Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Car dependency

View on Wikipedia

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (March 2025) |

The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (October 2025) |

Car dependency is a pattern in urban planning that occurs when infrastructure favors automobiles over other modes of transport, such as public transport, bicycles, and walking. Car dependency is associated with higher transport pollution than transport systems that treat all transportation modes equally.[1]

Car infrastructure is often paid for by governments from general taxes rather than gasoline taxes or mandated by governments.[2] For instance, many cities have minimum parking requirements for new housing, which in practice requires developers to "subsidize" drivers.[3] In some places, bicycles and rickshaws are banned from using road space, and pedestrian use of road space has been criminalized in many jurisdictions (see jaywalking) since the early 20th century. The road lobby plays an important role in maintaining car dependency, arguing that car infrastructure is good for economic growth.[1]

Description

[edit]In many modern cities, automobiles are convenient and sometimes necessary to move easily.[4][5] When it comes to automobile use, there is a spiraling effect where traffic congestion produces the 'demand' for more and bigger roads and the removal of 'impediments' to traffic flow. Examples of such impediments can for instance be pedestrians, cyclists, signalized crossings, traffic lights, various forms of street-based public transit such as buses and trams, or even houses, parks and recreational arenas.

These measures make automobile use more advantageous at the expense of other modes of transport, inducing greater traffic volumes. Additionally, the urban design of cities adjusts to the needs of automobiles in terms of movement and space. Buildings are replaced by parking lots. Open-air shopping streets are replaced by enclosed shopping malls. Walk-in banks and fast-food stores are replaced by drive-in versions of themselves that are inconveniently located for pedestrians. Town centers with a mixture of commercial, retail, and entertainment functions are replaced by single-function business parks, 'category-killer' retail boxes, and 'multiplex' entertainment complexes, each surrounded by large tracts of parking.

These kinds of environments require automobiles to access them, thus inducing even more traffic onto the increased road space. This results in congestion, and the cycle above continues. Roads get ever bigger, consuming ever greater tracts of land previously used for housing, manufacturing, and other socially and economically useful purposes. Public transit becomes less viable and socially stigmatized, eventually becoming a minority form of transportation. People's choices and freedoms to live functional lives without the use of the car are greatly reduced. Such cities are automobile-dependent.

Automobile dependency is seen primarily as an issue of environmental sustainability due to the consumption of non-renewable resources and the production of greenhouse gases responsible for global warming. It is also an issue of social and cultural sustainability. Like gated communities, the private automobile produces physical separation between people and reduces the opportunities for unstructured social encounters that is a significant aspect of social capital formation and maintenance in urban environments.

Origins of car dependency

[edit]

As automobile use rose drastically in the 1910s, American road administrators favored building roads to accommodate traffic.[6] Administrators and engineers in the interwar period spent their resources making small adjustments to accommodate traffic such as widening lanes and adding parking spaces, as opposed to larger projects that would change the built environment altogether.[6] American cities began to tear out tram systems in the 1920s. Car dependency itself saw its formation around the Second World War, when urban infrastructure began to be built exclusively around the car.[7] The resultant economic and built environment restructuring allowed wide adoption of automobile use. In the United States, the expansive manufacturing infrastructure, increase in consumerism, and the establishment of the Interstate Highway System set forth the conditions for car dependence in communities. In 1956, the Highway Trust Fund[8] was established in America, reinvesting gasoline taxes back into car-based infrastructure.

Urban design factors

[edit]Land-use (zoning)

[edit]In 1916 the first zoning ordinance was introduced in New York City, the 1916 Zoning Resolution. Zoning was created as a means of organizing specific land uses in a city so as to avoid potentially harmful adjacencies like heavy manufacturing and residential districts, which were common in large urban areas in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Zoning code also determines the permitted residential building types and densities in specific areas of a city by defining some areas as single-family zoning, and other areas where multi-family residential is allowed. The overall effect of zoning in the last century has been to create areas of the city with similar land use patterns in cities that had previously been a mix of heterogenous residential and business uses. The problem is particularly severe right outside of cities, in suburban areas located around the periphery of a city where strict zoning codes do not allow any residential types other than single family detached housing.[9] Strict zoning codes that result in a heavily segregated built environment between residential and commercial land uses contribute to car dependency by making it nearly impossible to access all one's given needs, such as housing, work, school and recreation without the use of a car. One key solution to the spatial problems caused by zoning would be a robust public transportation network.[10] There is also currently a movement to amend older zoning ordinances to create more mixed-use zones in cities that combine residential and commercial land uses within the same building or within walking distance to create the so-called 15-minute city.

Parking minimums are also a part of modern zoning codes, and contribute to car dependency through a process known as induced demand. Parking minimums require a certain number of parking spots based on the land use of a building and are often designed in zoning codes to represent the maximum possible need at any given time.[11] This has resulted in cities having nearly eight parking spaces for every car in America, which have created cities almost fully dedicated to parking from free on-street parking to parking lots up to three times the size of the businesses they serve.[11] This prevalence in parking has perpetuated a loss in competition between other forms of transportation such that driving becomes the de facto choice for many people even when alternatives do exist.

Street design

[edit]

The design of city roads can contribute significantly to the perceived and actual need to use a car over other modes of transportation in daily life.[12] In the urban context car dependence is induced in greater numbers by design factors that operate in opposite directions - first, design that makes driving easier and second, design that makes all other forms of transportation more difficult. Frequently these two forces overlap in a compounding effect to induce more car dependence in an area that would have potential for a more heterogenous mix of transportation options. These factors include things like the width of roads, that make driving faster and therefore 'easier' while also making a less safe environment for pedestrians or cyclists that share the same road. The prevalence of on-street parking on most residential and commercial streets also makes driving easier while taking away street space that could be used for protected bike lanes, dedicated bus lanes, or other forms of public transportation.

Sociocultural factors

[edit]Sociocultural factors are greatly influential in the emergence and perpetuation of car dependency.[13] These include the rise of car culture, consumer preferences, and the symbolic meanings associated with automobiles.

Symbolism

[edit]Cars emerged in the 20th century as symbols of modernity, progress, and freedom. They were preceded by the proliferation of railways, which triggered a shift in the previously constrained travel patterns of the population. This change was accelerated by the development of the automobile and the economic incentives that travel introduced.[13] In the United States, for instance, registered vehicles increased from 8,000 in 1900 to more than 20 million in 1927[14]. The growing popularity of individual vehicles prompted the development of new car-focused infrastructure, which in turn fueled the adoption of cars as the default means of transportation.[13]

The symbolic functions of cars extend beyond the sense of freedom. The automobile has traditionally signified masculinity, but it has also been associated with women's liberation. Economic status is often displayed through the possession and use of high-end personal vehicles, which are considered objects of conspicuous consumption.[15] A 2024 study conducted in Brazil found that vehicle ownership increases subjects' "mating value" and social dominance. This relationship held true for both men and women, and is amplified when the vehicle owned is perceived as luxurious. These symbolic functions encourage the possession of personal vehicles and therefore contribute to car dependency.[16]

Emotional attachment

[edit]The emotional attachment that driving creates has also been identified as an important contributor to car dependency. Drivers tend to overlook the negative externalities of automobiles and car-centric environments due to the pleasant feelings they experience while driving.[13] Research conducted in the United States shows that moderate levels of car dependency can increase people's perceived life satisfaction. While acknowledging the strong influence of the built environment in this association, the article underscores that psychological factors such as a sense of independence and freedom are also influential.[17]

In recent years, it has been observed that car owners increasingly value personal space and the apparent safety from outside dangers that cars afford. Alternative transportation options compare negatively to personal vehicles in this regard and might be disfavoured by commuters who experience a sense of protection while in their vehicles. The result is a vicious cycle in which car-centric infrastructure increases the risk of walking, biking, or using public transportation, which in turn promotes the use of cars and, ultimately, the construction of more car-centric infrastructure.[18]

Negative externalities of automobiles

[edit]

According to the Handbook on estimation of external costs in the transport sector[19] made by the Delft University, which is the main reference in the European Union for assessing the externalities of cars, the main external costs of driving a car are:

- congestion and scarcity costs

- collision costs

- air pollution costs

- noise pollution costs

- climate change costs

- costs for nature and landscape

- costs for water pollution

- costs for soil pollution

- costs of energy dependency

Other negative externalities may include increased cost of building infrastructure, inefficient use of space and energy, pollution and per capita fatality.[20][21]

Addressing the issue

[edit]There are a number of planning and design approaches to redressing automobile dependency,[22] known variously as New Urbanism, transit-oriented development, and smart growth. Most of these approaches focus on the physical urban design, urban density and landuse zoning of cities. Paul Mees argued that investment in good public transit, centralized management by the public sector and appropriate policy priorities are more significant than issues of urban form and density.

Removal of minimum parking requirements from building codes can alleviate the problems generated by car dependency. Minimum parking requirements occupy valuable space that otherwise can be used for housing. However, removal of minimum parking requirements will require implementation of additional policies to manage the increase in alternative parking methods.[23]

There are, of course, many who argue against a number of the details within any of the complex arguments related to this topic, particularly relationships between urban density and transit viability, or the nature of viable alternatives to automobiles that provide the same degree of flexibility and speed. There is also research into the future of automobility itself in terms of shared usage, size reduction, road-space management and more sustainable fuel sources.

Car-sharing is one example of a solution to automobile dependency. Research has shown that in the United States, services like Zipcar have reduced demand by about 500,000 cars.[24] In the developing world, companies like eHi,[25] Carrot,[26][27] Zazcar[28] and Zoom have replicated or modified Zipcar's business model to improve urban transportation to provide a broader audience with greater access to the benefits of a car and provide last kilometer connectivity between public transportation and an individual's destination. Car sharing also reduces private vehicle ownership.

Urban sprawl and smart growth

[edit]

Whether smart growth does or can reduce problems of automobile dependency associated with urban sprawl has been fiercely contested for several decades. The influential study in 1989 by Peter Newman and Jeff Kenworthy compared 32 cities across North America, Australia, Europe and Asia.[29] The study has been criticised for its methodology,[30] but the main finding, that denser cities, particularly in Asia, have lower car use than sprawling cities, particularly in North America, has been largely accepted, but the relationship is clearer at the extremes across continents than it is within countries where conditions are more similar.

Within cities, studies from across many countries (mainly in the developed world) have shown that denser urban areas with greater mixture of land use and better public transport tend to have lower car use than less dense suburban and exurban residential areas. This usually holds true even after controlling for socio-economic factors such as differences in household composition and income.[31]

This does not necessarily imply that suburban sprawl causes high car use, however. One confounding factor, which has been the subject of many studies, is residential self-selection:[32] people who prefer to drive tend to move towards low-density suburbs, whereas people who prefer to walk, cycle or use transit tend to move towards higher density urban areas, better served by public transport. Some studies have found that, when self-selection is controlled for, the built environment has no significant effect on travel behaviour.[33] More recent studies using more sophisticated methodologies have generally rejected these findings: density, land use and public transport accessibility can influence travel behaviour, although social and economic factors, particularly household income, usually exert a stronger influence.[34]

The paradox of intensification

[edit]Reviewing the evidence on urban intensification, smart growth and their effects on automobile use, Melia et al. (2011)[35] found support for the arguments of both supporters and opponents of smart growth. Planning policies that increase population densities in urban areas do tend to reduce car use, but the effect is weak. So, doubling the population density of a particular area will not halve the frequency or distance of car use.

These findings led them to propose the paradox of intensification:

- All other things being equal, urban intensification which increases population density will reduce per capita car use, with benefits to the global environment, but will also increase concentrations of motor traffic, worsening the local environment in those locations where it occurs.

At the citywide level, it may be possible, through a range of positive measures to counteract the increases in traffic and congestion that would otherwise result from increasing population densities:[36] Freiburg im Breisgau in Germany is one example of a city which has been more successful in reducing automobile dependency and constraining increases in traffic despite substantial increases in population density.[37]

This study also reviewed evidence on local effects of building at higher densities. At the level of the neighbourhood or individual development, positive measures (like improvements to public transport) will usually be insufficient to counteract the traffic effect of increasing population density.

This leaves policy-makers with four choices:

- intensify and accept the local consequences

- sprawl and accept the wider consequences

- a compromise with some element of both

- or intensify accompanied by more direct measures such as parking restrictions, closing roads to traffic and carfree zones.

See also

[edit]- Automotive industry

- Accessibility (transport)

- Automotive city

- Car costs

- Car-free movement

- Cycling infrastructure

- Effects of the car on societies

- Fossil fuels lobby – Lobbying supporting the fossil fuels industry

- Forced rider

- Jevons paradox

- Mobile source air pollution – Air pollution emitted by motor vehicles, airplanes, locomotives, and other engines

- Exhaust gas – Gases emitted as a result of fuel reactions in combustion engines

- Motonormativity

- Peak car

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Sustainable transport

- Transit-oriented development

- Transport divide

- Urban planning

- Walkability

- 2008–2010 automotive industry crisis

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ a b Mattioli, Giulio; Roberts, Cameron; Steinberger, Julia K.; Brown, Andrew (1 August 2020). "The political economy of car dependence: A systems of provision approach". Energy Research & Social Science. 66 101486. Bibcode:2020ERSS...6601486M. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2020.101486. ISSN 2214-6296.

- ^ "What Are State Gas Taxes and How Are They Used? | Tax Policy Center". taxpolicycenter.org. 28 January 2025. Archived from the original on 31 January 2025. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ Meyersohn, Nathaniel (20 May 2023). "This little-known rule shapes parking in America. Cities are reversing it". CNN. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ Turcotte, Martin (2008). "Dependence on cars in urban neighborhoods". Canadian Social Trends. Statistics Canada. Archived from the original on 8 January 2019.

- ^ Mattioli, Giulio; Roberts, Cameron; Steinberger, Julia K.; Brown, Andrew (2020). "The political economy of car dependence: A systems of provision approach". Energy Research & Social Science. 66 101486. Bibcode:2020ERSS...6601486M. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2020.101486.

- ^ a b Wells, Christopher W.; Cronon, William (2014). Car country: an environmental history. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-99429-1. OCLC 932622166.

- ^ Robinson, Grayson (2 May 2021). "The History Behind Car (In)Dependence in the US vs World". ArcGIS StoryMaps. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- ^ 70 Stat. 374

- ^ Bronin, Sarah (2021). "Zoning by a Thousand Cuts: The Prevalence and Nature of Incremental Regulatory Constraints on Housing". Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy.

- ^ Chakrabarti, Sandip (1 February 2017). "How can public transit get people out of their cars? An analysis of transit mode choice for commute trips in Los Angeles". Transport Policy. 54: 80–89. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2016.11.005. ISSN 0967-070X.

- ^ a b Shoup, Donald (2011). The High Cost of Free Parking. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-884829-98-7.

- ^ Cao, Jun; Jin, Tanhua; Shou, Tao; Cheng, Long; Liu, Zhicheng; Witlox, Frank (25 July 2023). "Investigating the Nonlinear Relationship Between Car Dependency and the Built Environment". Urban Planning. 8 (3): 41–55. doi:10.3929/ethz-b-000627176. ISSN 2183-7635.

- ^ a b c d Mattioli, Giulio; Roberts, Cameron; Steinberger, Julia K.; Brown, Andrew (1 August 2020). "The political economy of car dependence: A systems of provision approach". Energy Research & Social Science. 66 101486. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2020.101486. ISSN 2214-6296.

- ^ a b "Highway Statistics Summary To 1995 - Section II (Motor Vehicles Data)". www.fhwa.dot.gov. Retrieved 9 October 2025.

- ^ Sovacool, Benjamin K.; Axsen, Jonn (1 December 2018). "Functional, symbolic and societal frames for automobility: Implications for sustainability transitions". Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice. 118: 730–746. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2018.10.008. ISSN 0965-8564.

- ^ Silva, João Lucas G. da; Costa, Tainah P. de P.; Castro, Felipe N. (1 February 2024). "Tell me what you buy, and I will tell you how you are: Luxurious cars increase perceptions of status, social dominance, and attractiveness". Personality and Individual Differences. 218 112489. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2023.112489. ISSN 0191-8869.

- ^ Saadaoui, Rababe; Salon, Deborah; Jamme, Huê-Tâm; Corcoran, Nicole; Hitzeman, Jordyn (April 2025). "Does Car Dependence Make People Unsatisfied With Life? Evidence From a U.S. National Survey". Travel Behaviour and Society. 39 100954. doi:10.1016/j.tbs.2024.100954.

- ^ Wells, Peter; Xenias, Dimitrios (1 September 2015). "From 'freedom of the open road' to 'cocooning': Understanding resistance to change in personal private automobility". Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions. 16: 106–119. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2015.02.001. ISSN 2210-4224.

- ^ Maibach, M.; Schreyer, C.; Sutter, D.; van Essen, H.P.; et al. (February 2008). Handbook on estimation of external costs in the transport sector (PDF) (Report). CE Delft. p. 332. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 20 September 2015.

- ^ "What Is Automobile Dependency?". WorldAtlas. 7 January 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2023.

- ^ Wang, Xiaoquan; Shao, Chunfu; Yin, Chaoying; Zhuge, Chengxiang (September 2018). "Exploring the Influence of Built Environment on Car Ownership and Use with a Spatial Multilevel Model: A Case Study of Changchun, China". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 15 (9): 1868. doi:10.3390/ijerph15091868. ISSN 1661-7827. PMC 6165495. PMID 30158467.

- ^ Reid, Carlton (17 August 2023). "Sticks Not Carrots Needed To Get Drivers Out Of Cars, Say Climate Scientists". Forbes. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ Samsonova, Tatiana (25 February 2021). "Reversing Car Dependency". The International Transport Forum. 181: 41 – via OECD/ITF.

- ^ Boudette, Neal E. (3 February 2014). "Car-Sharing, Social Trends Portend Challenge for Auto Sales". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ eHi

- ^ "Carrot". Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ "Sustainable Cities Collective".

- ^ "Zazcar". Archived from the original on 11 October 2019. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ Cities and Automobile Dependence: An International Sourcebook, Newman P and Kenworthy J, Gower, Aldershot, 1989.

- ^ Mindali, O.; Raveh, A.; Salomon, I. (2004). "Urban density and energy consumption: a new look at old statistics". Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice. 38 (2): 143–162. Bibcode:2004TRPA...38..143M. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2003.10.004.

- ^ e.g., Frank, L.; Pivot, G. (1994). "Impact of Mixed Use and Density on Three Modes of Travel". Transportation Research Record (1446): 44–52.

- ^ "Transport Reviews". Taylor & Francis. Retrieved 23 February 2025.

- ^ e.g., Bagley, M. N.; Mokhtarian, P. L. (2002). "The impact of residential neighborhood type on travel behavior: A structural equations modeling approach". Annals of Regional Science. 36 (2): 279. Bibcode:2002ARegS..36..279B. doi:10.1007/s001680200083.

- ^ e.g., Handy, S.; Cao, X.; Mokhtarian, P.L. (2005). "Correlation or causality between the built environment and travel behavior? Evidence from Northern California". Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment. 10 (6): 427–444. Bibcode:2005TRPD...10..427H. doi:10.1016/j.trd.2005.05.002.

- ^ Melia, S.; Barton, H.; Parkhurst, G. (2011). "The Paradox of Intensification". Transport Policy. 18 (1): 46–52. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2010.05.007.

- ^ Ostermeijer, Francis; Koster, Hans R A; van Ommeren, Jos; Nielsen, Victor Mayland (18 February 2022). "Automobiles and urban density". Journal of Economic Geography. 22 (5): 1073–1095. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbab047.

- ^ Broaddus, Andrea (2010). "Tale of Two Ecosuburbs in Freiburg, Germany". Journal of the Transportation Research Board. December: 114–122. doi:10.3141/2187-15. S2CID 15698518 – via SAGE.

Bibliography

[edit]- Mees, P. (2000). A Very Public Solution:transport in the dispersed city. Carlton South, Vic.: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0-522-84867-2.

- Geels, F.; Kemp, R.; Dudley, G.; Lyons, G. (2012). Automobility in Transition? A Socio-Technical Analysis of Sustainable Transport. Oxford: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-88505-8.

- Boussauw, Kobe; Papa, Enrica; Fransen, Koos (2023). "Car Dependency and Urban Form". Urban Planning. 8 (3): 1–5. doi:10.17645/up.v8i3.7260.

- Sierra Muñoz, Jaime; Duboz, Louison; Pucci, Paola; Ciuffo, Biagio (2024). "Why do we rely on cars? Car dependence assessment and dimensions from a systematic literature review". European Transport Research Review. 16 (17). Bibcode:2024ETRR...16...17S. doi:10.1186/s12544-024-00639-z. hdl:11311/1262174.

External links

[edit]Car dependency

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Scope

Core Characteristics

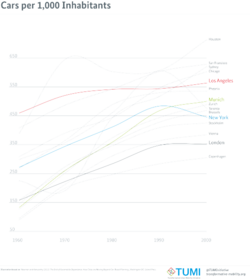

Car dependency describes transportation and land use patterns that prioritize automobile access while providing inferior alternatives, making non-motorized and public transit options impractical for most daily activities.[10] This condition arises from urban designs featuring dispersed, low-density development with segregated land uses, requiring vehicles to bridge distances between residences, workplaces, and services.[10][11] Core indicators include vehicle ownership rates exceeding 450 per 1,000 population and annual per capita vehicle miles traveled over 8,000, with automobiles comprising more than 80% of trips.[10] Infrastructure emphasizes high-capacity roadways optimized for automotive speeds and volumes, alongside abundant parking—often four spaces per vehicle in the United States—while devoting over 50% of central city land to roads and parking in many cases.[10][11] Distances to essential amenities frequently surpass 1 km, rendering walking or cycling infeasible without dedicated facilities, and automobile commuting mode shares exceed 65%.[2][10] Non-drivers experience severe mobility disadvantages, as car-centric planning limits access to goods and services without personal vehicles, perpetuating high motorization rates and trip frequencies.[10][2] In the United States, cars accounted for 85% of trips in 2010, compared to 50-65% in European cities with denser, mixed-use forms.[11] This reliance stems from contextual factors like poor alternative transport supply and spatial mismatches, rather than mere preference.[2]Measurement and Global Prevalence

Car dependency is quantified using empirical metrics that assess automobile ownership, usage, and modal integration in transportation systems. Key indicators include motor vehicles per 1,000 inhabitants, which measures access and infrastructure reliance; car modal share, representing the percentage of trips completed by private automobile; and vehicle kilometers traveled (VKT) or miles traveled (VMT) per capita, capturing travel intensity and distance dependence.[2][12] These metrics derive from national transport surveys, census data, and international databases, often supplemented by built environment variables like urban density and road network density to contextualize dependence.[13] Ownership rates emphasize structural availability, while modal share and VKT highlight behavioral lock-in, where high values indicate limited viable alternatives.[14] Globally, motor vehicle ownership rates reveal stark disparities tied to economic development and urbanization patterns, with high-income nations exhibiting the highest prevalence. As of recent estimates, the United States maintains around 850 vehicles per 1,000 people, followed by countries like Australia (over 700) and Canada (around 650), reflecting extensive suburban sprawl and highway-centric infrastructure.[15] In Europe, rates average 500-600 per 1,000, varying by nation—higher in Germany (600+) and lower in denser urban states like the Netherlands (around 500). Developing regions show lower figures: China at approximately 180, India at 26, and sub-Saharan Africa below 50 per 1,000, constrained by income levels and alternative mobilities like informal transit.[16][17] Worldwide, the global average hovers near 200 vehicles per 1,000, but this masks concentrations in automobile-oriented economies comprising about 15-20% of the world's population.[15] Car modal share underscores usage prevalence, with automobiles dominating trips in car-dependent regions. A 2024 analysis of global commute data found that cars account for 51% of commutes worldwide, rising to over 80% in the United States and Australia, where public transit and non-motorized options serve marginal roles in daily travel.[18] In contrast, European cities average 30-50% car share due to integrated rail and bus networks, while Asian megacities like Tokyo or Mumbai see under 20% amid high-density public systems.[19] VKT per capita reinforces this, exceeding 10,000 km annually in the U.S. (versus a global average of ~3,000-4,000), indicating not just ownership but habitual reliance for essential activities.[14] These patterns correlate with GDP per capita and urban form, where sprawl amplifies dependence beyond raw ownership figures.[20]Historical Origins

Pre-Automobile Transportation Patterns

Prior to the widespread adoption of automobiles, urban transportation in Western cities, particularly in the United States and Europe, predominantly relied on pedestrian movement and animal-powered vehicles, fostering compact settlements where residential, commercial, and industrial activities were concentrated within short walking distances of one to two miles. In the "walking city" era before approximately 1880, daily commutes averaged under 30 minutes on foot, with roads primarily serving pedestrians, carts, and horse-drawn wagons rather than high-speed vehicles, allocating only about 10% of urban land to transportation infrastructure. This pattern constrained urban expansion, as horse travel speeds rarely exceeded 5 miles per hour on crowded streets, limiting effective radii to a few miles from city centers and promoting high population densities often exceeding 100 persons per acre in core areas.[21][22][23] The mid-19th century introduced mechanized public transit innovations that began modestly extending urban reach while still depending on animal or early mechanical power. Horse-drawn omnibuses emerged in New York City in the late 1820s, providing fixed-route service along busy corridors at capacities of 10-20 passengers, though they operated slowly amid street congestion from mixed traffic including bicycles and carriages. By the 1830s, horse-drawn streetcars—railed vehicles pulled by teams of 2-4 horses—replaced omnibuses on key lines, offering smoother rides and higher speeds of up to 6 miles per hour, which facilitated initial suburbanization as developers extended lines to new neighborhoods, yet overall urban forms remained denser than later auto-oriented patterns due to fixed routes and limited service frequencies. These systems carried millions annually in major cities; for instance, by 1880, horsecars transported over 200 million passengers in the U.S., but required vast stabling for horses—up to one per streetcar—generating sanitation challenges from manure accumulation estimated at 15,000 tons daily in New York alone.[24][22][25] The late 19th century marked a transition with the electrification of street railways starting in the 1880s, powered by overhead trolleys or conduits, which accelerated speeds to 15-20 miles per hour and dramatically boosted ridership and suburban development. Electric streetcars, first commercially viable in Richmond, Virginia, in 1888, replaced horses on over 15,000 miles of U.S. track by 1900, enabling commutes of 5-10 miles in under an hour and spurring real estate booms along corridors, as private companies laid tracks to sell adjacent land. Despite these advances, pre-automobile systems emphasized collective, rail-based mobility over individual transport, with urban land use for streets and rights-of-way remaining under 15% and cities retaining mixed-use, high-density morphologies incompatible with later automobile-centric sprawl. Congestion persisted from multimodal street sharing, underscoring the causal limits of non-motorized power in scaling personal mobility without densification.[26][22][25]Rise of Mass Automobile Adoption (1900-1950)

The introduction of the Ford Model T in 1908 marked a pivotal shift toward mass automobile accessibility in the United States, with its initial price of $850 equivalent to about two years' wages for an average worker, limiting early ownership primarily to urban elites and rural enthusiasts.[27] By implementing the moving assembly line in 1913 at the Highland Park plant, Henry Ford reduced production time per vehicle from over 12 hours to about 93 minutes, enabling output of nearly 15 million Model Ts by 1927 and driving down prices to $260 by 1925—affordable for many middle-class families. This innovation, combined with standardized parts and durable design suited for unpaved roads, facilitated widespread rural adoption, as farmers used vehicles for chores like plowing and transport, supplanting horse-drawn alternatives.[28] Registered passenger automobiles in the U.S. grew from approximately 8,000 in 1900 to 458,500 by 1910, reflecting initial experimentation amid rudimentary infrastructure.[29] By 1920, registrations exceeded 9 million vehicles (including trucks), equating to one per about 11 people, fueled by installment financing introduced in the late 1910s and rising real wages during the 1920s economic expansion.[30] The 1920s saw further acceleration, with annual production surpassing 4 million units by 1929, as competitors like General Motors offered diverse models with electric starters and closed bodies, broadening appeal beyond utilitarian needs.[31] However, the Great Depression curtailed growth, with registrations stagnating around 23 million passenger cars by 1930 before recovering to about 27 million by 1940 amid federal road improvements under the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921.[29] World War II shifted automobile manufacturing to military production, halting civilian output from 1942 to 1945 and maintaining registrations near 25 million by 1944, as rationing and scrap drives preserved existing fleets.[32] Postwar reconversion spurred a surge, with 1950 registrations reaching over 40 million motor vehicles, predominantly passenger cars, as pent-up demand and economic boom enabled one vehicle per roughly four Americans.[29] In contrast, Europe lagged due to denser urban populations, entrenched rail and tram networks, and devastation from two world wars; for instance, British production rose modestly from 73,000 vehicles in 1922 to 239,000 in 1929, with per capita ownership far below U.S. levels until mid-century.[33] This U.S.-centric trajectory established automobiles as a core element of personal mobility, laying groundwork for dependency by prioritizing individual over collective transport.[34]Postwar Suburbanization and Infrastructure Boom (1950-1980)

The postwar period in the United States marked a pivotal shift toward suburban living, fueled by economic expansion, demographic pressures from the baby boom, and supportive federal policies that prioritized single-family homes in low-density areas. The Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944, known as the GI Bill, offered veterans low-interest, zero-down-payment loans for home purchases, enabling millions to relocate from urban centers to emerging suburbs where land was cheaper and space more abundant. Between 1944 and 1956, the Veterans Administration guaranteed approximately 2.4 million such loans, many directed toward suburban developments like Levittown, New York, which constructed over 17,000 homes by 1951 using mass-production techniques. This policy, complemented by Federal Housing Administration (FHA) mortgage insurance that favored new suburban construction over urban rehabilitation, accelerated a housing boom: annual housing starts rose from under 200,000 in 1945 to over 1.5 million by 1950, with suburbs capturing the majority of growth due to their alignment with lending criteria emphasizing spacious lots and automobile access.[35] Suburban population expansion reflected these incentives, with the proportion of Americans living in suburban areas increasing from about 23% in 1950 to over 30% by 1960 and 37% by 1970, as central city shares declined amid white flight and industrial relocation.[36] This dispersal pattern inherently promoted car dependency, as suburban designs—characterized by separated land uses, wide streets, and minimal pedestrian infrastructure—rendered daily travel reliant on personal vehicles rather than walking, cycling, or transit. Automobile registrations surged accordingly, from 49 million vehicles in 1950 to 89 million by 1960 and 133 million by 1980, with household ownership rates climbing from roughly 59% possessing at least one car in 1950 to 82% by 1970, driven by affordable models like the Chevrolet and widespread availability of financing.[37] The infrastructure boom amplified this trend through massive federal investment in roadways. The Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 authorized the 41,000-mile Interstate Highway System, providing 90% federal funding for construction to enhance national defense mobility, commerce, and congestion relief on existing routes.[38] Work commenced swiftly, opening 20,000 miles by 1965, 30,000 by 1970, and approximately 40,000 by 1980, at a total cost exceeding $100 billion in nominal terms.[39] These limited-access highways bypassed urban cores, enabling longer commutes from distant suburbs—average urban travel distances doubled in many metro areas—while federal funding formulas discouraged investment in public transit, leading to the abandonment of streetcar systems in over 40 cities between 1945 and 1960.[40] The resulting sprawl locked in car reliance, as new developments clustered along highway corridors where densities were too low (often under 2,000 persons per square mile) to support viable alternatives, creating path dependence in land use patterns that prioritized automotive throughput over mixed-use urbanism.[41]Primary Causes

Technological and Economic Drivers

The introduction of the moving assembly line in automobile manufacturing, pioneered by Henry Ford at his Highland Park plant on December 1, 1913, fundamentally transformed production efficiency by reducing the time to assemble a Model T from approximately 12 hours to about 90 minutes. This technological breakthrough lowered labor costs and enabled economies of scale, driving down the retail price of the Model T from $850 in 1908 to $260 by 1925, thereby shifting automobiles from luxury goods to attainable consumer products for average households.[42][43][44] These innovations spurred economic multipliers across supply chains, as mass production demanded vast inputs of steel, glass, rubber, and petroleum, creating millions of jobs in upstream industries and stimulating urban-rural freight shifts from rail to truck transport for cost advantages in flexibility and door-to-door delivery. In the United States, the automobile sector became a cornerstone of industrial output, with vehicle registrations surging from under 8 million in 1917 to 23 million by 1929, underpinning the era's consumer-driven prosperity through wage increases—such as Ford's $5 daily rate in 1914—and ancillary employment in dealerships and service.[28][45][46] Economically, the low marginal costs of personal vehicle operation, bolstered by abundant domestic oil supplies and refining advancements, further entrenched car dependency by making individualized mobility cheaper per capita than expanding public rail or streetcar systems, which faced diseconomies from fixed infrastructure investments. This dynamic fostered path dependency, as capital sunk into vehicle fleets and supplier networks locked societies into automotive paradigms, with U.S. auto production achieving global dominance without tariff protections by leveraging high-volume efficiencies.[34][47]Policy and Regulatory Factors

Policies favoring automobile infrastructure over alternatives have entrenched car dependency by subsidizing driving costs and shaping urban form to prioritize vehicles. In the United States, the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 authorized over $25 billion (equivalent to about $280 billion in 2023 dollars) for the Interstate Highway System, enabling rapid suburban expansion and long-distance commuting while displacing urban neighborhoods and underfunding public transit.[48] This federal emphasis on highways, funded largely through the Highway Trust Fund derived from motor fuel taxes, allocated the vast majority of resources to roads rather than mass transit; for decades, transit received less than 20% of surface transportation funding despite growing urban densities.[49] Such imbalances persist, with recent analyses showing that highway investments often exacerbate congestion and sprawl without proportional support for rail or bus systems.[50] Zoning regulations have further reinforced car-centric development by mandating minimum off-street parking spaces for new buildings, compelling developers to allocate prime land to vehicle storage and inflating construction costs by 20-30% in some cases.[51] Adopted widely post-World War II, these requirements—often one space per dwelling unit or per 300-500 square feet of commercial space—discourage dense, walkable neighborhoods by ensuring ample free parking, which suppresses demand for alternatives like cycling or shared mobility.[52] Single-use zoning laws, segregating residential, commercial, and industrial areas, necessitate longer trips resolvable primarily by car, as evidenced by studies linking such policies to higher vehicle miles traveled per capita.[8] Reforms eliminating these minima in cities like Minneapolis have demonstrated potential to reduce parking oversupply and foster mixed-use development, though entrenched regulations maintain dependency in most jurisdictions.[53] Fiscal policies, including low fuel taxes and implicit subsidies for fossil fuels, have lowered the marginal cost of driving, encouraging overuse relative to societal externalities like pollution and congestion. The U.S. federal gasoline tax has remained at 18.4 cents per gallon since 1993, unadjusted for inflation or increased vehicle efficiency, effectively reducing its real value by over 50% and failing to internalize environmental costs estimated at $0.20-0.50 per gallon driven.[54] Annual U.S. fossil fuel subsidies, including tax breaks for oil production and depletion allowances, totaled approximately $20 billion in 2019, distorting markets toward petroleum-dependent transport over efficient alternatives.[55] Internationally, similar patterns appear; for instance, underpriced road fuels in many OECD countries contribute to car overreliance by undercharging for infrastructure wear and emissions, with economic models showing that aligning taxes with full costs could cut vehicle kilometers traveled by 10-15%.[56] These regulatory frameworks, rooted in mid-20th-century priorities, sustain a feedback loop where policy-induced sprawl demands more roads, perpetuating dependency.[5]Cultural and Demographic Influences

Cultural factors promoting car dependency center on the automobile's role as a symbol of personal autonomy and social status, particularly in individualistic societies. In the United States, cars represent freedom of movement, enabling spontaneous travel without reliance on fixed schedules or shared spaces, a value deeply embedded in cultural narratives of self-reliance and exploration.[57] [58] This perception drives consumer preferences for private vehicles over public transit, as ownership confers control over one's itinerary and privacy during commutes, aligning with broader societal emphases on individual agency rather than collective efficiency.[59] Demographic characteristics further exacerbate car dependency through variations in household needs and settlement patterns. Higher household incomes strongly correlate with increased vehicle ownership and use, as greater financial resources enable acquisition and maintenance of cars to access employment, education, and leisure opportunities spread across expansive areas.[2] Larger family sizes, particularly those including children, heighten demand for personal automobiles due to the logistical challenges of coordinating multiple trips with public options, favoring flexible private transport.[2] Population density plays a pivotal causal role, with lower densities—often stemming from demographic preferences for suburban or rural living with more living space—necessitating cars for viable mobility. Empirical analysis across 232 cities in 57 countries from 1960 to 2012 reveals that higher car ownership induces urban sprawl, reducing population density by about 2.2% for each additional car per 100 inhabitants in the long run, as expanded road networks and vehicle access encourage outward migration from dense cores.[60] This dynamic perpetuates dependency, as sprawling demographics inherently limit the feasibility and appeal of alternatives like walking or transit. Generational trends show relative stability, with no significant decline in vehicle ownership among millennials compared to prior cohorts when controlling for income and location.[61]Benefits and Positive Outcomes

Economic Productivity and Growth

The adoption of automobiles has historically driven economic expansion through the growth of the automotive manufacturing sector and its supply chain. In the United States, the auto industry and related activities contributed approximately 5.4% to gross domestic product (GDP) in recent years, generating $1.49 trillion in economic output and supporting 9.6 million jobs across manufacturing, sales, and services.[62] This sector alone accounts for about 3% of national GDP when focusing on automakers and suppliers, underscoring its role as the largest manufacturing cluster by output.[63] Broader transportation services, heavily reliant on personal vehicles, added 6.7% or $1.7 trillion to U.S. GDP in 2022, reflecting the efficiency of car-based logistics in moving goods and enabling just-in-time supply chains that reduce inventory costs and boost industrial productivity.[64] Car dependency facilitates labor market flexibility, allowing workers to access a wider range of employment opportunities beyond immediate neighborhoods, which enhances overall economic productivity. Empirical data indicate a positive correlation between vehicle miles traveled (VMT) per capita and personal income, with VMT rising by about 360 miles for every $1,000 increase in income, suggesting that automobile access supports income growth by expanding commute radii and job matching.[65] This mobility effect is evident in postwar economic booms, where mass automobile adoption paralleled rapid GDP growth; for instance, the U.S. auto industry's output share peaked during the mid-20th century, fueling consumer spending and industrial output that propelled annual GDP increases averaging 3-4% from 1950 to 1970.[66] By decentralizing production and residential patterns, cars enabled economies of scale in manufacturing hubs while accommodating population growth without the congestion bottlenecks of rail-dependent systems. Furthermore, automobile infrastructure investments have yielded long-term productivity gains through expanded freight transport and regional integration. Highway systems, predicated on car and truck dependency, have lowered shipping costs per ton-mile compared to rail alternatives in many corridors, contributing to a 50% decline in real freight transport costs since 1950 and supporting sectors like retail and agriculture that rely on timely distribution.[64] Studies attribute part of this to induced economic activity from vehicle-oriented development, where accessible suburbs host logistics parks and edge-city employment centers, fostering agglomeration benefits without forcing high-density urban cores. While critics in academic literature often emphasize externalities, data from industry analyses affirm that these dynamics have sustained higher per capita output in car-dependent economies versus transit-reliant ones with restricted mobility.[66][67]Individual Liberty and Accessibility

Automobile ownership facilitates greater personal autonomy by allowing individuals to travel on their own schedules, free from the fixed timetables and routes of public transit systems. This independence enables spontaneous decision-making in daily activities, such as errands or social visits, which public transport often constrains due to wait times and limited service frequency.[68] Studies indicate that private vehicle users report higher levels of mastery, self-esteem, and feelings of autonomy compared to those reliant on public options.[68] Cars enhance accessibility to employment and essential services, particularly in suburban and rural areas where job opportunities are geographically dispersed and public transit coverage is sparse. Empirical analyses show that car ownership significantly boosts employment probabilities, with one systematic review finding a positive association between vehicle access and labor market outcomes, including reduced unemployment duration.[69] [70] For instance, longitudinal data from U.S. metropolitan areas link car access to income gains and lower unemployment rates, while public transit access correlates weakly with earnings and, in some cases, higher joblessness among carless households.[71] This mobility edge is especially pronounced for low-income and welfare-dependent individuals, where owning a vehicle expands the effective job search radius beyond what walking or buses permit, often enabling escapes from poverty traps. Federal Reserve research highlights that car ownership raises work probabilities among welfare recipients by providing reliable access to distant employment centers not served by transit.[72] In the United States, where over 80% of households own at least one vehicle, this access unlocks broader economic opportunities, including education and family connections, outweighing transit alternatives in non-dense regions.[58] Door-to-door convenience of automobiles reduces overall travel burdens, preserving time and energy for productive pursuits rather than transfers or walking to stops. This efficiency supports individual liberty by minimizing reliance on collective systems, which can impose crowding, delays, or vulnerability to service disruptions. For populations with disabilities or in low-density settings, cars represent a critical enabler of independence, with ownership linked to improved psychosocial well-being and reduced isolation.[68][58]Comparative Efficiency Over Alternatives

Automobiles demonstrate superior door-to-door efficiency compared to public transit across diverse urban contexts. Empirical analysis of travel times in cities including São Paulo, Stockholm, Sydney, and Amsterdam reveals that public transit requires 1.4 to 2.6 times longer durations than private vehicles, with cars faster in over 98% of assessed areas.[73] [74] In the United States, door-to-door commutes average 51 minutes by transit versus 29 minutes by car, reflecting added delays from walking to stops, waiting, and transfers.[75] These disparities widen outside central districts and during off-peak hours, where transit frequencies diminish.[73] In low-density suburban and exurban environments, automobiles outperform alternatives by providing viable access where fixed-route transit fails due to insufficient ridership. Public transit demands concentrated populations for economic feasibility, rendering it impractical in spread-out areas; cars, by contrast, enable direct, on-demand travel irrespective of settlement patterns.[8] [76] This capability sustains economic productivity by connecting dispersed labor markets and services, as evidenced by higher vehicle ownership correlating with lower urban densities in U.S. data.[1] Relative to non-motorized options like walking or cycling, automobiles excel in range, capacity, and all-weather reliability, accommodating longer distances, cargo, and family needs essential for modern lifestyles. Transit speeds average 21.5 miles per hour for rail and 14.1 for buses, trailing effective car velocities that incorporate flexibility for errands and unscheduled deviations.[77] While mass transit achieves higher energy efficiency per passenger-mile in high-occupancy scenarios, automobiles' point-to-point utility minimizes unutilized travel time, yielding net gains in personal and societal time budgets.[78]

.jpg/250px-ON401nearWestonRoad-FacingSouthAerial_(28172578200).jpg)

.jpg)