegetation toward the manatee's lips. The manatee has prehensile lips; the upper lip pad is split into left and right sides which can move independently. The lips use seven muscles to manipulate and tear at plants. Manatees use their lips and front flippers to move the plants into the mouth. The manatee does not have front teeth, however, behind the lips, on the roof of the mouth, there are dense, ridged pads. These horny ridges, and the manatee's lower jaw, tear through ingested plant material.[29]

Dentition

[edit]Manatees have four rows of teeth. There are 6 to 8 high-crowned, open-rooted molars located along each side of the upper and lower jaw giving a total of 24 to 32 flat, rough-textured teeth. Eating gritty vegetation abrades the teeth, particularly the enamel crown; however, research indicates that the enamel structure in manatee molars is weak. To compensate for this, manatee teeth are continually replaced. When anterior molars wear down, they are shed. Posterior molars erupt at the back of the row and slowly move forward to replace these like enamel crowns on a conveyor belt, similarly to elephants. This process continues throughout the manatee's lifetime. The rate at which the teeth migrate forward depends on how quickly the anterior teeth abrade. Some studies indicate that the rate is about 1 cm/month although other studies indicate 0.1 cm/month.[29]

Ecology

[edit]Range and habitat

[edit]

Manatees inhabit the shallow, marshy coastal areas and rivers of the Caribbean Sea and the Gulf of Mexico (T. manatus, West Indian manatee), the Amazon basin (T. inunguis, Amazonian manatee), and West Africa (T. senegalensis, West African manatee).[32]

West Indian manatees prefer warmer temperatures and are known to congregate in shallow waters. They frequently migrate through brackish water estuaries to freshwater springs. They cannot survive below 15 °C (60 °F). Their natural source for warmth during winter is warm, spring-fed rivers.

West Indian

[edit]The coast of the state of Georgia is usually the northernmost range of the West Indian manatees because their low metabolic rate does not protect them in cold water. Prolonged exposure to water below 20 °C (68 °F) can cause "cold stress syndrome" and death.[33]

West Indian manatees can move freely between fresh water and salt water. However, studies suggest that they are susceptible to dehydration if freshwater is not available for an extended period of time.[34]

Manatees can travel hundreds of miles annually,[35] and have been seen as far north as Cape Cod, and in 1995[36] and again in 2006, one was seen in New York City[37] and Rhode Island's Narragansett Bay. A manatee was spotted in the Wolf River harbor near the Mississippi River in downtown Memphis in 2006, and was later found dead 16 km (10 mi) downriver in McKellar Lake.[38] Another manatee was found dead on a New Jersey beach in February 2020, considered especially unusual given the time of year.[39] At the time of the manatee's discovery, the water temperature in the area was below 6.5 °C (43.7 °F).[40]

The West Indian manatee migrates into Florida rivers—such as the Crystal, the Homosassa, and the Chassahowitzka rivers, whose headsprings are 22 °C (72 °F) all year. Between November and March each year, about 600 West Indian manatees gather in the rivers in Citrus County, Florida such as the Crystal River National Wildlife Refuge.[41]

In winter, manatees often gather near the warm-water outflows of power plants along the Florida coast, instead of migrating south as they once did. Some conservationists are concerned that these manatees have become too reliant on these artificially warmed areas.[42]

Accurate population estimates of the West Indian manatee in Florida are difficult. They have been called scientifically weak[43] because they vary widely from year to year, with most areas showing decreases, and little strong evidence of increases except in two areas. Manatee counts are highly variable without an accurate way to estimate numbers. In Florida in 1996, a winter survey found 2,639 manatees; in 1997, a January survey found 2,229, and a February survey found 1,706.[21] A statewide synoptic survey in January 2010 found 5,067 manatees living in Florida, the highest number recorded to that time.[44]

As of January 2016, the USFWS estimates the range-wide West Indian manatee population to be at least 13,000; as of January 2018, at least 6,100 are estimated to be in Florida.[45][46]

Population viability studies conducted in 1997 found that decreasing adult survival and eventual extinction were probable future outcomes for Florida manatees unless they received more protection.[47] The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed downgrading the manatee's status from endangered to threatened in January 2016 after more than 40 years.[48]

There is a small population of the subspecies Antillean manatee (T. m. manatus) found in Mexico's Caribbean coastal area. The best estimate for this population is 200-250.[49] As of 2022, a new manatee habitat was discovered by Klaus Thymann within the cenotes of Sian Ka'an Biosphere Reserve on the Yucatán Peninsula. The explorer and his team documented the discovery with a 12-minute film that is available on the interactive streaming platform WaterBear.[50] The discovery got picked up by the New Scientist in 2024, who featured in a 10-minute short film.[51]

Amazonian

[edit]The freshwater Amazonian manatee (T. inunguis) inhabits the Central Amazon Basin in Brazil, eastern Perú, southeastern Colombia, but not Ecuador. It is the only exclusively freshwater manatee, and is also the smallest. Since they are unable to reduce peripheral heat loss, it is found primarily in tropical waters.[52]

West African

[edit]They are found in coastal marine and estuarine habitats, and in freshwater river systems along the west coast of Africa from the Senegal River south to the Cuanza River in Angola. They live as far upriver on the Niger River as Koulikoro in Mali, 2,000 km (1,200 mi) from the coast.[53]

Predation

[edit]In relation to the threat posed by humans, predation does not present a significant threat to manatees.[16] When threatened, the manatee's response is to dive as deeply as it can, suggesting that threats have most frequently come from land dwellers such as humans rather than from other water-dwelling creatures such as caimans or sharks.[16]

Relation to humans

[edit]Threats

[edit]

The main causes of death for manatees are human-related issues, such as habitat destruction and human objects. Natural causes of death include adverse temperatures, predation by crocodiles on young, and disease.[54]

Ship strikes

[edit]Their slow-moving, curious nature, coupled with dense coastal development, has led to many violent collisions with propeller-driven boats and ships, leading frequently to maiming, disfigurement, and even death. As a result, a large proportion of manatees exhibit spiral cutting propeller scars on their backs, usually caused by larger vessels that do not have skegs in front of the propellers like the smaller outboard and inboard-outboard recreational boats have. They are now even identified by humans based on their scar patterns. Many manatees have been cut in two by large vessels like ships and tug boats, even in the highly populated lower St. Johns River's narrow channels. Some are concerned that the current situation is inhumane, with upwards of 50 scars and disfigurements from vessel strikes on a single manatee.[55] Often, the lacerations lead to infections, which can prove fatal. Internal injuries stemming from being trapped between hulls and docks and impacts have also been fatal. Testing and studies from the 2000s and 2010s suggested that manatees may be able to hear speed boats and other watercraft approaching, due to the frequency the boat makes.[56][57] However, a manatee may not be able to hear the approaching boats when they are performing day-to-day activities or distractions. The manatee has a tested frequency range of 8 to 32 kilohertz.[56]

Manatees hear on a higher frequency than would be expected for such large marine mammals. Many large boats emit very low frequencies, which confuse the manatee and explain their lack of awareness around boats. The Lloyd's mirror effect results in low frequency propeller sounds not being discernible near the surface, where most accidents occur. Research indicates that when a boat has a higher frequency the manatees rapidly swim away from danger.[58]

In 2003, a population model was released by the United States Geological Survey that predicted an extremely grave situation confronting the manatee in both the Southwest and Atlantic regions where the vast majority of manatees are found. It states,

In the absence of any new management action, that is, if boat mortality rates continue to increase at the rates observed since 1992, the situation in the Atlantic and Southwest regions is dire, with no chance of meeting recovery criteria within 100 years.[59] "Hurricanes, cold stress, red tide poisoning and a variety of other maladies threaten manatees, but by far their greatest danger is from watercraft strikes, which account for about a quarter of Florida manatee deaths," said study curator John Jett.[60]

According to marine mammal veterinarians:

The severity of mutilations for some of these individuals can be astounding – including long term survivors with completely severed tails, major tail mutilations, and multiple disfiguring dorsal lacerations. These injuries not only cause gruesome wounds, but may also impact population processes by reducing calf production (and survival) in wounded females – observations also speak to the likely pain and suffering endured.[21] In an example, they cited one case study of a small calf "with a severe dorsal mutilation trailing a decomposing piece of dermis and muscle as it continued to accompany and nurse from its mother ... by age 2 its dorsum was grossly deformed and included a large protruding rib fragment visible."[21]

These veterinarians go on to state:

[T]he overwhelming documentation of gruesome wounding of manatees leaves no room for denial. Minimization of this injury is explicit in the Recovery Plan, several state statutes, and federal laws, and implicit in our society's ethical and moral standards.[21]

One quarter of annual manatee deaths in Florida are caused by boat collisions with manatees.[61] In 2009, of the 429 Florida manatees recorded dead, 97 were killed by commercial and recreational vessels, which broke the earlier record number of 95 set in 2002.[62][63]

Red tide

[edit]Another cause of manatee deaths are red tides, a term used for the proliferation, or "blooms", of the microscopic marine algae Karenia brevis. This dinoflagellate produces brevetoxins that can have toxic effects on the central nervous system of animals.[64]

In 1996, a red tide was responsible for 151 manatee deaths in Florida.[65] The bloom was present from early March to the end of April and killed approximately 15% of the known population of manatees along South Florida's western coast.[66] Other blooms in 1982 and 2005 resulted in 37 and 44 deaths respectively,[67] and a red tide killed 123 manatees between November 2022 and June 2023.[68]

Starvation

[edit]In 2021 a massive die-off of seagrass along the Atlantic coast of Florida left manatees without enough food to eat, and they began dying at high rates.[69] The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service responded with a feeding program that distributing 3,000 pounds (1,361 kg) of lettuce per day to the manatee population.[70]

Additional threats

[edit]Manatees can also be crushed and isolated in water control structures (navigation locks, floodgates, etc.) and are occasionally killed by entanglement in fishing gear, such as crab pot float lines, box traps, and shark nets.[53]

While humans are allowed to swim with manatees in one area of Florida,[71] there have been numerous charges of people harassing and disturbing the manatees.[72] According to the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, approximately 99 manatee deaths each year are related to human activities.[73] In January 2016, there were 43 manatee deaths in Florida alone.[74]

Conservation

[edit]

All three species of manatee are listed by the World Conservation Union as vulnerable to extinction. However, The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) does not consider the West Indian manatee to be "endangered" anymore, having downgraded its status to "threatened" as of March 2017. They cite improvements to habitat conditions, population growth and reductions of threats as reasoning for the change. The reclassification was met with controversy, with Florida congressman Vern Buchanan and groups such as the Save the Manatee Club and the Center for Biological Diversity expressing concerns that the change would have a detrimental effect on conservation efforts.[75] The new classification will not affect current federal protections.[45] West Indian manatees were originally classified as endangered with the 1967 class of endangered species.[76]

Manatee deaths in the state of Florida nearly doubled in 2021 from 637 (2020) to 1100.[77] Although this number decreased to 800 in 2022, it is likely that current rate of development in Florida, climate change, and decreasing water quality, habitat range, and genetic diversity among this population may lead to reconsideration of the West Indian Manatee as an endangered species.[78] Manatee population in the United States reached a low in the 1970s, during which only a few hundred individuals lived in the nation.[79] As of February 2016, 6,250 manatees were reported swimming in Florida's springs.[80] It is illegal under federal and Florida law to injure or harm a manatee.

Also in Florida, due to extensive destruction of their habitat, manatees rely on the warm waters created by a major power plant's hot water effluent streams to survive during the cold winter months. Manatee reliance on these effluent streams is such that the streams are protected under federal environmental legislation. Researchers have theorized that the prevalence of manatee sightings near this power plant is contributing to "collective inattention" to industrialization and development as ongoing causes of manatee habitat destruction.[81][82]

There are many conservation programs that have been created to help manatees. Save the Manatee Club is a non-profit group and membership organization that works to protect manatees and their aquatic ecosystems. Founded by Bob Graham, former Florida governor, and singer/songwriter Jimmy Buffett, this is today's leading manatee conservation club.[83][self-published source?]

The MV Freedom Star and MV Liberty Star, ships used by NASA to tow Space Shuttle Solid Rocket Boosters back to Kennedy Space Center, were propelled only by water jets to protect the endangered manatee population that inhabits regions of the Banana River where the ships are based.

Brazil outlawed hunting in 1973 in an effort to preserve the species. Deaths by boat strikes are still common.[84][85] Although countries are protecting Amazonian manatees in the locations where they are endangered, as of 1994 there were no enforced laws, and the manatees were still being captured throughout their range.[86]

Captivity

[edit]

There are a number of manatee rehabilitation centers in the United States. These include three government-run critical care facilities in Florida at Lowry Park Zoo, Miami Seaquarium, and SeaWorld Orlando. After initial treatment at these facilities, the manatees are transferred to rehabilitation facilities before release. These include the Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden, Columbus Zoo and Aquarium, Epcot's The Seas, South Florida Museum, and Homosassa Springs Wildlife State Park.[87]

The Columbus Zoo was a founding member of the Manatee Rehabilitation Partnership in 2001. Since 1999, the zoo's Manatee Bay facility has helped rehabilitate 20 manatees.[88] The Cincinnati Zoo has rehabilitated and released more than a dozen manatees since 1999.[89]

Manatees can also be viewed in a number of European zoos, such as the Tierpark Berlin and the Nuremberg Zoo in Germany, in ZooParc de Beauval in France, the Aquarium of Genoa in Italy and the Royal Burgers' Zoo in Arnhem, the Netherlands, where manatees have parented offspring.[90] The River Safari at Singapore features seven of them.[91]

The oldest manatee in captivity was Snooty,[92] at the South Florida Museum's Parker Manatee Aquarium in Bradenton, Florida. Born at the Miami Aquarium and Tackle Company on July 21, 1948, Snooty was one of the first recorded captive manatee births. Raised entirely in captivity, Snooty was never to be released into the wild. As such he was the only manatee at the aquarium, and one of only a few captive manatees in the United States that was allowed to interact with human handlers. That made him uniquely suitable for manatee research and education.[93]

Snooty died suddenly two days after his 69th birthday, July 23, 2017, when he was found in an underwater area only used to access plumbing for the exhibit life support system. The South Florida Museum's initial press release stated, "Early indications are that an access panel door that is normally bolted shut had somehow been knocked loose and that Snooty was able to swim in."[94]

Guyana

[edit]Since the 19th century, Georgetown, Guyana has kept West Indian manatees in its botanical garden, and later, its national park.[95] In the 1910s and again in the 1950s, sugar estates in Guyana used manatees to keep their irrigation canals weed-free.[96] Between the 1950s and 1970s, the Georgetown water treatment plant used manatees in their storage canals for the same purpose.[97]

Culture

[edit]

The manatee has been linked to folklore on mermaids.[84] In West African folklore, they were considered sacred and thought to have been once human. Killing one was taboo and required penance.[98] In the cosmogony of the Serer people of Senegal, Gambia, and Mauritania, the cayman and the manatee holds great significance in Serer mythology. The cayman is believed to hold the secrets of the past whilst the manatee holds the secrets of the future.[99]

In the novel Moby-Dick, Herman Melville distinguishes manatees ("Lamatins", cf. lamantins) from small whales; stating, "I am aware that down to the present time, the fish styled Lamatins and Dugongs (Pig-fish and Sow-fish of the Coffins of Nantucket) are included by many naturalists among the whales. But as these pig-fish are a noisy, contemptible set, mostly lurking in the mouths of rivers, and feeding on wet hay, and especially as they do not spout, I deny their credentials as whales; and have presented them with their passports to quit the Kingdom of Cetology."[100]

A manatee called Wardell appears in the Animal Crossing: New Horizons video game. He is part of a paid downloadable content expansion, managing and selling furniture to the player.[101]

In Rudyard Kipling's The White Seal (one of the stories in The Jungle Book), Sea Cow, about whom the story says that he has only six cervical vertebrae, is a manatee.

The manatees Friends West Indian Manatee, Dugong, and Steller's Sea Cow appear in multiple Kemono Friends games, including the app version of Kemono Friends 3.[102][103][104]

In the Neapolitan region of Italy, a culinary legend exists around the consumption of manatees during World War II. In the story, when Naples and Salerno surrended to the Allies in 1943, the cities, lacking food supplies thanked the Allied generals by serving manatee from the aquarium. When this was revealed, the popular reaction was not shock, but questions over how it was prepared, to which the answer was "aglio-olio [garlic and olive oil], of course, with a little parsley."[105]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Trichechus Linnaeus 1758 (manatee)". Fossilworks.org. Archived from the original on 2023-06-05. Retrieved 2021-12-17.

- ^ West Indian Manatee Facts and Pictures – National Geographic Kids Archived 2011-06-26 at the Wayback Machine. Kids.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved on 2011-12-03.

- ^ Winger, Jennifer (2000). "What's in a name? Manatees and Dugongs". National Zoological Park. Friends of the National Zoo. Archived from the original on 30 December 2005. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ Russell, Mark (22 December 2023). "Mexico's Manatees – the Sirens of the Caribbean". Dive Magazine. Retrieved 27 December 2024.

- ^ "Manatee Facts". Save the Manatee Club. 2024. Retrieved 27 December 2024.

- ^ Walters, Martin; Johnson, Jinny (2003). Encyclopedia of Animals. Marks and Spencer. p. 229. ISBN 1-84273-964-6.

- ^ "Lamantin". Oxford English Dictionary.

- ^ Domning, D.P., 1994, "Paleontology and evolution of sirenians: Status of knowledge and research needs", in Proceedings of the 1st International Manatee and Dugong Research Conference, Gainesville, Florida, 1–5

- ^ "The Florida Manatee (Trichechus manatus latirostrus)". The Amy H Remley Foundation. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- ^ Shoshani, J., ed. (2000). Elephants: Majestic Creatures of the Wild. Checkmark Books. ISBN 0-87596-143-6.

- ^ a b c d Best, Robin (1984). Macdonald, D. (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. pp. 292–298. ISBN 0-87196-871-1.

- ^ Hautier, Lionel; Weisbecker, V; Sánchez-Villagra, M. R.; Goswami, A; Asher, R. J. (2010). "Skeletal development in sloths and the evolution of mammalian vertebral patterning". PNAS. 107 (44): 18903–18908. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10718903H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1010335107. PMC 2973901. PMID 20956304.

- ^ "Sticking Their Necks out for Evolution: Why Sloths and Manatees Have Unusually Long (or Short) Necks". May 6th 2011. Science Daily. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- ^ Frietson Galis (1999). "Why do almost all mammals have seven cervical vertebrae? Developmental constraints, Hox genes and Cancer" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Zoology. 285 (1): 19–26. Bibcode:1999JEZ...285...19G. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-010X(19990415)285:1<19::AID-JEZ3>3.0.CO;2-Z. PMID 10327647. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-11-10.

- ^ "Manatee Anatomy Facts" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-12-26. Retrieved 2021-12-24.

- ^ a b c Marsh, H. (2011). Ecology and Conservation of the Sirenia: Dugongs and Manatees. O'Shea, Thomas J., Reynolds III, John E. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-15887-9. OCLC 782876868.

- ^ de Souza, Érica Martinha Silva; Freitas, Lucas; da Silva Ramos, Elisa Karen; Selleghin-Veiga, Giovanna; Rachid-Ribeiro, Michelle Carneiro; Silva, Felipe André; Marmontel, Miriam; dos Santos, Fabrício Rodrigues; Laudisoit, Anne; Verheyen, Erik; Domning, Daryl P. (2021-02-11). "The evolutionary history of manatees told by their mitogenomes". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 3564. Bibcode:2021NatSR..11.3564D. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-82390-2. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 7878490. PMID 33574363.

- ^ Domning, Daryl P. (1982). "Evolution of Manatees: A Speculative History". Journal of Paleontology. 56 (3): 599–619. JSTOR 1304394.

- ^ "Manatee FAQ: Behavior". www.savethemanatee.org. Archived from the original on 2016-09-19. Retrieved 2016-09-15.

- ^ Gerstein, E. R. (1994). "The manatee mind: Discrimination training for sensory perception testing of West Indian manatees (Trichechus manatus)". Marine Mammals. 1: 10–21.

- ^ a b c d e (Marine Mammal Medicine, 2001, Leslie Dierauf & Frances Gulland, CRC Press)

- ^ Henaut, Yann; Charles, Aviva; Delfour, Fabienne (24 August 2022). "Cognition of the manatee: past research and future developments". Animal Cognition. 25 (5): 1049–1058. doi:10.1007/s10071-022-01676-8. PMID 36002602. S2CID 251808935. Archived from the original on 30 October 2022. Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- ^ Jeff Ripple (1999). Manatees and Dugongs of the World. Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-1-61060-443-7.

estrous.

- ^ O'Shea, Thomas J.; Lynn B. Poché, Jr. (2006). "Aspects of Underwater Sound Communication in Florida Manatees (Trichechus manatus latirostris)". Journal of Mammalogy. 87 (6): 1061–1071. doi:10.1644/06-MAMM-A-066R1.1. ISSN 0022-2372. JSTOR 4126883. S2CID 42302073.

- ^ "Manatee Ears Cause for Alarm? | Bird's Underwater". Birds Underwater. 2017-08-01. Archived from the original on 2017-10-07. Retrieved 2017-10-06.

- ^ "Animal Info Book: Manatee". Seaworld Parks & Entertainment. Archived from the original on 2017-10-07. Retrieved 2016-08-07.

- ^ Lefebvre, Lynn W.; Provancha, Jane A.; Slone, Daniel H.; Kenworthy, W. Judson (2017). "Manatee grazing impacts on a mixed species seagrass bed". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 564: 29–45. Bibcode:2017MEPS..564...29L. doi:10.3354/meps11986. ISSN 0171-8630. JSTOR 24898254.

- ^ Domning, Daryl P. (1981). "Sea Cows and Sea Grasses". Paleobiology. 7 (4): 417–420. Bibcode:1981Pbio....7..417D. doi:10.1017/S009483730002546X. ISSN 0094-8373. JSTOR 2400692. S2CID 88809167.

- ^ a b c "Manatee". Journey North. 2003. Archived from the original on April 29, 2014. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ Castellini and Mellish, Michael and Jo-Ann (2016). Marine Mammal Physiology. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-4822-4267-6.

- ^ Powell, James (1978). "Evidence for carnivory in manatee (Trichechus manatus)". Journal of Mammalogy. 59 (2): 442. doi:10.2307/1379938. JSTOR 1379938.

- ^ Trials of a Primatologist. – smithsonianmag.com. Accessed March 15, 2008.

- ^ Basu, Rebecca (1 March 2010). "Winter is culprit in manatee death toll". Melbourne, Florida: Florida Today. p. 1A. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014.

- ^ Ortiz, RM; Worthy, GA; MacKenzie, DS (July 1998). "Osmoregulation in wild and captive West Indian manatees (Trichechus manatus)" (PDF). Physiological Zoology. 71 (4): 449–57. doi:10.1086/515427. hdl:1969.1/182579. PMID 9678505. S2CID 40972754. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ "Manatee (Trichechus manatus) | U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service". FWS.gov. Archived from the original on 2023-09-13. Retrieved 2023-09-12.

- ^ "TRAVELIN' MANATEE FAR FROM HOME AGAIN". Deseret News. 23 August 1995. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ Lee, Jennifer 8 (7 August 2006). "Massive Manatee Is Spotted in Hudson River". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Manatee found dead in Tenn. lake". Associated Press. 11 December 2006. Archived from the original on 24 September 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- ^ "Dead manatee found along Jersey Shore". ABC7 New York. 2020-02-11. Archived from the original on 2020-02-13. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- ^ Ltd, Copyright Global Sea Temperatures-A.-Connect. "Atlantic City (NJ) Water Temperature | United States | Sea Temperatures". World Sea Temperatures. Archived from the original on 2020-11-27. Retrieved 2020-02-14.

- ^ US Fish and Wildlife Service (November 14, 2017). "About the Refuge". Crystal River National Wildlife Refuge, Florida. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- ^ Keith Morelli (January 7, 2011). "Can manatees survive without warm waters from power plants?". The Tampa Tribune. Retrieved 2012-05-04.

- ^ U.S. Marine Mammal Commission 1999

- ^ "Exceptional weather conditions lead to record high manatee count" (Press release). Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. January 20, 2010. Archived from the original on February 14, 2011. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- ^ a b Service, U. S. Fish and Wildlife. "U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to Reclassify West Indian Manatee from Endangered to Threatened". www.fws.gov (Press release). Archived from the original on 2021-05-08. Retrieved 2021-03-25.

- ^ "Manatee Synoptic Surveys". Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. 2018. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- ^ (Marmontel, Humphrey, O'Shea 1997, "Population Variability Analysis of the Florida Manatee, 1976–1992", Conserv. biol., 11: 467–481)

- ^ "Record 6,250 Manatees Spotted in Florida Waters". Discovery. February 26, 2016. Archived from the original on February 28, 2016. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- ^ Robles Herrejón, Juan Carlos; Morales-Vela, Benjamín; Ortega-Argueta, Alejandro; Pozo, Carmen; Olivera-Gómez, León David (June 2020). "Management effectiveness in marine protected areas for conservation of Antillean manatees on the eastern coast of the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico". Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. 30 (6): 1182–1193. Bibcode:2020ACMFE..30.1182R. doi:10.1002/aqc.3323. ISSN 1052-7613. Archived from the original on 2022-11-21. Retrieved 2024-03-05.

- ^ "WaterBear". www.waterbear.com. Retrieved 2024-03-05.

- ^ Stock, David. "Manatees discovered in pristine but threatened underwater cave habitat". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 2024-02-26. Retrieved 2024-03-05.

- ^ "Amazonian Manatee - Facts, Information & Habitat". Archived from the original on 2021-12-24. Retrieved 2021-12-24.

- ^ a b Keith Diagne, L. (2016). " Trichechus senegalensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016 e.T22104A97168578.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Luiselli, L.; Akani, G.C.; Ebere, N.; Angelici, F. M.; Amori, G.; Politano, E. (2012). "Macro-habitat preferences by the African manatee and crocodiles – ecological and conservation implications". Web Ecology. 12 (1): 39–48. doi:10.5194/we-12-39-2012.

- ^ Florida boaters killing endangered manatees. Cyber Diver News Network. 11 January 2006

- ^ a b Gaspard, Joseph C.; Bauer, Gordon B.; Reep, Roger L.; Dziuk, Kimberly; Cardwell, Adrienne; Read, Latoshia; Mann, David A. (2012). "Audiogram and auditory critical ratios of two Florida manatees (Trichechus manatus latirostris)". Journal of Experimental Biology. 215 (9): 1442–1447. Bibcode:2012JExpB.215.1442G. doi:10.1242/jeb.065649. PMID 22496279. S2CID 11725126.

- ^ Gerstein, Edmund (March–April 2002). "Manatees, Bioacoustics and Boats". American Scientist. p. 154. doi:10.1511/2002.10.154.

- ^ Manatees hard of hearing Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine. Scienceagogo.com (1999-07-30). Retrieved on 2011-12-03.

- ^ Long Term Prospects for Manatee Recovery Look Grim, According To New Data Released By Federal Government Archived 2007-07-12 at the Wayback Machine. Savethemanatee.org (2003-04-29). Retrieved on 2011-12-03.

- ^ ufl.edu Archived 2010-06-12 at the Wayback Machine. News.ufl.edu (2007-07-03). Retrieved on 2011-12-03.

- ^ Aipanjiguly, Sampreethi; Jacobson, Susan K.; Flamm, Richard (2003). "Conserving Manatees: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Intentions of Boaters in Tampa Bay, Florida". Conservation Biology. 17 (4): 1098–1105. Bibcode:2003ConBi..17.1098A. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.2003.01452.x. S2CID 86770081. Archived from the original on 2021-11-26. Retrieved 2021-11-26.

- ^ "Manatee Mortality Statistics". Fish and Wildlife Research Institute. Archived from the original on 1 April 2011. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ^ "Manatee Deaths From Boat Strikes Approach Record: Club Asks For Boaters' Urgent Help". Save the Manatee Club. Archived from the original on 2011-02-08. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ Flewelling, LJ; Naar, JP; Abbott, JP; Baden, DG; Barros, NB; Bossart, GD; Bottein, MY; Hammond, DG; et al. (9 June 2005). "Brevetoxicosis: Red tides and marine mammal mortalities". Nature. 435 (7043): 755–756. Bibcode:2005Natur.435..755F. doi:10.1038/nature435755a. PMC 2659475. PMID 15944690.

- ^ "Manatee death toll hits record in Florida, 'Red Tide' blamed". Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 September 2018. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ^ "Scientists Say Toxin in Red Tide Killed Scores of Manatees". New York Times. July 5, 1996. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ "Mystery epidemic killing manatees". Local & State. April 9, 1996. p. 38. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ^ "2023 Bloom". Florida Fish And Wildlife Conservation Commission. Archived from the original on 2024-04-04. Retrieved 2024-04-09.

- ^ Greg Allen (2 Dec 2021). "Manatees are starving in Florida. Wildlife agencies are scrambling to save them". NPR. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 Feb 2022.

- ^ Amanda Jackson (17 Feb 2022). "Florida wildlife officials are distributing 3,000 pounds of lettuce a day to save starving manatees". CNN. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ Help End Manatee Harassment in Citrus County, Florida! Archived 2007-04-30 at the Wayback Machine. Savethemanatee.org. Retrieved on 2011-12-03.

- ^ St. Petersburg Times – Manatee Abuse Caught on Tape Archived 2009-06-01 at the Wayback Machine. Sptimes.com. Retrieved on 2011-12-03.

- ^ Tribune, Chicago (29 February 2016). "Monarch butterfly, manatee populations are on a big rebound". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

- ^ "January 2016 Preliminary Manatee Mortality Table by County" (PDF). January 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 6, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- ^ Wang, Amy B. (March 31, 2017). "Manatees are no longer listed as endangered. Should we celebrate or fret?". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- ^ "Endangered Species | Class of 1967". www.fws.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-05-24. Retrieved 2020-01-30.

- ^ "FLORIDA FISH AND WILDLIFE CONSERVATION COMMISSION MARINE MAMMAL PATHOBIOLOGY LABORATORY Preliminary 2022 Manatee Mortality Table by County" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-03-24. Retrieved 2023-03-24.

- ^ Jones Jr., Robert C. (February 2, 2022). "NO LONGER ENDANGERED, MANATEES NOW FACE ANOTHER CRISIS". Archived from the original on March 24, 2023. Retrieved March 24, 2023.

- ^ "Manatee reclassified from endangered to threatened as habitat improves and population expands - existing federal protections remain in place". Southeast Region of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Archived from the original on 2020-05-29. Retrieved 2020-04-07.

- ^ "Record-breaking number of manatees counted during annual winter survey". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

- ^ Carr, John; Milstein, Tema (2018). "Keep Burning Coal or the Manatee Gets It: Rendering the Carbon Economy Invisible through Endangered Species Protection". Antipode. 50: 82–100.

- ^ Carr, John; Milstein, Tema (2021). "'"See nothing but beauty": The shared work of making anthropogenic destruction invisible to the human eye". Geoforum. 122: 183–192.

- ^ "Save The Manatees". Save The Manatees. Archived from the original on 2021-11-23. Retrieved 2021-11-23.

- ^ a b Fairclough, Caty. "From Mermaids to Manatees: the Myth and the Reality | Smithsonian Ocean". ocean.si.edu. Retrieved 2021-12-24.

- ^ "New Study Shows Impact of Watercraft on Manatees". Florida Fish And Wildlife Conservation Commission. Archived from the original on 2021-12-24. Retrieved 2021-12-24.

- ^ Weber Rosas, F.C. (June 1994). "Biology, conservation, and status of the Amazonian Manatee Trichechus inunguis". Mammal Review. 24 (2): 49–59. Bibcode:1994MamRv..24...49R. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.1994.tb00134.x.

- ^ "Manatee Rescue, Rehabilitation and Release Program". Archived from the original on 2017-01-01. Retrieved 2016-12-31.

- ^ "Global Impact - Project". Archived from the original on 2015-09-05. Retrieved 2016-12-31.

- ^ "Rescue, Rehabilitation and Release of Florida Manatees". Archived from the original on 2017-01-01. Retrieved 2016-12-31.

- ^ "Adventure in the mangrove forest". Archived from the original on 2021-06-11. Retrieved 2021-06-11.

- ^ Tan, Sue-Ann (13 March 2013). "Manatees move into world's largest freshwater aquarium at River Safari". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 2013-05-19. Retrieved 2013-07-24.

- ^ Aronson, Claire. "Guinness World Records names Snooty of Bradenton as 'Oldest Manatee in Captivity'". bradenton.com. Bradenton Herald. Archived from the original on 28 June 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ Snooty the Manatee. South Florida Museum. ISBN 978-1-56944-441-2.

- ^ "Oldest living manatee in captivity dies a day after celebrating 69th birthday". 23 July 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-07-23. Retrieved 2017-07-23.

- ^ "Abary Creek manatees under threat". Stabroek News. 30 September 2008. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

there are 23 manatees [...] between the Botanical Gardens and the National Park. They have been there for more than 129 years, and reports are that they came from the Abary Creek.

[dead link] - ^ National Science Research Council (Guyana). (1974). An International Centre for Manatee Research. Georgetown, Guyana: National Academies. p. 13.

- ^ National Research Council (2002). Making Aquatic Weeds Useful. The Minerva Group. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-89499-180-6.

In the Georgetown Water and Sewerage Works, two manatees [...] were introduced in 1952 to a canal [...] In the 24 years since then, manatees have been used to keep this water (the city's municipal supply) weed-free.

- ^ Cooper, JC (1992). Symbolic and Mythological Animals. London: Aquarian Press. p. 157. ISBN 1-85538-118-4.

- ^ Senghor, Léopold Sédar, "Chants d'ombre" [in] "Selected poems of LEOPOLD SEDAR SENGHOR", CUP Archive, pp. 103, 125

- ^ Melville, Herman (1851). "Footnote, Chapter 32 - Cetology". Moby-Dick; or, The Whale. Richard Bentley.

- ^ Fahey, Mike (18 October 2021). "Animal Crossing Fans Are Deeply In Love With Wardell The Manatee". Kotaku. G/O Media. Archived from the original on 27 October 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2022.

- ^ @kemono_friends3 (January 25, 2024). "\しょうたい/ 『ステラーカイギュウすてっぷあっぷしょうたい』開催中! ☆4『ステラーカイギュウ』登場! CVは #新谷良子 さん! フレンズ紹介PVをご覧ください♪ けものミラクル「マーメイド戦士、ここに参上♡」" (Tweet). Retrieved 2025-09-06 – via Twitter.

- ^ @kemono_friends3 (August 15, 2024). "\しょうたい/ 『ジュゴンすてっぷあっぷしょうたい』開催中! ☆4『ジュゴン』登場! CVは #髙橋ミナミ さん! フレンズ紹介PVをご覧ください♪ けものミラクル「届け!マーメイドの歌声」" (Tweet). Retrieved 2025-09-06 – via Twitter.

- ^ @kemono_friends3 (May 23, 2024). "\しょうたい/ 『マナティーすてっぷあっぷしょうたい』開催中! ☆4『マナティー』登場! CVは #藍原ことみ さん! フレンズ紹介PVをご覧ください♪ けものミラクル「乙女のいちげきー!なんだから」" (Tweet). Retrieved 2025-09-06 – via Twitter.

- ^ Schwartz, Arthur (1998). Naples at Table: Cooking in Campania. New York: HarperCollins. pp. 227. ISBN 0-06-018261-X.

Further reading

[edit]- Hall, Alice J. (September 1984). "Man and Manatee: Can We Live Together?". National Geographic. Vol. 166, no. 3. pp. 400–418. ISSN 0027-9358. OCLC 643483454.

External links

[edit]- Save the Manatee Archived 2013-05-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Murie, James On the Form and Structure of the Manatee (Manatus americanus), (1872) London, Zoological Society of London Year

- Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Archived 2018-12-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Reuters: Florida manatees may lose endangered status Archived 2020-09-25 at the Wayback Machine

- A website with many manatee photos

- USGS/SESC Sirenia Project Archived 2010-05-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Bibliography and Index of the Sirenia and Desmostylia – Dr. Domning's authoritative manatee research bibliography

Manatee

View on GrokipediaManatees are large, fully aquatic, herbivorous mammals comprising the genus Trichechus in the family Trichechidae and order Sirenia, distinguished by their rounded bodies, paddle-like forelimbs, flattened tails, and absence of hind limbs. [1][2] They inhabit shallow, warm coastal waters, rivers, estuaries, and lagoons across tropical and subtropical regions, including the Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico, Amazon and Orinoco basins, and West African coasts. [1][3] Three extant species exist: the West Indian manatee (T. manatus), African manatee (T. senegalensis), and Amazonian manatee (T. inunguis), with adults typically measuring 2.7 to 4.5 meters in length and weighing 200 to 600 kilograms. [2][4] Primarily sirenians feed on aquatic vegetation such as seagrasses and freshwater plants, consuming up to 10% of their body weight daily and spending much of their time grazing. [1][3] Reproduction involves a gestation period of approximately 12 months, yielding usually a single calf that nurses for up to two years, with breeding intervals of two to three years. [5] All manatee species face significant threats from habitat degradation, boat collisions, and incidental entanglement, leading to their classification as vulnerable or endangered under various conservation frameworks, including protections under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. [1][6][7]

Etymology

Origins and Linguistic Evolution

The term "manatee" derives from the Spanish manatí, first attested in the 1530s, which was borrowed from indigenous Caribbean languages of the Carib or Taíno peoples, where it meant "breast" (manati or manatɨ), likely referring to the animal's rounded pectoral glands or mammary-like appearance.[8] [9] This Proto-Cariban root manatɨ appears in related languages such as Kari'na manaty and Trió manatï, indicating a shared linguistic heritage among Arawakan and Cariban-speaking groups in the Antilles and South America who encountered the West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus).[9] Early European explorers, including Spanish colonizers in the 16th century, adopted the term during voyages to the Caribbean and Florida, where manatees were abundant; the Spanish manatí may have been misinterpreted by some as implying "with hands" due to the flipper-like forelimbs, though primary etymological evidence supports the "breast" connotation.[10] The word entered English by 1555, as recorded in nautical and natural history texts describing sirenians observed off West Indian coasts, evolving from direct phonetic borrowing without significant alteration.[11] Over time, "manatee" became the standard English designation for the genus Trichechus, distinguishing it from related sirenians like the dugong, whose name derives from Malay duyong via Tagalog, unrelated to Caribbean roots.[12] This linguistic path reflects broader patterns of colonial-era nomenclature, where indigenous terms for local fauna were Latinized or anglicized for scientific use, as seen in early accounts by explorers like Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés in his 1535 General y Natural Historia de las Indias.[13] No evidence supports alternative derivations, such as from Latin manus ("hand"), despite superficial morphological similarities.[8]Taxonomy and Phylogeny

Classification and Species

Manatees are classified within the order Sirenia, a group of herbivorous, fully aquatic mammals that also includes the dugong family Dugongidae.[1] The family Trichechidae encompasses all manatee species, characterized by rounded, paddle-shaped tails, unlike the fluked tails of dugongs.[14] The genus Trichechus, established by Carl Linnaeus, contains the three extant manatee species, with no other genera in the family.[15] The West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus) inhabits coastal and estuarine waters from the southeastern United States to northeastern South America, including the Caribbean.[16] It comprises two subspecies: the Florida manatee (T. m. latirostris), restricted to U.S. waters, and the Antillean manatee (T. m. manatus), found in the Caribbean and northern South America; these differ in cranial measurements and geographic range.[1] Adults typically measure 2.8 to 4.0 meters in length and weigh 400 to 500 kilograms, with nail-bearing flippers.[2] The Amazonian manatee (Trichechus inunguis) is the only strictly freshwater manatee species, confined to the Amazon River basin in South America.[17] It is the smallest species, reaching up to 2.8 meters and 500 kilograms, and lacks nails on its flippers—reflected in its specific epithet meaning "nailless."[17] Genetic and morphological analyses confirm its distinctiveness from other Trichechus species.[18] The African manatee (Trichechus senegalensis), also known as the West African manatee, occurs in coastal marine, estuarine, and riverine habitats from the Senegal River to Angola.[2] Comparable in size to T. manatus (up to 4.5 meters and 500 kilograms), it features more protruding eyes, a blunter snout, and subtle cranial differences distinguishing it taxonomically.[19]Evolutionary History

The order Sirenia, encompassing manatees and their relatives, originated around 50 million years ago in the early Eocene epoch from terrestrial, herbivorous ancestors within the Tethytheria clade, which also gave rise to proboscideans like elephants; these ancestors likely resembled wading mammals exploiting coastal vegetation.[20][21] Fossils of Pezosiren portelli, dated to approximately 48 million years ago from Jamaica, represent the earliest known sirenian and demonstrate a transitional form between terrestrial and aquatic lifestyles, featuring a quadrupedal skeleton with weight-bearing hind limbs alongside a sirenian-style skull, dentition, and torso adapted for shallow-water foraging.[22][23] Subsequent sirenian evolution involved progressive adaptations to obligate aquatic habitats, including the complete loss of external hind limbs and their associated pelvic girdle detachment from the vertebral column, as well as the development of a broad, horizontal tail fluke enabling efficient propulsion through vertical oscillations; these changes were driven by selective pressures for enhanced maneuverability in marine environments, where abundant seagrasses provided food but demanded streamlined forms to evade predators and optimize energy use in water's higher density.[21][24][25] The manatee lineage (family Trichechidae) emerged later, with the West Indian manatee (Trichechus manatus) showing fossil and genetic evidence of continuous presence in Florida for at least the past 12,000 years, coinciding with post-glacial habitat stabilization rather than recent anthropogenic introduction.[26][27]Physical Characteristics

Anatomy and Morphology

Manatees possess a robust, fusiform body form optimized for buoyancy and slow aquatic movement, typically attaining adult lengths of 3 to 3.5 meters and weights of 400 to 600 kilograms, though exceptional individuals exceed 4 meters and 1,500 kilograms.[28] Females consistently surpass males in size across species.[29] The torso is barrel-shaped, lacking hind limbs and external hindquarter distinctions, with the integument consisting of thick, wrinkled, gray to dark brown epidermis sparsely covered in short, bristle-like hairs that provide minimal insulation but facilitate tactile detection.[30] Pectoral flippers, modified forelimbs, measure up to 0.8 meters in span and feature five embedded digits sheathed in leathery skin, terminating in three to four keratinous nails; these structures enable steering, substrate contact, and object manipulation, with underlying osteology retaining phalangeal elements homologous to terrestrial mammal hands.[31] The caudal region culminates in a horizontally flattened, rounded fluke divided into two lobes, generating thrust via dorsoventral oscillations at frequencies of 1 to 2 hertz, propelling the animal at sustained speeds of 5 to 7 kilometers per hour.[31] Absent hind limbs reflect evolutionary paedomorphosis, with vestigial pelvic girdle bones embedded internally, unconnected to the axial skeleton.[30] Cranially, the head is dorsoventrally compressed with a blunt muzzle, diminutive eyes positioned laterally, and no external pinnae, though subcutaneous auditory bullae amplify underwater sound reception.[32] Facial vibrissae form distinct perioral fields—up to nine patches of innervated bristles—serving prehensile and mechanosensory roles in foraging and exploration, distinct from sparse body pelage.[33] Dentition comprises continuously erupting, "marching" molars in a serial replacement system, with four generational sets of six to eight teeth each, adapted for grinding abrasive vegetation; incisors and canines are absent.[31] Internally, the ribcage houses paired lungs extending longitudinally along the dorsal vertebral column, spanning up to 3 meters and comprising 15 to 20 percent of body volume for enhanced buoyancy control, separated from ventral viscera by a transverse septum.[34] The gastrointestinal tract dominates abdominal volume, with intestines exceeding 45 meters in length to accommodate herbivorous fermentation, while the liver and kidneys exhibit lobulated morphologies supporting osmotic regulation in brackish environments.[31] Skeletal density approaches that of seawater due to pachyosteosclerosis—thickened, avascular ribs and vertebrae—minimizing energy expenditure on postural maintenance.[35]Adaptations to Aquatic Life

Manatees possess morphological traits distinguishing them from terrestrial mammals, such as a robust, streamlined torso, modified forelimbs into paddle-like flippers, and a broadened, horizontal tail fluke, facilitating an exclusively aquatic existence.[web:44][web:42] Their skeletal structure features pachyosteosclerosis, with hyperdense bones that elevate body density to counteract buoyancy from voluminous intestinal gas generated by fermenting low-nutrient aquatic vegetation.[web:6] Physiologically, manatees achieve osmoregulation through multilobulated, reniculate kidneys that produce highly concentrated urine exceeding seawater osmolarity (up to 1,160 mOsm/L) in brackish conditions, while generating dilute urine in freshwater to expel surplus hypotonic intake and maintain internal balance.[web:15][web:10][web:11] This renal versatility supports tolerance for varying salinities in coastal and riverine habitats, though prolonged exposure to full seawater may elevate plasma osmolality without freshwater access.[web:13] Sensory adaptations include densely innervated vibrissae covering the body, particularly facial bristles specialized for tactile detection of submerged vegetation and hydrodynamic cues in low-visibility waters, enabling precise foraging without reliance on vision.[web:27][web:29][web:30] These mechanosensitive hairs function analogously to lateral lines in fish, processing water movements for environmental awareness.[web:31] Thermoregulation poses a limitation, as manatees cannot endure water below 20°C (68°F) for extended durations, incurring cold-stress syndrome akin to hypothermia due to scant blubber insulation and tropical ancestry.[web:20][web:21][web:24] Vascular countercurrent heat exchangers in the tail conserve core warmth but prove insufficient against sustained chill.[web:5][web:37] Growth trajectories underscore their herbivorous niche, with captive Amazonian manatees averaging 0.11 kg/month in males, slower than carnivorous dolphins' rapid early development, prioritizing energy conservation over velocity in a low-caloric diet context.[web:51][web:47][web:54] Lacking predatory defenses beyond bulk, adults face minimal threats, though calves risk crocodilian or shark attacks, reflecting evolved docility in predator-scarce ecosystems.[web:43]Behavior and Physiology

Locomotion and Sensory Capabilities

Manatees achieve locomotion through undulatory waves propagating along the body, culminating in powerful oscillations of the paddle-shaped caudal fluke, which generates primary thrust.[36] Forelimb flippers facilitate steering, stability, and precise maneuvering, allowing capabilities such as tight turns and somersaults.[37] Observed swimming velocities typically range from 0.06 to 1.14 m/s (0.13–2.55 mph), corresponding to routine foraging and transit, though short bursts can exceed 15 mph (24 km/h) during predator evasion or rapid escapes.[36][38] This propulsion efficiency stems from their fusiform body shape and low metabolic demands, minimizing energy expenditure in shallow, coastal habitats.[39] Manatees exhibit sensory adaptations optimized for murky, low-light aquatic environments, with vision providing limited utility; they possess moderate acuity for detecting brightness gradients, object sizes, and basic patterns but demonstrate myopia and reliance on other modalities for detailed perception.[40] Auditory capabilities encompass a broad frequency range of approximately 400–46,000 Hz, enabling detection of conspecific vocalizations such as squeaks and chirps used in communication, though sensitivity peaks at frequencies relevant to social and environmental cues.[41] Tactile sensing dominates via densely distributed vibrissae—roughly 2,000 facial and 3,300 postcranial hairs—that innervate specialized follicles acting as hydrodynamic receptors, akin to a lateral line system, for discerning water currents, prey proximity, and obstacles through mechanosensory deflection.[42][43] These vibrissae support fine-scale discrimination during feeding and navigation, compensating for visual deficits in turbid conditions.[44] Olfactory detection occurs via nares, aiding in chemosensory orientation to food sources or mates, though efficacy diminishes in saline waters.[45]Feeding Mechanisms and Diet

Manatees are obligate herbivores that primarily consume aquatic vegetation, including seagrasses, algae, and vascular plants, as evidenced by stomach content analyses from necropsied individuals.[46][47] In the Indian River Lagoon, pre-seagrass die-off samples showed dominance of seagrasses, while post-die-off contents shifted to algae (49.5%) and remaining seagrasses (34%).[46] These analyses, derived from direct examination of digestive tracts, confirm selective intake of available submerged and emergent plants, with over 60 species documented across habitats, though preferences favor nutrient-dense options like certain seagrasses in the wild.[4][48] Daily consumption ranges from 4% to 9% of body weight in wet vegetation, equating to 15-49 kg (32-108 lb) for an average adult manatee weighing approximately 500 kg.[49] This high-volume intake compensates for the low nutritional density of aquatic plants, with individuals spending 5-8 hours foraging daily.[50] In captivity, opportunistic ingestion of invertebrates or fish occurs but constitutes negligible dietary contributions in wild populations, where empirical evidence from stomach and fecal samples shows exclusively plant matter.[47] Feeding involves prehensile lips that grasp vegetation, followed by grinding via specialized dentition lacking incisors or canines. Manatees possess 6-8 molariform teeth per jaw quadrant in a unique "marching molars" system, where new molars erupt at the rear and migrate forward as anterior ones wear from abrasive silica in plants, ensuring continuous replacement throughout life.[40][4] This adaptation supports processing tough, fibrous material, with teeth advancing at rates tied to wear, observed in both wild and captive specimens.[51] Physiologically, manatees employ hindgut fermentation in a capacious cecum and colon, comprising up to 70% of gut mass, to break down cellulose via microbial action.[52] Digestibility coefficients reach 80% for cellulose, among the highest for mammalian herbivores, though overall nutrient assimilation requires voluminous intake due to plant recalcitrance.[53] Slow digesta passage rates enhance extraction efficiency, distinguishing manatees from less effective foregut fermenters despite their hindgut strategy.[54] In wild settings, this supports selective grazing on higher-quality plants, contrasting captive diets like romaine lettuce, which offer lower fiber and may alter microbial communities.[55]Reproduction and Development

Manatees display a promiscuous mating system characterized by polygyny, in which multiple males form mating herds around a single female in estrus, competing vigorously through pushing and shoving to gain access for copulation. These herds typically involve 5 to 20 males pursuing the female for durations of days to weeks, with the female often twisting and turning to select mates.[56][57] Breeding occurs opportunistically year-round in warm waters exceeding 20°C, without a defined season, as reproduction is closely tied to environmental temperature for calf survival.[58] Gestation in female manatees lasts 12 to 14 months, after which a single calf is typically born, though twins are documented in approximately 2% of cases based on observational records. Births occur in shallow, warm coastal waters, with the calf emerging tail-first and immediately surfacing to breathe. Calves remain dependent on maternal care, nursing for up to 18 months while gradually incorporating solid foods, though weaning is protracted and variable among individuals tracked via photo-identification.[4][5][59] Sexual maturity is attained by females around 7 years of age and by males at 9 to 10 years, though some males produce viable sperm as early as 2 to 3 years; successful breeding in females often begins between 7 and 9 years. Interbirth intervals average 2.5 to 3.5 years when calves survive to weaning, extending to 3 to 5 years under normal conditions, reflecting low reproductive rates observed in long-term studies of radio-tagged and photo-identified individuals in Florida.[56][37][5] Manatee fecundity is inherently low, with perinatal mortality from natural causes—such as dystocia, hypothermia, or maternal neglect—accounting for 20 to 30% of early calf losses in monitored populations, as evidenced by carcass salvage data and longitudinal observations. In the wild, average lifespan is 20 to 30 years due to cumulative natural factors, though individuals can exceed 50 years in protected environments like captivity.[34][59][60]Social Interactions and Intelligence

Manatees exhibit semi-solitary behavior, typically traveling alone or in transient groups of 2 to 6 individuals without forming stable pods or hierarchical structures observed in delphinids.[15] Loose aggregations of up to dozens or hundreds occur at resource hotspots like seagrass meadows or thermal springs, driven by environmental factors rather than social cohesion, with individuals joining and leaving freely.[40] Interactions are predominantly affiliative or neutral, featuring play such as barrel rolling or body-surfing, while aggression remains rare and limited mainly to male shoving during mating herds.[15] Cognitive assessments from field tracking and captive experiments reveal moderate intelligence, evidenced by robust spatial memory enabling navigation of intricate waterways and recollection of foraging or refuge sites over extended periods.[61] Manatees display associative learning, such as cue-response training, and rudimentary problem-solving, aligning with capabilities in phylogenetic relatives like elephants but falling short of cetacean complexity.[61] Absent are indicators of tool use or innovative manipulation in natural settings; instead, rapid habituation to human presence—approaching vessels or divers—demonstrates learned avoidance deficits that heighten injury risks without implying higher reasoning.[61] Vocal communication consists of simple acoustic signals including chirps, squeaks, and whistles, chiefly employed for mother-calf bonding and potentially mate attraction.[15] Calf isolation calls encode individual signatures via variations in fundamental frequency and duration, facilitating recognition and differing by sex (higher frequency in females) and age (shorter durations in juveniles).[62] Analyses indicate graded signal modulation in response to ambient noise but no dialects, cultural transmission, or syntactic elaboration per acoustic field recordings.[63]Distribution and Habitat

Global Range by Subspecies

The genus Trichechus comprises three extant species of manatees, with the West Indian manatee (T. manatus) further divided into two subspecies distinguished primarily by geographic separation and minor morphological differences. The Florida manatee (T. m. latirostris) occupies the northernmost extent of the genus's range in the southeastern United States, while the Antillean manatee (T. m. manatus) inhabits broader tropical waters across the Caribbean and adjacent mainland coasts. The West African manatee (T. senegalensis) and Amazonian manatee (T. inunguis) represent distinct species adapted to specific continental riverine and coastal systems.[2][16] The Florida manatee (Trichechus manatus latirostris) is restricted to coastal and inland waters of the southeastern United States, with core populations concentrated in Florida year-round. In winter, individuals aggregate in warm-water refuges along central and southern Florida's east and west coasts, while summer migrations extend northward to the Carolinas and westward to Louisiana and Texas, occasionally reaching as far as Massachusetts. Historical records indicate presence in additional southeastern states including Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and North Carolina, though current sightings outside Florida are sporadic and tied to seasonal warming. This subspecies marks the northern limit of manatee distribution, influenced by temperature constraints below 20°C.[64][65][6] The Antillean manatee (Trichechus manatus manatus) exhibits a patchy distribution across subtropical and tropical waters from northern Mexico southward to northeastern Brazil, encompassing the Gulf of Mexico's western coasts, Central American shorelines, the Greater and Lesser Antilles, and northeastern South America. Key areas include southern Texas, the Yucatán Peninsula, Puerto Rico, and coastal Venezuela to French Guiana, favoring shallow coastal lagoons, estuaries, and rivers. Unlike the Florida subspecies, populations here do not face the same cold-induced migrations but show localized fidelity to warm, brackish habitats.[50][66][16] The West African manatee (Trichechus senegalensis) ranges along the western African coast from the Senegal River in the north to the Cuanza River in Angola in the south, inhabiting rivers, estuaries, mangroves, and coastal marine waters. This distribution spans approximately 5,000 km of coastline, with inland penetration up to several hundred kilometers along major waterways like the Niger and Congo rivers, though populations are fragmented due to habitat barriers and human activity. Unlike congeners, it tolerates slightly more oceanic conditions but remains tied to sheltered, vegetation-rich shallows.[67][68] The Amazonian manatee (Trichechus inunguis), the only exclusively freshwater manatee species, occupies the Amazon River Basin across northern South America, including Brazil, Peru, Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, and Venezuela, covering an estimated 7 million square kilometers of riverine and floodplain habitats. It inhabits slow-moving rivers, oxbow lakes, and flooded forests, with records from the main Amazon channel to tributaries like the Orinoco, but avoids fast-flowing or highly turbid sections. This species does not venture into coastal or brackish environments, reflecting adaptations to permanent freshwater systems.[69][70]Environmental Preferences and Migration

Manatees select habitats in shallow coastal bays, rivers, estuaries, and connected waterways exceeding 1 meter in depth, prioritizing calm environments with water temperatures consistently above 20°C to prevent cold-induced physiological stress.[71][72] These preferences favor protected areas supporting seagrass beds over regions with strong currents, which hinder their energy-efficient locomotion.[73] Manatees demonstrate euryhaline tolerance, inhabiting fresh, brackish, and full-strength marine waters, yet they preferentially aggregate near freshwater inflows to access potable water essential for osmoregulation as mammals.[71][74][75] In subtropical and temperate zones, manatees exhibit seasonal migrations to natural thermal refuges during winter, such as Florida's Crystal River springs maintaining approximately 22°C, enabling survival when ambient coastal waters drop below lethal thresholds.[76][72] Satellite tracking data reveal consistent migratory routes and strong site fidelity, with individuals returning annually to designated warm-season foraging grounds and winter aggregation sites.[77] In consistently warm tropical habitats, movements adopt a more nomadic pattern aligned with seagrass availability rather than thermal gradients.[78]Ecology

Predation and Natural Mortality

Manatees face negligible predation in the wild, attributable to their large adult body size—often exceeding 400 kilograms—and preference for shallow, coastal habitats that limit encounters with potential predators.[40] Documented cases of predation are rare and primarily involve calves or juveniles; for example, shark attacks have been confirmed through bite marks on West Indian manatees, including a probable tiger shark incident in Puerto Rico.[79] Crocodilians such as alligators and crocodiles occasionally prey on young manatees in overlapping ranges, while anecdotal reports note jaguar attacks in some freshwater systems.[80] More recently, observations have recorded bottlenose dolphins aggressively attacking and killing manatee calves, an unusual intra-marine mammal predation event.[81] These incidents do not constitute a significant population-level threat, as evidenced by the absence of predation as a distinct mortality category in long-term monitoring data.[82] Natural mortality in manatees arises predominantly from environmental stressors and physiological limits rather than biotic interactions. Cold stress, induced by prolonged exposure to water temperatures below 20°C, represents a major cause, particularly affecting calves; analysis of Florida manatee subpopulations from 2001–2009 showed calf cold-stress mortality fractions ranging from 0.18 to 0.49 across regions, compared to 0.08–0.31 for adults.[83] This vulnerability stems from manatees' tropical evolutionary origins and limited thermoregulatory capacity, leading to emaciation and organ failure during severe winters.[82] Red tide blooms, caused by the dinoflagellate Karenia brevis (formerly Gymnodinium breve), drive episodic mass mortalities through neurotoxin inhalation and ingestion, with fractions up to 0.32 for adults and 0.23 for calves in southwest Florida during peak events.[83] Other natural causes encompass infectious and non-infectious diseases, perinatal complications, and accidents, collectively categorized as comprising baseline mortality independent of human influences.[82] Annual adult survival rates exceed 0.96 across monitored Florida subpopulations, underscoring that natural factors alone sustain viable populations absent anthropogenic pressures.[83]Ecosystem Role and Interactions

Manatees occupy a primary herbivore trophic position in coastal and riverine food webs, functioning as keystone grazers that crop seagrass blades to prevent overgrowth and maintain meadow balance.[84] [85] Their selective grazing favors shorter, diverse seagrass species over taller monocultures, enhancing habitat complexity for invertebrates and juvenile fish.[86] This activity indirectly curbs epiphytic algal accumulation on blades, reducing smothering that could degrade photosynthesis and oxygen levels in the ecosystem.[84] Manatee feces facilitate nutrient cycling by depositing processed organic matter rich in nitrogen and phosphorus back into sediments, stimulating microbial decomposition and seagrass regrowth.[87] [88] In floodplain systems like the Amazon, this fertilization boosts primary productivity, while in Caribbean seagrass beds, it supports localized eutrophication without exceeding natural thresholds under baseline population densities.[87] Interspecific interactions include commensal associations with remora fish such as Echeneis naucrates, which attach via suction-cup dorsal fins to glean parasites and food scraps from manatee skin, gaining mobility and protection without evident host detriment.[89] [90] Competition with dugongs remains negligible due to disjoint ranges—manatees in Atlantic and West African waters versus dugongs in Indo-Pacific realms—precluding resource overlap in seagrass foraging.[91] Manatees serve minimally as disease vectors, with low pathogen transmission rates to co-occurring species documented in field studies.[92] Population declines in manatee habitats correlate with seagrass loss from nutrient pollution, positioning them as indicators of water quality degradation, whereas observed recoveries in protected areas demonstrate ecosystem resilience to moderated anthropogenic pressures.[92] [93] [86]Physiological Vulnerabilities

Manatees possess limited thermoregulatory adaptations, rendering them highly vulnerable to cold stress when ambient water temperatures fall below 20°C for extended durations, which disrupts metabolic functions and can precipitate emaciation, immunosuppression, and death.[94] Prolonged exposure below 18°C exacerbates this risk, as their thin blubber layer—typically about 2.5 cm thick—provides insufficient insulation compared to more robustly adapted marine mammals.[64] Reproductive physiology further constrains population resilience, with females reaching sexual maturity around 7.5 years, a gestation period of 13 ± 1 months, and an average inter-calving interval of 3.5 years, typically yielding a single calf as twins occur rarely.[5] This low fecundity rate—effectively one offspring every 2–5 years—amplifies susceptibility to stochastic demographic events, as small perturbations can significantly impair recovery without external interventions.[95] Inherent disease vulnerabilities include infections from protozoan parasites like Toxoplasma gondii, which causes disseminated toxoplasmosis leading to morbidity and mortality in wild populations.[96] [97] Viral papillomatosis, induced by manatee papillomavirus (TmPV1), manifests as cutaneous lesions, with seroprevalence indicating widespread exposure that compromises epithelial integrity.[98] These pathogens exploit the manatee's aquatic lifestyle and limited immune diversity in immunoglobulin heavy chain variable regions, heightening overall infectious risk.[99] A basal metabolic rate suited to herbivory results in protracted recovery from physiological insults, including slow wound healing tied directly to energy intake limitations and reduced cellular repair efficiency.[100] [101] This sluggish regenerative capacity stems from their evolutionary adaptations for low-energy foraging, contrasting with the higher metabolic demands and agility of carnivorous cetaceans, which exhibit greater physiological robustness against injury and environmental stressors.[102]Conservation and Population Dynamics

Historical Population Changes