Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Pericyte

View on Wikipedia| Pericyte | |

|---|---|

Transmission electron micrograph of a microvessel displaying pericytes that are lining the outer surface of endothelial cells that are encircling an erythrocyte (E). | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | pericytus |

| MeSH | D020286 |

| TH | H3.09.02.0.02006 |

| FMA | 63174 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

Pericytes (formerly called Rouget cells)[1] are multi-functional mural cells of the microcirculation that wrap around the endothelial cells that line the capillaries throughout the body.[2] Pericytes are embedded in the basement membrane of blood capillaries, where they communicate with endothelial cells by means of both direct physical contact and paracrine signaling.[3] The morphology, distribution, density and molecular fingerprints of pericytes vary between organs and vascular beds.[4][5] Pericytes help in the maintainenance of homeostatic and hemostatic functions in the brain, where one of the organs is characterized with a higher pericyte coverage, and also sustain the blood–brain barrier.[6] These cells are also a key component of the neurovascular unit, which includes endothelial cells, astrocytes, and neurons.[7][8] Pericytes have been postulated to regulate capillary blood flow [9][10][11][12] and the clearance and phagocytosis of cellular debris in vitro.[13] Pericytes stabilize and monitor the maturation of endothelial cells by means of direct communication between the cell membrane as well as through paracrine signaling.[14] A deficiency of pericytes in the central nervous system can cause increased permeability of the blood–brain barrier.[6]

Structure

[edit]

In the central nervous system (CNS), pericytes wrap around the endothelial cells that line the inside of the capillary. These two types of cells can be easily distinguished from one another based on the presence of the prominent round nucleus of the pericyte compared to the flat elongated nucleus of the endothelial cells.[7] Pericytes also project finger-like extensions that wrap around the capillary wall, allowing the cells to regulate capillary blood flow.[6]

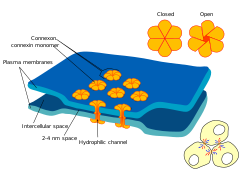

Both pericytes and endothelial cells share a basement membrane where a variety of intercellular connections are made. Many types of integrin molecules facilitate communication between pericytes and endothelial cells separated by the basement membrane.[6] Pericytes can also form direct connections with neighboring cells by forming peg and socket arrangements in which parts of the cells interlock, similar to the gears of a clock. At these interlocking sites, gap junctions can be formed, which allow the pericytes and neighboring cells to exchange ions and other small molecules.[6] Important molecules in these intercellular connections include N-cadherin, fibronectin, connexin and various integrins.[7]

In some regions of the basement membrane, adhesion plaques composed of fibronectin can be found. These plaques facilitate the connection of the basement membrane to the cytoskeletal structure composed of actin, and the plasma membrane of the pericytes and endothelial cells.[6]

Function

[edit]Skeletal muscle regeneration and fat formation

[edit]Pericytes in the skeletal striated muscle are of two distinct populations, each with its own role.[15] The first pericyte subtype (Type-1) can differentiate into fat cells while the other (Type-2) into muscle cells. Type-1 characterized by negative expression for nestin (PDGFRβ+CD146+Nes-) and type-2 characterized by positive expression for nestin (PDGFRβ+CD146+Nes+). While both types are able to proliferate in response to glycerol or BaCl2-induced injury, type-1 pericytes give rise to adipogenic cells only in response to glycerol injection and type-2 become myogenic in response to both types of injury.[16] The extent to which type-1 pericytes participate in fat accumulation is not known.

Angiogenesis and the survival of endothelial cells

[edit]Pericytes are also associated with endothelial cell differentiation and multiplication, angiogenesis, survival of apoptotic signals and travel. Certain pericytes, known as microvascular pericytes, develop around the walls of capillaries and help to serve this function. Microvascular pericytes may not be contractile cells, as they lack alpha-actin isoforms, structures that are common amongst other contractile cells. These cells communicate with endothelial cells via gap junctions, and in turn cause endothelial cells to proliferate or be selectively inhibited. If this process did not occur, hyperplasia and abnormal vascular morphogenesis could result. These types of pericyte can also phagocytose exogenous proteins. This suggests that the cell type might have been derived from microglia.[17]

A lineage relationship to other cell types has been proposed, including smooth muscle cells,[18] neural cells,[18] NG2 glia,[19] muscle fibers, adipocytes, as well as fibroblasts[20] and other mesenchymal stem cells. However, whether these cells differentiate into each other is an outstanding question in the field. Pericytes' regenerative capacity is affected by aging.[20] Such versatility is useful, as they actively remodel blood vessels throughout the body and can thereby blend homogeneously with the local tissue environment.[21]

Aside from creating and remodeling blood vessels, pericytes have been found to protect endothelial cells from death via apoptosis or cytotoxic elements. It has been shown in vivo that pericytes release a hormone known as pericytic aminopeptidase N/pAPN that may help to promote angiogenesis. When this hormone was mixed with cerebral endothelial cells as well as astrocytes, the pericytes grouped into structures that resembled capillaries. Furthermore, when the experimental group contained all of the following with the exception of pericytes, the endothelial cells would undergo apoptosis. [further explanation needed] It was thus concluded that pericytes must be present to ensure the proper function of endothelial cells, and astrocytes must be present to ensure that both remain in contact. If not, then proper angiogenesis cannot occur.[22] It has also been found that pericytes contribute to the survival of endothelial cells, as they secrete the protein Bcl-w during cellular crosstalk. Bcl-w is an instrumental protein in the pathway that enforces VEGF-A expression and discourages apoptosis.[23] Although there is some speculation as to why VEGF is directly responsible for preventing apoptosis, it is believed to be responsible for modulating apoptotic signal transduction pathways and inhibiting activation of apoptosis-inducing enzymes. Two biochemical mechanisms utilized by VEGF to accomplish this would be phosphorylation of extracellular regulatory kinase 1 (ERK-1, also known as MAPK3), which sustains cell survival over time, and inhibition of stress-activated protein kinase/c-jun-NH2 kinase, which also promotes apoptosis.[24]

Blood–brain barrier

[edit]Pericytes play a crucial role in the formation and functionality of the blood–brain barrier. This barrier is composed of endothelial cells and ensures the protection and functionality of the brain and central nervous system. It has been found that pericytes are crucial to the postnatal formation of this barrier. Pericytes are responsible for tight junction formation and vesicle trafficking amongst endothelial cells. Furthermore, they allow the formation of the blood–brain barrier by inhibiting the effects of CNS immune cells (which can damage the formation of the barrier) and by reducing the expression of molecules that increase vascular permeability.[25]

Aside from blood–brain barrier formation, pericytes also play an active role in its functionality. Animal models of developmental loss of pericytes show increased endothelial transcytosis, as well as skewed arterio-venous zonation, increased expression of leukocyte adhesion molecules and microaneurysms.[26][27] Loss or dysfunction of pericytes is also theorized to contribute to neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's,[28][29][30] Parkinson's and ALS[31] through breakdown of the blood-brain barrier.

Blood flow

[edit]Increasing evidence suggests that pericytes can regulate blood flow at the capillary level. For the retina, movies have been published[12] showing that pericytes constrict capillaries when their membrane potential is altered to cause calcium influx, and in the brain it has been reported that neuronal activity increases local blood flow by inducing pericytes to dilate capillaries before upstream arteriole dilation occurs.[11] This area is controversial, with a 2015 study claiming that pericytes do not express contractile proteins and are not capable of contraction in vivo,[10] although the latter paper has been criticised for using a highly unconventional definition of pericyte which explicitly excludes contractile pericytes.[32] It appears that different signaling pathways regulate the constriction of capillaries by pericytes and of arterioles by smooth muscle cells.[33] Recent studies on rats have found such a signaling pathway in which after spinal cord injury and induced hypoxia below the injury, there is excess activity of monoamine receptors on pericytes which locally constricts capillaries and reduces blood flow to ischemic levels.[34]

Pericytes are important in maintaining circulation. In a study involving adult pericyte-deficient mice, cerebral blood flow was diminished with concurrent vascular regression due to loss of both endothelia and pericytes. Significantly greater hypoxia was reported in the hippocampus of pericyte-deficient mice as well as inflammation, and learning and memory impairment.[35]

Clinical significance

[edit]Because of their crucial role in maintaining and regulating endothelial cell structure and blood flow, abnormalities in pericyte function are seen in many pathologies. They may either be present in excess, leading to diseases such as hypertension and tumor formation, or in deficiency, leading to neurodegenerative diseases.

Hemangioma

[edit]The clinical phases of hemangioma have physiological differences, correlated with immunophenotypic profiles by Takahashi et al. During the early proliferative phase (0–12 months) the tumors express proliferating cell nuclear antigen (pericytesna), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and type IV collagenase, the former two localized to both endothelium and pericytes, and the last to endothelium. The vascular markers CD31, von Willebrand factor (vWF), and smooth muscle actin (pericyte marker) are present during the proliferating and involuting phases, but are lost after the lesion is fully involuted.[36]

Hemangiopericytoma

[edit]

Hemangiopericytoma is a rare vascular neoplasm, or abnormal growth, that may either be benign or malignant. In its malignant form, metastasis to the lungs, liver, brain, and extremities may occur. It most commonly manifests itself in the femur and proximal tibia as a bone sarcoma, and is usually found in older individuals, though cases have been found in children. Hemangiopericytoma is caused by the excessive layering of sheets of pericytes around improperly formed blood vessels. Diagnosis of this tumor is difficult because of the inability to distinguish pericytes from other types of cells using light microscopy. Treatment may involve surgical removal and radiation therapy, depending on the level of bone penetration and stage in the tumor's development.[37]

Diabetic retinopathy

[edit]The retina of diabetic individuals often exhibits loss of pericytes, and this loss is a characteristic factor of the early stages of diabetic retinopathy. Studies have found that pericytes are essential in diabetic individuals to protect the endothelial cells of retinal capillaries. With the loss of pericytes, microaneurysms form in the capillaries. In response, the retina either increases its vascular permeability, leading to swelling of the eye through a macular edema, or forms new vessels that permeate into the vitreous membrane of the eye. The end result is reduction or loss of vision.[38] While it is unclear why pericytes are lost in diabetic patients, one hypothesis is that toxic sorbitol and advanced glycation end-products (AGE) accumulate in the pericytes. Because of the build-up of glucose, the polyol pathway increases its flux, and intracellular sorbitol and fructose accumulate. This leads to osmotic imbalance, which results in cellular damage. The presence of high glucose levels also leads to the buildup of AGE's, which also damage cells.[39]

Neurodegenerative diseases

[edit]Studies have found that pericyte loss in the adult and aging brain leads to the disruption of proper cerebral perfusion and maintenance of the blood–brain barrier, which causes neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation.[citation needed] The apoptosis of pericytes in the aging brain may be the result of a failure in communication between growth factors and receptors on pericytes. Platelet-derived growth factor B (PDGFB) is released from endothelial cells in brain vasculature and binds to the receptor PDGFRB on pericytes, initiating their proliferation and investment in the vasculature.

Immunohistochemical studies of human tissue from Alzheimer's disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis show pericyte loss and breakdown of the blood-brain barrier. Pericyte-deficient mouse models (which lack genes encoding steps in the PDGFB:PDGFRB signalling cascade) and have an Alzheimer's-causing mutation have exacerbated Alzheimer's-like pathology compared to mice with normal pericyte coverage and an Alzheimer's-causing mutation.

Stroke

[edit]In conditions of stroke, pericytes constrict brain capillaries and then die, which may lead to a long-lasting decrease of blood flow and loss of blood–brain barrier function, increasing the death of nerve cells.[11]

Research

[edit]Endothelial and pericyte interactions

[edit]Endothelial cells and pericytes are interdependent and failure of proper communication between the two cell types can lead to numerous human pathologies.[40]

There are several pathways of communication between the endothelial cells and pericytes. The first is transforming growth factor (TGF) signaling, which is mediated by endothelial cells. This is important for pericyte differentiation.[41][42] Angiopoietin 1 and Tie-2 signaling is essential for maturation and stabilization of endothelial cells.[43] Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) pathway signaling from endothelial cells recruits pericytes, so that pericytes can migrate to developing blood vessels. If this pathway is blocked, it leads to pericyte deficiency.[44] Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) signaling also aids in pericyte recruitment by communication through G protein-coupled receptors. S1P sends signals through GTPases that promote N-cadherin trafficking to endothelial membranes. This trafficking strengthens endothelial contacts with pericytes.[45]

Communication between endothelial cells and pericytes is vital. Inhibiting the PDGF pathway leads to pericyte deficiency. This causes endothelial hyperplasia, abnormal junctions, and diabetic retinopathy.[38] A lack of pericytes also causes an upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), leading to vascular leakage and hemorrhage.[46] Angiopoietin 2 can act as an antagonist to Tie-2,[47] destabilizing the endothelial cells, which results in less endothelial cell and pericyte interaction. This occasionally leads to the formation of tumors.[48] Similar to the inhibition of the PDGF pathway, angiopoietin 2 reduces levels of pericytes, leading to diabetic retinopathy.[49]

Scarring

[edit]Usually, astrocytes are associated with the scarring process in the central nervous system, forming glial scars. It has been proposed that a subtype of pericytes participates in this scarring in a glial-independent manner. Through lineage tracking studies, these subtype of pericytes were followed after stroke, revealing that they contribute to the glial scar by differentiating into myofibroblasts and depositing extracellular matrix.[50] However, this remains controversial, as more recent studies suggest that the cell type followed in these scar studies is likely to be not pericytes, but fibroblasts.[51][52]

Contribution to adult neurogenesis

[edit]The emerging evidence (as of 2019) suggests that neural microvascular pericytes, under instruction from resident glial cells, are reprogrammed into interneurons and enrich local neuronal microcircuits.[53] This response is amplified by concomitant angiogenesis.

See also

[edit]- Hemangiopericytoma

- Mesoangioblast

- Diabetic retinopathy caused by death of pericytes

- List of human cell types derived from the germ layers

References

[edit]- ^ Dore-Duffy, P. (2008). "Pericytes: Pluripotent cells of the blood brain barrier". Current Pharmaceutical Design. 14 (16): 1581–93. doi:10.2174/138161208784705469. PMID 18673199.

- ^ Birbrair A, Zhang T, Wang ZM, Messi ML, Mintz A, Delbono O (January 2015). "Pericytes at the intersection between tissue regeneration and pathology". Clinical Science. 128 (2): 81–93. doi:10.1042/CS20140278. PMC 4200531. PMID 25236972.

- ^ Bergers G, Song S (October 2005). "The role of pericytes in blood-vessel formation and maintenance". Neuro-Oncology. 7 (4): 452–64. doi:10.1215/S1152851705000232. PMC 1871727. PMID 16212810.

- ^ Sims, David E. (January 1986). "The pericyte—A review". Tissue and Cell. 18 (2): 153–174. doi:10.1016/0040-8166(86)90026-1. PMID 3085281.

- ^ Muhl, Lars; Genové, Guillem; Leptidis, Stefanos; Liu, Jianping; He, Liqun; Mocci, Giuseppe; Sun, Ying; Gustafsson, Sonja; Buyandelger, Byambajav; Chivukula, Indira V.; Segerstolpe, Åsa (December 2020). "Single-cell analysis uncovers fibroblast heterogeneity and criteria for fibroblast and mural cell identification and discrimination". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 3953. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.3953M. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-17740-1. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7414220. PMID 32769974.

- ^ a b c d e f Winkler EA, Bell RD, Zlokovic BV (October 2011). "Central nervous system pericytes in health and disease". Nature Neuroscience. 14 (11): 1398–1405. doi:10.1038/nn.2946. PMC 4020628. PMID 22030551.

- ^ a b c Dore-Duffy P, Cleary K (2011). "Morphology and properties of pericytes". The Blood-Brain and Other Neural Barriers. Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 686. pp. 49–68. doi:10.1007/978-1-60761-938-3_2. ISBN 978-1-60761-937-6. PMID 21082366.

- ^ Liebner S, Czupalla CJ, Wolburg H (2011). "Current concepts of blood-brain barrier development". The International Journal of Developmental Biology. 55 (4–5): 467–76. doi:10.1387/ijdb.103224sl. PMID 21769778.

- ^ Hartmann, David A.; Berthiaume, Andrée-Anne; Grant, Roger I.; Harrill, Sarah A.; Koski, Tegan; Tieu, Taryn; McDowell, Konnor P.; Faino, Anna V.; Kelly, Abigail L.; Shih, Andy Y. (May 2021). "Brain capillary pericytes exert a substantial but slow influence on blood flow". Nature Neuroscience. 24 (5): 633–645. doi:10.1038/s41593-020-00793-2. ISSN 1097-6256. PMC 8102366. PMID 33603231.

- ^ a b Hill RA, Tong L, Yuan P, Murikinati S, Gupta S, Grutzendler J (July 2015). "Regional Blood Flow in the Normal and Ischemic Brain Is Controlled by Arteriolar Smooth Muscle Cell Contractility and Not by Capillary Pericytes". Neuron. 87 (1): 95–110. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2015.06.001. PMC 4487786. PMID 26119027.

- ^ a b c Hall CN, Reynell C, Gesslein B, Hamilton NB, Mishra A, Sutherland BA, O'Farrell FM, Buchan AM, Lauritzen M, Attwell D (April 2014). "Capillary pericytes regulate cerebral blood flow in health and disease". Nature. 508 (7494): 55–60. Bibcode:2014Natur.508...55H. doi:10.1038/nature13165. PMC 3976267. PMID 24670647.

- ^ a b Peppiatt CM, Howarth C, Mobbs P, Attwell D (October 2006). "Bidirectional control of CNS capillary diameter by pericytes". Nature. 443 (7112): 700–4. Bibcode:2006Natur.443..700P. doi:10.1038/nature05193. PMC 1761848. PMID 17036005.

- ^ Rustenhoven, Justin; Smyth, Leon C.; Jansson, Deidre; Schweder, Patrick; Aalderink, Miranda; Scotter, Emma L.; Mee, Edward W.; Faull, Richard L. M.; Park, Thomas I.-H.; Dragunow, Mike (December 2018). "Modelling physiological and pathological conditions to study pericyte biology in brain function and dysfunction". BMC Neuroscience. 19 (1): 6. doi:10.1186/s12868-018-0405-4. ISSN 1471-2202. PMC 5824614. PMID 29471788.

- ^ Fakhrejahani E, Toi M (2012). "Tumor angiogenesis: pericytes and maturation are not to be ignored". Journal of Oncology. 2012: 1–10. doi:10.1155/2012/261750. PMC 3191787. PMID 22007214.

- ^ Birbrair, Alexander; Zhang, Tan; Wang, Zhong-Min; Messi, Maria Laura; Enikolopov, Grigori N.; Mintz, Akiva; Delbono, Osvaldo (January 27, 2013). "Skeletal muscle pericyte subtypes differ in their differentiation potential". Stem Cell Research. 10 (1): 67–84. doi:10.1016/j.scr.2012.09.003. PMC 3781014. PMID 23128780.

- ^ Birbrair, Alexander; Zhang, Tan; Wang, Zhong-Min; Messi, Maria Laura; Mintz, Akiva; Delbono, Osvaldo (December 1, 2013). "Type-1 pericytes participate in fibrous tissue deposition in aged skeletal muscle". American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology. 305 (11): C1098–1113. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00171.2013. PMC 3882385. PMID 24067916.

- ^ "Pericyte, Astrocyte and Basal Lamina Association with the Blood Brain Barrier (BBB)". University of Arizona Health Sciences. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017.

- ^ a b Birbrair A, Zhang T, Wang ZM, Messi ML, Enikolopov GN, Mintz A, Delbono O (January 2013). "Skeletal muscle pericyte subtypes differ in their differentiation potential". Stem Cell Research. 10 (1): 67–84. doi:10.1016/j.scr.2012.09.003. PMC 3781014. PMID 23128780.

- ^ Birbrair A, Zhang T, Wang ZM, Messi ML, Enikolopov GN, Mintz A, Delbono O (January 2013). "Skeletal muscle neural progenitor cells exhibit properties of NG2-glia". Experimental Cell Research. 319 (1): 45–63. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.09.008. PMC 3597239. PMID 22999866.

- ^ a b Birbrair A, Zhang T, Wang ZM, Messi ML, Mintz A, Delbono O (December 2013). "Type-1 pericytes participate in fibrous tissue deposition in aged skeletal muscle". American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology. 305 (11): C1098–113. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00171.2013. PMC 3882385. PMID 24067916.

- ^ Gerhardt H, Betsholtz C (October 2003). "Endothelial-pericyte interactions in angiogenesis". Cell and Tissue Research. 314 (1): 15–23. doi:10.1007/s00441-003-0745-x. PMID 12883993. S2CID 24258796.

- ^ Ramsauer M, Krause D, Dermietzel R (August 2002). "Angiogenesis of the blood-brain barrier in vitro and the function of cerebral pericytes". FASEB Journal. 16 (10): 1274–6. doi:10.1096/fj.01-0814fje. PMID 12153997. S2CID 37606009.

- ^ Franco M, Roswall P, Cortez E, Hanahan D, Pietras K (September 2011). "Pericytes promote endothelial cell survival through induction of autocrine VEGF-A signaling and Bcl-w expression". Blood. 118 (10): 2906–17. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-01-331694. PMC 3172806. PMID 21778339.

- ^ Gupta K, Kshirsagar S, Li W, Gui L, Ramakrishnan S, Gupta P, Law PY, Hebbel RP (March 1999). "VEGF prevents apoptosis of human microvascular endothelial cells via opposing effects on MAPK/ERK and SAPK/JNK signaling". Experimental Cell Research. 247 (2): 495–504. doi:10.1006/excr.1998.4359. PMID 10066377.

- ^ Daneman R, Zhou L, Kebede AA, Barres BA (November 2010). "Pericytes are required for blood-brain barrier integrity during embryogenesis". Nature. 468 (7323): 562–6. Bibcode:2010Natur.468..562D. doi:10.1038/nature09513. PMC 3241506. PMID 20944625.

- ^ Armulik A, Genové G, Mäe M, Nisancioglu MH, Wallgard E, Niaudet C, He L, Norlin J, Lindblom P, Strittmatter K, Johansson BR, Betsholtz C (November 2010). "Pericytes regulate the blood-brain barrier". Nature. 468 (7323): 557–61. Bibcode:2010Natur.468..557A. doi:10.1038/nature09522. hdl:10616/40288. PMID 20944627. S2CID 4429989.

- "Key to blood-brain barrier opens way for treating Alzheimer's and stroke". Karolinska Institutet. October 14, 2010. Archived from the original on 2014-02-01.

- ^ Mäe, Maarja A.; He, Liqun; Nordling, Sofia; Vazquez-Liebanas, Elisa; Nahar, Khayrun; Jung, Bongnam; Li, Xidan; Tan, Bryan C.; Chin Foo, Juat; Cazenave-Gassiot, Amaury; Wenk, Markus R. (2021-02-19). "Single-Cell Analysis of Blood-Brain Barrier Response to Pericyte Loss". Circulation Research. 128 (4): e46 – e62. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317473. ISSN 0009-7330. PMC 10858745. PMID 33375813. S2CID 229721934.

- ^ Halliday, Matthew R; Rege, Sanket V; Ma, Qingyi; Zhao, Zhen; Miller, Carol A; Winkler, Ethan A; Zlokovic, Berislav V (January 2016). "Accelerated pericyte degeneration and blood–brain barrier breakdown in apolipoprotein E4 carriers with Alzheimer's disease". Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 36 (1): 216–227. doi:10.1038/jcbfm.2015.44. ISSN 0271-678X. PMC 4758554. PMID 25757756.

- ^ Miners, J Scott; Schulz, Isabel; Love, Seth (January 2018). "Differing associations between Aβ accumulation, hypoperfusion, blood–brain barrier dysfunction and loss of PDGFRB pericyte marker in the precuneus and parietal white matter in Alzheimer's disease". Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 38 (1): 103–115. doi:10.1177/0271678X17690761. ISSN 0271-678X. PMC 5757436. PMID 28151041.

- ^ Sengillo, Jesse D.; Winkler, Ethan A.; Walker, Corey T.; Sullivan, John S.; Johnson, Mahlon; Zlokovic, Berislav V. (May 2013). "Deficiency in Mural Vascular Cells Coincides with Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption in Alzheimer's Disease: Pericytes in Alzheimer's Disease". Brain Pathology. 23 (3): 303–310. doi:10.1111/bpa.12004. PMC 3628957. PMID 23126372.

- ^ Winkler, Ethan A.; Sengillo, Jesse D.; Sullivan, John S.; Henkel, Jenny S.; Appel, Stanley H.; Zlokovic, Berislav V. (January 2013). "Blood–spinal cord barrier breakdown and pericyte reductions in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Acta Neuropathologica. 125 (1): 111–120. doi:10.1007/s00401-012-1039-8. ISSN 0001-6322. PMC 3535352. PMID 22941226.

- ^ Attwell D, Mishra A, Hall CN, O'Farrell FM, Dalkara T (February 2016). "What is a pericyte?". Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 36 (2): 451–5. doi:10.1177/0271678x15610340. PMC 4759679. PMID 26661200.

- ^ Mishra A, Reynolds JP, Chen Y, Gourine AV, Rusakov DA, Attwell D (December 2016). "Astrocytes mediate neurovascular signaling to capillary pericytes but not to arterioles". Nature Neuroscience. 19 (12): 1619–1627. doi:10.1038/nn.4428. PMC 5131849. PMID 27775719.

- ^ Li, Yaqing; Lucas-Osma, Ana M.; Black, Sophie; Bandet, Mischa V.; Stephens, Marilee J.; Vavrek, Romana; Sanelli, Leo; Fenrich, Keith K.; Di Narzo, Antonio F.; Dracheva, Stella; Winship, Ian R.; Fouad, Karim; Bennett, David J. (June 2017). "Pericytes impair capillary blood flow and motor function after chronic spinal cord injury". Nature Medicine. 23 (6): 733–741. doi:10.1038/nm.4331. ISSN 1546-170X. PMC 5716958. PMID 28459438.

- ^ Bell RD, Winkler EA, Sagare AP, Singh I, LaRue B, Deane R, Zlokovic BV (November 2010). "Pericytes control key neurovascular functions and neuronal phenotype in the adult brain and during brain aging". Neuron. 68 (3): 409–27. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.043. PMC 3056408. PMID 21040844.

- ^ Munde P. "Pericytes in Health and Disease". Celesta Software Pvt Ltd. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ Gellman H. "Solitary Fibrous Tumor". Medscape. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ^ a b Hammes HP, Lin J, Renner O, Shani M, Lundqvist A, Betsholtz C, Brownlee M, Deutsch U (October 2002). "Pericytes and the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy". Diabetes. 51 (10): 3107–12. doi:10.2337/diabetes.51.10.3107. PMID 12351455.

- ^ Ciulla TA, Amador AG, Zinman B (September 2003). "Diabetic retinopathy and diabetic macular edema: pathophysiology, screening, and novel therapies". Diabetes Care. 26 (9): 2653–64. doi:10.2337/diacare.26.9.2653. PMID 12941734.

- ^ Armulik A, Abramsson A, Betsholtz C (September 2005). "Endothelial/pericyte interactions". Circulation Research. 97 (6): 512–23. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000182903.16652.d7. PMID 16166562.

- ^ Carvalho RL, Jonker L, Goumans MJ, Larsson J, Bouwman P, Karlsson S, Dijke PT, Arthur HM, Mummery CL (December 2004). "Defective paracrine signalling by TGFbeta in yolk sac vasculature of endoglin mutant mice: a paradigm for hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia". Development. 131 (24): 6237–47. doi:10.1242/dev.01529. PMID 15548578.

- ^ Hirschi KK, Rohovsky SA, D'Amore PA (May 1998). "PDGF, TGF-beta, and heterotypic cell-cell interactions mediate endothelial cell-induced recruitment of 10T1/2 cells and their differentiation to a smooth muscle fate". The Journal of Cell Biology. 141 (3): 805–14. doi:10.1083/jcb.141.3.805. PMC 2132737. PMID 9566978.

- ^ Thurston G, Suri C, Smith K, McClain J, Sato TN, Yancopoulos GD, McDonald DM (December 1999). "Leakage-resistant blood vessels in mice transgenically overexpressing angiopoietin-1". Science. 286 (5449): 2511–4. doi:10.1126/science.286.5449.2511. PMID 10617467.

- ^ Bjarnegård M, Enge M, Norlin J, Gustafsdottir S, Fredriksson S, Abramsson A, Takemoto M, Gustafsson E, Fässler R, Betsholtz C (April 2004). "Endothelium-specific ablation of PDGFB leads to pericyte loss and glomerular, cardiac and placental abnormalities". Development. 131 (8): 1847–57. doi:10.1242/dev.01080. PMID 15084468.

- ^ Paik JH, Skoura A, Chae SS, Cowan AE, Han DK, Proia RL, Hla T (October 2004). "Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor regulation of N-cadherin mediates vascular stabilization". Genes & Development. 18 (19): 2392–403. doi:10.1101/gad.1227804. PMC 522989. PMID 15371328.

- ^ Hellström M, Gerhardt H, Kalén M, Li X, Eriksson U, Wolburg H, Betsholtz C (April 2001). "Lack of pericytes leads to endothelial hyperplasia and abnormal vascular morphogenesis". The Journal of Cell Biology. 153 (3): 543–53. doi:10.1083/jcb.153.3.543. PMC 2190573. PMID 11331305.

- ^ Maisonpierre PC, Suri C, Jones PF, Bartunkova S, Wiegand SJ, Radziejewski C, Compton D, McClain J, Aldrich TH, Papadopoulos N, Daly TJ, Davis S, Sato TN, Yancopoulos GD (July 1997). "Angiopoietin-2, a natural antagonist for Tie2 that disrupts in vivo angiogenesis". Science. 277 (5322): 55–60. doi:10.1126/science.277.5322.55. PMID 9204896.

- ^ Zhang L, Yang N, Park JW, Katsaros D, Fracchioli S, Cao G, O'Brien-Jenkins A, Randall TC, Rubin SC, Coukos G (June 2003). "Tumor-derived vascular endothelial growth factor up-regulates angiopoietin-2 in host endothelium and destabilizes host vasculature, supporting angiogenesis in ovarian cancer". Cancer Research. 63 (12): 3403–12. PMID 12810677.

- ^ Hammes HP, Lin J, Wagner P, Feng Y, Vom Hagen F, Krzizok T, Renner O, Breier G, Brownlee M, Deutsch U (April 2004). "Angiopoietin-2 causes pericyte dropout in the normal retina: evidence for involvement in diabetic retinopathy". Diabetes. 53 (4): 1104–10. doi:10.2337/diabetes.53.4.1104. PMID 15047628.

- ^ Göritz C, Dias DO, Tomilin N, Barbacid M, Shupliakov O, Frisén J (July 2011). "A pericyte origin of spinal cord scar tissue". Science. 333 (6039): 238–42. Bibcode:2011Sci...333..238G. doi:10.1126/science.1203165. PMID 21737741. S2CID 206532774.

- ^ Soderblom C, Luo X, Blumenthal E, Bray E, Lyapichev K, Ramos J, Krishnan V, Lai-Hsu C, Park KK, Tsoulfas P, Lee JK (August 2013). "Perivascular fibroblasts form the fibrotic scar after contusive spinal cord injury". The Journal of Neuroscience. 33 (34): 13882–7. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2524-13.2013. PMC 3755723. PMID 23966707.

- ^ Vanlandewijck M, He L, Mäe MA, Andrae J, Ando K, Del Gaudio F, Nahar K, Lebouvier T, Laviña B, Gouveia L, Sun Y, Raschperger E, Räsänen M, Zarb Y, Mochizuki N, Keller A, Lendahl U, Betsholtz C (February 2018). "A molecular atlas of cell types and zonation in the brain vasculature". Nature. 554 (7693): 475–480. Bibcode:2018Natur.554..475V. doi:10.1038/nature25739. hdl:10138/301079. PMID 29443965. S2CID 205264161.

- ^ Farahani, Ramin M.; Rezaei-Lotfi, Saba; Simonian, Mary; Xaymardan, Munira; Hunter, Neil (2019). "Neural microvascular pericytes contribute to human adult neurogenesis". Journal of Comparative Neurology. 527 (4): 780–796. doi:10.1002/cne.24565. ISSN 1096-9861. PMID 30471080. S2CID 53711787.

External links

[edit]- www.stemcellsfreak.com — Pericytes can be used for muscle regeneration

- Diagram at udel.edu