Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

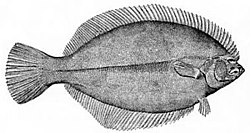

Halibut

View on Wikipedia

Halibut is the common name for three species of flatfish in the family of right-eye flounders. In some regions, and less commonly, other species of large flatfish are also referred to as halibut.

The word is derived from haly (holy) and butte (flat fish), for its popularity on Catholic holy days.[1] Halibut are demersal fish and are highly regarded as a food fish as well as a sport fish.[1][2][3][4]

Species

[edit]A 2018 cladistic analysis based on genetics and morphology showed that the Greenland halibut diverged from a lineage that gave rise to the Atlantic and Pacific halibuts. The common ancestor of all three diverged from a lineage that gave rise to the genus Verasper, comprising the spotted halibut and barfin flounder.[5]

- Genus Hippoglossus

- Atlantic halibut, Hippoglossus hippoglossus – lives in the North Atlantic

- Pacific halibut, Hippoglossus stenolepis – lives in the North Pacific Ocean

- Genus Reinhardtius

- Greenland halibut, Reinhardtius hippoglossoides – lives in the cold northern Atlantic, northern Pacific, and Arctic Oceans

Physical characteristics

[edit]The Pacific and Atlantic halibut are the world's largest flatfish, with debate over which grows larger.[6][7][8] Halibut are dark brown on the top side with a white to off-white underbelly and have very small scales invisible to the naked eye embedded in their skin.[9] Halibut are symmetrical at birth with one eye on each side of the head. Then, about six months later, during larval metamorphosis one eye migrates to the other side of the head. The eyes are permanently set once the skull is fully ossified.[10] At the same time, the stationary-eyed side darkens to match the top side, while the other side remains white. This color scheme disguises halibut from above (blending with the ocean floor) and from below (blending into the light from the sky) and is known as countershading.

The IGFA size record for halibut was apparently broken off the waters of Norway in July 2013 by a 234-kilogram (515-pound), 2.62-metre (8-foot-7-inch) fish. This was awaiting certification as of 2013.[11] In July 2014, a 219-kilogram (482 lb) Pacific halibut was caught in Glacier Bay, Alaska; this is, however, discounted from records because the halibut was shot and harpooned before being hauled aboard.[12]

Diet

[edit]Halibut feed on almost any fish or animal they can fit into their mouths. Juvenile halibut feed on small crustaceans and other bottom-dwelling organisms. Animals found in their stomachs include sand lance, octopus, crab, salmon, hermit crabs, lamprey, sculpin, cod, pollock, herring, and flounder, as well as other halibut. Halibut live at depths ranging from a few meters to hundreds of meters, and although they spend most of their time near the bottom,[1] halibut may move up in the water column to feed. In most ecosystems, the halibut is near the top of the marine food chain. In the North Pacific, common predators are sea lions, killer whales, salmon sharks and humans.

Sex-determining genes

[edit]Halibut species vary in sex determination systems.[13] The Atlantic halibut went down a purely XX/XY route, with the male being heterogametic, around 0.9 to 3.8 million years ago. The sex-determining gene for the Atlantic halibut is likely to be gsdf on chromosome 13.[13] The Pacific halibut went down a ZZ/ZW route, with the female being heterogametic, around 4.5 million years ago.[13][14] The master sex-determining gene of the Pacific halibut is located on chromosome 9 and it is likely to be bmpr1ba.[15] The gene sox2 is likely to play the same role in the Greenland halibut.

Halibut fishery

[edit]The North Pacific commercial halibut fishery dates to the late 19th century and today is one of the region's largest and most lucrative. In Canadian and US waters, long-line fishing predominates, using chunks of octopus ("devilfish") or other bait on circle hooks attached at regular intervals to a weighted line that can extend for several miles across the bottom. The fishing vessel retrieves the line after several hours to a day. The effects of long-line gear on habitats are poorly understood, but could include disturbance of sediments, benthic structures, and other structures.

International management is thought to be necessary, because the species occupies waters of the United States, Canada, Russia, and possibly Japan (where the species is known to the Japanese as ohyo), and matures slowly. Halibut do not reproduce until age eight, when about 80 cm (30 in) long, so commercial capture below this length prevents breeding and is against US and Canadian regulations supporting sustainability. Pacific halibut fishing is managed by the International Pacific Halibut Commission.

For most of the modern era, halibut fishery operated as a derby. Regulators declared time slots when fishing was open (typically 24–48 hours at a time) and fishermen raced to catch as many pounds as they could within that interval. This approach accommodated unlimited participation in the fishery while allowing regulators to control the quantity of fish caught annually by controlling the number and timing of openings. The approach led to unsafe fishing, as openings were necessarily set before the weather was known, forcing fishermen to leave port regardless of the weather. The approach limited fresh halibut to the markets to several weeks per year when the gluts would push down the price received by fishermen.[citation needed]

Individual fishing quotas

[edit]In 1995, US regulators allocated individual fishing quotas (IFQs) to existing fishery participants based on each vessel's documented historical catch. IFQs grant to holders a specific proportion of each year's total allowable catch (TAC). The fishing season is about eight months. The IFQ system improved both safety and product quality by providing a stable flow of fresh halibut to the marketplace. Critics of the program suggest, since holders can sell their quota and the fish are a public resource, the IFQ system gave a public resource to the private sector. The fisheries were managed through a treaty between the United States and Canada per recommendations of the International Pacific Halibut Commission, formed in 1923.

A significant sport fishery in Alaska and British Columbia has emerged, where halibut are prized game and food fish. Sport fisherman use large rods and reels with 35–70 kg (80–150 lb) line, and often bait with herring, large jigs, or whole salmon heads. Halibut are strong and fight strenuously when exposed to air. Smaller fish will usually be pulled on board with a gaff and may be clubbed or even punched in the head to prevent them from thrashing around on the deck. In both commercial and sport fisheries, standard procedure is to shoot or otherwise subdue very large halibut over 70–90 kg (150–200 lb) before landing them.[citation needed]

Overfishing and population decline

[edit]The Atlantic halibut has been a major target of fishing since the 1840s with overfishing causing the depletion of the species in the Georges Bank in 1850, then all the way up to the Canadian Arctic in 1866. In the 1940s the American fishing industry collapsed but the Canadian fishing industry remained until there was a decline in Canadian halibut fishery in the 1970s and 1980s. This allowed the halibut population to briefly rebound before collapsing in the 1990s. Since a low point in the early 2000s, the population has rebounded once again and may be stabilizing, but the species is not nearly as abundant in most locations as it was in the early 1800s.[16]

Atlantic halibut population

[edit]Currently, Atlantic halibut is managed as two stocks in Canadian waters, which are the Atlantic Continental Shelf stock and the Gulf of St. Lawrence stock.[17] The Atlantic halibut has two other stocks in the Northwest Atlantic, those being the Gulf of Maine-Georges Bank stock controlled by the United States and one controlled by France near the Saint-Pierre and Miquelon Archipelago. The Georges Bank stock is still considered to be depleted and it is listed as a species of concern in the United States.[16] In the two main populations of Atlantic halibut there are many subpopulations, but many have been lost due to patches of extreme overfishing and the populations remain depleted as a whole from what they were in the 1800s.

Pacific and Greenland halibut populations

[edit]The Pacific halibut and Greenland halibut have not had this level of fragmentation, and their population is far larger in the United States' waters, with North Pacific halibut and groundfish fisheries extracting the largest volume of catch out of all United States fishery areas.[18][19] Sometimes the California halibut is mistaken for a subspecies, but they are not, and are not even a true halibut species.[20] In the North Atlantic, observation of migration indicates that there are only two major populations of Greenland halibut that both stretch vast distances. Those populations being the Northeast one stretching from the Kara Sea to Greenland, and the Northwest one stretching from Newfoundland to Baffin Bay.[21] These stocks had been previously thought to be four different populations, but migration has indicated that they are only two different populations, and that fishing has not fragmented them. New research also indicates that the Greenland halibut originally came from the Pacific Ocean and spread into the Arctic Basin when the Bering Strait opened for a second time around 3 million years ago, and thus the Pacific halibut is its closest living relative.[22]

Evolutionary diversification of fragmented populations

[edit]In the Atlantic halibut studies have shown that the Atlantic Continental Shelf stock and the Gulf of St. Lawrence stock have begun to differentiate genetically from each other due to low connectivity between populations, low rates of exchange, and subsequent adaptation to local environments. Some adaptations can show up as changes in life-history trait parameters, which can change on a faster time scale than evolution and cause behavioural segregation. This can occur even in areas with enough genetic mixing to prevent genetic divergence.[16][17] One small but significant observed adaptation difference in the Atlantic halibut has been that the fish in the warmer Scotian Shelf have a faster growth rate than the halibut in the colder southern Grand Banks.[16] The Pacific halibut population remains largely genetically homologous throughout their range, but there is some variation of life-history traits on a geographic gradient.[16] Despite its large range, the populations of Greenland halibut remain largely homogenous due to a lack of barriers for gene flow between its four major populations.[19] There are small differences between subpopulations due to differing environmental factors, such as salinity and temperature gradients, but not to the degree seen in Atlantic halibut, as gene flow and migration continues throughout many different stocks.

As food

[edit]

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 380 kJ (91 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sugars | 0 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fiber | 0 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1.3 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

18.6 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | 80.3 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cholesterol | 49 mg | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[23] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[24] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Nutrition

[edit]Raw Pacific or Atlantic halibut meat is 80% water and 19% protein, with negligible fat and no carbohydrates (table). In a 100-gram (3+1⁄2-ounce) reference amount, raw halibut contains rich content (20% or more of the Daily Value, DV) of protein, selenium (65% DV), phosphorus (34% DV), vitamin D (32% DV), and several B vitamins: niacin, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12 (42–46% DV).

Cooked halibut meat – presumably through the resulting dehydration – has relatively increased protein content and reduced B vitamin content (per 100 grams), while magnesium, phosphorus, and selenium are rich in content.[25]

Food preparation

[edit]

Halibut yield large fillets from both sides of the fish, with the small round cheeks providing an additional source of meat.[26] Halibut are often boiled, deep-fried or grilled while fresh. Smoking is more difficult with halibut meat than it is with salmon, due to its ultra-low fat content. Eaten fresh, the meat has a clean taste and requires little seasoning. Halibut is noted for its dense and firm texture. Halibut have historically been an important food source to Alaska Natives and Canadian First Nations, and continue to be a key element to many coastal subsistence economies. Accommodating the competing interests of commercial, sport, and subsistence users is a challenge.

As of 2008, the Atlantic population was so depleted through overfishing that it might be declared an endangered species. According to Seafood Watch, consumers should avoid Atlantic halibut.[27] Most halibut eaten on the East Coast of the United States is from the Pacific.[citation needed]

In 2012, sport fishermen in Cook Inlet reported increased instances of a condition known as "mushy halibut syndrome". The meat of the affected fish has a "jelly-like" consistency. When cooked it does not flake in the normal manner of halibut but rather falls apart. The meat is still perfectly safe to eat but the appearance and consistency are considered unappetizing. The exact cause of the condition is unknown but may be related to a change in diet.[28][29]

Other species sometimes called "halibut"

[edit]- Of the same family (Pleuronectidae) as proper halibut

- Kamchatka flounder, Atheresthes evermanni – sometimes called "arrowtooth halibut"

- Roundnose flounder, Eopsetta grigorjewi – often called "shotted halibut"

- Greenland turbot, Reinhardtius hippoglossoides – often called "Greenland halibut"

- Spotted halibut, Verasper variegatus

- Family Paralichthyidae

- California flounder, Paralichthys californicus – sometimes called "California halibut"

- Olive flounder, Paralichthys olivaceus – sometimes called "bastard halibut"

- Family Psettodidae

- Psettodes erumei – sometimes called "Indian halibut"

- Family Carangidae (jack family, not a flatfish)

- Black pomfret, Parastromateus niger – sometimes called "Australian halibut"

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Uncle Ray (10 September 1941). "Right Eye of Halibut Moves Over to the left Side of Head". The Pittsburgh Press. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

The name "halibut" means "holy flatfish". It came from halibut being a popular food fish on holy days in England during early times.

- ^ Moira Hodgson (11 November 1990). "FOOD; Putting a Spotlight on Halibut". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

In England, halibut has always been popular...

- ^ "Follow Rules to Serve Fish Without Odor". The Milwaukee Journal. 11 February 1954. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

Fish can provide an economical main dish. Have boiled, baked or fried fish, or like most folks, choose cod, halibut, or ocean perch. They're the three most popular fish varieties

[permanent dead link] - ^ Ted Whipp (8 April 2009). "Fish and chips on Good Friday's menu". The Windsor Star. Archived from the original on 26 August 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2010.

He and his son ... expect hungry hordes, especially for the halibut, the most popular fish on the menu.

- ^ Vinnikov, Kirill A.; Thomson, Robert C.; Munroe, Thomas A. (2018). "Revised classification of the righteye flounders (Teleostei: Pleuronectidae) based on multilocus phylogeny with complete taxon sampling". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 125: 147–162. Bibcode:2018MolPE.125..147V. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2018.03.014. PMID 29535031. S2CID 5009041.

- ^ Orlov, A. M.; Kuznetsova, E. N.; Mukhametov, I. N. (2011). "Age and growth of the Pacific halibut Hippoglossus stenolepis and the size-age composition of its catches in the North-Western part of the Pacific Ocean". Journal of Ichthyology. 51 (4): 306–323. Bibcode:2011JIch...51..306O. doi:10.1134/S0032945211020068. S2CID 45475596.

- ^ The National Marine Fisheries Service / NOAA, Pacific Halibut Paragraph one, "About the Species."

- ^ The National Marine Fisheries Service / NOAA, Atlantic Halibut "Biology."

- ^ Pacific Halibut (Hippoglossus stenolepis), Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Adfg.state.ak.us. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- ^ "The Mysterious Origin of the Wandering Eye". ScienceBlogs. ScienceBlogs LLC. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ 515-Pound Halibut Caught By Marco Leibenow Near Norway May Be World Record Woods 'n Water Magazine, 19 August 2013.

- ^ "California man catches 482-pound halibut in Alaska". Associated Press. 11 July 2014. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ a b c Edvardsen, Rolf Brudvik; Wallerman, Ola; Furmanek, Tomasz; Kleppe, Lene; Jern, Patric; Wallberg, Andreas; Kjærner-Semb, Erik; Mæhle, Stig; Olausson, Sara Karolina; Sundström, Elisabeth; Harboe, Torstein; Mangor-Jensen, Ragnfrid; Møgster, Margareth; Perrichon, Prescilla; Norberg, Birgitta (8 February 2022). "Heterochiasmy and the establishment of gsdf as a novel sex determining gene in Atlantic halibut". PLOS Genetics. 18 (2) e1010011. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1010011. ISSN 1553-7404. PMC 8824383. PMID 35134055.

- ^ Einfeldt, Anthony L.; Kess, Tony; Messmer, Amber; Duffy, Steven; Wringe, Brendan F.; Fisher, Jonathan; den Heyer, Cornelia; Bradbury, Ian R.; Ruzzante, Daniel E; Bentzen, Paul (July 2021). "Chromosome level reference of Atlantic halibut Hippoglossus hippoglossus provides insight into the evolution of sexual determination systems". Molecular Ecology Resources. 21 (5): 1686–1696. Bibcode:2021MolER..21.1686E. doi:10.1111/1755-0998.13369. ISSN 1755-098X. PMID 33655659. S2CID 232101415.

- ^ Jasonowicz, Andrew J.; Simeon, Anna; Zahm, Margot; Cabau, Cédric; Klopp, Christophe; Roques, Céline; Iampietro, Carole; Lluch, Jérôme; Donnadieu, Cécile; Parrinello, Hugues; Drinan, Daniel P.; Hauser, Lorenz; Guiguen, Yann; Planas, Josep V. (October 2022). "Generation of a chromosome-level genome assembly for Pacific halibut ( Hippoglossus stenolepis ) and characterization of its sex-determining genomic region". Molecular Ecology Resources. 22 (7): 2685–2700. Bibcode:2022MolER..22.2685J. doi:10.1111/1755-0998.13641. ISSN 1755-098X. PMC 9541706. PMID 35569134.

- ^ a b c d e Shackell, Nancy L.; Fisher, Jonathan A. D.; den Heyer, Cornelia E.; Hennen, Daniel R.; Seitz, Andrew C.; Le Bris, Arnault; Robert, Dominique; Kersula, Michael E.; Cadrin, Steven X.; McBride, Richard S.; McGuire, Christopher H.; Kess, Tony; Ransier, Krista T.; Liu, Chang; Czich, Andrew (3 July 2022). "Spatial Ecology of Atlantic Halibut across the Northwest Atlantic: A Recovering Species in an Era of Climate Change". Reviews in Fisheries Science & Aquaculture. 30 (3): 281–305. Bibcode:2022RvFSA..30..281S. doi:10.1080/23308249.2021.1948502. ISSN 2330-8249. S2CID 238800003.

- ^ a b Kess, Tony; Einfeldt, Anthony L; Wringe, Brendan; Lehnert, Sarah J; Layton, Kara K S; McBride, Meghan C; Robert, Dominique; Fisher, Jonathan; Le Bris, Arnault; den Heyer, Cornelia; Shackell, Nancy; Ruzzante, Daniel E; Bentzen, Paul; Bradbury, Ian R (2021-10-09). Hauser, Lorenz (ed.). "A putative structural variant and environmental variation associated with genomic divergence across the Northwest Atlantic in Atlantic Halibut". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 78 (7): 2371–2384. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsab061. ISSN 1054-3139

- ^ Baetscher, Diana S.; Beck, Jessie; Anderson, Eric C.; Ruegg, Kristen; Ramey, Andrew M.; Hatch, Scott; Nevins, Hannah; Fitzgerald, Shannon M.; Carlos Garza, John (March 2022). "Genetic assignment of fisheries bycatch reveals disproportionate mortality among Alaska Northern Fulmar breeding colonies". Evolutionary Applications. 15 (3): 447–458. Bibcode:2022EvApp..15..447B. doi:10.1111/eva.13357. ISSN 1752-4571. PMC 8965376. PMID 35386403.

- ^ a b Wojtasik, Barbara; Kijewska, Agnieszka; Mioduchowska, Monika; Mikuła, Barbara; Sell, Jerzy (2021). "Temporal isolation between two strongly differentiated stocks of the Greenland halibut ( Reinhardtius hippoglossoides Walbaum, 1792) from the Western Barents Sea". Polish Polar Research: 117–138. doi:10.24425/ppr.2021.136603. hdl:20.500.12128/21254.

- ^ Vargas-Peralta, Carmen E.; Farfán, Claudia; Cruz, Fabiola Lafarga-De La; Barón-Sevilla, Benjamín; Río-Portilla, Miguel A. Del (18 December 2020). "Genoma mitocondrial completo del lenguado de California, Paralichthys californicus". Ciencias Marinas (in Spanish). 46 (4): 297–306–297–306. doi:10.7773/cm.v46i4.3121. ISSN 2395-9053. S2CID 234547077.

- ^ Vihtakari, Mikko; Elvarsson, Bjarki Þór; Treble, Margaret; Nogueira, Adriana; Hedges, Kevin; Hussey, Nigel E; Wheeland, Laura; Roy, Denis; Ofstad, Lise Helen; Hallfredsson, Elvar H; Barkley, Amanda; Estévez-Barcia, Daniel; Nygaard, Rasmus; Healey, Brian; Steingrund, Petur (2022-07-18). "Migration patterns of Greenland halibut in the North Atlantic revealed by a compiled mark–recapture dataset". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 79 (6): 1902–1917. doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsac127. ISSN 1054-3139.

- ^ Orlova, S. Yu.; Volkov, A. A.; Shcepetov, D. M.; Maznikova, O. A.; Chernova, N. V.; Chikurova, E. A.; Glebov, I. I.; Orlov, A. M. (1 January 2019). "Inter- and Intra-Species Relationships of Greenland Halibut Reinhardtius hippoglossoides (Pleuronectidae) Based on the Analysis of Nuclear and Mitochondrial Genetic Markers". Journal of Ichthyology. 59 (1): 65–77. Bibcode:2019JIch...59...65O. doi:10.1134/S0032945219010119. ISSN 1555-6425. S2CID 255280804.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 27 March 2024. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ "TABLE 4-7 Comparison of Potassium Adequate Intakes Established in This Report to Potassium Adequate Intakes Established in the 2005 DRI Report". p. 120. In: Stallings, Virginia A.; Harrison, Meghan; Oria, Maria, eds. (2019). "Potassium: Dietary Reference Intakes for Adequacy". Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. pp. 101–124. doi:10.17226/25353. ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. NCBI NBK545428.

- ^ "Fish, halibut, Atlantic and Pacific, cooked, dry heat per 100 grams". Nutritiondata.com by Conde Nast; version SR-21 of the USDA National Nutrient Database. 2018. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ "How to Fillet Halibut". Salmon University. 19 October 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- ^ "Monterey Bay Aquarium: Seafood Watch Program-All Seafood List". Monterey Bay Aquarium. Archived from the original on 18 April 2010. Retrieved 17 April 2008.

- ^ Smith, Brian Mushy halibut syndrome reported by Inlet fishermen Peninsula Clarion/Anchorage Daily News 30 June 2012

- ^ Alaska Department of Fish and Game Mushy Halibut Syndrome

Further reading

[edit]- Clover, Charles. 2004. The End of the Line: How overfishing is changing the world and what we eat. Ebury Press, London. ISBN 0-09-189780-7

- FishWatch – Pacific Halibut, Fisheries, US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2019

External links

[edit]- International Pacific Halibut Commission Archived 13 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Alaska Department of Fish & Game

Halibut

View on GrokipediaTaxonomy and Species

Primary Species

The halibut comprises large flatfishes in the family Pleuronectidae, known as right-eyed flounders due to the ocular migration where both eyes position on the right side in adults.[10] The name "halibut" originates from Middle English halybutte, combining haly ("holy") and butte ("flatfish"), reflecting its historical role as a food fish consumed on religious holy days.[11][12] The primary species are the Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus) and Pacific halibut (Hippoglossus stenolepis), both classified in the genus Hippoglossus based on shared morphological traits such as body shape, dentition, and scale patterns, corroborated by genetic analyses distinguishing them as separate species.[13][14] The Atlantic halibut attains maximum lengths of approximately 300 cm and weights exceeding 300 kg, positioning it among the largest flatfishes.[13][15] Pacific halibut reach up to 267 cm in length and over 200 kg, with females typically larger than males.[14][16] Greenland halibut (Reinhardtius hippoglossoides), while in the same family Pleuronectidae, belongs to a distinct genus and is taxonomically separated by differences in fin structure, pigmentation, and genetic markers, though it is commercially grouped with true halibuts due to similar fishery exploitation.Genetic and Evolutionary Aspects

Halibut exhibit low overall genetic diversity, consistent with large historical effective population sizes and minimal bottlenecks, as evidenced by allozyme surveys showing an average genetic distance of 0.0002 ± 0.0007 among Pacific halibut (Hippoglossus stenolepis) samples across broad geographic ranges, with 98.7% of total gene diversity residing within populations.[17] Genomic sequencing of the Pacific halibut genome, estimated at 602 Mb with chromosome-level assembly, further reveals structured variation despite this homogeneity, including subtle differentiation in peripheral stocks such as those in the [Aleutian Islands](/page/Aleutian Islands), attributable to limited gene flow rather than recent admixture.[18][19] Sex determination in halibut is primarily genetic, operating under a ZW heterogametic female system in Pacific halibut, where genome-wide association studies have identified sex-linked loci and a putative master sex-determining (MSD) gene candidate within a defined chromosomal region.[20][18] In Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus), quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping pinpoints a major sex-determining locus on linkage group 13, explaining significant phenotypic variance and supporting polygenic influences overlaid on primary genetic control, though environmental factors like temperature exert limited modulation compared to other flatfishes.[21] This genetic architecture underscores resilience to selection, as halibut maintain balanced sex ratios amid variable rearing conditions in aquaculture trials, without the pronounced temperature-dependent shifts seen in species reliant on sdY-like mechanisms.[20] Evolutionary divergence in halibut populations reflects post-glacial recolonization dynamics, with genomic scans detecting weak but significant structure in Atlantic halibut, including differentiation between Gulf of St. Lawrence cohorts and broader North Atlantic groups, driven by ancient structural variants and isolation in refugia during Pleistocene glaciations.[22] Similarly, Pacific halibut display fine-scale divergence in fragmented habitats, where oceanographic barriers post-glaciation fostered local adaptations without eroding baseline low diversity, enabling persistence under fluctuating pressures through standing variation rather than novel mutations.[19][23] This pattern aligns with causal inheritance from ancestral flatfish lineages, where bilateral asymmetry and metamorphosis genes predate genus-specific radiations, conferring robustness to demographic shifts.[18]Biology and Ecology

Physical Characteristics

Halibut belong to the family Pleuronectidae and display the typical flatfish asymmetry, with both eyes migrating to the right (dorsal) side during larval metamorphosis, enabling the fish to lie flat on the seafloor with the eyed side upward.[1] The body is strongly compressed laterally, featuring a large mouth equipped with strong, conical teeth and a concave caudal fin, while small, embedded scales provide a smooth skin texture.[1] This dextral orientation distinguishes them from left-eyed flatfish, and the ventral side remains unpigmented for camouflage. Females exhibit pronounced sexual dimorphism, attaining larger sizes than males; Pacific halibut (Hippoglossus stenolepis) reach maximum lengths of 2.5 m and weights over 200 kg, with rapid early growth slowing after several years. [24] Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus) similarly grow to 2.5 m and exceed 300 kg, with longevity surpassing 50 years in both species, though females often outlive males.[15] [2] Sensory adaptations include oversized eyes on the dorsal side, optimized for detecting prey in dim conditions, complemented by an arched lateral line system that senses hydrodynamic disturbances and vibrations from nearby organisms.[1] Chromatophores in the skin allow rapid color changes for substrate matching, enhancing ambush predation efficiency.[2]

Habitat and Distribution

Pacific halibut (Hippoglossus stenolepis) primarily inhabit the northeastern Pacific Ocean, extending from coastal waters off northern California northward through the Gulf of Alaska and into the Bering Sea.[1] Juveniles reside in shallow nearshore environments at depths of 10-70 meters and temperatures of 7-10.5°C, gradually migrating to deeper waters with age.[25] Adults occupy bathydemersal positions up to approximately 550 meters in depth during summer, occasionally reaching 900 meters, within cold temperate waters generally ranging from 4-10°C.[26][27] Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus) are distributed throughout the North Atlantic, ranging from the Gulf of St. Lawrence and Labrador southward to Virginia on the western side, and eastward across to Iceland and the Barents Sea. They exhibit similar bathydemersal lifestyles on sand, gravel, or clay substrates at depths from 50 to 2000 meters, with survey data indicating concentrations at 25-200 meters and temperatures of 4-13°C.[2] Both species favor soft sedimentary bottoms, such as mud and sand, which facilitate burial for ambush predation.[2] Halibut demonstrate migratory behaviors tied to life stages, with adults seasonally relocating from shallower summer feeding areas to deeper offshore sites for winter spawning.[1][28]Diet and Predation

Halibut exhibit a carnivorous diet that varies with ontogeny and habitat. Juvenile Pacific halibut (Hippoglossus stenolepis) in nearshore Alaskan waters primarily consume small crustaceans, including amphipods and copepods, with fishes comprising a minor portion during early summer months.[29] Adult diets shift to larger prey, dominated by fishes such as walleye pollock (Gadus chalcogrammus) and other gadoids, cephalopods including squid and octopuses, and crustaceans like Tanner crabs (Chionoecetes bairdi), which account for approximately 6% of stomach content weight in Gulf of Alaska samples.[30][31] Similarly, Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus) adults feed on fish, squid, and crabs, reflecting opportunistic predation in demersal environments.[32] Halibut employ an ambush predation strategy suited to their flattened morphology and benthic lifestyle. They lie camouflaged on the seabed, blending with substrates via mottled pigmentation on their eyed side, and detect prey visually before executing rapid strikes with powerful, asymmetrical jaws capable of crushing hard-shelled organisms.[33] This tactic targets schooling fishes and mobile invertebrates passing overhead or nearby, with feeding efficiency enhanced in low-light conditions where visual acuity remains effective down to irradiance levels of 10^{-4} μmol m^{-2} s^{-1}.[34] In demersal food webs, halibut function as apex predators, occupying a mean trophic level of approximately 4.0 based on aggregated diet studies across populations.[35] Stomach content analyses from Pacific halibut reveal fishes contributing 50-60% or more of diet biomass in deeper waters (>350 m), underscoring their role in regulating mid-trophic forage species like pollock, though cephalopods increase in importance at certain depths and sizes.[36] This predatory dominance positions halibut as key regulators in continental shelf ecosystems, with limited vulnerability to predation beyond early juvenile stages due to size and cryptic habits.[37]Reproduction and Life Cycle

Halibut reproduction occurs in deep offshore waters during winter and early spring, with spawning depths typically exceeding 200 meters. Pacific halibut (Hippoglossus stenolepis) spawn from November through March, peaking between late December and mid-January, while Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus) spawn from December to March, with peaks from late January to early February.[38][4] Females are batch spawners, releasing eggs in multiple events over the season to distribute risk, with males accompanying to fertilize externally.[39] Fecundity scales with female body size, ranging from 0.5 million eggs for smaller individuals (e.g., around 23 kg) to 4 million for larger ones (e.g., over 113 kg), reflecting an adaptive strategy to offset high early-life mortality.[1][7] Eggs are buoyant and pelagic, hatching after 12-20 days at temperatures of 5-8°C, yielding larvae approximately 6-7 mm in length.[1][40] The larval phase persists for 6-12 months, during which they drift in ocean currents, undergoing metamorphosis into juveniles before benthic settlement, a prolonged period marked by extreme vulnerability to predation and advection.[1] Sexual maturity is delayed, with males reaching it at 7-8 years (around 80 cm length) and females at 8-14 years (90-120 cm), often later in Atlantic populations.[24][2] This aligns with K-selected traits, including slow somatic growth, longevity exceeding 50 years, and extended generation times, which prioritize individual survival and quality over quantity of offspring despite high egg production.[41] Juvenile survival remains low, with empirical fisheries data indicating recruitment success from eggs to exploitable age below 1%, driven by density-independent factors like temperature and food availability during the pelagic stage, thus limiting population renewal to sporadic strong year classes.[42] These dynamics causally link high reproductive output to compensatory mechanisms against attrition, yet render populations sensitive to sustained adult removals before maturity cohorts replenish stocks.[4]Fisheries and Harvesting

Historical Development

Pacific halibut (Hippoglossus stenolepis) has been exploited for subsistence by indigenous coastal peoples of Alaska and the Pacific Northwest for centuries, using wooden or bone hooks to target the species in nearshore waters.[43] Similarly, Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus) supported indigenous and early European settler fisheries in Norwegian and North Atlantic coastal communities through hook-and-line methods, with records indicating targeted harvesting as part of mixed flatfish catches by the 18th century.[44] Commercial exploitation of Pacific halibut emerged in the late 19th century, with the first major fishery established in Alaska during the 1880s, driven by demand for fresh and salted product in East Coast U.S. markets; initial efforts involved sailing schooners deploying longlines from dories.[45] Sporadic commercial attempts date to 1870, but systematic operations scaled up post-1880 via schooner fleets homeporting in ports like Ketchikan by the early 1900s.[46] In Norway, early industrial halibut fishing paralleled this timeline, with hook-and-line vessels targeting Atlantic stocks for export by the 1880s, fueled by rail transport improvements enabling fresh market access.[44] By the early 20th century, unregulated expansion led to stock declines, prompting the U.S. and Canada to sign the Convention for the Preservation of the Halibut Fishery of the Northern Pacific Ocean and Bering Sea on March 2, 1923, establishing the International Pacific Halibut Commission (IPHC) as the first treaty for deep-sea fishery conservation; it entered force in 1924, implementing seasonal closures and research to rebuild biomass.[47] [44] IPHC management enabled catch expansions through the mid-century, with steam-powered vessels enhancing efficiency in longline operations; post-World War II, fisheries shifted further toward selective longlining over trawling to minimize waste and bycatch, sustaining booms into the 1980s when Pacific harvests peaked amid improved stock assessments and gear technology.[37] Atlantic fisheries followed analogous patterns, with longline dominance by the mid-1980s replacing earlier trawl-heavy phases in regions like the Norwegian Sea.[48]Management Frameworks

The International Pacific Halibut Commission (IPHC), established by a bilateral convention between the United States and Canada in 1923, serves as the primary regulatory body for Pacific halibut management, setting science-based total constant exploitable yields (TCEY) derived from annual stock assessments incorporating biomass estimates, recruitment data, and exploitation rates.[47] The IPHC's framework emphasizes sustainable harvest levels, with the 2025 TCEY fixed at 29.72 million pounds across regulatory areas 2A through 4E, reflecting precautionary adjustments to observed declines in mature female spawning biomass while targeting long-term yield stability.[49] This approach prioritizes empirical data over fixed quotas, allowing annual recalibration to maintain harvests near levels consistent with maximum sustainable yield (MSY) principles, where exploitation rates are adjusted to avoid overfishing as defined by spawning potential ratios. In the United States, particularly Alaska's fixed-gear fishery, the North Pacific Fishery Management Council recommended individual fishing quotas (IFQs) in 1991, with implementation by the National Marine Fisheries Service beginning in 1995, allocating harvest privileges as property-like rights to qualifying participants based on historical participation.[50] This market-oriented system replaced prior derby-style open seasons, which compressed effort into dangerously short periods—often just days—leading to high risks of vessel accidents, gear conflicts, and inefficient capital investment; post-IFQ, fishing seasons extended, fatality rates dropped markedly, and operational costs stabilized as fishers paced harvests to market conditions rather than racing competitors. Economically, IFQs enhanced revenues through quota leasing and transfers, fostering investment in quality processing and reducing discards, while the assignment of enduring rights incentivized conservation, evidenced by participants' support for compliance and lower violation rates compared to pre-IFQ eras.[51] Catch-sharing arrangements under the IPHC convention allocate portions of the TCEY between the two nations and domestic sectors (commercial, recreational, subsistence, and tribal), with U.S. plans specifying fixed percentages or pounds per area—such as Area 2A's division among Washington, Oregon, California, and tribal entities—enforced through bilateral adherence to monitored landings and overage penalties.[52] These mechanisms promote accountability by linking allocations to verifiable catch data, aligning incentives with MSY objectives through harvest control rules that cap exploitation when biomass falls below reference points, thereby sustaining yields without the volatility of unregulated effort.[53] Empirical outcomes include consistent quota attainment rates exceeding 90% in most areas post-implementation, underscoring the efficacy of rights-based approaches over command-and-control regulations in curbing excess capacity.[54]Commercial Operations

Commercial halibut harvesting relies predominantly on bottom longline gear, which deploys a primary line with hundreds to thousands of baited hooks targeting halibut on the seafloor. This method exhibits higher selectivity for legal-sized halibut compared to bottom trawling, as hooks capture fish actively biting bait, minimizing capture of undersized individuals and non-target species, thereby lowering bycatch rates to under 5% in directed Pacific halibut fisheries.[55][56][2] Operations in the primary Pacific halibut fishery, managed by the International Pacific Halibut Commission (IPHC), feature guided seasonal openings from March to July, with closures triggered by quota fulfillment in each regulatory area to prevent overharvest. The 2025 season commenced on March 20 across IPHC areas, while West Coast (Area 2A) directed commercial fisheries opened in June, concluding by July 24 after harvesting approximately 120 metric tons. Vessels are classified into categories A through H by length, from under 26 feet (Class H) to over 100 feet (Class A), determining eligibility and quota shares under individual transferable quota systems that allocate harvest rights based on historical participation.[52][57][58] Pacific halibut production is concentrated in Alaska and Canada, which together comprise 70-80% of global output, with Alaska's fisheries yielding the majority through longline deployments tracking catch per unit effort (CPUE) metrics such as standardized skate-per-set or weight-per-skate to assess gear efficiency and stock responsiveness. In recent assessments, Alaskan Area 2C CPUE has risen, indicating sustained productivity, while Area 3A metrics reflect stable but variable yields tied to biomass surveys.[59][60]Recreational and Subsistence Fishing

Recreational fishing for Pacific halibut features strict bag limits to manage localized harvests, typically one to two fish per day per angler depending on regulatory areas. In Alaska waters, the standard daily limit is two halibut of any size unless inseason restrictions apply.[61] Puget Sound regulations enforce a one-fish daily limit with no minimum size and a six-fish annual possession cap.[62] The 2025 Puget Sound recreational quota stood at 79,772 pounds, reflecting efforts to balance participation with stock sustainability.[62] Subsistence halibut fishing in Alaska targets rural residents and Alaska Native tribe members, requiring a Subsistence Halibut Registration Certificate (SHARC) for direct personal or family consumption, sharing, or customary trade.[63] This fishery preserves cultural practices in coastal communities, where halibut serves as a traditional staple for food and ceremonies without commercial intent.[64] Recreational harvests represent 10-15% of total removals across Pacific halibut management areas, influencing local population dynamics through angler participation and release practices.[28] The "Every Halibut Counts" program, developed by the University of Alaska Fairbanks Sea Grant, educates anglers on minimizing injury during catch-and-release to reduce post-capture mortality and support sustainable yields.[65]Conservation and Population Dynamics

Stock Assessments and Empirical Data

The International Pacific Halibut Commission (IPHC) conducts annual stock assessments for Pacific halibut (Hippoglossus stenolepis) using fishery-independent setline surveys, commercial catch data, and an ensemble of four age-structured population models to estimate exploitable biomass, spawning biomass, and recruitment.[66][67] The 2024 assessment determined that the stock is not overfished, with female spawning biomass estimated at 147 million pounds (66,678 metric tons), down from approximately 190 million pounds two years prior, reflecting a continuing decline since the late 1990s peak.[1][68] Recruitment indices from these models indicate fluctuations, with average recruitment estimated at 53-59% higher during favorable environmental conditions compared to unfavorable periods, though recent cohorts remain below historical highs.[67] In response to the 2024 assessment's projection of low biomass, the IPHC set 2025 coastwide total allowable catch (TAC) at 29.72 million pounds (13,483 metric tons), a reduction exceeding 15% from the 2024 level of 35.25 million pounds, prioritizing harvest rates aligned with model-recommended constants for sustainability.[69] Exploitable biomass indices from IPHC surveys show a post-2012 stabilization following earlier declines, with harvest occurring at levels deemed appropriate by the models despite the downward spawning biomass trend.[70] For Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus), assessments by agencies including Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) and the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization (NAFO) rely on stratified random surveys and biomass indices to evaluate stock status, often finding exploitable biomass below reference targets but demonstrating stability under quota regimes.[71] In the Gulf of St. Lawrence (NAFO 4RST), the 2024-2025 update reported a three-year mean exploitable biomass index supporting TAC advice, with stocks managed to avoid further depletion through closed-loop simulation modeling.[72][73] NAFO-area assessments similarly indicate persistent low biomass relative to targets but no acute collapse, with recruitment variability tracked via survey data informing annual quotas.[74]Management Successes and Property Rights Approaches

The implementation of individual fishing quotas (IFQs) in the Alaska Pacific halibut fishery in 1995 marked a shift toward property rights-based management, assigning fishermen exclusive, transferable shares of the total allowable catch (TAC) set by the International Pacific Halibut Commission (IPHC).[75] This approach ended the prior "race to fish" derby style, extending the season from days to eight months and aligning incentives for long-term stewardship over short-term maximization.[76] Empirical outcomes included reduced lost gear and ghost fishing, with reports indicating lost gear became rare and associated mortality minimal due to decreased competitive haste.[77] IFQs enhanced economic efficiency by lowering operational costs through optimized fleet utilization and steady supply chains, while catch per unit effort (CPUE) rose and discards fell, reflecting improved handling and selectivity.[77] Compliance strengthened, with TACs not exceeded in the initial five years, fostering stock stability in quota-allocated areas via data-informed harvest controls rather than blanket restrictions.[77] Property rights embedded in IFQs promoted causal stewardship, as quota holders bore the opportunity cost of overexploitation, evidenced by sustained biomass levels contrasting pre-IFQ volatility.[78] The IPHC's TAC framework, operational since the 1920s but refined post-IFQ, has demonstrably averted overexploitation by capping harvests based on annual surveys and models estimating exploitable biomass.[79] This adaptive, science-driven policy maintained population stability for decades, enabling recoveries in surveyed cohorts through precise, enforceable limits that incentivized participation in monitoring.[79] Unlike unregulated eras prone to boom-bust cycles, TACs integrated property-like exclusivity via IFQs, yielding verifiable gains in resource resilience and harvest predictability.[51]Challenges Including Bycatch and Allocation Disputes

Halibut fisheries encounter significant challenges from bycatch in non-directed groundfish trawl operations, where incidental capture exceeds prohibited species catch (PSC) limits, necessitating discards that result in economic waste. In the Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands, the 2025 PSC limit for the Amendment 80 trawl sector stands at 1,309 metric tons, a reduction from prior years to curb mortality of undersized or non-commercial halibut.[80][81] These limits, enforced by the North Pacific Fishery Management Council, halt directed fishing when reached, but historical data indicate persistent discards, with trawl bycatch mortality reaching peaks like 17.5 million pounds in 1990 before caps were tightened.[44] Such waste undermines resource utilization, as discarded halibut—often viable for harvest in directed fisheries—contributes to forgone revenue without benefiting food security or markets.[82] Allocation disputes between commercial, recreational, and subsistence sectors exacerbate inefficiencies, with evidence suggesting imbalances favor less productive uses amid fixed total allowable catches. In Alaska, the Catch Sharing Plan allocates portions of the Pacific halibut quota, but growth in charter and private recreational demand has prompted reallocations, such as quota transfers from commercial individual fishing quotas (IFQs) to sport sectors via leasing programs initiated around 2016.[83][84] Commercial operators argue that recreational allocations, which prioritize catch-and-release or limited retention, yield lower overall biomass harvest efficiency compared to directed longline fisheries optimized for maximum sustainable yield.[85] These tensions, evident in British Columbia where similar intersector conflicts have stalled cooperative solutions, highlight how static allocations ignore differential sector productivity, potentially inflating operational costs and reducing net economic returns from the fishery.[86] Empirical assessments indicate that fishing pressure, rather than climate variability alone, drives controllable declines in halibut metrics like size-at-age, underscoring the efficacy of harvest controls over exogenous factors. Pacific halibut size-at-age has fallen markedly—from over 120 pounds for 20-year-olds in 1988 to under 45 pounds by 2013—attributable more to density-dependent effects from exploitation than isolated temperature shifts.[87] While interannual temperature variability influences somatic growth and recruitment, stock assessments by the International Pacific Halibut Commission prioritize adjustable harvest rates to buffer against such fluctuations, as evidenced by stabilized cohorts under quota reductions despite ocean warming.[88] This causal emphasis on anthropogenic harvest enables targeted management, distinguishing it from less malleable climate drivers, though integrated models reveal synergies where overfishing amplifies environmental stressors.[89]Regional Population Trends

The Pacific halibut (Hippoglossus stenolepis) stock has declined coastwide since the late 1990s, with continuous reductions in biomass through approximately 2012 and ongoing low levels in subsequent years, including a drop in estimated female spawning biomass to 147 million pounds in the 2024 assessment.[70][66] Despite these trends, the stock is not overfished, as determined by the 2024 integrated stock assessment, which incorporates fishery-dependent and independent data.[1] The International Pacific Halibut Commission set 2025 total allowable catch quotas at reduced levels—reflecting persistent recruitment shortfalls and low juvenile abundance—to maintain sustainability amid a 40% probability of further stock decline.[90][91] Atlantic halibut (Hippoglossus hippoglossus) populations in U.S. and Canadian waters, including the Gulf of Maine and divisions 4RST in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, persist at low levels well below target biomass thresholds but show signs of slow recovery under restrictive management.[2][92] The 2024 management track assessment for the northwestern Atlantic coast updated indices of abundance through 2023, indicating stable but subdued trends with fishing mortality controlled to support gradual rebuilding.[92] In Canadian areas like 4RST, total allowable catches increased by 25% for the 2024-2025 season, signaling cautious optimism based on recent survey data and recruitment indices, though full recovery remains protracted due to the species' slow growth and historical overexploitation.[93] Greenland halibut (Reinhardtius hippoglossoides) stocks in Arctic and Northwest Atlantic regions, such as NAFO Subarea 1 and divisions 4RST, have maintained stable biomass over the past 20 years, consistently above levels associated with maximum sustainable yield.[94][93] Fishing mortality rates have remained below reference points for maximum sustainable yield throughout this period, with 2024 assessments projecting no medium-term decline below limit biomass thresholds, attributable to lower harvest pressure and the species' deep-water distribution limiting exploitation intensity relative to shallower-water congeners.[94][95]Economic and Cultural Significance

Commercial Value and Market Dynamics

Commercial landings of Pacific halibut in 2023 totaled approximately 22 million pounds, valued at $90 million ex-vessel, underscoring its dominant role in North American fisheries compared to the much smaller Atlantic halibut sector, where U.S. landings reached 77,800 pounds valued at $493,500.[1][2] These values reflect quota-driven harvests, with Pacific allocations managed under the International Pacific Halibut Commission, contributing to broader Alaska seafood ex-vessel revenues exceeding $2 billion annually, though halibut specifically drives premium pricing due to its size and quality.[96] Halibut enters international markets primarily as fresh or frozen fillets, with major export destinations including the European Union and Asian countries such as Japan, China, and South Korea, where demand for high-value whitefish sustains trade volumes.[97] In South Korea, halibut is imported primarily from the North Pacific or Atlantic regions and is regarded as a premium, high-priced seafood item, though less common than locally produced flatfish such as the olive flounder. Ex-vessel prices typically range from $5 to $10 per pound, influenced by supply constraints; for instance, 2025 Pacific quotas were reduced by 18% to 19.7 million pounds commercially, leading to elevated prices amid slower initial landings and tighter availability.[98][99] Such fluctuations demonstrate causal links between biomass assessments, quota reductions, and market premiums, as lower supply volumes amplify value per unit without corresponding demand contraction. Processing occurs mainly in Alaska and Canada, where facilities handle filleting and freezing to meet export standards, supported by traceability systems under Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) certification for U.S. North Pacific and Canadian Atlantic fisheries.[100][101] This certification facilitates premium market access by verifying sustainable sourcing, reducing risks from overfishing claims and enabling chain-of-custody tracking from vessel to consumer, which bolsters economic stability in volatile global seafood trade.[102]Contributions to Local Economies

The Pacific halibut fishery drives multiplier effects in local economies, amplifying initial landings through processing, supply chains, and consumer spending. In 2019, each dollar (or equivalent in Canadian dollars) of commercial Pacific halibut landings generated more than four dollars in total economic output across the United States and Canada, encompassing direct harvest value, indirect business inputs, and induced household expenditures.[103] This ratio, derived from multiregional input-output modeling, highlights cross-jurisdictional flows benefiting coastal harvest regions and inland processing and distribution hubs.[104] In Alaska, halibut fishing integrates into the broader seafood sector, supporting employment in vessel crews, processing plants, and ancillary services in rural communities. The state's seafood industry, including halibut contributions, sustained 37,400 full-time equivalent jobs and $2.2 billion in labor income in 2019, with halibut's role evident in its share of ex-vessel values and associated shoreside activities.[105] The commercial halibut fleet alone generated an estimated $325 million in total U.S. economic impacts, distributing benefits beyond Alaska through national markets and value-added products.[106] Recreational halibut angling further bolsters regional economies via angler expenditures. In Oregon, the 2024 sport halibut season produced about $3.4 million in economic activity from costs like fuel, bait, and tackle, sustaining jobs in charter operations and marine services.[107] Similar patterns occur in California, where limited quotas support localized spending in northern ports, though precise quantification remains challenging due to variable participation and data gaps in recreational valuations.[108] These activities underscore halibut's role in diversifying income streams for communities dependent on marine resources.Culinary and Nutritional Uses

Nutritional Composition

Halibut flesh provides a lean profile of high-quality protein with moderate fat content, primarily from polyunsaturated fatty acids including omega-3s. According to USDA data for cooked Pacific halibut (dry heat), a 100-gram serving contains approximately 111 kilocalories, 23.96 grams of protein, 1.33 grams of total fat (of which about 0.4 grams are EPA and DHA combined), and negligible carbohydrates. The low fat content classifies halibut as a white fish, with seasonal variations in lipid levels influenced by spawning cycles, typically peaking slightly higher in pre-spawning periods but remaining under 3 grams per 100 grams year-round in wild specimens.[109] Key micronutrients include selenium (approximately 47 micrograms per 100 grams, exceeding 85% of the daily value), vitamin B12 (1.6 micrograms, about 67% daily value), phosphorus (270 milligrams, 22% daily value), and niacin (6.2 milligrams, 39% daily value), supporting metabolic and antioxidant functions. Omega-3 fatty acids, particularly EPA (0.18 grams) and DHA (0.23 grams) per 100 grams, contribute anti-inflammatory benefits, though at lower levels than fattier fish like salmon.[110]| Nutrient (per 100g cooked) | Amount | % Daily Value* |

|---|---|---|

| Calories | 111 kcal | - |

| Protein | 23.96 g | 48% |

| Total Fat | 1.33 g | 2% |

| Omega-3 (EPA + DHA) | ~0.41 g | - |

| Selenium | 47 mcg | 85% |

| Vitamin B12 | 1.6 mcg | 67% |

| Phosphorus | 270 mg | 22% |

Preparation and Consumption Practices

Halibut preparation begins with filleting the fish to yield large, boneless portions or bone-in steaks, leveraging its firm flesh for versatile cuts that maintain structural integrity during cooking.[113] These cuts are typically skinned and portioned to remove any remaining bones, ensuring clean presentation.[113] Common cooking methods prioritize moisture retention to counter the fish's lean nature, including pan-searing at high heat for a crisp exterior while targeting an internal temperature of 130-135°F to achieve flakiness without dryness.[114] [115] Baking at 375°F with coverings like foil or herb butter, grilling over medium-high heat, and poaching in aromatic liquids or oils—such as low-heat butter or broth—further preserve tenderness, with poaching times of 8-10 minutes sufficing for fillets.[116] [117] Overcooking beyond 145°F risks toughness, so precise thermometry is recommended.[114] Traditional practices among indigenous Alaskan communities and Nordic cultures often involve smoking halibut, using dry brines followed by hot-smoking at controlled temperatures for preservation and flavor infusion, or cold-smoking below 85°F for subtler smokiness.[118] [119] In contemporary global applications, halibut commands demand as a premium whitefish, adapted to techniques like Asian-inspired poaching with ginger and citrus for subtle enhancement.[120] Safety considerations address potential parasites, such as nematodes, prevalent in marine fish; thorough cooking to 140°F for at least one minute eliminates viable larvae, rendering consumption empirically low-risk when handled properly from catch to plate.[121] [122] Freezing at -4°F for seven days prior to raw uses, though uncommon for halibut, provides an alternative safeguard.[122] Proper filleting and immediate refrigeration minimize bacterial growth during processing.[113]