Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide

View on Wikipedia

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names

Diphosphopyridine nucleotide (DPN+), Coenzyme I

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.169 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C21H28N7O14P2+ (oxidized) C21H29N7O14P2 (reduced) | |

| Molar mass | 664.4 g/mol (oxidized) 665.4 g/mol (reduced) |

| Appearance | White powder |

| Melting point | 160 °C (320 °F; 433 K) |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards

|

Not hazardous |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

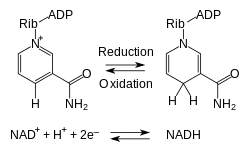

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) is a coenzyme central to metabolism.[1] Found in all living cells, NAD is called a dinucleotide because it consists of two nucleotides joined through their phosphate groups. One nucleotide contains an adenine nucleobase and the other, nicotinamide. NAD exists in two forms: an oxidized and reduced form, abbreviated as NAD+ and NADH (H for hydrogen), respectively.

In cellular metabolism, NAD is involved in redox reactions, carrying electrons from one reaction to another, so it is found in two forms: NAD+ is an oxidizing agent, accepting electrons from other molecules and becoming reduced; with H+, this reaction forms NADH, which can be used as a reducing agent to donate electrons. These electron transfer reactions are the main function of NAD. It is also used in other cellular processes, most notably as a substrate of enzymes in adding or removing chemical groups to or from proteins, in posttranslational modifications. Because of the importance of these functions, the enzymes involved in NAD metabolism are targets for drug discovery.

In organisms, NAD can be synthesized from simple building-blocks (de novo) from either tryptophan or aspartic acid, each a case of an amino acid. Alternatively, more complex components of the coenzymes are taken up from nutritive compounds such as nicotinic acid; similar compounds are produced by reactions that break down the structure of NAD, providing a salvage pathway that recycles them back into their respective active form.

In the name NAD+, the superscripted plus sign indicates the positive formal charge on one of its nitrogen atoms. A biological coenzyme that acts as an electron carrier in enzymatic reactions.

Some NAD is converted into the coenzyme nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP), whose chemistry largely parallels that of NAD, though its predominant role is as a coenzyme in anabolic metabolism. NADP is a reducing agent in anabolic reactions like the Calvin cycle and lipid and nucleic acid syntheses. NADP exists in two forms: NADP+, the oxidized form, and NADPH, the reduced form. NADP is similar to nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD), but NADP has a phosphate group at the C-2′ position of the adenosyl.

Physical and chemical properties

[edit]Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide consists of two nucleosides joined by pyrophosphate. The nucleosides each contain a ribose ring, one with adenine attached to the first carbon atom (the 1' position) (adenosine diphosphate ribose) and the other with nicotinamide at this position.[2][3]

The compound accepts or donates the equivalent of H−.[4] Such reactions (summarized in formula below) involve the removal of two hydrogen atoms from a reactant (R), in the form of a hydride ion (H−), and a proton (H+). The proton is released into solution, while the reductant RH2 is oxidized and NAD+ reduced to NADH by transfer of the hydride to the nicotinamide ring.

- RH2 + NAD+ → NADH + H+ + R;

From the electron pair of the hydride ion, one electron is attracted to the slightly more electronegative atom of the nicotinamide ring of NAD+, becoming part of the nicotinamide moiety. The remaining hydrogen atom is transferred to the carbon atom opposite the N atom. The midpoint potential of the NAD+/NADH redox pair is −0.32 volts, which makes NADH a moderately strong reducing agent.[5] The reaction is easily reversible, when NADH reduces another molecule and is re-oxidized to NAD+. This means the coenzyme can continuously cycle between the NAD+ and NADH forms without being consumed.[3]

In appearance, all forms of this coenzyme are white amorphous powders that are hygroscopic and highly water-soluble.[6] The solids are stable if stored dry and in the dark. Solutions of NAD+ are colorless and stable for about a week at 4 °C and neutral pH, but decompose rapidly in acidic or alkaline solutions. Upon decomposition, they form products that are enzyme inhibitors.[7]

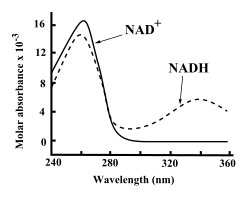

Both NAD+ and NADH strongly absorb ultraviolet light because of the adenine. For example, peak absorption of NAD+ is at a wavelength of 259 nanometers (nm), with an extinction coefficient of 16,900 M−1cm−1. NADH also absorbs at higher wavelengths, with a second peak in UV absorption at 339 nm with an extinction coefficient of 6,220 M−1cm−1.[8] This difference in the ultraviolet absorption spectra between the oxidized and reduced forms of the coenzymes at higher wavelengths makes it simple to measure the conversion of one to another in enzyme assays – by measuring the amount of UV absorption at 340 nm using a spectrophotometer.[8]

NAD+ and NADH also differ in their fluorescence. Freely diffusing NADH in aqueous solution, when excited at the nicotinamide absorbance of ~335 nm (near-UV), fluoresces at 445–460 nm (violet to blue) with a fluorescence lifetime of 0.4 nanoseconds, while NAD+ does not fluoresce.[9][10] The properties of the fluorescence signal changes when NADH binds to proteins, so these changes can be used to measure dissociation constants, which are useful in the study of enzyme kinetics.[10][11] These changes in fluorescence are also used to measure changes in the redox state of living cells, through fluorescence microscopy.[12]

NADH can be converted to NAD+ in a reaction catalysed by copper, which requires hydrogen peroxide. Thus, the supply of NAD+ in cells requires mitochondrial copper(II).[13][14]

Concentration and state in cells

[edit]In rat liver, the total amount of NAD+ and NADH is approximately 1 μmole per gram of wet weight, about 10 times the concentration of NADP+ and NADPH in the same cells.[15] The actual concentration of NAD+ in cell cytosol is harder to measure, with recent estimates in animal cells ranging around 0.3 mM,[16][17] and approximately 1.0 to 2.0 mM in yeast.[18] However, more than 80% of NADH fluorescence in mitochondria is from bound form, so the concentration in solution is much lower.[19]

NAD+ concentrations are highest in the mitochondria, constituting 40% to 70% of the total cellular NAD+.[20] NAD+ in the cytosol is carried into the mitochondrion by a specific membrane transport protein, since the coenzyme cannot diffuse across membranes.[21] The intracellular half-life of NAD+ was claimed to be between 1–2 hours by one review,[22] whereas another review gave varying estimates based on compartment: intracellular 1–4 hours, cytoplasmic 2 hours, and mitochondrial 4–6 hours.[23]

The balance between the oxidized and reduced forms of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide is called the NAD+/NADH ratio. This ratio is an important component of what is called the redox state of a cell, a measurement that reflects both the metabolic activities and the health of cells.[24] The effects of the NAD+/NADH ratio are complex, controlling the activity of several key enzymes, including glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase and pyruvate dehydrogenase. In healthy mammalian tissues, estimates of the ratio of free NAD+ to NADH in the cytoplasm typically lie around 700:1; the ratio is thus favorable for oxidative reactions.[25][26] The ratio of total NAD+/NADH is much lower, with estimates ranging from 3–10 in mammals.[27] In contrast, the NADP+/NADPH ratio is normally about 0.005, so NADPH is the dominant form of this coenzyme.[28] These different ratios are key to the different metabolic roles of NADH and NADPH.

Biosynthesis

[edit]NAD+ is synthesized through two metabolic pathways. It is produced either in a de novo pathway from amino acids or in salvage pathways by recycling preformed components such as nicotinamide back to NAD+. Although most tissues synthesize NAD+ by the salvage pathway in mammals, much more de novo synthesis occurs in the liver from tryptophan, and in the kidney and macrophages from nicotinic acid.[29]

De novo production

[edit]

Most organisms synthesize NAD+ from simple components.[4] The specific set of reactions differs among organisms, but a common feature is the generation of quinolinic acid (QA) from an amino acid – either tryptophan (Trp) in animals and some bacteria, or aspartic acid (Asp) in some bacteria and plants.[30][31] The quinolinic acid is converted to nicotinic acid mononucleotide (NaMN) by transfer of a phosphoribose moiety. An adenylate moiety is then transferred to form nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide (NaAD). Finally, the nicotinic acid moiety in NaAD is amidated to a nicotinamide (Nam) moiety, forming nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide.[4]

In a further step, some NAD+ is converted into NADP+ by NAD+ kinase, which phosphorylates NAD+.[32] In most organisms, this enzyme uses adenosine triphosphate (ATP) as the source of the phosphate group, although several bacteria such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis and a hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus horikoshii, use inorganic polyphosphate as an alternative phosphoryl donor.[33][34]

Salvage pathways

[edit]Despite the presence of the de novo pathway, the salvage reactions are essential in humans; a lack of vitamin B3 in the diet causes the vitamin deficiency disease pellagra.[35] This high requirement for NAD+ results from the constant consumption of the coenzyme in reactions such as posttranslational modifications, since the cycling of NAD+ between oxidized and reduced forms in redox reactions does not change the overall levels of the coenzyme.[4] The major source of NAD+ in mammals is the salvage pathway which recycles the nicotinamide produced by enzymes utilizing NAD+.[36] The first step, and the rate-limiting enzyme in the salvage pathway is nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), which produces nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN).[36] NMN is the immediate precursor to NAD+ in the salvage pathway.[37]

Besides assembling NAD+ de novo from simple amino acid precursors, cells also salvage preformed compounds containing a pyridine base. The three vitamin precursors used in these salvage metabolic pathways are nicotinic acid (NA), nicotinamide (Nam) and nicotinamide riboside (NR).[4] These compounds can be taken up from the diet and are termed vitamin B3 or niacin. However, these compounds are also produced within cells and by digestion of cellular NAD+. Some of the enzymes involved in these salvage pathways appear to be concentrated in the cell nucleus, which may compensate for the high level of reactions that consume NAD+ in this organelle.[38] There are some reports that mammalian cells can take up extracellular NAD+ from their surroundings,[39] and both nicotinamide and nicotinamide riboside can be absorbed from the gut.[40]

The salvage pathways used in microorganisms differ from those of mammals.[41] Some pathogens, such as the yeast Candida glabrata and the bacterium Haemophilus influenzae are NAD+ auxotrophs – they cannot synthesize NAD+ – but possess salvage pathways and thus are dependent on external sources of NAD+ or its precursors.[42][43] Even more surprising is the intracellular pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis, which lacks recognizable candidates for any genes involved in the biosynthesis or salvage of both NAD+ and NADP+, and must acquire these coenzymes from its host.[44]

Functions

[edit]

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide has several essential roles in metabolism. It acts as a coenzyme in redox reactions, as a donor of ADP-ribose moieties in ADP-ribosylation reactions, as a precursor of the second messenger molecule cyclic ADP-ribose, as well as acting as a substrate for bacterial DNA ligases and a group of enzymes called sirtuins that use NAD+ to remove acetyl groups from proteins. In addition to these metabolic functions, NAD+ emerges as an adenine nucleotide that can be released from cells spontaneously and by regulated mechanisms,[46][47] and can therefore have important extracellular roles.[47]

Oxidoreductase binding of NAD

[edit]The main role of NAD+ in metabolism is the transfer of electrons from one molecule to another. Reactions of this type are catalyzed by a large group of enzymes called oxidoreductases. The correct names for these enzymes contain the names of both their substrates: for example NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase catalyzes the oxidation of NADH by coenzyme Q.[48] However, these enzymes are also referred to as dehydrogenases or reductases, with NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase commonly being called NADH dehydrogenase or sometimes coenzyme Q reductase.[49]

There are many different superfamilies of enzymes that bind NAD+ / NADH. One of the most common superfamilies includes a structural motif known as the Rossmann fold.[50][51] The motif is named after Michael Rossmann, who was the first scientist to notice how common this structure is within nucleotide-binding proteins.[52]

An example of a NAD-binding bacterial enzyme involved in amino acid metabolism that does not have the Rossmann fold is found in Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato (PDB: 2CWH; InterPro: IPR003767).[53]

When bound in the active site of an oxidoreductase, the nicotinamide ring of the coenzyme is positioned so that it can accept a hydride from the other substrate. Depending on the enzyme, the hydride donor is positioned either "above" or "below" the plane of the planar C4 carbon, as defined in the figure. Class A oxidoreductases transfer the atom from above; class B enzymes transfer it from below. Since the C4 carbon that accepts the hydrogen is prochiral, this can be exploited in enzyme kinetics to give information about the enzyme's mechanism. This is done by mixing an enzyme with a substrate that has deuterium atoms substituted for the hydrogens, so the enzyme will reduce NAD+ by transferring deuterium rather than hydrogen. In this case, an enzyme can produce one of two stereoisomers of NADH.[54]

Despite the similarity in how proteins bind the two coenzymes, enzymes almost always show a high level of specificity for either NAD+ or NADP+.[55] This specificity reflects the distinct metabolic roles of the respective coenzymes, and is the result of distinct sets of amino acid residues in the two types of coenzyme-binding pocket. For instance, in the active site of NADP-dependent enzymes, an ionic bond is formed between a basic amino acid side-chain and the acidic phosphate group of NADP+. On the converse, in NAD-dependent enzymes the charge in this pocket is reversed, preventing NADP+ from binding. However, there are a few exceptions to this general rule, and enzymes such as aldose reductase, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase can use both coenzymes in some species.[56]

Role in redox metabolism

[edit]

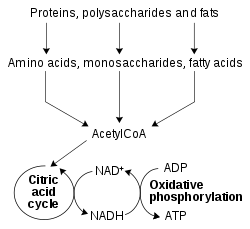

The redox reactions catalyzed by oxidoreductases are vital in all parts of metabolism, but one particularly important area where these reactions occur is in the release of energy from nutrients. Here, reduced compounds such as glucose and fatty acids are oxidized, thereby releasing energy. This energy is transferred to NAD+ by reduction to NADH, as part of beta oxidation, glycolysis, and the citric acid cycle. In eukaryotes the electrons carried by the NADH that is produced in the cytoplasm are transferred into the mitochondrion (to reduce mitochondrial NAD+) by mitochondrial shuttles, such as the malate-aspartate shuttle.[57] The mitochondrial NADH is then oxidized in turn by the electron transport chain, which pumps protons across a membrane and generates ATP through oxidative phosphorylation.[58] These shuttle systems also have the same transport function in chloroplasts.[59]

Since both the oxidized and reduced forms of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide are used in these linked sets of reactions, the cell maintains significant concentrations of both NAD+ and NADH, with the high NAD+/NADH ratio allowing this coenzyme to act as both an oxidizing and a reducing agent.[60] In contrast, the main function of NADPH is as a reducing agent in anabolism, with this coenzyme being involved in pathways such as fatty acid synthesis and photosynthesis. Since NADPH is needed to drive redox reactions as a strong reducing agent, the NADP+/NADPH ratio is kept very low.[60]

Although it is important in catabolism, NADH is also used in anabolic reactions, such as gluconeogenesis.[61] This need for NADH in anabolism poses a problem for prokaryotes growing on nutrients that release only a small amount of energy. For example, nitrifying bacteria such as Nitrobacter oxidize nitrite to nitrate, which releases sufficient energy to pump protons and generate ATP, but not enough to produce NADH directly.[62] As NADH is still needed for anabolic reactions, these bacteria use a nitrite oxidoreductase to produce enough proton-motive force to run part of the electron transport chain in reverse, generating NADH.[63]

Non-redox roles

[edit]The coenzyme NAD+ is also consumed in ADP-ribose transfer reactions. For example, enzymes called ADP-ribosyltransferases add the ADP-ribose moiety of this molecule to proteins, in a posttranslational modification called ADP-ribosylation.[64] ADP-ribosylation involves either the addition of a single ADP-ribose moiety, in mono-ADP-ribosylation, or the transferral of ADP-ribose to proteins in long branched chains, which is called poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation.[65] Mono-ADP-ribosylation was first identified as the mechanism of a group of bacterial toxins, notably cholera toxin, but it is also involved in normal cell signaling.[66][67] Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation is carried out by the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases.[65][68] The poly(ADP-ribose) structure is involved in the regulation of several cellular events and is most important in the cell nucleus, in processes such as DNA repair and telomere maintenance.[68] In addition to these functions within the cell, a group of extracellular ADP-ribosyltransferases has recently been discovered, but their functions remain obscure.[69] NAD+ may also be added onto cellular RNA as a 5'-terminal modification.[70]

Another function of this coenzyme in cell signaling is as a precursor of cyclic ADP-ribose, which is produced from NAD+ by ADP-ribosyl cyclases, as part of a second messenger system.[71] This molecule acts in calcium signaling by releasing calcium from intracellular stores.[72] It does this by binding to and opening a class of calcium channels called ryanodine receptors, which are located in the membranes of organelles, such as the endoplasmic reticulum, and inducing the activation of the transcription factor NAFC3[73]

NAD+ is also consumed by different NAD+-consuming enzymes, such as CD38, CD157, PARPs and the NAD-dependent deacetylases (sirtuins, such as Sir2.[74]).[75] These enzymes act by transferring an acetyl group from their substrate protein to the ADP-ribose moiety of NAD+; this cleaves the coenzyme and releases nicotinamide and O-acetyl-ADP-ribose. The sirtuins mainly seem to be involved in regulating transcription through deacetylating histones and altering nucleosome structure.[76] However, non-histone proteins can be deacetylated by sirtuins as well. These activities of sirtuins are particularly interesting because of their importance in the regulation of aging.[77][78]

Other NAD-dependent enzymes include bacterial DNA ligases, which join two DNA ends by using NAD+ as a substrate to donate an adenosine monophosphate (AMP) moiety to the 5' phosphate of one DNA end. This intermediate is then attacked by the 3' hydroxyl group of the other DNA end, forming a new phosphodiester bond.[79] This contrasts with eukaryotic DNA ligases, which use ATP to form the DNA-AMP intermediate.[80]

Li et al. have found that NAD+ directly regulates protein-protein interactions.[81] They also show that one of the causes of age-related decline in DNA repair may be increased binding of the protein DBC1 (Deleted in Breast Cancer 1) to PARP1 (poly[ADP–ribose] polymerase 1) as NAD+ levels decline during aging.[81] The decline in cellular concentrations of NAD+ during aging likely contributes to the aging process and to the pathogenesis of the chronic diseases of aging.[82] Thus, the modulation of NAD+ may protect against cancer, radiation, and aging.[81]

Extracellular actions of NAD+

[edit]In recent years, NAD+ has also been recognized as an extracellular signaling molecule involved in cell-to-cell communication.[47][83][84] NAD+ is released from neurons in blood vessels,[46] urinary bladder,[46][85] large intestine,[86][87] from neurosecretory cells,[88] and from brain synaptosomes,[89] and is proposed to be a novel neurotransmitter that transmits information from nerves to effector cells in smooth muscle organs.[86][87] In plants, the extracellular nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide induces resistance to pathogen infection and the first extracellular NAD receptor has been identified.[90] Further studies are needed to determine the underlying mechanisms of its extracellular actions and their importance for human health and life processes in other organisms.

Clinical significance

[edit]The enzymes that make and use NAD+ and NADH are important in both pharmacology and the research into future treatments for disease.[91] Drug design and drug development exploits NAD+ in three ways: as a direct target of drugs, by designing enzyme inhibitors or activators based on its structure that change the activity of NAD-dependent enzymes, and by trying to inhibit NAD+ biosynthesis.[92]

Because cancer cells utilize increased glycolysis, and because NAD enhances glycolysis, nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAD salvage pathway) is often amplified in cancer cells.[93][94]

It has been studied for its potential use in the therapy of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease as well as multiple sclerosis.[4][78][95][75] A placebo-controlled clinical trial of NADH (which excluded NADH precursors) in people with Parkinson's failed to show any effect.[96]

NAD+ is also a direct target of the drug isoniazid, which is used in the treatment of tuberculosis, an infection caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Isoniazid is a prodrug and once it has entered the bacteria, it is activated by a peroxidase enzyme, which oxidizes the compound into a free radical form.[97] This radical then reacts with NADH, to produce adducts that are very potent inhibitors of the enzymes enoyl-acyl carrier protein reductase,[98] and dihydrofolate reductase.[99]

Since many oxidoreductases use NAD+ and NADH as substrates, and bind them using a highly conserved structural motif, the idea that inhibitors based on NAD+ could be specific to one enzyme is surprising.[100] However, this can be possible: for example, inhibitors based on the compounds mycophenolic acid and tiazofurin inhibit IMP dehydrogenase at the NAD+ binding site. Because of the importance of this enzyme in purine metabolism, these compounds may be useful as anti-cancer, anti-viral, or immunosuppressive drugs.[100][101] Other drugs are not enzyme inhibitors, but instead activate enzymes involved in NAD+ metabolism. Sirtuins are a particularly interesting target for such drugs, since activation of these NAD-dependent deacetylases extends lifespan in some animal models.[102] Compounds such as resveratrol increase the activity of these enzymes, which may be important in their ability to delay aging in both vertebrate,[103] and invertebrate model organisms.[104][105] In one experiment, mice given NAD for one week had improved nuclear-mitochrondrial communication.[106]

Because of the differences in the metabolic pathways of NAD+ biosynthesis between organisms, such as between bacteria and humans, this area of metabolism is a promising area for the development of new antibiotics.[107][108] For example, the enzyme nicotinamidase, which converts nicotinamide to nicotinic acid, is a target for drug design because this enzyme is absent in humans but present in yeast and bacteria.[41]

In bacteriology, NAD, sometimes referred to factor V, is used as a supplement to culture media for some fastidious bacteria.[109]

High-cost unlicensed infusions of NAD+ have been claimed in the UK to be "clinically proven" and "effective" treatment for alcoholism and drug abuse. NAD+ is not approved or licensed for medical use in the UK; there are likely breaches of advertising and medicines rules, and no proof that treatments work. Medical experts say "It's complete nonsense" ... "It's untested and unproven. We don't know anything about its efficacy or long-term safety". A November 2024 study, cited 700 times, claiming that NAD+ levels in lab rats decreased with age was withdrawn after images were found to have been manipulated, and underlying data was not provided to the publishers on request.[110]

History

[edit]

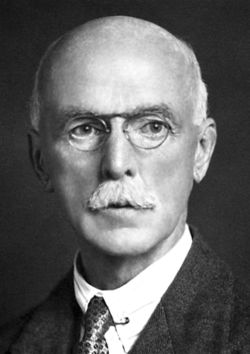

The coenzyme NAD+ was first discovered by the British biochemists Arthur Harden and William John Young in 1906.[111] They noticed that adding boiled and filtered yeast extract greatly accelerated alcoholic fermentation in unboiled yeast extracts. They called the unidentified factor responsible for this effect a coferment. Through a long and difficult purification from yeast extracts, this heat-stable factor was identified as a nucleotide sugar phosphate by Hans von Euler-Chelpin.[112] In 1936, the German scientist Otto Heinrich Warburg showed the function of the nucleotide coenzyme in hydride transfer and identified the nicotinamide portion as the site of redox reactions.[113]

Vitamin precursors of NAD+ were first identified in 1938, when Conrad Elvehjem showed that liver has an "anti-black tongue" activity in the form of nicotinamide.[114] Then, in 1939, he provided the first strong evidence that nicotinic acid is used to synthesize NAD+.[115] In the early 1940s, Arthur Kornberg was the first to detect an enzyme in the biosynthetic pathway.[116] In 1949, the American biochemists Morris Friedkin and Albert L. Lehninger proved that NADH linked metabolic pathways such as the citric acid cycle with the synthesis of ATP in oxidative phosphorylation.[117] In 1958, Jack Preiss and Philip Handler discovered the intermediates and enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of NAD+;[118][119] salvage synthesis from nicotinic acid is termed the Preiss-Handler pathway. In 2004, Charles Brenner and co-workers uncovered the nicotinamide riboside kinase pathway to NAD+.[120]

The non-redox roles of NAD(P) were discovered later.[3] The first to be identified was the use of NAD+ as the ADP-ribose donor in ADP-ribosylation reactions, observed in the early 1960s.[121] Studies in the 1980s and 1990s revealed the activities of NAD+ and NADP+ metabolites in cell signaling – such as the action of cyclic ADP-ribose, which was discovered in 1987.[122]

The metabolism of NAD+ remained an area of intense research into the 21st century, with interest heightened after the discovery of the NAD+-dependent protein deacetylases called sirtuins in 2000, by Shin-ichiro Imai and coworkers in the laboratory of Leonard P. Guarente.[123] In 2009 Imai proposed the "NAD World" hypothesis that key regulators of aging and longevity in mammals are sirtuin 1 and the primary NAD+ synthesizing enzyme nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT).[124] In 2016 Imai expanded his hypothesis to "NAD World 2.0", which postulates that extracellular NAMPT from adipose tissue maintains NAD+ in the hypothalamus (the control center) in conjunction with myokines from skeletal muscle cells.[125] In 2018, Napa Therapeutics was formed to develop drugs against a novel aging-related target based on the research in NAD metabolism conducted in the lab of Eric Verdin.[126]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Nelson, David L.; Cox, Michael M. (2005). Principles of Biochemistry (4th ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-4339-6.

- ^ The nicotinamide group can be attached in two orientations to the anomeric ribose carbon atom. Because of these two possible structures, the NAD could exists as either of two diastereomers. It is the β-nicotinamide diastereomer of NAD+ that is found in nature.

- ^ a b c Pollak N, Dölle C, Ziegler M (2007). "The power to reduce: pyridine nucleotides – small molecules with a multitude of functions". Biochem. J. 402 (2): 205–218. doi:10.1042/BJ20061638. PMC 1798440. PMID 17295611.

- ^ a b c d e f Belenky, Peter; Bogan, Katrina L.; Brenner, Charles (January 2007). "NAD+ metabolism in health and disease". Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 32 (1): 12–19. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2006.11.006. PMID 17161604.

- ^ Unden G, Bongaerts J (1997). "Alternative respiratory pathways of Escherichia coli: energetics and transcriptional regulation in response to electron acceptors". Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1320 (3): 217–234. doi:10.1016/S0005-2728(97)00034-0. PMID 9230919.

- ^ Windholz, Martha (1983). The Merck Index: an encyclopedia of chemicals, drugs, and biologicals (10th ed.). Rahway NJ: Merck. p. 909. ISBN 978-0-911910-27-8.

- ^ Biellmann JF, Lapinte C, Haid E, Weimann G (1979). "Structure of lactate dehydrogenase inhibitor generated from coenzyme". Biochemistry. 18 (7): 1212–1217. doi:10.1021/bi00574a015. PMID 218616.

- ^ a b Dawson, R. Ben (1985). Data for biochemical research (3rd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-19-855358-8.

- ^ Blacker, Thomas S.; Mann, Zoe F.; Gale, Jonathan E.; Ziegler, Mathias; Bain, Angus J.; Szabadkai, Gyorgy; Duchen, Michael R. (29 May 2014). "Separating NADH and NADPH fluorescence in live cells and tissues using FLIM". Nature Communications. 5 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 3936. Bibcode:2014NatCo...5.3936B. doi:10.1038/ncomms4936. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4046109. PMID 24874098.

- ^ a b Lakowicz JR, Szmacinski H, Nowaczyk K, Johnson ML (1992). "Fluorescence lifetime imaging of free and protein-bound NADH". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89 (4): 1271–1275. Bibcode:1992PNAS...89.1271L. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.4.1271. PMC 48431. PMID 1741380.

- ^ Jameson DM, Thomas V, Zhou DM (1989). "Time-resolved fluorescence studies on NADH bound to mitochondrial malate dehydrogenase". Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 994 (2): 187–190. doi:10.1016/0167-4838(89)90159-3. PMID 2910350.

- ^ Kasimova MR, Grigiene J, Krab K, Hagedorn PH, Flyvbjerg H, Andersen PE, Møller IM (2006). "The Free NADH Concentration Is Kept Constant in Plant Mitochondria under Different Metabolic Conditions". Plant Cell. 18 (3): 688–698. Bibcode:2006PlanC..18..688K. doi:10.1105/tpc.105.039354. PMC 1383643. PMID 16461578.

- ^ Chan, PC; Kesner, L (September 1980). "Copper (II) complex-catalyzed oxidation of NADH by hydrogen peroxide". Biol Trace Elem Res. 2 (3): 159–174. Bibcode:1980BTER....2..159C. doi:10.1007/BF02785352. PMID 24271266. S2CID 24264851.

- ^ Solier, Stéphanie; Müller, Sebastian; Tatiana, Cañeque; Antoine, Versini; Arnaud, Mansart; Fabien, Sindikubwabo; Leeroy, Baron; Laila, Emam; Pierre, Gestraud; G. Dan, Pantoș; Vincent, Gandon; Christine, Gaillet; Ting-Di, Wu; Florent, Dingli; Damarys, Loew; Sylvain, Baulande; Sylvère, Durand; Valentin, Sencio; Cyril, Robil; François, Trottein; David, Péricat; Emmanuelle, Näser; Céline, Cougoule; Etienne, Meunier; Anne-Laure, Bègue; Hélène, Salmon; Nicolas, Manel; Alain, Puisieux; Sarah, Watson; Mark A., Dawson; Nicolas, Servant; Guido, Kroemer; Djillali, Annane; Raphaël, Rodriguez (2023). "A druggable copper-signalling pathway that drives inflammation". Nature. 617 (7960): 386–394. Bibcode:2023Natur.617..386S. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06017-4. PMC 10131557. PMID 37100912. S2CID 258353949.

- ^ Reiss PD, Zuurendonk PF, Veech RL (1984). "Measurement of tissue purine, pyrimidine, and other nucleotides by radial compression high-performance liquid chromatography". Anal. Biochem. 140 (1): 162–71. doi:10.1016/0003-2697(84)90148-9. PMID 6486402.

- ^ Yamada K, Hara N, Shibata T, Osago H, Tsuchiya M (2006). "The simultaneous measurement of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide and related compounds by liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry". Anal. Biochem. 352 (2): 282–5. doi:10.1016/j.ab.2006.02.017. PMID 16574057.

- ^ Yang H, Yang T, Baur JA, Perez E, Matsui T, Carmona JJ, Lamming DW, Souza-Pinto NC, Bohr VA, Rosenzweig A, de Cabo R, Sauve AA, Sinclair DA (2007). "Nutrient-Sensitive Mitochondrial NAD+ Levels Dictate Cell Survival". Cell. 130 (6): 1095–107. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.035. PMC 3366687. PMID 17889652.

- ^ Belenky P, Racette FG, Bogan KL, McClure JM, Smith JS, Brenner C (2007). "Nicotinamide riboside promotes Sir2 silencing and extends lifespan via Nrk and Urh1/Pnp1/Meu1 pathways to NAD+". Cell. 129 (3): 473–84. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.024. PMID 17482543. S2CID 4661723.

- ^ Blinova K, Carroll S, Bose S, Smirnov AV, Harvey JJ, Knutson JR, Balaban RS (2005). "Distribution of mitochondrial NADH fluorescence lifetimes: steady-state kinetics of matrix NADH interactions". Biochemistry. 44 (7): 2585–94. doi:10.1021/bi0485124. PMID 15709771.

- ^ Hopp A, Grüter P, Hottiger MO (2019). "Regulation of Glucose Metabolism by NAD + and ADP-Ribosylation". Cells. 8 (8): 890. doi:10.3390/cells8080890. PMC 6721828. PMID 31412683.

- ^ Todisco S, Agrimi G, Castegna A, Palmieri F (2006). "Identification of the mitochondrial NAD+ transporter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae". J. Biol. Chem. 281 (3): 1524–31. doi:10.1074/jbc.M510425200. PMID 16291748.

- ^ Srivastava S (2016). "Emerging therapeutic roles for NAD(+) metabolism in mitochondrial and age-related disorders". Clinical and Translational Medicine. 5 (1) e25: 25. doi:10.1186/s40169-016-0104-7. PMC 4963347. PMID 27465020.

- ^ Zhang, Ning; Sauve, Anthony A. (2018). "Regulatory Effects of NAD + Metabolic Pathways on Sirtuin Activity". Sirtuins in Health and Disease. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science. Vol. 154. pp. 71–104. doi:10.1016/bs.pmbts.2017.11.012. ISBN 978-0-12-812261-7. PMID 29413178.

- ^ Schafer FQ, Buettner GR (2001). "Redox environment of the cell as viewed through the redox state of the glutathione disulfide/glutathione couple". Free Radic Biol Med. 30 (11): 1191–212. doi:10.1016/S0891-5849(01)00480-4. PMID 11368918.

- ^ Williamson DH, Lund P, Krebs HA (1967). "The redox state of free nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide in the cytoplasm and mitochondria of rat liver". Biochem. J. 103 (2): 514–27. doi:10.1042/bj1030514. PMC 1270436. PMID 4291787.

- ^ Zhang Q, Piston DW, Goodman RH (2002). "Regulation of corepressor function by nuclear NADH". Science. 295 (5561): 1895–7. doi:10.1126/science.1069300. PMID 11847309. S2CID 31268989.

- ^ Lin SJ, Guarente L (April 2003). "Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, a metabolic regulator of transcription, longevity and disease". Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15 (2): 241–6. doi:10.1016/S0955-0674(03)00006-1. PMID 12648681.

- ^ Veech RL, Eggleston LV, Krebs HA (1969). "The redox state of free nicotinamide–adenine dinucleotide phosphate in the cytoplasm of rat liver". Biochem. J. 115 (4): 609–19. doi:10.1042/bj1150609a. PMC 1185185. PMID 4391039.

- ^ McReynolds MR, Chellappa K, Baur JA (2020). "Age-related NAD + decline". Experimental Gerontology. 134 110888. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2020.110888. PMC 7442590. PMID 32097708.

- ^ Katoh A, Uenohara K, Akita M, Hashimoto T (2006). "Early Steps in the Biosynthesis of NAD in Arabidopsis Start with Aspartate and Occur in the Plastid". Plant Physiol. 141 (3): 851–857. doi:10.1104/pp.106.081091. PMC 1489895. PMID 16698895.

- ^ Foster JW, Moat AG (1 March 1980). "Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide biosynthesis and pyridine nucleotide cycle metabolism in microbial systems". Microbiol. Rev. 44 (1): 83–105. doi:10.1128/MMBR.44.1.83-105.1980. PMC 373235. PMID 6997723.

- ^ Magni G, Orsomando G, Raffaelli N (2006). "Structural and functional properties of NAD kinase, a key enzyme in NADP biosynthesis". Mini Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry. 6 (7): 739–746. doi:10.2174/138955706777698688. PMID 16842123.

- ^ Sakuraba H, Kawakami R, Ohshima T (2005). "First Archaeal Inorganic Polyphosphate/ATP-Dependent NAD Kinase, from Hyperthermophilic Archaeon Pyrococcus horikoshii: Cloning, Expression, and Characterization". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71 (8): 4352–4358. Bibcode:2005ApEnM..71.4352S. doi:10.1128/AEM.71.8.4352-4358.2005. PMC 1183369. PMID 16085824.

- ^ Raffaelli N, Finaurini L, Mazzola F, Pucci L, Sorci L, Amici A, Magni G (2004). "Characterization of Mycobacterium tuberculosis NAD kinase: functional analysis of the full-length enzyme by site-directed mutagenesis". Biochemistry. 43 (23): 7610–7617. doi:10.1021/bi049650w. PMID 15182203.

- ^ Henderson LM (1983). "Niacin". Annu. Rev. Nutr. 3: 289–307. doi:10.1146/annurev.nu.03.070183.001445. PMID 6357238.

- ^ a b Rajman L, Chwalek K, Sinclair DA (2018). "Therapeutic Potential of NAD-Boosting Molecules: The In Vivo Evidence". Cell Metabolism. 27 (3): 529–547. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2018.02.011. PMC 6342515. PMID 29514064.

- ^ "What is NMN?". www.nmn.com. Retrieved 8 January 2021.

- ^ Anderson RM, Bitterman KJ, Wood JG, Medvedik O, Cohen H, Lin SS, Manchester JK, Gordon JI, Sinclair DA (2002). "Manipulation of a nuclear NAD+ salvage pathway delays aging without altering steady-state NAD+ levels". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (21): 18881–18890. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111773200. PMC 3745358. PMID 11884393.

- ^ Billington RA, Travelli C, Ercolano E, Galli U, Roman CB, Grolla AA, Canonico PL, Condorelli F, Genazzani AA (2008). "Characterization of NAD Uptake in Mammalian Cells". J. Biol. Chem. 283 (10): 6367–6374. doi:10.1074/jbc.M706204200. PMID 18180302.

- ^ Trammell SA, Schmidt MS, Weidemann BJ, Redpath P, Jaksch F, Dellinger RW, Li Z, Abel ED, Migaud ME, Brenner C (2016). "Nicotinamide riboside is uniquely and orally bioavailable in mice and humans". Nature Communications. 7 12948. Bibcode:2016NatCo...712948T. doi:10.1038/ncomms12948. PMC 5062546. PMID 27721479.

- ^ a b Rongvaux A, Andris F, Van Gool F, Leo O (2003). "Reconstructing eukaryotic NAD metabolism". BioEssays. 25 (7): 683–690. doi:10.1002/bies.10297. PMID 12815723.

- ^ Ma B, Pan SJ, Zupancic ML, Cormack BP (2007). "Assimilation of NAD+ precursors in Candida glabrata". Mol. Microbiol. 66 (1): 14–25. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05886.x. PMID 17725566. S2CID 22282128.

- ^ Reidl J, Schlör S, Kraiss A, Schmidt-Brauns J, Kemmer G, Soleva E (2000). "NADP and NAD utilization in Haemophilus influenzae". Mol. Microbiol. 35 (6): 1573–1581. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01829.x. PMID 10760156. S2CID 29776509.

- ^ Gerdes SY, Scholle MD, D'Souza M, Bernal A, Baev MV, Farrell M, Kurnasov OV, Daugherty MD, Mseeh F, Polanuyer BM, Campbell JW, Anantha S, Shatalin KY, Chowdhury SA, Fonstein MY, Osterman AL (2002). "From Genetic Footprinting to Antimicrobial Drug Targets: Examples in Cofactor Biosynthetic Pathways". J. Bacteriol. 184 (16): 4555–4572. doi:10.1128/JB.184.16.4555-4572.2002. PMC 135229. PMID 12142426.

- ^ Senkovich O, Speed H, Grigorian A, et al. (2005). "Crystallization of three key glycolytic enzymes of the opportunistic pathogen Cryptosporidium parvum". Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1750 (2): 166–72. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.04.009. PMID 15953771.

- ^ a b c Smyth LM, Bobalova J, Mendoza MG, Lew C, Mutafova-Yambolieva VN (2004). "Release of beta-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide upon stimulation of postganglionic nerve terminals in blood vessels and urinary bladder". J Biol Chem. 279 (47): 48893–903. doi:10.1074/jbc.M407266200. PMID 15364945.

- ^ a b c Billington RA, Bruzzone S, De Flora A, Genazzani AA, Koch-Nolte F, Ziegler M, Zocchi E (2006). "Emerging functions of extracellular pyridine nucleotides". Mol. Med. 12 (11–12): 324–7. doi:10.2119/2006-00075.Billington. PMC 1829198. PMID 17380199.

- ^ "Enzyme Nomenclature, Recommendations for enzyme names from the Nomenclature Committee of the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology". Archived from the original on 5 December 2007. Retrieved 6 December 2007.

- ^ "NiceZyme View of ENZYME: EC 1.6.5.3". Expasy. Retrieved 16 December 2007.

- ^ Hanukoglu I (2015). "Proteopedia: Rossmann fold: A beta-alpha-beta fold at dinucleotide binding sites". Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 43 (3): 206–209. doi:10.1002/bmb.20849. PMID 25704928. S2CID 11857160.

- ^ Lesk AM (1995). "NAD-binding domains of dehydrogenases". Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 5 (6): 775–83. doi:10.1016/0959-440X(95)80010-7. PMID 8749365.

- ^ Rao ST, Rossmann MG (1973). "Comparison of super-secondary structures in proteins". J Mol Biol. 76 (2): 241–56. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(73)90388-4. PMID 4737475.

- ^ Goto M, Muramatsu H, Mihara H, Kurihara T, Esaki N, Omi R, Miyahara I, Hirotsu K (2005). "Crystal structures of Delta1-piperideine-2-carboxylate/Delta1-pyrroline-2-carboxylate reductase belonging to a new family of NAD(P)H-dependent oxidoreductases: conformational change, substrate recognition, and stereochemistry of the reaction". J. Biol. Chem. 280 (49): 40875–84. doi:10.1074/jbc.M507399200. PMID 16192274.

- ^ a b Bellamacina CR (1 September 1996). "The nicotinamide dinucleotide binding motif: a comparison of nucleotide binding proteins". FASEB J. 10 (11): 1257–69. doi:10.1096/fasebj.10.11.8836039. PMID 8836039. S2CID 24189316.

- ^ Carugo O, Argos P (1997). "NADP-dependent enzymes. I: Conserved stereochemistry of cofactor binding". Proteins. 28 (1): 10–28. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0134(199705)28:1<10::AID-PROT2>3.0.CO;2-N. PMID 9144787. S2CID 23969986.

- ^ Vickers TJ, Orsomando G, de la Garza RD, Scott DA, Kang SO, Hanson AD, Beverley SM (2006). "Biochemical and genetic analysis of methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase in Leishmania metabolism and virulence". J. Biol. Chem. 281 (50): 38150–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M608387200. PMID 17032644.

- ^ Bakker BM, Overkamp KM, Kötter P, Luttik MA, Pronk JT (2001). "Stoichiometry and compartmentation of NADH metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae". FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 25 (1): 15–37. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2001.tb00570.x. PMID 11152939.

- ^ Rich, P.R. (1 December 2003). "The molecular machinery of Keilin's respiratory chain". Biochemical Society Transactions. 31 (6): 1095–1105. doi:10.1042/bst0311095. PMID 14641005. S2CID 32361233.

- ^ Heineke D, Riens B, Grosse H, Hoferichter P, Peter U, Flügge UI, Heldt HW (1991). "Redox Transfer across the Inner Chloroplast Envelope Membrane". Plant Physiol. 95 (4): 1131–1137. doi:10.1104/pp.95.4.1131. PMC 1077662. PMID 16668101.

- ^ a b Nicholls DG; Ferguson SJ (2002). Bioenergetics 3 (1st ed.). Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-518121-1.

- ^ Sistare, F D; Haynes, R C (October 1985). "The interaction between the cytosolic pyridine nucleotide redox potential and gluconeogenesis from lactate/pyruvate in isolated rat hepatocytes. Implications for investigations of hormone action". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 260 (23): 12748–12753. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(17)38940-8. PMID 4044607.

- ^ Freitag A, Bock E (1990). "Energy conservation in Nitrobacter". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 66 (1–3): 157–62. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb03989.x.

- ^ Starkenburg SR, Chain PS, Sayavedra-Soto LA, Hauser L, Land ML, Larimer FW, Malfatti SA, Klotz MG, Bottomley PJ, Arp DJ, Hickey WJ (2006). "Genome Sequence of the Chemolithoautotrophic Nitrite-Oxidizing Bacterium Nitrobacter winogradskyi Nb-255". Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72 (3): 2050–63. Bibcode:2006ApEnM..72.2050S. doi:10.1128/AEM.72.3.2050-2063.2006. PMC 1393235. PMID 16517654.

- ^ Ziegler M (2000). "New functions of a long-known molecule. Emerging roles of NAD in cellular signaling". Eur. J. Biochem. 267 (6): 1550–64. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01187.x. PMID 10712584.

- ^ a b Diefenbach J, Bürkle A (2005). "Introduction to poly(ADP-ribose) metabolism". Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62 (7–8): 721–30. doi:10.1007/s00018-004-4503-3. PMC 11924567. PMID 15868397.

- ^ Berger F, Ramírez-Hernández MH, Ziegler M (2004). "The new life of a centenarian: signaling functions of NAD(P)". Trends Biochem. Sci. 29 (3): 111–8. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2004.01.007. PMID 15003268. S2CID 8820773.

- ^ Corda D, Di Girolamo M (2003). "New Embo Member's Review: Functional aspects of protein mono-ADP-ribosylation". EMBO J. 22 (9): 1953–8. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdg209. PMC 156081. PMID 12727863.

- ^ a b Bürkle A (2005). "Poly(ADP-ribose). The most elaborate metabolite of NAD+". FEBS J. 272 (18): 4576–89. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04864.x. PMID 16156780. S2CID 22975714.

- ^ Seman M, Adriouch S, Haag F, Koch-Nolte F (2004). "Ecto-ADP-ribosyltransferases (ARTs): emerging actors in cell communication and signaling". Curr. Med. Chem. 11 (7): 857–72. doi:10.2174/0929867043455611. PMID 15078170.

- ^ Chen YG, Kowtoniuk WE, Agarwal I, Shen Y, Liu DR (December 2009). "LC/MS analysis of cellular RNA reveals NAD-linked RNA". Nat Chem Biol. 5 (12): 879–881. doi:10.1038/nchembio.235. PMC 2842606. PMID 19820715.

- ^ Guse AH (2004). "Biochemistry, biology, and pharmacology of cyclic adenosine diphosphoribose (cADPR)". Curr. Med. Chem. 11 (7): 847–55. doi:10.2174/0929867043455602. PMID 15078169.

- ^ Guse AH (2004). "Regulation of calcium signaling by the second messenger cyclic adenosine diphosphoribose (cADPR)". Curr. Mol. Med. 4 (3): 239–48. doi:10.2174/1566524043360771. PMID 15101682.

- ^ Guse AH (2005). "Second messenger function and the structure-activity relationship of cyclic adenosine diphosphoribose (cADPR)". FEBS J. 272 (18): 4590–7. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04863.x. PMID 16156781. S2CID 21509962.

- ^ North BJ, Verdin E (2004). "Sirtuins: Sir2-related NAD-dependent protein deacetylases". Genome Biol. 5 (5): 224. doi:10.1186/gb-2004-5-5-224. PMC 416462. PMID 15128440.

- ^ a b Verdin, Eric (4 December 2015). "NAD⁺ in aging, metabolism, and neurodegeneration". Science. 350 (6265): 1208–1213. Bibcode:2015Sci...350.1208V. doi:10.1126/science.aac4854. ISSN 1095-9203. PMID 26785480. S2CID 27313960.

- ^ Blander, Gil; Guarente, Leonard (June 2004). "The Sir2 Family of Protein Deacetylases". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 73 (1): 417–435. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073651. PMID 15189148. S2CID 27494475.

- ^ Trapp J, Jung M (2006). "The role of NAD+ dependent histone deacetylases (sirtuins) in ageing". Curr Drug Targets. 7 (11): 1553–60. doi:10.2174/1389450110607011553. PMID 17100594.

- ^ a b Meyer, Tom; Shimon, Dor; Youssef, Sawsan; Yankovitz, Gal; Tessler, Adi; Chernobylsky, Tom; Gaoni-Yogev, Anat; Perelroizen, Rita; Budick-Harmelin, Noga; Steinman, Lawrence; Mayo, Lior (30 August 2022). "NAD+ metabolism drives astrocyte proinflammatory reprogramming in central nervous system autoimmunity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 119 (35) e2211310119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11911310M. doi:10.1073/pnas.2211310119. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 9436380. PMID 35994674.

- ^ Wilkinson A, Day J, Bowater R (2001). "Bacterial DNA ligases". Mol. Microbiol. 40 (6): 1241–8. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02479.x. PMID 11442824. S2CID 19909818.

- ^ Schär P, Herrmann G, Daly G, Lindahl T (1997). "A newly identified DNA ligase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae involved in RAD52-independent repair of DNA double-strand breaks". Genes & Development. 11 (15): 1912–24. doi:10.1101/gad.11.15.1912. PMC 316416. PMID 9271115.

- ^ a b c Li, Jun; Bonkowski, Michael S.; Moniot, Sébastien; Zhang, Dapeng; Hubbard, Basil P.; Ling, Alvin J. Y.; Rajman, Luis A.; Qin, Bo; Lou, Zhenkun; Gorbunova, Vera; Aravind, L.; Steegborn, Clemens; Sinclair, David A. (23 March 2017). "A conserved NAD binding pocket that regulates protein-protein interactions during aging". Science. 355 (6331): 1312–1317. Bibcode:2017Sci...355.1312L. doi:10.1126/science.aad8242. PMC 5456119. PMID 28336669.

- ^ Verdin E. NAD⁺ in aging, metabolism, and neurodegeneration. Science. 2015 Dec 4;350(6265):1208-13. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4854. PMID 26785480

- ^ Ziegler M, Niere M (2004). "NAD+ surfaces again". Biochem. J. 382 (Pt 3) E5: e5–6. doi:10.1042/BJ20041217. PMC 1133982. PMID 15352307.

- ^ Koch-Nolte F, Fischer S, Haag F, Ziegler M (2011). "Compartmentation of NAD+-dependent signalling". FEBS Lett. 585 (11): 1651–6. Bibcode:2011FEBSL.585.1651K. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2011.03.045. PMID 21443875. S2CID 4333147.

- ^ Breen, Leanne T.; Smyth, Lisa M.; Yamboliev, Ilia A.; Mutafova-Yambolieva, Violeta N. (February 2006). "β-NAD is a novel nucleotide released on stimulation of nerve terminals in human urinary bladder detrusor muscle". American Journal of Physiology. Renal Physiology. 290 (2): F486 – F495. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00314.2005. PMID 16189287. S2CID 11400206.

- ^ a b Mutafova-Yambolieva VN, Hwang SJ, Hao X, Chen H, Zhu MX, Wood JD, Ward SM, Sanders KM (2007). "Beta-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide is an inhibitory neurotransmitter in visceral smooth muscle". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (41): 16359–64. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10416359M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0705510104. PMC 2042211. PMID 17913880.

- ^ a b Hwang SJ, Durnin L, Dwyer L, Rhee PL, Ward SM, Koh SD, Sanders KM, Mutafova-Yambolieva VN (2011). "β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide is an enteric inhibitory neurotransmitter in human and nonhuman primate colons". Gastroenterology. 140 (2): 608–617.e6. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2010.09.039. PMC 3031738. PMID 20875415.

- ^ Yamboliev IA, Smyth LM, Durnin L, Dai Y, Mutafova-Yambolieva VN (2009). "Storage and secretion of beta-NAD, ATP and dopamine in NGF-differentiated rat pheochromocytoma PC12 cells". Eur. J. Neurosci. 30 (5): 756–68. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06869.x. PMC 2774892. PMID 19712094.

- ^ Durnin L, Dai Y, Aiba I, Shuttleworth CW, Yamboliev IA, Mutafova-Yambolieva VN (2012). "Release, neuronal effects and removal of extracellular β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (β-NAD+) in the rat brain". Eur. J. Neurosci. 35 (3): 423–35. doi:10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07957.x. PMC 3270379. PMID 22276961.

- ^ Wang C, Zhou M, Zhang X, Yao J, Zhang Y, Mou Z (2017). "A lectin receptor kinase as a potential sensor for extracellular nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide in Arabidopsis thaliana". eLife. 6 e25474. doi:10.7554/eLife.25474. PMC 5560858. PMID 28722654.

- ^ Sauve AA (March 2008). "NAD+ and vitamin B3: from metabolism to therapies". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 324 (3): 883–893. doi:10.1124/jpet.107.120758. PMID 18165311. S2CID 875753.

- ^ Khan JA, Forouhar F, Tao X, Tong L (2007). "Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide metabolism as an attractive target for drug discovery". Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 11 (5): 695–705. doi:10.1517/14728222.11.5.695. PMID 17465726. S2CID 6490887.

- ^ Yaku K, Okabe K, Hikosaka K, Nakagawa T (2018). "NAD Metabolism in Cancer Therapeutics". Frontiers in Microbiology. 8 622. doi:10.3389/fonc.2018.00622. PMC 6315198. PMID 30631755.

- ^ Pramono AA, Rather GM, Herman H (2020). "NAD- and NADPH-Contributing Enzymes as Therapeutic Targets in Cancer: An Overview". Biomolecules. 10 (3): 358. doi:10.3390/biom10030358. PMC 7175141. PMID 32111066.

- ^ Penberthy, W. Todd; Tsunoda, Ikuo (2009). "The importance of NAD in multiple sclerosis". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 15 (1): 64–99. doi:10.2174/138161209787185751. ISSN 1873-4286. PMC 2651433. PMID 19149604.

- ^ Swerdlow RH (1998). "Is NADH effective in the treatment of Parkinson's disease?". Drugs Aging. 13 (4): 263–268. doi:10.2165/00002512-199813040-00002. PMID 9805207. S2CID 10683162.

- ^ Timmins GS, Deretic V (2006). "Mechanisms of action of isoniazid". Mol. Microbiol. 62 (5): 1220–1227. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05467.x. PMID 17074073. S2CID 43379861.

- ^ Rawat R, Whitty A, Tonge PJ (2003). "The isoniazid-NAD adduct is a slow, tight-binding inhibitor of InhA, the Mycobacterium tuberculosis enoyl reductase: Adduct affinity and drug resistance". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 (24): 13881–13886. Bibcode:2003PNAS..10013881R. doi:10.1073/pnas.2235848100. PMC 283515. PMID 14623976.

- ^ Argyrou A, Vetting MW, Aladegbami B, Blanchard JS (2006). "Mycobacterium tuberculosis dihydrofolate reductase is a target for isoniazid". Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13 (5): 408–413. doi:10.1038/nsmb1089. PMID 16648861. S2CID 7721666.

- ^ a b Pankiewicz KW, Patterson SE, Black PL, Jayaram HN, Risal D, Goldstein BM, Stuyver LJ, Schinazi RF (2004). "Cofactor mimics as selective inhibitors of NAD-dependent inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH) – the major therapeutic target". Curr. Med. Chem. 11 (7): 887–900. doi:10.2174/0929867043455648. PMID 15083807.

- ^ Franchetti P, Grifantini M (1999). "Nucleoside and non-nucleoside IMP dehydrogenase inhibitors as antitumor and antiviral agents". Curr. Med. Chem. 6 (7): 599–614. doi:10.2174/092986730607220401123801. PMID 10390603. S2CID 247868867.

- ^ Kim EJ, Um SJ (2008). "SIRT1: roles in aging and cancer". BMB Rep. 41 (11): 751–756. doi:10.5483/BMBRep.2008.41.11.751. PMID 19017485.

- ^ Valenzano DR, Terzibasi E, Genade T, Cattaneo A, Domenici L, Cellerino A (2006). "Resveratrol prolongs lifespan and retards the onset of age-related markers in a short-lived vertebrate". Curr. Biol. 16 (3): 296–300. Bibcode:2006CBio...16..296V. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.12.038. hdl:11384/14713. PMID 16461283. S2CID 1662390.

- ^ Howitz KT, Bitterman KJ, Cohen HY, Lamming DW, Lavu S, Wood JG, Zipkin RE, Chung P, Kisielewski A, Zhang LL, Scherer B, Sinclair DA (2003). "Small molecule activators of sirtuins extend Saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan". Nature. 425 (6954): 191–196. Bibcode:2003Natur.425..191H. doi:10.1038/nature01960. PMID 12939617. S2CID 4395572.

- ^ Wood JG, Rogina B, Lavu S, Howitz K, Helfand SL, Tatar M, Sinclair D (2004). "Sirtuin activators mimic caloric restriction and delay ageing in metazoans". Nature. 430 (7000): 686–689. Bibcode:2004Natur.430..686W. doi:10.1038/nature02789. PMID 15254550. S2CID 52851999.

- ^ Gomes AP, Price NL, Ling AJ, Moslehi JJ, Montgomery MK, Rajman L, White JP, Teodoro JS, Wrann CD, Hubbard BP, Mercken EM, Palmeira CM, de Cabo R, Rolo AP, Turner N, Bell EL, Sinclair DA (19 December 2013). "Declining NAD+ Induces a Pseudohypoxic State Disrupting Nuclear-Mitochondrial Communication during Aging". Cell. 155 (7): 1624–1638. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.037. PMC 4076149. PMID 24360282.

- ^ Rizzi M, Schindelin H (2002). "Structural biology of enzymes involved in NAD and molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis". Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 12 (6): 709–720. doi:10.1016/S0959-440X(02)00385-8. PMID 12504674.

- ^ Begley, Tadhg P.; Kinsland, Cynthia; Mehl, Ryan A.; Osterman, Andrei; Dorrestein, Pieter (2001). "The biosynthesis of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotides in bacteria". Cofactor Biosynthesis. Vitamins & Hormones. Vol. 61. pp. 103–119. doi:10.1016/S0083-6729(01)61003-3. ISBN 978-0-12-709861-6. PMID 11153263.

- ^ "Meningitis Lab Manual: ID and Characterization of Hib". CDC. 30 March 2021.

- ^ Das, Shanti (23 February 2025). "'It's not ethical and it's not medical': how UK rehab clinics are cashing in on NAD+". The Observer.

- ^ Harden, A; Young, WJ (24 October 1906). "The alcoholic ferment of yeast-juice Part II.--The coferment of yeast-juice". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Containing Papers of a Biological Character. 78 (526): 369–375. doi:10.1098/rspb.1906.0070. JSTOR 80144.

- ^ "Fermentation of sugars and fermentative enzymes" (PDF). Nobel Lecture, 23 May 1930. Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 30 September 2007.

- ^ Warburg O, Christian W (1936). "Pyridin, der wasserstoffübertragende bestandteil von gärungsfermenten (pyridin-nucleotide)" [Pyridin, the hydrogen-transferring component of the fermentation enzymes (pyridine nucleotide)]. Biochemische Zeitschrift (in German). 287: 291. doi:10.1002/hlca.193601901199.

- ^ Elvehjem CA, Madden RJ, Strong FM, Woolley DW (1938). "The isolation and identification of the anti-black tongue factor". J. Biol. Chem. 123 (1): 137–49. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)74164-1.

- ^ Axelrod AE, Madden RJ, Elvehjem CA (1939). "The effect of a nicotinic acid deficiency upon the coenzyme I content of animal tissues". J. Biol. Chem. 131 (1): 85–93. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)73482-0.

- ^ Kornberg A (1948). "The participation of inorganic pyrophosphate in the reversible enzymatic synthesis of diphosphopyridine nucleotide". J. Biol. Chem. 176 (3): 1475–76. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)57167-2. PMID 18098602.

- ^ Friedkin M, Lehninger AL (1 April 1949). "Esterification of inorganic phosphate coupled to electron transport between dihydrodiphosphopyridine nucleotide and oxygen". J. Biol. Chem. 178 (2): 611–23. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)56879-4. PMID 18116985.

- ^ Preiss J, Handler P (1958). "Biosynthesis of diphosphopyridine nucleotide. I. Identification of intermediates". J. Biol. Chem. 233 (2): 488–92. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)64789-1. PMID 13563526.

- ^ Preiss J, Handler P (1958). "Biosynthesis of diphosphopyridine nucleotide. II. Enzymatic aspects". J. Biol. Chem. 233 (2): 493–500. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)64790-8. PMID 13563527.

- ^ Bieganowski, P; Brenner, C (2004). "Discoveries of Nicotinamide Riboside as a Nutrient and Conserved NRK Genes Establish a Preiss-Handler Independent Route to NAD+ in Fungi and Humans". Cell. 117 (4): 495–502. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00416-7. PMID 15137942. S2CID 4642295.

- ^ Chambon P, Weill JD, Mandel P (1963). "Nicotinamide mononucleotide activation of new DNA-dependent polyadenylic acid synthesizing nuclear enzyme". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 11 (1): 39–43. Bibcode:1963BBRC...11...39C. doi:10.1016/0006-291X(63)90024-X. PMID 14019961.

- ^ Clapper DL, Walseth TF, Dargie PJ, Lee HC (15 July 1987). "Pyridine nucleotide metabolites stimulate calcium release from sea urchin egg microsomes desensitized to inositol trisphosphate". J. Biol. Chem. 262 (20): 9561–8. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)47970-7. PMID 3496336.

- ^ Imai S, Armstrong CM, Kaeberlein M, Guarente L (2000). "Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase". Nature. 403 (6771): 795–800. Bibcode:2000Natur.403..795I. doi:10.1038/35001622. PMID 10693811. S2CID 2967911.

- ^ Imai S (2009). "The NAD World: a new systemic regulatory network for metabolism and aging--Sirt1, systemic NAD biosynthesis, and their importance". Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics. 53 (2): 65–74. doi:10.1007/s12013-008-9041-4. PMC 2734380. PMID 19130305.

- ^ Imai S (2016). "The NAD World 2.0: the importance of the inter-tissue communication mediated by NAMPT/NAD +/SIRT1 in mammalian aging and longevity control". npj Systems Biology and Applications. 2 16018. doi:10.1038/npjsba.2016.18. PMC 5516857. PMID 28725474.

- ^ "Napa Therapeutics Formed to Develop Drugs to Influence NAD Metabolism". Fight Aging!. 17 August 2018. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

Further reading

[edit]Function

[edit]- Nelson DL; Cox MM (2004). Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry (4th ed.). W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-4339-2.

- Bugg T (2004). Introduction to Enzyme and Coenzyme Chemistry (2nd ed.). Blackwell Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4051-1452-3.

- Lee HC (2002). Cyclic ADP-Ribose and NAADP: Structure, Metabolism and Functions. Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4020-7281-9.

- Levine OS, Schuchat A, Schwartz B, Wenger JD, Elliott J (1997). "Generic protocol for population-based surveillance of Haemophilus influenzae type B" (PDF). World Health Organization. Centers for Disease Control. p. 13. WHO/VRD/GEN/95.05. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 July 2004.

- Kim, Jinhyun; Lee, Sahng Ha; Tieves, Florian; Paul, Caroline E.; Hollmann, Frank; Park, Chan Beum (5 July 2019). "Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide as a photocatalyst". Science Advances. 5 (7) eaax0501. Bibcode:2019SciA....5..501K. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aax0501. PMC 6641943. PMID 31334353.

History

[edit]- Cornish-Bowden, Athel (1997). New Beer in an Old Bottle. Eduard Buchner and the Growth of Biochemical Knowledge. Valencia: Universitat de Valencia. ISBN 978-84-370-3328-0. Archived from the original on 13 December 2010. Retrieved 8 December 2007., A history of early enzymology.

- Williams, Henry Smith (1904). Modern Development of the Chemical and Biological Sciences. A History of Science: in Five Volumes. Vol. IV. New York: Harper and Brothers., a textbook from the 19th century.

External links

[edit]- NAD bound to proteins in the Protein Data Bank

- NAD Animation (Flash Required)

- β-Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+, oxidized) and NADH (reduced) Chemical data sheet from Sigma-Aldrich

- NAD+, NADH and NAD synthesis pathway at the MetaCyc database

- List of oxidoreductases Archived 30 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine at the SWISS-PROT database

- NAD+

- NAD+ The Molecule of Youth