Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nuclear isomer

View on Wikipedia

| Nuclear physics |

|---|

|

A nuclear isomer is a metastable state of an atomic nucleus, in which one or more nucleons (protons or neutrons) occupy excited state levels (higher energy levels). "Metastable" describes nuclei whose excited states have half-lives of 10−9 seconds or longer[1], 100 to 1000 times longer than the half-lives of the excited nuclear states that decay with a "prompt" half-life (ordinarily on the order of 10−12 seconds). Some references recommend 5×10−9 seconds to distinguish the metastable half-life from the normal "prompt" gamma-emission half-life.[2]

The half-lives of a number of isomers are far longer than this and may be minutes, hours, or years. For example, the 180m

73Ta nuclear isomer survives so long (at least 2.9×1017 years[3]) that it has never been observed to decay spontaneously, and occurs naturally as a primordial nuclide, though uncommon at only 1/8000 of all tantalum. The second most stable isomer is 210m

83Bi, which does not occur naturally; its half-life is 3.04×106 years to alpha decay. The half-life of a nuclear isomer can exceed that of the ground state of the same nuclide, as with the two above, as well as, for example, 186m

75Re, 192m2

77Ir, 212m

84Po, 242m

95Am and multiple holmium isomers.

The gamma decay from a metastable state is referred to as isomeric transition (IT), or internal transition, though it resembles shorter-lived "prompt" gamma decays in all external aspects with the exception of the longer life. This is generally associated with a high nuclear spin change, or "forbiddenness", which would be required in gamma emission to reach the ground state; this is even more true of beta decays. A low transition energy both slows the transition rate and makes it more likely that only highly forbidden decays are available, so most long-lived isomers have a relatively low excitation energy above the ground state (in the extreme case of thorium-229m, low excitation alone causes the measurably long life). In 210m

83Bi, the forbiddenness of available beta and gamma decays is so high that alpha decay is observed exclusively, though even that is more slow than for the ground state. For most lighter isomers including 180m

73Ta, alpha decay is not practically available, but others are not quite so forbidden as those two.

The first nuclear isomer and decay-daughter system (uranium X2/uranium Z, now known as 234m

91Pa/234

91Pa) was discovered by Otto Hahn in 1921.[4]

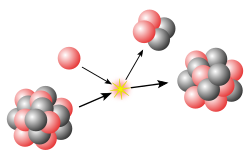

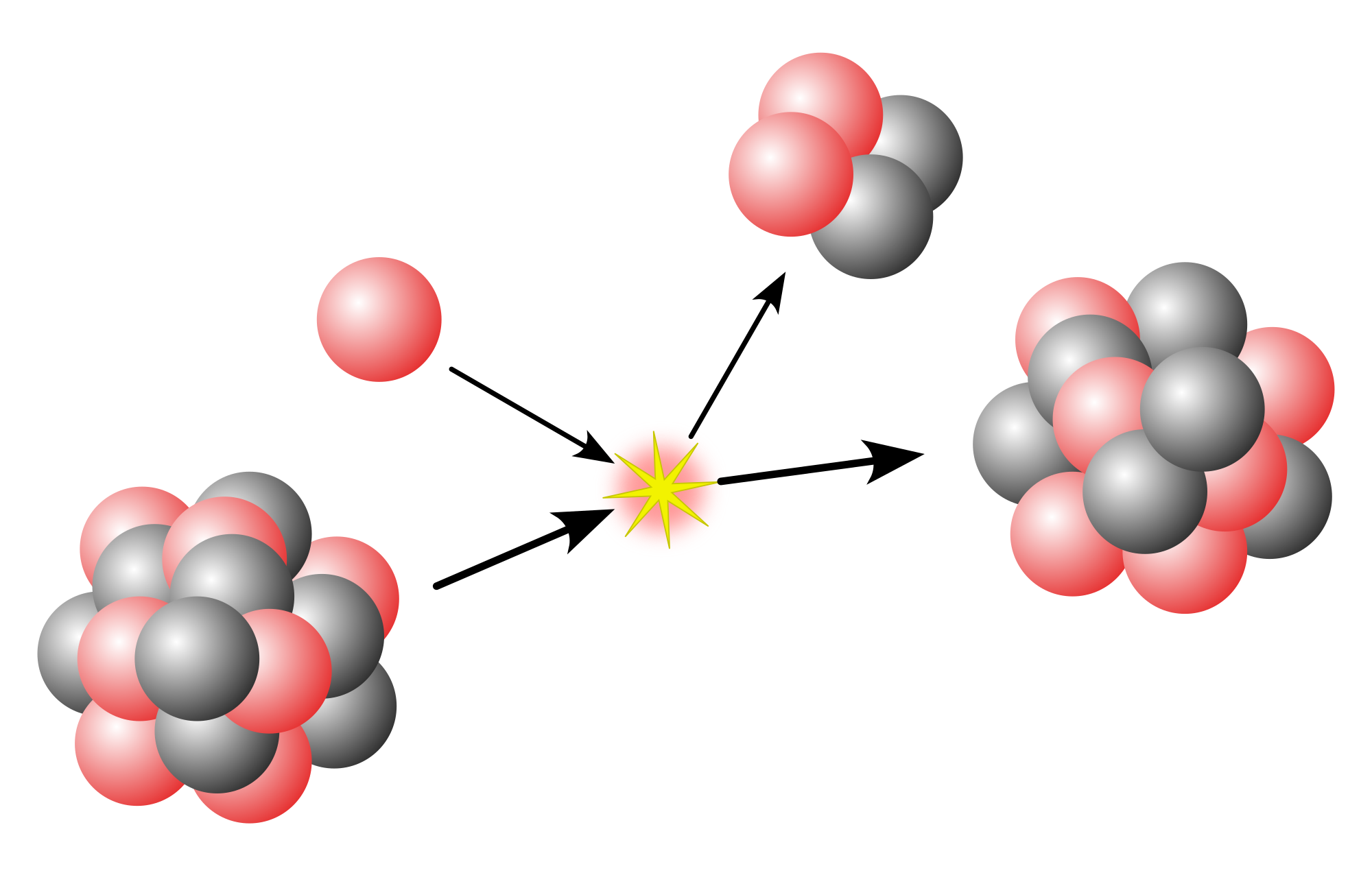

Metastable isomers can be produced through any nuclear reaction, including radioactive decay, neutron capture, nuclear fission, and bombardment by accelerated charged particles. A nucleus produced this way generally starts its existence in an excited state that loses its excess energy through the emission of one or more gamma rays or conversion electrons. This is normally a "prompt" process, but sometimes does not rapidly reach to the nuclear ground state, in which case a metastable isomer has formed. This usually occurs as a spin isomer when the formation of an intermediate excited state has a spin far different from that of the ground state. Gamma-ray emission is hindered if the spin of the post-emission state differs greatly from that of the emitting state, and if the excitation energy is low; such excited states will generally have long lives and be considered metastable.

After fission, several of the fission fragments may be produced in a metastable isomeric state, after their prompt de-excitation. At the end of this process, the nuclei can populate both the ground and the isomeric states. If the half-life of an isomer is long enough, it is possible to measure its production rate, and comparing it to that of the ground state gives the so-called isomeric yield ratio.[5]

A particular kind of metastable isomer is the fission isomer or shape isomer. Most actinide nuclei in their ground states are not spherical, but rather prolate spheroidal, with an axis of symmetry longer than the other axes, similar to an American football or rugby ball. This geometry can result in quantum-mechanical states where the distribution of protons and neutrons is so much further from spherical geometry that de-excitation to the nuclear ground state is strongly hindered. In general, these states either de-excite to the ground state far more slowly than a "usual" excited state, or they undergo spontaneous fission with half-lives of the order of nanoseconds or microseconds—a very short time, but many orders of magnitude longer than the half-life of a more usual nuclear excited state. Fission isomers may be denoted with a postscript or superscript "f" rather than "m", so that a fission isomer, e.g. of plutonium-240, can be denoted as plutonium-240f or 240f

94Pu.

Nomenclature

[edit]Metastable isomers of a particular isotope are usually designated with an "m". This designation is placed after the mass number of the atom; for example, cobalt-58m1 is abbreviated 58m1

27Co, where 27 is the atomic number of cobalt. For isotopes with more than one metastable isomer, "indices" are placed after the designation, and the labeling becomes m1, m2, m3, and so on. Increasing indices, m1, m2, etc., correlate with increasing levels of excitation energy stored in each of the isomeric states (e.g., hafnium-178m2, or 178m2

72Hf). The index may be omitted if only one isomer is relevant.

Nuclei of nuclear isomers

[edit]The nucleus of a nuclear isomer occupies a higher energy state than the non-excited nucleus existing in the ground state. In an excited state, one or more of the protons or neutrons in a nucleus occupy a nuclear orbital of higher energy than an available nuclear orbital. These states are analogous to excited states of electrons in atoms.

When excited atomic states decay, energy is released by fluorescence. In electronic transitions, this process usually involves emission of light near the visible range. The amount of energy released is related to bond-dissociation energy or ionization energy and is usually in the range of a few to few tens of eV per bond. However, a much stronger type of binding energy, the nuclear binding energy, is involved in nuclear processes. Due to this, most nuclear excited states decay by gamma ray emission. For example, a well-known nuclear isomer used in various medical procedures is 99m

43Tc, which decays with a half-life of about 6 hours by emitting a gamma ray of 140.5 keV energy; this is similar to the energy of medical diagnostic X-rays.

Nuclear isomers have long half-lives because their decay to the ground state is highly "forbidden" from the large change in nuclear spin required. For example, 180m

73Ta has a spin of 9 and the lower states have spins 1 and 2. Similarly, 99m

43Tc has a spin of 1/2 and the lower states 7/2 and 9/2.[6] Clearly, the latter is less "forbidden" and, as expected, much faster.

Nuclear transitions, including the 'isomeric' variety, occur not only through gamma-ray emission, but also internal conversion where the transition energy instead ejects an electron from the atom. The two process always compete, with gamma emission normally the most common, but as the proportion converted increases with lower energy and also with forbiddenness, it often becomes important for metastable isomers. In fact, the usual decay of 99m

43Tc involves conversion to the spin-7/2 state, then prompt gamma emission to the spin-9/2 ground state; similarly, 180m

73Ta could decay through conversion to the spin-2 state, followed by a gamma decay to the ground state. This gamma was looked for in [3], which assumed that to be the likely decay scheme, and not found.

In isotopes whose ground state is unstable, isomers can decay by the same modes rather than going to the ground state. Often both are seen, but rates can differ so much that only one is. Both isomers discussed just above have unstable ground states: 99

43Tc undergoes beta decay, though slowly (half-life 211 ky) due to forbiddenness, and the isomer, which is less so, beta-decays over 10,000 times faster (though still a small minority of decays); 180

73Ta can fall to either beta decay or electron capture, and quickly (half-life 8.15 h) as it is not forbidden, there the isomer is much more so to either as well as to isomeric transition, explaining its stability.

Artificial de-excitation

[edit]It was first reported in 1988 by C. B. Collins[7] that theoretically 180m

Ta can be forced to release its energy by weaker X-rays, although at that time this de-excitation mechanism had never been observed. However, the de-excitation of 180m

Ta by resonant photo-excitation of intermediate high levels of this nucleus (E ≈ 1 MeV) was observed in 1999 by Belic and co-workers in the Stuttgart nuclear physics group.[8]

178m2

72Hf is another reasonably stable nuclear isomer, with a half-life of 31 years and a remarkably high excitation energy for that life. In the natural decay of 178m2

Hf, the energy is released as gamma rays with a total energy of 2.45 MeV. As with 180m

Ta, it is thought that 178m2

Hf can be stimulated into releasing its energy. Due to this, the substance has been studied as a possible source for gamma-ray lasers, and reports have indicated that the energy could be released very quickly, so that 178m2

Hf can produce extremely high powers (on the order of exawatts).

Other isomers have also been investigated as possible media for gamma-ray stimulated emission.[2][9]

Other notable isomers

[edit]Holmium's nuclear isomer 166m1

67Ho has a half-life of 1,133 years, which is nearly the longest half-life of any holmium radionuclide. Only 163

Ho, with a half-life of 4,570 years, is more stable. Both the excitation energy of the former, and the decay energy of the latter, are less than 10 keV.

229m

90Th is a remarkably low-lying metastable isomer only 8.355733554021(8) eV above the ground state.[10][11][12] This low energy produces "gamma rays" at a wavelength of 148.3821828827(15) nm, in the far ultraviolet, which allows for direct nuclear laser spectroscopy. Such ultra-precise spectroscopy, however, could not begin without a sufficiently precise initial estimate of the wavelength, something that was only achieved in 2024 after two decades of effort.[13][14][15][16][17][11] The energy is so low that the ionization state of the atom affects its half-life. Neutral 229m

90Th decays by internal conversion with a half-life of 7±1 μs, but because the isomeric energy is less than thorium's second ionization energy of 11.5 eV, this channel is forbidden in thorium cations and 229m

90Th+

decays by gamma emission with a half-life of 1740±50 s.[10] This conveniently moderate lifetime allows the development of a nuclear clock of unprecedented accuracy.[18][19][12]

Mechanism of suppression of decay

[edit]- See also Selection rules for technical discussion.

The most common mechanism for suppression of gamma decay of excited nuclei, and thus the existence of a metastable isomer, is lack of a decay route for the excited state that will change nuclear angular momentum in any given step by 0 or 1 quantum unit (ħ) of spin angular momentum. This change is necessary to emit a gamma photon in an (electric dipole) allowed transition, as the photon has a spin of 1 unit. Changes of 2 or more units (any possible change is always integer) in angular momentum are possible, but the emitted photon must carry off the additional angular momentum. Changes of more than 1 unit are known as forbidden transitions. Each additional unit of spin larger than 1 that the emitted gamma ray must carry inhibits decay rate by about 5 orders of magnitude,[20] but this again increases at lower energies, and finally IC takes over, as can be seen in figures 14.61 and 14.62 of 'Quantum Mechanics for Engineers' by Leon van Dommelen[20]. From that it should be seen that the spin change of no less than 7 units that would occur in the hypothetical gamma decay of 180mTa should result in essentially total suppression and replacement by IC, in agreement with the above.

Gamma emission is impossible when the nucleus begins and ends in a zero-spin state, as such an emission would not conserve angular momentum. Internal conversion remains possible for such transitions.[20]

Applications

[edit]Hafnium[21][22] isomers (mainly 178m2Hf) have been considered as weapons that could be used to circumvent the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, since it is claimed that they can be induced to emit very strong gamma radiation. This claim is generally discounted.[23] DARPA had a program to investigate this use of both nuclear isomers.[24] The potential to trigger an abrupt release of energy from nuclear isotopes, a prerequisite to their use in such weapons, is disputed. Nonetheless a 12-member Hafnium Isomer Production Panel (HIPP) was created in 2003 to assess means of mass-producing the isotope.[25]

Technetium isomers 99m

43Tc (with a half-life of 6.01 hours) and 95m

43Tc (with a half-life of 61 days) are used in medical and industrial applications.

Nuclear batteries

[edit]

Nuclear batteries use small amounts (milligrams and microcuries) of radioisotopes with high energy densities. In one betavoltaic device design, radioactive material sits atop a device with adjacent layers of P-type and N-type silicon. Ionizing radiation directly penetrates the junction and creates electron–hole pairs. Nuclear isomers could replace other isotopes, and with further development, it may be possible to turn them on and off by triggering decay as needed. Current candidates for such use include 108Ag, 166Ho, 177Lu, and 242Am. As of 2004, the only successfully triggered isomer was 180mTa, which required more photon energy to trigger than was released.[26]

An isotope such as 177Lu releases gamma rays by decay through a series of internal energy levels within the nucleus, and it is thought that by learning the triggering cross sections with sufficient accuracy, it may be possible to create energy stores that are 106 times more concentrated than high explosive or other traditional chemical energy storage.[26]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ The standard reference Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S.; Audi, G. (2021). "The NUBASE2020 evaluation of nuclear properties" (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 45 (3) 030001. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/abddae. uses approximately 10-7 seconds

- ^ a b Walker, Philip M.; Carroll, James J. (2007). "Nuclear Isomers: Recipes from the Past and Ingredients for the Future" (PDF). Nuclear Physics News. 17 (2): 11–15. doi:10.1080/10506890701404206. S2CID 22342780.

- ^ a b Arnquist, I. J.; Avignone III, F. T.; Barabash, A. S.; Barton, C. J.; Bhimani, K. H.; Blalock, E.; Bos, B.; Busch, M.; Buuck, M.; Caldwell, T. S.; Christofferson, C. D.; Chu, P.-H.; Clark, M. L.; Cuesta, C.; Detwiler, J. A.; Efremenko, Yu.; Ejiri, H.; Elliott, S. R.; Giovanetti, G. K.; Goett, J.; Green, M. P.; Gruszko, J.; Guinn, I. S.; Guiseppe, V. E.; Haufe, C. R.; Henning, R.; Aguilar, D. Hervas; Hoppe, E. W.; Hostiuc, A.; Kim, I.; Kouzes, R. T.; Lannen V., T. E.; Li, A.; López-Castaño, J. M.; Massarczyk, R.; Meijer, S. J.; Meijer, W.; Oli, T. K.; Paudel, L. S.; Pettus, W.; Poon, A. W. P.; Radford, D. C.; Reine, A. L.; Rielage, K.; Rouyer, A.; Ruof, N. W.; Schaper, D. C.; Schleich, S. J.; Smith-Gandy, T. A.; Tedeschi, D.; Thompson, J. D.; Varner, R. L.; Vasilyev, S.; Watkins, S. L.; Wilkerson, J. F.; Wiseman, C.; Xu, W.; Yu, C.-H. (13 October 2023). "Constraints on the Decay of 180mTa". Phys. Rev. Lett. 131 (15) 152501. arXiv:2306.01965. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.131.152501. PMID 37897780.

- ^ Hahn, Otto (1921). "Über ein neues radioaktives Zerfallsprodukt im Uran". Die Naturwissenschaften. 9 (5): 84. Bibcode:1921NW......9...84H. doi:10.1007/BF01491321. S2CID 28599831.

- ^ Rakopoulos, V.; Lantz, M.; Solders, A.; Al-Adili, A.; Mattera, A.; Canete, L.; Eronen, T.; Gorelov, D.; Jokinen, A.; Kankainen, A.; Kolhinen, V. S. (13 August 2018). "First isomeric yield ratio measurements by direct ion counting and implications for the angular momentum of the primary fission fragments". Physical Review C. 98 (2) 024612. Bibcode:2018PhRvC..98b4612R. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.98.024612. ISSN 2469-9985. S2CID 125464341.

- ^ ENSDF data as compiled at National Nuclear Data Center. "NuDat 3.0 database". Brookhaven National Laboratory.

- ^ C. B. Collins; et al. (1988). "Depopulation of the isomeric state 180Tam by the reaction 180Tam(γ,γ′)180Ta" (PDF). Physical Review C. 37 (5): 2267–2269. Bibcode:1988PhRvC..37.2267C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.37.2267. PMID 9954706. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 January 2019.

- ^ D. Belic; et al. (1999). "Photoactivation of 180Tam and Its Implications for the Nucleosynthesis of Nature's Rarest Naturally Occurring Isotope". Physical Review Letters. 83 (25): 5242–5245. Bibcode:1999PhRvL..83.5242B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.5242.

- ^ "UNH researchers search for stimulated gamma ray emission". UNH Nuclear Physics Group. 1997. Archived from the original on 5 September 2006. Retrieved 1 June 2006.

- ^ a b Tiedau, J.; Okhapkin, M. V.; Zhang, K.; Thielking, J.; Zitzer, G.; Peik, E.; Schaden, F.; Pronebner, T.; Morawetz, I.; De Col, L. Toscani; Schneider, F.; Leitner, A.; Pressler, M.; Kazakov, G. A.; Beeks, K. (29 April 2024). "Laser Excitation of the Th-229 Nucleus". Physical Review Letters. 132 (18) 182501. Bibcode:2024PhRvL.132r2501T. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.132.182501. PMID 38759160.

- ^ a b Zhang, Chuankun; Ooi, Tian; Higgins, Jacob S.; Doyle, Jack F.; von der Wense, Lars; Beeks, Kjeld; Leitner, Adrian; Kazakov, Georgy; Li, Peng; Thirolf, Peter G.; Schumm, Thorsten; Ye, Jun (4 September 2024). "Frequency ratio of the 229mTh nuclear isomeric transition and the 87Sr atomic clock". Nature. 633 (8028): 63–70. arXiv:2406.18719. Bibcode:2024Natur.633...63Z. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07839-6. PMID 39232152.

The transition frequency between the I = 5/2 ground state and the I = 3/2 excited state is determined as: 𝜈Th = 1/6 (𝜈a + 2𝜈b + 2𝜈c + 𝜈d) = 2020407384335(2) kHz.

- ^ a b Conover, Emily (4 September 2024). "A nuclear clock prototype hints at ultraprecise timekeeping". ScienceNews.

- ^ von der Wense, Lars; Seiferle, Benedict; Laatiaoui, Mustapha; Neumayr, Jürgen B.; Maier, Hans-Jörg; Wirth, Hans-Friedrich; Mokry, Christoph; Runke, Jörg; Eberhardt, Klaus; Düllmann, Christoph E.; Trautmann, Norbert G.; Thirolf, Peter G. (5 May 2016). "Direct detection of the 229Th nuclear clock transition". Nature. 533 (7601): 47–51. arXiv:1710.11398. Bibcode:2016Natur.533...47V. doi:10.1038/nature17669. PMID 27147026. S2CID 205248786.

- ^ "Results on 229mThorium published in "Nature"" (Press release). Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. 6 May 2016. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ^ Seiferle, B.; von der Wense, L.; Thirolf, P.G. (26 January 2017). "Lifetime measurement of the 229Th nuclear isomer". Phys. Rev. Lett. 118 (4) 042501. arXiv:1801.05205. Bibcode:2017PhRvL.118d2501S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.042501. PMID 28186791. S2CID 37518294.

- ^ Thielking, J.; Okhapkin, M.V.; Przemyslaw, G.; Meier, D.M.; von der Wense, L.; Seiferle, B.; Düllmann, C.E.; Thirolf, P.G.; Peik, E. (2018). "Laser spectroscopic characterization of the nuclear-clock isomer 229mTh". Nature. 556 (7701): 321–325. arXiv:1709.05325. Bibcode:2018Natur.556..321T. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0011-8. PMID 29670266. S2CID 4990345.

- ^ Seiferle, B.; von der Wense, L.; Bilous, P.V.; Amersdorffer, I.; Lemell, C.; Libisch, F.; Stellmer, S.; Schumm, T.; Düllmann, C.E.; Pálffy, A.; Thirolf, P.G. (12 September 2019). "Energy of the 229Th nuclear clock transition". Nature. 573 (7773): 243–246. arXiv:1905.06308. Bibcode:2019Natur.573..243S. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1533-4. PMID 31511684. S2CID 155090121.

- ^ Peik, Ekkehard; Tamm, Christian (15 January 2003). "Nuclear laser spectroscopy of the 3.5 eV transition in 229Th" (PDF). Europhysics Letters. 61 (2): 181–186. Bibcode:2003EL.....61..181P. doi:10.1209/epl/i2003-00210-x. S2CID 250818523. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ Campbell, C.; Radnaev, A.G.; Kuzmich, A.; Dzuba, V.A.; Flambaum, V.V.; Derevianko, A. (22 March 2012). "A single ion nuclear clock for metrology at the 19th decimal place". Phys. Rev. Lett. 108 (12) 120802. arXiv:1110.2490. Bibcode:2012PhRvL.108l0802C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.120802. PMID 22540568. S2CID 40863227.

- ^ a b c Leon van Dommelen, Quantum Mechanics for Engineers, Section 14.20 Archived 5 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ David Hambling (16 August 2003). "Gamma-ray weapons". Reuters EurekAlert. New Scientist. Archived from the original on 27 October 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ^ Jeff Hecht (19 June 2006). "A perverse military strategy". New Scientist. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ^ Davidson, Seay. "Superbomb Ignites Science Dispute". Archived from the original on 10 May 2005.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ S. Weinberger (28 March 2004). "Scary things come in small packages". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011.

- ^ "Superbomb ignites science dispute". San Francisco Chronicle. 28 September 2003. Archived from the original on 15 June 2012.

- ^ a b M. S. Litz & G. Merkel (December 2004). "Controlled extraction of energy from nuclear isomers" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016.

External links

[edit]- Research group which presented initial claims of hafnium nuclear isomer de-excitation control. Archived 25 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine – The Center for Quantum Electronics, The University of Texas at Dallas.

- JASON Defense Advisory Group report on high energy nuclear materials mentioned in the Washington Post story above

- Bertram Schwarzschild (May 2004). "Conflicting Results on a Long-Lived Nuclear Isomer of Hafnium Have Wider Implications". Physics Today. Vol. 57, no. 5. pp. 21–24. Bibcode:2004PhT....57e..21S. doi:10.1063/1.1768663.

- Confidence for Hafnium Isomer Triggering in 2006. – The Center for Quantum Electronics, The University of Texas at Dallas.

- Reprints of articles about nuclear isomers in peer reviewed journals. – The Center for Quantum Electronics, The University of Texas at Dallas.

Nuclear isomer

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Basic Properties

A nuclear isomer refers to a metastable excited state of an atomic nucleus, distinct from the ground state by possessing excess internal energy yet exhibiting a significantly prolonged lifetime due to suppressed decay pathways.[1] This metastability arises when the excited configuration of nucleons—protons or neutrons in higher quantum states—results in low transition probabilities for de-excitation, primarily governed by electromagnetic selection rules involving angular momentum change, parity conservation, and multipolarity.[7] Unlike short-lived excited states that decay in femtoseconds to picoseconds via prompt gamma emission, isomers persist for times ranging from nanoseconds to billions of years, enabling their observation and study as discrete nuclear species.[8] Key properties include excitation energies typically spanning 10 keV to 5 MeV above the ground state, stored as potential energy in nuclear degrees of freedom such as single-particle orbitals or collective vibrations and rotations.[7] Half-lives vary widely, with common isomers having durations from microseconds to days; exceptional cases like ^{180m}Ta exhibit half-lives exceeding 10^{15} years, rendering it effectively stable under terrestrial conditions.[8] In standard nuclide notation, the 'm' superscript denotes the isomeric state, as in ^{99m}Tc, which has an excitation energy of 142 keV and a half-life of 6.01 hours, decaying primarily by isomeric transition to the ground state.[1] These states are characterized by specific quantum numbers, including spin (J) and parity (π), which dictate decay modes such as gamma emission, internal conversion electron ejection, or rarely beta decay if energetically feasible.[7] Nuclear isomers differ from atomic isomers or chemical isomers by residing in the nucleus rather than electron shells or molecular configurations, with energy scales orders of magnitude larger and decay independent of chemical environment.[1] Their existence underscores the quantized nature of nuclear energy levels, analogous to atomic spectra but influenced by the strong nuclear force and Pauli exclusion principle among nucleons.[8] Isomers occur across the nuclear chart but cluster in regions of deformed nuclei or near shell closures, where level densities and hindrance factors favor long-lived excitations.[7]Excitation and Energy Storage

Nuclear isomers are populated through nuclear reactions that excite the atomic nucleus into a metastable configuration, such as neutron capture reactions like (n,γ), charged-particle induced reactions including (p,n) or (α,n), or less commonly, photonuclear processes involving bremsstrahlung or laser-accelerated electrons. These mechanisms elevate one or more nucleons to higher single-particle orbitals or collective modes, with the resulting state possessing quantum numbers that impede prompt de-excitation. For instance, the ^{99m}Tc isomer, with an excitation energy of 140.5 keV and half-life of 6.01 hours, is routinely produced in reactors via the ^{98}Mo(n,γ)^{99}Mo → ^{99m}Tc decay sequence or direct (p,2n) reactions on molybdenum targets.[7] Similarly, high-spin isomers like the 8.4 MeV state in ^{212}Fr (half-life 34 μs, spin 34 ħ) arise from heavy-ion fusion-evaporation reactions that align nucleons in yrast configurations with elevated angular momentum.[9] The excitation energy, typically spanning 10 keV to 10 MeV, is stored as internal nuclear potential energy in deformed shapes, aligned spins, or forbidden transitions, where decay is suppressed by conservation laws for angular momentum, parity, or multipolarity. This metastability—defined arbitrarily as half-lives exceeding ~10 ns—contrasts with ordinary nuclear excitations that decay in ~10^{-15} s via electromagnetic or particle emission, enabling prolonged energy retention up to years or longer, as in ^{180m}Ta (>7.1 × 10^{15} years half-life at ~93 keV excitation).[10] Such storage arises causally from hindered γ-decay rates, governed by the Weisskopf single-particle estimate scaled by collective enhancements, where high multipole orders (e.g., E4 or higher) exponentially reduce transition probabilities.[11] Experimental atlases document over 2,450 such isomers, with energy systematics revealing clusters in deformed regions like rare-earth nuclei.[12] While nuclear isomers offer theoretically high energy densities (e.g., ~10^{10} J/kg for long-lived states, exceeding chemical fuels), practical storage and triggered release face barriers from low production yields and unverified de-excitation schemes, as assessed in studies of isomers like ^{178m2}Hf (2.45 MeV, 31-year half-life).[13] Emerging methods, including nuclear excitation by electron capture (NEEC) or laser-induced inverse internal conversion, aim to enhance population or control decay but remain experimental, with efficiencies below 10^{-4} in current setups.[14][15]Historical Development

Early Discovery

In 1921, Otto Hahn discovered the first nuclear isomer while investigating the radioactive decay chain of uranium-238 at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry in Berlin.[3] Hahn chemically separated emanation products from uranium salts, identifying a short-lived activity termed uranium X2 (UX2), with a half-life of approximately 1 minute, that decayed into a longer-lived species called uranium Z (UZ), with a half-life of about 6.7 hours.[16] Both UX2 and UZ exhibited identical chemical properties consistent with protactinium, yet displayed distinct radioactive decay characteristics, leading Hahn to conclude they represented anomalous states of the same element rather than separate isotopes.[3] To confirm these findings, Hahn processed over 100 kg of uranium mineral, isolating sufficient quantities to measure the weaker radiation of UZ, which was roughly 500 times less intense than comparable activities in the chain.[16] These observations, published that year, marked the initial experimental evidence of metastable nuclear states, though the underlying nuclear excitation mechanism remained unexplained until the development of quantum nuclear models in the 1930s.[17] Hahn's work built on earlier separations of uranium X (thorium-234) but uniquely revealed the isomeric pair in protactinium-234, where UX2 corresponds to the excited metastable state (234mPa) and UZ to the ground state (234Pa).[3] The discovery highlighted discrepancies in expected decay behaviors within natural radioactive series, prompting further scrutiny of nuclear stability. Prior theoretical speculation by Frederick Soddy in 1917 had anticipated isotopic variants with differing atomic weights but identical chemistry and potentially variable stability, yet Hahn's empirical isolation provided the concrete case that foreshadowed the isomer concept.[7] This early identification relied on meticulous radiochemical techniques, including precipitation and ionization measurements, without knowledge of nuclear shell structure or spin-parity effects that later rationalized the hindered transitions between states.[16]Key Experimental Milestones

In 1921, Otto Hahn conducted experiments on the decay products of uranium salts at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry in Berlin, observing two distinct beta-decay activities from thorium-234 leading to protactinium-234. One state, later identified as the ground state, had a half-life of approximately 6.7 hours, while the other, an excited isomeric state at about 1 MeV excitation energy, decayed with a half-life of 1.17 minutes primarily via internal conversion or gamma emission to the ground state. This marked the first experimental evidence of nuclear isomerism, though Hahn initially interpreted the activities as separate elements rather than metastable configurations of the same nucleus.[3][18] By 1935, further experiments in Germany and the Soviet Union confirmed the isomeric nature of such states through the detection of characteristic gamma-ray transitions linking the excited and ground states, establishing the mechanism of isomeric transitions (IT) as electromagnetic decays hindered by nuclear structure. These observations, involving detailed spectroscopy of decay chains in elements like iridium and bromine, demonstrated that the differing half-lives arose from inhibited de-excitation due to low transition probabilities rather than chemical differences.[7] Post-World War II advancements in nuclear reactors and early accelerators enabled systematic production and identification of numerous isomers. In the late 1940s and 1950s, neutron capture and fission experiments revealed long-lived high-energy isomers, such as the 2.45 MeV state in ^{178m2}\text{Hf} with a half-life exceeding 30 years, observed via delayed gamma spectroscopy following neutron irradiation. This isomer's exceptional stability highlighted energy storage potential and spurred studies into decay hindrance mechanisms.[19] In the 1960s, heavy-ion bombardment experiments at facilities like Dubna identified high-spin isomers, exemplified by the 1961 observation of a high-angular-momentum state in ^{242}\text{Am} with spin around 38 ħ, where collective rotation trapped the nucleus in a metastable configuration resistant to electromagnetic decay. These findings, using cyclotron-accelerated beams, classified a new type of isomerism driven by angular momentum conservation.[20] Modern milestones include the 1994 synthesis of the ^{270m}\text{Ds} isomer at GSI Darmstadt using fusion-evaporation reactions, notable as the first known case where the isomeric state (half-life 4 ms) outlived its ground state (0.2 ms), probing shell effects near the island of stability.[3]Classification and Types

Metastable Isomers

Metastable isomers are excited states of atomic nuclei with half-lives substantially longer than those of typical nuclear excitations, generally exceeding nanoseconds and extending up to years or more, due to inhibited decay pathways governed by quantum selection rules.[2] These states store excess energy in configurations such as high angular momentum or specific projections along the symmetry axis, suppressing electromagnetic transitions to the ground state.[7] The term "metastable" reflects their quasi-stable nature relative to rapid de-excitation, distinguishing them from short-lived resonances.[8] In nomenclature, metastable states are denoted by appending "m" to the mass number of the nuclide, such as ^{99m}Tc for technetium-99m, with additional superscripts (e.g., m2) for higher-lying isomers if multiple exist.[7] This designation highlights their observability as distinct species in experiments, often produced via neutron capture or charged-particle reactions. Half-lives arise inversely proportional to decay energy and transition multipolarity, enabling lifetimes from microseconds to geological timescales when low-energy, high-multipole transitions dominate.[21] Prominent examples include technetium-99m, featuring a 6-hour half-life and 140 keV excitation energy, generated from molybdenum-99 decay and utilized in over 40 million medical imaging procedures annually for its pure gamma emission.[7] Another is tantalum-180m, with a half-life exceeding 10^{15} years, rendering it effectively stable and the only naturally occurring metastable isomer in significant abundance.[19] These isomers provide insights into nuclear structure, with properties like spin-parity differences (e.g., even-even nuclei often having 0^+ ground and 2^+ first excited states) explaining decay hindrance.[22]| Isomer | Half-Life | Excitation Energy | Key Property |

|---|---|---|---|

| ^{99m}Tc | 6 hours | 140 keV | Medical isotope for SPECT imaging[7] |

| ^{180m}Ta | >10^{15} years | 93 keV | Natural occurrence, high stability[19] |

| ^{178m2}Hf | 31 years | 2.45 MeV | High-spin K-isomer, explored for energy storage[21] |

High-Spin and K-Isomers

High-spin isomers are metastable nuclear states with elevated total angular momentum quantum numbers I, where decay to lower-energy configurations is impeded by electromagnetic selection rules limiting the spin change ΔI to the multipolarity L of the transition (typically |ΔI| ≤ L, with low-L transitions dominating due to higher probabilities).[8] This hindrance is pronounced when the isomeric spin greatly exceeds that of accessible lower states, often requiring high-multipole transitions like E3 or M4, which have reduced rates compared to prevalent E2 or M1 decays.[8] Such isomers commonly arise in odd-A or odd-odd nuclei near closed shells, where ground-state spins are low (e.g., I = 1/2 or 0), or in high-spin yrast traps populated by heavy-ion fusion-evaporation reactions achieving rotational frequencies up to ħω ≈ 1 MeV.[23] Examples include high-spin states in heavy actinides like ^{250}Fm and ^{252}No, where multi-quasiparticle alignments sustain I > 40 ħ, with lifetimes extended by shape changes or pairing gaps at high rotation.[24] K-isomers occur in axially symmetric deformed nuclei, defined by a large projection quantum number K (0 < K ≤ I) of the total angular momentum along the body-fixed symmetry axis, arising from aligned single-particle orbitals or multi-quasiparticle configurations.[25] The approximate conservation of K—rooted in the nuclear potential's axial symmetry—hinders decays, as electromagnetic operators enforce ΔK = 0 for electric transitions (parity-conserving) or ΔK = ±1 for magnetic ones, necessitating either elevated multipolarities (e.g., E3 for ΔK = 0 with parity change) or admixtures via Coriolis or centrifugal forces to access low-K states like the ground band (K ≈ 0).[8] [25] Hindrance factors, quantifying suppression relative to unhindered Weisskopf estimates, often exceed 10^6 for high-K states, yielding half-lives from microseconds to years; for instance, in the A ≈ 170–190 rare-earth region, selected K ≈ 15/2–35/2 isomers exhibit factors up to 10^10 due to minimal mixing.[26] These isomers probe octupole deformation and shape coexistence, with excitation energies typically 1–3 MeV.[27] High-K isomers frequently overlap with high-spin cases, as maximal K approaches I in aligned configurations, enhancing dual spin and projection traps; a prototypical example is the ^{178m2}Hf state (I^π = 16^+, K = 16) at 2.446 MeV excitation, with a 31-year half-life attributed to combined high-spin and high-K hindrance in its four-quasineutron alignment.[28] Such states in deformed Hf–W isotopes, populated via (n,γ) or heavy-ion reactions, inform nuclear structure models like the particle-rotor framework, revealing prolate shapes and reduced pairing at high excitation.[28] In superheavy elements, high-K isomers may influence fission barriers and α-decay paths, though experimental access remains limited.[29]Shape Isomers and Nearly Stable States

Shape isomers represent a distinct category of nuclear isomers where the metastable excitation arises primarily from a substantial disparity in nuclear deformation between the isomeric and ground states, such as transitions between spherical, prolate, oblate, or superdeformed configurations. This structural mismatch impedes electromagnetic transitions by reducing wave function overlap and imposing a collective barrier, thereby extending lifetimes beyond typical excited states. Unlike spin or K-isomers dominated by single-particle effects, shape isomerism stems from macroscopic nuclear shape coexistence, often visualized as secondary minima in the potential energy surface calculated via macroscopic-microscopic models.[30][31] The archetype of shape isomers manifests as fission isomers in actinide nuclei (A ≈ 230–258), where the isomer populates a shallow second minimum at high elongation (axis ratio ≈ 2:1), predisposing it to spontaneous fission rather than gamma decay. Discovered in the early 1960s through observations of delayed fission fragments following neutron capture or Coulomb excitation, these isomers typically exhibit half-lives of 10^{-14} to 10^{-9} seconds, limited by tunneling through the fission barrier. Experimental confirmation involved time-of-flight measurements of scission neutrons and gamma rays, establishing their pre-fission saddle-point-like shapes distinct from ground-state prolate deformations.[32][33] Beyond actinides, shape isomers appear in lighter regions exhibiting extreme deformations, such as superdeformed bands in rare-earth nuclei (A ≈ 150–190) or oblate-prolate coexistences near N = 82 or Z = 82. Global surveys using deformed Woods-Saxon plus Strutinsky methods predict over 400 candidate ground-state-like shape isomers, concentrated in rare-earth (A ≈ 170–190), trans-lead (A ≈ 200–220), and actinide domains, with lifetimes enhanced by quadrupole or higher multipole hindrance. Detection challenges persist due to low production cross-sections and competing decays, but recent advances in heavy-ion fusion-evaporation reactions have identified candidates like high-spin shape isomers in ^{216}Rn (t_{1/2} ≈ months in potential second wells).[34][35] Nearly stable states among shape isomers emerge when shape barriers profoundly suppress all low-energy decay modes, yielding half-lives approaching or exceeding ground-state stabilities in marginal cases, particularly near proton or neutron drip lines where ground states are unbound or weakly bound. For instance, in neutron-deficient heavy nuclei, isomeric states in secondary wells may persist for seconds to years due to angular momentum alignment and deformation mismatches blocking internal conversion or fission. Such "ultra-long-lived" shape isomers challenge equilibrium assumptions in nucleosynthesis, as their persistence alters r-process branching ratios; theoretical extrapolations suggest prevalence in astrophysical environments with high deformation driving forces. Empirical examples remain scarce, with ongoing searches in facilities like GSI targeting A ≈ 100–150 regions for microsecond-to-hour isomers via precision gamma spectroscopy.[9][36]Underlying Physics

Factors Inhibiting Decay

The primary factors inhibiting the decay of nuclear isomers stem from quantum mechanical selection rules governing electromagnetic transitions, which dominate the de-excitation process from these metastable states to the ground state or lower excitations. Angular momentum conservation requires that the change in nuclear spin (ΔI) between initial and final states determines the minimum multipolarity (λ) of the emitted photon, with λ ≥ |ΔI|. High-spin isomers, where the excited state has a significantly larger spin than the ground state (e.g., ΔI up to 10 or more), necessitate high-multipole transitions such as electric quadrupole (E2) or octupole (E3/M3), whose decay rates scale approximately as (energy)^(2λ+1) times a hindrance factor, resulting in exponentially suppressed probabilities compared to dipole (E1/M1) transitions.[36][37] Parity selection further restricts transitions: even-parity changes favor electric multipoles (El), while odd-parity changes favor magnetic (Ml), and mismatches enforce higher λ, amplifying inhibition since higher multipoles carry less angular momentum per photon energy and couple weakly to the nuclear charge distribution.[36] For K-isomers, defined by a high projection of total angular momentum (K) along the nuclear symmetry axis in deformed nuclei, decay is additionally hindered by the ΔK=0 selection rule for single-photon transitions in axially symmetric systems. Non-zero ΔK requires admixtures of higher multipoles or collective vibrations to violate this rule, leading to K-hindrance factors (f_ν) often exceeding 10–100, where f_ν quantifies the suppression relative to unhindered expectations; this is evident in rare-earth region isomers like those in ^{178}Hf, where multi-quasiparticle K-states decay via highly forbidden E2/M2 channels with lifetimes extended to microseconds or longer due to poor overlap with lower-K states.[38][39] Pairing correlations and single-particle level gaps exacerbate this by minimizing Coriolis mixing, preserving high-K purity and further slowing internal conversion or gamma emission.[38] Shape isomers experience inhibition from structural mismatches, where the excited state occupies a secondary potential minimum with distinct deformation (e.g., prolate to oblate transition), impeding electromagnetic matrix elements that assume similar wavefunctions between states. This "shape hindrance" manifests in translead nuclei, where α-decay or fission barriers are altered, but gamma decay remains suppressed due to the need for collective mode excitations to bridge the configuration gap, as modeled in deformed potential energy surfaces; lifetimes can thus reach milliseconds despite modest energy storage (∼1–3 MeV).[40][41] In spin-gap isomers, large spin differences to all lower-lying states create a "gap" forbidding low-multipole paths, compounding angular momentum effects and yielding half-lives up to years in heavy nuclei.[42] These mechanisms collectively enable isomer lifetimes spanning 10^{-9} to 10^2 seconds or more, far exceeding typical nuclear excited states (∼10^{-15} s), by exploiting nuclear structure's rigidity against facile de-excitation.[8]Nuclear Structure Influences

The longevity and excitation energies of nuclear isomers are determined by nuclear structure elements such as single-particle orbitals in the shell model, collective deformations, spin-parity configurations, and pairing correlations. In spherical nuclei, shell-model calculations reveal that isomers emerge from multi-quasiparticle excitations or alignments of high-j orbitals near closed shells, where decay to lower states is impeded by angular momentum selection rules requiring high-multipole gamma transitions (e.g., E4 or higher). For instance, the high-spin 65/2⁻ isomer in ^{213}Fr at 8.09 MeV exemplifies alignment-driven hindrance in the lead region.[43][19] Deformation introduces the projection quantum number K along the symmetry axis, fostering K-isomers in axially symmetric nuclei where transitions with |ΔK| > 1 are suppressed for low-multipole orders, often necessitating hindered Eλ or Mλ decays with λ ≥ 4. The 31-year 16^+ isomer in ^{178}Hf, decaying via a K-forbidden E5 transition, illustrates this structural barrier arising from mismatched K values between initial and final states.[43][19] Shape isomers, conversely, stem from multiple minima in the deformation energy surface, enabling metastable oblate or superdeformed configurations separated by barriers from the ground-state prolate shape, predominantly in heavy actinides and rare-earth isotopes.[19] Pairing interactions, modeled via the BCS approximation or seniority scheme, stabilize low-seniority (paired) ground states, rendering higher-seniority excitations isomeric due to vanishing or reduced electromagnetic matrix elements, especially for E2 transitions in semi-magic nuclei mid-shell. Seniority isomers, characterized by v=3 or v=5 states conserving seniority, are prevalent in tin isotopes near N=73, where shell structure enhances selection-rule suppression, yielding lifetimes orders of magnitude longer than predicted without pairing considerations.[44][19] These structural factors collectively dictate isomer hindrance, with empirical data from regions like A ≈ 135 underscoring evolutionary changes toward shell closures.[45]Production and Observation

Natural and Astrophysical Sources

Tantalum-180m (^180mTa) is the sole nuclear isomer observed in significant quantities in natural terrestrial sources, comprising approximately 0.012% of naturally occurring tantalum.[7] [46] This isomer exhibits an extraordinarily long half-life exceeding 10^{15} years, far surpassing the age of the Earth and the universe, rendering it effectively stable under ambient conditions.[7] [21] Its presence in tantalum ores is attributed to primordial nucleosynthesis rather than ongoing production, as shorter-lived isomers decay too rapidly to accumulate naturally.[46] No other nuclear isomers persist in measurable abundances in Earth's crust or atmosphere due to their typical half-lives ranging from nanoseconds to years, insufficient for geological stability.[7] In astrophysical environments, nuclear isomers—termed "astromers" when their metastable states influence stellar processes—arise during nucleosynthesis in stars, supernovae, and neutron star mergers.[47] These high-temperature, high-density conditions populate excited nuclear states, where isomers can store energy on timescales relevant to reaction networks, altering isotopic abundances via delayed decays or thermal excitations.[48] For instance, ^180mTa forms primarily through the r-process in explosive astrophysical events, with its hindered decay enabling persistence and contributing to observed cosmic abundances of tantalum.[9] Similarly, isomers in nuclei like ^{26}Al, ^{85}Kr, ^{34}Cl, and ^{113}Cd act as branch points in s- and r-process pathways, influencing gamma-ray emissions from star-forming regions and heavy element production.[49] Extreme stellar conditions often destabilize isomers through thermal population of decay channels, but select high-spin or shape isomers resist rapid de-excitation, impacting nucleosynthetic yields. Observations of isomer-influenced signatures, such as ^{26}Al gamma lines, serve as tracers of galactic nucleosynthesis rates.[47]Laboratory Production Methods

Nuclear isomers are produced in laboratories through nuclear reactions that selectively populate long-lived excited nuclear states, often requiring high-intensity particle beams or radiation sources to achieve measurable yields. Traditional methods rely on neutron irradiation in nuclear reactors, where thermal or epithermal neutrons induce radiative capture reactions ((n,γ)) on target isotopes, forming compound nuclei that cascade to isomeric levels. For example, the spontaneously fissioning isomers ^{242m}Am and ^{244m}Am were generated by slow neutron capture on enriched ^{241}Am and ^{243}Am targets, respectively, with production cross sections measured relative to ground-state formation.[50] Similarly, short-lived xenon isomers such as ^{129m}Xe and ^{131m}Xe have been created via neutron activation of gaseous ^{128}Xe and ^{130}Xe targets in research reactors, followed by gamma spectroscopy to quantify yields.[51] Reactor-based production favors low-energy neutron spectra to enhance capture probabilities for isomers with angular momentum hindrance.[52] Charged-particle accelerators, including cyclotrons, synchrotrons, and linear accelerators, enable production via direct reactions such as (p,n), (d,p), or (α,n), where incident protons, deuterons, or alpha particles transfer energy and spin to the target nucleus. These facilities allow precise control over beam energy to target specific excitation pathways, often yielding isomers in heavy elements like hafnium or tantalum. In one case, the high-spin isomer ^{178m2}Hf (with a half-life of 31 years) was produced by bombarding natural hafnium with bremsstrahlung photons generated from a 4.5 GeV electron beam, demonstrating the role of high-energy electromagnetic interactions in populating K-forbidden states.[28] Accelerator methods typically require isotopic enrichment of targets to isolate isomer production and mitigate competing ground-state channels, with yields optimized through thick-target configurations.[53] Coulomb excitation represents a non-nuclear-contact technique, exploiting the virtual photon field from relativistic heavy ions or protons to excite collective nuclear modes, particularly effective for even-even nuclei with high-spin isomers. This method minimizes compound nucleus formation, preserving isomeric purity. Experiments using intermediate-energy beams have populated isomers in light nuclei like ^{18m}F (J^π=5^+), with cross sections extracted via γ-ray detection arrays.[54] Recent advances include femtosecond-scale pumping of isomers through laser-driven Coulomb excitation, where intense laser fields induce quivering motion in target electrons or ions, achieving excitation rates unattainable with conventional accelerators.[55] Such approaches have been theoretically extended to thorium isomers for precision spectroscopy.[56] Emerging laser-based techniques leverage plasma acceleration to generate ultrafast proton or electron bunches, enhancing isomer production efficiency for applications like nuclear batteries. Laser-induced bremsstrahlung or cluster interactions have produced isomers such as those in indium, with yields up to (5.8±0.8)×10^8 per shot in proof-of-principle experiments.[57] These methods offer compact alternatives to large-scale reactors or accelerators, though current intensities limit scalability compared to established facilities.[58] Detection post-production invariably involves time-resolved γ-ray or conversion electron spectroscopy to distinguish isomers from prompt decays.[59]Decay Mechanisms

Primary Decay Modes

The primary decay mode of nuclear isomers is the isomeric transition (IT), an electromagnetic process dominated by gamma-ray emission, where the excited nucleus releases excess energy as a high-energy photon to reach a lower-lying state, often the ground state.[60] This mode is characteristic of isomers due to their elevated excitation energies, typically ranging from tens of keV to several MeV, but transitions are hindered by nuclear selection rules on angular momentum change (ΔJ) and parity (π), favoring higher-order multipole radiations such as electric quadrupole (E2) or magnetic dipole (M1) over faster electric dipole (E1) decays.[61] For instance, the prominent ¹⁷⁸ᵐ²Hf isomer (E* ≈ 2.45 MeV, t½ ≈ 31 years) decays primarily via low-energy E3 gamma transitions, illustrating the suppression that defines isomeric stability.[62] Internal conversion competes directly with gamma emission, particularly for low-energy transitions (below ~100 keV) or high multipolarities, where the nucleus transfers excitation energy electromagnetically to an orbital electron, ejecting it and producing characteristic X-rays or Auger electrons from atomic relaxation.[63] The internal conversion coefficient (α), defined as the ratio of conversion events to gamma emissions, increases with decreasing transition energy and higher angular momentum differences, often dominating in K- or high-spin isomers where gamma decay is forbidden or slow; for example, in ²³⁹Pu isomers, conversion from inner shells (K, L) accounts for significant branching.[64] This process conserves the same multipolarity constraints as gamma decay but bypasses photon emission, making it a key alternative pathway without altering the nuclear charge or mass number. While electromagnetic modes prevail, particle emission such as beta decay (β⁻ or β⁺) or alpha decay can occur from isomers if the Q-value exceeds thresholds and branching ratios permit, though these are secondary for most cases due to comparable phase spaces with ground-state decays and the isomers' typical electromagnetic hindrance.[60] In fission isomers, like ²³⁶ᵐU (E* ≈ 2.6 MeV, t½ ≈ 100 ns), spontaneous fission competes with electromagnetic decay, with branching ratios around 10⁻⁵ for fission versus dominant IT cascades.[65] Overall, decay mode dominance reflects nuclear structure specifics, with empirical data from compilations confirming electromagnetic transitions in over 90% of known isomers with t½ > 10 ns.[66]Suppression and Lifetime Determinants

The lifetimes of nuclear isomers are primarily determined by the suppression of electromagnetic decay channels, particularly gamma emission, due to quantum mechanical selection rules governing transition probabilities.[67] The decay rate depends on the multipolarity L of the transition, where higher L values—required for large changes in angular momentum ΔI—result in exponentially slower rates, as the transition probability scales approximately as E^{2L+1}, with E being the transition energy.[27] Low-lying isomers, often with excitation energies below 1 MeV, experience additional suppression from this energy dependence, making even electric dipole (E1) or magnetic dipole (M1) transitions viable only if parity and spin changes align.[68] In deformed nuclei, K-isomers arise from high-projection states where the angular momentum component K along the symmetry axis differs significantly from the ground state, hindering decays via the ΔK selection rule: transitions with |ΔK| > L are forbidden or strongly suppressed for low-multipole radiation.[67] Hindrance factors, defined as the ratio of empirical to single-particle transition rates, can exceed 10^3 for such cases, extending lifetimes to microseconds or longer, as observed in rare-earth nuclei around A ≈ 160–190.[67] Pairing correlations and multi-quasiparticle configurations further modulate these factors by altering wavefunction overlaps, reducing matrix elements for de-excitation.[67] High-spin isomers, typically yrast states with spins I > 20 ħ, face suppression from the unavailability of intermediate states with compatible angular momentum, forcing high-L cascades that are collectively hindered.[21] Structural differences, such as mismatched single-particle orbitals or collective vibrations between initial and final states, contribute to wavefunction orthogonality, amplifying hindrance beyond pure selection rules.[68] While internal conversion can compete with gamma decay in neutral atoms, its suppression in highly charged ions—by factors up to 30 due to reduced electron density—can prolong bare-isomer lifetimes, as demonstrated in experiments with osmium isomers.[69] Beta decay remains negligible for most isomers unless Q-values permit and spin-parity favor it, underscoring electromagnetic processes as the dominant lifetime determinants.[27]Practical Applications

Medical and Diagnostic Uses

Technetium-99m (^{99m}Tc), the most widely utilized nuclear isomer in medicine, serves primarily in diagnostic imaging due to its 6-hour half-life and emission of a 140 keV gamma ray, which penetrates tissues effectively while minimizing radiation dose to patients and enabling high-resolution detection with gamma cameras.[7][70] This isomer accounts for approximately 80-85% of all nuclear medicine procedures globally, with tens of millions of scans performed annually, including over 40,000 daily in the United States alone.[71][70][72] In single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), ^{99m}Tc-labeled radiopharmaceuticals target specific organs or physiological processes, allowing visualization of function rather than just anatomy as in X-ray or MRI. Common applications include bone scintigraphy to detect metastases or fractures, myocardial perfusion imaging for coronary artery disease assessment, thyroid uptake studies for hyper- or hypothyroidism, and renal scans evaluating kidney function and obstructions.[73][74] Lung perfusion scans identify pulmonary embolism, while hepatobiliary imaging assesses liver and gallbladder disorders.[73] Nuclear isomers have limited roles in therapeutic applications, with ^{99m}Tc primarily diagnostic rather than treatment-oriented due to its decay primarily via isomeric transition to ^{99}Tc without significant beta emission for cell destruction. Emerging research explores photo-excitation of other isomers like ^{103m}Rh or ^{176m}Lu for potential targeted therapy, but none have achieved clinical adoption comparable to diagnostic uses.[75][76] Proposed alternatives such as ^{95g}Tc or ^{96g}Tc aim to address supply issues with ^{99m}Tc but remain experimental.[77]Energy Storage and Nuclear Batteries

Nuclear isomers possess excitation energies typically in the range of 0.1 to several MeV per nucleus, yielding theoretical energy densities on the order of 10^9 J/kg or higher, surpassing chemical batteries by six to nine orders of magnitude due to the nuclear binding scale versus electronic transitions.[13][78] This stems from the metastable nature of isomers, where excess nuclear energy remains trapped for extended periods—sometimes years or longer—before decaying via gamma emission or internal conversion.[79] In principle, such states could serve as a high-density medium for energy storage, with "charging" achieved by populating the isomer through processes like neutron capture, photon absorption, or electron capture, and "discharging" via stimulated de-excitation to release energy controllably.[80] The nuclear battery concept envisions converting released gamma radiation or conversion electrons into electrical power, potentially using scintillators, photovoltaics, or direct charge collection, enabling compact, long-duration power sources for applications like spacecraft or remote sensors.[81] For instance, the isomer ^{178m2}\mathrm{Hf}, with a 2.446 MeV excitation energy and 31-year half-life, has been highlighted for its storage potential, offering energy release rates tunable if decay could be triggered externally via lasers or X-rays.[13] Experimental efforts, such as those at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory on ^{180m}\mathrm{Ta}, have explored modulating decay rates with intense fields to simulate on/off switching, aiming for battery-like functionality.[82] Similarly, studies on ^{93m}\mathrm{Mo} isomers using laser-accelerated ions seek efficient production for depletion tests, underscoring pathways to scalable storage.[58]| Isomer Example | Excitation Energy (MeV) | Half-Life | Theoretical Energy Density Relative to Li-ion Batteries |

|---|---|---|---|

| ^{178m2}\mathrm{Hf} | 2.446 | 31 years | ~10^6 times higher |

| ^{180m}\mathrm{Ta} | 0.093 | >10^{15} years (ground state transition suppressed) | ~10^5 times higher |

| ^{93m}\mathrm{Mo} | 0.030 | 6.85 hours | ~10^4 times higher (shorter storage) |