Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

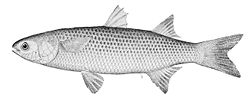

Mullet (fish)

View on Wikipedia

| Mullet Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Mugil cephalus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Mugiliformes |

| Family: | Mugilidae Jarocki, 1822 |

| Type species | |

| Mugil cephalus Linnaeus, 1758

| |

| Genera | |

|

See text. | |

The mullets or grey mullets are a family (Mugilidae) of ray-finned fish found worldwide in coastal temperate and tropical waters, and some species in fresh water.[1] Mullets have served as an important source of food in Mediterranean Europe since Roman times. In ancient Egypt, people ate pickled and dried mullet called fesikh.[2][3] The family includes about 78 species in 26 genera.[4]

Mullets are distinguished by the presence of two separate dorsal fins, small triangular mouths, and the absence of a lateral line organ. They feed on detritus, and most species have unusually muscular stomachs and a complex pharynx to help in digestion.[1]

Classification and naming

[edit]

Taxonomically, the family is placed in the order Mugiliformes, which is named after it.[5] Until recently, it was considered the only member of Mugiliformes, but more recent taxonomic treatments suggest that they are closely related to the Asiatic glassfishes (Ambassidae), which are now also placed in the group.[6] The presence of fin spines clearly indicates membership in the superorder Acanthopterygii, and in the 1960s, they were classed as primitive perciforms,[7] while others have grouped them in Atheriniformes.[8]

In North America, "mullet" by itself usually refers to Mugilidae. In Europe, the word "mullet" is usually qualified, the "grey mullets" being Mugilidae and the "red mullets" or "surmullets" being Mullidae, notably members of the genus Mullus.[9] Outside Europe, the Mullidae are often called "goatfish".[10] Fish with common names including the word "mullet" may be a member of one family or the other, or even unrelated such as the freshwater Catostomus commersonii.[11]

However, recent taxonomic work has reorganised the family and the following genera make up the Mugilidae:[12][4]

- Agonostomus Bennett, 1832

- Aldrichetta Whitley, 1945

- Cestraeus Valenciennes, 1836

- Chaenomugil Gill, 1863

- Chelon Artedi, 1763

- Crenimugil Schultz, 1946

- Dajaus Valenciennes, 1836

- Ellochelon Whitley, 1930

- Gracilimugil Whitley, 1941

- Joturus Poey, 1860

- Minimugil Durand, Chen, Shen, Fu & Borsa, 2012

- Mugil Linnaeus, 1758

- Myxus Günther, 1861

- Neomyxus Steindachner, 1878

- Neochelon Durand, Chen, Shen, Fu & Borsa 2012

- Oedalechilus Fowler 1903

- Osteomugil G. Luther, 1982

- Parachelon Durand, Chen, Shen, Fu & Borsa 2012

- Paramugil Ghasemzadeh, Ivantsoff & Aarn 2004

- Planiliza Whitley, 1945

- Plicomugil Schultz, 1953

- Pseudomyxus Durand, Chen, Shen, Fu & Borsa 2012

- Rhinomugil Gill, 1863

- Sicamugil Fowler, 1939

- Squalomugil Ogilby, 1908

- Trachystoma Ogilby, 1888

The oldest known fossil mullet is †Mugil princeps from the latest Oligocene-aged Aix-en-Provence Formation of France.[13][14]

Behaviour

[edit]A common noticeable behaviour in mullet is the tendency to leap out of the water. There are two distinguishable types of leaps: a straight, clean slice out of the water to escape predators and a slower, lower jump while turning to its side that results in a larger, more distinguishable, splash. The reasons for this lower jump are disputed, but have been hypothesised to be in order to gain oxygen rich air for gas exchange in a small organ above the pharynx.[15]

Development

[edit]The ontogeny of mugilid larvae has been well studied, with the larval development of Mugil cephalus in particular being studied intensively due to its wide range of distribution and interest to aquaculture.[16] The previously understudied osteological development of Mugil cephalus was investigated in a 2021 study, with four embryonic and six larval developmental steps being described in aquaculture-reared and wild-caught specimens.[16] These descriptions provided clarification of questionable characters of adult mullets and revealed informative details with potential implications for phylogenetic hypotheses, as well as providing an overdue basis of comparison for aquaculture-reared mullets to enable recognition of malformations.[16]

History

[edit]Mullet have historical significance globally, with record of consumption in ancient Rome[17] and Egypt.[18] Indigenous communities in Florida,[19] Hawaii[20], and North Carolina[21] also fished and consumed the fish from as far back as the 15th century. Early American commercial fishers in the 19th century dismissed mullet as a "trash fish" due to its low market value[22], and the fish fell out of fashion. In the 1960s, Florida state officials attempted to revive mullet through a marketing campaign to rename mullet as "lisa."[23]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Johnson, G.D. & Gill, A.C. (1998). Paxton, J.R. & Eschmeyer, W.N. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Fishes. San Diego: Academic Press. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-12-547665-2.

- ^ "The deadly dish people love to eat". 25 February 2022.

- ^ "Fesikh - Arca del Gusto".

- ^ a b "Family Mugilidae – Mullets". FishBase. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ Nelson, Joseph S.; Grande, Terry C.; Wilson, Mark V. H. (2016). Fishes of the World (5th ed.). Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons. doi:10.1002/9781119174844. ISBN 978-1-118-34233-6.

- ^ Fricke, R.; Eschmeyer, W. N.; Van der Laan, R. (2025). "ESCHMEYER'S CATALOG OF FISHES: CLASSIFICATION". California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2025-02-10.

- ^ Gosline, W. A. (1961) "The Perciform Caudal Skeleton" Copeia 1961(3): pp. 265–270

- ^ O.H. Oren (1981). Aquaculture of Grey Mullets. CUP Archive. p. 2. ISBN 9780521229265.

- ^ "Mullet species". britishseafishing.co.uk. 14 September 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ "Goatfish". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ "Common names of Catostomus commersonii". Fishbase. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ Jean-Dominique Durand; Wei-Jen Chen; Kang-Ning Shen; Cuizhang Fue; Philippe Borsaf (2012). "Genus-level taxonomic changes implied by the mitochondrial phylogeny of grey mullets (Teleostei: Mugilidae) (abstract)" (PDF). Comptes Rendus Biologies. 335 (10&11): 687–697. doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2012.09.005. PMID 23199637.

- ^ Neves, Jessika M. M.; Almeida, JoÃo P. F. A.; Sturaro, Marcelo J.; FabrÉ, Nidia N.; Pereira, Ricardo J.; Mott, TamÍ (2020-02-17). "Deep genetic divergence and paraphyly in cryptic species of Mugil fishes (Actinopterygii: Mugilidae)". Systematics and Biodiversity. 18 (2): 116–128. Bibcode:2020SyBio..18..116N. doi:10.1080/14772000.2020.1729892. ISSN 1477-2000.

- ^ Gaudant, Jean; Nel, André; Nury, Denise; Véran, Monette; Carnevale, Giorgio (2018-08-01). "The uppermost Oligocene of Aix-en-Provence (Bouches-du-Rhône, Southern France): A Cenozoic brackish subtropical Konservat-Lagerstätte, with fishes, insects and plants". Comptes Rendus Palevol. Lagerstätten 2: Exceptionally preserved fossils Lagerstätten 2 : fossiles à conservation exceptionnelle. 17 (7): 460–478. Bibcode:2018CRPal..17..460G. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2017.08.002. ISSN 1631-0683.

- ^ Hoese, Hinton D. (1985). "Jumping mullet — the internal diving bell hypothesis". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 13 (4): 309–314. Bibcode:1985EnvBF..13..309H. doi:10.1007/BF00002915. S2CID 35924254.

- ^ a b c Thieme, Philipp; Vallainc, Dario; Moritz, Timo (2021). "Postcranial skeletal development of Mugil cephalus (Teleostei: Mugiliformes): morphological and life-history implications for Mugiliformes". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 192 (4): 1071–1089. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa123.

- ^ Grout, James (April 7, 2025). "Encyclopaedia Romana".

- ^ RAWI Publishing (2025). "On the Menu in Ancient Egypt: Fish".

- ^ Walker, Karen (December 16, 2019). "Did the Calusa Have A "Great Fishery of Mullet"?".

- ^ Nishimoto 1, Shimoda 2, Nishiura 3, Robert T. 1, Troy E. 2, Lance K. 3 (2007). "Mugilids in the Muliwai: a Tale of Two Mullets" (PDF). Bishop Museum Bulletin in Cultural and Environmental Studies. 3: 143–156.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Tursi, Frank (2016). "Swansboro Area Mullet Fisheries".

- ^ Zacks, Michelle (December 2013). "From table to trash: the rise and fall of mullet fishing in southwest Florida".

- ^ Florida Memory (October 10, 2014). "A Mullet by Any Other Name".

Further references

[edit]- Sepkoski, Jack (2002). "A compendium of fossil marine animal genera". Bulletins of American Paleontology. 364: 560. Retrieved 2011-05-19.

- Eschmeyer, William N.; Fricke, Ron & van der Laan, Richard (eds.). "Genera in the family Mugilidae". Catalog of Fishes. California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 25 September 2020.